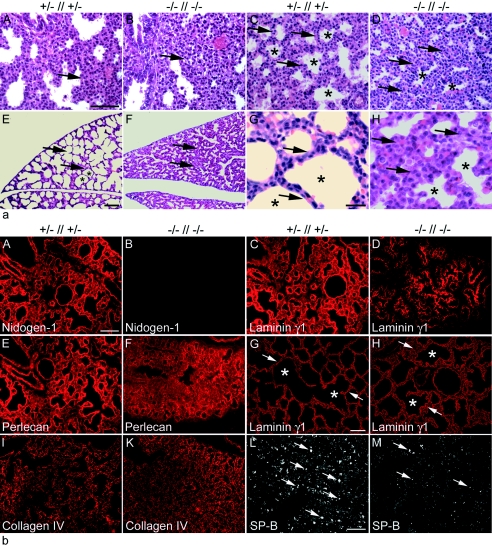

FIG. 4.

Histological analysis of lung tissue from embryos and neonates. (a) Hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained transverse sections of lungs from comparable regions at E17.5 (A and B), E18.5 (C and D), and P0 (E to H) are shown. Development of the lung tissue from the mutant (B and D) appears delayed compared to that of control littermates (A and C). At birth, neonatal lungs from control pups show typically dilated peripheral airway saccules (E and G), whereas nidogen-deficient lungs appear immature (F and H). Arrows, mesenchyme; asterisks, saccules. Bars, 50 μm (A to F) and 10 μm (G and H). (b) Immunofluorescence of lung sections from control (A, C, E, I, and L) and nidogen double-null (B, D, F, K, and M) embryos at E18.5 and (G and H) at P0. Rabbit antisera against the basement membrane components nidogen 1 (A and B), laminin γ1 (C, D, G, H), perlecan (E and F), collagen type IV (I and K), and SP-B (L and M) were used. Prominent deposition of all basement membrane proteins is detectable in control sections (A, C, E, G, I), whereas deposition appears less pronounced at E18.5 in sections from nidogen-deficient mutants (D, F, K). However, sections from lungs of mutant animals after birth showed a laminin staining of lung basement membranes comparable to that seen in control littermates (G and H). Immunostaining for SP-B appears significantly reduced in mutant (M) compared to control (L) lungs. (G and H) Arrows and asterisks mark terminal airways. Bars, 50 μm.