Abstract

Background

Tumor mutation burden (TMB) is a predictive biomarker for assessing the response of various tumor types to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI). TMB is quantified based on somatic mutations identified by next-generation sequencing (NGS) using targeted panel data. This study aimed to investigate whether different NGS methods will affect the results of TMB detection in solid tumors.

Materials and methods

In this study, a hybrid capture NGS method was performed to identify Tumor-only (TO) tissue and tumor tissue and white blood cells Tumor Control (TC). The accuracy and specificity of the two employed methods were evaluated by the identification and analysis of standard reference data. Based on the quality control of FFPE samples, 24 pathological and imaging confirmed solid tumor samples were compared to assess the differences between the two methods in identifying and incorporating the mutation sites and the effect on TMB detection.

Result

The data identified 298 common genes in the detection range of TO and TC methods. The detection range of these genes primarily comprised exons and some introns. The coefficient of variation (CV%) between the detected variant and true mutation frequencies was < 10%, confirming their accuracy and specificity. Both methods detected increased mutations of TP53, CDKN2 A, KRAS, PTEN, EGFR, PIK3 CA, BRAF, BRCA2, FGFR2, and NRAS. The consistency rate of TMB was observed as 92% (22/24). The chi-square test indicated a significant difference in TMB results between TO and TC (χ2 = 16.667, p = 0.000, p < 0.001). Furthermore, Cohen’s kappa analysis showed consistency in the TMB values detected by TO and TC methods, which were good and had high repeatability (kappa = 0.833, p = 0.000, p < 0.001). The Venn analysis revealed that the two methods identified and included different TMB sites, which in turn affected the TMB calculation results.

Conclusion

This study revealed that different algorithms and design panels for mutation filtering affect the TMB test results. When the TMB result is near the 10 mut/Mb threshold, different methods may yield different results. Moreover, a single test result can affect clinical treatment decisions. Therefore, it is recommended to use TO or TC combined with other tests for evaluating somatic mutations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-025-13719-7.

Keywords: Solid tumor, Next-generation sequencing, TMB, Somatic mutation

Introduction

Tumor mutation burden (TMB) refers to the total number of mutations per Mb unit (muts/Mb) in the coding region of somatic proteins per million bases (Mb) in the tumor genome. TMB indicates the genomic instability of tumor cells and the number of mutations [1]. Furthermore, tumor cells with high TMB values have higher neoantigens levels, which helps the immune system to recognize and eliminate cancer cells [2, 3]. Therefore, TMB has been employed to predict the efficacy of immunotherapy in solid tumor patients, which can help identify patients who are sensitive to therapeutic drugs such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Based on the KEYNOTE-158 study, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized Pablizumab monotherapy for unresectable or metastatic high TMB (TMB-H ≥ 10 muts/Mb) in adults and children suffering from solid tumors [4].

Whole exome sequencing (WES) is considered a gold standard method for TMB analysis and is widely employed for early immunotherapy in various cancer patients. However, WES has a high cost and requires a large sample size, which limits its wide application in clinical practice [5]. In comparison with WES, a large panel provides a deeper sequencing depth (1000×) within a reasonable cost range, allowing more accurate calculation of molecular indicators such as TMB [6, 7]. Therefore, for clinical TMB detection, it is more practical to use large Panels instead of WES or WGS. NGS can identify somatic mutations (point mutations, insertions or deletions, etc.) by sequencing the patient’s tumor DNA, and can also calculate the TMB value to evaluate the degree of genomic variation in the tumor. The calculation of TMB value and its use as a biomarker remains controversial [8]. Several studies have provided accurate TMB values and therapeutic guidance for clinical application by recalibrating the different clinical results of TMB and ICIs, as well as by employing the TMB heterogeneity adaptive optimization model using clonal genomic features in group structure data to predict immunotherapy response [9–13].

Currently, two main methods are employed for the identification of mutant genes in NGS large Panel products. One of these, Tumor only (TO) method, analyzes the patient’s tumor tissue to identify somatic mutations by comparing the tumor tissue sequencing data with the population database in different regions. The other method, Tumor control (TC), simultaneously detects the patient’s tumor tissue and white blood cells or normal tissue. However, during data analysis, whether these two methods can identify the difference between germline and somatic mutations, which causes the calculation error of TMB, has not been assessed. Therefore, further clinical studies should be conducted to evaluate the impact of methodological differences on TMB detection and provide reference data for the clinical selection of detection methods.

Materials and methods

Reagents

DNA extraction used Kaijie FFPE magnetic bead extraction reagent per the manufacturer’s instructions. All the extracted nucleic acid samples were quantified by Qubit®dsDNA HS Assay Kit. Shihe No.1®Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Tissue TMB Detection Kit (Reversible End-Terminal Sequencing) (Nanjing Shihe Medical Co., Ltd, China) was employed for the TC group for analyzing exons and/or introns of 425 genes, detect tumor formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples and white blood cells. Furthermore, the Illumina TruSight Oncology 500 kit (Illumina, USA) was used for the TO group for exons and/or introns analysis of 523 genes in tumor FFPE samples.

Collection of standard references and samples

The standard references were acquired from Jingliang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. China, and included the hot spot mutation sites of solid tumors. The results were compared with the true values to evaluate the detection accuracy and specificity of the reagent. Furthermore, this study analyzed 24 clinical samples of newly diagnosed patients with solid tumors acquired from the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Guizhou Medical University. All patients were diagnosed by pathology and imaging and met the following inclusion criteria: (1) FFPE samples from patients with pathological test records and (2) FFPE samples from newly diagnosed patients without targeted therapy and immunotherapy. The research samples and methods in this study were approved by the ethics committee of the unit (No: SL-202305167 ). Signed informed consent was obtained from all the patients before the study. The consent allowed the use of test results in scientific research while keeping any personal information private.

FFPE samples and nucleic acid quality control indicators

The optimized proportion of tumor cells in FFPE samples of patients was > 20% by HE staining, and the threshold total amount of nucleic acid DNA extraction was > 300 ng. Furthermore, for the TC method, the white blood cell DNA was extracted from the control patient’s blood samples, and the required total amount was set as > 50 ng. Furthermore, Nanodrop was employed to determine the purity of nucleic acid, the A260/280 value was set at ≥ 1.8.

Library construction

The library was constructed by following the instructions of each reagent of TC and TO groups, which were based on the principle of hybridization capture. The sequencing principle was reversible terminal sequencing (sequencing while synthesizing). Briefly, the DNA was fragmented using Covaris M220 to generate 90–250 bp fragments. Then, end repair and 3’ end A-tail addition were performed. The Index adaptors were connected to identify different samples in the same batch to obtain the pre-library, which was then enriched and amplified using UMI (probe). For library enrichment, during the hybridization capture step, the TC reagent used a probe targeting 425 genes. Whereas the TO reagent required two hybridization/capture steps. First, the specific oligonucleotide pools of 523 genes were ligated into the prepared DNA library, and then the probes hybridized with the target DNA region were captured by streptavidin magnetic beads. The second hybridization was carried out to ensure the high specificity of the capture region. Finally, the enriched library was amplified by PCR, and then quantified and homogenized. The target peak was identified using an Agilent 2100 fragment analyzer. The library was merged, denatured, and diluted to a suitable concentration, and sequenced using the Illumina NextSeq 550.

Bioinformatics analysis and TMB evaluation method

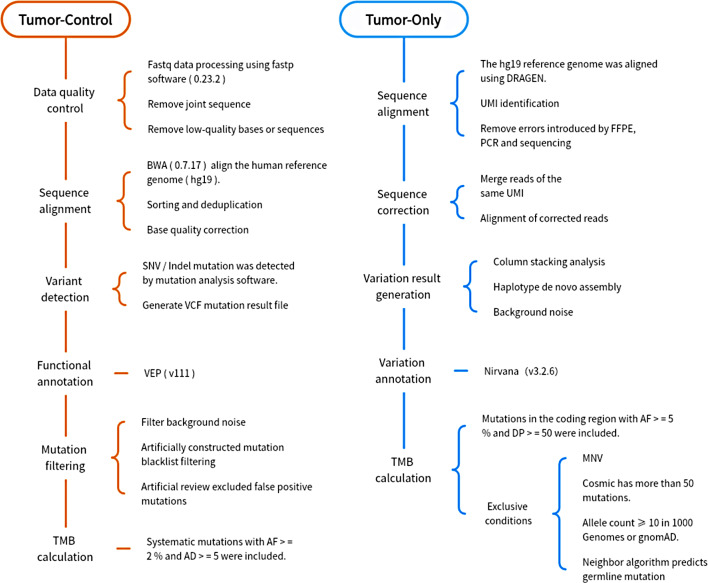

The bioinformatics analysis process of TC and TO is shown in Fig. 1. The TC method assesses the sub-allele frequency of SNP loci and constructs a genome-wide copy number map based on the sequencing depth of tumor tissues and paired normal blood samples. The TO method uses a specific formula to calculate the total number of TMB: TMB variants (including synonymous and non-synonymous non-hot spot somatic coding variants, i.e., single nucleotide variants or small insertions/deletions, with a ≥ 5% variant allele frequency) divided by the size of the coding region defined by the quality control criteria of the reagent. These calculations exclude mutations below the threshold and mutations in mitochondria and non-eligible regions. Mutations with a ≥ 50 population allele count are considered tumor-driven mutations. Furthermore, population frequency databases (such as dbSNP, ExAC, and gnomAD) were employed to filter germline mutations. The TMB state criterion in the two methods was: TMB value > 10/Mb = high TMB (TMB-H), TMB value < 10/Mb = low TMB (TMB-L).

Fig. 1.

The bioinformatics analysis process of TC and TO

Result

Accuracy and specificity

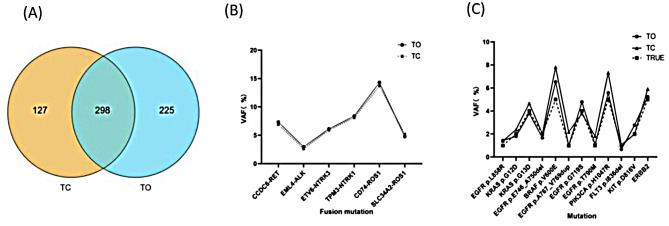

Some fusion mutation parameters for both methods are indicated in Table 1. In terms of coverage, the detection range of TO and TC overlapped 298 genes (Fig. 2A). Both methods identified all exon and partial intron regions of some genes. Furthermore, both methods accurately detected the fusion sites based on the fusion standard reference and the hot spot mutation sites of common solid tumors. Furthermore, the coefficient of variation (CV%) between the mutation frequency was also detected and the true value was < 10%. Moreover, the data confirmed that TC and TO both have high accuracy and specificity, and the test results in this laboratory are reliable (Fig. 2B and C).

Table 1.

Comparison of method reagent parameters

| Approach | TC (425 Panel /Tumor-control) |

TO TSO 500(Tumor-only) |

|---|---|---|

| DNA input (ng) | ≥ 50 | ≥ 40 |

| Fragmentation method |

Sonication sonication |

|

| Detection range | Whole exons and selected Introns | |

| Genes/exons | 425/5035 | 523/7567 |

| Probe length (bp) | 120 | 80 |

| Probe design | hyb-capture | hyb-capture |

| Probe number | 12,178 | 39,759 |

| TMB value (mut/Mbp) | Synonymous and Non-synonymous | |

| Database | COSMIC, dbSNP, gnomAD, ClinVar, and OMIM, dbSNP, ExAC, gnomAD | |

Fig. 2.

Detection range and standard reference analysis. (A) The intersection of the TC and TO detection range indicates full exon and partial intron regions of 298 genes. (B) Two methods were used to detect the reference sites of the fusion mutation standard. (C) Evaluate the hot spot mutations of solid tumors in the standard

General results of clinical samples

This study collected FFPE samples from 24 patients with solid tumors. The samples covered various types of cancers, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (n = 14), bladder cancer (n = 1), gallbladder cancer (n = 1), liver cancer (n = 1), epididymal synovial sarcoma (n = 1), melanoma (n = 1), renal cell carcinoma (n = 1), head and neck cancer (n = 2) and breast cancer (BC) (n = 2). There were 15 male and 9 female patients aged between 36 and 84 years, with an average age of 62 years (Fig. 3A and B).

Fig. 3.

Clinical sample composition. (A) Types of cancers in 24 clinical samples, the value indicates the number of cancer species. (B) The proportion of males and females in clinical samples is expressed in percentage

Quality control of clinical sample sequencing data

The results showed that the total amount of pre-library (ng) and the median sequencing depth (X) in the exon sequencing region were significantly higher in the TC group than in the TO group. Furthermore, the quality control indexes were > 200 ng and > 200 X, respectively. All sample libraries and sequencing depths were qualified. Moreover, compared with TO, the TC library had a higher total amount and sequencing depth (Fig. 4A and B). Furthermore, the remaining quality control parameters of the two methods, such as machine data comparison rate (ON TARGET %), exon coverage rate (50X COVERAGE %), and error rate (Q30%), were also qualified (Fig. 4C). Therefore, the qualification rate results in this study reached 100%.

Fig. 4.

Quality control of clinical sample sequencing. (A) The total amount of pre-library (ng) constructed by TO and TC methods. (B) Median sequencing depth of exon sequencing regions (X) by TO and TC methods. (C) TO and TC offline data comparison rate (ON TARGET %), exon coverage rate (50X COVERAGE %), and error rate (Q30%)

Clinical sample test results

The mutations detected by TC were classified into Level 1 (n = 8), 2 (n = 34), 3 (n = 58), and 4 (n = 322), whereas the mutations detected by TO were categorized as Strong Significance (n = 39), Confirmed Somatic (n = 38), Potential Significance (n = 34), VUS (n = 288) (Fig. 5A and B). Based on the 298 genes in the common detection range region, among the class I and II mutations, TP53, CDKN2A, KRAS, PTEN, EGFR, PIK3CA, BRAF, BRCA2, FGFR2, and NRAS had a higher number of point mutations, insertions or deletions (SNV/Indel) (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, the CNV detected by the two methods included AKT2, MYC, MYC, CCNE1, FGFR1, KRAS, PTEN, EGFR, CCND1, and FGF19 (Fig. 5D). Overall, it was indicated that in the same detection range and site, different methods of mutation site analysis demonstrated different detection sites and their number of detected sites.

Fig. 5.

Detection results of the two methods. (A) The mutations detected by TC were classified as Level 1 (n = 8), 2 (n = 34), 3 (n = 58), and 4 (n = 322). (B) TO detected mutations were categorized as Strong Significance (n = 39), Confirmed Somatic (n = 38), Potential Significance (n = 34), and VUS (n = 288). (C) In types I and II mutations, point mutations were detected by both TO and TC. TP53, CDKN2 A, KRAS, PTEN, EGFR, PIK3CA, BRAF, BRCA2, FGFR2, and NRAS were found to have a higher number of insertion or deletion (SNV/Indel) mutations. (D) The CNV loci detected by TO and TC were AKT2, MYC, MYC, CCNE1, FGFR1, KRAS, PTEN, EGFR, CCND1, and FGF19

TMB results

The TMB results indicated 92% consistency (22/24). Among these consistent samples, 11 were TMB-H, including 8 cases of NSCLC, 1 case of bladder cancer, 1 case of head and neck cancer, and 1 case of kidney cancer. The chi-square test was performed to evaluate the results of the TMB test, which revealed a significant difference between the TO and the TC groups (χ2 = 16.667, p = 0.000,p < 0.001). However, the paired sample T-test showed no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.132,p > 0.05). The results of Cohen’s Kappa statistics showed that the two methods had highly consistent and reproducible results (Kappa = 0.833, p = 0.000, p < 0.001) (Table 2). The results of TO and TC were normally distributed (Fig. 6A, B and C). Moreover, compared with TO, TC detection indicated a higher TMB value (15/24) (Fig. 6D, E and F).

Table 2.

TMB assessment analysis

| Group | Chi-square test | Pairing T-test | Cohen’s Kappa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | p | t | p | Kappa | p | |

| TC | 16.667 | 0.000** | 1.561 | 0.132 | 0.833 | 0.000** |

| TO | ||||||

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Fig. 6.

The results of TMB were detected by the two methods. (A) The normal distribution map of the TMB value. (B) TMB value LOG to calculate the normal distribution diagram. (C) Normal skewness distribution map of TMB value. TO = 0.487, is right skew, kurtosis is TC = -0.793, TO = -0.941, kurtosis is relatively flat. (D) TMB value distribution box plot. (E) TMB distribution trend line chart. The TMB values of the two methods were measured with 10 as the cut-off point. Samples with values below 10 were evaluated as low tumor mutation load (TMB-L), and samples with cut-off values above 10 were evaluated as high tumor mutation load (TMB-H). The red circle indicates that the TMB results of the two samples are opposite, and the green box indicates that the samples have a large difference in TMB value. (F) The number of cases with TMB value TC ≥ TO was 16 cases. The TMB value of TC was significantly higher than that of TO; therefore, the mutation screening differences between TO and TC methods include different final numbers of system mutations in the calculation, which may be the main reason for the difference in TMB values

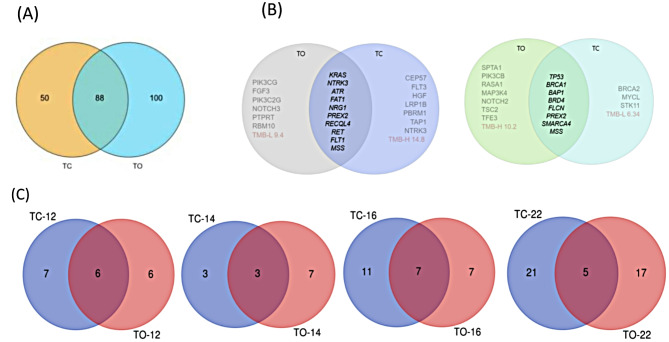

Furthermore, the number of TMB sites assessed by TC was less than that detected by TO (138 < 188). A total of 88 common sites were selected for TMB calculation by the two methods (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Difference analysis of detection results and TMB. (A) For TMB analysis by the two methods, 24 samples and 88 intersection sites were selected. (B)The left side of the figure represents NSCLC patients, and the right side represents BC patients. The intersection shows the results of co-detected mutations and microsatellite instability (MSI) assessment. The details of the specific mutation sites are shown in the appendix. (C) TC-12/TO-12 means NSCLC patients included in the TMB locus, TC-14/TO-14 means BC patients included in the TMB locus, TC-16/TO-16 means 16 bladder cancer patients included in the TMB locus, TC-22/TO-22 means 22 head and neck cancer patients included in the TMB locus. The intersection number in the graph indicates that the number of genes included in the TMB calculation is consistent. It was observed that different methods have different criteria for mutation filtering and system interpretation. Different sites included in TMB calculation yield different TMB values, which affects the judgment of TMB-H or TMB-L to some extent

Analysis of different results

In samples number 12 and 14, the TMB analysis by TC and TO indicated opposite results. The TC method revealed that the TMB value of NSCLC patients numbered 12 was 14.8, which was considered TMB-H, whereas the TMB value detected by TO was 9.4, which was deemed TMB-L. Furthermore, the TMB value of BC patients numbered 14 was 6.34 (TMB-L) in TC detection and 10.2 (TMB-H) in TO detection (Fig. 6E). The intersection represents the mutation results of samples No. 12 and 14 (Fig. 7B). The genes with mutation levels 1 and 2 were the same; however, the mutation sites of levels 3 and 4 were different (Supplementary Data). Moreover, in addition to the different detection ranges, there are also differences in the mutation levels. Although bladder cancer patient No. 16 and head and neck cancer patient No. 22 were both TMB-H, the TMB values obtained by different detection methods were quite different. In addition, samples No. 12, 14, 16, and 22 were analyzed by TC and TO methods to detect their loci and TMB calculation (Fig. 7C). It was found that the two methods had significantly different TMB results in different cancer types, and the Venn analysis is shown in Fig. 7. The TMB results were different due to the different mutation sites identified and included in the calculation by the two methods.

Discussion

For detecting TMB by NGS large panel, there are many influencing factors, such as biological characteristics (including tumor type, etc.), pre-analysis factors (sample quality/quantity, etc.), sequencing factors (DNA capture area, panel size, enrichment method, sequencing depth, sequencing platform), bioinformatic analysis (mutation type, germline filtration, cut-off value, etc.) and threshold setting (patient population), etc. The contradictory TMB results might primarily be because of the incomplete biostatistical rules and the diversity of clinical samples [13]. Furthermore, the simultaneous detection of normal tissues and cells as controls for screening somatic mutations may also cause inconsistent results. The TMB calculation is mainly based on the number of somatic mutations involved [14, 15]. The TC process judges the system and germline variation according to the AF difference between the tumor and control samples. The TO process uses a set of germline prediction algorithms (toseq) developed by machine learning. The algorithm gives different weights to conditions such as mutation type, mutation abundance, and population database distribution, and reveals whether a mutation is germline mutation through the prediction model. Furthermore, the germline mutations are not included in the TMB calculation. Therefore, adding a control may impact the results of TMB [13, 16–18].

Here, the standard analysis results showed no difference in TMB detection results of TO and TC methods. However, when clinical samples were analyzed, opposite results were observed. To ensure the comparability of data, the nucleic acid extraction, library construction, sequencing, background noise filtering, and TMB calculation were kept constant between TO and TC methods. The results showed that the TMB value of TC was significantly higher than the TO. Therefore, the different mutation screening methods (TO and TC) include different final numbers of system mutations in the calculation, which may be the main reason for the difference in TMB values.

The paired two-sample test of clinical samples showed that the TMB of 2 samples (No. 12 and 14 ) had the opposite results. The TMB result of the No. 12 sample TC was higher than that of TO (TC = 14.8 > TO = 9.4), while that of sample No. 14 was lower than that of TO (TC = 6.34 < TO = 10.2). Furthermore, it was found the TO test results of samples No. 12 and 14 were near the critical value. The comparison with the sequencing results of the normal control revealed differences in the number of screened mutant genes, which is the main reason for the opposite results. This may be related to the characteristics of the tumor. The clinicopathological diagnosis results revealed that sample 12 was NSCLC with somatic mutation, which is greatly affected by environmental factors and has great individual differences. Therefore, more system mutations can be screened and higher TMB values can be calculated by comparing normal controls. This study included 14 NSCLC samples, and most of the samples obtained higher TMB values by TC detection. However, higher TMB results are due to higher or lower detection sensitivity, and further observation and research are needed. The clinicopathological diagnosis of sample 14 was BC, which is a hereditary tumor and affected by familiality. The effect of germline mutations will be excluded by white blood cell control. The TMB calculation includes fewer mutation sites, which yields a lower TMB value. Therefore, when the TMB results are near the threshold, different methods will affect the detection results, which in turn affects clinical decision-making. Thus, combining other detection methods can improve the sensitivity of the detection. For example, in NSCLC, the immunohistochemical detection of PD-L1 and TMB should complement each other [19–22]. For BC treatment, the interaction between the TCR index and TMB may guide the neoadjuvant therapy of operable BC [23–25]. Further, due to the increased incidence of intratumoral heterogeneity (ITH), treatment decisions cannot be made based on a single clinical predictor. Therefore, it is necessary to combine other indicators, including but not limited to TMB, HLA genotype, PD-L1 level, serum albumin, and certain DNA damage repair defects.

This study also found that two samples (sample 16 (TC = 22.21, TO = 11.0) and sample 22 (TC = 28.55, TO = 19.6)) were TMB-H; however, their TMB values were quite different. Sample 16 were bladder cancer and sample 22 are head and neck cancer cases, both of which indicated TC > TO. It was thus inferred that the reason for inconsistent results is that bladder cancer and head and neck tumors are rare tumors [26–29]. Due to incomplete understanding of the gene mutation profiles of these tumors and limited number of loci included in the database, the TO method may result in lower tumor mutation burden (TMB) values.

Limitations

There are certain limitations of this study. (1) The sample size of the study was small. (2) The statistical results only preliminarily explained the difference affecting the TMB values between the TC and TO methods. Therefore, in the future, more clinical samples should be included to provide novel selection criteria for TMB analysis.

Conclusion

This study revealed that different algorithms and design panels for mutation filtering will affect the TMB test results. When the TMB result is near the 10 mut/Mb threshold, different methods may yield different results. Furthermore, a single test result will affect clinical treatment decisions. Therefore, for employing TO or TC, it is recommended to combine other tests for evaluating sumatic mutations. Moreover, the TC method is recommended for hereditary tumors, head and neck tumors, bladder cancer, kidney cancer, and other rare tumors. Similarly, future TMB detection methods should combine clinical and biological specificity of different cancer species, integrate multi-omics methods, or improve mutation filtering algorithms to improve the accuracy of TMB.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Mi Liu conceived this study. Xueshu Chen and Haixing Chen collected all clinical data of patients. Xueshu Chen and Haixing Chen performed the data analysis. Xueshu Chen and Mi Liu wrote the manuscript. Mi Li, Fujuan Zhang, Weiwei Ouyang, Xiaoxu Li, Yong Yang and Niya Long supported the study. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out with the support of Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Plan Project (Number: ZK[2023] General 322)) and Guizhou Provincial Health Commission Science and Technology Fund Project (Number: gzwkj 2024-227; gzwkj 2025-113).

Data availability

Data is contained within the article and its supplementary materials.

Declarations

Ethical approval

The study received local ethics committee approval from the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Guizhou Medical University Clinical Research Ethics Committee, with a decision dated 16.05.2023 and numbered SL-202305167. The study was conducted using the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the retrospective study design, the need for informed consent was waived by the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Guizhou Medical University Clinical Research Ethics Committee.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xueshu Chen and Haixing Chen contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Sha D, Jin Z, Budczies J, Kluck K, et al. Tumor Mutational Burden as a predictive biomarker in solid tumors. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(12):1808–25. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0522. Epub 2020 Nov 2. PMID: 33139244; PMCID: PMC7710563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan TA, Yarchoan M, Jaffee E, et al. Development of tumor mutation burden as an immunotherapy biomarker: utility for the oncology clinic. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(1):44–56. 10.1093/annonc/mdy495. PMID: 30395155; PMCID: PMC6336005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcus L, Fashoyin-Aje LA, Donoghue M, et al. FDA approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the treatment of Tumor Mutational Burden-High Solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(17):4685–9. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0327. Epub 2021 Jun 3. PMID: 34083238; PMCID: PMC8416776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marabelle A, Le DT, Ascierto PA, et al. Efficacy of Pembrolizumab in patients with Noncolorectal high microsatellite Instability/Mismatch repair-deficient Cancer: results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(1):1–10. 10.1200/JCO.19.02105. Epub 2019 Nov 4. PMID: 31682550; PMCID: PMC8184060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim R, Kim S, Oh BB, et al. Clinical application of whole-genome sequencing of solid tumors for precision oncology. Exp Mol Med. 2024;56(8):1856–68. 10.1038/s12276-024-01288-x. Epub 2024 Aug 13. PMID: 39138315; PMCID: PMC11371929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchhalter I, Rempel E, Endris V et al. Size matters: dissecting key parameters for panel-based tumor mutational burden analysis. Int J Cancer, 2019,144(4):848–858. 10.1002/ijc.31878. Epub 2018 Dec 4. PMID: 30238975. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D, et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med. 2017;9(1):34. 10.1186/s13073-017-0424-2. PMID: 28420421; PMCID: PMC5395719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Addeo A, Friedlaender A, Banna GL, et al. TMB or not TMB as a biomarker: that is the question. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;163:103374. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103374. Epub 2021 Jun 2. PMID: 34087341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sung MT, Wang YH, Li CF. Open the Technical Black Box of Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB): factors affecting harmonization and standardization of panel-based TMB. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):5097. 10.3390/ijms23095097. PMID: 35563486; PMCID: PMC9103036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nassar AH, Adib E, Abou Alaiwi S, et al. Ancestry-driven recalibration of tumor mutational burden and disparate clinical outcomes in response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(10):1161–72..e5. Epub 2022 Sep 29. PMID: 36179682; PMCID: PMC955977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Guan Y, Lai X, et al. THOR: a TMB heterogeneity-adaptive optimization model predicts immunotherapy response using clonal genomic features in group-structured data. Brief Bioinform. 2024;26(1):bbae648. 10.1093/bib/bbae648. PMID: 39679440; PMCID: PMC11647273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Lai X, Wang J, et al. TMBcat: a multi-endpoint p-value criterion on different discrepancy metrics for superiorly inferring tumor mutation burden thresholds. Front Immunol. 2022;13:995180doi. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.995180. PMID: 36189291; PMCID: PMC9523486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Wang S, Wang Y, et al. What makes TMB an ambivalent biomarker for immunotherapy? A subtle mismatch between the sample-based design of variant callers and real clinical cohort. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1151224. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1151224. PMID: 37304296; PMCID: PMC10248171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dupain C, Gutman T, Girard E, et al. Tumor mutational burden assessment and standardized bioinformatics approach using custom NGS panels in clinical routine. BMC Biol. 2024;22(1):43doi. 10.1186/s12915-024-01839-8. PMID: 38378561; PMCID: PMC10880437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang H, Bertl J, Zhu X, et al. Tumour mutational burden is overestimated by target cancer gene panels. J Natl Cancer Cent. 2022;3(1):56–64. 10.1016/j.jncc.2022.10.004. PMID: 39036316; PMCID: PMC11256552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makrooni MA, O’Sullivan B, Seoighe C. Bias and inconsistency in the estimation of tumour mutation burden. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):840. 10.1186/s12885-022-09897-3. PMID: 35918650; PMCID: PMC9347149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Wang J, Fang W, et al. TMBserval: a statistical explainable learning model reveals weighted tumor mutation burden better categorizing therapeutic benefits. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1151755. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1151755. PMID: 37234148; PMCID: PMC10208409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Lai X, Wang J, et al. A joint model considering measurement errors for optimally identifying tumor mutation burden threshold. Front Genet. 2022;13:915839. 10.3389/fgene.2022.915839. PMID: 35991549; PMCID: PMC9386083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rizvi H, Sanchez-Vega F, La K et al. Molecular Determinants of Response to Anti-Programmed Cell Death (PD)-1 and Anti-Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) Blockade in Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Profiled With Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(7):633–641. 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.3384. Epub 2018 Jan 16. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(16):1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Lung Cancer with a High Tumor Mutational Burden. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2093–2104. 10.1056/NEJMoa1801946. Epub 2018 Apr 16. PMID: 29658845; PMCID: PMC7193684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Goodman AM, Kato S, Bazhenova L, et al. Tumor Mutational Burden as an independent predictor of response to Immunotherapy in Diverse Cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16(11):2598–608. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0386. Epub 2017 Aug 23. PMID: 28835386; PMCID: PMC5670009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galvano A, Gristina V, Malapelle U, et al. The prognostic impact of tumor mutational burden (TMB) in the first-line management of advanced non-oncogene addicted non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. ESMO Open. 2021;6(3):100124. 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100124. Epub 2021 Apr 30. PMID: 33940346; PMCID: PMC8111593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang H, Huang J, Ao X, et al. TMB and TCR are correlated indicators predictive of the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:740427. 10.3389/fonc.2021.740427. PMID: 34950580; PMCID: PMC8688823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barroso-Sousa R, Pacífico JP, Sammons S, et al. Tumor mutational burden in breast Cancer: current evidence, challenges, and opportunities. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(15):3997. 10.3390/cancers15153997. PMID: 37568813; PMCID: PMC10417019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu K, Mao X, Li T, et al. Immunotherapy and immunobiomarker in breast cancer: current practice and future perspectives. Am J Cancer Res. 2022;12(8):3532–47. PMID: 36119833; PMCID: PMC9442024. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfister DG, Haddad RI, Worden FP, et al. Biomarkers predictive of response to pembrolizumab in head and neck cancer. Cancer Med. 2023;12(6):6603–14. 10.1002/cam4.5434. Epub 2022 Dec 7. PMID: 36479637; PMCID: PMC10067081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wood MA, Weeder BR, David JK, et al. Burden of tumor mutations, neoepitopes, and other variants are weak predictors of cancer immunotherapy response and overall survival. Genome Med. 2020;12(1):33. 10.1186/s13073-020-00729-2. PMID: 32228719; PMCID: PMC7106909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su X, Jin K, Guo Q, et al. Integrative score based on CDK6, PD-L1 and TMB predicts response to platinum-based chemotherapy and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Br J Cancer. 2024;130(5):852–60. 10.1038/s41416-023-02572-9. Epub 2024 Jan 11. PMID: 38212482; PMCID: PMC10912081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiravand Y, Khodadadi F, Kashani SMA, Hosseini-Fard SR, Hosseini S, Sadeghirad H, Ladwa R, O’Byrne K, Kulasinghe A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(5):3044–60. 10.3390/curroncol29050247. PMID: 35621637; PMCID: PMC9139602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and its supplementary materials.