Abstract

Radiation therapy is recognized as an effective modality in the treatment of lung cancer, but radioresistance resulting from prolonged treatment reduces the chances of recovery. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) play a pivotal role in radiotherapy immunity. In this study, we aimed to investigate the mechanism by which miR‐196a‐5p affects radioresistance in lung cancer. The radioresistant lung cancer cell line A549R26–1 was established by radiation treatment. Cancer‐associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and normal fibroblasts (NFs) were observed by microscopy, and the expression levels of CAF‐specific marker proteins were detected by immunofluorescence. The shape of the exosomes was observed by electron microscopy. A CCK‐8 assay was used to detect cell viability, while clone formation assays were used to detect cell proliferative capacity. Flow cytometry was performed to investigate apoptosis. The binding of miR‐196a‐5p and NFKBIA was predicted and further verified by the dual luciferase reporter experiment. qRT–PCR and western blotting were used to detect gene mRNA and protein levels. We found that exosomes secreted by CAFs could enhance lung cancer cell radioresistance. Moreover, miR‐196a‐5p potentially bound to NFKBIA, promoting malignant phenotypes in radioresistant cells. Furthermore, exosomal miR‐196a‐5p derived from CAFs increased radiotherapy immunity in lung cancer. Exosomal miR‐196a‐5p derived from CAFs enhanced radioresistance in lung cancer cells by downregulating NFKBIA, providing a new potential target for the treatment of lung cancer.

Keywords: cancer‐associated fibroblasts, lung cancer, miR‐196a‐5p, NFKBIA, radioresistance

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CAF

cancer‐associated fibroblasts

- CAF‐derived exosomes

CAF‐exo

- CCK‐8

cell counting kit‐8

- DAPI

4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole

- EMT

epithelial‐mesenchymal transition

- FAP

fibroblast activation protein

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FSP‐1

fibroblast specific protein

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase

- microRNAs

miRNAs

- NFKBIA

NF‐κB inhibitor alpha

- NFs

normal fibroblasts

- NF‐κB

nuclear factor kappa‐B

- NTA

nanoparticle tracking analysis

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PVDF

poly (vinylidene fluoride)

- qRT–PCR

quantitative reverse transcription PCR

- TEM

transmission electron microscope

- α‐SMA

α‐smooth muscle actin

1. INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is one of the main causes of cancer death worldwide. Therefore, how to better prevent and treat lung cancer has consistently been the focus of research. 1 Most lung cancer patients are at an advanced stage when they are first diagnosed, and most of them have a poor 5‐year survival rate. 2 In recent years, with the development and improvement of medical technology, radiotherapy has gradually become regarded as a standard preoperative treatment method, and its effect on reducing local recurrence of cancer has made it widely used in the field of treatment in lung cancer. However, the treatment cycle of cancer is relatively long, and frequent radiotherapy increases the radioresistance of lung cancer cells and greatly reduces the efficacy. 3 This complex issue has also become an important topic of lung cancer research.

Previous studies have shown that cancer‐associated fibroblasts (CAFs) can promote tumorigenesis and malignant behavior of tumors, such as enhancing the proliferation and drug resistance of cancer cells. 4 Therefore, CAFs have been considered an anticancer therapeutic target worthy of in‐depth study. There is evidence that CAF‐derived exosomes (CAF‐exo) are involved in regulating the reflex resistance of tumor cells. 5 However, the role of CAFs in radiotherapy of lung cancer is still unclear.

miR‐196a‐5p has been confirmed to act as a tumor‐promoting factor, promoting the migration, invasion and epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT) of lung cancer cells. More importantly, the expression of miR‐196a‐5p is elevated in lung CAFs, suggesting that it is closely related to the development of lung cancer. 6 Although the role of miR‐196a‐5p in the radioresistance of lung cancer cells has not yet been reported, deletion of miR‐196a‐5p can inhibit the metastasis of non‐small cell lung cancer. 7 The authors showed that miR‐196a‐5p is involved in the development of lung cancer, and it is worth further studying the role of miR‐196a‐5p in the radioresistance of lung cancer cells.

Through the online bioinformatics website, we predicted that there is a possible binding site between miR‐196a‐5p and nuclear factor kappa‐B (NF‐κB) inhibitor alpha (NFKBIA), and there are few research reports on the radioresistance of NFKBIA in lung cancer. Previous studies have found that reduced expression of NFKBIA promotes radioresistance to some extent in many cancers, such as breast cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma. 8 , 9 As an important factor in the NF‐κB signaling pathway, exploring whether NFKBIA can affect the radioresistance of lung cancer cells is of great significance for developing new therapeutic directions.

Taken together, we hypothesize that CAF exosomal miR‐196a‐5p promotes radioresistance in lung cancer cells by targeting NFKBIA.

2. METHODS

2.1. Cell culture and treatment

As described previously, 10 A549 cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in RPMI‐1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) in a humidified environment containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. To establish the radioresistant cell line (A549R26–1), parental A549 cells (A549P; cell passage number: 3) were treated repeatedly with 2–6 Gy intensity radiation for 4–5 weeks. After each radiation treatment, the surviving cells were allowed to recover before the next radiation treatment. Treatment was stopped when the total radiation dose received by the cells reached 26 Gy, and cell resistance was detected by CCK‐8, colony formation, and flow cytometry assays.

2.2. CAF isolation and identification

Lung cancer tissue and adjacent normal tissue samples were collected from The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine. The patients had not received radiation therapy before tumor resection, and for the collection of tissue samples, we obtained the consent of the relevant organizations, including the ethics committee of the hospital, and the patients confirmed and signed the informed consent form. The obtained samples were cut into 1–2 mm diameter pieces, digested with trypsin (Gibco) and 0.5% collagenase (Gibco), and filtered. CAFs and normal fibroblasts (NFs) were isolated using human anti‐fibroblast microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The isolated cells were cultured in F12K medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco) at 37°C and 5% CO2, and the medium was replaced after 24 h. 11

For CAF identification, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and incubated with 0.1% Triton X‐100 for 30 min. After that, cells were blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin for 1 h, followed by overnight incubation with primary antibody at 4 °C and incubation with secondary antibody for 1 h. Subsequently, cells were stained with DAPI for 5 min and photographed with a fluorescence microscope. 12 The primary antibodies used for the experiments were α‐SMA (ab124964, 1:300, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), FSP‐1 (ab197896, 1:250, Abcam), and FAP (#66562, 1:100, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), and the secondary antibody was goat anti‐rabbit IgG (ab150080, 1:500, Abcam).

2.3. Exosome isolation and identification

Isolation and identification of exosomes were performed according to established research methods. 13 , 14 Briefly, exosomes were separated by a 0.22 μm PVDF filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) with differential centrifugation. After separation, the morphological characteristics of the exosomes were observed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the size and concentration of the exosomes were measured by a NanoSight NS300 instrument and nanoparticle tracking analysis (NAT; Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern, UK). Furthermore, the expression of calnexin (#2679, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), CD81 (ab109201, 1:4000, Abcam), CD63 (ab134045, 1:5000, Abcam), and TSG101 (ab125011, 1:2000, Abcam) was detected by western blotting to identify the expression of marker proteins on the surface of exosomes.

2.4. Exosome internalization

The isolated exosomes were resuspended in a mixture of 4 μL of the fluorescent dye PKH67 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 1 mL of Diluent C and incubated for 4 min at room temperature. An equal volume of FBS was added to terminate the reaction before the rejection reaction occurred. Next, the exosomes were washed with exosome‐free RPMI‐1640 medium twice, and the labeled exosomes were resuspended in 1× PBS and set aside. A549R26–1 cells with 80% fusion were cocultured with the above‐labeled exosomes for 12 h, after which they were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. After fixation, the cells were washed three times with PBS and stained with DAPI for 5 min. After washing the stained cells twice with PBS, the uptake of labeled exosomes by A549R26–1 cells was observed under a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). 15

2.5. Cell transfection

The vectors and miRNA mimics used in cell transfection were synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). Cells were transfected according to the instructions of the Lipofectamine 3000 kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). miR‐196a‐5p was overexpressed in A549R26–1 cells by transfection with miR‐196a‐5p mimics for 48 h, while mimic NC was used as a negative control; NFKBIA was overexpressed in A549R26–1 cells by transfection with NFKBIA overexpression vector for 48 h, while oe‐NC was used as a negative control. 16

2.6. Cell counting kit‐8 (CCK‐8) assay

Cells were inoculated in 96‐well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well according to previous studies, 17 and the cells underwent treatment based on the corresponding steps. CCK‐8 was added to the wells and incubated for 3 h, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an enzyme marker.

2.7. Colony formation assay

The cells were inoculated in 6‐well plates at a density of 1 × 103 cells/well and cultured for 24 h. Then, the cells were exposed to different doses of radiation and incubated for 10–14 days until the colonies were visible. After that, colonies were fixed with 10% formaldehyde for 40 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min. The number of generated colonies was counted. 18

2.8. Flow cytometry assay

Cells were first digested with trypsin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and resuspended 48 h after cell treatment as described previously. 19 Subsequently, approximately 1 × 106 cells were mixed with 5 μL FITC‐Annexin V and 5 μL PI and incubated in a light‐proof location for 15 min. After the reaction was completed, the mixture was diluted with 400 μL of 1× Binging Buffer and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

2.9. Quantitative real‐time PCR

Quantitative real‐time PCR (qRT–PCR) assays were performed using the methods mentioned in previous studies. 20 In summary, total RNA was extracted by TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and quantified. Next, reverse transcription was performed with the SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Invitrogen), and amplification was performed with SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ II PCR Amplification Reagent (Takara, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The relative expression levels of the genes were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method. The internal reference genes used in the experiments were U6 and GAPDH. The primer sequences of the genes are as follows:

miR‐196a‐5p forward: 5′‐CCGGCTAGGTAGTTTCATGTT‐3′,

miR‐196a‐5p reverse: 5′‐CGGCCCAGTGTTCAGACTAC‐3′;

U6 forward: 5′‐CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA‐3′,

U6 reverse: 5′‐AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT‐3′;

NFKBIA forward: 5′‐ATGTGGACGACCGCCACGACA‐3′,

NFKBIA reverse: 5′‐ATGGCCAAGTGCAGGAACGAGTC‐3′;

GAPDH forward: 5′‐AACGGATTTGGTCGTATTGGG‐3′,

GAPDH reverse: 5′‐CGCTCCTGGAAGATGGTGAT‐3′.

2.10. Western blot

The expression levels of proteins were detected by western blot. 21 Total proteins were isolated from treated cells, and nuclear proteins were extracted from cells using a Nucleoprotein Protein Extraction Kit (C500009‐0050, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). For nuclear protein extraction, cells were incubated with hypotonic buffer with a phosphatase inhibitor for 10 min on ice, followed by centrifugation at 800 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, after which the precipitates were resuspended in hypotonic buffer. The resuspension was centrifuged at 2500 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, and then the precipitates were resuspended in lysis buffer with a phosphatase inhibitor on ice for 20 min. The lysis buffer was centrifuged at 20000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant containing nuclear proteins was collected for western blotting. Then, the protein (total protein or nuclear protein) samples were subjected to 10% SDS–PAGE, followed by transfer to PVDF membranes (Millipore). Then, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies: anti‐NFKBIA (ab32518, 1:5000, Abcam), anti‐p65 (ab32536, 1:4000, Abcam), anti‐Lamin B (ab133741, 1:10000, Abcam), and GAPDH (ab9485, 1:2500, Abcam) overnight at 4°C. After washing, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h and visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Abcam). The bands were photographed and analyzed using ImageJ.

2.11. Dual‐luciferase reporter assay

The targeting relationship between miR‐196a‐5p and NFKBIA was examined using a dual luciferase assay. Based on previous studies, 22 plasmids containing wild‐type (WT) and mutant (MUT) NFKBIA 3′‐UTR fragments were synthesized and cotransfected with mimics of miR‐196a‐5p or negative controls according to the instructions of the Lipofectamine 3000 kit (Invitrogen) into cells. After 48 h of transfection, luciferase activity was measured using the Dual‐Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Firefly luciferase activity was quantified using sea kidney luciferase activity as a standard.

2.12. Statistical analyses

All experiments were repeated three times, and the experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Data conforming to homogeneity of variance and normal distribution were compared between two groups using Student's t‐test, while comparisons between multiple groups were performed using one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey's post hoc test. All data were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

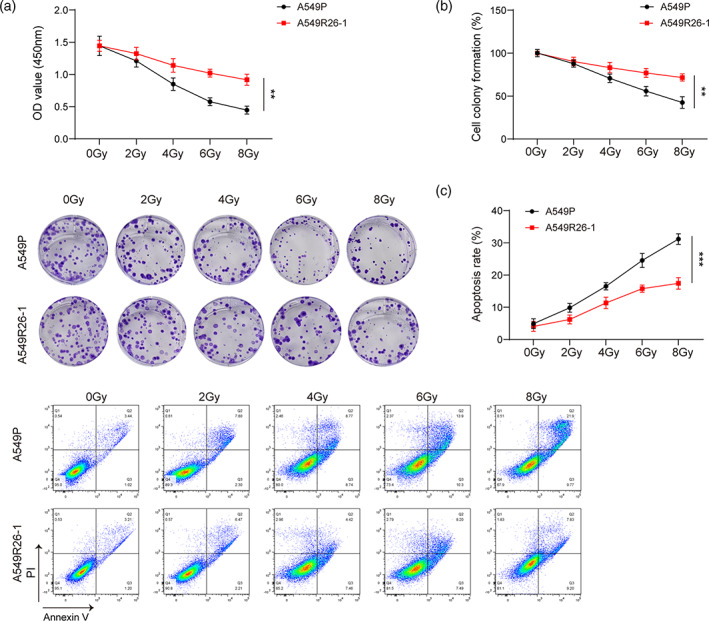

3.1. Radioresistant lung cancer cells have stronger radioresistance ability than parental cells

We first established the radioresistant cell line A549R26‐1 and verified its radiation resistance through biological experiments. Upon treatment with the same radiation dose, the CCK‐8 assay showed that the cell viability of radioresistant A549R26‐1 cells was significantly higher than that of parental A549 cells (Figure 1A). The clone formation assay showed that A549R26‐1 cells had stronger proliferation ability than A549P cells (Figure 1B). The flow cytometry assay showed that the survival ability of A549R26‐1 cells was stronger than that of A549P cells (Figure 1C). Thus, we determined that radiotherapy‐resistant A549R26‐1 cells had been successfully established, which have stronger resistance to radiation than the parental cells.

FIGURE 1.

Radioresistant lung cancer cells have stronger radioresistance abilities than parental cells. Parental A549 cells (A549P) and a radioresistant cell line (A549R26‐1) were treated with 2–8 Gy intensity radiation. (A) Cell viability of A549R26‐1 and A549P cells was determined by CCK‐8 assay, **p < 0.01. (B) The proliferation ability of A549R26‐1 and A549P cells was assessed by clone formation assay, **p < 0.01. (C) Apoptosis of A549R26‐1 and A549P cells was determined by flow cytometry, ***p < 0.001. Experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation; Student's t‐test was used for comparisons between two groups.

3.2. CAF‐exo promote radioresistance in lung cancer cells

To explore the effect of CAF‐exo on the radioresistance of lung cancer cells, we first identified isolated CAFs. Under the microscope, both CAFs and NFs were elongated and fibrous. After immunofluorescence staining, high expression of the CAF‐specific marker proteins α‐SMA, FAP and FSP1 was observed (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 2.

CAF‐exo promote radioresistance in lung cancer cells. (A) CAFs and NFs were observed by microscopy, and the expression levels of α‐SMA, FAP, and FSP1 were detected by immunofluorescence staining. (B) The structure of exosomes was observed by TEM. (C) The diameter of exosomes was detected by NTA. (D) The expression levels of CD63, CD81, TSG101 and calnexin were detected by western blot. (E) A549R26‐1 cells were cocultured with PKH67‐labeled exosomes for 12 h, and the uptake of exosomes by A549R26‐1 cells was detected. (F) A549R26‐1 cells were treated with NF‐exo or CAF‐exo under radiation at 0–8 Gy, and viability was determined by CCK‐8 assay, **p < 0.01. (G) The proliferation ability of A549R26‐1 cells treated with NF‐exo or CAF‐exo under 8 Gy radiation was determined by clone formation assay, ***p < 0.001. (H) Apoptosis in A549R26‐1 cells treated with NF‐exo or CAF‐exo under 8 Gy radiation was determined by flow cytometry, **p < 0.01. Experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation; ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used for comparisons among multiple groups.

After isolating CAF‐exo, we identified the exosomes. Under TEM, we observed that the isolated vesicles were round or oval in shape with a disc‐like structure and complete capsule (Figure 2B), and the average particle size of the isolated vesicles was determined via NTA analysis (Figure 2C). Western blot analysis showed that the isolated vesicles could express the exosome surface marker proteins CD63, CD81, and TSG101, while the negative marker calnexin was not significantly expressed (Figure 2D). These results showed that CAF‐exo were successfully isolated.

Next, we observed the cellular internalization of exosomes by PKH67 staining. The results showed that no fluorescence signal was detected in the PBS group, but green fluorescence appeared in the cytoplasm of A549R26‐1 cells cocultured with CAF‐exo or NF‐exo, and there was no significant difference in the fluorescence intensity between the two cells (Figure 2E). Under the same radiation dose (8 Gy), CAF‐exo significantly promoted cell viability and proliferation but inhibited apoptosis in A549R26‐1 cells (Figure 2F–H). Taken together, the results show that CAF‐exo enhance radioresistance in lung cancer cells.

3.3. NFKBIA is identified as a direct target gene of miR‐196a‐5p

Several previous studies have demonstrated that miR‐196a‐5p and NFKBIA play a certain role in the development of lung cancer, but few studies have proven the relationship between the two molecules. We first examined their expression in different cell lines. qRT–PCR assays showed that the expression of miR‐196a‐5p in A549R26–1 cells was abnormally increased, and the mRNA expression of NFKBIA was decreased (Figure 3A). The western blot results also showed that the protein expression of NFKBIA was inhibited (Figure 3B). Furthermore, we predicted the possible binding sites between miR‐196a‐5p and NFKBIA through the bioinformatics website starBase (https://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/), and the results of the dual‐luciferase reporter experiment confirmed that NFKBIA was a target of miR‐196a‐5p (Figure 3C). Moreover, miR‐196a‐5p suppressed the mRNA and protein expression of NFKBIA (Figure 3D,E).

FIGURE 3.

NFKBIA is identified as a direct target gene of miR‐196a‐5p. (A) The RNA levels of miR‐196a‐5p and NFKBIA were measured by qRT–PCR, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. (B) The protein level of NFKBIA was detected by western blot, **p < 0.01. (C) StarBase predicted the binding site of miR‐196a‐5p to NFKBIA, and the binding was confirmed by dual luciferase reporter assay in cells after transfection with corresponding plasmids for 48 h, **p < 0.01. (D) The RNA levels of miR‐196a‐5p and NFKBIA were measured by qRT–PCR in cells after transfection with mimic NC and miR‐196a‐5p mimic for 48 h, ***p < 0.001. (E) The protein level of NFKBIA was detected by western blot in cells after transfection with mimic NC and miR‐196a‐5p mimic for 48 h, **p < 0.01. Experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation; Student's t‐test was used for comparisons between two groups.

3.4. miR‐196a‐5p promotes radioresistance in lung cancer cells

The above experiments showed that miR‐196a‐5p is more highly expressed in A549R26‐1 cells, but it was not determined whether this was directly related to the radioresistance of lung cancer cells. Therefore, we examined cell survival by CCK‐8 assay, clone formation assay, and flow cytometry. The results showed that miR‐196a‐5p overexpression enhanced the viability of A549R26‐1 cells, promoted cell proliferation, and inhibited cell apoptosis (Figure 4A–C). The above results demonstrate that overexpressed miR‐196a‐5p can promote the resistance of lung cancer cells to radiotherapy.

FIGURE 4.

miR‐196a‐5p promotes radioresistance in lung cancer cells. (A) Cells were transfected with mimic NC or miR‐196a‐5p mimic for 48 h under radiation at 0–8 Gy, and cell viability was determined by CCK‐8 assay, *p < 0.05. (B) Cell proliferation ability was determined by clone formation assay after transfection with mimic NC or miR‐196a‐5p mimic under 8 Gy radiation, ***p < 0.001. (C) Cell apoptosis was determined by flow cytometry after transfection with mimic NC or miR‐196a‐5p mimic under 8 Gy radiation, **p < 0.01. Experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation; Student's t‐test was used for comparisons between two groups.

3.5. miR‐196a‐5p increases radioresistance in lung cancer cells by inhibiting NFKBIA and activating the NF‐κB pathway

Next, we further investigated the mechanism by which miR‐196a‐5p regulates cellular radioresistance. miR‐196a‐5p or NFKBIA was overexpressed in A549R26‐1 cells, and the transfection results were confirmed by qRT–PCR and western blotting (Figure 5A,B). It can be seen from the same biological experiments that overexpressed NFKBIA can attenuate the cell viability and proliferation ability of A549R26‐1 cells and simultaneously promote cell apoptosis. Overexpression of NFKBIA also reversed the effect of overexpression of miR‐196a‐5p on enhancing the radioresistance of lung cancer cells (Figure 5C–E). We used GAPDH as the cytosolic loading control. Through western blotting, we found that GAPDH was not present in the nuclear extracts, suggesting that the samples were not contaminated with cytosolic extracts (Figure 5F). In addition, NFKBIA overexpression decreased nuclear p65 levels and partly reversed the miR‐196a‐5p‐induced increase in nuclear p65 levels (Figure 5F). Our results show that miR‐196a‐5p increases radioresistance in lung cancer cells by inhibiting NFKBIA and activating the NF‐κB pathway.

FIGURE 5.

miR‐196a‐5p increases radioresistance in lung cancer cells by inhibiting NFKBIA and activating the NF‐κB pathway. (A) The mRNA level of NFKBIA was measured by qRT–PCR in cells transfected with oe‐NC or oe‐NFKBIA for 48 h, ***p < 0.001. (B) The protein level of NFKBIA was detected by western blot in cells transfected with oe‐NC or oe‐NFKBIA for 48 h, **p < 0.01. Experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation; Student's t‐test was used for comparisons between two groups. (C) Cell viability was determined by CCK‐8 assay in cells transfected with oe‐NC and/or miR‐196a‐5p mimic or oe‐NFKBIA and/or miR‐196a‐5p mimic for 48 h under radiation with 0–8 Gy, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. (D) Cell proliferation ability was determined by clone formation assay in cells transfected with oe‐NC and/or miR‐196a‐5p mimic or oe‐NFKBIA and/or miR‐196a‐5p mimic for 48 h under radiation with 8 Gy, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. (E) Cell apoptosis was determined by flow cytometry in cells transfected with oe‐NC and/or miR‐196a‐5p mimic or oe‐NFKBIA and/or miR‐196a‐5p mimic for 48 h under 8 Gy radiation, ***p < 0.001. (F) The protein level of nuclear p65 was detected by western blot, ***p < 0.001. Experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation; ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used for comparisons among multiple groups.

3.6. CAF‐derived exosomal miR‐196a‐5p increases radioresistance in lung cancer cells

Finally, we experimentally verified the effect of CAFs on the radioresistance of lung cancer cells via exosome‐derived miR‐196a‐5p. The experimental results showed that miR‐196a‐5p was highly expressed in both CAFs and CAF‐exo (Figure 6A). After overexpression of miR‐196a‐5p in CAFs, exosomes were extracted, and increased expression of miR‐196a‐5p was detected in the exosomes, indicating that the cells were successfully transfected (Figure 6B). Compared with CAF‐exo, miR‐196a‐5p‐overexpressing CAF‐exo significantly improved cell viability and proliferation but inhibited cell apoptosis (Figure 6C–E). These results demonstrated that CAF‐derived exosomal miR‐196a‐5p strengthens the radioresistance of lung cancer cells.

FIGURE 6.

CAF‐derived exosomal miR‐196a‐5p increases radioresistance in lung cancer cells. (A) miR‐196a‐5p expression in different groups was measured by qRT–PCR, ***P < 0.001. Experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation; Student's t‐test was used for comparisons between two groups. (B) miR‐196a‐5p expression was measured by qRT–PCR in cells treated with CAF‐exo or mimic NC/miR‐196a‐5p mimic‐transfected CAF‐exo, ***p < 0.001. (C) Cell viability was determined by CCK‐8 assay in cells treated with CAF‐exo‐ and mimic NC/miR‐196a‐5p mimic‐transfected CAF‐exo under radiation at 0–8 Gy, ***p < 0.001. (D) Cell proliferation ability was determined by clone formation assay in cells treated with CAF‐exo‐ and mimic NC/miR‐196a‐5p mimic‐transfected CAF‐exo under 8 Gy radiation, ***p < 0.001. (E) Cell apoptosis was determined by flow cytometry in cells treated with CAF‐exo or mimic NC/miR‐196a‐5p mimic‐transfected CAF‐exo under 8 Gy radiation, ***p < 0.001. Experimental data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation; ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used for comparisons among multiple groups. (F) CAF‐derived exosomal miR‐196a‐5p activates NF‐κB by targeting NFKBIA and promotes lung cancer cell proliferation while inhibiting apoptosis, thereby enhancing lung cancer cell radioresistance.

4. DISCUSSION

Due to its large patient population and high mortality rate, lung cancer has prompted researchers to continue to investigate new lung cancer treatment strategies. Radiation therapy is a widely accepted and effective treatment method. Targeted radiotherapy has a significant tumor control effect and low toxicity and is a powerful treatment strategy in the early stage of cancer. 23 However, continued radiation therapy makes lung cancer cells resistant and increases the ability of cancer cells to survive. 24 To improve the effect of radiotherapy, new combination drugs or therapeutic targets should be discovered and applied. In this study, we found that CAF‐exo could enhance the radioresistance of the radioresistant lung cancer cell line A549R26‐1. Similarly, the high expression of miR‐196a‐5p enhanced the radioresistance of lung cancer cells and improved cell viability and proliferation. The expression level of NFKBIA, as a downstream regulatory protein of miR‐196a‐5p, was also inhibited. However, we found that overexpressed NFKBIA could reverse the effects of miR‐196a‐5p on radiotherapy immunity. This may be a new therapeutic direction worthy of further research.

CAFs have been a hot topic of research in recent years. Most investigators have found that CAFs play an important role in the development and resistance of various cancers. For example, in non‐small cell lung cancer, CAFs have been shown to promote the migration and invasion of cancer cells through the AKT/eNOS pathway. 25 CAF‐exo have also been demonstrated to have a similar effect. 26 Interestingly, CAFs have also been found to enhance the radioresistance of cancer cells by secreting related mediators, 27 but little research has been conducted in the lung cancer field. In this study, we isolated CAFs and extracted their exosomes to study the effects of CAF‐exo on the radioresistance of lung cancer. Our findings showed that when cancer cells were cultured in the presence of CAF‐exo, their radioresistance was significantly enhanced, thus making cancer cells more viable and increasing their survival ability. Based on this, we believe that taking some therapeutic measures to inhibit the proliferation and differentiation of CAFs may also improve the effect of radiotherapy for lung cancer.

Numerous studies in recent years have shown that miRNAs play regulatory roles in the progression of various diseases, including various cancers. miR‐196a‐5p has been found to be upregulated in breast and bladder cancers, and this upregulation contributes to the chemotherapy resistance of cancers. 28 , 29 However, there is little research on the role of miR‐196a‐5p in cancer radioresistance. As an important regulatory gene in the NF‐κB signaling pathway, NFKBIA is closely related to the radioresistance of cancer. 30 However, the role of NFKBIA in the radioresistance of lung cancer cells is unknown. We conducted preliminary experiments and found that NFKBIA was a target of miR‐196a‐5p and that miR‐196a‐5p can inhibit the expression of NFKBIA to activate the NF‐κB pathway and improve the radioresistance of lung cancer cells. In addition, when the expression of NFKBIA was elevated, the enhanced effect of miR‐196a‐5p on the radioresistance of lung cancer cells was reversed. Based on this result, we believe that miR‐196a‐5p/NFKBIA may be an important pathway affecting the radioresistance of lung cancer cells.

Almost all types of cells can secrete exosomes, and the contents of exosomes can regulate the occurrence and development of other physiological processes. 31 In colorectal cancer, a variety of microRNAs and other noncoding RNAs contained in exosomes were involved in the development of cancer. They improved the proliferation and metastasis ability of cancer cells and even enhanced the radiosensitivity of cancer cells. 32 , 33 In our study, we found that CAF‐exo can promote the development of cancer cells and enhance radioresistance, and the high expression of miR‐196a‐5p in CAF‐exo makes this effect more significant. How to reduce the secretion of CAF‐exo or inhibit the expression of miR‐196a‐5p needs to be further studied.

5. CONCLUSION

The high mortality and low survival rate of lung cancer have always been challenges that medical researchers are eager to overcome. Although radiation therapy can have a beneficial effect in the early stage of lung cancer treatment, long‐term radiation therapy can make cancer cells resistant. Here, we found that CAF‐derived exosomal miR‐196a‐5p could increase lung cancer cell viability and reduce radiosensitivity by inhibiting NFKBIA, thereby activating the NF‐κB pathway (Figure 6F). Our study identified a novel signaling pathway that enhances the radioresistance of lung cancer cells, providing new inspiration for exploring new lung cancer treatments.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Yao F, Shi W, Fang F, Lv M‐Y, Xu M, Wu S‐Y, et al. Exosomal miR‐196a‐5p enhances radioresistance in lung cancer cells by downregulating NFKBIA . Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2023;39(6):554–564. 10.1002/kjm2.12673

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhang F, Sang Y, Chen D, Wu X, Wang X, Yang W, et al. M2 macrophage‐derived exosomal long non‐coding RNA AGAP2‐AS1 enhances radiotherapy immunity in lung cancer by reducing microRNA‐296 and elevating NOTCH2. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(5):467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thawani R, McLane M, Beig N, Ghose S, Prasanna P, Velcheti V, et al. Radiomics and radiogenomics in lung cancer: a review for the clinician. Lung Cancer. 2018;115:34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shi JG, Shao HJ, Jiang FE, Huang YD. Role of radiation therapy in lung cancer management ‐ a review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20(15):3217–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen X, Liu J, Zhang Q, Liu B, Cheng Y, Zhang Y, et al. Exosome‐mediated transfer of miR‐93‐5p from cancer‐associated fibroblasts confer radioresistance in colorectal cancer cells by downregulating FOXA1 and upregulating TGFB3. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39(1):65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang H, Hua Y, Jiang Z, Yue J, Shi M, Zhen X, et al. Cancer‐associated fibroblast‐promoted LncRNA DNM3OS confers Radioresistance by regulating DNA damage response in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(6):1989–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee S, Hong JH, Kim JS, Yoon JS, Chun SH, Hong SA, et al. Cancer‐associated fibroblasts activated by miR‐196a promote the migration and invasion of lung cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2021;508:92–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li X, Chen Z, Ni Y, Bian C, Huang J, Chen L, et al. Tumor‐associated macrophages secret exosomal miR‐155 and miR‐196a‐5p to promote metastasis of non‐small‐cell lung cancer [published correction appears in Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021;10(10):4047–4048]. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021;10(3):1338–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Luo M, Ding L, Li Q, Yao H. miR‐668 enhances the radioresistance of human breast cancer cell by targeting IκBα. Breast Cancer. 2017;24(5):673–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shen ZT, Chen Y, Huang GC, Zhu XX, Wang R, Chen LB. Aurora‐a confers radioresistance in human hepatocellular carcinoma by activating NF‐κB signaling pathway. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhu R, Xue X, Shen M, Tsai Y, Keng PC, Chen Y, et al. NFκB and TNFα as individual key molecules associated with the cisplatin‐resistance and radioresistance of lung cancer. Exp Cell Res. 2019;374(1):181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang Y, Lan W, Xu M, Song J, Mao J, Li C, et al. Cancer‐associated fibroblast‐derived SDF‐1 induces epithelial‐mesenchymal transition of lung adenocarcinoma via CXCR4/β‐catenin/PPARδ signalling. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(2):214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen X, Liu Y, Zhang Q, Liu B, Cheng Y, Zhang Y, et al. Exosomal miR‐590‐3p derived from cancer‐associated fibroblasts confers radioresistance in colorectal cancer. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020;24:113–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Qin X, Guo H, Wang X, Zhu X, Yan M, Wang X, et al. Exosomal miR‐196a derived from cancer‐associated fibroblasts confers cisplatin resistance in head and neck cancer through targeting CDKN1B and ING5. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu C, Wang M, Huang Q, Guo Y, Gong H, Hu C, et al. Aberrant expression profiles and bioinformatic analysis of CAF‐derived exosomal miRNAs from three moderately differentiated supraglottic LSCC patients. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022;36(1):e24108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang X, Sai B, Wang F, Wang L, Wang Y, Zheng L, et al. Hypoxic BMSC‐derived exosomal miRNAs promote metastasis of lung cancer cells via STAT3‐induced EMT. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu G, Sun J, Yang ZF, Zhou C, Zhou PY, Guan RY, et al. Cancer‐associated fibroblast‐derived CXCL11 modulates hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and tumor metastasis through the circUBAP2/miR‐4756/IFIT1/3 axis. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(3):260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dou D, Ren X, Han M, Xu X, Ge X, Gu Y, et al. Cancer‐associated fibroblasts‐derived exosomes suppress immune cell function in breast cancer via the miR‐92/PD‐L1 pathway. Front Immunol. 2020;11:2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18. Shan G, Gu J, Zhou D, Li L, Cheng W, Wang Y, et al. Cancer‐associated fibroblast‐secreted exosomal miR‐423‐5p promotes chemotherapy resistance in prostate cancer by targeting GREM2 through the TGF‐β signaling pathway. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52(11):1809–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang W, Jiang Q, Wu J, Tang W, Xu M. Upregulation of bone morphogenetic protein 2 (Bmp2) in dorsal root ganglion in a rat model of bone cancer pain. Mol Pain. 2019;15:1744806918824250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang L, Wei Y, Yan Y, Wang H, Yang J, Zheng Z, et al. CircDOCK1 suppresses cell apoptosis via inhibition of miR‐196a‐5p by targeting BIRC3 in OSCC. Oncol Rep. 2018;39(3):951–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang H, Deng T, Liu R, Ning T, Yang H, Liu D, et al. CAF secreted miR‐522 suppresses ferroptosis and promotes acquired chemo‐resistance in gastric cancer. Mol Cancer. 2020;19(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen B, Sang Y, Song X, Zhang D, Wang L, Zhao W, et al. Exosomal miR‐500a‐5p derived from cancer‐associated fibroblasts promotes breast cancer cell proliferation and metastasis through targeting USP28. Theranostics. 2021;11(8):3932–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hirsch FR, Scagliotti GV, Mulshine JL, Kwon R, Curran WJ Jr, Wu YL, et al. Lung cancer: current therapies and new targeted treatments. Lancet. 2017;389(10066):299–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li L, Zhu T, Gao YF, Zheng W, Wang CJ, Xiao L, et al. Targeting DNA damage response in the radio(chemo)therapy of non‐small cell lung cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(6):839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guo X, Chen M, Cao L, Hu Y, Li X, Zhang Q, et al. Cancer‐associated fibroblasts promote migration and invasion of non‐small cell lung cancer cells via miR‐101‐3p mediated VEGFA secretion and AKT/eNOS pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:764151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yang F, Yan Y, Yang Y, Hong X, Wang M, Yang Z, et al. MiR‐210 in exosomes derived from CAFs promotes non‐small cell lung cancer migration and invasion through PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway. Cell Signal. 2020;73:109675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Piper M, Mueller AC, Karam SD. The interplay between cancer associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the context of radiation therapy. Mol Carcinog. 2020;59(7):754–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang YW, Zhang W, Ma R. Bioinformatic identification of chemoresistance‐associated microRNAs in breast cancer based on microarray data. Oncol Rep. 2018;39(3):1003–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pan J, Li X, Wu W, Xue M, Hou H, Zhai W, et al. Long non‐coding RNA UCA1 promotes cisplatin/gemcitabine resistance through CREB modulating miR‐196a‐5p in bladder cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2016;382(1):64–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Barisic S, Schmidt C, Walczak H, Kulms D. Tyrosine phosphatase inhibition triggers sustained canonical serine‐dependent NFkappaB activation via Src‐dependent blockade of PP2A. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80(4):439–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vakhshiteh F, Hassani S, Momenifar N, Pakdaman F. Exosomal circRNAs: new players in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1):483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li L, Jiang Z, Zou X, Hao T. Exosomal circ_IFT80 enhances tumorigenesis and suppresses Radiosensitivity in colorectal cancer by regulating miR‐296‐5p/MSI1 Axis. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:1929–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sun T, Yin YF, Jin HG, Liu HR, Tian WC. Exosomal microRNA‐19b targets FBXW7 to promote colorectal cancer stem cell stemness and induce resistance to radiotherapy. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2022;38(2):108–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]