Abstract

目的

骨质疏松症以骨量减低和骨组织微结构损坏为特征,常引发脆性骨折。骨密度低是导致骨折的关键危险因素。血清半胱氨酸蛋白酶抑制剂C(cystatin C,CysC)是肾小球滤过率的内源性标志物,与骨密度呈负相关,可能是骨质疏松症的潜在危险因素。本研究旨在通过队列分析和孟德尔随机化(Mendelian randomization,MR)分析相结合的方法,探究CysC与骨质疏松症和骨折在普通人群中的关联和潜在的致病机制。

方法

利用英国生物银行的大规模前瞻性队列数据和欧洲人群的全基因组关联分析(genome-wide association study,GWAS)汇总统计数据(严格设置排除标准:非白人种族、甲状腺疾病、胃肠功能障碍、肾脏疾病、类风湿性疾病、恶性肿瘤、慢性感染或炎症性疾病、糖尿病和高血压等特殊疾病人群,以及正在服用影响骨代谢药物者)。采用多变量线性回归、Logistic回归和Cox比例风险模型分析CysC与骨密度、骨质疏松症和骨折发生风险的关系。所有分析均采用3个递进模型调整混杂因素:3种不同模型进行分析:模型1调整人口学特征和生活方式因素,模型2在模型1基础上进一步调整肾功能,模型3在模型2基础上调整体力活动水平。通过限制性立方样条模型探究其非线性关系,并使用MR分析评估CysC与骨质疏松症及骨折之间的因果关联。

结果

多变量分析显示,在调整基本变量后(模型1),总研究参与者中CysC与估计骨密度(estimated bone mineral density,eBMD)不存在相关性,但是在经过性别分层的男性和女性中均呈显著负相关(均P<0.001)。在调整肾功能(模型2)和体力活动水平(模型3)后,总研究参与者中CysC与eBMD开始呈负相关(P<0.001)。此外,多变量Logistic回归均显示CysC浓度与骨质疏松风险呈显著正相关(P<0.01),这种关联在所有分析模型中均保持稳定。在所有人群和模型中,多变量Cox回归分析结果均显示Q4组的CysC与骨质疏松症发生风险均呈正相关(均P<0.001)。在总人群中,Q4组的CysC与骨折之间的正向关联仅在模型2和模型3中出现,风险比均为1.118(均P<0.001)。然而经过性别分层后,这种关联在男性中消失(P>0.05)。此外,限制性立方样条回归分析结果显示CysC与骨质疏松症和骨折的发病存在非线性关系(P<0.05)。通过筛选167个单核苷酸多态性(single nucleotide polymorphisms,SNPs)作为工具变量进行MR分析,结果显示CysC与骨质疏松症和骨折之间并不存在直接的因果关系(P≥0.05),这一发现与既往特殊人群研究结果存在差异。

结论

CysC水平升高与骨质疏松症和骨折风险增加具有显著相关性,这种关联在女性中表现更为明显。肾功能和体力活动水平可能是影响这种关联的重要因素。CysC与骨质疏松和骨折之间的关联可能的机制包括CysC升高导致维生素D和矿物质代谢异常,抑制骨形成;肾功能损伤加重炎症水平,影响骨吸收;或在骨质疏松症状态下,破骨细胞分化增加导致CysC水平升高。这些发现支持将CysC作为预测潜在骨质疏松症的生物学指标的可能性。

Keywords: 半胱氨酸蛋白酶抑制剂C, 骨质疏松症, 骨折, 孟德尔随机化分析, 前瞻性队列研究

Abstract

Objective

Osteoporosis is characterized by decreased bone mass and damaged bone microstructure, often leading to fragility fractures. Low bone mineral density is a key risk factor for fractures. Serum cystatin C (CysC), an endogenous marker of glomerular filtration rate, is negatively correlated with bone mineral density and may be a potential risk factor for osteoporosis. This study aims to investigate the association and potential pathogenic mechanisms between CysC and osteoporosis and fractures in the general population by combining cohort analysis and Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis.

Methods

Large-scale prospective cohort data from the UK Biobank and summary statistics from genome-wide association study (GWAS) in European populations were utilized, with strict exclusion criteria applied (excluding non-white individuals, those with thyroid diseases, gastrointestinal dysfunction, kidney diseases, rheumatoid diseases, malignant tumors, chronic infections or inflammatory diseases, diabetes, hypertension, and individuals taking medications that affect bone metabolism). Multivariable linear regression, logistic regression, and Cox proportional hazards models were used to analyze the relationship between CysC and bone mineral density, osteoporosis, and fracture risk. All analyses were performed using three sequential models to adjust for confounding factors: Model 1 adjusted for demographic characteristics and lifestyle factors; Model 2 further adjusted for renal function based on Model 1; and Model 3 further adjusted for physical activity based on Model 2. Restricted cubic spline models were used to explore non-linear relationships, and MR analysis was conducted to assess the causal associations between CysC and osteoporosis and fractures.

Results

Multivariate analysis showed that after adjusting for basic variables (Model 1), there was no correlation between CysC and estimated bone mineral density (eBMD) in the overall study population; however, when stratified by gender, both males and females exhibited a significant negative correlation (P<0.001). After further adjustment for renal function (Model 2) and physical activity level (Model 3), CysC became negatively correlated with eBMD in the overall population (P<0.001). Moreover, multivariable logistic regression consistently demonstrated that CysC concentration was significantly positively associated with osteoporosis risk (P<0.01), and this association remained stable across all models. In all populations and models, multivariate Cox regression analysis indicated that subjects in the highest quartile (Q4) of CysC had a significantly increased risk of developing osteoporosis (P<0.001). In the overall population, the positive association between Q4 CysC levels and fractures was observed only in Models 2 and 3, with a hazard ratio of 1.118 (both P<0.001); however, after gender stratification, this association disappeared in males (P>0.05). Additionally, restricted cubic spline regression analyses revealed a significant non-linear relationship between CysC and the incidence of osteoporosis and fractures (P<0.05). MR analysis, using 167 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as instrumental variables, showed no direct causal relationship between CysC and osteoporosis or fractures (P≥0.05), a finding that differs from previous studies in special populations.

Conclusion

Elevated levels of CysC are significantly associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis and fractures, and this association is more pronounced in females. Renal function and physical activity levels may be important factors influencing this relationship. The link between CysC and osteoporosis and fractures may be mediated by several mechanisms: Eelevated CysC may lead to abnormalities in vitamin D and mineral metabolism, thereby inhibiting bone formation; renal dysfunction may exacerbate inflammation, affecting bone resorption; or in the osteoporosis state, increased osteoclast differentiation may result in elevated CysC levels. These findings support the potential use of CysC as a biomarker for predicting the risk of osteoporosis.

Keywords: cystatin C; osteoporosis, fractures; mendelian randomization analysis; prospective cohort study

随着中国人口老龄化的日益严峻,男性和女性的骨质疏松症发病率已分别攀升至6.46%和29.13%[1]。骨质疏松症是以骨量减低、骨组织微结构损坏为主要特征的全身性骨病,常并发脆性骨折[2]。最近一项通过全基因组分析评估骨折临床风险决定因素的大规模研究[3]表明,骨密度对骨折具有重大影响,骨密度低是导致骨折的关键危险因素。因此,探究与骨密度相关的危险因素对于骨质疏松症的早期诊断和治疗及预防骨折不良结局具有重要意义。

血清半胱氨酸蛋白酶抑制剂C(cystatin C,CysC)作为肾小球滤过率的内源性标志物,被发现与骨密度呈负相关[4-5],是骨质疏松症的潜在危险因素。但相关研究大多在2型糖尿病或慢性肾脏病患者等特殊人群中进行,普通人群中的CysC与骨密度之间的相关性和因果关系尚缺乏研究。本研究利用英国生物银行的普通人群队列数据和欧洲人群的全基因组关联研究汇总统计数据,采用队列分析和孟德尔随机化(Mendelian randomization,MR)分析结合的方法探究CysC与骨质疏松症和骨折在普通人群中的关联和潜在致病机制,评估CysC用于诊断骨质疏松症的可靠性。

1. 资料与方法

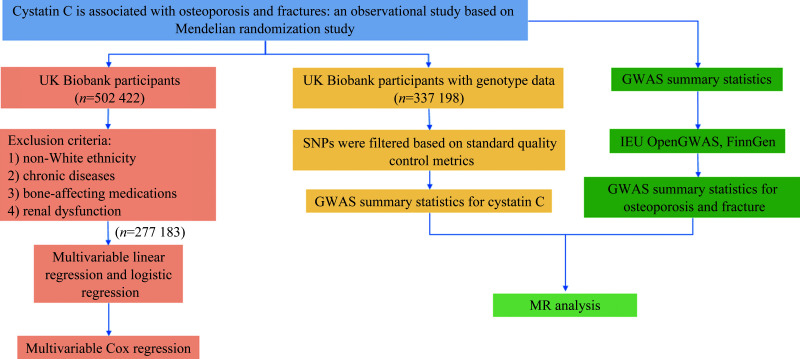

本研究采用前瞻性队列与MR相结合的研究方法,具体研究流程如图1所示。

图1.

研究设计流程图

Figure 1 Study design flowchart

UK Biobank: United Kingdom Biobank; SNPs: Single nucleotide polymorphisms; GWAS: Genome-wide association study; IEU-openGWAS: MRC integrative epidemiology unit open GWAS database; FinnGen: Finnish genomics biobank; MR: Mendelian randomization.

1.1. 数据来源与筛选

1.1.1. 队列数据

前瞻性队列数据来源于英国生物银行。该数据库于2006—2010年期间从英国22个评估中心招募了约502 422名研究参与者,获得了英国生物银行西北多中心研究伦理委员会的批准,并确保所有研究参与者均签署了书面知情同意书[6]。本研究已获得数据使用权限(11/NW/0382)。

为确保研究对象的准确性和一致性,本研究制定了暴露因素、结局指标及相关协变量的评估标准:1)使用《疾病和有关健康问题的国际统计分类》[7](The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision,ICD-10)作为疾病诊断标准;2)使用Siemens Advia 1800乳胶增强免疫比浊法测定血清CysC浓度[8];3)使用Sahara临床骨声压计(Hologic Corporation,Bedford,MA,USA)测量骨密度;4)根据国际体育活动问卷评估体力活动水平[9];5)由血清CysC计算估算肾小球滤过率(estimated glomerular filtration rate,eGFR),估算公式如下:eGFR[mL/(min·1.73 m2)]=186×Cycs-1.154×age-0.203×0.742(Female)[10]。

为了消除潜在的混杂因素,保持统计的稳健性,设定研究对象排除标准:1)非白人种族/民族;2)曾经被诊断为甲状腺疾病、胃肠功能障碍、肾脏疾病、类风湿性疾病、贫血、恶性肿瘤、慢性感染或炎症性疾病、糖尿病、高血压、骨质疏松症和骨折等疾病;3)正在服用影响骨代谢的药物(如类固醇和抗凝血剂);4)eGFR<60 mL/(min·1.73 m2);4)协变量数据不完整或无效。

按照以上标准进行排除后,共有277 183名研究参与者的数据被纳入横断面研究。

1.1.2. 全基因组关联分析汇总统计数据

血清CysC全基因组关联分析(genome-wide association study,GWAS)数据来源于英国生物银行的337 198名研究参与者,其中女性181 063名,男性156 135名。为了与观察性研究保持一致,采用与观察性研究相同的样本纳入和排除标准。最终有274 251名研究参与者被纳入GWAS分析,其中女性149 202名,男性125 049名。

采用GCTA fastGWA软件进行线性混合模型分析[9],假设存在加性等位基因效应,以测试常染色体遗传变异与表型之间的关系。基于HRC(Haplotype Reference Consortium)、UK10K和千人基因组参考面板,共获得约9 200万个变异。

为消除潜在的混杂因素,保持统计的稳健性,设置排除标准:1)最小等位基因频率(minor allele frequency,MAF)<1×10-2;2)估算信息得分(imputation information score,INFO)评分<0.8;3)哈迪-温伯格平衡检验P<1×10-12;4)缺失比例>5%的单核苷酸多态性(single nucleotide polymorphisms,SNPs)。最后,超900万个高质量SNPs最终被纳入分析。协变量年龄、性别、基因分型阵列、评估中心和前20个主成分作为固定效应被纳入。全基因组显著阈值为P<5×10-8。依据观察性研究的标准进行样本筛选(有效样本量为274 251),采用GCTA fastGWA软件规范性地构建数据[11]。

骨质疏松症和骨折的GWAS数据来源于芬兰基因生物银行(FinnGen Biobank),有效样本量分别为331 071和262 316。

1.2. 方法

1.2.1. 骨质疏松症和骨折的诊断与分组标准

骨质疏松症定义为基于估计骨密度(estimated bone mineral density,eBMD)的T评分≤-2.5[12]或在随访期间通过ICD-10诊断为骨质疏松的研究参与者;骨折包括随访期间通过ICD-10诊断为脊椎骨折、髋部骨折、前臂骨折及其他部位骨折的研究参与者。根据随访结果是否发生骨质疏松症和骨折,将所有研究对象分为发病组和未发病组。

1.2.2. 前瞻性队列分析

本研究首先采用多变量线性回归、Logistic回归分析CysC与eBMD、骨质疏松症和骨折发生风险的关系。其次,研究以队列基线时间为起点,通过追踪研究参与者的骨质疏松和骨折的诊断时间、失访时间、死亡时间和随访结束时间(2022年5月31日),构建生存资料。采用Cox比例风险模型对研究对象进行生存分析,并通过似然比检验、Wald检验和评分检验评估统计学意义。最后,为探索非线性关系,采用限制性立方样条模型拟合Cox比例风险模型,在第5、35、65和95百分位数处设置节点(Q1~Q4组),通过似然比检验评估非线性关系。

所有分析均采用3个递进模型调整混杂因素:模型1调整年龄、身高、体重、体重指数、评估中心、是否使用激素药物(仅限女性)、绝经状态(仅限女性)、吸烟状况、饮酒状况;模型2在模型1基础上调整eGFR;模型3在模型2基础上进一步调整体力活动水平。

1.2.3. 两样本MR分析

采用两样本MR方法评估CysC与骨质疏松及骨折的因果关联。主要分析采用逆方差加权法(inverse variance weighted method,IVW)、加权中位数回归和MR-Egger回归;使用Cochran Q统计量评估异质性;通过MR-Egger截距和MR-PRESSO全局检验评估工具变量的水平多效性;通过留一法敏感性分析确定具有潜在影响的单个SNP。全基因组显著阈值为P<5×10-8。

1.3. 统计学处理

连续性变量以均数±标准差表示,采用两独立样本t检验进行组间比较;分类变量以例数(%)表示,采用卡方检验进行组间比较。采用R软件(4.2.0版)中的“Two Sample MR”“survival”“MRPRESSO”“stats”“rms”“ggplot2”等软件包进行数据分析。 P<0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2. 结 果

2.1. 一般人口学资料

骨质疏松症发病组的年龄为(60.99±6.21)岁,女性占比为84.55%(表1)。骨折发病组的年龄为(57.52±7.96)岁,女性占比为62.84%(表2)。骨质疏松症和骨折发病组的eGFR和CysC均明显高于未发病组(均P<0.01),骨质疏松症和骨折发病组的体重指数和肌酐水平均低于未发病组(P<0.001,表1、2)。

表1.

研究对象骨质疏松症的基线数据比较

Table 1 Comparison of baseline data of osteoporosis between the study population

| 组别 | n | 年龄/岁 | 性别/[例(%)] | 饮酒水平/[例(%)] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 女 | 男 | 从不 | 少量 | 频繁 | |||

| 未发病组 | 270 006 | 55.36±8.11 | 144 801(53.63) | 125 205(46.37) | 7 637(2.83) | 8 062(2.99) | 254 307(94.18) |

| 发病组 | 7 177 | 60.99±6.21 | 6 068(84.55) | 1 109(15.45) | 411(5.73) | 370(5.16) | 6 396(89.11) |

| t/χ 2 | 69.33* | 2 080.90† | 359.95† | ||||

| P | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| 组别 | 随访时间/年 | eGFR/[mL/(min·1.73 m-2] | 吸烟情况/[例(%)] | 体重指数/(kg·m-2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 从不 | 已戒烟 | 目前仍然吸烟 | ||||

| 未发病组 | 13.32±1.39 | 93.48±16.05 | 151 639(56.16) | 90 525(33.53) | 27 842(10.31) | 26.48±4.46 |

| 发病组 | 8.45±4.62 | 94.10±18.01 | 3 840(53.50) | 2 544(35.45) | 793(11.05) | 25.45±4.62 |

| t/χ 2 | 80.06* | 22.74* | 205.85† | 28.72* | ||

| P | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| 组别 | 肌酐/(μmol·L-1) | CysC/(mg·L-1) | 身体活动水平/(MET·min·周-1) | eBMD/(g·cm-2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 未发病组 | 71.14±13.12 | 0.88±0.13 | 1 905.41±2 932.69 | 0.55±0.13 |

| 发病组 | 64.20±11.39 | 0.90±0.14 | 1 759.81±2 820.33 | 0.44±0.11 |

| t/χ 2 | 47.27* | 3.29* | 3.78* | 67.30* |

| P | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

计量资料以均数±标准差表示,计数资料以例数(%)表示。*t检验;†χ 2检验。eGFR:估算肾小球滤过率;CysC:半胱氨酸蛋白酶抑制剂C;MET:代谢当量;eBMD:估计骨密度。

表2.

研究对象骨折的基线数据比较

Table 2 Comparison of baseline data of fracture between the study population

| 组别 | n | 年龄/岁 | 性别/[例(%)] | 饮酒水平/[例(%)] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 女 | 男 | 从不 | 少量 | 频繁 | |||

| 未发病组 | 262 499 | 55.39±8.11 | 141 642(53.96) | 120 857(46.04) | 7 510(2.86) | 7 915(3.02) | 247 074(94.12) |

| 发病组 | 14 684 | 57.52±7.96 | 9 227(62.84) | 5 457(37.16) | 538(3.66) | 517(3.52) | 13 629(92.82) |

| t/χ 2 | 23.86* | 46.90† | 68.84† | ||||

| P | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| 组别 | 随访时间/年 | eGFR/[mL/(min·1.73 m-2] | 吸烟情况/[例(%)] | 体重指数/(kg·m-2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 从不 | 已戒烟 | 目前仍然吸烟 | ||||

| 未发病组 | 13.29±1.42 | 93.45±16.03 | 147 475(56.18) | 88 078(33.55) | 26 946(10.27) | 26.79±4.46 |

| 发病组 | 13.16±1.80 | 94.28±17.42 | 8 004(54.51) | 4 991(33.99) | 1 689(11.50) | 26.57±4.62 |

| t/χ 2 | 16.49* | 11.40* | 29.42† | 6.80* | ||

| P | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| 组别 | 肌酐/(μmol·L-1) | CysC/(mg·L-1) | 身体活动水平/(MET·min·周-1) | eBMD/(g·cm-2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 未发病组 | 71.09±13.13 | 0.88±0.13 | 1 895.59±2 918.61 | 0.55±0.13 |

| 发病组 | 68.62±12.88 | 0.89±0.14 | 2 009.83±3 123.36 | 0.50±0.13 |

| t/χ 2 | 14.84* | 3.00* | 9.30* | 46.10* |

| P | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

计量资料以均数±标准差表示,计数资料以例数(%)表示。*t检验;†χ 2检验。eGFR:估算肾小球滤过率;CysC:半胱氨酸蛋白酶抑制剂C;MET:代谢当量;eBMD:估计骨密度。

2.2. CysC对eBMD的影响

多变量线性回归分析结果显示,在调整基本变量后(模型1),总研究参与者中CysC与eBMD不存在相关性,但是在经过性别分层的男性和女性中均呈显著负相关(均P<0.001)。进一步调整eGFR(模型2)和体力活动水平(模型3)后,总研究参与者中CysC与eBMD呈负相关(P<0.001),男性和女性中的负相关也依然存在(均P<0.001,表3)。此外,多变量Logistic回归均显示CysC浓度与骨质疏松风险呈显著正相关(均P<0.01,表4)。

表3.

CysC与eBMD的线性回归分析

Table 3 Linear regression analysis between cystatin C and eBMD

| 组别 | 估计值(标准误) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 模型1 | 模型2 | 模型3 | |

| 总人群 | 0.001(0.002) | -0.018(0.003)*** | -0.018(0.024)*** |

| 男性 | -0.014(0.004)*** | -0.056(0.004)*** | -0.055(0.003)*** |

| 女性 | -0.019(0.003)*** | -0.046(0.003)*** | -0.046(0.003)*** |

模型1调整了年龄、身高、体重、体重指数、评估中心、是否使用了激素药物(仅限女性)、绝经状态(仅限女性)、吸烟状况、饮酒状况;模型2在模型1的基础上进一步调整了eGFR;模型3在模型2的基础上调整了体力活动水平。与未发病组比较,***P<0.001。

表4.

CysC与骨质疏松的Logistic回归分析

Table 4 Logistic regression analysis between cystain C and osteoporosis

| 组别 | 估计值(标准误) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 模型1 | 模型2 | 模型3 | |

| 总人群 | 0.012(0.002)*** | 0.026(0.002)*** | 0.026(0.002)*** |

| 男性 | 0.006(0.002)** | 0.023(0.002)*** | 0.023(0.002)*** |

| 女性 | 0.019(0.003)*** | 0.036(0.003)*** | 0.036(0.003)*** |

模型1调整了年龄、身高、体重、体重指数、评估中心、是否使用了激素药物(仅限女性)、绝经状态(仅限女性)、吸烟状况、饮酒状况;模型2在模型1的基础上进一步调整了eGFR;模型3在模型2的基础上进一步调整了体力活动。与未发病组比较,**P<0.01,***P<0.001。

2.3. CysC对骨质疏松症和骨折发生风险的纵向影响

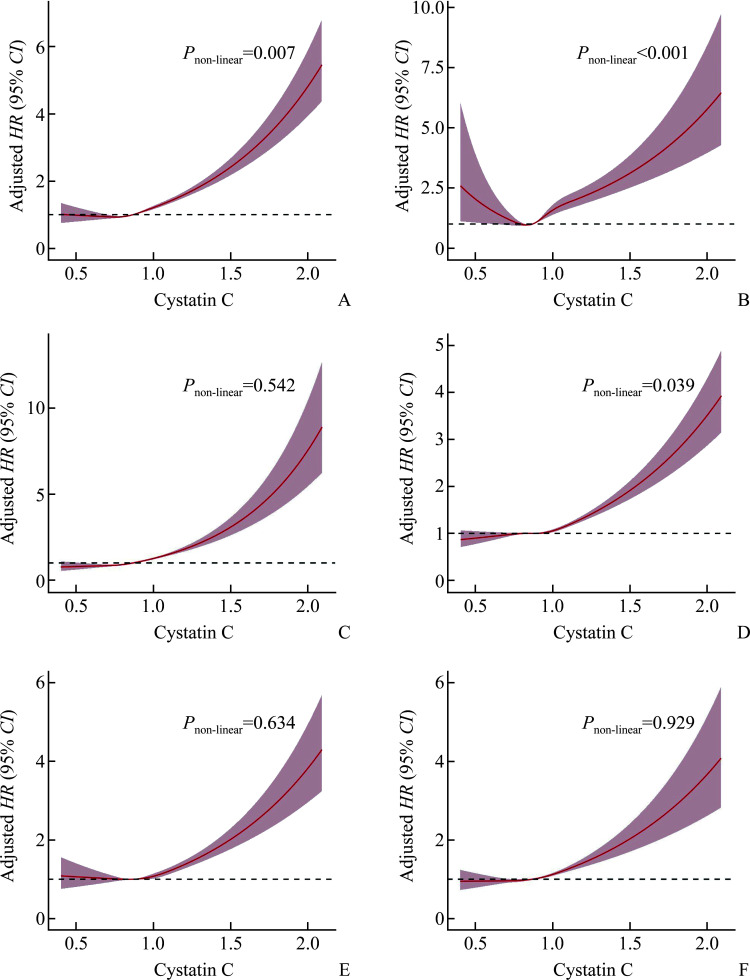

在所有人群和模型中,多变量Cox回归分析结果均显示Q4组的CysC与骨质疏松症发生风险均呈正相关(均P<0.001,表5)。在总人群中,Q4组的CysC与骨折之间的正向关联仅在模型2和模型3中出现,风险比均为1.118(均P<0.001,表5)。然而经过性别分层后,这种关联在男性中消失(P>0.05,表5)。此外,限制性立方样条回归分析结果显示CysC与骨质疏松症和骨折的发病存在非线性关系(P<0.05,图2)。此外,限制性立方样条回归分析结果显示,总人群中CysC与骨质疏松症(Pnon-linear=0.007,图2A)和骨折(Pnon-linear=0.039,图2D)的发病存在非线性关系,在男性亚组中仅与骨质疏松症发病存在非线性关系(Pnon-linear<0.001,图2B)。在男性骨折亚组(Pnon-linear=0.634,图2E)和女性亚组骨质疏松症(Pnon-linear=0.542,图2C)和骨折(Pnon-linear=0.929,图2F)中均未观察到显著的非线性关系。

表5.

CysC与骨质疏松症和骨折发生风险的Cox回归分析

Table 5 Cox regression analysis of cystain C and the risk of osteoporosis and fracture

| 组别 | 骨质疏松的风险比(95% CI) | 骨折的风险比(95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 模型1 | 模型2 | 模型3 | 模型1 | 模型2 | 模型3 | ||

| 总人群 | Q1 | 对照 | 对照 | 对照 | 对照 | 对照 | 对照 |

| Q2 | 0.955(0.892~1.023) | 1.030(0.961~1.104) | 1.030(0.961~1.104) | 0.956(0.911~1.002) | 1.001(0.951~1.050) | 1.000(0.953~1.049) | |

| Q3 | 0.984(0.917~1.055) | 1.120(1.043~1.204)** | 1.120(1.043~1.204)** | 0.937(0.892~0.984)** | 1.015(0.965~1.067) | 1.014(0.964~1.066) | |

| Q4 | 1.133(1.055~1.217)*** | 1.384(1.283~1.492)*** | 1.380(1.279~1.488)*** | 0.985(0.936~1.036) | 1.118(1.058~1.181)*** | 1.118(1.058~1.180)*** | |

| 男性 | Q1 | 对照 | 对照 | 对照 | 对照 | 对照 | 对照 |

| Q2 | 0.903(0.746~1.093) | 0.971(0.801~1.176) | 0.970(0.801~1.175) | 0.934(0.866~1.008) | 0.997(0.924~1.076) | 0.998(0.925~1.077) | |

| Q3 | 0.989(0.822~1.190) | 1.171(0.972~1.412) | 1.167(0.968~1.407) | 0.921(0.852~0.994)* | 1.028(0.950~1.112) | 1.030(0.952~1.114) | |

| Q4 | 1.387(1.164~1.653)*** | 1.807(1.511~2.161)*** | 1.791(1.491~2.142)*** | 0.970(0.896~1.051) | 1.151(1.059~1.251)*** | 1.155(1.063~1.256)*** | |

| 女性 | Q1 | 对照 | 对照 | 对照 | 对照 | 对照 | 对照 |

| Q2 | 0.978(0.902~1.061) | 1.070(0.986~1.162) | 1.069(0.985~1.161) | 0.957(0.899~1.019) | 1.008(0.946~1.074) | 1.009(0.947~1.074) | |

| Q3 | 1.008(0.931~1.092) | 1.178(1.085~1.279)*** | 1.177(1.084~1.277)*** | 0.948(0.891~1.010) | 1.036(0.970~1.106) | 1.036(0.971~1.106) | |

| Q4 | 1.190(1.098~1.290)*** | 1.519(1.394~1.655)** | 1.516(1.391~1.651)*** | 1.040(0.974~1.110) | 1.197(1.116~1.285)*** | 1.198(1.116~1.286)*** | |

模型1调整了年龄、身高、体重、体重指数、评估中心、是否使用了激素药物(仅限女性)、绝经状态(仅限女性)、吸烟状况、饮酒状况;模型2在模型1的基础上进一步调整了eGFR;模型3在模型2的基础上进一步调整了体力活动。与Q1组比较,*P<0.05,**P<0.01,***P<0.001。Q1~Q4组为按照CysC水平的百分位数分组,Q1组:低于第5百分位;Q2组:第5至35百分位;Q3组:第36至65百分位;Q4组:第66至95百分位。CI:置信区间;eGFR:估算肾小球滤过率。

图2.

CysC对骨质疏松症和骨折的发生风险具有非线性影响

Figure 2 Non-linear relationship between cystatin C and the incidence of fracture and osteoporosis

A: Association between CysC and risk of osteoporosis in the total population (P non-linear=0.007); B: Association between CysC and risk of osteoporosis in males (P non-linear<0.001); C: Association between CysC and risk of osteoporosis in females (P non-linear=0.542); D: Association between CysC and risk of fracture in the total population (P non-linear=0.039); E: Association between CysC and risk of fracture in males (P non-linear=0.634); F: Association between CysC and risk of fracture in females (P non-linear=0.929). The red solid line represents the adjusted HR, and the light red area represents the 95% confidence interval. The horizontal dashed line indicates the reference value (HR=1). CysC: Cystatin C; HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

2.4. CysC对骨质疏松症和骨折的因果关系

MR分析结果表明CysC与骨质疏松症和骨折之间均不存在因果关系(均P≥0.05,表6)。

表6.

CysC与骨质疏松症和骨折的因果关系

Table 6 Casual relationship of CysC with osteoporosis and fracture

| 暴露 | 结局 | 方法 | 估计值(95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CysC | 骨质疏松 | 逆方差加权 | -0.23(-1.12~0.67) | 0.66 |

| 加权中值 | -0.48(-1.89~0.92) | 0.50 | ||

| MR-Egger回归 | 0.34(-1.34~2.01) | 0.69 | ||

| 骨折 | 逆方差加权 | -0.36(-2.25~1.53) | 0.71 | |

| 加权中值 | 0.04(-3.10~3.19) | 0.98 | ||

| MR-Egger回归 | 0.43(-3.12~3.98) | 0.81 |

CysC:半胱氨酸蛋白酶抑制剂;MR:孟德尔随机化;CI:置信区间。

3. 讨 论

本研究基于英国生物银行创建了前瞻性队列和GWAS汇总统计数据,分析了普通人群中CysC与骨质疏松症和骨折发生风险之间的关系,结果显示CysC浓度的增加与骨质疏松症和骨折的发生风险增加有关,且这种关联在女性中更为明显,但MR分析未发现二者存在因果关联。

本研究观察到的CysC与骨代谢的性别差异值得深入探讨。通过研究跨性别人群的性激素治疗发现,雌激素治疗可降低CysC水平,而睾酮治疗则导致CysC水平升高[13],这种性激素介导的CysC水平变化可能是导致CysC与骨代谢关联存在性别差异的分子基础。基于健康中国绝经后妇女人群[14]、韩国人群[15]和社区动脉粥样硬化人群[16]的研究均支持了这一性别差异现象。然而,在男性人群中的研究结果仍存在争议。虽然本研究中男性组的关联较弱,但仍有研究[17]表明,CysC是男性髋部骨折的独立危险因素。最近的研究[18]发现,CysC家族通过调节雌激素受体表达和细胞内雌激素浓度影响骨代谢,这为理解CysC与骨代谢的关系提供了新的机制见解。值得注意的是,本研究的两样本MR分析结果表明普通人群中的CysC与骨质疏松症之间并不存在显著因果关联,这与既往基于慢性肾脏病遗传学联合会的研究[19]结果不同,提示需要在不同病理状态下深入研究CysC的作用机制。

CysC是肾脏功能的重要标志[20],并且已被证实通过多重途径参与骨代谢调节。在老年人中,即使是轻度的肾功能不全,也会出现钙、磷和维生素D代谢异常,可能引起肾脏形成1,25-二羟基维生素D的减少,导致钙吸收分数降低、骨吸收增高[21]。肾功能中度损伤与高水平的炎症因子有关,既往研究[22]表明高水平的CysC会导致同型半胱氨酸的堆积,增强氧化应激反应。这种炎症水平的增高会降低成骨细胞活性,并抑制破骨细胞凋亡,最终引发骨质疏松症[22-23]。在分子机制方面,CysC通过核因子κB受体活化因子(receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B,RANK)信号通路直接调控破骨细胞的形成[24]。基于现有证据,CysC与骨质疏松和骨折之间的关联可能存在以下几种可能性:1)CysC的升高标志着肾功能降低,出现维生素D和矿物质代谢异常,抑制骨形成;2)肾功能损伤加重炎症反应,影响骨细胞活性;3)在骨质疏松状态下,破骨细胞分化增加,影响CysC代谢。

本研究的主要优势在于英国生物银行是一项大样本的前瞻性队列研究,能够提供较全面的信息和足量的病例支撑本次的分析,使研究结果具有可信度。此外,基于观察性研究的结果,本研究还进行了MR分析,从遗传学的角度调查普通人群中CysC与骨质疏松症和骨折之间的潜在因果关联。然而,本研究仍然有几个局限性需要考虑。1)本研究以欧洲人群为研究对象,与亚洲人相比,生活环境、种族、饮食等存在固有差异,因此可能存在偏倚,影响结果在亚洲人群中的推广;2)本研究使用Sahara临床骨声压计来测量估计骨密度,而不是作为骨密度测量金标准的双能X射线吸收测定法,因此可能存在技术上的差别;3)尽管为了尽可能的排除混杂,本研究已经调整了大量协变量并设置了不同的模型组别,但由于研究无法做到包含所有的骨质疏松症和骨折的危险因素,所以不能完全排除未考虑到的混杂因素的影响;4)研究参与者可能会隐瞒或虚报他们的行为,比如吸烟史、饮酒史和体力活动持续时间和强度等,从而错误估计了这些行为对研究内容的影响;5)不同研究在研究对象的一般人口学数据和疾病相关数据方面的选取有所不同,这可能也是研究间结果差异的原因;6)尽管本研究在筛选普通人群时排除了特殊疾病患者,但由于英国生物样本库主要针对中老年人群,因此样本中可能依然包含一些潜在的退行性疾病影响因素。

本研究首次通过结合大样本队列研究和MR分析,发现CysC水平升高虽与骨质疏松和骨折风险增加显著相关(尤其在女性组),但二者并无直接因果联系。这一结果与既往研究结果存在差异,提示CysC与骨质疏松和骨折之间关联可能因人群特征而异。考虑到肾功能和体力活动水平的调节作用,CysC有望作为预测潜在骨质疏松症的生物学指标,但可能仍需在中国范围内开展大规模高质量的前瞻性研究,以便科学、合理地应用。

基金资助

国家自然科学基金(82103922)。This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation, China (82103922).

利益冲突声明

作者声称无任何利益冲突。

作者贡献

王文惠 论文构思、撰写与修改;王晗 论文撰写与数据分析;雷署丰 论文设计、指导与修改;何培 论文指导。所有作者阅读并同意最终的文本。

Footnotes

http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2024.240147

原文网址

http://xbyxb.csu.edu.cn/xbwk/fileup/PDF/2024101622.pdf

参考文献

- 1. Zeng Q, Li N, Wang Q, et al. The prevalence of osteoporosis in China, a nationwide, multicenter DXA survey[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2019, 34(10): 1789-1797. 10.1002/jbmr.3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen YJ, Jia LH, Han TH, et al. Osteoporosis treatment: current drugs and future developments[J]. Front Pharmacol, 2024, 15: 1456796. 10.3389/fphar.2024.1456796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Trajanoska K, Morris JA, Oei L, et al. Assessment of the genetic and clinical determinants of fracture risk: genome wide association and mendelian randomisation study[J]. BMJ, 2018, 362: k3225. 10.1136/bmj.k3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gao T, Liu FP, Ban B, et al. Association between the ratio of serum creatinine to cystatin C and bone mineral density in Chinese older adults patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus[J]. Front Nutr, 2022, 9: 1035853. 10.3389/fnut.2022.1035853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nishihira M, Matsuoka Y, Hori M, et al. Low skeletal muscle mass index is independently associated with low bone mineral density in kidney transplant recipients: a retrospective observational cohort study[J]. J Nephrol, 2024, 37(6): 1577-1587. 10.1007/s40620-024-01931-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age[J/OL]. PLoS Med, 2015, 12(3): e1001779[2024-01-23]. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goyal A, Gluckman TJ, Tcheng JE. What’s in a Name? the new ICD-10 (10th revision of the international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems) codes and type 2 myocardial infarction[J]. Circulation, 2017, 136(13): 1180-1182. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elliott P, Peakman TC, Biobank UK. The UK Biobank sample handling and storage protocol for the collection, processing and archiving of human blood and urine[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2008, 37(2): 234-244. 10.1093/ije/dym276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, et al. 2011 compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2011, 43(8): 1575-1581. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grubb A, Horio M, Hansson LO, et al. Generation of a new cystatin C-based estimating equation for glomerular filtration rate by use of 7 assays standardized to the international calibrator[J]. Clin Chem, 2014, 60(7): 974-986. 10.1373/clinchem.2013.220707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jiang LD, Zheng ZL, Qi T, et al. A resource-efficient tool for mixed model association analysis of large-scale data[J]. Nat Genet, 2019, 51(12): 1749-1755. 10.1038/s41588-019-0530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Francis RM, Peacock M, Barkworth SA. Renal impairment and its effects on calcium metabolism in elderly women[J]. Age Ageing, 1984, 13(1): 14-20. 10.1093/ageing/13.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Eeghen SA, Wiepjes CM, T’Sjoen G, et al. Cystatin C-based eGFR changes during gender-affirming hormone therapy in transgender individuals[J]. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2023, 18(12): 1545-1554. 10.2215/CJN.0000000000000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Han W, Bai XJ, Han LL, et al. Association between the age-related decline in renal function and lumbar spine bone mineral density in healthy Chinese postmenopausal women[J]. Menopause, 2018, 25(5): 538-545. 10.1097/GME.0000000000001039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yi DW, Khang AR, Lee HW, et al. Association between serum cystatin C and bone mineral density in Korean adults[J]. Ther Clin Risk Manag, 2017, 13: 1521-1528. 10.2147/TCRM.S147523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Daya N, Voskertchian A, Schneider ALC, et al. Kidney function and fracture risk: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study[J]. Am J Kidney Dis, 2016, 67(2): 218-226. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ensrud KE, Parimi N, Fink HA, et al. Estimated GFR and risk of hip fracture in older men: comparison of associations using cystatin C and creatinine[J]. Am J Kidney Dis, 2014, 63(1): 31-39. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gai D, Caviness PC, Lazarenko OP, et al. Cystatin M/E ameliorates bone resorption through increasing osteoclastic cell estrogen influx[J]. Res Sq, 2024: rs.3. rs-4313179. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-4313179/v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yuan J, Peng L, Luan F, et al. Causal effects of genetically predicted cystatin C on osteoporosis: a two-sample mendelian randomization study[J]. Front Genet, 2022, 13: 849206. 10.3389/fgene.2022.849206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stehlé T, Delanaye P. Which is the best glomerular filtration marker: Creatinine, cystatin C or both?[J/OL]. Eur J Clin Invest, 2024, 54(10): e14278[2024-01-23]. 10.1111/eci.14278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Suzuki K, Soeda K, Komaba H. Crosstalk between kidney and bone: insights from CKD-MBD[J]. J Bone Miner Metab, 2024, 42(4): 463-469. 10.1007/s00774-024-01528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. De Martinis M, Sirufo MM, Nocelli C, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia is associated with inflammation, bone resorption, vitamin B12 and folate deficiency and MTHFR C677T polymorphism in postmenopausal women with decreased bone mineral density[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020, 17(12): 4260. 10.3390/ijerph17124260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tang YC, Peng B, Liu JM, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: a cross-sectional study of the national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 2007-2018[J]. Front Immunol, 2022, 13: 975400. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.975400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Strålberg F, Kassem A, Kasprzykowski F, et al. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced osteoclast formation and bone resorption in vitro and in vivo by cysteine proteinase inhibitors[J]. J Leukoc Biol, 2017, 101(5): 1233-1243. 10.1189/jlb.3A1016-433R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]