Summary

Room temperature superconductivity has become the tireless pursuit of scientists due to its epoch-making significance. Inspired by the recently predicted high superconductivity in LiP2H14, we identify a new superconductor MgP2H14 by substituting Li with Mg and prove its stability. The superconducting critical temperature (Tc) and electron-phonon coupling (EPC) parameters (λ) of MgP2H14 under 280 GPa are predicted to be ∼166 K and ∼1.65, respectively; the high superconductivity of MgP2H14 mainly arises from the strong electron-phonon interaction between H 1s electrons and the H-associated vibration. Furthermore, in hydrogen-based superconductors, the hydrogen sublattice will gain more electrons by doping extra metal atoms or replacing the original metals with higher valence electrons metals. However, if these electrons do not form newly occupied states on the hydrogen energy level near the Fermi level, the superconductivity will not improve further. Our findings provide clues for designing and modulating the superconductivity.

Subject areas: Condensed matter physics, superconductivity, Photon-electron interaction

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Doping electrons in hydride superconductors will cause H to gain more electrons

-

•

If the doped electrons fail to increase the H-PDOS, Tc won’t be improved

-

•

In the case of similar atomic masses in hydrides, low are favorable for EPC

-

•

Tc of MgP2H14 benefits from the coupling between H-associated vibration and H electron

Condensed matter physics; Superconductivity; Photon-electron interaction

Introduction

The breakthrough of room temperature superconductivity barrier is bound to bring unprecedented innovation in the energy field. According to the Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) theory,1 metallic hydrogen was predicted to be a potential room temperature superconductor.2 However, the pressure required for realizing hydrogen metallization is exceptionally high and difficult to achieve.3 As an alternative route, chemical pre-compression proposed by Ashcroft holds that introducing another element into hydrogen will chemically pre-compress the system under certain circumstances, allowing the hydride to enter the metallic phase earlier than the metallic hydrogen and retain a certain degree of superconductivity.4 Based on this principle, a series of hydrogen-dominant high-temperature superconductors were predicted, and some were successfully synthesized in the past 20 years,5,6,7,8,9,10 which has rekindled the hope to realize room temperature superconductivity and has sparked enthusiasm for the search for more promising superconducting materials in hydrides.

As the available chemical space expands and additional degrees of freedom become possible, ternary hydrides are gaining increasing attention to increase Tc and enhance stability over a wider pressure range.11 In 2020, Li et al. identified that the Tc of LiP2H14 reaches up to 169 K at 230 GPa.12 As the electron donor, Li atoms play an important role in stabilizing the crystal structure and enhancing the phonon-mediated superconductivity of the Li-P-H system. Traced back to the simplified Hopfield expression ,13 where N(Ef) is the calculated electronic density of states (DOS) at the Fermi level, is the mean square of the electron-phonon matrix element averaged over the Fermi level, M is the atomic mass, and is the mean square of the phonon frequencies. Normally, heavier atoms might suppress superconductivity due to their low Debye temperature.14 But sometimes, heavier atoms tend to be accompanied by lower phonon frequencies (soft phonons), which may improve the strength of the electron-phonon coupling (EPC) and thus enhance the Tc.15 For example, the phonon frequency of LiP2H14 was greatly reduced and its Tc was improved after substituting Li with Be or Na atoms, Tc (LiP2H14) < Tc (BeP2H14) < Tc (NaP2H14). Inspired by this result, we try to replace the Li with heavier atoms to see if the superconductivity can be further improved. In this paper, we replaced Li in LiP2H14 with Mg, K, Ca, Rb, and Sr to calculate their phonon dispersion curve at 200, 240, and 300 GPa. However, only MgP2H14 is found to be dynamically stable at 300 GPa.

Under an appropriate chemical environment, introducing extra electrons via metal doping can enable the antibonding states of H2 or H3 molecules to accept electrons and achieve molecular dissociation; in this case, the energy of H electrons will be closer to the Fermi level, which will give rise to an increased H-derived DOS at the Fermi level and thus improve the H-based superconductor.16 Mg atoms have one additional valence electron compared with Li atoms; hence, Mg substitute for Li in LiP2H14 is equivalent to doping electrons in the system. Besides, Mg and Be atoms have the same number of valence electrons, but Mg is less electronegative, which may be beneficial for the hydrogen lattice to gain more electrons and hence stabilize the structure under lower pressure and improve the superconductivity.16,17 MgP2H14 may be a promising superconductor with Tc higher than NaP2H14 and LiP2H14 since it doped with more electrons. With this wonderful expectation, we investigated the stability, electronic properties, EPC, and superconductivity of MgP2H14 systematically.

Computational methods

The first principles based on the density functional theory (DFT)18 and density functional perturbation theory (DFPT)19 were employed to execute all calculations by using the Quantum ESPRESSO package.20 The exchange-correlation function was parameterized by the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)21 model to describe the electron interactions. The Mg 2s22p63s2, P 3s23p3, and H 1s1 configurations were treated as valence electrons. The first-order potential perturbation and dynamical matrices were calculated using DFPT on an irreducible 4 × 4 × 4 q-point mesh. The norm-conserving pseudopotentials22 were used with a kinetic energy of 80 Ry and Monkhorst-Pack k meshes with a grid spacing of 2π × 0.02 Å−1 (16 × 16 × 16) are adopted to achieve a good convergence. A denser k-point mesh of 32 × 32 × 32 was employed to calculate the electron-phonon matrix elements. The ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD)23 simulation with NVT (N for the number of particles, V for volume, and T for temperature) ensemble and Nose-Hoover thermostat was performed to prove its thermodynamic stability in 300 K, the time step was 2fs, the primitive cell was expanded to 2 × 2×2. The setting of the exchange-correlation function, valence electrons, pseudopotentials, and energy cutoff in AIMD simulation are consistent with the DFT calculation above. The crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP)24 was exploited to describe the pair interactions by using the LOBSTER code.25

The isotropic Migdal-Eliashberg (ME) equation26,27,28 was employed to calculate the superconducting gap and Tc by using the electron-phonon Wannier (EPW) code.29 The denser homogeneous k-point mesh of 64 × 64 × 64 and q-point mesh of 16 × 16 × 16 were employed to solve the isotropic ME equation during the Wannier interpolation. Twenty-three atomic orbitals of MgP2H14 (consisting of H-s, Mg-s, P-s, and P-p orbitals) were used to construct the maximally localized Wannier functions (MLWF).30

More computational details for calculating the superconducting parameters can be seen in the supplemental information. Phonon spectra and phonon DOS in Figures S1 and S2 are calculated by using the CASTEP code (more computation details can be seen in the caption of Figures S1 and S2),31 all the rest of the phonon properties are calculated by using the Quantum ESPRESSO package.

Results and discussions

Lattice structure and stability

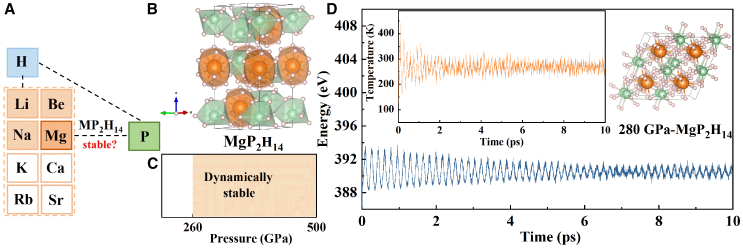

By substituting the Li atom in LiP2H14 with M (M = Mg, K, Ca, Rb, Sr), we investigated the dynamical stability of five kinds of MP2H14 by calculating the phonon dispersion curves under 200 , 240 , and 300 GPa, respectively (see Figures 1A and S1). However, for several specific pressure points (200, 240, and 300 GPa) we calculated, except for MgP2H14 that is dynamically stable under 300 GPa, the phonon spectra of other MP2H14 systems exhibit a large number of imaginary modes (see Figure S1). Based on this, we conduct a detailed study on MgP2H14.

Figure 1.

Crystal structure and stability of MgP2H14

(A) The stability of MP2H14 (M = Li, Be, Na, Mg, K, Ca, Rb, Sr).

(B) Crystal structure of MgP2H14 with the space group of at 280 GPa, consisting of P-centered H9 cages and Mg-centered H14 cages.

(C) MgP2H14 is dynamically stable in the pressure range of 260–500 GPa, the detailed data of phonon spectra can be found in the supplemental information.

(D) The total free energy and temperature as a function of time during the ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulation (lasting for 10 ps at 300 K).

The optimized structure of MgP2H14 consists of Mg-centered H14 cages and P-centered H9 cages, without independent H2 units (see Figure 1B), which lays a good foundation for its high superconductivity since many cases have proven that clathrate structure is beneficial to superconductivity.7,32,33 To further explore the dynamical stability of MgP2H14 under pressure, we calculated the phonon spectra and phonon DOS of MgP2H14 at 0, 260, 340, 420, and 500 GPa (see Figures S1A and S2). The results show that there are substantial imaginary modes at 0 and 240 GPa and no imaginary modes at 260, 340, 420, and 500 GPa, indicating that MgP2H14 is dynamically stable in the pressure range of 260–500 GPa but unstable when the pressure is below 240 GPa (see Figure 1C). To determine the thermodynamic stability, AIMD simulations were performed under 280 GPa. As shown in Figure 1D, we observed that all of the atoms only vibrate slightly around their equilibrium positions, the fluctuations of the total free energy and temperature as a function of time are within a narrow range, indicating that MgP2H14 is thermodynamically stable at 300 K under 280 GPa.

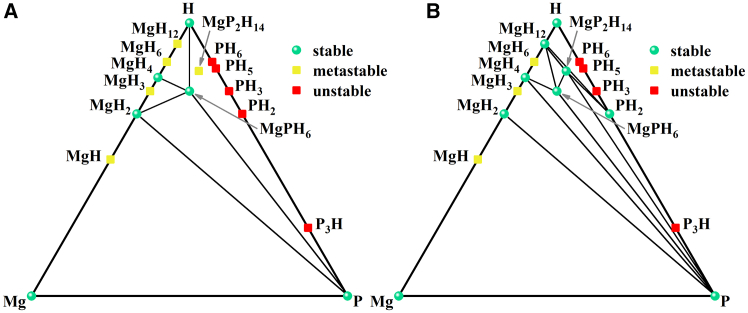

We further explore the thermal stability and the possibility of the experimental synthesis of MgP2H14 by calculating the formation enthalpy to construct the ternary phase diagram at 280 GPa after considering the zero-point energy (ZPE). The ZPE plays an important role in determining the energetics of H-rich materials because of the high vibrational frequency of H. The ΔHzero value of MgP2H14 is defined as follows:

| (Equation 1) |

where ΔH is the formation enthalpy of MgP2H14, which can be estimated as follows:34

| (Equation 2) |

where the H(MgP2H14), H(Mg), H(P), and H(H) are the enthalpy for MgP2H14, pure elements Mg, P, and H at 280 GPa. As shown in Figure 2, MgP2H14 and MgH12 become thermodynamically metastable under 280 GPa once ZPE correction is included, indicating that it is necessary to consider ZPE correction in Mg-P-H systems. MgPH6,35 MgH4,36 and MgH237 are thermodynamically stable whatever with and without ZPE correction. Besides, the results show that MgP2H14 may be synthesized by the elemental Mg, P, and H (or MgH2) as the first two paths listed below, but MgP2H14 is thermally unstable since it may decompose into the energetically more favorable MgH4 or MgPH6 at 280 GPa (the ΔHzero values for corresponding decomposition pathways are listed as follows, herein, only the thermally stable phase was considered as decomposition product), implying a metastable feature. This does not mean that MgP2H14 cannot be synthesized experimentally, after all, 20% of synthesized materials are metastable in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database,38 but the synthesis process of metastable phases may be a bit challenging, such as the synthesis of diamond. In addition, it can be seen that P3H, PH3, PH5, and PH6 have positive formation enthalpy against the elemental P and H, indicating that Mg plays a positive role in stabilizing the P-H systems.

| MgP2H14 → Mg + 2P + 14H–4.281 eV, |

| MgP2H14 → MgH2 + 2P + 12H–0.112 eV, |

| MgP2H14 → MgH4 + 2P + 10H + 0.087 eV, |

| MgP2H14 → MgPH6 + P + 8H + 0.322 eV. |

Figure 2.

The phase diagrams of MgxPyHz relative to elemental Mg, P, H, and binary Mg-H, and P-H systems at 280 GPa

(A) The convex hull after considering the zero-point energy.

(B) The convex hull without considering the zero-point energy. Green solid circles and yellow squares indicate stable and metastable phases, respectively, and red squares indicate unstable phases relative to elemental Mg, P, and H. The source and detailed information of the corresponding structure are summarized in Table S1 in supplemental information.

Electronic structures

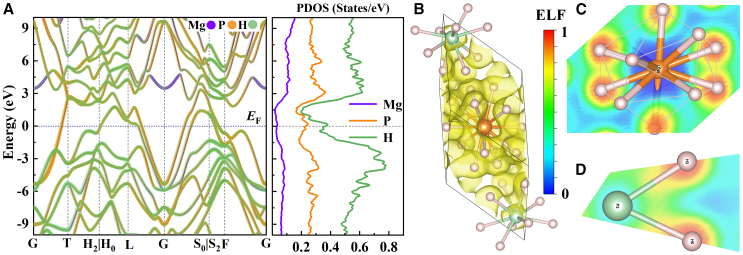

The predicted MgP2H14 system is metallic at 280 GPa as confirmed by the electronic band structure on account of two bands across the Fermi level (see Figure 3), these two bands exactly form obvious σ bands that attributed to the hybridization of P-p and H-s orbitals (see Figure S3). There is a small peak of electronic DOS located slightly above the Fermi level, which is associated with the inflection point of a quite small band fraction close to the L point. The electrons near the Fermi level are mainly contributed by the s orbitals of H atoms and p orbitals of P atoms and there is strong hybridization between them. One of the most typical characteristics of hydrogen-rich superconductors is that their electrons near the Fermi level are mainly contributed by the H atom,39 this feature is particularly obvious in the MgP2H14 system. The orbitals of H in MgP2H14 contribute about 58.4% to the electronic DOS at the Fermi level, while the Mg contributes very little to the electronic DOS near the Fermi level.

Figure 3.

The electronic structure of MgP2H14

(A) The electronic band structure and the partial density of states of MgP2H14 at 280 GPa, the projected weight of each orbital are shown in different colors, and the widths of the lines are proportional to the weights.

(B) The electron localization function (ELF) present in the primitive cell (where the isosurface level is set with 0.5).

(C) The ELF near Mg and H atoms.

(D) The ELF near P and H atoms for MgP2H14 at 280 GPa (the degree of localization is shown in the color column, where the red and blue areas indicate the highest and lowest localized electrons, respectively).

As illustrated intuitively in Figure 3B, the electrons in MgP2H14 are mainly concentrated around H atoms, in addition, Figure 3C shows that the electron localization function (ELF) around P is below 0.5, the ELF around H is above 0.8, the ELF between P and H is about 0.7, and the shared electron pairs are biased toward H atoms, indicating that P-H bond is a polar bond in which ionic and covalent properties coexist. Figure 3D shows that the ELF around Mg is close to 0, indicating that Mg and H are mainly bonded with an ionic bond. A small amount of electron cloud overlap between H and H indicates a weak covalent bond. The Bader charge shows that both Mg and P atoms will donate electrons to H atoms (see Table S2), and Mg atoms donate more electrons than P atoms, indicating that Mg and P atoms may play an important role in stabilizing the hydrogen-rich structure so that MgP2H14 can maintain dynamically stable within a wide range of pressures. As the pressure increases, both the P-H bond and Mg-H bond length decrease gradually, and the Bader charge of P atoms increases significantly however the Mg atoms decrease slightly, which may be due to the P atom being closer to the H atoms and are covalently bonded to each other and hence the distribution of electrons is more susceptible to pressure. In order to further understand the bonding nature, we also exploit the COHP and integrated COHP (ICOHP) to quantify the interatomic interactions. As depicted in Figure 4, the negative and positive projected COHP values indicate bonding and antibonding interactions, respectively, the ICOHP up to the Fermi level can reflect the atom pair interaction strength. We note that P-H, H-H, Mg-P, and Mg-P bonding interactions are obvious, the P-H bonding occupies the largest portion in states below the Fermi level. Besides, the Mg-P and Mg-H interactions near the Fermi level are weaker than the P-H and H-H interactions, indicating that the effect of P-H and H-H interactions on EPC may be larger.35

Figure 4.

The density of states and projected crystal orbital Hamilton populations

(A) The total density of states (TDOS).

(B and C) (B) The projected crystal orbital Hamilton populations (COHP) and (C) its integration ICOHP for MgP2H14 under 280 GPa. Mg-H, P-H, H-H, and Mg-H correspond to the averaging contacts between Mg and H in Mg-centered H14 cages, P and H in P-centered H9 cages, the first coordination shell H-H, and the nearest neighbor Mg-P, respectively.

(D and E) The TDOS for MP2H14 (M = Li, Be, Mg, Na) under 280 and 400 GPa.

(F and G) The projected electronic density of states of H near the Fermi level in the NaP2H14 (HNa), MgP2H14 (HMg), BeP2H14 (HBe), and LiP2H14 (HLi) under 280 and 400 GPa.

As shown in Figure 5, the calculated Fermi surface (FS) displays that there are two bands across the Fermi level, which form the hole-like Fermi-surface sheets, indicating that the predominant carrier type influencing superconductivity is holes and the electronic transport properties should largely rely on its anionic electrons. The Fermi velocities of the n = 1 band are significantly larger than that of the n = 2 band. Moreover, we can see that the two metallic bands are highly dispersive along G-T-H2, G-S0, and S2-F-G paths, but a quite small fraction of the n = 1 band shows an inflection point close to the L point near the Fermi level, similar to the “flat band-steep band” scenario, which provides a nearly vanishing Fermi velocity to part of the conduction electrons and thus favorable for the formation of Cooper pairs.40,41 The Fermi-surface nesting function could describe the degree of parallelism for a set of FSs. On the very parallel FSs, the electronic wave vectors are linked in large quantities by the same phonon wave vectors, which improve the effective coupling and is beneficial for high superconductivity.42 Regrettably, except for a high peak at G point, the Fermi nesting function of the entire Brillouin zone in MgP2H14 is relatively small (see Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Fermi surface (FS) and its nesting function

(A) The FS of MgP2H14 presents in the first Brillouin zone under 280 GPa. The relative Fermi velocity υF on FS is represented by the color scale, where the red and blue color stands for the high and low Fermi velocities, respectively.

(B and C) The FS sheet for the two bands (n = 1, 2).

(D) The FS nesting function ξ along the high-symmetry path.

Electron-phonon coupling and superconductivity

To determine the superconducting critical temperature, we solved the Allen-Dynes modified McMillan equation (AD)14,43 firstly, the Tc of MgP2H14 is predicted to be 155 K, which is higher than that of LiP2H14 (solving by AD). As shown in Figure 6, the optical modes at high frequency are mainly contributed by the lightest H atoms, while the heavier Mg and P atoms play an important role in the phonon modes below 650 cm−1. The Eliashberg spectral function α2F(ω) and electron-phonon integral λ(ω) show that the EPC of MgP2H14 is mainly contributed by high- and medium-frequency vibrational modes of H (account for 61%), indicating the coupling between the H-associated vibration and electrons from H 1s orbitals determines the superconductivity of MgP2H14. By mapping the mode-resolved phonon linewidth onto the phonon spectra, we found a significantly soft mode (A) with a large at L point near 380 cm−1. As the pressure increases, this soft mode gradually disappears (see Figures S4 and S5). In order to illustrate the origin of the phonon softening and large phonon linewidth at L point, we display the vibrational modes of this soft mode in Figure 6D. The A mode (the single degenerate state symmetric to the principle axis) with a vibrational frequency of ∼380 cm−1 at the L point is mainly associated with the bending vibration of the H sublattice, the vibration of the P atoms is almost negligible. In order to study the pressure dependence of superconductivity, we also calculated the superconductivity of MgP2H14 under 350 GPa and 400 GPa. As shown in Figure 7A, both the Tc and λ of MgP2H14 decrease with increasing pressure, besides, the decline is more pronounced in the pressure range of 280–350 GPa, which may be related to the disappearance of the soft mode, particularly the soft mode in the L high-symmetry point.

Figure 6.

Phonon properties and electron-phonon coupling

(A) Phonon dispersion curves with the projection of phonon linewidth using the color scale.

(B) Eliashberg spectral function α2F(ω) as well as the integrated EPC parameter λ(ω) of MgP2H14 at 280 GPa.

(C) Phonon density of states projected on Mg, P, and H atoms.

(D) Vibrational patterns for phonon modes A (indicated by the pink arrow), where the aqua arrows represent the direction of atomic vibration.

Figure 7.

Superconductivity under pressure (μ∗ = 0.10)

(A) the critical superconducting temperature Tc and EPC strength λ as a function of pressure.

(B) The superconducting energy gap as a function of temperature under 280 GPa.

Considering that the total λ of MgP2H14 is up to 1.65, the McMillan equation is not suitable for predicting the Tc of the system with EPC higher than 1,43 we also calculated the Tc by solving the isotropic ME equation through the MLWF interpolation approach since the ME equation usually gives a better description for systems with strong EPC.44 As shown in Figure S6, the Wannier-interpolated electron band structure matches well with that calculated by using the DFT calculation, which can serve as evidence for good interpolation results and ensure the accuracy of subsequent calculation results. By solving the isotropic ME equation, the maximum value of the superconducting gap is calculated to be ∼30 meV (see Figure 7B), MgP2H14 is predicted to be a potential high-temperature superconductor with an estimated Tc of 166 K with a typical Coulomb pseudopotential parameter μ∗ = 0.1 at 280 GPa.

For comparison, the EPC parameter λ, the logarithmic average phonon frequency , the electronic DOS at the Fermi level (N(Ef)), and the Tc of MP2H14 (M = Mg, Na, Be, Li) are summarized in Table 1. The λ and ωlog of MgP2H14 change by about 50% when pressure increases from 280 to 400 GPa, indicating EPC strength and phonon frequencies are strongly affected by pressure. and are calculated to quantify the contribution of electrons and phonons to the EPC, respectively, the results show that both and increase with the increase of pressure. Compared with LiP2H14 under 400 GPa, the higher superconductivity observed in MgP2H14 under 400 GPa may be related to its higher N(Ef). However, at 400 GPa, the Tc and λ of MgP2H14 are significantly lower than that of NaP2H14, two reasons may explain this result well. Firstly, NaP2H14 possesses a higher H-PDOS (H-projected DOS) at the Fermi energy (EF) as shown in Figure 4G, which is beneficial for superconductivity.39 Secondly, the ωlog of NaP2H14 is much lower than MgP2H14, thus we can deduce that the may be lower and the λ may be higher according to the Hopfield expression mentioned in the introduction.

Table 1.

The calculated EPC parameter λ, the first moment of Eliashberg function , square root of the average square phonon frequencies 1/2, logarithmic average frequency ωlog, DOS at Fermi level, and superconducting critical temperature Tc for MgP2H14, LiP2H14, BeP2H14, and NaP2H14 under pressure, Tc is obtained from solving the Allen-Dynes modified McMillan equation (herein, we default f1f2 = 1 when λ < 1) and isotropic Migdal Eliashberg equations, with the typical Coulomb pseudopotential μ∗ = 0.10

| System | P |

λ |

|

1/2 |

ωlog |

N(Ef) |

TcAD |

f1f2TcAD |

TcME |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (GPa) | (K) | (K) | (K) | (states/Ry/fu) | (K) | (K) | (K) | |||

| MgP2H14 | 280 | 1.65 | 1281 | 1481 | 1072 | 6.43 | 133 | 154 | 166 | this work |

| 350 | 1.12 | 1691 | 1870 | 1464 | 6.43 | 120 | 130 | – | this work | |

| 400 | 1.02 | 1840 | 2030 | 1578 | 6.54 | 114 | 122 | – | this work | |

| NaP2H14 | 400 | 1.45 | – | – | 1101 | 6.28 | 139 | – | 159 | Ref.10 |

| BeP2H14 | 400 | 1.13 | – | – | 978 | 5.73 | 90 | – | 99 | Ref.10 |

| LiP2H14 | 400 | 0.85 | – | – | 1494 | 4.96 | 84 | – | 90 | Ref.10 |

| 300 | 1.06 | – | – | 1350 | 5.48 | 112 | – | 125 | Ref.10 | |

| 230 | 1.69 | – | – | 956 | 6.08 | 143 | – | 169 | Ref.10 |

As shown in Table 2, Mg/Be elements have one additional valence electron than Na/Li elements and could donate more electrons to the hydrogen lattice, the calculated Bader charge confirms this. However, the computed results indicate the Tc (BeP2H14)>Tc (LiP2H14), while Tc (NaP2H14)>Tc (MgP2H14) at 400 GPa, which suggests that the larger the number of doping electrons does not necessarily mean higher superconductivity. As shown in Figure 4, an extra valence electron makes the EF of MgP2H14 and BeP2H14 shift toward lower energies than that of LiP2H14 and NaP2H14. If the Fermi level is situated in a narrow pseudogap and the total density of states (TDOS) near the Fermi level is shaped like the graph of a quadratic function, N(Ef) will be strongly influenced via substituting atoms with more valence electrons, thus affecting the superconductivity. However, in the LiP2H14 structure, due to the wide pseudogap and some small peaks near the Fermi level, the DOS at the Fermi level does not increase obviously with the increase of the valence electrons of the metal atoms. Extensive research indicated that introducing extra electrons by doping other metals in a binary hydrogen-rich system with H2 molecules is beneficial to breaking the H2 molecules and thus improving the superconductivity of the system.12,45,46 However, in this work, there are no H2 molecules in the original LiP2H14 system, besides, the introduction of extra electrons does not greatly improve the TDOS and H-PDOS at the Fermi level, moreover, Mg and Na have similar masses, but the ωlog of Na is much smaller than that of Mg, which is conducive to large EPC parameter, those may be the reason why the superconductivity has not been further improved after replacing Na with Mg in NaP2H14.

Table 2.

The Bader charge (e) of MgP2H14, NaP2H14, BeP2H14, and LiP2H14 at 280 and 400 GPa

| System |

MgP2H14 |

NaP2H14 |

BeP2H14 |

LiP2H14 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure | Mg | P | Na | P | Be | P | Li | P |

| 280 GPa | +1.4636 | +1.0269 | +0.6570 | +1.1580 | +1.6699 | +1.1625 | +0.7888 | +1.3984 |

| 400 GPa | +1.4221 | +1.4353 | +0.6357 | +1.5537 | +1.6558 | +1.6035 | +0.7637 | +1.8527 |

Conclusions

A novel ternary hydride MgP2H14 with clathrate structures was identified by substituting the Li atom in LiP2H14 with the Mg atom. The phonon calculation shows that MgP2H14 is dynamically stable in the 260–500 GPa pressure range. The formation enthalpy calculation verified that MgP2H14 is thermodynamically metastable. Remarkably, the EPC strength (λ ≈ 1.65) and Tc (∼166 K) of MgP2H14 at 280 GPa are comparable to that of the LiP2H14 at 230 GPa. The interaction between the high- and medium-frequency vibrations associated with the hydrogen sublattice and the electrons induces strong EPC, resulting in high-temperature superconductivity. Considering the superconductivity of MP2H14 (M = Mg, Na, Be, Li), the number of valence electrons of each element, and the number of electrons that hydrogen lattice gained comprehensively, we find that doping with more electrons does not necessarily enhance the superconductivity of the system. When trying to improve the superconductivity of a hydrogen-rich system by introducing extra electrons by doping metal elements or substituting an atom with one possessing different valence electrons, the existence form of H in the parent system, the position of the Fermi level, the changing trend of DOS near the Fermi level, as well as the size of the pseudogap should be considered comprehensively. Supposing the introduction of extra electrons greatly improves the TDOS and H-PDOS at the Fermi level or greatly reduces the mean square of the phonon frequencies, the superconductivity will be improved, otherwise, it is unable. These results provide some clues to guide the exploration of novel high-temperature superconductors.

Limitations of the study

The results of this paper are predicted under the harmonic approximation, without going beyond the harmonic approximation to test whether there is phonon renormalization at 280 GPa and if this renormalization changes the value of the Tc. The superconducting critical temperature is calculated by solving the isotropic ME equation, the role of anisotropic effect is not further considered.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and resource requests should be directed to the lead contact, Juan Gao (gao.juan.xnjd@my.swjtu.edu.cn).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

The lead contact will share all data reported in this paper upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report the original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (no. 2682024ZTPY054). Numerical computations were performed on Hefei Advanced Computing Center.

Author contributions

J.G., writing – original draft, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, conceptualization. Q.-J.L., writing – review & editing, supervision, funding acquisition. D.-H.F., validation, methodology, data curation. Z.-T.L., software, resource, project administration.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Quantum-ESPRESSO | Giannozzi et al.,20 | www.quantum-espresso.org/ |

| Wannier90 | Mostofi et al.,30 | www.wannier.org/ |

| CASTEP | Clark et al.,31 | https://www.castep.org/ |

| LOBSTER | Maintz et al.,25 | http://www.cohp.de/ |

| Electron-Phonon Wannier | Poncé et al.,29 | https://epw-code.org/ |

| FERMISURFER | Kawamura,47 | http://fermisurfer.osdn.jp/ |

Experimental model and study participant details

There is no experimental model and participant in this study.

Method details

Specific methods

The calculations were conducted using the plane wave pseudopotential method implemented in the QUANTUM ESPRESSO package. To simulate the electron-ion interactions, we employed optimized norm-conserving Vanderbilt pseudopotentials (ONCVPSP). The exchange and correlation potential were described using the generalized gradient approximation (GGA-PBE). We set the wave function cutoff energy to 80 Ry and the charge density cutoff energy to 320 Ry, Gaussian smearing is set as 0.02 Ry. A kinetic energy of 80 Ry and Monkhorst-Pack k meshes with a grid spacing of 2π×0.02Å−1 (16 × 16 × 16) are adopted to achieve a good convergence in the self-consistent calculation. The first-order potential perturbation and dynamical matrices were calculated using density functional perturbation theory (DFPT) on an irreducible 4 × 4 × 4 q-point mesh.

Electronic structure calculations

-

•

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were performed using Quantum ESPRESSO.

-

•

The electronic structure was calculated with a plane-wave basis set and an energy cutoff of 80 Ry.

-

•

A Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh of 16×16×16 was used for Brillouin zone integration.

-

•

To estimate Fermi surfaces (FSs) and visualize the results, we used Wannier90 interpolation, followed by visualization with the FERMISURFER software.

-

•

The crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP) was exploited to describe the pair interactions by using the LOBSTER code.

Electron-phonon coupling (EPC) calculation

-

•

Electron-phonon coupling (EPC) was analyzed using the Eliashberg spectral function, and the electron-phonon coupling constant, λ.

-

•

A denser k-point mesh of 32 × 32 × 32 was employed to calculate the electron-phonon matrix elements.

The superconducting transition temperature (Tc) calculation

-

•

The superconducting transition temperature (Tc) was estimated using the Allen Dynes modified McMillan formula.

-

•

The isotropic Migdal-Eliashberg (ME) equation was also employed to calculate the superconducting gap and Tc using the Electron-Phonon Wannier (EPW) code. The denser homogeneous k-point mesh of 64 × 64 × 64 and q-point mesh of 16 × 16 × 16 were employed to solve the isotropic ME equation during the Wannier interpolation. Twenty-three atomic orbitals of MgP2H14 (consisting of H-s, Mg-s, P-s, and P-p orbitals) were used to construct the maximally localized Wannier functions (MLWF).

ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulation

-

•

The ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulation with NVT (N for the number of particles, V for volume, and T for temperature) ensemble and Nose-Hoover thermostat was performed to prove its thermodynamic stability in 300 K, the time step was 2fs, the primitive cell was expanded to 2×2×2.

All computational parameters and methods were selected to optimize the balance between computational cost and accuracy.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Superconducting properties were quantified using Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations with Quantum ESPRESSO. Electronic structures were calculated with a plane-wave basis set and a [specify energy cutoff, e.g., 80 Ry] energy cutoff, using a Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh of [specify grid density, e.g., 16×16×16]. Phonon calculations were conducted using density functional perturbation theory (DFPT), and electron-phonon coupling (EPC) was analyzed via the Eliashberg function and coupling constant λ. The superconducting transition temperature (Tc) was estimated using the Allen Dynes modified McMillan formula and isotropic Migdal-Eliashberg (ME) equation. All computational parameters and methods were optimized for accuracy.

Additional resources

Additional resources, including supplementary data, computational codes, and detailed methodological protocols, are available upon request from the lead contact. All supplementary materials are intended to enhance the reproducibility and transparency of the study, providing comprehensive insights into the experimental and computational approaches employed. For access to these resources, please contact [lead contact, Juan Gao (E-mail: gao.juan.xnjd@my.swjtu.edu.cn)]. The supplementary data include raw and processed data files, input files for computational simulations, and step-by-step protocols for the methodologies described in this study. These resources aim to support further research and validation efforts within the scientific community.

Published: February 7, 2025

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.111969.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Bardeen J., Cooper L.N., Schrieffer J.R. Theory of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 1957;108:1175–1204. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.108.1175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashcroft N.W. Metallic hydrogen: a high-temperature superconductor? Phys. Rev. Lett. 1968;21:1748–1749. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.21.1748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMahon J.M., Morales M.A., Pierleoni C., Ceperley D.M. The properties of hydrogen and helium under extreme conditions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2012;84:1607–1653. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.84.1607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashcroft N.W. Hydrogen dominant metallic alloys: high temperature superconductors? Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004;92 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.187002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drozdov A.P., Eremets M.I., Troyan I.A., Ksenofontov V., Shylin S.I. Conventional superconductivity at 203 kelvin at high pressures in the sulfur hydride system. Nature. 2015;525:73–76. doi: 10.1038/nature14964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Somayazulu M., Ahart M., Mishra A.K., Geballe Z.M., Baldini M., Meng Y., Struzhkin V.V., Hemley R.J. Evidence for superconductivity above 260 K in Lanthanum superhydride at megabar pressures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019;122 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.027001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma L., Wang K., Xie Y., Yang X., Wang Y., Zhou M., Liu H., Yu X., Zhao Y., Wang H., et al. High-temperature superconducting phase in clathrate calcium hydride CaH6 up to 215 K at a pressure of 172 GPa. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022;128 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.128.167001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snider E., Dasenbrock-Gammon N., McBride R., Wang X., Meyers N., Lawler K.V., Zurek E., Salamat A., Dias R.P. Synthesis of yttrium superhydride superconductor with a transition temperature up to 262 K by catalytic hydrogenation at high pressures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021;126:117003. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.117003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou D., Semenok D.V., Xie H., Huang X., Duan D., Aperis A., Oppeneer P.M., Galasso M., Kartsev A.I., Kvashnin A.G., et al. High-pressure synthesis of magnetic neodymium polyhydrides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:2803–2811. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b10439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song X., Hao X., Wei X., He X.L., Liu H., Ma L., Liu G., Wang H., Niu J., Wang S., et al. Superconductivity above 105 K in nonclathrate ternary Lanthanum borohydride below megabar pressure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024;146:13797–13804. doi: 10.1021/jacs.3c14205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang X., Bergara A., Wei X., Song X., Wang L., Sun R., Liu H., Hemley R.J., Wang L., Gao G., Tian Y. Prediction of high-Tc superconductivity in ternary lanthanum borohydrides. Phys. Rev. B. 2021;104 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.104.134501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X., Xie Y., Sun Y., Huang P., Liu H., Chen C., Ma Y. Chemically Tuning Stability and Superconductivity of P−H Compounds. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020;11:935–939. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b03856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopfield J.J. Angular momentum and transition-metal superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 1969;186:443–451. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.186.443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMillan W.L. Transition temperature of strong-coupled superconductors. Phys. Rev. 1968;167:331–344. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.167.331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang Q., Zhang Z., Song H., Ma Y., Sun Y., Miao M., Cui T., Duan D. Ternary superconducting hydrides stabilized via Th and Ce elements at mild pressures. Fundam. Res. 2024;4:550–556. doi: 10.1016/j.fmre.2022.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun Y., Lv J., Xie Y., Liu H., Ma Y. Route to a superconducting phase above room temperature in electron-doped hydride compounds under high pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019;123 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.123.097001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang X., Wei X., Zurek E., Bergara A., Li P., Gao G., Tian Y. Design of high-temperature superconductors at moderate pressures by alloying AlH3 or GaH3. Matter Radiat. Extremes. 2024;9 doi: 10.1063/5.0159590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hohenberg P., Kohn W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 1964;136:B864–B871. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.136.B864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baroni S., de Gironcoli S., Dal Corso A., Giannozzi P. Phonons and related crystal properties from density-functional perturbation theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2001;73:515–562. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.73.515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giannozzi P., Baroni S., Bonini N., Calandra M., Car R., Cavazzoni C., Ceresoli D., Chiarotti G.L., Cococcioni M., Dabo I., et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2009;21 doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/21/39/395502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perdew J.P., Burke K., Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Troullier N., Martins J.L. Efficient pseudopotentials for plane-wave calculations. Phys. Rev. B. 1991;43:1993–2006. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.43.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kresse G., Hafner J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;47:558–561. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.47.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deringer V.L., Tchougréeff A.L., Dronskowski R. Crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP) analysis as projected from plane-wave basis sets. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2011;115:5461–5466. doi: 10.1021/jp202489s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maintz S., Deringer V.L., Tchougréeff A.L., Dronskowski R. Lobster: A tool to extract chemical bonding from plane-wave based DFT. J. Comput. Chem. 2016;37:1030–1035. doi: 10.1002/jcc.24300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Migdal A.B. Interaction between electrons and lattice vibrations in a normal metal. Sov. Phys. - JETP. 1958;7:996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eliashberg G.M. Interactions between electrons and lattice vibrations in a superconductor. Sov. Phys. - JETP. 1960;11:696–702. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.64. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Margine E.R., Giustino F. Anisotropic Migdal-Eliashberg theory using Wannier functions. Phys. Rev. B. 2013;87 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.87.024505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poncé S., Margine E.R., Verdi C., Giustino F. EPW: Electron-phonon coupling, transport and superconducting properties using maximally localized Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2016;209:116–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cpc.2016.07.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mostofi A.A., Yates J.R., Lee Y.S., Souza I., Vanderbilt D., Marzari N. Wannier90: A tool for obtaining maximally-localised Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2008;178:685–699. doi: 10.1016/j.cpc.2007.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark S.J., Segall M.D., Pickard C.J., Hasnip P.J., Probert M.I.J., Refson K., Payne M.C. First principles methods using CASTEP. Z. Kristallogr. 2005;220:567–570. doi: 10.1016/j.cpc.2007.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H., Yao Y., Peng F., Liu H., Hemley R.J. Quantum and classical proton diffusion in superconducting clathrate Hydrides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021;126 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.117002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng F., Sun Y., Pickard C.J., Needs R.J., Wu Q., Ma Y. Hydrogen clathrate structures in rare earth hydrides at high pressures: possible route to room-temperature superconductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017;119 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.107001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolverton C., Ozoliņš V. First-principles aluminum database: Energetics of binary Al alloys and compounds. Phys. Rev. B. 2006;73 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.73.144104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei X., Hao X., Bergara A., Zurek E., Liang X., Wang L., Song X., Li P., Wang L., Gao G., Tian Y. Designing ternary superconducting hydrides with A15-type structure at moderate pressures. Mater. Today Phys. 2023;34 doi: 10.1016/j.mtphys.2023.101086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lonie D.C., Hooper J., Altintas B., Zurek E. Metallization of magnesium polyhydrides under pressure. Phys. Rev. B. 2013;87 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.87.054107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ellinger F.H., Holley C.E., Jr., Mcinteer B.B., Pavone D., Potter R.M., Staritzky E., Zachariasen W.H. The preparation and some properties of magnesium hydride. Chem. Ber. 1955;77:2647–2648. doi: 10.1021/ja01614a094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Z., Cui T., Hutcheon M.J., Shipley A.M., Song H., Du M., Kresin V.Z., Duan D., Pickard C.J., Yao Y. Design Principles for High-Temperature Superconductors with a Hydrogen-Based Alloy Backbone at Moderate Pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022;128 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.128.047001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie H., Yao Y., Feng X., Duan D., Song H., Zhang Z., Jiang S., Redfern S.A.T., Kresin V.Z., Pickard C.J., Cui T. Hydrogen pentagraphene like structure stabilized by hafnium: a high-temperature conventional superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020;125 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.217001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang H.M., Zhu Q., Blatov V.A., Oganov A.R., Wei X., Jiang P., Li Y.L. Novel Topological Motifs and Superconductivity in Li-Cs System. Nano Lett. 2023;23:5012–5018. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c00875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Z., Zhuang Q., Tian F., Duan D., Song H., Zhang Z., Li F., Li H., Li D., Cui T. Proposed superconducting electride Li6C by sp-hybridized cage states at moderate pressures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021;127 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.127.157002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sukmas W., Tsuppayakorn-aek P., Pinsook U., Ahuja R., Bovornratanaraks T. Roles of optical phonons and logarithmic profile of electron-phonon coupling integration in superconducting Sc0.5Y0.5H6 superhydride under pressures. J. Alloys Compd. 2022;901 doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.163524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allen P.B., Dynes R.C. Transition temperature of strong-coupled superconductors reanalyzed. Phys. Rev. B. 1975;12:905–922. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.12.905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flores-Livas J.A., Boeri L., Sanna A., Profeta G., Arita R., Eremets M. A perspective on conventional high-temperature superconductors at high pressure: Methods and materials. Phys. Rep. 2020;856:1–78. doi: 10.1016/j.physrep.2020.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun Y., Wang Y., Zhong X., Xie Y., Liu H. High-temperature superconducting ternary Li-R-H superhydrides at high pressures (R = Sc, Y, La) Phys. Rev. B. 2022;106 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.106.024519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dolui K., Conway L.J., Heil C., Strobel T.A., Prasankumar R.P., Pickard C.J. Feasible route to high-temperature ambient-pressure hydride superconductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024;132 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.132.166001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawamura M. FermiSurfer: Fermi-surface viewer providing multiple representation schemes. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2019;239:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cpc.2019.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

The lead contact will share all data reported in this paper upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report the original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.