Abstract

K-RAS mutations drive oncogenesis in multiple cancers, yet the lack of druggable sites has long hindered therapeutic development. Here, we use multi-temperature X-ray crystallography (MT-XRC) to capture functionally relevant K-RAS conformations across a temperature gradient, spanning cryogenic to physiological and even “fever” conditions, and show how cryogenic conditions may obscure key dynamic states as targets for new drug development. This approach revealed a temperature-dependent conformational landscape of K-RAS, shedding light on the dynamic nature of key regions. We identified significant conformational changes occurring at critical sites, including known allosteric and drug-binding pockets, which were hidden under cryogenic conditions but later discovered to be critically important for drug-protein interactions and inhibitor design. These structural changes align with regions previously highlighted by large-scale mutational studies as functionally significant. However, our MT-XRC analysis provides precise structural snapshots, capturing the exact conformations of these potentially important allosteric sites in unprecedented detail. Our findings underscore the necessity of advancing tools like MT-XRC to visualize conformational transitions that may be important in signal propagation which are missed by standard cryogenic XRC and to address hard-to-drug targets through rational drug design. This approach not only provides unique structural insights into K-RAS signaling events and identifies new potential sites to target with drug candidates but also establishes a powerful framework for discovering therapeutic opportunities against other challenging drug targets.

Keywords: K-RAS; Multi-temperature X-ray Crystallography (MT-XRC); Room Temperature Crystallography; Oncogenic Mutations; Protein Conformational Dynamics; Allosteric Sites; Structural Biology; Cancer Therapeutics; GTPase; Signal Transduction; Cryogenic vs. Physiological Conditions; Temperature-Dependent Flexibility; Drug Targeting; K-RAS Mutants (G12C, G12D); Molecular Mechanisms; Small GTPases; Structural Plasticity; Inhibitor Design; Conformational Landscape; GTP/GDP Binding

Introduction:

Small GTPases are a class of guanine-nucleotide-binding proteins that act as molecular switches, regulating critical cellular processes such as growth, proliferation, differentiation, and migration in response to extracellular signals (1–3). These proteins transition dynamically between an inactive GDP-bound state and an active GTP-bound state, driven by GDP-GTP exchange and GTP hydrolysis. This activation cycle is tightly regulated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), which facilitate GDP release and GTP binding, and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs), which catalyze the hydrolysis of GTP back to GDP (4,5). The structural changes induced during this cycle are crucial for downstream signaling and the coordination of vital cellular activities (6).

Among the small GTPases, K-RAS (Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog) has garnered significant attention due to its pivotal role in human cancers (7). Mutations in K-RAS are observed in approximately one-third of all malignancies, with substitutions at key residues, such as glycine 12 (G12), leading to its constitutive activation (8,9). This leads to a persistent activation of KRAS’ downstream signaling pathways which drives oncogenesis and makes K-RAS a high-priority therapeutic target (10). However, K-RAS has long been deemed “undruggable” due to its smooth surface and lack of well-defined binding pockets, posing substantial challenges for rational drug design (11). Despite the recent development of mutation-specific inhibitors, such as covalent G12C-targeting compounds, there is still an urgent need for innovative strategies to uncover additional druggable sites and expand therapeutic options (12–14).

Cryogenic crystallography has been the standard tool for elucidating the structural details of small GTPases, including K-RAS, and has provided important insights into their function and inhibitor interactions (15–18). However, this technique has notable limitations. The freezing process immobilizes proteins in static conformations, potentially obscuring biologically relevant structural dynamics and introducing artifacts that may skew interpretations (19–22). As K-RAS function relies on subtle conformational changes within flexible regions such as Switch I, Switch II, and the P-loop, these limitations could hinder the identification of key structural transitions as well as fail to detect critical druggable sites and impede drug development efforts.

To address these challenges, multi-temperature X-ray crystallography (MT-XRC) offers a promising solution by capturing protein structures across a range of temperatures, from cryogenic to physiological and even “fever” conditions (23–25). This approach enables the observation of temperature-dependent conformational dynamics, providing a more accurate representation of the protein’s behavior under physiological conditions (26–28). By revealing hidden structural features, such as transient conformational changes that yield new allosteric pockets, MT-XRC can uncover key regions for inhibitor binding that are not apparent in cryogenic structures (27,28). Previous studies from our laboratory and others have demonstrated the value of room-temperature crystallography in resolving critical conformational differences, offering new insights into protein function and drug binding (29).

In this study, we apply MT-XRC to investigate the structural dynamics of wild-type and mutant K-RAS proteins, focusing on the oncogenic G12C mutant as a paradigmatic example. By analyzing high-resolution structures across a temperature gradient, we reveal a temperature-dependent conformational landscape that sheds light on critical structural features, including strained GDP versus GTP binding, dynamic rearrangements within the classical conformationally-sensitive ‘Switch domains,’ and the adaptability of key allosteric sites. Our findings demonstrate that MT-XRC provides a unique advantage in visualizing dynamic and physiologically relevant conformations, simplifying the identification of allosteric sites, and directly informing inhibitor design. These insights not only shed light on potentially important structure-function features of K-RAS but also establish MT-XRC as a powerful tool for tackling other hard-to-drug targets, paving the way for more effective therapeutic strategies in cancer treatment.

Results:

High-Resolution Room Temperature Crystal Structure of Wild-Type K-RAS Highlights Critical Functional Regions

The room temperature (RT) structure of wild-type (WT) K-RAS bound to GDP was determined at 1.4 Å resolution, which provided striking clarity of its G-domain (residues 1–169), including the functionally important regions such as the P-loop, Switch I and II, and the hypervariable region (HVR). The structure provides a complete and well-defined model of K-RAS at an elevated temperature. This contrasts with many cryogenic structures, which can often suffer from incomplete electron density in flexible or functionally important areas, particularly in the conformationally-sensitive Switch regions (30). Fortunately, the radiation damage profile was similar to that obtained under cryogenic conditions (31), thus allowing the collection of a complete dataset with a single crystal (Table 1).

Table 1.

Crystallization and Data Collection Statistics for Solved K-RAS Structures.

| Data Collection | 8TVK | 8TXK | 8TY2 | 8TXJ | 8TY8 | 8TY9 | 9BL0 | 9NF2 | 9NF5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | P 21 21 21 | P 21 21 21 | P 21 21 21 | P 21 21 21 | P 21 21 21 | P 21 21 21 | P 21 21 21 | R 3: H | P 1 21 1 |

| Resolution range | 26.87 – 1.04 (1.06 – 1.04) | 36.24 – 1.381 (1.43 – 1.38) | 24.79 – 1.408 (1.45 – 1.41) | 30.71 – 1.4 (1.45 – 1.4) | 36.24 – 1.399 (1.44 – 1.4) | 30.93 – 1.426 (1.48 – 1.43) | 50.00–1.70 (1.73–1.7) | 50.00–1.66 (1.7–1.66) | 43.53 – 1.749 (1.79 – 1.75) |

| Unit cell | 39.022 40.545 91.383 90 90 90 | 39.322 42.368 93.405 90 90 90 | 39.41 42.115 92.006 90 90 90 | 39.418 41.207 92.101 90 90 90 | 39.424 41.809 92.088 90 90 90 | 39.423 41.74 92.144 90 90 90 | 40.542 51.944 91.791 90 90 90 | 75.361 75.361 203.864 90 90 120 | 80.37 51.264 83.473 90 99.23 90 |

| Completeness (%) | 94.54 (54.82) | 94.91 (72.61) | 99.56 (95.12) | 99.82 (98.22) | 97.61 (88.57) | 99.92 (99.48) | 96.54 (88.58) | 95.66 (83.13) | 98.45 (93.86) |

| Reflections used in refinement | 66700 (1650) | 31192 (2137) | 30276 (2574) | 30269 (2647) | 30096 (2448) | 29122 (2851) | 21147 (1349) | 49224 (3061) | 67034 (4508) |

| R-work | 0.1886 (0.3640) | 0.1953 (0.3233) | 0.1857 (0.3505) | 0.1885 (0.3426) | 0.1870 (0.3153) | 0.1972 (0.3498) | 0.1835 (0.3447) | 0.1807 (0.4103) | 0.4422 (0.4702) |

| R-free | 0.2044 (0.3941) | 0.2212 (0.3394) | 0.2096 (0.3461) | 0.2082 (0.3244) | 0.2103 (0.3144) | 0.2178 (0.3676) | 0.2144 (0.3935) | 0.1811 (0.3856) | 0.4682 (0.4782) |

| Number of non-hydrogen atoms | 1628 | 1527 | 1498 | 1522 | 1497 | 1496 | 1486 | 3007 | 2914 |

| macromolecules | 1352 | 1352 | 1352 | 1352 | 1352 | 1352 | 1366 | 2719 | 2725 |

| ligands | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 77 | 146 | 154 |

| solvent | 247 | 146 | 117 | 141 | 116 | 115 | 43 | 142 | 35 |

| Protein residues | 169 | 169 | 169 | 169 | 169 | 169 | 169 | 169 | 169 |

| RMS(bonds) | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.017 | 0.009 | 0.008 |

| RMS(angles) | 1.1 | 1.07 | 1.06 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 1.16 | 1.34 | 1.15 | 1.01 |

| Average B-factor | 13.09 | 19.13 | 24.02 | 19.91 | 23.85 | 22.17 | 35.4 | 28.25 | 29.47 |

| macromolecules | 11.9 | 18.4 | 23.32 | 19.01 | 23.13 | 21.52 | 35.3 | 28.15 | 29.84 |

| ligands | 9.12 | 13.1 | 17.61 | 12.81 | 16.73 | 14.84 | 33.07 | 24.68 | 22.68 |

| solvent | 19.83 | 26.43 | 33.11 | 29.21 | 33.21 | 30.82 | 42.83 | 34.51 | 30.38 |

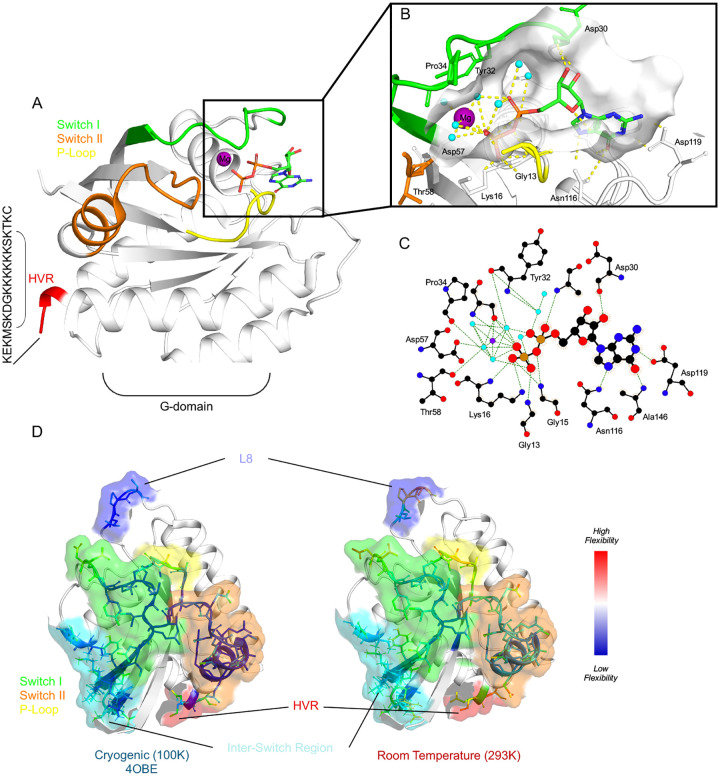

The RT structure provides a detailed view of the nucleotide-binding pocket, revealing the coordination of GDP and its associated magnesium ion (Fig. 1A). The GDP molecule is anchored within the binding pocket via an extensive network of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions. Specifically, the β- and γ-phosphate groups of GDP form key hydrogen bonds with the backbone amides of residues in the P-loop (G10, and S17), while the magnesium ion is coordinated by T35 and D57 within Switch I and Switch II, respectively (10,11). Additionally, hydrophobic contacts involving residues such as A11 and V14 further stabilize the nucleotide (Fig. 1B). Visualization with LigPlot+ (32) highlights the highly conserved nature of these interactions, underscoring their critical role in maintaining nucleotide binding and structural integrity of the active site (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. The Room Temperature (RT) Crystal Structure of K-RAS at 1.4 Å.

A, The G-domain (amino acids 1–169) of WT K-RAS bound to GDP at RT in cartoon representation with Switch I (green) and II (orange), P-loop (yellow), and Hyper Variable Regions (HVR) (red) highlighted, showing clear structural definition across all regions. B, Zoomed-in region of the nucleotide-binding pocket with GDP. Magnesium (purple sphere), coordinating waters (blue spheres), the Switch regions, and the P-loop are shown. C, Schematic representation of the interactions between GDP and WT K-RAS, generated using LigPlot+. The figure highlights key hydrogen bonds (represented as dashed lines) stabilizing the GDP molecule within the nucleotide-binding pocket of K-RAS. The magnesium ion (purple sphere) coordinating the phosphate groups of GDP is also shown. Key residues from K-RAS involved in these interactions are labeled. D, Comparison of the RT, 1.4 Å structure of WT K-RAS with its cryogenic (100K) counterpart. Switch I (green) and II (orange), and P-loop (yellow), (HVR) (red), Inter-Switch (blue), and Loop 8 (dark blue) regions are highlighted. Residues are shown, colored from Blue (lowest) to Red (highest) B-factor values, indicating how flexible the regions are.

Comparing the RT structure of GDP-bound WT K-RAS (Fig. 1D, right) with its cryogenic counterpart (Fig. 1D, left) solved at 100 K (PDB ID: 4OBE) reveals a globally conserved fold, consistent with prior studies that demonstrate the robust architecture of the G-domain (33). However, localized differences in key functional regions are apparent, particularly in the P-loop and the dynamic Switch I and II regions. At cryogenic temperatures, these regions appear more rigid, with lower B-factor values (blue) indicative of constrained atomic motion (Fig. 1D). In contrast, the RT structure reveals increased flexibility, as evidenced by higher B-factor values (red) and greater displacement of residues in these regions (Fig. 1D).

Interestingly, there are many changes that also occur in the Inter-Switch (residues 75–87) region. For example, the P-loop (residues 10–17), which interacts directly with the phosphate groups of GDP, exhibits subtle outward shifts in the backbone atoms of the RT structure, likely reflecting the greater conformational freedom available at physiological temperatures. These shifts result in a slightly expanded nucleotide-binding pocket, which may have functional implications for nucleotide exchange or effector binding. Similarly, Switch I (residues 25–41 and Switch II (residues 57–75) exhibit enhanced conformational variability in the RT structure as measured by atomic B-factors. In the cryogenic structure, Switch I adopts a relatively fixed conformation; however, at RT, Switch I shows additional flexibility, including an opening of the R41 side chain, which plays a critical role in interactions with effector proteins. This suggests that the rigidification at cryogenic temperature may represent an artifact of freezing.

Switch II exhibits even more pronounced conformational changes in the RT structure, with the D57 side chain adopting orientations that are not observed in the cryogenic structure. This dynamic behavior aligns with the functional role of Switch II in facilitating nucleotide hydrolysis and effector interactions. Notably, the increased flexibility of Switch II at RT suggests that cryogenic conditions may mask important intermediate states critical for the GTPase cycle.

Beyond the well-characterized P-loop and Switch regions, the inter-switch region which bridges Switch I and Switch II also exhibits notable structural differences between the RT and cryogenic structures. This region plays a critical role in mediating allosteric communication between these functionally important domains. In the cryogenic structure, the Inter-Switch region adopts a relatively ordered conformation, with backbone and side chain positions closely resembling those observed in prior GDP-bound structures. However, in the RT structure, significant deviations are observed, particularly in the backbone trajectory and orientation of key residues such as T77, G75, and Y86. The increased flexibility of the Inter-Switch region at RT, as reflected in elevated B-factor values, suggests that it may serve as a dynamic hinge, allowing for transient conformations that facilitate signal propagation between the nucleotide-binding pocket and downstream effectors. Notably, the outward displacement of this region is known to interact with Raf1.

These observations highlight the advantages of RT crystallography in capturing physiologically relevant structural dynamics. By providing a more accurate representation of K-RAS in its native-like environment, the RT structure reveals critical features of the protein that are not apparent in cryogenic studies. The enhanced flexibility observed at RT likely reflects the dynamic behavior required for K-RAS function, including its ability to cycle between inactive GDP-bound and active GTP-bound states to interact with downstream signaling effectors. These findings demonstrate the limitations of cryogenic methods and emphasize the importance of studying proteins under conditions that mimic their physiological environments.

Temperature-Sensitive Conformational Shifts in K-RAS G12C

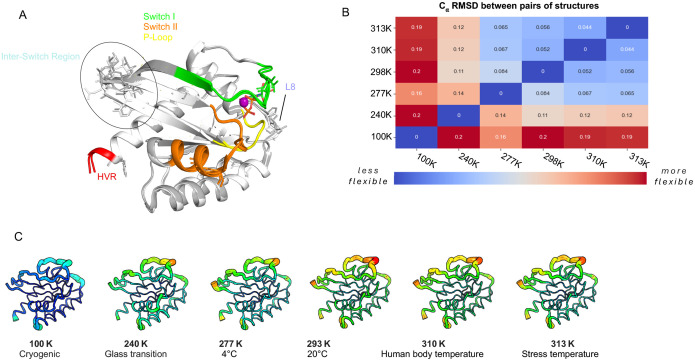

Building on our observations of temperature-dependent flexibility in WT K-RAS and the success in determining the structure at RT, we next examined the K-RAS G12C mutant, a clinically significant variant due to its prevalence in multiple cancers and its unique druggable properties (13). The G12C mutation introduces a reactive cysteine at position 12, altering the nucleotide-binding pocket and nearby regions in ways critical for both its oncogenic function and drug interactions. To assess the structural dynamics of the G12C mutant at RT, we compared it to the RT structure of WT K-RAS. Overall, the global fold remains conserved between the two structures (Fig. 2A). However, the G12C mutation in K-RAS induces structural perturbations that affect key residues involved in nucleotide binding and overall conformational stability. Structural comparisons between the WT and the G12C proteins at room temperature reveal distinct alterations at residues 1, 4, 23–26, 30, 46–51, 121, 122, 126, and 169. Notably, residues within Switch I (23–26) and Switch II (46–51) exhibit shifts in backbone positioning, which may influence their interactions with guanine nucleotides and effector proteins. Residues 1, 4, and 30 also display subtle deviations, suggesting potential alterations in nucleotide coordination. Additionally, minor rearrangements in the α3-helix (residues 121, 122, 126, and 169) suggest a redistribution of structural strain that could impact the dynamic behavior of the protein.

Figure 2. Multi-temperature Crystallography (MT-XRC) of the K-RAS G12C Mutant.

A, Overlay of the WT K-RAS (white) and K-RAS G12C mutant (grey) structures. Switch I (green), Switch II (orange), P-loop (yellow), (HVR) (red), Inter-Switch (blue), and Loop 8 (dark blue) regions are highlighted. Structural residues differences in Inter-Switch region are shown and circled. B, Table displaying the RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) for the G12C mutant K-RAS structures solved at various temperatures (100K, 240K, 277K, 293K, 310K, and 313K). Blue represents the lowest and yellow the highest B-factor flexibility. C, Structures of the G12C K-RAS proteins are drawn in cartoon putty with rainbow coloring with Blue representing the lowest and red the highest B-factor values. The size of the tube also reflects the B-factor, with larger tubes indicating higher B-factors.

These various changes illustrate how the G12C substitution perturbs key regulatory elements within K-RAS, with structural deviations propagating to regions critical for nucleotide exchange and effector binding. To further explore temperature dependent conformational changes of this important K-RAS oncogenic mutant, we determined its high-resolution crystal structures across a temperature gradient, ranging from cryogenic (100K, −173°C) to physiological (310K, 37°C) and fever-like (313K, 40°C) conditions. A comparison chart (Fig. 2B) summarizes the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values for K-RAS G12C structures over these temperature ranges. This shows a clear increase in structural variability as the temperature increases. At 100K, the RMSD values are relatively low, indicating minimal structural change and reduced flexibility. As temperatures increase, the RMSD values for the G12C structures grow, showing a more pronounced increase in RMSD at higher temperatures. At 313K, G12C structures exhibit the highest RMSD values, reflecting greater conformational shifts in the G12C mutant compared to the WT protein. This is visually illustrated in a cartoon putty representation of the G12C mutant at different temperatures (Fig. 2C), in which we see that the P-loop, Switch I, and Switch II regions exhibit increased flexibility at higher temperatures. The width and color intensity of the putty representation correspond to the B-factor values, with thicker and more intensely colored regions indicating increased atomic motion and flexibility. At cryogenic temperatures, these regions appear relatively rigid. As the temperature increases, the P-loop, Switch I, and Switch II regions become more prominent indicating dynamic structural mobility. The enhanced flexibility in these regions suggests that the increased temperature induces conformational changes in K-RAS that can be important for interactions with downstream effectors and potential therapeutic drugs. These structural changes can also have significant consequences for drug design, as they highlight regions that may be more accessible or altered at physiological temperatures, thus offering new opportunities for targeting K-RAS G12C with specific inhibitors.

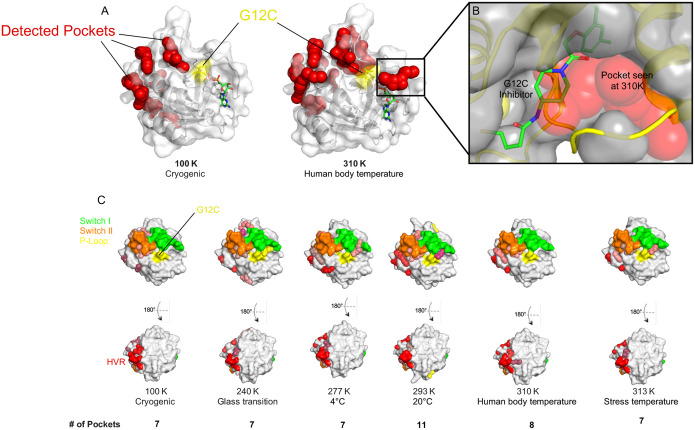

Temperature-Dependent Pocket Formation in K-RAS G12C Structures

Given the temperature dependent structural perturbations induced by the G12C mutation, we sought to determine whether the structures for this oncogenic mutant over the temperature landscape would reveal novel binding pockets that potentially could be exploited for therapeutic intervention. Using FPocketWeb (34), we found that the RT structure had a total of 11 pockets, exceeding the number observed at both colder and warmer temperatures (Fig. 3C). This data suggests that temperature plays a critical role in the conformational plasticity of the G12C mutant. At cryogenic temperatures, seven pockets were detected, primarily aligning with known allosteric sites observed in previous studies (35). However, at physiological temperature, an additional eighth pocket emerged, corresponding to the groove that led to the development of the first covalent K-RAS G12C inhibitors (13). An overlay of our physiological-temperature structure for K-RAS G12C with the published structure for the K-RAS G12C-inhibitor complex (PDB: 4LUC) at this site shows that the pocket observed at 310K, 37°C closely matches the groove occupied by early covalent inhibitors (under stress conditions at 313K, 37°C this groove disappears) (Fig. 3B) (13).

Figure 3. Temperature-dependent pocket formation in the K-RAS G12C structures.

A, K-RAS G12C structures at cryogenic (100 K) and physiological (310 K) temperatures are presented with detected pockets shown using FPocketWeb (red spheres), with residue 12 being highlighted in yellow. B, Overlay of the cryogenic K-RAS G12C-inhibitor complex (yellow, cartoon) (PDB: 4LUC) with the 310K K-RAS G12C structure (grey, surface). The pocket that appears at 310K (red spheres) is the groove the inhibitor exploits to bind. C, Surface representations of K-RAS G12C at various temperatures, with Switch I (green), Switch II (orange), P-loop (yellow), (HVR) (red), Inter-Switch (blue), and Loop 8 (dark blue) regions highlighted. Unique pockets are shown as colored spheres.

The presence of additional binding pockets at RT raises intriguing possibilities for targeting alternative transient allosteric sites that may not be apparent under more static conditions. These findings underscore the critical role of temperature in structural studies of K-RAS, suggesting that an optimal temperature during data collection may offer a more accurate representation of potential drug-binding sites and facilitate the design of next-generation inhibitors targeting oncogenic K-RAS.

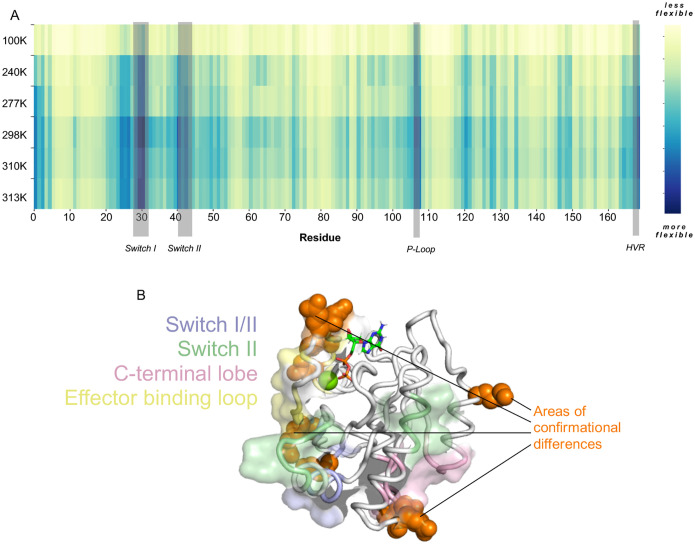

Conformational Analysis and Key Residue Flexibility Across Temperature Gradients

Given the importance of temperature-dependent structural dynamics in uncovering cryptic binding sites, we investigated whether specific regions of K-RAS G12C exhibit unique flexibility patterns that could indicate alternative allosteric or druggable sites. To quantify these temperature-driven conformational shifts, we analyzed the root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of K-RAS G12C bound to GDP across different temperatures, plotting per-residue flexibility to identify regions of enhanced atomic displacement (36). Structural regions of interest are highlighted in shaded grey areas, indicating potential transient pockets or alternative drug-binding surfaces that may be occluded under cryogenic conditions (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. Conformational Analysis and Key Residue Conformations for K-RAS G12C Bound to GDP.

A, Root mean square fluctuation heat map (RMSF) of K-Ras G12C bound to GDP across different temperatures plotted per residue. More flexible regions are in blue and key structural regions are labeled and indicated in grey. B, Structure of KRAS G12C at 310K shown with known pocket regions colored. Switch I/II pocket (blue), Switch II pocket (green), C-terminal lobe pocket (pink), and the Effector binding loop pocket (yellow). Residues exhibiting significant conformational differences at 310K (human body temperature) compared to other temperatures are highlighted as orange spheres.

Our analysis identified several key regions that exhibit significant deviations in flexibility as the temperature increases. Residues within the known allosteric and drug pockets showed marked increases in B-factor values at increased temperatures, reflecting a more dynamic structural landscape. Intriguingly, these regions correspond to allosteric and drug-binding sites on K-RAS, as previously predicted from a large-scale mutational screen (35) (Fig. 4B). This finding not only confirms the locations of these critical sites but also provides a structural framework for pinpointing transient allosteric pockets that may serve as alternative therapeutic targets. By mapping these dynamic conformations, our work offers a model for rational drug design that incorporates temperature-dependent structural plasticity. Future studies leveraging high-resolution room-temperature crystallography or molecular dynamics simulations could further refine our understanding of these transient structural elements and their implications for drug development.

Evaluating Binding Mode Stability of Approved K-RAS G12C Inhibitors

To see whether clinically approved K-RAS G12C inhibitors exhibit temperature-dependent binding variations, we determined the structures of K-RAS G12C at RT in complex with Sotorasib and Adagrasib, the first FDA-approved covalent inhibitors targeting this mutation (37, 38). We observed no significant differences in inhibitor binding poses. In all cases, both Sotorasib and Adagrasib consistently engaged the mutant cysteine residue, locking K-RAS into an inactive conformation. This invariance suggests that these inhibitors represent an optimized binding mode that remains thermodynamically favorable across different conditions, likely due to their covalent mechanism of action. Given that these inhibitors irreversibly engage K-RAS G12C, their high binding affinity and structural rigidity likely limit conformational variability, reinforcing why they remain the dominant therapeutic drugs for targeting this mutant variant.

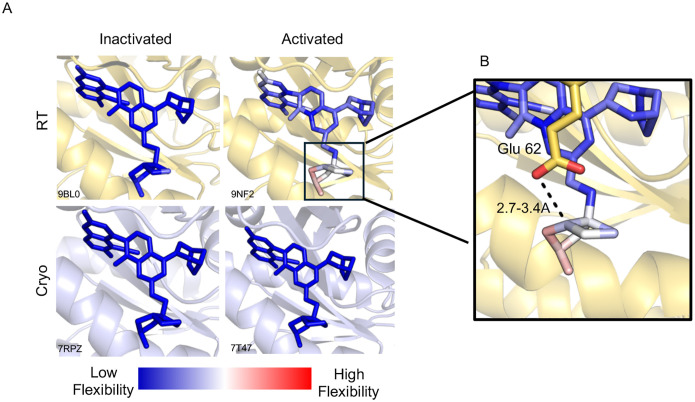

We then examined whether noncovalent inhibitors designed against other K-RAS mutants might exhibit temperature-dependent binding dynamics. Specifically, we analyzed MRTX-1133, a noncovalent inhibitor targeting K-RAS G12D, which is selective for the inactive GDP-bound state (Fig. 5A) (39). Structural comparisons of cryogenic and RT structures of MRTX-1133 bound to active (GMP-PNP-bound) and inactive (GDP-bound) K-RAS G12D revealed notable flexibility within the C2 moiety of the inhibitor, particularly in the activated conformation (Fig. 5B and Fig. S1). This suggests that unlike covalent inhibitors, which irreversibly stabilize K-RAS in a single binding pose, noncovalent inhibitors may exploit dynamic conformational states, potentially leading to varying potency across different conditions. By leveraging this approach, future drug optimization efforts could focus on designing inhibitors that accommodate K-RAS conformational plasticity, maximizing binding efficacy across diverse oncogenic states or targeting either GDP or GTP bound K-RAS.

Figure 5. MRTX-1133 exhibits different flexibility when bound to activated versus inactivated K-RAS G12D.

A, MRTX-1133 complexed to either the signaling-active (GMP-PNP) or signaling-inactive (GDP) bound K-RAS G12D under RT or cryogenic temperatures. MRTX-1133 flexibility is shown with blue (low) to red (high) flexibility. B, A zoomed-in view of the pyrido[4,3-d] pyrimidine substituent at the C2 position of MRTX-1133 showing its flexibility when interacting with Glu 62 (yellow). The H-bonding distance (dashed line) is 2.7–3.4 Å between the C2 component to the residue, as determined by alternative conformations determined with qFit.

Discussion:

In this study, we explored the structural dynamics of WT and mutant K-Ras proteins using multi-temperature X-ray crystallography (MT-XRC), focusing on the implications that temperature-sensitive conformational changes hold for new drug discovery. Mapping allosteric sites through MT-XRC is becoming an increasingly important tool in drug discovery, especially for targets that were once deemed undruggable. This technique makes it possible to capture structural states that emerge exclusively at physiological or elevated temperatures, providing a foundation for targeting proteins that have eluded conventional inhibitor strategies. By incorporating temperature-dependent structural studies into early-stage drug discovery, we can gain deeper insights into the conformational landscapes that drive protein function. Our findings provide new insights into the flexibility and variability of K-RAS, which are necessary for gaining a comprehensive understanding of its function in signaling pathways and for designing new targeted inhibitors.

We determined the high-resolution RT structure of GDP-bound WT K-RAS at 1.4 Å resolution, capturing temperature-dependent structural features in the nucleotide-binding pocket, the Switch I and II domains, and the P-loop. These regions exhibited enhanced flexibility at RT compared to their cryogenic counterparts, suggesting that cryogenic conditions may mask conformational states relevant to K-RAS function. Importantly, we observed that the nucleotide-binding pocket showed subtle shifts in residue positions, particularly in the P-loop (residues 10–17) and Switch I (residues 25–41). These dynamic regions are essential for the ability of K-RAS to transition between active and inactive states, which is critical for signaling.

When comparing the structure of WT K-RAS with that of the oncogenic G12C mutant at RT, we noted significant structural perturbations in several key regions, including residues 1, 4, 23–26, 30, 46–51, 121, 122, 126, and 169. These changes suggest that the G12C mutation induces conformational alterations that could influence nucleotide exchange and effector binding, as well as its known effects on GTP hydrolysis, key processes in K-RAS-driven oncogenesis. Our temperature-dependent studies further revealed that the G12C mutant exhibits increased structural variability at higher temperatures, highlighting the role of temperature in modulating protein dynamics and drug-binding landscapes.

One of the most intriguing consequences of this study is the potential role that temperature-dependent crystallography can play in new drug discovery. By analyzing the structure of K-RAS G12C across a temperature gradient from cryogenic (100K) to physiological (310K) and fever-like (313K) conditions, we observed that structural flexibility increased with temperature. This is particularly evident in regions like the P-loop, Switch I, and Switch II, which are crucial for GTP binding, hydrolysis, and effector interactions. These findings emphasize the importance of studying proteins at physiologically relevant temperatures, as temperature-dependent dynamics can reveal cryptic drug-binding sites that may not be apparent under cryogenic conditions. The temperature-induced conformational changes may help explain why some inhibitors fail or succeed in targeting specific K-RAS oncogenic mutants, highlighting the need to consider protein flexibility in drug design.

For example, using MT-XRC, we identified additional druggable pockets in the G12C mutant that were not visible in the cryogenic structures, including the pocket targeted by the FDA-approved covalent K-RAS G12C inhibitors, Sotorasib and Adagrasib. Intriguingly, these regions correspond to known allosteric and drug-binding sites on K-RAS, as previously identified in a screen of 20,000+ mutations (35). While mutational studies highlight functionally important residues, MT-XRC crystallography offers a powerful complement to this approach by providing precise structural snapshots, capturing the exact conformations of these critical allosteric sites in unprecedented detail. This structural insight enables a deeper understanding of how to target transient allosteric sites, which may play a role in drug resistance or aid in the development of next-generation inhibitors. Given that MT-XRC crystallography reveals a greater number of biologically relevant conformations, it offers a more accurate representation of the protein’s dynamic landscape, essential for designing inhibitors that can adapt to different conformational states of K-RAS.

Although our current study focused on the G12C mutation of K-RAS, other mutations such as G12D, which occur in a wide variety of cancers, will be important to examine in future studies. The addition of G12D data to our structural analysis could provide valuable insights into the broader conformational landscape of K-RAS oncogenic mutants, which will be critical for developing inhibitors that can target multiple K-RAS mutations effectively. We envision future studies where G12D is incorporated into our current framework, either by extending the current analysis or through additional mutagenesis experiments to further assess its impact on K-RAS structure and function.

Our findings underscore the importance of temperature in studying the structure of K-RAS and offers a compelling argument for the integration of MT-XRC crystallography into drug discovery efforts. By revealing conformational flexibility and new druggable pockets that are otherwise obscured at cryogenic temperatures, these studies open up new possibilities for the rational design of inhibitors targeting K-RAS. Thus, in the future we plan to further investigate how temperature-dependent structural changes influence the binding of both covalent and non-covalent inhibitors, as well as explore the potential for targeting alternative allosteric sites in G12C and other K-RAS mutants, and ultimately leverage the dynamic structural insights provided by RT crystallography to examine other GTP-binding proteins that function as molecular switches in cell signaling,.

Experimental Procedure:

Purification of K-RAS Bound to GDP

Plasmids of both Wild-type and mutant versions of human K-RAS 4B, amino acids 1–169 of human K-RAS 4B, were obtained from Addgene (#111849, #159439, #111850, #111848) which contained a hexa-histidine-tagged recombinant form of human K-RAS (amino acids 1–169) and were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells. An overnight culture of bacteria was grown at 37°C and used to inoculate 4L of Terrific broth containing 30 mg/ml kanamycin until an OD600 of 0.4–0.6 was reached. When the cultures reached an OD600 of 0.4–0.6, they were cooled, induced with 0.5 mM IPTG, and grown overnight at 16°C. The cells were then pelleted the next morning and either used immediately or stored at −80°C.

The cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, and 5 mM imidazole) containing protease inhibitors (Leupeptin, Aprotinin, Pepstatin A, AEBSF at 1 mg/mL 1000X stocks). Resuspended cells were lysed with two passes through an Emulsiflex at 15,000 psi, 4°C. After lysis, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol (βME) was added to the lysate. Debris was removed by ultracentrifugation at 35K, 4°C for 1 hour in a Ti45 rotor. The supernatant was removed and incubated with 5 mL of packed Cobalt Agarose Beads (GoldBio) with end-over-end rotating for an hour before being applied to a column, allowed to settle, and washed 10 CVs with a lysis buffer containing 2 mM βME. The bound protein was then eluted using 5 CVs of elution buffer (20 mM Tris 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole) and dialyzed in 3.5k MWCO Snakeskin dialysis tubing (Thermo Fisher Scientific) overnight in dialysis buffer containing 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 5 mM imidazole, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 0.5 mM EDTA. 1 mg GDP per 20 mg K-RAS and 1 mg of hexa-histidine-tagged TEV protease was added before dialysis.

The cleaved protein was then applied to a 5 mL HisTrap™ FF Column (Cytiva) to remove any TEV protease and un-cleaved protein. The protein solution was diluted five-fold into dilution buffer containing 50 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0 before applying it to an anion exchange column (2X Q HiTrap FF 5 mL connected in tandem) with a 50–500 mM salt gradient (including 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0). The protein containing peaks were combined and concentrated before being applied to a Superdex 75 10/300 GL size exclusion chromatography column equilibrated in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT buffer.

Purification of K-RAS G12D bound to GMPPNP

The same procedure for K-RAS G12D bound to GDP was followed until after the Q column chromatography was completed (GMPPNP was used instead of GDP before dialysis). At this point, 1.5 mL of ion exchange-purified RAS protein was mixed with 3 mg of GMPPNP (~4 mM final). EDTA was added to a final concentration of 25–30 mM. After incubation for 1 hour at RT, the reaction buffer was exchanged for phosphatase buffer (32 mM Tris, 20 mM Ammonium Sulfate, 0.1 mM ZnCl2 pH = 8.0) by dialysis using a 10kDa MWCO Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassette (MWCO 10,000 Da). Thirty units of Calf Intestinal Phosphatase (CIP, NEB) was then added with 2 mg of GMPPNP. After a 1-hour incubation at 22 °C, MgCl2 was added to the final concentration of 30 mM. The mixture was incubated on ice for 15 min before being concentrated using a Amicon-4 concentration (10,000 MWCO) to ~700 μL. Finally, the solution was applied to a Superdex 75 10/300 GL for size exclusion chromatography (buffer includes 20 mM HEPES 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2) and the purified protein was concentrated before flash freezing and being stored at −80°C. HPLC analysis was done to verify the nucleotide status as previously descripted (46).

Crystallography of K-RAS bound to GDP and GMPPNP

For crystallization of K-RAS bound to GDP and MRTX-1133, following gel filtration, the purified protein was concentrated to 20, 30, and 40 mg/mL before MRTX-1133 was added in 4-fold molar excess. The protein and drug were then centrifuged at high speed to remove any aggregates. Crystals were grown using hanging drop vapor diffusion in 24 well trays in mother liquor containing 0.1 M Bis Tris pH=5.5, 0.1 M NaOAc pH 3.0–5.6, 8% v/v 2-propanol, and 24% PEG 4000. Similar conditions were used to obtain crystals of K-RAS bound to GDP and Sotorasib or Adagrasib (Medchemexpress).

For K-RAS bound to MRTX-1133 and GMPPNP, following gel filtration, the purified protein was concentrated to ~18 mg/ml before MRTX-1133 was added in 3-fold molar excess. The samples were then centrifuged at high speed to remove aggregates. Crystals were also grown using hanging drop vapor diffusion in 24 well trays in mother liquor containing 25% PEG, 100 mM ammonium acetate, 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH=4.2–6.0).

The crystals were then analyzed at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) HPBio MX & FlexX beamline at cryogenic and room temperature. The data was processed using HKL2000 (40) and Phenix (41) and phased against PDB ID: 7RPZ (39). These structures were then visualized using PyMOL (42) and validated using MolProbity (43) and wwPDB validation software before being deposited into the PDB. The flexability of MRTX-1133 was examined using qFIT (44).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by NIH grant to RAC EY034867 from the National Eye Institute. SD acknowledges support from NSF GFRP and the Sloan Foundation. X-ray crystallography was conducted at the Center for High-Energy X-ray Sciences (CHEXS), supported by the National Science Foundation (BIO, ENG and MPS Directorates) under award DMR-1829070, and the Macromolecular Diffraction at CHESS (MacCHESS) facility, by 1-P30-GM124166-01A1 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health, and by New York State’s Empire State Development Corporation (NYSTAR). This research also used resources of the National Synchrotron Light Source II, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Brookhaven National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-SC0012704. We would also like to thank Kevan Shokat for providing us with MRTX-1133.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare NO competing interest.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability:

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported K-RAS structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). All other relevant data are available upon request from the corresponding author. Software used in the analysis includes PyMOL, CCP4 (45), PHENIX, which are available through their respective distribution channels. Experimental materials, including mutant plasmids, are available upon request for non-commercial research purposes.

References:

- 1.Vetter IR, Wittinghofer A. The Guanine Nucleotide-Binding Switch in Three Dimensions. Science. 2001;294(5545):1299–1304. doi: 10.1126/science.1062023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bos JL. Ras-like GTPases. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1997;1333(2):M19–M31. doi: 10.1016/S0304-419X(97)00015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wennerberg K, Rossman KL, Der CJ. The Ras superfamily at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(5):843–846. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bos JL, Rehmann H, Wittinghofer A. GEFs and GAPs: Critical Elements in the Control of Small G Proteins. Cell. 2007;129(5):865–877. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherfils J, Zeghouf M. Regulation of Small GTPases by GEFs, GAPs, and GDIs. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(1):269–309. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malumbres M, Barbacid M. RAS oncogenes: the first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):459–465. doi: 10.1038/nrc1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jancík S, Drábek J, Radzioch D, Hajdúch M. Clinical relevance of KRAS in human cancers. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:150960. doi: 10.1155/2010/150960. Epub 2010 Jun 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson MW, Reynolds SH, You M, Maronpot RM. Role of Proto-oncogene activation in carcinogenesis. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1992;98:13–24. doi: 10.1289/ehp.929813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prior IA, Hood FE, Hartley JL. The Frequency of Ras Mutations in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2020;80(14):2969–2974. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-3682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stephen AG, Esposito D, Bagni RK, McCormick F. Dragging ras back in the ring. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(3):272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox AD, Fesik SW, Kimmelman AC, Luo J, Der CJ. Drugging the undruggable RAS: Mission possible? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(11):828–851. doi: 10.1038/nrd4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ostrem JML, Shokat KM. Targeting KRAS G12C with Covalent Inhibitors. Annu Rev Cancer Biol. 2022;6:49–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-041621-012549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostrem JM, Peters U, Sos ML, Wells JA, Shokat KM. K-Ras(G12C) Inhibitors Allosterically Control GTP Affinity and Effector Interactions. Nature. 2013;503(7477):548–551. doi: 10.1038/nature12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lito P, Solomon M, Li LS, Hansen R, Rosen N. Allele-specific inhibitors inactivate mutant KRAS G12C by a trapping mechanism. Science. 2016;351(6273):604–608. doi: 10.1126/science.aad6204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skoulidis F, et al. Sotorasib for Lung Cancers with KRAS p.G12C Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2371–2381. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jänne PA, et al. Adagrasib in Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring a KRASG12C Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:120–131. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maurer T, Garrenton LS, Oh A, et al. Small-molecule ligands bind to a distinct pocket in Ras and inhibit SOS-mediated nucleotide exchange activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(14):5299–5304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116510109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welsch ME, Kaplan A, Chambers JM, et al. Multivalent small-molecule Pan-RAS inhibitors. Cell. 2017;168(5):878–889.e29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keedy DA, van den Bedem H, Sivak DA, Petsko GA, Ringe D, Wilson MA, Fraser JS. Crystal cryocooling distorts conformational heterogeneity in a model Michaelis complex of DHFR. Structure. 2014;22:899–910. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer M, Shoichet BK, Fraser JS. One Crystal, Two Temperatures: Cryocooling Penalties Alter Ligand Binding to Transient Protein Sites. ChemBioChem. 2015;16(11):1560–1564. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson MC, Cascio D, Phillips GN, et al. Temperature-Dependent Structural Changes in Bacteriophage HK97 Capsids. Structure. 2006;14(7):1079–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skaist Mehlman T, Biel JT, Azeem SM, Nelson ER, Hossain S, Dunnett L, Paterson NG, Douangamath A, Talon R, Axford D, Orins H, von Delft F, Keedy DA. Room-temperature crystallography reveals altered binding of small-molecule fragments to PTP1B. Elife. 2023. Mar 7;12:e84632. doi: 10.7554/eLife.84632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keedy DA, et al. Mapping the Conformational Landscape of a Dynamic Enzyme by Multi-Temperature and XFEL Crystallography. eLife. 2015;4:e07574. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ringe D, Petsko GA. Study of protein dynamics by X-ray diffraction. Methods Enzymol. 1986;131:389–433. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(86)31041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearce NM, Krojer T, Bradley AR, et al. A multi-temperature crystallographic study of endothiapepsin: insights into the role of conformational heterogeneity in ligand binding. IUCrJ. 2017;4(Pt 3):306–317. doi: 10.1107/S2052252517004150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fraser JS, Clarkson MW, Degnan SC, Erion R, Kern D, Alber T. Hidden alternative structures of proline isomerase essential for catalysis. Nature. 2009;462:669–673. doi: 10.1038/nature08615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fraser JS, van den Bedem H, Samelson AJ, Lang PT, Holton JM, Echols N, Alber T. Accessing protein conformational ensembles using room-temperature X-ray crystallography. PNAS. 2011;108:16247–16252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111325108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fenwick RB, van den Bedem H, Fraser JS, Wright PE. Integrated description of protein dynamics from room-temperature X-ray crystallography and NMR. PNAS. 2014;111:E445–E454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323440111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milano SK, Huang Q, Nguyen TT, Ramachandran S, Finke A, Kriksunov I, Schuller DJ, Szebenyi DM, Arenholz E, McDermott LA, Sukumar N, Cerione RA, Katt WP. New insights into the molecular mechanisms of glutaminase C inhibitors in cancer cells using serial room temperature crystallography. J Biol Chem. 2022. Feb;298(2):101535. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101535. Epub 2021 Dec 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pantsar T. The current understanding of KRAS protein structure and dynamics. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2019. Dec 26;18:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2019.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gotthard G, Aumonier S, De Sanctis D, Leonard G, von Stetten D, Royant A. Specific radiation damage is a lesser concern at room temperature. IUCrJ. 2019. Jun 12;6(Pt 4):665–680. doi: 10.1107/S205225251900616X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laskowski R A, Swindells M B (2011). LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model., 51, 2778–2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunter J.C., Gurbani D., Ficarro S.B., Carrasco M.A., Lim S.M., Choi H.G., Xie T., Marto J.A., Chen Z., Gray N.S., & Westover K.D., In situ selectivity profiling and crystal structure of SML-8–73-1, an active site inhibitor of oncogenic K-Ras G12C, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 (24) 8895–8900, 10.1073/pnas.1404639111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kochnev Y., Durrant J.D. FPocketWeb: protein pocket hunting in a web browser. J Cheminform 14, 58 (2022). 10.1186/s13321-022-00637-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weng C., Faure A.J., Escobedo A. et al. The energetic and allosteric landscape for KRAS inhibition. Nature 626, 643–652 (2024). 10.1038/s41586-023-06954-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carugo O, Pongor S. A normalized root-mean-square distance for comparing protein three-dimensional structures. Protein Sci. 2001. Jul;10(7):1470–3. doi: 10.1110/ps.690101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.FDA. 2021. FDA grants accelerated approval to sotorasib for KRAS G12C mutated NSCLC. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-sotorasib-kras-g12c-mutated-nsclc. [Google Scholar]

- 38.FDA. 2022. FDA grants accelerated approval to adagrasib for KRAS G12C mutated NSCLC. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-adagrasib-kras-g12c-mutated-nsclc. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang W., et al. 2021. Discovery of MRTX1133: A non-covalent, selective inhibitor of KRAS G12D. J. Med. Chem. 64(24): 18645–18659. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Otwinowski Z. and Minor W., “ Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode “, Methods in Enzymology, Volume 276: Macromolecular Crystallography, part A, p.307–326, 1997, Carter C.W. Jr. & Sweet R. M., Eds., Academic Press; (New York: ). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Macromolecular structure determination using x-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in phenix. Liebschner D., Afonine P. V., Baker M. L., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Croll T. I., Hintze B., Hung L. W., Jain S., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R. D., Poon B. K., Prisant M. G., Read R. J., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C., Sammito M. D., Sobolev O. V., Stockwell D. H., Terwilliger T. C., Urzhumtsev A. G., Videau L. L., Williams C. J., Adams P. D.. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 75, 861–877 (2019). doi: 10.1107/S2059798319011471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2r3pre, Schrödinger, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams CJ, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Prisant MG, Videau LL, Deis LN, Verma V, Keedy DA, Hintze BJ, Chen VB, Jain S, Lewis SM, Arendall WB 3rd, Snoeyink J, Adams PD, Lovell SC, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: More and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 2018. Jan;27(1):293–315. doi: 10.1002/pro.3330. Epub 2017 Nov 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riley BT, Wankowicz SA, de Oliveira SHP, et al. qFit 3: Protein and ligand multiconformer modeling for X-ray crystallographic and single-particle cryo-EM density maps. Protein Sci. 2021;30(1):270–285. doi: 10.1002/pro.4001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agirre J, Atanasova M, Bagdonas H, et al. The CCP4 suite: integrative software for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 2023;79(Pt 6):449–461. doi: 10.1107/S2059798323003595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hannan JP, Swisher GH, Martyr JG, Cordaro NJ, Erbse AH, Falke JJ. HPLC method to resolve, identify and quantify guanine nucleotides bound to recombinant ras GTPase. Anal Biochem. 2021. Oct 15;631:114338. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2021.114338. Epub 2021 Aug 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported K-RAS structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). All other relevant data are available upon request from the corresponding author. Software used in the analysis includes PyMOL, CCP4 (45), PHENIX, which are available through their respective distribution channels. Experimental materials, including mutant plasmids, are available upon request for non-commercial research purposes.