Abstract

Background

With the rapid development of the internet, smartphones have become an indispensable part of our lives. However, prolonged, excessive and uncontrolled use may lead to the hidden danger of smartphone addiction, posing a threat to users’ physical and mental health. Previous studies have shown that social support may be a factor in alleviating smartphone addiction. However, its specific mechanism needs further exploration. The purpose of this study is to examine the chain mediating effects of negative emotions and self-control on the relationship between social support and smartphone addiction.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted from January 2022 to April 2023 in Sichuan Province, China, with 5,188 respondents aged 15 years or older. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to determine correlations between social support, negative emotions, self-control, and smartphone addiction. We construct a Structural Equation Model (SEM) to explore the pathways of smartphone addiction across different age groups.

Results

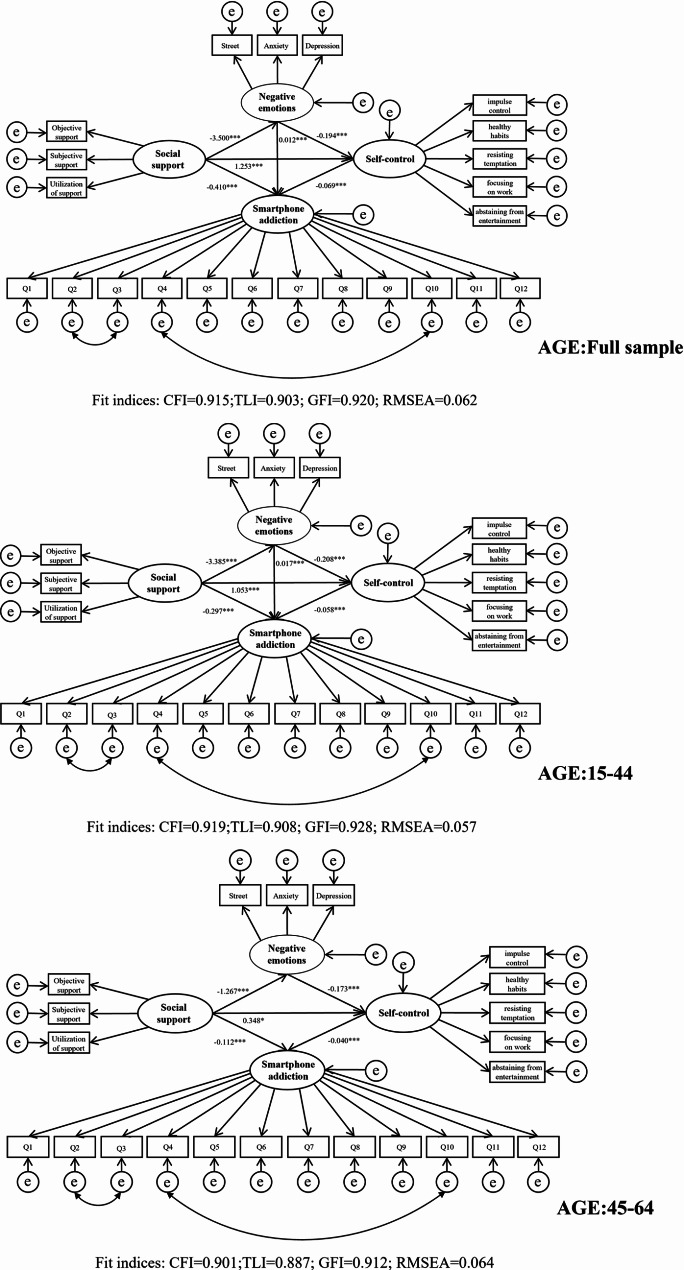

Social support, negative emotions, self-control, and smartphone addiction were found to be significantly related (p < 0.01).In the population aged 15–44, a complete SEM pathway analysis was achieved, while for the population aged 45–64, a simplified version of the pathway analysis was obtained. Among the population aged 65 and above, multiple pathways were found to be nonsignificant. For the full sample, social support not only exhibited a negative correlation with smartphone addiction (β = -0.410; 95% CI: -0.534 to -0.320) but also influenced smartphone addiction through three specific pathways: via negative emotions (β = -0.041; 95% CI: -0.066 to -0.021), via self-control (β = -0.087; 95% CI: -0.119 to -0.063), and via a sequential effect of negative emotions and self-control (β = -0.047; 95% CI: -0.062 to -0.036). The 15–44 age group demonstrated similar pathways to the full sample, whereas the 45–64 age group lost the pathway mediated solely by negative emotions.

Conclusions

Our study shows that high social support reduces smartphone addiction by diminishing negative emotions and improving self-control.The effect is more pronounced in the 15–44 age group.We suggest strengthening the social support system through more activities and urge relevant departments to improve the mental health education, enhance self-control training, and promote mental well-being to help avoid smartphone addiction.

Trial registration

Clinical trial number: not applicable.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12888-025-06615-8.

Keywords: Social support, Smartphone addiction, Negative emotions, Self-control

Introduction

With the rapid development of the internet, smartphones have become an indispensable part of most of our lives. From social interaction and information acquisition to entertainment, work, and study, we use smartphones to do almost everything. However, people who use smartphones excessively for extended periods of time and lack control may face the risk of smartphone addiction [1]. Studies have shown that smartphone addiction can cause not only physical issues, such as vision loss, cervical spine problems, and sleep disorders [2–4], but also psychological problems, such as depression, anxiety, and loneliness [5]. According to the 54th “Statistical Report on the Development of China’s Internet"released by the China Internet Network Information Center (CINIC) [6], as of June 2024, the number of mobile internet users in China reached 1.096 billion, accounting for about 77% of China’s population. The proportion of internet users using smartphones to access the internet is 99.7%, and the average time spent on the internet per person is 29.0 h per week. These data reflect the popularity of smartphones in daily life but also expose their potential addiction risks. In order to more effectively prevent and control smartphone addiction, it is particularly important to explore its influencing factors and addiction mechanisms.

Smartphone addiction is affected by many factors. It is generally believed that smartphone addiction is the same as other addictions, and its formation is affected by a person’s internal and external factors. Among them, social support, as an important external resource in individual life, is considered an important protective factor for addictive behavior. Research shows that social support can significantly predict addictive behaviors, such as substance abuse [7] and internet addiction [8]. Several empirical studies have shown that less social support is related to more severe internet addiction [9].According to the theory of compensatory internet use, smartphone addiction is an unhealthy coping tool used to escape real life and negative emotions and obtain emotional compensation in the virtual world [10]. When people lack sufficient social support in real life, they may turn to the internet to seek help in meeting their psychological needs [11]. In addition, a meta-analysis of 92 studies on smartphone addiction in mainland China showed a significant negative correlation between social support and smartphone addiction. [12] Previous research has shown that social support is closely related to smartphone addiction, but the underlying pathways have not yet been fully revealed. Therefore, this study aimed to further explore how social support affects smartphone addiction through indirect pathways.

Although social support is an external environmental factor, there is evidence that the social environment impacts the development of neural networks, thereby affecting individuals’ emotional management and behavioral inhibition [13, 14]. Generally speaking, social support characterized by emotional, informational, or instrumental help is regarded as a protective factor against negative emotions [15]. Previous research has shown that social support can significantly predict negative emotions. These negative emotions not only affect the individual’s psychological state but may also become an important cause of smartphone addiction. Research shows that when individuals are in a highly negative emotional state, they tend to seek emotional comfort through excessive smartphone use, leading to smartphone addiction [16]. This suggests that negative emotions may play a key mediating role in the relationship between social support and smartphone addiction.

Self-control is another key factor associated with smartphone addiction. Self-control refers to an individual’s ability to resist internal desires and external temptations in order to achieve long-term goals [17]. Individuals with high self-control can manage impulses and act according to expectations, while individuals with low self-control are easily tempted by external factors and behave impulsively [18, 19]. Studies have shown that self-control is closely related to smartphone addiction, with lower levels of self-control resulting in more serious smartphone addiction [20]. Generally, self-control is affected by the external environment. Social support, as an important environmental resource, affects an individual’s physical and mental health and behavior patterns. High levels of social support can help individuals better manage and restore self-control resources and enhance their ability to resist impulses and temptations. In addition to social support, limited studies have also reported that negative emotions can weaken an individual’s self-control ability.

The limited resource theory of self-control [21] that self-control resources are like muscles, which can be restored and strengthened through rest, relaxation, and energy replenishment. Successful self-control behavior depends on available self-control resources, but such resources are limited and can be depleted by activities such as behavioral inhibition and emotion regulation, as well as stressful events, making it difficult for individuals to cope with subsequent self-control tasks. According to this theory, the consumption and replenishment of self-control resources are affected by internal and external factors. For example, social support, as an effective social cognitive supplementary resource, can restore or enhance self-control resources in a timely manner [22]. Conversely, negative emotions, as a source of psychological stress, consume individuals’ self-control resources through their regulation and coping processes [23]. Wagner et al. pointed out that negative emotions increase an individual’s desire level, making them susceptible to external temptations and more sensitive to immediate rewards, thereby increasing their risk of failure in subsequent self-control tasks [18]. Therefore, we hypothesize that negative emotions affect individuals’ self-control ability and that self-control may be a potential mediating factor in the relationship between social support and smartphone addiction.

If smartphone addiction is regarded as a form of problem behavior, it can be comprehensively analyzed and interpreted through the framework of Problem Behavior Theory [24]. The theory posits that problem behavior is influenced by the combined effects of the personality system, social environment system, and behavior system. The explanatory variables within these systems may either promote or inhibit problem behavior, but their combined effect generates a tendency or likelihood of the occurrence of problem behaviors, which can be used to predict and explain variations in problem behavior. In other words, Problem Behavior Theory encompasses factors such as individual psychology, usage motivation, emotional regulation and social ability, with a focus on the interaction between individual factors and the social environment. Based on the theoretical framework, the present study considers social support as an environmental factor, and negative emotions and self-control as individual factors. A structural equation model is constructed to explore the influence of social support on smartphone addiction. Additionally, existing research on smartphone addiction mainly focuses on adolescents and college student [25]. Most studies emphasize the direct relationship between social support and smartphone addiction. However, few studies have delved into the underlying mechanisms through which social support influences smartphone addiction. To address these limitations, we include residents aged 15 and older from Sichuan Province, China, as the research population, aiming to analyze whether the influence of social support on smartphone addiction varies across different age groups. Our hypotheses are as follows:

Hypothesis 1

Negative emotions mediate the relationship between social support and smartphone addiction.

Hypothesis 2

Self-control plays a mediating role in the relationship between social support and smartphone addiction.

Hypothesis 3

Negative emotions and self-control jointly play a chain mediating role in the relationship between social support and smartphone addiction. The order of the pathway is social support → negative emotions → self-control → smartphone addiction.

Methods

Participants and procedures

A household-based cross-sectional survey was conducted from January 2022 to April 2023 in Sichuan Province in southwestern China. A stratified multi-stage sampling method was used to extract samples. First, after considering factors such as geographical location, population size, and economic level, four locations were selected as survey areas: Wenjiang District of Chengdu City, Fushun County of Zigong City, Qingchuan County of Guangyuan City, and Xide County of Liangshan Prefecture. Then, from the four areas, two subdistricts and two townships were selected, of which two communities were selected from each subdistrict and two villages were selected from each township for investigation. The in-home survey method was adopted, and face-to-face interviews were conducted on all residents who met the inclusion criteria. To ensure the quality of the survey, each investigator was rigorously trained before the survey, and a quality supervision team was set up to implement quality control on every aspect of the on-site survey.

All residents included in the survey met the following three conditions: they (1) voluntarily and independently participated in the survey; (2) were 15 years old or older; (3) had lived in the sample area of Sichuan Province for at least 6 months. After excluding respondents who did not meet the conditions, a total of 6,189 residents participated in the survey, of which 5,551 owned smartphones. Because the dependent variable of this study was smartphone addiction, only the data of smartphones users were included in the subsequent analysis. In order to avoid estimation bias, questionnaires with missing values were considered invalid in the quality control procedure. In the end, this study included 5,188 respondents, for an overall response rate of 93.46%.

The survey was conducted through face-to-face questioning, where data on socio-demographic characteristics (such as age, gender, marital status, education level, employment status, and Hukou), social support, mental health, and smartphone use were collected. To reduce reporting bias, we strictly adhered to the anonymity and confidentiality of the survey. Additionally, some items were scored using reverse scoring.At the end of the survey, residents who completed the questionnaire received a cash prize of a specific randomized amount (¥10, ¥15, or ¥20). Strict quality control was performed at every step of the survey.

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Ethics Approval No.: 2023KL-134). All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the survey.To protect privacy, the data is anonymized during the collection process and contains no information that can directly identify individuals. All data is stored in an encrypted database with access only to authorized personnel and with regular backup and data destruction procedures to ensure data security and privacy protection.

Measures

Demographic variables

There were three marital status categories: single, married, and divorced/widowed/other; four education level categories: primary school and below, junior high school, high school (vocational high school), and college and above; four employment status categories: employed, retired, student, and unemployed; and two household registration type categories: urban and rural. Other covariates included age, gender, and personal annual income.

Social support

The level of social support was measured using the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS) [26],a 10-item scale that includes three dimensions: objective support, subjective support, and utilization of support. Objective support refers to the support actually received in life; subjective support refers to the support given by others that an individual subjectively feels and experiences; and utilization of support refers to the use of social support received by an individual. The total score is the sum of the scores of the 10 items, with higher scores indicating better social support. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this study was 0.670.

Smartphone addiction

Smartphone addiction was measured using the Chinese Smartphone Addiction Scale(SAS-C) [27],which consists of 12 items and uses a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” with higher scores indicating more severe smartphone addiction. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this study was 0.920.

Negative emotions

The Chinese version of the Depression-Anxiety-Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) [28] was used to measure negative emotions.The DASS-21 contains 21 items, and the three subscales of depression, anxiety, and stress contain seven items each, all of which are scored on a 4-point scale ranging from “0” (Does not apply to me at all) to “3” (Applies to me most of the time). Multiplying the score of each subscale by 2 yields the score of a subscale, with higher scores indicating more negative emotions. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this study was 0.909.

Self-control

Self-control was measured using the Chinese version of the Self-Control Scale (SCC). This scale was originally developed by Tangney et al. [17] and has been adapted and revised by Chinese scholars [29]. It is now widely used to assess self-control levels in various studies within the Chinese context, consisting of five dimensions and 19 questions.The five dimensions are resisting temptation, impulse control, healthy habits, focusing on work, and abstaining from entertainment. The questions are scored on a 5-point Likert scale, with each question ranging from “1” (Does not apply to me at all) to “5” (Applies to me most of the time), and some questions are reverse-scored. Higher scores indicate stronger self-control ability. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this study was 0.827.

Statistical analysis

First, we used descriptive analysis to describe the demographic data. Secondly, we used the Wilcoxon rank sum test and Kruskal-Wallis test to compare the differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of smartphone users. Third, we tested the relationships between variables through Spearman correlation analysis. Finally, Structural equation modeling was then evaluated using AMOS 24.0 for the entire sample and across age groups to estimate direct, indirect, and total effects. We tested the theoretical model by repeatedly sampling 5,000 samples to estimate 95% confidence intervals (CI) for mediated effects. If the 95% CI does not include 0, the data are said to be statistically significant.The adequacy of the model fit was evaluated using the following criteria GFI, CFI and TLI ≥ 0.90, RMSEA ≤ 0.08.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants involved in this study. A total of 6,189 people participated in the survey, of which 5,188 were smartphone users. Among them, 2,581 people aged 15–44 used smartphones, the utilization rate of smart phones was 98.70%. Among the people aged 45–64, 1,884 people used smartphones, the utilization rate of smart phones was 92.35%. Among the people aged 65 and above, 723 people used smart phones, the utilization rate of smart phones was 47.13%. We found significant differences in SAS-C scores based on sociodemographic variables (including age, Hukou, marital status, education level, employment status, and personal annual income). In addition, Table 2 shows that differences in SAS-C scores across various sociodemographic variables among different age groups. However, no significant differences were observed in SAS-C scores across these sociodemographic variables within the older adult population.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of included participants with mobile phone addiction (N = 5,188)

| Variables | N(%) | smartphone addiction score | Z/H | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± Std | ||||

| Age | 706.425 | < 0.001 | ||

| 15~ | 2581(49.75%) | 29.79 ± 8.636 | ||

| 45~ | 1884(36.31%) | 23.527 ± 8.52 | ||

| ≥ 65 | 723(13.94%) | 22.001 ± 8.804 | ||

| Sex | -0.659 | 0.51 | ||

| Female | 2876(55.44%) | 26.367 ± 9.363 | ||

| Male | 2312(44.56%) | 26.509 ± 9.119 | ||

| Hukou | 3.855 | < 0.001 | ||

| rural | 3181(61.31%) | 26.051 ± 8.985 | ||

| urban | 2007(38.69%) | 27.03 ± 9.639 | ||

| Marital status | 447.209 | < 0.001 | ||

| Single | 1363(26.27%) | 30.886 ± 8.329 | ||

| Married | 3599(69.37%) | 24.846 ± 9.046 | ||

| Widowed/Divorced/Other | 226(4.36%) | 24.783 ± 9.101 | ||

| Education Level | 433.939 | < 0.001 | ||

| Primary and below | 1471(28.35%) | 23.107 ± 8.514 | ||

| Junior high school | 1431(27.58%) | 25.591 ± 9.056 | ||

| High school /Vocational high school | 966(18.62%) | 27.959 ± 9.319 | ||

| college and above | 1320(25.44%) | 29.925 ± 8.75 | ||

| personal annual income(¥) | 78.97 | < 0.001 | ||

| 0~ | 2091(40.30%) | 26.59 ± 9.351 | ||

| 10,000~ | 1782(34.35%) | 25.07 ± 8.895 | ||

| 50,000~ | 1315(25.35%) | 28.019 ± 9.311 | ||

| Occupation | 359.943 | < 0.001 | ||

| Employed | 2619(50.48%) | 26.756 ± 9.137 | ||

| Retired | 688(13.26%) | 22.936 ± 8.941 | ||

| Students | 830(16.00%) | 30.872 ± 8.115 | ||

| unemployed | 1051(20.26%) | 24.398 ± 9.092 |

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of smartphone-addicted participants across different age groups

| Variables | 15~(2581) | 45~(1884) | ≥ 65(723) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%) | M ± Std | Z/H | P | N(%) | M ± Std | Z/H | P | N(%) | M ± Std | Z/H | P | |

| Sex | -0.038 | 0.97 | 0.224 | 0.823 | -0.576 | 0.565 | ||||||

| Female | 1383(53.58%) | 29.818 ± 8.727 | 1124(59.66%) | 23.603 ± 8.667 | 369(51.04%) | 21.851 ± 9.009 | ||||||

| Male | 1198(46.42%) | 29.758 ± 8.533 | 760(40.34%) | 23.413 ± 8.300 | 354(48.96%) | 22.158 ± 8.596 | ||||||

| Hukou | 4.321 | < 0.001 | 2.874 | 0.004 | 1.825 | 0.068 | ||||||

| rural | 1622(62.84%) | 29.243 ± 8.486 | 1250(66.35%) | 23.087 ± 8.198 | 309(42.74%) | 21.288 ± 8.358 | ||||||

| urban | 959(37.16%) | 30.715 ± 8.811 | 634(33.65%) | 24.393 ± 9.065 | 414(57.26%) | 22.534 ± 9.097 | ||||||

| Marital status | 65.261 | < 0.001 | 3.028 | 0.22 | 1.013 | 0.603 | ||||||

| Single | 1318(51.07%) | 31.099 ± 8.161 | 35(1.86%) | 25.029 ± 10.910 | 10(1.38%) | 23.300 ± 9.967 | ||||||

| Married | 1210(46.88%) | 28.353 ± 8.916 | 1757(93.26%) | 23.426 ± 8.480 | 632(87.41%) | 22.078 ± 8.792 | ||||||

| Widowed/Divorced/Other | 53(2.05%) | 30.038 ± 8.584 | 92(4.88%) | 24.870 ± 8.184 | 81(11.20%) | 21.247 ± 8.825 | ||||||

| Education Level | 69.176 | < 0.001 | 31.253 | < 0.001 | 0.711 | 0.871 | ||||||

| Primary and below | 284(11.00%) | 26.856 ± 8.329 | 818(43.42%) | 22.358 ± 8.202 | 369(51.04%) | 21.881 ± 8.558 | ||||||

| Junior high school | 557(21.58%) | 28.750 ± 8.840 | 673(35.72%) | 24.065 ± 8.470 | 201(27.80%) | 21.940 ± 8.889 | ||||||

| High school /Vocational high school | 636(24.64%) | 29.915 ± 8.845 | 233(12.37%) | 24.837 ± 8.934 | 97(13.42%) | 22.629 ± 9.213 | ||||||

| college and above | 1104(42.77%) | 30.997 ± 8.245 | 160(8.49%) | 25.325 ± 8.956 | 56(7.75%) | 21.929 ± 9.552 | ||||||

| personal annual income(¥) | 15.123 | 0.001 | 18.853 | < 0.001 | 1.314 | 0.518 | ||||||

| 0~ | 1122(43.47%) | 30.198 ± 8.607 | 696(36.94%) | 22.736 ± 8.347 | 273(37.76%) | 21.590 ± 8.469 | ||||||

| 10,000~ | 630(24.41%) | 28.711 ± 8.420 | 841(44.64%) | 23.502 ± 8.390 | 311(43.02%) | 21.933 ± 8.745 | ||||||

| 50,000~ | 829(32.12%) | 30.058 ± 8.777 | 347(18.42%) | 25.173 ± 8.956 | 139(19.23%) | 22.964 ± 9.544 | ||||||

| Occupation | 33.112 | < 0.001 | 5.36 | 0.147 | 0.327 | 0.955 | ||||||

| Employed | 1427(55.29%) | 29.501 ± 8.730 | 1069(56.74%) | 23.679 ± 8.531 | 123(17.01%) | 21.642 ± 8.131 | ||||||

| Retired | 6(0.23%) | 25.333 ± 6.683 | 306(16.24%) | 23.699 ± 8.597 | 376(52.01%) | 22.277 ± 9.205 | ||||||

| Students | 821(31.81%) | 30.917 ± 8.088 | 5(0.27%) | 31 ± 10.909 | 4(0.55%) | 21.5 ± 6.403 | ||||||

| unemployed | 327(12.67%) | 28.303 ± 9.247 | 504(26.75%) | 23.024 ± 8.400 | 220(30.43%) | 21.741 ± 8.532 | ||||||

Correlation analysis

Social support was negatively correlated with negative emotions (r = -0.194, P < 0.01) and smartphone addiction (r = -0.225, P < 0.01) but positively correlated with self-control (r = 0.170, P < 0.01). Self-control was negatively correlated with negative emotions (r = -0.343, P < 0.01) and smartphone addiction (r = -0.282, P < 0.01). Negative emotions were positively correlated with smartphone addiction (r = 0.252, P < 0.01). See Table 3.

Table 3.

Spearman correlation coefficients between key study variables (N = 5,188)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Social support | 1.000 | |||

| 2.Negative Emotions | -0.194** | 1.000 | ||

| 3.Self-control | 0.170** | -0.343** | 1.000 | |

| 4.Smartphone addiction | -0.225** | 0.252** | -0.282** | 1.000 |

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

Structural equation modeling

All variables were included in the structural equation model, and confirmatory factor analysis revealed that the factor loadings of all latent variables were significant at the p < 0.001 level. For the full sample and the 15–44 age group, the factor loadings were all above 0.3, indicating acceptable convergent validity of the model. The factor loading results are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The fit indices of the modified model indicated that CFI and GFI were both greater than 0.9, the TLI for the full sample and the 15–44 age group are greater than 0.9, while the TLI for the 45–64 age group is close to 0.9. RMSEA was less than 0.08, demonstrating a good model fit. The fit results are presented in Fig. 1. Since multiple pathways analysis results for the group aged 65 and above were not statistically significant, no further discussion of these results will be provided.

Fig. 1.

Models for social support to smartphone addiction in different age groups. Solid lines indicate direct effects.***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05;

Figure 1 illustrates the model of smartphone addiction for participants of different age groups. For the full sample the 15–44 age group, all direct pathways in the model were statistically significant, and the model remained complete. In the the 45–64 age group and 65 years and above group models, the direct pathway from negative emotions to smartphone addiction was not significant, so this pathway was removed. In the 65 years and above group model, the pathways from social support to negative emotions, social support to self-control, and negative emotions to smartphone addiction were all not significant.

Table 4 and Figure 1 present the results of the regression analysis and pathways analysis. In the full sample, social support was negatively correlated with negative emotions (β = -3.500, p < 0.001), positively correlated with self-control (β = 1.253, p < 0.001), and negatively correlated with smartphone addiction (β = -0.410, p < 0.001). Negative emotions were negatively correlated with self-control (β = -0.194, p < 0.001). Smartphone addiction was positively correlated with negative emotions (β = 0.012, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with self-control (β = -0.069, p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Results of structural model for full sample and subsamples

| Model pathways | Full sample | 15–44 years old | 45–64 years old | over 65 years old | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | CR | β | SE | CR | β | SE | CR | β | SE | CR | ||||||||

| negative emotions←social support | -3.500*** | 0.405 | -8.641 | -3.385*** | 0.436 | -7.765 | -1.267*** | 0.290 | -4.374 | -0.841 | 0.503 | -1.674 | |||||||

| self-control←social support | 1.253*** | 0.182 | 6.893 | 1.053*** | 0.198 | 5.310 | 0.348* | 0.148 | 2.346 | 0.213 | 0.253 | 0.842 | |||||||

| smartphone addiction←social support | -0.410*** | 0.052 | -7.851 | -0.297*** | 0.048 | -6.160 | -0.112*** | 0.033 | -3.442 | -0.160* | 0.064 | -2.508 | |||||||

| self-control←negative emotions | -0.194*** | 0.011 | -18.131 | -0.208*** | 0.015 | -14.271 | -0.173*** | 0.020 | -8.625 | -0.214*** | 0.031 | -6.984 | |||||||

| smartphone addiction←negative emotions | 0.012*** | 0.003 | 4.544 | 0.017*** | 0.003 | 5.092 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 1.512 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.783 | |||||||

| smartphone addiction←self-control | -0.069*** | 0.005 | -13.702 | -0.058*** | 0.006 | -9.219 | -0.040*** | 0.007 | -5.539 | -0.039** | 0.012 | -3.228 | |||||||

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05; β, standardized coefficient; SE, standard error; CR, critical ratio

For participants aged 15–44 years, social support was negatively correlated with negative emotions (β = -3.385, p < 0.001), positively correlated with self-control (β = 1.053, p < 0.001), and negatively correlated with smartphone addiction (β = -0.297, p < 0.001). Negative emotions were negatively correlated with self-control (β = -0.208, p < 0.001). Smartphone addiction was positively correlated with negative emotions (β = 0.017, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with self-control (β = -0.058, p < 0.001).

For participants aged 45–64 years, social support was negatively correlated with negative emotions (β = -1.267, p < 0.001), positively correlated with self-control (β = 0.348, p < 0.05), and negatively correlated with smartphone addiction (β = -0.112, p < 0.001). Negative emotions were negatively correlated with self-control (β = -0.173, p < 0.001). Smartphone addiction was negatively correlated with self-control (β = -0.040, p < 0.001), but smartphone addiction was not significantly associated with negative emotions.

For participants aged 65 and above, social support was negatively correlated with smartphone addiction (β = -0.160, p < 0.05), negative emotions were negatively correlated with self-control (β = -0.214, p < 0.001), and self-control was negatively correlated with smartphone addiction (β = -0.039, p < 0.01). Other pathways were not significant.

Table 5 presents the results of the mediation analysis. In the full sample, the direct effect value was -0.410, accounting for 70.09% of the total effect, while the total indirect effect value was -0.175, accounting for 29.91% of the total effect. Specifically, the indirect effects were mediated through three paths: Path 1 (Social support → Negative emotions → Smartphone addiction) with an effect value of -0.041, accounting for 7.01% of the total effect; Path 2 (Social support → Self-control → Smartphone addiction) with an effect value of -0.087, accounting for 14.87% of the total effect; and Path 3 (Social support → Negative emotions → Self-control → Smartphone addiction) with an effect value of -0.047, accounting for 8.03% of the total effect.

Table 5.

Direct and indirect effects and 95% confidence intervals (CI)

| Model pathways | Full sample | 15–44 years old | 45–64 years old | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95%CI | β | 95%CI | β | 95%CI | ||||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Total effect | |||||||||||

| social support→smartphone addiction | -0.585 | -0.734 | -0.472 | -0.456 | -0.586 | -0.355 | -0.135 | -0.210 | -0.077 | ||

| Direct effect | |||||||||||

| social support→smartphone addiction | -0.410 | -0.534 | -0.320 | -0.297 | -0.404 | -0.213 | -0.112 | -0.184 | -0.055 | ||

| Indirect effect | -0.175 | -0.159 | -0.023 | ||||||||

| social support→negative emotions→smartphone addiction | -0.041 | -0.066 | -0.021 | -0.057 | -0.090 | -0.029 | |||||

| social support→self-control→smartphone addiction | -0.087 | -0.119 | -0.063 | -0.061 | -0.091 | -0.038 | -0.014 | -0.029 | -0.003 | ||

| social support→negative emotions→self-control→smartphone addiction | -0.047 | -0.062 | -0.036 | -0.041 | -0.058 | -0.029 | -0.009 | -0.017 | -0.004 | ||

β, standardized coefficient

For participants aged 15–44 years, the direct effect value was -0.297, accounting for 65.13% of the total effect, and the total indirect effect value was -0.159, accounting for 34.87% of the total effect. Path 1 had an effect value of -0.057, accounting for 12.50% of the total effect; Path 2 had an effect value of -0.061, accounting for 13.38% of the total effect; and Path 3 had an effect value of -0.041, accounting for 8.99% of the total effect.For participants aged 45–64 years, the direct effect value was -0.112, accounting for 82.96% of the total effect, while the total indirect effect value was -0.023, accounting for 17.04% of the total effect. Path 2 had an effect value of -0.014, accounting for 10.37% of the total effect, and Path 3 had an effect value of -0.009, accounting for 6.67% of the total effect.Additionally, the 95% confidence intervals for each pathway did not include 0, indicating that the mediating roles of negative emotions and self-control in the relationship between social support and smartphone addiction were significant in the full sample and the 15–44 age group. These results support our hypotheses.

Discussion

This study explored the impact of social support on smartphone addiction and examined the mechanism of action of these variables in different age groups. The results showed that social support and self-control were negatively correlated with smartphone addiction, while negative emotions were positively correlated with smartphone addiction. The mediating effect of negative emotions and self-control also further verified the indirect effect of social support on smartphone addiction. These findings offer a new perspective for understanding the psychological mechanism of smartphone addiction and provide a theoretical basis for the effective prevention and intervention of smartphone addiction behavior.

The study demonstrates that the more social support people receive, the less likely they are to develop smartphone addiction, which is consistent with previous research results. Social support has been found to be associated with a range of positive outcomes, including lower levels of internet addiction [8, 30]. According to the compensatory internet use theory [11], smartphone addiction is a compensatory behavior for people coping with negative events and emotional problems in their lives. Social psychological problems or unmet real-life needs can motivate people to use the internet. If people’s social support needs are not met in real life, they are likely to seek social support to meet their psychological needs in the virtual and anonymous online world. In particular, when they lack intimacy or are ostracized in reality, online chat rooms and forums can provide a communication platform for individuals to find people who resonate with them and gain emotional support and recognition. The current results show that lack of social support is an important external factor leading to the formation of smartphone addiction.The study verified the mechanisms of social support, negative emotions and self-control in mobile phone addiction through different age analysis and found that these mechanisms vary among the 15–44, 45–64, and 65 years and above.

The study found that the effects of social support on smartphone addiction can be mediated through negative emotions in people aged 15–44 years, validating Hypothesis 1. Specifically, low social support levels are positively correlated with one’s negative emotions, a risk factor for smartphone addiction. Social support is an important way to meet an individual’s emotional needs. Studies have found that strong social support helps to enhance positive emotions and effectively alleviate negative ones, especially depression [31]. Once lost, individuals tend to feel lonely, helpless, and marginalized, which directly triggers the generation of negative emotions. In addition, other studies have revealed how low social support affects an individual’s emotion regulation ability through neurobiological mechanisms. Specifically, low social support may interfere with the brain’s social cognitive and cognitive control networks, especially the function of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the temporoparietal junction [32, 33], making it difficult for individuals to accurately capture and understand the emotional signals of others in social interactions, thereby exacerbating social isolation. At the same time, diminished activity of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex [34, 35] weakens an individual’s ability to self-regulate emotions. The dysfunction of these brain regions makes it easier for negative emotions to accumulate and persist, ultimately increasing the risk of emotional disorders such as anxiety and depression. When faced with the challenges of these negative emotions, some people tend to seek a way to escape reality [36]. People aged 15–44 are at a critical stage of social development, and low social support levels can easily lead to negative emotions such as loneliness and depression.The virtual world constructed by smartphones has become a safe haven for them to gain temporary comfort with its unique charm. but this relief effect is short-lived and has the potential risk of addiction. Therefore, this study emphasizes that maintaining positive emotions may buffer the relationship between social support and smartphone addiction.

As expected, this study found that self-control similarly played a mediating role between social support and smartphone addiction, mainly in people aged 15–44 and 45–64 years, validating Hypothesis 2. That is, low self-control is associated with low social support, and lack of self-control is a risk factor for smartphone addiction.In contrast, people with high self-control tend to be more able to manage their smartphone use and less likely to fall into an addictive state.This result is consistent with the conclusions of earlier studies [37, 38]. Functional brain imaging studies also support this view that one of the core clinical symptoms of addiction is a decline in self-control ability, which is usually manifested as impulsive behavior and a desire for instant gratification.Specific neural mechanisms show that impaired self-control ability is associated with reduced activity in brain regions such as the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and mPFC [39], which play a key role in impulse inhibition, decision making, and behavior regulation.As mentioned above, individual’s self-control ability is a limited psychological resource.When people exhaust their self-control resources, they are unable to promote their positive behaviors or inhibit their negative behaviors. When individuals lack sufficient social support, they may experience more emotional stress, loneliness, and negative emotions, all of which require additional psychological resources to cope with, which consumes more of their self-control resources and leads to a decrease in self-control. In such cases, individuals are more likely to overuse their smartphones to escape real-life pressures or regulate their emotions, forming addictive behaviors.Therefore, in the process of intervening in smartphone addiction, improving individuals’ self-control ability and strengthening their social support systems are key steps.The self-control of individuals aged 15–44 may not be fully developed, making them more vulnerable to external temptations. Additionally, due to their higher social needs, this age group is more likely to view smartphones as essential tools for fulfilling social demands and receiving instant feedback. In the absence of social support, the depletion of self-control resources can ultimately lead to addictive behaviors. For individuals aged 45–64, while their self-control is generally more mature, they face unique pressures from family, work, and society. Without adequate social support to alleviate these pressures, psychological resources may be excessively depleted, leading to a decline in self-control, making this group more likely to use smartphones for temporary stress relief. Particularly, when smartphone use evolves into excessive use, it is more likely to develop into addictive behavior.

Finally, we also found the effect of social support on smartphone addiction through the chain mediating effect of negative emotions and self-control, mainly in people aged 15–44 years.The results showed that low social support not only directly triggers an individual’s negative emotions but also further depletes self-control resources by increasing negative emotions, ultimately leading to smartphone addiction. For people aged 15–44 years, emotion regulation may not be fully mature and more vulnerable to external environment and emotional fluctuations. Individuals who lack social support are more likely to have negative emotions such as loneliness, anxiety, or depression [40, 41]. According to the buffering theory of social support, when individuals face stress or emotional distress, support from social relationships can effectively alleviate negative emotions [42]. However, when social support is insufficient, individuals lose this resource for emotional regulation, and negative emotions are easily exacerbated, which provides emotional motivation for smartphone addiction. Second, negative emotions further promote smartphone addiction by depleting individuals’ self-control resources and weakening self-control [23]. The discovery of this chain mediating effect further deepens our understanding of the mechanism behind smartphone addiction, indicating that smartphone addiction is the result of not a single factor but the interaction of multiple psychological and external factors.Therefore, the study suggests that interventions to prevent and address smartphone addiction should focus on enhancing social support, improving emotional regulation, and strengthening self-control. For instance, fostering hobbies among individuals aged 15–44 can help develop healthier stress-coping strategies and divert attention from smartphones. Encouraging physical exercise and mental health education for individuals aged 45–64 can improve their ability to cope with negative emotions such as anxiety and depression. Additionally, promoting social engagement and building a strong social support network can reduce the impact of emotional fluctuations on behavior, thereby effectively reducing the risk of smartphone dependence.

Limitation

Our study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to infer causal relationships between social support and smartphone addiction. Cross-sectional studies can only observe the associations between variables, without being able to determine the direction of causality. Future research could incorporate longitudinal data to provide stronger evidence by observing changes in smartphone addiction and other variables over time. Second, the use of self-report questionnaires to measure smartphone addiction may introduce potential reporter bias. Questionnaire surveys rely on participants’ subjective recall and self-assessment, which may be influenced by personal biases and could affect the study’s results. Finally, this study was conducted in Sichuan Province, China, with a family-based survey design, meaning that the generalizability of our findings may be limited to our specific study population and environment. Research conclusions may be difficult to apply in different socio-cultural contexts. Future studies could consider including a broader population to develop more universally applicable intervention strategies.

Conclusion

Despite the above limitations, this study provides important evidence on the link between social support and smartphone addiction in the Chinese population.More specifically, the main contribution of this study is to clarify the mediating roles of negative emotions and self-control between social support and smartphone addiction in different age groups, revealing the importance of psychological factors in the process of social support affecting smartphone addiction. This provides new insights for future interventions and prevention strategies for smartphone addiction.The results of this study show that enhancing social support may effectively reduce the risk of smartphone addiction.Strong social support can not only alleviate individuals’ negative emotions but also enhance their self-control ability, thereby helping them better manage their smartphone use.Given the prevalence of smartphone addiction and its significant impact on personal physical and mental health, relevant government departments must take multiple measures to help people to put down their smartphones, reduce addictive behaviors, and thus promote public health.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the subjects who participated in this study.

Author contributions

LY participated in the conceptualization, revision of the article, and final approval of the article, GPZ participated in data collection, statistical analysis, drafting the manuscript and final approval of the version to be submitted, YS, YLZ, HWL and JSZ participated in research design, revision of the article, and final approval of the article.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) [grant number 72174032 to Lian Yang].

Data availability

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the privacy of individuals that participated in the study. The data will be shared on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research plan was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine Affiliated Hospital (Ethics Approval No. 2023KL-134). All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the survey.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the data.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Huang H, Wan X, Lu G, Ding Y, Chen C. The relationship between Alexithymia and Mobile phone addiction among Mainland Chinese students: a Meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:754542. 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.754542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meo SA, Al-Drees AM. Mobile phone related-hazards and subjective hearing and vision symptoms in the Saudi population. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2005;18(1):53–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hakala PT, Rimpelä AH, Saarni LA, Salminen JJ. Frequent computer-related activities increase the risk of neck-shoulder and low back pain in adolescents. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(5):536–41. 10.1093/eurpub/ckl025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemola S, Perkinson-Gloor N, Brand S, Dewald-Kaufmann JF, Grob A. Adolescents’ electronic media use at night, sleep disturbance, and depressive symptoms in the smartphone age. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(2):405–18. 10.1007/s10964-014-0176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elhai JD, Levine JC, Dvorak RD, Hall BJ. Fear of missing out, need for touch, anxiety and depression are related to problematic smartphone use. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;63:509–16. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.079. [Google Scholar]

- 6.China Internet Network Information Center [CNNIC]. (2024). Statistical Report on Development of Internet in China. Available at: https://www.cnnic.cn/n4/2024/0829/c88-11065.html

- 7.Mazzoni E, Baiocco L, Cannata D, Dimas I. Is internet the cherry on top or a crutch? Offline social support as moderator of the outcomes of online social support on problematic internet use. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;56:369–74. 10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.032. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu XS, Zhang ZH, Zhao F, Wang WJ, Li YF, Bi L, Qian ZZ, Lu SS, Feng F, Hu CY, et al. Prevalence of internet addiction and its association with social support and other related factors among adolescents in China. J Adolesc. 2016;52:103–11. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang S, Tian Y, Sui Y, Zhang D, Shi J, Wang P, Meng W, Si Y. Relationships between Social Support, loneliness, and internet addiction in Chinese Postsecondary students: a longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1707. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ge J, Liu Y, Cao W, Zhou S. The relationship between anxiety and depression with smartphone addiction among college students: the mediating effect of executive dysfunction. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1033304. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1033304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kardefelt-Winther D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;31:351–4. 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wan X, Huang H, Jia R, Liang D, Lu G, Chen C. Association between mobile phone addiction and social support among mainland Chinese teenagers: a meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;10:911560. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.911560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmes CJ, Barton AW, MacKillop J, Galván A, Owens MM, McCormick MJ, Yu T, Beach SRH, Brody GH, Sweet LH. Parenting and Salience Network Connectivity among African americans: a protective pathway for Health-Risk behaviors. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(5):365–71. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLaughlin KA, Peverill M, Gold AL, Alves S, Sheridan MA. Child maltreatment and neural systems underlying emotion regulation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(9):753–62. 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gariépy G, Honkaniemi H, Quesnel-Vallée A. Social support and protection from depression: systematic review of current findings in western countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(4):284–93. 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.169094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elhai JD, Dvorak RD, Levine JC, Hall BJ. Problematic smartphone use: a conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J Affect Disord. 2017;207:251–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Pers. 2004;72(2):271–24. 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner DD, Heatherton TF. Emotion and self-regulation failure. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2014. p. 613–628. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heatherton TF, Wagner DD. Cognitive neuroscience of self-regulation failure. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(3):132–9. 10.1016/j.tics.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan W, Ma Y, Long Y, Wang Y, Zhao Y. Self-control mediates the relationship between time perspective and mobile phone addiction in Chinese college students. PeerJ. 2023;11:e16467. 10.7717/peerj.16467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Tice DM. The Strength Model of Self-Control. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16(6):351–5. 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00534.x. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiaoling Y, Yunxia W. The relationship between Social Support and Problem Behavior of Senior High School students: the role of Self Control. J Gannan Normal Univ. 2021;42(05):105–10. 10.13698/j.cnki.cn36-1346/c.2021.05.017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chester DS, Lynam DR, Milich R, Powell DK, Andersen AH, DeWall CN. How do negative emotions impair self-control? A neural model of negative urgency. NeuroImage. 2016;132:43–50. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jessor R. Problem-behavior theory, psychosocial development, and adolescent problem drinking. Br J Addict. 1987;82(4):331–42. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01490.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Olson JA, Sandra DA, Colucci ÉS, Al Bikaii A, Chmoulevitch D, Nahas J, Raz A, Veissière SPL. Smartphone addiction is increasing across the world: a meta-analysis of 24 countries. Comput Hum Behav. 2022;129:107138. 10.1016/j.chb.2021.107138. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao SY. The theoretical basis and research application of social support rating scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;4:98–100.

- 27.Li L. Impulsivity, other related factors and therapy ofsmartphone addiction in college students. Jilin University; 2016.

- 28.Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44(Pt 2):227–39. 10.1348/014466505x29657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan S, Guo Y. Revision of Self-Control Scale for Chinese College Students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2008;05:468–70. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeh YC, Ko HC, Wu JY, Cheng CP. Gender differences in relationships of actual and virtual social support to internet addiction mediated through depressive symptoms among college students in Taiwan. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11(4):485–7. 10.1089/cpb.2007.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalgard OS, Bjørk S, Tambs K. Social support, negative life events and mental health. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166(1):29–34. 10.1192/bjp.166.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dufour N, Redcay E, Young L, Mavros PL, Moran JM, Triantafyllou C, Gabrieli JD, Saxe R. Similar brain activation during false belief tasks in a large sample of adults with and without autism. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e75468. 10.1371/journal.pone.0075468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saxe R, Kanwisher N. People thinking about thinking people. The role of the temporo-parietal junction in theory of mind. NeuroImage. 2003;19(4):1835–42. 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morawetz C, Berboth S, Bode S. With a little help from my friends: the effect of social proximity on emotion regulation-related brain activity. NeuroImage. 2021;230:117817. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.117817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reeck C, Ames DR, Ochsner KN. The social regulation of emotion: an Integrative, cross-disciplinary model. Trends Cogn Sci. 2016;20(1):47–63. 10.1016/j.tics.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang W, Mehmood A, Li P, Yang Z, Niu J, Chu H, Qiao Z, Qiu X, Zhou J, Yang Y, et al. Perceived stress and Smartphone Addiction in Medical College students: the mediating role of negative emotions and the moderating role of Psychological Capital. Front Psychol. 2021;12:660234. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.660234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim Y, Jeong JE, Cho H, Jung DJ, Kwak M, Rho MJ, Yu H, Kim DJ, Choi IY. Personality factors Predicting Smartphone Addiction Predisposition: behavioral inhibition and activation systems, Impulsivity, and self-control. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(8):e0159788. 10.1371/journal.pone.0159788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cho HY, Kim DJ, Park JW. Stress and adult smartphone addiction: mediation by self-control, neuroticism, and extraversion. Stress Health. 2017;33(5):624–30. 10.1002/smi.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(11):652–69. 10.1038/nrn3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tough H, Siegrist J, Fekete C. Social relationships, mental health and wellbeing in physical disability: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):414. 10.1186/s12889-017-4308-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Domènech-Abella J, Lara E, Rubio-Valera M, Olaya B, Moneta MV, Rico-Uribe LA, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Mundó J, Haro JM. Loneliness and depression in the elderly: the role of social network. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(4):381–90. 10.1007/s00127-017-1339-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hyde LW, Gorka A, Manuck SB, Hariri AR. Perceived social support moderates the link between threat-related amygdala reactivity and trait anxiety. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(4):651–6. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the privacy of individuals that participated in the study. The data will be shared on reasonable request from the corresponding author.