Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, remains a significant global health challenge, particularly in developing nations. Side effects and increasing drug resistance often limit conventional pharmaceutical treatments for TB. This has highlighted the urgent need for novel therapeutic agents. Traditional medicine offers a promising avenue for discovering effective and safer alternatives. In silico approaches play a crucial role in pharmaceutical research by facilitating the identification of novel therapeutic compounds. These techniques are widely employed to explore potential treatments for diverse diseases. This study aims to identify lead molecules with anti-tuberculosis potential that could be further studied for their inhibitory potential and possible optimization for the treatment of tuberculosis. Chlorophytum borivilianum and Asparagus racemosus were selected for their diverse phytochemical profiles and proven pharmacological activities, including significant antimicrobial properties that make them promising candidates for in silico exploration of anti-tuberculosis therapeutics. The drug-likeness and pharmacokinetics of phytochemicals from the plants were evaluated using Lipinski's rule of five, and ADMET predictions. Phytochemicals meeting these criteria were subjected to molecular docking against Mycobacterium tuberculosis targets: CYP51, InhA, and EthR, using Vina (PyRx)platform to calculate binding affinities and assess interaction stability. Molecular dynamics simulations (100 ns) were performed to validate the stability of the docked complexes, focusing on key parameters such as RMSD, RMSF, and Rg. This approach identified hecogenin, sarsasapogenin, and isoflavone as potential inhibitors of CYP51 with high binding affinities and stable interactions, suggesting their promise as lead compounds for tuberculosis treatment.

Keywords: Asparagus racemosus, Chlorophytum borivilianum, In silico studies, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Phytochemicals

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Tuberculosis is a global health challenge resulting in new drug discovery.

-

•

Insilico evaluated anti-TB potency of Chlorophytum & Asparagus phytochemicals.

-

•

Identified hecogenin, sarsasapogenin, and isoflavone as potential TB inhibitors.

-

•

Docking studies revealed strong binding affinities to CYP51, InhA & EthR targets.

-

•

Molecular dynamics study strongly supporting towards noble TB drug development.

1. Introduction

Tuberculosis, an ancient disease remains a global health challenge, claiming approximately 1.5 million lives in 2020 [1] and 1.25 million in 2023 (including 161 000 people with HIV). Worldwide [2]. This ancient disease persists as a major health, social, and economic burden, particularly affecting developing countries [3]. Caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis [4], TB is clinically classified into latent TB, where individuals test positive for the bacteria but exhibit no symptoms, and active TB, characterized by evident symptoms such as weight loss, fever, coughing, and blood-colored sputum [5,6]. Although pharmaceutical medications have been the primary approach to TB treatment, their effectiveness is hindered by various limitations, including side effects, drug resistance, and lengthy treatment regimens [7,8]. This poses significant challenges, especially in underdeveloped nations where treatment options are scarce and costly [9]. The critical necessity for the advancement of novel pharmacological treatments targeted at lowering the global prevalence of TB has significantly accelerated the research of traditional medicine as an alternative source for novel and effective therapeutic agents. Medicinal plants have proven to be a potential choice for the therapeutic treatment of various ailments, with significant antibacterial efficacy against a wide range of microorganisms due to their complex chemical constituents [10]. Plant-derived remedies have been successfully used to cure a variety of diseases throughout human history. Several studies have been carried out to find novel antibacterial components from sources that are natural. Numerous Indian medicinal herbs have reported to have high antibacterial action [11]. Some of these important plants include Chlorophytum borivilianum and Asparagus racemosus.

Chlorophytum borivilianum, commonly known as 'Safed Musli,' is a vital medicinal plant renowned for its various therapeutic applications. These include its efficacy as an anti-diabetic [12], anticancer [13], antiviral [14], and antimicrobial [15] agents. The bioactive substances found in medicinal plants, such as Safed Musli, are being actively explored for their potential as antibiotic agents in the development of new drugs [16]. Some of the major therapeutical phytochemical constituents of Chlorophytum borivilianum include Beta-sitosterol, mucilage, stigmasterol, chloromaloside A, chloromaloside B, and hecogenin [17].

Asparagus racemosus is one of the most important medicinal plants, it is widely distributed in subtropical and tropical regions such as India, Asia, Australia, and Africa, and has been extensively utilized in traditional medicine. It finds mention in the Indian and British Pharmacopoeias, as well as Indian traditional medicine (Ayurveda), for the treatment of various illnesses [18]. Recent studies highlighted its diverse therapeutic potential, including antibacterial, antiviral, antioxidant, anti-amnesic, hepatoprotective, and immunomodulatory activities [19]. Notably, methanolic and ethanolic root extracts of Asparagus racemosus have shown significant antibacterial activity against a range of pathogens, including Escherichia coli, Shigella dysenteriae, Vibrio cholerae, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Shigella sonnei, and Shigella flexneri. These findings suggest a promising avenue for utilizing Shatavari as a natural alternative to synthetic antibacterial drugs [20].

The therapeutic efficacy of Asparagus racemosus is attributed to its rich phytochemical composition, which includes important constituents such as Asparanin A [21], Asparoside C [22], Isoflavone also known as 3-Phenyl-4H-chromen-4-one [23], Racemoside A, Racemoside B, Racemoside C [24], Sarsasapogenin [25], Shatavarin IV [20], Shatavaroside A, and Shatavaroside B [26].

Chlorophytum borivilianum and Asparagus racemosus were selected for their extensive therapeutic potential and rich phytochemical composition, which align with the goals of discovering novel anti-tuberculosis agents. Chlorophytum borivilianum is renowned for its antimicrobial, antiviral, and immunomodulatory properties, supported by bioactive compounds like beta-sitosterol, chloromalosides, and hecogenin, which have demonstrated significant pharmacological activities. Similarly, Asparagus racemosus is widely recognized in traditional medicine systems for its antibacterial, antiviral, and immunomodulatory effects, attributed to constituents such as sarsasapogenin, shatavarin IV, and racemosides. These plants were chosen due to their historical use in treating infectious diseases and their potential for producing bioactive compounds with desirable drug-likeness and pharmacokinetics properties, making them ideal candidates for in silico studies targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Developing and clinically validating novel therapeutics can take many years [27]. In recent years, computational tools and advanced algorithms have been widely used to speed up and optimize the drug development process. Moreover, the advent of the bioinformatics era has seen a significant increase in the development of computational and web-based tools, offering accelerated avenues for novel drug design [28]. Using high-throughput approaches, these tools may quickly screen a wide range of compounds, accelerating the identification of novel therapeutics for emerging diseases and enabling rapid prediction of adverse drug reactions [29].

Computational approaches play a vital role in pharmaceutical research by facilitating the discovery and design of innovative molecules. Scientists worldwide leverage these methods to uncover new chemical entities with potential therapeutic applications for various diseases. This approach involves target identification and modeling, target validation, identifying compounds with therapeutic effects (such as medicinal plants phytochemicals) determination of the toxicity of the identified compound, and compound accessibility. These studies are used in preclinical investigations to aid in the drug development process. Computational techniques rely heavily on pharmacophore modeling, QSAR studies molecular docking, molecular dynamic simulation and virtual screening [30]. Using in silico analysis, this study evaluated the drug-likeness of phytoconstituents of chlorophytum borivilianum and Asparagus racemosus. It also determined the binding affinity of the selected compounds with Cytochrome P450 14 alpha-sterol demethylase (CYP51), enoyl-ACP reductase (InhA), and EthR of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to inhibit their activity and subsequently identify new lead molecules for the treatment of tuberculosis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Target protein

Cytochrome P450 14 alpha-sterol demethylase (CYP51) with X-RAY diffraction 2.21 Å of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv strain which was cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli [31]. enoyl-ACP reductase (InhA) with X-RAY diffraction 1.95 Å of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 [32] and Ethionamide Resistance Regulator (EthR) with X-RAY diffraction Resolution: 1.90 Å of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv also expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 [33] were selected as target proteins in this study, the 3D X-ray crystalline structure of the selected proteins were obtained from Protein database PDB (https://www.rcsb.org) with PDB code as 1EA1, 4TRN and 6ho0 respectively. Structures with X-ray diffraction resolutions below ∼1.7 Å reveal individual atoms and exhibit high resolution. Resolutions in the range of ∼1.7–2.2 Å are considered good, allowing for the clear visualization of many atoms [34]. The protein target structures used in this study fall within the X-ray diffraction range of 1.90–2.21 Å, which is regarded as ideal for molecular docking and other in silico studies. The sleeted target proteins were prepared by deleting water molecules, adding polar hydrogen atoms, and determination of binding active sites using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer software (https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download) [35].

2.2. Predicting binding sites

The active sites were determined using CASTp [36] and PDBSum [37]. For the CYP51, the binding site comprises the following amino acids: GLN A:72, TYR A:76, ARG A:95, ARG A:96, LYS A:97, HIS A:259, ARG A:326, HIS A:392, CYC A:394 and MET A:433. In the case of enoyl-ACP reductase (InhA) (PDB ID: 4TRN), the active site residues are identified as follows: GLY A:14, SER A:20, ILE A:21, ASP A:64, SER A:94, VAL A:65, ILE A:95, TRY A:158, GLY A:96, LYS A:165, PHE A:149, ILE A:194, TYR A:158, THR A:266. Furthermore, for the Ethionamide Resistance Regulator protein (EthR) (PDB ID: 6HO0) the active site amino acids include THR A:149 and ASN A:179.

2.3. Ligands compounds

Information about the anti-bacterial potential of Chlorophytum borivilianum and Asparagus racemosus plant constituents was obtained from various studies reported in the literature. Phytochemicals from selected for this study were downloaded from the database PubChem [38]. Hecogenin (PubChem ID: 91453), stigmasterol (PubChem ID: 5280794), chloromaloside A (PubChem ID: 151156), chloromaloside B (PubChem ID: 151155), Asparanin A (PubChem ID: 21575007), Asparoside C (PubChem ID: 158598), Racemoside A (PubChem ID: 102253062), Racemoside B (PubChem ID: 102253063), Racemoside C (PubChem ID: 102253064), Shatavarin IV (PubChem ID: 441896), Shatavaroside A (PubChem ID: 44203608), and Shatavaroside B (PubChem ID: 44203607). Isoflavone (PubChem ID: 72304) and Sarsasapogenin (PubChem ID: 92095). The structure of Triazole, Isoniazid, and Bedaquiline compounds were downloaded from PubChem with the code CID 67516, CID 3767, and CID 5388906 respectively.

2.4. Drug likeness properties and ADME analysis of the phytochemicals

Using the Canonical SMILES of selected phytochemicals, the pharmacokinetics properties of these compounds were evaluated via the pkcsm server (https://structure.bioc.cam.ac.uk/pkcsm) [39]. The evaluation was grounded on Lipinski's rule of five principles, which encompassed criteria such as molecular weight less than or equals to 500 Da, hydrogen bond donors less than or equals to 5, hydrogen bond acceptors less than or equals to 10, and Log P less than or equals to 5 [40]. Phytochemicals that complied with all of Lipinski's rules underwent further analysis. Their respective SMILES retrieved from PubChem and subsequently used to determine their pharmacokinetic including absorption, distribution, metabolism, toxicity and excretion using the same web server (pkcsm). This comprehensive evaluation aimed to provide insights into the potential bioavailability, metabolic fate, and safety profiles of the examined phytochemicals, thereby offering valuable information for their prospective therapeutic applications.

2.5. Molecular docking

The PyRx software [41], integrating Autodock Vina, Open Babel and AutoDock tools, facilitated the preparation of the selected proteins and subsequent molecular docking with the with CYP51, InhA and EthR structures were fully prepared, minimized, and then converted to pdbqt file format. The selected ligands went through similar optimization process, involving minimization using uff forcefield and optimization applying the algorithm of steepest Descent algorithm and subsequent conversion to pdbqt file format, ensuring the compatibility for molecular docking with Vina of suite of PyRx. For the docking simulations, the grid box parameters were meticulously set. For CYP51 1EA1, the center points were X: 17.3499193211, Y: 4.00449736014, and Z: 67.7524960648, with the dimensions of X: 35.5874386422, Y: 27.3019947203, and Z: 35.6185921295. Similarly, InhA 4TRN, the center points were X: 7.43961236071, Y: 36.6306380318, and Z: 18.1063, with the dimensions of X: 33.0140247214, Y: 34.6121944219, and Z: 25.0. For EthR 6ho0, the center points were X: 12.2269179061, Y: 25.037222536, and Z: 1.22971238596, with the dimensions of X: 17.9937429848, Y: 17.5995083687, and Z: 26.8498247719. The exhaustiveness option, which defines the extent for the search, was selected as 8. The best docked complex conformation was chosen by considering the lowest docking score (in kcal/mol) and lowest RMSD value (Root Mean Square Deviation). Following docking, BIOVIA Discovery Studio was used to visualize the bonding connections between the complex complexes of protein-ligand and assess their docking postures.

2.5.1. Docking score validation

To validate the docking results, the Webina 1.0.2 server was used adopting the same docking parameters [42].

2.5.2. Molecular dynamics

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation study was performed using GROMACS to understand the changes in conformation in the chosen docked complexes over time and the mechanism of interaction of the phytochemicals (ligands) with the target protein [43]. The CHARMM36 force field (charmm36-jul2022) and SPC water model were utilized for the dynamic investigations [44]. Topologies for the target protein were generated utilizing the pdb2gmx tool integrated within GROMACS, whereas the ligand (phytochemical) topologies were derived using the web-based SwissParam platform (http://www.swissparam.ch) [45]. For the preparation of the system for molecular dynamic simulations, the selected complexes were all centered in rhombic dodecahedron box with a box-system distance of 1.0 nm, all of the systems were solvated by applying the water model SPC [46]. The Charge neutralization process was achieved, the systems were relaxed via the algorithm of steepest descent for energy minimization calculations at 1000 kJ/(mol.nm) tolerance value. Subsequently, equilibration was conducted with position restraints applied to the ligand and protein molecules for 0.1 ns, employing NVT and NPT ensembles to uphold system pressure (1 atm) and temperature (300 K). Molecular dynamics simulations were then performed for 100 ns, encompassing 50000000 steps. Analysis of MD trajectories involved the computation of parameters such as RMSD (root mean square deviation), RMSF (root mean square fluctuation), and Rg (radius of gyration). These analyses were executed using the g_rmsd, g_rg, and g_rmsf, functions [47].

3. Results and discussion

The selected plant-derived compounds represent a subset of bioactive phytochemicals from Chlorophytum borivilianum and Asparagus racemosus based on their documented antibacterial potential in the literature. These compounds were specifically chosen for their reported pharmacological activities and relevance to tuberculosis treatment. While they do not encompass the entire phytochemical diversity of the species, they serve as representative candidates for this study, focusing on their therapeutic potential against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Future studies could explore additional compounds to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the species' full pharmacological spectrum.

The choice of Cytochrome P450 14 alpha-sterol demethylase (CYP51), enoyl-ACP reductase (InhA), and Ethionamide Resistance Regulator (EthR) as targets was based on their critical roles in the survival and pathogenicity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

3.1. Analysis of drug-likeness of the phytochemicals

Comprehensive drug-likeness analysis becomes imperative for understanding ligand behavior within biological systems. It's important to acknowledge that Lipinski's Rule might not universally apply to all compound types. Natural products, including plant-derived compounds, often demonstrate unique pharmacological properties that may not align strictly with conventional drug design principles. Despite not meeting Lipinski's criteria, plant phytochemicals can possess therapeutic efficacy. Performing drug-likeness and ADME analysis is justified because it provides valuable insights into their pharmacokinetic properties, helps optimize their therapeutic potential, and guides the development of novel drug candidates. In this study phytochemicals with drug-likeness properties were selected for further analysis to identify potential lead molecules, The drug-likeness of the selected phytochemicals was assessed using Lipinski's Rule of Five, which employs specific physicochemical criteria to filter compounds. phytochemicals failing to meet one or more than one parameter were exempted from further analysis, leaving only the compliant phytochemicals for subsequent molecular docking studies. Among the chosen phytochemicals, Asparanin A, Asparoside C, Racemoside A, Racemoside B, Racemoside C, Shatavarin IV, Shatavaroside A, and Shatavaroside B, Chloromaloside A, Chloromaloside B violated three of Lipinski's rules. These phytochemicals have molecular weight >500 Da, possessing >5 hydrogen bond donors, and having >10 hydrogen bond acceptors, as a result of violating three of Lipinski's rules, moreover, Stigmasterol violated one Lipinski's rule by having Log P value greater than 5. These compounds were consequently excluded from further analysis. Conversely, Isoflavone, hecogenin and Sarsasapogenin phytochemicals were found to adhere to all of Lipinski's rules (see Table 1), indicating favorable drug-likeness properties. Consequently, they were selected for further analysis.

Table 1.

Illustrating the molecular properties of selected phytochemicals.

| Phytochemicals | Molecular weight g/mol | Calculated Lipophilicity (LogP) | Number of Hydrogen Bond donors (nHBD) | Number of Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (nHBA) | Violations of Lipinski's Rule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asparanin A | 740.93 | 1.44 | 7 | 13 | 3 |

| Asparoside C | 1213.368 | −3.81 | 15 | 27 | 3 |

| Isoflavone | 222.243 | 3.46 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Racemoside A | 1049.211 | −1.88 | 12 | 22 | 3 |

| Racemoside B | 887.07 | 0.294 | 9 | 17 | 3 |

| Racemoside C | 871.071 | 1.3216 | 8 | 16 | 3 |

| Sarsasapogenin | 416.646 | 5.7938 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Shatavarin IV | 887.07 | 0.294 | 9 | 17 | 3 |

| Shatavaroside A | 857.044 | 0.9331 | 8 | 16 | 3 |

| Shatavaroside B | 1019.185 | −1.2427 | 11 | 21 | 3 |

| Stigmasterol | 412.702 | 7.8008 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Chloromaloside A | 1049.167 | −3.0913 | 12 | 23 | 3 |

| Chloromaloside B | 1243.35 | −5.6586 | 16 | 29 | 3 |

| Hecogenin | 430.629 | 4.9728 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

3.2. ADME analysis of the phytochemicals

Plant phytoconstituents remain promising subjects for therapeutic investigation, Drug likeness profiling and molecular docking have proven effective in identifying potentially active molecules within phytochemicals, paving new avenues for drug development [48] comprehensive drug-likeness analysis becomes imperative for understanding ligand behavior within biological systems. Isoflavone, hecogenin, and Sarsasapogenin adhered to Lipinski's rules and subsequently underwent ADME analysis utilizing the pKCSN server [39], as outlined in Table 2. Absorption studies emphasize the intestine as primary site for drug absorption from oral administration. In this investigation, Isoflavone, hecogenin, and Sarsasapogenin exhibited promising intestinal absorption rates, with predictions showing uniformly high values of 96.388 %, 97.596 %, and 95.856 %, respectively. Exploring the distribution profiles within the human body, particular attention was paid to predicting the VDss (volume of distribution at steady state). Notably, VDss values that are below −0.15 log L/kg indicate a high distribution, while values that are above 0.45 log L/kg suggest a low level of distribution. Isoflavone, hecogenin, and Sarsasapogenin respectively demonstrated the VDss level of −0.037, 0.716, and 0.174 log L/kg, indicating a propensity for low level of distribution in the organs and tissues, with expected higher level of concentration in the bloodstream. This highlights the diverse pharmacokinetic properties of these phytochemicals inside a biological system. Metabolic profiling revealed distinctive patterns in all three compounds with predictions indicating metabolism primarily mediated by CYP3A4 (cytochrome P450 3A4). Additionally, Isoflavone was identified as an inhibitor of CYP2C19 and CYP1A2 enzymes. Assessment of excretion pharmacokinetics focused on Total Clearance, representing the overall rate of substance elimination from the body. Total clearance values were determined as 0.197, 0.27, and 0.322 log ml/min/kg for Isoflavone, hecogenin, and Sarsasapogenin, respectively. Regarding safety, the Ames test results suggested neither hepatotoxic effects nor mutagenic potential for Isoflavone, hecogenin, and Sarsasapogenin compounds. Finally, MRTD (Maximum Tolerated Dose) values, indicating the predicted highest safe dose of compounds, were determined. All three compounds (Isoflavone, hecogenin, and Sarsasapogenin) exhibited MRTD values below the cutoff of 0.477, indicating their suitability for administration at greater dosages without resulting to toxicity or side effects.

Table 2.

Presenting pharmacokinetic properties of Selected Chlorophytum borivilianum and Asparagus racemosus.

| Pharmacokinetics parameters | Ligands (Phytochemicals) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Isoflavone | Sarsasapogenin | Hecogenin | |

| the volume of distribution at steady state (human) (log L/kg) | −0.037 | 0.174 | 0.716 |

| Intestinal absorption (human) (%) | 96.388 | 95.856 | 97.596 |

| Metabolism | CYP3A4 substrate CYP1A2 inhibitor CYP2C19 inhibitor |

CYP3A4 substrate | CYP3A4 substrate |

| Excretion (log ml/min/kg) | 0.197 | 0.322 | 0.27 |

| Hepatotoxicity | NO | NO | NO |

| Max. tolerated dose (human) (log mg/kg/day) | 0.107 | −0.492 | −0.415 |

| AMES toxicity | NO | No | NO |

3.3. Molecular docking result analysis

Molecular docking is regarded as a revolutionary technique for drug development based on the interaction of ligands and receptors. The docking value and interaction are determined by algorithm-based computer programs, which speed up and reduce the cost of drug development. Three Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins were selected for determination of their inhibition by Chlorophytum borivilianum phytochemicals. These proteins are CYP51, InhA and EthR. CYP51 is an essential Mycobacterium tuberculosis enzyme essential for synthesis of sterols that are vital for bacterial cellular membrane formation that is also an essential organelle from the bacterial survival [49]. InhA plays a vital role in the biosynthesis pathway of mycolic acids; these are known as long fatty acids which are components of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell wall [50,51]. Inhibition of CYP51 and InhA will inhibit the growth and replication of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. 3-Nitropropanoic acid (3NP), a bioactive compound derived from fungi, has been reported to suppress the growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In this study, we reveal that 3NP effectively inhibits the 2-trans-enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase (InhA) enzyme of M. tuberculosis, with an IC50 of 71 μM [52].Hydroxychalcone from the plant Malabar nut was reported to possess potential activity against CYP51 [53] so also emodin phytochemical of R. emodi was predicted to be effective against CYP51 [54]. Inhibition of EthR activity will aide in the combating the bacterial ability to develop resistance to Ethanamide. An in silico study 5-(4-Ethyl-phenyl)-2-(1H-tetrazol-5-ylmethyl)-2H-tetrazole (C29) and 3-[3-(4-Fluorophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]-N-(2-methylphenyl) piperidine-1-carboxamide (C22) as effective therapeutic agents for Tuberculosis drug discovery [55]. The molecular docking analysis of the results revealed that Isoflavone, hecogenin, and Sarsasapogenin phytochemicals possess a high affinity to CYP51(1EA1) this was demonstrated in the high binding energy affinities of −8.0, −8.8, and −10.7 kcal/mol respectively (Table 3). Isoflavone formed strong hydrogen bond interaction with ARG A:96 and a pi-pi bond with TYR A:79 amino acid residues of CYP51(1EA1). fluconazole (TPF_A_470) was reported to bind with these amino acids (ARG A:96 and TYR A:79) it could be observed in the CYP51-fluconazole complex (PDB: 1EA1) [47] 4-phenyl imidazole (PIM_A_470) was reported to form interaction with TYR A:79 amino acid residue which is demonstrated in the CYP51- 4 phenyl imidazole (PDB: 1E9X) [56]. This indicates that Isoflavone is predicted to induce a similar antibacterial effect as fluconazole and 4-phenylimidazole as the result of binding and forming interaction with the same amino acids of CYP51 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Table 3.

Illustrating the binding energies of the selected ligands with CYP51, InhA and EthR target proteins.

| Target proteins | Ligands | Binding energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Cytochrome P450 14 alpha-sterol demethylase (CYP51), | Isoflavone | −8.0 |

| Hecogenin | −8.8 | |

| Sarsasapogenin | −10.7 | |

| Triazol | −3.8 | |

| enoyl-ACP reductase (InhA) | Isoflavone | −9.9 |

| Hecogenin | −8.3 | |

| Sarsasapogenin | −9.7 | |

| Isoniazid | −5.7 | |

| Ethionamide Resistance Regulator (EthR) | Isoflavone | −10.3 |

| Hecogenin | −2.6 | |

| Sarsasapogenin | −2.9 | |

| Bedaquiline | 6.6 |

The complex of Isoflavone with CYP51(1EA1) also formed a Pi-sulfur bond with MET A:79, pi-pi bonds with PHE A:255, PHE A:83, and PI-alkyl bonds with ALA A:256, LEU A:100, LEU A:321. These interactions could further strengthen and stabilize the complex (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Illustrate the binding of Isoflavone with Cytochrome P450 14 alpha-sterol demethylase (CYP51) 1EA1 (a) Illustrated the 2D structure of the complex (b) Illustrated the 3D structure of the complex.

The docking complex of Hecogenin- CYP51(1EA1) revealed the interaction of hecogenin with VAL A:395 via hydrogen bond interaction and, ALA A:256, LEU A:105, LEU A:152 via alkyl bond, PHE A:399 via pi-sigma bond and GLY A:369 via Carbon-hydrogen. However, none of these amino acids are residues reported to be involved in interaction with a known inhibitor, though it could possess a potential inhibitory effect (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Illustrate the binding of Hecogenin with Cytochrome P450 14 alpha-sterol demethylase (CYP51) 1EA1 (a) Illustrated the 2D structure of the complex (b) Illustrated the 3D structure of the complex.

Sarsasapogenin formed a hydrogen bond with TYR A:76 amino acid residue in CYP51(1EA1) this interaction with this amino was observed in CYP51 complexes with fluconazole and 4-phenyl imidazole as discussed above. Sarsasapogenin also formed an alkyl bond with CYS A:394 amino acid, a residue in the protein active site. These interactions indicate the potential CYP51 inhibitory effect. Moreover, other bonds formed in the Sarsasapogenin-CYP51complex include alkyl bonds with LEU A:105, LEU A:152, ALA A:256, pi-sigma bond with PHE A:399, and GLY A:396. These bonds could aid in strengthening the complex interaction (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Illustrate the binding of Sarsasapogenin with Cytochrome P450 14 alpha-sterol demethylase (CYP51) 1EA1 (a) Illustrated the 2D structure of the complex (b) Illustrated the 3D structure of the complex.

Isoflavone possesses a high-affinity feature toward InhA (4TRN) demonstrated in the docking result of the binding affinity of −9.9 kcal/mol. That is relatively higher compared to the reference antibiotic drug Isoniazid with a binding energy value of −5.7 kcal/mol. The interaction in the Isoflavone- InhA (4TRN) involved VAL A:65, and ILE:95 via pi-sigma bonds. Isoniazid binds with the same amino acid residues of InhA (4TRN) that are part of the active sites of the protein. Other amino acids involved in the Isoflavone- InhA (4TRN) include ILE A:16, VAL A:65 via pi-alkyl bonds, and PHE A:41 via pi-pi bonds. Isoflavone thus possesses the potential of asserting an inhibitory effect against InhA (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4.

Illustrate the binding of Isoflavone with Enoyl-ACP reductase (InhA) 4TRN (a) Illustrated the 2D structure of the complex (b) Illustrated the 3D structure of the complex.

Hecogenin-. InhA (4TRN) complex revealed the interaction of Hecogenin with TYR A:158 via pi-sigma and alkyl bonds, and PHE A:149 via alkyl bond, these are amino acids residues in the active site of InhA protein. Other amino acids involved in the interaction of the complex include MET A:199, PRO A: 19, and ILE A:16 through alkyl bonds. The binding affinity of Hecogenin toward InhA was predicted to be −8.3 kcal/mol suggesting high affinity to the protein (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

(a) 2D structure Illustrating the binding of Hecogenin with Enoyl-ACP reductase (InhA) 4TRN (b) 2D structure Illustrating the binding of Sarsasapogenin with Enoyl-ACP reductase (InhA) 4TRN

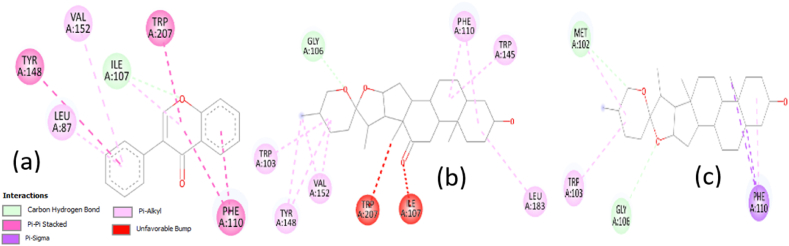

Sarsasapogenin formed an alkyl bond with PHE A:149 amino acid residues in the binding sites of the InhA (4TRN) protein. It also binds with MET A:199, ALA A:198, and LEU A:207 through alkyl bonds. Sarsasapogenin demonstrated a high binding affinity of −9.7 kcal/mol compared with isoniazid. Revealing a high affinity to InhA (4TRN) (Fig. 5b). Ethionamide Resistance Regulator (EthR) is my Mycobacterium tuberculosis regulatory protein that is responsible for the development of resistance against an anti-tuberculosis drug known as Ethionamide which is a prodrug that requires the bacterial EthA for its activation. After its activation, it inhibits mycolic acid synthesis. EthR regulates the expression of EthA thereby reducing its synthesis. Thus, Ethionamide could not be activated due unavailability of EthA [57] Inactivation of EthR would result in the expression of EthA and subsequently activation of Ethionamide drug and overcoming the resistance. It was found that the binding affinity between EthR (6ho0) and Isoflavone, Hecogenin, and Sarsasapogenin was −10.0, −2.6, and −2.9 kcal/mol, respectively. However, none of these ligands interacted with the amino acids present at the binding sites of the protein, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

(a) 2D structure Illustrating the binding of Isoflavone with Ethionamide Resistance Regulator (EthR) 6ho0 (b) 2D structure Illustrating the binding of Hecogenin with Ethionamide Resistance Regulator (EthR) 6ho0 (c) 2D structure Illustrating the binding of Sarsasapogenin with Ethionamide Resistance Regulator (EthR) 6ho0.

Isoflavone, hecogenin and Sarsasapogenin revealed significant affinities to enoyl-ACP reductase (InhA) so also Sarsasapogenin with EthR (6ho0). The molecular docking analysis demonstrated high affinities of Isoflavone and Sarsasapogenin to CYP51(1EA1), with binding affinities values of −8.0, and −10.7 kcal/mol respectively. Moreover, the formation of hydrogen words with amnio acids residues similarly reported to bind with fluconazole and 4-phenyl imidazole, suggests a potential antibacterial effect. Hecogenin formed a strong hydrogen bond with the CYP51 protein and exhibited high binding affinity with the protein. Thus, the interactions of CYP51 protein with the phytochemicals were chosen for further studies. The docked complexes of Isoflavone, Sarsasapogenin, and hecogenin with CYP51 were selected for molecular dynamic analysis to determine the stability and conformation changes of the complexes.

3.4. Molecular dynamics (MD) analysis

MD simulation serves as a computer-based methodology crucial for understanding the fluctuating behavior of intricate systems, in which molecules and atoms interact over time. Computational techniques significantly enhance drug discovery efforts. Importantly, MD simulations, unlike conventional molecular docking methods, account for target flexibility, thus enabling more accurate predictions of potential inhibitors [58]. Utilizing molecular dynamic studies, the stability, compactness, and dynamic behavior of CYP51-hecogenin, CYP51-sarsasapogenin, and CYP51-Isoflavone complexes were assessed through structural evaluations such as Root mean square deviation (RMSD), Radius of gyration (Rg) and Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF). The primary objective was to study and evaluate complex stability and elucidate the binding mechanisms of the selected phytochemicals with the CYP51 protein via MD simulations.

3.5. Root mean square deviation

The RMSD serves as a widely employed quantitative approach for evaluating and understanding the docked complexes' stability (protein-ligand complex), quantifying the perturbations in the structural integrity of the backbone of the protein throughout the simulation period [59]. Evaluating the RMSD of the protein backbone enabled the evaluation of stability for both the free protein and the complex of the protein with the ligand. The lower value of RMSD value compared to that of the RMSD value of the free protein signifies a stable complex [60]. RMSD was calculated using GROMACS rms. To investigate the stability of ligand (phytochemical) molecules with respect to the CYP51 protein, both ligand and backbone RMSDs were graphically measured. As depicted in Fig. 7, the protein backbone of CYP51 with all of the three selected phytochemicals exhibited consistent Stabilization during the course of the simulation, having values ranging from ∼0.11 to ∼0.28 nm. RMSD analysis of the CYP51-hecogenin complex throughout the simulation period exhibited consistently low values, remaining within the range of 0.25 nm. This falls well within the anticipated and stable range of 0.1–0.7 nm relative to the protein's size. Notably, a slight spike in RMSD occurred around 0.25ns, albeit within an acceptable margin, after which the RMSD remained below 0.25 nm until 100ns. Similarly, the RMSD analysis of CYP51 in the CYP51-sarsasapogenin complex also demonstrated minimal deviation, maintaining values within 0.3 nm. While there was a gradual increase in RMSD from 0ns to approximately 0.25ns, subsequent observations showed consistent maintenance around 0.3 nm until 100ns. Likewise, the CYP51-Isoflavone complex showcased notably low RMSD values, staying within 0.25 nm. Despite a gradual increase in RMSD from 0ns to approximately 15ns, the subsequent analysis revealed stable RMSD around 0.25 nm. Drawing from extensive analysis of the CYP51 backbone and phytochemicals RMSD plots, which revealed minimal fluctuations and negligible differences in values, it is foreseeable that the complexes remained stable throughout the simulation. Notably, the ligands' docked poses remained firmly entrenched within the active site, indicating their structural compatibility without inducing perturbations in the protein's stability.

Fig. 7.

Backbone root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the Cytochrome P450 14 alpha-sterol demethylase (CYP51) 1EA1 in complex with hecogenin, Sarsasapogenin and Isoflavone 100 ns of the molecular dynamics' simulation period.

3.6. Radius of gyration

A protein's compactness can be determined by measuring its radius of gyration (Rg), which helps to explain how proteins fold [61]. High Rg values demonstrate an untidy packing, while low Rg values reflect a tight nature of packing. While sudden changes in Rg values indicate protein folding instability, a relatively steady Rg over time shows that the ligands maintain the protein's folding behavior [62]. The primary objective of calculating Rg was to assess the system's compactness over time. GROMACS offers a built-in tool for evaluating protein compactness through the radius of gyration. A stable fold in a protein typically correlates with a consistent Rg value. Analysis of the graph (Fig. 8) illustrates that the radius of gyration remains relatively constant for the proteins in the CYP51-hecogenin, CYP51-sarsasapogenin, and CYP51-Isoflavone complexes throughout the simulation. This observation aligns with the RMSD findings. The analysis of Rg values confirms the stability of each system, indicating that the binding of the screened natural phytochemicals does not induce structural alterations during the entire simulation period.

Fig. 8.

Backbone radius of gyration of the Cytochrome P450 14 alpha-sterol demethylase (CYP51) 1EA1 in complex with hecogenin, Sarsasapogenin and Isoflavone during 100 ns of the molecular dynamics' simulation period.

3.7. Root mean square fluctuation

RMSF calculation was computed to ascertain the system's individual residue flexibility over the period of simulation. A high fluctuation score denotes unstable bonds and greater flexibility, whereas a low value denotes structured regions in the protein-ligand complexes [63]. RMSF evaluation was computed and mapped against the residues to determine the mobility of the residues in the presence and absence of the phytochemicals.

The RMSF analysis of alpha-carbon atoms across all systems is depicted in Fig. 9. Notably, the three complexes exhibited a consistent pattern of fluctuation throughout the entire structure during the simulation. The average RMSF values for the CYP51-hecogenin, CYP51-sarsasapogenin, and CYP51-Isoflavone complexes were approximately 0.091535123 nm, 0.096385831 nm, and 0.095382 nm, respectively. These values indicate relatively minor conformational fluctuations within the docking complexes, suggesting no significant structural changes in the protein. The stability depicted in the graph underscores the protein's ability to maintain its compactness throughout the simulation. Additionally, all phytochemicals were observed to remain within the binding pocket throughout the MD simulation.

Fig. 9.

Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of backbone atoms of the Cytochrome P450 14 alpha-sterol demethylase (CYP51) 1EA1 in complex with hecogenin, Sarsasapogenin and Isoflavone100 ns of the molecular dynamics' simulation period.

4. Conclusion

This study highlights the potential of plant phytochemicals targeting the CYP51 protein as a promising strategy for combating Mycobacterium tuberculosis, with identified phytochemicals showing encouraging results as potential drug candidates. Hecogenin from Chlorophytum borivilianum and sarsasapogenin, alongside isoflavone from Asparagus racemosus, were predicted as potent inhibitors of CYP51 based on docking simulations that revealed stable complexes, further validated by 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations. Additionally, these phytochemicals exhibited favorable drug-likeness according to Lipinski's rule of five and ADME criteria, indicating their suitability as drug candidates. Beyond CYP51, these compounds demonstrated significant binding affinities to enoyl-ACP reductase (InhA) and EthR, suggesting their broader therapeutic potential against tuberculosis. Further in vitro and in vivo studies are recommended to validate the inhibitory effects of the identified compounds. These findings offer a robust foundation for future research on the development of phytochemical-based therapeutics for tuberculosis treatment.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Munir Ibrahim: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Asmita Detroja: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology. Avani Bhimani: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology. Tirth Chetankumar Bhatt: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation. Jaykumar Koradiya: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. Gaurav Sanghvi: Investigation, Supervision, Validation. Ashok Kumar Bishoyi: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Consent to participate

Not applicable (No human and/or animal studies were taken)

Consent to publish

Not applicable (No human and/or animal studies were taken)

Ethical approval

Not applicable (No human and/or animal studies were taken)

Data availability statement

All the generated data were presented in this manuscript. Data will be provided upon request. No additional data were used for the research described in the article.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Science, Marwadi University for providing the necessary facilities for this investigation. We also thank Prof. (Dr.) Kantha D. Arunachalam, Dean, Faculty of Science, Marwadi University, for her encouragement and support in carrying out this investigation.

Contributor Information

Munir Ibrahim, Email: munir6632@yahoo.com.

Asmita Detroja, Email: asmitapatel34237@gmail.com.

Avani Bhimani, Email: avanibhimani2709@gmail.com.

Tirth Chetankumar Bhatt, Email: tbhatt512@gmail.com.

Jaykumar Koradiya, Email: jaykoradiya97@gmail.com.

Gaurav Sanghvi, Email: gv.sanghvi@gmail.com.

Ashok Kumar Bishoyi, Email: ashokbiotech4@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Fernandes G.F., Thompson A.M., Castagnolo D., Denny W.A., Dos Santos J.L. Tuberculosis drug discovery: challenges and new horizons. J. Med. Chem. 2022;65:7489–7531. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Tuberculosis fact sheet. 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis from.

- 3.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2013. Global tuberculosis report 2013.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/91355 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Natarajan A., Beena P.M., Devnikar A.V., Mali S. A systemic review on tuberculosis. Indian J Tuberc. 2020;67:295–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2020.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Namdar R., Peloquin C. In: Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. 11e. Tuberculosis, DiPiro J.T., Yee G.C., Posey L., Haines S.T., Nolin T.D., Ellingrod V., editors. McGrawHill; 2020. https://accesspharmacy.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2577§ionid=223398313 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rieder H.L., Chiang C.Y., Gie R., Enarson D., editors. Crofton's Clinical Tuberculosis. third ed. Macmillan; Oxford: Macmillan Education: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang K.C., Yew W.W. Management of difficult multidrug‐resistant tuberculosis and extensively drug‐resistant tuberculosis: update 2012. Respirol. 2013;18:8–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falzon D., Mirzayev F., Wares F., Baena I.G., Zignol M., Linh N.…Raviglione M. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis around the world: what progress has been made? Eur. Respir. J. 2015;45:150–160. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00101814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Widyarti S., Kamaruddin M., Aristyani S., Elvina M., Subagjo S., Rahayu T., Bambang Sumitro S. Bioinorganic chemistry and computational study of herbal medicine to treatment of tuberculosis. IntechOpen. 2020 doi: 10.5772/intechopen.90155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishra D.K., Shukla S. A review on herbal treatment of tuberculosis. Int Res J Pharm Med Sci. 2020;3:6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhat B.A., Mir W.R., Sheikh B.A., Rather M.A., Mir M.A. In vitro and in silico evaluation of antimicrobial properties of Delphinium cashmerianum L., a medicinal herb growing in Kashmir, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022;291 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panda S.K., Si S.C., Bhatnagar S.P. Studies on hypoglycaemic and analgesic activities of Chlorophytum borivilianum Sant & Ferz. J. Nat. Remedies. 2007;7:31–36. doi: 10.18311/jnr/2007/191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamal M.A. International Conference on Promotion and Development of Botanicals with International Co-ordination Exploring Quality, Safety, Efficacy and Regulation Organized by School of Natural Product Study. Jadavpur university; Kolkata, India: 2005. Effects of Safed musli on cell kinetics and apoptosis in human breast cancer cell lines; p. 26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siddiqui Y.M. Jadavpur university; Kolkata, India: 2005. Potent Antiviral Effect of Safed Musli on Poliovirus Replication, International Conference on Promotion and Development of Botanicals with International Co-ordination Exploring Quality, Safety, Efficacy and Regulation Organized by School of Natural Product Study; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deore S.L., Khadabadi S.S. In vitro antimicrobial studies of Chlorophytum borivilianum (liliaceae) root extracts. Asian J Microbiol Biotech Environ Sci. 2007;9:807–809. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J., Ye X., Yang X., et al. Discovery of novel antibiotics as covalent inhibitors of fatty acid synthesis. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020;15:1826–1834. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.9b00982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deore S.L., Khadabadi S.S. Isolation and characterization of phytoconstituents from Chlorophytum borivilianum. Pharmacognosy Res. 2010;2:343–349. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.75452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Acharya S.R., Acharya N.S., Bhangale J.O., Shah S.K., Pandya S.S. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective action of Asparagus racemosus Willd. root extracts. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2012;50:795–801. http://nopr.niscpr.res.in/handle/123456789/14940 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hussain A., Ahmad M.P., Wahab S., Hussain M.S., Ali M. A review on pharmacological and phytochemical profile of Asparagus racemosus Willd. Pharmacologyonline. 2011;3:1353–1364. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joshi J., Sukh Dev. Chemistry of Ayurvedic crude drugs: part VIII: Shatavari-2: structure elucidation of bioactive Shatavarin-I and other glycosides. Ind J Chem. 1988;27B:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayes P.Y., Jahidin A.H., Lehmann R., Penman K., Kitching W., De Voss J.J. Steroidal saponins from the roots of Asparagus racemosus. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:796–804. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chikhale R.V., Sinha S.K., Patil R.B., Prasad S.K., Shakya A., Gurav N.…Gurav S.S. In-silico investigation of phytochemicals from Asparagus racemosus as plausible antiviral agent in COVID-19. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021;39:5033–5047. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1784289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saxena V.K., Chourasia S. A new isoflavone from the roots of Asparagus racemosus. Fitoterapia. 2001;72:307–309. doi: 10.1016/S0367-326X(00)00315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandal D., Banerjee S., Mondal N.B., Chakravarty A.K., Sahu N.P. Steroidal saponins from the fruits of Asparagus racemosus. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:1316–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmad S., Ahmad S., Jain P.C. Chemical examination of Shatavari Asparagus racemosus. Bull Medico-Ethano Bot Res. 1991;12:157–160. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma U., Kumar N., Singh B., Munshi R.K., Bhalerao S. Immunomodulatory active steroidal saponins from Asparagus racemosus. Med. Chem. Res. 2013;22:573–579. doi: 10.1007/s00044-012-0048-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fons N. Focus: drug development: textbook of drug design and discovery, fifth edition. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2017:90–160. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wouters O.J., McKee M., Luyten J. Estimated research and development investment needed to bring a new medicine to market, 2009-2018. JAMA. 2020;323:844–853. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohanasundaram N., Sekhar T. Computational studies of molecular targets regarding the adverse effects of isoniazid drug for tuberculosis. Curr. Pharmacogenomics Personalized Med. (CPPM) 2018;16:210–218. doi: 10.2174/1875692116666181108145230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chowdhury R., Rashid R.B. Effect of the crude extracts of Amoora rohituka stem bark on gastrointestinal transit in mice. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2003;35(5):304–307. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellamine A., Mangla A.T., Nes W.D., Waterman M.R. Characterization and catalytic properties of the sterol 14α-demethylase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96(16):8937–8942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chollet A., Mourey L., Lherbet C., Delbot A., Julien S., Baltas M.…Bernardes-Génisson V. Crystal structure of the enoyl-ACP reductase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (InhA) in the apo-form and in complex with the active metabolite of isoniazid pre-formed by a biomimetic approach. J. Struct. Biol. 2015;190(3):328–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanina A., Wohlkönig A., Soror S.H., Flipo M., Villemagne B., Prevet H.…Wintjens R. A comprehensive analysis of the protein-ligand interactions in crystal structures of Mycobacterium tuberculosis EthR. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Proteins and Proteomics. 2019;1867(3):248–258. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erickson J.A., Jalaie M., Robertson D.H., Lewis R.A., Vieth M. Lessons in molecular recognition: the effects of ligand and protein flexibility on molecular docking accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47(1):45–55. doi: 10.1021/jm030209y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biovia D.S. Dassault Systèmes; San Diego: 2015. Materials Studio Modeling Environment. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian W., Chen C., Lei X., Zhao J., Liang J. CASTp 3.0: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W363–W367. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky473. doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laskowski R.A., Jabłońska J., Pravda L., Vařeková R.S., Thornton J.M. PDBsum: structural summaries of PDB entries. Protein Sci. 2018;27:129–134. doi: 10.1002/pro.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim S., Chen J., Cheng T., Gindulyte A., He J., He S.…Bolton E.E. PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D1373–D1380. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac956. 10.1093/nar/gkac956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pires D.E., Blundell T.L., Ascher D.B. pkCSM: predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:4066–4072. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipinski C.A. Drug-like properties and the causes of poor solubility and poor permeability. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 2000;44:235–249. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(00)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dallakyan S., Olson A.J. Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015;1263:243–250. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2269-7_19-DOI-PubMed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kochnev Y., Hellemann E., Cassidy K.C., Durrant J.D. Webina: an open-source library and web app that runs AutoDockVina entirely in the web browser. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:4513e5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pronk S., Pall S., Schulz R., Larsson P., Bjelkmar P., Apostolov R., Shirts M.R., Smith J.C., Kasson P.M., van der Spoel D., Hess B., Lindahl E. Gromacs 4.5: a high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2013;29:845–854. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang J., MacKerell A.D. CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: validation based on comparison to NMR data. J. Comput. Chem. 2013;34:2135–2145. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zoete V., Cuendet M.A., Grosdidier A., Michielin O. SwissParam: a fast force field generation tool for small organic molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32:2359–2368. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berendsen Herman JC., Postma James PM., Wilfred F., Gunsteren van, Hermans Jan. Intermolecular Forces: Proceedings of the fourteenth Jerusalem symposium on Quantum Chemistry and Biochemistry Held in Jerusalem. Springer Netherlands; Israel: 1981. Interaction models for water in relation to protein hydration; pp. 331–342. April 13–16, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abraham M., et al. vol. 2. Zenodo; 2024. (GROMACS 2024.2 Manual 2024). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ononamadu C., Ibrahim A. Molecular docking and prediction of ADME/drug-likeness properties of potentially active antidiabetic compounds isolated from aqueous-methanol extracts of Gymnema sylvestre and Combretum micranthum. Biotechnologia. 2021;102:85–99. doi: 10.5114/bta.2021.103765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lepesheva G.I., Waterman M.R. Sterol 14α-demethylase cytochrome P450 (CYP51), a P450 in all biological kingdoms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2007;1770:467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McNeil M., Daffe M., Brennan P.J. Location of the mycolyl ester substituents in the cell walls of mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:13217–13223. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)98826-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dubnau E., Chan J., Raynaud C., Mohan V.P., Laneelle M.A., Yu K., et al. Oxygenated mycolic acids are necessary for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;36:630–637. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Songsiriritthigul C., Hanwarinroj C., Pakamwong B., Srimanote P., Suttipanta N., Sureram S., Pungpo Inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis InhA by 3‐nitropropanoic acid. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 2022;90(3):898–904. doi: 10.1002/prot.26268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chakrapani I.S., Nellore A.P., Vatsa G., Kumar A., Pandian P.M., Priyadarsini A.I. Novel computational approaches for investigating bacterial inhibitors from malabar nut plant. Ann. For. Res. 2022;65(1):3224–3232. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rolta R., Salaria D., Kumar V., Patel C.N., Sourirajan A., Baumler D.J., Dev K. Molecular docking studies of phytocompounds of Rheum emodi Wall with proteins responsible for antibiotic resistance in bacterial and fungal pathogens: in silico approach to enhance the bio-availability of antibiotics. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022;40(8):3789–3803. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1850364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Halder S.K., Elma F. In silico identification of novel chemical compounds with antituberculosis activity for the inhibition of InhA and EthR proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2021;24 doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2021.100246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Podust L.M., Poulos T.L., Waterman M.R. Crystal structure of cytochrome P450 14α-sterol demethylase (CYP51) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis in complex with azole inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:3068–3073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061562898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DeBarber A.E., Mdluli K., Bosman M., Bekker L.G., Barry C.E. Ethionamide activation and sensitivity in multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:9677–9682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu X., Shi D., Zhou S., Liu H., Liu H., Yao X. Molecular dynamics simulations and novel drug discovery. Expet Opin. Drug Discov. 2018;13:23–37. doi: 10.1080/174604411403419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sargsyan K., Grauffel C., Lim C. How molecular size impacts RMSD applications in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2017;13:1518–1524. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu K., Watanabe E., Kokubo H. Exploring the stability of ligand binding modes to proteins by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2017;31:201–211. doi: 10.1007/s10822-016-0005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lobanov M.Y., Bogatyreva N.S., Galzitskaya O.V. Radius of gyration as an indicator of protein structure compactness. Mol. Biol. 2008;42:623–628. doi: 10.1134/S0026893308040195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khan R., Jha R.K., Amera G.M., Jain M., Singh E., Pathak A., Singh R.P., Muthukumaran J., Singh A.K. Targeting SARS-CoV-2: a systematic drug repurposing approach to identify promising inhibitors against 3C-like proteinase and 20 -O-ribose methyltransferase. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1753577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gajula M., Kumar A., Ijaq J. Protocol for molecular dynamics simulations of proteins. Bio-protocol. 2016;85:159–166. doi: 10.21769/bioprotoc.2051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the generated data were presented in this manuscript. Data will be provided upon request. No additional data were used for the research described in the article.