Abstract

Adoptive transfer of antigen-specific regulatory T cells (Tregs) is a promising strategy to combat immunopathologies in transplantation and autoimmune diseases. However, their low frequency in peripheral blood poses challenges for both manufacturing and clinical application. Chimeric antigen receptors have been used to redirect the specificity of Tregs, using retroviral vectors. However, retroviral gene transfer is costly, time consuming, and raises safety issues. Here, we explored non-viral CRISPR-Cas12a gene editing to redirect Tregs, using human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2-specific constructs for proof-of-concept studies in transplantation models. Knock-in of an antigen-binding domain into the N terminus of CD3 epsilon (CD3ε) gene generates Tregs expressing a chimeric CD3ε-T cell receptor fusion construct (TRuC) protein that integrates into the endogenous TCR/CD3 complex. These CD3ε-TRuC Tregs exhibit potent antigen-dependent activation while maintaining responsiveness to TCR/CD3 stimulation. This enables preferential enrichment of TRuC-redirected Tregs over CD3ε knockout Tregs via repetitive CD3/CD28 stimulation in a good manufacturing practice-compatible expansion system. CD3ε-TRuC Tregs retained their phenotypic, epigenetic, and functional identity. In a humanized mouse model, HLA-A2-specific CD3ε-TRuC Tregs demonstrate superior protection of allogeneic HLA-A2+ skin grafts from rejection compared with polyclonal Tregs. This approach provides a pathway for developing clinical-grade CD3ε-TRuC-based Treg cell products for transplantation immunotherapy and other immunopathologies.

Keywords: Treg, CD3 epsilon, CRISPR-Cas12a, non-viral gene editing, CAR-Treg, HLA-A2, scFv, organ transplantation, tolerance, chimeric antigen receptor

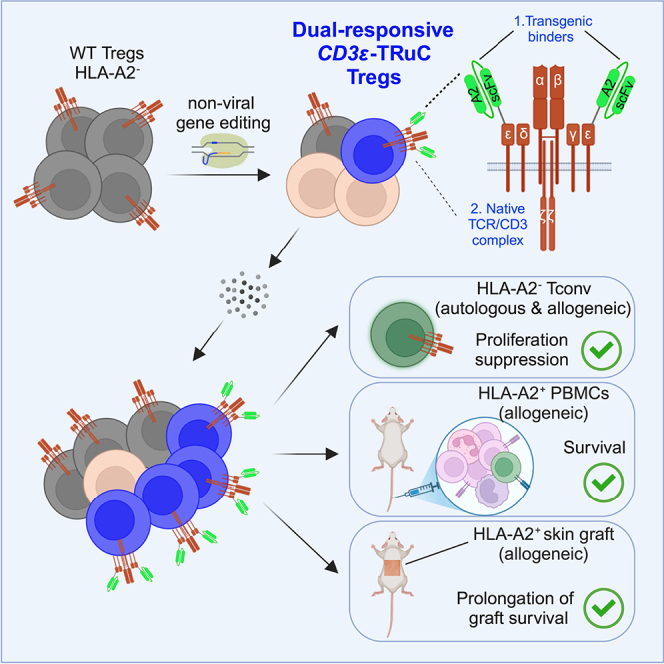

Graphical abstract

Wagner and colleagues demonstrate that non-viral CRISPR-Cas12a knock-in of antigen-binding domains into CD3ε generates dual-responsive CD3ε-TRuC Tregs that can signal via the TCR and the transgenic binder. HLA-A2-redirected CD3ε-TRuC Tregs preferentially enrich using GMP-compatible expansion protocols and protect allogeneic PBMCs and skin grafts from rejection in vivo.

Introduction

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are immunosuppressive lymphocytes that prevent autoimmune diseases, modulate overshooting immune responses, promote tissue regeneration and regulate bacterial homeostasis at mucosal surfaces.1 In circulation, 2%–5% of the peripheral blood’s CD4+ T cells represent Tregs characterized by a canonical phenotype, such as the high expression of the master transcription factor FoxP3 and the interleukin (IL)-2 receptor alpha chain, CD25, as well as low expression of the IL-7 receptor alpha chain, CD127.2,3,4 Clinical data from patients with solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation associate higher frequency of activated Tregs after transplantation with better graft survival and lower incidence of graft-versus-host-disease, respectively.5,6,7,8 Congenital Treg dysfunction is associated with severe autoimmune disease. Consequently, adoptive Treg transfer has emerged as a modality for tailored immunosuppression with many potential applications.9

Adoptive transfer of ex vivo expanded polyclonal Tregs has been clinically tested as a potential treatment to minimize immunosuppression in solid organ transplants,10 resolve chronic graft-versus-host disease,11 and ameliorate autoimmune diseases, such as type 1 diabetes mellitus12 or inflammatory bowel diseases.13 Transfer of antigen-specific Tregs has demonstrated higher potency in most preclinical models of above-mentioned diseases.14 Challenges in manufacturing arise from the low abundancy of antigen-specific Tregs in the peripheral blood, which has slowed adoption of antigen-specific Tregs in clinical practice.15

Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) are tools to guide Tregs toward target antigens, such as auto-, allo-, or tissue-specific antigens. CARs are synthetic fusion genes, which typically combine the antigen-binding domain of a monoclonal antibody (commonly single-chain variable fragment [scFv]) with intracellular signaling domains that trigger T cell activation, usually via CD3 zeta. Conventional second-generation CARs incorporate additional co-stimulatory signaling domains to enhance T cell proliferation and survival. In Tregs, CD28 has been favored as a costimulatory domain in second-generation CARs.16

The first CAR-Treg candidate that entered clinical trial uses an human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2-specific CAR construct17 and is tested in allogeneic kidney transplantation18 (NCT04817774). The scarcity of donor organs, difficulty of HLA matching, and potent immunosuppressive drug cocktails established minimally HLA-matched allogeneic solid organ transplantation as the gold standard, particular in living donor recipients. Due to the high frequency of the HLA-A2 allele in the Caucasian population, approximately one-quarter of HLA-A2-negative renal transplant recipients were offered an HLA-A2-positive renal transplant in Europe and the United States.18 HLA-A2 represents a promising candidate for CAR targeting in transplant medicine.19,20 Results on safety and efficacy of HLA-A2-directed Tregs in clinical trials are pivotal to inform future developments for autoimmune diseases.

Manufacturing of CAR-redirected Tregs is dominated by retroviral gene transfer (e.g., replication-deficient lentivirus).17,19,20,21 The production of viruses for gene transfer is costly and time consuming at clinical stages. Non-viral approaches with transposase technology, such as PiggyBac or Sleeping Beauty, represent more affordable alternatives for gene transfer. To our knowledge, they have not been adopted in the Treg space. Furthermore, the two recent cases of CAR-derived lymphoma in a trial using hyperactive PiggyBac-modified T cells22,23 attest a potential risk of mutagenesis when using transposase technology, which may be attributed to random insertion of multiple transgene copies, genetic dysregulation by exogenous promoters, or genetic scarring by transgene hopping of transposable elements.24

CRISPR-Cas gene editing may represent a non-viral alternative for site-specific gene transfer in Tregs,25,26 which reduces the risk for insertional mutagenesis. By utilizing genomic promoters, it may further alleviate the need for exogenous promoters for efficient transgene expression. Virus-free knock-in through electroporation of dsDNA and CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes was shown to allow efficient reprogramming of T cells and Tregs.25,26,27,28 Studies using this approach usually integrate the transgenic antigen receptor into the TCR alpha constant gene (TRAC), because this leads to TCR replacement with a low risk of alloreactivity and physiological regulation of the transgene, which has been associated with improved CAR-redirected effector T cell fitness in leukemia models.29,30 However, optimal ex vivo expansion of Treg requires distinct stimuli and metabolic conditions from conventional CAR-T cells used for cancer treatment, limiting a 1:1 knowledge transfer to optimal CAR-Treg design.31

In this study, we evaluated virus-free knock-in of CARs to redirect Tregs and used HLA-A2-specific CAR for functional proof-of-concept studies. As TCR/CD3-negative TRAC-replaced CAR Tregs failed to expand efficiently, we devised a promoter-less gene editing strategy to produce redirected Tregs in a virus-free and good manufacturing practice (GMP)-compatible process. CRISPR-Cas12a-mediated insertion of a fully human HLA-A2-specific scFv cDNA into the CD3 epsilon (CD3ε) gene facilitated the generation of T cell receptor fusion construct (TRuC)-expressing human Tregs. Functional characterization in vitro and in vivo highlights the potent immunosuppressive properties of CD3ε-TRuC Tregs.

Results

Identification of a CD3ε gene editing strategy to create TRuC+ T cells after integration of scFv cDNA

To generate an HLA-A2-specific CAR construct for redirecting Tregs, we replaced the antigen-binding domain of second-generation CAR28 with an HLA-A2-specific scFv that was originally derived from an allo-sensitized 57-year-old female patient32 (Figures S1A and S1B). After peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) isolation from peripheral blood of HLA-A2-negative healthy donors, CD4+CD25highCD127lowCCR7+ Tregs were sorted with more than 90% of purity (Figure S2). Of note, sorting total CCR7+ Tregs including CCR7+ CD45RA+ naive Tregs and CCR7+ CD45RA− central memory Tregs is based on two rationales: first, CCR7− Tregs showed phenotypical and functional instability compared with CCR7+ Tregs33; second, total CCR7+ Tregs allowed us to start with higher cell numbers than naive CCR7+ CD45RA+ Tregs. Then, Tregs were activated using anti-CD3/28 stimulation beads and expanded in the presence of IL-2 and the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor rapamycin.34 After 7–9 days expansion, the proliferating Tregs were harvested and electroporated with linear double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) for CAR integration via homology-dependent DNA repair (HDR-template) and a pre-complexed RNP containing TRAC-specific guide RNA (gRNA),28 recombinant Streptococcus pyogenes (S.p.) Cas9 protein and poly-L-glutamic acid (PGA).35 The resulting TRAC-CAR+ Tregs were predominantly CD3 negative (Figure S1C) and retained canonical markers of Tregs identity, e.g., high expression of FOXP3 and CD25 (Figure S1D). However, TRAC-CAR Tregs could not be efficiently expanded after gene editing either via HLA-A2 overexpressing K562 cells or dimeric human HLA-A2:Ig fusion protein stimulation (Figure S1E). Re-stimulation on plate-bound recombinant HLA-A2:Ig-fusion protein every 2–3 days with and without anti-CD28 monoclonal antibody (mAb) yielded expansion folds of 1.60 and 2.57 respectively, after gene editing. The addition of irradiated HLA-A2-overexpressing K562 cells improved expansion from 0.5-fold (no stimulation) up to 5-fold. In contrast, polyclonally expanded Tregs could expand up to 500-fold within a 19-day expansion period (Figure S1E).

The suboptimal expansion of TRAC-CAR Tregs is prohibitive to create a stable protocol at clinical scale. Therefore, we devised a gene editing strategy to redirect Tregs with the chosen HLA-A2-specific scFv, but compatible with our GMP expansion process using repetitive anti-CD3/28 bead stimulation.10 To this end, we hypothesized that targeted fusion of the HLA-A2 scFv into the extracellular N-terminus of the CD3ε subunit should generate HLA-A2-specific Tregs that express a TRuC.36 The CD3ε-TRuC becomes a functional component of the endogenous TCR/CD3 complex, allowing dual responsiveness of the edited Treg via the scFv and the endogenous TCR.36 Tregs with a successful TRuC knock-in should therefore retain a TRuC-enhanced TCR/CD3 complex on their cell surface, which can be engaged via anti-CD3/28 stimulation beads as well as the HLA-A2 antigen.

HDR with programmable nucleases depends on efficient installation of DNA double-strand breaks and the subsequent occurrence of insertion and deletions. Thus, we first screened 5 potential crRNA candidates (Table S1) for the CRISPR-Cas12a nuclease derived from Acidaminococcus species (AsCas12a) for their ability to disrupt CD3ε in exon 3 or exon 6 in conventional T cells (Tconvs) (Figure 1A). Synthetic crRNAs and recombinant AsCas12a Ultra37 were co-electroporated in polyclonally activated Tconvs, and CD3ε expression was measured by flow cytometry as a readout. Four days after nucleofection, Tconvs treated with AsCas12a crRNA #1 and crRNA #5 displayed highest knockout (KO) efficiencies compared with other crRNAs in their respective target sites (Figures 1B–1D).

Figure 1.

Identification of a CD3ε gene editing strategy to create TRuC+ T cells after integration of scFv cDNA

(A) Five crRNAs targeting exon 3 and exon 6 of CD3ε locus were selected. (B) Representative dot plot of mock electroporated T cells. (C) Representative dot plots of T cells upon RNP-mediated gene KO. (D) KO efficiency summary using the five crRNAs. n = 4 for KO condition, n = 2 for mock condition. HLA-A2 scFv incorporated CD3ε-TRuC construct design and integration into (E) crRNA #1 cut site within intron 3 and into (F) crRNA #5 cut site within exon 6. (G) Representative dot plots of HLA-A2 CD3ε-TRuC detection by using crRNA #1 (blue) and crRNA #5 (orange) with mock T cells as staining control (gray). HDR Enhancer V2 was incorporated in the electroporation procedure. n = 2. (H) Histogram overlay of Myc+CD3ε-TRuC cells using either crRNA #1 or crRNA #5 for KO. (I) HDR efficacy comparison for HDR-templates integrated in crRNA #1 and crRNA #5 cut site, respectively. (J) MFI comparison of CD3ε-TRuC+ cells by integrating TRuC construct into CD3Ε exon 3 and exon 6, respectively. (K) Total cytokine profiles of HLA-A2 CD3ε-TRuC CD4+ Tconv (top left) and CD8+ Tconv (top right) as well as HER2 CD3ε-TRuC CD4+ Tconv (bottom left) and CD8+ Tconv (bottom right) upon either plate-bound 8 μg/mL anti-CD3 antibody, or antigen-positive tumor cell, or antigen-negative tumor cell stimulation. Mock Tconvs that were stimulated with plate-bound 8 μg/mL anti-CD3 antibody were used as control. Values were calculated based on Boolean gate function in FlowJo v.10 (BD). Bar graphs show mean and error bars indicate standard deviation.

For the two most efficient crRNAs (#1 and #5, targeting exon 3 and exon 6, respectively), we designed corresponding HDR templates with 400-bp homology arms flanking the HLA-A2-scFv cDNA and the G4S linker, to facilitate the attachment of the antigen-binding domain onto the CD3ε protein (Figures 1E and 1F). For detection purposes, we added a myc-tag in front of scFv cDNA. After transfection of RNP and the respective dsDNA HDR-template into Tconvs via electroporation, we could detect large fractions of myc+ TRuC cells (Figure 1G). TRuC knock-in rates and expression level were significantly higher when targeting exon 3 (Figures 1H–1J). To further examine cutting efficiency by Cas12a RNP with crRNA #1, genomic DNA was extracted from 2-week expanded CD3ε-KO or mock-electroporated Tconv, a T7E1 assay and Sanger sequencing confirmed more than 80% indel frequency in the CD3ε-KO Tconvs in all three biological replicates, suggesting effective cutting of the CRISPR-AsCas12a RNP with crRNA #1 (Figure S3). Thus, we selected crRNA #1 and the respective HDR template targeting CD3ε exon 3 for all future experiments.

To confirm that this CD3ε-TRuC gene editing strategy enables T cells to signal via CD3ε-TRuC antigen-binding domain and the TCR/CD3 complex, we generated HLA-A2-specific and HER2-specific CD3ε-TRuC Tconvs and evaluated their abilities to produce cytokines including interferon (IFN)-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and IL-2 upon co-culture with antigen-expressing tumor cells or anti-CD3 stimulation (Figures 1K and S4). Both HLA-A2- and HER2-specific CD3ε-TRuC Tconvs showed strictly antigen-dependent cytokine production after co-cultures with HLA-A2+/− or HER2+/− tumor cells. These two CD3ε-TRuC Tconvs showed similar levels of cytokine production as CD3+ mock Tconvs upon pan-T cell stimulation with plate-bound anti-human CD3 antibody. Further, the HLA-A2-specific CD3ε-TRuC Tconv secreted similar amounts of cytokines as HER2-redirected CD3ε-TRuC Tconv (Figure 1K). Collectively, the CD3ε-TRuC strategy allowed dual stimulation through both antigen-scFv interaction and the TCR/CD3 complex in Tconvs.

Off-target analysis with CAST-Seq confirms high specificity of the crRNA-AsCas12a gene editing

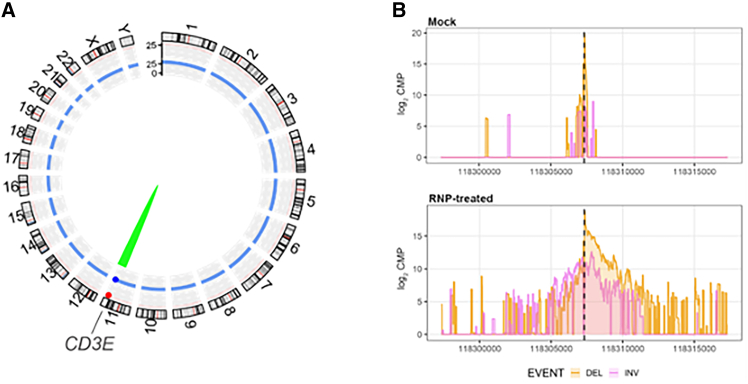

The risk of off-target effects and other forms of genotoxicity is a concern when translating CRISPR-Cas to clinical protocols.38 To confirm the high specificity of our preferred CRISPR-AsCas12a gene editing strategy, we examined the off-target profile of the selected AsCas12a-crRNA #1 using CAST-Seq technology,39 which detects potential off-target sites by identification of translocations between the on-target and the putative off-target sites. CAST-Seq revealed no off-target-mediated translocations (OMTs), suggesting high specificity (Figure 2A; Table S2). At crRNA #1 cleavage site, CAST-Seq revealed the expected pattern of larger insertions and deletions specifically in RNP-treated CD3ε-KO Tconv (Figure 2B). Consequently, our preclinical analysis supports the further development of AsCas12a-crRNA #1 combination for clinical cell products of CD3ε-TRuC T cells.

Figure 2.

Off-target analysis with CAST-Seq confirms high specificity of the crRNA-Cas12a targeting exon 3 of CD3Ε

(A) Structural variations. Genomic aberrations at the on-target site are displayed by the green arc. Red and blue dots represent significant scores for gRNA alignment and sequence homology, respectively. No off-target- (red arc) or homology-mediated (blue arc) translocations were detected. (B) Chromosomal rearrangements at the on-target site. Shown are CAST-Seq coverage plots of reads aligned to a ±10 kb region flanking the CD3ε target site. Deletions (DEL) are shown in orange, inversions (INV) in purple. The x axis represents the chromosomal coordinates, the y axis the log2 read count per million (CPM), and the dotted line the cleavage site. Sequencing direction is from left to right.

Continuous CD3/CD28 stimulation leads to preferential expansion of CD3ε-TRuC Tregs over TCR-negative Tregs

Using our non-viral gene editing protocol for Tregs, we generated HLA-A2-specific CD3ε-TRuC, TRAC-CAR Tregs and wildtype (WT), unedited Tregs. After generation, the cells underwent further expansion for 2 weeks via anti-CD3/28 coated bead stimulation every 2–3 days (Figure 3A). Gene-edited Tregs exhibited a temporary delay in cell growth within the initial 4 days after electroporation, potentially attributable to the toxicity of the electroporation procedure itself and the use of dsDNA templates. Subsequently, CD3ε-TRuC Tregs demonstrated robust expansion (Figures 3B and 3C). Surprisingly, despite CRISPR-mediated loss of the TCR/CD3-complex, TRAC-CAR Tregs also expanded during anti-CD3/28 bead stimulation, albeit at a lower rate than CD3ε-TRuC Tregs (Figures 3B and 3C). Gene editing of CD3ε was similarly efficient in Tregs and Tconvs in the absence of HDR-enhancing small molecules (Figure S5). Further, CD3ε-TRuC knock-in rates were comparable with TRAC-CAR knock-in rates in Tregs of the same donor (Figure 3D). During expansion with anti-CD3/28 bead stimulation, we observed a preferential expansion of CD3+ cells, including CD3ε-TRuC Tregs, over CD3-negative Tregs (Figure 3E). In contrast with the CD3ε-TRuC, TRAC-CAR Tregs slightly decreased in frequency along expansion. Like the relative transgene+ frequency, absolute fold expansion of gene-edited HLA-A2-redirected Tregs was higher in CD3ε-TRuC Tregs compared with their TRAC-CAR counterparts (Figures 3F and 3G).

Figure 3.

Continuous CD3/CD28 stimulation leads to preferential expansion of CD3ε-TRuC Tregs over TCR-negative Tregs

(A) Schematic pipeline of CD3ε-TruCand TRAC-CAR Tregs generation and expansion. (B) Expansion fold change of total viable cells of CD3ε-TRuC, TRAC-CAR and WT Tregs, normalized to d0. n = 4. (C) Expansion fold change of total viable cells of CD3ε-TRuC, TRAC-CAR and WT Tregs post electroporation = E' , normalized to d11. n = 4. (D) Transgene frequencies of CD3ε-TRuC Tregs and TRAC-CAR Tregs on day 11. N = 6. (E) Representative dot plots of CD3ε-TRuC (top) and TRAC-CAR (bottom) Tregs along expansion. (F) Transgene frequencies of CD3ε-TRuC and TRAC-CAR Tregs along expansion. n = 6. (G) Expansion fold change of gene-edited CD3ε-TRuC and TRAC-CAR positive Tregs, normalized to d11. n = 4. Statistical analysis in (B), (C), (F), and (G) was performed using an ordinary two-way ANOVA of matched data. Multiple comparisons were performed by comparing each cell mean with the other cell mean in that row with Tukey (B, C) or Šidák (F and G) correction. Asterisks represent adjusted p values calculated in the respective statistical tests (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001). Statistical analysis in (D) was performed using t-tests of paired data. Asterisks represent two-tailed p-value (ns, p ≥ 0.05). Summary graphs show mean values and error bars indicate standard deviation.

After a 2-week expansion after electroporation, CD3ε-TRuC, TRAC-CAR Tregs retained the canonical Treg phenotype, with more than 98% of total live Tregs expressing high levels of CD25 and FOXP3, like unedited WT Tregs (Figures 4A and 4B). Furthermore, untouched and gene-edited Tregs did not secrete T helper type 1 cytokines, e.g., IFN-γ and TNF-α, after polyclonal restimulation (Figures 4C and 4D). Analysis of the Treg-specific demethylated region (TSDR) in the FOXP3 gene locus was performed to confirm that Tregs retained epigenetic identity with or without gene editing (Figure 4E). In contrast, unedited Tconvs of the same donors were highly methylated at the TSDR, as expected (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Gene-edited and ex vivo-expanded Tregs retain their canonical phenotypic and epigenetic identities

(A) Representative dot plots of FOXP3 against CD25 among CD3ε-TRuC, TRAC-CAR, WT Tregs, and WT Tconvs. (B) Percentages of FOXP3 and CD25 double-positive cells of CD3ε-TRuC Tregs compared with TRAC-CAR and WT Tregs, 2 weeks after electroporation. Tconvs were used as gating control. n = 4. (C) Representative dot plots and (D) expression level of cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α of CD3ε-TRuC, TRAC-CAR, and WT Tregs as well as Tconvs upon PMA and Ionomycin stimulation. (E) Methylation status of 10 individual CpGs at TSDR (Treg specific demethylation region). Values shown in the Avg column indicate the averaged methylation value of 10 CpGs of each sample at TSDR. n = 2. Statistical analysis in (B) and (D) was performed using a one-way ANOVA of matched data with Geisser-Greenhouse correction. Multiple comparisons were performed by comparing each cell mean with the other cell mean in that row with Tukey correction. Asterisks represent adjusted p value (ns, p ≥ 0.05). Summary graphs show mean and error bars indicate standard deviation.

CD3ε-TRuC Tregs but not TRAC-CAR Tregs mirror activation marker patterns of clinically validated polyclonal Tregs

Next, we compared the activation profiles of CD3ε-TRuC and TRAC-CAR Tregs by measuring activation markers in response to different concentrations of plate-bound HLA-A2:Ig fusion protein (Figure S6A). Both CD3ε-TRuC and TRAC-CAR Tregs displayed dose-dependent upregulation of ICOS, CD25, FOXP3, CD137, CD71, LAP, and to a limited extent to CTLA4 and Helios (Figure S6B). CD3ε-TRuC displayed a stronger relative upregulation (compared with their respective baseline expression without stimulation) of CD25 and of CD137 compared with TRAC-CAR Tregs, especially when stimulated at a higher concentration of 5 μg/mL or 10 μg/mL of HLA-A2:Ig protein (Figure S6B). Of note, TRAC-CAR Tregs displayed higher baseline expression of ICOS, CD25, CTLA-4, CD71, and CD137, in comparison with both CD3ε-TRuC and WT Tregs and may indicate antigen-independent signaling of the CAR (Figure S6C). In contrast, CD3ε-TRuC and WT Tregs share similar activation profiles at baseline without stimulation (Figure S6C).

The non-viral gene editing protocol enabled us to manufacture CD3ε-TRuC Tregs more efficiently than TRAC-CAR Tregs (Figure 3). Further, the analysis of activation markers indicated a phenotype of CD3ε-TRuC Tregs mirroring clinically validated polyclonal Tregs (Figure S6). Moreover, Tregs deficient of the endogenous TCR have been shown to possess reduced suppressive function.40 Consequently, the in-depth functional characterization of gene-edited Tregs was focused on the CD3ε-TRuC gene editing strategy.

CD3ε-TRuC Tregs are dual-responsive and exert in vitro suppression after both TCR and TRuC engagement

To validate signaling after TCR or antigen receptor engagement, we performed flow cytometric analysis of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (Figure 5A). Before the functional assays in vitro, the expanded CD3ε-TRuC Tregs were sorted to achieve a highly purified cell population for comparison of CD3ε-TRuC to WT Tregs (Figure S7). Upon stimulation with plate-bound anti-CD3 mAb, CD3ε-TRuC Tregs displayed time-dependent phosphorylation of ERK at similar extents to WT Tregs (Figures 5B, left, and S8). Stimulation with plate-bound HLA-A2:Ig protein only led to ERK phosphorylation in CD3ε-TRuC Tregs but not unedited WT Tregs (Figure 5B, right).

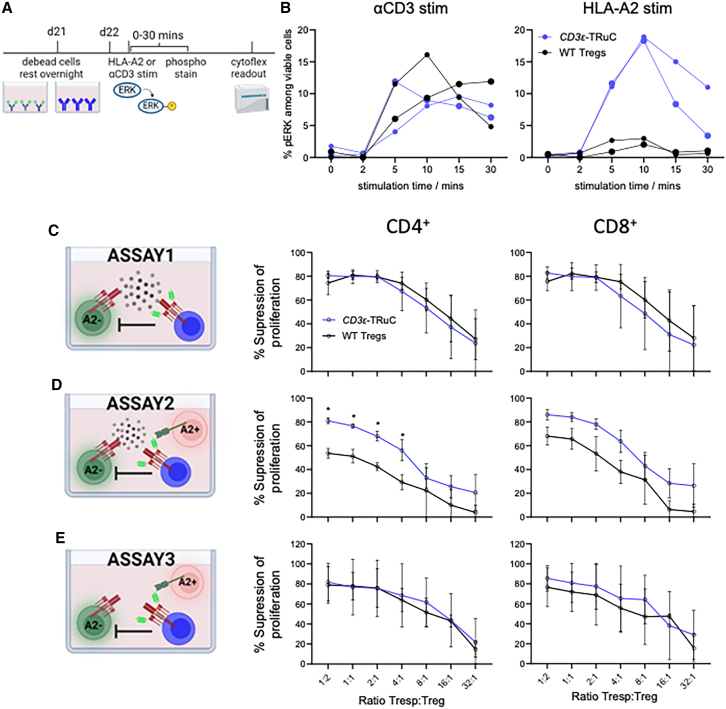

Figure 5.

CD3ε-TRuC Tregs upregulated ERK signaling pathway and demonstrated potent suppressive autologous and allogeneic Tconv proliferation in vitro regardless of polyclonal or HLA-A2 antigen-specific stimulation

(A) Experimental setup of phosphorylation flow assay. (B) Kinetics of phosphorylation of ERK upon either 10 μg/mL αCD3 (left) or 5 μg/mL HLA-A2 (right) stimulation. A relatively smaller circular dot represents one donor, and a relatively bigger circular dot represents another donor. n = 2. Proliferation suppression percent of CD4+ Tconvs (left) and CD8+ Tconvs (right) of CD3ε-TRuC and WT Tregs (C) upon polyclonal bead stimulation, (D) upon polyclonal bead and HLA-A2+ CD3-depleted PBMCs stimulation, and (E) upon HLA-A2+ CD3-depleted PBMCs stimulation.

Data shown in (C), (D), and (E) are the averaged values of three donors with three technical replicates each. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using an ordinary two-way ANOVA of matched data. Multiple comparisons were performed by comparing each cell mean with the other cell mean in that row with Šidák correction. Asterisks represent adjusted p values calculated in the respective statistical tests (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

Suppression of the unwanted proliferation of Tconv specific to auto- or allo-antigens is a major aim of Treg transfer, and this can be partially modeled in vitro. We used three different proliferation suppression assays for comparison of CD3ε-TRuC Tregs and WT Tregs and evaluated the impact of the engineered antigen-specificity (Figures 5C–5E): the first assay (1) represents the standard proliferation suppression assay using autologous responder T cells (Tresps) stimulated with anti-CD3/28 beads together with different amounts of Tregs, but lacking an HLA-A2-specific stimulant. In this assay, CD3ε-TRuC Tregs and WT Tregs suppressed the proliferation of autologous Tresp in a dose-dependent manner in all three examined donors (Figure 5C), with more than 50% suppression capacity, even at the lowest examined ratio of 32:1 (Tresp:Treg) in one donor (Figure S9B, top). CD3ε-TRuC Tregs showed a significantly better Tresp proliferation suppression than WT Tregs at higher ratios of 1:2 for CD4+ Tresp and of 1:2, 1:1 and 2:1 for CD8 counterpart in one donor (Figure S9B, top). In the second assay (2), additional HLA-A2+ CD3-depleted PBMCs were added to serve as stimulant for the CAR/TRuC receptors. CD3ε-TRuC Tregs displayed a greater suppressive capacity in all three donors (Figures 5D and S9B–S9D, middle). Relatively, WT Tregs were less suppressive in the additional presence of HLA-A2+ cells compared with their capacity after anti-CD3/28 bead stimulation alone. The third assay (3) aimed to model allogeneic T cell proliferation toward the unmatched HLA-A2+ CD3-depleted PBMCs and no additional anti-CD3/28 beads were included. As expected, the overall percentage of proliferating Tresps was much lower than the Tresp stimulated using anti-CD3/28 beads as stimulant (Figure S9A). In general, a comparable proliferation suppression capacity between CD3ε-TRuC Tregs and WT Tregs was observed in all donors, despite a considerable donor variation (Figures 5E and S9B–S9D, bottom). Overall, CD3ε-TRuC Tregs showed high suppressive capacity in autologous and allogeneic proliferation suppression assays in vitro.

CD3ε-TRuC Tregs efficiently prevented allogeneic cell and tissue rejection in vivo

Next, we evaluated our HLA-A2-specific CD3ε-TRuC Tregs in a humanized in vivo mouse model for allogeneic cell rejection.41 In this model, immunodeficient mice are engrafted with HLA-A2- PBMCs from the same donor used for Treg engineering 2 weeks before the beginning of the experiment. Successful reconstitution was confirmed by flow cytometry (Figure S10). Then, two different fluorescently labeled PBMCs were infused; one fraction contains autologous (auto-) PBMCs and the other fraction contains allogeneic (allo-) PBMCs from an unmatched HLA-A2+ donor. Co-administration of autologous Tregs should protect HLA-A2+ PBMCs from rejection and result in a higher allo-PBMCs to auto-PBMCs ratio at the end of the challenge (Figure 6A). The allo-PBMC to auto-PBMC ratio was measured before injection right after mixing as baseline (planned ratio of 1:1, with actual ratio of 1:1.63, likely due to cell count variation before mixing). CD3ε-TRuC Tregs significantly protected allo-PBMCs from rejection as unedited WT Tregs did (Figures 6B and 6C). These results indicate similar suppressive capacity of CD3ε-TRuC Tregs, comparable with the clinically proven polyclonal Treg product.10,11

Figure 6.

CD3ε-TRuC Tregs efficiently prevented allogeneic cell and tissue rejection in vivo

(A) Experimental design of a short-term allogeneic donor PBMC rejection model in NSG mice in vivo. (B) Representative FACS dot plots indicating the ratio of allogeneic PBMCs to autologous PBMCs before injection and after injection with or without CD3ε-TRuC Tregs or WT Tregs. (C) Survival rates of allogeneic PBMCs in vivo. n = 3–5. Bar graph shows mean valueas and error bars indicate standard deviation. (D) Experimental setup of a long-term skin transplant model in NSG mice in vivo. (E) Survival curves of skin graft upon allogeneic PBMCs and CD3ε-TRuC Tregs or WT Tregs cell transfer. (F) The median days to GS6 (graft scoring 6 – complete rejection) for each group are shown. N = 5–6. Statistical analysis in (C) was performed using a one-way ANOVA of matched data. Asterisks represent adjusted p values calculated in the respective statistical tests (∗p < 0.05).

To examine whether CD3ε-TRuC Tregs can display improved HLA-A2-specific suppressive capacity over WT Tregs, we performed a long-term skin transplant injection model42 in vivo (Figure 6D). BALB/c Rag2−/−cγc−/− mice were transplanted with human HLA-A2+ skin graft for 35 days until mice received allogeneic HLA-A2- PBMCs (the same donor used for Treg engineering) alone or with its autologous WT Tregs or CD3ε-TRuC Tregs at a PBMCs:Tregs ratio of 5:1. At this high ratio of PBMCs:Tregs, polyclonal unedited WT Tregs were unable to efficiently protect the skin allografts from rejection (Figure 6E), ending up with a median time to complete graft rejection (defined by graft score of 6 [GS6]; see materials and methods) of 52.5 days similar to the condition which only received the PBMC injection (Figure 6F). However, mice that received PBMCs and CD3ε-TRuC Tregs at a ratio of 5:1 achieved an improved long-term engraftment of the human HLA-A2+ skin allograft with a median time to GS6 of more than 100 days (Figures 6E and 6F). Phenotypic characterization of skin graft by immunohistochemistry demonstrated the presence of donor-derived antigen-presenting cells in skin grafts (Figure S11). These data collectively demonstrated the superior antigen-specific suppression capacity of CD3ε-TRuC Tregs over unedited polyclonal WT Tregs in a long-term skin transplant model.

Discussion

This study describes an effective and GMP-compatible strategy uniquely suited to redirect Tregs (and other T cells) with TRuC receptors using non-viral CRISPR-Cas12a gene editing of the CD3ε gene. Insertion of the scFv and a G4S linker into the endogenous CD3ε created TCR+/TRuC+ Tregs that could be enriched over time using anti-CD3/CD28 bead stimulation. The HLA-A2-specific gene-edited Tregs retained an epigenetic and phenotypic profile of clinically used first-generation unedited polyclonal Treg products, but benefited from the additional alloantigen specificity during in vitro and in vivo functional tests, compared with polyclonal WT Treg cells. In the clinically relevant tissue allograft transplantation model, a relatively low number of HLA-A2-specific CD3ε-TRuC Tregs improved the median survival of skin grafts over polyclonal Tregs. The promising data of the HLA-A2 specific CD3ε-TRuC approach delivers a blueprint for generating redirected Treg applicable for various immunopathologies.

Non-viral gene editing is a promising approach to create genetically modified Tregs for therapeutic applications14 due to economic advantages of non-viral vectors and a reduced risk of insertional mutagenesis. Efficient non-viral knock-ins into Tregs have been reported previously with SpCas9.25,35,43,44 The minimal transgene size of CD3ε-TRuC strategy is advantageous, because linear dsDNA templates display significant dose- and also size-dependent toxicity in T cells.25,28,35,43 Further, the relative HDR rate depends on the targeted locus, transgene size, and the indel profile of the nuclease.25,28,43,45 AsCas12a cleaves the DNA distant of the protospacer adjacent motif and creates staggered ends, which was proposed as ideal for HDR.46 Another potential advantage of Cas12a over Cas9 is the greater specificity.46,47 Additionally, CAST-Seq could not detect off-target-mediated translocations, suggesting high precision of the preferred crRNA-AsCas12a complex. Other unbiased assays will be needed to confirm the absence of off-target gene editing in CD3ε-TRuC Tregs before clinical use.

The CD3ε-TRuC gene editing strategy provides an elegant solution to redirect Tregs toward diverse antigens with a unified manufacturing protocol agnostic to the targeted antigen. Targeted gene insertion requires selection of a suitable locus for the respective application. Previously, TRAC was the gold standard for knock-in of second-generation CARs.30 Miniaturization of the CAR transgene has been proposed by inserting truncated CD3ζ-deficient second-generation CARs into the CD3ζ gene in Tconvs and Tregs.44 Both approaches, TRAC26 and CD3ζ,44 eliminate TCR surface expression in Tregs and require the adaptation of manufacturing to enrich redirected Tregs via constant antigen stimuli. Like our approach, SpCas9-mediated CD3ε gene editing was used to create TRuC+ Tconvs with minimized transgenes.48,49 In Tregs, the CD3ε-TRuC approach enables the unique opportunity of the minimized transgene and selects for the reprogrammed Tregs by repetitive anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation applied in standard expansion protocols. In contrast, repetitive TCR/CD3-stimulation is inadvisable in Tconvs due to activation-induced cell death and heightened differentiation ex vivo,50 which is associated with poor effector function in vivo.50,51,52,53 Safe harbor loci may also allow the expression of CAR/TRuC in Tregs without affecting TCR expression, but these sites would require the integration of larger transgene expression cassettes and do not enable automatic selection.54 Essential genes, such as GAPDH, may be adopted for automatic selection, but fail to provide natural regulation of CAR expression.55 Future studies may be required to evaluate whether the natural regulation of CD3ε-TRuC provides an advantage when compared with stable overexpression.

Conventional second-generation CAR architectures were shown to destabilize the suppressive program of Tregs,31 emphasizing the need to re-evaluate the optimal antigen receptor formats for Tregs. TRuC receptors exploit the endogenous TCR/CD3 complex and provide more physiological signaling to T cells.36,56 Retrovirally transduced TRuC Tregs specific for factor VIII autoantigen demonstrated superior suppressive capacity over CAR Tregs expressing a second-generation CAR with the CD28 costimulatory domain in a syngeneic mouse model. Using CD3ε gene editing, we could generate TCR+/TRuC+ Tregs that responded via TCR and TRuC, respectively, similar to retrovirally transduced TRuC Tregs.57 CD3ε-TRuC Tregs automatically enrich within the GMP protocols relying on anti-CD3/28 bead stimulation, enhancing the overall redirected Tregs yields over TCR-deficient CAR Tregs in this study. A potential disadvantage of TRuC architecture is the lack of co-stimulatory signal by the synthetic antigen receptor. However, murine Tregs reprogrammed with first-generation CARs lacking a co-stimulatory domain displayed comparable suppressive capacity with second-generation CAR-Tregs in syngeneic allo-transplantation models in mice.58 Rosado-Sanchez et al.58 have demonstrated that professional antigen-presenting cells can provide co-stimulation to first-generation CAR-Tregs in trans. Therefore, CD3ε-TRuC Tregs are likely suitable for allograft protection without the need of artificial co-stimulatory signaling in the presence of donor-derived antigen-presenting cells (Figure S11). Future studies may investigate other co-stimulatory receptors59,60 to improve CD3ε-TRuC Treg functionality at inflamed sites, such as the allograft.

Engineered CD3ε-TRuC Tregs may also benefit from other modifications to improve their functionality.14 To promote immunosuppression and protect transplanted organs from rejection in patients, CD3ε Tregs could be further enhanced by gene editing to induce drug resistance61,62 or providing artificial IL-2 cytokine signals.63,64 Here, the minimized transgene size may enable easier co-delivery of therapeutic transgenes, both the HLA-A2 scFv construct and therapeutic enhancer elements mentioned above. Further, our Cas12a knock-in strategy would allow combination with SpCas9-derived enzymes in a single transfection for additional multiplex gene editing with minimal translocations.65 Finally, multiplex gene editing may allow to combine edits for enhanced functionality, such as FOXP3 stabilization.66 Importantly, modifications of HLA,67 such as KOs of B2M and CIITA, and knock-in of a non-polymorphic HLA molecular gene HLA-E, were shown to protect multiplex gene-edited Treg cells from rejection by host T cells and natural killer cells, potentially enabling successful off-the-shelf Treg applications in the future.

Materials and Methods

Polyclonal Treg cell isolation and expansion

All experiments in this study were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Peripheral blood was obtained from healthy human adults after informed consent (Charité ethics committee approvals EA4/091/19 and EA1/052/22). HLA-A2 phenotype of healthy donors was determined by flow cytometry using an anti-human HLA-A2 antibody conjugated with APC (BB7.2, BioLegend) or FITC (A28, Miltenyi Biotec). Only Tregs of HLA-A2 negative donors were used for gene editing in this study. An amount of 120 mL peripheral blood was obtained from healthy donors and PBMCs were isolated using the standard density gradient centrifugation approach with Biocoll separation solution (Bio&SELL). CD4+ T cells were positively enriched using magnetic column enrichment with human CD4 microbeads according to the manufacturer's recommendations (LS columns, Miltenyi Biotec). Enriched CD4+ T cells were stained with a cocktail of antibodies: anti-CD4 VioBlue (REAQL103), anti-CD25 APC (REAL128), anti-CD127 PE-Vio770 (REAL102), and anti-CD45RA FITC (REAL164), all from Miltenyi Biotec as well as anti-CCR7 PE (G043H7, BioLegend). CD4+CD25highCD127lowCCR7+ Tregs were sorted in a fully closed environment using a GMP-compatible Tyto sorter (Miltenyi Biotec). Sort purity of CCR7+ Tregs was checked on a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) after a two consecutive sorting manner. We seeded 1 × 105 cells in 1 well of a 96-well U plate (Corning) with 200 μL of Treg medium consisting of X-VIVO 15 medium (Lonza), 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Sigma-Aldrich), 500 IU/mL recombinant human IL-2 (Miltenyi Biotec), and 100 nM rapamycin (Pfizer). All cell culture experiments were performed at a 37°C and 5% CO2 incubator. For initial stimulation, 4 × 105 Treg expansion beads (Miltenyi Biotec) were added to each well on the next day. Cell culture medium was replenished every 2–3 days. Cells were counted on day 5 and were stimulated with Treg expansion beads at a ratio of 1:1 for an additional 2 days until electroporation.

Tconv isolation and stimulation

CD3+ T cells were positively enriched using magnetic column enrichment with human CD3 microbeads according to the manufacturer's recommendations (LS columns, Miltenyi Biotec). Enriched T cells were cultured in T cell medium containing RPMI 1640 (Gibco), 10% FCS (Sigma-Aldrich), recombinant human IL-7 (10 ng/mL, Cell-Genix), and recombinant human IL-15 (5 ng/mL, Cell-Genix). Tconvs were stimulated via plate-bound 1 μg/mL anti-CD3 antibody (OKT3, Invitrogen) and 1 μg/mL anti-CD28 antibody (CD28.2, BioLegend) for 48 h before electroporation.

Screening of synthetic crRNAs targeted on CD3ε locus by electroporation

Five guide crRNAs were selected (Table S1) for screening based on the criteria of CFD off-target less than 5–10 calculated by CRISPR scan68 and COSMID.69 These crRNAs were synthesized from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). Before electroporation, mixing of 0.5 μL of poly(L-glutamic acid) (100 μg/μL PGA, 15- to 50-kDa, Sigma-Aldrich) with 0.48 μL of crRNA (100 μM) and 0.4 μL Alt-R A.s. Cas12a (Cpf1) Ultra (10 μg/μL = 63 μM, IDT) by thorough pipetting, with a final ratio of crRNA:Cas12a at approximately 2:1. The mixture was incubated for 15 min at room temperature to allow for RNP formation. T cells were washed twice in PBS (Gibco) and 1 × 106 cells were resuspended in 20 μL of P3 buffer (Lonza). Electroporation was performed in a 16-well nucleocuvette strip on a 4D-Nucleofector Device (Lonza) using the program EH-115. KO efficiency was checked on day 4 after electroporation, and cells were stained with CD3 PacBlue (UCHT1, BioLegend) and DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and acquired on a CytoFLEX LX (Beckman Coulter). For more details, see Kath et al.28

Generation of HDR-template for generation of TRAC-CAR and CD3ε-TRuC

Four HDR templates were used in this study, with one for integration in exon 1 of the TRAC locus one for integration in exon 6 of the CD3E locus, and the other two for integration in exon 3 of the CD3Ε locus, respectively. Anti-human HLA-A2 scFv (clone 3PF12) was used32 and its cDNA sequence is available on GenBank (accession numbers AF163307 and AF163308). Anti-human HER2 scFv (clone FPR5) cDNA sequence was derived from a published patent (US8530637B2). Each donor template was designed in Snapgene (Dotmatics) and synthesized by IDT as gBlocks gene fragments with detailed nucleic acid sequences found in Table S3. gBlocks were cloned in plasmid PUC19 vector backbone using multiple-fragment In-Fusion cloning according to the manufacturer's recommendation (Clontech, Takara). Plasmid transformation, colony PCR, and plasmid purification and validation were previously described.28 HA-flanked HDR templates were amplified from the validated plasmids by PCR using the KAPA HiFi HotStart 2× Readymix (Roche). Primers used in this study can be found in Table S4. PCR products were purified and concentrated using paramagnetic beads (AMPure XP, Beckman Coulter Genomics). The concentration of HDR-templates was determined by using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and a Qubit Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). HDR templates were adjusted to a concentration of 1 μg/μL in nuclease-free water and stored at −20°C until use.

Gene editing of Tregs with HDR templates via electroporation

Upon 7–9 days of stimulation of Tregs, beads were removed by a MACSiMAG separator (Miltenyi Biotec) and bead-free Tregs were washed in PBS and suspended in P3 buffer as Tconvs. We used 0.5 μg of TRAC-CAR HDR-template or CD3ε-TRuC HDR-template to mix with RNP and cell suspension before electroporation. Same as Tconvs, electroporation was performed on a 4D-Nucleofector Device (Lonza) using the program EH-115. To rescue cells, 90 μL of pre-warmed Treg medium was added to each well immediately after electroporation, incubated for 10 min in a 37°C incubator before evenly transferring them to 2 wells of a 96-well U plate containing 150 μL pre-warmed Treg medium. For CD3ε-TRuC Tconv generation, 0.5 μM HDR Enhancer V2 was incorporated in the culture medium to enhance knock-in rate.28 On the next morning after nucleofection, Treg cells were stimulated with Treg expansion beads at a ratio of 1:1.

CAST-Seq analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel). CAST-Seq analyses were performed following the previously described protocol39 with some adjustments to the workflow.70 In brief, the average fragmentation size of the genomic DNA was aimed at a length of 500 bp. The libraries were sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 using 2 × 150 bp paired-end sequencing (GENEWIZ, Azenta Life Sciences). Changes were made to the bioinformatic pipeline to enhance specificity. Sites under investigation were categorized as OMT if the p value met the cutoff of 0.005. In addition, further features were incorporated in the CAST-Seq algorithm, including barcode hopping annotation and an update to the coverage analysis to reduce the execution time by aligning the gRNAs only to the most covered regions for each site. Two technical replicates from samples of two different donors were used for the CAST-Seq analysis. Only sites identified as significant hits in both biological replicates were considered as putative events. Results are shown in Figure 2A and Table S2.

T7E1 assay

Briefly, 50 ng of genomic DNA was subjected to PCR reaction and 100 ng of the resulting amplicons were subjected to a slow reannealing for 5 min at 95°. The product was then digested with T7E1 (NEB) at 37°C for 20 min and then resolved through a 2% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Expansion of CD3ε-TRuC and TRAC-CAR Tregs

TRAC-CAR Tregs were initially stimulated with either (1) plate-bound 2 μg/mL HLA-A2:Ig fusion protein (BD), or (2) plate-bound 2 μg/mL HLA-A2:Ig fusion protein (BD) with plate-bound 1 μg/mL anti-CD28 (BioLegend), or (3) gamma-irradiated (30 Gy) HLA-A2+ K562 cell line at a ratio of 1:1. Stimulation and medium replenishment were repeated every 2–3 days. Subsequently, CD3ε-TRuC and TRAC-CAR Tregs were expanded with Treg expansion beads (Miltenyi Biotec) every 2–3 days at a cell-bead ratio of 1:1 for 2 weeks after electroporation. The beads were removed and bead-free Tregs rested overnight before in vitro assay setup. Of note, WT Tregs were activated and expanded in the same manner as gene-edited Tregs.

Gene editing efficiency check by flow cytometry

TRAC-CAR Tregs were stained with anti-CD3 PB (UCHT1, BioLegend) and anti-Fc A647 (Jackson Immuno Research Labs). CD3ε-TRuC Tregs were stained with CD3 PB and anti-Myc A647 (9B11, Cell Signaling). Cells were resuspended in DAPI containing PBS before acquisition by CytoFLEX LX. Gene editing efficiency check of Tregs were performed at day 11, day 15, and day 22 upon blood withdrawal.

Phenotypic characterization of gene-edited Tregs

Tregs were stained with fixable dye Aqua (Invitrogen), were then fixed and permeabilized using Transcription Factor Buffer Set (BD). Anti-Fc A647 for TRAC-CAR Tregs and anti-Myc A647 for CD3ε-TRuC Tregs were stained intracellularly, followed by two times wash using 1× permeabilization buffer (BioLegend). Cells were then stained by an antibody cocktail of anti-CD3 PB (UCHT1, BioLegend), anti-CD4 PE (13B8.2, Beckman Coulter), anti-CD25 PC7 (B1.49.9, Beckman Coulter), and anti-FOXP3 FITC (259D/C7, BD). For cytokine profile examination of gene-edited Tregs, 3 × 105 cells were stimulated by 10 ng/mL PMA and 2.5 μg/mL Ionomycin (Sigma Aldrich) for 6 h. Brefeldin A (Sigma Aldrich) was added at a concentration of 10 μg/mL after 1 h of co-culture. Upon 6 h of stimulation, cells were harvested and stained intracellularly with anti-TNF-α A700 (Mab11, BioLegend), anti-IFN-γ APC-eF780 (4S.B3, Invitrogen), and anti-IL-2 PE-Cy7 (MQ1-17H12, BioLegend). Stained cells were acquired at Cytoflex LX.

DNA methylation analysis of the FOXP3 TSDR using bisulfite amplicon sequencing

Amplicon TSDR methylation analysis was performed as previously described.71 Briefly, 1 × 106 cells were snap-frozen and stored at liquid nitrogen until genomic DNA isolation with the Quick-DNA Microprep Kit (Zymo Research D3020) according to the manufacturer's protocol. We bisulfite-converted 200 ng of genomic DNA using an EZ-DNA methylation Gold kit (Zymo Research D5006).

PCRs were performed with input of 200 ng of bisulfite-treated DNA, 2 x KAPA HiFi Hotstart Uracil+ ReadyMix (Kapa Biosystems KK2802), 0.25 mM of each dNTP, 0.3 pmol of primers (F1: 5′ ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTTTTGGGGGTAGAGGATTTAGAGGG-3′ and R3: 5′GACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCACATCCACCAACACCCAT -3′) with Illumina compatible universal adaptor sequences attached at the 5′-end. Amplicons were purified with DNA Clean & Concentrator-5 Kit (Zymo Research D5006) and normalized to 20 ng/μL for sequencing by Genewiz/Azenta aiming at 1 × 104 reads per amplicon. Reads were aligned and evaluated using the Bismark package.72

Cytokine profiles of HLA-A2 CD3ε-TRuC and HER2 CD3ε-TRuC Tconvs

HLA-A2 CD3ε-TRuC and HER2 CD3ε-TRuC Tconvs were generated using the non-viral CRISPR-Cas approach described for Treg cell engineering. Gene-edited Tconvs were expanded for 2 weeks before cytokine profile assay. HLA-A2 CD3ε-TRuC Tconvs were co-cultured with either CFSE labeled HLA-A2+ K562, or CFSE labeled WT HLA-A2- K562, or GFP+ Nalm6 cells at a ratio of 1:1. HER2 CD3ε-TRuC Tconvs were co-cultured with either GFP+HER2+ DAOY, or CFSE labeled HER2− ONCO cells at a ratio of 1:1. Both CD3ε-TRuC Tconvs were stimulated by plate-bound 8 μg/mL of αCD3 antibody (OKT3, Invitrogen). Brefeldin A (Sigma Aldrich) was added at a concentration of 10 μg/mL after 1 h of co-culture. Upon 6 h of stimulation, cells were harvested and stained with fixable live/dead dye UV (Invitrogen). Cells were then fixed and permeabilized before intracellularly stained with anti-Myc A647 (9B11, Cell Signaling), anti-CD3 PB (UCHT1, BioLegend), anti-CD4 PE (13B8.2, Beckman Coulter), anti-CD8 BV510 (SK1, BioLegend), anti-TNF-α A700 (Mab11, BioLegend), anti-IFN-γ APC-eF780 (4S.B3, Invitrogen), and anti-IL-2 PE-Cy7 (MQ1-17H12, BioLegend). Stained cells were acquired at Cytoflex LX.

Activation profiles of CD3ε-TRuC versus TRAC-CAR Tregs

Tregs were rested overnight without IL-2, rapamycin, and beads. Plate coating of HLA-A2: Ig dimer (BD) in a serial dilution of 10/5/2.5/1 μg/mL with 1 μg/mL anti-CD28 antibody in a 96-well flat plate was prepared 1 day in advance. We stimulated 4 × 105 CD3ε-TruC and TRAC-CAR as well as WT Tregs for 24 h, respectively. Upon 24 h stimulation, cells were stained with antibodies: anti-CD25 PC7 (B1.49.9, Beckman Coulter), anti-CD71 BV786 (M-A712, BD bioscience), anti-FOXP3 FITC (259D/C7, BD), anti-ICOS BV650 (C398.4A), anti-LAP PE (S20006A), anti-CTLA-4 BV421 (BNI3), anti-CD137 PE (4B4-1), anti-CD154 BV421 (24-31), and anti-Helios Percp-Cy5.5 (22F6) (all from BioLegend). Among them, anti-Helios and anti-FOXP3 antibodies were stained intracellularly.

Purification of gene-edited Tregs using a Tyto sorter

CD3ε-TRuC Tregs were sorted as Myc+ using a Tyto sorter. Two continuous rounds of sorting were performed to achieve a high purity. Sorted cells were further expanded with Treg expansion beads and were used for in vitro phosphorylation assays and suppression assays.

Phosphorylation of ERK upon stimulation

Plate coating of either 5 μg/mL HLA-A2:Ig dimer (BD) or 10 μg/mL anti-CD3 antibody (Invitrogen) was prepared 1 day in advance. Tregs were first stained with fixable live/dead dye UV (Invitrogen). Were s 5 × 105 cells to each well by a short spin down, then immediately incubated at 37°C on a thermomixer (Eppendorf). Upon indicated time period: 0 min, 2 min, 5 min, 10 min, 15 min, and 30 min, 200 μL of pre-warmed 4% fixation buffer (BioLegend) was added to cells for additional 15 min incubation. Cells were then washed with 200 μL of True-Phos perm buffer (pre-cooled at −20°C, BioLegend) and incubated at −20°C for 60 min. Cells were washed twice with PBS before intercellular stain with anti-ERK1/2 Phospho (Thr202/Tyr204) FITC (6B8B69, BioLegend) for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed twice with PBS and acquired at Cytoflex LX.

Suppression assay

Autologous Tconvs were enriched from PBMCs as responder cells (Tresp). Tresps were labeled with 1 μM of CFSE (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 min at 37°C. We seeded 5 × 104 labeled Tconv in each well of a 96-well U plate. Tregs were seeded at various ratios of Tresp to Treg ranging from 1:2 to 32:1. Three stimuli conditions were tested in this study: (1) using Treg suppression inspector, human (beads, Miltenyi Biotec) at a 1:1 ratio of total seeded cells per well to beads; (2) using polyclonal beads and HLA-A2+ CD3-depleted PBMCs that were pre-labeled with CT FarRed (Thermo Fisher) at a 1:1:1 ratio to Tresps + Tregs; and (3) using HLA-A2+ CD3-depleted PBMCs at a ratio of 1:1 to Tresps + Tregs. Each condition has technical triplicates. Wells containing Tresps with stimulus but not Tregs were served as positive control of proliferation. Wells containing Tresps alone served as negative controls of proliferation. Cells were all resuspended in X-VIVO 15 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Upon 5 days of co-culture, cells were harvested and stained with anti-CD4 PE (13B8.2, Beckman Coulter) and anti-CD8 PE-Cy7 (RPA-T8, BD Pharmingen) and resuspended in DAPI containing PBS for immediate acquisition at Cytoflex LX. % Suppression capacity of Tregs = (% divided Tresp alone − % divided Tresp treated with Tregs)/% divided Tresp alone × 100.

Allogeneic rejection mouse model

The in vivo functionality of genetically edited Tregs was evaluated using an allogeneic rejection model in NOD.Cg-Rag1tm1MomIl2rγtm1Wjl/SzJZtm (NRG) mice, as described by Henschel et al.41 NRG mice were bred in a pathogen-free environment at the animal facility of Hannover Medical School (Hannover, Germany). All animal procedures were approved by the local Animal Ethics Review Board (Oldenburg, Germany, 21/3621) and conducted in compliance with prevailing German regulations. NRG mice were reconstituted with 5 × 106 autologous HLA-A2∗02:01-negative PBMCs. Successful reconstitution was confirmed via whole blood analysis obtained from the submandibular vein after 2 weeks, using staining with anti-hCD4 BV421 (RPA-T4; BioLegend) and anti-hCD8 APC (SK1; BioLegend). On day 14, mice subjected to the in vivo killing experiments were intravenously injected with 5 × 105 allogeneic HLA-A02:01-positive PBMCs labeled with eF670 (5 μM, CellTrace, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 5 × 105 syngeneic HLA-A02:01-negative PBMCs labeled with CFSE (0.5 μM, CellTrace, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a 1:1 ratio, along with 5 × 105 WT or CD3ε-TRuC Tregs. Five days after transfer, splenic cells were isolated, and the survival of allogeneic target cells was assessed via flow cytometry.

Humanized skin allograft mouse model

The skin allograft model was performed as previously described. Briefly, BALB/cRag2−/−cγc−/− mice (Jackson Laboratory) were housed in individually ventilated cages under specific pathogen-free conditions. All protocols were conducted in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (1986) and approved by Oxford University’s Committee on Animal Care and Ethical Review. Human skin was procured with full informed written consent and with ethical approval from the Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee (REC B), study number 07/H0605/130. We surgically grafted 1 cm2 HLA-A2 positive human skin graft onto the flank of BALB/cRag2−/−cγc−/− recipient. Anti-human CD45 (HI30, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and anti-HLA-DR (LN3, Thermo Fisher Scientific) antibodies were used to stain the skin slide sections with a previously well-established hematoxylin and eosin protocol73 to phenotype skin graft pre-transplantation and post-transplantation in mice. Age- and sex-matched mice were used. Five weeks after skin grafting, mice received 5 × 106 cryopreserved PBMCs (same as Treg donor) in pure RPMI 1640 medium via intra-peritoneal injection, with or without 1 × 106 in vitro-expanded WT Tregs or HLA-A2-specific CD3ε-TRuC Tregs. Grafts were observed for macroscopic markers of rejection by an assessor blinded to treatment groups. Mice were sacrificed after either graft rejection or at day 100 post-transplantation by cervical dislocation.

Data analysis and statistics

Flow cytometry data were analyzed with FlowJo software v.10 (BD). Graphs and statistical analyses were created using Prism 9 (GraphPad). T7E1 indel percent was calculated by ImageJ analysis. Graphical abstract and experimental setup schemes were created with BioRender.com.

Data availability

The sequences for the HDR templates including the CAR and TRuC constructs are available in the Table S3. Any raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the following individuals for their valuable contributions: Anne Schulze from Julia Polansky group (BIH, Berlin, Germany) for her technical assistance with the TSDR experiment presented in Figure 4E. Sarah Schulenberg from Michael Schmueck-Henneresse group (Charité, Berlin, Germany) for sharing her phosphorylation flow cytometry protocol. Cell sorting was performed using the Tyto sorter instrument at the BIH Core Unit for pluripotent Stem Cells and Organoids (BIH-CUSCO). Geoffroy Andrieux (from the Institute of Medical Bioinformatics and Systems Medicine, Medical Center-University of Freiburg) for his help with the bioinformatic part in the CAST-Seq pipeline. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon research and innovation program under grant agreements no. 825392 (ReSHAPE) and no. 101057438 (geneTIGA) and by the European Research Council (ERC) under the ERC starting grant EpiTune (Grant Agreement Nr. 803992 to J.K.P.). The views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union, the European Health and Digital Executive Agency (HADEA), or the ERC. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Author contributions

W.D. designed parts of the study, planned, and performed experiments, analyzed results, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. F.N., O.M., V.D., V.G., and C.F.-G. planned and performed experiments, analyzed results, interpreted the data, and edited the manuscript. J.K. designed HLA-A2-specific CAR and HER2-specific CAR constructs, performed experiments, interpreted data and edited the manuscript. M.Y., M.S., C.F., and Y.P. performed experiments and analyzed results. O.W. provided reagents, interpreted results and edited the manuscript. J.K.P., T.C., J.H., F.I., E.J., H.-D.V., P.R., and M.S.-H. supervised parts of the study, provided reagents, interpreted data and edited the manuscript. D.L.W. designed and led the study, planned experiments, analyzed results, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript in its final form.

Declaration of interests

W.D, J.K., H.-D.V., P.R., M.S.-H., and D.L.W. are listed as inventors on a patent application (EP4353252A1) related to the work presented in this manuscript. H.-D.V. is co-founder and CSO at CheckImmune GmbH. P.R., H.-D.V., O.W., and D.L.W. are co-founders of the startup TCBalance Biopharmaceuticals GmbH focused on Treg therapy. The Wagner lab at Charité received reagents related to gene editing in T cells from GenScript Inc. and Integrated DNA Technologies.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2025.01.045.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Sakaguchi S., Yamaguchi T., Nomura T., Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu W., Putnam A.L., Xu-Yu Z., Szot G.L., Lee M.R., Zhu S., Gottlieb P.A., Kapranov P., Gingeras T.R., Fazekas de St Groth B., et al. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:1701–1711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seddiki N., Santner-Nanan B., Martinson J., Zaunders J., Sasson S., Landay A., Solomon M., Selby W., Alexander S.I., Nanan R., et al. Expression of interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-7 receptors discriminates between human regulatory and activated T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:1693–1700. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gootjes C., Zwaginga J.J., Roep B.O., Nikolic T. Defining Human Regulatory T Cells beyond FOXP3: The Need to Combine Phenotype with Function. Cells. 2024;13:941. doi: 10.3390/cells13110941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.San Segundo D., Fernández-Fresnedo G., Rodrigo E., Ruiz J.C., González M., Gómez-Alamillo C., Arias M., López-Hoyos M. High regulatory T-cell levels at 1 year posttransplantation predict long-term graft survival among kidney transplant recipients. Transpl. Proc. 2012;44:2538–2541. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gronert Álvarez A., Fytili P., Suneetha P.V., Kraft A.R.M., Brauner C., Schlue J., Krech T., Lehner F., Meyer-Heithuis C., Jaeckel E., et al. Comprehensive phenotyping of regulatory T cells after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:381–395. doi: 10.1002/lt.24050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miura Y., Thoburn C.J., Bright E.C., Phelps M.L., Shin T., Matsui E.C., Matsui W.H., Arai S., Fuchs E.J., Vogelsang G.B., et al. Association of Foxp3 regulatory gene expression with graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2004;104:2187–2193. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rezvani K., Mielke S., Ahmadzadeh M., Kilical Y., Savani B.N., Zeilah J., Keyvanfar K., Montero A., Hensel N., Kurlander R., Barrett A.J. High donor FOXP3-positive regulatory T-cell (Treg) content is associated with a low risk of GVHD following HLA-matched allogeneic SCT. Blood. 2006;108:1291–1297. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreira L.M.R., Muller Y.D., Bluestone J.A., Tang Q. Next-generation regulatory T cell therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:749–769. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0041-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roemhild A., Otto N.M., Moll G., Abou-El-Enein M., Kaiser D., Bold G., Schachtner T., Choi M., Oellinger R., Landwehr-Kenzel S., et al. Regulatory T cells for minimising immune suppression in kidney transplantation: phase I/IIa clinical trial. BMJ. 2020;371 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landwehr-Kenzel S., Müller-Jensen L., Kuehl J.-S., Abou-El-Enein M., Hoffmann H., Muench S., Kaiser D., Roemhild A., von Bernuth H., Voeller M., et al. Adoptive transfer of ex vivo expanded regulatory T cells improves immune cell engraftment and therapy-refractory chronic GvHD. Mol. Ther. 2022;30:2298–2314. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marek-Trzonkowska N., Myśliwiec M., Dobyszuk A., Grabowska M., Derkowska I., Juścińska J., Owczuk R., Szadkowska A., Witkowski P., Młynarski W., et al. Therapy of type 1 diabetes with CD4(+)CD25(high)CD127-regulatory T cells prolongs survival of pancreatic islets - results of one year follow-up. Clin. Immunol. 2014;153:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voskens C., Stoica D., Rosenberg M., Vitali F., Zundler S., Ganslmayer M., Knott H., Wiesinger M., Wunder J., Kummer M., et al. Autologous regulatory T-cell transfer in refractory ulcerative colitis with concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 2023;72:49–53. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327075. gutjnl-2022-327075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amini L., Greig J., Schmueck-Henneresse M., Volk H.-D., Bézie S., Reinke P., Guillonneau C., Wagner D.L., Anegon I. Super-Treg: Toward a New Era of Adoptive Treg Therapy Enabled by Genetic Modifications. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:611638. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.611638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landwehr-Kenzel S., Issa F., Luu S.H., Schmück M., Lei H., Zobel A., Thiel A., Babel N., Wood K., Volk H.D., Reinke P. Novel GMP-compatible protocol employing an allogeneic B cell bank for clonal expansion of allospecific natural regulatory T cells. Am. J. Transpl. 2014;14:594–606. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawson N.A.J., Rosado-Sánchez I., Novakovsky G.E., Fung V.C.W., Huang Q., McIver E., Sun G., Gillies J., Speck M., Orban P.C., et al. Functional effects of chimeric antigen receptor co-receptor signaling domains in human regulatory T cells. Sci. Transl Med. 2020;12 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaz3866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proics E., David M., Mojibian M., Speck M., Lounnas-Mourey N., Govehovitch A., Baghdadi W., Desnouveaux J., Bastian H., Freschi L., et al. Preclinical assessment of antigen-specific chimeric antigen receptor regulatory T cells for use in solid organ transplantation. Gene Ther. 2023;30:309–322. doi: 10.1038/s41434-022-00358-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schreeb K., Culme-Seymour E., Ridha E., Dumont C., Atkinson G., Hsu B., Reinke P. Study Design: Human Leukocyte Antigen Class I Molecule A∗02-Chimeric Antigen Receptor Regulatory T Cells in Renal Transplantation. Kidney Int. Rep. 2022;7:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2022.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacDonald K.G., Hoeppli R.E., Huang Q., Gillies J., Luciani D.S., Orban P.C., Broady R., Levings M.K. Alloantigen-specific regulatory T cells generated with a chimeric antigen receptor. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126:1413–1424. doi: 10.1172/JCI82771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noyan F., Zimmermann K., Hardtke-Wolenski M., Knoefel A., Schulde E., Geffers R., Hust M., Huehn J., Galla M., Morgan M., et al. Prevention of Allograft Rejection by Use of Regulatory T Cells With an MHC-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor. Am. J. Transpl. 2017;17:917–930. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boardman D.A., Philippeos C., Fruhwirth G.O., Ibrahim M.a.A., Hannen R.F., Cooper D., Marelli-Berg F.M., Watt F.M., Lechler R.I., Maher J., et al. Expression of a Chimeric Antigen Receptor Specific for Donor HLA Class I Enhances the Potency of Human Regulatory T Cells in Preventing Human Skin Transplant Rejection. Am. J. Transpl. 2017;17:931–943. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Micklethwaite K.P., Gowrishankar K., Gloss B.S., Li Z., Street J.A., Moezzi L., Mach M.A., Sutrave G., Clancy L.E., Bishop D.C., et al. Investigation of product-derived lymphoma following infusion of piggyBac-modified CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Blood. 2021;138:1391–1405. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021010858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bishop D.C., Clancy L.E., Simms R., Burgess J., Mathew G., Moezzi L., Street J.A., Sutrave G., Atkins E., McGuire H.M., et al. Development of CAR T-cell lymphoma in 2 of 10 patients effectively treated with piggyBac-modified CD19 CAR T cells. Blood. 2021;138:1504–1509. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021010813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson M.H., Gottschalk S. Expect the unexpected: piggyBac and lymphoma. Blood. 2021;138:1379–1380. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021012349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roth T.L., Puig-Saus C., Yu R., Shifrut E., Carnevale J., Li P.J., Hiatt J., Saco J., Krystofinski P., Li H., et al. Reprogramming human T cell function and specificity with non-viral genome targeting. Nature. 2018;559:405–409. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0326-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller Y.D., Ferreira L.M.R., Ronin E., Ho P., Nguyen V., Faleo G., Zhou Y., Lee K., Leung K.K., Skartsis N., et al. Precision Engineering of an Anti-HLA-A2 Chimeric Antigen Receptor in Regulatory T Cells for Transplant Immune Tolerance. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:686439. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.686439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schober K., Müller T.R., Gökmen F., Grassmann S., Effenberger M., Poltorak M., Stemberger C., Schumann K., Roth T.L., Marson A., Busch D.H. Orthotopic replacement of T-cell receptor α- and β-chains with preservation of near-physiological T-cell function. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019;3:974–984. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0409-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kath J., Du W., Pruene A., Braun T., Thommandru B., Turk R., Sturgeon M.L., Kurgan G.L., Amini L., Stein M., et al. Pharmacological interventions enhance virus-free generation of TRAC-replaced CAR T cells. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2022;25:311–330. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2022.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacLeod D.T., Antony J., Martin A.J., Moser R.J., Hekele A., Wetzel K.J., Brown A.E., Triggiano M.A., Hux J.A., Pham C.D., et al. Integration of a CD19 CAR into the TCR Alpha Chain Locus Streamlines Production of Allogeneic Gene-Edited CAR T Cells. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:949–961. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eyquem J., Mansilla-Soto J., Giavridis T., van der Stegen S.J.C., Hamieh M., Cunanan K.M., Odak A., Gönen M., Sadelain M. Targeting a CAR to the TRAC locus with CRISPR/Cas9 enhances tumour rejection. Nature. 2017;543:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature21405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cochrane R.W., Robino R.A., Granger B., Allen E., Vaena S., Romeo M.J., de Cubas A.A., Berto S., Ferreira L.M.R. High affinity chimeric antigen receptor signaling induces an inflammatory program in human regulatory T cells. bioRxiv. 2024 doi: 10.1101/2024.03.31.587467. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watkins N.A., Brown C., Hurd C., Navarrete C., Ouwehand W.H. The isolation and characterisation of human monoclonal HLA-A2 antibodies from an immune V gene phage display library. Tissue Antigens. 2000;55:219–228. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2000.550305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wendering D.J., Amini L., Schlickeiser S., Farrera-Sal M., Schulenberg S., Peter L., Mai M., Vollmer T., Du W., Stein M., et al. Effector memory-type regulatory T cells display phenotypic and functional instability. Sci. Adv. 2024;10 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adn3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Battaglia M., Stabilini A., Migliavacca B., Horejs-Hoeck J., Kaupper T., Roncarolo M.-G. Rapamycin promotes expansion of functional CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells of both healthy subjects and type 1 diabetic patients. J. Immunol. 2006;177:8338–8347. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen D.N., Roth T.L., Li P.J., Chen P.A., Apathy R., Mamedov M.R., Vo L.T., Tobin V.R., Goodman D., Shifrut E., et al. Polymer-stabilized Cas9 nanoparticles and modified repair templates increase genome editing efficiency. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:44–49. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0325-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baeuerle P.A., Ding J., Patel E., Thorausch N., Horton H., Gierut J., Scarfo I., Choudhary R., Kiner O., Krishnamurthy J., et al. Synthetic TRuC receptors engaging the complete T cell receptor for potent anti-tumor response. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2087. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10097-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L., Zuris J.A., Viswanathan R., Edelstein J.N., Turk R., Thommandru B., Rube H.T., Glenn S.E., Collingwood M.A., Bode N.M., et al. AsCas12a ultra nuclease facilitates the rapid generation of therapeutic cell medicines. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:3908. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24017-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wienert B., Cromer M.K. CRISPR nuclease off-target activity and mitigation strategies. Front Genome. 2022;4 doi: 10.3389/fgeed.2022.1050507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turchiano G., Andrieux G., Klermund J., Blattner G., Pennucci V., El Gaz M., Monaco G., Poddar S., Mussolino C., Cornu T.I., et al. Quantitative evaluation of chromosomal rearrangements in gene-edited human stem cells by CAST-Seq. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28:1136–1147.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levine A.G., Arvey A., Jin W., Rudensky A.Y. Continuous requirement for the TCR in regulatory T cell function. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:1070–1078. doi: 10.1038/ni.3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henschel P., Landwehr-Kenzel S., Engels N., Schienke A., Kremer J., Riet T., Redel N., Iordanidis K., Saetzler V., John K., et al. Supraphysiological FOXP3 expression in human CAR-Tregs results in improved stability, efficacy, and safety of CAR-Treg products for clinical application. J. Autoimmun. 2023;138 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2023.103057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Issa F., Hester J., Goto R., Nadig S.N., Goodacre T.E., Wood K. Ex vivo-expanded human regulatory T cells prevent the rejection of skin allografts in a humanized mouse model. Transplantation. 2010;90:1321–1327. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ff8772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shy B.R., Vykunta V.S., Ha A., Talbot A., Roth T.L., Nguyen D.N., Pfeifer W.G., Chen Y.Y., Blaeschke F., Shifrut E., et al. High-yield genome engineering in primary cells using a hybrid ssDNA repair template and small-molecule cocktails. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023;41:521–531. doi: 10.1038/s41587-022-01418-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kath J., Franke C., Drosdek V., Du W., Glaser V., Fuster-Garcia C., Stein M., Zittel T., Schulenberg S., Porter C.E., et al. Integration of ζ-deficient CARs into the CD3-zeta gene conveys potent cytotoxicity in T and NK cells. Blood. 2024;143:2599–2611. doi: 10.1182/blood.2023020973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tatiossian K.J., Clark R.D.E., Huang C., Thornton M.E., Grubbs B.H., Cannon P.M. Rational Selection of CRISPR-Cas9 Guide RNAs for Homology-Directed Genome Editing. Mol. Ther. 2021;29:1057–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zetsche B., Gootenberg J.S., Abudayyeh O.O., Slaymaker I.M., Makarova K.S., Essletzbichler P., Volz S.E., Joung J., van der Oost J., Regev A., et al. Cpf1 Is a Single RNA-Guided Endonuclease of a Class 2 CRISPR-Cas System. Cell. 2015;163:759–771. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strohkendl I., Saifuddin F.A., Rybarski J.R., Finkelstein I.J., Russell R. Kinetic Basis for DNA Target Specificity of CRISPR-Cas12a. Mol. Cell. 2018;71:816–824.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shu R., Hammett M., Evtimov V., Pupovac A., Nguyen N.-Y., Islam R., Zhuang J., Lee S., Kang T.-H., Lee K., et al. Engineering T cell receptor fusion proteins using nonviral CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing for cancer immunotherapy. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2023;8 doi: 10.1002/btm2.10571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manske K., Dreßler L., Fräßle S.P., Effenberger M., Tschulik C., Cletiu V., Benke E., Wagner M., Schober K., Müller T.R., et al. Miniaturized CAR knocked onto CD3ε extends TCR function with CAR specificity under control of endogenous TCR signaling cascade. J. Immunol. Methods. 2024;526 doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2024.113617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watanabe N., Mo F., McKenna M.K. Impact of Manufacturing Procedures on CAR T Cell Functionality. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.876339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ghassemi S., Nunez-Cruz S., O’Connor R.S., Fraietta J.A., Patel P.R., Scholler J., Barrett D.M., Lundh S.M., Davis M.M., Bedoya F., et al. Reducing Ex Vivo Culture Improves the Antileukemic Activity of Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018;6:1100–1109. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghassemi S., Durgin J.S., Nunez-Cruz S., Patel J., Leferovich J., Pinzone M., Shen F., Cummins K.D., Plesa G., Cantu V.A., et al. Rapid manufacturing of non-activated potent CAR T cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022;6:118–128. doi: 10.1038/s41551-021-00842-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dickinson M.J., Barba P., Jäger U., Shah N.N., Blaise D., Briones J., Shune L., Boissel N., Bondanza A., Mariconti L., et al. A Novel Autologous CAR-T Therapy, YTB323, with Preserved T-cell Stemness Shows Enhanced CAR T-cell Efficacy in Preclinical and Early Clinical Development. Cancer Discov. 2023;13:1982–1997. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-22-1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Odak A., Yuan H., Feucht J., Cantu V.A., Mansilla-Soto J., Kogel F., Eyquem J., Everett J., Bushman F.D., Leslie C.S., Sadelain M. Novel extragenic genomic safe harbors for precise therapeutic T cell engineering. Blood. 2023;141:2698–2712. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022018924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Allen A.G., Khan S.Q., Margulies C.M., Viswanathan R., Lele S., Blaha L., Scott S.N., Izzo K.M., Gerew A., Pattali R., et al. A highly efficient transgene knock-in technology in clinically relevant cell types. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024;42:458–469. doi: 10.1038/s41587-023-01779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burton J., Siller-Farfán J.A., Pettmann J., Salzer B., Kutuzov M., van der Merwe P.A., Dushek O. Inefficient exploitation of accessory receptors reduces the sensitivity of chimeric antigen receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2023;120 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2216352120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rana J., Perry D.J., Kumar S.R.P., Muñoz-Melero M., Saboungi R., Brusko T.M., Biswas M. CAR- and TRuC-redirected regulatory T cells differ in capacity to control adaptive immunity to FVIII. Mol. Ther. 2021;29:2660–2676. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosado-Sánchez I., Haque M., Salim K., Speck M., Fung V.C., Boardman D.A., Mojibian M., Raimondi G., Levings M.K. Tregs integrate native and CAR-mediated costimulatory signals for control of allograft rejection. JCI Insight. 2023;8 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.167215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]