Abstract

This paper reports on two cases of post-traumatic osteomyelitis (OM) caused by Aeromonas hydrophila in immunocompetent patients, a rare but severe condition. A. hydrophila, a gram-negative bacterium typically found in aquatic environments, is seldom reported as a cause of OM. The first case involved a 42-year-old male with a Gustilo-Anderson grade II open tibial fracture exposed to sewer water, leading to persistent infection despite initial treatment. The second case described a 38-year-old male inmate with a gunshot-induced tibial fracture managed externally, later presenting with purulent discharge and bone exposure. Both cases required extensive surgical interventions, including multiple debridements, antibiotic therapy, and bone reconstruction using distraction osteogenesis techniques. This report emphasizes the importance of early suspicion of A. hydrophila infection in patients with open fractures and water exposure, noting that standard laboratory procedures may not routinely identify this pathogen. Effective management involves a combination of surgical and medical approaches, including targeted antibiotics and aggressive surgical debridement, with some cases necessitating amputation. The rarity of this infection and its challenging treatment underscore the need for further research to develop standardized protocols and improve clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Aeromonas hydrophila, Osteomyelitis, Open fracture, Long bone defect

Introduction

Aeromonas hydrophila (A. hydrophila) is a gram-negative heterotrophic eubacterium that primarily thrives in warm climates, especially in freshwaters, although it can also survive in both aerobic and anaerobic environments. It was isolated in humans and animals in the 1950s and is the most well-known of the six species within the genus Aeromonas, presenting a prevalence of up to 60 % among Aeromonas species in soft tissue infections [1].

In humans, bacteria of the Aeromonas genus are primarily known for causing gastrointestinal infections, with some advanced cases of peritonitis, colitis, and cholangitis being described (Table 1). Secondly, they are associated with soft tissue infections [2]. Osteomyelitis (OM) caused by A. hydrophila in healthy hosts is rare. Since the first reported case in 1975, there have been 10 case reports including 13 patients in the reviewed literature, making it a rare entity [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]].

Table 1.

Case reports of post-traumatic osteomyelitis (OM) by A. hydrophila in immunocompetent patients.

| Author | Date | Site of OM | Water exposure | Bone resection | Bone/limb reconstruction | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stephen et al. [3] | 1975 | Tibia | Ocean | – | – | Not reported |

| Blatz [4] | 1979 | Tibia | Stagnant pool water | – | – | Amputation |

| Weinstock et al. [5] | 1982 | Foot | Lake | – | – | Resolved |

| Karam et al. [6] | 1983 | Ankle | River | – | – | Resolved |

| Calcaneus | Lake | Partial resection of calcaneus | – | Resolved | ||

| Dubey et al. [7] | 1988 | Forearm | Not reported | – | – | Chronic OM |

| Bonatus and Alexander [8] | 1990 | Tibia | River | – | Bone graft/free gracilis flap | Resolved |

| Femur | – | – | – | Resolved | ||

| Gold and Salit [9] | 1993 | Tibia | – | – | – | Resolved |

| Tibia | River or ocean | – | – | Resolved | ||

| Gunasekaran et al. [10] | 2009 | Foot | Sewer | Partial resection of metatarsal | – | Resolved |

| Agrawal et al. [11] | 2017 | Tibia | – | – | – | Resolved |

| Tsunoda et al. [12] | 2022 | Tibia | River | Partial resection of tibia | Bone transport/sural flap | Resolved |

| Present report | 2023 | Tibia | Sewer | Partial resection of tibia | Bone transport-lengthening/hemisoleus flap | Resolved |

| Tibia | – | Partial resection of tibia | Bone transport | Resolved |

Adapted from Tsunoda et al. [2].

It primarily affects the extremities, following contact with contaminated water in a traumatic event [13]. A significant number of these infections were reported among survivors of the tsunami in Thailand in December 2004 and during Hurricane Katrina in 2005. It is more frequent in men than in women, with a ratio of 3:1 [14].

Its pathogenesis is multifactorial and associated with various virulence factors. It acts through the release of aerolysin toxin, which causes tissue damage upon contact with the lesion. The bacterium also produces hemolysins with necrotizing activity, leading to muscle liquefaction, potentially affecting the bone and causing infection [3]. Systemic manifestations may include general malaise and fever, along with edema, erythema, and local warmth at the infection site. Laboratory findings may reveal leukocytosis, neutrophilia, and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) [2].

The most common clinical manifestation is cellulitis; however, patients may develop abscesses that extend through the fascia, leading to subsequent cases of myonecrosis, ecthyma gangrenosum, OM, and in severe cases, limb loss, septic shock, and even death [1].

Diagnosis is made by bacterial isolation in culture media. A. hydrophila grows readily on blood agar, chocolate agar, or MacConkey agar. Cultures and antibiograms should be obtained from all affected tissues, including bone. Once the diagnosis is confirmed by bacterial isolation, appropriate antibiotic treatment should be instituted based on the identified resistance pattern [14].

Initial treatment consists of combined antibiotic therapy with third-generation cephalosporins and an aminoglycoside. For patients allergic to cephalosporins, quinolones are a good alternative. Although the use of carbapenems is described, there are reports of resistance to this antibiotic. Comprehensive treatment includes surgical lavage and debridement; however, when the infection focus cannot be controlled, extensive bone resections or even limb amputation may be necessary [14].

This article reports our experience with two cases of OM caused by A. hydrophila in immunocompetent patients, highlighting the management challenges and multiple surgical procedures required to control the infection focus. The importance of early identification of this pathogen is emphasized to reduce the risk of dramatic local evolution. The first case involves an open fracture with exposure to contaminated water, and the second a late infection in an implant. In both cases, antibiotics sensitive to Aeromonas were required, and due to the large secondary bone defects, reconstructive procedures were necessary.

Case 1

A 42-year-old male patient suffered a motorcycle accident as a passenger, presenting with a Gustilo & Anderson (G&A) grade II open fracture of the left tibial diaphysis, Weber A fibular malleolus fracture, and tarsal scaphoid fracture (Fig. 1), with exposure to sewer water at the time of the trauma.

Fig. 1.

Gustilo-Anderson Grade II diaphyseal fracture of the left tibia, with a 2 × 2 cm wound at the junction of the middle and distal thirds.

Initially, the patient was managed with wound and open fracture lavage and debridement, followed by intramedullary nailing of the left tibia, achieving adequate reduction, fixation, and primary wound closure. Two weeks later, he presented to the outpatient clinic with fetid discharge at the wound site, leukocytosis, and neutrophilia. Therefore, a new lavage and debridement were performed, retaining the material, and cultures were taken, reporting the isolation of A. hydrophila. An infectious disease consultation was requested, and management with intravenous ciprofloxacin 400 mg every 12 h for 8 weeks was indicated, due to a history of penicillin allergy.

Due to the poor response to this treatment, it was decided, in a multidisciplinary meeting with the infectious disease service, to escalate management to meropenem and perform a new procedure for lavage, debridement, and removal of the osteosynthesis material, also performing reaming with the RIA system (Reamer Irrigation Aspiration, DePuy Synthes), and local application of antibiotic beads. In subsequent procedures and new cultures performed, persistence of the microorganism was identified, and additionally, Escherichia coli multisensitive and Candida auris were isolated. Consequently, a 10 cm hemidiafisectomy of the tibia was performed to control the focus, including all the deperiostized bone without positive Paprika sign. Temporary fixation was performed with a trauma external fixator, later converted to a circular Ilizarov external fixator for more stable fixation and with the plan to perform bone transport.

Secondary to the various surgical procedures, the patient presented three coverage defects: one between the middle and distal thirds of the leg with a 6 cm diameter, the second in the medial malleolar region with a 7 cm diameter and exposure of the anterior tibial tendon, and the third in the lateral heel region with a 1 cm diameter.

Once the infection focus was controlled after multiple procedures, negative cultures, and intravenous antibiotic therapy, the patient underwent coverage of the defects by the plastic surgery team, using a local hemisoleus muscle flap and skin grafts. Subsequently, after definitive coverage, a corticotomy was performed, and bone transport was initiated for the tibial defect.

During the transport process, several complications arose, such as invagination of the flap into the bone defect, requiring a new procedure by plastic surgery; in the same procedure, acute shortening was performed, changing the transport frame configuration to lengthening until the planned length was restored. Six months later, due to pain and intolerance to the Ilizarov fixator, a new intervention was performed to change the circular fixator to a monolateral fixator to protect the regenerate, and osteotomy of the docking site was performed with the application of bioactive glass bone graft plus Putty due to lack of consolidation progress (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

A. Initial management with intramedullary nailing (IMN). B. Two-week course with purulent discharge. C. Removal of intramedullary nail, Reaming Irrigation Aspiration (RIA) + insertion of antibiotic-loaded beads. D. Hemidiaphysectomy of the affected segment. E. Application of an Ilizarov-type external fixator for bone transport. F. Correction of flap invagination on the anterior aspect of the leg. G. Repositioning of the external fixator for bone lengthening. H. Outcome of the bone lengthening procedure.

Currently, the patient has achieved full consolidation of the docking site, as confirmed by radiographic images, with advanced maturation of the bone regenerate at the transport site. The patient is now able to bear full weight on the affected limb. Furthermore, the soft tissue injuries are in good condition, with healed wounds and no clinical or laboratory signs of infection, as verified through hemogram and C-reactive protein monitoring (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

A-B. X-rays showing complete consolidation of the docking site. C-D. X-rays showing the maturation process of the bone regenerate, demonstrating good formation of the lateral and anterior cortices, with the posterior cortex still in progress. E. Clinical image of the patient with full weight-bearing. F. Clinical image of the soft tissues of the reconstructed limb.

Given the patient's current clinical status, the plan includes regular follow-up to monitor the progression of the regenerate maturation and ensure full functional recovery. Recommendations also include physiotherapy to improve range of motion, strength, and overall functionality, as well as periodic imaging to confirm the complete integration and remodeling of the bone regenerate. The patient has been educated about the potential long-term risks, such as recurrence of infection and advised to promptly report any signs of complications.

Case 2

A 38-year-old male inmate was referred to our institution with a history of an open diaphyseal tibial fracture resulting from a gunshot wound, which had been managed externally with open reduction and internal fixation using a plate (Fig. 4).

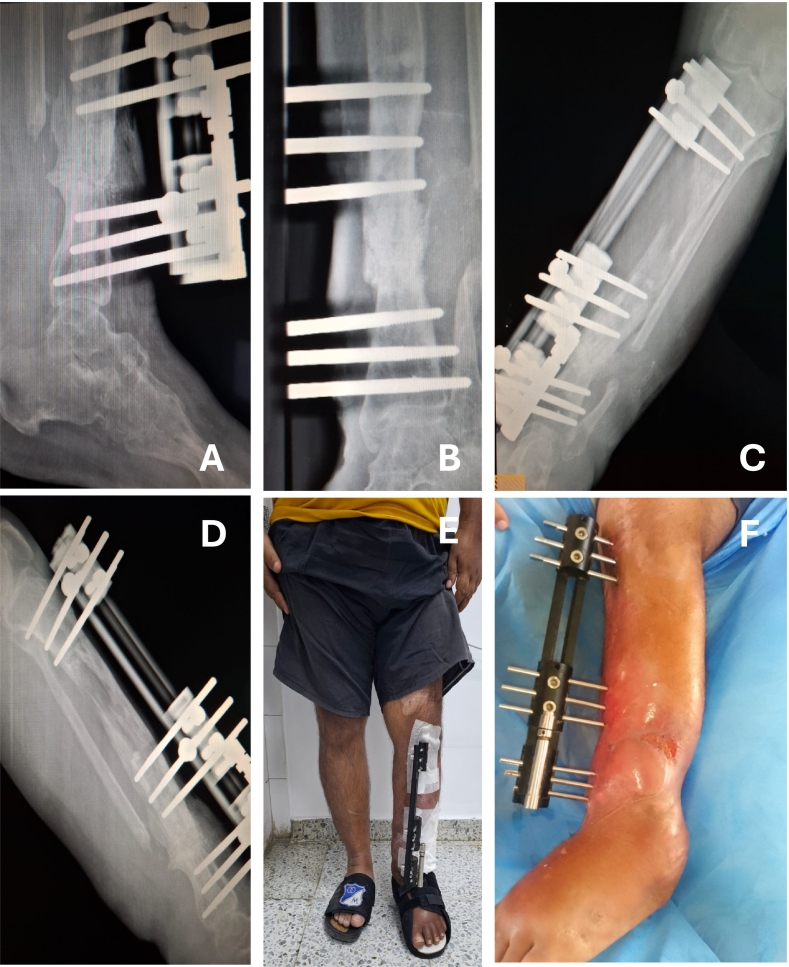

Fig. 4.

Exposure of plate in the tibia and loosening of the osteosynthesis material.

He presented to our hospital with a two-month history of purulent discharge from the surgical wound and intermittent febrile episodes. On admission, exposure of the osteosynthesis material, friable tissue, and purulent discharge were evident. Laboratory tests on admission showed no leukocytosis and negative acute phase reactants (Leukocytes 6.83, CRP 9.44, ESR 7). He underwent surgical lavage and debridement with removal of the osteosynthesis material. Purulent discharge through the canal and instability of the focus due to non-union were observed. The anterior cortical bone of the tibia was found to be devitalized in the middle third, necessitating resection and sampling for culture from the anterior tibial cortex. Empirical antibiotic therapy was initiated with cefazolin, later switched to oxacillin, doxycycline, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for 10 weeks due to the isolation of A. hydrophila and macrolide- and lincosamide-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

These findings prompted an MRI study to assess the extent of bone involvement, leading to a plan for segmental resection and endomedullary reaming with the RIA system (Reamer Irrigation Aspiration, DePuy Synthes), and placement of an antibiotic-impregnated cement spacer (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

A. X-ray and CT scan after plate removal. B. Hemidiaphysectomy and application of a cement spacer. C. Ilizarov external fixator for bone transport with bifocal corticotomy. D. Ongoing reconstruction process.

In a subsequent surgical procedure, the hemidiafisectomy was increased and the cement spacer was replaced, resulting in an approximately 11 cm bone defect in the middle third of the tibia. A plan was made for reconstruction using a bone transport device.

In later procedures, the cement spacer was removed, corticotomy was performed, distraction osteogenesis was initiated, and new cultures were taken, which were negative. The patient was discharged with outpatient antibiotic therapy for a total of 12 weeks and wound care at the wound clinic every third day.

As a complication, there was angulation of the Schanz screw in the proximal ring of the fixator, causing intense pain that halted the transport process for approximately 6 weeks until he sought emergency care. The Schanz screw was replaced and a new corticotomy was performed, allowing bone transport to resume.

The patient is currently awaiting removal of the external fixator. Unfortunately, follow-up care has not been possible due to the patient's incarceration in the national penitentiary system, where medical management has been transferred to the prison healthcare services. According to information provided by the patient's family, he has achieved full weight-bearing and is free of pain. The final stage of external fixator removal, along with any subsequent rehabilitation or management of potential complications, is now under the care of the penitentiary healthcare system.

Discussion

This report contributes to the literature with two cases of this rare and challenging entity, highlighting key aspects for early suspicion that may help prevent catastrophic outcomes in patients. This is the first report of osteomyelitis (OM) caused by A. hydrophila in Colombia. Infection by this pathogen should be suspected in patients exposed to aquatic environments who are refractory to initial therapeutic measures. Immunocompromised patients are more susceptible. Both cases reported here involved immunocompetent patients, and in one instance, a direct relationship with contaminated water could not be established, making the diagnosis and treatment more challenging.

In the first case, we successfully completed and documented the reconstruction of an extensive osseous defect caused by this pathogen, which required multiple interventions and several years of treatment. This case exemplifies the complexity of managing such infections and highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary approach.

Conversely, the second case, while we have not been able to complete follow-up due to the patient's incarceration and transfer to prison healthcare services, is equally significant. It underscores the magnitude of damage caused by this infection to both soft tissue and bone. This case also required reconstruction for an extensive osseous defect, involving multiple surgical interventions and demonstrating the severe impact of this pathogen on the musculoskeletal system.

Post-traumatic OM caused by A. hydrophila in immunocompetent patients is a rare entity, with only 10 case reports encompassing 13 patients (Table 1) [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]. In 12 of these cases, the site of OM was the lower limb, and 7 cases were associated with trauma involving exposure to rivers, lakes, and seas. In one reported patient, there was no known exposure to contaminated water; however, in burn patients, the water used for wound care has been identified as a potential source of Aeromonas contamination [1]. It is hypothesized that this might have been the infection source in this patient.

Additionally, one reported patient was allergic to penicillins and was initially treated with quinolones, which are effective against Aeromonas in patients allergic to cephalosporins [14]. However, this patient was refractory to the treatment, necessitating an adjustment in the antibiotic regimen.

We consider that this condition may be underdiagnosed, as it is common to see open fractures exposed to water with catastrophic outcomes despite treatment. Examples include Hurricane Katrina, the Thailand Tsunami, and the Armero catastrophe in Colombia [14,15], where multiple episodes of soft tissue infections and complications from open fractures occurred with catastrophic outcomes despite therapeutic measures. However, there were no reported cases of osteomyelitis caused by Aeromonas in these scenarios.

The relevance of this study lies in proposing diagnostic suspicion keys for this rare but catastrophic entity, characterized by the following triad:

-

1.

Open fracture

-

2.

Water exposure

-

3.

Refractory to initial management

In cases where these factors are combined, it is important to take samples for culture, requesting processing with human or bovine blood culture methods, such as blood agar, chocolate agar, or MacConkey agar. Aeromonas characterization in the laboratory is not routinely performed; therefore, when suspected, it is crucial to inform the laboratory to actively search for this microorganism. The treatment should be a combination of medical and surgical approaches, including targeted antibiotic therapy and procedures to debride or resect compromised tissue. In some cases, aggressive interventions such as amputation may be required.

If the presence of the pathogen is confirmed, the literature recommends extensive bone resections, infection control with targeted antibiotic therapy, and surgical lavages and debridements, followed by bone reconstruction procedures, in collaboration with plastic surgery or orthoplastic services when necessary.

The evidence regarding the management of these cases is limited. In the reviewed literature, besides our cases, we identified one case managed with bone transport and free flap reconstruction. To our knowledge, no other case has been managed with bone lengthening. In the two cases reported here, we demonstrate the difficulty of treatment, the necessity of multiple procedures and bone resection for infection control, and the successful outcomes of reconstruction procedures using distraction osteogenesis techniques.

Conclusions

In conclusion, post-traumatic osteomyelitis caused by Aeromonas hydrophila in immunocompetent patients is an exceptionally rare but severe condition, underscoring the necessity for heightened clinical suspicion, especially in cases involving open fractures with aquatic exposure. The two cases presented demonstrate the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges posed by this pathogen, including the need for extensive surgical interventions and targeted antibiotic therapy. These findings highlight the critical importance of early identification and aggressive management to prevent catastrophic outcomes. Furthermore, the rarity of this condition and the complexity of its treatment call for more comprehensive reporting and research to establish standardized protocols and improve patient prognosis.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Juan Francisco Guio Oros: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. Estefanía Arias Cobos: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation. Juanita Villalba Reyes: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation. Jaime Andrés Leal: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used Chat GPT-4o in order to improve language and readability. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Vásquez Véliz R.M., Macero Gualpa L.J., Reyes Sánchez R.R. Infección de herida por aeromona hydrophila, reporte de un caso en Ecuador. Medicina (B. Aires) 2019;23(2):95–99. doi: 10.23878/medicina.v23i2.972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernández-Bravo A., Figueras M.J. An update on the genus Aeromonas: taxonomy, epidemiology, and pathogenicity. 2020;8(1) doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8010129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephen R., Rao S., Dumar K.N., Indrani M.S. Letter: human infection with Aeromonas species: varied clinical manifestations. Ann. Intern. Med. 1975;83:368–369. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-83-3-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blatz D. Open fracture of the tibia and fibula complicated by infection with Aeromonas hydrophila. A case report. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1979;61(790–91) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstock B., Bass R.E., Lauf S.J., Sorkin E. Aeromonas hydrophilia: a rare and potentially life-threatening pathogen to humans. J. Foot Surg. 1982;21:45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karam G.H., Ackley A.M., Dismukes W.E. Posttraumatic Aeromonas hydrophila osteomyelitis. Arch. Intern. Med. 1983;143(11):2073–2074. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1983.00350110051014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubey M., Krasinski L., Hernanz-Schulman K. Osteomyelitis secondary to trauma or infected contiguous soft tissue. 1988;7:26–34. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198801000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonatus A., Alexander T.J. Posttraumatic Aeromonas hydrophila osteomyelitis. Orthopedics. 1990;13:1158–1163. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19901001-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gold I., Salit W.L. Aeromonas hydrophila infections of skin and soft tissue: report of 11 cases and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1993;16:69–74. doi: 10.1002/0471263397.env027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunasekaran L., Ambalkar S., Samarji R., Qamruddin A. Post-traumatic osteomyelitis due to aeromonas species. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2009;27(2):163–165. doi: 10.4103/0255–0857.49435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agrawal S., Sharma G., Srigyan D., Nag H.L., Kapil A., Dhawan B. Chronic osteomyelitis by Aeromons hydrophilal: a silent cause of concern. J. Lab. Phys. 2017;9(04):337–339. doi: 10.4103/jlp.jlp_45_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsunoda T., Yasuda T., Igaki R., Takagi S., Kawasaki K. Post-traumatic Aeromonas hydrophila osteomyelitis caused by an infected Gustilo–Anderson grade 3B tibial fracture: a case report with a 7-year follow-up. J. Orthop. Case Rep. 2023;13(June):41–46. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2023.v13.i07.3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doganis D., et al. Multifocal Aeromonas osteomyelitis in a child with leukemia. Case Rep. Infect. Dis. 2016;2016:1–4. doi: 10.1155/2016/8159048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aguilar-García C. Infección de piel y tejidos blandos por el género Aeromonas. Skin and soft tissues infection due to Aeromonas. Med. Int. Méx. 2015;31:701–708. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patiño J.F., Castro D., Valencia A., Morales P. Necrotizing soft tissue lesions after a volcanic cataclysm. World J. Surg. 1991;15(2):240–247. doi: 10.1007/BF01659059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]