Abstract

Loss-of-function mutations in HOXC13 have been associated with Ectodermal Dysplasia-9, Hair/Nail Type (ECTD9) in consanguineous families, characterized by sparse to complete absence of hair and nail dystrophy. Here we characterize the spontaneous mouse mutation Naked (N) as a terminal truncation in the Hoxc13 (homeobox C13) gene. Similar to previous reports for homozygous Hoxc13 KO mice, homozygous N/N mice exhibit generalized alopecia with abnormal nails and a short lifespan. However, in contrast to Hoxc13 heterozygous KO mice, N/+ mice show generalized or partial alopecia, associated with loss of hair fibers, along with normal lifespan and fertility. Our data point to a lack of nonsense-mediated Hoxc13 transcript decay and the presence of the truncated mutant protein in N/N and N/+ hair follicles, thus suggesting a dominant-negative mutation. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a semi-dominant and potentially dominant-negative mutation affecting Hoxc13/HOXC13. Furthermore, recreating the N mutant allele in mice using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing resulted in the same spectrum of deficiencies as those associated with the spontaneous Naked mutation, thus confirming that N is indeed a Hoxc13 mutant allele. Considering the low viability of the Hoxc13 KO mice, the Naked mutation provides an attractive new model for studying ECTD9 disease mechanisms.

Keywords: Animal Model, Hair Follicle, Mice

1. INTRODUCTION

The HOX transcription factors are crucial regulators of epidermal and hair follicle (HF) differentiation1. In particular, certain Hoxc genes establish topographical specificity in skin and its appendages, and are involved in HF regeneration2 3 4 5 6. Hoxc13 is an essential regulator of the hair cycle and is expressed primarily in the upper bulb region of the HF for all hair types in both mouse7,8 and human (HOXC13)9 skin. Hoxc13 expression is initiated during HF morphogenesis and continues during the anagen stage of the hair growth cycle. It is also expressed in the most proximal region of the HF during catagen10 11. In the anagen HF, Hoxc13 expression encompasses distinct subpopulations of cells, primarily in the matrix and the three cylindrical layers of the differentiating hair shaft (HS), including the cuticle, cortex, and medulla9 12 13. Functional studies revealed that both Hoxc13-null7 14 and Hoxc13-overexpressing transgenic15,16 mice exhibit severe hair growth defects resulting in structurally defective HS. Homozygous Hoxc13 KO mice fail to grow any external hair during their short life span7 17 and exhibit defective nail development. Remarkably, the hair and nail phenotypes of the Hoxc13 KO mice closely mimic those of nude (Foxn1nu/Foxn1nu) mutants18 19. In the Hoxc13-overexpressing mice, the phenotype manifests itself in the delayed formation of a thin and scruffy-looking hair coat during postnatal development and progressive alopecia during adulthood15.

In humans, loss-of-function (LOF) mutations affecting HOXC13 have been associated with a type of autosomal recessive Pure Hair and Nail Ectodermal Dysplasia (PHNED) known as Ectodermal Dysplasia-9, Hair/Nail Type (ECTD9, OMIM #614931)20 21 22 23. This condition has been described in consanguineous families of Chinese, Afghan, Syrian, Pakistani and Hispanic ethnicities and is characterized by sparse to complete absence of hair and nail dystrophy without non-ectodermal or other ectodermal manifestations. Nail dystrophy affects all 20 digits with short fragile nails or spoon nails20 21. Lower expression of FOXN1, KRT35, and KRT85 downstream target genes have been detected in HFs from patients20. HOXC13 has also been associated with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma24 and lung adenocarcinoma25 proliferation.

In this report we show that the naturally occurring Naked mutation (symbol: N), discovered almost a century ago26, is a semi-dominant nonsense allele of Hoxc13 (Hoxc13N). The low viability of the homozygous Hoxc13 KO mice makes the alopecic, but viable, heterozygous N/+ mice an attractive option to study the ECTD9 genetic disorder.

2. METHODS

2.1. Fine genetic mapping of the Naked (N) mutation

The Naked (N) spontaneous mutation was reported in 1927 in a stock of unidentified albino mice at Latvia University26 and mapped to distal chromosome 15 (linkage group VI at the time)27. In our laboratory, congenic C57BL/6-N/+ mice (from The Jackson Laboratory) were outcrossed with wild-type FVB/NHsd (Envigo) mice to generate (C57BL/6 x FVB/N)F1-N/+ mice (~50%). These F1 hybrids were intercrossed to obtain the F2 mice used for refining the location. The refined position on distal chromosome 15 was mapped using 96 F2 mice (both N/+ and N/N), genotyped with genome-wide as well as regional microsatellite and SNP markers (polymorphic between FVB/N and C57BL/6) by Laboratory Animal Genetic Services (LAGS) at MD Anderson (Smithville, TX). The refined candidate region was approximately 1 Mb in size (Chr 15, 102.5 to 103.5 Mb) and contained ~30 protein coding genes, including the Hoxc gene cluster. The N mutant allele was later introgressed onto the FVB/N background by marker-assisted backcrossing at LAGS. This full congenic line (FVB.Cg-Hoxc13N) is now at generation N14 and was used for some of the histopathology studies.

2.2. Whole exome sequencing

Two genomic DNA samples from N/N mice were processed for library construction using the SPRIworks Fragment Library Kit I (Beckman Coulter). Libraries were pooled together and processed for exome capture using the NimbleGen SeqCap EZ Developer Library (110624_MM9_exome_L2R_ D02_EZ_HX1, Roche). Sequencing was performed using an Illumina HiSeq2000 platform at the Science Park Next Generation Sequencing Facility. Image analysis, base-calling, and error calibration were performed using Illumina’s Genome analysis pipeline. Sequencing was performed reaching an average depth of 40 × per sample.

2.3. Generation of genome edited mice carrying the Naked mutation

Optimal RNA guides (crRNA), which paired close to the expected mutation, were chosen using the Breaking-Cas bioinformatic application28. Next, a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) oligonucleotide (90 nucleotides in length), with the desired mutation centrally located, was designed (Supplemental Fig. 5). For the microinjection of CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes into fertilized mouse oocytes, we followed reported procedures29 30. In brief, 50 ng/μl of Cas9 protein (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc) and 25 ng/μl of sgRNA (crRNA-tracrRNA, Dharmacon) were prepared in sterile embryo-transfer water. The mixture was incubated on ice for 10 min. Next, ssDNA donor 100 ng/μl was added and the final volume adjusted to 50 μl using microinjection buffer (1 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5; 0.1 mM EDTA pH 7.5), centrifuged for 30 min at 14,000 × g at 4C, and kept on ice until use. RNP molecules were microinjected into the cytoplasm of B6CBAF2 (Envigo; from intercrossing B6CBAF1/OlaHsd) fertilized oocytes using standard procedures31.

2.4. In situ hybridization analysis of Hoxc13 and Foxn1 expression

For in situ hybridization (ISH), the RNAscope® 2.5 HD Duplex Assay (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Neward, CA) was used to detect Hoxc13 and Foxn1 mRNA expression in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections from dorsal skin. This assay is based on signal amplification and background suppression technology and uses a novel and proprietary method of ISH to visualize single RNA molecules per cell in FFPE samples mounted on slides. RNAscope® specific probes in two independent channels were used with HRP-based Green and AP-based Fast Red chromogens, resulting in detectable green (Foxn1) and red (Hoxc13) signals, respectively. The RNAscope® 2.5 HD Duplex Assay allowed us to study the co-regulation of these genes within the keratinocyte context, based on the reliable chromogenic detection of the two transcripts. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test.

2.5. Tissue collection, immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy

Untreated dorsal skin at different postnatal (P) time points (P2, P5, P14, P15, P17, P21, P28, P32, P40, P49, P60, and P180), depending on the genotype, were fixed in formalin overnight, transferred to 70% ethanol, then embedded in paraffin prior to sectioning and staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). TPA-treated dorsal skin from 6–8 wk old N/+ and WT mice were also collected and fixed for keratinocyte transit studies. The histological analysis was done in littermates with C57BL/6J or FVB/N backgrounds (>N10), as well as (C57BL/6 x FVB/N) F1 and F2 hybrids. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis was performed with polyclonal antibodies directed against mouse keratins K1 and involucrin (Covance Research Products, Richmond, CA); KRT35 (LifeSpan Biosciences, Inc., Seattle, WA, USA); Desmoglein 4 (Biorbyt Limited, Cambridge, UK); HOXC13 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA); Ki67 (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX) and cleaved-Caspase 3 (Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA) as previously described32. All slides were evaluated by an American College of Veterinary Pathologists (ACVP) boarded veterinary pathologist under a light microscope, and findings were recorded in a tabular form.

For immunofluorescence (IF) staining and confocal imaging, PFA fixed cryo-preserved or paraffin embedded skin sections were subject to permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100, washed with PBS and blocked with Background Sniper (Biocare Medical) for 20 min. Immunofluorescence staining was performed with rabbit anti-HOXC13 (Abcam, ab188043) or rabbit anti-KRT35 antibody (LS Bio, LSC322555) in DaVinci green antibody diluent (Biocare Medical) and incubated for 2 hrs at RT, washed with PBS/Tween 20 and stained with anti-rabbit-AlexaFluor568 secondary antibody (ThermoFisher) for 1 hr at RT. Stained tissues were washed in PBS/Tween 20 wash buffer, counterstained with DAPI (4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride) and mounted in ProLong Gold Antifade (ThermoFisher). Immunofluorescent imaging was performed on a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope using a pinhole of 1 A.U. and a 40× (N.A. 1.4) Plan-Apo objective lens.

Electron microscopy of HS was performed on a JSM 5900 scanning electron microscope (SEM) at the High-Resolution Electron Microscopy Facility (HREMF) at MD Anderson in Houston.

2.6. Analysis of keratinocyte proliferation and transit following TPA treatment

To evaluate keratinocyte proliferation, the shaved dorsal skin of 4 N/+ and 4 WT mice (full congenic FVB/N background) at 6–8 wks of age was treated with twice-weekly topical applications of TPA (SIGMA) (4 μg/200 μl acetone) for two weeks. For the proliferation analysis, treated mice received intraperitoneal injections of 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma–Aldrich) at 100 μg/g body weight in PBS 24 hrs after last treatment and 30 min prior to euthanasia and tissue collection. For in vivo keratinocyte transit studies, mice were injected with BrdU 17 hrs after the last of four TPA applications (over a two-week period) and sacrificed at either 1 hr or 8 hrs after BrdU, as described33. BrdU incorporation was analyzed by standard 3-step immunoperoxidase detection using a mouse anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody (Becton-Dickinson Immunocytometry System, Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA), biotin F(ab’)2 rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, NY), and Streptavidin Peroxidase (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA). Diaminobenzidine (BioGenex) was the chromagen used for visualization. Epidermal cell proliferation (labeling index) was determined by calculating the percentage of epidermal basal cells positive for BrdU. A minimum of 20,000 basal cells was counted using digital images of IHC slides (dorsal skin) captured with the Aperio ScanScope CS slide scanner (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA). A fully automated nuclear algorithm provided with the instrument was adapted to count BrdU-positive cells in the epidermis of both WT and mutant mice.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Gross appearance of N/N and N/+ mice

The phenotype of the Naked mutation was first described by John Sundberg in 199434. In our study, we confirmed that homozygous Hoxc13N/Hoxc13N (N/N) mice die within a few days of birth (P1-P14 range), that time to death varied among genetic backgrounds (e.g., homozygous N/N mice died younger on the FVB/N background), and that runting is evident starting at P3-P4 (Fig. 1A). Between P1 and P2, the gross appearance of the three genotypes (N/N, N/+, and +/+) is alike, which makes genotyping essential to differentiate them at this stage (not shown). Starting at P6-P7 and beyond, N/N mice exhibited generalized hypotrichosis (all hair types missing) (Fig. 1B). This phenotype is similar to the one exhibited by homozygous Hoxc13 KO mice7 14. In contrast, N/+ heterozygous mice showed a normal lifespan and were fertile. They had a normal appearance until one week of age, when the first hair coat appeared; however, from this time point on, N/+ mice exhibited generalized or partial (head and anterior trunk region) alopecia, with some variability depending on age and genetic background (Fig. 1B, C, D). For example, a period of generalized alopecia is observed in N/+ mice around P28-P32, especially in the FVB/N background (Fig. 1C). Abnormalities in pelage HS in N/+ mice were also observed (Supplemental Fig. 1), as previously described35. Notably, this phenotype of N/+ mice was in stark contrast to the near absence of skin phenotype reported for Hoxc13 heterozygous (+/−) KO mice, in which only some KO-GFP reporter mice displayed small patches of sparse facial fur36. Contrary to N/N mice, N/+ heterozygotes have normal vibrissae and nails, and normal hair in the foot, tail and genital area, in agreement with previous reports34.

Fig. 1. Skin phenotype in Hoxc13N/Hoxc13N (N/N) and Hoxc13N/Hoxc13+ (N/+) mutant mice.

(a) Full congenic FVB/N.Cg-Hoxc13N mice (three genotypes) can be seen at P5. At this stage, WT (+/+) and N/+ mice are very difficult to differentiate by phenotype. Homozygous N/N mice in the FVB/N background never survived beyond P6 (even under specific pathogen free conditions). (b) The images display (FVB/N x C57BL/6J)F2 mice at P14 showing a WT mouse (top), the partial alopecia typical of some N/+ mice (middle) and the complete alopecia associated with growth retardation in N/N mice (bottom). As a semi-dominant mutation, each genotype exhibits a distinct phenotype. In this hybrid background, the maximum survival time was P14. (c) An FVB/N-N/+ mouse (top) with characteristic generalized alopecia is shown at P30. (d) In some older N/+ mice, depending on the genetic background, a characteristic anterior alopecia persists for life (shown here at P60 in an FVB/N congenic mouse).

3.2. Identification of a premature stop codon in the Hoxc13 gene

After ruling out several candidate genes in the region of interest on chromosome 15 using PCR followed by Sanger sequencing, we decided to perform whole exome sequencing (WES). Using bioinformatics, we analyzed the WES data and found a C to A transversion resulting in a premature stop (TCG, serine -> TAG, stop) in the Hoxc13 gene in the N/N DNA but not in the WT samples. We confirmed the presence of this mutation by standard PCR followed by sequencing using N/N and N/+ DNA templates and also confirmed that this transversion was not present in the DNA of the several (unrelated) classical inbred strains we tested. This nonsense mutation (S298X) is located in exon 2 of Hoxc13 (Fig. 2), resulting in a predicted loss of 20 amino acids from the C-terminal DNA binding domain (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 2. The Naked mutation corresponds to a premature stop codon in the Hoxc13 gene.

After performing whole exome sequencing on mutant DNA (N/N and N/+), a C to A transversion (TCG/Serine replaced by TAG/Stop) was found in the Hoxc13 gene (confirmed by Sanger sequencing). This nonsense mutation (S298X) creates a premature stop codon in exon 2 of Hoxc13 that is expected to create a truncated protein missing the last 31 amino acids of the protein (including 20 amino acids of its C-terminal DNA binding domain).

Fig. 5. Position of HOXC13 S298X nonsense mutation in the homeodomain (HD) and in relation to the conserved MEIS interacting domains.

Top: alignment of human and mouse HOXC13 protein sequences; exon 2 is underlined and the HD shaded in gray; the position of the S298X mutation resulting from a Hoxc13 c.893C>A transition is shaded in red. Center: alignment of HOXC13 HD (Tkatchenko et al. 2001) with consensus HD sequence (Bürglin, 1994), and with the regions corresponding to alpha-helical structures (Helices 1, 2, and 3/4) highlighted in blue/green. Bottom: consecutive conserved MEIS protein interacting domains I and II (YGYPFGGSYYGCR; SYQAMPGYLDV)54 located upstream of the HD (gray shading) are highlighted in purple.

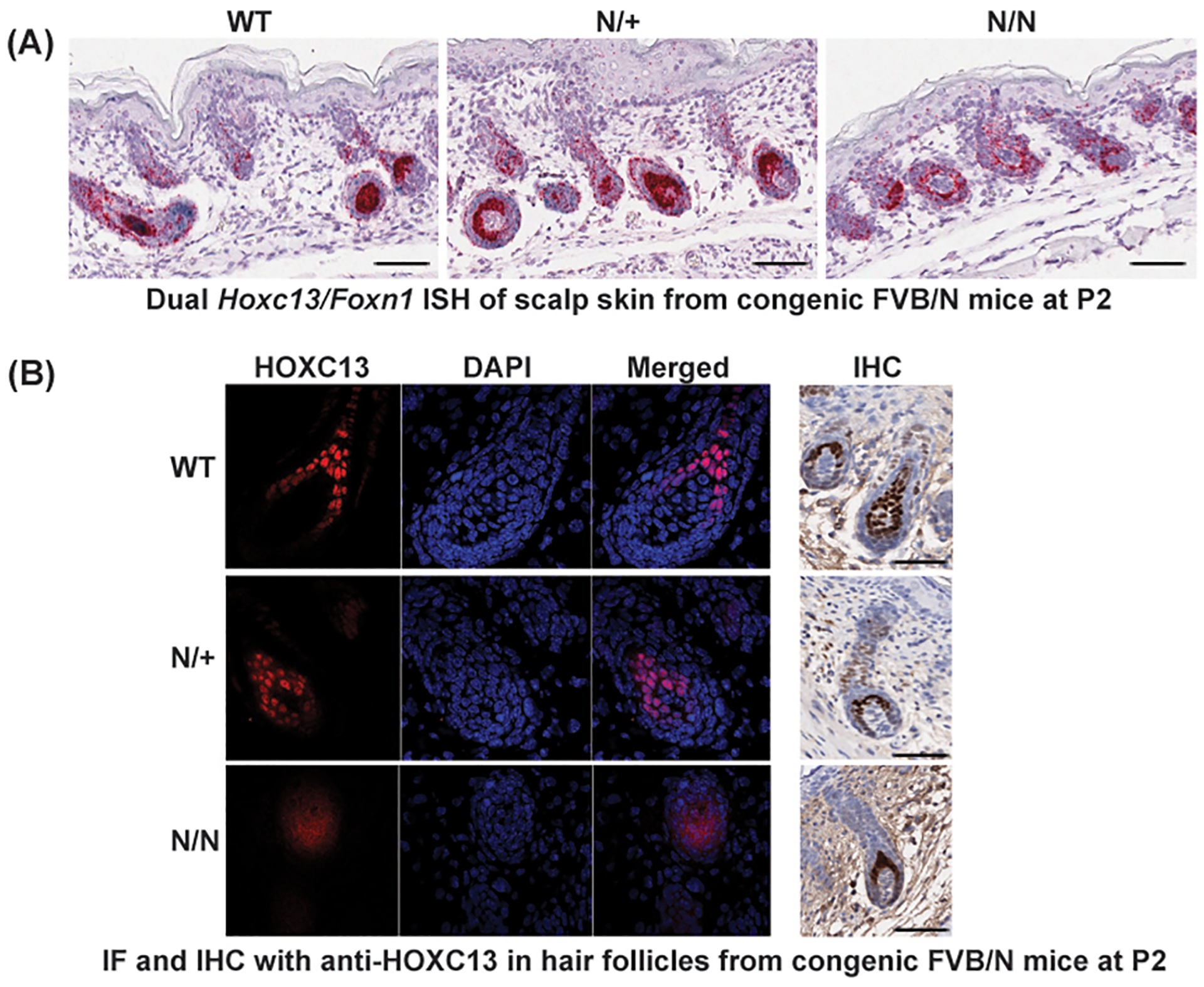

3.3. Mutant Hoxc13N transcript and protein still present in hair follicles

To investigate whether this nonsense mutation resulted in reduced Hoxc13 expression, we analyzed scalp skin from WT, N/+ and N/N mice at postnatal day 2 (P2) by in situ hybridization (ISH), immunofluorescence (IF) and immunohistochemistry (IHC). With the ISH we found that Hoxc13 mRNA was expressed in HFs from all the genotypes during HF morphogenesis, suggesting the mutant transcripts were not subjected to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (Fig. 3A). The IF and IHC images obtained at P2, during HF morphogenesis, showed clear HOXC13 nuclear labelling in keratinocytes from N/+ and WT littermates (although weaker in N/+ mice). However, in N/N mice (P2) the diffuse labeling suggests that the truncated protein is maybe distributed in the cytoplasm and the nucleus (although this diffuse labeling was not consistent across the different time points analyzes by IHC) (Fig. 3B). Still, it is not clear from these studies what is the exact distribution of the truncated protein in the keratinocytes of N/+ mice.

Fig. 3. Transcript and protein expression of the mutant Hoxc13N allele in hair follicles.

(a) In situ hybridization (ISH) of scalp skin from WT, N/+ and N/N mice at P2 showing Hoxc13 mRNA expression (red) in HFs from all three genotypes during HF morphogenesis. The images suggest that the Hoxc13 transcript is present in all genotypes and not degraded by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Differences in Foxn1 mRNA expression (blue) were not observed at this stage (b) The immunofluorescence (IF) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) images (anti-HOXC13 antibody, age P2) show the expected nuclear labelling in keratinocytes from the matrix and medulla in WT and N/+ mice. However, the diffuse labeling in N/N mice suggest the presence of the (predicted truncated) HOXC13 protein in the cytoplasm and nucleus of keratinocytes. The levels of HOXC13 protein as measured by IF seems to be lower in N/N and N/+ HF, when compare with WT skin. Using IF and IHC labeling it was difficult to assess the presence of the truncated protein in the cytoplasm of keratinocytes in N/+ mice. All bars = 50 μm.

3.4. Histopathological and morphological analysis of N/N and N/+ hair follicles

HFs in homozygous N/N mice at P2 were in morphogenetic stages 3 to 6 according to Paus et al.37, while HFs in heterozygous or WT mice were slightly more advanced (stages 5 to 7), suggesting that HF morphogenesis might be retarded in N/N mice. This was confirmed at P5, where HFs in WT mice had mostly advanced to morphogenetic stage 8. At P5, IHC staining for HOXC13 in WT skin showed the expected strong staining in matrix and medulla, with scattered staining in the inner and outer root sheath8, and staining for Keratin 35 (KRT35) showed the expected strong staining in the HS cortex38 (Supplemental Fig. 2A). In N/+ mice of the same age (P5), HF morphogenesis was slightly less advanced (fewer HFs in morphogenesis stage 8), but they were otherwise normal and showed a normal expression pattern for HOXC13 and KRT35 (Supplemental Fig. 2A). In P5 N/N mice, HFs were in earlier stages of morphogenesis, up to stage 7, the stage in which HSs have entered the HF infundibulum but have not penetrated the ostium yet. Those HSs showed evidence of twisting and coiling within the HF infundibulum. The pattern of staining for HOXC13 and KRT35, however, was according to the HF morphogenesis stage (Supplemental Fig. 2A). By P14, WT mice showed mature HFs with the expected expression pattern of HOXC13 and KRT35. At P14, the visibly haired portion of back skin in N/+ mice also showed mature HFs and the same pattern of HOXC13 and KRT35 staining as WT mice (Supplemental Fig. 2B). In the few N/N mice (hybrid F2) of the same age (P14) that were analyzed, HFs exhibited severe coiling and twisting of the HS within the infundibulum. Staining for HOXC13 and KRT35 was also present although weak (Supplemental Fig. 2B). N/N mice did not survive beyond P14 and consequently were not examined at advanced age.

In WT mice examined between P15 and P49, a normal hair cycle was detected, with a catagen phase (P15), a telogen phase (P17), and a subsequent anagen phase (P19 to P32). At P49, another telogen phase had started, as described for normal C57BL/6N mice39. In N/+ mice, the catagen to telogen wave (P15 to P17) and the subsequent initiation of anagen (P19 to P20) was comparable to WT mice, but by P21, anagen development seemed accelerated in N/+ mice with all HFs reaching mature anagen stage 6 at P32, while HFs in WT mice were still in anagen stage 4 (Supplemental Fig. 2C). Differences in the hair cycle between the N/+ and WT genotypes were also evident at P28 in the FVB/N background, as HFs from N/+ mice were in anagen stage 5, whereas WT HFs were in anagen stage 2 (not shown). As mentioned, the macroscopic phenotype of N/+ mice at P40 showed partial alopecia in compared to WT mice. This alopecia is more pronounced in the neck region, where HFs were in telogen, than in the back region where HFs were in late stages of catagen. These hair cycle stages were similar to WT mice and showed the expected wave from rostral to caudal. Thus, the alopecia seems to be caused by increased fragility of HSs and by lack of a certain subtype of HFs (differentiation between guard, awl, auchene, and zigzag hair was not performed) (Fig. 4). The most significant difference in hair cycles was seen at P49, when WT mice were in telogen, but N/+ mice had passed telogen and had already completed the next anagen phase (Supplemental Fig. 2C).

Fig. 4. Histology of the WT and N/+ mutant skin at P40.

Macroscopic (rectangles show areas where skin was harvested) and microscopic (H&E) phenotype of hair coat in N/+ (top) versus WT (bottom) mice at P40. Note partial alopecia in N/+ mice which is more pronounced in the neck region than on the back. Both N/+ and WT show the same pattern of hair cycle, i.e. telogen HF in the neck and late catagen HF in the back. Partial alopecia in N/+ animals may not be due to hair cycle differences but loss of hair fibers (some hair types missing). All bars = 50 μm.

We wondered why the N/+ mice displayed a strong skin phenotype, whereas the heterozygous Hoxc13 KO mice presented with only mild patchy alopecia on the head in 2 out of 4 null lines (independent alleles) (i.e., Hoxc13GFPneo heterozygous mice)36, ruling out haplo-insufficiency for these null alleles. Hence, we characterized the co-expression of Hoxc13 and its downstream target Foxn1 in HFs using ISH (RNA Scope) at P2 and P15. At P2, the levels of Foxn1 and Hoxc13 mRNA (scalp skin) were not statistically significant when comparing the three genotypes (littermates on FVB/N full congenic background) (Fig. 3A). However, at P15, we found a small reduction in both Hoxc13 and Foxn1 mRNA (dorsal skin) in the HFs of the heterozygous N/+ mice, when compared with WT littermates in (C57BL/6 x FVB/N) F2 background. In the N/+ skin, this reduction in mRNA-labelled keratinocytes was greater for Foxn1 than Hoxc13 (Supplemental Fig. 3).

3.5. Slight increase in keratinocyte transit in N/+ epidermis after TPA treatment

To evaluate the response of the skin to the pro-proliferative effect of a tumor promoter, 6–8-week-old N/+ and WT mice (FVB/N full congenic background littermates) were treated topically with 12-O-tetra-decanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA). Following 4 treatments of 3.4 nmol TPA over a 2-wk period, the epidermis of both N/+ and WT mice exhibited similarly mild acanthosis (hyperplasia). These results suggest comparable keratinocyte proliferation rates in N/+ and WT TPA-treated skin (not shown). However, the morphological evaluation of HFs that were topically treated with TPA demonstrated mildly accelerated anagen development in N/+ mice compared to WT animals (not shown). Next, we analyzed keratinocyte transit through the epidermis by following the fate of bromodeoxyuridine- (BrdU) labeled cells at 1 and 8 hrs after BrdU injection (17 hrs after the final TPA application). The transit of keratinocytes was slightly accelerated in N/+ compared with WT skin only at 8 hrs post BrdU injection. At this time point, some labeled keratinocytes in the N/+ epidermis had reached the granular layer, whereas in WT skin, basal and suprabasal keratinocytes retained most of the BrdU-labeled nuclei (Supplemental Fig. 4).

3.6. A CRISPR-created transversion replicates the Naked phenotype

DNA from CRISPR/Cas9 injected mice was extracted from tail tip biopsies according to standard procedures40 and was analyzed by PCR using convenient DNA primers flanking the genome editing event, which resulted in a PCR product of 575 bp in length. The resulting PCR product was digested with MaeI to identify those individuals potentially carrying the mutation of interest (Supplemental Fig. 5). The DNA from potential founders was cloned and sequenced by the Sanger method29 30 (Supplemental Fig. 6). Positive (mosaic) founders B8001 and B8002 carrying the desired point mutation (with a mixed B6;CBA background due to the use of B6CBAF2 embryos for the injections), were bred with C57BL/6JOlaHsd mice to analyze germline transmission. The resulting G1 mice, heterozygous for the mutation (showing both A and C peaks at the targeted base) and displaying partial alopecia, were bred with each other (Supplemental Fig. 7). The resulting G2 mice showed the three distinct phenotypes associated with the WT, heterozygous, and homozygous genotypes for the created mutant allele (Hoxc13em1Lmon) (Supplemental Fig. 7). The few homozygous mice that were recovered died before P7. Finally, we analyzed dorsal skin samples from the three genotypes at P2-P5. The histopathological defects in the skin of our CRIPSR-generated mice replicated those of the Naked mutation (Supplemental Fig. 8). These results confirmed that the nonsense mutation (S298X) found in the Hoxc13 gene in Naked mice is causative for the related phenotype.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study we demonstrate that the spontaneous Naked (N) mutation creates a nonsense allele of the Hoxc13 gene. The presence of alopecia in N/N and N/+ mice supports previous evidence that HOXC13 is required for the normal hair cycle8. We also provide a complete analysis of HF morphogenesis and cycling of N/N and N/+ mice. Using dual ISH (Hoxc13 and Foxn1) we showed that Hoxc13 mRNA expression is similar in all three genotypes and is particularly high in the anagen stages (P7 and P28) of the first postnatal HF cycle. These data suggest the absence of nonsense mediated Hoxc13 mRNA decay. The suspected presence of the truncated protein (diffuse IHC and IF labelling) in the HFs of N/N mice (and potentially in N/+ mice), suggests this could be a dominant-negative mutation. In early HF morphogenesis, differences between the genotypes are unclear. However, as of P5, i.e. when HSs start to enter the infundibulum, coiling and twisting of the HS becomes evident in N/N mice. This morphological feature is similar to the phenotype seen in homozygous Foxn1 (nude) mice. A comparison of back skin from N/+ and WT mice beyond P21 showed an acceleration of the hair cycle wave in N/+ mice compared to the WT genotype. This acceleration of anagen development was also seen in TPA-treated animals. Interestingly, it was previously shown in a C57BL/6 background that the response of N/+ mutants to a two-stage (chemical) skin carcinogenesis protocol showed 100% incidence (mice with tumors) and increased average tumor burden per mouse, when compared to littermate WT controls41. Nonetheless, we recognize that our work has the limitation of being a descriptive study without any functional verification.

While the exact causes for the partial alopecia in N/+ mice are currently unknown, transcriptional control mechanisms specifying regional restrictions of ectodermal Hoxc13 expression levels are most likely associated with this phenomenon. Recently published data showed the existence of two ectodermal enhancers, EC1 and EC2, that are located 165 and 81 kb upstream of the Hoxc cluster and that combined are critical for regulating Hoxc expression levels (including Hoxc13 mRNA levels) in a regionally sensitive manner42. Although mice homozygous for both EC1 and EC2 deletion looked overall healthy, they exhibited nail abnormalities and an overall disheveled fur coat with an accelerated HF and patches of alopecia42. These Hoxc expression level-dependent effects on the hair cycle are consistent with data implicating Hoxc13 in hair cycle control8. Interestingly, further 3’ Hoxc genes (Hoxc10, Hoxc9, Hoxc8, Hoxc6, and Hoxc4) were shown to specify positional identities in a co-linear fashion along the longitudinal axis of dorsal skin through their activities in dermal papillae and dermal fibroblasts6. This involves Wnt-dependent signaling to stimulate regional epithelial stem cells and HF regeneration during the hair cycle. Interestingly, HOXC13 was shown to be critical for controlling HF regeneration through the TGFß/Smad2 pathway8, presumably by interpreting the regionally distinct mesenchymal signals. Combined with the observation from the EC1/EC2 deletion studies suggesting that ectodermal Hoxc13 expression needs to reach certain threshold levels for proper differentiation of region-specific ectodermal structures42, this may explain the regionally distinct alopecia in the head and anterior trunk of N/+ mice; in these regions natural ectodermal Hoxc13 expression would be expected to be at its lowest levels thus making them particularly sensitive to the effects of a truncated, yet still partially functional HOXC13 protein as discussed further below.

In the late 1990s Dr. Mario Capecchi’s group created four different loss-of-function (LOF) alleles of the Hoxc13 transcription factor, namely Hoxc13neo (Hoxc13tm1Mrc), Hoxc13lacZ (Hoxc13tm2Mrc), Hoxc13GFPneo (Hoxc13tm3Mrc) and Hoxc13GFPlox (Hoxc13tm3.1Mrc). As expected for LOF alleles, all show phenotypes when homozygous null (KO); however, two of these alleles showed a very mild skin phenotype (very small areas lacking hair) when heterozygous. The authors speculated that these fusion proteins may have the ability to interact with the transcription complex36. For all of the null alleles, only 10% of homozygous KO mice survive to adulthood, and although they are fertile, they are completely hairless7 36. Like the LOF mice, Hoxc13 transgenic mice (FVB/NTac-Tg(Hoxc13)61B1Awg/J) overexpressing HOXC13 in differentiating HF keratinocytes also develop alopecia15. In addition to the mouse, there are other species carrying genetically engineered LOF alleles of the Hoxc13 gene that are potential animal models for ECTD-9, for example, pigs43 and rabbits44 created using CRISPR/Cas technology. As in the Hoxc13 KO mice, these pig and rabbit LOF alleles are recessive, with heterozygous animals indistinguishable from WT. Homozygous KO pigs have a complete lack of external hair and abnormal nails, with a reduced number of HFs and abnormal HSs. No skeletal abnormalities were described for the KO pigs and the survival rate was around 75%43. In the case of the KO rabbits, hair loss was complete on the head and dorsum, but not in the limbs or tails, with around 15% of animals surviving into adulthood. These animals also displayed an increase in the number of caudal vertebrae. Interestingly, the authors described a reduced number of HFs, compared with WT rabbits, in the dorsum, head, tail, and limbs. In contrast with the mouse and pig models, an increased number of sebaceous glands was found in the KO rabbits44.

A variety of mutations affecting HOXC13 has been associated with human ECTD9, including missense23 22, frameshift21, and nonsense20 45 mutations. All of these have been described as LOF alleles with low levels of Hoxc13 transcripts, as would be expected if the mutant transcripts contained premature stop codons and were subjected to nonsense-mediated RNA decay. This presumptive RNA decay is seen not only in the missense mutations affecting the DNA binding homeodomain (HD) but also in the premature stop codon mutations that produce truncated transcripts lacking the C-terminal HD. All cases of human ECTD9 described so far appear to be due to recessive mutations.

There are a number of possible explanations for the semi-dominant character of the mouse Hoxc13N (spontaneous) and Hoxc13em1LMon (genome edited) mutant alleles. The S298X nonsense mutation results in a truncation of HOXC13 just prior to helix 3 of the HD (Fig. 5). HD helix 3 is the most critical for the interaction of HOX proteins with their core recognition sequence in the major groove of the DNA double helix, whereas the N-terminal arm of the HD is important for making DNA contact via the minor groove46. Nonetheless, HD helix 3 may also be involved in protein-protein interactions47 that are separate from those mediated by distinct protein-protein interacting domains in both HOX and other HD-containing proteins, including HD helix 1, a conserved N-terminal arm present in certain HOX proteins48, and a conserved hexapeptide (HX) common to most ANTP-class HOX proteins that is located near the N-terminal end of the HD49. The HX domain mediates the formation of HOX/PBX co-factor complexes that increase DNA binding specificity through cooperative binding to target sequences. However, paralogous group 13 HOX proteins lack a conserved HX but are capable of cooperating with members of the MEIS group of HD co-factors. The HOX-MEIS interaction is mediated through separate, conserved MEIS-interacting domains I and II in the HOX protein50. In HOXC13, domains I and II encompass amino acid residues 119–131 (YGYPFGGSYYGCR) and residues 179–189 (SYQAMPGYLDV)51, respectively, and both are intact in HOXC13S298X. Accordingly, mutant HOXC13S298X/MEIS complexes in heterozygous mice may compete with native HOXC13/MEIS complexes for binding to target sequences resulting in changes in the transcriptional regulation of HOXC13 target genes and/or the selection of different sets of target genes. Although the HOX/MEIS interaction does not appear to be required for hair keratin gene regulation13, this does not exclude potential effects on the cooperative binding to regulatory elements of other genes involved in controlling HF and HS differentiation, such asFoxq112 and Foxn111.

Although cooperative binding to select DNA target sequences by HOX/co-factor complexes increases regulatory specificity, the sign (activation or repression) and strength of transcriptional regulation may be affected by HOX collaborators that bind to DNA adjacent to HOX/co-factor complexes49 52. An important group of presumptive HOXC13 collaborators comprises members of the SMAD family of BMP/TGF-β signaling effector proteins. As pointed out above, HOXC13 plays a critical role in hair cycle control that is apparently mediated through targeting of the TGF-β signaling effector SMAD28. The data show increased SMAD2 expression in HFs treated with Hoxc13-silencing shRNA, whereas administration of a HOXC13 peptide resulted in down-regulation of phosphorylated SMAD2. Although the molecular mechanisms underlying this observation remain undefined, prior studies have documented interactions between SMADs and specific HOX proteins, including proteins encoded by the HOX paralogous group 13 genes HOXA13 and HOXD1353 54. However, the specific peptide motifs required for these interactions may vary depending on the HOX and SMAD protein. For example, yeast two-hybrid and gel shift assays identified two separate HOX interacting domains, HID1 and HID2 near the N-terminus of SMAD1 as critical for a HD-dependent interaction with HOXC853. Yet, HOXA13 and HOXD13 interact with the C-terminal MAD homology domains (MH2) of SMAD1, SMAD2, and SMAD5, rather than HID1 and HID2, independent of HD binding capability54. Distinct HD-independent functions have been observed for other HD proteins, including the naturally occurring HD-less Hth/MEIS isoforms in both Drosophila and vertebrates49. Notably, the functional significance of protein-protein interactions in HD protein function was originally documented by experiments with the Drosophila segmentation gene ftz, as interactions between HD-less Ftz and wild-type Prd protein were still sufficient for ftz-dependent segmentation55.

In summary, the cases of HOX-cofactor/HOX-collaborator interactions highlighted above can only capture a small fraction of the complete spectrum of possible protein-protein interactions likely to be available for the Hoxc13S298X mutant allele. Multiprotein transcriptional complexes that assemble with HOX proteins at their core and that may include different types of co-factors and diverse collaborators are also known as Hoxasomes49. This term is meant to reflect the enormous functional flexibility of HOX proteins, which may account for the phenotypic plasticity observed for an increasing number of Hox mutants, including Hoxc13.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Research Animal Support Facility-Smithville for their assistance with the maintenance of the mouse strains, the Smithville Next Generation Sequencing Core (CPRIT Core Facility Support Award grant number RP170002) for exome sequencing, the Science Park Flow Cytometry and Cellular Imaging Core (CPRIT Core Facility Support Award grant number RP170628) for the confocal studies, and Yi Zhong for the bioinformatics analyses. We also acknowledge Briana Dennehey for proofreading the manuscript. This study made use of the Laboratory Animal Genetic Services, the Research Histology, Pathology and Imaging core, and the High Resolution Electron Microscopy Facility, all which are supported by P30 CA016672 DHHS/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant to MD Anderson Cancer Center. This work was partially supported by Departmental Funds to FB and by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) BIO2015–70978-R and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MICINN) RTI2018-101223-B-I00 to LM.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Awgulewitsch A Hox in hair growth and development. Naturwissenschaften. 2003;90(5):193–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chuong CM, Noveen A. Phenotypic determination of epithelial appendages: genes, developmental pathways, and evolution. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4(3):307–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mentzer SE, Sundberg JP, Awgulewitsch A, et al. The mouse hairy ears mutation exhibits an extended growth (anagen) phase in hair follicles and altered Hoxc gene expression in the ears. Vet Dermatol. 2008;19(6):358–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu J, Husile, Sun H, et al. Adaptive evolution of Hoxc13 genes in the origin and diversification of the vertebrate integument. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2013;320(7):412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Millar SE. Hox in the Niche Controls Hairy-geneity. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23(4):457–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu Z, Jiang K, Xu Z, et al. Hoxc-Dependent Mesenchymal Niche Heterogeneity Drives Regional Hair Follicle Regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23(4):487–500 e486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godwin AR, Capecchi MR. Hoxc13 mutant mice lack external hair. Genes Dev. 1998;12(1):11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiu W, Lei M, Tang H, et al. Hoxc13 is a crucial regulator of murine hair cycle. Cell Tissue Res. 2016;364(1):149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jave-Suarez LF, Winter H, Langbein L, Rogers MA, Schweizer J. HOXC13 is involved in the regulation of human hair keratin gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(5):3718–3726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shang L, Pruett ND, Awgulewitsch A. Hoxc12 expression pattern in developing and cycling murine hair follicles. Mech Dev. 2002;113(2):207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potter CS, Pruett ND, Kern MJ, et al. The nude mutant gene Foxn1 is a HOXC13 regulatory target during hair follicle and nail differentiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(4):828–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potter CS, Peterson RL, Barth JL, et al. Evidence that the satin hair mutant gene Foxq1 is among multiple and functionally diverse regulatory targets for Hoxc13 during hair follicle differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(39):29245–29255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jave-Suarez LF, Schweizer J. The HOXC13-controlled expression of early hair keratin genes in the human hair follicle does not involve TALE proteins MEIS and PREP as cofactors. Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;297(8):372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Godwin AR, Capecchi MR. Hair defects in Hoxc13 mutant mice. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4(3):244–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tkatchenko AV, Visconti RP, Shang L, et al. Overexpression of Hoxc13 in differentiating keratinocytes results in downregulation of a novel hair keratin gene cluster and alopecia. Development. 2001;128(9):1547–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterson RL, Tkatchenko TV, Pruett ND, Potter CS, Jacobs DF, Awgulewitsch A. Epididymal cysteine-rich secretory protein 1 encoding gene is expressed in murine hair follicles and downregulated in mice overexpressing Hoxc13. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10(3):238–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potter CS, Kern MJ, Baybo MA, et al. Dysregulated expression of sterol O-acyltransferase 1 (Soat1) in the hair shaft of Hoxc13 null mice. Exp Mol Pathol. 2015;99(3):441–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mecklenburg L, Nakamura M, Sundberg JP, Paus R. The nude mouse skin phenotype: the role of Foxn1 in hair follicle development and cycling. Exp Mol Pathol. 2001;71(2):171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mecklenburg L, Paus R, Halata Z, Bechtold LS, Fleckman P, Sundberg JP. FOXN1 is critical for onycholemmal terminal differentiation in nude (Foxn1) mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123(6):1001–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin Z, Chen Q, Shi L, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in HOXC13 cause pure hair and nail ectodermal dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91(5):906–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farooq M, Kurban M, Fujimoto A, et al. A homozygous frameshift mutation in the HOXC13 gene underlies pure hair and nail ectodermal dysplasia in a Syrian family. Hum Mutat. 2013;34(4):578–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Orseth ML, Smith JM, Brehm MA, Agim NG, Glass DA 2nd. A Novel Homozygous Missense Mutation in HOXC13 Leads to Autosomal Recessive Pure Hair and Nail Ectodermal Dysplasia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34(2):172–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan AK, Muhammad N, Aziz A, et al. A novel mutation in homeobox DNA binding domain of HOXC13 gene underlies pure hair and nail ectodermal dysplasia (ECTD9) in a Pakistani family. BMC Med Genet. 2017;18(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo J, Wang Z, Huang J, et al. HOXC13 promotes proliferation of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma via repressing transcription of CASP3. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(2):317–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao Y, Luo J, Sun Q, et al. HOXC13 promotes proliferation of lung adenocarcinoma via modulation of CCND1 and CCNE1. Am J Cancer Res. 2017;7(9):1820–1834. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lebedinsky NGaD A Atrichosis und ihre Vererbung beider albinotischen Hausmaus. Biol Zentralbl. 1927;47:748. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flanagan S, and Isaacson J. Close linkage between genes which cause hairlessness in the mouse. . Genetical Research. 1967;9(1): 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliveros JC, Franch M, Tabas-Madrid D, et al. Breaking-Cas-interactive design of guide RNAs for CRISPR-Cas experiments for ENSEMBL genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W267–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munoz-Santos D, Montoliu L, Fernandez A. Generation of Genetically Modified Mice Using CRISPR/Cas9. Methods Mol Biol. 2020;2110:129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernandez A, Morin M, Munoz-Santos D, et al. Simple Protocol for Generating and Genotyping Genome-Edited Mice With CRISPR-Cas9 Reagents. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol. 2020;10(1):e69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harms DW, Quadros RM, Seruggia D, et al. Mouse Genome Editing Using the CRISPR/Cas System. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2014;83:15 17 11–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez CJ, Mecklenburg L, Jaubert J, et al. Increased Susceptibility to Skin Carcinogenesis Associated with a Spontaneous Mouse Mutation in the Palmitoyl Transferase Zdhhc13 Gene. J Invest Dermatol. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tiano HF, Loftin CD, Akunda J, et al. Deficiency of either cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 or COX-2 alters epidermal differentiation and reduces mouse skin tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2002;62(12):3395–3401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sundberg J Handbook of mousemutations with skin and hair abnormalities: animal models and biomedical tools. . Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hogan ME, King LE Jr., Sundberg JP. Defects of pelage hairs in 20 mouse mutations. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104(5 Suppl):31S–32S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Godwin AR, Stadler HS, Nakamura K, Capecchi MR. Detection of targeted GFP-Hox gene fusions during mouse embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(22):13042–13047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paus R, Muller-Rover S, Van Der Veen C, et al. A comprehensive guide for the recognition and classification of distinct stages of hair follicle morphogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113(4):523–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moll R, Divo M, Langbein L. The human keratins: biology and pathology. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;129(6):705–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muller-Rover S, Handjiski B, van der Veen C, et al. A comprehensive guide for the accurate classification of murine hair follicles in distinct hair cycle stages. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117(1):3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Behringer R, Gertsenstein M, Vintersten Nagy K, Nagy A Manipulating the mouse embryo-A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sundberg JP, Sundberg BA, Beamer WG. Comparison of chemical carcinogen skin tumor induction efficacy in inbred, mutant, and hybrid strains of mice: morphologic variations of induced tumors and absence of a papillomavirus cocarcinogen. Mol Carcinog. 1997;20(1):19–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fernandez-Guerrero M, Yakushiji-Kaminatsui N, Lopez-Delisle L, et al. Mammalian-specific ectodermal enhancers control the expression of Hoxc genes in developing nails and hair follicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(48):30509–30519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han K, Liang L, Li L, et al. Generation of Hoxc13 knockout pigs recapitulates human ectodermal dysplasia-9. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(1):184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deng J, Chen M, Liu Z, et al. The disrupted balance between hair follicles and sebaceous glands in Hoxc13-ablated rabbits. FASEB J. 2019;33(1):1226–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ali RH, Habib R, Ud-Din N, Khan MN, Ansar M, Ahmad W. Novel mutations in the gene HOXC13 underlying pure hair and nail ectodermal dysplasia in consanguineous families. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(2):478–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joshi R, Passner JM, Rohs R, et al. Functional specificity of a Hox protein mediated by the recognition of minor groove structure. Cell. 2007;131(3):530–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruun JA, Thomassen EI, Kristiansen K, et al. The third helix of the homeodomain of paired class homeodomain proteins acts as a recognition helix both for DNA and protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(8):2661–2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zappavigna V, Sartori D, Mavilio F. Specificity of HOX protein function depends on DNA-protein and protein-protein interactions, both mediated by the homeo domain. Genes Dev. 1994;8(6):732–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mann RS, Lelli KM, Joshi R. Hox specificity unique roles for cofactors and collaborators. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2009;88:63–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams TM, Williams ME, Innis JW. Range of HOX/TALE superclass associations and protein domain requirements for HOXA13:MEIS interaction. Dev Biol. 2005;277(2):457–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bürglin TR. Comprehensive Classification of Homeobox Genes. In: Duboule D, ed. Guidebook to the Homeobox Genes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rezsohazy R, Saurin AJ, Maurel-Zaffran C, Graba Y. Cellular and molecular insights into Hox protein action. Development. 2015;142(7):1212–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang X, Ji X, Shi X, Cao X. Smad1 domains interacting with Hoxc-8 induce osteoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(2):1065–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams TM, Williams ME, Heaton JH, Gelehrter TD, Innis JW. Group 13 HOX proteins interact with the MH2 domain of R-Smads and modulate Smad transcriptional activation functions independent of HOX DNA-binding capability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(14):4475–4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Copeland JW, Nasiadka A, Dietrich BH, Krause HM. Patterning of the Drosophila embryo by a homeodomain-deleted Ftz polypeptide. Nature. 1996;379(6561):162–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.