Abstract

Importance

Deregulation of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) occurs in 3–7% of advanced NSCLC mainly because of chromosomic rearrangements at the ALK locus. Next to its oncogenic function, ALK chimeric oncoprotein is a possible antigen for human immune system. The prognostic value of natural anti-ALK immunogenicity remains poorly explored in ALK + NSCLC. We hereby report preliminary results of a plasmatic anti-ALK a-abs titration assessment in a cohort of ALK + NSCLC pts.

Objective

To evaluate the prevalence of pre-existing circulating anti-ALK a-abs in ALK + NSCLC pts. Key secondary objectives are the assessment of anti-ALK a-abs prognostic value and association with brain metastases (BM).

Design

This monocentric case series included 60 ALK + NSCLC pts progressing on any anti-ALK TKIs between October 2015 and February 2021 at Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus. Fifty-six plasma samples were analyzed through a semiquantitative immunocytochemical technique. Plasma samples were obtained from two prospective studies approved by our Institutional Review Board: the MATCH-R trial (NCT02517892) and the MSN trial (RECF1256).

Participants

We included pts diagnosed with unresectable stage III or IV NSCLC, either by contemporaneous or historical biopsy. ALK-rearrangement was identified by FISH, IHC or NGS. Pts were aged more than 18-year-old and had previously signed informed consent for one of the studies. Pts had received at least one anti-ALK-TKI during the disease history. Pts were not eligible if they had been diagnosed with a second cancer.

Main outcomes and measures

The prevalence of plasmatic anti-ALK a-abs titer was reported as percentage. Progression-free survival, overall survival, and time to BM were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier methods.

Results

We found an anti-ALK a-abs titer in 5 (9 %) pts. anti-ALK a-abs did not contribute to prolongation of survival. Although not significant, there was a trend towards protection against BM in the presence of anti-ALK a-abs.

Conclusions and relevance

Because ALK fusion proteins are exclusively produced intracellularly, not all ALK autoantibodies may have direct anti-tumor impact with favorable prognostic value. This is the first investigation to explore the impact of circulating anti-ALK a-abs on BM. Prospective studies with longer follow-up are warranted to further explore the impact of anti-ALK a-abs on BM.

Keywords: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase, ALK, Lung cancer, NSCLC, Circulating antibodies, Immunogenicity, Humoral response, Brain metastases

1. Introduction

Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the most common type among Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [1]. The last 20 years have seen a paradigm change in precision treatment for NSCLC owing to the rapid development of high-throughput genome sequencing technologies [2,3]. About half of patients (pts) with advanced non-squamous NSCLC have an oncogene-addicted disease for which there is a corresponding therapy inside a clinical trial or an authorized indication [4]. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) can target the chromosomal rearrangement of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene, detected in approximately 3–7% of individuals with advanced NSCLC [5]. ALK encodes a classical transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor that belongs to the insulin receptor superfamily [[6], [7], [8]]. Upon deregulation, ALK can activate intracellular signaling pathways (Fig. 1). Patients with ALK-rearranged (ALK+) NSCLC tend to be younger (median age of 51 years), never-light smokers, and present with adenocarcinoma histology. Pleural, pericardial and brain metastases (BM) are common at presentation [9,10]. Brain is also the most common site of progression, occurring in 46 % of cases without systemic progression and 85 % of ALK-positive patients treated with the first generation ALK inhibitor crizotinib [10]. Compared to crizotinib, second and third-generation ALK-TKIs are more adept at penetrating the blood-brain barrier, thus preventing intracranial progression [11]. ALK + NSCLC is a heterogeneous disease with differential sensitivity and response duration to anti-ALK TKI exposure. Although resistance invariably occurs [12,13], some individuals have a slow-moving illness [14] that may benefit from prolonged use of the same ALK TKI combined with locoregional ablative therapy at the time of oligo-progression [[15], [16], [17]]. The variety of TKIs available for ALK + NSCLC is continually increasing [18]. However, not all patients may benefit from the same sequencing algorithm [19]; thus, uncovering prognostic and predictive biomarkers towards a more tailored pathway of care represents an unmet medical need. ALK is an outstanding tumor antigen owing to its high specificity, robust immunogenicity, essential role in tumor maintenance, and physiological expression limited to the central nervous system (CNS) [20]. In young adults with anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), anti-ALK antibodies (abs) have proven useful as surrogates for the presence and intensity of an adaptive B- and T-cell response against abnormal production of the NPM-ALK fusion oncoprotein. Abs against ALK, as well as cytotoxic T-cell and CD4 T-helper responses to ALK, have been seen in pts with ALK-positive ALCLs at both diagnosis and remission [21].

Fig. 1.

ALK chimeric protein and its signaling network.

Anti-ALK Ab titers are inversely correlated with the risk of relapse in patients with advanced pediatric ALK-positive ALCL pts [22]. As demonstrated in children and adolescents with ALK + ALCL, ALK may be intrinsically immunogenic. Tumor-associated abs in ALK-rearranged NSCLC may be involved in the elimination phase of immune surveillance, and anti-ALK abs have been reported in 17–61 % of ALK-rearranged NSCLC [23,24]. Because of new data supporting the use of vaccines in humans with ALK-rearranged NSCLC as an additional therapeutic strategy to boost response rates and length of response in combination with TKIs or immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) [25], the natural immunogenic potential of ALK is now calling for deeper insights.

Despite preliminary evidence, the prognostic value of anti-ALK abs has been poorly explored in patients with ALK + NSCLC. Therefore, we provide preliminary findings of a plasma anti-ALK autoantibodies (a-abs) titration assessment in a case series of ALK + NSCLC at the Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus. As research on predictive biomarkers able to predict cancer propensity for metastatic brain involvement is a challenge in lung cancer care, we also tried to explore the natural immunogenicity effect of anti-ALK a-abs on BM. We hypothesized that the innate presence of anti-ALK a-abs would persist during the progressive disease of any ALK-TKI.

2. Methods

2.1. Antibody titration

The titer of anti-NPM-ALK Abs found in the plasma of pts was defined by indirect immunostaining using NPM-ALK ectopically expressing the COS-1 cell line. These adherent cells are non-human monkey kidney fibroblast-like cells, suitable for transient transfection of the NPM-ALK expression vector (pcDNA3.1 host plasmid) using the FuGENE transfection reagent (Roche). Transiently expressing NPM-ALK cells (considering at least 20 % transfected cells, controlled by cytometry using fluorochrome-conjugated NPM-ALK antibody) were fixed using acetone after cytospin centrifugation on a slide. The titration experiment consisted of the incubation of ALK-expressing cells with plasma samples from each patient (100 μL of each dilution indicated in Table 1). anti-ALK a-abs, whether present in the patient's plasma, hybridized on the ALK fusion protein. A secondary antibody coupled with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and specific human IgG was added to reveal the ag-ab complex.

Table 1.

Plasma dilution adopted in the analytical phase.

| Dilution | PBS (μL) | Plasma (μL) |

|---|---|---|

| 1:50 test sample | 147 | 3 |

| 1:100 test sample | 198 | 2 |

| 1:250 test sample | 498 | 2 |

| 1:750 test sample | 500 | 250 (d1:250) |

| 1:2250 test sample | 500 | 250 (d1:750) |

| 1:6750 test sample | 500 | 250 (d1:2250) |

| 1:20250 test sample | 500 | 250 (d1:6750) |

| 1:60750 test sample | 500 | 250 (d1:20250) |

NPM-ALK transfectants enabled the detection of a-abs that recognize epitopes present in the intracytoplasmic region of ALK (present in all ALK fusion proteins). Plasmatic pre-titration (dilutions 1:50 and 1:100) confirmed the presence of specific NPM-ALK abs (Table 1).

3. Results’ interpretation

Hematoxylin-stained nuclei (nuclear chromatin) were dark blue, whereas the cytoplasm appeared light blue. Negative controls were used as the references. The HRP-DAB reaction produced a brown precipitate localized in the cytoplasm of COS-1 cells expressing the NPM-ALK protein. Plasma without evidence of antibodies at 1:100 (absence of cell membrane staining) was considered negative. The cut-off for a positive result was taken as the highest dilution before the staining of ALK transfectants was no longer visible by two independent observers.

3.1. Study population

This was a monocentric case series. Between October 2015 and February 2021, a total of 60 blood samples from patients diagnosed with ALK-rearranged NSCLC and progressing on first-generation, second-generation, or third-generation ALK-TKIs were available for analysis at Gustave Roussy.

All patients were aged >18 years at the time of plasma collection. We obtained plasma samples from patients who had signed informed consent for one of the two studies approved at our institution by the institutional ethics committee of the primary investigator: the MATCH-R trial (NCT02517892) and the MSN trial (RECF1256). Biological material collection was approved by an independent ethics committee, and both studies were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice, and applicable regulatory requirements.

All patients in the present study were diagnosed with NSCLC either by contemporaneous or historical biopsy and were not deemed eligible if they had a second malignancy. ALK rearrangement was confirmed in 100 % of the samples by at least one of the following detection techniques: FISH, IHC, or targeted NGS (Ion Torrent PGM, ThermoFisher Scientific).

3.2. Definition of variables

We described the patient demographics and clinicopathological features: age, sex, performance status, tumor histologic type, stage at diagnosis (according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Commission on Cancer TNM staging system for NSCLC), number of metastatic sites, LDH at baseline, presence of central nervous system involvement, number of ALK-TKIs received, and treatment types other than ALK-TKIs). Clinical progression events included RECIST progression events from the medical record abstraction. Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were collected from medical records. The clinicopathological data of patients were matched with next-generation sequencing (NGS) genomic data from two precision medicine protocols available at our Institution, the MATCH-R protocol (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02517892) and STARTRK-2 protocols (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02568267), providing molecular characterization of the tumor at disease progression with different ALK-TKIs.

3.3. Statistical analysis

Qualitative data are expressed as numbers and percentages, and quantitative data are expressed as medians and ranges. Progression-Free Survival (PFS), Overall Survival (OS), and time to Brain Metastases (TTBM) were estimated using Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves. PFS, OS, and ttBM with 95 % CI were reported for the Ab-positive and Abs negative subgroups. Differences in PFS, OS, and TTBM between the two subgroups were compared using the log-rank test. If no event occurred, the patients were censored at the date of the last follow-up. P values were two-sided and considered statistically significant at P ≤ 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 2022.07.2. The data were updated on October 1, 2022.

4. Results

4.1. Study population

Among 60 patients, 56 (93.3 %) were suitable for ab titration by a semiquantitative immunocytochemical technique, with plasma of patients used as source of anti-ALK primary abs.

Plasma samples were collected and analyzed for 56 participants involved in the research study. 43 of all samples (76.8 %) were not collected at baseline, but at disease progression on any ALK-TKIs. For five cases (9 %), this information was not available. The baseline characteristics of the 56 patients are summarized in Table 2. According to the NGS study, 23/56 patients (41 %) showed co-molecular abnormalities, with the most common being TP53 gene mutations, which were detected in 17.9 % (10/56) of pts. The frequencies of other concomitant mutations was as follows: 10.7 % for CDKN2A/B loss (6/65), 7.1 % for PI3KCA (4/56). On-target ALK mutations were detected in 16 % (9/56) of the patients. Overall, in our cohort, the PFS on the first ALK-TKI was 20.3 months (2.8–79.5) and the OS was 98.0 months (9.7–165.7).

Table 2.

Patients’ characteristics (n = 56).

| Category | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Women | 29 (51.8) |

| Age (years), median [range] | 49.6 [23–73] |

| Smoking status | |

| Current or former | 24 (42.9) |

| Non-smoker | 26 (46.4) |

| Not applicable | 5 (8.9) |

| Histology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 56 (100) |

| Stage | |

| Locally advanced | 7 (12.5) |

| Metastatic | 49 (87.5) |

| Number of metastatic sites | |

| 1 | 17 (30.4) |

| ≥ 2 | 39 (69.6) |

| Brain Metastasis (BM) | 14 (25) |

| N. Prior treatment lines | n (%) |

| Average | 2.4 (1–8) |

| ≤ 2 lines of therapy | 33 (59) |

| > 2 lines of therapy | 23 (41) |

| Chemotherapy first | 31 (55.4) |

| ALK-TKI first | 25 (44.6) |

| TKI at the time of plasma collection | |

| Crizotinib | 17 (30.3) |

| Lorlatinib | 16 (28.6) |

| Ceritinib | 13 (23.2) |

| Alectinib | 3 (5.4) |

| Other | 7 (12.5) |

4.2. Clinical relevance of anti-ALK autoantibodies (a-abs)

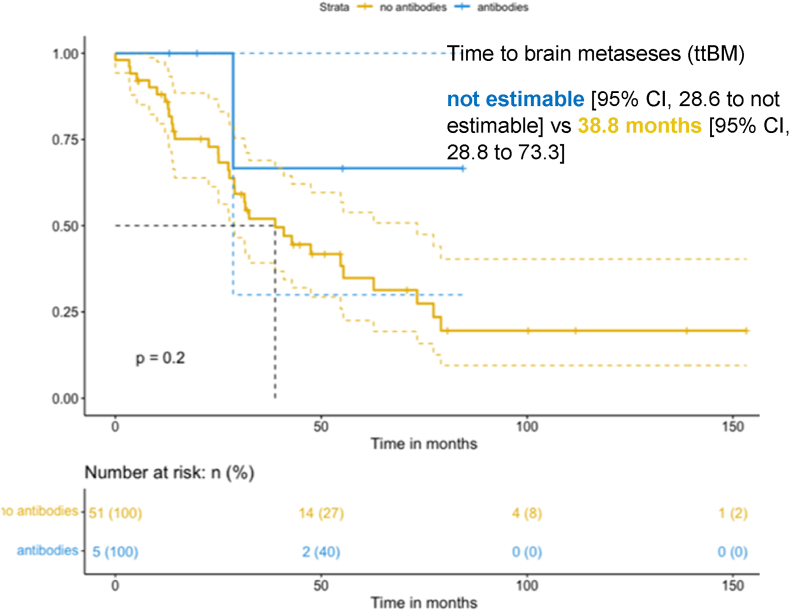

Anti-ALK a-abs were detected in 5/56 (9 %) patients with ALK-rearranged NSCLC (Table 3), (eFig. 1 in the Supplement). When considering clinical characteristics, including age, smoking status, and number of metastatic sites, no significant difference was found according to anti-ALK a-abs status. The global median follow-up was 88.7 (76.2–101.2) months. No significant difference in OS emerged between the group with antibodies (anti-ALK ab+) [mOS 40.2 months; 95 % CI, 19.9 to not estimable] and with no antibodies (anti-ALK ab-) [mOS 153.3 months; 95 % CI, 74.4 to not estimable]; (p = 0.062, eFig. 2 in the Supplement). Anti-ALK Abs did not prolong PFS. mPFS was 8.71 months for the anti ALK ab + [95 % CI, 4.57 to not estimable], and 13.75 months for the anti ALK ab-group [95 % CI, 11.28 to 26.2]; (p = 0.021, eFig. 3 in the Supplement). No patients in the anti ALK ab + group presented BM at baseline, while 14 patients (25 %) in the anti ALK ab-group had BM at the time of diagnosis. Four (80 %) patients in the anti ALK ab + group did not develop BM during their cancer history, whereas 37 (72,5 %) in the anti ALK ab-group did, with a median time of brain progression of 21 months. ttBM was 38.8 months [95 % CI, 28.8 to 73.3] in the anti ALK ab-group vs. not estimable [95 % CI, 28.6 to not estimable] in anti ALK ab + group (p = 0.2) (Fig. 2). Co-mutations were analyzed through targeted NGS using a customized panel covering 82 cancer genes (Ion Torrent PGM, Thermo Fisher Scientific). On-target ALK mutations were found in 3/5(60 %) patients and in 10/51 (19,6 %) patients in the anti ALK ab+ and anti ALK ab-groups, respectively. The difference between the groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.4).

Table 3.

Anti ALK ab + patient's characteristics (n = 5).

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | 70079 | 84396 | 117083 | 1105 | 1238 |

| Titer | +1:100 | +1:250 | +1:2250 | +1:50 | +1:750 |

| Histology | adeno | adeno | Adeno | adeno | adeno |

| ALK+ | IHC | IHC/FISH | IHC | IHC/FISH | IHC |

| Sex | male | male | female | male | Female |

| Smoking history | Former 25 P/Y |

Former 1 P/Y |

no | Former 40 P/Y |

Former 15 P/Y |

| Age at diagnosis | 58 | 23 | 36 | 69 | 43 |

| Stage at diagnosis | IV | IV | IV | IIIB | IIIC |

| BM baseline/PD | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/1 |

| PC after diagnosis (m) | 30.7 | 19.5 | 31.3 | 13.5 | 6.0 |

| 1st line ALK- TKI | crizotinib | crizotinib | crizotinib | crizotinib | crizotinib |

| PFS1 (m) | 3.4 | 14.5 | 8.7 | 9.3 | 4.5 |

| Brain PD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| OS status | Alive | Death | Death | Death | Death |

| OS (m) | 87.3 | 19.9 | 55.4 | 14.2 | 40.3 |

| Co-molecular alterations | NA | ALK F1174N, PIK3CB |

ALK G1202R, ROS1 T1987K |

ALK G1269A, ALK F1174L, PIK3CB | TP53 |

BM = brain metastases; PC = plasma collection; (m) = months; PFS1 = progression free survival on 1st ALK-TKI; OS = overall survival.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves of time to brain metastases (ttBM) in anti ALK ab + group (antibodies) and anti ALK ab-group (no antibodies).

5. Discussion

Recent data suggests that ALK-rearrangement is important for immunological regulation [23]. Aberrant ALK protein expression could represent a potential antigen for the immune system, as has been highlighted for ALCL [21,22,[26], [27], [28]]. Even though anti-PD-(L)1 abs have transformed the treatment landscape of advanced NSCLC, ICIs alone don't yield meaningful benefit in ALK + NSCLC [29,30] and the concept that immunotherapy may be beneficial for certain ALK + NSCLC is mainly supported by case studies [31,32]. It is currently unclear whether anti-ALK a-abs might pinpoint a patient subgroup that responds better to ICIs. Nevertheless, a vaccine-based strategy is being developed for ALK-rearranged NSCLC in light of the findings supporting ALK's immunologically antigenic significance of ALK [25]. A significant inverse correlation between the titers of anti-ALK a-abs and the presence of NPM-ALK transcripts in peripheral blood has been reported in patients with hematologic ALCL. Data on this correlation are lacking in patients with NSCLC. Along with the wide implementation of liquid biopsy in clinical practice, exploration of this possible correlation could result in high scientific interest.

In our series of ALK-rearranged NSCLC, anti-ALK a-abs were observed in 9 % of patients, a lower frequency compared to ALCL patients, with a frequency of up 96 %. The prevalence of anti-ALK a-abs titers in our series was also lower than the one reported by Awad et al. (17 % of NSCLC patients) [23]. Indeed, the authors adopted a different methodology based on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), demonstrating a good correlation compared to the standard immunocytochemical technique.

Anti-ALK a-abs did not prolong PFS or OS. Although the impact of treatment exposure on the anti-ALK a-abs titer still needs elucidation, as the tumor progresses, the net effects of the cancer-specific immune response might decrease and, finally, be overwhelmed by cancer-related immunosuppression and tumor growth kinetics. In addition, with the emergence of acquired resistance to ALK-TKI, the tumor microenvironment (TME) gains immunosuppressive features, such as the restoration of myeloid-derived suppressive cells (MDSCs) and regulatory T cells (Tregs), impaired functions of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), decreased antigen presentation, increased levels of interferon gamma (IFN-γ), and increased expression of immune checkpoint molecules, such as PD-L1 [33]. Deep analysis of the immune infiltrates of the tumors revealed that despite the upregulation of PD-L1 in cancer cells, PD-1-and granzyme B-expressing CD8+ T cells did not increase, suggesting that these T cells may not be functional [34]. Therefore, anti-ALK antibodies present in the bloodstream may be insufficient to counteract the negative effect of T cell exhaustion in ALK-rearranged NSCLC progressing over ALK-TKI exposure [35]. In our study, only one (20 %) patient displayed a high positivity titer, potentially explaining the absence of prognostic value of circulating anti-ALK a-abs in our experience. In addition, among the five patients who tested positive for anti-ALK a-abs, two of them (40 %) had already received chemotherapy and one (20 %) had already received radiotherapy at the time of blood sample collection. Notably, the sudden and systemic release of numerous dying tumor cells resulting from chemotherapy may have deleterious consequences on tumor-specific immune responses. A direct correlation between the number of antigens expressed in the periphery, the degree of T-cell proliferation, and the number of tolerogenic antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in the draining lymph nodes has been described.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the possible correlation between natural ALK immunogenicity and BM development in NSCLC. A trend towards protection against central nervous system involvement was found in the group with anti-ALK a-abs in our series, suggesting that the natural immunogenicity of ALK + NSCLC may play a significant role in delaying BM emergence in certain ALK-rearranged patients. Prospective studies involving pretreatment anti-ALK a-abs titrations and prolonged follow-up are needed to investigate the immunogenicity of anti-ALK a-abs against BM. To assess the real impact of the anti-ALK natural immune response in preventing the emergence of resistance and the development of BM in selected ALK + NSCLC patients, longitudinal analysis of circulating anti-ALK a-abs from long responders and oligo-progressors to first-line next-generation ALK-TKIs (e.g., alectinib [36], lorlatinib [37], NVL-655 [38]) should be pursued. The identification of a persistent natural immune response in the presence of progressive disease may be the most notable clinical application in this regard, allowing future studies to investigate the true predictive potential of anti-ALK a-abs with novel therapeutic approaches (e.g., future immunotherapeutic options, including ALK vaccines and chimeric antigens receptor cells designed to allow modified T lymphocytes to detect and destroy tumor cells expressing tumor-specific antigen [39]). This knowledge may prove essential, particularly for individuals whose sensitivity to all authorized ALK-TKIs has been lost because of compound ALK mutations and the activation of alternative molecular pathways.

To summarize, the concept of circulating anti-ALK abs primarily pertains to the potential utility of these antibodies in blood-based assays, providing a non-invasive method to track the prognostic behavior of ALK-positive NSCLC. Circulating anti-ALK antibodies in NSCLC holds promise as a non-invasive prognostic marker to help in the early identification of patients’ who may derive prolonged clinical benefit with ALK inhibitors.

6. Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the technique adopted for ab titration is dependent on the observer's evaluation of the immunostaining. To overcome this limitation, a second lecture by an expert biologist was conducted to validate our results. Second, the retrospective nature and limited sample size make the results inconclusive. These limitations support the need for larger studies with longer follow-up periods to explore the prognostic role of anti-ALK a-abs and the predictive value of novel ALK-TKIs. Third, our cohort showed wide treatment heterogeneity and most samples were collected after treatment exposure. To overcome this limitation, a prospective study enrolling a more homogeneous and less-treated population is encouraged. Finally, no randomized clinical trials have assessed the predictive value of EML4-ALK variants in response to ALK inhibitors. This information was not available for most patients in our cohort; hence, further research should be encouraged to assess the impact of the ALK variant on natural immunogenicity.

7. Conclusions and future perspectives

Since ALK-rearranged lymphoma patients have been shown to have antibodies against ALK, as well as cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and CD4+ T helper effectors to ALK epitopes, ALK is naturally immunogenic in NSCLC. The dynamic nature of the interaction between the immune system and tumor is one of the main aspects of cancer biology that must be considered in the development of new therapeutic strategies. In this regard, ALK + NSCLC is an attractive option. Anti-ALK a-abs were found in 9 % of pretreated patients using an immunocytochemical technique. The presence of plasma anti-ALK a-abs did not improve prognosis in our case series. Since ALK fusion proteins are only intracellular, ALK a-abs may not have a direct anti-tumor effect. Longitudinal examination of patients with prolonged disease control on first line ALK-TKI may shed light on the interaction between the natural immune response and CD8+ T cell-mediated cytotoxicity as a significant determinant of late resistance in ALK-rearranged NSCLC patients. This is the first study investigating the potential relationship between the development of brain metastases in NSCLC and the inherent natural immunological response to the ALK chimeric oncoprotein. Prospective trials involving pretreatment, anti-ALK a-abs titration, and prolonged follow-up are necessary to investigate the effect of anti-ALK a-abs immunogenicity against brain metastases.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval/patient's consent was necessary for this study.

Author contributions

Study design: CP, JBM and BB.

Methodology & statistics: CP, HL, VV, CQ, FGD.

Writing – Original Draft: CP, BB, FB.

Writing – Review & Editing before submission: all co-authors.

Author contributions.

CP, BB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Original draft preparation and editing, Investigation, Data curation.

CP, JBM, FDG, HL, CQ, MA: Investigation, Methodology and Statistics.

FB, BB: Investigation, Data curation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Visualization.

All co-authors: Review & Editing before submission, Validation.

Funding statement

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Claudia Parisi, CP (Claudia.PARISI@gustaveroussy.fr): no disclosures.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Statement of translational relevance

The prognostic relevance of natural anti-ALK immunogenicity in patients (pts) with anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains uncertain.

Our series revealed evidence of a natural immunological response to ALK chimeric oncoproteins, supported by the existence of circulating anti-ALK autoantibodies (a-abs) in 9 % (5/56) of patients.

In our experience, no improved survival was observed in patients with circulating anti-ALK a-abs. This evidence suggests that circulating ALK a-abs may not have direct anti-tumor effects since ALK chimeric oncoproteins are only expressed intracellularly. Although not statistically significant, there was a trend towards protection against brain metastases (BM) in patients with anti-ALK a-abs. ALK + NSCLC represents an opportunity to empower knowledge of the anti-tumoral immune response in an oncogene-driven disease. With a novel effective therapeutic approach at the horizon, further prospective research is warranted to exploit the interplay between persistent natural humoral response and ALK-specific T cell response at progression on ALK-TKIs for NSCLC to predict metastatic brain involvement propensity.

Declaration of competing interest

JCS: received consultancy fees from Relay Therapeutics; was an employee of AstraZeneca 2017–2019; has shares in AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Gritstone; he is a full-time employee of Amgen since August 2021. Personal fees outside of this work: Astex, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Blend Therapeutics, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Clovis, Eli Lilly, Gammamabs, Merus, Mission Therapeutics, Pfizer, Pharmamar, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, Symphogen, Tarveda; Gritstone; AstraZeneca.

BB: Contracted/supported research grants: Abbvie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Blueprint Medicines, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Cristal Therapeutics, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, GSK, Ignyta, IPSEN, Inivata, Janssen, Merck KGaA, MSD, Nektar, Onxeo, OSE immunotherapeutics, Pfizer, Pharma Mar, Roche-Genentech, Sanofi, Servier, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, Tiziana Pharma, Tolero Pharmaceuticals.

The other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest related to this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlb.2024.100164.

Contributor Information

Claudia Parisi, Email: parisiclaudia168@gmail.com.

José Carlos Benitez, Email: Josecarlos.BENITEZ-MONTANEZ@gustaveroussy.fr.

Hélène Lecourt, Email: Helene.LECOURT@gustaveroussy.fr.

Filippo Gustavo dall’Olio, Email: Filippogustavo.DALL-OLIO@gustaveroussy.fr.

Mihaela Aldea, Email: Mihaela.ALDEA@gustaveroussy.fr.

Felix Blanc-Durand, Email: Felix.BLANC-DURAND@gustaveroussy.fr.

Véronique Vergé, Email: Veronique.VERGE@gustaveroussy.fr.

Cyril Quivoron, Email: Cyril.QUIVORON@gustaveroussy.fr.

Charles Naltet, Email: Charles.NALTET@gustaveroussy.fr.

Pamela Abdayem, Email: Pamela.ABDAYEM@gustaveroussy.fr.

Pernelle Lavaud, Email: Pernelle.LAVAUD@gustaveroussy.fr.

Maria Rosa Ghigna, Email: Mariarosa.GHIGNA@gustaveroussy.fr.

Luc Friboulet, Email: Luc.FRIBOULET@gustaveroussy.fr.

Yohann Loriot, Email: Yohann.LORIOT@gustaveroussy.fr.

Stéphane De Botton, Email: Stephane.DEBOTTON@gustaveroussy.fr.

Vincent Ribrag, Email: Vincent.RIBRAG@gustaveroussy.fr.

Andrea Ardizzoni, Email: andrea.ardizzoni@aosp.bo.it.

David Planchard, Email: David.PLANCHARD@gustaveroussy.fr.

Jean-Charles Soria, Email: Jsoria01@amgen.com.

Fabrice Barlesi, Email: Fabrice.BARLESI@gustaveroussy.fr.

Benjamin Besse, Email: Benjamin.BESSE@gustaveroussy.fr.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Califf R.M. Biomarker definitions and their applications. Exp Biol Med. 2018;243:213–221. doi: 10.1177/1535370217750088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:543–550. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zehir A., Benayed R., Shah R.H., Syed A., Middha S., Kim H.R., et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med. 2017;23:703–713. doi: 10.1038/nm.4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barlesi F., Mazieres J., Merlio J.-P., Debieuvre D., Mosser J., Lena H., et al. Routine molecular profiling of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a 1-year nationwide programme of the French Cooperative Thoracic Intergroup (IFCT) Lancet (London, England) 2016;387:1415–1426. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwak E.L., Bang Y.-J., Camidge D.R., Shaw A.T., Solomon B., Maki R.G., et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiarle R., Voena C., Ambrogio C., Piva R., Inghirami G. The anaplastic lymphoma kinase in the pathogenesis of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:11–23. doi: 10.1038/nrc2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallberg B., Palmer R.H. Mechanistic insight into ALK receptor tyrosine kinase in human cancer biology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:685–700. doi: 10.1038/nrc3580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallberg B., Palmer R.H. The role of the ALK receptor in cancer biology. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2016;27(Suppl 3):iii4–15. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaw A.T., Yeap B.Y., Mino-Kenudson M., Digumarthy S.R., Costa D.B., Heist R.S., et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non–small-cell lung cancer who harbor EML4-ALK. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4247–4253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toyokawa G., Seto T., Takenoyama M., Ichinose Y. Insights into brain metastasis in patients with ALK+ lung cancer: is the brain truly a sanctuary? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2015;34:797–805. doi: 10.1007/s10555-015-9592-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishino M., Soejima K., Mitsudomi T. Brain metastases in oncogene-driven non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019;8:S298–S307. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2019.05.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw A.T., Solomon B.J., Besse B., Bauer T.M., Lin C.-C., Soo R.A., et al. ALK resistance mutations and efficacy of lorlatinib in advanced anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1370–1379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cognigni V., Pecci F., Lupi A., Pinterpe G., De Filippis C., Felicetti C., et al. The landscape of ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer: a comprehensive Review of clinicopathologic, genomic characteristics, and therapeutic perspectives. Cancers. 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/cancers14194765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto K., Toyokawa G., Kozuma Y., Shoji F., Yamazaki K., Takeo S. ALK-positive lung cancer in a patient with recurrent brain metastases and meningeal dissemination who achieved long-term survival of more than seven years with sequential treatment of five ALK-inhibitors: a case report. Thorac Cancer. 2021;12:1761–1764. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez D.R., Tang C., Zhang J., Blumenschein G.R.J., Hernandez M., Lee J.J., et al. Local consolidative therapy vs. Maintenance therapy or observation for patients with oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: long-term results of a multi-institutional, phase II, randomized study. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1558–1565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai Y., Wei Q., Schwager C., Moustafa M., Zhou C., Lipson K.E., et al. Synergistic effects of crizotinib and radiotherapy in experimental EML4-ALK fusion positive lung cancer. Radiother Oncol J Eur Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 2015;114:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hubbeling H., Choudhury N., Flynn J., Zhang Z., Falcon C., Rusch V.W., et al. Outcomes with local therapy and tyrosine kinase inhibition in patients with ALK/ROS1/RET-Rearranged lung cancers. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022 doi: 10.1200/PO.22.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider J.L., Lin J.J., Shaw A.T. ALK-positive lung cancer: a moving target. Nat Cancer. 2023;4:330–343. doi: 10.1038/s43018-023-00515-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elsayed M., Christopoulos P. Therapeutic sequencing in ALK(+) NSCLC. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14 doi: 10.3390/ph14020080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vernersson E., Khoo N.K.S., Henriksson M.L., Roos G., Palmer R.H., Hallberg B. Characterization of the expression of the ALK receptor tyrosine kinase in mice. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006;6:448–461. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stadler S., Singh V.K., Knörr F., Damm-Welk C., Woessmann W. Immune response against ALK in children with ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Cancers. 2018;10 doi: 10.3390/cancers10040114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ait-Tahar K., Damm-Welk C., Burkhardt B., Zimmermann M., Klapper W., Reiter A., et al. Correlation of the autoantibody response to the ALK oncoantigen in pediatric anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma with tumor dissemination and relapse risk. Blood. 2010;115:3314–3319. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-251892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Awad M.M., Mastini C., Blasco R.B., Mologni L., Voena C., Mussolin L., et al. Epitope mapping of spontaneous autoantibodies to anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:92265–92274. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damm-Welk C., Siddiqi F., Fischer M., Hero B., Narayanan V., Camidge D.R., et al. Anti-ALK antibodies in patients with ALK-positive malignancies not expressing NPM-ALK. J Cancer. 2016;7:1383–1387. doi: 10.7150/jca.15238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mota I., Patrucco E., Mastini C., Mahadevan N.R., Thai T.C., Bergaggio E., et al. ALK peptide vaccination restores the immunogenicity of ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Cancer. 2023;4:1016–1035. doi: 10.1038/s43018-023-00591-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pulford K., Roberton H.M., Jones M. Antibody techniques used in the study of anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive ALCL. Methods Mol Med. 2005;115:271–294. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-936-2:271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pulford K., Lamant L., Morris S.W., Butler L.H., Wood K.M., Stroud D., et al. Detection of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and nucleolar protein nucleophosmin (NPM)-ALK proteins in normal and neoplastic cells with the monoclonal antibody ALK1. Blood. 1997;89:1394–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mussolin L., Pillon M., Zimmermann M., Carraro E., Basso G., Knoerr F., et al. Course of anti-ALK antibody titres during chemotherapy in children with anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2018;182:733–735. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gavralidis A., Gainor J.F. Immunotherapy in EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive lung cancer: implications for oncogene-driven lung cancer. Cancer J. 2020;26:517–524. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazieres J., Drilon A., Lusque A., Mhanna L., Cortot A.B., Mezquita L., et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with advanced lung cancer and oncogenic driver alterations: results from the IMMUNOTARGET registry. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2019;30:1321–1328. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.A vaccine to treat ALK+ lung cancer and prevent metastatic disease. Nat Cancer. 2023;4:933–934. doi: 10.1038/s43018-023-00592-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baldacci S., Grégoire V., Patrucco E., Chiarle R., Jamme P., Wasielewski E., et al. Complete and prolonged response to anti-PD1 therapy in an ALK rearranged lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2020;146:366–369. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang L., Liu J. Immunological effect of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on the tumor immune environment in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 2022;23:165. doi: 10.3892/ol.2022.13285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pyo K.-H., Lim S.M., Park C.-W., Jo H.-N., Kim J.H., Yun M.-R., et al. Comprehensive analyses of immunodynamics and immunoreactivity in response to treatment in <em>ALK</em>-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobold S., Luetkens T., Cao Y., Bokemeyer C., Atanackovic D. Prognostic and diagnostic value of spontaneous tumor-related antibodies. Clin Dev Immunol. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/721531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters S., Camidge D.R., Shaw A.T., Gadgeel S., Ahn J.S., Kim D.-W., et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:829–838. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaw A.T., Bauer T.M., de Marinis F., Felip E., Goto Y., Liu G., et al. First-line lorlatinib or crizotinib in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2018–2029. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2027187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nuvalent reports preliminary phase 1 clinical data from ALKOVE-1 trial that support best-in-class potential of NVL-655 for patients with ALK-positive NSCLC. News Release. Nuvalent; October 13, 2023. p. 2023. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bergaggio E., Tai W.-T., Aroldi A., Mecca C., Landoni E., Nüesch M., et al. ALK inhibitors increase ALK expression and sensitize neuroblastoma cells to ALK.CAR-T cells. Cancer Cell. 2023;41:2100–2116.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.