Abstract

The interleukin‐23 (IL‐23)/IL‐17 immune axis has been linked to the pathology of psoriasis, but how this axis contributes to skin inflammation in this disease remains unclear. We measured inflammatory cytokines associated with the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis in the serum of patients with psoriasis using enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays. Psoriasis was induced in male C57BL/6J mice using imiquimod (IMQ) cream, and animals received intraperitoneal injections of recombinant mouse anti‐IL‐23A or anti‐IL‐17A antibodies for 7 days. The potential effects of the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis on skin inflammation were assessed based on pathology scoring, hematoxylin–eosin staining of skin samples, and quantitation of inflammatory cytokines. Western blotting was used to evaluate levels of the following factors in skin: ACT1, TRAF6, TAK1, NF‐κB, and pNF‐κB. The serum of psoriasis patients showed elevated levels of several cytokines involved in the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis: IL‐2, IL‐4, IL‐8, IL‐12, IL‐17, IL‐22, IL‐23, and interferon‐γ. Levels of IL‐23p19 and IL‐17 were increased in serum and skin of IMQ‐treated mice, while ACT1, TRAF6, TAK1, NF‐κB, and pNF‐κB were upregulated in the skin. A large proportion of NF‐κB p65 localized in nucleus of involucrin+ cells in the epidermis and in F4/80+ cells of the dermis of psoriatic lesional skin. Treating these animals with anti‐IL‐23 or anti‐IL‐17 antibodies improved pathological score and immune imbalance, mitigated skin inflammation and downregulated ACT1, TRAF6, TAK1, NF‐κB, and pNF‐κB in skin. Our results suggest that skin inflammation mediated by the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis in psoriasis involves activation of the ACT1/TRAF6/TAK1/NF‐κB pathway in keratinocytes and macrophage.

Keywords: interleukin 17, interleukin 23, NF‐κB, psoriasis, skin inflammation

Abbreviations

- ACT1

nuclear factor kappa B activation factor 1

- anti‐IL‐17A

recombinant IL‐17A antibody

- anti‐IL‐23A

recombinant IL‐23A antibody

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- IKK

inhibitor of kappa B kinase

- IL

interleukin

- IL‐17R

IL‐17 receptor

- IMQ

imiquimod

- IκB

inhibitor of NF‐κB

- NF‐κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- PASI

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index

- pNF‐κB

phosphorylated NF‐κB

- TAK1

transforming growth factor β‐activated kinase 1

- TBS‐T

triethanolamine buffered saline solution + Tween 20

- TNF‐α

tumor necrosis factor‐α

- TRAF6

tumor necrosis receptor‐associated factor 6

1. BACKGROUND

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by sharply demarcated erythematous and scaly skin lesions. The prevalence of psoriasis varies across countries and ethnic groups, ranging from 0.91% to 8.5% in Western countries, while it is lower in Asian countries, ranging from 0.24% to 0.47%. 1 Thus, psoriasis is a major public health concern worldwide and is challenging to treat because of its complex etiology and long course.

Psoriasis is caused by systemic inflammation related to imbalance between the activities of skin cells such as keratinocytes and endothelial cells, and activities of immune cells such as dendritic cells, T lymphocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages. 2 Psoriasis appears to arise when dendritic cells are activated to produce abundant interleukin (IL)‐23 and IL‐12, which promote the differentiation of T helper cells. This leads in turn to excessive production of the pro‐inflammatory factors IL‐17, IL‐22, and tumor necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α), which induce the abnormal proliferation and apoptosis of keratinocytes. Treatment with antibodies against IL‐23 or IL‐17 can effectively alleviate the pathological symptoms of patients with psoriasis. In these ways, the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis seems to play an important role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. However, how this axis contributes to skin inflammation in the disease remains unclear.

After IL‐17 binds to its receptor, the receptor recruits nuclear factor κB (NF‐κB) activator 1 (ACT1), 3 which binds via its SEF/IL17R domain to tumor necrosis factor receptor‐associated factor 6 (TRAF6), inducing its activation. 3 TRAF6 induces the downstream effector transforming growth factor β activated kinase 1 (TAK1) to activate inhibitor of kappa B kinase (IKK). 4 IKK regulates the activation of NF‐κB by phosphorylating the inhibitor of NF‐κB (IκB). 5 Therefore, we hypothesized that the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis might trigger skin inflammation in psoriasis by activating ACT1‐NF‐κB signaling in the skin.

To test this idea, we first evaluated levels of inflammatory factors associated with the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis in the serum of patients with psoriasis. Then, we established a mouse model of imiquimod (IMQ)‐induced psoriasis and investigated the activation of the ACT1‐NF‐κB pathway in the skin. Finally, we evaluated the effect of the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis on ACT1‐NF‐κB signaling by treating mice with anti‐IL‐23A or anti‐IL‐17A antibodies.

2. RESULTS

2.1. The IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis is activated in patients with psoriasis

We found that compared to controls, patients with psoriasis showed higher levels of serum cytokines associated with dendritic cells (IL‐12 and IL‐23), T cells (IFN‐γ, IL‐2, IL‐4, IL‐12, and IL‐17) and neutrophils (IL‐8). However, there was no significant change in anti‐inflammatory cytokine IL‐10 in serum of psoriasis patients when compared with healthy people (Figure 1). These results suggest that the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis is activated in psoriasis.

FIGURE 1.

Levels of cytokines involved in the interleukin‐23 (IL‐23)/IL‐17 axis are elevated in the serum of patients with psoriasis. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 8). ***p < 0.001 by paired Student's t test.

2.2. Inhibiting IL‐23 or IL‐17 alleviates IMQ‐induced dermatitis in mice

To investigate the molecular mechanisms by which the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis regulates the pathology of psoriasis, we established a model of psoriasis in male C57BL/6J mice and treated the animals with recombinant IL‐23A antibody (anti‐IL‐23A) or IL‐17A antibody (anti‐IL‐17A) for 7 days. IMQ induced a severe psoriatic phenotype with high PASI, and disease worsened with the duration of IMQ treatment (Figure 2A–E). Treatment with either anti‐IL‐23A or anti‐IL‐17A antibody significantly alleviated IMQ‐induced psoriasis‐like symptoms (Figure 2A), including ear erythema (Figure 2B), scales (Figure 2C), thickeness (Figure 2D) and total scores (Figure 2E).

FIGURE 2.

Treatment with anti‐interleukin (IL)‐17 or anti‐IL‐23 antibody alleviates imiquimod (IMQ)‐induced psoriatic symptoms in mice. (A) Representative photographs of ears from mice treated with IMQ or vaseline (control) in the presence or absence of anti‐IL‐17A or anti‐IL‐23A antibody. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) was used as an antibody control. Scale bar, 1 cm. (B–E) Scores of psoriatic severity based on erythema (B), scaling (C), thickness (D), and total scores (E) in the ears of mice treated with IMQ or vaseline in the presence or absence of anti‐IL‐17A or anti‐IL‐23A antibody during 7 days. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (vasiline + IgG = 10, IMQ + IgG = 10, IMQ + anti‐IL23A = 7, IMQ + anti‐IL17A = 7). **p < .01, ***p < .001 versus vaseline + IgG group. # p < .05, ## p < .01, ### p < .001 versus IMQ + IgG group by one‐way analysis of variance with Tukey's multiple‐comparison post hoc test.

IMQ caused an inflammatory thickening of the skin (Figure 3A,B), and upregulated IL‐17, IL‐23p19 and IL‐36 in skin (Figure 3C–E), and antibodies against IL‐23A or IL‐17A reversed the changes in IL‐17 but not the other cytokines and alleviated IMQ‐induced inflammatory thickening of the skin (Figure 3A–E). IMQ downregulated the anti‐inflammatory cytokine IL‐10 in the skin, while either anti‐IL‐23A or anti‐IL‐17A antibody upregulated it (Figure 3F). These results suggest that blocking the IL‐23/IL‐17 axis may alleviate skin inflammation at least in part by restoring levels of IL‐10.

FIGURE 3.

Treatment with anti‐interleukin (IL)‐17 or anti‐IL‐23 antibody alleviates skin inflammation in imiquimod (IMQ)‐treated mice. (A) Representative micrographs of ear tissue from mice treated with vaseline (control) or IMQ in the presence or absence of anti‐IL‐17A, anti‐IL‐23A, or immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Ear thickness of vaseline or IMQ‐treated mice before treatment (day 0) or after treatment with anti‐IL‐23A or anti‐IL‐17A antibody (day 7). Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (vasiline + IgG = 10, IMQ + IgG = 10, IMQ + anti‐IL23A = 7, IMQ + anti‐IL17A = 7). **p < .01, ***p < .001 by one‐way analysis of variance with Tukey's multiple‐comparison post hoc test. (C–F) Levels of cytokines involved in the IL‐23/IL‐17 axis in the skin of mice treated with vaseline or IMQ in the presence or absence of anti‐IL‐17A or anti‐IL‐23A antibody. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (vasiline + IgG = 7, IMQ + IgG = 7, IMQ + anti‐IL23 = 4, IMQ + anti‐IL17 = 4). *p < .05, **p < 0.01 versus vaseline + IgG group. # p < .05, ## p < .01 versus IMQ + IgG group by one‐way analysis of variance with Tukey's multiple‐comparison post hoc test.

2.3. Inhibiting IL‐23 or IL‐17 alleviates IMQ‐induced abnormal immunity in mice

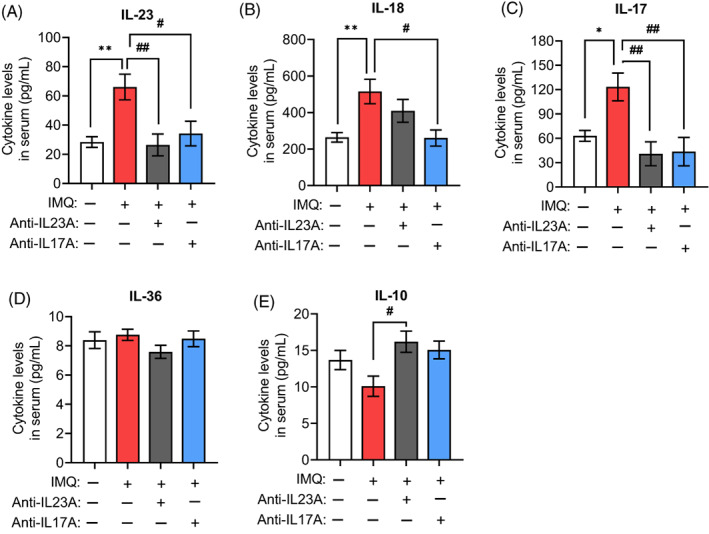

The IL‐23/IL‐17 signal axis was abnormally activated in the serum of our psoriatic mouse model, based on increases in the pro‐inflammatory cytokines IL‐23p19, IL‐17, and IL‐18, but not IL‐36 and IL‐10 (Figure 4A–E). This cytokine expression pattern was similar to the one observed in the serum of patients with psoriasis. Treatment with either anti‐IL‐23A or anti‐IL‐17A antibody downregulated pro‐inflammatory cytokines IL‐23p19, IL‐17, and IL‐18, and upregulated the IL‐10 in the serum of psoriatic mice (Figure 4A–E). These results suggest that blocking the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis can help restore the normal immune response in a psoriatic mouse model.

FIGURE 4.

Treatment with anti‐interleukin (IL)‐17 or anti‐IL‐23 antibody helps restore normal IL levels in the serum of imiquimod (IMQ)‐treated mice. (A–D) Concentrations of ILs involved in the IL‐23/IL‐17 axis in the serum of mice treated with vaseline or IMQ in the presence or absence of anti‐IL‐17A or anti‐IL‐23A antibody. (E) Concentrations of anti‐inflammatory cytokine IL‐10 in the serum of mice treated with vaseline or IMQ in the presence or absence of anti‐IL‐17A or anti‐IL‐23A antibody. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (vasiline + IgG = 7, IMQ + IgG = 7, IMQ + anti‐IL23 = 4, IMQ + anti‐IL17 = 4). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus vaseline + IgG group; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01 versus IMQ + IgG group by one‐way analysis of variance with Tukey's multiple‐comparison post hoc test.

2.4. Psoriatic skin inflammation due to the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis involves activation of the ACT1/NF‐κB pathway in keratinocytes and macrophage

To investigate how the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis mediates skin inflammation in psoriasis, we evaluated levels of IL‐17RC, ACT1, TRAF6, TAK1, NF‐κB, and pNF‐κB proteins in skin of different mouse groups using western blotting. IMQ significantly upregulated interleukin‐17 receptor (IL‐17R) and its ligand ACT1 in the ear (Figure 5A–C), as well as the downstream effectors TAK1 and TRAF6 (Figure 5D,E). It also upregulated total and phosphorylated levels of NF‐κB in the skin (Figure 5F,G). Treatment with either anti‐IL‐23A or anti‐IL‐17A antibody downregulated IL‐17RC, ACT1, TRAF6, TAK1, NF‐κB, and pNF‐κB (Figure 5A–G), supporting the idea that ACT1/TRAF6/TAK1/NF‐κB signaling contributes to the skin inflammation in IMQ‐treated mice.

FIGURE 5.

Treatment with anti‐interleukin (IL)‐17 or anti‐IL‐23 antibody inhibits ACT1/NF‐κB signaling in the ear skin of imiquimod (IMQ)‐treated animals. (A) Western blotting of IL‐17 receptor (IL‐17RC), ACT1, TAK1, TRAF6, NF‐κB, and phosphorylated (p)‐NF‐κB in the skin of mice treated with vaseline or IMQ in the presence or absence of anti‐IL‐17A or anti‐IL‐23A antibody. (B–G) Quantification of IL‐17RC, ACT1, TAK1, TRAF6, NF‐κB and p‐NF‐κB expression. Levels of IL‐17RC, ACT1, TAK1, TRAF6, and NF‐κB were normalized to that of GAPDH, while levels of p‐NF‐κB were normalized to that of NF‐κB. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 3 mice, each sample in triplicate). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus vaseline + IgG group; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 versus IMQ + IgG group by one‐way analysis of variance with Tukey's multiple‐comparison post hoc test.

To better understand the contribution of keratinocytes in psoriatic skin inflammation, we detected the nuclear transcription factors of inflammation NF‐κB p65 expression in skin tissue of mice with IMQ‐induced psoriasis by immunofluorescent staining analysis. The results showed that a number of NF‐κB p65+ cells in both the epidermis and dermis of psoriatic lesional skin (Figure 6A). Meanwhile, an increased number of NF‐κB p65+ cells in the epidermis and dermis of psoriatic non‐lesional skin was observed compared to healthy skin (Figure 6A). We also found that a large proportion of NF‐κB p65 localized in nucleus of involucrin+ cells in the suprabasal layers of psoriatic lesional skin (Figure 6A), and only a few proportion of NF‐κB p65 localized in K14+ cells in the basal layer of psoriatic lesional skin (Figure 6B). These results suggested that NF‐κB pathway was activated by IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis in keratinocytes of epidermis that involves psoriatic skin inflammation.

FIGURE 6.

NF‐κB p65 expression in keratinocytes of the epidermis of psoriatic lesional skin. (A) Immunofluorescence micrographs of NF‐κB p65 and keratinocytes of the suprabasal layers in psoriatic lesional skin. Nuclear transcription factors associated with inflammation NF‐κB p65 were labeled with NF‐κB p65 antibody (red), the precursor protein of the keratinocyte cornified envelope were labeled with involucrin antibody (green), and the nuclei were labeled with 4,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI, blue). The NF‐κB p65+‐involucrin+ cells were marked with arrowheads in high resolution illustrations below. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Immunofluorescence micrographs of NF‐κB p65 and keratinocytes of the basal layer in psoriatic lesional skin. NF‐κB p65 were labeled with NF‐κB p65 antibody (red), the mature keratinocytes were labeled with cytokeratin 14 (K14) antibody (green), and the nuclei were labeled with DAPI, blue. The NF‐κB p65+‐K14+ cell was marked with arrowhead in high resolution illustrations below. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Additionally, we investigated the activation of NF‐κB signaling pathways in skin immune cells, including T cells (CD3+), macrophage (F4/80+) and neutrophil (CD11b+), in skin tissue of mice with IMQ‐induced psoriasis by immunofluorescent staining analysis. We observed a lot of CD3+, F4/80+ or CD11b+ cells infiltrated in dermis of psoriatic lesional skin (Figure 7A–C). We then identified NF‐κB p65 expression in these cells of skin tissue of mice with IMQ‐induced psoriasis by immunofluorescent staining analysis. We found that a large proportion of NF‐κB p65 expressed in nucleus of F4/80+ cells of the dermis of psoriatic lesional skin (Figure 7A), and only a few proportion of NF‐κB p65 localized in CD3+ or CD11b+ cells in the dermis of psoriatic lesional skin (Figure 7B,C). These results suggested that NF‐κB was activated by IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis in macrophage of dermis that mediates psoriatic skin inflammation.

FIGURE 7.

NF‐κB p65 expression in immune cell of the dermis of psoriatic lesional skin. (A) Immunofluorescence micrographs of NF‐κB p65 and T cells in psoriatic lesional skin. NF‐κB p65 were labeled with NF‐κB p65 antibody (red), the T cells of skin tissue were labeled with CD3 antibody (green), and the nuclei were labeled with 4,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI, blue). The NF‐κB p65+‐CD3+ cells were marked with arrowheads in high resolution illustrations below. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Immunofluorescence micrographs of NF‐κB p65 and macrophage in psoriatic lesional skin. NF‐κB p65 were labeled with NF‐κB p65 antibody (pink), the macrophage of skin tissue were labeled with F4/80 antibody (green), and the nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). The NF‐κB p65+‐F4/80+ cells were marked with arrowheads in high resolution illustrations below. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Immunofluorescence micrographs of NF‐κB p65 and granulocyte in psoriatic lesional skin. NF‐κB p65 were labeled with NF‐κB p65 antibody (red), the granulocyte of skin tissue were labeled with CD11b antibody (green), and the nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). The NF‐κB p65+‐CD11b+ cells were marked with arrowheads in high resolution illustrations below. Scale bar, 100 μm.

3. DISCUSSION

Previous studies reported on the characterization of the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis induces psoriasis inflammation, but how it contributes to the underlying skin inflammation is unclear. In the present study, we found that the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis is activated in patients with psoriasis and IMQ‐treated mice. Moreover, we found that IMQ‐treated mice showed increased expression of ACT1, TRAF6, TAK1, NF‐κB, and pNF‐κB in the skin. NF‐κB pathway was activated in keratinocytes of epidermis and in macrophage of dermis of psoriatic lesional skin that involves psoriatic skin inflammation. Treatment with anti‐IL‐23A or anti‐IL‐17A antibody rescued the changes induced by IMQ and ameliorated skin inflammation. Thus, our results suggest that the ACT1/TRAF6/TAK1/NF‐κB pathway in keratinocytes and macrophage contributes to the skin inflammation mediated by the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis in psoriasis.

Several immune‐related pathways are involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. The immune imbalance and inflammatory response mediated by the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis play a key role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. 6 Long‐term Western diets high in fat and sugar promote Th2 and Th17 differentiation through the activation of TGR5 and S1PR2, thereby exacerbating skin inflammation in psoriasis. 7 , 8 , 9 Indeed, we found that patients with psoriasis showed elevated serum levels of numerous cytokines involved in the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis: IL‐2, IL‐4, IL‐8, IL‐12, IL‐17, IL‐22, IL‐23, and IFN‐γ. The up‐regulation of IL‐12 and IL‐23 is related to the maturation of dendritic cells. 10 IL‐2 is produced by helper T cells to amplify immune responses. 11 The up‐regulation of IFN‐γ, IL‐4 and IL‐17 is related to the maturation of Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells. 12 , 13 The significant increase of these molecules in the sera of patients with psoriasis suggests that a hyper systemic immune response is initiated in psoriasis, specifically, dendritic cell maturation and T cells activation.

IMQ‐treated mice also showed elevated levels of IL‐23p19 and IL‐17 in serum and skin. Signaling mediated by IL‐23 and IL‐17 receptors are essential to the development of psoriasis: disease development was almost completely blocked in mice deficient in IL‐23 or the IL‐17 receptor. 14 Thus, drugs targeting the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis may be effective against psoriasis. Consistently, we found that treating IMQ mice with anti‐IL‐23A or anti‐IL‐17A antibody improved pathology score and immune imbalance.

IL‐10 is an anti‐inflammatory cytokine, which can exert either immunosuppressive or immunostimulatory effects on a variety of cell types. IL‐10 is a negative regulator of psoriasis. 15 This immunomodulatory cytokine is a central anti‐inflammatory mediator that reduces tissue damage caused by excessive and uncontrolled inflammatory stimulation and protects the host from an excessive inflammatory response. 15 Studies found that IL‐10 level was decreased in patients with psoriasis compared to healthy controls. 16 Interestingly, patients during established antipsoriatic therapy showed a higher IL‐10 mRNA expression of peripheral blood mononuclear cells than patients before the therapy. 17 In the present study, we observed decreased expression of IL‐10 in the skin of IMQ‐treated mice compared to healthy mice. However, either anti‐IL‐23A or anti‐IL‐17A antibody upregulated IL‐10 level in the skin of IMQ‐treated mice. A study indicated that macrophages were the major population of IL‐10‐releasing myeloid cells in the skin of mice. 15 These results suggest that blocking the IL‐23/IL‐17 axis may alleviate skin inflammation at least in part by restoring levels of IL‐10 in macrophages of skin.

The NF‐κB family of transcription factors has an essential role in immune responses, inflammation and innate immunity. 18 NF‐κB signaling may contribute to inflammation in cancer, chronic inflammation, and autoimmune diseases. 18 It has been found that the NF‐κB signaling is activated in psoriatic lesions and participates in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. 19 We found that IMQ upregulated pNF‐κB in the skin lesions of mice, consistent with observations in another model of IMQ‐induced mice, 20 supporting the idea that NF‐κB signaling contributes to pathology of psoriasis. Growing evidence suggests that activation of NF‐κB occurs through release of IκB. 21 IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ in the IKK complex can activate IκB, which further activates the NF‐κB signaling pathway. 22 TAK1 is an important regulator to activate IKK. 23 In the present study, IMQ activated NF‐κB by inducing TAK1 expression.

It has been reported that IL‐17 binds to its receptor IL‐17R to promote the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. 24 Transcription factor NF‐κB activator 1 (ACT1) was found to contain a SEFIR domain which is recruited by IL‐17R and mediates the IL‐17R‐ACT1 interaction. 25 ACT1 contains two tumor TRAF binding motifs, which binds to its downstream effector TRAF6 to activate TAK1. 4 , 26 Furthermore, studies have revealed that activation of TRAF6/TAK1 results in the triggering of NF‐κB pathway. 27 , 28 In the present study, we found that IMQ upregulated IL‐17RC, ACT1, and TRAF6 in the skin lesions of mice, presumably reflecting the ability of those molecules to activate TAK1. We found that a number of NF‐κB p65+ cells in both the epidermis and dermis of psoriatic lesional skin. Meanwhile, an increased number of NF‐κB p65+ cells in the epidermis and dermis of psoriatic non‐lesional skin was observed compared to healthy skin. These results suggest that in psoriasis, the ACT1/TRAF6/TAK1 pathway activates NF‐κB signaling.

It is important that IL‐17 binds to its receptor and activates ACT1 to NF‐κB signaling activation in skin. 29 Consistently, we showed here in a mouse model of psoriasis that anti‐IL‐17A antibody downregulates ACT1 as well as other proteins related to ACT1‐activated NF‐κB signaling. Similarly, anti‐IL‐23A antibody downregulated several proteins related to this pathway: IL‐17RC, ACT1, TRAF6, NF‐κB, and pNF‐κB. These results suggest that IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis‐mediated skin inflammation in psoriasis involves activation of the ACT1/NF‐κB pathway. It is thought that the inhibition of NF‐κB signaling pathway to reduce hyperproliferation and excessive inflammation in keratinocytes could be promising anti‐psoriatic strategy. 19 Several compounds have been found to exhibit attractive therapeutic potential for psoriasis though inhibiting NF‐κB signaling pathway, such as daphnetin, ligustrazine, cimifugin and so on. 30 , 31 , 32 In addition, some nutrients of foods have also been shown to alleviate psoriasis skin inflammation though inhibiting NF‐κB activation and NF‐κB‐dependent inflammatory cytokine production, such as Vitamin B12, Genistein, Selenium and so on. 33 Further study is needed to clarify whether the NF‐κB signaling pathway is necessary for IL‐23/IL‐17‐mediated psoriatic skin inflammation. This will require blocking specific steps in this pathway.

Finally, we also defined the specific skin cells in which the ACT1/NF‐κB pathway helps drive psoriasis. We observed a lot of CD3+, F4/80+ or CD11b+ cells infiltrated in dermis of psoriatic lesional skin. And a large proportion of NF‐κB p65 localized in nucleus of involucrin+ cells in the suprabasal layers and in F4/80+ cells of the dermis of psoriatic lesional skin, and only a few proportion of NF‐κB p65 localized in K14+ cells in the basal layer and in CD3+ or CD11b+ cells in the dermis of psoriatic lesional skin. Macrophages in the skin are located in the dermis, they have scavenging and phagocytic activities. 34 Studies have shown that NF‐κB pathway activation could induce classically activated macrophages (M1 macrophages) to initiate inflammatory processes. 35 , 36 These results suggested that NF‐κB pathway was activated by IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis in keratinocytes of epidermis and in macrophage of dermis that mediates psoriatic skin inflammation.

Our study presents several limitations. First, the role of the ACT1/NF‐κB pathway was demonstrated here in a mouse model of psoriasis, but this should be confirmed in tissues from patients with psoriasis. Second, further work is needed to establish whether the ACT1/NF‐κB pathway is required for inflammation mediated by the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis in psoriasis.

Despite these limitations, our study provides strong evidence that skin inflammation mediated by the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis in psoriasis involves activation of the ACT1/TRAF6/TAK1/NF‐κB pathway in keratinocytes and macrophage. Our results provide further insights into the pathogenesis of psoriasis and may help guide the development of new therapies.

4. CONCLUSION

Our results suggest that the IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis helps drive skin inflammation in psoriasis via the activation of the NF‐κB signaling pathway in keratinocytes and macrophage through the ACT1/TRAF6/TAK1 pathway. These findings provide further insights into the pathogenesis of psoriasis and may guide the development of novel drugs for targeting the ACT1/NF‐κB pathway in skin.

5. MATERIALS AND METHODS

5.1. Patients

This study retrospectively included data from eight consecutively selected patients with psoriasis (four men, 18–65 years old) and eight healthy subjects (four men, 18–65 years old) who visited our dermatology clinic between March 2015 and March 2016. All patients were clinically diagnosed by two experienced dermatologists. Patients were excluded if they had a history of any other chronic‐inflammatory, allergic, autoimmune, genetic, metabolic, or neoplastic disease. All controls were enrolled after undergoing complete physical examinations and after they were confirmed not to have a family history of psoriasis or to have taken any medication within the previous 3 months.

Data were recorded on age, sex, age at psoriasis onset, psoriasis duration, family history, body mass index, and body surface area. After enrolment of patients and controls, 5 mL of venous blood was drawn by venipuncture without anticoagulation into a blood collection tube. The blood samples were left at room temperature for 30 min, rapidly centrifuged for 15 min at 4°C at 2500 g, and serum was immediately stored in aliquots at −80°C until analysis.

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of The First Clinical Medical College of Guizhou University of Chinese Medicine (Guiyang, China), and informed consent was signed by all patients and their families.

5.2. Animals

Eight week‐old male C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Chongqing Thengxin Biotechnology (Chongqing, China) and allowed to acclimate for 1 week before experiments. Throughout the experiments, all mice were housed under a 12/12‐h light/dark cycle in temperature‐ and humidity‐controlled rooms. All animals had free access to water and food. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Guizhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

5.3. Groups and treatment

Vaseline was purchased from Guizhou Xinyuan Biotechnology (Guiyang, China), while IMQ cream was purchased from Sichuan Mingxin Pharmaceutical (Sichuan, China). Phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), recombinant anti‐IL‐23A antibody (anti‐IL‐23A) and anti‐IL‐17A antibody (anti‐IL‐17A) were purchased from Boster (Wuhan, China). Immunoglobulin G (IgG) was purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China). In all cases, antibody or IgG was diluted with PBS and injected intraperitoneally.

Mice (n = 34) were randomly assigned to the different treatment groups: Vaseline + IgG (n = 10), IMQ + IgG (n = 10), IMQ + anti‐IL‐23A (n = 7) or IMQ + anti‐IL‐17A (n = 7). Vaseline or IMQ cream were topically applied onto the skin of the inside ears at 30 mg/days for 7 days. Animals in the Vaseline + IgG and IMQ + IgG groups received IgG (100 μg/mice) as control at 4 h after treatment with vaseline or IMQ. Animals in the IMQ + anti‐IL‐23A and IMQ + anti‐IL‐17A groups received anti‐IL‐23A (100 μg/mice) 37 or anti‐IL‐17A (100 μg/mice) 38 was administered intraperitoneallyat 4 h after treatment with IMQ.

On day 8 after the start of treatment, mice were euthanized (cervical dislocation), and samples of skin and blood were subjected to molecular, histological, and western blot analyses as described below.

5.4. Psoriasis Severity Index

Psoriasis Severity Index (PSI) score assessment was used as previously described to evaluate the severity of erythema, scaling and induration on the ear skin of mice. 39 , 40 PSI‐E (erythema)/PSI‐S (scaling)/PSI‐I (induration) was graded 0 to 4 (0, none; 1, slight; 2, moderate; 3, marked; 4, very marked) and added. The sum of erythema, scales, and thickness scores gives the total score. The induration (thickness) was further determined by micrometer measurements. A researcher who was blinded to treatments recorded and analyzed data in the animal experiments.

5.5. Tissue sections and hematoxylin–eosin staining

After sacrifice, mice ears were cut, immediately fixed in 10% buffered formalin at room temperature for at least 24 h, dehydrated in graded ethanol, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin according to routine techniques. Sections of paraffin‐embedded tissue (5 μm thick) were mounted on glass slides, hydrated in distilled water, then stained with hematoxylin–eosin (Servicebio, Wuhan, China). Slides were examined at magnifications of 10× and 20× using a microscope (Olympus IX73, Tokyo, Japan) to assess erythema, scales, thickening, epidermal acanthosis, and inflammation.

5.6. Enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays

On day 8 after the start of treatment, all mice were euthanized and 0.5 mL of blood was obtained from the posterior orbital venous plexus into a 2 mL centrifuge tube. The blood samples were left at room temperature for 30 min, rapidly centrifuged at 4°C, at 2500g for 15 min to collect the serum. Mice ears were cut into pieces, suspended in radio‐immunoprecipitation assay buffer containing inhibitors of proteases and phosphatases (Servicebio), and homogenized using a high‐throughput tissue grinder (Shanghai Huake Laboratory Equipment, Shanghai, China). Samples were centrifuged at 400g for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were analyzed as described below.

Cytokine levels in serum from patients were determined using commercial sandwich enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs; Shenzhen Jingmei Biotechnology, Shenzhen, China). Cytokine levels in serum from mice and in the soluble fraction of total mouse ear lysates were estimated using commercial sandwich ELISAs (Boster), and samples were diluted as necessary with sample diluent buffer (Boster) to obtain equal total protein concentrations. Then the levels of IL‐2, IL‐4, IL‐8, IL‐10, IL‐12, IL‐17, IL‐22, IL‐23, IL‐36, and interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ) were determined according to the manufacturer's instructions. Manufacturer‐specified ELISA sensitivities were as follows: mouse IL‐23 p19, <2 pg/mL; human IL‐23, <10 pg/mL; mouse or human IL‐17, <1 pg/mL; mouse or human IL‐10, <1 pg/mL; mouse IL‐36, <0.5 ng/L; mouse IL‐18, <4 pg/mL; human IL‐2, <1 pg/mL; human IL‐12, <1.5 pg/mL; human IL‐8, <1 pg/mL; human IL‐4, <1.5 pg/mL; human IL‐22, <1 pg/mL; human IFN‐γ, <1 pg/mL.

5.7. Western blot analysis

Mouse ear tissues were suspended in radio‐immunoprecipitation assay buffer containing inhibitors of proteases and phosphatases (Servicebio) and ground up in a homogenizer (Servicebio). Then lysates were centrifuged at 600g at 4°C for 10 min, and the supernatants were collected. Total protein concentration was estimated using a BCA kit (Servicebio) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and equal amounts of protein were fractionated by SDS‐PAGE. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (0.45 μm; Servicebio), which were blocked at room temperature for 30 min in triethanolamine buffered saline solution + Tween 20 (TBS‐T) buffer containing 5% skim milk. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies (see Supplemental Digital Content 1, which demonstrates primary antibodies), washed with TBS‐T buffer, and incubated at room temperature for 30 min with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibodies (see Supplemental Digital Content 2, which demonstrates secondary antibodies). Finally, membranes were scanned with a V370 scanner (Epson, Shenzhen, China), and bands were quantitated using AlphaEaseFC software 4.0 (Alpha Innotech, Shanghai, China).

5.8. Immunohistochemistry

Skin tissue of mice was measured by immunohistochemical analysis. On day 8 after the start of treatment, mice were euthanized (cervical dislocation), and skin was obtained and postfixed with 4.0% paraformaldehyde for 48 h and in 30% sucrose for 24 h. Skin sections (25 μm thick) were cut using a sliding vibratome (CM1900; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and collected in PBS. Six sequential slices were placed into each well of a 12‐well plate and stored at 4°C. Skin samples were immunofluorescence stained by involucrin for the precursor protein of the keratinocyte cornified envelope, Cytokeratin 14 antibody for mature keratinocytes, CD3 for T cells, F4/80 for macrophages, CD11b for granulocyte, NF‐κB p65 antibody for anti‐NF‐κB p65. The slices were blocked in 10% donkey serum for 2 h, incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies were Mouse anti‐NF‐κB p65 (1:300; Santa Cruz, USA), mouse anti‐involucrin (1:300; Novus, USA), mouse anti‐Cytokeratin 14 (1:300; Novus, USA), Rabbit anti‐NF‐κB p65 (1:300; G‐Biosciences, USA), Rabbit anti‐CD3 (1:400; Cell Signaling Technology, USA), Rabbit anti‐CD11b (1:400; Cell Signaling Technology), Rabbit anti‐ F4/80 (1:400; Cell Signaling Technology). Slices were washed three times with PBS, then incubated for 2 h at room temperature with DyLight 549‐ or DyLight 488‐conjugate secondary antibodies (both 1:300; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA). Finally, cells were incubated for 5 min with 4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI; 1:10,000, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX 73, Tokyo, Japan).

5.9. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses and graphic representations were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software (San Diego, CA, USA). All data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences between the mean values were evaluated by a paired Student's t‐test for independent samples. Multiple groups were compared with either one‐way analysis of variance, followed by the Turkey post hoc test. Differences associated with p of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. Statistical tests are specified in individual figure legends.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Supplementary information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We appreciate Creaducate Consulting GmbH (Munich, Germany) for their assistance with polishing the language of the manuscript.

Chen W‐C, Wen C‐H, Wang M, Xiao Z‐D, Zhang Z‐Z, Wu C‐L, et al. IL‐23/IL‐17 immune axis mediates the imiquimod‐induced psoriatic inflammation by activating ACT1/TRAF6/TAK1/NF‐κB pathway in macrophages and keratinocytes. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2023;39(8):789–800. 10.1002/kjm2.12683

Wen‐Cheng Chen and Chang‐Hui Wen share first authorship.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sebastian Y, Lee C‐W, Li Y‐A, Chen T‐H, Hsin‐Su Y. Prenatal infection predisposes offspring to enhanced susceptibility to imiquimod‐mediated psoriasiform dermatitis in mice. Dermatol Sin. 2022;40(1):14–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, Barker J. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397(10281):1301–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wu NL, Huang DY, Tsou HN, Lin YC, Lin WW. Syk mediates IL‐17‐induced CCL20 expression by targeting Act1‐dependent K63‐linked ubiquitination of TRAF6. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(2):490–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Espada CE, St Gelais C, Bonifati S, Maksimova VV, Cahill MP, Kim SH, et al. TRAF6 and TAK1 contribute to SAMHD1‐mediated negative regulation of NF‐κB signaling. J Virol. 2021;95(3):e01970–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zheng C, Zheng Z, Zhang Z, Meng J, Liu Y, Ke X, et al. IFIT5 positively regulates NF‐κB signaling through synergizing the recruitment of IκB kinase (IKK) to TGF‐β‐activated kinase 1 (TAK1). Cell Signal. 2015;27(12):2343–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boutet MA, Nerviani A, Gallo Afflitto G, Pitzalis C. Role of the IL‐23/IL‐17 axis in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: the clinical importance of its divergence in skin and joints. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(2):530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yu S, Wu X, Zhou Y, Sheng L, Jena PK, Han D, et al. A Western diet, but not a high‐fat and low‐sugar diet, predisposes mice to enhanced susceptibility to imiquimod‐induced psoriasiform dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(6):1404–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jena PK, Sheng L, McNeil K, Chau TQ, Yu S, Kiuru M, et al. Long‐term Western diet intake leads to dysregulated bile acid signaling and dermatitis with Th2 and Th17 pathway features in mice. J Dermatol Sci. 2019;95(1):13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yu S, Wu X, Shi Z, Huynh M, Jena PK, Sheng L, et al. Diet‐induced obesity exacerbates imiquimod‐mediated psoriasiform dermatitis in anti‐PD‐1 antibody‐treated mice: implications for patients being treated with checkpoint inhibitors for cancer. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;97(3):194–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vaknin‐Dembinsky A, Balashov K, Weiner HL. IL‐23 is increased in dendritic cells in multiple sclerosis and down‐regulation of IL‐23 by antisense oligos increases dendritic cell IL‐10 production. J Immunol. 2006;176(12):7768–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Busse D, de la Rosa M, Hobiger K, Thurley K, Flossdorf M, Scheffold A, et al. Competing feedback loops shape IL‐2 signaling between helper and regulatory T lymphocytes in cellular microenvironments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(7):3058–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Talaat RM, Mohamed SF, Bassyouni IH, Raouf AA. Th1/Th2/Th17/Treg cytokine imbalance in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients: correlation with disease activity. Cytokine. 2015;72(2):146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Attia SK, Moftah NH, Abdel‐Azim ES. Expression of IFN‐γ, IL‐4, and IL‐17 in cutaneous schistosomal granuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(8):991–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van der Fits L, Mourits S, Voerman JS, Kant M, Boon L, Laman JD, et al. Imiquimod‐induced psoriasis‐like skin inflammation in mice is mediated via the IL‐23/IL‐17 axis. J Immunol. 2009;182(9):5836–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yong L, Yu Y, Li B, Ge H, Zhen Q, Mao Y, et al. Calcium/calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase IV promotes imiquimod‐induced psoriatic inflammation via macrophages and keratinocytes in mice. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kutwin M, Migdalska‐Sęk M, Brzeziańska‐Lasota E, Zelga P, Woźniacka A. An analysis of IL‐10, IL‐17A, IL‐17RA, IL‐23A and IL‐23R expression and their correlation with clinical course in patients with psoriasis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(24):5834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Asadullah K, Sabat R, Friedrich M, Volk HD, Sterry W. Interleukin‐10: an important immunoregulatory cytokine with major impact on psoriasis. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2004;3(2):185–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pflug KM, Sitcheran R. Targeting NF‐κB‐inducing kinase (NIK) in immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(22):8470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goldminz AM, Au SC, Kim N, Gottlieb AB, Lizzul PF. NF‐κB: an essential transcription factor in psoriasis. J Dermatol Sci. 2013;69(2):89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang BY, Cheng YG, Liu Y, Liu Y, Tan JY, Guan W, et al. Ameliorates imiquimod‐induced psoriasis‐like dermatitis and inhibits inflammatory cytokines production through TLR7/8‐MyD88‐NF‐κB‐NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Molecules. 2019;24(11):2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hoesel B, Schmid JA. The complexity of NF‐κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mulero MC, Huxford T, Ghosh G. NF‐κB, IκB, and IKK: integral components of immune system signaling. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1172:207–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weng T, Koh CG. POPX2 phosphatase regulates apoptosis through the TAK1‐IKK‐NF‐κB pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(9):e3051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Onishi RM, Park SJ, Hanel W, Ho AW, Maitra A, Gaffen SL. SEF/IL‐17R (SEFIR) is not enough: an extended SEFIR domain is required for il‐17RA‐mediated signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(43):32751–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Qian Y, Liu C, Hartupee J, Altuntas CZ, Gulen MF, Jane‐Wit D, et al. The adaptor Act1 is required for interleukin 17‐dependent signaling associated with autoimmune and inflammatory disease. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(3):247–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Qu F, Gao H, Zhu S, Shi P, Zhang Y, Liu Y, et al. TRAF6‐dependent Act1 phosphorylation by the IκB kinase‐related kinases suppresses interleukin‐17‐induced NF‐κB activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(19):3925–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huang F, Kao CY, Wachi S, Thai P, Ryu J, Wu R. Requirement for both JAK‐mediated PI3K signaling and ACT1/TRAF6/TAK1‐dependent NF‐kappaB activation by IL‐17A in enhancing cytokine expression in human airway epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2007;179(10):6504–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kanamori M, Kai C, Hayashizaki Y, Suzuki H. NF‐kappaB activator Act1 associates with IL‐1/Toll pathway adaptor molecule TRAF6. FEBS Lett. 2002;532(1–2):241–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wu L, Zepp J, Li X. Function of Act1 in IL‐17 family signaling and autoimmunity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;946:223–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gao J, Chen F, Fang H, Mi J, Qi Q, Yang M. Daphnetin inhibits proliferation and inflammatory response in human HaCaT keratinocytes and ameliorates imiquimod‐induced psoriasis‐like skin lesion in mice. Biol Res. 2020;53(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jiang R, Xu J, Zhang Y, Liu J, Wang Y, Chen M, et al. Ligustrazine alleviates psoriasis‐like inflammation through inhibiting TRAF6/c‐JUN/NFκB signaling pathway in keratinocyte. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;150:113010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu A, Zhao W, Zhang B, Tu Y, Wang Q, Li J. Cimifugin ameliorates imiquimod‐induced psoriasis by inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation via NF‐κB/MAPK pathway. Biosci Rep. 2020;40(6):BSR20200471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kanda N, Hoashi T, Saeki H. Nutrition and psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(15):5405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang W, Qu R, Wang X, Zhang M, Zhang Y, Chen C, et al. GDF11 antagonizes psoriasis‐like skin inflammation via suppression of NF‐κB signaling pathway. Inflammation. 2019;42(1):319–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ge G, Bai J, Wang Q, Liang X, Tao H, Chen H, et al. Punicalagin ameliorates collagen‐induced arthritis by downregulating M1 macrophage and pyroptosis via NF‐κB signaling pathway. Sci China Life Sci. 2022;65(3):588–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pan Y, You Y, Sun L, Sui Q, Liu L, Yuan H, et al. The STING antagonist H‐151 ameliorates psoriasis via suppression of STING/NF‐κB‐mediated inflammation. Br J Pharmacol. 2021;178(24):4907–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li L, Wu Z, Wu M, Qiu X, Wu Y, Kuang Z, et al. IBI112, a selective anti‐IL23p19 monoclonal antibody, displays high efficacy in IL‐23‐induced psoriasiform dermatitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;89(Pt B):107008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shimizu T, Kamata M, Fukaya S, Hayashi K, Fukuyasu A, Tanaka T, et al. Anti‐IL‐17A and IL‐23p19 antibodies but not anti‐TNFα antibody induce expansion of regulatory T cells and restoration of their suppressive function in imiquimod‐induced psoriasiform dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 2019;95(3):90–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhou Y, Han D, Follansbee T, Wu X, Yu S, Wang B, et al. Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) positively regulates imiquimod‐induced, psoriasiform dermal inflammation in mice. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(7):4819–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhou Y, Follansbee T, Wu X, Han D, Yu S, Domocos DT, et al. TRPV1 mediates inflammation and hyperplasia in imiquimod (IMQ)‐induced psoriasiform dermatitis (PsD) in mice. J Dermatol Sci. 2018;92(3):264–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Supplementary information.