Abstract

Soft tissue complications are among the most common reasons for revision surgery following transdermal, bone-anchored osseointegration. While many orthopaedic surgeons are familiar and experienced with the use of intramedullary implants, the soft tissue management surrounding a percutaneous and permanent implant in continuity with the outside environment remains a challenging problem. With this in mind, we present our rationale and a framework for soft tissue considerations in preparation for bone-anchored osseointegration based on early experiences with most commercially available osseointegration systems.

Keywords: soft tissue, bone-anchored osseointegration, transdermal bone-anchored implants

1. Introduction

Transdermal bone-anchored implants are being increasingly used as a method to improve the function of patients with amputations by altering the interface between prosthesis and residual limb. The technique has the most benefit in patients who have experienced challenges with conventional, socket-based prosthesis suspension due to short residual limbs, recurrent soft tissue breakdown, problematic heterotopic ossification, or socket-related residual limb pain. Direct skeletal attachment enables increased prosthetic use with faster and more efficient locomotion,1 improved balance,2 proprioceptive feedback of the prosthetic limb (osseoperception),3 improved quality of life scores,4,5 easier prosthetic fitting, donning and doffing,6 and increased range of motion and comfort when sitting.7 Recent reviews of outcomes in patients with transdermal, bone-anchored implants have highlighted these functional benefits while also demonstrating an increasingly favorable safety profile, as the frequency and severity of infection has decreased with better implant designs, improved patient selection and refinement of surgical techniques and soft tissue management.8,9

Despite advances in technique and technology, a stable and durable seal between the implant and surrounding soft tissue has remained elusive. Transdermal bone-anchored implants are a trade-off between improvements in function and quality of life and a chronic wound at the interface between the percutaneous metal abutment and the surrounding soft tissue. This interface has been labelled the skin penetration site or stoma but is better classified as a skin penetration aperture. The aperture is identified as the most frequent site of complications following osseointegration but unfortunately, it is also the least well detailed or understood in the published literature. Rates of soft tissue complications vary depending on implant type, surgical and patient factors, as well as amputation level. Overall, rates of soft tissue complications have been reported between 29% and 77% for infections requiring antibiotics, and soft tissue complications are the most common reason for revision surgery.10 Robust studies of soft tissue outcomes in the literature are lacking, as demonstrated by a 2018 systematic review by Atallah et al,11 where comprehensive soft tissue outcomes were reported in only one of 12 studies that met criteria for analysis.

We aim to provide a conceptual framework to better understand the soft tissue considerations unique to transdermal implants with the goal of better balancing the risks associated with different surgical strategies and guiding the management of complications that stem from implantation of a permanent, percutaneous device. The proposed framework is extrapolated from experience using the Osseoanchored Prosthesis for Rehabilitation of Amputees (OPRA; Integrum AB, Göteborg, Sweden) implant system, as well as case studies managing an array of soft tissue complications arising from all types of commercially available implants in over 100 limbs.

2. Implant Systems

There are currently three types of transdermal bone-anchored implants available for clinical use: a long porous-coated stem system, a compliant prestress compression system, and a roughened, threaded implant. All implants achieve direct cortical connection with the bone, allowing for osseointegration. The long porous-coated stem implant systems include the Osseointegrated Prosthetic Limb (OPL; Permedica, Merate, Italy), Integral Leg Prosthesis (ILP; Orthodynamic GmbH, Lübeck, Germany), and OTN (BADAL; OTN Implants, Nijmegen, Netherlands). Each implant consists of a fully porous-coated stem and typically range in length from 150 to 180 mm. Long porous-coated stem systems were traditionally placed in a two-stage process, but recent evidence has demonstrated improved outcomes with a single-stage use of these systems.12 The Compress system (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN) uses compliant prestress compression of 600–800 lbs to achieve osseointegration and requires only 45 mm of residual bone. Both the long porous-coated stem implant and Compress system have a broad distal end of the implant that covers the end of cortical bone. Conversely, the OPRA implant is the only threaded implant system (albeit roughened and fenestrated, allowing for bony ongrowth and ingrowth), and its intramedullary component is covered with distal bone graft. The recommended use of bone grafting to cover and protect the countersunk OPRA implant requires a two-stage approach, with subsequent creation of the skin penetration aperture and placement of the abutment typically three to six months following implant placement and bone grafting. The OPRA implant system is currently the only FDA approved transdermal bone-anchored implant, obtaining premarket approval for patients with transfemoral amputations in 2020.

3. Implant-Based Soft Tissue Strategies

Placement of the OPRA implant is performed in two stages. During the first stage, there is minimal soft tissue work specific to implant placement, but a vertical thighplasty may be performed to reduce the degree of global soft tissue motion present in the residual limb. The first stage procedure aims to provide vascularized coverage over the end of the implant to prevent early infection and optimize incorporation of the bone graft. At second stage surgery, a stable myoplasty is created using the quadriceps and hamstring muscles with anchorage to the periosteum around the distal bone. The fasciocutaneous tissue of the residual limb is thinned to a sub-Scarpal layer and quilted to the muscle platform to facilitate adherence between these layers. The aperture site is selected, and the skin that will overlie the bone surrounding the abutment is thinned to the level of the dermis to encourage adherence to the bone (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

OPRA implant system demonstrating the soft tissue surrounding the abutment thinned to the level of the dermis. This technique aims to minimize soft tissue motion by promoting adherence of the skin to the bone surrounding the abutment.

During implantation of a single stage, long porous-coated stem system, the intramedullary implant and distal extension covers the end of cortical bone, and the muscles are sutured to the distal periosteum (Fig. 2). Management of the skin penetration site has varied, but centering the skin penetration aperture within the suture line of a fish-mouth incision at end of the residual limb has been described. Frequently, a posteriorly based flap is used to cover the implant, and a core of skin and fat is excised for the abutment. More recently, authors advocate thinning this flap to reduce the thickness of the soft tissues surrounding the abutment to reduce irritation, excess motion, and drainage.

Figure 2.

A long porous-coated stem system without soft tissue thinning.

4. Discussion

The presence of a permanent, percutaneous implant in communication with the environment creates a novel soft tissue challenge that has yet to be fully understood or optimally managed. The experience and outcomes of osseointegrated implants used in the head and neck (small implants penetrating thin, adherent, and well vascularised tissue in a heavily colonized but permissive microenvironment) are not comparable with the soft tissue considerations of the residual limb. The larger transdermal components used for direct skeletal attachment of extremity prostheses must withstand considerably greater forces and reside within a residual limb soft tissue envelope of varying thickness and comparatively decreased vascularity. Furthermore, the large degree of soft tissue motion present in the residual limb poses the single greatest challenge to the health of the transdermal implant. Relative motion between the fixed transdermal abutment and the surrounding soft tissues has thwarted all efforts to achieve soft tissue integration and drives the chronic inflammation and infection that complicates our current surgical strategies.

Early implant designs attempted to achieve soft tissue integration to the implant with a roughened surface at the soft tissue interface. These porous surfaces were thought to enhance cellular ingrowth, but the interface could not withstand micromotion between the soft tissues and abutment, causing the roughened surface to act as an abrasive rather than an integrating surface. The combination of large surface area and traumatic fluid resulted in unacceptably high rates of wound infection with unplanned reoperation rates secondary to infection occurring in 77% of patients.8 While preclinical research in soft tissue metal integration is ongoing, these early devices are no longer in use (eg, ITAP, Intraosseous Transcutaneous Amputation Prosthesis, UK) or the design has been modified using smooth, nonabrasive materials with a significant reduction in infection rates.8 This problem of a roughened surface continues to cause infectious complications in modern bone-anchored implants if distal bone resorption results in exposure of the textured titanium (designed for skeletal integration) to the soft tissue envelope. Given the inability to achieve a durable soft tissue seal around the percutaneous abutment, all existing bone-anchored implants rely on a smooth metal-alloy soft tissue interface. While this smooth interface minimizes trauma and decreases the surface area of the percutaneous component, it necessitates the existence of a chronic wound. As a result, efforts to achieve a seal through soft tissue integration have been entirely supplanted by surgical and technological efforts to modulate the wound environment, achieve and maintain symbiosis between the skin flora and the device aperture, and decrease wound-related complications.

The soft tissue interface surrounding the percutaneous abutment of an osseointegrated prosthesis is a chronic site of inflammation. Relative motion between the rigid abutment and surrounding soft tissue serves as an inflammatory stimulus that drives increased drainage, formation of unstable granulation tissue, and pain. When combined with unfavorable bacterial species, this cascade contributes to a transition from chronic colonization to active infection as discussed in greater detail in the infection portion of this supplement. While there is consensus that efforts are needed to minimize infection through modulation of the wound microenvironment through novel dressings, topical solutions, light-based therapies, and electrical stimulation,13,14 the role of relative motion as a driver for infection has been variably acknowledged. As a result, surgical approaches to manage the peri-abutment soft tissue range from extensive thinning and devascularization to percutaneous implantation with minimal soft tissue manipulation. In the absence of a framework for understanding soft tissue considerations, surgical management has been largely driven by dogma and distributed through apprenticeship experience.

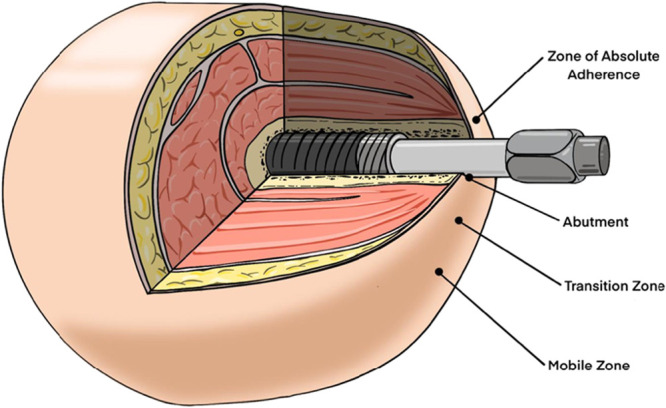

To address this gap, we introduce three key concepts and a zone-based guide to understanding and altering the soft tissues of the residual limb before, during, and after transdermal bone-anchored implant surgery. This framework is derived from experience managing complications stemming from numerous clinically available implant systems. While the nature, frequency, and severity of soft tissue complications will vary between implant systems on account of implant-specific surgical techniques, there are commonalities to the soft tissue behavior that transcend implant type. Any comprehensive soft tissue strategy must seek to balance three key factors: vascularity, relative motion, and loss of containment. The importance of these factors is most apparent in the transfemoral residual limb, where the soft tissue envelope must accommodate a large degree of femoral motion, excessive skin and adipose tissue, and the effects of gravity as it alters distribution of tissue based on position.

4.1. Tissue Vascularity

Effectively manipulating the soft tissues of the residual limb requires an understanding of the blood supply to these tissues. Skin and superficial subcutaneous tissue are perfused through discrete perforators that mostly exist in areas of fascial attachment. This system enables extensive elevation and widespread undermining of the soft tissues of the thigh with minimal impact on tissue perfusion. Similarly, the superficial perfusion pattern enables debulking of the sub-Scarpal fat without compromising perfusion of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Further thinning is subject to length to width ratios that guide design of all random pattern flaps perfused exclusively through the subdermal plexus.

4.2. Relative Motion

Motion of the soft tissue envelope around the abutment causes inflammation and drives hypergranulation tissue formation, even when extensive efforts are undertaken to stabilize the soft tissue. This motion and inflammation causes increased drainage and exacerbate pain with ambulation. Furthermore, the motion exists in both horizontal and vertical dimensions. Horizontal motion can result in widening of the interface and facilitates increased drainage, whereas vertical pistoning is often associated with stenosis that temporarily traps fluid around the abutment and is particularly painful if the tissues piston over the transition between the dual cone implant and abutment in long porous-coated stem systems.

4.3. Loss of Containment

The residual limb in patients with an amputation lacks the normal distal muscular and fascial attachments for tissue stability. Conventional socket-based prostheses compress and contain the residual limb tissues within the liner and socket. In a limb with a transdermal bone-anchored implant, the skin, fat, and musculature are not contained and can have both functional and cosmetic considerations. The movement of the uncontained thigh during ambulation can cause pain, abrasions, and skin irritation rubbing on the contralateral thigh or clothing, and soft tissue redundancy may interfere with the prosthetic components. The unconstrained motion of the proximal residual limb soft tissues often translates into increased soft tissue motion at the distal interface around the abutment. In patients treated with the OPRA system, failure to address proximal soft tissue motion can cause loss of adherence of previously well-fixed peri-aperture tissues.

5. A Zonal Approach to Soft Tissue Management in Transdermal Bone-Anchored Implants

5.1. Zone of Maximal Motion

The soft tissue above the implant is mobile due to the loss of containment. The adductor roll area is the main contributor to this movement and is best addressed through vertical thighplasty. Nonsurgical interventions include compressive/suspension garments.

5.2. Zone of Transition

The area over the distal residual limb is a transition zone of movement dampening the effect of proximal soft tissue motion on the behavior of the soft tissues adjacent to the implant. Efforts to thin the skin flap and promote adherence to the underlying platform serve to broaden the zone of transition and decrease the magnitude of force and degree of excursion experienced at the soft tissue interface with the abutment. The surgical management of this zone is a delicate balance between maintaining vascularity while minimizing motion.

5.3. Zone of Adherence

The surgical technique employed by the OPRA system aims to eliminate motion at the interface with the abutment by adhering skin to the underlying bone and muscle platform. Adherence comes at the cost of increased risk of ischemia-related wound healing complications. To mitigate wound healing complications, we have used skin grafts and dermal regenerative templates in both the OPRA and long porous-coated stem systems to achieve minimal soft tissue motion within the zone of adherence. Although single-stage and two-stage surgical techniques vary by device, all strategies for management of soft tissue about the skin penetration aperture have converged on a “less is more” approach.

6. Current Surgical Strategies

OPRA and long porous-coated stem systems represent two ends of the spectrum between motion and vascularity, as represented in Figure 3. The expected soft tissue complications are different between these approaches with greater likelihood of wound healing/ischemic complications with the OPRA implant system and increased drainage and motion-related discomfort with long porous-coated implants. Thinning of the skin flap just deep to Scarpa's fascia may limit the extent or severity of motion-related complications while mitigating against wound complications secondary to compromised flap vascularity. In both long-stem and threaded transdermal bone-anchored systems, inflammation can occur at the attachment created between the distal muscular platform and periosteum that can cause pain with active manipulation of the residual limb. This pain must be differentiated from that attributable to infection or irritation of the aperture, as strategies for management differ and must be targeted to the etiology of the pain.15

Figure 3.

Spectrum of relative motion and tissue vascularity with various transdermal bone-anchored implant systems.

Transdermal bone-anchored implant surgery is technically straightforward but conceptually challenging. Some longstanding dogma around exposed metalwork have been challenged by the experience of the last 30 years in this patient cohort. The technology of implants continues to develop, as do the surgical and rehabilitative protocols, with corresponding decreases in reported complications.16 The operative and perioperative care of the patient is modest compared with the lifelong integrated care the patient will require. As such, while surgical outcomes are optimized through use of an integrated orthoplastic team approach, it is imperative that the patient receive care by an experienced and engaged rehabilitation, physical therapy, and prosthetics team. Systematized soft tissue surveillance and reporting and patient education is mandatory to manage the aperture in the long term.

The ideal aperture will have minimal or no discharge, require simple self-care, have a stable microbiome with minimal soft tissue infections,17 and be able to tolerate the function and environments that the patient demands. Early detection and treatment of soft tissue complications that occur will minimize both long term morbidity, risks of deep infection, implant loss, and may decrease the potential for malignant change of the chronic wound (a theoretical risk to date). If the soft tissue challenges imposed by percutaneous osseointegration can be effectively managed, the patient can fully realize the dramatic functional benefits offered by direct skeletal attachment of extremity prostheses.

Appendix 1. Contributors

Members of the Global Collaborative Congress on Osseointegration (GCCO): Joseph R. Hsu1, Rachel B. Seymour1, Benjamin K. Potter2, Danielle Melton3, Bailey V. Fearing2, Leah Gitajn4, Jason Hoellwarth5, Robert Rozbruch5, Jason Souza6, Amber Stanley1, Jason Stoneback7, Meghan K. Wally1, Josh Wenke8. 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Atrium Health Musculoskeletal Institute, Charlotte, NC; 2University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA; 3University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO; 4Dartmouth Health, Lebanon, NH; 5Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY; 6Departments of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery & Orthopedic Surgery, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH; 7Department of Orthopedics, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO; 8University of Texas Medical Branch, Shriners Hospitals for Children, Galveston, TX.

Footnotes

Disclosures of conflicts of interest: Leah Gitajn received consulting fees from Stryker and Paragon28. She also has a leadership or fiduciary role in the OTA program committee and AO research committee. Danielle Melton has DoD contract OP220013 and CDMRP Grant OR210169. She also has consulting fees for Paradigm Medical Director and has received payment for lectures at the State of the Science Conference on Osseointegration. Danielle Melton has received payment for expert testimony while acting as a consultant and expert witness in multiple cases. She has received support from Amputee Coalition BOD to travel and attend meetings. She has participated in the Data Safety Monitoring Advisory Board for External Advisory Panel for Limb Loss Prevention Registry. Danielle Melton has a leadership or fiduciary role in METRC Executive Council, Amputee Coalition Board of Directors, and in Catapult Board of Directors. Kyle Potter has a CDMRP PRORP grant/contract with DoD-USUHS Restoral. He also has consulting fees with Integrum and Signature. Dr. Hsu reports consultancy for Globus Medical and personal fees from Smith & Nephew speakers' bureau. Robert Rozbruch reports consulting fees from Nuvasive and J&J. He also reports having stock with Osteosys. Jason Stoneback reports royalties from AQ Solutions as well as consulting fees from AQ Solutions and Smith and Nephew. He reports payment for lectures from Smith and Nephew and AQ Solutions. Jason Stoneback states he has received payment for expert testimony in multiple cases. He notes he has received support to travel and attend meetings from Smith and Nephew and AQ Solutions. He reports planning a patent for a Rotational Intramedullary Nail. Jason Stoneback states he is the secretary for ISPO Special Interest Group for Bone-Anchored Limbs and is a board member for Justin Sports Medicine Team Annual Conference. He also reports stock with Validus Cellular Therapeutics. Jason Souza is a paid consultant for Balmoral Medical, LLC, Checkpoint, Inc, and Integrum, Inc. The remaining authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Members of the Global Collaborative Congress on Osseointegration (GCCO) are included in an Appendix at the end of the article.

Contributor Information

Matthew Wordsworth, Email: matthew.wordsworth981@mod.gov.uk.

Luke Juckett, Email: lkjuck15@gmail.com.

Jason M. Souza, Email: jason.souza@osumc.edu.

Global Collaborative Congress on Osseointegration (GCCO):

Joseph R. Hsu, Rachel B. Seymour, Benjamin K. Potter, Danielle Melton, Bailey V. Fearing, Leah Gitajn, Jason Hoellwarth, Robert Rozbruch, Jason Souza, Amber Stanley, Jason Stoneback, Meghan K. Wally, and Josh Wenke

References

- 1.Van De Meent H, Hopman MT, Frölke JP. Walking ability and quality of life in subjects with transfemoral amputation: a comparison of osseointegration with socket prostheses. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:2174–2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaffney BMM, Davis-Wilson HC, Christiansen CL, et al. Osseointegrated prostheses improve balance and balance confidence in individuals with unilateral transfemoral limb loss. Gait Posture. 2023;100:132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Örgel M, Elareibi M, Graulich T, et al. Osseoperception in transcutaneous osseointegrated prosthetic systems (TOPS) after transfemoral amputation: a prospective study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2023;143:603–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pospiech PT, Wendlandt R, Aschoff HH, et al. Quality of life of persons with transfemoral amputation: comparison of socket prostheses and osseointegrated prostheses. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2021;45:20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ranker A, Örgel M, Beck JP, et al. Transcutaneous osseointegrated prosthetic systems (TOPS) for transfemoral amputees: a six-year retrospective analysis of the latest prosthetic design in Germany. Rehabil Ger. 2020;59:357–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagberg K, Brånemark R, Gunterberg B, et al. Osseointegrated trans-femoral amputation prostheses: prospective results of general and condition-specific quality of life in 18 patients at 2-year follow-up. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2008;32:29–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagberg K, Häggström E, Uden M, et al. Socket versus bone-anchored trans-femoral prostheses: hip range of motion and sitting comfort. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2005;29:153–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juhnke DL, Beck JP, Jeyapalina S, et al. Fifteen years of experience with Integral-Leg-Prosthesis: cohort study of artificial limb attachment system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52:407–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunutsor SK, Gillatt D, Blom AW. Systematic review of the safety and efficacy of osseointegration prosthesis after limb amputation. Br J Surg. 2018;105:1731–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hebert JS, Rehani M, Stiegelmar R. Osseointegration for lower-limb amputation: a systematic review of clinical outcomes. JBJS Rev. 2017;5:e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atallah R, Leijendekkers RA, Hoogeboom TJ, et al. Complications of bone-anchored prostheses for individuals with an extremity amputation: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0201821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al Muderis M, Lu W, Tetsworth K, et al. Single-stage osseointegrated reconstruction and rehabilitation of lower limb amputees: the Osseointegration Group of Australia Accelerated Protocol-2 (OGAAP-2) for a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e013508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewallen EA, Riester SM, Bonin CA, et al. Biological strategies for improved osseointegration and osteoinduction of porous metal orthopedic implants. Tissue Eng B Rev. 2015;21:218–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Overmann AL, Aparicio C, Richards JT, et al. Orthopaedic osseointegration: implantology and future directions. J Orthop Res. 2020;38:1445–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang NV, Woollard A, Gupta S, et al. Enthesopathy, a cause for persistent peristomal pain after treatment with an osseointegrated bone-anchor: a retrospective case series. J Prosthetics Orthot. 2022;35:156–163. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atallah R, Reetz D, Verdonschot PhD N, et al. Clinical research have surgery and implant modifications been associated with reduction in soft tissue complications in transfemoral bone-anchored prostheses? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2023;48:1373–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Örgel M, Aschoff HH, Sedlacek L, et al. Twenty-four months of bacterial colonialization and infection rates in patients with transcutaneous osseointegrated prosthetic systems after lower limb amputation—a prospective analysis. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:1002211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]