Abstract

Cu electrodeposition and the electrocatalysis of hydrogenation reactions thereupon involve significant interactions with adsorbed hydrogen. Electrochemical mass spectrometry (EC-MS) is used to explore the formation and decomposition of surface hydride on Cu(111) in 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4. Hydride formation is associated with two reduction waves that reflect the potential-dependent Hads coverage and its reconstruction. Voltammetric cycling reveals an additional oxidative and reductive feature at ≈ −0.05 V versus the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) that reflects the state of the 2D surface hydride. Extending the voltammetric window to more negative potentials results in an increase in Hads coverage and surface reconstruction that subsequently leads to accelerated hydride decomposition at positive potentials. Voltammetric and chronoamperometric analysis of hydride formation indicates a Hads coverage of ≈0.75 monolayers (ML) between −0.225 V vs RHE and −0.275 V vs RHE with further increases in Hads observed with the onset and acceleration of the HER at more negative potentials. Returning to more positive potentials, hydride decomposition begins above −0.05 V vs RHE. Recombination of Hads to form H2 accounts for desorption of ≈0.5 ML of Hads while its oxidation to H3O+ consumes between ≈0.15 and ≈0.4 ML of Hads, depending on the specific electrochemical conditions. The potential-dependent Hads coverage and surface reconstruction are congruent with trends identified in recent computational and electrochemical scanning tunneling microscopy studies. In contrast to perchloric acid, the presence of strongly adsorbing anions, such as sulfate or halides, favors hydride decomposition via the recombination pathway.

Introduction

The technological impact of Cu spans a wide range from its ubiquitous presence in microelectronic interconnects to its use as a catalyst in emergent electrosynthetic reactions relevant to the electrification of the chemical industry.1−5 In these applications, the interaction of Cu with hydrogen exerts important effects that need to be understood. In electrolytic and electroless Cu deposition, hydrogen can be incorporated within growing films, thereby impacting their physical properties and even stimulating room temperature recrystallization.6−11 Under more aggressive conditions, cogeneration of hydrogen gas during electrodeposition can be utilized to template the growth of 3-D Cu foams for use in thermal management, bonding, and electrocatalysis.12 Excursions to such negative potentials can also lead to cathodic corrosion that is likely related to hydride formation.13

Of particular interest is the finding that Cu is the only elemental electrocatalyst capable of efficiently reducing CO2 to hydrocarbons and oxygenates. In a related fashion, Cu–H functionalized molecules have a long history in organic synthesis as potent reaction centers for CO2 reduction.14−16 For such multistep hydrogenation reactions, competitive and coadsorption between CO, H, and other reaction intermediates play a central role and likewise are known to induce and guide potential-dependent mesoscale rearrangements of Cu surfaces.13−15,17−20 The interaction of CO with Cu surfaces has received substantial attention, while the role of adsorbed hydrogen and its interactions with CO in various hydrogenation reactions remains understudied and unresolved.21 It is also noteworthy that some years ago UHV studies of hydrogenation reactions on hydrogen-dosed surfaces demonstrated that subsurface hydrogen species can serve as active intermediates although the possibility of such pathways has received limited attention in electrochemical systems.22−24 Studies of different synthetic pathways for producing bulk crystalline CuH yield different surface properties that speak to the complexity of the system and the need for further study.25 UHV studies of hydrogen adsorption on low-index Cu surfaces reveal the formation of two-dimensional surface hydride superlattices and also provide the earliest measurement of competitive adsorption dynamics between H and CO albeit at low temperatures.26−32 More recently, operando methods like electrochemical scanning tunneling microscopy (ECSTM), shell-isolated nanoparticle enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SHINERS), and electrochemical mass spectrometry (EC-MS) have been utilized to study H adsorption on copper surfaces in electrolytic environments.33−37 A complex, but stochiometric, (4 × 4) hydride overlayer structure was imaged on Cu(111) in sulfuric acid.33,34 Meanwhile EC-MS measurements indicate a potential regime where a saturated hydride phase is formed with a coverage of (0.67 ± 0.15) monolayers (ML) in 0.1 mol L–1 H2SO4.36 Asymmetric voltammetry arises from the slow formation of the hydride phase by proton reduction with development of a ≈1040 cm–1 vibrational band during the negative-going scan. Its subsequent desorption by hydrogen recombination occurs on the positive-going scan that is stimulated by anion adsorption (sulfate band at 1200 cm–1).35 Recent atomistic simulations indicate that hydrogen-induced reconstruction of Cu(111) creates Cu adatoms that facilitate both the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and CO2/CO reduction in acidic environments subject to competitive interactions in the operational environment.33,38,39

In the present study, the formation of surface hydride on Cu(111) in 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4 is examined with proton reduction partitioned between hydride formation and HER. Voltammetric EC-MS measurements reveal at least two electrochemical peaks related to surface hydride formation on Cu(111), that involve populating different surface sites and/or phase transitions and reconstructions, while subsequent hydride decomposition at more positive potentials is associated with a single voltammetric wave. In contrast to studies with sulfate (SO42–) or chloride (Cl–), perchlorate ions (ClO4–) are not expected to specifically adsorb on copper surfaces, yet measurable oxidative current is still observed at potentials that overlap with hydride decomposition at higher potentials.35,40 Chronoamperometric EC-MS measurements were employed to quantify the Hads coverage with particular attention given to partitioning the hydride decomposition between Hads recombination versus electrochemical oxidation back to hydronium.

Experimental Section

Preparation of the Cu(111) Electrode

Before EC-MS measurements were conducted, the 5 mm diameter Cu(111) crystal was mechanically polished using an alumina slurry to achieve a 0.05 μm finish. This was followed by rinsing and sonicating the specimen in water multiple times to eliminate any remaining alumina particles. Subsequently, the Cu(111) disk was electropolished for 5 min at +1.6 V vs a Pt counter electrode, in 85% H3PO4. The Cu(111) surface was positioned facing upward and opposite of the gas-generating Pt gauze that was ≈6 cm away. Following ≈10 min of electropolishing, the disk was rinsed and then shielded with H2O until being dried with flowing Ar immediately before being mounted in the mass spectrometer.

Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry Measurements

EC-MS was performed using a thin layer cell configuration (Spectro Inlets*).41,42 Experiments were performed in freshly prepared Ar purged 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4 electrolyte (70% HClO4, 99.999% trace metal basis from Sigma-Aldrich). Glass side arms on opposite sides of the working electrode contained an Ir wire counter electrode and a capillary consisting of a Pt wire submerged in H2 saturated electrolyte to form a trapped H2 bubble quasi-reversible hydrogen reference electrode (RHE), respectively. The Ir counter electrode was placed >3 cm away from the entrance to the working electrode compartment to minimize any contribution from the counter-reactions. To mitigate oxidation and dissolution of the Cu(111) working electrode that will occur under open circuit conditions, potentiostatic control at 0 V vs RHE (to be assumed throughout) was imposed immediately following wetting of the three electrodes by the electrolyte. For subsequent rest or idle periods between electrochemical measurements, the working electrode was typically poised at 0.175 V. A Biologic SP-200 potentiostat was used for all electrochemical measurements. The EC-MS and electrochemical data were collected on the same computer enabling effective time synchronization between the two measurements. For cyclic voltammetry measurements, the baseline of the 2 amu EC-MS signal was subtracted using a linear profile with the slope determined by averaging the signal over 2 s before and after completion of the voltammetric scan.

For negative step potential pulse measurements, the 2 amu baseline was zeroed by averaging the signal for ≈2 s prior to initiating each potential step (EPulse) (Figure S1). The approach is congruent with the absence of steady-state HER occurring at the rest potential of 0.175 V (ERest). For positive step potential pulse measurements, determining the background for the 2 amu H2 measurement is more difficult. Fortunately, extended observation of the MS baseline drift indicates that, absent an obvious input source, the baseline for 32 amu (O2) and 2 amu (H2) change at the same rate. Accordingly, the 32 amu signal is used to provide an estimate of the drift in the H2 background levels. The utility of this alignment is evident in Figure S2 where the drift in the 32 amu signal was used to estimate the baseline signal for 2 amu (red line). It is noteworthy that when ERest > 0 V, where no HER occurs, the 2 amu signal drops to the baseline, overlapping the 32 amu baseline signal, supporting this strategy.

The 2 amu signal was converted to H2 flux following the strategy discussed previously.36 In short, calibration curves were generated under steady-state HER conditions that use the current, converted to H2 flux, to calibrate the 2 amu signal using either Cu or Pt electrodes. The electrolyte thickness separating the working electrode from the membrane entrance to the quadrupole mass spectrometer was determined using impulse measurements discussed previously and was typically found to be ≈120 μm.36,43

Impedance measurements of Cu(111) mounted in the EC-MS were conducted in 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4 using a 10 mV perturbation with a range of 100 mHz to 100 kHz using 10 points per decade. Measurements were performed as the potential was advanced from 0.2 to −0.25 V in 50 mV increments. The Nyquist plots (Figure S3) were fit to a simplified Randle circuit, and the results are presented in Table S1.

Results and Discussion

Cyclic Voltammetry on Cu(111) in 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4

Recent EC-MS studies have revealed the formation of surface hydride on Cu(111) in various acid electrolytes.35 For 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4, hydride formation is associated with two overlapping voltammetric reduction peaks, e.g., at −0.22 and −0.26 V for 10 mV s–1, in Figure 1a while only a single peak is observed in electrolytes containing SO42–, Cl– and PO43–. The origin of the two voltammetric peaks in perchloric acid is unresolved although recent theoretical work on H adsorption on Cu(111) indicates a series of phase transitions with increasing H coverage.33,38 For a pH of 1, an equilibrium H coverage of 0.56 ML is predicted between −0.200 and −0.241 V followed by an increase in coverage to 0.75 ML between −0.250 and −0.426 V coincident with the development of (4 × 4) superlattice seen in EC-STM experiments.34,40 At more negative potentials, surface reconstruction occurs with the formation of an ordered (4 × 4) array of Cu adatoms stabilized by the higher H coverages >0.94 ML. It should be noted that the computational uncertainties with the DFT exchange correlation functional, and the solvation and electrolyte models are such that the stated potentials could be off by up to ±0.3 V.33

Figure 1.

(a) Voltammetry and (b) 2 amu H2 flux measured at different scan rates in the thin layer EC-MS cell reveal hydride formation and decomposition for Cu(111) in 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4.

Variation of the scan rate from 5 to 50 mV s–1 induces a ≈ −50 mV shift in the reduction wave peak potentials indicative of a kinetic constraint on surface hydride formation (Figure 1). This shift is not due to ohmic losses, as EIS measurements reveal the solution resistance to be 20.6 ± 0.6 Ohms (see Figure S3 and Table S1), which would result in <1 mV shift in the peak potential for the peak current measured in the 50 mV/s scan. Continued voltammetric scanning at rates ≥20 mV s–1 reveals that hydride decomposition is not completed during the first cycle, and as a result, the peak proton reduction current to reform the hydride during subsequent cycles is noticeably diminished (Figure 1a). Additionally, a small reduction peak develops near −0.05 V, which is associated with the incomplete removal of the hydride phase during the first voltammetric cycle. The magnitude of the peak at −0.05 V increases with scan rate, when cycling without interruption, as shown in Figure S4. During the return scan to positive potentials, the EC-MS reveals evolution of H2 at potentials above 0.0 V due to the decomposition of the hydride phase by Hads recombination (Figure 1b) with the onset and rate of the decomposition being sensitive to the presence of anions and more specifically their strength of adsorption.35 Strongly adsorbing Cl– shifts hydride decomposition to potentials negative of 0.0 V, Figure S5, while the much weaker interaction with ClO4– is such that the Hads combination process is still underway at the upper vertex at 0.2 V. The final increments of Hads do not leave the surface until the second negative-going scan as evidenced by the measured H2 flux (Figure 1b), better visualized when plotted vs time (Figure 2). For faster scan rates, even less decomposition of hydride occurs by the end of the first cycle (Figures 1b, S6, and S7). Detection of H2 from recombination is apparent at potentials > −0.05 V (Figure 1b) with the final increments that are detected on the negative scan reflecting the slow kinetics of decomposition and diffusional lag in H2 collection.

Figure 2.

Traces of (a) potential, (b) current, and (c) H2 flux vs time from 10 mV s–1 voltammetry shown in Figure 1. (d) Integration of (b) current and (c) H2 flux as well as their difference in the form of atomic hydrogen (mol cm–2). (e) Decomposition of the hydride is quantified by the charge associated with oxidation of Hads to H3O+ (shaded red in (b)) and the amount of H2 produced by recombination (shaded blue in (c)). The analyses for the initial and final cycle at different scan rates in Figure 1 are summarized (e) with the fractional Hads surface coverage indicated on the top of the respective bars. The group of two dashed lines indicates the potential region for onset of HER.

An alternative pathway to hydride decomposition by recombination is oxidation to H3O+. As an upper bound the measured anodic charge, denoted qH Oxidation, of (48 ± 14) μC cm–2 for this process corresponds on average to removal ΔθH of (0.17 ± 0.05) ML of Hads (Figure 2b,e) following eq 1,

| 1 |

where q is the charge density (C/cm2), z is the number of electrons transferred (mol e–/mol H), F is Faraday’s constant (C/mol e–), nH+ is the moles of H+ produced (mol H/cm2), and ρCu(111) is the atomic surface density of Cu(111) which is 2.935 nmol/cm2.

The possibility that Hads displacement by recombination to H2 is driven by the adsorption of trace anion contaminants was evaluated. The most likely contaminants are Cl– and PO43– with the former being an impurity in the as-received perchloric acid and the latter being carried over from electropolishing. Voltammetry, at 5 mV s–1 following titration of 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4 with 100 μmol L–1 HCl, reveals that Cl– adsorption drives decomposition of the hydride phase by Hads recombination, which peaks at −0.08 V before reaching completion below 0 V (Figure S5a). Halide addition also shifts hydride formation to more negative potentials, with the peak current only being reached near −0.3 V as the adsorbed Cl– must desorbed before the hydride can form. For a more dilute Cl– concentration of 10 μmol L–1 (Figure S5b), halide adsorption and hydride decomposition shift to more positive potentials. Both the current and EC-MS peaks split into two broad but distinguishable events. The first is centered near −50 mV with the second near +75 mV with the peak separation reflecting the mixed control kinetics associated with the transport-limited halide flux relative to the scan rate. In contrast, Cl– desorption and hydride formation on the negative-going scan appear as a single wave, indicating a saturated halide surface coverage is already present at this point in the experiment. The hydride formation peak shifts slightly positive to −0.275 V consistent with thermodynamic expectations for Cl– desorption at the more dilute concentration. Finally, for the 1 μmol L–1 Cl– titration both the voltammetry and EC-MS H2 flux profile (Figure S5c) are similar to that in neat 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4 although some differences remain. During the positive sweep the onset of Cl– adsorption between −50 and −25 mV is followed by mass transport-limited accumulation which displaces the hydride at a fixed rate of ≈ 0.15 nmol s–1 cm–2 that is sustained to the upper potential limit. In contrast, in Cl– free solution (Figure 1a), the primary anodic wave and hydride decomposition peak at 5 mV s–1 occur at a much more positive potential near +0.1 V. A small oxidative adsorption wave is evident near ≈ −0.04 V that reflects some change in the hydride phase prior to the onset of its decomposition. Interestingly, a similar peak develops in Cl– containing media that was ascribed to a phase transition in the Cl– adlayer however in that experiment the feature only appears after multiple voltammetric cycles.44,45 Further work will be required to understand the nature of this small feature.

Integration of the voltammetric current and H2 flux, following baseline subtraction and conversion of the 2 amu signal (see the Experimental Section), provides an avenue to track H coverage with time and assess the total collection ability of the thin layer EC-MS cell as summarized in Figure 2. Care must be taken in evaluating the baseline and contributions from possible background reactions, such as residual O2 reduction. For fast scan rates and low Faradaic currents, the electrode charging capacitance is significant but largely nulled by integration over each complete voltammetric cycle. At slower scan rates, the parasitic current due to transport-limited reduction of residual O2 is evident in the background offset of the voltammetric current. For scan rates <10 mV/s this is compensated by subtracting a fixed current offset as indicated in Figures 2 and S6. Following this correction and considering H2 and H3O+ as the only reactants involved, the H coverage at a given potential is estimated from the difference of the integrated current and H2 flux from the EC-MS signal converted to nH or θH (using ρCu(111)) respectively as shown in Figure 2d and summarized in Figure 2e. Implicit cancellation of the pseudocapacitance contribution following a complete voltammetric cycle should lead to closure of the Hads coverage vs potential relationship consistent with total EC-MS collection of H2 generated under these conditions. The slow kinetics of recombination hinder such closure for the first voltammetric cycle, although with continuing cycling a closed loop steady-state result is observed in Figure S7.

The proton reduction charge that goes to form Hads, prior to MS detection of the onset of H2 from the HER, (denoted in Figures 2 and S6 by the two vertical dashed lines) corresponds to a maximum possible Hads coverage of (0.82 ± 0.02) ML regardless of scan rate or cycle number. Comparison of estimated hydride coverage at the HER onset potentials of −0.226, −0.245, −0.260, and −0.290 V for scan rates of 5, 10, 20, and 50 mV s–1, respectively, for different scan rates are summarized in Figures S6–S7 and Table S2. The threshold also aligns with the inflection evident between the two voltammetric current peaks that comprise the reduction wave. The subsequent onset of HER is consistent with a further increase in H coverage that might induce the surface-subsurface H phase transition and/or reconstruction of Cu(111) seen in EC-STM experiments wherein the extracted Cu adatoms serve to coordinate and catalyze the hydrogen evolution reaction.33,34

Integrating the H2 flux from −0.050 V on the positive voltammetric sweep until the background signal is reached again yields between 0.6 nmol cm–2 and 0.9 nmol cm–2 of H2. This corresponds to a conservative estimate of fractional Hads coverage (θH) between 0.36 and 0.61 ML (Figure 2e) depending on the scan rate and negative vertex potential. The integrated H coverage measured for the final voltammetric cycle at 20 and 50 mV s–1 is larger than the preceding scans since the potential was held for an extended period at the upper vertex after the voltammetric sweep was finished while collection of the evolved H2 continued. The result is congruent with the incomplete decomposition of the hydride phase seen at higher scan rates due to limited recombination kinetics and insufficient time spent at the decomposition potentials. An upper bound on θH can be estimated by summing the oxidative and H recombination portions for each respective scan rate seen in Figure 2e. The increase in θH from 0.64 to 0.82 ML with scan rate is evident however the increase also correlates with the shift to more negative vertex potentials where an increase in Hads coverage is predicted by theory.33 More negative vertex potentials were used to ensure that the transition between hydride formation and bulk HER was reached when using faster scan rates.

The impact of extended polarization at negative potentials where the hydride is formed was examined by voltammetry where the initial potential was held at −0.325 and −0.35 V for 30 s, respectively. As shown in Figure 3 the voltammetric kinetics of hydride decomposition following extended polarization at negative potentials are substantially faster than seen for voltammetry initiated at positive potentials on a hydride-free surface, i.e., Figures 1 and 2. Following pretreatment at −0.325 V, Figure S8, the peak potentials for the first oxidative wave and EC-MS hydride decomposition are downshifted to 0.126 V (≈34 μC cm–2 or ≈0.35 nmol cm–2) and ≈0.135 V (1.59 nmol cm–2), respectively. For pretreatment at a slightly more negative potential of −0.35 V, the respective peaks in Figure 3 are downshifted further to 0.107 V (≈28 μC cm–2 or ≈0.29 nmol cm–2) and ≈0.118 V (1.29 nmol cm–2), respectively. For both sets of experiments, the subsequent voltammograms with continuous scanning yield the same positive shift in peak positions to ≈0.165 and ≈0.175 V, respectively. If the oxidative charge is ascribed solely to Hads oxidation to hydronium while the H2 flux is assigned to Hads desorption by recombination the summation gives a fractional Hads coverage of 0.66 ML at −0.325 V and 0.75 ML at −0.350 V, subject to the scan rate used. These values are well aligned with the predicted potential-dependent coverage from theoretical calculations detailed earlier.33 Accordingly, excursions to more negative values lead to higher Hads coverages and H-induced reconstruction of the Cu(111) that collectively impact the onset and acceleration of the HER. For subsequent cycles, the maximum Hads coverage evaluated from the voltammograms decreased to (0.6 ± 0.01) ML, Figure 3, and (0.54 ± 0.015 ML), Figure S8, respectively, which reflect kinetic hindrance in hydride formation during voltammetric cycling. At more negative potentials where the coverage exceeds 0.75 ML, theory predicts a reconstruction of the existing (4 × 4) structure with the formation of adatoms, dimers, and related vacancy structures that maintain the (4 × 4) periodicity.33 The adatoms and vacancies facilitate both higher Hads coverage and enhanced reaction kinetics. Recent computational work indicates that adsorbed H is required and works synergistically with CO to create sites of CO-bound Cu atoms that sit 0.1 nm above the top surface accounting for surface reconstruction that accompanies CO2RR.39 The increased Hads coverage and enhanced hydride decomposition and oxidation characteristics following aging, Figures 3 and S8, and/or during excursions to more negative potentials, <−0.325 V, Figure 2, are consistent with this picture.

Figure 3.

(a) Cyclic voltammetry of Cu(111) in He-saturated 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4 and the accompanying (b) H2 flux measured by EC-MS following an initial 30 s pretreatment at −0.350 V. The H2 flux and oxidative peak on the anodic sweep were (c) integrated and converted to nH (nmol cm–2) and are labeled above the bar graph in terms of the Hads fractional surface coverage θH.

Chronoamperometric EC-MS Measurements in 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4

Potential pulse EC-MS measurements were used for a more complete quantitative analysis of the transient and steady-state behavior associated with surface hydride formation and decomposition.36 The experiment involved stepping the potential from an initial rest state, ERest = 0.175 V to a more negative potential, EPulse for 2 min and then stepping back to ERest for 2 min. The EPulse value was then progressively advanced in −25 mV increments (Figures 4 and S1). The chronoamperometric experiment mitigates convolution of the H2 diffusional lag from the dynamic potential scan used in voltammetry. Sequential chronoamperometric transients for each pulse cycle between EPulse and ERest in He-saturated 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4 electrolyte are superimposed in Figure 4a. Starting from EPulse of −0.05 V, the steady-state current densities at EPulse and ERest remain roughly < −5 μA cm–2 and ≈ −2 μA cm–2, respectively. These negative currents arise from the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) due to trace (on the order of pmol L–1 s–1) O2 flux, possibly from leakage through various joints and connections of the EC-MS cell, as no change in H2 flux was detected via the mass spectrometer (Figure 4b).36 The current density when EPulse = -0.1 V increases to ≈ −5.5 μA cm–2, consistent with an increase in the steady-state HER rate (Figure S9). Stepping to −0.150 V increases the steady-state HER rate modestly, although a notable change in the first ≈25 s of the current transient is observed (Figures 4b and S9). Compared to −0.150 V, the time to reach a steady-state current increases at −0.175 and −0.200 V before decreasing for EPulse ≥ −0.225 V. The slower time constant for the −0.150 and −0.225 V transients is associated with the nucleation and growth of the surface hydride phase superimposed on proton reduction to H2 and double-layer charging. An additional contribution from anion desorption is possible although this is believed to be unlikely for perchlorate electrolytes in contrast to the measurable influence of sulfate, phosphate, or chloride ions.36 Pulses in the 100 μmol L–1 HCl + 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4 electrolytes show similar behavior albeit shifted negatively ≈ −75 mV due to inhibition of hydride formation by the adsorbed chloride (Figure S10). This results in a more convolved current transient (left inset of Figure S10a) that involves the dynamics and additional charge necessarily associated with the sequence of Cl– desorption and the formation of hydride. Comparing the transient charge at a pulse potential of −0.3 V (−288 vs −253 μC cm–2 for Cl vs HClO4, vide infra) reveals −35 μC cm–2 of additional charge due to Cl– desorption. Likewise, hydride formation in 0.1 mol L–1 H2SO4 involved a transient charge of −275 μC cm–2 where the excess charge relative to 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4 is attributed to sulfate desorption (Figure 5a in ref (36)).

Figure 4.

(a) Chronoamperometry and (b) H2 flux during potential pulse measurements on Cu(111) in He-saturated 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4. The horizontal dotted line in (a) indicates zero current. The horizontal dashed lines in the H2 flux plot indicate the steady-state HER (HERSS) flux at the three most negative EPulse as determined by averaging the last 60 s of the flux during EPulse. The vertical dashed line indicates the transition to ERest. The insets in (a) magnify the transient components of current for both EPulse a ERest and the inset in (b) magnifies the transient period at ERest associated with the decomposition of hydride to H2 via Hads recombination.

Upon returning to ERest an oxidative transient current is observed (Figure 4a right inset), with the duration and charge increasing as the potential is stepped from more negative EPulse values between −0.05 to −0.225 V. The oxidative charge reflects a combination of double-layer charging, anion adsorption, and/or hydride decomposition by oxidation to hydronium. As noted above, although anion adsorption on Cu surfaces is well established for sulfate or halide electrolytes, evidence for specific perchlorate anion adsorption is at best ambiguous. Significantly, a recent STM study of a water-dosed Cu(111) surface in cryogenic vacuum environment revealed ordered adlayers that were ascribed to water and hydronium structures, a subset of which were similar to those observed in ECSTM studies.40,46−48 Inspection of the oxidative current transients at ERest reveals that the time to reach the steady-state background current increases from 5 to 20 s as Epulse is made more negative. However, when EPulse < −0.225 V an inversion and decrease in the time constant is evident with the transient lifetime dropping to 15 s following polarization at EPulse of −0.3 V. The acceleration of the oxidative process (in 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4) following more negative pulse potentials is consistent with that seen in the related voltammetric experiments, Figures 3 and S8. One possible explanation is that Cu adatom formation driven by higher hydride coverages formed at more negative potentials leads to accelerated hydride decomposition with the step back to the rest potential.

Interestingly, the accelerated hydride decomposition seen in 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4 is not evident following titration with 100 μmol L–1 Cl–, nor is it evident in prior sulfuric acid experiments. In the presence of Cl– the oxidative current transient increases abruptly when Epulse is −0.2 V and effectively saturates for Epulse < −0.225 V consistent with completion of the hydride phase over a small potential window (Figure S10a and right inset). Also of interest, the oxidative current transients in the presence of Cl– (Figure S10b) do not accelerate when stepping from more negative potentials, e.g., −0.3 V, in contrast to that observed in pure 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4. This might be attributed to anion-facilitated quenching of the elevated adatom population associated with the hydride phase formed at more negative potentials.

Following 120 s of polarization at EPulse the potential is stepped back to ERest and the increase in H2 flux provides an unambiguous signature of hydride formation by virtue of its decomposition via H recombination to H2 at ERest (Figure 4b and right inset). Notably, this occurs well positive of 0.0 V. The hydride decomposition peak at ERest continues to grow as EPulse is stepped more negative with the integrated H2 flux as a function of EPulse shown in Figure S11. An inflection, evident near −0.225 V, is suggestive of a plateau or phase boundary in the Hads coverage. Hydride formation at EPulse overlaps the onset and development of HER with the latter reaching a steady-state rate within the first 30 s of the 120 s dwell period. This decay rate is accelerated substantially in the presence of Cl– with its strong absorption stimulating Hads recombination to occur in nearly half of the time (10 s) for all pulse potentials (Figure S10b). This observation also supports the attribution of the sluggish decay curve, in the absence of halide, to the slow decomposition kinetics of hydride rather than H2 diffusion across the thin layer of the electrolyte. In pure 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4 and EPulse < −0.2 V, the additional increase in peak height upon stepping to ERest partly reflects an increase in Hads coverage but is convolved with residual H2 diffusing across the electrolyte following steady-state HER at EPulse (Figure S11). The decay associated with this residual H2 significantly affects the shape of the hydride envelope. Quantitative analysis is further complicated by the competitive, first-order oxidation of Hads to H3O+. Nonetheless, the more rapid decay in H2 flux following polarization at EPulse values < −0.275 V speaks to an increase in the kinetics for Hads recombination and/or the Hads oxidation reaction. The acceleration is most likely related to H-induced reconstruction of the surface that results in more reactive low-coordinate Cu adatoms at higher Hads coverages.33

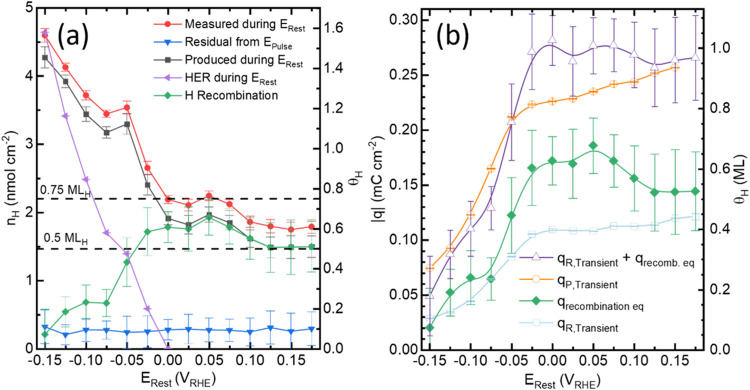

Quantitative Analysis of Hydride Coverage

The hydride coverage can be quantified using the steady-state approximation for the HER, as done previously in similar experiments with sulfuric acid electrolyte.36 In contrast to experiments in sulfate- or chloride-containing media, chemisorption of perchlorate is negligible with no order anion layers reported in the plurality of ECSTM studies therefore, no charge will be assigned to anion adsorption.40,47 For chronoamperometry, separating the steady-state charge (qP,SS, qR,SS) from the total measured charge (qP,Total, qR,Total) for both EPulse and ERest (Figure 4a,b), isolates the transient charges (qP,Transient, qR,Transient) associated with reductive hydride formation at EPulse and its subsequent oxidation at ERest, respectively. The steady-state HER approximation is evaluated by averaging the current over the final 60 s of Epulse or Erest and multiplying by the total pulse or rest time (120 s each) to obtain the charge (qP,SS, qR,SS). As shown in Figure 5, the approximated steady-state charge during EPulse or ERest is subtracted from the total measured charge to yield the transient charge, qP, Transient or qR,Transient, respectively. Initially, for EPulse ≥ −0.175 V, the transient charges for EPulse and ERest are approximately equal to opposite polarity, congruent with reversible capacitive charging of the interface. The onset of hydride formation introduces asymmetry in the net transient charge, as captured in Figure 5b. Specifically, |qP,Transient/qR,Transient| increases from around 1 at EPulse = −0.05 V (prehydride formation) to a plateau of ≈2 at −0.225 V, due to surface hydride formation. This charge analysis ignores the contribution of double-layer capacitance associated with stepping between EPulse to ERest. However, negligible hydride formation occurs prior to −0.05 V and thus an upper bound for the corresponding net change associated with hydride formation is evaluated based on the difference between the transient charge at −0.05 V (hydride-free) and −0.225 V (hydride-covered), giving (−218 ± 8) μC cm–2 of charge to reduce H+ to surface hydride (Figure 5c). Normalizing this charge to θH on Cu(111) yields a saturated coverage of (0.77 ± 0.03) ML. Assuming that the decomposition of surface hydride is a competitive process between oxidation and recombination reactions, the contribution of oxidation can be determined by measuring the background corrected oxidation charge when stepping from EPulse to ERest. At its maximum, this yields ΔqR,Transient (103 ± 2) μC cm–2 (Figure 5b) that corresponds to a loss of (0.36 ± 0.01) ML of H (Figure 5c). The contribution from the H recombination process is evaluated directly from the 2 amu EC-MS measurement.

Figure 5.

(a) Total (qP,Total and qR,Total) and steady-state (qP,SS and qR,SS) chronoamperometric charge and (b) their difference, the transient charge (qP,Transient and qR,Transient), for EPulse and ERest during negative step potential pulse measurements in 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4 (Figure 4). (c) Total H coverage determined from either the background corrected hydronium reduction wave, Hreduced+, or the sum of hydride recombination, Hrecombined, and Hads oxidation to hydronium, Hoxidized. The transparent background for each curve represents the standard deviation. Also plotted is the coverage (denoted as “theory” in the legend) predicted by computational simulations from Cheng et al. for pH 1 electrolyte.33

Analysis of the H2 flux also involves partitioning the measured H2 (H2,Total) into contributions from the HER (H2,HER) and hydride decomposition by H recombination (H2,Hydride) (Figure S12). Previous work utilized the total collection capacity of the EC-MS platform41 to deconvolve these terms. It was assumed that steady-state HER at Epulse is rapidly (instantly) attained, with the EC-MS detection delayed due to H2 diffusion across the thin electrolyte layer.36 The EC-MS measurement is particularly effective in revealing the onset of hydride formation as the HER at Erest drops rapidly to zero while the Hads recombination to yield H2 takes several seconds, Figures 4b, S9, and S11. The integrated result of the small H2 quantity detected, following polarization at −75 mV, is consistent with assigning the transient charge at −0.05 V to the capacitance, Figure 5b. Integration of the decomposition peak upon stepping to ERest shows a monotonic relationship between hydride coverage and EPulse between −0.10 to −0.25 V, Figure 5c. A plateau is evident between −0.25 and −0.3 V, corresponding to a hydride coverage of (0.54 ± 0.05) ML. This is lower than the 0.67 ML observed in 0.1 mol L–1 H2SO4 using the same procedures which reflects the role of sulfate adsorption in spurring the recombination reaction.36

Deconvolving the charge contributions during negative potential pulses in 100 μmol L–1 HCl + 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4 (Figure S13) requires consideration of Cl– desorption during hydride formation and Cl– adsorption during hydride decomposition. As noted earlier, the charge associated with hydride formation in the presence of Cl– exceeds that for neat perchloric acid by ≈35 μC cm–2. Studies of Cl– adsorption on Ag(111) indicate an electrosorption valancy of 0.44 and based on the similarity between the pzc of Cu and Ag this value is adopted.49 Accordingly, the excess charge of ≈35 μC cm–2 corresponds to a fractional Cl– coverage θCl of 0.28 ML compared to 0.33 ML expected for a (√3 × √3)R30° overlayer structure that can be taken as a first-order estimate based on reported adlayer surface structures.44,50 Alternatively, an inverse analysis using the electrosorption normalized charge for the (√3 × √3)R30° adlayer of ≈41 μC cm–2 can be used to provide a charge-based estimate of the hydride coverage at −0.35 V, θH of 0.89, not surprising since double-layer charge was not considered. It should also be noted that the coexistence of H and Cl adlayer structures proposed in recent theory might lead to variation in the electrosorption valancy that will need to be considered.51 Meanwhile the θH determined by integration of H2 flux during desorption in the presence of Cl– appears to converge to 0.75 ML (Figure S13c), while that for perchloric acid does not exceed 0.6 ML, supporting the idea that Cl adsorption favors H recombination over oxidation.

In the absence of anion adsorption, the sum of the oxidative and recombination components associated with hydride decomposition measured at ERest can be compared with the proton reduction charge used to form the hydride (Figure 5c). Good agreement between the metrics is achieved for ≥ −0.225 V where ≈0.75 ML of Hads is expected. This is further corroborated by the 0.75 ML of H measured through recombination when 100 μmol L–1 HCl is present in 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4. At more negative potentials, the transient charge at EPulse plateaus, whereas the sum of oxidation and recombination increases slightly to ≈1 ML by −0.3 V. However, this is accompanied by an increase in standard deviation that weakens the significance of the increase. Recent computational studies of H adsorption on Cu(111) indicate two domains of hydride stability with a coverage of 0.56 and 0.75 ML that correspond to slightly different (4 × 4) periodic structures similar to that observed by ECSTM.33 The predicted coverage (Figure 5c, “Theory”) overlaps the present and previous EC-MS studies in perchloric and sulfuric acid. The chief distinction between sulfuric acid, hydrochloric acid, and perchloric acid is the strength of anion adsorption; specifically, sulfate and/or chloride adsorption favors hydride decomposition by recombination, whereas the absence of perchlorate adsorption results in a measurable increase in the amount of Hads removed by oxidation.

Impact of ERest on Hydride Decomposition 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4

To further explore hydride decomposition and its partitioning between Hads recombination to H2 versus oxidation to hydronium, a similar set of pulse experiments were performed where Erest was changed as EPulse was held constant (Figure 6). For this experiment, EPulse was chosen to be −0.25 V, which corresponds to the well-defined plateau in hydride coverage established in the previous experiment. The detailed potential program is shown in Figure S2 with the substrate initially poised at 0.175 V, where the surface is known to be hydride-free. The chronoamperometric, Figure 6a, and H2 flux, Figure 6b, measurements during repetitive stepping to EPulse of −0.25 V demonstrate good reproducibility while the choice of ERest significantly impacts the rate and nature of hydride decomposition. For the first ERest value of −0.15 V both current and H2 flux decay to a new steady-state HER value (Figure 7a “HER During ERest”). As ERest is sequentially increased in +25 mV increments, up to −0.025 V the current and H2 flux transients become more sluggish. Once ERest > −0.025 V a clear uptick in H2 flux (inset shown in Figure 6b) from hydride decomposition by recombination accompanies the step from EPulse to ERest. At the same time a slow transient oxidative process is observed in Figure 6c that reflects the tail of double-layer charging and Hads oxidation to hydronium relaxes, decaying over ≈80 s at −0.025 V (compared to ≈30 s at 0.175 V), to a steady-state reduction current associated with residual oxygen.

Figure 6.

(a, c) Chronoamperometry and (b, d) H2 flux during variable ERest measurements on Cu(111) in 0.1 mol L–1 HClO4. The inset in (b) magnifies the 2 amu hydride decomposition peak, while the magnified current and H2 flux profile for the entire ERest cycle are presented in (c) and (d), respectively. The horizontal dashed line in (b) represents the average steady-state H2 flux during the EPulse. The gray dashed lines in (d) reflect the steady-state HER rate at ERest found by averaging the last 5 s of the H2 flux for each ERest.

Figure 7.

(a) Total and partitioned quantities of nH determined via the EC-MS and (b) charge analysis from (Figure 6a) as a function of ERest. The qrecombination equivalent (eq) (green diamonds) in (b) is the hydride charge equivalent that is not realized due to the loss of H2 by recombination, as measured by EC-MS (a). The error bars represent the standard deviation of the measurement.

Advancing ERest further leads to acceleration of hydride decomposition with the H2 flux reaching the 0 nmol s–1 cm–2 baseline well within the 120 s duration for all ERest > −0.025 V. The 0 nmol s–1 cm–2 baseline is helpful in quantifying the HER kinetics that are otherwise obscured by the residual oxygen reduction reaction. Indeed, the H2 flux approaches zero at 0.0 V, consistent with this idea. Direct comparison between the current density and H2 flux at the end of ERest is shown in Figure S14 consistent with a residual oxygen reduction reaction current that increases from 1.5 μA/cm2 at 0.175 V to reach a transport-limited value of ≈3.0 μA/cm2 near 0.0 V. Integration of the EPulse current transient at −0.250 V following the initial step from an ERest of 0.175 V and applying the steady-state HER approximation yields 0.246 mC cm–2 of transient charge, in good agreement with the early negative step potential pulse measurements (Figure 5b). This charge equates to a Hads coverage of 0.78 ML based on the strategy used to determine Hreduced+ in Figure 5c.

As in earlier EC-MS analyses, the steady-state and total collection approximation is used to account for the different sources of H2 measured during ERest. This includes not only Hads desorption via recombination but also ongoing HER at ERest, along with the collection of H2 produced during EPulse but measured during ERest due to diffusional lag. The integrated H2 flux over the duration of ERest is given as “Measured during ERest” in Figure 7a. The contribution of H2, due to diffusional lag from the HER at EPulse, “Residual from EPulse,” is estimated by subtracting the total H2 measured during EPulse from the product of the steady-state H2 flux and pulse time at EPulse (Figure S15). This “Residual from EPulse,” is then subtracted from the “Measured during ERest” to leave the contribution “Produced during ERest” attributed to H recombination and HER as summarized in Figure 7a. Separation of H2 generated from Hads recombination versus HER at ERest can be approximated by assuming that the last 5 s of the EC-MS transient is representative of a steady-state HER flux (Figures 6d and S14) that multiplied by tRest gives the contribution “HER during ERest” shown in Figure 7a. The approach works well, although close inspection of the ERest transients between −0.1 and −0.025 V indicates the slow rate of H recombination may overlap with the 5 s averaging evaluation of the HER contribution (Figure 6d). With that qualification, subtraction of “HER during ERest” from “Produced during ERest” yields the amount of H2 generated by hydride decomposition via the recombination pathway as indicated by “H Recombination” in Figure 7a.

The analysis indicates a near monotonic dependence of Hads desorption by recombination as ERest is increased from −0.15 to −0.025 V. As ERest is increased further from −0.025 and 0.075 V, the amount of Hads desorbed by recombination rises to reach a maximum near 0.6 ML before settling to a value near 0.5 ML for ERest > 0.125. As the total amount of hydride to be decomposed is fixed, the transition or decrease in the amount desorbed by recombination is attributed to the onset of the oxidative removal of Hads as hydronium. This is consistent with ERest becoming greater than 0 V. Interestingly the transition also overlaps with the potential range where two minor peaks develop during cyclic voltammetric experiments as shown in Figure 1. The kinetic limitations on hydride decomposition are such that in voltammetric experiments the peak reaction is observed at much more positive potentials. For chronoamperometry, the potential and the time dependence are well captured by the H2 signal (Figure 6d) where hydride decomposition takes ≈100 s at −0.05 V but only requires 40 s at 0.075 V. The trend continues at higher ERest with the transition taking only ≈20 s at 0.175 V which is convolved with the time required for H2 to diffuse across the electrolyte to the MS entry port.

The charge transients (qP,Transient and qR,Transient) for the positive step potential pulse measurements (Figure 7b) were determined by following the same strategy used for the negative step potential pulse measurements, where the steady-state charge was subtracted from the total charge (Figure S16) for both EPulse and ERest. The steady-state currents were determined by averaging the current for the final 3 s of EPulse and ERest, respectively, and the charge was found by multiplying by the time of the pulse or rest (120 s each). As with the EC-MS analysis this assumes the steady-state processes are not influenced by transient events at the electrode surface. This may be a less accurate procedure for assessing the current compared to H2 flux, given that other phenomena may contribute such as parasitic ORR, double-layer, and/or adsorption-related pseudocapacitance. The experiment begins by first forming a hydride at −0.250 V that yields a qP,Transient of −0.246 μC/cm2 (not indicated in Figure 7b). For the first positive ERest step to −0.15 V the qR,Transient is only 30 μC cm–2. This increases to nearly 110 μC cm–2 for an ERest of −0.025 V with only modest increases thereafter. The qP,Transient associated with the next EPulse corresponds to reforming the increment of hydride decomposed on the previous ERest step. Assuming the reformed hydride phase after each EPulse is the same, the difference between qP,Transient (e.g., the charge for hydride formation) and its subsequent oxidative decomposition must equal the amount of hydride decomposed through the recombination to H2. The materials balance is examined by converting nH from recombination (“H Recombination” Figure 7a) to its charge equivalent, qrecombined equivalent. Combining this with qR,Transient for hydride decomposition by oxidation to hydronium enables a comparison to the hydride formation charge, qP,Transient. Assuming the hydride structure is conserved over multiple formation-decomposition cycles the sum of the two decomposition pathways should equal the charge needed to reform the hydride. The combination shows that complete decomposition of the hydride phase occurs at potentials > −0.05 V. Reasonable agreement between the charge and H2 flux measurements is encouraging especially considering the uncertainties in the charge analysis associated with residual oxygen reduction reaction, double-layer capacitance, and the assumption implicit in the steady-state analysis. Future exploration will focus on rectifying observed differences between chronoamperometry and EC-MS during potential pulse measurements. Of particular interest is the impact of anion adsorption on the partitioning of the decomposition reaction between oxidative desorption versus H recombination. Previous work with sulfuric acid indicated that strong anion chemisorption accelerates the rate of the recombination pathway, such that desorption is complete before the overpotential increases enough for the oxidative desorption channel to become significant. Conversely, the decrease in H recombination for ERest > 0.05 V (Figure 7) points to a potential dependent increase in hydride oxidation.

Looking beyond hydride formation and decomposition to its effect on hydrogenation reactions, two distinctive regimes of behavior may emerge. In the first instance formation of the hydride overlaps the potential region where many hydrogenation reactions occur and the hydride phase itself may serve as the catalytic template but perhaps also as an active reaction.22,23 A prime example for consideration is the reduction of oxygen (ORR) where product selectivity between hydrogen peroxide versus water is known to be a sensitive function of anion adsorption and surface structure.52,53 Indeed, the transitions in ORR product selectivity directly overlap the potential regime where hydride formation and decomposition occur motivating the need for further study.35,36,52,53 A second regime of behavior to consider involves cross-coupling between potential-induced hydride formation and its desorption with the hydrogenation reaction of interest. An example of this is CO2/CO reduction on Cu surfaces using pulsed potential, or pulsed current, schemes where the perturbation repeatedly transits the hydride formation and decomposition window.17,54 In this instance the binding energy of adsorbed hydrogen varies greatly during the process with hydride first being formed on the negative-going potential pulse while during the reverse step adsorbed hydrogen is available for further hydrogenation reactions but at a much lower energy cost.54

Conclusions

Surface hydride formation on Cu(111) in perchloric acid is associated with two reductive waves. Chronoamperometry measurements support theoretical predictions of a domain of uniform hydride coverage near 0.75 ML exists between −0.225 and −0.3 V.33 The inflection between the two voltammetric reduction waves is associated with reaching ≈0.8 ML of hydride followed by the onset of the HER. The latter is also congruent with computational predictions detailing the formation of low coordination sites that may be responsible for the increase in HER kinetics.33 Variation of the scan rate in cyclic voltammetry reveals two additional minor peaks centered near −50 mV likely associated with the destabilization/stabilization of the hydride phase. Above −0.050 V the surface hydride undergoes decomposition either by Hads recombination to H2 or by oxidation back to H3O+, the rate of the latter increasing with potential. Kinetic limitations of the oxidation reaction manifest in the displacement of the oxidation wave to higher potentials for higher voltammetric scan rates. This is also evident in chronoamperometry where compression of the qR time constants occurred as ERest increased from −0.025 to 0.175 V while the net oxidative charge was largely independent of the applied potential. Exposure to more negative potentials for longer times accelerates subsequent voltammetric hydride decomposition kinetics, presumably due to structural rearrangement and/or elevated Hads coverage. The overpotential required for hydride formation on Cu(111) may impact the onset of hydrogenation reactions. Likewise, the slow decomposition kinetics for hydride decomposition and the prospect of weakly bound Hads being available at more positive potentials have implications for the use of pulse potential activation of hydrogenation reactions.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed with funding from the CHIPS Metrology Program, part of CHIPS for America, National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce. We thank Sandra Young for help with metallographic preparation.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.4c12782.

The supporting information contains; continuous plots of the negative and positive potential pulse experiments, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, cyclic voltammetry (CV) where scan rate was modulated without pausing, CVs with varying concentrations of HCl present in the electrolyte , versions of Figure 2 for additional scan rates, a table tabulating values from Figure 2 and Figure S6, plots of maximum H coverage vs potential during CVs at different scan rates, CVs with negative potential holds prior to the first scan and corresponding H coverage, plots that zoom-in on current and H2 flux during potential pulses, negative potential pulse experiments with HCl in the electrolyte, plots of integrated H2 flux during ERest of negative step potential pulse measurements, quantities of nH measured by the EC-MS during negative potential pulse measurements, charges from negative potential pulse measurements, steady-state current density from the last 5 s of ERest during potential pulse measurements, total and steady-state H measured during EPulse for positive step potential pulse measurements, and total or steady-state charges from EPulse during positive step potential pulse measurements (PDF)

Author Contributions

Official contribution of the National Institute of Standards and Technology; not subject to copyright in the United States.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Footnotes

Certain commercial equipment, instruments, or materials are identified in this paper to specify the experimental procedure adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the materials or equipment identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

Supplementary Material

References

- Moffat T. P.; Braun T. M.; Raciti D.; Josell D. Superconformal Film Growth: From Smoothing Surfaces to Interconnect Technology. Acc. Chem. Res. 2023, 56 (9), 1004–1017. 10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Chen J.; Alghoraibi N. M.; Henckel D. A.; Zhang R.; Nwabara U. O.; Madsen K. E.; Kenis P. J. A.; Zimmerman S. C.; Gewirth A. A. Electrochemical CO2 -to-Ethylene Conversion on Polyamine-Incorporated Cu Electrodes. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4 (1), 20–27. 10.1038/s41929-020-00547-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Huang J.; Cai J.; Wei Y.; Cao A.; Liu B.; Lu S. In Situ/Operando Methods for Understanding Electrocatalytic Nitrate Reduction Reaction. Small Methods 2023, 7 (7), 2300169 10.1002/smtd.202300169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher D. P.; Gewirth A. A. Nitrate Reduction Pathways on Cu Single Crystal Surfaces: Effect of Oxide and Cl–. Nano Energy 2016, 29, 457–465. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.06.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera L.; Silcox R.; Giammalvo K.; Brower E.; Isip E.; Bala Chandran R. Combined Effects of Concentration, pH, and Polycrystalline Copper Surfaces on Electrocatalytic Nitrate-to-Ammonia Activity and Selectivity. ACS Catal. 2023, 13 (7), 4178–4192. 10.1021/acscatal.2c05136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumuro N.; Adachi T.; Yae S.; Matsuda H.; Fukai Y. Influence of Hydrogen on Room Temperature Recrystallisation of Electrodeposited Cu Films: Thermal Desorption Spectroscopy. Trans. IMF 2011, 89 (4), 198–201. 10.1179/174591911X13082997023873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amador L. L.; Rolet J.; Doche M.-L.; Massuti-Ballester P.; Gigandet M.-P.; Moutarlier V.; Taborelli M.; Ferreira L. M. A.; Chiggiato P.; Hihn J.-Y. The Effect of Pulsed Current and Organic Additives on Hydrogen Incorporation in Electroformed Copper Used in Ultrahigh Vacuum Applications. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166 (10), D366 10.1149/2.1211908jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaškelis A.; Jušk R.; Jačiauskien J. Copper Hydride Formation in the Electroless Copper Plating Process: In Situ X-Ray Diffraction Evidence and Electrochemical Study. Electrochim. Acta 1998, 43 (9), 1061–1066. 10.1016/S0013-4686(97)00282-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lousada C. M.; Fernandes R. M. F.; Tarakina N. V.; Soroka I. L. Synthesis of Copper Hydride (CuH) from CuCO3·Cu(OH)2 – a Path to Electrically Conductive Thin Films of Cu. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46 (20), 6533–6543. 10.1039/C7DT00511C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin D.; Murdoch H. A.; Chad Hornbuckle B.; Hernández-Rivera E.; Dunstan M. K. Investigation of Anomalous Copper Hydride Phase during Magnetic Field-Assisted Electrodeposition of Copper. Electrochem. Commun. 2019, 98, 96–100. 10.1016/j.elecom.2018.11.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumuro N.; Tohda K.; Yae S. Existing States of Co-Deposited Hydrogen in Electrolessly Deposited Copper Films from EDTA Complex Bath. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169 (12), 122505 10.1149/1945-7111/acaa63. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta A.; Rahaman M.; Luedi N. C.; Mohos M.; Broekmann P. Morphology Matters: Tuning the Product Distribution of CO2 Electroreduction on Oxide-Derived Cu Foam Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2016, 6 (6), 3804–3814. 10.1021/acscatal.6b00770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka R.; Uda M. Cathodic Corrosion of Cu in H2SO4. Corros. Sci. 1969, 9 (9), 703–IN27. 10.1016/S0010-938X(69)80101-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beamer A. W.; Buss J. A. Synthesis, Structural Characterization, and CO2 Reactivity of a Constitutionally Analogous Series of Tricopper Mono-, Di-, and Trihydrides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145 (23), 12911–12919. 10.1021/jacs.3c04170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch C.; Krause N.; Lipshutz B. H. CuH-Catalyzed Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108 (8), 2916–2927. 10.1021/cr0684321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q.; Lee Y.; Li D.-Y.; Choi W.; Liu C. W.; Lee D.; Jiang D. Lattice-Hydride Mechanism in Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction by Structurally Precise Copper-Hydride Nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (28), 9728–9736. 10.1021/jacs.7b05591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timoshenko J.; Bergmann A.; Rettenmaier C.; Herzog A.; Arán-Ais R. M.; Jeon H. S.; Haase F. T.; Hejral U.; Grosse P.; Kühl S.; Davis E. M.; Tian J.; Magnussen O.; Roldan Cuenya B. Steering the Structure and Selectivity of CO2 Electroreduction Catalysts by Potential Pulses. Nat. Catal. 2022, 5 (4), 259–267. 10.1038/s41929-022-00760-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amirbeigiarab R.; Tian J.; Herzog A.; Qiu C.; Bergmann A.; Roldan Cuenya B.; Magnussen O. M. Atomic-Scale Surface Restructuring of Copper Electrodes under CO2 Electroreduction Conditions. Nat. Catal. 2023, 6 (9), 837–846. 10.1038/s41929-023-01009-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng D.; Nguyen K.-L. C.; Sumaria V.; Wei Z.; Zhang Z.; Gee W.; Li Y.; Morales-Guio C. G.; Heyde M.; Cuenya B. R.; Alexandrova A. N.; Sautet P.. Structure Sensitivity and Catalyst Restructuring for CO2 Electro-Reduction on Copper ChemRxiv Catal. 2024 10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-z3dlp. [DOI]

- Wirtanen T.; Prenzel T.; Tessonnier J.-P.; Waldvogel S. R. Cathodic Corrosion of Metal Electrodes—How to Prevent It in Electroorganic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121 (17), 10241–10270. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagger A.; Ju W.; Varela A. S.; Strasser P.; Rossmeisl J. Electrochemical CO2 Reduction: A Classification Problem. ChemPhysChem 2017, 18 (22), 3266–3273. 10.1002/cphc.201700736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceyer S. T. New Mechanisms for Chemistry at Surfaces. Science 1990, 249 (4965), 133–139. 10.1126/science.249.4965.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceyer S. T. The Unique Chemistry of Hydrogen beneath the Surface: Catalytic Hydrogenation of Hydrocarbons. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001, 34 (9), 737–744. 10.1021/ar970030f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdellah A. M.; Ismail F.; Siig O. W.; Yang J.; Andrei C. M.; DiCecco L.-A.; Rakhsha A.; Salem K. E.; Grandfield K.; Bassim N.; Black R.; Kastlunger G.; Soleymani L.; Higgins D. Impact of Palladium/Palladium Hydride Conversion on Electrochemical CO2 Reduction via in-Situ Transmission Electron Microscopy and Diffraction. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15 (1), 938 10.1038/s41467-024-45096-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett E.; Wilson T.; Murphy P. J.; Refson K.; Hannon A. C.; Imberti S.; Callear S. K.; Chass G. A.; Parker S. F. How the Surface Structure Determines the Properties of CuH. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54 (5), 2213–2220. 10.1021/ic5027009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccash E. M.; Parker S. F.; Pritchard J.; Chesters M. A. The Adsorption of Atomic Hydrogen on Cu(111) Investigated by Reflection-Absorption Infrared Spectroscopy, Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy and Low Energy Electron Diffraction. Surf. Sci. 1989, 215 (3), 363–377. 10.1016/0039-6028(89)90266-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont C. L. A.; Persson B. N. J.; Williams G. P. Dynamics of Atomic Adsorbates: Hydrogen on Cu(111). Chem. Phys. Lett. 1995, 243 (5), 429–434. 10.1016/0009-2614(95)00814-K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G.; Plummer E. W. High-Resolution Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy Study on Chemisorption of Hydrogen on Cu(111). Surf. Sci. 2002, 498 (3), 229–236. 10.1016/S0039-6028(01)01765-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mudiyanselage K.; Yang Y.; Hoffmann F. M.; Furlong O. J.; Hrbek J.; White M. G.; Liu P.; Stacchiola D. J. Adsorption of Hydrogen on the Surface and Sub-Surface of Cu(111). J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139 (4), 044712 10.1063/1.4816515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korzhavyi P. A.; Soroka I. L.; Isaev E. I.; Lilja C.; Johansson B. Exploring Monovalent Copper Compounds with Oxygen and Hydrogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109 (3), 686–689. 10.1073/pnas.1115834109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorkendorff I.; Rasmussen P. B. Reconstruction of Cu(100) by Adsorption of Atomic Hydrogen. Surf. Sci. 1991, 248 (1), 35–44. 10.1016/0039-6028(91)90059-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang X.; Li J.; Xiong H.; Zhang H.; Xu Y.; Xiao H.; Lu Q.; Xu B. C–C Coupling Is Unlikely to Be the Rate-Determining Step in the Formation of C2+ Products in the Copper-Catalyzed Electrochemical Reduction of CO. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61 (2), e202111167 10.1002/anie.202111167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng D.; Wei Z.; Zhang Z.; Broekmann P.; Alexandrova A. N.; Sautet P. Restructuring and Activation of Cu(111) under Electrocatalytic Reduction Conditions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62 (20), e202218575 10.1002/anie.202218575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh T. M. T.; Broekmann P. From In Situ towards In Operando Conditions: Scanning Tunneling Microscopy Study of Hydrogen Intercalation in Cu(111) during Hydrogen Evolution. ChemElectroChem 2014, 1 (8), 1271–1274. 10.1002/celc.201402147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tackett B. M.; Raciti D.; Hight Walker A. R.; Moffat T. P. Surface Hydride Formation on Cu(111) and Its Decomposition to Form H2 in Acid Electrolytes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 10936–10941. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c03131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raciti D.; Moffat T. P. Quantification of Hydride Coverage on Cu(111) by Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126 (44), 18734–18743. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.2c06207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raciti D.; Cockayne E.; Vinson J.; Schwarz K.; Hight Walker A. R.; Moffat T. P. SHINERS Study of Chloride Order–Disorder Phase Transition and Solvation of Cu(100). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146 (2), 1588–1602. 10.1021/jacs.3c11812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng D.; Alexandrova A. N.; Sautet P. H-Induced Restructuring on Cu(111) Triggers CO Electroreduction in an Acidic Electrolyte. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15 (4), 1056–1061. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.3c03202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Gee W.; Sautet P.; Alexandrova A. N. H and CO Co-Induced Roughening of Cu Surface in CO2 Electroreduction Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146 (23), 16119–16127. 10.1021/jacs.4c03515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friebel D.; Mbuga F.; Rajasekaran S.; Miller D. J.; Ogasawara H.; Alonso-Mori R.; Sokaras D.; Nordlund D.; Weng T.-C.; Nilsson A. Structure, Redox Chemistry, and Interfacial Alloy Formation in Monolayer and Multilayer Cu/Au(111) Model Catalysts for CO2 Electroreduction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118 (15), 7954–7961. 10.1021/jp412000j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trimarco D. B.; Scott S. B.; Thilsted A. H.; Pan J. Y.; Pedersen T.; Hansen O.; Chorkendorff I.; Vesborg P. C. K. Enabling Real-Time Detection of Electrochemical Desorption Phenomena with Sub-Monolayer Sensitivity. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 268, 520–530. 10.1016/j.electacta.2018.02.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trimarco D. B.; Pedersen T.; Hansen O.; Chorkendorff I.; Vesborg P. C. K. Fast and Sensitive Method for Detecting Volatile Species in Liquids. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2015, 86 (7), 075006 10.1063/1.4923453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krempl K.; Hochfilzer D.; Scott S. B.; Kibsgaard J.; Vesborg P. C. K.; Hansen O.; Chorkendorff I. Dynamic Interfacial Reaction Rates from Electrochemistry–Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93 (18), 7022–7028. 10.1021/acs.analchem.1c00110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gründer Y.; Drünkler A.; Golks F.; Wijts G.; Stettner J.; Zegenhagen J.; Magnussen O. M. Structure and Electrocompression of Chloride Adlayers on Cu(111). Surf. Sci. 2011, 605 (17), 1732–1737. 10.1016/j.susc.2011.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat T. P. STM Study of the Influence of Adsorption on Step Dynamics. MRS Online Proc. Libr. 1996, 451 (1), 75–80. 10.1557/PROC-451-75. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasiljevic N.; Dimitrov N.; Sieradzki K. Pattern Organization on Cu(111) in Perchlorate Solutions. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2006, 595 (1), 60–70. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2006.06.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friebel D.; Mangen T.; Obliers B.; Schlaup C.; Broekmann P.; Wandelt K. On the Existence of Ordered Organic Adlayers at the Cu(111)/Electrolyte Interface. Langmuir 2004, 20 (7), 2803–2806. 10.1021/la036130d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y.; Hong J.; Cao D.; You S.; Song Y.; Cheng B.; Wang Z.; Guan D.; Liu X.; Zhao Z.; Li X.-Z.; Xu L.-M.; Guo J.; Chen J.; Wang E.-G.; Jiang Y. Visualizing Eigen/Zundel Cations and Their Interconversion in Monolayer Water on Metal Surfaces. Science 2022, 377 (6603), 315–319. 10.1126/science.abo0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foresti M. L.; Innocenti M.; Forni F.; Guidelli R. Electrosorption Valency and Partial Charge Transfer in Halide and Sulfide Adsorption on Ag(111). Langmuir 1998, 14 (24), 7008–7016. 10.1021/la980692t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broekmann P.; Wilms M.; Kruft M.; Stuhlmann C.; Wandelt K. In-Situ STM Investigation of Specific Anion Adsorption on Cu(111). J. Electroanal. Chem. 1999, 467 (1), 307–324. 10.1016/S0022-0728(99)00048-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.; Dianat A.; Bobeth M.; Cuniberti G. Modeling of the Coadsorption of Chloride and Hydrogen Ions on Copper Electrode Surface. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166 (1), D3042–D3048. 10.1149/2.0061901jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T.; Brisard G. M. Determination of the Kinetic Parameters of Oxygen Reduction on Copper Using a Rotating Ring Single Crystal Disk Assembly (RRDCu(Hkl)E). Electrochim. Acta 2007, 52 (13), 4487–4496. 10.1016/j.electacta.2006.12.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brisard G.; Bertrand N.; Ross P. N.; Marković N. M. Oxygen Reduction and Hydrogen Evolution–Oxidation Reactions on Cu(Hkl) Surfaces. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2000, 480 (1), 219–224. 10.1016/S0022-0728(99)00463-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kok J.; de Ruiter J.; van der Stam W.; Burdyny T. Interrogation of Oxidative Pulsed Methods for the Stabilization of Copper Electrodes for CO2 Electrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146 (28), 19509–19520. 10.1021/jacs.4c06284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.