Abstract

Background

Ossifying fibroma (OF) is a non-common benign fibrous-osseous lesion with highly aggressive behavior and tends to recur. Here, we report a case where Ossifying Fibroma (OF) was diagnosed in an adolescent female patient and was treated by marginal mandibular resection to avoid esthetic and functional defects in the future.

Case presentation

OF was diagnosed in a 13-year-old woman incidentally. Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) examination showed a hypodense lesion compromising the vestibular table and 34 and 35 teeth. An incisional biopsy was performed to determine the histopathological diagnosis. After a multidisciplinary consensus, tooth extraction and surgical resection of the lesion were done. In the same way, bone reconstruction using the Khoury technique with an autologous graft of an external oblique line and with a mixture of autogenous and allogenic bone and fixation screws. Clinical and imaging follow-ups after 1, 4, 15, and 23 months were included, evidencing integration of the grafts in the treated zone.

Conclusions

OF early identification and treatment are essential to minimize risks of losing tissues in young people. Also, to avoid negative consequences in the people´s quality of life associated with bone and teeth loss. This highlights the importance of radiographic surveillance, analyses, and interdisciplinary collaboration to optimize clinical outcomes in patients with similar conditions.

Keywords: Fibroma, Ossifying, Alveolar ridge augmentation, Incidental finding, Bone transplantation

Background

Ossifying fibroma (OF) is an uncommon benign fibrous-osseous lesion with highly aggressive behavior and tends to recur [1]. Most cases appear in women in an age range between the third and the fourth decades. The mandible is most commonly affected, with premolar and molar areas being predominantly involved [2, 3]. The larger lesions can potentially induce expansion of the mandibular tables, thus generating facial asymmetry in the patient. This phenomenon is accompanied by pain and, in some cases, can cause resorption and displacement of adjacent teeth affected by the lesion [2, 4].

Diagnosis of OF is based on clinical symptomatology, determined by the lesion size and evident intraoral or facial asymmetry. However, incidental findings could occur in routine radiographic analysis without clinical signs or symptoms. During the incidental finding, OF usually has a size range between 1 and 5 cm in diameter [2]. However, previous reports showed OF lesions in the initial stages have not been reported. Due to the aggressive behavior of these lesions, clinical management of incidentally diagnosed OF is critical to preserve the tissues adequately. OF tends to grow into large size, resulting in facial alterations, pain, and paresthesia if not managed in time [5]. The main goal of this study was to present an incidental OF with an early diagnosis and surgical treatment to maintain the alveolar ridge in young women for future definitive treatment.

Case presentation

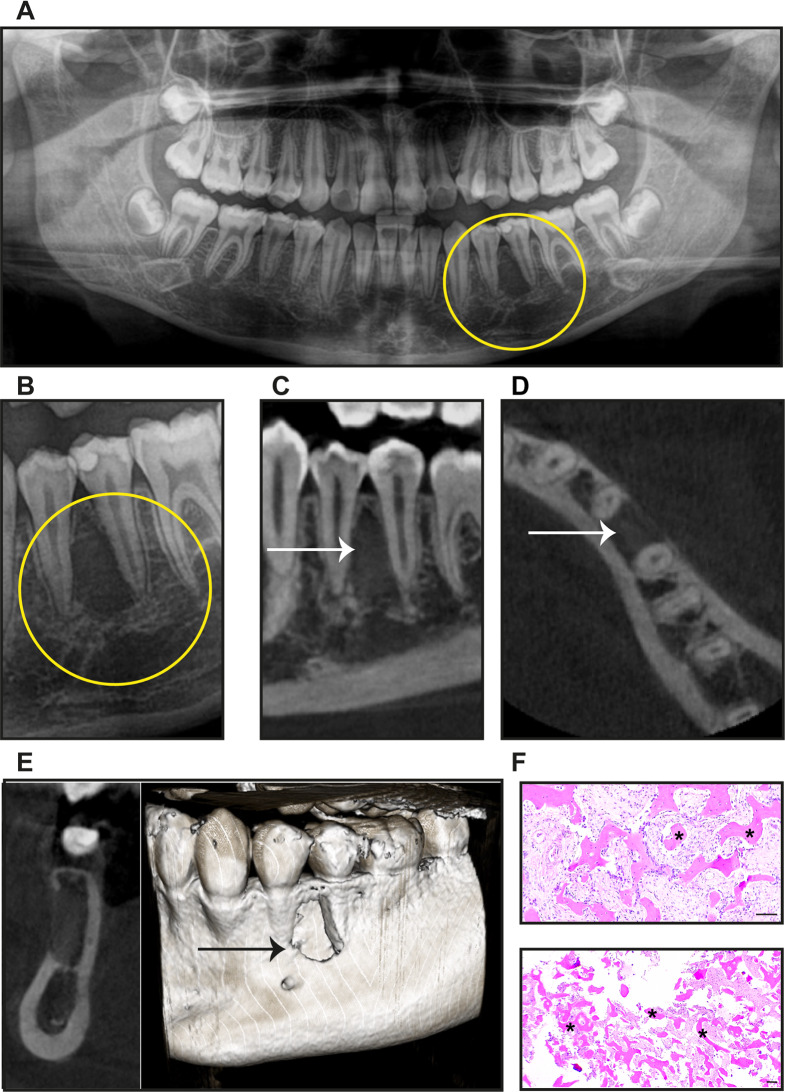

We present a case of a 13-year-old female, Caucasian, systemically healthy (ASA 1), who presented to our clinic asking for evaluation and treatment for a diagnosis derived from another office. Our clinical examination was not remarkable for any evident bony expansion, pain, or paresthesia. The patient did have a panoramic radiograph on which we observed a round radiolucent lesion (approximately 8 × 3 mm), with regular and well-defined edges, in between the premolars 34 and 35, and was significant for loss of bone distal to 34 and mesial to 35 (Fig. 1A, B). Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) was requested and was significant for showing a hypodense lesion compromising the vestibular table and was approximately 5.5 mm wide, 14 mm high, and 5 mm deep buccolingually (Fig. 1C, D, E). Endodontic evaluation of teeth 34 and 35 was remarkable for the positive response to both heat and cold tests and without any symptoms on vertical and horizontal percussion. According to the CBCT images and the clinical examination, our differential diagnosis included Lateral periodontal cyst, Keratocyst, Ameloblastoma, Central giant cell granuloma, Initial focal cemento-osseous dysplasia, and Ossifying fibroma. Radicular cyst diagnosis was discarded due to the positive response to the thermal tests in both 34 and 35. An incisional biopsy was performed, and histological analyses demonstrated the presence of vital radicular bone with osteoblasts in multiple trabeculae and fibrous connective tissue (Fig. 1F). All these characteristics were compatible with the diagnosis of Osseous Fibroma.

Fig. 1.

Incidental detection of Ossifying fibroma. (A) Representative image of the panoramic radiography, yellow circle indicating the lesion (B) Close-up of the lesion area between 34 and 35 teeth. Representative images of the Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (C) Axial, (D) Transversal, (E) Sagittal and superficial images of the lesion indicated by the arrow. (E) Representative images of histological sections of the initial biopsy; the bone trabeculae indicate asterisks. Scale Bar 200 μm

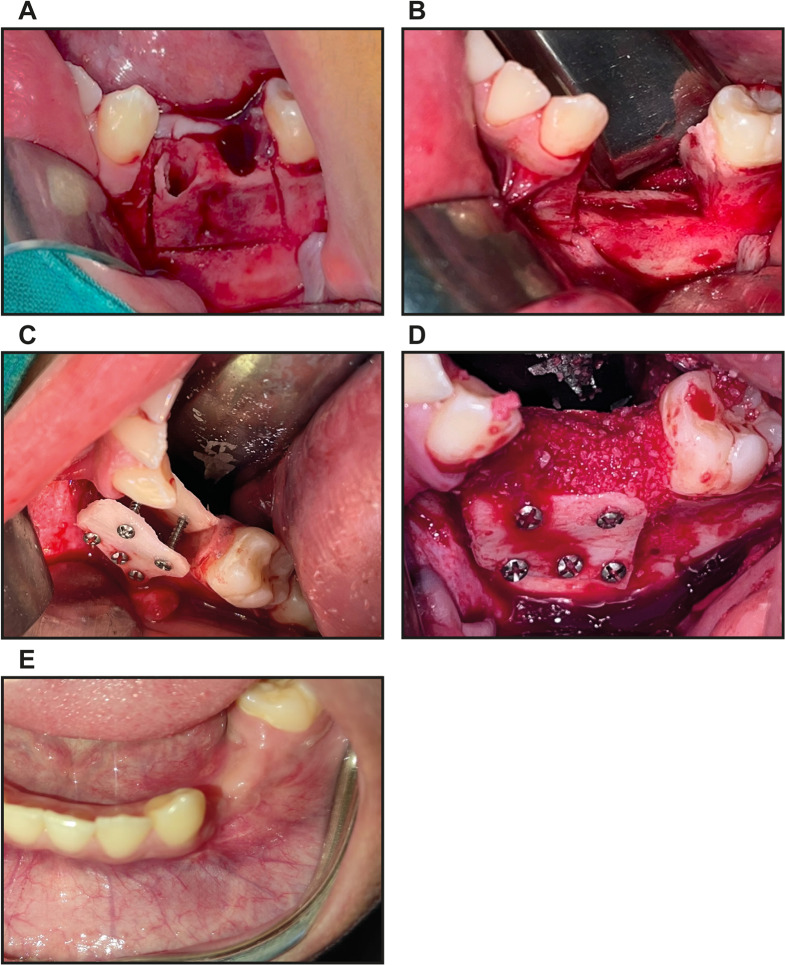

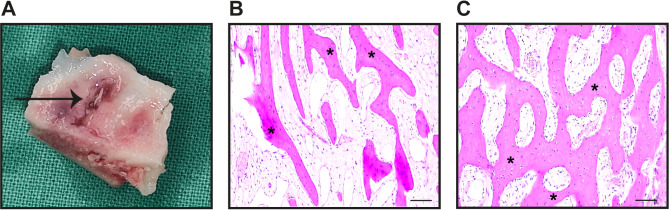

After a multidisciplinary consensus, the lesion resection was planned, including the 34 and 35 tooth extractions and treatment for the alveolar ridge reconstruction due to the patient’s age and bone regeneration capacity. In the same surgical procedure, tooth extraction and a marginal mandibular resection with a piezoelectric instrumental were performed to preserve the integrity of the inferior alveolar nerve (Fig. 2A, B). The Khoury technique was performed to reconstruct the alveolar ridge in width and height [6]. According to this surgical technique, an autologous graft of an external oblique line of 16 × 15 mm was taken to form two thin bone sheets that were subsequently stabilized from the lingual and vestibular ridges using 1.5 system fixation screws. The space generated between both blocks was filled with a 1:1 mixture of autograft + allograft Oragraft (Life Net Health, Virginia, USA). The surgical bed was covered by a 25 × 30 mm Ossix Pluss collagen membrane (Dentsply, Sirona Charlotte, NC, USA) (Fig. 2C, D). Finally, to reduce the tension in the wound bed, a lingual flap was created, with the removal of the mylohyoid muscle insertion for the traction of the alveolar mucosa and to achieve adequate healing of the area successfully. During this surgery, the mesial root of the first molar on the lower left was accidentally sectioned, which was considered among the possible risks of the surgery. However, the patient was referred to endodontics for evaluation. Vicryl 4 − 0 suture (Ethicon, NJ, USA) was used to close the wound, and seven days after the surgery, the suture was removed. After one month, a clinical follow-up was made, evidencing excellent soft tissue healing and preserving the support structures of the adjacent teeth (Fig. 2E). The sectioned mandibular block recovered after the lesion resection (Fig. 3A) was immersed in buffered formalin and then embedded in paraffin to get histological sections. After histopathological analyses, the diagnosis of Ossifying Fibroma was confirmed due to abundant trabeculae with lamellar bone, including osteocytes, osteoblasts, and fibrous connective tissue (Fig. 3B, C).

Fig. 2.

Ossifying fibroma resection and surgical treatment of the area. Images of the surgical procedure to resect and treat the lesion area. (A) Alveolar ridge after 34 and 35 tooth extraction. (B) Piezoelectric marginal mandibular resection. (C) Vestibular and lingual ridge reconstruction with autografts and using 1.5 system fixation screws. (D) Space between vestibular and lingual ridge blocks was filled with a 1:1 mixture of autograft allograft. (E) Clinical follow-up one month after surgery

Fig. 3.

A biopsy of the resected lesion confirms the Ossifying fibroma diagnosis. Representative Images of the resected lesion (A) and histological sections showing bone trabeculae indicated with asterisks at lower (B) and (C) higher magnification Scale Bar 200 μm

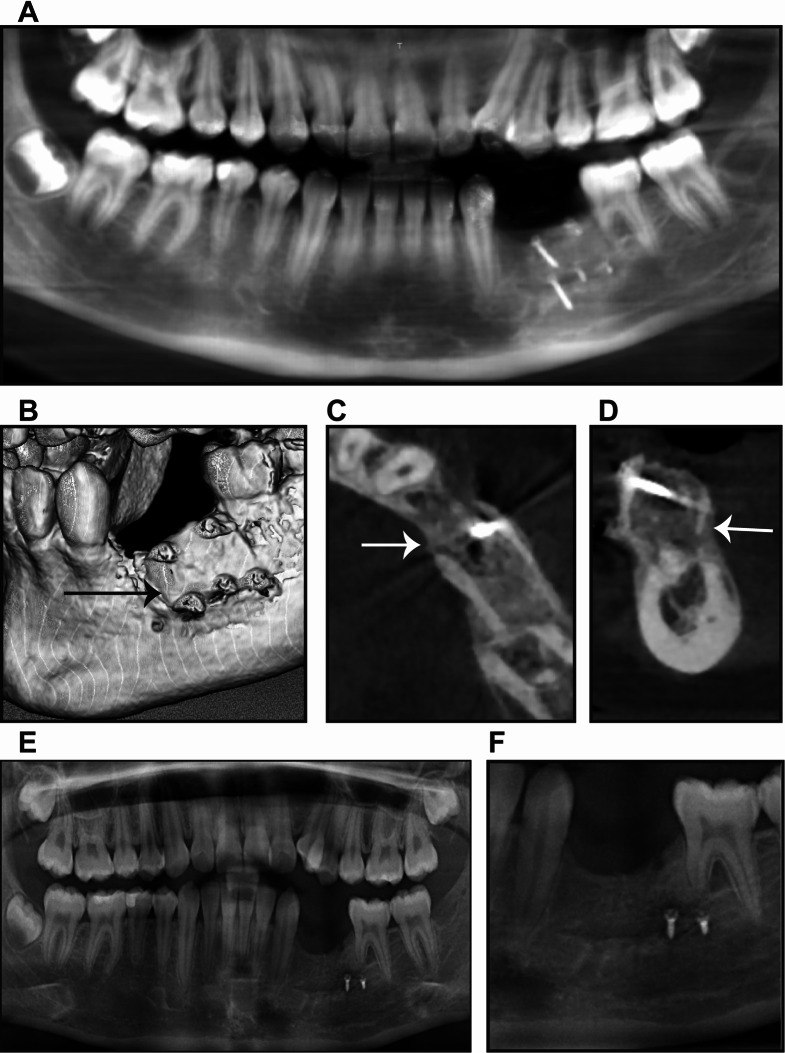

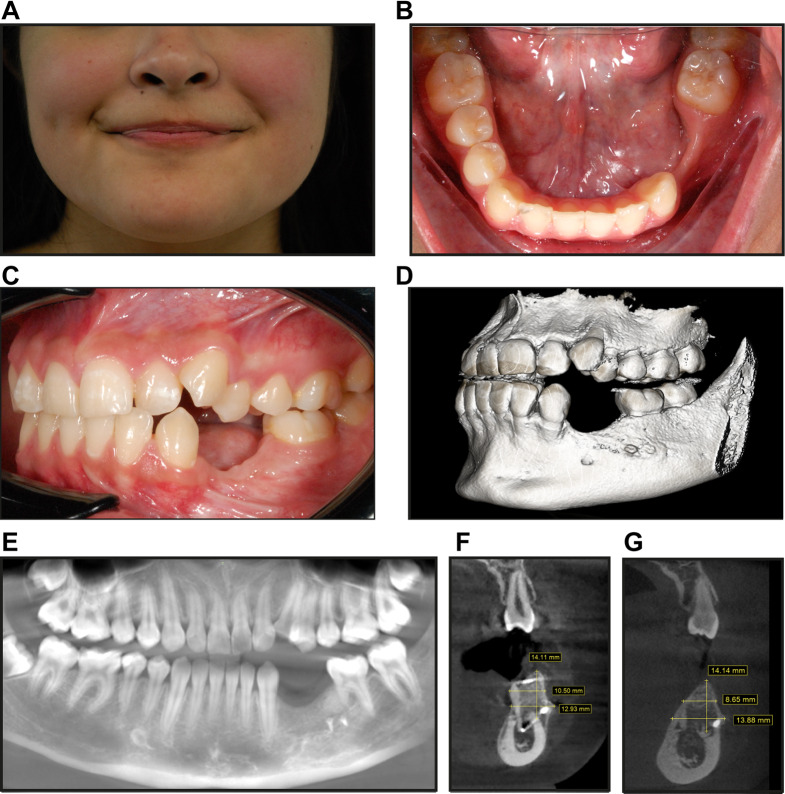

The patient was followed up, and after four months, a control cone-beam computed tomography was taken. Images evidenced graft integration in the surgical site, and the screws used to localize the graft were in the same position as at the time of the surgical intervention (Fig. 4A-D). At a subsequent follow-up fifteen months after surgery, the patient presented with discomfort in the vestibular mucosa, and for that reason, three screws were taken out. A panoramic radiograph showed good integration and preservation of the grafts and adequate adjacent periodontal support on adjacent teeth. (Fig. 4E, F). Finally, a clinical exam and CBCT were done twenty-three months after surgery. Clinically, both soft and hard tissues were found to have healed. However, some alterations in the teeth’ position were observed (Fig. 5A-E). The patient is being worked up for orthodontic treatment, and we are considering future implanted-based rehabilitation as the definitive treatment. In the CBCT images taken twenty-three months after surgery, we observed the alveolar ridge’s graft preservation and excellent stability (Fig. 5D, E). We observed approximately the same length (14 mm) and a bone loss in the width dimension of approximately 2 mm, particularly at the most cervical part of the ridge (Figs. 5F and G and 10.5 mm at four months vs. 8.65 mm after twenty-three months). At this time, the endodontic evaluation showed 36 positive responses to the thermal tests. However, the patient will be followed up during the orthodontic treatment to evaluate the vitality of this tooth.

Fig. 4.

Four- and fifteen-month follow-up of the patient. Representative images of the Cone-Beam Computed Tomography after four months of the Ossifying fibroma resection and treatment. (A) Panoramic view Arrows indicate the graft integration in the treated area. (B) Three-dimensional reconstruction, (C) transversal, and (D) sagittal views. (E-F) Panoramic radiography taken fifteen months after surgery

Fig. 5.

Twenty-three-month follow-up of the patient. Clinical images of patient evaluation: (A) Extraoral front view (B) Intraoral occlusal view (C) Intraoral lateral view in occlusion. (D-E) CBCT images Twenty-three months after the surgery. CBCT representative images of the length and width of alveolar ridge dimensions mesial to the first mandibular molar show the grafts’ preservation. (F) Four months after surgery, and (G) Twenty-three months after surgery

Discussion and conclusions

Ossifying fibroma is a benign lesion with a good prognosis in adults. However, it is highly likely to recur in children or young individuals [7]. According to the 2017 WHO classification, ossifying fibroma could include other lesions, such as trabecular juvenile ossifying fibroma and psammomatoid juvenile ossifying fibroma. Both are characterized by being aggressive and present in the youth population. In the case of Trabecular Juvenile Ossifying Fibroma, it occurs more frequently in the maxilla than in the mandible. It is characterized by presenting elongated trabeculae of osteoid tissue in the histological analyses.

On the other hand, the Psammomatoid Juvenile Ossifying Fibroma occurs more frequently outside the maxillary bones, in the paranasal sinuses, the orbit and base of the skull, and rarely in the maxilla or mandible [8]. Histologically, it is characterized by psammoma bodies, which are concentric or lamellar ossicles that contain osteocytes [9]. Both juvenile variants of ossifying fibroma are rare, usually present before age 15, and are more common in female patients. They are benign tumors that exhibit aggressive behavior and have a high recurrence rate. However, in the case reported, the clinical-pathological findings are compatible with OF [4, 5, 10].

The therapeutic approach of OF in children remains controversial. Previous reports have suggested a treatment based on curettage and enucleation as the first treatment choice in the presence of well-defined and smaller lesions [5, 11, 12]. Titinchi et al. [11] analyzed the different treatments of an ossifying fibroma and evaluated its recurrence, finding only one case of recurrence after six years of curettage and enucleation treatment. However, other studies have recommended mandibular resection in cases where the ossifying fibroma is aggressive, showing expansion or perforation of bone tables, pain, and a rapid increase in size [5, 11, 12].

On the other hand, Liu et al. reported 28.6% of the OF recurrence after curettage, while radical resection was 3.8%. Similarly, in cases where the lesion limits were not well defined, recurrence was higher by approximately 50% [7]. In the case reported, after an interdisciplinary analysis and considering the patient and their family preferences, mandibular resection was performed, including extraction of involved premolars. According to the evidence, mandibular resection for treating OF in children or adolescents could be the best treatment alternative, considering the difficulty of determining the extent of spread /and avoiding recurrence. There is insufficient evidence in the literature to support the best treatment for ossifying fibromas in the early stages [4]. This case was managed more aggressively and included reconstruction using the Khoury surgical technique. Dr. Fouad Khoury described this technique for the first time in 2003 as an alternative to treat the loss of bone volume in both thickness and height. Previous studies have reported approximately 5 mm of gain in bone height using this treatment technique [13].

OF, despite being a benign lesion, has a high tendency to recur and may exhibit aggressive behavior, especially in children. Early detection and appropriate surgical management could prevent possible future complications. It is essential to determine adequate rehabilitation treatments and avoid adverse effects on the patient´s quality of life. The reported case shows the early clinical and imaging features of ossifying fibroma. The patient was followed for one, four, fifteen, and twenty-three months, evidencing good graft stability and excellent soft tissue healing. In the last CBCT, taken twenty-three months after surgery, no evidence of residual/recurrent lesion could be noted. Also, no radiolucent areas were detected around the tooth root sectioned accidentally during the surgery in the 36-tooth molar.

In conclusion, early identification and treatment of ossifying fibroma are essential to minimize risks related to tissue loss in young people and provide better clinical outcomes in the future. They also avoid negative consequences in people´s quality of life associated with bone and tooth loss. This highlights the importance of radiographic surveillance, analyses, and interdisciplinary collaboration to optimize clinical outcomes in patients with similar conditions.

Author contributions

Conception and design: MS, PR. Administrative support: MS, PR, SE, AC. Provision of study materials or patients: MS, PR. Data collection and assembly: MS, PR, SE, AC, CMC. Data analysis and interpretation: MS, PR, SE, AC, CMC, Manuscript writing, and Final approval of manuscript: MS, PR, SE, AC, CMC.

Funding

There was no funding for this case report.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

A signed informed consent form from the patient’s mother and her assent was obtained for all procedures. The Ethic Scientific Committee of the Universidad de los Andes, Chile approved this consent.

Consent for publication

A signed informed consent form from the patient’s mother and her assent was obtained for the case report publication. The Ethic Scientific Committee of the Universidad de los Andes, Chile approved this consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Martín Alberto Sánchez Varela, Email: masanchez@uandes.cl.

Constanza Martínez-Cardozo, Email: cemartinezc@uandes.cl.

References

- 1.Kaur T, Dhawan A, Bhullar RS, Gupta S. Cemento-Ossifying Fibroma in Maxillofacial Region: a Series of 16 cases. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2021;20:240–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mainville G, Turgeon D, Kauzman A. Diagnosis and management of benign fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws: a current review for the dental clinician. Oral Dis. 2017;23:440–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neville Brad W, DDD. ACM and CAC. Bone Pathology. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Elsevier; 2024. pp. 618–84.

- 4.Crane H, Walsh H, Hunter KD. Fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws. Diagn Histopathol. 2024;30:170–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohanty S, Gupta S, Kumar P, Sriram K, Gulati U. Retrospective analysis of ossifying Fibroma of Jaw bones over a period of 10 years with Literature Review. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2014;13:560–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khoury F, Hanser T. Mandibular bone Block Harvesting from the Retromolar Region: a 10-Year prospective clinical study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2015;30:688–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Shan X-F, Guo X-S, Xie S, Cai Z-G. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of ossifying Fibroma in the Jaws of children: a retrospective study. J Cancer. 2017;8:3592–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hameed M, Horvai AE, Jordan RCK. Soft tissue Special Issue: Gnathic Fibro-Osseous lesions and Osteosarcoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2020;14:70–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon Y, Shin D, Kim J, Lee M, Choi H. Juvenile psammomatoid ossifying fibroma of the maxilla. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2020;21:193–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.San Martín MJT, Andrade DJT, Baeza AM, de los Á, Toro AC. Fibroma Osificante Juvenil, presentación de un caso clínico y revisión de la literatura. Revista De otorrinolaringología y cirugía de cabeza y cuello. 2014;74:49–53. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Titinchi F, Morkel J. Ossifying Fibroma: analysis of treatment methods and recurrence patterns. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74:2409–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Triantafillidou K, Venetis G, Karakinaris G, Iordanidis F. Ossifying fibroma of the jaws: a clinical study of 14 cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:193–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sánchez-Sánchez J, Pickert FN, Sánchez-Labrador L, GF Tresguerres F, Martínez-González JM. Meniz-García C. Horizontal Ridge Augmentation: a comparison between Khoury and urban technique. Biology (Basel). 2021;10:749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.