Abstract

Purpose:

To explore factors associated with community garden use.

Approach:

Environmental assessment of community gardens and semi-structured interviews.

Setting:

New Orleans, Louisiana.

Participants:

10 community gardens (environmental assessment), 20 community members (including garden users and non-users) and garden administrators (qualitative interviews).

Method:

Gardens were assessed based on (1) accessibility, (2) information, (3) design, (4) cleanliness, (5) walkability, (6) parking, and (7) noise. Semi-structured interviews took place over Zoom; transcribed interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results:

Gardens assessed in the environmental assessment ranked high in design and cleanliness but low on accessibility and information availability. Salient themes from the qualitative interviews include skill-building, access to fresh foods, and increased social engagement as enablers of community garden participation, with availability of information and time as both potential enablers of, or barriers to, participation. Community members perceived that gardens could increase fresh food access, while administrators believed that it is not possible for community gardens to produce enough food to create community-wide impact, highlighting instead the importance of the social aspects of the garden as beneficial for health.

Conclusion:

Community gardens should improve garden physical accessibility and information availability to incentivize use. Community gardens are valued as means for skill-building and social engagement. Future research should prioritize investigating the association between the social aspects of participating in community gardens and health outcomes.

Keywords: community gardens, food access, new orleans, qualitative analysis, purpose

Purpose

Community gardens – defined as plots of land collectively gardened by a group of people – are heralded as structures that support multi-dimensional community success, relating to social, economic, and environmental well-being.1 Community garden participation has been linked to positive outcomes, including a higher intake of fruit and vegetables, improved overall fitness and mental health, a lower body mass index, and an increase in civic engagement, collective efficacy, social capital, and mutual trust.2–4 Some scholarship even recommends participation in community gardens as a “social prescription” to improve health outcomes.5 Community gardens are often mentioned as possible solutions for addressing food access issues in urban poor areas; however, their impact on food access is largely unknown. Notably, the potential nutrition benefits for urban poor areas could be offset by gardens’ role in the gentrification process,6 as well as their possible alienation of food insecure populations.7 Existing literature further emphasizes the role of the local community as a contributor to garden success, referencing inadequate community support and insufficient opportunities for engagement as important barriers.8

Though urban gardening has taken place in New Orleans for decades, the years following Hurricane Katrina saw the emergence of renewed interest in gardening as a tool for blighted property remediation, entrepreneurship, and redevelopment.6 By 2019, there were ~45 community gardens operating in the city.9 Current research about urban cultivation in New Orleans emphasizes the expansion of gardening as evidence of the local government’s bureaucratic approach to the leasing or purchasing of public lots,10 ultimately reflecting the city’s neoliberal demographic and economic transitions.6 However, this research focuses mainly on larger-scale entrepreneurial urban cultivation. Thus, information on smaller scale, community-based gardens and how they are currently perceived and used by individuals in the city is scant.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore factors associated with individuals’ usage of community gardens in New Orleans as the city recovers from yet another period of social and economic transition following the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our objectives were to conduct: (1) an environmental assessment of existing community gardens to identify physical attributes that may serve as enablers or barriers for use, and (2) qualitative interviews with community members and stakeholders to assess their perceived enablers and barriers of community garden use.

Design

We conducted environmental assessments of existing community gardens as well as semi-structured interviews with community members (community garden users and non-users) and community key stakeholders knowledgeable about community garden operations in New Orleans.

Participants

Participants were (1) community members living in the neighborhoods where community gardens were identified for environmental assessment, including community garden users and non-users, and (2) community gardens stakeholders, including people in leadership positions in the gardens identified for environmental assessment. Community members were recruited via door-to-door flyers, while stakeholders were contacted via email based on gardens’ publicly available information (i.e., through their websites or Facebook pages). The study was approved by the Tulane University Human Research Protection Office, Social and Behavioral Science Institutional Review Board (IRB# 2020–2156).

Methods

Data Collection

Environmental Assessment.

We used an ongoing randomized community trial focused on blighted property remediation in New Orleans11 as the backdrop for community garden selection. The aim of this randomized community trial – in which lots were greened and abandoned lots were cleaned – was to reduce community and youth violence in New Orleans.11 We conducted environmental assessments on all community gardens located in the low-income, high-violence neighborhoods where the randomized community trial was taking place (n = 6), plus all community gardens that participants of this randomized community trial reported patronizing (n = 9). In total, we assessed 15 community gardens located throughout the city. The environmental assessment was conducted with a tool developed by the research team based on previous research reporting on community garden assessments12,13 and on enablers/barriers of community garden use.8 This tool evaluated the following community garden characteristics: accessibility to the space, availability of information, spatial design, cleanliness, walkability around the garden, parking availability, and noise level (Table 1). We created this tool following an iterative process, testing it twice and independently by three team members in “test” (i.e., not part of the study) community gardens in New Orleans. After incorporating feedback, the final version of the environmental assessment tool was then used to evaluate the 15 community gardens which were part of the study. Environmental assessments were carried out by two team members using a tablet; the assessments took place in January-February 2021 during business hours. Photos of the gardens were taken during the assessments, which were then used by the other team members to confirm the scores given in all dimensions. Full agreement in community garden scoring was reached by all study team members.

Table 1.

Community Gardens’ Characteristics Evaluated in the Environmental Assessment, New Orleans, Louisiana.

| Category | Sub-category | Scoring | Explanation of Scores |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Accessibility | 9–10 (excellent) | No barriers to entering the property (e.g., no bars on doors or windows for properties with structures, extreme tall grass on vacant lots), may have fence but is open and one is able to enter freely | |

| 7–8 (good) | Minimal barriers to entering the property | ||

| 4–6 (fair) | Some barriers to entering the property | ||

| 1–3 (poor) | Property is not accessible (e.g., gate is locked) and will require assistance to enter | ||

| Information | Visible name of the organization | 0, 1 | 0 = no, 1 = yes |

| Sign-up sheet available | 0.1 | 0 = no, 1 = yes | |

| Informational signs and/or flyers available (with hours of operation, information on how to sign up, etc.) | 0.1 | 0 = no, 1 = yes | |

| Design | 9–10 (excellent) | Organized landscaping (e.g., raised beds, container gardening, flowers), sitting areas (e.g., benches, picnic tables) | |

| 7–8 (good) | Some organized landscaping, some sitting areas | ||

| 4–6 (fair) | Minimal organized landscaping, minimal sitting areas | ||

| 1–3 (poor) | No organized landscaping, no sitting areas | ||

| Cleanliness | Litter | 1–3 (excellent) | No signs of strewn liter, while looking inside the property |

| 4–6 (good) | Very little garbage, litter, broken glass, clothes, deceased animals etc. | ||

| 7–8 (fair) | Some garbage, litter, broken glass, deceased animalsetc. | ||

| 9–10 (poor) | Heavy garbage, litter, broken glass, deceased animalsetc. | ||

| Trash storage | 1–3 (excellent) | Properly stored garbage cans and trash in and around garden space | |

| 4–6 (good) | Little signs of improperly stored garbage1 and trash | ||

| 7–8 (fair) | Some garbage improperly stored in and around garden | ||

| 9–10 (poor) | Heavy garbage, improperly stored garbage in and around the garden | ||

| Walkability | Sidewalks visible | 0.1 | 0 = no, 1 = yes |

| Paved area | 0.1 | 0 = no, 1 = yes | |

| Walkways | 0.1 | 0 = no, 1 = yes | |

| Parking | Assigned parking | 0.1 | 0 = no, 1 = yes |

| Street parking | 0.1 | 0 = no, 1 = yes | |

| Noise | Next to heavily trafficked roadways2 or highways | 0.1 | 0 = no, 1 = yes |

Improperly stored garbage included any of the following: overflow of garbage in trash; no lids on the trash cans; signs of infestation of insects, flies or mosquitoes; pungent odor in the area due to trash being uncovered.

High traffic roadways defined as any highway or large arterial road: high-traffic (about 40,000 vehicles per day) and low-traffic (about 12,000 vehicles per day). Speed limits are typically between 30 and 50 mph or higher for highway or large arterial roads.

Semi-Structured Interviews.

To assess perceptions of enablers and barriers of community garden use in New Orleans, we conducted semi-structured interviews with community members and community key stakeholders. The goal was to recruit enough participants to reach theoretical saturation, usually estimated to be between 20 and 30.14 Door-to-door flyers were used to recruit community members. The research team distributed these flyers in the immediate blocks surrounding the 6 community gardens located in the randomized community trial neighborhoods. The flyers contained basic information about the study as well as a QR code, an email address, and a phone number so that interested residents could contact the study team and schedule an interview. As for community key stakeholders, people who held leadership positions in the 15 gardens identified for the environmental assessments were contacted via email and invited to participate in the study. Their contact information was obtained from public sources such as the community gardens’ websites or Facebook pages.

Community gardens were defined for participants as “a piece of land in which people collectively grow fruits and vegetables, which are then given to garden participants and/or community members for free or for a cost.” In addition, community garden participation was defined as gardening, getting food from the garden (for free or a fee), volunteering for the garden in different capacities, or any other level of engagement with the garden that participants might consider meaningful. Two sets of interview guides were developed for community members and community stakeholders, with a few distinctions for garden users vs. non-users within the community members group. Topics explored include individual/interpersonal experiences, community engagement, food access, placemaking, and future garden development. In addition, basic demographic information on participants were collected. Oral consent prior to interviews was sought. Given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, all interviews were carried out via Zoom, with a duration of 30–45 minutes. Interviews took place between April and July 2021. The interviews were audio and video recorded and transcribed verbatim by the research team. Once each interview transcription was completed and double-checked by a second team member, the interview recording was deleted. Participants were given a $25 gift card for a local fresh food delivery service.

Analysis Strategies

Data from the environmental assessment were summarized descriptively based on the following criteria, as detailed in Table 1: (1) Accessibility, (2) Information, (3) Design, (4) Cleanliness, (5) Walkability, (6) Parking, and (7) Noise.

As for the qualitative analysis, transcribed interviews were analyzed by two researcher team members independently, using thematic analysis15 with NVivo software, Release 1.4.1. Open coding was used to identify themes within transcripts to create the initial coding framework. The researchers cross-referenced each other’s work after manual coding until an overall unweighted kappa score – a measure of interrater reliability16 – of .69 was achieved, and then independently coded the rest of the interviews. Community members’ interviews were coded first. For community stakeholders, a modified codebook was used in which the researchers added codes that were more applicable to the administrative and leadership roles of garden stakeholders. Upon completion of coding, the researchers determined the most commonly used codes based on the number of files in which they appeared. A framework analysis—a comparative data tool to assess applications of these codes17 – was then used to produce themes that addressed the barriers and enablers to community garden participation.

Results

Environmental Assessment

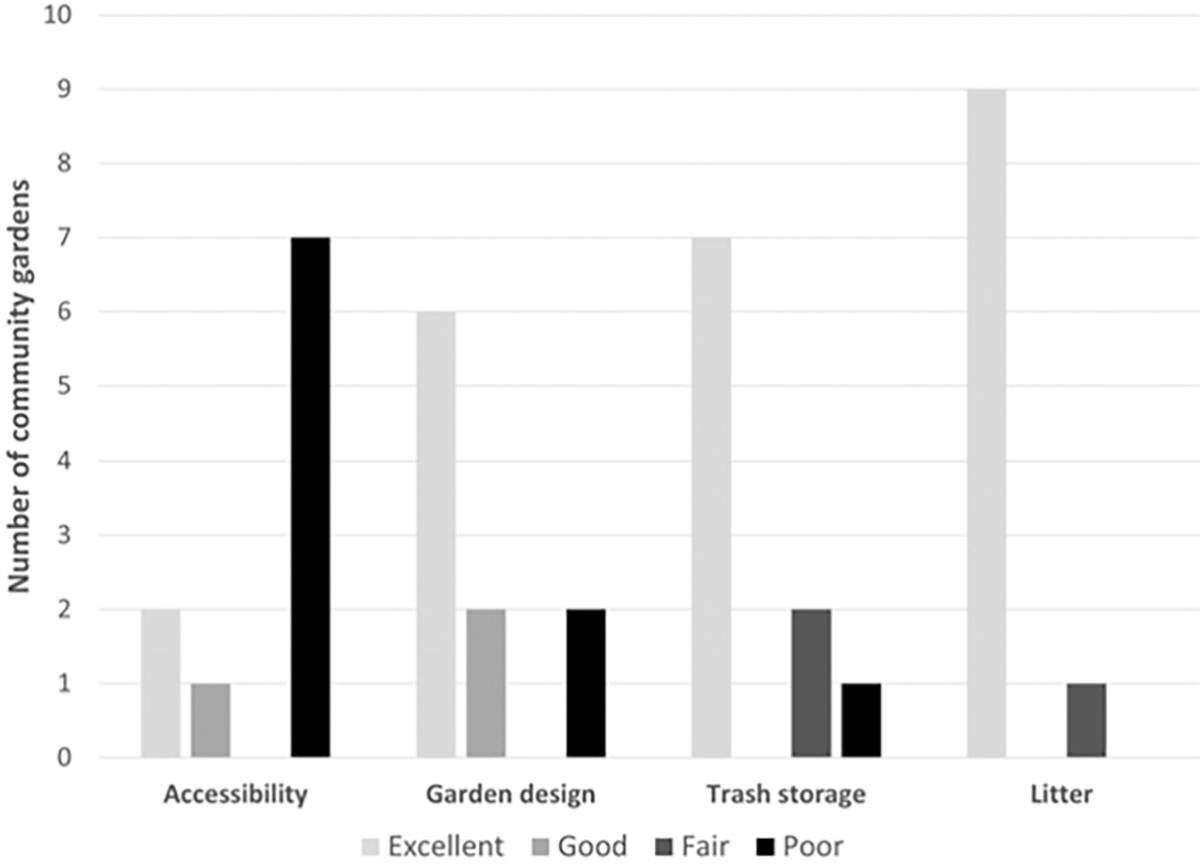

Of the 15 community gardens visited, 11 were in operation but one was physically inaccessible for assessment due to its tall gates. Thus, the results are based on the 10 community gardens which were in operation and accessible for assessment. Seven out of the 10 gardens had poor accessibility (Figure 1). In terms of availability of garden-related information, 60% of gardens had a visible name, 20% had informational signs or flyers, and 0% had sign-up sheets. As for design and cleanliness, most gardens (>60%) were rated as excellent (Figure 1). Most of the assessed gardens were considered walkable (6 out of 10 had sidewalks/paved areas), none had assigned parking, and 3 out of the 10 were close to heavily trafficked areas.

Figure 1.

Results of the community garden environmental assessment for the accessibility, design, and cleanliness (trash storage and litter) criteria (n = 10).

Qualitative Results

Approximately 1000 flyers were distributed to recruit community members. Twenty-four community members contacted the study team to get information about the study. From these, 10 declined to participate or stopped answering the study team’s contact efforts. Up to four follow-ups were attempted before dropping a participant from the study. A total of 14 community members were interviewed, four community garden users and 10 non-users. Further, 12 community garden stakeholders were contacted; stakeholders from the community gardens that were found to be closed in the environmental assessment were not contacted. Of these 12 stakeholders, two declined to participate, and 4 never responded, leaving 6 community garden stakeholders who were interviewed. Thus, our final sample size for qualitative analysis included 20 participants: 14 community members and 6 community garden stakeholders. The median age of the community member and the stakeholder samples was 40.5 and 33 years old, respectively. The breakdown of the self-identified racial identities of the community member sample was 39% White, 54% Black, and 7% Asian, with 21% identifying as male and 79% as female. In the stakeholder group, 71% were White, 14% Black, and 14% as Asian, with 57% identifying as female, 28% as male, and 14% as non-binary.

The themes identified in thematic analysis of the data include skill-building, availability of information, time, social engagement, and access to fresh foods. Below we provide the highlights of each theme; detailed explanations and example quotes can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Main Themes From Qualitative Interviews With Community Members and Community Garden Stakeholders in New Orleans, Louisiana, Regarding Enablers and Barriers of Community Garden Use (n = 20).

| Identified Theme | Theme Explanation | Number of Participants Discussing Theme | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Skill-building | Interviewees’ discussion of informal instances of skill building that contribute to their interest in garden participation | 4 out of 4 garden users | “The more I learn, the more of my interest will grow. And the more I keep my hands involved in it, the more I’ll learn, the more I can teach my children” – Community member, nonuser |

| 8 out of 10 garden non-users | “It’s nice because a lot of people from the neighborhood come... And so you can learn things about gardening while you’re there. And it’s just nice to meet different people. And everybody kind of comes together in the neighborhood.” – Community member, garden user | ||

| 4 out of 6 stakeholders | “Yeah, having more families involved, just bringing back a culture or a history of gardening.... When they see stuff growing, and they can taste stuff, and how much better it tastes. And they can learn like oh it grows on a tree, and it doesn’t just come from the grocery store.” – Stakeholder | ||

| Availability of information | Interviewees’ discussion of how the availability of information about garden activities affects their ability and likelihood of participation | 3 out of 4 garden users | “I mean, I’ve found most of them [community gardens] just by riding my bike by and going, |

| 7 out of 10 garden non-users | ‘Hey, what’s that over there?’ and I go up to it...I might get involved if there was a contact email or something. Yeah. But there isn’t. So I just have no idea.” – Community member, nonuser | ||

| 5 out of 6 stakeholders | “We always make sure that our nearby neighbors know about anything that’s pretty much going on. If it’s just something for the gardeners, I mean, we have a website, we put our information so people know of classes that are being offered... So, they do utilize Facebook and email systems and to send out that information of programs and each time, most times, it’s always fills up to capacity.” – Community member, garden user. “So perfection in this case does not exist, right. So I think the thing that will help us to reach our target will be to be to have more staff to do some more outreach and, and to talk about our garden” – Stakeholder | ||

| Time | Interviewees’ discussion on how time limits their ability to participate in community gardens | 3 out of 4 garden users | “...There is actually a community garden three blocks from my house and it is gorgeous. I’ve always wanted to volunteer there, but I never made the time.” – Community member, nonuser |

| 7 out of 10 garden non-users | “A lot of people want to garden, they think they want to garden. But when they realize how much time and effort and dedication it takes... A Lot of them stop...” – Community member, garden user | ||

| 2 out of 6 stakeholders | “I think the big thing it would require is that more people had more time in their life which is a like a political and economic critique for sure. Right like people can’t engage with community gardening if they so choose, because a lot of people don’t have that literal space in their life, cause they’re working,... I Guess I’m just saying it requires like an overhaul of the American like work week.” – Stakeholder | ||

| Social engagement | Interviewees’ discussion of norms, values and practices that characterize engagement within and with community gardens as well as interpersonal relationships as a factor of participation | 4 out of 4 garden users | “Maybe it’s the community part that people would really want to be a part of, not so much the gardening... I Mean gardening together is better than gardening alone” – Community member, nonuser |

| 10 out of 10 garden non-users | “Just that it is respectful of everybody, everybody, we don’t make decisions at that garden. It’s not a hierarchy or anything like that, it’s... Everybody makes the decision. Every member of the garden is invited to participate in meetings before any decisions are made. And we all vote and come together collectively to decide what’s going to happen next.” – Community member, garden user | ||

| 6 out of 6 stakeholders | “... one of my really strongly held beliefs about a community garden is that they do... they require someone who has an extra level of dedication to make them tick and I think that’s like counter to how a lot of people conceive of community gardens, they’re like this should just be like super easy and people should come in, and I think that’s the point of like food, like food being inaccessible and expensive under capitalism is that, like we don’t pay-we don’t appropriately value labor, we don’t appropriately value the people who are moving our food systems forward. And to keep a community garden healthy and strong, we need to pay for the labor of organizing community gardens.” – Stakeholder | ||

| Access to fresh foods | Interviewees’ discussion of the availability of fresh produce as a factor related to participating in/purchasing from community gardens | 4 out of 4 garden users | “I mean, making, I mean, it totally makes sense to, you know, use land around us to provide food within neighborhoods, especially for people who don’t have access to healthy food, educating the youth, programs for youth and seniors to get access to healthy, you know them and their families to get access to healthy food.” - community member, garden nonuser |

| 10 out of 10 garden non-users | “You know, especially because there’s a lot of like food desert areas in new Orleans. And there’s a lot of people who don’t have cars in new Orleans too including myself, like, you know, and you don’t really have access to big grocery stores that are close. I mean, if you had a garden in your neighborhood, it might increase the amount of like, vegetables and stuff that you’d eat. Because they’re right there. You know, you have them in hand.” - community member, garden user | ||

| 5 out of 6 stakeholders | “I don’t think small lot gardening is effective for meeting people’s food security needs in my experience at all. I Think that backyard gardening has a lot of interesting, um, applications but in terms of on a on a lot or a couple of small lots, producing enough food to impact food insecurity is that we’re talking about? No, is the answer to that as far as I’m concerned.” - stakeholder | ||

Skill-Building as Incentive for Garden Participation.

Skill-building was mentioned as a reason for garden participation by all current garden users and as a reason for potential participation by 8 of the 10 non-users. We used skill-building as a code in instances where participants described the “appeal of gardening as a pathway to developing new skills or abilities.” Users and non-users generally referred to skill-building opportunities for children as an incentive to their personal or hypothetical participation.

Common sentiments primarily among non-users included the desire to take care of entities outside of themselves and the interest in sharing knowledge with other people. Helping others build skills and acquire knowledge was a reflection that was also prominent among stakeholders when discussing their reasons for involvement in community gardens (4 out of 6). Non-users also cited lack of skills as a reason for their current failure to participate in a garden. On the other hand, among users, skill-building was described as being connected to the social aspect of the garden—i.e., instructing or consulting with other users—and as an incentive to community participation in gardens’ educational programming.

Availability of Information Limiting Garden Familiarity and Participation.

Availability of information about garden hours, eligibility, and other activities was mentioned by 7/10 non-users and 3/4 users as contributing to the likelihood of their garden participation. The ease (or lack thereof) with which individuals can access this information was also emphasized as a potential barrier. Among non-users who mentioned access to information as impeding their participation, specific barriers included lack of knowledge about who to contact and inability to locate information materials, neither physically nor online. Users, in contrast, generally described focused efforts to spread information about the gardens in which they participate by disseminating flyers, hosting events, and using social media. Still, they emphasized the need for the continued spread of information about gardens. Information was mentioned by 5 out of 6 stakeholders, mainly as a response to questions about barriers and opportunities to increase participation.

Time as a Constraint to Participate in Community Gardening.

Among garden users, 3/4 mentioned lack of time as hindering participation in community gardens. A similar proportion (7/10) of garden non-users mentioned time as limiting their ability to participate despite they wanting to. For some non-users, increased amount of available time due to COVID-19 related unemployment increased willingness to participate in community gardens. Users frequently mentioned that those seeking to garden often underestimate the amount of time involved; they held this as true for themselves and for those who they have seen participate and later abandon garden plots. Similarly, the stakeholders that mentioned time as a barrier (2/6) held that it is an underestimated factor for those seeking to garden as well as those seeking to build gardens.

Social Engagement With Community Gardens.

The social engagement theme refers to the various interpersonal interactions, organizational norms, and values influencing participation or support of community gardens among participants. Within this theme, two sub-themes were identified: relationships and community dynamics.

The sub-theme of relationships identifies the quality of interpersonal relations as an influential positive enabler of initiation and continuation in community garden participation. Among users and stakeholders, relationships enjoyed through gardening were described as fulfilling and as motivation for continued engagement in community garden spaces. Multiple gardeners mentioned coming to the realization that social interactions became the driving factor – not necessarily growing food – for their continued participation in community gardens. Half of garden non-users also mentioned relationships as a motivation for desiring to participate in a community garden. Relationships were also mentioned as means of increasing the accessibility of food that community gardens offer and, among stakeholders from currently operating gardens, building intentional relationships with community members was mentioned alongside or as a standalone factor for encouraging and maintaining engagement with community gardens. Stakeholders who reported struggling, not prioritizing, or being unable to form meaningful relationships with community members were met with disengagement with garden projects despite spreading information about garden services in areas that would presumably benefit from the increased food access that gardens may offer.

The community dynamics sub-theme explores norms, values, and practices which characterize engagement within community gardens among users and stakeholders and with community gardens among non-users. Users and stakeholders had a common appreciation of norms centering non-hierarchy, democracy, and sociality. These norms were reflected in practices of adopting some level of communal ownership of beds, shared decision making, attention to and appropriate valuing of the contribution and commitment of others, social events open to the wider community, and awareness of how their garden forms part of and shapes larger social and economic dynamics in their neighborhood. Communal ownership allowed for more variable level of engagement as gardens could be worked on by volunteers or gardeners with limited individual-time commitments, while reducing plot abandonment typical among individual plot ownership systems. Food grown in communal plots is likewise available to all who helped grow it and often to all members in the community regardless of their participation. Shared decision-making and responsibilities encouraged participation beyond the management of an individual plot and helped shape community belonging among gardeners. Shared responsibilities reduce workload while also serving as a means of skill building as people stepped into roles and tasks where they had to learn to perform effectively. Social events also helped to increase the sense of belonging central to communities and, at least for public events, spread awareness of gardens’ existence among the wider community. Stakeholders aware of larger social and economic dynamics in their neighborhood and their own position within them reported being better able to adapt their practices to fit the community. Such adaptions included not only knowing which foods would be culturally appropriate to grow, but also for whom available individual plots should be prioritized, and if/how much to charge for produce.

Since non-users do not currently participate in gardens, perspectives on garden norms and practices were limited. Though some non-users had limited ability or willingness to participate in community gardens, nearly all non-users valued supporting gardens through purchasing foods or other available means. For them, community gardens were meaningful contributions to neighborhoods and their support of gardens was framed as a satisfying feeling of giving back to the community or supporting local economies.

Community Gardens’ Role in Addressing Food Access Issues.

“Access to fresh foods” was used as a code to assess community members’ perceptions of the gardens’ impact on food access and was invoked in all 14 community member interviews. Four interviewees —two users and two non-users—explicitly mentioned “food deserts” as a challenge in New Orleans and reported their belief that community gardens could help alleviate this lack of access to fresh foods. Other interviewees used different language to express similar concerns about the dearth of fresh foods in the city and expressed hopes that community gardens could have a positive impact on this issue.

In contrast, stakeholders focused on the small-scale production of community gardens and their hyper-local impact. They mentioned increased food access as an inherent benefit of community gardens, but they also emphasized the inability for gardens to “ever replace the industrialized food system” or “produce enough food to impact food insecurity,” because of the labor, funding, and infrastructural challenges that factor into garden upkeep. Yet, while all stakeholders brought up some sort of operational barrier, one of them mentioned that infrastructure and labor challenges ultimately outweighed the benefits of the garden and thus led to its closure. Increased funding was brought up repeatedly as a potential antidote to operational issues.

Conclusion

The goal of this study was to identify enablers and barriers of community garden use in New Orleans, Louisiana by conducting an environmental assessment of existing gardens and qualitative interviews with community members – including garden users and non-users – and community garden stakeholders. Most of the community gardens assessed ranked high in design and cleanliness, but low on physical accessibility and information availability. Salient themes from the qualitative interviews include skill-building, access to fresh foods, and increased social engagement as enablers of community garden participation, with availability of information and time as both potential enablers (if available) or barriers (if not available) of participation.

The best scores in the gardens’ environmental assessment were in reference to design (80% rated as good or excellent) and cleanliness (90% rated as excellent). While a few participants mentioned “aesthetics” in the qualitative interviews in relation to their appreciation of having gardens in their communities, this code was not one of the most salient. In other words, while having access to areas that are aesthetically pleasant may be important in the use of public spaces,13 our study did not find aesthetics to be a key enabler of community garden use.

Availability of information about gardens’ activities, hours of operation, and how to participate was mentioned as an important determinant of garden participation by community members. Our environmental assessment found that, while 60% of gardens had a visible name displayed, only 20% had informational flyers and none had sign-up sheets. Having a name visibly displayed could prompt a web search by potential users; however, interviewed community members reported that information was often not easily accessible in person, nor online. Moreover, 70% of the assessed gardens were classified as having poor accessibility in the environmental assessments, as most had locked gates; this lack of accessibility could prevent potential participants from entering the garden and asking questions, in the case of staff or volunteers being present. It is important to note, though, that garden assessment took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have affected normal garden operations, including accessibility and the presence of staff/volunteers.

In terms of skill-building, community members mentioned their interest in learning new skills as reasons for garden participation (or potential participation, for garden non-users). Garden non-users also mentioned lack of skills as impeding their participation, while users and stakeholders expressed their appreciation to be able to teach skills to others. This interest in skill-building is consistent with Guitart et al’s1 systematic review on global community garden usage, where 23 of the 87 evaluated studies emphasized education as a key motivation for garden participation. This research also looked at the demonstrated benefits of community gardens in the available literature, and education was one of the most commonly discussed benefits, included in 29 of the 87 studies.1

Time was another important factor mentioned by both community members and stakeholders. While community members discussed time limitations as a barrier to participation (or to increased participation, in the case of garden users), stakeholders emphasized the amount of time – and effort – that it takes to establish and run a community garden. Based on a panel of 53 community garden experts throughout Florida, and applying the Delphi technique for consensus building, Diaz et al.8 reported time as one of four main barriers to community garden success. Interestingly, the time component reported among the garden experts interviewed by Diaz et al.8 – equivalent to the stakeholders interviewed in the current study – was in reference to not having enough time for community engagement, as opposed to our study’s findings regarding time needed to build and run the garden. In addition, Diaz et al.8 report that another of the four main barriers agreed upon by the expert panel was having inadequate community support. This relates to our finding of the relationship between social engagement and community garden participation, for community members and stakeholders alike. Participants in our study highlighted the importance of relationship building and community engagement as drivers of their participation and/or support for community gardens. This has vast support in the literature, with community garden participation linked to increased civic engagement, social capital, and mutual trust.1,2,18 Likewise, stakeholders in our sample mentioned that failure to form or maintain community relationships was detrimental to the gardens’ success because that led to community disengagement.

Because stakeholders are privy to operational challenges that might not be obvious to community members – including issues building infrastructure and securing labor and funding – community members and stakeholders expressed differing perceptions of the potential role played by community gardens in increasing access to fresh foods. The community members’ perception is that gardens can increase access to fresh foods, while stakeholder perspectives seem to indicate that the community aspect – rather than the garden aspect – positively impacts community health. Stakeholders expressed that it is not possible for community gardens to produce enough food to sustain the whole community; rather, the food produced in the garden is viewed by stakeholders as secondary to the importance of community building that happens in garden settings. As food grown in community gardens can only be distributed to a limited number of people, and building and maintaining gardens is operationally difficult, community gardens are not a reliable way to increase food access, based on stakeholders’ perspectives.

In their systematic review, Burt et al.18 found that 18 of the 31 studies evaluated reported dietary outcomes as related to community garden participation, including fruit and vegetable intake, food quality, food security, and access to produce. All the studies that measured fruit and vegetable intake and access to produce reported positive outcomes; however, given study design limitations – including the use of self-reports and non-validated dietary measures – Burt et al.18 concluded that there is no evidence of a causal relationship between community garden participation and improved diet. Relatedly, Kato et al.10 reported on operational challenges faced by urban growers in New Orleans in terms of accessing growing lots; challenges reported by the 44 interviewed urban growers included bureaucratic application processes and changing policy landscapes for leasing or purchasing public lots. In addition, growers reported concerns finding quality lots, in reference to water access, contamination, and safety of surrounding areas.19 Diaz et al.8 reported similar challenges related to gaining access to appropriate land in their study among gardeners in Florida. In sum, while community gardens may improve participants’ diet via increased fresh produce consumption,18 the benefits for the community at large in terms of increased access to enough food to improve food security status is not supported by our results nor by the literature.18,19 On the other hand, there is evidence that community gardens may accelerate the gentrification process6 and, thus, negatively affect low-income neighborhoods which would theoretically benefit from the presence of community gardens the most.7 Thus, any benefit community gardens may serve as an intervention for increasing social connections, for example, should be carefully weighed alongside these concerns.

Strengths of this study include its multi-method approach, combining results from an environmental assessment of gardens in the city and qualitative interviews with community members and community garden stakeholders. The inclusion of community members’ and stakeholders’ perspectives is also a strength, as both groups provided different perspectives regarding enablers and barriers of community garden use. Moreover, our inclusion of community garden non-users is innovative, as their voices have rarely been part of the community garden dialogue. Limitations include the potentially limited transferability of our study results given the place-based nature of the study. In addition, while our sample size of 20 participants is within the suggested limit to reach theoretical saturation,14 given that we interviewed more than one type of participant (community members vs. stakeholders), theoretical saturation may have not been achieved. Finally, while we considered the perceptions of all community members – regardless of garden participation – as valuable, garden non-users could only comment on community gardens in a hypothetical manner, which may be particularly affected by social desirability bias.

In conclusion, this study found that while community gardens in the city of New Orleans were aesthetically appealing and clean, they were not necessarily accessible, with physical and informational barriers present. Important enablers of community garden use as reported by community members and garden managers include the opportunity to learn new skills and become engaged with the community, with lack of information and time being key barriers. While community members believed community gardens could address food access issues in their communities, those who managed gardens disagreed, suggesting that community gardens will never produce enough food to truly impact community food security. However, they emphasized the community engagement value of gardens, which has been shown to positively impact health. Future research should thus prioritize investigating the link between the social aspects of participating in community gardens and health outcomes.

So What?

What is already known on this topic?

Community garden participation has been linked to positive health outcomes, including a higher intake of fruit and vegetables and improved fitness and mental health.

What does this article add?

Salient themes from interviews with community garden users, non-users, and administrators in New Orleans, LA include skill-building and increased social engagement as enablers of garden participation, with availability of information and time as both potential enablers and barriers. For community members, community gardens could increase fresh food access, while administrators believed that community gardens cannot produce enough food to impact community food security.

What are the implications for health promotion practice or research?

Health promotion researchers should focus on inves- tigating the association between the social aspects of community garden participation, as opposed to the food provision aspects, and health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the staff of the Healthy Neighborhoods Project for their assistance with study design, as well as study participants who generously shared their time and insights with us.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Carol Lavin Bernick Faculty Grant, Tulane Office of the Provost, and the Healthy Neighborhoods Project parent study (NIH R01HD095609 and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, RWJF grant # 76131).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Tulane University Human Research Protection Office, Social and Behavioral Science Institutional Review Board (IRB# 2020–2156).

References

- 1.Guitart D, Pickering C, Bryne J. Past and future directions in community gardens research. Urban For Urban Green. 2012;11(4):364–373. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Delaimy WK, Webb M. Community gardens as environmental health interventions: Benefits versus potential risks. Current Environmental Health Reports. 2017;4:252–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egli V, Oliver M, Tautolo E. The development of a model of community garden benefits to wellbeing. Preventive Medicine Reports. 2016;3:348–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Draper C, Freedmand D. Review and analysis of the benefits, purposes, and motivations associated with community gardening in the United States. J Community Pract. 2010;18:458–492. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howarth M, Brettle A, Hardman M, Maden M. What is the evidence for the impact of gardens and gardening on health and well-being: A scoping review and evidence-based logic model to guide healthcare strategy decision making on the use of gardening approaches as a social prescription. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e036923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kato Y. Gardening in times of urban transitions: Emergence of entrepreneurial cultivation in post-Katrina New Orleans. City Community. 2020;19(4):987–1010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butterfield KL, Ramirez AS. Framing food access: Do community gardens inadvertently reproduce inequality? Health Educ Behav. 2021;48:160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diaz JM, Webb ST, Warner LA, Monaghan P. Barriers to community garden success: Demonstrating framework for expert consensus to inform policy and practice. Urban For Urban Green. 2018;31:197–203. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Go Green Nola (2017–2018). Community Gardens. http://www.gogreennola.org/communitygardens/

- 10.Kato Y, Andrews S, Irwin C. Availability and accessibility of vacant lots for urban cultivation in post-Katrina New Orleans. Urban Aff Rev. 2018;54(2):332–362. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Healthy Neighborhoods Project. Healthy Neighborhoods Project; n.d. https://www.healthyneighborhoodsproject.com/

- 12.Wesener A, Fox-Kämper R, Sondermann M, Münderlein D. Placemaking in Action: Factors That Support or Obstruct the Development of Urban Community Gardens. Sustainability. 2020;12(2):657. doi: 10.3390/su12020657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Root ED, Silbernagel K, Litt JS. Unpacking healthy landscapes: Empirical assessment of neighborhood aesthetic ratings in an urban setting. Landsc Urban Plann. 2017;168:38–47. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rijnsoever FJ. I can’t get no) saturation: a simulation and guidelines for sample sizes in qualitative research. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banerjee M, Capozzoli M, McSweeney L, Sinha D. Beyond kappa: A review of interrater agreement measures. Can J Stat. 1999;27(1):3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldsmith L. Using framework analysis in applied qualitative research. Qual Rep. 2021;26(6):2061–2076. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burt KG, Mayer G, Paul R. A systematic, mixed studies review of the outcomes of community garden participation related to food justice. Local Environ. 2021;26(1):17–42. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegner A, Sowerwine J, Acey C. Does urban agriculture improve food security? Examining the nexus of food access and distribution of urban produced foods in the United States: A systematic review. Sustainability. 2018;10:2988. [Google Scholar]