Abstract

Aims

Glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptor agonists and dual agonists have changed the treatment landscape of obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D), but significant limitations have emerged due to their gastrointestinal side effects, loss of lean mass, and necessity for ongoing subcutaneous injections. Our objective was, therefore, to test a novel small molecule as a different and potentially better tolerated oral medications to improve obesity‐associated impairment in glucose homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

High‐fat diet (HFD)‐fed mice or severely obese, leptin‐deficient ob/ob mice were randomly assigned to serve as controls or receive oral TIX100, a novel thioredoxin‐interacting protein (TXNIP) inhibitor just approved by the FDA as an investigational new drug for type 1 diabetes (T1D). The TIX100 effects on glucose intolerance and weight control were then assessed.

Results

TIX100 protected against HFD‐induced glucose intolerance, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperglucagonemia. TIX100 also reduced diet‐induced adiposity resulting in 15% lower weight in treated mice as compared with controls on HFD (p <0.05), while preserving lean mass. Even though the TIX100 weight effects were lost in ob/ob mice, TIX100 improved glucose control leading to a dramatic 2.3% reduction in HbA1C (p <0.05), independent of any weight loss. This is consistent with the beneficial effects of TIX100 in non‐obese diabetes models and its protection against elevated TXNIP and islet cell stress common to all diabetes types.

Conclusions

Thus, TIX100 may provide a novel, oral therapy for T2D that targets underlying disease pathology including islet cell dysfunction and hyperglucagonemia and promotes metabolic health and weight control without aggressive weight loss.

Keywords: glucose intolerance, lean mass, leptin, obesity, thioredoxin‐interacting protein, type 2 diabetes

1. INTRODUCTION

Glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP‐1) receptor agonists and dual agonists/ incretin mimetics such as semaglutide and tirzepatide seem to have revolutionized the treatment of obesity and T2D based on their dramatic effects on weight loss. 1 , 2 However, after the initial excitement, it has become apparent that while being powerful and beneficial for some patients, this approach may not be sustainable for others. This is primarily due to the associated gastrointestinal side effects including nausea, delayed gastric emptying, and gastrointestinal paralysis that in severe cases resulted in ileus, as well as concomitant loss of lean mass, and necessity to continue the subcutaneous injections indefinitely. 3 , 4 This underlines the remaining need for novel oral medications with different, milder effects to improve obesity‐associated impairment in glucose homeostasis long‐term, especially given the ever growing number of people affected by diabetes and prediabetes.

TIX100 (aka SRI‐37330) is an orally available, specifically developed, and optimized small molecule TXNIP inhibitor 5 that just was approved as an investigational new drug, and received clearance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to enter clinical trials. 6 To do so, TIX100 underwent extensive safety and toxicology studies including in rats and dogs and no specific side effects have become apparent. In addition, we have demonstrated that TIX100 effectively lowers TXNIP expression in rodent and human islets especially in the context of high glucose. 5 , 6 We and others have shown that TXNIP expression is induced at the transcriptional level by high glucose and by diabetes, and that elevated TXNIP, in turn, promotes islet beta cell apoptosis 7 and represents a critical link between glucose toxicity and beta cell loss. 8 On the other hand, whole body TXNIP deficiency or beta cell‐specific TXNIP deletion protected mice against different models of diabetes. 9 , 10 , 11 Together, these studies established inhibition of elevated TXNIP expression as a promising therapeutic approach to be targeted pharmacologically, and led to the development of TIX100. Mechanistically, TIX100 functions at the molecular level by inhibiting TXNIP transcription via a specific 20 bp region containing an E‐box motif in the TXNIP promoter as demonstrated by TXNIP promoter analyses, luciferase assays and chromatin immunoprecipitation studies. 5 As a small molecule salt formulation, TIX100 is water soluble and orally available, and we have previously reported the beneficial effects of TIX100 in diabetes induced by streptozotocin (STZ)‐mediated destruction of pancreatic beta cells. 5 However, its effects in the context of diet‐induced obesity and impaired glucose tolerance as a more relevant model of human pathophysiology and T2D have not been explored. The current studies were therefore aimed at defining the TIX100 effects on obesity‐associated glucose intolerance.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animal studies

All mouse studies were approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Animal Care and Use Committee. Wild‐type C57Bl/6J mice (RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664) and leptin‐deficient, obese and glucose‐intolerant B6.Cg‐Lep ob/J (ob/ob) (RRID:IMSR_JAX:000632) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were housed under 12 h light and 12 h dark cycles and were provided ad libitum access to regular chow (NIH‐31, formular no. 5L3Z, LabDiet, ST. Louis, MO) or a high‐fat, high‐sucrose diet (HFD: 58% fat + sucrose; #D12331 Research Diets New Brunswick, NJ) to induce glucose intolerance and obesity in wild‐type mice.

2.2. TIX100 treatment

The substituted quinazoline‐sulfonamide TXNIP inhibitor, TIX100, was a generous gift from TIXiMED, Inc. Mice on HFD or ob/ob mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups to be treated with oral TIX100 (100 mg/kg/day in the drinking water) (n = 12) or (n = 3) or without TIX100 (n = 20) or (n = 4), respectively, as described in detail previously. 5 Other treatments were as previously reported, metformin (250 mg/kg/day), 5 or empagliflozin (10 mg/kg/day) in the drinking water, 5 and leptin (7.2 mg/kg i.p.). 12

2.3. Glucose and insulin tolerance tests and HbA1C

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests (i.p.GTT) and insulin tolerance tests (ITT) were performed following a 4‐h fast using 2 g/kg glucose, i.p. and 0.55 U/kg insulin, i.p., at 8 and 9 weeks of treatment, respectively. 9 A Freestyle Lite glucometer was used to determine blood glucose levels. At the end of the 12‐week experiment HbA1C was measured using a DCA Vantage Analyzer (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY).

2.4. Plasma hormone measurements and assessment of metabolic parameters

Plasma insulin and glucagon levels were determined by the Ultra Sensitive Mouse Insulin ELISA Kit (Crystal Chem, Elk Grove Village, IL) and Mouse Glucagon ELISA Kit (Crystal Chem), respectively. Plasma GLP‐1 was measured with a GLP‐1 Multispecies ELISA Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and leptin with a Mouse Leptin ELISA Kit (Crystal Chem). Cholesterol was assessed with a Colorimetric Assay Kit (Cat# ab282928, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), triglycerides (with Kit Cat# ab65336, Abcam), non‐esterified fatty acids (NEFA) (with a kit from Wako, Richmond, VA), and plasma alanine transaminase (ALT) with an Activity Assay Kit (Cat# MAK052, Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO).

2.5. Immunohistochemistry and quantitative real‐time PCR (qPCR)

Pancreas sections were immunostained for insulin using ready‐to‐use mouse anti‐insulin antibody (IHC World, Cat# IW‐MA1052, RRID:AB_2915940), goat anti‐mouse biotinylated secondary (1:200, Vector Laboratories Inc., Cat# BA‐9200, RRID:AB_2336171), VECTASTAIN ABC‐AP kit (Cat# AK‐5000, Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA), and Vector Blue kit (Cat# SK‐5300, Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA) and counterstained with Nuclear Fast Red (Cat# N3020‐100ML, Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Images were acquired using an Olympus IX81 inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). TXNIP expression in pancreatic islets and liver was assessed using the primary mouse JY2 TXNIP monoclonal antibody (MBL International, RRID: AB_592934) and secondary Alexa Fluor 488‐AffiniPure anti‐mouse, Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, RRID: AB_2340846), nuclei were stained by DAPI. For these studies the experimenter was blinded to the study group or treatment of the mice.

For qPCR, total RNA was extracted using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and RNA reverse transcribed to cDNA using the first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Roche) and the mouse TXNIP primers: Forward, 5′‐CCTAGTGATTGGCAGCAGGT‐3′ and Reverse, 5′‐GAGAGTCGTCCACATCGTCC‐3′. All results were corrected using the 18S ribosomal subunit as the internal standard as described previously. 5

2.6. Beta cell apoptosis

INS‐1 beta cells were seeded into 6‐well plates (8 × 105 cells per well) in 2 mL RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 11.1 mmol/L glucose, 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, 2 mmol/L L‐glutamine, 10 mmol/L HEPES and 0.05 mmol/L 2‐mercaptoethanol for 24 h, followed by induction of apoptosis with incubation at high (25 mM) glucose and treatment with or without TIX100 (10 μM) for 48 h. Apoptosis was quantified using the Cell Death Detection ELISA PLUS Kit (Roche) (RRID: AB_2909412) following the manufacturer's instructions.

2.7. Body weight, food intake and gastric emptying

Body weight and food intake were monitored on a weekly basis. Gastric emptying was assessed as described previously. 13 In brief, after an overnight fast, mice were placed in clean, individual cages and provided with ad libitum HFD food for 3 h while continuing to have free access to drinking water and treatment. Food and water were then removed and 2 h later the mice were sacrificed and their stomachs underwent careful dissection (by the same experimenter). The amount of total food intake and the full and empty stomach weights were recorded for each animal to establish the remaining gastric content after 2 h of fasting. The rate of gastric emptying (% in 2 h) was calculated as [1 − (gastric content/ food intake)]* 100.

2.8. Quantitative magnetic resonance and indirect calorimetry

Body composition, including fat mass, lean mass and total body water was measured using noninvasive quantitative magnetic resonance (QMR) (EchoMRI, Echo Medical Systems) at the UAB Diabetes Animal Physiology Core. A combined indirect calorimetry system (Comprehensive Laboratory Animal Monitoring System; Columbus Instruments) was used as previously described 14 to simultaneously measure O2 consumption and CO2 production every 15 min to determine total and resting energy expenditure (TEE & REE) and the respiratory quotient (RER). Home‐cage locomotor activity was determined using a multidimensional infrared light‐beam system.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Student t tests were used to calculate the significance of a difference between two groups. Datasets containing multiple groups or changes over time were analysed using one‐way or repeated measures ANOVA, respectively. All tests were two‐tailed, p <0.05 was considered significant, SigmaStat 4.0 was used.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Oral TIX100 treatment protects against high‐fat diet‐induced glucose intolerance

HFD recapitulated many of the features of human T2D and led to marked impairment in glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, to elevated blood glucose and haemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) as well as to hyperinsulinemia and hyperglucagonemia as compared with regular chow diet (Figure 1). Interestingly, mice receiving oral TIX100 treatment were completely protected from glucose intolerance as demonstrated by the normalized i.p. GTT (Figure 1A,B) and insulin sensitivity (Figure 1C,D). TIX100 treatment further led to significantly improved blood glucose and HbA1C (Figure 1E,F) and to normalization of the hyperinsulinemia and hyperglucagonemia (Figure 1G,H). TIX100 treatment also completely reversed the islet beta cell hyperplasia observed in HFD‐fed mice (Figure 1I), and this likely helped normalize the elevated insulin levels observed in association with the HFD.

FIGURE 1.

Oral TIX100 treatment protects against high‐fat diet‐induced glucose intolerance. Wild‐type C57BL/6J 8‐week‐old male mice were maintained on regular chow (control) or received high fat diet (HFD) with or without TIX100 treatment (100 mg/kg/day in the drinking water) for 12 weeks, and their glucose homeostasis was assessed by intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests (i.p.GTT) and area under the curve (AUC) (A, B) and insulin tolerance tests (ITT) (C, D), as well as blood glucose (E), haemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) (F), and fasting plasma insulin (G) and glucagon (H) as measured by ELISA; (I) Representative immunohistochemistry images of pancreatic islets from mice fed with chow, HFD or HFD and oral TIX100 treatment; blue = insulin staining, scale bar = 20 μm; n = 4–20 mice per group, means ± s.e.m., *p <0.05 HFD + TIX100 versus HFD.

3.2. Oral TIX100 improves metabolic parameters

TIX100 also improved other metabolic parameters in the context of HFD, including plasma cholesterol, triglycerides and ALT (Figure 2A–C), while not elevating NEFA (Figure 2D). In addition, analysis of the TIX100 effects on TXNIP expression in different metabolic tissues confirmed the TXNIP downregulation in pancreatic islets, liver and adipose tissue (Figure S1).

FIGURE 2.

Oral TIX100 improves metabolic parameters. 8‐week‐old male C57BL/6J mice received high fat diet (HFD) with or without TIX100 treatment (100 mg/kg/day in the drinking water) for 12 weeks, and their plasma cholesterol (A), triglycerides (B), and alanine transaminase (ALT) (C) as well as non‐esterified fatty acids (NEFA) (D) were assessed; n = 4–6 mice per group, means ± s.e.m., *p <0.05; NS, not significant.

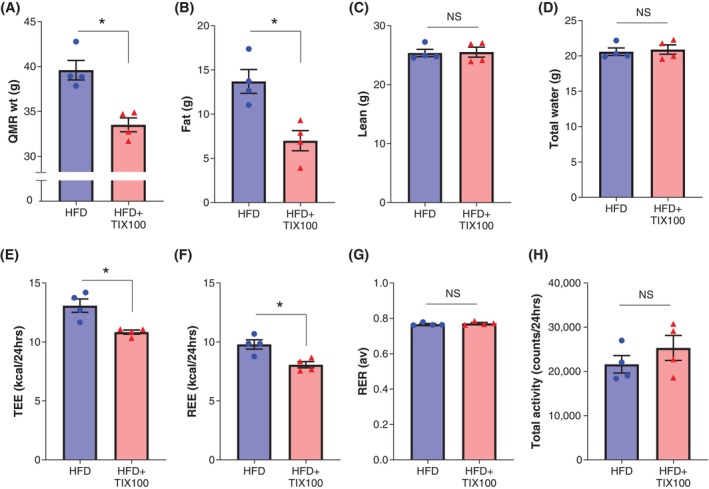

3.3. TIX100 treatment decreases fat mass without affecting lean mass

To determine any TIX100 effects on body composition and energy metabolism, we conducted quantitative magnetic resonance (QMR) and indirect calorimetry. QMR revealed lower body weights for TIX100‐treated HFD‐fed mice (Figure 3A) and a dramatic 50% reduction in their fat mass (Figure 3B), while their lean mass and total water remained unchanged (Figure 3C,D). Calorimetry showed decreased total and resting energy expenditure in TIX100‐treated mice consistent with the adaptation to their lower body weight as compared with control, untreated HFD‐fed mice (Figure 3E,F). On the other hand, respiratory exchange ratio (as an estimate of the respiratory quotient and fuel type utilized) and total activity were not affected by TIX100 treatment (Figure 3G,H).

FIGURE 3.

TIX100 treatment decreases fat mass without affecting lean mass. Body composition and energy expenditure of wild‐type mice on high fat diet (HFD) treated with or without TIX100 treatment (100 mg/kg/day in the drinking water) for 12 weeks were assessed by quantitative magnetic resonance (QMR) and indirect calorimetry. QMR body weight (A), fat mass (B), lean mass (C) and total water (D) as well as total energy expenditure (TEE) (E), resting energy expenditure (REE) (F), respiratory exchange ratio (RER) (G) and total activity (H), are shown; n = 4 mice per group, means ± s.e.m., *p <0.05; NS, not significant.

3.4. Oral TIX100 reduces high‐fat diet‐induced weight gain

Longitudinal weight assessment revealed that oral TIX100 treatment led to a rapid, sustained and significant 15% reduction in HFD‐induced weight gain (Figure 4A). It also resulted in a mild but persistent reduction in food intake (Figure 4B). We, therefore, next investigated the possibility that TIX100 may slow gastric emptying, which in turn could result in decreased food intake. However, gastric emptying was not affected by TIX100 (Figure 4C). Since leptin and GLP‐1 are key hormone inhibitors of food intake, we further tested whether TIX100 would lead to any increase in their levels but found that both were reduced, consistent with the lower glucose levels and lower fat mass in TIX100‐treated HFD‐fed mice (Figure 4D,E). On the other hand, we were able to demonstrate that the weight‐lowering effects of TIX100 were completely lost in the absence of TXNIP as shown in HFD‐fed TXNIP‐deficient mice (Figure S2A,B). Moreover, since the lower leptin levels observed raised the possibility of increased leptin sensitivity, we also tested whether TIX100 could enhance the leptin‐mediated inhibition of food intake. Indeed, we found that when added to leptin treatment, TIX100 led to a dramatic reduction in food intake as compared with leptin alone (Figure S3).

FIGURE 4.

Oral TIX100 reduces high‐fat diet‐induced weight gain. Body weight (A) and food intake (B) of wild‐type C57BL/6J male mice receiving high fat diet (HFD) or HFD with TIX100 treatment (100 mg/kg/day in the drinking water) during the experiment are shown. Mice were also assessed for gastric emptying (C) and plasma GLP‐1 (D) and leptin levels (E) were measured by ELISA in HFD‐fed mice with or without TIX100 treatment; n = 4–20 mice per group, means ± s.e.m., *p <0.05; NS, not significant.

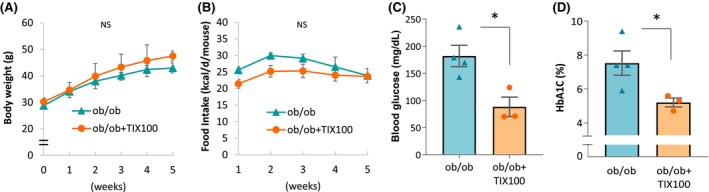

3.5. TIX100 improves glucose homeostasis but not weight in severe, leptin‐deficient obesity

In addition, we tested the effects of TIX100 treatment in the context of a severe model of genetic obesity using glucose‐intolerant, leptin‐deficient ob/ob mice. We found that while TIX100 was no longer able to inhibit weight gain or food intake (Figure 5A,B), it still had a clear effect on glucose homeostasis resulting in a dramatically lower blood glucose and HbA1C in TIX100‐treated ob/ob mice as compared with untreated littermates (Figure 5C,D). In fact, comparison of the TIX100 effects across a variety of different diabetes models revealed that it improved glucose homeostasis irrespective of whether the impairment in glucose control was due to diet, genetic mutations or chemical toxin, whether it was associated with obesity, or whether TIX100 was also able to reduce body weight (Table S1). In addition, hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp studies in obese diabetic mice revealed that TIX100 effectively suppressed hepatic glucose production consistent with its glucagon‐lowering effects. However, in the absence of weight loss, TIX100 did not lead to any increase in insulin sensitivity (Table S1). Together with the proven detrimental role of elevated TXNIP in pancreatic islets in regard to oxidative stress, glucose toxicity, beta cell apoptosis, and excessive alpha cell glucagon secretion, 7 , 8 , 9 , 15 this suggested that TIX100 may achieve its beneficial effects on glucose control at least in part by targeting the common features of islet cell stress and dysfunction shared by all of these models (Table S1). Indeed, including examination of beta cells in response to TIX100, we were now able to demonstrate that TIX100 effectively protected against glucose‐induced apoptosis (Figure S4).

FIGURE 5.

TIX100 improves glucose homeostasis but not weight in severe, leptin‐deficient obesity. Male, 8‐week‐old, leptin‐deficient ob/ob mice on regular chow were treated with or without oral TIX100 (100 mg/kg/day in the drinking water) for 5 weeks, and their (A) body weight and (B) food intake as well as (C) blood glucose and (D) HbA1C are shown. n = 3–4 mice per group; means ± s.e.m., *p <0.05; NS, not significant.

Interestingly, a comparison of the antidiabetic effects of TIX100 with those of commonly used oral diabetes medications further revealed that TIX100 was significantly more effective in lowering blood glucose than metformin or empagliflozin. In fact, only TIX100 led to a complete normalisation of glycemia with blood glucose levels that were indistinguishable from non‐diabetic baseline values (Figure S5).

4. DISCUSSION

In summary, our results demonstrate for the first time that TIX100, a novel orally available TXNIP inhibitor, protects against HFD diet‐induced glucose intolerance, hyperinsulinemia and hyperglucagonemia and reduces diet‐induced adiposity, while preserving lean mass. Such improvement in glucose homeostasis and decrease in glucagon levels is consistent with the protective effects that genetic TXNIP deficiency and beta cell TXNIP deletion have shown against different models of diabetes 9 and the observation that alpha cell TXNIP deletion leads to decreased glucagon secretion. 15 In addition, and in contrast to some glucagon receptor antagonists that have been reported to cause liver enzyme abnormalities and elevation in plasma cholesterol and glucagon, 16 TIX100 treatment improved plasma cholesterol, triglycerides, and ALT levels and normalized the hyperglucagonemia.

Surprisingly, TIX100 also blunted weight gain associated with HFD as a model of human obesity, whereas it had no effect on severe, genetic obesity models. While this may have contributed to the improvement in glucose homeostasis observed in HFD‐fed mice, the TIX100 effect on body weight was only mild and partial, yet completely normalized all other parameters of HFD‐induced impairment in glucose homeostasis including blood glucose, HbA1C, GTT, ITT and plasma insulin and glucagon. This suggests that these beneficial effects were not solely due to the lower body weight, which is strongly supported by our additional findings that TIX100 dramatically improved blood glucose and HbA1C in ob/ob mice without affecting their weight. This notion is also consistent with our previous demonstration that TIX100 has anti‐diabetic effects independent of any weight loss in genetically diabetic db/db as well as non‐obese STZ‐diabetic mice. 5 Our results now suggest that TIX100 maintains these beneficial effects on glucose control in the context of diet‐induced glucose intolerance as a more relevant model of human T2D. Moreover, based on the detrimental effects attributed to elevated TXNIP in islet biology 7 , 8 , 9 , 15 our findings further suggest that these anti‐diabetic effects are at least in part mediated by TIX100 targeting islet dysfunction including normalisation of glucagon secretion and insulin production. In addition, we have now found that TIX100 dramatically reduced glucose‐induced beta cell apoptosis. Also, since our previous hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp studies in lean mice and in db/db mice showed no increase in inulin sensitivity in response to TIX100, 5 these studies were not repeated in the current models. However, based on these findings, the improved ITT observed in the present studies in HFD‐fed mice treated with TIX100 is most likely due to the concomitant weight loss as, in the absence of weight loss, no such improvement was observed in any of the other models. On the other hand, the clamp studies demonstrated that TIX100 treatment decreases hepatic glucose production irrespective of the model 5 suggesting that the liver may play an important role in the beneficial metabolic effects observed with TIX100. In addition, based on the significant downregulation of TXNIP expression in adipose tissue in response to TIX100 and the previously reported improvement in glucose uptake in adipocytes with TXNIP knockdown, 17 adipose tissue may also be involved in the beneficial TIX100 effects.

Interestingly, we discovered that the weight‐controlling effects of TIX100 in the context of HFD‐induced obesity were completely lost in TXNIP‐deficient mice. This, despite the fact that some genetic TXNIP knockout models have been reported to have increased adiposity when fed HFD or standard chow. 11 However, a more recent CRISPR/Cas9‐induced TXNIP deletion mouse model was found to exhibit decreased weight gain in response to HFD, 18 in alignment with our TIX100 findings suggesting that the type of TXNIP inhibition may affect its effect on weight control.

Mechanistically, the reduced weight gain observed with HFD and TIX100 treatment can be explained by the concomitant reduction in food intake, especially as indirect calorimetry did not reveal any change in energy expenditure. Intriguingly, we further found that TIX100 dramatically enhanced leptin‐mediated inhibition of food intake. Taken together with the TIX100 associated decrease in circulating leptin levels and the loss of TIX100‐mediated weight control in models with disrupted leptin signalling such as ob/ob and db/db mice, this supports the idea of increased leptin sensitivity.

Furthermore, it is important to note that the TXI100‐mediated decrease in food intake was not associated with any increase in GLP‐1 or any decrease/slowing of gastric emptying. This is a major differentiating factor from GLP‐1 agonists that clearly inhibit gastric emptying and result in a pronounced reduction in food intake and body weight, but in many subjects also in nausea and gastrointestinal side effects. As such, TIX100 promises to offer a milder and hopefully better tolerated approach, while still providing weight control and normalisation of glucose homeostasis.

Pancreatic islet cell stress and dysfunction are key factors in the pathogenesis and progression of both, T1D and T2D. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 TXNIP, in turn, has been shown to be elevated in human and mouse islets with diabetes 8 , 23 and to promote loss of beta cell function, beta cell apoptosis 7 , 8 , 24 and excessive alpha cell glucagon secretion. 15 Of note, TXNIP deletion and non‐specific TXNIP inhibition with verapamil has proven effective in protecting against different models of diabetes. 9 , 25 Importantly, the translatability of these anti‐diabetic effects has now been demonstrated in adults with recent onset T1D by again using verapamil 26 , 27 and validated in children with T1D in the CLVer Trial. 28 Verapamil has also been shown to improve glucose homeostasis in T2D. 29 However, being a calcium channel blocker, it limits its use in some patients due to the risk of arrhythmias, especially atrioventricular heart blocks. This could particularly become problematic in the T2D population as classical characteristics such as higher age and elevated blood glucose have been shown to represent risk factors. 30 TIX100 is not a calcium channel blocker and, therefore, does not have this potential issue, and has just been cleared by the FDA to proceed to clinical trials as an investigational new drug for T1D. 5 , 6 Of note, in preclinical studies, TIX100 has also been found to be more potent and effective than verapamil 6 and more effective than several approved oral anti‐diabetic drugs including metformin and empagliflozin.

Taken together, TIX100 may represent a new oral medication not only for T1D, but also for T2D. Such a novel pharmacological approach would offer multiple attractive features including the targeting of several common underlying disease processes like beta cell apoptosis, islet cell stress and dysfunction and hyperglucagonemia, and should provide effective normalisation of glucose homeostasis, but without aggressive reduction in food intake and body weight, and without loss of lean mass.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.H.J. performed and analysed the experiments, G.J and J.C. helped with all the mouse studies, G.X. was responsible for the hormone assays, A.S. conceived the project, wrote the manuscript and is the guarantor of this work. As such, she had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by R01DK137506 granted to A.S. The UAB Diabetes Animal Physiology Core is directed by Dr. Kirk Habegger, supported by P30DK079626 and assisted with the metabolic experiments.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

A.S. also serves as the co‐founder and CSO of TIXiMED, Inc.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank TIXiMED, Inc. for their generous gift of TIX100.

Jo S, Jing G, Chen J, Xu G, Shalev A. Oral TIX100 protects against obesity‐associated glucose intolerance and diet‐induced adiposity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025;27(4):2223‐2231. doi: 10.1111/dom.16223

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nauck MA, D'Alessio DA. Tirzepatide, a dual GIP/GLP‐1 receptor co‐agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes with unmatched effectiveness regrading glycaemic control and body weight reduction. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21(1):169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Neil PM, Birkenfeld AL, McGowan B, et al. Efficacy and safety of semaglutide compared with liraglutide and placebo for weight loss in patients with obesity: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo and active controlled, dose‐ranging, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10148):637‐649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sodhi M, Rezaeianzadeh R, Kezouh A, Etminan M. Risk of gastrointestinal adverse events associated with glucagon‐like Peptide‐1 receptor agonists for weight loss. JAMA. 2023;330(18):1795‐1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aldhaleei WA, Abegaz TM, Bhagavathula AS. Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists associated gastrointestinal adverse events: a cross‐sectional analysis of the National Institutes of Health all of us cohort. Pharmaceuticals. 2024;17(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thielen LA, Chen J, Jing G, et al. Identification of an anti‐diabetic, orally available small molecule that regulates TXNIP expression and glucagon action. Cell Metab. 2020;32:353‐365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jing G, Jo S, Shalev A. A novel class of oral, non‐immunosuppressive, beta cell‐targeting, TXNIP‐inhibiting T1D drugs is emerging. Front Endocrinol. 2024;15:1476444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Minn AH, Hafele C, Shalev A. Thioredoxin‐interacting protein is stimulated by glucose through a carbohydrate response element and induces beta‐cell apoptosis. Endocrinology. 2005;146(5):2397‐2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen J, Saxena G, Mungrue IN, Lusis AJ, Shalev A. Thioredoxin‐interacting protein: a critical link between glucose toxicity and Beta cell apoptosis. Diabetes. 2008;57:938‐944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen J, Hui ST, Couto FM, et al. Thioredoxin‐interacting protein deficiency induces Akt/Bcl‐xL signaling and pancreatic beta cell mass and protects against diabetes. FASEB J. 2008;22:3581‐3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lerner AG, Upton JP, Praveen PV, et al. IRE1alpha induces thioredoxin‐interacting protein to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and promote programmed cell death under irremediable ER stress. Cell Metab. 2012;16(2):250‐264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chutkow WA, Birkenfeld AL, Brown JD, et al. Deletion of the alpha‐arrestin protein Txnip in mice promotes adiposity and adipogenesis while preserving insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2010;59(6):1424‐1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yamada T, Katagiri H, Ishigaki Y, et al. Signals from intra‐abdominal fat modulate insulin and leptin sensitivity through different mechanisms: neuronal involvement in food‐intake regulation. Cell Metab. 2006;3(3):223‐229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sampath C, Srinivasan S, Freeman ML, Gangula PR. Inhibition of GSK‐3beta restores delayed gastric emptying in obesity‐induced diabetic female mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2020;319(4):G481‐G493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim T, Nason S, Holleman C, et al. Glucagon receptor signaling regulates energy metabolism via hepatic Farnesoid X receptor and fibroblast growth factor 21. Diabetes. 2018;67(9):1773‐1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lu B, Chen J, Xu G, et al. Alpha cell Thioredoxin‐interacting protein deletion improves diabetes‐associated hyperglycemia and Hyperglucagonemia. Endocrinology. 2022;163(11):1‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scheen AJ, Paquot N, Lefebvre PJ. Investigational glucagon receptor antagonists in phase I and II clinical trials for diabetes. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26(12):1373‐1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parikh H, Carlsson E, Chutkow WA, et al. TXNIP regulates peripheral glucose metabolism in humans. PLoS Med. 2007;4(5):e158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lei Z, Chen Y, Wang J, et al. Txnip deficiency promotes beta‐cell proliferation in the HFD‐induced obesity mouse model. Endocr Connect. 2022;11(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lawrence MC, McGlynn K, Park BH, Cobb MH. ERK1/2‐dependent activation of transcription factors required for acute and chronic effects of glucose on the insulin gene promoter. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(29):26751‐26759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khoo S, Gibson TB, Arnette D, et al. MAP kinases and their roles in pancreatic beta‐cells. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2004;40(3 Suppl):191‐200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaiser N, Leibowitz G, Nesher R. Glucotoxicity and beta‐cell failure in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2003;16(1):5‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Poitout V, Robertson RP. Minireview: secondary beta‐cell failure in type 2 diabetes‐‐a convergence of glucotoxicity and lipotoxicity. Endocrinology. 2002;143(2):339‐342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Russell MA, Redick SD, Blodgett DM, et al. HLA class II antigen processing and presentation pathway components demonstrated by transcriptome and protein analyses of islet beta‐cells from donors with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2019;68(5):988‐1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu G, Chen J, Jing G, Shalev A. Thioredoxin‐interacting protein regulates insulin transcription through microRNA‐204. Nat Med. 2013;19(9):1141‐1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu G, Chen J, Jing G, Shalev A. Preventing beta‐cell loss and diabetes with Calcium Channel blockers. Diabetes. 2012;61(4):848‐856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ovalle F, Grimes T, Xu G, et al. Verapamil and beta cell function in adults with recent‐onset type 1 diabetes. Nat Med. 2018;24(8):1108‐1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xu G, Grimes TD, Grayson TB, et al. Exploratory study reveals far reaching systemic and cellular effects of verapamil treatment in subjects with type 1 diabetes. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Forlenza GP, McVean J, Beck RW, et al. Effect of verapamil on pancreatic beta cell function in newly diagnosed pediatric type 1 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;329(12):990‐999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang CY, Huang KC, Lu CW, et al. A randomized controlled trial of R‐form verapamil added to ongoing metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(10):e4063‐e4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kerola T, Eranti A, Aro AL, et al. Risk factors associated with atrioventricular block. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e194176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.