Abstract

Physical activity is important for human health. During the Coronavirus pandemic, there has been a significant reduction in physical activity. The same happened for college students due to lockdowns and the disruption of normal life. While many universities and colleges are in small cities in the U.S., few studies have been conducted on college students in small cities in the U.S. This current study focuses on closing the gap of literature and examining the physical activity and health of college students in a small Southern city during the pandemic. The anonymous survey was conducted and data were analyzed using basic statistics and Chi-square analysis. Results suggest that more students realized the importance of exercise, but there is a disconnect between students’ view of exercise and their daily actions. Findings from this study will add to the understanding of the previously identified gap and inform universities on what support they could provide in promoting physical activity and healthy lifestyles to college students. Moreover, the findings could inform public health officials in preparing better public health policies in future health emergencies with awareness of their impact on health and physical activity. Finally, the findings can also help colleges improve their curriculum on physical education to address this widespread health issue.

Keywords: Physical Activity, Health, College Students, Small City, Pandemic

Regular physical activity is one of the most effective ways of improving health and preventing premature death (Warburton et al., 2006). The recent Coronavirus pandemic resulted in disease control measures, including lockdowns, quarantines, mask mandates, and social distancing, which dramatically changed lifestyles, caused reduced physical activity and unhealthy diets, and impacted both the physical and mental health of all people in the world (Ammar et al., 2020; Mattioli et al., 2020). During the Coronavirus pandemic, research has shown significant reductions in physical activity levels as observed in many studies (Diniz et al., 2020; Wilke et al., 2021). A similar trend has been observed among children and adolescents (Neville, et al, 2022). There was also a rising college student population that lacked physical activities and healthy habits. All levels of physical activities, including walking, moderate, vigorous, and total physical activities decreased during the pandemic lockdowns among university students, and the phenomenon was common in many countries such as Australia, Croatia, England, Hungary, Italy, Mexico, Spain, and the U.S. (López-Valenciano, 2020). This followed a trend of less physical activity before the pandemic and research revealed a decrease in physical activity from adolescence to adulthood and during the college years (Bray and Born, 2004; Jung et al., 2008; Crombie et al., 2009; Kwan et al., 2012). Reasons cited for the down-trend of physical activity for students during the pandemic were similar to the general population, including lockdowns in many countries and places, social distancing, disruption of normal life, and confinements. Most of the studies indicated that the national lockdown imposed restrictions on outdoor activities, and this further limited the opportunities for students to exercise. Many students lived in small places with no home exercise equipment or resources, which restricted their ability to exercise indoors. All of the above reasons significantly changed the lifestyle of college students during the pandemic (López-Valenciano, 2020). The caveat was that even among the overall activity reduction trend, students who met the minimum activity recommendations before the pandemic also met the recommendations during the lockdown (López-Valenciano, 2020). This showed the resilience of college students.

However, most studies focused on the population in larger cities or large universities, and few studies have been conducted for college students in small cities and rural areas in the U.S., where there are fewer facilities for physical activities and more isolation of individuals. The World Health Organization declared that the pandemic emergency was over on May 5, 2023. Before life went back to normal, what was the situation of college students’ physical activity during the pandemic in small cities? Was it similar to that of big cities? Thus, this study aims to fill the literature gap by researching college students in a small town in the Southern U.S. to see if their physical activities during the pandemic are similar to those in larger or medium cities.

Our research objectives include evaluating the physical activity and health of college students in a small southern city, identifying differences among student groups with various sexes, races, ethnicities, and incomes during the pandemic, and providing policy guidelines for the university to improve student physical activity and health. Our research questions are as follows: (1) What was college students’ attitude toward exercise? We hypothesize that students were positive toward physical activities since past studies have shown positive attitudes of adolescent students (Subramaniam & Silverman, 2007) and we assume college students would be similar. (2) What was the students’ frequency of exercise? We hypothesize that students had less frequent exercises than recommended by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) during the pandemic due to their busy schedule and the inconvenience of social distancing and other pandemic policies. The CDC recommends 150 minutes of moderate aerobic exercise weekly, and most health officials recommend 30 minutes a day for five days a week. (3) What was the students’ self-health assessment? We hypothesize that most students regarded themselves as healthy since they were young and less vulnerable to illnesses. (4) Were students willing to make positive lifestyle changes? We hypothesize that students were willing to make positive lifestyle changes. (5) Did students’ opinions and practices regarding health and exercise vary based on their biological sex, race, ethnicity, and family income? We hypothesize that there were differences in physical activity and health of college students among different groups, and biological sex, race, ethnicity, and family income contributed to these differences. Past research has shown racial, ethnic, and gender differences in physical activity in general populations and socio-demographic differences in physical activity among school children (Inchley et al., 2005; Saffer et al., 2013) and we assume college students could be similar to the general population and children in this regard.

The findings will inform universities on what support students would need the most in promoting exercise and a healthy lifestyle during the pandemic. Results could also inform public health officials to provide better pandemic policies for college students and the young generation. Last, results can also be beneficial to improve the curriculum of physical education in colleges.

Methods

Our study aims to analyze college students’ physical activity in a small city in Georgia during the pandemic. The Valdosta State University (VSU) is selected due to its location in a small city with no big cities nearby. The student body is very diverse, with 49% of students from minority backgrounds and over half from low-income families. Thus, the university is a great place for this research. VSU shut down in-classroom learning in mid-March of 2020 and went virtual for several months. It reopened all in-person classes in August of 2020, making it one of the earliest universities in the country that reopened during the pandemic. Masks and 6-foot social distancing were required from August 2020 to the Summer of 2021, but the policy was relaxed after August 2021, which resulted in masks and social distancing being optional and all student activities being allowed to resume. However, many students continued to wear masks and keep social distance because the pandemic was not officially declared over until 2023. Overall, the university policy changes may have contributed to changes in physical activities among students. The early shutdown probably decreased student activities, but early reopening may have helped to improve student physical activities. Since this survey was distributed after the pandemic policy was relaxed, with no mark and social distancing mandate, we would like to evaluate the student physical activity level during the latter stage of the pandemic, from October 2022 to March 2023.

In order to achieve this research goal and answer the research questions posted above, an anonymous online survey was developed to collect data. After getting the IRB approval, the survey questionnaire was entered onto Qualtrics, a platform generating anonymous links to share with any respondents to maintain their privacy. The anonymous online survey was distributed to the university community by QR code to students on campus and web links to student email lists. The survey was also shared on university community social media sites (Facebook, Instagram, etc.). The email and social media posts included an informed consent statement which explained to the respondents that their participation is voluntary and anonymous. After reading that, if participants still wanted to take the survey, they would click the anonymous link to take the survey. The first page of the survey displayed another informed consent statement ensuring the respondents that their involvement was voluntary and anonymous, and they could elect to skip any question and stop the survey at any moment.

The survey questions consisted of the following: (1) respondents’ attitude towards exercise; (2) respondents’ frequency of exercise; (3) respondents’ self-health assessment (weight and overall health); (4) respondents’ willingness to make positive lifestyle changes in terms of exercise and weight loss; (5) respondents’ demographic and socioeconomic profile. The survey included multiple choice and Likert scale questions. The exercise questions were modified from the International Physical Activity Questionnaire which was proven to be a validated instrument (Hagströmer et al., 2006). Other questions were added to evaluate students’ attitude toward exercises, self-assessment of health and weight, and their willingness to change their lifestyle. The specific survey questions include: “How often do you get at least 30 minutes of moderate exercise in the last 7 days?”, “How important is exercise to you?”, “How active is your daily activity? What is your overall health?”, “What is your weight?”, “How successful have you made positive lifestyle changes in terms of weight loss?”, “How successful have you made positive lifestyle changes in terms of exercise?”, and demographic questions (ethnicity, race, biological sex, and family income. The survey normally took about 10–15 minutes for the participants to complete. The survey data were collected from October 2022 to March 2023. 522 survey responses were recorded and results were exported into a CSV file. Data was analyzed in SPSS and comparisons among different biological sexes, races, ethnicities, and family incomes were explored.

Since we hypothesize that there are differences in students’ opinions and practice of exercise and health, based on sex, race, ethnicity, and annual family income, Chi-square tests of independence were performed to explore the relationships between the biological sex, ethnicity, race, annual family income, and seven exercise and health variables (importance of exercise, frequency of at least 30 minutes of moderate exercise, active level of daily activity, overall health, Weight, success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of losing weight and exercise).

Results

Based on the Qualtrics data, a total of 522 students clicked on the survey. However, after removing records of people who read the survey, but did not answer any questions, only 468 valid responses were left. Some of them are partially completed and did not answer all questions, but to preserve the integrity of the data, they were kept in the analysis. Descriptive statistics and Chi-Square analysis were performed on the data.

1. Descriptive Statistics

The results in Frequency Table (Table 1) revealed that about one-third (33.8%) of student respondents had at least 30 minutes of moderate exercise less than or equal to once a week, another one-third (34.8%) did it two or three days a week, while only less than 20% (18.2%) did it 4–5 days a week, and 12.2% did it over 5 days a week. When asked about their daily activities, about 37.2% viewed themselves as relatively or mostly sedentary, while only 24.1% thought of themselves as active or most active. About 23.1% viewed themselves in between. The interesting fact was that over 37.6% of the respondents viewed exercise as very or extremely important to them, another 32.1% viewed it as moderately important, and only 3.2% thought it was not important. The descriptive statistics for the variables are in Table 2. It showed a similar story. The mean value of the importance of exercise was 3.17 (on a scale of 1–5), which showed that more students realized the importance of exercise, while their daily activity level only averaged 2.79 (on a scale of 1–5), which suggested more students were sedentary and did not reach the activity level recommended by the CDC. Apparently, there was a disconnect between the students’ positive view of exercises and their real actions. In the meantime, for those who responded to this question, 56.5% of them thought of themselves as being in good and excellent health, and only 21.7% thought of themselves as being not healthy or relatively not healthy.

Table 1.

Combined Frequency Table

| How often do you get at least 30 minutes of moderate exercise in the last 7 days? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | 5 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |

| Between 2–3 days a week (2) | 163 | 34.8 | 34.8 | 35.9 | |

| Between 4–5 days a week (3) | 85 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 54.1 | |

| Greater than or equal to 5 days a week (4) | 57 | 12.2 | 12.2 | 66.2 | |

| Less or equal to one day a week (1) | 158 | 33.8 | 33.8 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 468 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| What is your overall health? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | 1 Poor | 8 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| 2 Below Average | 63 | 13.5 | 19.3 | 21.7 | |

| 3 Average | 71 | 15.2 | 21.7 | 43.4 | |

| 4 Very good | 143 | 30.6 | 43.7 | 87.2 | |

| 5 Excellent | 42 | 9.0 | 12.8 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 327 | 69.9 | 100.0 | ||

| Missing | System | 141 | 30.1 | ||

| Total | 468 | 100.0 | |||

| How successful have you made positive lifestyle changes in terms of weight loss? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | 25 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.3 | |

| I have a healthy weight already | 111 | 23.7 | 23.7 | 29.1 | |

| No | 90 | 19.2 | 19.2 | 48.3 | |

| Somewhat | 63 | 13.5 | 13.5 | 61.8 | |

| Yes | 179 | 38.2 | 38.2 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 468 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| How important is exercise to you? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | 5 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |

| Extremely important (5) | 56 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | |

| Moderately important (3) | 150 | 32.1 | 32.1 | 45.1 | |

| Not at all important (1) | 15 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 48.3 | |

| Slightly important (2) | 122 | 26.1 | 26.1 | 74.4 | |

| Very important (4) | 120 | 25.6 | 25.6 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 468 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| How active is your daily activity? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | 1 Very sedentary | 44 | 9.4 | 11.1 | 11.1 |

| 2 Sedentary | 130 | 27.8 | 32.9 | 44.1 | |

| 3 Average | 108 | 23.1 | 27.3 | 71.4 | |

| 4 Active | 91 | 19.4 | 23.0 | 94.4 | |

| 5 Very active | 22 | 4.7 | 5.6 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 395 | 84.4 | 100.0 | ||

| Missing | System | 73 | 15.6 | ||

| Total | 468 | 100.0 | |||

| How successful have you made positive lifestyle changes in terms of exercise? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | 25 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.3 | |

| I am good at exercising | 56 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 17.3 | |

| No | 128 | 27.4 | 27.4 | 44.7 | |

| Somewhat | 57 | 12.2 | 12.2 | 56.8 | |

| Yes | 202 | 43.2 | 43.2 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 468 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Questions:

| Questions | No. | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Importance of exercise (5 being extremely important) | 469 | 1 | 5 | 3.17 | 1.06 |

| Daily activity level (5 being most active) | 395 | 1 | 5 | 2.79 | 1.089 |

| Overall health (5 being excellent) | 327 | 1 | 5 | 3.45 | 1.02 |

| Weight (1 being overweight) | 469 | 1 | 3 | 1.99 | 0.97 |

| Success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of losing weight (1 being not successful) | 448 | 1 | 4 | 2.45 | 1.08 |

| Success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of exercise (1 being not successful) | 448 | 1 | 4 | 2.1 | 0.96 |

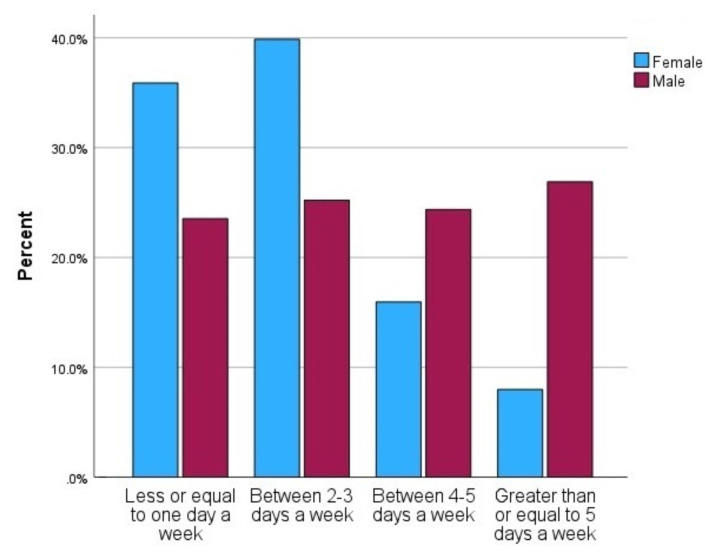

There were differences between biological sex as well. A higher percentage of men viewed exercise as very important than women and a higher percentage of men exercised over 4 days a week for 30 minutes than women (Figures 1 and 2). Interestingly, a higher percentage of men also considered themselves more sedentary and in good or excellent health than women.

Figure 1.

Importance of exercise by sex

Figure 2.

Frequency of at least 30 minutes of moderate exercise

In addition, there were also differences between ethnicity and race. A higher percentage of non-Hispanics thought exercise was very or relatively important than Hispanics, and they had more days with 30 minutes of exercise a week than Hispanics. Regarding the frequency of 30-minute exercise, racial groups ranked from high to low are as follows: Native Americans, Caucasians, Asians, and African Americans.

Finally, students from different income backgrounds had different exercise practices. The group that exercised the most had family incomes between $75,000 and $99,999, followed by those with incomes above $150,000 and between $100,000 and $149,999. In other words, students from mid-middle-class families exercise more than those from high-middle-income or high-income families.

2. Chi-Square Analysis

To further explore the survey data, we investigated if biological sex, age, race, ethnicity, and annual family income impact the opinion of the importance of exercise, the frequency of moderate exercise of at least 30 minutes, the level of daily activity, the overall health, weight, and success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of losing weight and exercise. The Chi-square tests of independence were performed to explore the relationships. Results are explained in the following.

2.1. Chi-Square for biological sex

Chi-square tests of independence were performed to examine the relationships between the biological sex and several variables relating to the respondent’s opinions of exercise and health (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Chi-Square Results:

| Variables | χ2value |

|---|---|

| For biological sex | |

| Importance of exercise | 55.610*** |

| Frequency of at least 30 minutes of moderate exercise | 71.787*** |

| Level of daily activity | 23.403** |

| Overall health | 10.662 |

| Weight | 19.834** |

| Success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of losing weight | 213.351*** |

| Success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of exercise | 224.289*** |

|

| |

| For Hispanic ethnicity | |

| Importance of exercise | 24.773** |

| Frequency of at least 30 minutes of moderate exercise | 41.898*** |

| Level of daily activity | 6.781 |

| Overall health | 5.327 |

| Weight | 24.742** |

| Success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of losing weight | 245.464*** |

| Success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of exercise | 246.425*** |

|

| |

| For race | |

| Importance of exercise | 65.733 |

| Frequency of at least 30 minutes of moderate exercise | 84.258** |

| Level of daily activity | 42.755 |

| Overall health | 35.91 |

| Weight | 43.324 |

| Success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of losing weight | 292.304*** |

| Success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of exercise | 272.395*** |

|

| |

| For annual family income | |

| Importance of exercise | 58.927** |

| Frequency of at least 30 minutes of moderate exercise | 60.561*** |

| Level of daily activity | 34.327 |

| Overall health | 35.327 |

| Weight | 44.764** |

| Success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of losing weight | 237.200*** |

| Success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of exercise | 249.075*** |

Note:

p < .001;

p < .050;

p < .010

Participants were asked how important they think of exercise. The relationship between biological sex and the importance of exercise was significant at the significance level of 0.01, χ2(10, N = 468) = 55.610, p = <.001, which is smaller than 0.01. Thus, there was a significant difference between biological sex and participants’ opinions on the importance of exercise.

In addition, participants reported their level of daily activity and their exercise frequency. The relationship between biological sex and frequency of moderate exercise of at least 30 minutes was significant at the significance level of 0.01, χ2(8, N = 468) = 71.787, p = <.001 (smaller than 0.01). Similarly, the relationship between biological sex and their level of daily activity was also significant at the significance level of 0.01, χ2(8, N = 395) = 23.403, p = .003. Hence, there was a significant difference between participants’ biological sex and their frequency of moderate exercise of at least 30 minutes, and the same is true for biological sex and their level of daily activity.

Regarding the relationship between their biological sex and weight, it was significant at the significance level of 0.01, χ2(6, N = 468) = 19.834, p = .003 (smaller than 0.01). There was a significant difference between biological sex and their opinion of their weight.

Concerning participants’ success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of losing weight, the relationship between this variable and the biological sex was significant at the significance level of 0.01, χ2(8, N = 468) = 213.351, p = <.001 (smaller than 0.01). Similarly, the relationship between biological sex and success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of exercise was significant at the significance level of 0.001, χ2(8, N = 468) = 224.289, p = <.001. Accordingly, there were significant differences between biological sex and success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of weight loss and exercise.

However, the relationship between biological sex and their overall health was not significant at the significance level of 0.05, χ2(8, N = 327) = 10.662, p = .222 (larger than 0.05). There was no significant difference between participants’ biological sex and their overall health.

2.2. Chi-Square for Ethnicity

Chi-square tests of independence were also performed to examine the relationships between Hispanic ethnicity and several variables relating to the respondent’s opinions of exercise and health (see Table 3).

The study found significant relationships between Hispanic ethnicity and various health-related factors:

Importance of Exercise: There was a significant difference between participants’ ethnicity and their opinions on the importance of exercise, χ2(10, N = 468) = 24.773, p = .006.

Frequency of Moderate Exercise: Hispanic ethnicity was significantly related to the frequency of moderate exercise (at least 30 minutes), χ2(8, N = 468) = 41.898, p < .001.

Weight: A significant relationship was found between Hispanic ethnicity and participants’ weight, χ2(6, N = 468) = 24.742, p < .001.

Success in Lifestyle Changes in:

Weight Loss: Hispanic ethnicity significantly influenced success in weight loss, χ2(8, N = 468) = 245.464, p < .001.

Exercise: There was a significant relationship between Hispanic ethnicity and success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of exercise, χ2(8, N = 468) = 246.425, p < .001.

However, no significant differences were found between Hispanic ethnicity and:

Level of Daily Activity: χ2(8, N = 395) = 6.781, p = .560.

Overall Health: χ2(8, N = 327) = 5.327, p = .722.

2.3. Chi-Square for Race

Chi-square tests of independence were performed to examine the relationships between race and several variables relating to the respondent’s opinions and practice of exercise and health. The results displayed the following relationships between participants’ race and various factors.

There was a significant difference between race and the following:

Frequency of Moderate Exercise: There was a significant difference between race and the frequency of moderate exercise (at least 30 minutes), χ2(56, N = 468) = 84.258, p = .009.

-

Success in Lifestyle Changes:

○ Weight Loss: Race significantly influenced success in weight loss, χ2(56, N = 468) = 292.304, p < .001.

○ Exercise: There was a significant relationship between race and success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of exercise, χ2(56, N = 468) = 272.395, p < .001.

Unlike Hispanic ethnicity, race did not significantly influence participants’ opinions on the importance of exercise, χ2(70, N = 468) = 65.733, p = .622.

Similar to Hispanic ethnicity, race did not significantly affect:

Level of Daily Activity: χ2(48, N = 395) = 42.755, p = .687.

Overall Health: χ2(48, N = 327) = 35.910, p = .901.

Weight: χ2(42, N = 468) = 43.324, p = .415.

2.4. Chi-Square for Annual Family Income

Chi-square tests of independence were also performed to examine the relationships between annual family income and several variables relating to the respondent’s opinions and practice of exercise and health. The results revealed significant relationships between participants’ annual family income and various health-related factors:

Importance of Exercise: There was a significant difference between annual family income and opinions on the importance of exercise, χ2(35, N = 468) = 58.927, p = .007.

Frequency of Moderate Exercise: Annual family income significantly influenced the frequency of moderate exercise (at least 30 minutes), χ2(28, N = 468) = 60.561, p < .001.

Weight: A significant relationship was found between annual family income and participants’ weight, χ2(21, N = 468) = 44.764, p = .002.

Success in Lifestyle Changes:

Weight Loss: Annual family income significantly influenced success in weight loss, χ2(28, N = 468) = 237.200, p < .001.

Exercise: There was a significant relationship between annual family income and success in making positive lifestyle changes in terms of exercise, χ2(28, N = 468) = 249.075, p < .001.

However, no significant differences were found between annual family income and:

Level of Daily Activity: χ2(28, N = 395) = 34.327, p = .190.

Overall Health: χ2(28, N = 327) = 35.327, p = .161.

Discussion

This research goal was to analyze the opinions and practices of physical activity and health among university students in small cities in the U.S. during the pandemic. The results will be useful from a public health perspective so universities can address poor health-related habits such as lack of exercise and create better public health policies to reduce the ongoing widespread problems among college students.

Results from this study suggest that most students realized the importance of exercise, possibly credited to positive school education and public campaigns in recent decades. Today’s college students are educated on the benefits of exercise, such as physical competence and mental health as research argued that exercise increases perceptions of physical competence (Lintunen, 1995) and increases mental health and lower depression (Kull, 2002). Moreover, in Western culture, a well-toned body is highly valued for self-presentation and is linked to increased self-esteem through bodily competence, self-determination, and self-acceptance (Biddle et al, 2000). Physical appearance is a key predictor of global self-esteem (Harter, 1994; Fox, 1997). A review of 36 randomized controlled studies found that 78% reported positive effects of exercise on self-esteem or self-concept (Biddle et al, 2000). After all, our survey result is great news for public health, which fought for years to promote physical activity and healthy living and we have evidence to show that college students in the small city have received the message. However, the daily activity level of the survey respondents points to the majority of students being sedentary, which is contrary to students’ own beliefs on health. Thus, there is a disconnect between the students’ view of exercise and their daily actions. In the meantime: over half of the participants who answered the question thought of themselves as being in good and excellent health, and only less than 30% thought of themselves as being not healthy or relatively not healthy. This might suggest that most college students were young and confident about their health and there was not an urgent need for exercise, even though they know of the importance of exercise. Overall, results showed that recent education on physical activity is successful for college students, but translating that into successful practice requires more effort. This is consistent with the survey of Rutgers University students, which concluded that obesity prevalence was more due to a lack of action and not due to a lack of knowledge (Bruzzone et al., 2011). No matter how important the students consider physical activity theoretically, if they do not embrace and act accordingly, it is quite unlikely to see students commit their already busy schedule to exercise and physical activity that really matters in their daily lives. Thus, there is an urgent need to help students put their beliefs into practice and improve their daily lifestyle with more physical activity and exercise. Of course, we understand that, compared to their time before college, students generally reduce their physical activity (Van Dyck et al.). Many variables contributed to this decline, for example, their changes in residency, travel distance to the university, psychosocial aspects, stress, and more time demands by work and study (Van Dyck et al., 2015; Calestine et al., 2017). However, the decrease in exercise has been aggravated due to the Coronavirus pandemic.

At the same time, the difference in biological sexes plays a role in the exercise and health of college students. A lower percentage of females exercise to the level suggested by the CDC than males. In addition, race and ethnicity affect the exercise and health of college students. Compared to non-Hispanic students, a lower percentage of Hispanic students regarded exercise as very important and exercised enough to meet the required level in a week. African Americans had a lower frequency of 30-minute exercise per week than other racial groups. Students with family incomes lower than $75,000 exercised the least, compared to other income groups. Thus, it is recommended to increase the promotion of physical activity among female, Hispanic, African-American, and lower-income students to reduce inequity of physical activity among female, and racial, ethnic, and economically disadvantaged college students.

Overall, the results answered our research questions: 1) Our hypothesis regarding students’ attitudes toward exercise is confirmed, and most students were positive toward physical activities and thought highly of its importance. (2) Our hypothesis on students’ frequency of exercise was confirmed, and they exercised less frequently during the pandemic than what was recommended by the CDC. The CDC recommends 150 minutes of moderate aerobic exercise weekly and most health officials recommend 30 minutes a day for five days a week. However, our results demonstrated that a majority of college students in the small town did not get enough exercise. (3) Our hypothesis on the students’ self-health assessment was confirmed. The majority of students judge themselves as healthy. (4) Our hypothesis on students’ willingness to make positive lifestyle changes was not confirmed. Over half of the students were not successful in making positive lifestyle changes, including both exercise and weight loss. (5) Our hypothesis on the impact of biological sex, ethnicity, race, and family income on health and exercise is confirmed. There were differences in physical activity and health of college students, and biological sex, race, ethnicity, and family income contributed to these differences.

With the above results, our research bridged the gap in the literature by studying the exercise and health of college students in small cities during the pandemic. It pointed out that college students in the small city also lacked physical activities, similar to those in large and medium cities. It provided more insights on this topic given the rising problems of obesity and lack of exercise among college students during the pandemic.

As for the implications for practice and policy, it is recommended that universities in small cities implement measures to encourage students to increase and maintain adequate levels of physical activity to meet the recommendation of the CDC. It would be helpful to provide more incentives to students, such as group exercise programs, competitions, awards, and prizes. For example, a 12-week walking program supplemented with a pedometer, computer educational program, and weekly e-mails for college employees was a successful worksite health initiative which improved the health and wellness of its employees and reduced healthcare costs (Haines et al., 2007). Over two hundred college students completed another pedometer intervention program and increased walking and other health benefits except weight management (Jackson & Howton, 2008). Similar programs could be implemented for college students as well. Moreover, research has shown that highlighting a disconnect regarding health in an active choice intervention influenced intentions to increase physical activity but did not result in significant behavior changes at the 2–4-week follow-up (Landais et al., 2023). Thus, to make changes in physical activity behavior, universities need to have a long-term strategy. One effective example was a 10-week wellness program for employees at a university in the southeastern U.S., which evaluated the impact on physical fitness and mental well-being, using the Disconnected Values Model (DVM) as its framework (Anshel et al., 2010). The DVM emphasized identifying and addressing inconsistencies between negative habits and personal values to drive health behavior change. This program included fitness coaching and a DVM-based orientation (Anshel et al., 2010). Analyses showed significant improvements in physical fitness and mental well-being from pre- to post-intervention, supporting the effectiveness of the DVM as a cognitive-behavioral strategy for workplace health promotion (Anshel et al., 2010). Furthermore, given the limited resources in the small cities, universities could provide better facilities and more hours for exercise at those facilities to maintain social distancing and improve the activity conditions. In the case of health emergencies and pandemics, online professional physical guidance would be extremely helpful for university students. Public health officials need to provide better public health policy during the pandemic for college students and the younger generation, for example, encouraging them to exercise more outdoors, especially during the pandemic, rather than asking them to stay at home which reduces exercise and increases isolation and mental health problems. Lastly, developing better physical education curricula in universities could prepare college students with more awareness and practices of physical activity and health. Overall, the success of employee wellness programs in educational institutions depends on strategic planning and conducting a comprehensive needs assessment to address the diverse interests and backgrounds of employees. For example, a U.S. university surveyed over four hundred employees on their interest in 15 wellness program areas, focusing on physical, nutritional, and lifestyle wellness (Tapps et al., 2016). Results revealed high overall interest with lifestyle programming being more favored than physical activity and nutrition (Tapps et al., 2016). Strength training, stress reduction, and overall wellness management were the top preferences (Tapps et al., 2016). These findings highlight the importance of tailoring wellness programs to participants’ specific needs to enhance engagement and long-term effectiveness and that is the key to the success of future college student health programs.

Limitations

While surveys are a common tool in social and behavior studies, data were collected from self-reports. Despite the data collection being anonymous, it is susceptible to cognitive bias. Future studies with objective tools would be more reliable in assessing activities (accelerometers, smart watches, etc.). In addition, our survey participants were similar to the university student population profile, but not exactly the mirror image. Based on the U.S. News & World Report (2024), VSU has 33.3% male, 66.7% Female, 37% Black, and 89% non-Hispanic. Our sample has 63% female, 26% male, 11% without reporting their gender, 20% Black, 88% non-Hispanic, and 11.9% without reporting their race. Considering about 11% did not report either gender and a similar percentage about race, our sample is probably close to the university population. Despite the limitations, the findings provide insight into exercise and health among college students during the pandemic in small cities and provide a basis for future studies.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Ammar A, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Trabelsi K, Masmoudi L, Brach M. ECLB-COVID19 Consortium. COVID-19 home confinement negatively impacts social participation and life satisfaction: a worldwide multicenter study. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020;17(17):6237. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anshel MH, Brinthaupt TM, Kang M. The Disconnected Values Model Improves Mental Well-Being and Fitness in an Employee Wellness Program. Behavioral Medicine. 2010;36(4):113–122. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2010.489080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddle S, Fox KR, Boutcher SH, editors. Physical activity and psychological well-being. Vol. 552. London: Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bray SR, Born HA. Transition to university and vigorous physical activity: implications for health and psychological well-being. Journal of American College Health. 2004;52:181–188. doi: 10.3200/JACH.52.4.181-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone G, Nunziato S, Gebizlioglu M, Fagan JM. The psychological disconnect between knowing how to live healthy and actually pursuing a healthy lifestyle. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Calestine J, Bopp M, Bopp CM, Papalia Z. College student work habits are related to physical activity and fitness. International Journal of Exercises Science. 2017;10:1009–1017. doi: 10.70252/XLOM8139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombie AP, Ilich JZ, Dutton GR, Panton LB, Abood DA. The freshman weight gain phenomenon revisited. Nutrition Review. 2009;67:83–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz TA, Christofaro DG, Tebar WR, Cucato GG, Botero JP, Correia MA... & Prado WL. Reduction of physical activity levels during the COVID-19 pandemic might negatively disturb sleep pattern. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11:586157. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox KR. The physical self: From motivation to well-being. Human Kinetics. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Harder DW. In: Self-esteem: The puzzle of low self-regard. Baumeister RF, editor. New York: Plenum; 1994. p. 262. [Google Scholar]

- Hagströmer M, Oja P, Sjöström M. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): a study of concurrent and construct validity. Public health nutrition. 2006;9(6):755–762. doi: 10.1079/phn2005898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines DJ, Davis L, Rancour P, Robinson M, Neel-Wilson T, Wagner S. A Pilot Intervention to Promote Walking and Wellness and to Improve the Health of College Faculty and Staff. Journal of American College Health. 2007;55(4):219–225. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.4.219-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inchley JC, Currie DB, Todd JM, Akhtar PC, Currie CE. Persistent socio-demographic differences in physical activity among Scottish schoolchildren 1990–2002. The European Journal of Public Health. 2005;15(4):386–388. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson EM, Howton A. Increasing Walking in College Students Using a Pedometer Intervention: Differences According to Body Mass Index. Journal of American College Health. 2008;57(2):159–164. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.2.159-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung ME, Bray SR, Ginis KAM. Behavior change and the freshman 15: tracking physical activity and dietary patterns in 1st-year university women. Journal of American College Health. 2008;56:523–530. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.5.523-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan MY, Cairney J, Faulkner GE, Pullenayegum EE. Physical activity and other health-risk behaviors during the transition into early adulthood: a longitudinal cohort study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;42:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kull M. The relationships between physical activity, health status and psychological well-being of fertility-aged women. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2002;12(4):241–247. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2002.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landais LL, Jelsma JG, Verhagen EA, Timmermans DR, Damman OC. Awareness of a disconnect between the value assigned to health and the effort devoted to health increases the intention to become more physically active. Health psychology and behavioral medicine. 2023;11(1):2242484. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2023.2242484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lintunen T. Self-perceptions, fitness, and exercise in early adolescence: A four-year follow-up study. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- López-Valenciano A, Suárez-Iglesias D, Sanchez-Lastra MA, Ayán C. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on University Students’ Physical Activity Levels: An Early Systematic Review. Front Psychology. 2021 Jan 15;11:624567. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.624567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattioli AV, Sciomer S, Cocchi C, Maffei S, Gallina S. Quarantine during COVID-19 outbreak: Changes in diet and physical activity increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2020;30(9):1409–1417. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville RD, Lakes KD, Hopkins WG, Tarantino G, Draper CE, Beck R, Madigan S. Global changes in child and adolescent physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA pediatrics. 2022;176(9):886–894. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Blanco C, Rodríguez-Almagro J, Onieva-Zafra MD, Parra-Fernández ML, Prado-Laguna MDC, Hernández-Martínez A. Physical Activity and Sedentary Lifestyle in University Students: Changes during Confinement Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health. 2020 Sep 9;17(18):6567. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffer H, Dave D, Grossman M, Ann Leung L. Racial, ethnic, and gender differences in physical activity. Journal of human capital. 2013;7(4):378–410. doi: 10.1086/671200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam PR, Silverman S. Middle school students’ attitudes toward physical education. Teaching and teacher education. 2007;23(5):602–611. [Google Scholar]

- Tapps T, Symonds M, Baghurst T, Girginov V. Assessing employee wellness needs at colleges and universities: A case study. Cogent Social Sciences. 2016;2(1) doi: 10.1080/23311886.2016.1250338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- US News & World Report. Valdosta State University; 2024. Retrieved November 24, 2024 from https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/valdosta-state-university-1599. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyck D, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Deliens T, Deforche B. Can changes in psychosocial factors and residency explain the decrease in physical activity during the transition from high school to college or university? International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2015;22:178–186. doi: 10.1007/s12529-014-9424-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton DER, Nicol CW, Bredin SSD. Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. CMAJ. 2006;174:801–809. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke J, Mohr L, Tenforde AS, Edouard P, Fossati C, González-Gross M... & Hollander K. A pandemic within the pandemic? Physical activity levels substantially decreased in countries affected by COVID-19. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18(5):2235. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]