Abstract

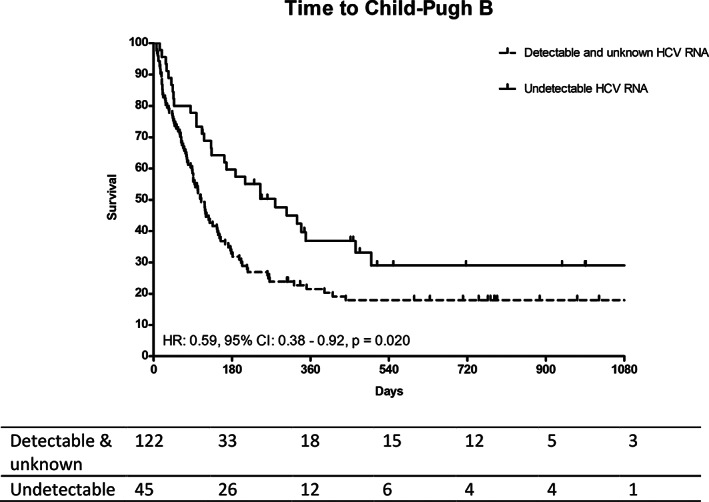

Whether patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC) benefit from hepatitis C virus (HCV) eradication is uncertain. We aimed to investigate whether a survival benefit was conferred by HCV eradication in aHCC patients. This retrospective cohort study enrolled 168 HCV‐infected aHCC patients from April 2013 to January 2019. All patients were treated with sorafenib. Endpoints included overall survival (OS), progression free survival (PFS), and time to liver decompensation. Patients with undetectable HCV RNA exhibited reduced aspartate aminotransferase and alpha fetoprotein levels, as well as an attenuated proportion of aHCC at initial diagnosis but increased albumin and mean sorafenib daily dosing. Patients with undetectable HCV RNA exhibited significantly longer OS compared to patients with detectable or unknown HCV RNA, which was an independent factor of OS (HR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.350‐0.903, P = .017). Patients with undetectable HCV RNA also presented a trend for longer PFS (HR 0.68, 95% CI: 0.46‐1.00, P = .053). The survival benefit was considered with respect to the significantly prolonged time to Child‐Pugh B scores in patients with undetectable HCV RNA (HR 0.59, 95% CI: 0.38‐0.92, P = .020). Patients with detectable HCV RNA at sorafenib initiation who further received direct acting antiviral therapy also had significantly longer OS (HR 0.11, 95% CI: 0.02‐0.81, P = .030) and PFS (HR 0.23, 95% CI: 0.06‐0.99, P = .048). In conclusion, abolishing HCV viremia preserves liver function and confers a survival benefit in advanced HCC patients on sorafenib treatment.

Keywords: direct acting antivirals, hepatitis C virus, hepatocellular carcinoma, Sorafenib, survival

1. INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains the fifth most common cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer‐related death. 1 , 2 Diverse treatment strategies are prescribed based on the staging of HCC. Curative therapies, including surgery, radiofrequency ablation, and liver transplantation, are all feasible in patients with early stage HCC and confer survival benefits. 3 , 4 Even in patients with unresectable HCC without macrovascular invasion or extra‐hepatic spreading, palliative treatment with transarterial chemoembolization still prolongs overall survival. 5 A lack of responsive to systemic treatment limits the survival of patients with advanced stage HCC (aHCC). 6 Administration of sorafenib prolongs overall survival in aHCC patients to more than 10 months 7 , 8 , 9 and has been recommended as the first‐line standard of care for 10 years. 10 , 11 , 12 Several kinase inhibitors, including lenvatinib regorafenib, carbozantinib, and ramucirumab, showed non‐inferior efficacy to sorafenib and prolonged survival after sorafenib failure, providing additional treatment options for patients with aHCC. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16

Although these newer agents prolong overall survival, treatment responses remain unsatisfactory, and the field currently lacks a response/survival predictor. Subgroup analysis of phase 3 trials of sorafenib demonstrated a superior survival benefit in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. 17 , 18 However, whether HCV viremia influences survival in aHCC patients on sorafenib treatment was not further investigated. In an earlier study enrolling HCV infected HCC patients on sorafenib treatment, results showed a survival benefit in patients who experienced HCV eradication before sorafenib. 19 In addition, whether HCV antiviral treatment is indicated in patients with a short life expectancy, such as those with aHCC, remains uncertain in regional guidelines. 20 , 21 , 22

Consequently, we conducted the current study to investigate the impact of HCV viremia on the outcomes of aHCC patients on sorafenib treatment.

2. PATIENTS AND METHODS

The present study retrospectively recruited aHCC patients who received sorafenib therapy at a medical center in Southern Taiwan from April 2013 to January 2019. A total of 471 patients were evaluated, of which 208 patients with mono HBV infection and 95 patients without HBV/HCV infection were excluded, leaving a total of 168 patients with positive HCV antibody (anti‐HCV) who were enrolled. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) patients with a diagnosis of aHCC (unresectable HCC with major vascular invasion or extra‐hepatic metastasis, or who were refractory to transhepatic arterial chemoembolization [TACE]); (b) liver reserve function Child‐Pugh score ≤ 8; (c) seropositive for anti‐HCV prior to initiation of sorafenib; and (d) received at least one dose of sorafenib. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) decompensated liver function Child‐Pugh score ≥ 9; and (b) underlying liver disease, except for HBV/HCV, such as autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, hemochromatosis, or Wilson disease. HCC diagnosis was performed according to regional guidelines 23 , 24 and included one of the following: (a) two radiological imaging modalities showing typical images of HCC (early enhancement in the arterial phase with early wash‐out in the delay portal‐venous phase); (b) one radiological imaging modality showing typical images of HCC combined with a serum alpha‐fetoprotein (AFP) level ≥ 400 ng/mL; and (c) cytological/histological diagnosis of HCC. The diagnosis and stage of HCC for each patient was further reviewed and confirmed by our HCC consensus meeting.

This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and Good Clinical Practice principles and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital. A waiver of consent was obtained for all patients.

Biochemistry and virology parameters were examined before sorafenib therapy, including complete blood cell count, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total bilirubin, albumin, prothrombin time (INR, international normal ratio), AFP levels, and levels of hepatitis B surface antigen, as well as anti‐HCV and HCV RNA. Not all patients with positive anti‐HCV exhibited HCV RNA levels because of the policy of reimbursement. Anti‐HCV was determined by a third‐generation enzyme immunoassay (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL). HCV RNA was measured using a qualitative polymerase chain reaction assay (CobasAmplicor Hepatitis C Virus Test, version 2.0; Roche Diagnostics, Branchburg, NJ; detection limit: 50 IU/mL). HCV RNA levels were quantified by a branched DNA assay (Versant HCV RNA3.0, Bayer, Tarrytown, NJ; quantification limit: 615 IU/mL) if qualitative HCV RNA seropositivity was present.

To evaluate treatment response to sorafenib, image examination was performed, including contrast enhanced computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, and liver function was assessed every 2 months based upon the sorafenib prescription. Once radiological tumor progression or decompensated liver function was identified, sorafenib therapy was no longer reimbursed by the national health insurance. For patients who did not meet reimbursement criteria, sorafenib therapy was prescribed based on the patient/physician decision and paid for by the patient.

The primary endpoint of the study was overall survival (OS), the period after initiation of sorafenib until death or loss to follow‐up). Secondary endpoints included progression free survival (PFS, the period after initiation of sorafenib until tumor progression, death or loss to follow‐up), time to liver decompensation (the period until liver decompensation with Child‐Pugh score ≥ 7 in patients with Child‐Pugh score < 7 at the initiation of sorafenib), and factors associated with survival. The final follow‐up date for outcome assessment was Aug. 2019. Patients were censored once they were lost to follow‐up or were unwilling to make additional visits. Patient status was further confirmed by the staff via phone call or email.

3. STATISTICS

Continuous variables are expressed as the median (range) and were compared using the Mann‐Whitney U test. Numbers and percentages were used to describe the distribution of categorical variables, which were compared using Chi‐squared and Fisher's exact tests. Survival and factors associated with survival were analyzed by Kaplan‐Meier actuarial curve with the log‐rank test and the Cox regression hazard model. All tests were two‐sided, and P < .05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using the SPSS 20.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

4. RESULTS

Table 1 shows the demographics of all 168 aHCC patients at initiation of sorafenib treatment. One hundred and eight (64.3%) patients were male with a median age of 66 years. Most (79.2%) patients presented with liver cirrhosis with a median fibrosis‐4 (FIB‐4) score of 3.96. Liver function of Child Pugh class A was identified in 155 (92.3%) patients. Sixty‐one (36.3%) patients had albumin‐bilirubin (ALBI) grade 1. Median AFP level was 282 ng/mL, and 72 (42.9%) patients had AFP levels ≥400 ng/mL. There were 14 (8.3%) patients with HBV co‐infection. Forty‐five (26.8%) patients had undetectable HCV RNA, including 32 patients with HCV eradicated by antiviral therapy (primarily interferon‐based therapy). Detectable HCV RNA was identified in 51 (30.4%) patients, with 14 patients never receiving interferon therapy. However, 72 (42.9%) patients did not have measurements of HCV RNA during the entire follow up period. At the start of sorafenib therapy, 9 (5.4%) patients were refractory to TACE, and 95 (56.5%) and 89 (53.0%) patients had major vessel invasion and extra‐hepatic metastasis, respectively. The median duration from initial diagnosis of HCC was 6.5 months, and the mean sorafenib dose was 440 mg/day.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of all aHCC patients at initiation of sorafenib treatment

| All N = 168 | Undetectable HCV RNA N = 45 | Detectable/unknown HCV RNA N = 123 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 66 (38‐87) | 64 (47‐81) | 67 (38‐87) | .055 |

| Male gender | 108 (64.3) | 29 (64.4) | 79 (64.2) | 1.000 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 133 (79.2) | 35 (77.8) | 98 (79.7) | .831 |

| White blood cell, x1000/mm3 | 6.2 (2.2‐25.1) | 5.7 (2.6‐25.1) | 6.3 (2.2‐22.3) | .762 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 12.2 (6.3‐16.1) | 12.7 (6.3‐15.5) | 12.0 (6.3‐16.1) | .005 |

| Platelet, x1000/mm3 | 156 (32‐512) | 149 (45‐357) | 157 (32‐512) | .512 |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.8 (2.2‐4.8) | 4.1 (2.9‐4.8) | 3.8 (2.2‐4.8) | <.001 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dl | 1.0 (0.2‐6.3) | 1.0 (0.4‐6.3) | 1.0 (0.2‐4.3) | .765 |

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 1.07 (0.91‐1.37) | 1.06 (0.96‐1.30) | 1.08 (0.91‐1.37) | .199 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 63 (21‐422) | 45 (21‐422) | 71 (23‐385) | .001 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 43 (15‐697) | 35 (17‐211) | 46 (15‐697) | .121 |

| Child‐Pugh class A | 155 (92.3) | 43 (95.6) | 112 (91.1) | .517 |

| FIB‐4 score | 3.96 (0.55‐30.97) | 3.93 (1.27‐14.99) | 4.07 (0.55‐30.97) | .205 |

| ALBI grade 1 | 61 (36.3) | 25 (55.6) | 36 (29.3) | .002 |

| Alpha fetoprotein, ng/ml | 282 (1‐356 640) | 58 (1‐210 380) | 336 (2‐356 640) | .037 |

| AFP ≥400 ng/mL | 72 (42.9) | 16 (35.6) | 56 (45.5) | .292 |

| HBV coinfection | 14 (8.3) | 5 (11.1) | 9 (7.3) | .528 |

| Refractory to TACE before sorafenib | 9 (5.4) | 3 (6.7) | 6 (4.9) | .702 |

| Major vessel invasion | 95 (56.5) | 23 (51.1) | 72 (58.5) | .482 |

| Extra‐hepatic metastasis | 89 (53.0) | 21 (46.7) | 68 (55.3) | .384 |

| aHCC at initial diagnosis | 76 (45.2) | 10 (22.2) | 66 (53.7) | <.001 |

| Duration from initial diagnosis of HCC, month | 6.5 (0‐163) | 26 (0‐146) | 3 (0‐163) | <.001 |

| Mean sorafenib dosing, mg/day | 440 (92‐800) | 600 (371‐800) | 440 (92‐800) | <.001 |

Note: Continuous variables are presented with median (range); categorical variables are presented with number (percentage). Statistics with Mann‐Whitney U test, and Chi‐squared and Fisher's exact tests.

Patients with undetectable HCV RNA exhibited significantly higher hemoglobin (12.7 vs. 12.0 mg/dL, P = .005) and albumin levels (4.1 vs. 3.8 g/dL, P < .001), mean sorafenib dose (600 vs. 440 mg/day, P < .001), and higher proportions of ALBI grade 1 (55.6 vs. 29.3%, P = .002). They also presented with lower AST (45 vs. 71 U/L, P = .001) and AFP levels (58 vs. 336 ng/mL, P = .037), as well as lower proportions of aHCC at initial diagnosis (22.2 vs. 53.7%, P < .001) with longer duration from initial diagnosis of HCC to sorafenib treatment (26 vs. 3 months, P < .001) (Table 1).

4.1. Overall survival and associated factors

Among all 168 patients, 27 remained alive at the end of follow‐up, 21 were lost to follow‐up, and the remaining 120 died before the end of follow‐up. Median OS for all patients was 232.0 (95% CI: 179.7‐284.3) days with a 12‐month survival rate of 35.8%. Of the three groups, patients with undetectable HCV RNA had an OS of 351.0 (95% CI: 242.0‐460.0) days, which was significantly superior to OS in patients with detectable or unknown HCV RNA (HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.32‐0.76, P = .001, Figure 1A). Further analysis regarding factors associated with OS identified white blood cell count, albumin, prothrombin time INR, AST level, Child‐Pugh class A score, FIB‐4 score, ALBI grade 1, AFP ≥400 ng/mL, major vessel invasion, aHCC at initial diagnosis, duration from initial diagnosis of HCC to sorafenib treatment, and undetectable HCV RNA as potentially associated factors. After adjusting with the above factors, undetectable HCV RNA (HR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.350‐0.903, P = .017) remained independently associated with OS (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of overall survival, A, and progression free survival, B, in patients with undetectable and detectable/unknown HCV RNA status

TABLE 2.

Factors associated with mortality (overall survival)

| Crude | Adjust | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age, years | 1.02 (0.998‐1.041) | .070 | ||

| Male gender | 0.98 (0.679‐1.424) | .927 | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | 0.73 (0.450‐1.177) | .195 | ||

| White blood cell, x1000/mm3 | 1.08 (1.029‐1.142) | .002 | 1.11 (1.054‐1.176) | <.001 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 0.92 (0.838‐1.004) | .060 | ||

| Platelet, x1000/mm3 | 1.00 (1.000‐1.003) | .135 | ||

| Albumin, g/dl | 0.46 (0.329‐0.644) | <.001 | 0.44 (0.216‐0.897) | .024 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dl | 1.19 (0.975‐1.440) | .088 | ||

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 10.64 (1.274‐88.826) | .029 | 5.19 (0.364‐74.074) | .225 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 1.00 (1.001‐1.006) | .007 | 1.00 (0.997‐1.003) | .994 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 1.00 (0.999‐1.004) | .302 | ||

| Child‐Pugh class A | 0.52 (0.282‐0.943) | .031 | 1.82 (0.720‐4.611) | .205 |

| FIB‐4 score | 1.07 (1.022‐1.115) | .004 | 1.08 (1.026‐1.141) | .004 |

| ALBI grade 1 | 0.53 (0.359‐0.792) | .002 | 1.41 (0.732‐2.733) | .303 |

| AFP ≥400 ng/mL | 1.95 (1.359‐2.795) | <.001 | 1.80 (1.237‐2.607) | .002 |

| HBV coinfection | 0.90 (0.472‐1.727) | .757 | ||

| Refractory to TACE before sorafenib | 1.28 (0.594‐2.748) | .530 | ||

| Major vessel invasion | 1.60 (1.104‐2.321) | .013 | 1.34 (0.898‐1.992) | .153 |

| Extra‐hepatic metastasis | 0.88 (0.612‐1.258) | .477 | ||

| aHCC at initial diagnosis | 1.56 (1.085‐2.249) | .016 | 0.91 (0.581‐1.438) | .698 |

| Duration from initial diagnosis of HCC, month | 0.99 (0.987‐0.998) | .012 | 1.00 (0.989‐1.003) | .222 |

| Mean sorafenib dosing, mg/day | 1.00 (0.998‐1.000) | .112 | ||

| Undetectable HCV RNA | 0.49 (0.318‐0.756) | .001 | 0.56 (0.350–0.903) | .017 |

Note: Statistics with Cox regression hazard model.

4.2. Progression free survival and associated factors

Of the 168 patients, 143 patients had follow up imaging studies to evaluate sorafenib treatment response. Overall, only 24 (16.8%) patients achieved disease control (partial response or stable disease) at the end of follow up. There was no significant difference in the rate of disease control between patients with undetectable and detectable/unknown HCV RNA (18.2% vs. 16.2%, P = .810). Median PFS of all patients was 92.0 (95% CI: 63.3‐120.7) days. Patients with undetectable HCV RNA had a trend toward longer PFS compared to patients with detectable or unknown HCV RNA status (155.0 vs. 86.0 days, HR 0.68, 95% CI: 0.46‐1.00, P = .053, Figure 1B). Further analysis regarding factors associated with PFS revealed liver cirrhosis, albumin, AST level, FIB‐4 score, ALBI grade 1, and AFP ≥400 ng/mL as significantly associated with PFS. Undetectable HCV RNA was not independently associated with PFS after adjustment with the above factors (Supplementary Table 1).

Subgroup analyses revealed that undetectable HCV RNA was associated with favorable OS in most subgroups. However, undetectable HCV RNA was associated with a favorable PFS only in patients with ALT <80 U/L and FIB‐4 < 3.25 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Overall survival and progression free survival in selected subgroups of patients

| Subgroup | No. of patients | Overall survival | No. of patients | Progression‐free survival | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undetectable RNA | Detectable and unknown | Undetectable RNA | Detectable and unknown | Hazard ratio for death (95% CI) | Undetectable RNA | Detectable and unknown | Undetectable RNA | Detectable and unknown | Hazard ratio for death (95% CI) | |

| No of events | No of events | |||||||||

| Overall | 45 | 123 | 27 | 93 | 0.49 (0.32–0.76) | 44 | 99 | 36 | 83 | 0.68 (0.46‐1.00) |

| Age | ||||||||||

| <65 years | 23 | 41 | 13 | 31 | 0.38 (0.20‐0.73) | 23 | 35 | 19 | 30 | 0.58 (0.32‐1.04) |

| ≥65 years | 22 | 82 | 14 | 62 | 0.65 (0.36‐1.16) | 21 | 64 | 17 | 53 | 0.81 (0.47‐1.40) |

| Albumin | ||||||||||

| <3.5 g/dL | 5 | 38 | 4 | 33 | 0.50 (0.18‐1.42) | 5 | 26 | 4 | 22 | 0.87 (0.30‐2.56) |

| ≥3.5 g/dL | 40 | 85 | 23 | 60 | 0.53 (0.32‐0.86) | 39 | 73 | 32 | 61 | 0.65 (0.42‐1.01) |

| AST | ||||||||||

| <80 U/L | 36 | 82 | 21 | 59 | 0.52 (0.31‐0.85) | 35 | 71 | 28 | 58 | 0.66 (0.42‐1.05) |

| ≥80 U/L | 9 | 41 | 6 | 34 | 0.46 (0.19‐1.11) | 9 | 28 | 8 | 25 | 0.84 (0.38‐1.86) |

| ALT | ||||||||||

| <80 U/L | 38 | 99 | 23 | 78 | 0.42 (0.26‐0.68) | 37 | 79 | 29 | 67 | 0.57 (0.36‐0.88) |

| ≥80 U/L | 7 | 24 | 4 | 15 | 0.83 (0.27‐2.53) | 7 | 20 | 7 | 16 | 1.43 (0.58‐3.49) |

| FIB‐4 | ||||||||||

| <3.25 | 20 | 44 | 11 | 30 | 0.48 (0.24‐0.97) | 19 | 36 | 16 | 29 | 0.50 (0.27‐0.95) |

| ≥3.25 | 25 | 79 | 16 | 63 | 0.52 (0.30‐0.91) | 25 | 63 | 20 | 54 | 0.86 (0.52‐1.45) |

| ALBI | ||||||||||

| Gr. 1 | 25 | 36 | 15 | 20 | 0.74 (0.38‐1.45) | 24 | 33 | 19 | 26 | 0.54 (0.29‐1.01) |

| Gr. 2/3 | 20 | 87 | 12 | 73 | 0.44 (0.24‐0.82) | 20 | 66 | 17 | 57 | 0.93 (0.54‐1.59) |

| AFP | ||||||||||

| <400 ng/mL | 29 | 67 | 15 | 45 | 0.57 (0.32‐1.02) | 28 | 55 | 21 | 42 | 0.67 (0.39‐1.13) |

| ≥400 ng/mL | 16 | 56 | 12 | 48 | 0.41 (0.21‐0.80) | 16 | 44 | 15 | 41 | 0.76 (0.42‐1.38) |

| Sorafenib from dx of HCC | ||||||||||

| ≤3 months | 10 | 62 | 7 | 46 | 0.49 (0.22‐1.10) | 10 | 49 | 7 | 39 | 0.54 (0.24‐1.23) |

| >3 months | 35 | 61 | 20 | 47 | 0.54 (0.32‐0.91) | 34 | 50 | 29 | 44 | 0.69 (0.43‐1.11) |

Note: Statistics with Cox regression hazard model.

Of the 119 patients who showed disease progression while on sorafenib, 47 (39.5%) received subsequent therapy for aHCC after the end of sorafenib treatment. Half of patients with undetectable HCV RNA (19/36, 52.8%) and 33.7% of patients with detectable/unknown HCV RNA received subsequent therapy. There was no significant difference between these two groups in receiving subsequent therapy after disease progression (P = .066). In patients with disease progression, subsequent therapy was a significant factor associated with overall survival (HR: 0.33, 95% CI: 0.21‐0.52, P < .001). After adjustment for HCV RNA status, both subsequent therapy (HR: 0.33, 95% CI: 0.21‐0.53, P < .001) and undetectable HCV RNA (HR: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.33‐0.87, P < .001) remained significantly associated with overall survival.

4.3. Prolonged time to Child‐Pugh class B score in patients with undetectable HCV RNA

We further analyzed the time to Child‐Pugh B in patients with Child‐Pugh A at the beginning of sorafenib treatment. The median time to Child‐Pugh B for all Child‐Pugh A patients was 145.0 (95% CI: 105.6‐184.4) days. Of the 155 Child‐Pugh A patients, 43 exhibited undetectable HCV RNA. Demographics between Child‐Pugh A patients with undetectable and detectable/unknown HCV RNA were similar to that observed in all patients (Supplementary Table 2). There was also no difference in response to sorafenib between Child‐Pugh A patients with undetectable and detectable/unknown HCV RNA status. Compared to patients with detectable/unknown HCV RNA, patients with undetectable HCV RNA had significantly prolonged time to Child‐Pugh B (279.0 vs. 118.0 days, HR 0.59, 95% CI: 0.38‐0.92, P = .020, Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of time to child‐Pugh B between patients with undetectable and detectable/unknown HCV RNA

4.4. Eradication of HCV by DAA prolonged overall survival and progression free survival in viremia patients

Among the 51 patients with detectable HCV RNA at sorafenib initiation, five received direct acting antiviral (DAA) therapy 2, 3, 4, 8, and 9 months after sorafenib prescription. All five patients achieved sustained virological response 12 weeks after stopping DAA. Further analysis revealed patients who received DAA therapy exhibited significantly prolonged OS (not reached vs. 161.0 days, HR 0.11, 95% CI: 0.02‐0.81, P = .030, Figure 3A) and PFS (not reached vs. 81.0 days, HR 0.23, 95% CI: 0.06‐0.99, P = .048, Figure 3B) compared to patients who did not receive DAA therapy. Owing to the small case numbers, a large scale, prospective study is needed to confirm the survival benefit of eradication of HCV by DAA after the diagnosis of aHCC.

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of overall survival, A, and progression free survival, B, between patients with detectable HCV RNA with and without DAA therapy

5. DISCUSSION

Curing HCV infection is a must and the benefits of HCV eradication have been widely validated. Successful eradication of HCV infection leads to a significant benefit in reducing risks of LC and HCC, as well as in improving survival among chronic hepatitis C (CHC) patients. The current study, to our knowledge, is the first showing the benefit of improving survival was extended to aHCC patients without viremia who received sorafenib. Our study thus provides important evidence for the management of aHCC CHC patients, despite their limited life expectancy before initiation of oncological targeted therapy.

Although without a satisfactory successful rate, SVR by interferon‐based therapy leads to a markedly decreased risk of liver failure and HCC. 25 , 26 , 27 New DAA therapy, which is the mainstream CHC treatment, demonstrated an extremely high cure rate of over 95%. 28 Recent studies have consistently reported similar results that HCC risk and liver‐related events are markedly decreased after DAA therapy. 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 In addition to decreasing the risk of HCC, DAA therapy also improves survival in patients after successful treatment of early HCC. 33 A recent study also showed a 60% to 70% improvement in 5‐year overall survival in HCV infected HCC patients who achieved HCV SVR by DAA. 34

However, whether HCV eradication is beneficial in those with limited life expectancy remains controversial. For patients with decompensated cirrhosis, recent data demonstrated that DAA therapy was associated with improved outcomes in patients with Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease (MELD) below 18 or 20. 35 , 36 However, liver transplant remains an urgent need in patients with higher MELD score, despite their HCV infection being successfully cured by DAA. EASL guidelines, therefore, recommend HCV infection be treated after liver transplantation in patients with decompensated cirrhosis without HCC awaiting liver transplantation with MELD scores ≥18‐20. 20 AASLD guidelines furthermore recommend that treatment is recommended, except in those with a short life expectancy, in whom liver disease should be managed in consultation with an expert. 21 , 22

Approval of sorafenib prolongs survival in advanced HCC patients to more than 10 months. Newly developed agents have further extended life expectancy to more than 1 year. Despite these advances, low treatment response means that advanced HCC patients still experience poor outcomes with relatively short life expectancy. Whether these patients benefit from HCV eradication was unknown. A survival benefit of HCV eradication in aHCC patients has only rarely been investigated. 19 Our results demonstrated that HCV eradication before sorafenib treatment significantly prolonged the time to treatment failure and improved overall survival. Survival benefit was assessed by preserved liver function after HCV eradication from our multivariate regression analysis. In the present study, we demonstrated improved overall survival and prolonged time to Child‐Pugh B in patients with HCV eradication. These findings further indicated the survival benefit was from preserved liver function after HCV eradication. Another novel finding was that the survival benefit remained in patients with detectable HCV RNA who received DAA therapy after diagnosis of advanced HCC. This result suggests the utility of antiviral treatment in these patients.

There are some limitations in the present study. First, HCV RNA was not measured in a large proportion of patients. In the past, advanced HCC patients were not indicated for pegylated interferon due to the side effects. Since anti‐viral treatment was not prescribed, HCV RNA is usually not measured by physicians. In a prior report, positive HCV RNA was found in higher to 84% of HCV related HCC patients. 37 We considered a positive HCV RNA in most of these patients and categorized them together with patients with positive HCV RNA. Second, owing to the retrospective recruitment of patients, only parameters measured in routine clinical practice were obtained, and several known confounding factors were not controlled in the present study. Third, there might be selection bias for those who received DAA therapy after the diagnosis of aHCC and sorafenib treatment. Owing to this and the small case numbers of DAA therapy, a further large scale, prospective study including all critical confounding factors is necessary to confirm these findings.

In conclusion, HCV RNA measurement is recommended, even in patients with aHCC, in whom life expectancy is 1 year or less. Reducing HCV viremia preserves liver function with a survival benefit in advanced HCC patients on sorafenib treatment. Therefore, antiviral therapy is recommended, even after a diagnosis of advanced HCC.

Supporting information

Supplementary Table 1 Factors associated with disease progression (progression free survival).

Supplementary Table 2. Comparison of demographics between patients with Child‐Pugh class A with undetectable and detectable/unknown HCV RNA at initiation of sorafenib treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the secretary aid of the Taiwan Liver Research Foundation (TLRF). They did not influence how the study was conducted or the approval of this manuscript. The authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Yeh M‐L, Kuo H‐T, Huang C‐I, et al. Eradication of hepatitis C virus preserve liver function and prolong survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients with limited life expectancy. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2021;37:145–153. 10.1002/kjm2.12303

Funding information Kaohsiung Medical University, Grant/Award Numbers: 107CM‐KMU‐06, KMU‐DK107004, MOST 108‐2314‐B‐037‐066‐MY3, MOST 108‐2314‐B‐037‐101; Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Grant/Award Numbers: KMUH106‐6R09, MOHW108‐TDU‐B‐212‐133006

REFERENCES

- 1. Bosch FX, Ribes J, Diaz M, Cleries R. Primary liver cancer: Worldwide incidence and trends. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5 Suppl 1):S5–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Llovet JM, Schwartz M, Mazzaferro V. Resection and liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25(2):181–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shiina S, Teratani T, Obi S, Sato S, Tateishi R, Fujishima T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of radiofrequency ablation with ethanol injection for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(1):122–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9319):1734–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: The BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19(3):329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia‐Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase III randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(1):25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yeh ML, Huang CF, Huang CI, Hsieh MY, Hou NJ, Lin IH, et al. The prognostic factors between different viral etiologies among advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving sorafenib treatment. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2019;35(10):624–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Forner A, Reig ME, de Lope CR, Bruix J. Current strategy for staging and treatment: The BCLC update and future prospects. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30(1):61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn R, Sirlin CB, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, et al. Aasld guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):358–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. European Association For The Study Of The L, European Organisation For R, Treatment Of C. EASL‐EORTC clinical practice guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56(4):908–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first‐line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomised phase 3 non‐inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10126):1163–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): A randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abou‐Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, El‐Khoueiry AB, Rimassa L, Ryoo BY, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced and progressing hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(1):54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhu AX, Kang YK, Yen CJ, Finn RS, Galle PR, Llovet JM, et al. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased alpha‐fetoprotein concentrations (REACH‐2): A randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(2):282–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bruix J, Cheng AL, Meinhardt G, Nakajima K, De Sanctis Y, Llovet J. Prognostic factors and predictors of sorafenib benefit in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: Analysis of two phase III studies. J Hepatol. 2017;67(5):999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shao YY, Shau WY, Chan SY, Lu LC, Hsu CH, Cheng AL. Treatment efficacy differences of sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta‐analysis of randomized clinical trials. Oncology. 2015;88(6):345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kawaoka T, Aikata H, Teraoka Y, Inagaki Y, Honda F, Hatooka M, et al. Impact of Hepatitis C virus eradication on the clinical outcome of patients with Hepatitis C virus‐related advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with Sorafenib. Oncology. 2017;92(6):335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. European Association for the Study of the Liver . EASL recommendations on treatment of Hepatitis C 2018. J Hepatol. 2018;69(2):461–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Panel AIHG. Hepatitis C guidance: AASLD‐IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2015;62(3):932–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. A‐IHG P, Hepatitis C. Guidance 2018 update: AASLD‐IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating Hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(10):1477–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68(2):723–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. European Association for the Study of the Liver . Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):182–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aleman S, Rahbin N, Weiland O, Davidsdottir L, Hedenstierna M, Rose N, et al. A risk for hepatocellular carcinoma persists long‐term after sustained virologic response in patients with hepatitis C‐associated liver cirrhosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(2):230–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, Wedemeyer H, Dufour JF, Lammert F, et al. Association between sustained virological response and all‐cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA. 2012;308(24):2584–2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cardoso AC, Moucari R, Figueiredo‐Mendes C, Ripault MP, Giuily N, Castelnau C, et al. Impact of peginterferon and ribavirin therapy on hepatocellular carcinoma: Incidence and survival in hepatitis C patients with advanced fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2010;52(5):652–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yeh ML, Huang CF, Huang CI, Holmes JA, Hsieh MH, Tsai YS, et al. Hepatitis B‐related outcomes following direct‐acting antiviral therapy in Taiwanese patients with chronic HBV/HCV co‐infection. J Hepatol. 2020;73(1):62–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van der Meer AJ, Feld JJ, Hofer H, Almasio PL, Calvaruso V, Fernandez‐Rodriguez CM, et al. Risk of cirrhosis‐related complications in patients with advanced fibrosis following hepatitis C virus eradication. J Hepatol. 2017;66(3):485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Singer AW, Reddy KR, Telep LE, Osinusi AO, Brainard DM, Buti M, et al. Direct‐acting antiviral treatment for hepatitis C virus infection and risk of incident liver cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(9):1278–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nahon P, Bourcier V, Layese R, Audureau E, Cagnot C, Marcellin P, et al. Eradication of Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with cirrhosis reduces risk of liver and non‐liver complications. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(1):142–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Asch SM, Cao Y, Li L, El‐Serag HB. Long‐term risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV patients treated with direct acting antiviral agents. Hepatology. 2020;71(1):44–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cabibbo G, Celsa C, Calvaruso V, Petta S, Cacciola I, Cannavo MR, et al. Direct‐acting antivirals after successful treatment of early hepatocellular carcinoma improve survival in HCV‐cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 2019;71(2):265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dang H, Yeo YH, Yasuda S, Huang CF, Iio E, Landis C, et al. Cure with interferon free DAA is associated with increased survival in patients with HCV related HCC from both east and west. Hepatology. 2020;71(6):1910–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fernandez Carrillo C, Lens S, Llop E, Pascasio JM, Crespo J, Arenas J, et al. Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in patients with cirrhosis and predictive value of model for end‐stage liver disease: Analysis of data from the Hepa‐C registry. Hepatology. 2017;65(6):1810–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sandmann L, Dorge P, Wranke A, Vermehren J, Welzel TM, Berg CP, et al. Treatment strategies for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis due to hepatitis C virus infection eligible for liver transplantation: Real‐life data from five German transplant centers. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31(8):1049–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Petruzziello A, Marigliano S, Loquercio G, Coppola N, Piccirillo M, Leongito M, et al. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes distribution among hepatocellular carcinoma patients in southern Italy: A three year retrospective study. Infect Agents Cancer. 2017;12:52. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1 Factors associated with disease progression (progression free survival).

Supplementary Table 2. Comparison of demographics between patients with Child‐Pugh class A with undetectable and detectable/unknown HCV RNA at initiation of sorafenib treatment.