Abstract

Limonene oxide, which is produced from limonene epoxidation, is a valuable molecule that can be applied in flavor, fragrance, and renewable polymer applications. A catalytic reaction system using H2O2 with γ-Al2O3 and ethyl acetate (EtOAc) as the solvent has been explored as an effective system for this reaction. In these previous studies, a number of postulates have been proposed as to how water affects the reaction; therefore, the focus of this work is to elucidate the role of water in limonene epoxidation. While not impacting the selectivity to limonene oxide, the amount of water in the reaction system is shown to significantly impact the limonene reactivity. Furthermore, through both addition of excess water and removal of water with a Dean–Stark apparatus, the control of the H2O2/H2O ratio is demonstrated to be the primary factor controlling reactivity. In contrast, changes in limonene concentrations for a specific H2O2/H2O ratio are shown to have little impact on the reaction rate. This study shows that the competitive adsorption of H2O2 and water on the catalyst surface is key in explaining the water impact on the reaction performance.

Keywords: limonene oxidation, limonene oxide, limonene derivatives, hydrogen peroxide, alumina

Introduction

Limonene is a molecule that can be directly obtained from industrial food waste or synthesized through microorganism engineering.1,2 It can be utilized as a fragrance or further converted into valuable downstream products, including p-cymene,3p-menthane,4 and terephthalic acid.5 With increasing interest in renewable fuels and chemicals, terpene-derived chemicals can be a potential approach. Among limonene derivatives, oxidation products are a category with high potential for both existing commercial chemicals and chemicals with novel applications.6 An oxidation/hydroxylation network from limonene to some valuable derivatives is shown in Scheme 1. These compounds can be further used as flavors,7 fragrances,8 cosmetics,9 pharmaceuticals,10 and biobased polymers.11,12

Scheme 1. Reaction Network from Limonene to Oxidized Derivatives.

Among the molecules shown in Scheme 1, perillyl alcohol, carvone, and carveol can be generated from limonene, but effective ways to produce them through chemical synthesis still require development. Limonene oxide has received attention recently as a renewable monomer.13 Kindermann et al. showed a sequential method to produce poly limonene dicarbonate from limonene oxide.14 Hauenstein et al. also demonstrated a biobased polycarbonate synthesis method with subsequent examination of the polymer physical properties.15,16 Carrodeguas et al. synthesized a recyclable copolymer with limonene oxide and other bioderived monomers.17 Limonene oxide is also a flavoring agent and an intermediate molecule to access other oxidized derivatives, as shown in Scheme 1, making it valuable as a platform molecule. As the interest in limonene derivatives continues to increase, a low-cost and effective limonene oxide production process would be the foundation for further product development.

Limonene epoxidation has been reported with various heterogeneous catalysts. Oliveira et al. conducted limonene oxidation with V2O5/TiO2 catalysts. A range of byproducts such as carvone, limonene-1,2-diol, and oligomers were observed.18 Cagnoli et al. proposed limonene epoxidation with a Ti-MCM-41 catalyst and 35 wt % H2O2(aq). They obtained over 20% selectivity to carveol or carvone when 50% of the limonene was converted.19 More recently, Ivanchikova et al. prepared a Nb/SiO2 catalyst and screened several alkene epoxidations. With 50 wt % H2O2(aq), 73% selectivity to limonene epoxide was achieved.20 Bisio et al. synthesized a W/SiO2 catalyst and applied it to obtain a 43% yield of limonene oxide at 90 °C after 6 h.21 Wróblewska et al. studied the oxidation reaction with a microporous titanium silicate catalyst, TS-1.22 Interestingly, perillyl alcohol was the primary byproduct under certain conditions, which suggested that structural effects might benefit from this unique selectivity. Overall, these studies found a range of byproducts, such as carvone, carveol, limonene diol, or perillyl alcohol, at higher limonene conversions. The byproducts were reported to be formed by the high reactivity of activated H2O2 or due to high water concentration generated in the reaction system. To address this challenge, several groups developed novel catalysts or reaction systems to approach higher overall limonene oxide yields with higher reaction rates. Cunningham et al., using a multiphasic catalytic system to avoid water, reported a 94% isolated yield of limonene oxide.23 Ardagh et al. employed controlled silica layer deposition on a Ti-SiO2 catalyst to impact the local environment around active sites to change the activation energy without altering the intrinsic active site.24 Kaliaguine’s group developed epoxidation with intermediate oxidants and applied ultrasound to conduct the reaction.25−27

In addition to these approaches, recent work demonstrated that a high overall selectivity could be achieved by reducing water in the system. Bono et al. performed epoxidation in ethyl acetate (EtOAc) with γ-Al2O3 and 70% H2O2(aq).28,29 After optimization, nearly complete conversion to limonene dioxide was reported. This work suggested that selective conversion in the condensed phase with highly concentrated H2O2 is possible. Continuous water removal in a Dean–Stark apparatus was found to improve reactivity and selectivity for epoxidation.30 Using the Dean–Stark system, a combined limonene oxide and dioxide yield of 77% was obtained.31 Alternatively, Charbonneau and Kaliaguine used a Ti-SBA-16 catalyst with tert-butyl hydroperoxide as the oxidant in decane to prevent diol formation.32 While these studies demonstrated the improved final yield performance when water was reduced, understanding of how the remaining water participated in the reaction was still unclear. Additionally, it is critical to understand how the H2O2 concentration affects the reaction, since various concentrations have been used in the literature.

A number of mechanisms have been proposed in the literature for how water participates in the catalytic reaction including (i) water hydroxylates the catalyst surface, which changes the nature of the acidity of catalyst;33 (ii) the presence of water affects the diffusion rate of the organic reactant into smaller pores;34 (iii) water forms hydroxyl groups on the surface and hydrogen bonding between water molecules, and these hydroxyl groups interrupt the organic species adsorption;35 (iv) excess water reacts with the epoxide to form the diol byproduct;36,37 (v) water and the hydrophilic Al2O3 support aggregate to form clusters that affect mixing,30 and (vi) competitive adsorption between H2O2 and water.38 To further optimize the reaction system, the role of water must be better understood. This work examined water in the reaction system using commercial γ-Al2O3 and various water or H2O2 concentrations. The impact of the H2O2/H2O ratio on the reactivity was used to evaluate the proposed mechanisms above.

Experimental Methods

Reagents and Materials

Limonene (Alfa Aesar, 97%), limonene oxide (Sigma-Aldrich, 97%), limonene-1,2-diol (Sigma-Aldrich, 97%), carvone (Sigma-Aldrich, 98%), carveol (Sigma-Aldrich, 95%), γ-Al2O3 (Inframat Advanced Materials), 50 wt % H2O2(aq) (Honeywell), acetic acid (Fisher Scientific, glacial), formic acid (Fisher Scientific), potassium iodide (Fisher Scientific), and sodium thiosulfate (Acros Organics, 0.1 N solution) were used as received.

Reaction Setup

The limonene epoxidation reaction was first conducted in a glass vial reactors. In a typical run, 25.0 mg of γ-Al2O3, as the catalyst, was loaded into the vials. Then, 2.0 mL of EtOAc, 0.62 mmol of limonene, and the desired H2O2 were added sequentially. The reaction temperature used for the close vial runs was 80 °C to keep the pressure relatively low. After the reaction, the solution was analyzed with a GC-MS/FID system to quantify the products. For the reflux reaction runs, a round-bottom flask with a reflux column or Dean–Stark apparatus was used. For these runs, the volume was increased by 10-fold, 20 mL of EtOAc, 6.2 mmol of limonene, and desired amount of H2O2. The oil bath temperature was set at 95 °C during the reaction for the reflux and Dean–Stark experiments to allow volatization of water. The filtered samples were also analyzed with a GC-MS system and an autotitrator to quantify products or the remaining H2O2, respectively.

Product Analysis

Analysis of the products were performed with an Agilent 7890A GC system in which a flame ionization detector (FID) and an Agilent 5795C mass spectrometer were used for product quantification and identification. A DB-WAX column (30m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) from Agilent was applied for the gas chromatography analysis. For analysis, the column temperature was increased from 50 to 230 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min. The reported conversions are mole percent of the initial limonene, selectivities are the percent of limonene oxide moles produced per mole of limonene converted and the resulting yields are also expressed on mole percent

The concentration of the remaining H2O2 was calculated by using iodometric titration. The analysis was performed with a redox titration using a Metrohm 798 MPT Titrino autotitrator and a Pt electrode. The samples were mixed with a solution that included 50 mL of H2O, KI, and acetic acid. The prepared samples were further titrated using a 0.01N Na2S2O3 solution.

Catalyst Characterization

Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) experiments were conducted with a Netzsch STA449 F1 instrument connected to a mass spectrometer to determine the effluent species. The airflow was controlled at 60 mL/min, and the temperature ramp rate was 10 °C/min.

NH3-temperature programmed desorption (TPD) was conducted with a Micromeritics Autochem II 2920 instrument. The samples were dried at 125 °C for 2 h in an argon flow. Then, the temperature was cooled to 50 °C for the characterization. First, 10% NH3/He was flown across the sample for 1 h and then a He flow was used for 30 min to evacuate the nonadsorbed NH3.

Result and Discussion

Catalytic System Screening

γ-Al2O3 has been reported as active for the epoxidation of limonene,31 so it was used as the catalyst in the reaction system. The first set of experiments used this catalyst in a range of solvents. An equal molar amounts of H2O2 and limonene were reacted for 4 h in the screening tests. The solvents screened included methanol, ethanol, acetone, acetonitrile, ethyl acetate, and tetrahydrofuran (results in Figure S1). Despite its intermediate polarity among the solvent set, the reaction in EtOAc had the highest conversion after 4 h and achieved a near 40 mol % yield of limonene oxide. Compared with the reaction in EtOAc, the conversion rates and selectivity for all other solvents were lower. These results were consistent with earlier work,39 but lower overall conversions were targeted for the reaction runs to allow for intrinsic reactivity comparison without potential transport effects. The primary byproducts were carveol and limonene diol, but some oxidized byproducts generated from the respective solvents were also observed. With these results, EtOAc was selected as the solvent for the remainder of the reaction studies.

Initial Water Loadings and Related Effects

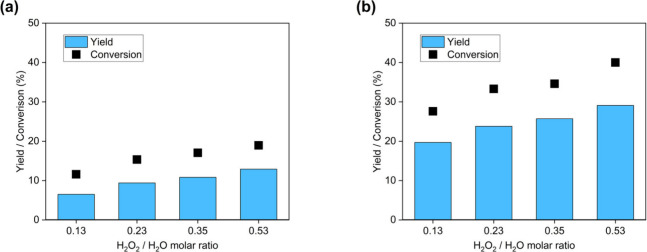

After the solvents were screened, determining how the remaining water in the system affected the reaction was studied by changing the initial water loading. The H2O2/limonene ratio was fixed at one so the runs with extra water were manifest as lower H2O2/H2O molar ratios. As H2O is generated during the reaction, the reported H2O2/H2O molar ratios represent those at the start of the run. In Figure 1a, 19.0% of limonene was converted with a 0.53 H2O2/H2O molar ratio after 1 h; in contrast, it only reached 11.6% conversion with a 0.13 H2O2/H2O molar ratio. A similar trend was observed for 4 h runs, as shown in Figure 1b. Here, 40.0% conversion was achieved using a 0.53 H2O2/H2O molar ratio whereas only 27.6% of the limonene was converted for the 0.13 H2O2/H2O molar ratio. Therefore, excess water addition had an ongoing impact on lowering oxidation activity with no asymptotic inhibition behavior for the range of water and reaction time tested. To examine the impact of water addition on selectivity, another experimental set was performed (results in Table 1) in which the reaction time was controlled to achieve about 10% conversion at each water level. As expected from the activity response, longer reaction times were required for the runs with higher water content, but the selectivity for all these runs was about 70% with the primary byproducts being carveol and other isomers. Therefore, the water content in the reaction did not significantly change the intrinsic selectivity and only impacted the reactivity for limonene epoxidation.

Figure 1.

Limonene conversion and limonene oxide conversions and molar yields under various water loading at 80 °C, 25 mg Al2O3, 0.62 mmol limonene and H2O2 for (a) 1 h; (b) 4 h.

Table 1. Limonene Epoxidation with Equal Molar Amounts of H2O2 at 10% Conversion.

| H2O2/H2O (Molar ratio) | Reaction time (min) | Conversion (%) | Selectivity (mol %) | Yield(mol %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.13 | 50 | 9.8 | 74 | 7.3 |

| 0.23 | 27 | 9.9 | 71 | 7.0 |

| 0.35 | 20 | 11.1 | 63 | 6.9 |

| 0.53 | 15 | 10.1 | 70 | 7.1 |

This first set of experiments can be used to examine several of the postulated effects of how water impacts the reaction. The impact of water concentration on the reaction rate was clearly seen (Figure 1 and Table 1) and yet in these experiments neither diol formation or catalyst aggregation were observed. Relative to many of the previous studies, the limonene conversion was held at low levels, and no limonene diol formation was observed. Additionally, across the range of initial H2O2/H2O molar ratios employed, there was no catalyst aggregation occurring. These results suggest that postulates (iv) and (v) are not the defining impacts of water on the reaction.

Catalytic Performance for Pretreated Catalysts

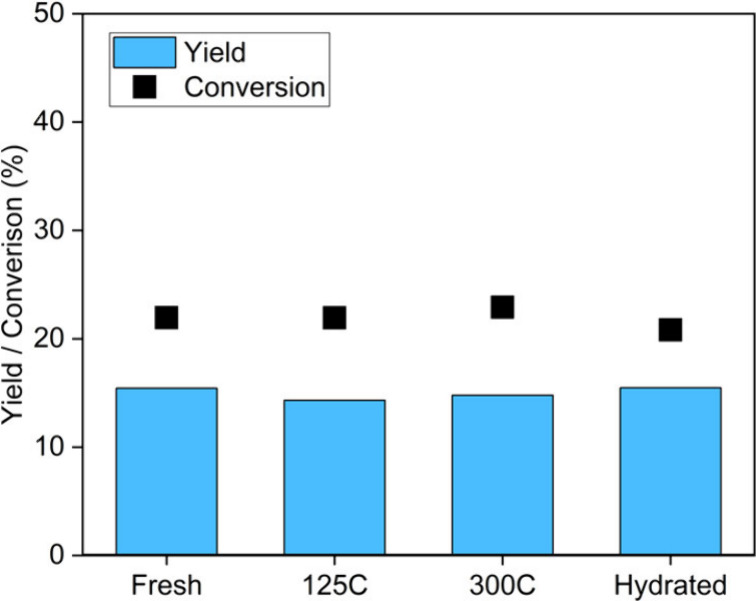

For the next set of experiments, the catalysts were characterized and tested using different pretreatment procedures to examine whether drying or hydroxylation pretreatment on γ-Al2O3 affected the epoxidation performance. The γ-Al2O3 catalysts were pretreated in four different ways: (a) as received without any treatment, (b) heated to 125 °C for 1 h, (c) heated to 300 °C for 1 h, and (d) hydrated by immersion in water at room temperature followed by air-drying. For the fresh γ-Al2O3, the TGA results (Figure S2) indicated that only one weight-loss at about 100 °C was observed, which would be related to physically bonded water. In contrast, TGA weight losses near 100 and 250 °C were observed with the hydrated γ-Al2O3, suggesting that the hydration pretreatment formed chemically bonded water in the form of hydroxyls. Previous work showed that some hydroxyl groups could be removed between 200 to 300 °C, leading to the formation of strong Lewis acid sites.33 In another study, TGA was proposed to be useful in differentiating physically and chemically bonded water on the γ-Al2O3 surface.40 Given these results, the 125 °C drying process was used to explicitly remove the physisorption water, whereas the treatments at 300 °C would be expected to also remove hydroxyl groups.

The reaction performances of fresh, dried, and hydrated γ-Al2O3 are compared in Figure 2. After 1 h of reaction, the observed conversions were from 20.8 to 22.9% and the yields were from 14.3 to 15.5 mol %. These differences were negligible relative to the impact of the different water loadings, as shown in Figure 1, which indicated that the various pretreatments of γ-Al2O3 had no significant impact on the reactivity for limonene epoxidation over the first hour of reaction. Therefore, the surface chemistry of the γ-Al2O3 materials reached equilibrium sufficiently rapidly at the reaction conditions to not manifest itself in the reaction results, which demonstrated that the initial H2O2 to water ratio was more important than the initial catalyst surface chemistry.

Figure 2.

Pretreated catalysts performance in limonene epoxidation for 1 h with 25 mg Al2O3, 0.62 mmol limonene and H2O2 at 80 °C.

NH3-TPD analysist was performed to determine the number of acid sites on the fresh γ-Al2O3 (see Figure S3). Using the integrated NH3 desorption peak area, it was found that 0.024 g of H2O/g of γ-Al2O3 would be required to saturate the acid sites. Therefore, the nearly 0.8 g of H2O/g of γ-Al2O3 added as part of the H2O2 solution was significantly more than the number of available acid sites. Additionally, the amount of water would continuously increase as H2O2 reacted. This calculation showed that the amount of water present in the reaction system was significantly more than enough to cover all the acid sites, which suggested that the number of hydroxyl groups on the catalyst surface in the initial state likely is not a dominant factor during the reaction. These results combined with those from the water loading experiments indicate that postulate (i) is not a determining factor for the impact of water on the reaction.

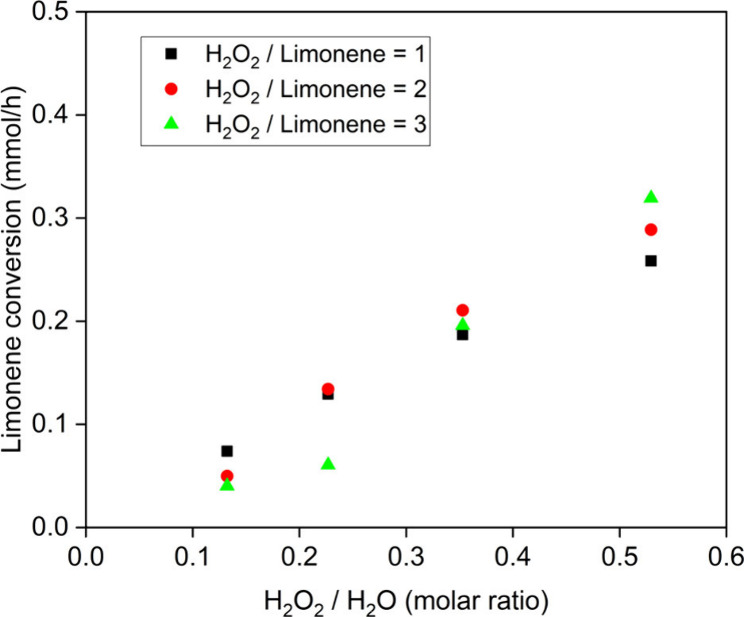

H2O2/H2O Ratio

With an increasing amount of water in the system, competitive absorption between H2O2 and water could reduce the number of activated peroxide groups on the surface (Al–O–OH).38 Alternatively, another proposed mechanism is that water can block the active sites and suppress Al–O–OH from forming.41,42 The latter mechanism requires actual adsorption of the water on the active site, which leads to a stronger interaction between H2O and the catalyst than merely blocking access to the site. While it is difficult to discriminate these two effects in this reaction system, they would lead to the same effect of reducing the number of active Al–O–OH sites on the surface. If this were the case, the intrinsic oxidation selectivity would remain the same, but a lower overall reactivity would result, as in fact shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. To further evaluate this possibility, the relationship between the H2O2/H2O ratio and the conversion rate is displayed in Figure 3. The conversion rates were determined when 10% of the limonene was converted. Comparing the results of equal molar ratio H2O2 and limonene, which are the black squares in Figure 3, the relationship between reactivity and the H2O2/H2O ratio was positively correlated. A higher H2O2/H2O ratio could favor Al–O–OH formation, which would lead to a higher reactivity with the same H2O2 level as it could be described as competitive adsorption of water and H2O2.

Figure 3.

Correlation between conversion at 1 h and the initial H2O2/H2O ratio (80 °C, 25 mg of Al2O3, 0.62 mmol of limonene).

When more H2O2 was added relative to limonene (red circles and green triangles), the reaction rate did not change appreciably for any H2O2/H2O ratio. These results suggested that the competitive adsorption of water and H2O2 controlled the reactivity, which might be related to the amount of Al–O–OH present.

The hydrophilicity created by hydroxyls on the surface might cause an enrichment of water near the active site, which could inhibit limonene adsorption.35 Such an inhibitory effect would lower the apparent epoxidation rate, as well. While not definitive, the enrichment of water at the surface would not be expected to result in a linear relationship between water content and conversion as shown in Figure 3. Overall, the results in Figure 3 may have more than a single contribution, but it is apparent that the reactivity did not proportionally increase with the introduction of more H2O2 into the solution independent of the amount of H2O. Therefore, the H2O2/H2O ratio is an important factor in the limonene oxidation reaction.

Catalytic Performance with Reduced Water Concentrations

As noted in the previous experiments, the effect of excess water addition could be readily examined. However, examining reaction performance below the water content present in the starting H2O2 solution is more difficult. Using higher concentrations of H2O2 is problematic from a handling safety standpoint. Therefore, a different strategy was used to examine higher concentrations of the oxidant.

A Dean–Stark apparatus can be used as an experimental apparatus to remove specific water from a reaction system. Its condenser setup can trap water while predominantly allowing only the organic solvent to reflux back into the reaction section. The reaction temperature was set at 95 °C to achieve a selective water removal. A comparison of limonene epoxidation conversion between a Dean–Stark apparatus and a regular reflux system with the same starting materials and temperature are shown in Figure 4. The higher limonene reaction rate with the Dean–Stark system is clearly shown as the difference in conversion increased linearly between the two reaction systems, presumably due to water partitioning created through the use of the Dean–Stark apparatus.

Figure 4.

Limonene conversion with applying Dean–Stark and regular reflux (95 °C, 25 mg Al2O3, 0.62 mmol limonene and H2O2).

The progression of the H2O2 concentration is shown in Figure 5 for the Dean–Stark and regular reflux systems in the presence of the limonene reaction as well as for a blank case in which no limonene was present. The hydrogen peroxide concentration was measured using the iodometry method. As would be expected from the limonene conversion results given in Figure 4, the hydrogen peroxide concentration decreased more rapidly in the Dean–Stark experiment. However, higher H2O2 loss was observed in the Dean–Stark system, even in the absence of the concomitant limonene oxidation reaction. The results demonstrated the cocurrent nonproductive H2O2 decomposition reaction with the desired oxidation reaction.

Figure 5.

H2O2 concentration during the reactions with Dean–Stark and regular reflux (95 °C, 25 mg Al2O3, 0.62 mmol limonene and H2O2).

Previous research suggested that some amount of water could be beneficial in decreasing the amount of H2O2 decomposition.30,31 It was also shown that competitive absorption between H2O and H2O2 reduced the amount of Al–O–OH on the γ-Al2O3 surface when more H2O was present.40 The lower decomposition rate would likely be related to the lower concentration of Al–O–OH species on the alumina surface. When considering the H2O2/H2O interaction in the context of the limonene oxidation reaction, reduction of the Al–O–OH species would also decrease the oxidation reaction rate, as this species reacts with the limonene. Therefore, competing effects influence the reduction of H2O2 in the reaction medium as shown in Figure 5. Despite the higher rate of limonene oxidation in the Dean–Stark system (Figure 4), the H2O2 concentration decreased more slowly in the regular reflux reaction system. Additionally, the decrease in H2O2 concentration in the Dean–Stark system appeared to be similar to or without the presence of the limonene oxidation reaction. It is known that acidity on the γ-Al2O3 surface can cause H2O2 decomposition and acetic acid formation was observed when both γ-Al2O3 and H2O2 were present, as shown in Figure S4. To ensure that H2O2 did not accumulate in the Dean–Stark trap, its concentration was measured in the trapped liquid phase. The results showed that only parts per million levels of the H2O2 were detected. Therefore, the loss of H2O2 in the Dean–Stark systems was due to either the epoxidation or decomposition reactions rather than accumulation in the trap. Taken together, it was apparent that the loss of the H2O2 was dominated by its decomposition rather than its reaction with limonene. These results were consistent with the results shown previously, in which adding more H2O2 did not significantly increase the limonene oxidation reaction rate.

To further examine the impact of the H2O2 concentration on the limonene oxidation reaction rate, the remaining H2O2 in the Dean–Stark and regular reflux reaction sections were compared with the limonene conversion versus reaction time. The results are shown in Figure 6. It is notable that the rate of limonene conversion was higher in the Dean–Stark system despite its lower H2O2 concentration.

Figure 6.

Remaining H2O2 and limonene conversion for reaction with (a) Dean–Stark and (b) regular reflux (95 °C, 25 mg of Al2O3, 0.62 mmol of limonene and H2O2).

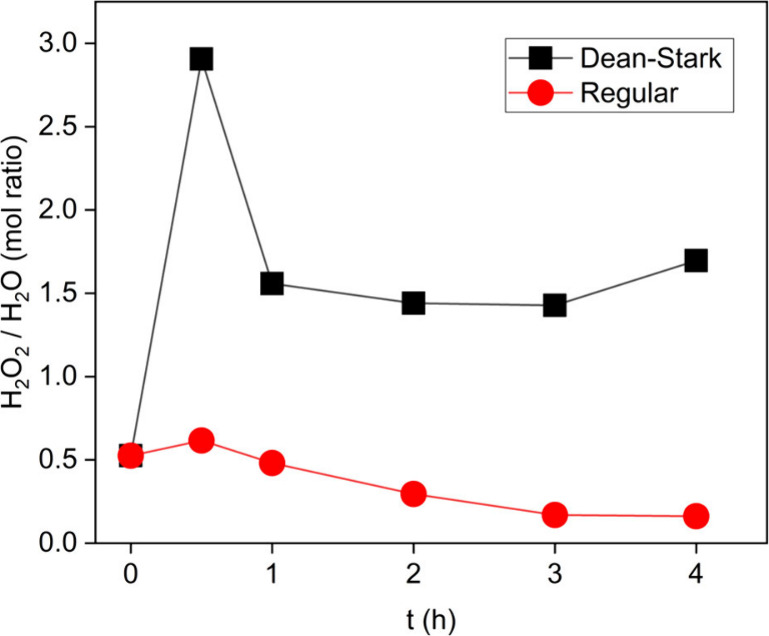

As shown in Figure 1, additional water incorporation led to a reduced oxidation reactivity. Additionally, the H2O2/H2O ratio was found to have a stronger impact on the initial limonene oxidation rate than the H2O2/limonene ratio (Figure 3). While it is clear that the H2O2/H2O ratio became lower when extra water was added into the regular reaction system, the change in this ratio in the Dean–Stark system was more complicated, since a higher H2O2 conversion rate and water removal both occurred. Therefore, the H2O2/H2O ratio in the two systems were compared relative to the reaction time as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

H2O2/H2O ratio comparison in Dean–Stark and regular reflux (95 °C, 25 mg Al2O3, 0.62 mmol limonene and H2O2).

In the Dean–Stark system, the H2O2/H2O ratio increased dramatically at first due to the water removal but then promptly decreased to a value of about 1.5. Therefore, even though the H2O2 decomposition increased, the ratio remained fairly steady due to water removal. In contrast, the H2O2/H2O ratio in the run with regular reflux slightly decreased over the course of the reaction. The results in Figure 7 show that with the Dean–Stark system, the water removal effect was much more significant than the faster H2O2 decomposition rate, which led to a higher H2O2/H2O ratio than with the regular reflux system at all times. The results in Figure 4 and Figure 7 were also consistent with the results in the vial tests, in which a higher H2O2/H2O ratio led to a higher limonene oxidation rate. Overall, the results of these experiments showed that the limonene oxidation rate could not be improved simply by adding more H2O2 solution into the system. Since the influence of water is significant, water removal should be considered a requirement to enhance the reaction performance.

Shown in Figure 8 is the impact of increasing the initial H2O2/limonene molar ratio on the conversion observed after 1 h. In the runs with regular reflux, the conversion after 1 h increased by only a small amount when the ratio was increased from 1 to 2 and effectively did not increase at the higher ratios. These results were consistent with those given in Figure 3 for the reactions performed in vials. In contrast, the runs with the Dean–Stark system showed successively higher conversions as the relative amount of H2O2 was increased until the H2O2/limonene molar ratio was increased to 4. This drop in conversion might have been due to the water being removed too slowly from the reaction zone.

Figure 8.

Limonene conversion in the Dean–Stark and regular reflux systems under various initial hydrogen peroxide loading (1 h, 95 °C, 25 mg Al2O3, 0.62 mmol limonene).

The results in Figure 8 are only at the early stage of the reaction. For the regular reflux system, the water concentration increased for higher reaction times leading to subsequent conversion of limonene epoxide to limonene diol. As this study focused on the water effects in limonene epoxidation, reaction times were limited to when only trace quantities of limonene diol were observed.

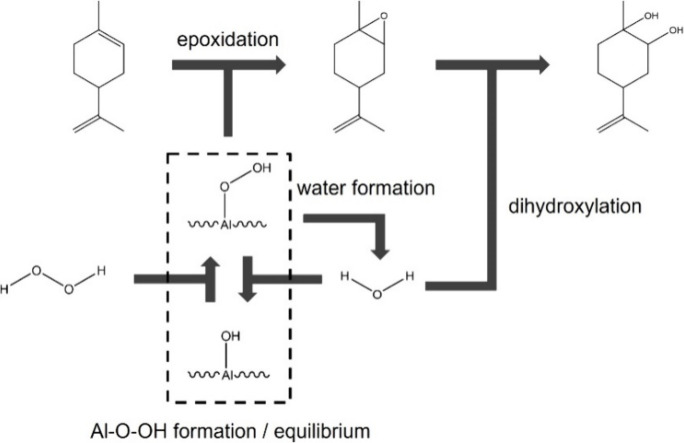

From this set of experiments, a detailed reaction network can be postulated that is consistent with the results. Shown in Scheme 2 is a reaction network representing how H2O, H2O2, and limonene interact during the reaction, with the equilibrated surface concentration of Al–OH and Al–O–OH dictating the rate of reaction, which is in agreement with postulate vi). As shown in the scheme, minimizing the water in the system, which allows for formation of higher concentrations of Al–O–OH, increases the rate of limonene oxidation, and decreases the rate of further reaction to the diol product. Importantly, the results do not support inhibited transport of the limonene in the reaction so postulates (ii) or (iii) are not describing the impact of water on the reaction. Byproducts such as carveol were not captured in this work, but the reaction network extension to these byproducts could be examined in further studies in particular with regards to the impact of H2O and H2O2 concentrations on byproducts at higher limonene conversions.

Scheme 2. Interactions among Water and Critical Components in Limonene Epoxidation.

Conclusions

Limonene oxidation is an important reaction to provide access to subsequent derivatives. An effective system for this reaction with H2O2 in EtOAc over γ-Al2O3 was evaluated. Water is both an unavoidable cofeed with H2O2 and a byproduct during oxidation. Previous studies have postulated a number of possible water-mediated phenomena in this reaction system. The current work carefully controlled reaction parameters to more systematically examine how water influences limonene oxidation.

When maintaining a specific initial H2O2 concentration, lower overall reactivity was observed when more water was introduced. This loss of reactivity did not have any significant concomitant impact on the selectivity to limonene oxide. However, for a specific initial H2O2/H2O ratio changing the relative initial limonene concentration did not change the reactivity. These results suggested that the competitive adsorption of H2O2 and H2O dictated the reaction rate with a higher H2O2/H2O ratio leading to more reactive Al–O–OH species on the surface. The dynamics of the surface species was examined through examining the conversion and yield resulting from using fresh, dried, and hydrated γ-Al2O3. The reactivity of these different starting aluminas was very similar suggesting that the surface species rapidly equilibrated to the reaction conditions.

The deleterious effect of H2O was further demonstrated when the reaction performance was compared in a Dean–Stark apparatus rather than with regular reflux. The increase in the limonene epoxidation rate with the Dean–Stark systems occurred despite the fact that a higher H2O2 decomposition rate was observed in the system. This result was due to the fact that despite the H2O2 decomposition rate a higher H2O2/H2O ratio was maintained over the course of the reaction than with the regular reflux system.

In this work, it was demonstrated that the key impact of H2O on the limonene oxidation reaction is the competitive adsorption of H2O2 and H2O rather than other previously postulated phenomena. As such, catalyst structural or surface chemistry modifications will not lead to improved performance. Therefore, diminishing the H2O concentration in the reaction system is required, for example, through a less dilute H2O2 feed concentration (a safety concern) or an alternative oxidant molecule.

Acknowledgments

This work at Iowa State University was supported by the Joint BioEnergy Institute (http://www.jbei.org), which in turn, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, through Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231 between Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the U.S. Department of Energy. We would like to thank Dr. Ting-Han Lee and Dr. Preana Carter for their help in the TGA-analysis.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available online and includes . The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/cbe.4c00151.

Results for different solvents, additional catalyst characterization and acetic acid formation results (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ciriminna R.; Lomeli-Rodriguez M.; Demma Carà P.; Lopez-Sanchez J. A.; Pagliaro M. Limonene: A Versatile Chemical of the Bioeconomy. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50 (97), 15288–15296. 10.1039/C4CC06147K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y.; Liu S.; Jin G.; Yang X.; Zhou Y. J. Microbial Production of Limonene and Its Derivatives: Achievements and Perspectives. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 44, 107628 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhl D.; Roberge D. M.; Hölderich W. F. Production of p-Cymene from α-Limonene over Silica Supported Pd Catalysts. Appl. Catal. Gen. 1999, 188 (1), 287–299. 10.1016/S0926-860X(99)00219-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bogel-Łukasik E.; Fonseca I.; Bogel-Łukasik R.; Tarasenko Y. A.; Ponte M. N. D.; Paiva A.; Brunner G. Phase Equilibrium-Driven Selective Hydrogenation of Limonene in High-Pressure Carbon Dioxide. Green Chem. 2007, 9 (5), 427–430. 10.1039/B617187G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna M.; Berti C.; Fiorini M.; Binassi E.; Mazzacurati M.; Vannini M.; Karanam S. Synthesis and Radiocarbon Evidence of Terephthalate Polyesters Completely Prepared from Renewable Resources. Green Chem. 2011, 13 (9), 2543. 10.1039/c1gc15400a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jongedijk E.; Cankar K.; Buchhaupt M.; Schrader J.; Bouwmeester H.; Beekwilder J. Biotechnological Production of Limonene in Microorganisms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100 (7), 2927–2938. 10.1007/s00253-016-7337-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicas J. L.; Dionísio A. P.; Pastore G. M. Bio-Oxidation of Terpenes: An Approach for the Flavor Industry. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109 (9), 4518–4531. 10.1021/cr800190y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlbusch K.-G.; Hammerschmidt F.-J.; Panten J.; Pickenhagen W.; Schatkowski D.; Bauer K.; Garbe D.; Surburg H.. Flavors and Fragrances. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2003. 10.1002/14356007.a11_141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennike N. H.; Oturai N. B.; Müller S.; Kirkeby C. S.; Jørgensen C.; Christensen A. B.; Zachariae C.; Johansen J. D. Fragrance Contact Allergens in 5588 Cosmetic Products Identified through a Novel Smartphone Application. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32 (1), 79–85. 10.1111/jdv.14513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark M. J.; Burke Y. D.; McKinzie J. H.; Ayoubi A. S.; Crowell P. L. Chemotherapy of Pancreatic Cancer with the Monoterpene Perillyl Alcohol. Cancer Lett. 1995, 96 (1), 15–21. 10.1016/0304-3835(95)03912-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutz L.; Kazemi F.; Mackenzie E.; Bergeron J.-Y.; Gagnon E.; Claverie J. P. Trans-Limonene Dioxide, a Promising Bio-Based Epoxy Monomer. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 59 (4), 321–328. 10.1002/pol.20200822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J. R.; Tolman W. B.; Hillmyer M. A. Oxidized Dihydrocarvone as a Renewable Multifunctional Monomer for the Synthesis of Shape Memory Polyesters. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10 (7), 2003–2008. 10.1021/bm900471a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrino F.; Fidalgo A.; Palmisano L.; Ilharco L. M.; Pagliaro M.; Ciriminna R. Polymers of Limonene Oxide and Carbon Dioxide: Polycarbonates of the Solar Economy. ACS Omega 2018, 3 (5), 4884–4890. 10.1021/acsomega.8b00644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindermann N.; Cristòfol À.; Kleij A. W. Access to Biorenewable Polycarbonates with Unusual Glass-Transition Temperature (Tg) Modulation. ACS Catal. 2017, 7 (6), 3860–3863. 10.1021/acscatal.7b00770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hauenstein O.; Agarwal S.; Greiner A. Bio-Based Polycarbonate as Synthetic Toolbox. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7 (1), 11862 10.1038/ncomms11862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauenstein O.; Reiter M.; Agarwal S.; Rieger B.; Greiner A. Bio-Based Polycarbonate from Limonene Oxide and CO 2 with High Molecular Weight, Excellent Thermal Resistance, Hardness and Transparency. Green Chem. 2016, 18 (3), 760–770. 10.1039/C5GC01694K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carrodeguas L. P.; Chen T. T. D.; Gregory G. L.; Sulley G. S.; Williams C. K. High Elasticity, Chemically Recyclable, Thermoplastics from Bio-Based Monomers: Carbon Dioxide, Limonene Oxide and ε-Decalactone. Green Chem. 2020, 22 (23), 8298–8307. 10.1039/D0GC02295K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira P.; Rojas-Cervantes M. L.; Ramos A. M.; Fonseca I. M.; do Rego A. M. B.; Vital J. Limonene Oxidation over V2O5/TiO2 Catalysts. Catal. Today 2006, 118 (3), 307–314. 10.1016/j.cattod.2006.07.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cagnoli M. V.; Casuscelli S. G.; Alvarez A. M.; Bengoa J. F.; Gallegos N. G.; Samaniego N. M.; Crivello M. E.; Ghione G. E.; Pérez C. F.; Herrero E. R.; Marchetti S. G. Clean” Limonene Epoxidation Using Ti-MCM-41 Catalyst. Appl. Catal. Gen. 2005, 287 (2), 227–235. 10.1016/j.apcata.2005.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanchikova I. D.; Maksimchuk N. V.; Skobelev I. Y.; Kaichev V. V.; Kholdeeva O. A. Mesoporous Niobium-Silicates Prepared by Evaporation-Induced Self-Assembly as Catalysts for Selective Oxidations with Aqueous H2O2. J. Catal. 2015, 332, 138–148. 10.1016/j.jcat.2015.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bisio C.; Gallo A.; Psaro R.; Tiozzo C.; Guidotti M.; Carniato F. Tungstenocene-Grafted Silica Catalysts for the Selective Epoxidation of Alkenes. Appl. Catal. Gen. 2019, 581, 133–142. 10.1016/j.apcata.2019.05.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewska A.; Makuch E.; Miądlicki P. The Studies on the Limonene Oxidation over the Microporous TS-1 Catalyst. Catal. Today 2016, 268, 121–129. 10.1016/j.cattod.2015.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham W. B.; Tibbetts J. D.; Hutchby M.; Maltby K. A.; Davidson M. G.; Hintermair U.; Plucinski P.; Bull S. D. Sustainable Catalytic Protocols for the Solvent Free Epoxidation and Anti -Dihydroxylation of the Alkene Bonds of Biorenewable Terpene Feedstocks Using H 2 O 2 as Oxidant. Green Chem. 2020, 22 (2), 513–524. 10.1039/C9GC03208H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ardagh M. A.; Bregante D. T.; Flaherty D. W.; Notestein J. M. Controlled Deposition of Silica on Titania-Silica to Alter the Active Site Surroundings on Epoxidation Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2020, 10 (21), 13008–13018. 10.1021/acscatal.0c02937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madadi S.; Charbonneau L.; Bergeron J.-Y.; Kaliaguine S. Aerobic Epoxidation of Limonene Using Cobalt Substituted Mesoporous SBA-16 Part 1: Optimization via Response Surface Methodology (RSM). Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 260, 118049 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madadi S.; Bergeron J.-Y.; Kaliaguine S. Kinetic Investigation of Aerobic Epoxidation of Limonene over Cobalt Substituted Mesoporous SBA-16. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11 (2), 594–611. 10.1039/D0CY01700K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonneau L.; Foster X.; Kaliaguine S. Ultrasonic and Catalyst-Free Epoxidation of Limonene and Other Terpenes Using Dimethyl Dioxirane in Semibatch Conditions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6 (9), 12224–12231. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b02578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonon A. J.; Kozlov Y. N.; Bahú J. O.; Filho R. M.; Mandelli D.; Shul’pin G. B. Limonene Epoxidation with H2O2 Promoted by Al2O3: Kinetic Study, Experimental Design. J. Catal. 2014, 319, 71–86. 10.1016/j.jcat.2014.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonon A. J.; Bahú J. O.; Klein B. C.; Mandelli D.; Filho R. M. Green Production of Limonene Diepoxide for Potential Biomedical Applications. Catal. Today 2022, 388–389, 288–300. 10.1016/j.cattod.2020.06.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary V. R.; Patil N. S.; Bhargava S. K. Epoxidation of Styrene by Anhydrous H2O2 over TS-1 and γ-Al2O3 Catalysts: Effect of Reaction Water, Poisoning of Acid Sites and Presence of Base in the Reaction Mixture. Catal. Lett. 2003, 89 (1), 55–62. 10.1023/A:1024715325270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet M. C. A.; Mandelli D.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Schuchardt U.; Sheldon R. A. Alumina: A Cheap, Active and Selective Catalyst for Epoxidations with (Aqueous) Hydrogen Peroxide. Green Chem. 2001, 3 (5), 243–246. 10.1039/b103952k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonneau L.; Kaliaguine S. Epoxidation of Limonene over Low Coordination Ti in Ti- SBA-16. Appl. Catal. Gen. 2017, 533, 1–8. 10.1016/j.apcata.2017.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. DRIFTS Study of Surface of γ-Alumina and Its Dehydroxylation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112 (13), 5066–5073. 10.1021/jp711901s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi R.; Fujiwara F. Y.; Schuchardt U. Chemical and Physical Changes Related to the Deactivation of Alumina Used in Catalytic Epoxidation with Hydrogen Peroxide. J. Catal. 2007, 245 (2), 456–465. 10.1016/j.jcat.2006.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bregante D. T.; Flaherty D. W. Impact of Specific Interactions Among Reactive Surface Intermediates and Confined Water on Epoxidation Catalysis and Adsorption in Lewis Acid Zeolites. ACS Catal. 2019, 9 (12), 10951–10962. 10.1021/acscatal.9b03323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewska A. The Epoxidation of Limonene over the TS-1 and Ti-SBA-15 Catalysts. Molecules 2014, 19 (12), 19907–19922. 10.3390/molecules191219907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casuscelli S. G.; Crivello M. E.; Perez C. F.; Ghione G.; Herrero E. R.; Pizzio L. R.; Vázquez P. G.; Cáceres C. V.; Blanco M. N. Effect of Reaction Conditions on Limonene Epoxidation with H2O2 Catalyzed by Supported Keggin Heteropolycompounds. Appl. Catal. Gen. 2004, 274 (1), 115–122. 10.1016/j.apcata.2004.05.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon S.; Schweitzer N. M.; Park S.; Stair P. C.; Snurr R. Q. A Kinetic Study of Vapor-Phase Cyclohexene Epoxidation by H2O2 over Mesoporous TS-1. J. Catal. 2015, 326, 107–115. 10.1016/j.jcat.2015.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uguina M. A.; Delgado J. A.; Rodríguez A.; Carretero J.; Gómez-Díaz D. Alumina as Heterogeneous Catalyst for the Regioselective Epoxidation of Terpenic Diolefins with Hydrogen Peroxide. J. Mol. Catal. Chem. 2006, 256 (1), 208–215. 10.1016/j.molcata.2006.04.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi R.; Fujiwara F. Y.; Hölderich W.; Schuchardt U. Tuning the Acidic Properties of Aluminas via Sol-Gel Synthesis: New Findings on the Active Site of Alumina-Catalyzed Epoxidation with Hydrogen Peroxide. J. Catal. 2006, 244 (1), 92–101. 10.1016/j.jcat.2006.08.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary V. R.; Patil N. S.; Chaudhari N. K.; Bhargava S. K. Epoxidation of Styrene by Anhydrous Hydrogen Peroxide over Boehmite and Alumina Catalysts with Continuous Removal of the Reaction Water. J. Mol. Catal. Chem. 2005, 227 (1), 217–222. 10.1016/j.molcata.2004.10.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bu Y.; Wang Y.; Zhang Y.; Wang L.; Mi Z. Epoxidation of Cyclohexene on Modified Ti-Containing Mesoporous MCM-41. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 2007, 90 (1), 77–84. 10.1007/s11144-007-4834-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.