Abstract

Objective

Scrub typhus, a natural epidemic disease that seriously impacts the health of the population, has imposed a substantial disease burden in Shandong Province. This study aimed to determine the periodicity of the scrub typhus incidence and identify the environmental risk factors affecting scrub typhus to help prevent and control its occurrence in Shandong Province.

Methods

Monthly cases of scrub typhus, mean air temperature, relative humidity, cumulative precipitation, and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) data in Shandong Province from 2006 to 2021 were collected. Wavelet analysis was used to determine the incidence period of scrub typhus and to explore the relationships between environmental factors and the incidence of scrub typhus. Additionally, partial wavelet coherence (PWC) was employed to identify whether meteorological factors affect the association between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence.

Results

Our results showed that scrub typhus incidence has a predominantly one-year period, followed by a less powerful six-month period. The wavelet coherence results revealed positive correlations between scrub typhus incidence and temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, and NDVI. Meteorological factors had a lagged effect of approximately 1–2 months (The phase angles of temperature, precipitation, and relative humidity were 59.15°, 56.57°, and 47.17° respectively) on scrub typhus incidence, whereas NDVI showed a lagged effect of approximately 1–2 weeks (The phase angle of NDVI was 18.11°). On the basis of partial wavelet analysis, we found that temperature and precipitation affected the association between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence.

Conclusion

Meteorological factors and NDVI play important roles in the occurrence of scrub typhus in Shandong Province. Moreover, temperature and precipitation can affect the role of NDVI. This study provides valuable recommendations and resources for the timely detection, mitigation, and management of scrub typhus in Shandong Province.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-025-21987-y.

Keywords: Scrub typhus, Wavelet analysis, Meteorological factors, NDVI, Interactions

Introduction

Scrub typhus is a naturally occurring bacterial infectious disease caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi (OT). It is also a zoonotic disease transmitted through bites from chigger mites. The chigger mite is a group of mites and is the only vector for the intracellular bacterial pathogen of the genus Orientia [1]. It is mainly parasitic on wild vertebrates such as mammals and reptiles. Rodents are one of the primary hosts, and humans are also parasitic as occasional hosts [1]. Infected individuals usually experience a sudden onset of clinical symptoms such as fever, crusts and ulcers, swollen lymph nodes, and a skin rash [2], with skin scabs and fever being the main clinical symptoms that cause hospital admissions in scrub typhus patients. In severe cases, it may lead to meningitis, myocarditis, and even changes in mental symptoms, affecting the normal physiological and psychological functions of the body [3–5].

Scrub typhus has been widely spread throughout the Asia-Pacific region since it first reported in Japan in 1899. However, in recent years, scrub typhus has been detected in Africa, South America, and other regions as well [6, 7], suggesting that scrub typhus has spread to several regions of the world. To date, the annual number of scrub typhus cases have been estimated to exceed 1 million [8]. It is worth noting that more than half of the world’s population lives in the “tsutsugamushi triangle” where scrub typhus is widespread, and about 55% of the population is at risk of contracting scrub typhus [9, 10], particularly in the Asian. One study showed that the serologic prevalence of scrub typhus in Asia ranged from 9.3 to 27.9%, with a median of 22.2% [11]. A study in 2015 showed that the median untreated mortality rate for scrub typhus was about 6%, and although the mortality rate was reduced to 1.4% after treatment [12], still higher than that of other common infectious diseases, such as influenza (< 0.1%) [13], indicating a higher disease burden associated with scrub typhus. Moreover, due to the lack of a specific vaccine, scrub typhus will continue to significantly impact the health of the population in the future and present a public health issue that cannot be ignored.

In China, although the first case of OT was isolated in Guangzhou as early as 1948 [14], for a long time, scrub typhus was found only south of the Yangtze River, and the coastal area was the main incidence area. Since 1986, scrub typhus has been reported in northern regions of the Yangtze River [14], and the number of scrub typhus cases in the northern region has increased more than tenfold compared with that reported in the past 30 years [15], such as in Shandong and Jiangsu Province. Shandong, the province in the northern region where scrub typhus first appeared, has experienced a rapid increase in the number of scrub typhus cases. In 2014, the number of cases was 1,496, an increase of 7 times compared to 213 cases in 2006, the incidence of scrub typhus in Shandong Province fluctuated and declined after 2014. However, a study in Qingdao, Shandong Province, found that about 70% (more than 6 million people) of the population in Qingdao were at risk of scrub typhus disease [16], suggesting that we cannot ignore the potentially serious disease burden of scrub typhus. Another report from counties and cities within Shandong Province indicate that the disability-adjusted life years (DALY) due to scrub typhus and the incidence rate are increasing year by year since 2009 [17]. According to the information system of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the overall incidence rate in Shandong Province has consistently ranked among the top of the “autumn-winter type” cases in regions north of the Yangtze River in China. These all indicate that scrub typhus currently poses a serious disease burden in Shandong Province.

Importantly, scrub typhus infection is associated with the survival and reproduction of rodents and chiggers, which are influenced by the environment, with meteorological factors being particularly crucial. An increasing number of studies have found associations between temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, and scrub typhus [18–20]. In addition to meteorological factors, deforestation has been suggested to create a favorable environment for rodents [21]. The normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) is a comprehensive indicator of vegetation growth and cover. Some studies found that an increase in NDVI led to an increase in the incidence of scrub typhus [22, 23]. Therefore, NDVI may serve as a potential indicator for exploring the risk of scrub typhus. NDVI, as a comprehensive indicator, is affected by various factors. It has been found that the dynamics of NDVI respond to temperature and precipitation [24, 25]. Among them, temperature may affect the duration of vegetation growth and accelerate photosynthesis and the nitrogenization and decomposition of soil humus to form nutrients to influence the effect on NDVI [26–28]; while precipitation may affect the growth and development of vegetation, with suitable precipitation providing a more favorable growth environment for the survival of vegetation [25], thereby influencing the effect of NDVI. Hence we considered whether meteorological factors influence the effect of NDVI on scrub typhus.

However, in the majority of previous studies on scrub typhus, statistical models were directly employed to investigate the meteorological risk factors of scrub typhus. This approach not only overlooked the exploration of the periodicity of scrub typhus incidence and the influence of NDVI but also failed to pay attention to the co-variation and phase relationship between meteorological factors and scrub typhus. On the other hand, scrub typhus data frequently present in the form of time series. In the real world, time series often exhibit non-stationarity, and the likelihood of non-stationarity increases as the duration of the time series expands [29].

Wavelet analysis is developed on the basis of Fourier analysis, replacing the infinite-length trigonometric function in the Fourier transform with a wavelet function. This substitution addresses the limitation of Fourier analysis in accurately capturing temporal information. Wavelet analysis does not depend on the linear or nonlinear characteristics of the time series and can decompose them on a local time scale, overcoming the issue of non-stationarity. It has been demonstrated that wavelet analysis can be used to analyze the main periods, trends, risk factors, and influencing factors of various diseases efficiently [30–34]. Therefore, we included NDVI in our analysis, and wavelet analysis was necessary to explore the periodicity of scrub typhus incidence and the strength of the association between environmental factors and scrub typhus. This exploration is conducive to understanding the current incidence of scrub typhus and can help establish a more effective local monitoring, prevention, and control system.

In this study, we aim to explore the effects of temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, and NDVI on the incidence of scrub typhus in Shandong Province from 2006 to 2021 through a series of methods using wavelet analysis. Finally, we also find out whether the effect of NDVI is influenced by meteorological factors.

Materials and methods

Study area

Shandong Province is located in East China, between the north latitude of 34°22.9′N to 38°24.1′N and the east longitude of 114°47.5′E to 122°42.3′E. It is the earliest region in China where scrub typhus has appeared north of the Yangtze River, covering a land area of approximately 155,800 km2 (Fig. 1). Located on the coastline of East China and the lower region of the Yellow River, this province experiences a warm-temperate monsoon climate characterized by concentrated year-round precipitation, with the highest amount of rainfall typically observed during the summer months. By the end of 2021, the permanent population of Shandong Province totaled 101.7 million (http://tjj.shandong.gov.cn/).

Fig. 1.

Location of the study area in Shandong Province in the geographical region of China. The base maps used are from the China Resource and Environmental Science Data Platform (https://www.resdc.cn/),

Scrub typhus incidence

Monthly scrub typhus case data were obtained from the China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention (CISDCP) from 1 January 2006 to 31 December 2021. The system is the most official and reliable for notifiable infectious diseases in China. Every infectious disease case in every region of China is reported to the system through the web-based direct reporting system, which collates and stores information on relevant infectious diseases. The scrub typhus data we used collected detailed personal information about each scrub typhus patient, including sex, age, occupation, current address, type of case, onset date, and diagnosis date. The onset date of scrub typhus was used in this study, which is more applicable for epidemiological research.

All cases of scrub typhus in this study were diagnosed on the basis of clinical or laboratory examinations following the uniform criteria issued by the Chinese Ministry of Health (https://www.chinacdc.cn/). Among them, the clinical diagnosis must include the following criteria: (1) a history of field activity in a scrub typhus-endemic area 3 weeks before the onset of disease; (2) nonspecific clinical symptoms such as fever, enlarged lymph nodes, and rash; and (3) specific crusting or ulceration. A laboratory diagnosis must meet all of the above clinical diagnostic criteria and include one of the following laboratory confirmatory criteria: (1) Positive Exophthalmos test: single serum OXK potency ≥ 1:160; (2) Positive Indirect Immunofluorescence test: double serum IgG antibody titer 4-fold or more elevated; (3) Positive PCR nucleic acid test; (4) Isolation of the OT pathogen from clinical specimens. This study excluded suspected cases and included all clinically and laboratory-confirmed cases.

In addition, the resident population data of Shandong Province from 2006 to 2021 were used in this study to calculate the monthly scrub typhus incidence from the Statistical Yearbook of Shandong Province (http://tjj.shandong.gov.cn/).

Environmental variables

The environmental data from 2006 to 2021 included meteorological data and NDVI data. Meteorological data were obtained from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/), including monthly mean temperature (°C), monthly mean relative humidity (%), and monthly cumulative precipitation (mm). NDVI data were obtained from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) dataset (https://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/). For the NDVI data, we firstly extracted the NDVI raster data of Shandong Province from the whole China, and then used the Maximum Value Composition (MVC) to generate the layer to get the NDVI data of Shandong Province. The data resolution is 1 km X 1 km, and the coordinate system used is WGS1984.

Data pre-processing

Before conducting the wavelet analysis, the environmental data and the scrub typhus incidence were square root transformed and log-transformed, respectively, to eliminate the effects of outliers. Subsequently, all the data were standardized to eliminate the potential impacts of scale and extremes caused resulting from singular data.

Wavelet analysis

Wavelet analysis was initially applied in climate science [35] and has been increasingly utilized in the field of infectious diseases, including dengue [36], influenza [37], and hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome [19]. The fundamental concept of wavelet analysis is to examine the time-frequency variability of a time series by extracting the frequency domain information of the signal through local time scale decomposition of the original sequence [38]. In this study, we used the Morlet mother wavelet to conduct a continuous wavelet transform (CWT) on all the aforementioned time series:

|

where  denotes each time series,

denotes each time series,  denotes the Morlet mother wavelet,

denotes the Morlet mother wavelet,  denotes the scale,

denotes the scale,  denotes the translation, and

denotes the translation, and  denotes the complex conjugate. The wavelet power spectrum was calculated via Equation (1) to analyze the periodicity of each time series [39].

denotes the complex conjugate. The wavelet power spectrum was calculated via Equation (1) to analyze the periodicity of each time series [39].

In addition, to explore the effects of each meteorological factor and NDVI on scrub typhus incidence, we used cross wavelet transform (XWT) analysis:

|

where  denotes the cross-wavelet power. Equation (2) reveals the common high-power regions between each environmental variable and scrub typhus incidence [40], reflecting the strength of their common period in determining the correlation between them.

denotes the cross-wavelet power. Equation (2) reveals the common high-power regions between each environmental variable and scrub typhus incidence [40], reflecting the strength of their common period in determining the correlation between them.

We also used wavelet coherence analysis (WTC) to discover common regions of variation between each environmental variable and scrub typhus incidence. This analysis revealed their local phase locking behavior, further helping to identify a significant association between these factors and scrub typhus incidence [40]. Wavelet coherence analysis is defined by the following equation:

|

where  is the smoothing operator which defines the measured coherence covariance scale by smoothing the time and frequency scales.

is the smoothing operator which defines the measured coherence covariance scale by smoothing the time and frequency scales.

To further determine the lagged effects of each environmental variable on scrub typhus, we calculated the phase angle between the two time-series and produced plots for phase comparisons at specific period. Significance tests were performed via a red noise test that included first-order autoregression (AR1) generated via Monte Carlo techniques to determine the 95% confidence level [41].

In the cross wavelet and wavelet coherence spectrum, the arrows indicate the relative phases [36]. The left and right directions indicate the correlation between the two time-series. If the arrow points to the right (left), the two variables are in phase (anti-phase). The up and down directions of the arrows indicate the order of appearance of the two time-series. If the arrow is up (down), the former is ahead (behind) the latter.

Finally, to specify the independent effect of NDVI on scrub typhus incidence, we used partial wavelet coherence (PWC). It is designed to explore the coherence between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence after controlling for the effects of each meteorological factor, respectively [42]. Similar to partial correlation, PWC is defined by the following equation:

|

where  denotes the controlled meteorological factor,

denotes the controlled meteorological factor,  denotes NDVI,

denotes NDVI,  denotes the incidence of scrub typhus and

denotes the incidence of scrub typhus and  represents the square of the partial wavelet squared coherence, and

represents the square of the partial wavelet squared coherence, and  denotes the wavelet coherence between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence. Compared with the original wavelet coherence spectrum, if the partial wavelet power spectrum does not exhibit a significant region at the same period, it indicates that scrub typhus incidence is more influenced by x1. However, if a similar significant region still emerges at the same period, it indicates that scrub typhus incidence is influenced by both x1 and x2, which are independent of each other.

denotes the wavelet coherence between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence. Compared with the original wavelet coherence spectrum, if the partial wavelet power spectrum does not exhibit a significant region at the same period, it indicates that scrub typhus incidence is more influenced by x1. However, if a similar significant region still emerges at the same period, it indicates that scrub typhus incidence is influenced by both x1 and x2, which are independent of each other.

All wavelet analysis was performed using the “WaveletComp” and “biwavelet” packages in R sort 4.3.2.

Results

Descriptive analysis of the epidemiology of scrub typhus and environmental factors

From 1 January 2006 to 31 December 2021, a total of 10,225 cases of scrub typhus were reported in Shandong Province. During the study period, the highest number of cases was recorded in 2014 with 1496 cases and an annual incidence rate of 1.53/100,000. The highest monthly incidence of scrub typhus was 1.17/100,000 in October of that year (Fig. s1). During these sixteen years, the patients were predominantly female, with a male to female ratio of 1:1.27. Additionally, the onset age of scrub typhus was wide, with cases occurring between the ages of 5 months and 95 years, particularly affecting individuals aged 14–59 years (Table s1). The occupational records of patients revealed that the vast majority (88.30%) of scrub typhus cases occurred among farmers, followed by workers, retirees, and students.

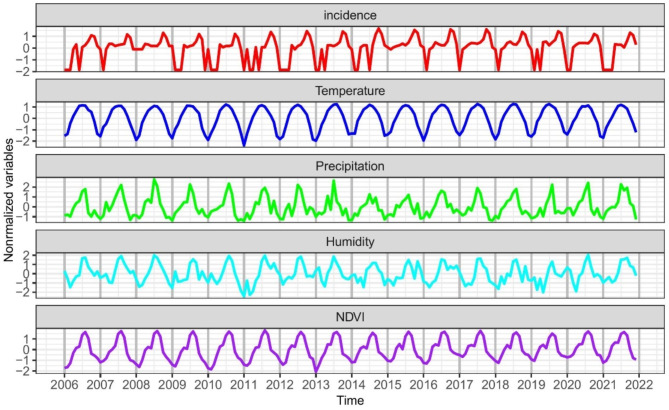

The incidence of scrub typhus in Shandong Province is seasonal, with the peak of the epidemic typically occurring from September to November (Fig. 2). The average monthly case is 53.26 cases. The median mean temperature, total precipitation, mean relative humidity, and NDVI in Shandong Province were 13.97℃, 57.74 mm, 60.76%, and 0.43, respectively (Table 1). All four of these environmental factors were also seasonal. The mean temperature and NDVI did not vary significantly among years, while the total precipitation and relative humidity showed certain difference among years (In particular, the difference in precipitation is about 37 mm between the highest year 2021, and the lowest year 2019, while the difference in relative humidity is about 7% between the highest year 2007, and the lowest year 2019).

Fig. 2.

Time series of scrub typhus incidence, mean temperature, cumulative precipitation, mean relative humidity and NDVI in Shandong Province from 2006 to 2021

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of scrub typhus cases and environmental variables in Shandong Province from 2006 to 2021

| Mean | S.D. | Min | P 25 | Median | P 75 | Max | CV (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cases | 53.26 | 153.74 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 11.25 | 1147.00 | 288.66 |

| Temperature (℃) | 13.97 | 9.73 | -3.49 | 5.11 | 14.85 | 22.85 | 27.98 | 69.65 |

| Precipitation(mm) | 57.74 | 62.94 | 1.98 | 14.04 | 32.53 | 57.74 | 285.80 | 109.01 |

| Humidity (%) | 60.76 | 10.57 | 37.30 | 52.90 | 58.66 | 68.19 | 83.57 | 17.40 |

| NDVI | 0.43 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.31 | 0.41 | 0.53 | 0.72 | 34.88 |

S.D.: Standard deviation; CV: coefficient of variation

Periodicity of environmental variables and scrub typhus incidence

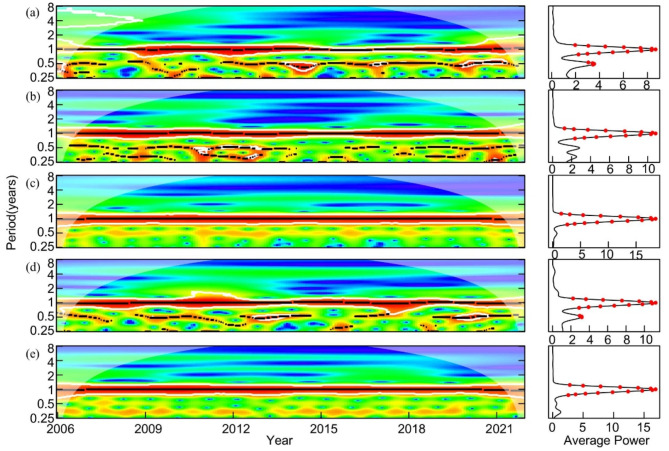

The wavelet power spectrum of scrub typhus incidence and each environmental variable in Figure 3 showed that there were two periods of scrub typhus incidence. Scrub typhus incidence showed a 1-year period during the study period and statistically significant, with intermittent half-year periods occurring in some years, such as 2006–2009 and 2012–2021. However, the average power was poor, indicating that the main period was one year (Fig. 3a). Similarly, temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, and NDVI were significant on a one-year scale, indicating that they also had a 1-year primary period, and all were statistically significant (Fig. 3b, c, d, e).

Fig. 3.

Wavelet power spectrum (left) and average power plots (right) of scrub typhus incidence (a), mean temperature (b), cumulative precipitation (c), mean relative humidity (d), and NDVI (e) in Shandong Province from 2006 to 2021. The outline outlined by the bold white lines is the test at the 5% significance level, the solid black line represents the corresponding period, the red dots indicate significant periods at the 5% level (P < 0.05)

Correlation between environmental variables and scrub typhus incidence

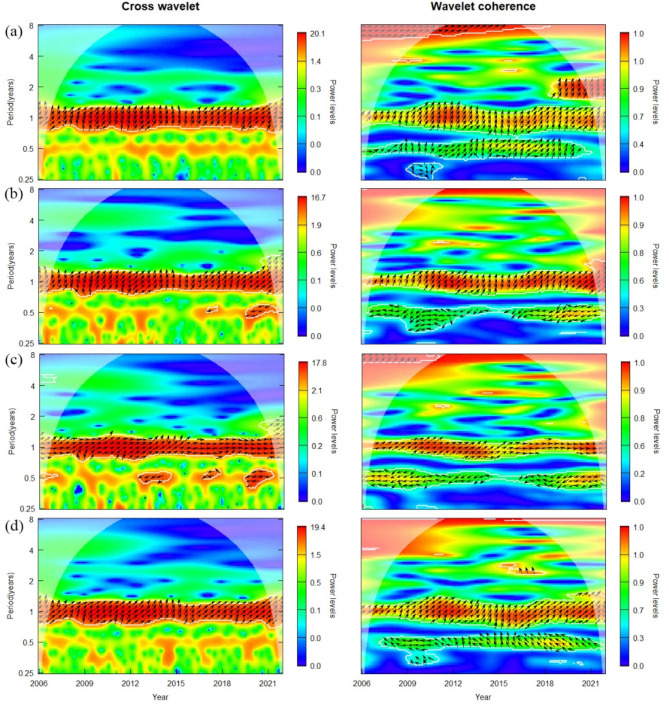

Figure 4 displays the cross-wavelet power and wavelet coherence spectrum of temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, and NDVI in relation to scrub typhus incidence, respectively. Since the wavelet power spectrum shows that the period of each environmental variable and the scrub typhus incidence is dominated by one year (Fig. 3), it indicates that the period of the closest relationship between the environmental variables and the scrub typhus incidence should be 1 year. Therefore, a 1-year period was chosen in this study to explore the correlation. In both figures, the arrows mostly point to the right and up, indicating that temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, and NDVI were positively correlated with scrub typhus incidence at a 1-year period, and all these factors contribute to a lagged effect on scrub typhus incidence. Moreover, from the power level in the cross-wavelet analysis legend, it can be seen that the correlation between temperature and the incidence of scrub typhus is the strongest, followed by NDVI.

Fig. 4.

Cross wavelet power spectrum (left) and wavelet coherence spectrum (right) of mean temperature, cumulative precipitation, mean relative humidity, and NDVI with the scrub typhus incidence rate in Shandong Province from 2006 to 2021. (a) Mean temperature-incidence; (b) cumulative precipitation-incidence; (c) mean relative humidity-incidence; (d) NDVI-incidence. The outline outlined by the bold white lines is the test at the 5% significance level

However, it was found that the time of the lagged effect of different variables on scrub typhus varied, as obtained by calculating the phase angle between each environmental variable and the scrub typhus incidence (Fig. 5). The increase in the incidence of scrub typhus was associated with the rise in temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, and NDVI by 1.98 (phase angle = 59.15°), 1.89 (phase angle = 56.57°), 1.58 (phase angle = 47.17°), and 0.6 (phase angle = 18.11°) months later, indicating that temperature, precipitation, and relative humidity had a lagged effect on the incidence of scrub typhus for approximately 2 months, while NDVI had a lagged effect of 2–3 weeks. Additionally, the reconstructed time series of environmental variables and the scrub typhus incidence confirmed these results (Figs. s2-s5).

Fig. 5.

Phase difference between mean temperature, cumulative precipitation, mean relative humidity, NDVI and scrub typhus incidence at 1-year period in Shandong from 2006 to 2021. (a) Mean temperature (blue line)-incidence (red line); (b) cumulative precipitation (blue line)-incidence (red line); (c) mean relative humidity (blue line)-incidence (red line); (d) NDVI (blue line)-incidence (red line)

The effect of climatic variables on the relationship between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence

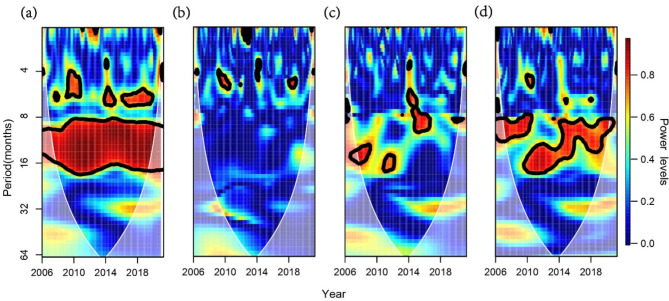

Figure 6 illustrates the cross-wavelet power spectrum of NDVI in relation to scrub typhus incidence when considering both the controlled and uncontrolled for effects of temperature, precipitation, and relative humidity.

Fig. 6.

Partial wavelet coherence spectrum of NDVI and scrub typhus incidence in Shandong Province from 2006 to 2021, after controlling the effect of meteorological factors. (a) No meteorological factors were controlled; (b) Controlling the effect of mean temperature; (c) Controlling the effect of cumulative precipitation; (d) Controlling the effect of mean relative humidity

A comparison of Figure 6a reveals that the region of significant coherence between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence occurs in the frequency band of 8–16 period when meteorological factors are not controlled. Nevertheless, the region of significant coherence between the two at period 8–16 disappears completely after controlling for temperature, suggesting that there is a significant effect of temperature on the correlation between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence. Figure 6c shows that after controlling for the effect of precipitation, most of the correlations between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence disappeared. However, some years still exhibit significant coherence, suggesting a residual confounding effect of precipitation, albeit to a lesser extent than temperature. In contrast, the significance of the association between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence in the 8–16 period remained mostly unchanged after controlling for the effect of relative humidity in Figure 6d. This suggests that relative humidity does not significantly impact on the association between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence.

Discussion

Scrub typhus, a significant public health concern in China, has become a prominent topic in infectious disease research. Most previous studies have focused on regions south of the Yangtze River, where the incidence is relatively high [43–45].In contrast, our study in Shandong Province, which has the earliest and highest incidence north of the Yangtze River, explored the impact of environmental factors such as temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, and NDVI on the scrub typhus incidence. These findings can help us develop a more nuanced understanding of the environmental factors that drive scrub typhus. This understanding will aid in the development of more sophisticated predictive models, which can contribute to early warning systems for scrub typhus.

In this study, we first conducted a descriptive analysis of scrub typhus in Shandong Province from 2006 to 2021. We found that the incidence of scrub typhus increased gradually and steadily from 2006 to 2013, but the incidence increased sharply from 2014 to 2016, which may be related to the maturity of the surveillance and examination system in medical institutions and the shortening of the time interval from onset to diagnosis due to the clarification of diagnostic criteria [46]. The decreasing trend of scrub typhus after 2016 may be closely related to the continuous improvement of medical service, the continuous enhancement of primary health care service, and the continuous renewal of public awareness of prevention in China in recent decades [47, 48]. For the characteristics of the affected population, we found that the number of female cases exceeded that of male cases, and the majority of cases were farmers. Additionally, the age of onset was widespread, with the highest incidence occurring between 14 and 59 years. This result is similar to other studies [44, 49]. This similarity may be attributed to the fact that most males are employed outside the home, whereas [44] females predominantly work in agriculture at home, thereby increasing their likelihood of exposure to scrub typhus. Meanwhile, after middle age, the body’s immunity decreases, leading to an increased likelihood of illness [50].

This study found that the primary inter-annual variation in scrub typhus incidence in Shandong Province occurred on a yearly basis, which aligns with findings from a nationwide study [51]. In contrast, a study in Guangzhou [52] found two trends in scrub typhus incidence in Guangzhou Province: a short-term trend lasting 8–12 months period and a long-term trend lasting 26–32 months period. However, both trends were still predominant within a 1-year period, suggesting that the trend of scrub typhus incidence may be influenced by climate change in different regions and the life cycle of different types of scrub typhus. Regardless, the predominant 1-year period of scrub typhus implies that it is a constant threat that needs to be addressed annually. However, due to the current lack of information on the scrub typhus incidence period in other regions, more evidence is needed to further define its incidence period.

The cross wavelet analysis and wavelet coherence analysis revealed that scrub typhus in Shandong Province is strongly associated with temperature, precipitation, and relative humidity. All of these meteorological factors had a positive effect on the incidence of scrub typhus, similar to the results of other studies [22, 53, 54]. A study of Guangzhou, China [22] used random forests to determine that high temperature, high humidity, and heavy rainfall provide favorable conditions for the transmission of scrub typhus, thereby increasing the incidence of scrub typhus. Another study on a nationwide scale in China [54] found that for every 1 °C increase in temperature, 1% increase in humidity, and 1 mm increase in precipitation, there was a 15.4%, 12.6%, and 0.7% rise in scrub typhus incidence, respectively. Meteorological factors affect the growth and reproduction of chigger mites, and the activity of the host animal. However, some studies have shown that northern scrub typhus and southern scrub typhus are caused by different types of chigger mites, leading to variations in the impact of meteorological factors. Northern scrub typhus is an autumn-winter type of case, with L. scutellare as the main vector, preferring a cold and dry environment, while southern scrub typhus is a summer type of case, with L. deliense as the main vector, preferring a hot and humid environment [55, 56]. While the duration of this study spanned 16 years, the scrub typhus genotypes and rat species in Shandong Province may vary over an extended period [57], resulting in fluctuations in the impact of meteorological factors. On the other hand, various socio-economic conditions and natural environmental factors, such as altitude in different regions, can influence behavioral habits and awareness of protection, resulting in variations in the study outcomes. Therefore, the key to controlling scrub typhus lies in adapting to local conditions and implementing tailored measures for different populations.

Moreover, all three meteorological factors had a lag time of about 1–2 months on the incidence of scrub typhus, which is consistent with the results of other studies [58, 59]. Although some research [60] have concluded that meteorological factors have longer effects on scrub typhus, it suggests that we need to pay more attention to meteorological factors and provide warnings for scrub typhus at least 2 months in advance.

NDVI, as a comprehensive indicator of vegetation cover, can be used to understand the impact on scrub typhus by demonstrating the status and extent of vegetation growth. This study revealed a positive correlation between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence, with a lag effect of 2–3 weeks. This finding is in agreement with studies conducted in other regions and countries [61–63]. An Indian research [63] showed a 4-week lag effect between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence, indicating a notable rise in scrub typhus cases when NDVI remained consistently high for 4 weeks. Vegetation is essential for the survival and reproduction of many infectious disease vectors, so the increase of vegetation leads to an expansion in the abundance of mites and rodents, consequently raising the risk of scrub typhus incidence. Although current research is inconclusive about the lag time of NDVI, our study is based on a comprehensive wavelet analysis conducted over an extended time series (2006–2021) to calculate the phase difference between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence, providing an ideal method to determine the lag time. The 2–3 week lag effect of NDVI may be related to the fact that L. deliense, the main vector of scrub typhus, takes 2 weeks to develop into infectious chigger mite larvae [64]. However, there is currently a lack of research on this lag effect. In the future, more biological mechanisms and delayed diagnosis of scrub typhus can be considered to explore this effect. Nevertheless, a Korean study [65] found that deforestation increased the incidence risk of scrub typhus, implying that a reduction in forest cover led to an increase in scrub typhus incidence, the reason may be the inconsistency between the focus of our study and theirs, with they discussing the loss of biodiversity in the environment caused by deforestation, which affects the population of host rodents and vector mites for scrub typhus, whereas our study discussing the destruction of habitats for rodents and mites due to the decrease in NDVI, leading to their inability to grow and reproduce, and ultimately reducing the incidence of scrub typhus. In the face of different NDVI effects, in the future, we need a more comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach to explore and explain the impact of NDVI on the incidence of scrub typhus.

In this study, we used PWC to explore the effect of meteorological factors on the association between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence. It was found that among these three variables, temperature and precipitation could affect the relationship with a lag of 2–3 weeks. This is similar to the findings of other studies. A study in Inner Mongolia, China [66] similarly found that temperature and precipitation affect NDVI with certain periodicity and lag effects. Another study on seven regions [67] used residual analysis and random forests to quantitatively explain that the contribution of meteorological factors to NDVI, although not as significant as anthropogenic activities, led to some changes in NDVI. This may be due to the fact that temperature and precipitation can affect the growth of vegetation, such as increasing the duration of leaf opening in plants [68]. On the other hand, the type and distribution of vegetation can be influenced by meteorological factors, which in turn leads to a change in the original association of NDVI with scrub typhus. However, there is a lack of studies on the lag time of NDVI in response to temperature and precipitation, which requires further investigation for more conclusive results in the future. Our results also show that relative humidity does not have a significant effect on the association of NDVI with scrub typhus. The impact of relative humidity has been seldom explored in other studies, with most focusing on temperature and precipitation as the primary factors affecting NDVI.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the number of cases used in this study were based on reported cases in hospitals, which may overlook asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients. Secondly, due to the lack of rodent data, we did not consider the potential impact of rodents as intermediate hosts. Moreover, the NDVI data used in our study is the monthly average of Shandong Province, which may cause ecological fallacy, and the impact of NDVI should be considered at a finer spatial-temporal scale in the future. Thirdly, due to the long duration of our study, the gradual maturation of our healthcare and diagnostic techniques over the study period, and differences in diagnostic techniques may have led to different criteria for scrub typhus cases in each year, resulting in possible classification bias. In addition, our study period included the time when the COVID-19 outbreak occurred, and we neglected the effect of COVID-19 on scrub typhus patients. Lastly, the correlations derived from wavelet analyses do not represent causality, thus further exploration of causal relationships between environmental factors and scrub typhus incidence at different scales needs to be warranted in the future.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that meteorological factors in the preceding 1–2 months and NDVI in the preceding 2–3 weeks may increase the risk of scrub typhus. Additionally, temperature and precipitation can influence the relationship between NDVI and scrub typhus incidence. These results provide a theoretical framework and reference value for the prevention and control of scrub typhus in Shandong Province, and can help public health workers to effectively make early warnings and preparations for scrub typhus.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention for providing data for our research.

Author contributions

ZSN: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing and Editing. SFL: Formal analysis, Review. RX: Formal analysis, Review. KML: Formal analysis, Review. SHS: Formal analysis, Review. HZ: Formal analysis, Review. CLC: Formal analysis, Review. LL: Conceptualization, Validation, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing-review, and Editing. XJL: Conceptualization, Validation, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing-review, and Editing.

Funding

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China [grant numbers: 2023YFC2604401]; and National Natural Science Foundation of China (General Program) [grant numbers: 81673238].

Data availability

Scrub typhus data supporting the results of this study were available from the China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention (CISDCP), but the availability of these data was limited, which was used under the license of the project we are conducting. If appropriate permission for the data is required, please apply through the project to obtain the license.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Liang Lu and Xiujun Li contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Liang Lu, Email: luliang@icdc.cn.

Xiujun Li, Email: xjli@sdu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.CHAISIRI K, LINSUWANON P, MAKEPEACE BL. The chigger microbiome: big questions in a tiny world [J]. Trends Parasitol. 2023;39(8):696–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ZHANG M, ZHAO Z T, WANG X J, LI Z, DING DINGL. Scrub typhus: surveillance, clinical profile and diagnostic issues in Shandong, China [J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87(6):1099–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CHO NH, KIM H R, LEE J H, KIM S Y, KIM J. The Orientia tsutsugamushi genome reveals massive proliferation of conjugative type IV secretion system and host-cell interaction genes [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(19):7981–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DITTRICH S, LEE S J RATTANAVONGS, PANYANIVONG P, CRAIG S B, TULSIANI S M, et al. Orientia, rickettsia, and leptospira pathogens as causes of CNS infections in Laos: a prospective study [J]. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(2):e104–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.OLSEN SJ, CAMPBELL A P, SUPAWAT K, LIAMSUWAN S, CHOTPITAYASUNONDH T, LAPTIKULTHUM S, et al. Infectious causes of encephalitis and meningoencephalitis in Thailand, 2003–2005 [J]. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(2):280–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.GHORBANI R P, GHORBANI A J, JAIN M K, WALKER D H. A case of scrub typhus probably acquired in Africa [J]. Clin Infect Diseases: Official Publication Infect Dis Soc Am. 1997;25(6):1473–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WEITZEL T, DITTRICH S, LóPEZ J, PHUKLIA W, MARTINEZ-VALDEBENITO C, VELáSQUEZ K, et al. Endemic Scrub Typhus in South America [J]. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):954–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WONGSANTICHON J, JAIYEN Y, DITTRICH S. Orientia tsutsugamushi [J]. Trends Microbiol. 2020;28(9):780–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LI T, YANG Z, DONG Z. Meteorological factors and risk of scrub typhus in Guangzhou, southern China, 2006–2012 [J]. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.PRAKASH J A. J. Scrub typhus: risks, diagnostic issues, and management challenges [J]. Research and reports in tropical medicine, 2017, 8: 73–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.BONELL A, LUBELL Y, NEWTON P N, CRUMP J A. PARIS D H. estimating the burden of scrub typhus: a systematic review [J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(9):e0005838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ZAMAN K. Scrub typhus, a salient threat: needs attention [J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17(6):e0011427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.IULIANO A D, ROGUSKI K M, CHANG H H, MUSCATELLO D J, PALEKAR R, TEMPIA S, et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study [J]. Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1285–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.XIANGRUI C, JINJU W, YONGGUO Z, YANAN W, CHUNMU Y, ZHAOPING X, et al. Recent studies on scrub typhus and Rickettsia tsutsugamushi in Shandong Province–China [J]. Eur J Epidemiol. 1991;7(3):304–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.YAO H, WANG Y, MI X, SUN Y, LIU K, LI X, et al. The scrub typhus in mainland China: spatiotemporal expansion and risk prediction underpinned by complex factors [J]. Volume 8. Emerging microbes & infections; 2019. pp. 909–19. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.XIN H, FU P, SUN J, HU W, CLEMENTS A C A LAIS, et al. Risk mapping of scrub typhus infections in Qingdao city, China [J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(12):e0008757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.YANG L P, LIANG S Y, WANG X J, LI X J, WU Y L MAW. Burden of disease measured by disability-adjusted life years and a disease forecasting time series model of scrub typhus in Laiwu, China [J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(1):e3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.BHOPDHORNANGKUL B, MEEYAI A C, WONGWIT W, LIMPANONT Y, IAMSIRITHAWORN S, LAOSIRITAWORN Y, et al. Non-linear effect of different humidity types on scrub typhus occurrence in endemic provinces. Thail [J] Heliyon. 2021;7(2):e06095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LIU L, XIAO Y, WEI X, LI X, DUAN C, JIA X et al. Spatiotemporal epidemiology and risk factors of scrub typhus in Hainan Province, China, 2011–2020 [J]. One health (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2023, 17: 100645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.SETO J, SUZUKI Y, NAKAO R, OTANI K, YAHAGI K, MIZUTA K. Meteorological factors affecting scrub typhus occurrence: a retrospective study of Yamagata Prefecture, Japan, 1984–2014 [J]. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145(3):462–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.WALKER DH. Scrub Typhus - Scientific neglect, ever-widening impact [J]. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):913–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.HUANG X, XIE B, LONG J, CHEN H, ZHANG H, FAN L, et al. Prediction of risk factors for scrub typhus from 2006 to 2019 based on random forest model in Guangzhou, China [J]. Trop Med Int Health. 2023;28(7):551–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WEI X, HE J, SOARES MAGALHAES R J YINW, WANG Y, XU Y, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics and environmental determinants of scrub typhus in Anhui Province, China, 2010–2020 [J]. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.JIN K, WANG F, ZONG Q, QIN P, LIU C, WANG S. Spatiotemporal differences in climate change impacts on vegetation cover in China from 1982 to 2015 [J]. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022;29(7):10263–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.SONG W, FENG Y, WANG Z. Ecological restoration programs dominate vegetation greening in China [J]. Sci Total Environ. 2022;848:157729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LUCHT W, PRENTICE I C, MYNENI R B, SITCH S, FRIEDLINGSTEIN P, CRAMER W, et al. Climatic control of the high-latitude vegetation greening trend and Pinatubo effect [J]. Science. 2002;296(5573):1687–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CONANT R T, STEINWEG J M, HADDIX M L, PAUL E A, PLANTE A F, SIX J. Experimental warming shows that decomposition temperature sensitivity increases with soil organic matter recalcitrance [J]. Ecology. 2008;89(9):2384–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.PIAO S, CIAIS P, FRIEDLINGSTEIN P, PEYLIN P, REICHSTEIN M. Net carbon dioxide losses of northern ecosystems in response to autumn warming [J]. Nature. 2008;451(7174):49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.CAZELLES B, CAZELLES K. Wavelet analysis in ecology and epidemiology: impact of statistical tests [J]. J R Soc Interface. 2014;11(91):20130585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.CAZELLES B, CAZELLES K, TIAN H, CHAVEZ M. Disentangling local and global climate drivers in the population dynamics of mosquito-borne infections [J]. Sci Adv. 2023;9(39):eadf7202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DJENNAD A, LO IACONO G, SARRAN C, LANE C, ELSON R, HöSER C, et al. Seasonality and the effects of weather on Campylobacter infections [J]. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.PRABODANIE R A R, SCHREIDER S, CAZELLES B. Coherence of dengue incidence and climate in the wet and dry zones of Sri Lanka [J]. Sci Total Environ. 2020;724:138269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.EHELEPOLA ND. The interrelationship between dengue incidence and diurnal ranges of temperature and humidity in a Sri Lankan city and its potential applications [J]. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:29359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.IGUCHI JA, SEPOSO X T, HONDA Y. Meteorological factors affecting dengue incidence in Davao, Philippines [J]. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.JEVREJEVA S, MOORE J C GRINSTEDA. Influence of the Arctic Oscillation and El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) on ice conditions in the Baltic Sea: the wavelet approach [J]. J Geophys Res. 2003;108:D21. [Google Scholar]

- 36.XIAO J, LIU T, LIN H, ZHU G, ZENG W, LI X, et al. Weather variables and the El Niño Southern Oscillation may drive the epidemics of dengue in Guangdong Province, China [J]. Sci Total Environ. 2018;624:926–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.LIANG Y, FANG L, PAN H, ZHANG K, KAN H. PM2.5 in Beijing - temporal pattern and its association with influenza [J]. Environ Health. 2014;13:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.TORRENCE C, COMPO GP. A practical guide to Wavelet analysis [J]. Bull Am Meteorol Soc, 1998, 79(1).

- 39.PAIREAU J, CHEN A, BROUTIN H, GRENFELL B, BASTA N E. Seasonal dynamics of bacterial meningitis: a time-series analysis [J]. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(6):e370–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.GRINSTED A, MOORE J C JEVREJEVAS. Application of the cross wavelet transform and wavelet coherence to geophysical time series [J]. Nonlinear Proc Geoph. 2004;11(5/6):561–6. [Google Scholar]

- 41.CASAGRANDE E, MUELLER B, MIRALLES D G, ENTEKHABI D. Wavelet correlations to reveal multiscale coupling in geophysical systems [J]. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2015;120(15):7555–72. [Google Scholar]

- 42.MIHANOVIC H, ORLIC M. Diurnal thermocline oscillations driven by tidal flow around an island in the Middle Adriatic [J]. J Mar Syst. 2009;78:S157–68. [Google Scholar]

- 43.LI X, WEI X, SOARES MAGALHAES R J YINW, XU Y, WEN L, et al. Using ecological niche modeling to predict the potential distribution of scrub typhus in Fujian Province, China [J]. Parasit Vectors. 2023;16(1):44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.PAN K, HUANG R, XU L, LIN F. Exploring the effects and interactions of meteorological factors on the incidence of scrub typhus in Ganzhou City, 2008–2021 [J]. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.ZHENG C, JIANG D, DING F, FU J. Clin Infect diseases: official publication Infect Dis Soc Am. 2019;69(7):1205–11. HAO M. Spatiotemporal Patterns and Risk Factors for Scrub Typhus From 2007 to 2017 in Southern China [J]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.XIN H L, YU J X, HU M G, JIANG F C, LI X J, WANG L P, et al. Evaluation of scrub typhus diagnosis in China: analysis of nationwide surveillance data from 2006 to 2016 [J]. Infect Dis Poverty. 2019;8(1):59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.YANG G, WANG Y, ZENG Y, GAO G F, LIANG X, ZHOU M, et al. Rapid health transition in China, 1990–2010: findings from the global burden of Disease Study 2010 [J]. Lancet. 2013;381(9882):1987–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.QIN J, LIN C, ZHANG Y. The status and challenges of primary health care in China [J]. Chin Gen Pract J. 2024;1(3):182–7. [Google Scholar]

- 49.WEI Y, GUAN X, ZHOU S, ZHANG A, LU Q, ZHOU Z, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of patients with Scrub Typhus - Guangzhou City, Guangdong Province, China, 2012–2018 [J]. China CDC Wkly. 2021;3(51):1079–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.LIAO H, HU J, SHAN X, YANG F, WEI W, WANG S, et al. The temporal lagged relationship between Meteorological factors and Scrub Typhus with the distributed lag non-linear Model in Rural Southwest China [J]. Front Public Health. 2022;10:926641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.HE J, WANG Y, LIU P, YIN W, WEI X. SUN H, Co-effects of global climatic dynamics and local climatic factors on scrub typhus in mainland China based on a nine-year time-frequency analysis [J]. One health (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2022, 15: 100446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.WEI Y, HUANG Y, LI X, MA Y, TAO X, WU X, et al. Climate variability, animal reservoir and transmission of scrub typhus in Southern China [J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(3):e0005447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.HAN L, SUN Z, LI Z, ZHANG Y, TONG S. Impacts of meteorological factors on the risk of scrub typhus in China, from 2006 to 2020: a multicenter retrospective study [J]. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1118001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.YANG L P, LIU J, WANG X J, MA W, JIA C X. JIANG B F. effects of meteorological factors on scrub typhus in a temperate region of China [J]. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142(10):2217–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DING F, JIANG W L, GUO X G, FAN R, ZHAO C F, ZHANG Z W, et al. Infestation and related Ecology of Chigger mites on the Asian House rat (Rattus tanezumi) in Yunnan Province, Southwest China [J]. Korean J Parasitol. 2021;59(4):377–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.LV Y, GUO X, SONG JIND, PENG W, LIN P. Infestation and seasonal fluctuation of chigger mites on the southeast Asian house rat (Rattus brunneusculus) in southern Yunnan Province, China [J]. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2021;14:141–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.WANG Y C, LI J H, QIN Y, QIN S Y, CHEN C, YANG X B, et al. The prevalence of rodents Orientia tsutsugamushi in China during two decades: a systematic review and Meta-analysis [J]. Vector borne and zoonotic diseases (Larchmont. NY). 2023;23(12):619–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.DING F, WANG Q, MAUDE R J HAOM, JOHN DAY N P LAIS, et al. Climate drives the spatiotemporal dynamics of scrub typhus in China [J]. Glob Change Biol. 2022;28(22):6618–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.LI W, NIU Y L, REN H Y, SUN W W, MA W, LIU X B, et al. Climate-driven scrub typhus incidence dynamics in South China: a time-series study [J]. Front Env Sci-Switz; 2022. p. 10.

- 60.LUO Y, ZHANG L, LV H, ZHU C, AI L, QI Y, et al. How meteorological factors impacting on scrub typhus incidences in the main epidemic areas of 10 provinces, China, 2006–2018 [J]. Front Public Health. 2022;10:992555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.KUO C C, HUANG J L, KO C Y, LEE P F, WANG HC. Spatial analysis of scrub typhus infection and its association with environmental and socioeconomic factors in Taiwan [J]. Acta Trop, 2011, 120(1–2): 52– 8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.KIM S, KIM Y. Hierarchical bayesian modeling of spatio-temporal patterns of scrub typhus incidence for 2009–2013 in South Korea [J]. Appl Geogr. 2018;100:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 63.KUMAR M, VALIAVEETIL K A, CHANDRAN J, MOHAN V R, CHANDRASEKAR K, GHOSH U et al. Scrub Typhus: a spatial and temporal analysis from South India [J]. J Trop Pediatr, 2022, 68(4). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.LV Y, GUO X G. JIN D C. Research Progress on Leptotrombidium deliense [J]. Korean J Parasitol. 2018;56(4):313–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.MIN K D, LEE J Y, SO Y, CHO S I. Deforestation increases the risk of Scrub Typhus in Korea [J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2019, 16(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.PEI Z F, FANG S B, YANG W N, WANG L, WU M Y, ZHANG Q F et al. The Relationship between NDVI and Climate Factors at Different Monthly Time Scales: A Case Study of Grasslands in Inner Mongolia, China (1982–2015) [J]. Sustainability, 2019, 11(24).

- 67.SHI Y, JIN N, MA X L, WU B Y, HE Q S, YUE C, et al. Attribution of climate and human activities to vegetation change in China using machine learning techniques [J]. Agr Forest Meteorol; 2020. p. 294.

- 68.PIAO S, TAN J, CHEN A, FU Y H, CIAIS P, LIU Q, et al. Leaf onset in the northern hemisphere triggered by daytime temperature [J]. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Scrub typhus data supporting the results of this study were available from the China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention (CISDCP), but the availability of these data was limited, which was used under the license of the project we are conducting. If appropriate permission for the data is required, please apply through the project to obtain the license.