Abstract

Background

Poor cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) is associated with a higher symptom burden and an increased prevalence of long-term treatment–related cardiovascular disease risk factors in cancer survivors. However, the magnitude of systemic therapy–related CRF impairment remains unclear.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of systemic anticancer treatment on CRF and identify physiological determinants underpinning CRF impairment.

Methods

A systematic literature search was performed in PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, SPORTDiscus, and the Cochrane Library. The primary endpoint was the change in CRF, measured by peak oxygen consumption (Vo2peak), from before to after systemic treatment. Secondary endpoints included post-treatment differences in Vo2peak between cancer survivors and noncancer control subjects, along with physiological determinants of Vo2peak. Two meta-regressions were conducted to examine the association between CRF and cardiac output and arteriovenous oxygen difference.

Results

A total of 44 studies were included, comprising 27 prospective trials (61%; n = 1,234 cancer survivors, median age 52.4 years) and 17 cross-sectional studies (39%; n = 1,372 cancer survivors, median age 54.0 years; n = 1,923 noncancer control subjects, median age 56.0 years). Systemic anticancer treatment was associated with a significant decrease in Vo2peak (weighted mean difference −2.13 mL·kg−1·min−1; 95% CI: −2.76 to −1.50 mL·kg−1·min−1). No significant differences were observed between patient subgroups (esophagogastric, breast, and colon or rectal cancers). At a median follow-up of 2 years (range: 6 weeks to 12 years) post-therapy, cancer survivors had a significantly lower Vo2peak (weighted mean difference −6.39 mL·kg−1·min−1; 95% CI: −7.60 to −5.18 mL·kg−1·min−1) compared with noncancer control subjects. Reduced arteriovenous oxygen difference was associated with lower Vo2peak (β = 2.55; 95% CI: 2.05-3.06; P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Systemic anticancer treatment leads to substantial and sustained impairments in CRF.

Key Words: alkylating therapy, anthracycline, cancer, cardiorespiratory fitness, peak oxygen consumption, physiological determinants, survivorship, systemic anticancer treatment, treatment, VO2 and exercise

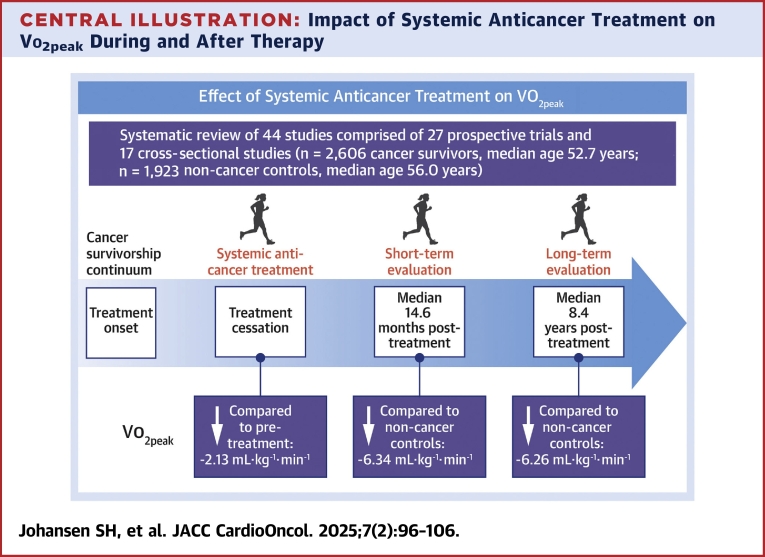

Central Illustration

Cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), measured by peak oxygen consumption (Vo2peak), provides an objective indicator of overall cardiovascular capacity.1 In patients with cancer, low Vo2peak is associated with a higher symptom burden2 and an increased prevalence of long-term treatment–related cardiovascular disease risk factors3 and is a strong, independent predictor of cancer, cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality.4,5 Findings from several studies suggest that systemic anticancer treatment can lead to significant acute and chronic reductions in Vo2peak.5, 6, 7 However, most existing studies have focused on breast cancer, lacked longitudinal assessments, or relied on estimated rather than directly measured Vo2peak. Thus, the broader effects of systemic anticancer therapies on Vo2peak remain inadequately understood.

Physiological determinants of Vo2peak include both central factors, such as reduced convective O2 transport, and peripheral factors, such as decreased diffusive O2 transport and oxidative capacity in skeletal muscle.8 Although O2 transport (eg, cardiac output) is often a limiting factor for Vo2peak in noncancer settings,9 anticancer treatments can cause both short- and long-term adverse effects that may create limitations at various points along the cardiopulmonary-muscle axis.10 There is a pressing need to characterize the pathophysiology of poor Vo2peak in patients with cancer to guide the development of targeted interventions.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to evaluate the effects of systemic anticancer treatment on Vo2peak in adults with cancer. Secondary objectives included comparing differences in Vo2peak between cancer survivors and noncancer control subjects in cross-sectional studies and evaluating physiological determinants of Vo2peak.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

A comprehensive literature search was conducted by a research informationist (K.M.) from database inception to January 20, 2023. The systematic literature review included searches in PubMed (National Library of Medicine), Embase, CINAHL, SPORTDiscus, and the Cochrane Library. The search strategy used terms related to systemic anticancer treatment, CRF, and CRF determinants (Supplemental Appendix 1). An updated search was conducted on January 17, 2024, to capture newly published trials.

Randomized (limited to nonintervention control groups) or nonrandomized trials, prospective cohort studies with pre- and post-treatment assessments, and cross-sectional studies with post-treatment assessments that included a noncancer control group for reference values were considered eligible if they met the following criteria: 1) included adult patients (>18 years of age) diagnosed with adult-onset cancer, regardless of stage, or adult survivors of any (childhood) cancer who had received systemic anticancer treatment (eg, chemotherapy, stem cell transplantation, endocrine agents, targeted or biological agents, and/or immune checkpoint inhibitors); and 2) directly measured Vo2peak (eg, using ergospirometry) in milliliters per kilogram per minute before and/or after systemic therapy. Studies reporting 1 or more physiological determinants of Vo2peak were included in a subgroup analysis. Cancer survivors were defined as individuals from the time of cancer diagnosis until the end of life.11 For cases that reported Vo2peak solely in absolute values (L/min), a request for additional data was sent to the corresponding author.

Exclusion criteria included studies that did not report group central tendencies and distributions; used submaximal and/or indirect Vo2peak tests; lacked a noncancer reference group for cross-sectional studies; or were abstracts, systematic reviews, protocols, duplicates, or not written in English. Studies were also excluded if there was no response to requests for additional data. To ensure transparency and adherence with reporting standards, this systematic review and meta-analysis was preregistered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42023361788) and prepared in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (Supplemental Appendix 2 and Supplemental Appendix 3).12

Study selection and assessment of risk for bias

Screening of potential studies involved evaluating titles, abstracts, and full texts according to predefined inclusion criteria by 2 independent assessors (S.H.J. and S.T.K.) using Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation). In cases of disagreement, a third assessor (T.S.N.) was consulted to reach consensus. Data extraction and assessment of risk for bias were carried out using a standardized data extraction template by a team of 4 independent reviewers (S.H.J., T.S.N., J.S.S.J., and G.A.), with the role of the second reviewer distributed among T.S.N., J.S.S.J., and G.A. Data were extracted from the primary reports and supplemental materials (Supplemental Tables 1 to 4, Supplemental Appendix 4 and 5).

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

All analyses were performed in R version 4.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) using RStudio version 2023.06.0 (Posit). A random-effects meta-analysis with inverse variance weighting was used to calculate the weighted mean difference (WMD) for Vo2peak, using the function metacont from the meta package. Standardized mean differences were calculated using Hedges’s g. Heterogeneity was calculated using both the I2 and τ2 statistics, as defined by Schwarzer et al13 (Supplemental Funnel plots, Supplemental Appendix 6, Supplemental Figures 1 and 2). Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots. Because of variability in reporting, participant age and time since treatment cessation were summarized as the study-level median (range) across studies.

Three a priori subgroup analyses were conducted to investigate the impact of treatment type, primary cancer site, and whether the effects differed on the basis of follow-up time. However, because of insufficient reporting, variability in treatment regimens, and small sample sizes, the analysis for treatment type was not feasible. Subgroup analyses were performed using mixed-effects meta-regression, with Vo2peak as the outcome, incorporating cancer type or follow-up time as predictors, using the function metareg from the metafor package.

For studies in which all relevant information was available (Vo2peak, cardiac output, and arteriovenous oxygen [a-vO2] difference), separate analyses were performed with cardiac output and a-vO2 difference as additional predictors, but these were not included simultaneously because of the limited number of studies. When a study’s SD was not reported, it was calculated from the CI or SE reported. The 95% CIs depicted for each study in the forest plot of this meta-analyses are based on the normal distribution and may differ slightly from those reported in the original studies. However, this variation does not affect the pooled results.

Long-term survivors were defined as individuals who had completed systemic therapy more than 5 years prior. Forest plots were used to display the results of the meta-analysis, including the mean difference for each study and the WMD with 95% CIs. For each subgroup analysis, a meta-regression was conducted, as described earlier, to evaluate potential differences between groups. These meta-analyses were performed similarly to standard regression, with the post-treatment value as the outcome, controlling for baseline and incorporating the factor of interest (diagnosis or long-term survivor status).

Results

A total of 5,126 records were identified, with 644 duplicates removed. This left 4,482 unique records for screening, 44 of which met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analyses (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart According to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Guidelines

Flowchart illustrating the study selection process following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, including the number of records identified, screened, and included.

Study and population characteristics

The 44 included studies spanned publication years from 1994 to 2023. Among these, 27 studies (61%) were prospective trials (Supplemental Appendix 7, Supplemental Table 5)14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 with pre- and post-treatment assessments, and 17 studies (39%) were cross-sectional (Supplemental Appendix 7, Supplemental Table 6), comparing post-treatment Vo2peak in cancer survivors with noncancer control subjects3,41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56 (Table 1). Of the included studies, 21 (48%) focused on breast cancer, and 40 (91%) primarily used chemotherapy as the treatment modality. Across all studies, there were 2,606 cancer survivors (median age 52.7 years; range: 19-72.5 years) and 1,923 noncancer control subjects (median age 56.0 years; range: 22-67 years). In the prospective trials (n = 1,234), the median treatment duration was 13 weeks (range: 7-27 weeks), though 29% of trials did not report treatment duration. Cross-sectional studies included 1,372 cancer survivors (median time post-treatment 2 years; range: 6 weeks-12 years) and 1,923 noncancer control subjects. Four trials3,44,49,54 (n = 114 cancer survivors, n = 50 noncancer control subjects) were included in the analysis of physiological determinants of Vo2peak.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Included Trials (N = 44)

| Study design | |

| Cross-sectional study | 17 (39) |

| Randomized controlled trial | 14 (32) |

| Prospective cohort study | 10 (23) |

| Nonrandomized controlled trial | 3 (7) |

| Region of origin | |

| Canada | 11 (25) |

| United States | 10 (23) |

| Australia | 6 (14) |

| United Kingdom | 6 (14) |

| Denmark | 2 (5) |

| France | 2 (5) |

| Brazil | 1 (2) |

| Egypt | 1 (2) |

| Germany | 1 (2) |

| Sweden | 1 (2) |

| Switzerland | 1 (2) |

| Taiwan | 1 (2) |

| the Netherlands | 1 (2) |

| Year of publication | |

| 1994-2010 | 4 (9) |

| 2010-2019 | 19 (43) |

| 2020-2023 | 21 (48) |

| Sample size | |

| <20 | 16 (36) |

| 21-50 | 18 (41) |

| >50 | 10 (23) |

| Total number of cancer survivors | 2,606 |

| Total number of noncancer control subjects | 1,923 |

| Sample size by diagnosis | |

| Mixed diagnosis | 1,154 (44) |

| Breast cancer | 622 (24) |

| Esophagogastric | 230 (9) |

| Leukemia/lymphoma | 372 (14) |

| Lung | 126 (5) |

| Colon/rectal | 60 (2) |

| Prostate | 26 (1) |

| Head and neck/CNS | 16 (1) |

| Age of cancer survivors, y | 52.7 (19-72.5) |

| Age of noncancer control subjects, y | 56.0 (22-67) |

| Cancer sitea | |

| Breast | 21 (48) |

| Mixed diagnosis | 6 (14) |

| Esophageal/gastric | 5 (11) |

| Colon/rectal | 3 (7) |

| Lung | 3 (7) |

| Leukemia/lymphoma | 4 (9) |

| Head and neck/CNS | 1 (2) |

| Prostate | 1 (2) |

| Systemic treatmentb | |

| Chemotherapy | 40 (91) |

| Targeted/biological agents | 7 (16) |

| Endocrine therapiesc | 3 (7) |

| Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation | 2 (5) |

| Regimens that could not be categorized | 1 (2) |

Values are n (%) or median (range).

CNS = central nervous system.

Studies may be counted in multiple categories because of subgroup analysis.

Studies may be counted in multiple categories because of multimodal regimens.

Studies with endocrine agents as the only systemic treatment received.

Assessments of risk for bias

Attrition and reporting bias were low in 12 (71%) and 14 (82%) of the 17 clinical trials, respectively (Supplemental Table 2). Among the cross-sectional studies, 3 (18%) achieved participation rates exceeding 50%, whereas 11 (65%) did not report participation rates (Supplemental Table 4, Q3). In the prospective cohort trials, loss to follow-up was <20% in 3 studies (30%) (Supplemental Table 3, Q9). The funnel plots showed relative symmetry, indicating low risk for publication bias in the included studies (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2).

Effect of systemic anticancer treatment on Vo2peak

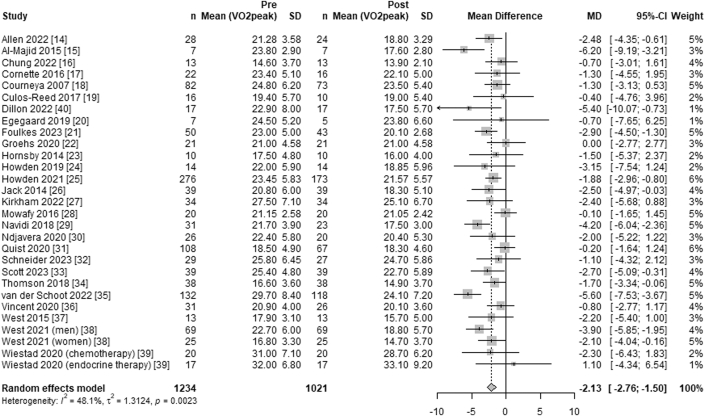

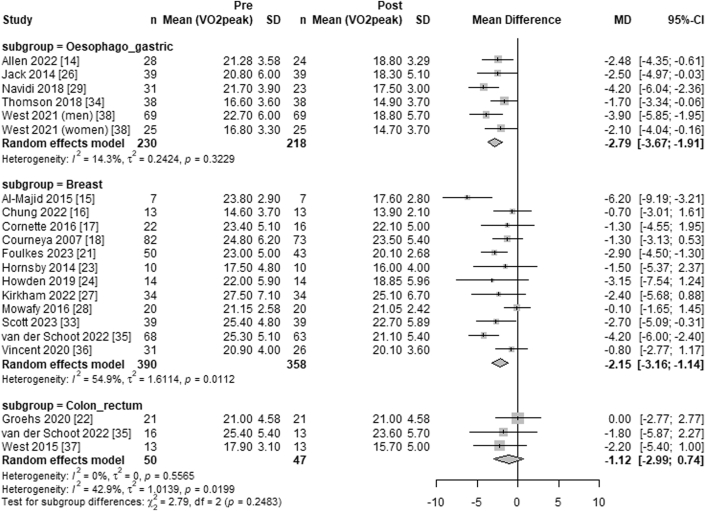

Overall, systemic anticancer treatment was associated with a significant decrease in Vo2peak (WMD −2.13 mL·kg−1·min−1; 95% CI: −2.76 to −1.50 mL·kg−1·min−1; I2 = 48%) from pre- to post-treatment (Figure 2). Subgroup analysis using meta-regression, with the colon or rectal cancer subgroup as the reference, showed no significant difference in the decline of Vo2peak between treatment for colon or rectal cancer (WMD −1.12 mL·kg−1·min−1; 95% CI: −2.99 to 0.74 mL·kg−1·min−1; I2 = 0%) and esophagogastric cancer (WMD −2.79 mL·kg−1·min−1; 95% CI: −3.67 to −1.91 mL·kg−1·min−1; I2 = 14%) (P = 0.46) or breast cancer (WMD −2.15 mL·kg−1·min−1; 95% CI: −3.16 to −1.14 mL·kg−1·min−1; I2 = 55%) (P = 0.059) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Forest Plot of the Effect of Systemic Anticancer Treatment on Vo2peak

Forest plot depicting the effects of systemic anticancer treatments on peak oxygen consumption (Vo2peak) in a meta-analysis of studies with pre- and post-treatment assessments. The summary estimate was calculated using a random-effects model, with the mean differences and corresponding 95% CIs. The overall summary effect is represented by a diamond.

Figure 3.

Forest Plot of the Effect of Systemic Anticancer Treatment on Vo2peak by Cancer Diagnosis

Forest plot illustrating the effects of systemic anticancer treatments on peak oxygen consumption (Vo2peak), stratified by cancer diagnosis subgroups. Summary estimates for each subgroup were calculated using a random-effects model, with mean differences and 95% CIs shown as bars. The overall effect within each subgroup is represented by the corresponding diamond.

Post-treatment Vo2peak in cancer survivors compared with noncancer control subjects

After a median of 2 years (range: 6 weeks to 12 years) post-therapy, Vo2peak was significantly lower in cancer survivors (n = 1,372; WMD −6.39 mL·kg−1·min−1; 95% CI: −7.60 to −5.18 mL·kg−1·min−1; I2 = 61%) compared with noncancer control subjects (n = 1,923 participants). The subgroup analysis revealed no differences in Vo2peak impairment between cancer survivors and noncancer control subjects in the short term (median time 14.6 months; range: 6 weeks-34 months post-treatment; WMD −6.34 mL·kg−1·min−1; 95% CI: −7.75 to −4.92 mL·kg−1·min−1; I2 = 5%) compared with the long term (median time 8.4 years; range: 7 to 12 years post-treatment; WMD −6.26 mL·kg−1·min−1; 95% CI: −8.25 to −4.28 mL·kg−1·min−1; I2 = 78%) (P = 0.068) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest Plot Comparing the Effects of Systemic Anticancer Treatments on Vo2peak Between Cancer Survivors and Noncancer Control Subjects

Forest plot comparing the effects of systemic anticancer treatments on peak oxygen consumption (Vo2peak) in cancer survivors vs noncancer control subjects. Summary estimates for each follow-up time subgroup were calculated using a random-effects model, with mean differences and 95% CIs shown as bars. Subgroup-level summary effects are represented by diamonds, with the overall effect displayed at the bottom.

Mechanisms underpinning impaired Vo2peak

The av-O2 difference was indirectly calculated as the ratio of Vo2peak to peak cardiac output across all trials, with cardiac output assessed using stress echography,44,54 impedance cardiography,3 and magnetic resonance imaging.49 A lower av-O2 difference was significantly associated with a lower Vo2peak (β = 2.55; 95% CI: 2.05-3.06; P < 0.001). In contrast, no significant association was observed between cardiac output and Vo2peak (β = −0.88; 95% CI: −1.95 to 0.18; P = 0.10).

Discussion

The findings from this meta-analysis indicate that 13 weeks of systemic anticancer treatment results in a weighted mean decline in Vo2peak of approximately 2.1 mL·kg−1·min−1. Furthermore, Vo2peak remains lower in cancer survivors compared with noncancer control subjects, even years after the completion of treatment (Central Illustration). Given the established association between impaired Vo2peak and adverse clinical outcomes in cancer patients,57, 58, 59 these findings support the recommendation for exercise therapy aimed at preserving and improving Vo2peak during and following cancer treatment.

Central Illustration.

Impact of Systemic Anticancer Treatment on Vo2peak During and After Therapy

The illustration depicts the effects of systemic anticancer treatment on cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) during active treatment and the survivorship phase, compared with noncancer control subjects. It highlights both the acute decline in CRF during treatment and the sustained, persistent decrease among cancer survivors following therapy. Vo2peak = peak oxygen consumption.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to extensively characterize the magnitude of systemic therapy–related impairments across various cancer settings. Most previous studies evaluating CRF responses have focused on a single cancer type. For example, Jones et al5 compared Vo2peak in 248 women from 4 cross-sectional breast cancer cohorts with population-based normative data and found Vo2peak levels to be 22% to 33% lower than age- and sex-predicted sedentary values. Similarly, Peel et al7 reported that Vo2peak was 25% lower in patients with breast cancer after adjuvant therapy compared with healthy, sedentary women. Our results, drawn from a large, heterogeneous cohort of patients with cancer, significantly extend evidence by providing a comprehensive assessment of systemic therapy–related impairments across multiple cancer types.

Another noteworthy finding was the similar magnitude of Vo2peak decline across subgroups. Specifically, treatment regimens for esophagogastric cancers (commonly treated with cisplatin and oxaliplatin), breast cancers (commonly treated with epirubicin and doxorubicin), and colon and rectal cancers (commonly treated with combination regimens as leucovorin calcium [folinic acid], fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin) resulted in comparable declines in Vo2peak. However, a subgroup analysis based on treatment type was not feasible, because of insufficient reporting, as 44% of the total sample comprised participants with mixed cancer diagnoses. Given that heterogeneity in cancer diagnoses and treatment modalities may obscure treatment-specific impacts, further research focused on specific cancer types and comprehensive longitudinal assessments is needed to better understand therapy-specific changes in Vo2peak.

In addition to highlighting the decline in CRF during cancer treatment, our findings also revealed lower CRF in long-time cancer survivors compared with noncancer control subjects. Given that Vo2peak typically declines by approximately 10% per decade,60 the magnitude of CRF impairment in a typical 50-year-old individual is comparable with that of a 70-year-old individual without a history of systemic cancer treatment. Other studies suggest that cancer survivors treated with systemic therapies are also at risk for accelerated aging processes. For instance, Guida et al61 reported that adult childhood cancer survivors, compared with age-matched control subjects, exhibited an aging rate that was 5% faster per year, were biologically 0.6 to 6.44 years older, and aged 5 to 16 years beyond the expected biological age. Collectively, these results support the notion that systemic cancer therapy contributes to accelerated and sustained aging phenotypes.62

The direct and indirect adverse effects of anticancer therapy can affect all stages of the O2 cascade. However, unlike previous research in noncancer settings, which suggests that blunted cardiovascular O2 delivery is primarily responsible for poor Vo2peak,1 our meta-regression did not identify a significant association between cardiac output and CRF.

Interestingly, we found that lower a-vO2 difference values were correlated with lower CRF levels. These finding suggests that systemic anticancer treatment may disproportionately affect the peripheral components of the cardiopulmonary-muscle axis, rather than the central components. However, it is worth noting that variations in methods used to measure cardiac output, such as stress echocardiography, impedance cardiography, and stress magnetic resonance imaging, may have influenced the observed associations. Given that systemic anticancer therapies can affect the entire cardiopulmonary-muscle axis, including pulmonary and vascular function,63 with well-established associations between Vo2peak and cardiac output in cancer survivors,44,49 additional research is essential to comprehensively understand the physiological determinants of CRF impairments in this population.

Skeletal muscle deconditioning during systemic anticancer treatment may also contribute to impaired CRF. Mijwel et al64 reported a reduction in muscle fiber cross-sectional area, a shift toward a greater proportion of fast-twitch fibers, and decreased mitochondrial content and function. Recent research further suggests a link between chemotherapy and reduced muscle quality, specifically through intermuscular adipose tissue (ie, myosteatosis). For example, Beaudry et al42 reported a strong correlation between increased intermuscular adipose tissue content and reduced CRF during chemotherapy for breast cancer. Importantly, longitudinal data have indicated that elevated myosteatosis levels persisted 1 year after chemotherapy in breast cancer survivors.27 These findings suggest that systemic cancer treatment may also affect peripheral factors that influence the a-vO2 difference.

Strategies to prevent or reverse treatment-associated impairments in Vo2peak are essential. Exercise training is widely considered the most effective intervention to improve Vo2peak. Findings from a meta-analysis involving cancer survivors during and after treatment demonstrated that exercise training significantly improved Vo2peak relative to sedentary control subjects.65 However, it remains unclear whether initiating exercise during or after systemic therapy is the optimal timing for improving Vo2peak. Recent trials involving patients undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer have indicated that continuous exercise training, both during and after therapy, can lead to clinically meaningful improvements in Vo2peak compared with usual care.33,35

Intriguingly, the magnitude of exercise-induced improvement in Vo2peak may be insufficient to fully mitigate or reverse short-term therapy–related or long-term therapy–related impairments. This suggests that existing national guidelines,57, 58, 59 which recommend generic exercise doses (eg, 3 sessions per week, 30-60 minutes per session at moderate intensity for 12-15 weeks), may be inadequate for enhancing Vo2peak in patients previously treated with systemic therapy. Consequently, there is a critical need to investigate alternative exercise doses, physiologically targeted regimens, and exercise adjuncts such as nutritional or pharmacologic interventions to maximize Vo2peak response among cancer survivors.

Study limitations

First, our analysis included a heterogeneous sample comprising various cancer diagnoses and treatment regimens. The presence of mixed diagnoses, variability in treatment combinations across studies, and inconsistent reporting complicated the investigation of specific systemic treatment effects on Vo2peak. Additionally, the study sample primarily included women with early-stage breast cancer, which necessitates caution when generalizing our findings to other cancer populations. This meta-analysis also incorporated data from various study designs. Although this diversity may influence the interpretation of our findings, it was essential to provide a comprehensive assessment of the available evidence, given the diverse nature of research in this field.

Second, studies included in this analysis generally had relatively small sample sizes. Third, as with all meta-analyses, we are reliant on the data reported in published studies, which may introduce limitations in data quality and completeness.

Finally, the limited number of trials measuring peak cardiac output and a-vO2 difference may have influenced the conclusions drawn from the meta-regression. This highlights the need for methodologically rigorous and extensive trials to better understand the physiological mechanisms underlying CRF impairments during and following cancer treatment.

Conclusions

Systemic anticancer therapy leads to significant and persistent impairments in CRF. Our findings support recommendations for exercise therapy aimed at mitigating and reversing CRF decline during and after cancer therapy.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: Poor CRF is associated with a higher symptom burden and an increased prevalence of long-term treatment–related cardiovascular disease risk factors in cancer survivors. Our findings confirm that systemic cancer therapy impairs CRF and indicate that cancer survivors have lower CRF levels than noncancer control subjects, underscoring the need for targeted interventions to reduce the long-term risk for severe disease in this population.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: Further research is essential to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the physiological determinants contributing to persistent CRF impairments in cancer survivors.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

Drs Johansen and Nilsen were supported by the Norwegian Cancer Society and AKTIV mot kreft (AKTIV Against Cancer). Dr Scott is supported by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748). All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For supplemental Methods, figures, tables, and references, please see the online version of this paper.

Appendix

References

- 1.Ross R., Blair S.N., Arena R., et al. Importance of assessing cardiorespiratory fitness in clinical practice: a case for fitness as a clinical vital sign: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134(24):e653–e699. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cupit-Link M.C., Kirkland J.L., Ness K.K., et al. Biology of premature ageing in survivors of cancer. ESMO Open. 2017;2(5) doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones L.W., Haykowsky M., Pituskin E.N., et al. Cardiovascular reserve and risk profile of postmenopausal women after chemoendocrine therapy for hormone receptor—positive operable breast cancer. Oncologist. 2007;12(10):1156–1164. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-10-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groarke J.D., Payne D.L., Claggett B., et al. Association of post-diagnosis cardiorespiratory fitness with cause-specific mortality in cancer. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020;6(4):315–322. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones L.W., Courneya K.S., Mackey J.R., et al. Cardiopulmonary function and age-related decline across the breast cancer survivorship continuum. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(20):2530–2537. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.9014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellissimo M.P., Canada J.M., Jordan J.H., et al. Changes in physical activity, functional capacity, and cardiac function during breast cancer therapy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2022;31(7):1509. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peel A.B., Thomas S.M., Dittus K., Jones L.W., Lakoski S.G. Cardiorespiratory fitness in breast cancer patients: a call for normative values. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(1) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine B.D. Vo2max: what do we know, and what do we still need to know? J Physiol. 2008;586(1):25–34. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bassett D.R.J., Howley E.T. Limiting factors for maximum oxygen uptake and determinants of endurance performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(1):70–84. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200001000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koelwyn G.J., Jones L.W., Moslehi J. Unravelling the causes of reduced peak oxygen consumption in patients with cancer: complex, timely, and necessary. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(13):1320–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Cancer Institute NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/survivor

- 12.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwarzer G., Carpenter J.R., Rücker G. Springer International; Cham, Switzerland: 2015. Meta-Analysis with R. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen S.K., Brown V., White D., et al. Multimodal prehabilitation during neoadjuvant therapy prior to esophagogastric cancer resection: effect on cardiopulmonary exercise test performance, muscle mass and quality of life—a pilot randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29(3):1839–1850. doi: 10.1245/s10434-021-11002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Majid S., Wilson L.D., Rakovski C., Coburn J.W. Effects of exercise on biobehavioral outcomes of fatigue during cancer treatment: results of a feasibility study. Biol Res Nurs. 2015;17(1):40–48. doi: 10.1177/1099800414523489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung W.P., Yang H.L., Hsu Y.T., et al. Real-time exercise reduces impaired cardiac function in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2022;65(2) doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2021.101485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornette T., Vincent F., Mandigout S., et al. Effects of home-based exercise training on Vo2 in breast cancer patients under adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SAPA): a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;52(2):223–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Courneya K.S., Segal R.J., Mackey J.R., et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(28):4396–4404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Culos-Reed S., Leach H.J., Capozzi L.C., Easaw J., Eves N., Millet G.Y. Exercise preferences and associations between fitness parameters, physical activity, and quality of life in high-grade glioma patients. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(4):1237–1246. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3516-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egegaard T., Rohold J., Lillelund C., Persson G., Quist M. Pre-radiotherapy daily exercise training in non-small cell lung cancer: a feasibility study. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2019;24(4):375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foulkes S.J., Howden E.J., Haykowsky M.J., et al. Exercise for the prevention of anthracycline-induced functional disability and cardiac dysfunction: the BREXIT study. Circulation. 2023;147(7):532–545. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.062814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groehs R.V., Negrao M.V., Hajjar L.A., et al. Adjuvant treatment with 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin does not influence cardiac function, neurovascular control, and physical capacity in patients with colon cancer. Oncologist. 2020;25(12) doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2020-0225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hornsby W.E., Douglas P.S., West M.J., et al. Safety and efficacy of aerobic training in operable breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a phase II randomized trial. Acta Oncol. 2014;53(1):65–74. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.781673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howden E.J., Bigaran A., Beaudry R., et al. Exercise as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool for the prevention of cardiovascular dysfunction in breast cancer patients. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26(3):305–315. doi: 10.1177/2047487318811181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howden E.J., Foulkes S., Dillon H.T., et al. Traditional markers of cardiac toxicity fail to detect marked reductions in cardiorespiratory fitness among cancer patients undergoing anti-cancer treatment. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;22(4):451–458. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeaa421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jack S., West M.A., Raw D., et al. The effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on physical fitness and survival in patients undergoing oesophagogastric cancer surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(10):1313–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirkham A.A., Pituskin E., Mackey J.R., et al. Longitudinal changes in skeletal muscle metabolism, oxygen uptake, and myosteatosis during cardiotoxic treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Oncologist. 2022;27(9):e748–e754. doi: 10.1093/oncolo/oyac092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mowafy Z.M.E., Zoheiry I.M.I., Elmonem M.G.A., Katter D. Efficacy of aerobic training on maximal oxygen consumption and total leukocytes count after chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Int J ChemTech Research. 2016;9(4):34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navidi M., Phillips A.W., Griffin S.M., et al. Cardiopulmonary fitness before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with oesophagogastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2018;105(7):90090–90096. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ndjavera W., Orange S.T., O’Doherty A.F., et al. Exercise-induced attenuation of treatment side-effects in patients with newly diagnosed prostate cancer beginning androgen-deprivation therapy: a randomised controlled trial. BJU Int. 2020;125(1):28–37. doi: 10.1111/bju.14922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quist M., Langer S.W., Lillelund C., et al. Effects of an exercise intervention for patients with advanced inoperable lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy: A randomized clinical trial. Lung Cancer. 2020;145:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider C., Ryffel C., Stütz L., et al. Supervised exercise training in patients with cancer during anthracycline-based chemotherapy to mitigate cardiotoxicity: a randomized-controlled-trial. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1283153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott J.M., Lee J., Herndon J.E., et al. Timing of exercise therapy when initiating adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: a randomized trial. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(46):4878–4889. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomson I.G., Wallen M.P., Hall A., et al. Neoadjuvant therapy reduces cardiopulmunary function in patients undegoing oesophagectomy. Int J Surg. 2018;53:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Schoot G.G.F., Ormel H.L., Westerink N.D.L., et al. Optimal timing of a physical exercise intervention to improve cardiorespiratory fitness. JACC CardioOncol. 2022;4(4):491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2022.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vincent F., Deluche E., Bonis J., et al. Home-based physical activity in patients with breast cancer: during and/or after chemotherapy? Impact on cardiorespiratory fitness. A 3-arm randomized controlled trial (APAC) Integr Cancer Ther. 2020;19 doi: 10.1177/1534735420969818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West M.A., Loughney L., Lythgoe D., et al. Effect of prehabilitation on objectively measured physical fitness after neoadjuvant treatment in preoperative rectal cancer patients: a blinded interventional pilot study. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(2):244–251. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.West M.A., Baker W.C., Rahman S., et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing has greater prognostic value than sarcopenia in oesophago-gastric cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy and surgical resection. J Surg Oncol. 2021;124(8):1306–1316. doi: 10.1002/jso.26652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiestad T.H., Raastad T., Nordin K., et al. The Phys-Can observational study: adjuvant chemotherapy is associated with a reduction whereas physical activity level before start of treatment is associated with maintenance of maximal oxygen uptake in patients with cancer. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2020;12:53. doi: 10.1186/s13102-020-00205-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dillon H.T., Foulkes S., Horne-Okano Y.A., et al. Rapid cardiovascular aging following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for hematological malignancy. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.926064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baracos V.E., Urtasun R.C., Humen D.P., Haennel R.G. Physical fitness of patients with small cell lung cancer. Clin J Sport Med. 1994;4(4):223–227. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beaudry R.I., Kirkham A.A., Thompson R.B., Grenier J.G., Mackey J.R., Haykowsky M.J. Exercise intolerance in anthracycline-treated breast cancer survivors: the role of skeletal muscle bioenergetics, oxygenation, and composition. Oncologist. 2020;25(5):e852–e860. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cramer L., Hildebrandt B., Kung T., et al. Cardiovascular function and predictors of exercise capacity in patients with colorectal cancer. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(13):1310–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beaudry R.I., Haykowsky M.J., MacNamara J.P., et al. Cardiac mechanisms for low aerobic power in anthracycline treated, older, long-term breast cancer survivors. Cardiooncology. 2022;4(4):8. doi: 10.1186/s40959-022-00134-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crowgey T., Peters K.B., Hornsby W.E., et al. Relationship between exercise behavior, cardiorespiratory fitness, and cognitive function in early breast cancer patients treated with doxorubicin-containing chemotherapy: a pilot study. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014;39(6):724–729. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2013-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones L.W., Haykowsky M., Peddle C.J., et al. Cardiovascular risk profile of patients with HER2/neu-positive breast cancer treated with anthracycline-taxane-containing adjuvant chemotherapy and/or trastuzumab. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2007;16(5):1026–1031. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khouri M.G., Hornsby W.E., Risum N., et al. Utility of 3-dimensional echocardiography, global longitudinal strain, and exercise stress echocardiography to detect cardiac dysfunction in breast cancer patients treated with doxorubicin-containing adjuvant therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;143(3):531–539. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2818-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirkham A.A., Campbell K.L., McKenzie D.C. Comparison of aerobic exercise intensity prescription methods in breast cancer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(8):1443–1450. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182895195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kirkham A.A., Haykowsky M.J., Beaudry R.I., et al. Cardiac and skeletal muscle predictors of impaired cardiorespiratory fitness post-anthracycline chemotherapy for breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93241-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koelwyn G.J., Lewis N.C., Ellard S.L., et al. Ventricular-arterial coupling in breast cancer patients after treatment with anthracycline-containing adjuvant chemotherapy. Oncologist. 2016;21(2):141–149. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Long T.M., Lee F., Lam K., et al. Cardiovascular testing detects underlying dysfunction in childhood leukemia survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020;52(3):525–534. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reding K.W., Brubaker P., D’Agostino R., et al. Increased skeletal intermuscular fat is associated with reduced exercise capacity in cancer survivors: a cross-sectional study. Cardiooncology. 2019;5:3. doi: 10.1186/s40959-019-0038-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tonorezos E.S., Snell P.G., Moskowitz C.S., et al. Reduced cardiorespiratory fitness in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(8):1358–1364. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu A.F., Flynn J.R., Moskowitz C.S., et al. Long-term cardiopulmonary consequences of treatment-induced cardiotoxicity in survivors of ERBB2-positive breast cancer. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(3):309–317. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.5586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ness K.K., Plana J.C., Joshi V.M., et al. Exercise intolerance, mortality, and organ system impairment in adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(1):29–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Caru M., Samoilenko M., Drouin S., et al. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia survivors have a substantially lower cardiorespiratory fitness level than healthy Canadians despite a clinically equivalent level of physical activity. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2019;8(6):674–683. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2019.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ligibel J.A., Bohlke K., May A.M., et al. Exercise, diet, and weight management during cancer treatment: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(22):2491–2507. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.00687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Campbell K.L., Winters-Stone K., Wiskemann J., et al. Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: consensus statement from international multidisciplinary roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(11):2375–2390. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gilchrist S.C., Barac A., Ades P.A., et al. Cardio-oncology rehabilitation to manage cardiovascular outcomes in cancer patients and survivors. Circulation. 2019;139(21):e997–e1012. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fleg J.L., Morrell C.H., Bos A.G., et al. Accelerated longitudinal decline of aerobic capacity in healthy older adults. Circulation. 2005;112(5):674–682. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.545459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guida J.L., Hyun G., Belsky D.W., et al. Associations of seven measures of biological age acceleration with frailty and all-cause mortality among adult survivors of childhood cancer in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. Nat Cancer. 2024;5(5):731–741. doi: 10.1038/s43018-024-00745-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guida J.L., Agurs-Collins T., Ahles T.A., et al. Strategies to prevent or remediate cancer and treatment-related aging. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(2):112–122. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dillon H.T., Foulkes S.J., Baik A.H., et al. Cancer therapy and exercise intolerance: the heart is but a part: JACC: CardioOncology state-of-the-art review. JACC CardioOncol. 2024;6(4):496–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2024.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mijwel S., Cardinale D.A., Norrbom J., et al. Exercise training during chemotherapy preserves skeletal muscle fiber area, capillarization, and mitochondrial content in patients with breast cancer. FASEB J. 2018;32(10):5495–5505. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700968R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scott J.M., Zabor E.C., Schwitzer E., et al. Efficacy of exercise therapy on cardiorespiratory fitness in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(22):2297–2305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.5809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.