Abstract

Insomnia impairs daily functioning and increases health risks. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is effective but limited by cost and therapist availability. Fully automated digital CBT-I (FA dCBT-I) provides an accessible alternative without therapist involvement. This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the effectiveness of FA dCBT-I across 29 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 9475 participants. Compared to control groups, FA dCBT-I demonstrated moderate to large effects on insomnia severity. Subgroup analyses indicated that FA dCBT-I had a significant impact when contrasted with most control groups but was less effective than therapist-assisted CBT-I. Meta-regression revealed that control group type moderated outcomes, whereas completion rate did not. This implies that treatment adherence, rather than merely completing the intervention, is crucial for its effectiveness. This study supports the potential of FA dCBT-I as a promising option for managing insomnia but underscores that a hybrid model combining therapist support is more beneficial.

Subject terms: Diseases, Health care, Medical research

Introduction

The prevalence of insomnia varies from 5% to 50% depending on the definition and diagnostic criteria used in epidemiological studies1. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) and the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition (ICSD-3), insomnia disorder is characterized by difficulties in initiating, maintaining, or waking up early from sleep, resulting in impaired daytime functioning2,3. In DSM-5, insomnia disorder is diagnosed if sleep problems persist for at least 3 months and occur at least 3 days a week. The ICSD-3 distinguishes between short-term insomnia disorder, lasting less than 3 months, and chronic insomnia disorder, lasting more than 3 months. In the 2010s, when these stringent criteria were applied, the prevalence of insomnia disorder was generally between 6% and 10%. Recent epidemiological studies have estimated the prevalence of short-term insomnia disorder at 11.2% in Europe, 16.3% in Canada, and 16.8% in the Americas, indicating an increase from previous estimates4–7. Insomnia disorder often leads to decreased attention and concentration, contributing to higher accident rates, and long-term consequences such as major depressive disorder, hypertension, myocardial infarction, absenteeism, reduced productivity, diminished quality of life, and increased economic impact1,8–11. Consequently, the high prevalence of insomnia disorder may result in significant social and economic burdens, underscoring the necessity for effective management strategies.

Various clinical practice guidelines on insomnia recommend cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) as the standard treatment12–14. CBT-I, an evidence-based, non-pharmacological approach, integrates components such as cognitive restructuring, sleep restriction, stimulus control, sleep hygiene education, and relaxation and has been proven effective in treating insomnia15–17. However, actual clinical implementation faces challenges due to factors like limited awareness, accessibility issues, a shortage of therapists, significant treatment duration and effort, and high costs. As a result, patients with insomnia often receive prescriptions for sleeping pills, which can cause side effects including tolerance, dependence, increased fall risk, and daytime drowsiness; the long-term side effects remain uncertain13,18–20. Therefore, a new treatment or delivery method is needed to address the limitations of CBT-I, ensuring it remains a safe, effective, and sustainable primary treatment.

In this context, digital CBT-I (dCBT-I) was developed to address the limitations of traditional face-to-face CBT-I, enabling the delivery of CBT-I components through digital technologies like telephone, internet, and web without the need to visit clinics or hospitals. Over the last 20 years, dCBT-I has been consistently studied21–24. dCBT-I has generally shown a large effect size in patients with insomnia according to several meta-analyses, proving effective also in patients with depression and anxiety disorders, which are common comorbidities of insomnia25–27. Drawing on these clinical evidence, digital medical devices (DMDs) have been developed. The number of prescription DMD products reviewed and approved by regulatory agencies globally is on the rise28. These prescription DMDs can be monitored by clinicians post-prescription with minimal involvement, allowing patients to proceed with treatment via customized feedback from the DMD algorithm. Thus, symptoms of insomnia can be alleviated without a therapist’s intervention, highlighting one of the significant benefits of fully automated dCBT-I (FA dCBT-I)29–31. Such FA dCBT-I promises to enhance cost-effectiveness and access to treatment for insomnia32,33.

However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no systematic reviews and meta-analyses that have directly analyzed FA dCBT-I interventions25,27,34–42. Research by Soh et al., Deng et al., and Lee et al. conducted subgroup analyses on FA dCBT-I, revealing a large effect size for insomnia severity. Nonetheless these studies only covered literature until January 2022, included a limited number of studies, and addressed only simple effect sizes compared to inconsistent control groups for insomnia severity27,36,38. Three studies performing network meta-analysis indicated varying effect size rankings for sleep-related outcomes for FA dCBT-I, with the study by Forma et al. focusing soley on specific FA dCBT-I product40–42. Moreover, while adherence is a crucial factor for realizing the potential of digital interventions, research on adherence and its influence on effect size remains scarce27,43. Consequently, there is a pressing need for updated systematic reviews and meta-analyses to comprehensively assess the effectiveness of FA dCBT-I44–52.

The objective of this meta-analysis was to assess the effectiveness of FA dCBT-I interventions for insomnia symptoms. We aimed to investigate the impact of FA dCBT-I on insomnia severity, sleep diary parameters, and intervention adherence, and conducted subgroup analyses to compare insomnia severity across various consistently categorized control groups. Additionally, we executed meta-regression analyses to identify variables influencing insomnia severity and explain heterogeneity.

Results

Study flow

Study selection was depicted using the PRISMA flow diagram as illustrated in Fig. 1. Initially, 3101 documents were identified through the search strategy. After duplicates were removed, 1974 documents underwent titles and abstracts screening. Of these, 129 documents were fully reviewed, resulting in 29 articles being included in the meta-analysis.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

This diagram shows the number of articles identified in each database through this study, and the number of studies included and excluded by the systematic review process. A total of 3101 articles were identified from four databases, and 129 articles remained after the deduplication and screening process. A total of 29 studies were included after the full text review.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the 29 studies included in the meta-analysis are summarized in Table 1. Among these, 12 were conducted in Europe, 7 in the United States, 6 in Oceania, and 4 in Asia. All included studies employed a parallel design; 4 were three-arm comparisons, while the remained were two-arm comparisons. The control groups included 10 waitlist, 9 online education about sleep, 5 placebo, 3 treatment as usual (TAU), 2 dCBT-I with therapist support, 1 face-to-face CBT-I, 1 dCBT for anxiety, and 1 three good things (TGT) exercise. The TGT exercise is a simple diary-like exercise that involves listing three good things that happened and providing a written explanation of why they happened49. It was set as a control because there is research showing a correlation between positive emotions and sleep53.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Author | Year | Country | Total sample size (% Female) | Mean age, years (SD) | Study design | Insomnia severity (baseline) | Other health conditions | dCBTi components | No of sessions | Assessment point | Insomnia outcome measurements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batterham et al.80 | 2017 | Australia | 1149 (73.54) | 42.73 (12.21) | 2 parallel arms (SHUTi, Placebo) | 3 ≥ BIS | Depression | SR, SC, SHE, CR, RP | 6 |

Post 6 weeks Follow up 6 months, 12 months. 18 months |

ISI |

| Batterham et al.44 | 2024 | Australia | 1149 (73.54) | 42.73 (12.21) | 2 parallel arms (SHUTi, Placebo) | 3 ≥ BIS | Depression | SR, SC, SHE, CR, RP | 6 |

Post 6 weeks Follow up 6 months, 12 months. 18 months |

SE, SOL, TST, WASO, NWAK |

| Chan et al.45 | 2023 | Hong Kong | 320 (72.81) | 27.27 (7.24) | 2 parallel arms (proACT-S, waitlist) | 8 ≥ ISI | Depression | SHE, RT, SR, SC. CR | 6 |

post 6 weeks follow up (Uncontrolled) 12 weeks |

ISI, PSQI, SE, SL, TST, SF-12 |

| Cheng et al.57 | 2018 | United States | 1385 (78.88) | 45.05 (15.50) | 2 parallel arms (Sleepio, OSE) | DSM-5 criteria | None | SR, SC, CR, PI, RT, SHE | 6 |

Post 6 weeks Follow up 1 year |

ISI |

| Christensen et al.81 | 2016 | Australia | 1149 (73.54) | 42.73 (12.21) | 2 parallel arms (SHUTi, Placebo) | 3 ≥ BIS | Depression | SR, SC, SHE, CR, RP | 6 |

Post 6 weeks Follow up 6 months |

ISI |

| Espie et al.29 | 2012 | United Kingdom | 164 (73.17) | 49.03 (13.58) | 3 parallel arms (Sleepio, Placebo, TAU) | DSM-5 criteria | None | SHE, RT, SC, SR, CT | 6 |

Post minimum of 6 weeks Follow up 8 weeks |

SCI, SE, SOL, TST, WASO |

| Espie et al.58 | 2019 | United Kingdom | 1711 (77.67) | 48.05 (13.75) | 2 parallel arms (Sleepio, Online SHE) | 16 ≤ SCI | None | SC, RT, PI, CR, PE, SHE | 6 |

Mid 4 weeks Post 8 weeks Follow up 24 weeks 36 weeks (uncontrolled) 48 weeks (uncontrolled) |

GSII, ESS, SCI |

| Felder et al.64 | 2020 | United States | 208 (100) | 33.55 (3.72) | 2 parallel arms (Sleepio, TAU) | 11 ≥ ISI | Pregnant | SR, SC, CT, RT, SHE | 6 |

Post 10 weeks |

ISI, PSQI, SCI, SE, TST |

| Glozier et al.59 | 2019 | Australia | 87 (0) | 58.36 (6.21) | 2 parallel arms (SHUTi, Online PE) | 8 ≥ ISI | Depression | SR, SC, SHE, CR, RP | 6 |

Post 12 weeks Follow up 6 months |

ISI |

| Hagatun et al.82 | 2019 | Norway | 181 (67.40) | 44.90 (13.03) | 2 parallel arms (SHUTi, OPE) | DSM-4 criteria | None | SR, SC, SHE, CR, RP | 6 |

Post 9 weeks Follow up (Uncontrolled) 6 months |

ISI, BIS, DBAS-16, EMA, SE, SOL, TIB, TST, WASO |

| Hinterberger et al.46 | 2023 | Austria | 59 (66.1) | 45.83 (16.49) | 2 parallel arms (NUKKUAA®, Waitlist) |

8 ≥ ISI 6 ≥ PSQI |

None | BSE, CR, RE, SHE, SR, SC | 6 |

Post 6 weeks Follow up 10 weeks |

ISI, PSQI, SE, SOL, TIB, TST, WASO |

| Horsch et al.60 | 2017 | Netherlands | 151 (62.25) | 40.02 (13.50) | 2 parallel arms (Sleepcare, Waitlist) | 7 ≥ ISI | None | RE, SR, SHE, PS | 4 |

Post 7 weeks Follow up (Only dCBTi group) 3 months |

ISI, PSQI, DBAS-16, HADS, CES-D, NWAK, SE, SOL, SQ, TIB, TST, TW, WASO |

| Kallestad et al.47 | 2021 | Norway | 101 (75.25) | 41.35 (11.57) | 2 parallel arms (SHUTi, FtF CBTi) | DSM-5 criteria | None | SR, SC, SHE, CR, RP | 6 |

Post 9 weeks Follow up 6 months |

ISI, EMA, NWAK, SE, SOL, TST, WASO |

| Kalmbach et al.61 | 2020 | United States | 91 (100) | 29.03 (4.18) | 2 parallel arms (Sleepio, OSE) | 10 ≥ ISI | Pregnant | SR, SC, CR, PI, RT, SHE | 6 |

Post a week after completing treatment Follow up 6 week after childbirth |

ISI, PSQI, EPDS, PSAS-C, TST |

| Kyle et al.83 | 2020 | United Kingdom | 410 (86.59) | 52.45 (11.45) | 2 parallel arms (Sleepio, Waitlist) | DSM-5 criteria | None | SR, SC, CR, PI, RT, SHE | 6 |

Post 10 weeks Follow up 24 weeks |

BC-CCI, ISI, PSQI, MFI, ESS, CFQ, PHQ-9, GAD-2 |

| Lancee et al.65 | 2012 | Netherlands | 623 (69.66) | 51.77 (12.14) | 3 parallel arms (dCBTi, PP CBTi by email, Waitlist) | 19 ≥ SLEEP-50 | None | PE. SC, SHE, SR, CR, PI | 6 |

Post 11 weeks Follow up (uncontrolled) 18 weeks 48 weeks |

SLEEP-50, NWAK, SE, SOL, TST, WASO |

| Lancee et al.66 | 2013 | Netherlands | 262 (75.19) | 48.34 (12.56) | 2 parallel arms (dCBTi without support, dCBTi with support) |

19 ≥ SLEEP-50 7 ≥ ISI |

None | PE. SC, SHE, SR, CR, PI | 6 |

Post 11 weeks Follow up 6 months |

ISI, NWAK, SE, SOL, SQ, TIB, TST, WASO |

| Lorenz et al.84 | 2018 | Switzerland | 56 (69.64) | 42.84 (18.72) | 2 parallel arms (mementor somnium, Waitlist) | 8 ≥ ISI | None | PE, SR, RE, SHE, CR, CSRB | 6 |

Post 6 weeks Follow up (uncontrolled) 12 months |

ISI, APSQ, SRBQ, SE, SOL, TST, WASO |

| Mason et al.48 | 2023 | Australia | 120 (75.00) | 46.69 (13.19) | 2 parallel arms (This Way up, dCBTa) | 14 > ISI | Anxiety | PE, SHE, SC, SR, CT, RP | 4 |

Post 8 weeks Follow up 3 months |

ISI, SE, SOL, SQ, TST, WASO |

| McGrath et al.62 | 2017 | Ireland | 134 (61.19) | 59.00 (10.97) | 2 parallel arms (Sleepio, TAU) | DSM-5 criteria | blood pressure 130–160/ < 110 mm Hg | SR, SC, CR, PI, RT, SHE | 6 |

Post 8 weeks |

ISI, PSQI, SCI, SE, SOL, TST, WASO |

| Ritterband et al.55 | 2009 | United States | 45 (77.27) | 44.87 (11.15) | 2 parallel arms (SHUTi, Waitlist) | DSM-4 criteria | None | SR, SC, SHE, CR, RP | 6 |

Post 9 weeks Follow up (only dCBTi group) 6 months |

ISI, NWAK, SE, SOL, SoS, TIB, TST, WASO |

| Ritterband et al.56 | 2011 | United States | 28 (85.71) | 56.65 (11.94) | 2 parallel arms (SHUTi, Waitlist) | DSM-4 criteria | Cancer | SR, SC, SHE, CR, RP | 6 |

Post 9 weeks |

ISI, NWAK, SE, SOL, SoS, TIB, TST, WASO |

| Ritterband et al.30 | 2017 | United States | 303 (71.95) | 43.28 (11.61) | 2 parallel arms (SHUTi, OPE) | 6.5 ≤ TST | None | SR, SC, SHE, CR, RP | 6 |

Post 9 weeks Follow up 6 months 1 year |

ISI, NWAK, SE, SOL, SQ, TST, WASO |

| Sato et al.49 | 2022 | Japan | 312 (41.48) | 50.49 (10.82) | 3 parallel arms (dCBTi, TGT exercise, Waitlist) |

6 ≥ AIS 6 ≥ PSQI |

None | SC, CR, SR | 4 |

Post 4 weeks Follow up 8 weeks |

PSQI, AIS, SE, SOL, TST |

| Theadom et al.63 | 2018 | New Zealand | 24 (62.50) | 35.88 (9.47) | 2 parallel arms (RESTORE, OPE) | 5 ≥ PSQI | Traumatic Brain Injury | PE, RE, SR, CT, MM | 6 |

Post 6 weeks |

PSQI, NWAK, SE, SOL, WASO |

| Vedaa et al.67 | 2020 | Norway | 1,721 (67.81) | 44.45 (13.95) | 2 parallel arms (SHUTi, OPE) | 12 ≥ ISI | None | SR, SC, CR, SHE, RP | 6 |

Post 9 weeks |

ISI, BIS, EMA, NWAK, SE, SF-12, SMU, SOL, TIB, TST, WASO |

| Watanabe et al.50 | 2023 | Japan | 175 (58.29) | 44.16 (13.46) | 2 parallel arms (Yukumi, Sham) | 9 ≥ AIS | None | SHE, SC, SR, CT, RT | 6 |

Post 8 weeks Follow up 10 weeks |

AIS, NWAK, SE, SOL |

| Yang et al.51 | 2023 | Taiwan | 92 (72.83) | 22.40 (2.53) | 3 parallel arms (REFRESH without support, with support, Waitlist) | 8 ≥ ISI | None | PE, SR, SC, RE, MM, SHE, CR, RP | 8 |

Post 8 weeks |

ISI, DBAS-16, SHPS, NWAK, SE, SOL, SQ, TST, WASO |

| Zhou et al.52 | 2022 | United States | 333 (100) | 59.56 (8.04) | 3 parallel arms (SHUTi-BWHS, SHUTi, OPE) | 15 ≥ ISI | None | SR, SC, SHE, CR, RP | 6 |

Post 9 weeks Follow up 6 months |

ISI, PSQI, SE, SOL, TIB, TST, WASO |

BIS Bergen Insomnia Scale, SR sleep restriction, SC stimulus control, SHE sleep hygiene education, CR cognitive restructuring, RP relapse prevention, ISI Insomnia Severity Index, SE sleep efficiency, SOL sleep onset latency, TST total sleep time, WASO wakefulness after sleep onset, NWAK number of awakenings, RT relaxation therapy, PSQI Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, SL sleep latency, SF-12 12-Item Short Form Health Survey, DSM-5 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition, OSE online sleep education, PI paradoxical intention, TAU treatment as usual, CT cognitive techniques, SCI Sleep Condition Index, PE psyco education, GSII Glasgow Sleep Impact Index, ESS Epworth Sleepiness Scale, OPE online patient education, DSM-4 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition, DBAS-16 Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep-16, EMA early morning awakening, TIB time in bed, BSE basic sleep education, RE relaxation exercise, PS persuasive strategies, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, CES-D Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale, SQ sleep quality, TW terminal wakefulness, FtF Face to Face, EPDS Edinburgh postnatal depression scale, PSAS-C PreSleep Arousal Scale-Cognitive factor, BC-CCI The British Columbia Cognitive Complaints Inventory, MFI multidimensional fatigue inventory, CFQ Cognitive Failures Questionnaire, PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire, GAD-2 General Anxiety Disorder scale, PP paper and pencil, CSRB changing sleep related behaviours, APSQ Anxiety and Preoccupation about Sleep Questionnaire, SRBQ Sleep-Related Behaviour Questionnaire, dCBTa digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for anxiety, SoS Soundness of Sleep, TGT Three Good Thing, AIS Athens Insomnia Score, MM mindfulness meditation, SMU sleep medication use, SHPS Sleep hygiene Practice Scale, BWHS Black Women’s Health Study.

A total of 9475 participants were included in this meta-analysis, with 4847 randomly assigned to the FA dCBT-I group, where 73.30% were female. The mean age of participants was 45.71 ± 14.23 years. Six studies focused on populations with comorbid psychiatric disorders (5 on depression and 1 on anxiety), and three targeted populations with cancer, traumatic brain injury, and hypertension, respectively. Two studies focused on pregnant women. The FA dCBT-I group had 4 to 8 sessions, averaging 5.86 sessions. Two studies assessed intervention adherence. Watanabe et al. measured it by the rate of sessions completed against the number of scheduled sessions, and Yang et al. used the Treatment Components Adherence Scale (TCAS)50,51,54. Conversely, 19 studies reported the number of participants who completed the intervention, with an average completion rate for FA dCBT-I of 59.33%, ranging from 16.67% to 85.71%.

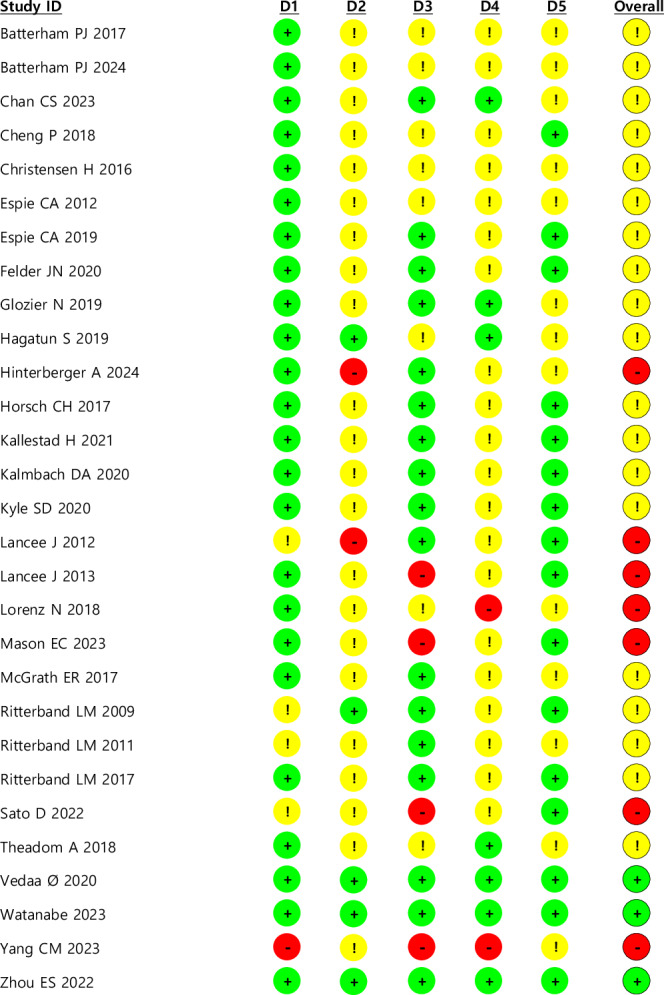

Risk of bias

Figure 2 displays the results of the risk of bias assessment using the RoB 2.0 tool. Three studies were judged to have a low risk of bias, 19 had some concerns, and 7 were considered high risk. The risk of bias was generally some concern in the Deviation from intended intervention and Measurement of the outcomes domains. The reason for the risk of bias in the Deviation from intended intervention domain was that most studies were open label due to the nature of the intervention, and they showed high dropout rates and low completion rate of intervention. In the Measurement of the outcomes domain, the reason was that most of the open label and sleep-related intervention outcome measurement methods were self-reported methods.

Fig. 2. Risk of bias summary.

This presents the results of the risk of bias assessment using the RoB 2.0 tool for the included randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The assessment covered five domains: (1) the randomization process, (2) deviations from intended interventions, (3) missing outcome data, (4) measurement of the outcome, and (5) selection of the reported result. Each study was assessed according to established criteria, and the overall risk of bias was determined based on domain-specific ratings. Studies with low risk of bias in all domains were classified as having an overall low risk, whereas studies with at least one high-risk domain were classified as high risk. Among the studies, 3 were judged to have a low risk of bias (green), 19 exhibited some concerns (yellow), and 7 were classified as high risk (red). The most frequently observed concerns were related to the domains of (2) deviation from intended intervention and (4) measurement of outcomes.

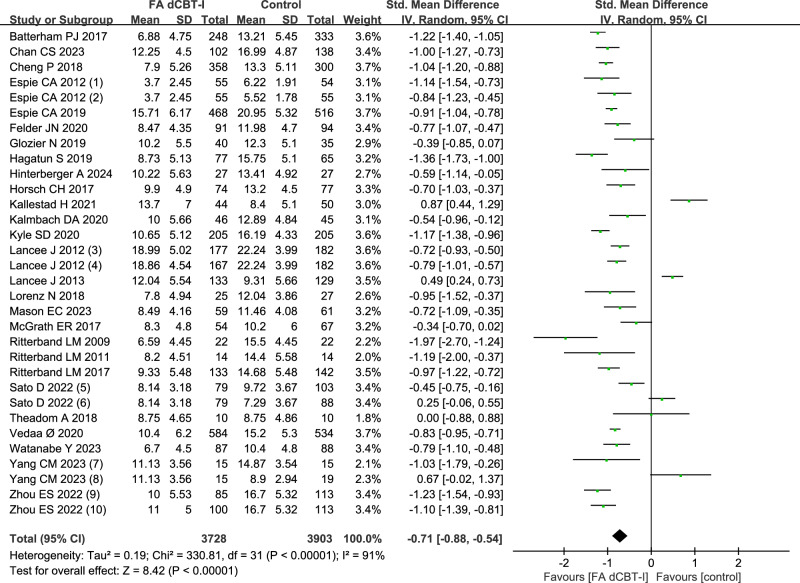

Post-treatment effect

Insomnia severity measurements varied across included studies: Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Sleep Condition Indicator (SCI), Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS), and Sleep-50. When multiple scales were reported, the ISI was selected. The post-treatment effect of FA dCBT-I on insomnia severity showed a moderate to large effect size (Fig. 3; SMD = −0.71; 95% CI: −0.88, −0.54; p < 0.001; k = 32). Statistical heterogeneity across studies for effect sizes was considerable (Fig. 3; I2 = 91%; Q = 330.81; df = 31; p < 0.001).

Fig. 3. The effect of FA dCBT-I on insomnia severity.

This figure presents a forest plot summarizing the standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals for various studies comparing FA dCBT-I with control interventions. The control groups consisted of different conditions: (1) TAU, (2) placebo, (3) paper and pencil CBT-I delivered by e-mail vs waitlist, (4) electronic CBT-I vs waitlist, (5) waitlist, (6) TGT exercise, (7) waitlist, (8) dCBT-I with therapist support, (9) SHUTi vs patient education about sleep, and (10) SHUTi-BWHS vs patient education about sleep. The post-treatment effect of FA dCBT-I on insomnia severity showed a moderate to large effect size (SMD = −0.71; 95% CI: −0.88, −0.54; p < 0.001; k = 32; I2 = 91%).

Sleep diary outcomes revealed a small effect for total sleep time (TST) (Supplementary Fig. 1; SMD = 0.19; 95% CI: 0.07, 0.31; p = 0.002; I2 = 73%; k = 24), and small to moderate effects for sleep efficiency (SE) (Supplementary Fig. 2; SMD = 0.45; 95% CI: 0.27, 0.64; p < 0.001; I2 = 88%; k = 25), sleep onset latency (SOL) (Supplementary Fig. 3; SMD = −0.39; 95% CI: −0.53, -0.24; p < 0.001; I2 = 79%; k = 23), and wakefulness after sleep onset (WASO) (Supplementary Fig. 4; SMD = −0.38; 95% CI: -0.57, −0.19; p < 0.001; I2 = 86%; k = 20).

Post-treatment effects by control type classification

The control group was divided into six categories: waitlist, TAU, placebo, online education about sleep, non-sleep psychological intervention, and CBT-I with therapist support. FA dCBT-I showed a large effect compared to waitlist (Fig. 4; SMD = −0.88; 95% CI: −1.07, −0.70; p < 0.001; I2 = 67%; k = 11), placebo (Fig. 4; SMD = −0.98; 95% CI: −1.30, −0.67; p < 0.001; I2 = 72%; k = 3), and online education about sleep (Fig. 4; SMD = −0.93; 95% CI: −1.07, −0.79; p < 0.001; I2 = 68%; k = 10). It also demonstrated a moderate to large effect compared to TAU (Fig. 4; SMD = −0.74; 95% CI: −1.16, −0.67; p < 0.001; I2 = 76%; k = 3). CBT-I with therapist support (Fig. 4; SMD = 0.61; 95% CI: 0.37, 0.85; p < 0.001; I2 = 16%; k = 3) showed a moderate effect relative to FA dCBT-I.

Fig. 4. The effect of FA dCBT-I on insomnia severity by control type.

This figure presents the standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals for FA dCBT-I compared to six control groups: waitlist, treatment as usual (TAU), placebo, online education about sleep, non-sleep psychological intervention, and CBT-I with therapist support. The intervention groups consisted of different conditions: (1) electronic CBT-I, (2) paper and pencil CBT-I delivered by e-mail, (3) SHUTi, and (4) SHUTi-BWHS. FA dCBT-I demonstrated a large effect compared to waitlist (SMD = −0.88; 95% CI: −1.07, -0.70; p < 0.001; I² = 67%; k = 11), placebo (SMD = −0.98; 95% CI: −1.30, −0.67; p < 0.001; I² = 72%; k = 3), and online education about sleep (SMD = −0.93; 95% CI: −1.07, −0.79; p < 0.001; I² = 68%; k = 10). Additionally, FA dCBT-I showed a moderate to large effect compared to TAU (SMD = −0.74; 95% CI: −1.16, -0.67; p < 0.001; I² = 76%; k = 3). In contrast, CBT-I with therapist support showed a moderate effect relative to FA dCBT-I (SMD = 0.61; 95% CI: 0.37, 0.85; p < 0.001; I² = 16%; k = 3).

Sensitivity analysis

When studies that did not report the inclusion or exclusion of participants with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were excluded, FA dCBT-I demonstrated a moderate to large effect (Supplementary Fig. 5; SMD = −0.72; 95% CI: −0.88, −0.55; p < 0.001; I² = 90%; k = 28)49,55,56. The same was observed when studies that did not investigate participants with a history of suicide attempts were excluded (Supplementary Fig. 6; SMD = −0.73; 95% CI: −0.98, −0.47; p < 0.001; I² = 94%; k = 14)29,46,47,55–63.

Furthermore, when studies that did not report stable use of hypnotic medications were excluded, FA dCBT-I demonstrated a large effect size (Supplementary Fig. 7; SMD = –0.88; 95% CI: −1.05, −0.70; p < 0.001; I² = 85%; k = 20)46,47,57,63–67. This was primarily because all studies comparing therapist-guided CBT-I and FA dCBT-I were excluded47,51,66. Lastly, robust effect was observed even after excluding studies investigating non-algorithm based FA dCBT-I (Supplementary Fig. 8; SMD = −0.71; 95% CI: −0.88, −0.54; p < 0.001; I² = 91%; k = 32)48,51,65,66.

Follow-up treatment effect

The follow-up effects on insomnia severity were all moderate; short term (Supplementary Fig. 9; SMD = −0.54; 95% CI: −0.84, −0.23; p < 0.001; I2 = 80%; k = 7), medium term (Supplementary Fig. 9; SMD = −0.54; 95% CI: −0.91, −0.18; p = 0.004; I2 = 95%; k = 10), and long term (Supplementary Fig. 9; SMD = −0.76; 95% CI: −0.87, −0.65; p < 0.001; I2 = 0%; k = 4). There was no statistically significant difference when comparing follow-up periods (p = 0.24).

The follow-up effects on TST in sleep diary demonstrated statistically significant small effects in the short term and long term; short term (Supplementary Fig. 10; SMD = 0.31; 95% CI: 0.16, 0.46; p < 0.001; I2 = 0%; k = 5), medium term (Supplementary Fig. 10; SMD = −0.05; 95% CI: −0.29, −0.20; p = 0.72; I2 = 80%; k = 7), long term (Supplementary Fig. 10; SMD = 0.28; 95% CI: 0.05, 0.50; p = 0.02; I2 = 56%; k = 3). There was a statistically significant difference when compared by follow-up periods (p = 0.04).

The follow-up effect on SE showed a statistically significant moderate effect in the short and long terms; short term (Supplementary Fig. 11; SMD = 0.56; 95% CI: 0.14, 0.97; p = 0.009; I2 = 86%; k = 5), medium term (Supplementary Fig. 11; SMD = 0.34; 95% CI: −0.03, 0.72; p = 0.07; I2 = 91%; k = 6), long term (Supplementary Fig. 11; SMD = 0.61; 95% CI: 0.46, 0.76; p < 0.001; I2 = 0%; k = 3). There was no statistically significant difference when compared by follow-up periods (p = 0.43).

The follow-up effect on SOL demonstrated a statistically significant effect in the short and long terms, specifically, a large effect in the short term and a moderate effect in the long term; short term (Supplementary Fig. 12; SMD = −0.96; 95% CI: −1.81, −0.10; p = 0.03; I2 = 96%; k = 5), medium term (Supplementary Fig. 12; SMD = −0.23; 95% CI: −0.54, 0.08; p = 0.15; I2 = 87%; k = 6), long term (Supplementary Fig. 12; SMD = −0.47; 95% CI: −0.62, -0.32; p < 0.001; I2 = 0%; k = 3). No statistically significant differences were observed when comparisons were made across follow-up periods (p = 0.19).

The follow-up effect on WASO yield a statistically significant small effect in both the medium and long terms; short term (Supplementary Fig. 13; SMD = −1.04; 95% CI: −2.17, 0.10; p = 0.07; I2 = 96%; k = 3), medium term (Supplementary Fig. 13; SMD = −0.32; 95% CI: −0.58, −0.05; p = 0.02; I2 = 82%; k = 6), long term (Supplementary Fig. 13; SMD = −0.45; 95% CI: −0.63, −0.26; p < 0.001; I2 = 36%; k = 3). No statistically significant differences were observed when compared by follow-up periods (p = 0.41).

Treatment completion rate

The pooled treatment completion rate of 19 studies, reporting the number of patients completing the intervention, was 55.90% (95% CI: 50.19%, 61.61%). We classified these 19 studies into subgroups based on whether their completion rate was above or below 55.14%. Subgroup analysis showed that studies with above 55.90% (Supplementary Fig. 14; SMD = −0.81; 95% CI: −1.09, −0.53; p < 0.001; I2 = 87%; k = 13) had a greater effect than those with below 55.90% (Supplementary Fig. 14; SMD = −0.48; 95% CI: −0.85, −0.12; p = 0.009; I2 = 95%; k = 9), although the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.17).

Publication bias

The funnel plot for post-treatment insomnia severity is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 15. The result of Egger’s test revealed no statistically significant publication bias (t = 1.34, df = 30, p = 0.19).

Meta-regression analysis

The results of the meta-regression analysis are displayed in Table 2. Of the nine moderator variables evaluated, only the control type showed statistical significance in affecting insomnia severity, with a coefficient of 0.184 and a 95% confidence interval of 0.083 to 0.284 (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Meta-regression analyses of the effect on the insomnia severity

| Moderator | Studies, n | b (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No of participants | 32 | −0.00 (−0.001, 0.000) | 0.227 |

| Percentage of women | 32 | −0.009 (−0.018, 0.001) | 0.086 |

| Mean age | 32 | −0.010 (−0.031, 0.011) | 0.344 |

| Comorbid insomnia | 32 | 0.001 (−0.439, 0.441) | 0.997 |

| Control type | 32 | 0.184 (0.083, 0.284) | <0.001 |

| Baseline ISI | 23 | −0.023 (−0.154, 0.108) | 0.729 |

| Treatment duration | 32 | −0.054 (−0.145, 0.037) | 0.248 |

| No of treatment sessions | 32 | −0.039 (−0.274, 0.196) | 0.746 |

| Completion rate | 22 | −0.008 (−0.023, 0.007) | 0.310 |

Discussion

Although prescription digital medical devices (DMDs) have entered the market, their value is not definitively established, prompting many nations to opt for temporary over permanent reimbursement as they evaluate real-world evidence. Consequently, further research into the treatment effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of DMDs is essential28,68,69. This meta-analysis was aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of FA dCBT-I, a principle technology in current prescription DMDs, in ameliorating insomnia symptoms, thus contributing to the scientific foundation supporting of DMDs.

FA dCBT-I demonstrated moderate to large effects on insomnia severity compared to controls across 29 included studies. Previous studies analyzing FA dCBT-I through subgroup analyses reported large effects on insomnia, yet this study noted a relatively smaller estimated effect size compared to those in earlier research27,36,38. The study by Soh et al. conducted subgroup analyses based on the presence or absence of therapist guidance, including 17 studies on unguided dCBT-I, and found that unguided dCBT-I was more efficacious. Deng et al. also performed a subgroup analysis by guidance modality, identifying large effect sizes in both animated therapist dCBT-I (8 studies) and unguided dCBT-I (10 studies). Lee et al. analyzed 14 studies on FA dCBT-I among insomnia patients with comorbid depression and anxiety, revealing a large effect size of SMD = −0.81 (95% CI: −1.04, −0.59). These differences in results may stem from variations in study participant and intervention inclusion/exclusion criteria or could be attributed to this study’s inclusion of all recent publications.

In sleep diaries, TST demonstrated a small effect, whereas other parameters showed small to moderate effects. The finding that TST in sleep diaries had a relatively small effect compared to other parameters suggests that factors enhancing sleep quality contribute to improved sleep efficiency by bettering sleep maintenance, depth, and time to sleep onset, rather than directly influencing TST. One reason for pronounced impact on insomnia severity compared to sleep diaries might be that both are assessed through subjective methods. However, sleep diaries target more specific sleep patterns, indicating that the measurement of insomnia severity is more influenced by subjective experience. This finding is consistent with a high risk of bias across studies in the fourth domain (measurement of the outcome). Similar trends have been observed in previous studies, where the effects on TST were generally smaller than those on other sleep parameters, and the effects on insomnia severity were greater than those in sleep diary outcomes. This pattern has been documented in prior meta-analyses on dCBT-I effects on sleep by Zachariae et al., Tsai et al., Deng et al., and Lee et al., as well as in traditional CBT-I studies25,27,37,38,70.

In examining the FA dCBT-I by follow-up period, it was observed that there was no statistically significant difference in all parameters depending on the period, except for TST, indicating that the effect was sustained in the long term. For TST, medium-term follow-up showed greater effects for the control group, though these were not statistically significant, with considerable heterogeneity. The study by Zachariae et al. summarized the results from a follow-up period ranging from 4 to 48 weeks, reporting a large effect in insomnia severity (k = 5), a medium effect in SE, WASO (k = 4), and a small effect in SOL, TST (k = 4)25. However, SOL, WASO, and TST did not show statistically significant effects, and the number of included studies was limited. Other studies also reported the follow-up effect, but direct comparison of effect sizes is challenging because they are calculated as the mean difference34–36.

Subgroup analyses with consistent control group classification revealed that FA dCBT-I exhibited significantly higher effect sizes compared to all control groups, except when compared with Non-sleep psychological intervention and CBT-I with therapist support. Nevertheless, CBT-I with therapist support, such as face-to-face CBT-I, demonstrated greater effects than FA dCBT-I. This suggest that a hybrid approach, combining therapist support with prescription DMDs, might enhance the effectiveness of DMDs for insomnia treatment. Consistent with this observation, Deng et al. reported the largest effect size (Hedges’s g = −1.19; 95% CI: −1.45, −0.92) in their subgroup analysis for therapist-guided interventions38.

We hypothesized that the efficacy of prescription DMDs as a treatment option comparable to traditional CBT-I would not only depend on completing the intervention but also consistently adhering to self-help practices. Therefore, this study aimed to examine adherence and its impact on effect size. However, since only two studies reported on adherence and used different methods for measuring it, we performed a subgroup analysis based on the pooled intervention completion rate, including only studies reporting complete participation. Although the effect size was larger in studies with above pooled completion rates, the difference was not statistically significant, and meta-regression results also indicated that the completion rate did not significantly influence the effect size.

In a recent study by Thorndike et al. adherence was defined as the intervention completion rate among 1565 participants in a real-world setting, with a rate of 46.8%, which was lower than the completion rate observed in this meta-analysis71. Because there is no standardized tool to measure adherence, completion rate is often reported as adherence. However, the findings of this meta-analysis emphasize that completion rate alone is not the critical factor influencing the effectiveness of prescribed DMDs, and suggest the need to focus on adherence.

Although there are many DMD products preparing to enter the market, the regulatory framework for implementing adherence assessment is not yet ready72. Schwartz et al. analyzed the application of the existing drug adherence framework to DMD at the micro, mesa, and macro levels73. Further research is needed to standardize this framework, and clinical trials or real-world studies that attempt to apply it are needed.

CBT-I interventions encompass various components such as sleep restriction, stimulus control, cognitive restructuring, relaxation, and sleep hygiene education. While multicomponent CBT-I offers comprehensive treatment, its complexity may reduce adherence in unguided digital formats. On the other hand, pure sleep restriction therapy, which is simpler and more structured, may achieve higher adherence in a digital format74,75. This suggests a need to tailor digital CBT-I interventions based on the feasibility of delivering specific components and their adherence potential in a fully automated setting.

One limitation of this study, similar to previous research, is the high heterogeneity observed in most synthesized outcomes. Meta-regression analysis identified control types as the sole variable significantly influencing heterogeneity and treatment effects. Although heterogeneity was reduced in subgroup analyses by control type, it persisted underscoring the need for further investigation into heterogeneity sources. Another limitation is that, despite intentions to analyze quality of life and adherence in the protocol, only two studies reported quality of life data, preventing any further analysis. Lastly, the dynamic nature of DMD was not represented. Given the evolving nature of DMD as software medical devices prone to updates, further research is necessary to consider these characteristics in effectiveness evaluations72.

This study focused on evaluating the efficacy of FA dCBT-I in ameliorating insomnia symptoms to ascertain the therapeutic potential of prescription DMD. FA dCBT-I demonstrated moderate to large effects compared to the control group, yet it did not achieve the efficacy of CBT-I with therapist support. This indicates that a hybrid approach combining therapist support might be needed for prescription DMD to evolve into a more effective treatment option. Further research that focuses on standardizing adherence measurement methods and the continuous development of DMD is essential, as it will provide specific guidance for maximizing the potential of prescription DMD.

Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook and was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines76,77 (Supplementary Table 1). The protocol for this review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42024526617).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria consisted of adults aged 18 years or older with insomnia, either diagnosed or self-reported, using evidence-based diagnostic criteria. Exclusion criteria included individuals under 18 years; those with prior CBT-I treatment; unstable users of sleeping pills; individuals with a history of suicide attempts, alcohol abuse, or addiction; those with sleep apnea; shift workers; and individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

FA dCBT-I was defined as a digitally delivered CBT-I intervention (via mobile app, email, computer, phone, etc.) without therapist guidance, regardless of the delivery platform. The intervention must include at least one cognitive and one behavioral component and last a minimum of 4 weeks. Control groups included in the studies were Waitlist, Treatment as Usual (TAU), Placebo, sleep education, and therapist-guided CBT-I.

The primary outcomes were self-reported insomnia severity using measures such as the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Sleep Condition Indicator (SCI), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Secondary outcomes included sleep diary measures Total Sleep Time (TST), Sleep Efficiency (SE), Wakefulness After Sleep Onset (WASO), and Sleep Onset Latency (SOL) and adherence to FA dCBT- I. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included.

Search strategy

We searched the PubMed, CENTRAL, Embase and PsycINFO databases for studies published up to March 31, 2024. Searches were conducted using natural language, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and Boolean operators, focusing on intervention, intervention delivery and population. The complete search strategy by database is detailed in the Supplementary Table 2.

Study selection

After removing duplicates, two authors (J.W.H. and G.E.L) independently screened the titles and abstracts based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Following this preliminary screening, they reviewed the full texts to determine the final selection of studies for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, or through discussion with a third reviewer (J.Y.K) when consensus could not be reached. If the studies did not investigate or report some of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study, we included those publications in the meta-analysis to maintain comprehensiveness. However, we performed sensitivity analyses to assess the potential impact of including these studies on the overall meta-analysis results.

Data extraction

Two authors (J.W.H and G.E.L) independently extracted data from the included studies, which encompassed information on study characteristics such as title, authors, year of publication, journal, study area, study design, participant recruitment method, randomization method, and participant details including number of participants, sex, mean age, and standard deviation. Information on the intervention included components, period, and outcome measures, as well as pre, post, and follow-up outcomes (mean, standard deviation, standard error, and 95% confidence interval) for both intervention and control groups. Missing data prompted, contact with the corresponding author, and studies were excluded if there was no response. All disagreements were managed by consensus, or with the aid of a third reviewer (J.Y.K.) if unresolved.

Risk of bias assessment

Two authors (J.W.H. and G.E.L.) independently assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for RCTs (RoB 2.0), which includes five domains: (1) Randomization process; (2) Deviation from intended intervention; (3) Missing outcome data; (4) Measurement of the outcomes; (5) Selection of the reported result. Disagreements were resolved through consensus, or if unresolved, through discussion with a third reviewer (J.H.W.).

Data synthesis and analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using RevMan 5.4, Microsoft Excel, and R version 4.2.3. Data from the extracted studies were synthesized using a random effects model. For this synthesis, the mean difference (MD) and standard deviation (SD) of both the intervention and control groups post-intervention or follow-up observation were used to pool the standardized mean difference (SMD) with a 95% CI78. The follow-up periods were categorized into three durations for analysis: 3 months or less (Short term), more than 3 months and 6 months or less (Medium term), and more than 6 months (Long term). The heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the Cochran Q and I2 tests. A p-value of less than 0.1 indicates heterogeneity. The I2 value ranges denote levels of heterogeneity as follows: 0–40% is low, 30–60% is moderate, 50–90% is substantial, and 75% or more is considered considerable. Publication bias was expressed through a funnel plot, and if the Egger test result p < 0.05, it was considered as publication bias.

In subgroup analysis, the control group classifications from the included studies were consistently applied. In terms of adherence, synthesizing data was unfeasible due to the lack of standardized reporting and the fact that most RCTs only reported the number of participants who completed the sessions. Consequently, the completion rate of the intervention was calculated by dividing the number of participants who completed all prescribed intervention sessions by the number of participants assigned to the intervention group. This completion rate was synthesized based on the meta-analysis method using Excel by Neyeloff et al.79. Subgroup analysis also involved categorizing cases into those with above or below pooled completion rate.

Further, meta-regression analysis using R was undertaken to investigate variables influencing the effect size and heterogeneity in insomnia severity. The moderator variables included the number of participants, average age of participants, the proportion of female participants, presence of comorbidities, classification of the control group, number of intervention sessions, duration of the intervention, baseline severity of insomnia, and the intervention completion rate.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant RS-2024-00331775 from Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2025 and this work was supported and funded by the Dongguk University Research Fund of 2024 (S-2024-G0001-00061).

Author contributions

J.W.H. and G.E.L. conducted the searches, screened the search records and full-text papers against the eligibility criteria and extracted the study characteristics and effect size data. Data analysis and preliminary paper was drafted by J.W.H. and J.Y.K. advised on the data extraction and analysis as well as providing overall feedback on the paper. J.H.W. and S.M.K. also provided guidance and feedback to the paper in preparation for the final paper development. J.Y.K. provided supervision of the overall project and is corresponding author.

Data availability

Data collected and used in this meta-analysis can be requested from corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41746-025-01514-4.

References

- 1.Morin, C. M. & Jarrin, D. C. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, course, risk factors, and public health burden. Sleep. Med. Clin.17, 173–191 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders5th edition (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013).

- 3.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd edition (ICSD-3) (American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Aernout, E. et al. International study of the prevalence and factors associated with insomnia in the general population. Sleep. Med.82, 186–192 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjafield, A. et al. 0404 Americas Prevalence of Insomnia Disorder in Adults: Estimation Using Currently Available Data. Sleep47, A173–A174 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morin, C. M. et al. Prevalence of insomnia and use of sleep aids among adults in Canada. Sleep. Med.124, 338–345 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morin, C. M. et al. Prevalence of insomnia and its treatment in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry56, 540–548 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaput, J.-P. et al. Economic burden of insomnia symptoms in Canada. Sleep. Health9, 185–189 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taddei-Allen, P. Economic burden and managed care considerations for the treatment of insomnia. Am. J. Manag. Care26, S91–S96 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Streatfeild, J., Smith, J., Mansfield, D., Pezzullo, L. & Hillman, D. The social and economic cost of sleep disorders. Sleep44, 10.1093/sleep/zsab132 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Hillman, D. et al. The economic cost of inadequate sleep. Sleep41, 10.1093/sleep/zsy083 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Riemann, D. et al. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J. Sleep. Res.26, 675–700 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sateia, M. J., Buysse, D. J., Krystal, A. D., Neubauer, D. N. & Heald, J. L. Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Sleep. Med.13, 307–349 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qaseem, A., Kansagara, D., Forciea, M. A., Cooke, M. & Denberg, T. D. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med.165, 125–133 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morin, C. M., Kowatch, R. A., Barry, T. & Walton, E. Cognitive-behavior therapy for late-life insomnia. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol.61, 137–146 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okajima, I., Komada, Y. & Inoue, Y. A meta-analysis on the treatment effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for primary insomnia. Sleep. Biol. Rhythms9, 24–34 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koffel, E. A., Koffel, J. B. & Gehrman, P. R. A meta-analysis of group cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep. Med. Rev.19, 6–16 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandt, J. & Leong, C. Benzodiazepines and Z-drugs: an updated review of major adverse outcomes reported on in epidemiologic research. Drugs R. D.17, 493–507 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pardo-Cabello, A. J., Manzano-Gamero, V. & Luna-Del Castillo, J. D. Adverse drug reactions among the most used hypnotic drugs in Spain. Rev. Clin. Esp.221, 128–130 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yue, J. L. et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological treatments for insomnia in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sleep. Med. Rev.68, 101746 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strom, L., Pettersson, R. & Andersson, G. Internet-based treatment for insomnia: a controlled evaluation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol.72, 113–120 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin, J. et al. Efficacy of mobile app-based cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: multicenter, single-blind randomized clinical trial. J. Med. Internet Res.26, e50555 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clara, M. I., Van Straten, A., Canavarro, M. C. & Allen Gomes, A. Digital cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia in cancer survivors: protocol for a pragmatic clinical trial. Acta Méd. Port.37, 713–719 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skarpsno, E. S. et al. Effectiveness of digital Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Insomnia in patients with musculoskeletal complaints and insomnia in primary care physiotherapy: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open14, e083592 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zachariae, R., Lyby, M. S., Ritterband, L. M. & O’Toole, M. S. Efficacy of internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia—a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep. Med. Rev.30, 1–10 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin, W., Li, N., Yang, L. & Zhang, Y. The efficacy of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PeerJ11, 10.7717/peerj.16137 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Lee, S., Oh, J. W., Park, K. M., Lee, S. & Lee, E. Digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. npj Digit. Med.6, 10.1038/s41746-023-00800-3 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Hosono, T, Niwa, Y & Kondoh, M Comparison of product features and clinical trial designs for the dtx products with the indication of insomnia authorized by regulatory authorities. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci.10.1007/s43441-024-00684-9 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Espie, C. A. et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of online cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia disorder delivered via an automated media-rich web application. Sleep35, 769–781 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritterband, L. M. et al. Effect of a web-based cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia intervention with 1-year follow-up: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry74, 68–75 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freeman, D. et al. The effects of improving sleep on mental health (OASIS): a randomised controlled trial with mediation analysis. Lancet Psychiatry4, 749–758 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Darden, M. et al. Cost-effectiveness of digital cognitive behavioral therapy (Sleepio) for insomnia: a Markov simulation model in the United States. Sleep44, 10.1093/sleep/zsaa223 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Stokes, E. A., Stott, R., Henry, A. L., Espie, C. A. & Miller, C. B. Quality-adjusted life years for digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (Sleepio): a secondary analysis. BJGP Open6, 10.3399/BJGPO.2022.0090 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Ferri, R. et al. Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy to treat insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS ONE11, 10.1371/journal.pone.0149139 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Ye, Y.-y et al. Internet-based cognitive–behavioural therapy for insomnia (ICBT-i): a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open6, e010707 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soh, H. L., Ho, R. C., Ho, C. S. & Tam, W. W. Efficacy of digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep. Med.75, 315–325 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai, H. J. et al. Effectiveness of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in young people: preliminary findings from systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pers. Med.12, 10.3390/jpm12030481 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Deng, W. et al. eHealth-based psychosocial interventions for adults with insomnia: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Med. Internet Res.25, e39250 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knutzen, S. M. et al. Efficacy of eHealth versus in-person cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: systematic review and meta-analysis of equivalence. JMIR Ment. Health11, e58217 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hasan, F. et al. Comparative efficacy of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sleep. Med. Rev.61, 101567 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Forma, F. et al. Network meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness of a prescription digital therapeutic for chronic insomnia to medications and face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy in adults. Curr. Med. Res. Opin.38, 1727–1738 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon, L. et al. Comparative efficacy of onsite, digital, and other settings for cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sci. Rep.13, 1929 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torous, J., Lipschitz, J., Ng, M. & Firth, J. Dropout rates in clinical trials of smartphone apps for depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord.263, 413–419 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Batterham, P. J. et al. Sleep-specific outcomes attributable to digitally delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in adults with insomnia and depressive symptoms. Behav. Sleep. Med.22, 410–419 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chan, C. S. et al. Treating depression with a smartphone-delivered self-help cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a parallel-group randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Med.53, 1799–1813 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hinterberger, A., Eigl, E. S., Schwemlein, R. N., Topalidis, P. & Schabus, M. Investigating the subjective and objective efficacy of a cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I)-based smartphone app on sleep: a randomised controlled trial. J. Sleep. Res.33, e14136 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kallestad, H. et al. Mode of delivery of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia: a randomized controlled non-inferiority trial of digital and face-to-face therapy. Sleep44, 10.1093/sleep/zsab185 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Mason, E. C. et al. Co-occurring insomnia and anxiety: a randomized controlled trial of internet cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia versus internet cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety. Sleep46, 10.1093/sleep/zsac205 (2023) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Sato, D. et al. Effectiveness of unguided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy and the three good things exercise for insomnia: 3-arm randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res.24, e28747 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watanabe, Y. et al. Effect of smartphone-based cognitive behavioral therapy app on insomnia: a randomized, double-blind study. Sleep46, 10.1093/sleep/zsac270 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Yang, C.-M. et al. Can adding personalized rule-based feedback improve the therapeutic effect of self-help digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in young adults? Sleep. Med.107, 36–45 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou, E. S. et al. Effect of culturally tailored, internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in black women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry79, 538–549 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ong, A. D., Kim, S., Young, S. & Steptoe, A. Positive affect and sleep: a systematic review. Sleep. Med. Rev.35, 21–32 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manber, R. et al. CBT for insomnia in patients with high and low depressive symptom severity: adherence and clinical outcomes. J. Clin. Sleep. Med.7, 645–652 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ritterband, L. M. et al. Efficacy of an internet-based behavioral intervention for adults with insomnia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry66, 692–698 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ritterband, L. M. et al. Initial evaluation of an Internet intervention to improve the sleep of cancer survivors with insomnia. Psycho Oncol.21, 695–705 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheng, P. et al. Efficacy of digital CBT for insomnia to reduce depression across demographic groups: a randomized trial. Psychol. Med.49, 491–500 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Espie, C. A. et al. Effect of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on health, psychological well-being, and sleep-related quality of life: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry76, 21–30 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Glozier, N. et al. Adjunctive Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia in men with depression: a randomised controlled trial. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry53, 350–360 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horsch, C. H. et al. Mobile phone-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a randomized waitlist controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res.19, e70 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kalmbach, D. A. et al. A randomized controlled trial of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in pregnant women. Sleep. Med.72, 82–92 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McGrath, E. R. et al. Sleep to lower elevated blood pressure: a randomized controlled trial (SLEPT). Am. J. Hypertens.30, 319–327 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Theadom, A. et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of on-line interventions to improve sleep quality in adults after mild or moderate traumatic brain injury. Clin. Rehabil.32, 619–629 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Felder, J. N., Epel, E. S., Neuhaus, J., Krystal, A. D. & Prather, A. A. Efficacy of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of insomnia symptoms among pregnant women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry77, 484–492 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lancee, J., van den Bout, J., van Straten, A. & Spoormaker, V. I. Internet-delivered or mailed self-help treatment for insomnia?: a randomized waiting-list controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther.50, 22–29 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lancee, J., van den Bout, J., Sorbi, M. J. & van Straten, A. Motivational support provided via email improves the effectiveness of internet-delivered self-help treatment for insomnia: a randomized trial. Behav. Res. Ther.51, 797–805 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vedaa, Ø. et al. Effects of digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia on insomnia severity: a large-scale randomised controlled trial. Lancet Digit. Health2, e397–e406 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tarricone, R., Petracca, F. & Weller, H. M. “Towards harmonizing assessment and reimbursement of digital medical devices in the EU through mutual learning”. NPJ Digit. Med.7, 268 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Administration, U. S. F. D. Digital Health Software Precertification (Pre-Cert) Pilot Program, https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center-excellence/digital-health-software-precertification-pre-cert-pilot-program.

- 70.van Straten, A. et al. Cognitive and behavioral therapies in the treatment of insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep. Med. Rev.38, 3–16 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thorndike, F. P. et al. Effect of a prescription digital therapeutic for chronic insomnia on post-treatment insomnia severity, depression, and anxiety symptoms: results from the real-world DREAM study. Front Psychiatry15, 1450615 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schmidt, L., Pawlitzki, M., Renard, B. Y., Meuth, S. G. & Masanneck, L. The three-year evolution of Germany’s Digital Therapeutics reimbursement program and its path forward. NPJ Digit. Med.7, 139 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schwartz, D. G. et al. Apps don’t work for patients who don’t use them: towards frameworks for digital therapeutics adherence. Health Policy Technol.13, 10.1016/j.hlpt.2024.100848 (2024).

- 74.Vincent, N., Lewycky, S. & Finnegan, H. Barriers to engagement in sleep restriction and stimulus control in chronic insomnia. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol.76, 820–828 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maurer, L. F., Schneider, J., Miller, C. B., Espie, C. A. & Kyle, S. D. The clinical effects of sleep restriction therapy for insomnia: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep. Med. Rev.58, 101493 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Higgins J. P. T. et al. (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5 (updated August 2024), https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (2024).

- 77.Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ372, n71 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cuijpers, P., Weitz, E., Cristea, I. A. & Twisk, J. Pre-post effect sizes should be avoided in meta-analyses. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci.26, 364–368 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Neyeloff, J. L., Fuchs, S. C. & Moreira, L. B. Meta-analyses and Forest plots using a microsoft excel spreadsheet: step-by-step guide focusing on descriptive data analysis. BMC Res. Notes5, 52 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Batterham, P. J. et al. Trajectories of change and long-term outcomes in a randomised controlled trial of internet-based insomnia treatment to prevent depression. BJPsych Open3, 228–235 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Christensen, H. et al. Effectiveness of an online insomnia program (SHUTi) for prevention of depressive episodes (the GoodNight Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry3, 333–341 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hagatun, S. et al. The short-term efficacy of an unguided internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia: a randomized controlled trial with a six-month nonrandomized follow-up. Behav. Sleep. Med.17, 137–155 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kyle, S. D. et al. The effects of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on cognitive function: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep43, 10.1093/sleep/zsaa034 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Lorenz, N., Heim, E., Roetger, A., Birrer, E. & Maercker, A. Randomized controlled trial to test the efficacy of an unguided online intervention with automated feedback for the treatment of insomnia. Behav. Cogn. Psychother.47, 287–302 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data collected and used in this meta-analysis can be requested from corresponding author.