Abstract

The present study reports on the development and characterization of Mg-Ta-HA composites with powder metallurgy. The densities and porosities of magnesium composites and pure magnesium are calculated, and the Rule-of-Mixture method used to determine the theoretical density of the composites. It verified that dense pure magnesium and magnesium composites be produced using powder metallurgy techniques. Examining the composites’ microstructures reveals the uniformity of the grain size as well as the impact of changing the Ta and HA reinforcement. The lack of intermetallic compounds between magnesium and reinforcement confirmed by X-ray diffraction analysis. Magnesium powders undergo mechanical milling to lower their average particle size, and reinforcement materials added to further reduce the particle size. The milling process results in a decrease in powder size due to the friction generated by the reinforcement materials. Both the compressibility of the green compacts and the attachment of particles during sintering impact the densification and porosity of the composites. The results indicate that composites with 3 and 6 wt% Ta have fine Ta and HA particles evenly dispersed in the Mg matrices, with no voids. In contrast, composites with 8 wt% HA and 9 wt% Ta show agglomeration of Ta particles in the Mg matrices and the appearance of noticeable voids. As the Ta, content increases from 0 to 6 wt%, the ultimate compression strengths, failure strain, and elastic moduli of the composites tend to rise. However, these properties seem to decrease as the Ta content increases further from 6 to 9 wt%. Nonetheless, the yield strength increases as the Ta reinforcement goes from 6 to 9 wt%. It suggested identify the optimal parameters for producing biocompatible Mg composites with appropriate strength, hardness, and ductility.

Keywords: Powder metallurgy, Magnesium, Composites, Tantalum, Hydroxyapatite, Reinforcement

Subject terms: Biomaterials, Materials for devices, Structural materials

Introduction

The properties of magnesium (Mg) in terms of mechanics closely resemble those of natural bone. Moreover, it boasts excellent biocompatibility and lower densities compared to other metallic biomaterials1,2. These characteristics render it a suitable biodegradable material for orthopedic purposes. The elastic modulus of magnesium alloy is akin to that of human bone, thereby preventing the stress shielding effect on human bone1,3. This sets it apart from other metallic biomaterials such as titanium alloys, stainless steels, and cobalt-chromium based alloys1,4.

After implantation, magnesium and magnesium alloy, which are biodegradable materials, act as temporary implants2,4. Unlike stainless steel implants, which require a revision procedure to remove from the body after 15–20 years of implantation, these implants disintegrate, in vivo and replaced by new bone tissue4,5. This considerably lowers the patient’s ongoing suffering and medical expenses. The main disadvantage of magnesium alloy in biological contexts is that it corrodes quickly in an electrolytic aqueous medium, which can have negative effects on living things. For their possible use in biomedical applications, magnesium alloy must therefore have increased corrosion resistance1–3.

The metallic ions generated from magnesium (Mg) alloy must be biodegradable and have as little harmful effects as possible. It is ideal if they can also accelerate metabolism and aid in tissue healing2,3. Nevertheless, metallic ions frequently have an impact on tissue repair and are not entirely friendly. The early loss of mechanical integrity caused by the rapid deterioration of magnesium alloy can also cause the implant to collapse before the tissue has had enough time to recover4,6.

The release of metallic ions from corrosion can lead to reduced biocompatibility and can initiate inflammatory responses when alloying elements become toxic to cells. Regrettably, the current magnesium alloy deteriorates rapidly in the electrolytic environment of the human body1,2. This result in the implant’s mechanical integrity compromised prematurely, leading to inadequate mechanical properties before the host tissue has sufficient time to heal3,4. The rate of corrosion significantly affects the mechanical properties of magnesium alloy in a physiological setting as it causes the mass and structural integrity of the magnesium to degrade gradually2,7. Therefore, it is crucial to develop new magnesium alloy materials with enhanced corrosion resistance for use in biomedical applications2,5.

Concerns regarding hydrogen gas generation following implantation in vivo due to corrosion raised by reinforced magnesium implants. Among all engineering metals, magnesium has the lowest standard potential (− 2.38 Vnhe), making it highly susceptible to the physiological environment. However, conditions such as surface condition and environment affect Mg’s particular corrosion potential2–4. The corrosion potential of magnesium is usually − 1.7 Vnhe in diluted chloride solutions, and the surface layer of magnesium (OH) 2 has a significant impact on the corrosion kinetics of magnesium4,8.

The microstructure, including grain size, boundaries, and phase distribution, has a considerable impact on the corrosion characteristics of Mg alloys4,9. Grain refining can alter the distribution and boundaries of the grains, which can change the mechanical characteristics and corrosion behavior of magnesium alloys2. In order to achieve the requirements for implant applications, it is crucial to understand the factors affecting the corrosion rate of magnesium alloys2,4. Reinforced magnesium quickly corrodes in a physiological environment and emits large amounts of hydrogen gas, both of which may have very negative impacts on human health9.

To comprehend its major influence on the corrosion behavior, a great deal of study has done on the composition design and post-treatment of biodegradable magnesium alloys1,2. The composition design provides a solid basis for the development of biodegradable magnesium alloy, especially when it comes to the careful selection of alloying components that improve mechanical and corrosion resistance. Because the structure and phase distribution of the included elements might alter, the resulting mechanical and physical properties can be somewhat different3,10.

Appropriate magnesium alloys have made by combining components such as zinc (Zn), manganese (Mn), calcium (Ca), aluminum (Al), and others. These alloys anticipated to have improved mechanical qualities and increased resistance to bio corrosion for possible application in biodegradable implants2,3,11. Since calcium has a low density of 1.55 g cm−3, it is a key component present in human bone in the form of hydroxyapatite (HA). This property makes magnesium–calcium alloys lightweight materials5,11.

The intermetallic phases Mg–Ca formed when Ca is present in Mg. Because of these brittle phases that disperse across grain boundaries, Mg–Ca alloys become less ductile2,4,12. Furthermore, because of the galvanic interactions between the Mg matrix and the Ca phases, Mg–Ca alloys with high Ca contents show decreased resistance to bio corrosion. When Mg–Ca alloys degrade, non-soluble compounds that resemble “chalk” can formed in high quantities that can be harmful to human health5,13.

Instead of forming magnesium intermetallic phases, the alternative method of adding reinforcements to the magnesium matrix results in a composite structure with higher wear resistance, corrosion performance, and mechanical qualities3,5. In addition to providing excellent design freedom for components and reinforcement materials, the usage of composites can address magnesium’s biocompatibility2,4. Over the past few decades, different kinds of reinforcements have used in the magnesium matrix. Despite being the original reinforcements in the magnesium matrix, continuous fibers eventually replaced by discontinuous fibers and whiskers because of a number of factors, including the expense and limited availability and fabricability of continuous fibers3,5. Particles already employed commercially and garnering more interest as alternate kind of reinforcement3,14.

The Powder Metallurgy (PM) technique commonly used to produce composite materials as it allows for homogenous distribution of reinforcing elements, resulting in superior properties2,3. This involves mixing the matrix and reinforcement elements, compressing them in a metal mold, and sintering at a certain temperature in a protective gas atmosphere3,15.Powder metallurgy (PM) is an advanced manufacturing process that involves the production of materials and components from metal powders. This technique is widely used for fabricating complex shapes and achieving desirable properties in various alloys, including titanium (Ti) and niobium (Nb) alloys, which are particularly significant in biomedical applications2.

The properties of composites, matrix materials, and reinforcements largely determined by the fabrication process3,14. The two main techniques used to create particle-reinforced magnesium composites are molten processes and powder metallurgy (PM)14,15. The high activity of molten magnesium, the inability of particular particles to be wettable by molten magnesium, and the reactivity of certain reinforcements with molten magnesium are all relevant considerations when employing the molten technique3,14,15. In contrast, the low-temperature powder metallurgy process works well with the magnesium matrix and highly reactive, low-wettable reinforcements. Furthermore, PM is a potential approach for Mg because it allows for higher reinforcement material flexibility, the utilization of high volume fractions of reinforcements up to 50%, and increased uniformity14–16.

Powder metallurgy is a crucial technology in the development of advanced materials, particularly in the biomedical field. The combination of techniques such as hot pressing and high-temperature sintering enables the production of high-performance Ti–Nb alloys with tailored properties suitable for various applications, including load-bearing implants. As research in this area progresses, PM expected to play an increasingly significant role in the manufacturing of innovative materials3,15

Alloying elements, microstructure, corrosion environment, and manufacturing processing significantly affect the biodegradation behavior of Mg alloys4,5. One of the most important factors affecting the corrosion resistance of Mg alloys is the intermetallic phases formed at the grain boundaries5.

Through the PM method, biocompatible tantalum (Ta) and hydroxyapatite (HA) particles can added to the magnesium matrix. High-strength Mg-Ta-HA composites have been successfully produced by researchers using powder metallurgy2,3,15. Ta and HA, particles distributed consistently throughout the magnesium matrix and no intermetallic formation seen15. Ta additions up to 9 weight percent resulted in better mechanical characteristics for Mg-Ta composites. Harder reinforcing elements in the magnesium matrix, which reduce local deformation during the indentation process, are responsible for this improvement15,17.

When hydroxyapatite used in combination with tantalum, it can provide several benefits. Tantalum has a high modulus of elasticity, which means it is stiff and provides good structural support3,15. However, it lacks the ability to bond directly with bone. By incorporating hydroxyapatite onto the surface of tantalum, the composite material can exhibit improved osseointegration, which is the ability of the implant to integrate with the surrounding bone tissue2–4,15. The hydroxyapatite coating promotes bone cell attachment and enhances the formation of a direct bond between the implant and the bone, leading to improved implant stability and longevity3,11.

The incorporation of hydroxyapatite onto tantalum and the reinforcement of magnesium with hydroxyapatite can improve the performance of these materials in medical implant applications3,15. The enhanced osseointegration and mechanical properties offered by hydroxyapatite can contribute to the long-term success of implants by promoting bone integration and stability. However, it is worth noting that the specific properties and performance of these composite materials can depend on various factors such as the fabrication method, particle size, and distribution, as well as the implant design and application2,17.

Materials and methdology

HA (reagent level, Parameet Co. ltd., South Korea), Mg (purity: ≥ 99.9%, 60 ≤ size ≤ 220 μm, Sigma-Aldrich, USA), and Ta (purity ≥ 99.9%, 2 ≤ size ≤ 15 μm, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were the three commercially available powders used as starting materials. A combination of Mg-Ta-HA powders was made using high intensity ball milling in a predetermined proportion of Mg, Ta, and HA powders. The ball milling process took place in an argon-protected environment for nine hours, using a planetary ball mill PM 400-Retsch. During ball milling, a 20:1 ball-to-powder ratio and a 200-rpm rotation speed employed. A homogenous mixture of Mg-Ta-HA powders uniaxially pressed into a cylindrical compact by milling pure magnesium powder, which acted as the control material, under pressure of 760 MPa. The green compacts then sintered at 610 °C for three hours. The densities of pure magnesium and its composites calculated using the Archimedes’ Principle Three samples picked at random and weighed using an electronic balance that had an accuracy of ± 0.0001 g in both air and distilled water. Following that, the sintered samples were grounded using 1200 grit SiC paper, and their micro hardness was measured using a Vickers Hardness HVS-50 micro hardness tester in accordance with ASTM E384-9918. X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) carried out using the XRD-7000S Powder Diffractometer (South Korea) using CuKα radiation. An Olympus optical microscope and a COXI EM-30 scanning electron microscopy (SEM) used to analyze the microstructure and powders of composite materials. A diamond-wafering blade used to cut sintered samples transversely in order to assess the porosity and pore size distribution. The sliced surfaces then polished to a 4000 grit SiC paper finish. Lineal Analysis (LA) technique, commercial program Image J, and SEM images used to quantitatively quantify porosity and pore size distribution19. Three samples of each composition divided into five cross sections, for fifteen sections that examined, in order to produce a reliable statistic for porosity and pore size distribution. At last, an Instron universal tester (Instron 5567, 30 kN, South Korea) was used to perform a compression test on the cylindrical samples, which had a size of Φ10 × 15  . The initial strain rate was set at

. The initial strain rate was set at

. Each composition evaluated in six samples. Flow of energy. A combined geothermal and solar chimney power plant generates electricity by utilizing both geothermal heat and solar energy. Geothermal heat is extracted from underground sources, and solar energy is captured with solar collectors. The system employs a chimney to generate an updraft, which drives a turbine and generates electricity.

. Each composition evaluated in six samples. Flow of energy. A combined geothermal and solar chimney power plant generates electricity by utilizing both geothermal heat and solar energy. Geothermal heat is extracted from underground sources, and solar energy is captured with solar collectors. The system employs a chimney to generate an updraft, which drives a turbine and generates electricity.

Results and discussion

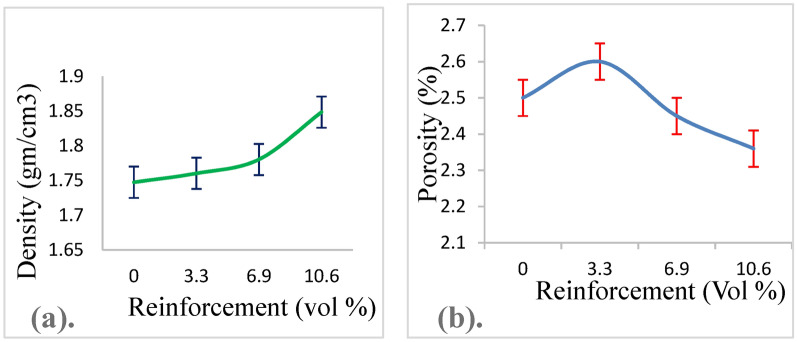

The successful fabrication of Mg-Ta-HA composites using powder metallurgy demonstrated in Fig. 1. As a reference, pure magnesium also created. Current pure magnesium and magnesium composites’ densities and porosities shown in Table 1. Utilizing the Rule-of-Mixture (ROM) method (Eq. 1), the theoretical density of composite materials was determined by utilizing the density values ("ρ_Mg = 1.739 gm/cm)3, "ρ_Ta = 16.69 gm/(cm)3, ρ_Ha = 3.15 gm/cm)3 and volume fraction of metal matrix and reinforcements.

|

1 |

where, ρ is density (gm/cm3) and V is volume fraction (vol%).

Fig. 1.

Using a powder metallurgy method, sintered pure magnesium and magnesium-Ta-HA composites created.

Table 1.

Porosity and density of pure Mg and Mg-Ta-HA composites.

| Composition | Fraction of reinforcement | Density (gm/cm3) | Porosity (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ta (wt%) | HA (wt%) | Ta (vol%) | HA (vol%) | Theoretical | Experimental | ||

| Mg | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.74 | 1.7474 ± 0.005 | 2.5 |

| Mg3Ta8HA | 3 | 8 | 3.3 | 4.7 | 1.77 | 1.7602 ± 0.001 | 2.6 |

| Mg6Ta8HA | 6 | 8 | 6.9 | 4.85 | 1.82 | 1.7803 ± 0.001 | 2.45 |

| Mg9Ta8HA | 9 | 8 | 10.6 | 5.0 | 1.91 | 1.8484 ± 0.002 | 2.36 |

The possibility of creating nearly dense pure magnesium and magnesium composites using PM and milling techniques is approved by the small discrepancies between theoretical and experimental densities.

The powder pressing process usually involves a compaction pressure of 760 MPa. The metal particles undergo reorganization a result of the pressure applied by the punches, and their irregular shapes lead to interlocking between them. High pressure can occasionally even cause the particles to weld cold. This provides the compact with enough green strength.

Nonetheless, the microstructures exhibit micro-pores. Because of the trapped air between the magnesium particles, which is a result of the fabrication process, porosity is a typical feature of the powder metallurgy process. It might also have something to do with magnesium volume shrinkage20. The pores in PM steels will have an unparalleled effect on the material’s characteristics because they create places where stress concentrates. However, the primary issue with PM steel is definitely the pore properties.

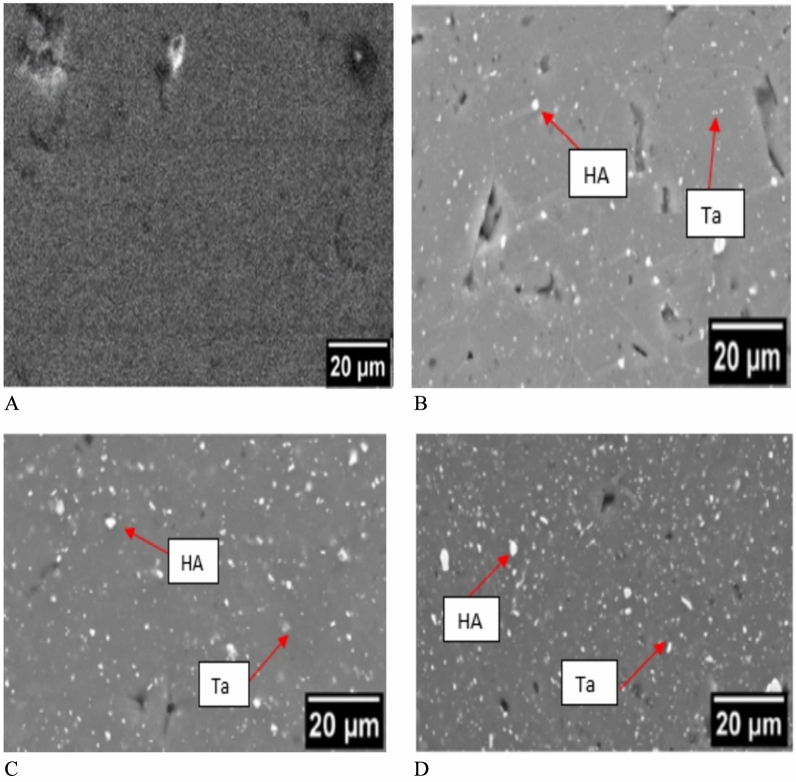

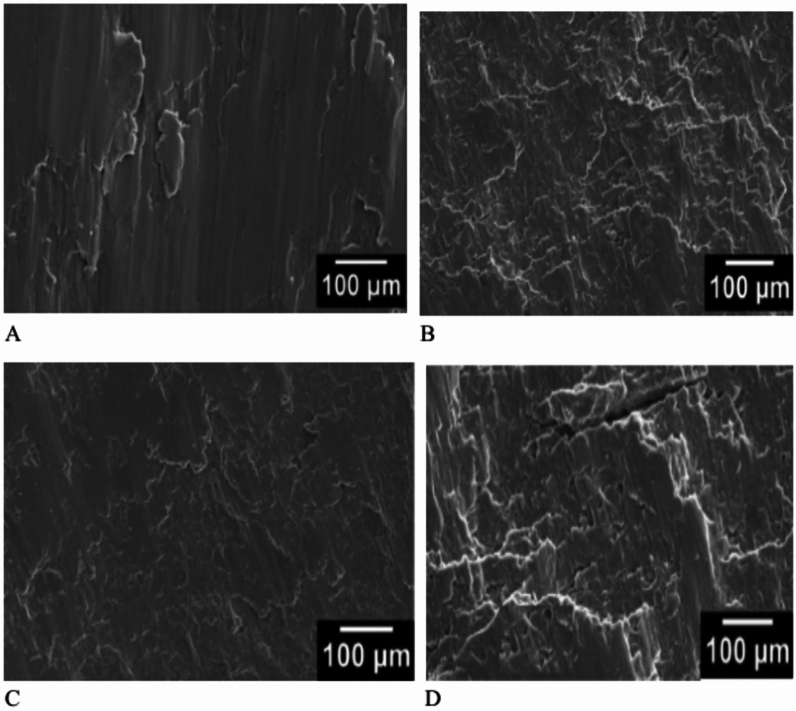

The microstructures of Mg-Ta-HA, with varying Ta and HA reinforcement, depicted in Fig. 2A. Each reinforced Mg was shown to have homogenous grain size; however, as Ta increased, the grain size shrank, as demonstrated by the reinforced Mg3Ta8HA, Mg6Ta8HA, and Mg9Ta8HA (Fig. 2C, D). When compared to Mg3Ta8HA and Mg6Ta8HA with the same HA content, the microstructure of Mg9Ta8HA (Fig. 2D) had a thicker grain boundary and a smaller grain size, indicating that the high Ta content of the reinforced Mg refined the grain size but resulted in thick grain boundaries (Figs. 2B, C). A uniform distribution of Ta and HA particles within the magnesium matrix, reducing the likelihood of agglomeration and enhancing mechanical integrity. This uniformity is crucial for maintaining consistent performance in biomedical applications, as opposed to some studies where uneven distributions noted.

Fig. 2.

SEM images of (A) Mg (B) Mg3Ta7HA (C) Mg6Ta7HA (D) Mg9Ta7HA.

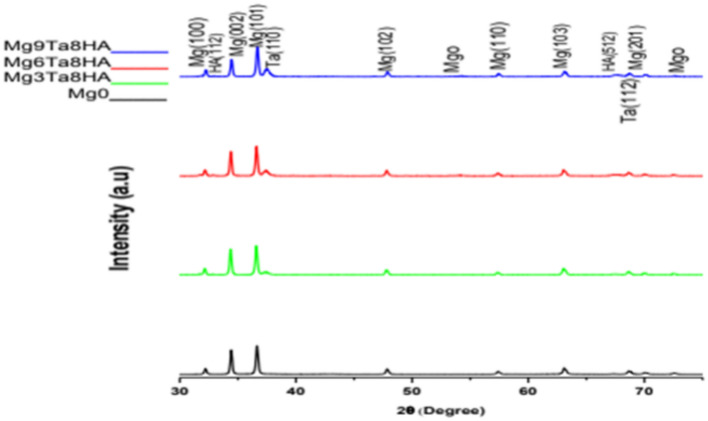

Figure 3 Displays the magnesium composites’ XRD results. The XRD patterns show distinct Ta and HA peaks in addition to the Mg-attributed peaks. It demonstrated that the Ta peaks in the composite containing 9 wt% Ta are stronger than those in the composite containing 3 wt% or 6 wt% Ta.

Fig. 3.

X-ray diffraction pattern of Mg composites.

The relationship between magnesium and reinforcements does not exhibit a peak that could be associated with novel intermetallic compounds. One of the most important factors affecting the corrosion resistance of Mg alloys is the intermetallic phases formed16.This promotes the creation of magnesium composite structures and verifies that there is no reaction between magnesium and reinforcing particles.

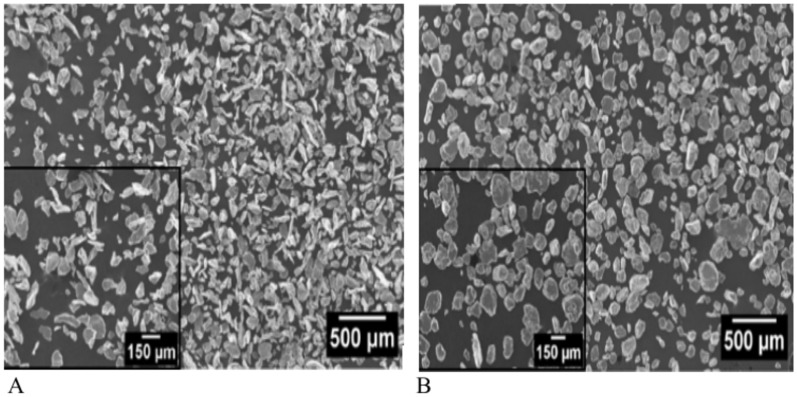

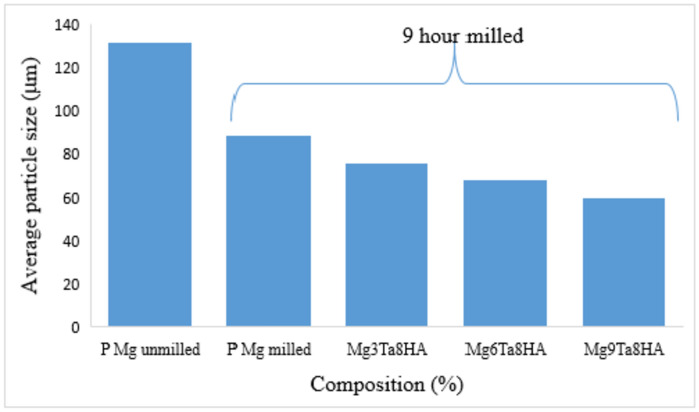

Figure 4A shows that the unmilled powder has nearly uniformly shaped particles, while Fig. 4B shows that the particles in the 9-h milled powder have elongated and uneven shapes. The average particle size of magnesium powders is measured (Fig. 5), which provides more evidence that the average size of magnesium powders decreased through mechanical milling. The average particle size of the magnesium powders decreased by the addition of reinforcing materials to the combination powders. In Mg-Ta-HA combinations, the average size of magnesium powders falls to approximately 76, 68, and 60 µm, respectively, upon adding 3, 6, and 9 weight percent Ta and 8 weight percent HA during the milling process. In the meantime, the Ta content rises to 3, 6, and 9 weight percent, in that order.

Fig. 4.

SEM pictures of pure magnesium powder, (A) without milling, and (B) after milling for 9 h.

Fig. 5.

The mean particle size of unmilled pure magnesium &9 h milled composite.

The friction between the magnesium particles and the reinforcing materials produces the reduction in powder size in combinations during the milling process. In this case, reinforcements act like abrasive materials because the hardness of HA (115–160 HV) and Ta particles (90–200 HV) is higher than that of Mg (30–45 HV)16,17.

The samples had a higher densification and less porosity a result of the green compacts’ improved compressibility and the particles’ adhesion during the sintering process23.The minuscule contact surfaces between the particles increase as the density of the compact increases and the total void volume decreases, as illustrated in Figs. 6a, b, respectively. Smaller diameter particles will have higher surface area and free energy. The effectiveness of powder metallurgy in producing dense magnesium composites with controlled porosity. This contrasts with other methods that may not achieve the same level of density or structural uniformity.

Fig. 6.

Density (a) and porosity (b) of pure magnesium and magnesium composites.

Green compacts created by consolidating magnesium powders and joining them together with high pressure and sintering temperature, respectively. This resulted in low enclosed air trapped between the particles, causing the microstructures to have low porosity. The magnesium granules’ size also lowered by mechanical milling, which in turn reduced the samples’ porosity. The uniform distribution of HA and Ta particles in the magnesium matrix and the almost zero standard deviation of observed densities (Table 1) provide additional evidence for the uniform dispersion of these reinforcements in magnesium composites.

Tantalum (Ta) and hydroxyapatite (HA) particles uniformly distributed inside the magnesium matrix of the microstructures (Fig. 2). The almost zero standard deviation of the measured densities (as seen in Table 1) supports the uniform distribution of these reinforcements in the magnesium composites. Notably, no particle clustering—that is, tightly spaced particles—was observed, even at high Ta levels of up to 9%. The absence of high-particle concentration areas in the microstructures may be explained by the notable variations in Mg, Ta, and HA’s ensities (1.74, 16.69, and 3.16 g/cm3, respectively)24.

Specific effects of adding HA to the microstructures of Ta and Mg composites include reduction of porosity and defects, interfacial bonding, phase distribution, and grain refinement. The microstructures’ even distribution and flawless interfaces show that the fabrication process was successful in creating a solidly bonded composite system.

The relatively homogenous distribution of Ta particles in the 3,6 weight percent Ta composites can be attributed to appropriate mixing conditions. However, in high content of HA and Ta, a limited amount of reinforcing clustering was unavoidable because to the high surface energy associated with the ultrafine particles25.

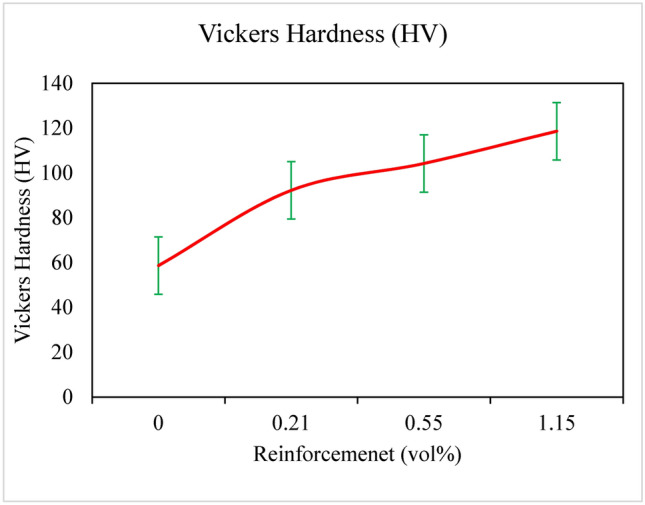

The microhardness values of pure magnesium and magnesium composites shown in Fig. 7. Hardness values increase considerably with rising Ta Vf when compared to pure Mg; at 10.6%VZ, there is an up to 190% increase in hardness values.

Fig. 7.

Micro hardness of pure Mg and Mg-Ta-HA composites.

The rise in micro hardness values can be attributed to the high hardness of the Ta and HA reinforcement particles, which are measured as Ta (90–200 HV) and HA (90–200 HV) in the current work. The high hardness of the reinforcing particle would accelerate matrix work hardening and increase the total hardness of the composites. Stronger reinforcement materials added to the magnesium matrix can credited with this increase, as they reduce the local deformation of the matrix during the indentation process. Significant increases in compressive yield strength and microhardness with the addition of tantalum (Ta) and hydroxyapatite (HA). Specifically, the highest values are achieved at 9 wt% Ta, suggesting an optimized reinforcement strategy not extensively covered in prior research.

It was found that the significant increases in micro hardness values of the created composites are either better than or on par with the typical metallic/metallic particle reinforced composites. This suggests that the high elastic strain of the amorphous reinforcement particles had a substantial impact on the retention and improved ductility of the composites.

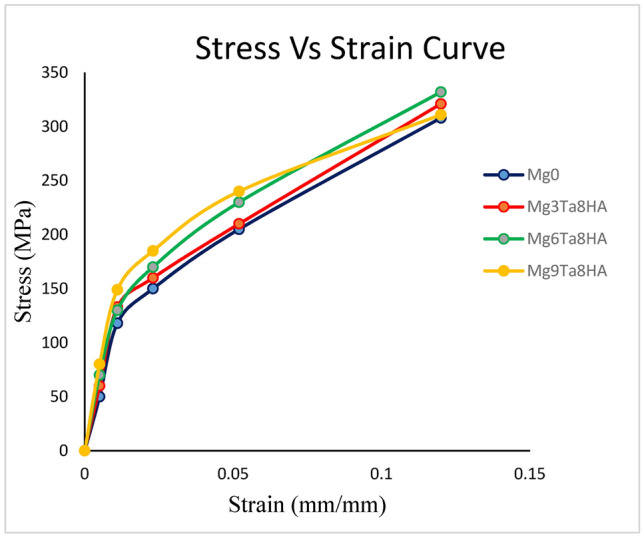

The compressive stress–strain curves and compressive characteristics of pure magnesium and magnesium composites shown in Fig. 8. Knowing the stress level at which yielding or plastic deformation commences is crucial. The point at which the stress–strain curve first deviates from being linear, signifying the onset of microscopic plastic deformation, known as the point of yielding, or the proportional limit. It can be difficult to pinpoint the precise location of this proportional limit. Drawing a straight-line parallel to the elastic region of the stress–strain curve at a specific strain offset—typically, 0.002—is one standard that advises addressing this. The stress that results from this line’s intersection with the stress–strain curve as it bends over in the plastic zone is the yield strength.

Fig. 8.

Stress–strain curves for Mg-Ta-HA and pure magnesium composites.

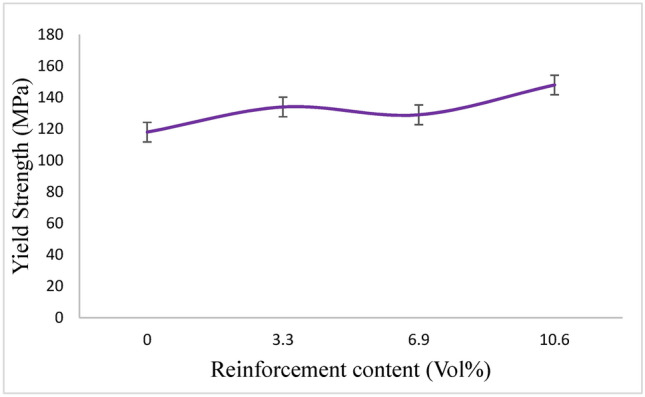

The Mg-Ta-HA composites’ compressive yield strength increased when more Ta particles were added; the highest values were attained at 9 weight percent of the Ta particles, as indicated in (Fig. 9). Throughout the mixing process, it noted that the Ta particles had an even impact on the magnesium granules’ near surfaces. The uniform distribution of Ta and HA particles close to the magnesium matrix’s grain boundaries may be the cause of the notable increase in compressive characteristics brought about by the addition of a minor quantity of Ta particles26.

Fig. 9.

Yield strength of magnesium compounds and pure magnesium derived from the stress–strain curve.

The size and existence of every obstruction that prevents dislocations from moving freely within the matrix affects the yield strength, or the stress needed to activate the dislocation sources. In contrast to magnesium, the agglomeration of multi-glide planes under compressive stress generates grain boundary ledges that prevent dislocation movement and pile-ups, resulting in a substantially greater composite yield strength27. However, when the Ta particle addition is 6.9 Vol%, the increased agglomeration of Ta particles and the consequent formation of pores and defects can account for the decline in yield strength27.

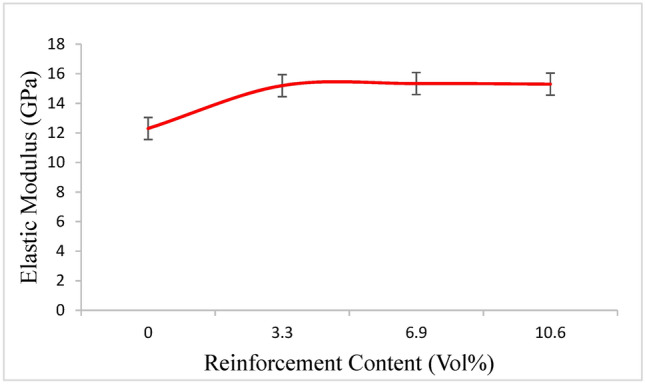

The elastic modulus results showed that a greater elastic modulus correlated with an increase in the weight percentage of the TA particles. The highest increase in elastic modulus (as illustrated in Fig. 10) was noted at 10.9 vol% of Ta in the Mg-Ta-HA composites. The presence of high elastic modulus reinforcement26 and uniform distribution of reinforcement with good interfacial integrity are the reasons for the rise in the elastic modulus of the magnesium matrix27.

Fig. 10.

Elastic Modulus of pure Mg and Mg composites obtained from stress–strain curve.

It should be noted that the reinforcement was distributed uniformly and that the reinforcement-matrix interfacial integrity was good, which significantly increased the internal stress between the reinforcement and the matrix and improved the elastic modulus27.

The amount of reinforcement and the bonding between the reinforcement particles and matrix determine how well the restriction of particle deformation works. Figure 11 illustrates how the elastic modulus dropped from 3.3 to 10.6 vol% as the reinforcing content increased. Agglomeration can lead to decreased ductility and the creation of micro gaps between reinforcement particles, even if a larger reinforcement content can encourage strengthening.28.

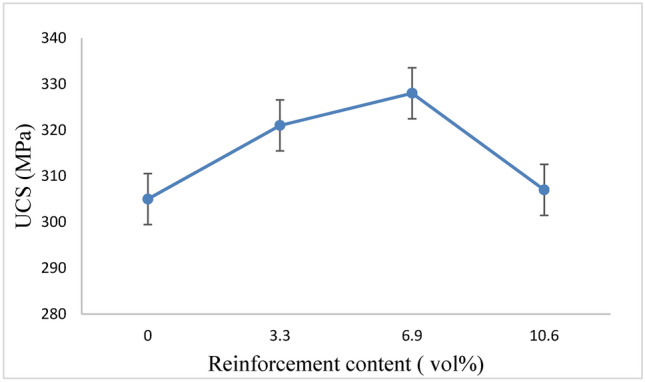

Fig. 11.

UCS of magnesium alloys and pure magnesium derived from the stress–strain curve.

When the Ta contents of the composites increase from 0 to 6.9 Vol%, they tend to increase in ultimate compression strengths (UCS) but seem to decrease when the Ta contents increase from 6.9 to 10.6 Vol%. The composite with 6.9 vol% Ta yielded a maximum UCS of approximately 328 MPa, which is 10.6 vol% higher than that of Mg.

10.6 Vol% Ta composites show a slight agglomeration of Ta particles; however, the former composites have more and larger agglomerates than the latter. The findings show that slight agglomeration has no effect on the composites’ strength. Agglomeration of Ta particles also occurs in composites containing 10.6 vol% Ta, which lowers the composites’ elastic properties.

The primary cause of the reinforcement particle agglomeration is the cold welding of the reinforcements during the milling process. According to research reports23,29,30, ductile particle agglomeration and cold welding occur during the mechanical milling process. Particle aggregation lowers the reinforcements’ uniformity of distribution in the magnesium matrix, which lowers their mechanical properties31,32.

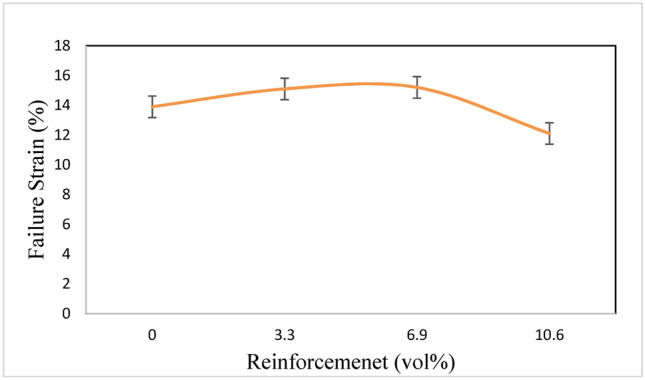

Particle agglomeration in the magnesium matrix, especially in composites with a high reinforcement content, is responsible for the failure strain drop. Figure 12 illustrates how the failure strain decreases as the amount of Ta reinforcement increases.

Fig. 12.

Failure Strain (%) of pure Mg and Mg composites obtained from stress–strain curve.

Lower failure strain is a result of Ta particulate size in Mg-Ta-HA composites. Mg powders surrounded more tightly by Ta particles, which act as fine reinforcements to create a network of hard particles that flexibly support a portion of the applied pressure. As a result, green compacts with a lower failure strain at 10.6 vol% Ta reinforcement content are produced, with less effective compressive pressure needed to compact the powders.

Dislocation pile-ups also result from a large number of reinforcing Ta particles acting as barriers to the dislocation movement23–25,25–35. The strengths of the composites should inevitably rise with an increase in the weight fraction of Ta particles, as indicated by the contributions made by the strengthening mechanisms previously mentioned.

Nevertheless, the strengths of the composites usually begin to decrease when the Ta concentration reaches 10.6 Vol%. The existence of discrete voids and comparatively bigger Ta particle clusters could account for this. The HA particle aggregation may result in poor combination and grain boundary embrittlement, which could reduce the strengths of the composites. The bulk of the composite’s particle clusters had a Ta concentration of 10.6 vol%. Consequently, it expected that the contribution of Orowan strengthening in the composite with 10.6 Vol% Ta will diminish once the clusters reach a critical size36.

The strongest results in the current study were obtained with the addition of 6.9 Vol% Ta. Nonetheless, the following explanations account for the composites with 3.3 and 6.9 Vol% Ta having higher elastic moduli: High reinforcement modulus (a); even reinforcement distribution with strong interfacial integrity (b); increased internal stress between reinforcement and matrix (c); and strong loading transfer capability of the matrix-reinforcement interface37,38.

When the concentrations of Ta increase from 6.9 to 10.6 Vol%, flaws such as porosity may cause the elastic modulus to drop 36. Since magnesium composites have an elastic modulus of 15.34 GPa, which is similar to human bone, they seem to be a great choice for implants that are intended to reduce bone absorption and stress shielding.

Figure 13 displays the fractured surfaces of pure Mg and Mg composites. Figure 13 A The fracture surfaces of pure Mg shows dominant brittle mode fracture. The rough fracture surfaces appeared by addition of Ta to 3% (Fig. 13b), indicate mixed shear and brittle mode of fractures. The fracture surface of Mg6Ta (Fig. 13C) and Mg9Ta (Fig. 13D) showed less rough surface compared to Mg3Ta (Fig. 13B), indicating that the fracture is altered from the dominant shear to mixed shear and prominent brittle fractures with increasing Ta content.

Fig. 13.

SEM images of fractured surfaces of (a) pure Mg, (B) Mg3Ta7HA (C) Mg6Ta7HA (D) Mg9Ta7HA composites after compression test.

Overall, the present findings build upon existing literature by providing advancements in mechanical performance, microstructural uniformity, and biocompatibility, while effectively addressing critical challenges associated with magnesium alloys in biomedical applications.

Conclusion

This study successfully demonstrates the fabrication of Mg-Ta-HA composites using powder metallurgy, achieving nearly dense magnesium and composite materials. The close alignment between theoretical and experimental densities indicates the effectiveness of the fabrication process. Microstructural analysis revealed uniform grain sizes with varying amounts of tantalum (Ta) and hydroxyapatite (HA) reinforcement, while the addition of these reinforcements effectively reduced the average particle size of magnesium powders.

X-ray diffraction analysis confirmed the presence of Ta and HA in the composites without any intermetallic reactions between the magnesium and the reinforcement particles. The milling process enhanced densification and reduced porosity due to friction between the magnesium powders and the reinforcements, resulting in a uniform distribution across the magnesium matrix.

Overall, the findings highlight the potential of Mg-Ta-HA composites to possess desirable characteristics such as enhanced mechanical properties, improved interfacial bonding, and reduced porosity, making them promising candidates for biomedical applications, particularly in orthopedic implants. Further research can explore optimizing the composition and processing parameters to enhance their performance and biocompatibility.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to God for His unwavering guidance and blessings in every as-pect of my life. My family’s support and love have been invaluable, and I blessed to have them. I appreciate my co-worker’s contributions and collaboration in this re-search. Thank you to everyone who contributed to its success.

Author contributions

T.S, A.G: Significant contribution to the concept, analysis and interpretation of the data and writing of the article. H.M.: Critically drafted and revised the article for significant intellectual content and made a significant contribution to the concept of the article.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available within the article.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ding, Y., Wen, C., Hodgson, P. & Li, Y. Effects of alloying elements on the corrosion behavior and biocompatibility of biodegradable magnesium alloys: A review. J. Mater. Chem. B2, 1912–1933 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aydoğmuş, T., Palani, D. K. H. & Kelen, F. Processing of porous β-type Ti74Nb26 alloys for biomedical applications. J. Alloys Compd.872, 159737 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ercetin, A. et al. Microstructural and mechanical behavior investigations of Nb-reinforced Mg–Sn–Al–Zn–Mn matrix magnesium composites. J. Metal13, 1097 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ercetin, A. A novel Mg-Sn-Zn-Al-Mn magnesium alloy with superior corrosion properties. J. Metal. Res. Technol.118, 504 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ercetin, A. & Pimenov, D. Y. Microstructure, mechanical, and corrosion behavior of Al2O3 reinforced Mg2Zn matrix magnesium composites. Mater. J. Metal14, 4819 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wen, C. E. et al. Processing of biocompatible porous Ti and Mg. Scr. Mater.2001(45), 1147–1153 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witte, F. et al. In vivo corrosion of four magnesium alloys and the associated bone response. Biomaterials26, 3557–3563 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guangling, S. Control of biodegradation of biocompatable magnesium alloys. Corros. Sci.49, 1696–1701 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Izumi, S., Yamasaki, M. & Kawamura, Y. Relation between corrosion behavior and microstructure of Mg–Zn–Y alloys prepared by rapid solidification at various cooling rates. Corros. Sci.51, 395–402 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Persaud-Sharma, D. & McGoron, A. Biodegradable magnesium alloys: A review of material development and applications. J. Biomimetics Biomater. Tissue Eng.12, 25–39 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li, Z., Gu, X., Lou, S. & Zheng, Y. The development of binary Mg–Ca alloys for use as biodegradable materials within bone. Biomaterials29, 1329–1344 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zainal-Abidin, N. I., Atrens, A. D., Martin, D. & Atrens, A. Corrosion of high purity Mg, Mg2Zn0.2Mn, ZE41 and AZ91 in Hank’s solution at 37 C. Corros. Sci.53, 3542–3556 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirkland, N. T., Lespagnol, J., Birbilis, N. & Staiger, M. P. A survey of bio-corrosion rates of magnesium alloys. Corros. Sci.52, 287–291 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vahid, A., Hodgson, P. & Li, Y. Reinforced magnesium composites by metallic particles for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. A685, 349–357 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aydoğmuş, T., Al-zangana, N. J. F. & Kelen, F. Processing of β-type biomedical Ti74Nb26 alloy by combination of hot pressing and high temperature sintering. Konya J. Eng. Sci.8(2), 269–281 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chmelík, F. et al. Adv. Eng. Mater.2, 600–604 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mabuchi, M., Kubota, K. & Higashi, K. High strength and high strain rate superplasticity in a Mg-Mg2Si composite. Scr. Metall. Et. Mater.33, 331–335 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 18.ASTM-E384-99, Annual Book of ASTM, 03.01 (1999).

- 19.Vander Voort, G. F. Metallography, Principles and Practice (USA) (ASM International, 1984). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen, C. E. et al. Processing of biocompatible porous Ti and Mg. Scr. Mater.45, 1147–1153 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lloyd, D. Particle reinforced aluminum and magnesium matrix composites. Int. Mater. Rev.39, 1–23 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Handbook, M. Properties and Selection of Metals Vol. 1, 1206 (American Society for Metals, 1961). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nouri, A. & Wen, C. Surfactants in mechanical alloying/milling: A catch-22 situation. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci.39, 81–108 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taarea, D. & Bakhtiyarov, S. I. 14—General Physical Properties. In Smithells Metals Reference BookEighth (ed. Totemeier, W. F. G. C.) 1–45 (Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong, X.L., Wong, W.LE., Gupta, M. Enhancing strength and ductility of magnesium by integrating it with aluminum nanoparticles. Acta Mater.55, 6338 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimizu, Y. et al. Multi-walled carbon nanotube-reinforced magnesium alloy composites. Script. Mater.58, 267–270 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu, L., Lim, C. Y. H. & Yeong, W. M. Effect of reinforcements on strength of Mg9% Al composites. Compos. Struct.66, 41–45 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gu, X. et al. Microstructure, mechanical property, bio-corrosion and cytotoxicity evaluations of Mg/HA composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. C30, 827–832. 10.1016/j.msec.2010.03.016 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suryanarayana, C. Mechanical alloying and milling. Prog. Mater. Sci.46, 1–184 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilman, P. S. & Benjamin, J. S. Mechanical alloying. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci.13, 279–300 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lloyd, D. J. Particle reinforced aluminium and magnesium matrix composites. Int. Mater. Rev.39, 1–23 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tszeng, T. C. The effects of particle clustering on the mechanical behavior of particle reinforced composites. Compos. Part B Eng.29, 299–308 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Habibnejad-Korayem, M., Mahmudi, R. & Poole, W. J. Enhanced properties of Mgbased nanocomposites reinforced with Al2O3 nano-particles. Mater. Sci. Eng. A519, 198–203 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goh, C. S., Wei, J., Lee, L. C. & Gupta, M. Development of novel carbon nanotube reinforced magnesium nanocomposites using the powder metallurgy technique. Nanotechnology17, 7–12 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hassan, S. F. & Gupta, M. Development of ductile magnesium composite materials using titanium as reinforcement. J. Alloys Compd.345, 246–251 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong, W. L. E. & Gupta, M. Development of Mg/Cu nanocomposites using microwave assisted rapid sintering. Compos. Sci. Technol.67, 1541–1552 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hassan, S. F. & Gupta, M. Development of high performance magnesium nanocomposites using nano-Al2 O3 as reinforcement. Mater. Sci. Eng. A392, 163–168 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xi, Y. L., Chai, D. L., Zhang, W. X. & Zhou, J. E. Titanium alloy reinforced magnesium matrix composite with improved mechanical properties. Scr. Mater.54, 19–23 (2006). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available within the article.