Abstract

Mitochondria play a pivotal role in energy production, metabolism, and cellular signaling, serving as key regulators of cellular functions, including differentiation and tissue-specific adaptation. The interplay between mitochondria and the nucleus is crucial for coordinating these processes, particularly through the supply of metabolites for epigenetic modifications that facilitate nuclear-mitochondrial interactions. To investigate tissue-specific mitochondrial adaptations at the molecular level, we conducted RNA sequencing data analyses of kidney, heart, brain, and ovary tissues of female buffaloes, focusing on variations in mitochondrial gene expression related to amino acid metabolism. Our analysis identified 82 nuclear-encoded mitochondrial transcripts involved in amino acid metabolism, with significant differential expression patterns across all tissues. Notably, the heart, brain, and kidney—tissues with higher energy demands—exhibited elevated expression levels compared to the ovary. The kidney displayed unique gene expression patterns, characterized by up-regulation of genes involved in glyoxylate metabolism and amino acid catabolism. In contrast, comparative analysis of the heart and kidney versus the brain revealed shared up-regulation of genes associated with fatty acid oxidation. Gene ontology and KEGG pathway analyses confirmed the enrichment of genes in pathways related to amino acid degradation and metabolism. These findings highlight the tissue-specific regulation of mitochondrial gene expression linked to amino acid metabolism, reflecting mitochondrial adaptations to the distinct metabolic and energy requirements of different tissues in buffalo. Importantly, our results underscore the relevance of mitochondrial adaptations not only for livestock health but also for understanding metabolic disorders in humans. By elucidating the molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial function and their tissue-specific variations, this study provides insights that could inform breeding strategies for enhanced livestock productivity and contribute to therapeutic approaches for human metabolic diseases. Thus, our findings illustrate how mitochondria are specialized in a tissue-specific manner to optimize amino acid utilization and maintain cellular homeostasis, with implications for both animal welfare and human health.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00726-025-03447-4.

Keywords: Mitochondria, Nuclear, Buffalo, Amino acid, Tissue-specific

Introduction

Oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) is the major hub for cellular bioenergetics, signaling, and metabolism mediated by mitochondria. The response mechanism to oxygen uptake of almost all cells is the OXPHOS, consisting of five enzyme complexes and two electron carriers that generate ATP (Javadov et al. 2020; Vercellino and Sazanov 2022). Although mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles, they also have their own DNA (mtDNA), which in collaboration with mitochondrial biogenesis plays a crucial role in the synchronized process of mtDNA replication, transcription, and translation. Mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and OXPHOS, are essentials for the metabolism of energy sources to support cellular function and survival (Sharma et al. 2024). The tight coupling of these two processes maintains energy balance under various environmental and internal demands. In this context, mitochondria are involved in both cell metabolism and gene expression and communicate with the nucleus to regulate nuclear gene expression and mitochondrial cellular metabolism (Liu et al. 2023a, b; Kappler et al. 2019). Several of the metabolites produced during the process of the TCA cycle are important as signaling molecules and for the formation of various macromolecular structures. Mitochondria are constantly exchanging signals with the cell and adapting to the structural and functional metabolic changes (Mishra and Chan 2016; Esteban-Martínez et al. 2017; Martínez-Reyes and Chandel 2020). The energy requirement of different tissues determines the selective adaptations of mitochondrial profiles, for instance, density, shape, OXPHOS, and mitochondria-nuclear crosstalk. These tissue-specific mitochondrial adaptations are crucial for ensuring that energy production and utilization are tailored to the distinct needs of each tissue type (Fernández-Vizarra et al. 2011; Giacomello et al. 2020).

The proteins and lipids are played as the main controlling factors of mitochondrial activity. Since mitochondrial proteins mediate almost all metabolic conversions, analyzing their abundance in different tissues provides key insights into tissue-specific metabolic activities. Almost all 20 amino acids serve not only as building blocks for protein synthesis but also as energy sources and precursors for essential metabolites that influence gene expression and cellular processes (Hassinen 2014; Wolfe et al. 2024). Amino acid metabolism is one of the most important metabolic processes providing energy in the cell, relying largely on mitochondrial enzymes and genes. The synthesis of the amino acids aspartate and arginine depends on the activity of the respiratory chain, which is essential for cell proliferation. Many of the degradation mechanisms of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) take place in the mitochondrial matrix and involve energetic metabolism, mitochondrial biogenesis, and protein surveillance mechanisms in mitochondria and cytosol (Li and Hoppe 2023).

Different disorders and diseases result from metabolic changes and dysfunctions in mitochondrial enzymes for the metabolism of amino acids (Guda et al. 2007; Prasun 2020). Mitochondrial functions and metabolic activity vary in different tissues and cell types, especially in livestock. Prior research in our laboratory identified significant tissue-specific differences in mitochondrial functions in buffaloes. These variations in mitochondrial activity were strongly linked to the expression of mitochondrial protein-coding genes (mtPCGs), indicating that OXPHOS activity is finely tuned to meet the distinct energy demands of each tissue (Sadeesh et al. 2023). The variations were relatively high across different tissues, particularly in the nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein-coding genes of complexes I (Sadeesh et al. 2024a), II (Sadeesh et al. 2024b), and V (Sadeesh et al. 2025a, b), which are associated with lipid and carbohydrate metabolism (Sadeesh et al. 2025b), as well as in the mitochondrial-encoded non-coding RNAs in buffalo samples (Sadeesh and Malik 2024). These findings point to the fact that mitochondrial activities are regulated highly concerning the energy requirements for every tissue (Sadeesh et al. 2023).

Building on this foundation, our study delves into the tissue-specific diversity of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes involved in amino acid metabolism across various tissues of female buffaloes. With limited existing information on this topic, we set out to explore the variations in mitochondrial transcript expression associated with amino acid metabolism. We hypothesize that there are tissue-specific variations in the expression of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes involved in amino acid metabolism across different tissues in female buffaloes. Specifically, we predict that distinct patterns of mitochondrial transcript expression will be observed in the kidney, heart, brain, and ovary, reflecting the metabolic demands of each tissue. We analyzed RNA sequencing data from the kidney, heart (left ventricle), brain (cerebellum), and ovary tissues of healthy female buffaloes aged 3 to 5 years. By examining the functional connections between mitochondria and amino acid metabolism, we aim to enhance our understanding of mitochondrial variations and their implications for tissue-specific metabolic adaptations in livestock.

Material and methods

Animals and sampling

The tissues of four healthy post-pubertal female buffaloes were prepared immediately after being slaughtered, ensuring they would be expeditiously transported to the laboratory under cold chain conditions. The tissues were meticulously selected for each animal by using a chilled normal saline solution containing antibiotics including the renal cortex (kidney), left ventricle (heart), the cerebellum of the brain, and the ovary. This study was designed to mitigate seasonal and age-related variances by acquiring specimens from a similar age cohort (3 to 5 years) during the winter period to ensure a similar sample size. A strict selection of tissues that were free of abrasions and lesions was conducted, and after three washes with normal saline, they were stored at −80 °C until the analysis could be completed.

RNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing, and analysis of RNA-Seq data

Total RNA was extracted from all four animals for each selected tissue type using the TRIzol method (Invitrogen, Cat No. 15596026), followed by further processing with the Zymo RNA Clean and Concentrator Kit (ZYMO Research, USA, Cat No. R1017). RNA quantification was performed using a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer, and quality control (QC) was assessed through 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Samples that passed QC were subjected to RNA-Seq library preparation at Nucleome Informatics Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad, India, and sequenced using paired-end (PE) sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform. For RNA-Seq data analysis, raw sequence reads were stringently filtered to remove low-quality sequences and adapter contamination, resulting in clean data with per-base sequencing error rates below 0.03% and a Phred score Q30 above 91.63%. The quality of the data was evaluated using FASTP (Chen et al. 2018), and using the HISAT2 algorithm (Kim et al. 2019) sequences were aligned to the Bubalus bubalis reference genome (UOA_WB_1). Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) analysis was performed using DESeq2, which employed empirical Bayes methods to estimate priors and posterior distributions for log fold changes and dispersion. A set of 82 genes involved in amino acid metabolism, based on Mitocarta 3.0, was included in the analysis. The DEGs were identified across various tissue comparisons (kidney versus heart, kidney versus brain, kidney versus ovary, heart versus brain, heart versus ovary and brain versus ovary), focusing on commonly expressed genes. Genes with a log2 fold change (FC) greater than + 1 were classified as up-regulated, while those with a log2 FC less than − 1 were classified as down-regulated, with an adjusted p-value threshold of 0.05 (Robinson et al. 2010). A hierarchical cluster analysis using average linkage was conducted on prominent DEGs across different tissues, and a volcano plot of the DEGs was generated using the ChiPlot database.

Gene ontology and pathway analyses

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analyses were conducted on the identified DEGs using the clusterProfiler R package. A strict p-value cutoff of ≤ 0.05 was applied to ensure that only statistically significant genes were included in further analysis.

Results

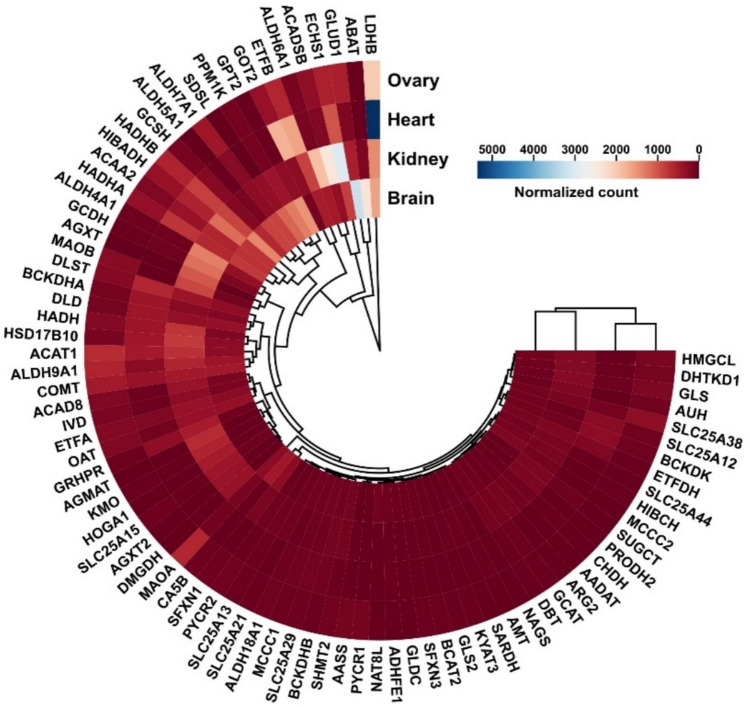

A standardized pipeline was employed to preprocess the raw sequencing data, ensuring consistent quality control and minimizing technical variability. The RNA-Seq data utilized for this study were previously examined in research focusing on nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein-coding genes of complexes I, II, and ATP synthase, which are associated with lipid and carbohydrate metabolism (Sadeesh et al. 2024a, b; Sadeesh et al. 2025a, b). Since information on tissue diversity regarding nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes involved in amino acid metabolism was not available in farm animals, we focused on 82 nuclear-encoded mitochondrial transcripts involved in amino acid metabolism pathways in this study, identified using MitoCarta 3.0. The DEG analysis was performed following normalization to compare expression levels across the four tissues. Several transcripts were found to be differentially expressed in the kidney, heart, and brain, while the ovary exhibited lower overall transcript expression. Specifically, 77 of the 82 transcripts were differentially expressed in the kidney, while all 82 were differentially expressed in the heart and brain. The ovary exhibited the lowest 63 overall transcript expression. The expression patterns of these genes are expressed in the form of hierarchical clustering, and heatmap based on the normalized counts, incorporating all transcripts across the tissue types (Fig. 1 and Supplementary File S1: Table 1). These analyses’ outcomes revealed consistent variations in mitochondrial transcript associated with amino acid metabolism expression across each tissue type. Notably, tissues with higher energy demands, such as the heart and brain, showed a higher number of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes abundance, followed by the kidney and ovary. In the heart, the LDHB transcript demonstrated the most abundant expression compared to other transcripts and tissues, as indicated by the blue color in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Heatmap of hierarchical clustering of gene expression based on normalized count across tissues—kidney, heart, brain, and ovary. Colour key indicates the level of expression. The variability in gene expression between tissues is represented by the height of the dendrogram branches

Differential expression analyses across various tissue comparison

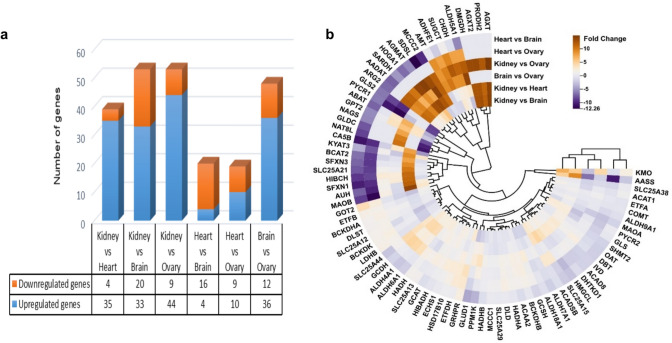

We initially focused on identifying transcripts that were significantly up- or down-regulated using a strict threshold of adjusted p-value (padj) < 0.05 and |log2 fold change|≥ 1. This approach ensured the statistical significance and biological relevance of the identified genes. The kidney displayed notably distinct expression patterns compared to the heart, brain, and ovary. Specifically, 35 genes were up-regulated and 4 were down-regulated in the kidney compared to the heart. Similar trends were observed when comparing the kidney to the brain (33 up-regulated, 20 down-regulated) and the ovary (44 up-regulated, 9 down-regulated). In contrast, comparisons between the heart and brain, as well as the heart and ovary, identified a smaller number of DEGs. The heart exhibited 4 up- and 16 down-regulated genes compared to the brain, and 10 up- and 9 down-regulated genes compared to the ovary. Moreover, comparisons between the brain and ovary revealed significant differential expression in 48 genes, with 36 up- and 12 down-regulated (Fig. 2a). To visualize the expression patterns, hierarchical clustering, and heatmap generation were conducted, incorporating all genes across the distinct tissue comparisons (Fig. 2b). The results obtained from this analysis provided additional support for the observed tissue-specific expression patterns. The outcomes of these analyses elucidate intricate relationships among the expressed genes, delineating distinct clusters revealing consistent variations in mitochondrial genes associated with amino acid metabolism expression across each tissue type. The color key in Fig. 2b reflects the degree of expression similarity between tissue types, with the same colors indicating greater similarity in gene expression patterns.

Fig. 2.

Differential gene expression analysis across various tissue comparisons (kidney versus heart, kidney versus brain, kidney versus ovary, heart versus brain, heart versus ovary, brain versus ovary). a Histogram of DEG number statistics b A Circular heatmap illustrating a hierarchical cluster analysis of Gene expression. The color key indicates expression levels. The scale on the right-hand side shows the color code relative to log2 fold-change (log2-FC) in gene abundance. The variability in gene expression between tissues is reflected in the height of the dendrogram branches

A comparative analysis of gene expression in the kidney, heart, brain, and ovary revealed distinct patterns of up- and down-regulated genes across these tissues. When comparing the kidney to the heart, brain, and ovary, 17 up-regulated genes were shared across all comparisons. Notably, AGXT, AGXT2, AGMAT, DMGDH, and HOGA1 were highly abundant. In contrast, only one down-regulated gene, SLC25A12, was consistently observed in the kidney compared to the other tissues. The heart versus brain comparison revealed the fewest up-regulated genes. Among these, GOT2 and GRHPR were commonly up-regulated in both the kidney versus brain and heart versus brain comparisons. Similarly, LDHB and ETFB were up-regulated in the heart when compared to both the brain and ovary. The brain versus ovary comparison showed an overlap with the kidney versus ovary comparison in terms of up-regulated genes. However, gene expression patterns in the heart versus ovary comparison displayed fewer up-regulated genes. Importantly, BCKDHB, DLD, and ETFDH were consistently up-regulated in all three tissue comparisons.

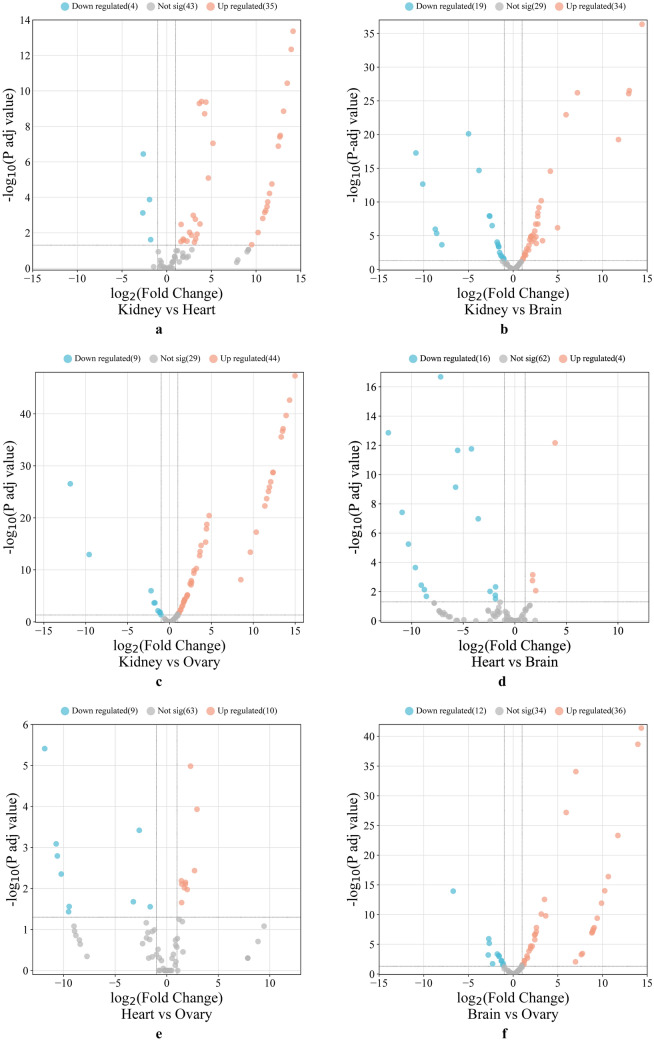

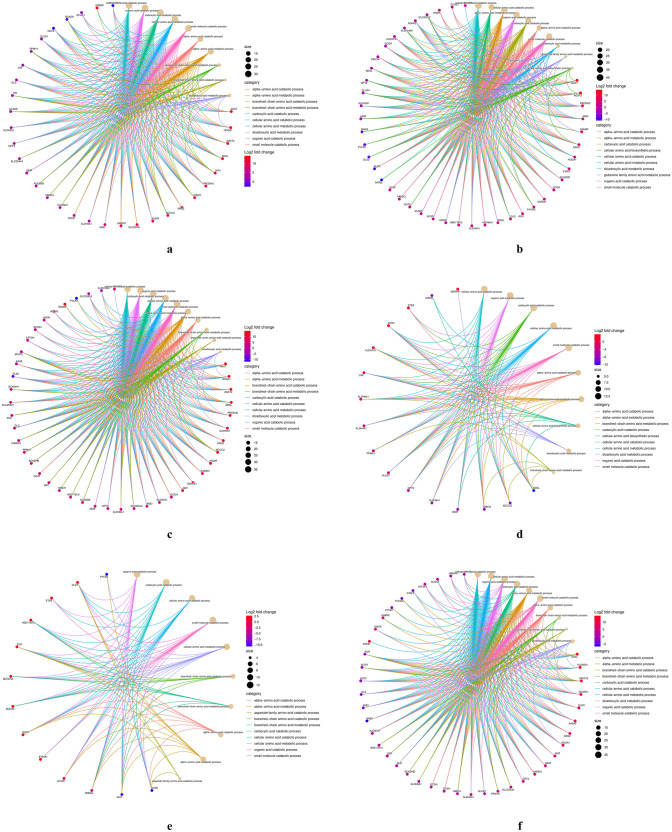

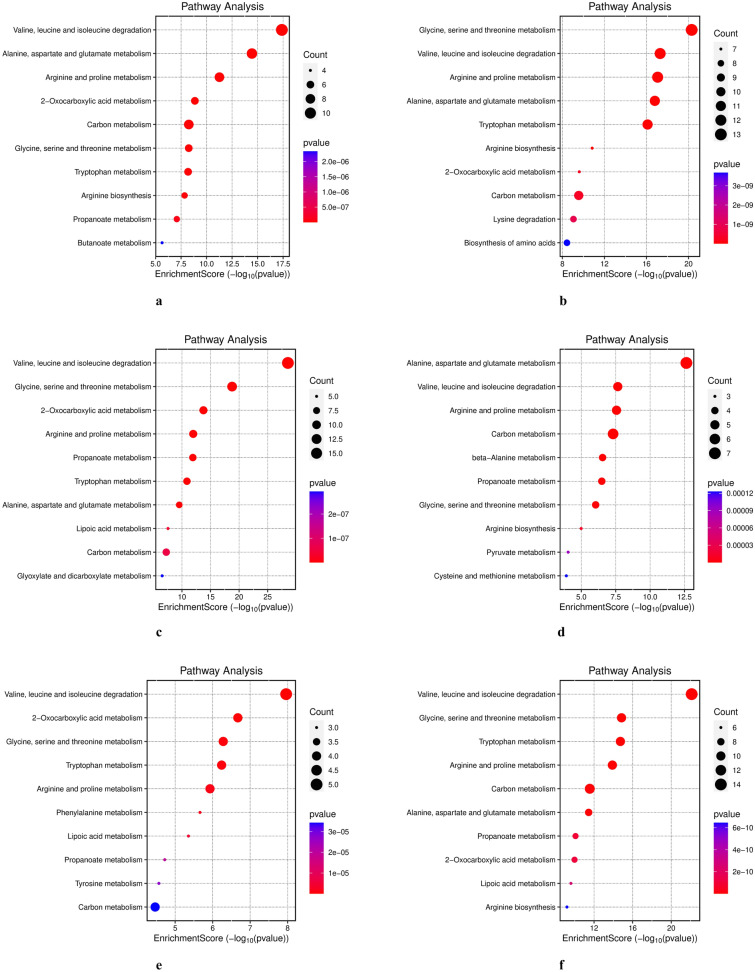

A volcano plot (Fig. 3a–f) depicted the distribution of DEGs across various tissue comparisons, highlighting nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes associated with amino acid metabolism. We conducted GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses on transcripts that showed significant differential expression across tissue-specific comparisons to investigate these differences further. The GO analysis revealed enrichment for distinct GO terms, with most tissue comparisons displaying a significantly higher abundance of genes involved in amino acid catabolic and metabolic process. The top ten significantly enriched terms in the biological processes (BP), molecular function (MF), and cellular component (CC) categories for each tissue comparison are shown in Supplementary File S2, Figures S2a–f. We also utilized a gene concept plot (cnetplot) to visualize GO enrichment analysis results. Each cnetplot depicts the most significantly enriched biological processes, with lines connecting genes from various GO categories. The different colors of these lines represent the relationships between genes and GO terms (Fig. 4a–f). We then performed a KEGG pathway enrichment analysis to identify the impacted metabolic pathways. The results indicated that DEGs were significantly enriched (p < 0.05) in pathways related to amino acid metabolism (Fig. 5a–f). These pathways included valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation, arginine and proline metabolism, other amino acid metabolism, carbon metabolism, and arginine biosynthesis. These findings were consistent across all tissue comparisons.

Fig. 3.

The volcano plot of differentially expressed genes was plotted across various tissue comparison a kidney versus heart b kidney versus brain c kidney versus ovary d heart versus brain e heart versus ovary f brain versus ovary. The x-axis is the log2 expression values (fold change), and the y-axis values are the base mean expression values (Adj p-value)

Fig. 4.

Functional enrichment analysis results of differentially expressed genes across various comparisons: a kidney versus heart b kidney versus brain c kidney versus ovary d heart versus brain e heart versus ovary f brain versus ovary. The enrichment network cneplot shows the link between key DEGs and significant enriched BP. Each cluster ID is indicated with a specific colour. GO Gene ontology, DEGs differentially expressed genes, BP biological processes, CC cellular components, MF molecular functions

Fig. 5.

The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs. The significantly shared KEGG pathways of DEGs between different tissue comparison groups via KEGG enrichment analysis. a Kidney versus heart b kidney versus brain c kidney versus ovary d heart versus brain e heart versus ovary f brain versus ovary

Discussion

This study provides insight into tissue-specific variations in mitochondrial gene expression related to amino acid metabolism in buffalo tissues. RNA sequencing of kidney, heart, brain, and ovary tissues revealed distinct patterns of mitochondrial gene expression, particularly in high-energy demanding tissues such as the heart and brain. These findings align with previous studies showing the reliance of these tissues on nuclear-encoded mitochondrial transcripts for energy generation (Protasoni and Zeviani 2021; Filosto et al. 2011).

LDH isozymes are tetramers formed from various combinations of two types of subunits (Boyer et al., 1963). The heart, a metabolically active organ, showed elevated expression of LDHB, suggesting a significant reliance on lactate metabolism for energy under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. This is consistent with the heart’s ability to utilize diverse energy sources such as fatty acids, glucose, and lactate (Hui et al. 2017; Wu et al. 2023). LDHB is needed to regenerate NAD and to maintain the glycolytic process, NAD is important as a substrate. Study revealed that LDHB is mainly localized in the heart, whereas, LDHA is highly expressed in the liver tissues (Hui et al. 2017; Li et al. 2022; Hicks et al. 2023). The results of this study suggest that the heart may depend on lactate metabolism for energy demands if there is inhibition in pyruvate oxidation via mitochondria under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, as supported by the findings of Ramanathan et al. (2009).

The kidneys play a critical role in amino acid metabolism, particularly in deamination and transamination (Bequette 2003, Knol et al. 2024), which is reflected in the gene expression patterns observed in our study. In tissue comparisons, the kidney exhibited consistent upregulation of AGXT, AGXT2, AGMAT, DMGDH, and HOGA1 genes compared to the heart, brain, and ovary. These genes are involved in glyoxylate metabolism, detoxification, and amino acid catabolism, which are important for maintaining energy homeostasis. This supports the kidney to play a central role in nitrogen balance, waste excretion, deamination, as well as regulation of metabolic by-products (Ling et al. 2023; Buchalski 2019). Glyoxylate metabolism in the kidney releases a harmful waste product oxalate that can contribute to kidney damage through the formation of kidney stones. In the glyoxylate pathway, AGT encoded by AGXT genes (AGXT1 and AGXT2) are more relevant in oxalate metabolism and catalyze multiple other aminotransferase reactions (Gianmoena et al. 2021; Baltazar et al. 2023). Another precursor of glyoxylate is 4-hydroxyproline is catabolized into glycine via trans-4-hydroxy-L-proline oxidase or to glyoxylate via HOGA (HOGA1 gene), a mitochondrial enzyme. Moreover, glyoxylate can be reduced to glycolate by glyoxylate reductase (GRHPR), an enzyme that prevents the accumulation of glyoxylate and oxalate, thereby protecting against nephrotoxicity (Gianmoena 2017). Looking at this all, our study findings in the kidney comparisons with other tissue about the significant upregulation of AGXT, AGXT2, HOGA1, and related genes suggest enhanced glyoxylate and amino acid catabolism in this tissue compared to others. Our study’s GO and KEGG pathway analysis results also support this, which shows that genes mainly participate in amino acid catabolism processes.

An enzyme encoded by AGMAT that converts agmatine to putrescine, a downstream product in the alternative pathway of polyamine biosynthesis (Wang et al. 2014). Additionally, DMGDH is a mitochondrial matrix enzyme involved in the conversion of choline to glycine, a molecule with known anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory roles, particularly in protecting against ischemia-induced renal injury (Magnusson et al. 2015; Alves et al. 2019; Wevers et al. 2022). In our study, both AGMAT and DMGDH were up-regulated in kidney tissue compared to the heart, brain, and ovary. These findings align with the results of a transcriptome-wide association study on blood pressure, which identified a strong enrichment of AGMAT expression in the kidneys, correlating with a higher risk of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (Xu et al. 2023). Furthermore, DMGDH has been recognized as a potential biomarker for the development of ischemia-induced renal injury or other diseases (Magnusson et al. 2015; Zhu et al. 2018). On the other hand, the gene SLC25A12 showed down-regulation in all comparisons of kidneys with other tissues. Aspartate-glutamate carrier protein 1 encoded by SLC25A12 plays a pivotal role in a malate-aspartate shuttle and energy production transferring the reducing NADH from the cytosol to mitochondria. Previous studies have shown variable expression of SLC25A12 across tissues, including the heart, brain, skeletal muscle, and lung (Infantino et al. 2019; Palmieri 2020), which aligns with our findings.These differential expressions suggest tissue-specific metabolic variations, with the kidneys potentially prioritizing amino acid metabolism over pathways prominent in energy-demanding tissues.

A comparison of the heart and brain showed the smallest number of highly expressed genes, indicating that gene expression profiles differ between these metabolically divergent tissues. Among these, GOT2, involved in the malate-aspartate shuttle (Chen et al. 2016), and GRHPR were highly up-regulated in both heart versus brain and kidney versus brain comparisons. These findings suggest that these genes participate in metabolic pathways common to both the heart and kidney, but are less active in the brain. A study on rat cardiomyocytes reported that GOT2 mRNA expression is associated with cardiac hypertrophy induced by physiological aging (Liu et al. 2023a, b). Similarly, GRHPR is involved in glyoxylate detoxification and the regulation of oxalate synthesis, which is essential for maintaining cellular energy states and metabolic flexibility in these tissues (Knight et al. 2006).

In comparisons between the heart and brain, as well as the ovary, elevated expression of LDHB and ETFB was observed. The increased expression of LDHB in the heart aligns with the heart’s high energy demands, supporting aerobic metabolism (Hicks et al. 2023). ETFB is notably active in the heart, as well as in other tissues such as the liver, kidney, skeletal muscle, and fat, where fatty acid oxidation is a key energy source. Changes in ETFB expression can impact energy production, glucose homeostasis, ketogenesis, and the accumulation of metabolites (Henriques et al. 2021). These results reflect the heart’s unique metabolic needs and the prominence of mitochondrial pathways and bioenergetics in this tissue compared to others.

The nuclear genes BCKDHA, BCKDHB, DBT, and DLD encode components of the mitochondrial branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKDH) complex, which regulates BCAA metabolism and catalyzes the irreversible, rate-limiting step in their catabolism. In our study, BCKDHB, DLD, and ETFDH were consistently up-regulated in kidney, brain, and heart tissues when compared to the ovary. Other studies have shown that BCKDHB is most active in high-metabolic-demand tissues, such as the liver, heart, kidney, and brain, with lower activity observed in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue (Biswas et al. 2019; Mann et al. 2021). Hutson et al. (2005) found that BCKDH activity is highest in the liver and brain, with the kidney and heart showing about half of this activity. Our results support other studies that show that mitochondrial genes are essential for preserving cell energy balance and adapting to the metabolic demands of tissues (Picard et al. 2018; Sebastián and Zorzano 2018). Furthermore, our previous research on mitochondrial protein-coding genes in buffalo tissues showed tissue-specific variations in the expression of genes involved in OXPHOS, particularly the nuclear-encoded OXPHOS complex I, II, and V genes We observed that mitochondrial gene expression is proportional to the energy demands of tissues, with significant differences in the expression of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes, particularly in the heart, kidney, ovaries, and brain (Sadeesh et al. 2023; Sadeesh et al. 2024a, b; Sadeesh et al. 2025a, b). While we did not find direct evidence from human studies, the expected similarity in tissue-specific gene expression patterns based on energy requirements is supported by livestock models. Livestock models for specific human diseases offer notable advantages over rodent models in translating essential biological discoveries into practical prevention and treatment options for humans (Roth and Tuggle 2015). Thus, we anticipate similar results in humans, suggesting that functional and metabolic demands shape gene expression across species. The observed tissue-specific differences in gene expression and pathway distribution highlight the complexity of buffalo metabolism, likely reflecting the varying energy requirements and functions of these tissues. These insights support further exploration of the molecular mechanisms underlying these metabolic adaptations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, changes in mitochondrial structure and function are closely linked to metabolic alterations, driving mitochondrial remodeling. Our study identifies tissue-specific differences in the expression of nuclear-mitochondrial genes related to amino acid metabolism. Notably, in kidney pathology, genes involved in glyoxylate and amino acid metabolism were activated, while in the heart, lactate metabolism and fatty acid oxidation pathways were up-regulated, likely reflecting the heart’s energy requirements. Despite these tissue-specific variations, similar gene regulation patterns across tissues suggest common participation in overlapping metabolic pathways. These findings highlight the role of mitochondrial gene expression in amino acid metabolism and provide a foundation for further research on mitochondrial function. This knowledge can inform breeding and nutritional strategies for livestock, enhancing both productivity and welfare. Additionally, our ongoing work aims to bridge the gap between RNA expression and protein levels through integrated transcriptomic and proteomic analyses, contributing to a better understanding of nutrient utilization in farm animals and potential therapeutic approaches for human metabolic diseases.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We extend our appreciation to the Science and Engineering Research Board, a part of the Department of Science and Technology under the Government of India, for financially supporting this endeavor. The authors wish to convey their thanks to the Director of ICAR-National Dairy Research Institute for enabling the essential resources to carry out this study.

Author contributions

The project’s conception and experimental design were spearheaded by SEM. SEM executed the experiments, conducted data analysis, and initiated manuscript drafting alongside MSL. All authors critically reviewed and granted their approval for the final manuscript version.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Science and Engineering Research Board, Department of Science and Technology, Government of India, EEQ/2017/00445.

Data availability

Data generated from this study are presented in the manuscript. Further details are presented in additional supplementary files. The information not included would be shared by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

No endorsement from research ethics committees was deemed necessary to achieve the objectives of this study, as the experimental procedures were carried out using post-slaughter tissues of buffalo specimens.

Consent to participate

This article does not contain any person’s data in any form.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed to publish the research in this journal.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alves A, Bassot A, Bulteau AL, Pirola L, Morio B (2019) Glycine metabolism and its alterations in obesity and metabolic diseases. Nutrients 11(6):1356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltazar P, de Melo Junior AF, Fonseca NM, Lança MB, Faria A, Sequeira CO, Pereira SA (2023) Oxalate (dys) metabolism: person-to-person variability, kidney and cardiometabolic toxicity. Genes 14(9):1719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bequette BJ (2003) Amino acid metabolism in animals: an overview. Amino acids in animal nutrition. CABI Publishing, pp 87–101. 10.1079/9780851996547.0087 [Google Scholar]

- Biswas D, Duffley L, Pulinilkunnil T (2019) Role of branched-chain amino acid–catabolizing enzymes in intertissue signaling, metabolic remodeling, and energy homeostasis. FASEB J 33(8):8711–8731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer SH, Fainer DC, Watson-Williams EJ (1963) Lactate dehydrogenase variant from human blood: evidence for molecular subunits. Science 141(3581):642–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchalski B (2019) The impact of redox stress in primary hyperoxaluria type 1. Doctoral dissertation, The University of Alabama at Birmingham

- Chen Q, Zhang L, Chen S, Huang Y, Li K, Yu X, Wu H, Tian X, Zhang C, Tang C, Du J, Jin H (2016) Downregulated endogenous sulfur dioxide/aspartate aminotransferase pathway is involved in angiotensin II-stimulated cardiomyocyte autophagy and myocardial hypertrophy in mice. Int J Cardiol 225:392–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J (2018) FASTP: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34:i884–i890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban-Martínez L, Sierra-Filardi E, Boya P (2017) Mitophagy, metabolism, and cell fate. Mol Cell Oncol. 10.1080/23723556.2017.1353854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Vizarra E, Enríquez JA, Pérez-Martos A, Montoya J, Fernández-Silva P (2011) Tissue-specific differences in mitochondrial activity and biogenesis. Mitochondrion 11(1):207–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filosto M, Scarpelli M, Cotelli MS, Vielmi V, Todeschini A, Gregorelli V, Padovani A (2011) The role of mitochondria in neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurol 258:1763–1774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomello M, Pyakurel A, Glytsou C, Scorrano L (2020) The cell biology of mitochondrial membrane dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 21(4):204–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianmoena K (2017) Metabolic alterations in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): consequences of AGXT downregulation on glyoxylate detoxification. 10.17877/DE290R-18100

- Gianmoena K, Gasparoni N, Jashari A, Gabrys P, Grgas K, Ghallab A, Cadenas C (2021) Epigenomic and transcriptional profiling identifies impaired glyoxylate detoxification in NAFLD as a risk factor for hyperoxaluria. Cell Rep. 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guda P, Guda C, Subramaniam S (2007) Reconstruction of pathways associated with amino acid metabolism in human mitochondria. Genom Proteom Bioinform 5:166–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassinen IE (2014) Mitochondria and energy metabolism: Networks, mechanisms, and control. Natural Biomarkers for Cellular Metabolism: Biology, Techniques, and Applications. CRC Press, pp 3–40. 10.1201/b17427 [Google Scholar]

- Henriques BJ, Olsen RKJ, Gomes CM, Bross P (2021) Electron transfer flavoprotein and its role in mitochondrial energy metabolism in health and disease. Gene 776:145407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks KG, Cluntun AA, Schubert HL, Hackett SR, Berg JA, Leonard PG, Rutter J (2023) Protein-metabolite interactomics of carbohydrate metabolism reveal regulation of lactate dehydrogenase. Science 379(6636):996–1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui S, Ghergurovich JM, Morscher RJ, Jang C, Teng X, Lu W, Rabinowitz JD (2017) Glucose feeds the TCA cycle via circulating lactate. Nature 551(7678):115–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson SM, Sweatt AJ, Lanoue KF (2005) Branched-chain [corrected] amino acid metabolism: implications for establishing safe intakes. J Nutr 135(Suppl 6):1557S-1564S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infantino V, Dituri F, Convertini P, Santarsiero A, Palmieri F, TodiscoIacobazzi SV (2019) Epigenetic upregulation and functional role of the mitochondrial aspartate/glutamate carrier isoform 1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta (BBA) Mol Basis Dis 1:38–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javadov S, Kozlov AV, Camara AK (2020) Mitochondria in health and diseases. Cells 9(5):1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappler L, Hoene M, Hu C, von Toerne C, Li J, Bleher D, Lehmann R (2019) Linking bioenergetic function of mitochondria to tissue-specific molecular fingerprints. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 10.1152/ajpendo.00088.2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, Salzberg SL (2019) Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol 37(8):907–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight J, Holmes RP, Milliner DS, Monico CG, Cramer SD (2006) Glyoxylate reductase activity in blood mononuclear cells and the diagnosis of primary hyperoxaluria type 2. Nephrol Dial Transpl 21(8):2292–2295. 10.1093/ndt/gfl142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knol MG, Wulfmeyer VC, Müller RU, Rinschen MM (2024) Amino acid metabolism in kidney health and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 20 (12): 771–788. 10.1038/s41581-024-00872-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Hoppe T (2023) Role of amino acid metabolism in mitochondrial homeostasis. Front Cell Dev Biol 11:1127618. 10.3389/fcell.2023.1127618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Yang Y, Zhang B, Lin X, Fu X, An Y, Yu T (2022) Lactate metabolism in human health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther 7(1):305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling ZN, Jiang YF, Ru JN, Lu JH, Ding B, Wu J (2023) Amino acid metabolism in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther 8(1):345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Li Y, Chen G, Chen Q (2023a) Crosstalk between mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis. J Biomed Sci 30(1):86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Li X, Zhou H (2023b) Changes in glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase 2 during rat physiological and pathological cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 23(1):595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson M, Wang TJ, Clish C, Engström G, Nilsson P, Gerszten RE, Melander O (2015) Dimethylglycine deficiency and the development of diabetes. Diabetes 64(8):3010–3016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann G, Mora S, Madu G, Adegoke OA (2021) Branched-chain amino acids: catabolism in skeletal muscle and implications for muscle and whole-body metabolism. Front Physiol 12:702826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Reyes I, Chandel NS (2020) Mitochondrial TCA cycle metabolites control physiology and disease. Nat Commun 11:102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra P, Chan DC (2016) Metabolic regulation of mitochondrial dynamics. J Cell Biol 212:379–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri F, Scarcia P, Monné M (2020) Diseases Caused by Mutations in Mitochondrial Carrier Genes SLC25: A Review. Biomolecules 10(4):655. 10.3390/biom10040655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard M, McEwen BS, Epel ES, Sandi C (2018) An energetic view of stress: focus on mitochondria. Front Neuroendocrinol 49:72–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasun P (2020) Mitochondrial dysfunction in metabolic syndrome. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta (BBA) Mol Basis Dis 1866(10):165838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protasoni M, Zeviani M (2021) Mitochondrial structure and bioenergetics in normal and disease conditions. Int J Mol Sci 22(2):586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan R, Mancini RA, Konda MR (2009) Effects of lactate on beef heart mitochondrial oxygen consumption and muscle darkening. J Agric Food Chem 57(4):1550–1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK (2010) edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26(1):139–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth JA, Tuggle CK (2015) Livestock models in translational medicine. ILAR J 56(1):1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeesh EM, Malik A (2024) Deciphering tissue-specific expression profiles of mitochondrial genome-encoded tRNAs and rRNAs through transcriptomic profiling in buffalo. Mol Biol Rep 51(1):876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeesh EM, Singla N, Lahamge MS, Kumari S, Ampadi AN, Anuj M (2023) Tissue heterogeneity of mitochondrial activity, biogenesis and mitochondrial protein gene expression in buffalo. Mol Biol Rep 50(6):5255–5266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeesh EM, Lahamge MS, Malik A, Ampadi AN (2024a) Nuclear genome-encoded mitochondrial OXPHOS complex I genes in female buffalo show tissue-specific differences. Mol Biotechnol. 10.1007/s12033-024-01206-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeesh EM, Lahamge MS, Malik A, Singh P (2024b) Differential expression of nuclear-derived mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase genes in metabolically active buffalo tissues. Mol Biol Rep 51(1):1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeesh EM, Lahamge MS, Malik A, Ampadi AN (2025a) Differential expression of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein genes of ATP synthase across different tissues of female buffalo. Mol Biotechnol 67(2):705–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeesh EM, Lahamge MS, Kumari S, Singh P (2025b) Tissue-specific diversity of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes related to lipid and carbohydrate metabolism in buffalo. Mol Biotechnol. 10.1007/s12033-025-01386-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastián D, Zorzano A (2018) Mitochondrial dynamics and metabolic homeostasis. Curr Opin Physiol 3:34–40. 10.1016/j.cophys.2018.02.006 [Google Scholar]

- Sharma G, Duarte S, Shen Q, Khemtong C (2024) Analyses of mitochondrial metabolism in diseases: a review on 13C magnetic resonance tracers. RSC Adv 14(51):37871–37885. 10.1039/d4ra03605k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercellino I, Sazanov LA (2022) The assembly, regulation and function of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 23(2):141–161. 10.1038/s41580-021-00415-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Ying W, Dunlap KA, Lin G, Satterfield MC, Burghardt RC, Wu G, Bazer FW (2014) Arginine decarboxylase and agmatinase: an alternative pathway for de novo biosynthesis of polyamines for development of mammalian conceptuses. Biol Reprod 90(4):84. 10.1095/biolreprod.113.114637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe RR, Church DD, Ferrando AA, Moughan PJ (2024) Consideration of the role of protein quality in determining dietary protein recommendations. Front Nutr 11:1389664. 10.3389/fnut.2024.1389664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Zhu T, Huang Y, Fang Z, Luo F (2023) Current understanding of the contribution of lactate to the cardiovascular system and its therapeutic relevance. Front Endocrinol 14:1205442. 10.3389/fendo.2023.1205442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Khunsriraksakul C, Eales JM, Markus H, Wang L, Saluja S, Lay A, Guzik TJ, Morris AP, Liu DJ, Charchar FJ, Tomaszewski M (2023) S-22-3: Uncovering new genes, tissues, and therapeutic targets for blood pressure through large-scale transcriptomewide association studies. J Hypertens 41(Suppl 1): p e53–e54. 10.1097/01.hjh.0000913236.67510.8138164960 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data generated from this study are presented in the manuscript. Further details are presented in additional supplementary files. The information not included would be shared by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.