Abstract

Synthetic biology plays a pivotal role in improving crop traits and increasing bioproduction through the use of engineering principles that purposefully modify plants through “design, build, test, and learn” cycles, ultimately resulting in improved bioproduction based on an input genetic circuit (DNA, RNA, and proteins). Crop synthetic biology is a new tool that uses circular principles to redesign and create innovative biological components, devices, and systems to enhance yields, nutrient absorption, resilience, and nutritional quality. In the digital age, artificial intelligence (AI) has demonstrated great strengths in design and learning. The application of AI has become an irreversible trend, with particularly remarkable potential for use in crop breeding. However, there has not yet been a systematic review of AI-driven synthetic biology pathways for plant engineering. In this review, we explore the fundamental engineering principles used in crop synthetic biology and their applications for crop improvement. We discuss approaches to genetic circuit design, including gene editing, synthetic nucleic acid and protein technologies, multi-omics analysis, genomic selection, directed protein engineering, and AI. We then outline strategies for the development of crops with higher photosynthetic efficiency, reshaped plant architecture, modified metabolic pathways, and improved environmental adaptability and nutrient absorption; the establishment of trait networks; and the construction of crop factories. We propose the development of SMART (self-monitoring, adapted, and responsive technology) crops through AI-empowered synthetic biotechnology. Finally, we address challenges associated with the development of synthetic biology and offer potential solutions for crop improvement.

Key words: synthetic biology, crop improvement, engineering strategies, artificial intelligence

Synthetic biology is a rapidly advancing field that aims to improve crop traits and bioproduction through engineering principles, using genetic circuits for targeted crop modifications. This review explores the integration of artificial intelligence with synthetic biology for crop improvement, focusing on gene editing, multi-omics analysis, and protein engineering to enhance traits such as yield, resilience, and nutrient absorption. It proposes SMART crop development and highlights current challenges in plant engineering through synthetic biology.

Introduction

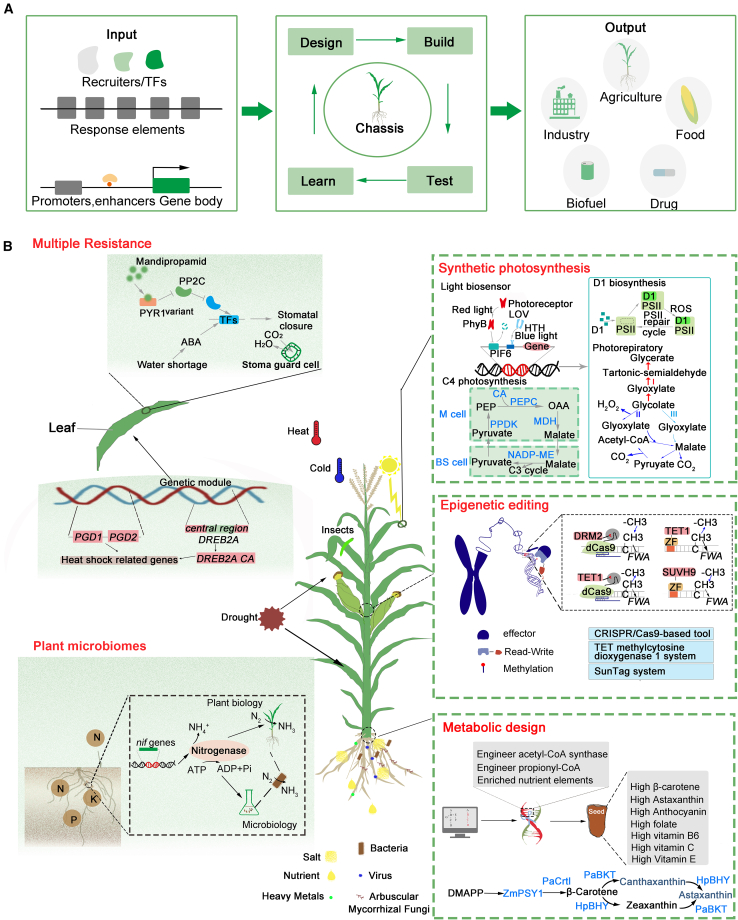

With a growing global population (projected to reach 9.7 billion people by 2050) and the challenges posed by climate change (rising 0.3°C per decade), global food production will need to increase by 70% to meet projected demands by 2050 (Guihur et al., 2022; Roell and Zurbriggen, 2020; Tian et al., 2021). However, conventional breeding strategies, which are time consuming and labor intensive, struggle to meet the demands of sustainable agricultural production (Fuglie, 2021). Numerous complex traits are regulated by combinations of genetic circuits rather than by a single gene. Synthetic biology (SynBio) combines modern engineering principles with biology, physics, chemistry, and computer science, enabling purposeful modifications of existing biological systems or the creation of entirely new input and output crop traits (Figure 1) (Bartley et al., 2017). The roots of SynBio can be traced back to the 1960s with the discovery of the lac operon in Escherichia coli (Jacob and Monod, 1961). With advances in molecular biology and sequencing technologies, SynBio has gained momentum and expanded its scope (Cameron et al., 2014). There are two main SynBio models: the evolutionary top-down approach and the rational bottom-up approach (Figure 1) (San León and Nogales, 2022). These modeling approaches have proved powerful in assisting crop engineering for improved multiple-stress tolerance, increased quality, and greater crop yield (Figure 1) (Gupta et al., 2021). The top-down approach involves the modification and reengineering of existing biological organisms or systems. This method starts with a fully functional organism and systematically simplifies or reprograms it to achieve desired functions. Unlike top-down approaches, the bottom-up approach requires a deep understanding of the performance of individual components. It has been used to construct a minimal cell from scratch (San León and Nogales, 2022). The minimal cell can perform transcription and translation, which allow organisms to regenerate energy and metabolism and respond to multiple stresses (Figure 1). The SynBio design process involves conceptualization, design, modeling, construction, and testing (Liu and Stewart, 2015), enabling the development of reliable, replicable, and predictable genetic systems. This systematic strategy has also advanced directed protein engineering, facilitating the introduction of novel traits for crop improvement.

Figure 1.

Plant defense against various biotic and abiotic stresses through top-down or bottom-up synthetic biology approaches.

The top-down approach involves enhancing an existing plant system by incorporating foreign elements or modules to create a microscopic assembly line that synthesizes a specific molecule of interest or elicits a significant response to incoming signals. By contrast, the bottom-up approach starts with individual parts and assembles them to develop artificial biological systems with unique properties. Regardless of the chosen approach, one of the primary objectives of plant synthetic biology is to redesign systems that effectively respond to biotic and abiotic stresses. Abiotic stresses, such as wounding, drought, cold, salinity, high light, oxidative stress, and nutrient deficiencies, have a profound impact on global agriculture. Studies indicate that these stresses can lead to average yield reductions of over 50% for most major crop plants. Similarly, biotic stresses caused by diverse living organisms, including fungi, bacteria, viruses, nematodes, insects, and mites, can result in yield losses exceeding 35%.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has made significant strides in computer science, leading to its application in crop breeding. AI incorporates various training algorithms and genetic models to achieve quick, efficient, and precise automatic breeding. Two widely used models in this context are artificial neural networks and support vector machines (Shadrin et al., 2020). Random forests and convolutional neural networks can construct models that take into account the intricate interplay of numerous environmental factors and genes, effectively distinguishing among various environmental data (Liu et al., 2020a; Yan and Wang, 2023). AI models have the capacity to interpret and analyze genetic data, pinpoint potential genes linked to specific traits, and offer precise trait predictions associated with a particular genotype (Wang et al., 2023). In addition, AI supports directed evolution for protein engineering by, for example, predicting and screening protein variants that align with engineering goals using machine learning algorithms (Cadet et al., 2022). Therefore, AI-driven SynBio can promote crop breeding by enabling precise identification of genetic elements and screening of desirable modified proteins, accelerating the development of crops with desired traits such as increased yield, disease resistance, and climate adaptability.

In this review, we propose that SynBio can be used to develop self-monitoring, adapted, and responsive technology (SMART) crops with high yield, efficiency, resistance, quality, and nutritive value, achieved through synthetic regulatory circuits. However, significant challenges remain in terms of developing technologies and methods for crop applications, such as efficient assembly methods for integrating individual genetic components into complex circuits or networks.

Approaches to complex genetic modules

Gene editing technology drives genome design

CRISPR-mediated gene editing is a powerful technique for genetic engineering that has proven useful in improving crop yield traits and tolerance. Base editors, including Cas9-NG, xCas9, nCas9, deactivated Cas9 (dCas9), and cytosine or adenosine deaminase domains, enable editing without inducing double-strand breaks (Zeng et al., 2020). In addition, RNA editors based on dCas13 can directly edit RNA molecules (Abudayyeh et al., 2019), and mitochondrial base editing can be achieved using DddA-derived cytosine base editors (Mok et al., 2020). Notably, a recent report demonstrated that a negative-strand RNA virus carrying an intact CRISPR-Cas9 system can induce DNA-free mutagenesis, offering a promising approach for efficient and cost-effective crop breeding (Figure 2B) (Ma et al., 2020). Directed protein engineering primarily involves replacing, inserting, or deleting nucleotides within a coding gene (Engqvist and Rabe, 2019). CRISPR-Cas9 also serves as an efficient technique for targeted mutagenesis to generate more useful engineered proteins. CRISPR-Cas12 offers significant advantages for crop improvement by enabling precise, targeted gene editing with high efficiency and minimal off-target effects, accelerating the development of crops with desirable traits (Zhang et al., 2024b; Zheng et al., 2024). Epigenome editing enhances crop traits by modifying histone/DNA/RNA modifications. Introduction of the human fat mass and obesity-related protein into rice and potatoes by epigenome editing was reported to lead to expanded root systems and improved drought resistance (Figure 2C) (Yu et al., 2021). However, improving the transformation efficiency of various crops to enable construction of large-scale gene-variation libraries remains a challenge. To obtain diverse genomes, a series of high-efficiency and precision editing techniques should be used to engineer genetic circuits.

Figure 2.

The development of technologies in synthetic biology.

(A) High-throughput sequencing (HTS) techniques for synthetic biology. Methods such as single-molecule real-time sequencing (SMRT-seq), nanopore sequencing (nanopore-seq), and bisulfite sequencing (BS-seq) enable the capture of individual bases. Assays like assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with HTS (ATAC-seq) and high-throughput chromatin conformation capture (Hi-C) can identify accessible regions of chromatin. Single-cell sequencing enables amplification and sequencing of the transcriptome or genome at the single-cell level. MeDIP/RIP, methylated DNA/RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation.

(B) Gene editing, such as CRISPR-Cas9, enables targeted modification of genes for precise genetic manipulation.

(C) The epigenome can modify the module through epigenetic modification and supply for modification sites for epigenetic editing. Me, methylation; Ub, ubiquitylation; Ac, acetylation; and Pi, phosphorylation.

(D) De novo synthesis enables the creation of new nucleotides and the construction of novel nucleic acid modules. TdT, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase; dNTP, deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate.

(E–G) Multi-omics analysis involves studying various molecular components, including the phenome (E), proteome (F), and metabolome (G). (E) The phenome allows for targeted screening of favorable synthetic components. (F) The proteome reveals the protein content of the synthetic module. (G) The metabolome can be readily modified to tailor specific metabolic pathways in plants.

(H) Genomic selection is used to improve the gene circuit by selecting yield-related genes.

(I) Artificial intelligence is used to achieve crop improvement through the intelligent design of gene circuits.

De novo genetic modules

A genetic module consists primarily of DNA, RNA, and protein, and the input elements are constructed through directed modification of these modules. Nucleic acids serve as the carriers of genetic information. De novo genetic modules include mainly nucleic acid synthesis and peptide synthesis (Figure 2D). A template-independent polymerase called terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase is conjugated to a single deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate molecule via a cleavable linker. This allows the coupled deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate to be added to the 3′ end of the primers during de novo DNA synthesis (Figure 2D) (Palluk et al., 2018). Polymerase cycle assembly and improved Gibson assembly methods using newly designed overlapping sequences have led to advances in the construction of complex DNA (Torella et al., 2014). In addition to the synthetic yeast chromosome SynIII, the artificial yeast chromosomes SynII, SynV, SynVII, and SynX have been generated through homologous recombination assembly of megachunks, with PCR tags used to distinguish the synthesized nucleotides from the wild type (Xie et al., 2017).

Peptide synthesis has been challenging owing to the limited solubility of peptides (Fuse et al., 2018). Microflow fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl-based peptide synthesis offers an automated solution that accurately controls reaction time and temperature and conserves raw materials on an industrial scale (Figure 2D) (Fuse et al., 2018). Cell-free DNA-templated protein synthesis has been achieved using cell lysates (Lee and Kim, 2018). Furthermore, protein engineering is widely used, and engineered E. coli can effectively produce pyridoxine (Liu et al., 2023). Protein fusion can also be accomplished by modifying the amino acids of a protein to incorporate unnatural amino acids through bio-orthogonal reactions (de Graaf et al., 2009). Machine learning could be used to engineer protein fusions that achieve an optimal fit for desired functions, leading to more effective protein coevolution libraries (Yang et al., 2023). This approach works by predicting the thermodynamic possibilities involved in the protein fusion process. Advances in de novo synthesis technology are crucial for SynBio, supporting the creation of new genetic modules in crops to enhance yield and improve quality.

Multi-omics technologies to optimize genetic circuits

Designing a gene circuit requires considering the processes of replication, transcription, and translation. Multi-omics approaches can better integrate these processes to optimize gene circuits. Genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, phenomics, pan-genomics, and metagenomics provide more detailed explanations of biological phenomena that drive advances in SynBio and systems biology through element-based, pathway-based, and mathematics-based approaches (Figure 2E–2G). The development of multiple sequencing technologies, such as single-molecule real-time sequencing, nanopore sequencing, and single-cell multi-omics, has enabled us to better understand the genome and thus optimize genetic circuits (Figure 2A). Epigenetic modifications play an important role in the design of epigenetic circuits. Bisulfite sequencing and methylated DNA/RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing can recognize the entire methylome on DNA or RNA to study their regulation of gene expression (Figure 2A) (Saplaoura et al., 2020). In addition, assay for transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing and high-throughput chromatin conformation capture technology, which can reveal chromatin structure, are important methods for optimizing epigenetic circuits (Figure 2A).

Genomic selection for input and output traits

Genomic selection (GS) is a powerful tool for genetic improvement in breeding programs. It involves evaluating the effects of critical genome-wide markers to compute genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) for untested populations (Krishnappa et al., 2021). This approach efficiently establishes marker–trait relationships through genetic models and prediction equations (Figure 2H), ranking and selecting candidate genes on the basis of their optimal properties (Voss-Fels et al., 2019). GEBVs are first used to evaluate the breeding value of reference/training populations from comprehensive phenotypic and genotypic data and then to estimate the breeding values of lines in an untested breeding population (Krishnappa et al., 2021). GEBVs typically integrate data from various environments (different years, locations, and treatments) and multiple generations of trait values for specific genotypes. By incorporating subjective information that approximates physiological processes, we can enhance the quality and precision of GEBVs, adding an extra layer of insight into crop physiology (Figure 2H). The integration of marker data with environmental information can produce a more precise assessment known as a physiological GEBV. Physiological GEBVs provide additional insights into the factors that influence crop yield formation before harvest (Trachsel et al., 2019). GEBV-based selection of superior crop traits has led to rapid genetic gains in drought, heat, and salt tolerance (Sales et al., 2017; Vivek et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2020b).

The goal of GS has evolved from early genomic predictions using GBLUP (genomic best linear unbiased prediction) and LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) methods to genomic design optimization. For instance, Yang et al. (2022b) developed an integrative multi-target breeding strategy based on a machine learning algorithm called target-oriented prioritization. This strategy integrates organismal and molecular traits through predictive analytics in breeding. Target-oriented prioritization improves multiple traits and accurately identifies improved candidates for new varieties, which will greatly influence breeding (Yang et al., 2022b). AI enhances GS by integrating multi-omics data, optimizing prediction accuracy, and accelerating the improvement of complex traits in crop breeding. Therefore, AI-empowered synthetic biotechnology can be used to create novel genetic circuits based on the information obtained from GS, enabling breeders to enhance new and complex traits simultaneously. The integration of genomic data with synthetic genetic engineering has the potential to revolutionize crop breeding programs by providing breeders with efficient and accurate tools for trait selection, thereby reducing time and costs and enhancing crop improvement efforts.

Directed protein engineering guided by artificial intelligence for synthetic biology

AI techniques encompass various methods such as machine learning, which trains algorithms on data to identify patterns and make decisions; natural language processing for understanding and generating human language; and computer vision for analyzing visual information, among others (Sarker, 2021). Before the advent of AI, it was challenging to predict the effects of individual amino acid substitutions on protein properties, and their impact often had to be measured directly, which was both time consuming and labor intensive. Machine learning algorithms can not only perform high-throughput screening and selection of engineered proteins or enzymes but also establish a platform for generating extensive data to support directed protein evolution (Cadet et al., 2022). Directed protein engineering typically involves three stages. The first stage (R1) includes protein modeling and the generation of protein variants, the second stage (R2) tests and provides feedback on these variants, and the third stage (R3) involves selecting specific engineered proteins on the basis of results from R1 and R2 (Li et al., 2019). AI plays a critical role across all three stages. Deep learning methods, such as ProteinMPNN, efficiently generate candidate amino acid sequences for protein modeling given a monomeric protein backbone. Using physics-based approaches, ProteinMPNN shows greater practical versatility and accuracy than Rosetta (Dauparas et al., 2022).

Understanding protein structure is also crucial to the design of novel proteins or enzymes. For instance, a homology model of the multi-functional P450 enzyme CYP8D2 was constructed on the basis of the crystal structure of CYP51 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Li et al., 2019). However, the quantity and diversity of natural protein structures are limited (Opuu and Simonson, 2023). Thus, expanding available protein structures is essential for the directed evolution of proteins. AlphaFold, a neural network-based model, can predict protein structures without requiring similar existing structures through the use of deep learning algorithms (Jumper et al., 2021). Plant protein engineering and directed evolution involve the heterologous expression of engineered proteins derived from plants or other exogenous sources (Engqvist and Rabe, 2019). It is therefore vital to consider the context dependence of protein stability for heterologous expression in plants. The three-dimensional structures of proteins affect their stability, and AlphaFold provides a reliable and accurate means of predicting these structures (Jumper et al., 2021).

Artificial intelligence for precise screening of genetic modules

The development of generative pre-trained transformers (GPTs) by OpenAI has significantly advanced intelligent crop breeding. Tools like BioGPT and ChatGPT, built on the GPT framework, are widely used (Luo et al., 2022; van Dis et al., 2023). The newly introduced biomedical GPT (BiomedGPT) model leverages self-supervision across diverse datasets to handle multi-modal inputs, including images, text, and bounding boxes, thereby pushing the boundaries of biomedicine (Zhang et al., 2023). CRISPR-GPT, a large language model (LLM) agent augmented with domain knowledge and external tools, automates and enhances the design of CRISPR-based gene-editing experiments (Huang. et al., 2024). Leveraging their robust reasoning capabilities, LLMs facilitate the selection of CRISPR systems, design of guide RNAs, recommendation of cellular delivery methods, drafting of protocols, and planning of validation experiments to confirm editing outcomes.

GPTs have the capability to extract text from global literature, providing access to a vast repository of biological and breeding data and facilitating the creation of an extensive biological knowledge atlas. This global research and biological knowledge atlas can bolster crop breeding efforts that lead to the accumulation of additional data and knowledge, which further enriches global research and the biological knowledge atlas. A model based on GPTs and big data can establish an iterative system to continuously improve biological breeding processes (Figure 2I). In the field of agriculture, the DeepG2P model leverages natural language processing and neural network architecture to handle multi-modal inputs such as genomics, environmental data, weather, soil conditions, and field management practices and their interactions, thereby enhancing crop production (Sharma et al., 2022). Furthermore, the CropGPT project aims to integrate advanced technologies like Double-Haploid (DH) technology, AI, genome editing, and various omics techniques to analyze and enrich basic germplasm, developing an optimal biological big data model (LLM/GPT) for precision breeding (Zhu et al., 2024). Moreover, the integration of AI with epigenetics and SynBio holds promise for the future of agriculture. Through the use of AI algorithms, researchers can analyze vast datasets to reveal intricate relationships among genes, epigenetic modifications, and phenotypic traits in crops. This deep understanding enables the design of targeted interventions through SynBio techniques to optimize crop performance. In short, AI can expedite the screening and testing of chassis and components, enhancing breeding efficiency. Through automation and large-scale computation, AI assists breeders in greatly simplifying and accelerating the efficient identification of genome combinations with the greatest potential for output traits like yield, disease tolerance, and adaptability.

Applications of synthetic biology in crops

Synthetic biology promotes high yield

Crop breeding technology has shifted its focus toward targeting the crop genome, progressing from crossbreeding to mutation breeding and ultimately to genome-editing breeding. Gene-editing-based SynBio enhances hybrid crop breeding by enabling precise genetic modifications, improving traits such as yield, disease resistance, and environmental adaptability (Svitashev et al., 2015, 2016). For example, the use of Cas9-guide RNA technology to reconstruct maize genetic circuits, such as maize male fertility genes (MS26 and MS45), has resulted in the creation of male sterility and opened up new possibilities for accelerating agricultural breeding practices (Supplemental Table 1) (Svitashev et al., 2015, 2016). The success of hybrid rice breeding relies on the diversification of male sterile cytoplasm (Cheng et al., 2007). A photosensitive genic male sterile rice line was developed by editing the Carbon Starved Anther (CSA) gene modules using CRISPR-Cas9 (Li et al., 2016). Precise targeting of the thermo-sensitive genic male sterile (TGMS) gene module led to the development of new male sterile lines, further advancing heterosis exploitation in rice (Zhou et al., 2016). Direct modification of the polyketide synthase (OsPKS2) gene in rice was also found to affect male fertility (Zou et al., 2018). Furthermore, a significant breakthrough in plant breeding programs was achieved by the use of CRISPR-Cas9 technology to edit the MATRILINEAL (OsMATL) gene and establish haploid inducer lines in rice (Yao et al., 2018). In summary, transgene-free genome editing technology drives genomic design and increases the precision of genetic circuits.

Plant height and branch number are crucial components of plant architecture and play a critical role in enhancing biomass yield (Salas Fernandez et al., 2009). Modern cultivars consist primarily of dwarf variants that exhibit reduced lodging, increased branching, and shorter fruit-ripening periods. The development of ideal plant architecture is crucial for optimizing light capture and nutrient use and improving yield and adaptability (Tian et al., 2024). Rapid advances in SynBio are helping to improve plant architecture and thus increase crop yields (Supplemental Table 1). For instance, engineering of the phytochrome gene (ZmPHYC2) resulted in decreased plant height, providing valuable insights for the development of new maize varieties (Supplemental Table 1) (Li et al., 2020a). In tomato, six genes (SELFPRUNING, OVATE, FASCIATED, FRUIT WEIGHT 2.2, MULTIFLORA, and LYCOPENE BETA CYCLASE) were simultaneously knocked out through a multiplex CRISPR-Cas9 approach to obtain a new variety with increased fruit size, number, and nutrition (Zsögön et al., 2018). Co-transformation of multiple metabolic genes into tomato increased C and N flow, thereby increasing fruit yield by 23% (Vallarino et al., 2020). Reconstruction of the factors that control branch number in rapeseed led to enhanced silique production and overall yield (Zheng et al., 2020). Directed protein evolution strategies are also used to improve the performance of genetically modified organisms and accelerate future intelligent breeding. For instance, a directed protein evolution approach was used to modify the function of a cucumber P450 enzyme through a combination of computational protein design, evolutionary techniques, and experimental data-driven optimization (Li et al., 2019). Using SynBio techniques, multiple microRNA elements can be constructed and inserted into a crop genome to reconstruct plant architecture. For instance, the reconstruction of osa-miR156 affects grain size, yield, quality, panicle branching, tillering, and plant height in rice (Chen et al., 2015), and remodeling of zma-miR164 can influence lateral root development in maize (Li et al., 2012). Similarly, rewriting of gma-miR167 can affect soybean root development (Tang and Chu, 2017). Collectively, these crop-improvement studies provide valuable insights into molecular mechanisms that can be artificially synthesized and simulated to introduce desired traits into crops (Figure 3A).

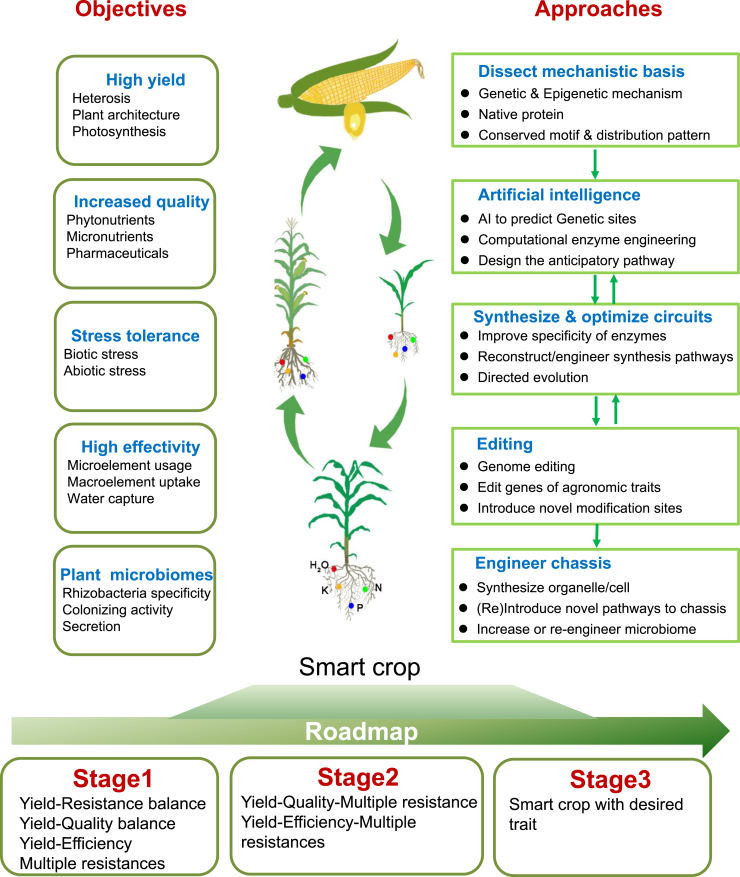

Figure 3.

Synthetic biology applications for enhancing crop improvement.

(A) A schematic depiction of a synthetic biology design. Synthetic biology has various applications in crops, primarily focusing on synthetic photosynthesis, epigenetic editing, metabolic engineering, multiple resistance, and plant microbiomes.

(B) Several noteworthy examples of modified crop photosynthesis include D1 biosynthesis, light biosensors, and C4 photosynthesis. Epigenetic editing involves the modification of specific sites in crop genomes. The main methods currently used are CRISPR-Cas9-based tools, the TET methylcytosine dioxygenase 1 system, and the SunTag system. Multiple resistance primarily encompasses biological and abiotic stress. Stress-response genes are reconstructed to enhance crop resilience; examples include modification of ABA response elements and the PGD gene to withstand heat stress. Altering the plant microbial environment can improve nutrient absorption in crops, and modification of nitrogen-fixing genes enhances nitrogen uptake.

Low crop yields can potentially be addressed through the application of SynBio techniques to redesign the plant photosynthetic system. Higher photosynthesis can be achieved by altering three key physiological processes: the induction rate of photosynthetic electron transport in the thylakoid membrane, the activation of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), and the conductance of CO2 diffusion (Liu et al., 2022). The construction of multiple photosynthetic elements has resulted in a significant increase in photosynthetic efficiency (Kromdijk et al., 2016). Concurrent transgenic expression of photosynthetic gene elements in Nicotiana led to an approximately 15% increase in dry matter productivity (Kromdijk et al., 2016). Implementing three different alternative pathways for photorespiration enables plants to more efficiently recover Rubisco-oxygenated compounds and enhances the yield of C3 crops (South et al., 2019). Synthetic biotechnology offers a more direct approach to protein transformation compared with traditional “trial and error” protein engineering methods. Rubisco, a critical enzyme for carbon fixation in the Calvin cycle, plays a paramount role in increasing crop yields. Through SynBio, Rubisco can be directionally transformed from archaeal origins and transferred to Nicotiana chloroplasts, addressing the kinetic limitations of Rubisco and increasing photosynthesis (Wilson et al., 2016). Rubisco catalysis is a rate-limiting step in plant photosynthesis and growth, and engineering Rubisco through directed evolution can enhance crop yields (Gionfriddo et al., 2024). However, differences in protein folding mechanisms between the chloroplasts of leaves and algae hinder the transfer of Rubisco variants into plants. Directed evolution enables the expression of exogenous proteins in plants, making it possible to improve Rubisco catalysis. Introduction of components of the carbon dioxide (CO2)-concentrating mechanism from cyanobacteria or algae into plant chloroplasts can enable Rubisco to operate under CO2 saturation (Fei et al., 2022). The core objective of directed evolution is to ensure that engineered biomolecules have the desired effect in the target environment. Mutagenesis of multiple Rbcs (Rubisco small subunit) genes in the nucleus and modification of the rbcL (Rubisco large subunit) gene in the plastome can affect the catalytic efficiency of Rubisco in plants. Although gene editing technologies have successfully silenced specific Rbcs copies in Arabidopsis (Khumsupan et al., 2020) and tobacco (Donovan et al., 2020), current plastid transformation and tissue regeneration systems still struggle to produce fertile, fully homoplasmic chloroplast-transformed progeny.

Structural analysis of cyanobacterial Rubisco activase, a homolog of plant Rubisco activase, has provided valuable insights for modifying plant Rubisco through synthetic biotechnology (Flecken et al., 2020). The emergence of microfluidics marks a significant milestone in the process of synthetic genetic circuit building and analysis (Gaut and Adamala, 2020). Miller et al. used microfluidics to develop purified thylakoids from spinach, achieving the creation of artificial chloroplasts, a novel type of solar-powered bioreactor crucial for construction of artificial photosynthetic cells (Miller et al., 2020). The integration of cyanobacterial CO2-concentrating mechanisms into plant chloroplasts improves plant CO2 fixation (Long et al., 2018). The major pathways of CO2 diffusion in the leaf are described by stomatal conductance (gs) and mesophyll conductance (gm), i.e., the ease with which CO2 diffuses from the intercellular spaces of the mesophyll cells to the chloroplasts (Campany et al., 2016); both are involved in plant photosynthetic induction. It is necessary to consider gm when using synthetic biotechnology to engineer photosynthesis, as increasing gm could increase the concentration of CO2 near Rubisco, resulting in higher rates of photosynthesis. The Arabidopsis gene Cotton Golgi-related 3 (CGR3), which influences gm, was recently introduced into tobacco, producing an increase of 28% in gm and an average increase of 8% in leaf photosynthetic CO2 uptake (Salesse-Smith et al., 2024). In recent years, a number of crucial genes that regulate gm have also been identified. For example, open stomata (ost1) affects stomata (Liu et al., 2022), and Retinoblastoma-related (OsRBR1) affects cell density (Zeng et al., 2022). In the future, these elements that regulate gm could be engineered to enhance photosynthesis.

A new photorespiratory bypass (GOC) in rice chloroplasts was established through a multi-gene assembly and transformation system (Figure 2B) (Kebeish et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2019). However, the grain yield of GOC rice was unstable. A synthetic photorespiratory shortcut (the GCGT bypass) that serves as a second branch of photorespiration solves the dilemma of unstable yield in rice (Wang et al., 2020). The GCGT bypass consists of three genetic modules encoding Oryza sativa glycolate oxidase and E. coli catalase, glyoxylate carboligase, and tartronic semialdehyde reductase. The synthesized GCGT bypass was introduced into rice to redirect 75% of the carbon from glycolate metabolism into the Calvin cycle, resulting in an increase in CO2 concentrations, which significantly increased plant photosynthesis, biomass production, and grain yield (Wang et al., 2020). An engineered rice that lacks chlorophyllide a oxygenase (CAO) and lazy plant1 (LAZY1) exhibited light green leaves and a robust tiller pattern (Miao et al., 2013). Engineering of the D1 protein can also enhance photosynthetic efficiency (Figure 3B) (Chen et al., 2020). SynBio technology can thus accelerate the transition from natural photosynthesis to artificial photosynthesis, playing a vital role in transforming plant photosynthesis and improving photorespiration (Supplemental Table 1).

Synthetic biology for metabolic pathway engineering

Modifying plant-specific synthetic metabolic pathways has the potential to improve crop yield and nutritive value. Crop synthetic metabolic engineering involves the manipulation of one or more critical genes or rate-limiting enzyme genes in plant metabolic pathways. Protein engineering and directed evolution are powerful technologies for the modification of plant metabolic pathways. These approaches have been used to enhance the activity of plant-derived enzymes and to achieve the heterologous expression of exogenous enzymes in plants. For example, the crotonyl-coenzyme A (CoA)/ethylmalonyl-CoA/ hydroxybutyryl-CoA cycle is a synthetic enzymatic network for continuous in vitro CO2 fixation that can convert CO2 into organic molecules at a rate of 5 nmol of CO2 per minute per milligram of protein (Supplemental Table 1) (Schwander et al., 2016). This groundbreaking research represents the first successful in vitro synthesis pathway for CO2 fixation, not only paving the way for artificial photosynthesis but also enabling the design of artificial or minimal self-sustaining cells. In another study, the use of computational design and directed evolution techniques to engineer acetyl-CoA synthase and propionyl-CoA reductase resulted in a higher carbon fixation rate and promoted plant growth and productivity (Trudeau et al., 2018). Furthermore, the de novo synthesis of starch from CO2 was achieved by designing and assembling an entirely novel anabolic pathway. The starch synthesis rate of this artificial pathway was 8.5 times higher than that of corn starch, marking a significant milestone in SynBio (Cai et al., 2021).

The use of synthetic metabolic engineering strategies for biofortification to increase the nutrient content of staple food crops is attracting increasing attention. As early as 2000, Ye et al. used recombinant technology to introduce the entire provitamin A (β-carotene) biosynthetic pathway into rice endosperm, significantly improving the nutritional quality of rice (Ye et al., 2000). Building upon this effort, “Golden Rice 2” was designed by incorporating the phytoene synthase (psy) gene (Figure 3B) (Paine et al., 2005). Currently, engineered metabolic pathways in crops are mainly designed by transferring critical gene elements for the directional design of new metabolic pathways. For example, transfer of the bacteria-derived CrtB and Crtl genes into wheat grains enhanced the carotenoid content of wheat (Wang et al., 2014), and specific overexpression of an Aspergillus niger phytase gene in maize seeds enabled the cultivation of transgenic phytase-containing corn for use as animal feed (Chen et al., 2013). In addition, a synthetic gene expression cassette consisting of sZmPSY1, sPaCrtl, sCrBKT, and sHpBHY was introduced into rice endosperm, leading to successful cultivation of the novel rice variety aSTARice/AR, capable of de novo astaxanthin synthesis (Zhu et al., 2018). The synthesis of maize β-carotene and astaxanthin can be achieved by combining different elements through nuclear transformation technology. A high-efficiency vector system was used to enhance anthocyanin synthesis in the rice endosperm, resulting in the development of the novel rice germplasm known as “Purple Endosperm Rice”(Zhu et al., 2017). Liu et al. used a multi-gene expression system that combined a bidirectional promoter with self-cleaving 2A peptides to reconstruct the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway in maize embryos, leading to the engineering of “Purple Embryo Maize” (Liu et al., 2018b). Engineered biosynthetic pathways for betalains were achieved by co-expressing the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP76AD1, DOPA 4,5-dioxygenase, and betanidin 5-O-glucosyltransferase (Chen et al., 2023). Furthermore, different gene clusters were fused to influence the spatiotemporal synthesis of anthocyanins, resulting in maize embryos and endosperm rich in anthocyanins (Liu et al., 2018a).

Metabolic engineering methods are currently being used to enhance the content of specific vitamins in crops, fruits, and vegetables. For example, integration of GTP cyclohydrolase I (GTPCHI) and ADC synthase (ADCS) into rice led to a 100-fold increase in folate levels (Storozhenko et al., 2007), and expression of GTPCHI and Arabidopsis ADCS (AtADCS) in tomato fruit produced folate levels 19 times higher than those of controls (de La Garza et al., 2007). Engineering of Zea mays phytoene synthase (psy1), Pantoea ananatis (formerly Erwinia uredovora) crtI (encoding carotene desaturase), rice dehydroascorbate reductase (dhar), and E. coli folE (encoding GTP cyclohydrolase) produced transgenic kernels with higher carotene, ascorbate, and folate contents (Naqvi et al., 2009). The construction of two GmGCHI genes, Gm8gGCHI and GmADCS, enhanced the folate metabolic flux in maize (Liang et al., 2019). The use of metabolic engineering strategies to overexpress duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX1) and PDX2 genes specifically in seeds increased their vitamin B6 content (Chen and Xiong, 2009). The same approach has been successfully used to increase vitamin C levels in maize, lettuce, tomato, and potato (Jiang et al., 2017) and vitamin E levels in maize and soybean through biofortification (Strobbe et al., 2018). Moreover, plant synthetic metabolic engineering can reshape novel metabolic pathways in higher plants to meet human needs, and directed evolution through protein engineering can reconstruct synthetic metabolic pathways by designing enzymes that are not naturally present in plants. Eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid are not naturally synthesized in higher plants, but both were successfully synthesized in Arabidopsis, Brassica juncea, Camelina sativa, and canola by introducing genes encoding desaturases and elongases or unsaturated fatty acid synthase subunits (Zhu et al., 2020). A phosphopantetheinyl transferase was introduced into cotton using SynBio biotechnology to remold genetic circuits, enabling the generation of multi-colored fibers (Zhu et al., 2020; Ge et al., 2023).

Synthetic biology increases tolerance to multiple stresses

Plants cannot move and must therefore endure multiple stresses simultaneously to cope with complex environmental changes. Biotic stresses, such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi, can cause yield losses ranging from 31% to 42%, and abiotic stresses, such as drought, salinity, and temperature fluctuations, can result in losses of 6%–20% (Shameer et al., 2019). The use of SynBio technology to develop stress-tolerant crop varieties will be essential for increasing crop yields and accelerating agricultural production. Plant endophytes can enhance plant immunity and alleviate the harmful effects caused by pathogens. For instance, the first genetically engineered insect-resistant cotton expresses a fusion gene of Pesticidal crystal (cry1AC) and cry1Ab, which produces insecticidal proteins derived from Bacillus thuringiensis and effectively inhibits cotton bollworm (Supplemental Table 1) (Li et al., 2020b). Burkholderia glumae can cause seedling and grain rot in rice. Cho et al. isolated the endophytic Burkholderia sp. KJ006 from rice and engineered it to interfere with Burkholderia quorum sensing and virulence (Cho et al., 2007). In the future, the targeting of specific genes could be used to engineer endophytes and improve crop tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses.

Glutathione transferases (GSTs) are involved in regulating numerous processes in organisms, including cell signaling, oxidative stress response, redox homeostasis, apoptosis, and secondary metabolite biosynthesis (Labrou et al., 2015). Plant GSTs play a crucial role in defending against oxidative damage under various stress conditions, enabling plants to respond effectively to both biotic and abiotic stresses. Engineering through directed evolution can enable the redesign of GSTs with novel binding properties and catalytic activities. GSTs have conserved modular structures and exhibit diverse functions and specificities, and they can be efficiently expressed with good structural stability. All these features make them suitable for the generation of GST mutant libraries (Perperopoulou et al., 2018).

The integration of machine learning algorithms can enhance the efficiency of high-throughput screening and evaluation of GST variants. Directed evolution of NADPH-dependent enzymes helps to regulate redox balance, and engineered oxygenase has been used to modulate redox states (Maxel et al., 2020). Transporters also play an important role in the management of osmotic stress, and both directed evolution and SynBio can be used to advance membrane transport engineering (Kell et al., 2015).

The cultivation of crops with enhanced resistance to abiotic stress is essential for improving agricultural productivity and minimizing environmental impacts. An engineered version of the ABA receptor PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE1 (PYR1) is highly sensitive to the agrochemical mandipropamid, enabling effective chemical control of plant ABA responses and drought tolerance (Figure 3B) (Park et al., 2015). Molecular dynamics simulations and quantitative deep mutational scanning experiments revealed how the modified PYR1 biosensor scaffold could better bind to mandipropamid (Leonard et al., 2024). The engineering of critical gene modules can also enhance crop salt tolerance. For example, high expression of the class II TPS gene osTPS8 or the methyltransferase gene LOC_Os3g61750 (osTRM13) can increase salt tolerance in rice (Wang et al., 2017; Vishal et al., 2019). Engineering of PLASTID GALACTOGLYCEROLIPID DEGRADATION1 (PGD1) and PGD2 can stabilize maize grain yield under heat stress (Figure 3B) (Ribeiro et al., 2020). Overexpression of the dehydration-responsive element gene DREB2A-CA improves crop heat-shock response (Sakuma et al., 2006), and enhancing the expression of C-repeat binding factor 4 (CBF4) and LeCBF1 confers freezing tolerance to Arabidopsis and tomato, respectively (Figure 3B) (Ding et al., 2019). Plants contain the salt overly sensitive pathway to mediate ion tolerance, and engineering this pathway can reduce or eliminate ion stress (Figure 3B) (Zhang et al., 2018).

Synthetic biology promotes high efficiency

Plants fulfill their own nutrient requirements by obtaining available nitrogen sources, ultimately synthesizing proteins and carbohydrates to produce high-quality agricultural products for human consumption. However, only a few prokaryotes, such as bacteria and cyanobacteria, have the ability to fix nitrogen from the air. Because of long-term species evolution and selective breeding, crops lack efficient nitrogen fixation systems to varying degrees. Enhancing nitrogen fixation in engineered grain crops could reduce reliance on nitrogen fertilizers in agriculture. Thus, the engineering of microorganisms associated with cereal crops is an effective approach to improving their nitrogen-absorption capacity (Geddes et al., 2015). The interaction between nitrogen-fixing bacteria and cereal crops involves multiple genes, and altering the expression of these genes can impact the crop’s nitrogen-fixing ability. Current research aims to improve the nitrogen-fixing ability of cereal crops through the use of SynBio to engineer microorganisms and nitrogen fixation (nif) genes (Figure 3B). SynBio strategies used to design and transfer nitrogenase activity primarily include multi-gene DNA synthesis and assembly, precision expression control, synthetic regulation, and simplified design. Temme et al. used this strategy to construct a “refactored” gene cluster and redefine the function of each genetic component (Supplemental Table 1) (Temme et al., 2012). Another approach for achieving effective nitrogen fixation in plants is to directly modify mitochondria or plastids to express functional nitrogenase. By transferring a modified nitrogenase genetic module into plant mitochondria, Allen et al. (2017) established a nitrogen fixation system that converts nitrogen into ammonia in the intracellular environment. In contrast to nitrogen, phosphorus exhibits limited mobility in the soil, and low phosphorus utilization restricts plant growth and metabolism. SynBio can be used to establish a symbiotic module between crops and fungi and to engineer phosphate transporters to promote plant phosphorus acquisition (Almario et al., 2017). Bottom-up construction of the plant microbiome also has the potential to significantly enhance nitrogen and phosphorus utilization in crops.

The application of synthetic epigenetics in crops

Epigenetics focuses primarily on the study of genetic traits that do not involve a change in DNA sequence (Loveless and Liu, 2019). Histone modifications such as histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation, H3 N(epsilon)-acetyl-lysine 9, and histone H3 lysine 36 trimethylation are associated with transcriptionally active genes in maize, whereas histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation and DNA methylation are predominantly found in transcriptionally inactive genes (Wang et al., 2009). Modifications of mRNA such as N6-methyladenosine (m6A) and 5-methylcytosine also affect aspects of plant growth and development, including leaf morphogenesis, fruit ripening, and root development (Liang et al., 2020). Epigenetic modifications can be transmitted to offspring and control quantitative variation among different varieties (Zhang et al., 2024a). Synthetic epigenetics involves designing and constructing artificial epigenetic modules or reconstructing existing epigenetic systems. A successful example of synthetic epigenetics is resetting the epigenetic landscape of a fibroblast genome to that of a pluripotent cell, thus generating induced pluripotent stem cells (Maherali et al., 2007). A control circuit based on epigenetic characteristics, also known as an “alternator circuit,” is heritable (Rodriguez-Escamilla et al., 2016). The rewriting of complex epigenetic regulatory networks can control and shape plant phenotypic plasticity, providing another avenue for crop improvement.

Epigenetic editing of specific loci enables selective and genetic alterations of gene expression. A CRISPR-Cas9-based tool was used to target methylation of the promoter regions of interleukin 6 cytokine family signal transducer (IL6ST) and basic leucine zipper transcription factor 2 (BACH2) by fusing dCas9 nuclease with the catalytic domain of DNA methyltransferase to reduce gene expression (Figure 3B) (Vojta et al., 2016). A recent study used a human ten–eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenase 1 (TET1) enzyme to induce epigenetic mutagenesis in plants, enabling demethylation without altering the DNA sequence, thus delaying the floral transition (Figure 3B) (Ji et al., 2018). The SunTag system, a CRISPR-based methylation targeting system for plants, effectively targets specific gene loci to induce developmental phenotypes (Papikian et al., 2019). A synthetic initiator module was created by combining a DNA adenine methyltransferase domain with an engineered zinc finger protein. This module can establish m6A markers at specific locations. A synthetic readout module consisting of an m6A reader domain and modular transcription effector domains was also designed. The regulatory system composed of the synthetic initiator module and the synthetic readout module uses engineered readers to recruit transcription effectors, thereby establishing a transcriptional regulatory network dependent on m6A modification. On this basis, Park et al. (2019) constructed a minimal read–write module capable of driving m6A spatial propagation. Synthetic epigenetics techniques also include the integration of critical methylation elements into gene editing systems, such as dCasRx associated with m6A methyltransferase-like 3 or demethylase AlkB homologs (ALKBH5), to achieve bidirectional regulation of the methylation level of specific m6A modifications in cells and the methylation levels of m6A modifications associated with the m6A-binding proteins YT521-B homolog YTH (DF1, DF2, and DF3) family using a dCasRx epitranscriptomic editor (Xia et al., 2021). Overall, top-down crop synthetic epigenetics is a future breeding strategy based on using the phenotypic diversity of epigenetics for breeding applications (Figure 1).

Deep learning can accurately predict modification sites, and epigenetic editing technology combined with deep learning models could enable synthetic epigenetics (Yang et al., 2022a). Deep learning models, such as those for predicting dynamic 5mC, 6mA, m6A, and histone modifications in plants, exhibit high prediction accuracy (Wang et al., 2021). The neural network model DENA (Deeplearning Explore Nanopore m6A) can predict m6A RNA modifications with 90% accuracy in Arabidopsis (Qin et al., 2022). In addition, a smart model for open chromatin region prediction (SMOC) in rice genomes predicted a large number of open chromatin regions with more than 80% prediction accuracy (Guo et al., 2022). These tools can improve the design and strategy of synthetic epigenetics in breeding.

Synthetic biology drives SMART crops

As extreme climates become more prevalent worldwide, CO2 levels continue to rise, and arable land continues to diminish, it is necessary to synthesize SMART crops, which can increase productivity to face global climate changes (Figure 4). SMART crops are capable of adjusting their phenotype in response to changing external conditions, leading to higher productivity. Strengthening the culm can improve lodging resistance, enabling plants to survive submergence and storms more effectively. A SMART crop is constructed by integrating multiple regulators designed by AI, which input genetic elements and output complex traits. Plants can alleviate stress responses caused by drought and high temperatures by manipulating the phenotypes of roots and flag leaves. Therefore, plants coordinate metabolic activities in the roots, stems, and leaves to dynamically respond to the external environment. Biosensors play a crucial role in recognizing signals expressed by organisms and converting them into a quantifiable signal that drives the plant to respond quickly to stressful situations. Engineered biosensors in plants could detect various plant infections (fungal, bacterial, and viral), phytohormones, and abiotic stresses and could monitor plant growth to optimize individual plant productivity and resource use. Synthesizing a “recognition–regulation” element composed of biosensors and specific regulatory elements enables the reprogramming of cell, tissue, and organ formation. To create desired plant morphology and functions, multiple pivotal genetic elements that control different traits are introduced into the plant framework, and sequence-specific nucleases are used to target and modify relevant genes.

Figure 4.

A schematic diagram illustrating the systematic engineering of improved crops for future breeding strategies.

By modifying various crop components, synthetic biology can create a self-monitoring, adapted, and responsive technology (SMART) crop with enhanced productivity in response to the changing environment. This SMART crop is designed with AI to achieve high yield, improved quality, stress tolerance, increased efficiency, and enhanced nutrient absorption. Synthetic approaches involve dissecting the mechanistic basis, employing artificial intelligence, synthesizing and optimizing circuits, performing editing techniques, and engineering the necessary chassis.

Synthetic biology accelerates construction of plant factories

Plants have long been recognized as the primary source of food and nutrients for humans, and the study of plant active constituents and their nutritional values has an extensive history. In recent decades, there has been a growing focus on plant factories for the production of biologically active molecules. Plant factories are a newly emerging industry aimed at transforming crop production in an unprecedented manner by leveraging industrial automation and informatics (Liu et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2022). Plant-based human vaccines are safer than traditional vaccines because they contain no live pathogens and can be stored without refrigeration at low cost (Takeyama et al., 2015). SynBio has made it possible to construct a transient expression system using plant virus vectors to yield large amounts of vaccines. Engineered tobacco plants, for instance, have been used to produce the anti-Ebola antibody (known as ZMapp) (Arntzen, 2015). Such engineered chassis have significant market value for the production of drugs and cosmetics (Reski et al., 2018). Furthermore, plant-derived expression systems can produce large quantities of insulin, and the significant production of biologically active proinsulin in seeds or leaves with long-term stability provides a low-cost technique for diabetes treatment (Baeshen et al., 2014). Teresa Capell’s team has successfully developed transgenic rice lines expressing three HIV infection inhibitors, thus enabling the cost-effective production of AIDS microbicides (Vamvaka et al., 2018). The establishment of plant factories requires the design of stable bioreactors to ensure consistency of protein production (Xu et al., 2011). Combining bioreactors with synthetic biotechnologies opens new avenues for the development of novel drugs and vaccines.

SynBio also shows tremendous promise for the production of biomaterials in plants. For example, plant-derived biomaterials have potential applications in cardiac tissue repair (Dai et al., 2023). Animal-derived biomaterials include collagen, fibrin, laminin, animal tissue-based extracellular matrix, and other biomaterials (Dai et al., 2023). However, these materials have adverse characteristics such as xenogenicity, poor scalability, poor reproducibility, and endotoxin or virus residues, making it difficult to use animal-derived biomaterials for downstream clinical transformation (Pomeroy et al., 2020). Plant-derived biomaterials have unique advantages over animal-derived biomaterials, such as inherent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and mechanical stability, which make them promising for use in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Plant-derived biomaterials include those derived from both marine and land plants. These materials have been successfully used in cardiac tissue engineering (Gershlak et al., 2017). Alginate from brown algae shows great biocompatibility, and its structure is similar to that of the extracellular matrix, enabling its use for drug and cell delivery in the form of hydrogel (Rastogi and Kandasubramanian, 2019). Carrageenan from seaweeds has biodegradability, biocompatibility, and immunomodulating ability and can be used as a scaffold for tissue engineering in the form of nanospheres (Geyik and Işıklan, 2021). Among biomaterials from land plants, cellulose from pineapple has superb mechanical strength and can be used as scaffolds and bioink (extrusion-based bioprinting) (Dai et al., 2023). Starch from crop seeds, stems, and roots can also be used as a functional additive or nanoparticle to control drug release or alter the properties of the structure (Nitta and Numata, 2013; Lemos et al., 2021). Pectin from the primary plant cell wall has the characteristics of easy chemical modification, hydrophilicity, and biocompatibility and can be used for three-dimensional printing of complex porous scaffolds with tunable properties (Xu et al., 2020). In conclusion, plant-derived biomaterials are widely used in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine because of their biocompatibility and biodegradability. However, with continuing research, plant-derived biomaterials also face challenges such as low cell-adhesive properties and batch-to-batch variability.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

Crop SynBio is poised to achieve more precise reconstruction and regulation of new and complex traits and is therefore anticipated to play an increasingly important role in the food, biofuel, therapeutics, and cosmetics industries. Synthetic biotechnology can be used to introduce genetic elements into crops, creating SMART crops with high yield (heterosis, plant architecture, and photosynthesis), rich nutrients (phytonutrients, micronutrients, and pharmaceuticals), stress resistance (biotic/abiotic stress), and high efficiency (microelement usage, microelement uptake, and water capture). The balance of yield, stress tolerance, high nutritional quality, and other characteristics are considered in this approach (Figure 4). There are five main steps to the SynBio-based breeding approach. First, the mechanistic basis must be dissected, including genetic and epigenetic mechanisms and protein functions. Then, AI is used to predict genetic sites and calculate enzyme activity to design the anticipated pathway. Next, circuits are synthesized or optimized according to the results of AI intelligent prediction, including improving the specificity of enzymes, reconstructing/engineering synthesis pathways, and directed evolution. If the circuit is not suitable for a chassis, AI intelligent prediction will be carried out again. Editing is the next step, including genome editing, editing genes for agronomic traits, and introducing novel modification sites, which require different choices based on different chassis organisms. The AI-driven CRISPR-GPT tool has the potential to assist significantly in this step (Huang et al., 2024). The last step is to engineer the chassis, which mainly involves synthesizing organelles/cells, (re)introducing novel pathways to the chassis, and increasing or reengineering the microbiome (Figure 4).

Although AI-driven SynBio holds great promise for crop improvement, many challenges lie ahead. First, crop traits are influenced by complex interactions between multiple genes and environmental factors. Many yield-related synthetic regulatory circuits and pathways remain unclear. Therefore, modeling these interactions accurately is a challenge for AI algorithms. Second, high-quality, comprehensive datasets are essential for training AI models. Datasets from different sources can be inconsistent in format, scale, and accuracy, making it difficult to integrate and analyze them effectively. Moreover, many AI models, especially deep learning algorithms, function as “black boxes,” providing predictions without clear explanations of the underlying mechanisms. This lack of transparency can hinder trust and adoption. Third, although CRISPR and other gene-editing tools have advanced significantly, achieving precise and efficient modifications in complex plant genomes remains challenging. Last, the regulatory landscape for genetically modified crops varies widely across countries. Navigating these regulations can be complex and time consuming, potentially delaying the deployment of AI-empowered SynBio solutions.

SynBio opens new frontiers in crop development in addition to enhancing traditional breeding methods. By constructing de novo genetic modules and optimizing gene circuits through multi-omics approaches, we can achieve unprecedented control over plant biology. This includes the ability to design crops with enhanced photosynthetic efficiency, improved nutrient content, and greater resilience to environmental stresses. AI models, such as artificial neural networks and support vector machines, can analyze complex genetic data to identify key genes associated with desirable traits. In addition, directed evolution is one of the most effective methods for protein engineering (Cadet et al., 2022). Synthetic biotechnology uses a “design, build, test, and learn” cycle to efficiently engineer genetic modules (Figure 3A), with the learning process integrated throughout directed evolution (Cadet et al., 2022). The learning step is crucial for generating a data-rich platform, which, combined with machine-learning-assisted screening, enables better design of optimal genetic modules. Although non-natural enzymes exhibit sufficient specificity and kinetics in vitro, they still require adaptive adjustments to enhance their activity in plants (Oliveira et al., 2023). Protein engineering can enhance various properties of proteins—including activity, selectivity, substrate range, stability, solubility, fluorescence, and photosensitivity—to improve the performance of engineered proteins in plants (Cadet et al., 2022). Natural protein evolution involves iterative mutation and selection to generate functional variants, often requiring prolonged adaptive changes. AI-driven protein engineering can significantly reduce this time by predicting and screening functional proteins from high-throughput libraries. Moreover, understanding the effects of single or multiple mutations on a functional parameter remains a major challenge in protein engineering, and AI-driven prediction can help address this problem more effectively. These insights can then guide the design of synthetic regulatory circuits and genetic modules, streamlining the breeding process and accelerating the development of superior crop varieties.

The complexity of plant metabolic pathways poses challenges for fully predicting the compatibility and genetic instability issues that may arise from the introduction of synthetic elements into plant hosts. To address these concerns, a combination of genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and phenomics is used to screen mutant libraries, predict the functionality of elements, and design targeted genetic modifications with AI. Given the slow progress and high costs associated with crop SynBio, commercializing SynBio remains challenging. Reducing the design cycle and expanding the diversity of synthetic elements can speed up the application of SynBio for crop enhancement. Public recognition and acceptance of synthetic biological products is also important, as this will ultimately impact the beneficial contributions of crop SynBio to agriculture and the economy.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Biological Breeding-National Science and Technology Major Project (2023ZD04076), National Natural Science Foundation of China (32261143757 and 32172091), Sustainable Development International Cooperation Program from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (2022YFAG1002), and Fundamental Research Funds for Central Non-Profit of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Y2024PT07 and CAAS-CSCB-202403).

Acknowledgments

No conflict of interest is declared.

Author contributions

D.Z. and F.X. conceived the study; D.Z., F.X., L.L., and L.P. wrote the manuscript; D.Z., F.X., and F.W. produced the figures; D.Z., F.X., L.L., and L.P. discussed and revised the paper.

Published: December 12, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information is available at Plant Communications Online.

Contributor Information

Liang Le, Email: leliang@caas.cn.

Li Pu, Email: puli@caas.cn.

Supplemental information

References

- Abudayyeh O.O., Gootenberg J.S., Franklin B., Koob J., Kellner M.J., Ladha A., Joung J., Kirchgatterer P., Cox D.B.T., Zhang F. A cytosine deaminase for programmable single-base RNA editing. Science. 2019;365:382–386. doi: 10.1126/science.aax7063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen R.S., Tilbrook K., Warden A.C., Campbell P.C., Rolland V., Singh S.P., Wood C.C. Expression of 16 Nitrogenase Proteins within the Plant Mitochondrial Matrix. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:287. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almario J., Jeena G., Wunder J., Langen G., Zuccaro A., Coupland G., Bucher M. Root-associated fungal microbiota of nonmycorrhizal Arabis alpina and its contribution to plant phosphorus nutrition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E9403–E9412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1710455114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arntzen C. Plant-made pharmaceuticals: from 'Edible Vaccines' to Ebola therapeutics. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015;13:1013–1016. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeshen N.A., Baeshen M.N., Sheikh A., Bora R.S., Ahmed M.M.M., Ramadan H.A.I., Saini K.S., Redwan E.M. Cell factories for insulin production. Microb. Cell Factories. 2014;13:141. doi: 10.1186/s12934-014-0141-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartley B.A., Kim K., Medley J.K., Sauro H.M. Synthetic Biology: Engineering Living Systems from Biophysical Principles. Biophys. J. 2017;112:1050–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dis E.A.M., Bollen J., Zuidema W., van Rooij R., Bockting C.L. ChatGPT: five priorities for research. Nature. 2023;614:224–226. doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-00288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet X.F., Gelly J.C., van Noord A., Cadet F., Acevedo-Rocha C.G. In: Directed Evolution: Methods and Protocols. Currin A., Swainston N., editors. Springer US; New York, NY: 2022. Learning Strategies in Protein Directed EvolutionDirected evolution (DE) pp. 225–275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai T., Sun H., Qiao J., Zhu L., Zhang F., Zhang J., Tang Z., Wei X., Yang J., Yuan Q., et al. Cell-free chemoenzymatic starch synthesis from carbon dioxide. Science. 2021;373:1523–1527. doi: 10.1126/science.abh4049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron D.E., Bashor C.J., Collins J.J. A brief history of synthetic biology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014;12:381–390. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campany C.E., Tjoelker M.G., von Caemmerer S., Duursma R.A. Coupled response of stomatal and mesophyll conductance to light enhances photosynthesis of shade leaves under sunflecks. Plant Cell Environ. 2016;39:2762–2773. doi: 10.1111/pce.12841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Xiong L. Enhancement of vitamin B(6) levels in seeds through metabolic engineering. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2009;7:673–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.H., Chen S.T., He N.Y., Wang Q.L., Zhao Y., Gao W., Guo F.Q. Nuclear-encoded synthesis of the D1 subunit of photosystem II increases photosynthetic efficiency and crop yield. Nat. Plants. 2020;6:570–580. doi: 10.1038/s41477-020-0629-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Yu Y., Zhang Z., Hu B., Liu X., James A.A., Tan A. Engineering a complex, multiple enzyme-mediated synthesis of natural plant pigments in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2023;120 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2306322120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Zhang C., Yao B., Xue G., Yang W., Zhou X., Zhang J., Sun C., Chen P., Fan Y. Corn seeds as bioreactors for the production of phytase in the feed industry. J. Biotechnol. 2013;165:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Gao X., Zhang J. Alteration of osa-miR156e expression affects rice plant architecture and strigolactones (SLs) pathway. Plant Cell Rep. 2015;34:767–781. doi: 10.1007/s00299-015-1740-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S.H., Zhuang J.Y., Fan Y.Y., Du J.H., Cao L.Y. Progress in research and development on hybrid rice: a super-domesticate in China. Ann. Bot. 2007;100:959–966. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H.S., Park S.Y., Ryu C.M., Kim J.F., Kim J.G., Park S.H. Interference of quorum sensing and virulence of the rice pathogen Burkholderia glumae by an engineered endophytic bacterium. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2007;60:14–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2007.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y., Qiao K., Li D., Isingizwe P., Liu H., Liu Y., Lim K., Woodfield T., Liu G., Hu J., et al. Plant-Derived Biomaterials and Their Potential in Cardiac Tissue Repair. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2023;12 doi: 10.1002/adhm.202202827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauparas J., Anishchenko I., Bennett N., Bai H., Ragotte R.J., Milles L.F., Wicky B.I.M., Courbet A., de Haas R.J., Bethel N., et al. Robust deep learning-based protein sequence design using ProteinMPNN. Science. 2022;378:49–56. doi: 10.1126/science.add2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf A.J., Kooijman M., Hennink W.E., Mastrobattista E. Nonnatural amino acids for site-specific protein conjugation. Bioconjug. Chem. 2009;20:1281–1295. doi: 10.1021/bc800294a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de La Garza R.I.D., Gregory J.F., Hanson A.D. Folate biofortification of tomato fruit. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4218–4222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700409104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Shi Y., Yang S. Advances and challenges in uncovering cold tolerance regulatory mechanisms in plants. New Phytol. 2019;222:1690–1704. doi: 10.1111/nph.15696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan S., Mao Y., Orr D.J., Carmo-Silva E., McCormick A.J. CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Mutagenesis of the Rubisco Small Subunit Family in Nicotiana tabacum. Front. Genome Ed. 2020;2 doi: 10.3389/fgeed.2020.605614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engqvist M.K.M., Rabe K.S. Applications of Protein Engineering and Directed Evolution in Plant Research. Plant Physiol. 2019;179:907–917. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.01534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei C., Wilson A.T., Mangan N.M., Wingreen N.S., Jonikas M.C. Modelling the pyrenoid-based CO2-concentrating mechanism provides insights into its operating principles and a roadmap for its engineering into crops. Nat. Plants. 2022;8:583–595. doi: 10.1038/s41477-022-01153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flecken M., Wang H., Popilka L., Hartl F.U., Bracher A., Hayer-Hartl M. Dual Functions of a Rubisco Activase in Metabolic Repair and Recruitment to Carboxysomes. Cell. 2020;183:457–473.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglie K. Climate change upsets agriculture. Nat. Clim. Change. 2021;11:294–295. [Google Scholar]

- Fuse S., Otake Y., Nakamura H. Peptide Synthesis Using Micro-flow Technology. Chem. Asian J. 2018;13:3818–3832. doi: 10.1002/asia.201801488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaut N.J., Adamala K.P. Toward artificial photosynthesis. Science. 2020;368:587–588. doi: 10.1126/science.abc1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X., Wang P., Wang Y., Wei X., Chen Y., Li F. Development of an eco-friendly pink cotton germplasm by engineering betalain biosynthesis pathway. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023;21:674–676. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes B.A., Ryu M.H., Mus F., Garcia Costas A., Peters J.W., Voigt C.A., Poole P. Use of plant colonizing bacteria as chassis for transfer of N₂-fixation to cereals. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015;32:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershlak J.R., Hernandez S., Fontana G., Perreault L.R., Hansen K.J., Larson S.A., Binder B.Y.K., Dolivo D.M., Yang T., Dominko T., et al. Crossing kingdoms: Using decellularized plants as perfusable tissue engineering scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2017;125:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyik G., Işıklan N. Design and fabrication of hybrid triple-responsive κ-carrageenan-based nanospheres for controlled drug delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;192:701–715. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gionfriddo M., Rhodes T., Whitney S.M. Perspectives on improving crop Rubisco by directed evolution. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024;155:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2023.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guihur A., Rebeaud M.E., Goloubinoff P. How do plants feel the heat and survive? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2022;47:824–838. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2022.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W., Liu H., Wang Y., Zhang P., Li D., Liu T., Zhang Q., Yang L., Pu L., Tian J., Gu X. SMOC: a smart model for open chromatin region prediction in rice genomes. J Genet Genomics. 2022;49:514–517. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2022.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta D., Sharma G., Saraswat P., Ranjan R. Synthetic Biology in Plants, a Boon for Coming Decades. Mol. Biotechnol. 2021;63:1138–1154. doi: 10.1007/s12033-021-00386-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRISPR-GPT: An LLM agent for automated design of gene-editing experiments. Huang K., Qu Y., Cousins H., et al., editors. arXiv. 2024;2404(18021):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob F., Monod J. On the Regulation of Gene Activity. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 1961;26:193–211. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1961.026.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji L., Jordan W.T., Shi X., Hu L., He C., Schmitz R.J. TET-mediated epimutagenesis of the Arabidopsis thaliana methylome. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:895. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03289-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Wang W., Lian T., Zhang C. Manipulation of Metabolic Pathways to Develop Vitamin-Enriched Crops for Human Health. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:937. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumper J., Evans R., Pritzel A., Green T., Figurnov M., Ronneberger O., Tunyasuvunakool K., Bates R., Žídek A., Potapenko A., et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebeish R., Niessen M., Thiruveedhi K., Bari R., Hirsch H.J., Rosenkranz R., Stäbler N., Schönfeld B., Kreuzaler F., Peterhänsel C. Chloroplastic photorespiratory bypass increases photosynthesis and biomass production in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:593–599. doi: 10.1038/nbt1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kell D.B., Swainston N., Pir P., Oliver S.G. Membrane transporter engineering in industrial biotechnology and whole cell biocatalysis. Trends Biotechnol. 2015;33:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khumsupan P., Kozlowska M.A., Orr D.J., Andreou A.I., Nakayama N., Patron N., Carmo-Silva E., McCormick A.J. Generating and characterizing single- and multigene mutants of the Rubisco small subunit family in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2020;71:5963–5975. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnappa G., Savadi S., Tyagi B.S., Singh S.K., Mamrutha H.M., Kumar S., Mishra C.N., Khan H., Gangadhara K., Uday G., et al. Integrated genomic selection for rapid improvement of crops. Genomics. 2021;113:1070–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2021.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kromdijk J., Głowacka K., Leonelli L., Gabilly S.T., Iwai M., Niyogi K.K., Long S.P. Improving photosynthesis and crop productivity by accelerating recovery from photoprotection. Science. 2016;354:857–861. doi: 10.1126/science.aai8878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrou N.E., Papageorgiou A.C., Pavli O., Flemetakis E. Plant GSTome: structure and functional role in xenome network and plant stress response. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015;32:186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.H., Kim D.M. Recent advances in development of cell-free protein synthesis systems for fast and efficient production of recombinant proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018;365 doi: 10.1093/femsle/fny174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos P.V.F., Marcelino H.R., Cardoso L.G., Souza C.O.d., Druzian J.I. Starch chemical modifications applied to drug delivery systems: From fundamentals to FDA-approved raw materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;184:218–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard A.C., Friedman A.J., Chayer R., Petersen B.M., Woojuh J., Xing Z., Cutler S.R., Kaar J.L., Shirts M.R., Whitehead T.A. Rationalizing Diverse Binding Mechanisms to the Same Protein Fold: Insights for Ligand Recognition and Biosensor Design. ACS Chem. Biol. 2024;19:1757–1772. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.4c00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]