Abstract

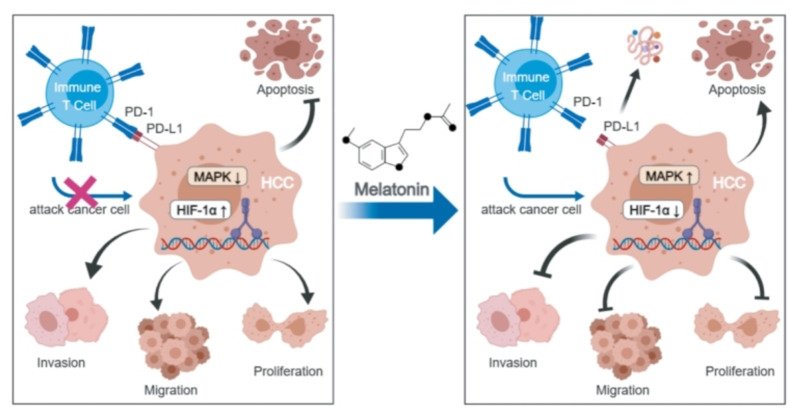

Melatonin, also known as the pineal hormone, is secreted by the pineal gland and primarily regulates circadian rhythms. Additionally, it possesses immunomodulatory properties and anticancer effects. However, its specific mechanism in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains unclear, particularly regarding its effect on HCC-mediated immune escape through PD-L1 expression.In this study, in vitro experiments were conducted using Huh7 and HepG2 HCC cells. Melatonin treatment was applied to both cell types to observe changes in malignant phenotypes. Additionally, melatonin-pretreated Huh7 or HepG2 cells were co-cultured with T cells to simulate the tumor microenvironment. The results showed that melatonin inhibited cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, as well as reduced PD-L1 expression in cancer cells, exhibiting similar anti-cancer effects in the co-culture system. In vivo experiments involved establishing ascitic HCC mouse models using H22 cells, followed by subcutaneous tumor models in Balb/c nude and Balb/c wild-type mice. Melatonin inhibited tumor growth and suppressed PD-L1 expression in cancer tissues in both subcutaneous tumor models, and it increased T lymphocyte activity in the spleen of Balb/c wild-type mice. Overall, the in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated that melatonin has dual anti-cancer effects in HCC: direct intrinsic anti-cancer activity and enhancement of anti-tumor immunity by reducing PD-L1 expression thereby inhibiting cancer immune escape. Furthermore, a decrease in the expression of the upstream molecule HIF-1α of PD-L1 and an increase in the expression levels of JNK, P38, and their phosphorylated forms were detected. Thus, the mechanism by which melatonin reduces PD-L1 may involve the downregulation of HIF-1α expression or the activation of the MAPK-JNK and MAPK-P38 pathways. This provides new insights and strategies for HCC treatment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-93486-4.

Keywords: Melatonin, Hepatocellular carcinoma, PD-L1, Immune escape, Anticancer

Subject terms: Pharmacology, Cancer

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a prevalent malignancy worldwide, imposes a significant health burden with high incidence and mortality rates1. Despite advancements in treatment modalities2, the prognosis for HCC remains poor, which is closely related to tumor immune escape. immune escape mediated by upregulated programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), a crucial immune checkpoint, is the significant challenge to treatment efficacy3–5. It is predominantly located on the surface of tumor cells, and can bind to programmed death-1 (PD-1) protein on immune cells, this interaction leads to the impairment of immune cells’ ability to recognize and attack cancer cells, thereby facilitating tumor immune escape6, which promotes tumor proliferation, development, and metastasis. PD-L1 is generally overexpressed in HCC cells compared to normal hepatic cells, which help HCC cells escaped from the attack of immune cells7.

To suppress the immune escape during HCC treatment, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors were used as adjunct therapies. While they have shown some effectiveness, clinical trial data indicate that their therapeutic outcomes are not significant8,9. Especially in advanced cases, high expression of PD-L1 in the HCC microenvironment limits the efficacy. Therefore, finding effective strategies to reduce PD-L1 expression has become a crucial direction in HCC treatment research. Such approaches could enhance the efficacy of existing immunotherapies and potentially extend to the immunotherapy of other cancers.

Melatonin, a neuroendocrine hormone secreted by the pineal gland, plays a crucial role in maintaining circadian rhythms and possesses sedative, anxiolytic, immunomodulatory, and anti-tumor properties. In recent years, the role of melatonin in tumor immunomodulation has been increasingly recognized, particularly in regulating key factors in immune escape. Research indicates that melatonin may suppress immune escape in cancers such as lung cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and gastric cancer by downregulating the expression level of PD-L1, thereby exerting its anti-cancer effects10–12. In HCC, melatonin and circadian rhythm disruptions were identified as independent risk factors13. Studies have shown a clear association between endogenous melatonin levels and HCC risk, with dietary intake also displaying a linear relationship with HCC incidence14. Although some studies have confirmed the anti-cancer effects of melatonin on HCC15–17, the specific effects of melatonin on immune escape within the HCC microenvironment remain unclear.

Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap by investigating the effects of melatonin on PD-L1-mediated immune escape in HCC and its anti-cancer efficacy, and to explore the potential mechanisms involved. This research could provide new insights and theoretical bases for the anti-cancer mechanism of melatonin in HCC, and further promote the formulation and optimization of HCC treatment strategies. Additionally, it might offer a theoretical foundation and prospective applications for the treatment strategies of other types of cancer.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2 was purchased from the BeNa Culture Collection (BNCC, Wuhan, China), while Huh7 was obtained from the China Typical Culture Collection Center (CCTCC, Wuhan, china). Cells were cultured in high glucose DMEM medium18–20 (4.5 g/L) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% glutamine, and maintained in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5% CO2. All cells used in this research were routinely screened and found to be free of mycoplasma.

Animal experiment

All animal experiments were conducted at the Animal Experimental Center of Gannan Innovation and Transformation Medical Research Institute (Ganzhou, China) and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University ( NO.LLSC2023227). All animal experiment was conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines. The care and treatment of mice were performed according to the guidelines for laboratory animal care. And all animals were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd (Beijing Sibeifu).

(1) H22 cells for subcutaneous tumor model:

Balb/c nude male mice(6–8 weeks old), purchased from Beijing Sibeifu, were acclimatized for 7 days with a regular 12-hour light-dark cycle before the experiment. H22 cells (2 × 106, 200uL) were injected subcutaneously into the right axilla of the mice. They were divided into control and melatonin treatment groups. The treatment group received melatonin (Selleck, USA) via intragastric administration at a dose of 100 mg/kg once daily for 10 consecutive days, while the control group received saline via the same method. Tumor growth was measured using calipers. The mice were then euthanized by cervical dislocation, and the tumor tissues and spleens were harvested and weighed, and the tumor tissues were fixed in neutral buffered formalin.

(2) Extraction of ascitic-type H22 cells:

KM male wild-type mice (6–8 weeks old), purchased from Beijing Sibeifu, were acclimatized for 7 days with a regular 12-hour light-dark cycle before the experiment. H22 cells (1 × 107,200uL) were injected into the peritoneal cavity of the mice, which were then housed under normal conditions. Upon the accumulation of abnormal fluid volume in the mice, they were euthanized by cervical dislocation. Ascitic fluid was collected and clarified on ice. Under sterile conditions, the ascitic fluid was washed with physiological saline to remove impurities, followed by red blood cell lysis. The cells were repeatedly washed to obtain ascitic-type H22 cells for subsequent inoculation and modeling.

(3) Ascitic-type H22 cells for subcutaneous tumor model:

Balb/c male wild-type mice (6–8 weeks old), purchased from Beijing Sibeifu, were acclimatized for 7 days and then subcutaneously injected with ascitic-type H22 cells (5 × 106, 200uL) into the right axilla. The mice were divided into control and melatonin treatment groups. The treatment group received melatonin (Selleck, USA) via intragastric administration at a dose of 100 mg/kg once daily for 9 consecutive days, while the control group received saline via the same method. Tumor growth was measured using calipers. The mice were then euthanized by cervical dislocation, and the tumor tissues and spleens were harvested and weighed, and the tumor tissues were fixed in neutral buffered formalin.Tumor growth was measured using calipers.The mice were then euthanized by cervical dislocation and the tumor tissues and spleens were harvested and weighed. Then the tumor tissues were fixed in neutral buffered formalin. The spleens were collected to measure the activity of lymphocytes in mice.

Cell viability assays

Huh7 and HepG2 cells (5 × 103 cells/well) were seeded into a 96-well plate and incubated with melatonin (Selleck, USA) at concentrations of 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 mM for 24 and 48 h. Afterward, the cells were fed with growth medium containing Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) reagent (Dojindo Molecular, Japan) and further incubated for 2 h. The absorbance at 450 nm of the formaldehyde dye was measured using a spectrophotometer. Cell viability was expressed as a percentage relative to untreated control cells.

Colony formation assay

Huh7 and HepG2 cells (3 × 103 cells/well) were seeded into 6-well plates and treated with different concentrations of melatonin (0.5 mM and 1 mM) for 14 days. The medium was changed every 2–3 days. After incubating the cells for 14 days, the medium was discarded, and the wells were washed twice with 1x PBS. Subsequently, the wells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution (Beyotime) at room temperature for 15 min. Then 1% crystal violet solution was added for staining at room temperature. The formed clone colonies were analyzed using Image-Pro Plus software.

Wound healing assay

Huh7 cells (1.4 × 106 cells/well) and HepG2 cells (2.8 × 106 cells/well) were seeded into 6-well plates and cultured in a CO2 incubator until reaching confluency of 100%. After the cells adhered to the bottom, scratches were made using a straight edge guided by a micropipette with a medium-sized tip. After scratching, the detached cells were washed away with 1xPBS, and DMEM basal medium with 4.5 g/L glucosecontaining different concentrations of melatonin (0.5 mM and 1 mM) (prepared without FBS) were added. Images of the scratches were captured at 0 h, 24 h, and 48 h using a microscope (Nikon, Japan).

Transwell migration/invasion assay

Huh7 and HepG2 cells were cultured in DMEM basal medium without FBS. Different concentrations of melatonin (0.5 mM and 1 mM) were added to the medium, and corresponding cell densities were adjusted. Huh7 cells (7 × 104 cells/well) and HepG2 cells (13 × 104 cells/well) were seeded in the upper chamber of Transwell inserts with a pore diameter of 8 μm (Corning). The lower chamber was filled with DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% glutamine. After a 15-minute incubation, the inserts were placed in a CO2 incubator for 48 h. Following incubation for 48 h, the inserts were removed, and the lower chamber was washed twice with 1xPBS. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Beyotime) for 15 min at room temperature, followed by two washes with 1xPBS. Then, the cells were stained with 1% crystal violet dye for 3 min at room temperature. After staining, the upper chamber cells were gently wiped off with a cotton swab, and images were captured under a Nikon (Japan) microscope.

For the Transwell invasion assay, the protocol was identical to the migration assay, except that the upper chamber was pre-coated with a mixture of matrix gel (Corning) diluted in medium. After a 2-hour incubation, cells were seeded into the upper chamber, and the remaining procedures and materials were consistent with the Transwell migration assay.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer containing a mixture of protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, Switzerland). Proteins of different sizes were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, USA) pre-activated with methanol. The membranes were then blocked with 5% blocking buffer at room temperature for 30 min, followed by washing with TBST buffer three times for 5 min each. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the corresponding primary antibodies. After washing the membranes three times with TBST buffer for 5 min each, species-specific secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, USA) were incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Protein bands were visualized using the ChemiDoc™ Imaging System (Bio-Rad, USA). Specific primary antibodies used were as follows:

| Antibody | Source | Identifier |

|---|---|---|

| β-ACTIN | Abclonal | AC026 |

| PD-L1 | Abclonal | A1645 |

| P38 | Abclonal | A14401 |

| P-P38 | Cell signaling technology | 4511 |

| P-JNK | Cell signaling technology | 4668 |

| JNK | Cell signaling technology | 9252 |

| HIF-1α | Cell signaling technology | 14,179 |

| Cleaved-Ccaspase-3 | Proteintech | 19677-1-AP |

| BCL2 | Biolight | MA00081HuM10-C2F |

Fluorescent quantitative PCR detection technique

(1) RNA Extraction: Cell samples were collected using Trizol reagent. One-fifth volume of chloroform was added, followed by vortexing for 15 s, and then incubated on ice for 10 min. After centrifugation at 4 °C 12,000 rpm for 15 min, the upper aqueous phase was carefully transferred to a new RNase-free centrifuge tube. An equal volume of isopropanol was added, mixed, and then incubated on ice for 20 min. After centrifugation at 4 °C, 12,000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the RNA pellet was washed with 75% ethanol (prepared with DEPC-treated water) at 4 °C, followed by centrifugation at 7500 rpm for 5 min. This washing step was repeated once, and then the tube was opened and left to air dry at room temperature. Finally, DEPC-treated water was added to dissolve the RNA. The concentration and purity of RNA were measured using the absorbance at 260 nm and the ratio of 260/280 nm using a NanoDrop ND-1000(NanoDrop, Wilmington, USA) spectrophotometer.

(2) Reverse Transcription Reaction: One microgram of RNA was used to synthesize the first-strand cDNA using the Vazyme HiScript III RT SuperMix for qPCR (+ gDNA wiper) kit.

(3) qPCR Detection: Real-time PCR was performed using the Real Universal Color PreMix (SYBR Green) (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) with a threefold dilution in a 10 uL reaction mixture. β-Actin was used as an internal control. The primer sequences used were as follows:

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| β-ACTIN(homo) | CATGTACGTTGCTATCCAGGC | CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGAT |

| BAX(homo) | CCCGAGAGGTCTTTTTCCGAG | CCAGCCCATGATGGTTCTGAT |

| BCL2(homo) | GGTGGGGTCATGTGTGTGG | CGGTTCAGGTACTCAGTCATCC |

| BAD(homo) | CCCAGAGTTTGAGCCGAGTG | CCCATCCCTTCGTCGTCCT |

| BCL2-L1(homo) | GAGCTGGTGGTTGACTTTCTC | TCCATCTCCGATTCAGTCCCT |

| PD-L1(homo) | ATTTGCTGAACGCCCCATAC | TCCAGATGACTTCGGCCTTG |

| GZMB(homo) | TACCATTGAGTTGTGCGTGGG | GCCATTGTTTCGTCCATAGGAGA |

| IL-2(homo) | TCCTGTCTTGCATTGCACTAAG | CATCCTGGTGAGTTTGGGATTC |

| IFN-γ(homo) | TCGGTAACTGACTTGAATGTCCA | TCGCTTCCCTGTTTTAGCTGC |

| GZMB(mouse) | TCATGCTGCTAAAGCTGAAGAG | CCCGCACATATCTGATTGGTTT |

| IL-2(mouse) | TGAGCAGGATGGAGAATTACAGG | GTCCAAGTTCATCTTCTAGGCAC |

| IFN-γ(mouse) | GCCACGGCACAGTCATTGA | TGCTGATGGCCTGATTGTCTT |

Co-culture of T cells and hepatocellular carcinoma cells

The isolation and purification of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from the blood samples of healthy volunteers were performed under the approval of the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University (LLSC2023141). All procedures conformed strictly to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and adhered to all relevant ethical guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians, with informed consent forms signed by all volunteers prior to blood collection.

PBMCs were isolated and purified from healthy human blood using the Ficoll density gradient centrifugation method. The PBMCs were then labeled with CD3-PE and 7-AAD flow cytometry antibodies (BioLegend, USA), and CD3+ T cells were sorted using a FACSAria flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA).

The T cells were rested overnight in complete culture medium (1640 medium containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin) and then activated by stimulation with anti-CD3 (clone OKT3, eBioscience, USA) and anti-CD28 (clone CD28.2, eBioscience, USA) antibodies for 24 h to induce activation. The activated T cells were collected.

Before co-culture, HepG2 and Huh7 cells were labeled with CellTrace Far Red flow cytometry cell proliferation antibody (Invitrogen, USA), plated in a 96-well plate (8000 cells/well), and allowed to adhere overnight. Prior to coculturing with T cells, Huh7 or HepG2 cells were pre-treated with melatonin at a dose of 1 mM for 12 h. Afterward, the melatonin-containing medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium for a 48-hour coculture period. The co-culture was performed at a ratio of 1:10 (HCC cells: T cells) .

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells were collected and washed with PBS containing 1% BSA or 2% FBS. After washing, Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis detection kit (Yeasen, Shanghai, China) was used to detect apoptosis of HepG2 and Huh7 cells. Alternatively, after cell washing, cells were fixed with 70% ethanol and treated with 50 ug/ml RNase A, followed by staining with 50 ug/ml propidium iodide (PI, Yeasen, China) at room temperature for 30 min to detect the cell cycle of HepG2 and Huh7 cells. HepG2 and Huh7 cells (pre-labeled with CellTrace Far Red) were directly collected and analyzed for cell proliferation using flow cytometry (BD Accuric6 plus, USA). Flow cytometry data were analyzed using Flowjo version 10 software.

Histopathological hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) staining

Tumor pathological tissues were collected, fixed, trimmed, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. Paraffin sections were then deparaffinized, hydrated, and sequentially stained with hematoxylin and eosin to stain the cell nuclei and cytoplasm, followed by dehydration and mounting. Finally, microscopic examination and image acquisition analysis were performed.

Pathological immunohistochemistry

Tumor pathological tissues were collected, fixed, trimmed, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. Paraffin sections were then deparaffinized, hydrated, and underwent EDTA high-temperature antigen retrieval according to the requirements of the primary antibody used. After retrieval, the sections were rinsed with ddH2O, incubated with H2O2, washed with PBS, blocked, and then incubated overnight with the primary antibody. Subsequently, they were incubated with the secondary antibody, followed by color development using DAB working solution. Counterstaining with hematoxylin was performed, followed by dehydration, clearing, and mounting for photography. Image acquisition and analysis were conducted.

Specific primary antibodies used were as follows:

| Antibody | Source | Identifier |

|---|---|---|

| CD8 | Servicebio | GB15068-50 |

| Ki-67 | Meack | AB9260 |

| E-CAD | Santa cruZ | Sc-28,644 |

| Caspase-3 | Biolight | PA00067HuA10 |

| BCL2 | Abclonal | A19693 |

Splenic lymphocyte viability assay

Fresh mouse spleens were collected and immersed in PBS, placed on ice, minced, and washed with PBS. The minced spleens were filtered through a 40 mm mesh filter to remove debris, and red blood cells were lysed by centrifugation at 300 g for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell suspension was adjusted to a final volume of 2 ml. Cell counting was performed using a hemocytometer. 1 million cells per well were seeded into a 96-well plate, and the culture medium in each well was replaced with 100 ul of fresh medium containing Cell Counting Kit-8 cell counting reagent. After incubation at 37 °C for 2 h, the absorbance was read using a thermoscientific microplate reader (Multiskan FC, USA) at 450 nm.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS software. The Shapiro-Wilk test was employed to assess the normality of the overall distribution at a significance level of 0.05. Statistical methods for each experiment, along with all P values and sample sizes (n), are indicated in the figure legends. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and P values < 0.01 and 0.05 were considered statistically significant. In all figures, *denotes P < 0.05, **denotes P < 0.01, and ***denotes P < 0.001, and “n” denotes no statistical significance.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University (LLSC2023227). The animal experiments were conducted according to ARRIVE guidelines. The care and treatment of mice were performed according to the guidelines for laboratory animal care, and the mice were euthanized upon completion of the experiments.

The handling of blood samples from volunteers has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University (LLSC2023141) and strictly adhered to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki, with informed consent obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians, and informed consent forms were signed.

Results

Melatonin inhibits proliferation, migration, and invasion of Huh7 cells, promoting apoptosis

To assess the effect of melatonin on Huh7 cells, we first evaluated the viability of Huh7 cells treated with various gradient concentrations of melatonin. Based on the dose-response curve and the determined IC50 value, concentrations of 0.5 mM and 1.0 mM were selected for subsequent experiments (Fig. 1A). Melatonin demonstrated a dose-dependent inhibition of proliferation, migration and invasion of Huh7 cells, as evidenced by colony formation, wound healing, Transwell migration, and invasion assays (Fig. 1B-I). Melatonin significantly upregulated Cleaved-Caspase-3 protein and mRNA expression levels of BAX and BAD, and downregulated BCL2 protein and mRNA levels in Huh7 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1J, K). Collectively, these results suggested that melatonin could suppress the proliferation, migration and invasion of Huh7 cells while promoting apoptosis.

Fig. 1.

Effect of melatonin on the Huh7 cell. (A) Huh7 cells were treated with various concentrations of melatonin (Mel: 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 mM) for 24 and 48 h, and cell viability was measured with CCK8 assay. Data are expressed as a percentage of the control. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. (B , C) Colony formation of huh7 cells in the presence of melatonin (Mel: 0, 0.5, 1 mM) for 14 days. (D , E) Transwell migration assay. After incubating with melatonin (Mel: 0, 0.5, 1 mM) for 24 h, observe Huh7 cells under a microscope and count the migration rate. (F , G) Wound healing experiment: After treatment with melatonin (Mel: 0, 0.5, 1 mM) for 24 and 48 h, observe the degree of scratch closure and count the relative mobility. (H , I) Transwell invasion assay: After incubating with melatonin (Mel: 0, 0.5, 1 mM) for 24 h, observe the invasion of Huh7 cells under a microscope and calculate the relative invasion rate. (J) Western blot and quantitative analysis of the expression of Cleaved-Caspase-3, and BCL2 proteins after incubation with melatonin (Mel: 0, 0.5, 1 mM) for 24 h. (K) RT-qPCR was performed to detect the expression levels of BAX, BAD and BCL2 mRNA after incubation with melatonin (Mel: 0, 0.5, 1 mM) for 24 h. The images presented in figures were representative results of three independent experiments.

Melatonin inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion, promotes apoptosis in HepG2 cells

Similarly, we first assessed the viability of HepG2 cells after treatment with different concentrations of melatonin, and then selected appropriate concentrations for follow-up experiments (Fig. 2A). Melatonin dose-dependently inhibited proliferation, migration, and invasion of HepG2 cells, as demonstrated by colony formation, wound healing, Transwell migration, and invasion assays (Fig. 2B-I). Western blot and quantitative analysis showed melatonin significantly upregulated Cleaved-Caspase-3 and downregulated BCL2 levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2J). RT-qPCR analyses showed melatonin significantly upregulated BAD and BAX levels, and downregulated BCL2 levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2K). Collectively, these results suggested that melatonin could suppress the proliferation, migration, and invasion of HepG2 cells while promoting apoptosis.

Fig. 2.

Effect of melatonin on the HepG2 cells. (A) HepG2 cells were treated with various concentrations of melatonin (Mel: 0, 0.5,1, 2, 3, 4, 6 mM) for 24 and 48 h, and cell viability was measured with a CCK8 assay. Data are expressed as a percentage of the control. (B, C) Colony formation of HepG2 cells in the presence of melatonin (Mel: 0, 0.5, 1 mM) for 14 days. (D, E) Transwell migration assay. After incubating with melatonin (Mel: 0, 0.5, 1 mM) for 24 h, observe HepG2 cells under a microscope and count the migration rate. (F, G) Wound healing experiment: After treatment with melatonin (Mel: 0, 0.5, 1 mM) for 24 and 48 h, observe the degree of scratch closure and count the relative mobility. (H, I) Transwell invasion assay: After incubating with melatonin (Mel: 0, 0.5, 1 mM) for 24 h, observe the invasion of HepG2 cells under a microscope and calculate the relative invasion rate. (J) Western blot and quantitative analysis of the expression of Cleaved-Caspase-3,and BCL2 proteins after incubation with melatonin (Mel: 0, 0.5, 1 mM) for 24 h. (K) RT-qPCR was performed to detect the expression levels of BAD, BAX, and BCL2 mRNA after incubation with melatonin (Mel: 0, 0.5, 1 mM) for 24 h. The images presented in figures were representative results of three independent experiments.

Melatonin suppresses proliferation and promotes apoptosis by downregulating PD-L1 expression in co-culture systems

The expression of PD-L1, through the PD-1/PD-L1 axis, is closely associated with immune escape as it renders immune cells incapable of recognizing and attacking cancer cells, thus facilitating tumor immune escape21. Western blot and RT-qPCR analyses showed that melatonin downregulated PD-L1 protein and mRNA expression levels in Huh7 and HepG2 cells (Fig. 3A-D). To determine whether melatonin regulates immune escape by affecting PD-L1 expression, thereby influencing the proliferation and apoptosis of cells, we pre-treated Huh7 and HepG2 cells with melatonin before co-culturing with T lymphocytes. We achieved higher purity of CD3+ cells through T cell sorting, increasing from 61.1% before sorting to 98.2% after sorting, thereby ensuring the purity of T cells for subsequent experiments (Fig. 3E). Flow cytometry indicated that the proliferation of Huh7 and HepG2 cells decreased after treatment with melatonin in the co-culture system. Specifically, the proliferation rate of Huh7 cells in the melatonin-treated group (26.4%) was lower than that in the control group (36.5%), and the proliferation rate of HepG2 cells in the melatonin-treated group (67.2%) was lower than that in the control group (73.2%) (Fig. 3F). Flow cytometry revealed that melatonin treatment led to a reduction in the G2 phase and a significant increase in the S phase both in Huh7 and HepG2 cells within the co-culture system, suggesting a deceleration in their proliferation rates (Fig. 3G). Additionally, the late apoptosis rate of Huh7 cells in the melatonin-treated group was significantly higher than that in the control group, indicating that melatonin primarily promoted late apoptosis of Huh7 cells. In the melatonin-treated group, both the early and late apoptosis rates of HepG2 cells were significantly higher than those in the control group, indicating that melatonin promoted both early and late apoptosis of HepG2 cells (Fig. 3H). Conversely, the ability of T lymphocytes to secrete immune cytokines in the coculture system was enhanced in melatonin group (Fig. 3I).

Fig. 3.

The effect of melatonin on PD-L1 expression and its impact on cancer cells in co-culture system with lymphocytes. (A-D) Detection of PD-L1 protein and mRNA expression levels in HepG2 and Huh7 cells after melatonin (Mel: 0, 0.5, 1 mM). (E) Flow cytometry analysis of T lymphocyte sorting. (F) Flow cytometry analysis and quantification of proliferation of Huh7 and HepG2 cells in the co-culture system. (G) Flow cytometry analysis and quantification of cell cycle distribution in co-culture system. (H) Flow cytometry analysis and quantification of apoptosis of Huh7 and HepG2 cells in co-culture system. (I) qPCR analysis of immune cytokines secreted by T lymphocytes. The images presented in figures were representative results of three independent experiments.

Melatonin’s anti-cancer efficacy in HCC mouse models

To examine the anti-cancer effects and action model of melatonin in vivo, We established mouse HCC models using both subcutaneous H22 cell tumor models and subcutaneous ascites-derived H22 cell tumor models (Fig. 4A, H). After the model was established successfully, all mice were given melatonin orally. In both models, with prolonged duration of continuous medication, the tumor size in the melatonin-treated group was significantly smaller than that in the control group (Fig. 4B, I). Regarding body weight, no significant differences were observed between the treatment and control groups in the nude mouse model. However, in the wild-type mouse model, the body weight of the melatonin-treated group was significantly lower than that of the control group starting from the fourth day of administration (Fig. 4B, I). After euthanasia, tumors and spleens were collected from the mice. It was found that the tumor sizes and weights in the melatonin-treated groups were significantly smaller than the control groups, while spleen appearance and weight showed no significant differences between the control groups (Fig. 4C-F, J-K). In both HCC models, hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, as well as Ki-67 immunostaining of tumor tissues, revealed that cell dysplasia and pathological mitosis in the melatonin treatment group were significantly reduced compared to the control group, suggesting that melatonin effectively inhibits cancer progression (Fig. 4G, L). In summary, the above results demonstrate the anticancer effect of melatonin in mouse models of HCC.

Fig. 4.

Melatonin’s anti-cancer efficacy in H22 hepatocellular carcinoma mouse model. Figures A-G depict the subcutaneous H22 cell tumor models, while Figures H-L represent the subcutaneous ascites-derived H22 cell tumor models. (A, H) Gross appearance of tumor-bearing mice in the subcutaneous tumor model (n = 8). (B, I) The changes of tumor volume and mouse body weight after drug administration in the two groups (n = 8). (C, E, J) The appearance of tumor size and spleen size in two groups of mice (n = 8). (D, F, K) Tumor and spleen weights for both mouse groups (n = 8). (G, L) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and Ki-67 mmunostaining of the tumor tissue’s pathological observations (n = 6).

The effect of melatonin on PD-L1 expression and other protein/mRNA levels in tumor tissue, and its impact on lymphocyte activity

Western blot analysis revealed that PD-L1 protein expression in tumor tissues from ascites tumor model in the melatonin-treated group was significantly lower than in the control group (Fig. 5A). This treatment also significantly enhanced lymphocyte activity and cytokine secretion ability in the spleen of mice with ascites tumors (Fig. 5B), further demonstrating that melatonin reduces cancer immune escape by decreasing PD-L1 expression. RT-qPCR analysis showed that in the melatonin group, the expression levels of BAX-mRNA and BAD-mRNA significantly increased, whereas those of BCL2 and BCL2-L1 mRNA significantly decreased (Fig. 5C). Similarly, BCL2 protein expression decreased, while Cleaved-Caspase-3 protein significantly increased compared to the control group (Fig. 5D). Immunohistochemistry showed decreased expression of BCL2 proteins in the cancer tissues of the melatonin-treated group, while the expression of Caspase-3 and E-cadherin proteins increased (Fig. 5E). CD8 immunostaining indicated that melatonin promotes T lymphocyte cell infiltration (Fig. 5E). In the melatonin group, western blot analysis revealed a reduction in HIF-1α protein levels, a key regulator of PD-L1, along with increases in phosphorylated forms of signaling proteins including JNK, p38, as well as phosphorylated JNK (P-JNK) and phosphorylated p38 (P-p38), demonstrating enhanced signaling pathways (Fig. 5F). In summary, melatonin reduces PD-L1 expression in HCC cells, enhances lymphocyte activity, and inhibits cancer immune escape, thereby exerting anticancer effects. The roles of melatonin in promoting apoptosis and reducing migration and invasion have been validated at both the protein and mRNA levels.

Fig. 5.

The effect of melatonin on PD-L1 expression and other protein/mRNA levels in tumor tissue, and its impact on lymphocyte activity. (A) PD-L1 expression and quantitative analysis in tumor tissues (n = 3). (B) CCK8 assay measured lymphocyte activity and RT-qPCR analyzed immune cytokines level (n = 8). (C) RT-qPCR analysis was performed to quantify the mRNA expression levels of BAX, BAD, BCL2, and BCL2-L1 in the tumor tissues of both groups of mice (n = 6). (D) Western blot and quantitative analysis was conducted to assess the protein expression levels of BCL2 and Cleaved-Caspase-3 in the tumor tissues of both groups of mice (n = 3). (E) Immunohistochemical detection of the expression levels of E-cad, caspase-3, BCL2 and CD8 in cancer tissue (n = 6). (F) Western blot detection and quantitative analysis of the expression levels of HIF-1α, JNK and P38 proteins and their phosphorylation status in the cancer tissues of both groups of mice (n = 3).

Discussion

Recent research has illustrated that malignancies such as HCC and breast cancer can affect melatonin secretion, which implies that melatonin might play important roles during the development of cancers22–24. Although some research indicates its anticancer activity15–17, its specific anticancer mechanism remains unclear. This study found that melatonin reduces PD-L1 expression, inhibits immune escape in HCC, and suppresses cancer cell proliferation, metastasis and invasion, while promoting apoptosis. Furthermore, we verified these results via in vivo experiments. We established HCC models in both nude and wild-type mice to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the effects of melatonin and to validate the consistency and reliability of the results across different models. Melatonin showed significant anticancer activity in both models, confirmed its antitumoral effects in vivo. As nude mice have innate immunodeficiencies25, and wild-type mice possess a complete immune system, the use of both types mice is more comprehensive for evaluating immune functions such as splenic T cell activity. Therefore, we believe that melatonin can exert its anti-tumor effects by reducing HCC PD-L1 expression to inhibit immune escape.

Previous studies have shown that PD-L1-induced immune escape has significant negative effects on the treatment of HCC26,27. Consequently, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors have been employed as adjunctive therapies for HCC. Nivolumab and pembrolizumab, as immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1, have demonstrated improvements in overall survival and progression-free survival in some HCC patients. However, these drugs may also cause immune-related adverse effects, such as skin reactions and liver dysfunction28–30. Some anti-PD-L1 antibodies, such as durvalumab and atezolizumab31,32, are widely used in treating various malignancies, but clinical trial data indicate that they do not significantly reduce high PD-L1 expression levels in HCC patients, particularly in advanced cases33,34. Therefore, while PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors hold promise in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), their potential to induce immune-related adverse effects and resistance remains a critical concern35,36. Precisely modulating PD-L1 expression could reduce the required dosage of these inhibitors and thereby minimize such side effects.

Given the current challenges of resistance and side effects associated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, several strategies are being explored to enhance therapeutic efficacy. One promising approach is the development of small molecule drugs that regulate PD-L1 expression.Melatonin is a small molecule drug, and our study found that it can reduce PD-L1 expression in HCC. Therefore, it has the potential to be used as an adjunctive therapy with inhibitors.

In HCC, does the alteration in PD-L1 expression directly affect the malignant phenotype of HCC cells, independently of its role in cancer immune escape? Numerous studies37–39have confirmed that changes in PD-L1 expression in cancer cells can directly influence their proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion. Cancer cells with high or overexpressed PD-L1 exhibit significantly enhanced abilities of proliferation, migration and invasion, whereas PD-L1 knockout or low-expression cancer cells show significantly reduced abilities in these aspects. Similar findings40,41 have been observed in HCC cells. Therefore, the intrinsic direct anti-cancer effect of melatonin in HCC observed in this study may also be related to the reduction of PD-L1 expression.

A pivotal upstream regulator of PD-L1, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α)42, is activated under hypoxic conditions, subsequently binding to the HIF-1β subunit to form the active HIF-1 complex. This complex interacts with the promoter region of the PD-L1 gene to enhance the gene’s transcription and expression43. In this study, the melatonin-treated group exhibited lower HIF-1α expression levels compared to the control group, suggesting that melatonin may suppress PD-L1 expression by inhibiting HIF-1α production. Supporting this conclusion, Ding XC et al.44identified a positive correlation between PD-L1 and HIF-1α in intracranial gliomas, further indicating that HIF-1α facilitates PD-L1 expression, consistent with our findings. Furthermore, significant increases were noted in the levels and phosphorylation of JNK and P38 proteins, components of the MAPK signaling pathway45. These findings suggest that JNK and P38 may act as upstream regulators of PD-L1, where their activation could suppress PD-L1 expression. Thus, melatonin’s potential to inhibit PD-L1 expression could be linked to its effects on both the HIF-1α and MAPK pathways, as shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

This study suggests that melatonin downregulates PD-L1 expression via HIF-1α, MAPK-JNK, or MAPK-P38 signaling pathways, thereby inhibiting immune escape in hepatocellular carcinoma.

PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors block existing PD-L1 on cancer cells, while strategies that reduce PD-L1 expression decrease its production by cancer cells at the source. The two approaches are aligned, both aiming to reduce PD-1 and PD-L1 interaction, thus enhancing immune cell antitumor functions. Reducing PD-L1 expression and using inhibitors are not merely overlapping strategies, they can be used in combination for HCC treatment. We hypothesized that reducing PD-L1 expression can potentially enhance the effects46 of inhibitors or address shortcomings in checkpoint inhibitor therapy, such as in patients who are insensitive to inhibitors. As a relatively safe hormone beneficial to human body, melatonin is used as an adjuvant therapy for HCC alone or in combination with PD-L1 inhibitors that have been used in clinical practice, all of which have unparalleled safety advantages over other drugs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that melatonin reduces PD-L1 expression in HCC, exerting dual anti-cancer effects by directly inhibiting cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion, while also suppressing immune escape to enhance anti-tumor immunity. The reduction in PD-L1 expression may occur through the inhibition of HIF-1α expression or the activation of the MAPK-JNK or MAPK-P38 pathways. This research offers new insights and approaches for HCC treatment, potentially applicable to other cancers. Future experiments, particularly clinical trials, are needed to assess the effectiveness and optimal dose of melatonin in treating HCC and its potential to inhibit tumor immune escape.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Doctoral Research Start-up Fund Project of Gannan Medical University (No. QD202221).

Author contributions

Conception and design, collecting data, project administration, writing original draft: Rui Guo. Conceptualization, resources, review and editing: Jun-ming Ye. Resources, investigation, methodology, collecting data: Pan-guo Rao, Bao-zhen Liao, Xin Luo, Wen-wen Yang, Xing-heng Lei. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This study received support from the Doctoral Research Start-up Fund Project of Gannan Medical University (No. QD202221).

Data availability

Data and materials are available from the corresponding author (haiou2018guo@163.com) on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study has obtained approval from the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University (LLSC2023141) and Animal Experiment Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University (LLSC2023227).

Consent for publication

All the listed authors agree to the publication of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Rui Guo, Email: haiou2018guo@163.com.

Jun-ming Ye, Email: yjm7798@126.com.

References

- 1.Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.71 (3), 209–249. 10.3322/caac.21660 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown, Z. J. et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: A review. JAMA Surg.158 (4), 410–420. 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.7989 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hao, L. et al. The current status and future of PD-L1 in liver cancer. Front. Immunol.10.3389/fimmu.2023.1323581 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watterson, A. & Coelho, M. A. Cancer immune evasion through KRAS and PD-L1 and potential therapeutic interventions. Cell. Commun. Signal.21 (1), 45. 10.1186/s12964-023-01063-x (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ju, X., Zhang, H., Zhou, Z. & Wang, Q. Regulation of PD-L1 expression in cancer and clinical implications in immunotherapy. Am. J. Cancer Res.10 (1), 1–11 (2020). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang, Y., Shi, H., Meng, H., Xu, J. & Editorial Targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 Cancer immune evasion axis: challenges and emerging strategies. Front. Pharmacol.11, 591188. 10.3389/fphar.2020.591188 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu, R. et al. LncTUG1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma immune evasion via upregulating PD-L1 expression. Sci Rep. ;13(1):16998.dio: (2023). 10.1038/s41598-023-42948-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Sperandio, R. C., Pestana, R. C., Miyamura, B. V. & Kaseb, A. O. Hepatocellular carcinoma immunotherapy. Annu. Rev. Med.73, 267–278. 10.1146/annurev-med-042220-021121 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li, Q., Han, J., Yang, Y. & Chen, Y. PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma immunotherapy. Front. Immunol.10.3389/fimmu.2022.1070961 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chao, Y. C. et al. Melatonin Downregulates PD-L1 Expression and Modulates Tumor Immunity in KRAS-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. ;22(11).dio: (2021). 10.3390/ijms22115649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Luo, X. et al. Melatonin inhibits EMT and PD-L1 expression through the ERK1/2/FOSL1 pathway and regulates anti-tumor immunity in HNSCC. Cancer Sci.113 (7), 2232–2245. 10.1111/cas.15338 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang, K. et al. Melatonin enhances anti-tumor immunity by targeting macrophages PD-L1 via exosomes derived from gastric cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol.10.1016/j.mce.2023.111917 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han, Y. et al. Circadian rhythm and melatonin in liver carcinogenesis: updates on current findings. Crit. Rev. Oncog.26 (3), 69–85. 10.1615/CritRevOncog.2021039881 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wada, K. et al. Dietary melatonin and liver cancer incidence in Japan: from the Takayama study. Cancer Sci.115 (5), 1688–1694. 10.1111/cas.16103 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cruz, E. M. S. et al. Melatonin modulates the Warburg effect and alters the morphology of hepatocellular carcinoma cell line resulting in reduced viability and migratory potential. Life Sci.10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121530 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elmahallawy, E. K., Mohamed, Y., Abdo, W. & Yanai, T. Melatonin and Mesenchymal Stem Cells as a Key for Functional Integrity for Liver Cancer Treatment. Int J Mol Sci. ;21(12).dio: (2020). 10.3390/ijms21124521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Fernández-Palanca, P. et al. Melatonin as an antitumor agent against liver cancer: an updated systematic review. Antioxid. (Basel). 10.3390/antiox10010103 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaji, K. et al. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor Canagliflozin attenuates liver cancer cell growth and angiogenic activity by inhibiting glucose uptake. Int. J. Cancer. 142 (8), 1712–1722. 10.1002/ijc.31193 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mossenta, M., Busato, D., Dal Bo, M. & Toffoli, G. Glucose Metabolism and Oxidative Stress in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Role and Possible Implications in Novel Therapeutic Strategies. Cancers (Basel). ;12(6).dio: (2020). 10.3390/cancers12061668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Zhou, Q. et al. GTPBP4 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression and metastasis via the PKM2 dependent glucose metabolism. Redox Biol.10.1016/j.redox.2022.102458 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang, Q. et al. The role of PD-1/PD-L1 and application of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in human cancers. Front. Immunol.10.3389/fimmu.2022.964442 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahabrach, H., El Mlili, N., Errami, M. & Cauli, O. Circadian rhythm and concentration of melatonin in breast Cancer patients. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord Drug Targets. 21 (10), 1869–1881. 10.2174/1871530320666201201110807 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mogavero, M. P., DelRosso, L. M., Fanfulla, F., Bruni, O. & Ferri, R. Sleep disorders and cancer: state of the Art and future perspectives. Sleep. Med. Rev.10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101409 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mortezaee, K. Human hepatocellular carcinoma: protection by melatonin. J. Cell. Physiol.233 (10), 6486–6508. 10.1002/jcp.26586 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen, J. et al. The development and improvement of immunodeficient mice and humanized immune system mouse models. Front. Immunol.10.3389/fimmu.2022.1007579 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen, C., Wang, Z., Ding, Y. & Qin, Y. Tumor microenvironment-mediated immune evasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Immunol.10.3389/fimmu.2023.1133308 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wen, Q., Han, T., Wang, Z. & Jiang, S. Role and mechanism of programmed death-ligand 1 in hypoxia-induced liver cancer immune escape. Oncol. Lett.19 (4), 2595–2601. 10.3892/ol.2020.11369 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peeraphatdit, T. B. et al. Hepatotoxicity from immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and management recommendation. Hepatology72 (1), 315–. 10.1002/hep.31227 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sonpavde, G. P., Grivas, P., Lin, Y., Hennessy, D. & Hunt, J. D. Immune-related adverse events with PD-1 versus PD-L1 inhibitors: a meta-analysis of 8730 patients from clinical trials. Future Oncol.17 (19), 2545–2558. 10.2217/fon-2020-1222 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramos-Casals, M. et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Dis Primers. ;6(1):38.dio: (2020). 10.1038/s41572-020-0160-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Zhu, A. X. et al. Molecular correlates of clinical response and resistance to Atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Med.28 (8), 1599–1611. 10.1038/s41591-022-01868-2 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel, T. H. et al. FDA approval summary: Tremelimumab in combination with durvalumab for the treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res.30 (2), 269–273 (2024). .dio:10.1158/1078 – 0432.Ccr-23-2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, S. et al. Liver metastases and the efficacy of the PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors in cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Oncoimmunology. ;9(1):1746113.dio: (2020). 10.1080/2162402x.2020.1746113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Zheng, J. et al. Benefits of combination therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors and predictive role of tumour mutation burden in hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Immunopharmacol.10.1016/j.intimp.2022.109244 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, Y. et al. A systematic review and Meta-Analysis of Immune-Related adverse events of Anti-PD-1 drugs in randomized controlled trials. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat.10.1177/1533033820967454 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan, S. & Gerber, D. E. Autoimmunity, checkpoint inhibitor therapy and immune-related adverse events: A review. Semin Cancer Biol.64, 93–101. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.06.012 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang, X., Wang, W. & Ji, T. Metabolic remodeling by the PD-L1 inhibitor BMS-202 significantly inhibits cell malignancy in human glioblastoma. Cell Death Dis. ;15(3):186.dio: (2024). 10.1038/s41419-024-06553-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Cui, P., Jing, P., Liu, X. & Xu, W. Prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression and its Tumor-Intrinsic functions in hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Manag Res.12, 5893–5902. 10.2147/cmar.S257299 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eichberger, J. et al. PD-L1 influences cell spreading, migration and invasion in head and neck Cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci.10.3390/ijms21218089 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeng, C. et al. HOXA-AS3 promotes proliferation and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via the miR-455-5p/PD-L1 Axis. J. Immunol. Res.10.1155/2021/9289719 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhong, F., Cheng, X., Sun, S. & Zhou, J. Transcriptional activation of PD-L1 by Sox2 contributes to the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol. Rep.37 (5), 3061–3067. 10.3892/or.2017.5523 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rashid, M. et al. Up-down regulation of HIF-1α in cancer progression. Gene10.1016/j.gene.2021.145796 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bailey, C. M. et al. Targeting HIF-1α abrogates PD-L1-mediated immune evasion in tumor microenvironment but promotes tolerance in normal tissues. J Clin Invest. ;132(9).dio: (2022). 10.1172/jci150846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Ding, X. C. et al. The relationship between expression of PD-L1 and HIF-1α in glioma cells under hypoxia. J Hematol Oncol. ;14(1):92.dio: (2021). 10.1186/s13045-021-01102-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Braicu, C. et al. A comprehensive review on MAPK: A promising therapeutic target in Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 10.3390/cancers11101618 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu, M. et al. Improvement of the anticancer efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade via combination therapy and PD-L1 regulation. J Hematol Oncol. ;15(1):24.dio: (2022). 10.1186/s13045-022-01242-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data and materials are available from the corresponding author (haiou2018guo@163.com) on reasonable request.