Abstract

Elevated arachidonic acid metabolism (AAM) has been linked to the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). However, the specific role of AAM-related genes (AAMRGs) in NAFLD remains poorly understood. To investigate the involvement of AAMRGs in NAFLD, this study analyzed datasets GSE89632 and GSE135251 from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB). Differential expression analysis revealed 2256 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between NAFLD and control liver tissues. Cross-referencing these DEGs with AAMRGs identified nine differentially expressed AAMRGs (DE-AAMRGs). Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) and univariate logistic regression analyses pinpointed five biomarkers—CYP2U1, GGT1, PLA2G1B, GPX2, and PTGS1—demonstrating significant diagnostic potential for NAFLD, as validated by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. These biomarkers were implicated in pathways related to AAM and arachidonate transport. An upstream regulatory network, involving transcription factors (TFs) and MicroRNAs (miRNAs), was constructed to explore the regulatory mechanisms of these biomarkers. In vivo validation using a NAFLD mouse model revealed liver histopathological changes, and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and western blot (WB) analyses confirmed the upregulation of biomarker expression, particularly PTGS1, in NAFLD. The bioinformatic analysis identified five AAM-related biomarkers, enhancing the understanding of NAFLD pathogenesis and offering potential diagnostic targets.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-92972-z.

Keywords: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Arachidonic acid metabolism, Bioinformatic, GEO

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Biomarkers

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is an acquired metabolic disorder marked by hepatic fat accumulation due to metabolic stress1. It is strongly linked to obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and insulin resistance, and is often considered a hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome2. NAFLD evolves through four distinct stages: hepatic steatosis (fat accumulation), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis, and cirrhosis3. The early stage is characterized by hepatic steatosis or non-alcoholic fatty liver. Chronic inflammation then triggers the onset of fibrosis, leading to the replacement of functional hepatocytes with scar tissue. Cirrhosis, the most advanced stage of NAFLD, involves extensive structural and functional impairments of hepatocytes4. NAFLD has become the leading cause of liver-related mortality globally, which impose a significant healthcare burden. Despite its growing impact, NAFLD remains underrecognized as a major chronic disease5, with limited progress in diagnostic and therapeutic advancements. Further research is essential to deepen our understanding of the disease and to identify more effective diagnostic and treatment strategies.

Arachidonic acid is a polyunsaturated fatty acid abundantly present in mammalian cell membranes, which dissociates from the membranes upon activation of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) by nerve signals. Free arachidonic acid can undergo metabolic transformations via multiple pathways (cytochrome P450 (CYP450), lipoxygenase, and cyclooxygenase (COX) pathways) to generate hydroxyeicosapentaenoic acids, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, prostaglandins (PGs), and other active metabolites6. Early research indicated that NAFLD progression was associated with arachidonic acid metabolism (AAM). Studies have found that PLA2 is genetically altered to reduce liver steatosis caused by high fat diets7. CYP450 family enzymes contribute to the generation of anti-inflammatory epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, hydroxyicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) and reactive oxygen species, which are thought to be the drivers of steatohepatitis8,9. 5- lipoxygenase-derived leukotrienes are involved in the pathogenesis of NAFLD, and increased 5-lipoxygenase derivatives are associated with severity of liver disease10,11. The COX pathway participates in the pathogenesis of NAFLD by acting on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, which is associated with insulin resistance and liver steatosis12. However, the potential regulatory mechanisms of AAM in NAFLD are not yet understood, and the potential role of AAM as a diagnostic and therapeutic targets for NAFLD requires further study. In the bioinformatics analysis, mendelian randomization analysis demonstrated that elevated arachidonic acid levels are potentially associated with an increased risk of NAFLD13. RNA-Seq analysis indicated that CYP450 family plays a pivotal role in lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, and inflammation in NAFLD, suggesting that CYP450 enzymes may serve as potential diagnostic and therapeutic targets for NAFLD14. Furthermore, AAM may enhance the prognosis of breast cancer patients by promoting immune responses15. Additionally, AAM-related genes (AAMRGs) play a significant role in immune regulation and oxidative stress in coupes with repeated implantation failure, potentially contributing to the occurrence of embryo implantation failure16. However, there are no bioinformatics studies on AAMRGs in NAFLD, and our study fills a gap in current research.

The current study utilized transcriptomic data and bioinformatics tools to identify key genes involved in AAM in NAFLD, with subsequent validation of biomarker expression via quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and western blot (WB) assays in livers of NAFLD mouse models. Additionally, the investigation examined the underlying mechanisms of these biomarkers in NAFLD, providing potential targets for diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in the treatment of NAFLD.

Results

Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and differentially expressed AAMRGs (DE-AAMRGs)

A total of 2256 DEGs were identified between NAFLD and control (CTL) samples (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Material 1). Intersection analysis of DEGs and AAMRGs yielded 9 DE-AAMRGs (Fig. 1b). These DE-AAMRGs were significantly associated with Gene Ontology (GO) terms related to fatty acid metabolic processes (biological process, BP), arachidonic acid metabolic processes (BP), nuclear outer membrane (cellular component, CC), azurophil granule lumen (CC), calcium-dependent phospholipase A2 activity (molecular function, MF), and lipase activity (MF), among others (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)17 pathway analysis revealed enrichment in pathways such as alpha-linolenic acid metabolism, linoleic acid metabolism, fat digestion and absorption, ether lipid metabolism, glycerophospholipid metabolism, and fatty acid degradation (Fig. 1d). The resulting protein-protein interaction (PPI) network consisted of 9 nodes and 20 edges, including interactions between GGT1-GPX2, PLA2G1B-PTGES2, and PLA2G10-PLA2G3, among other pairs (Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1.

Identification of DEGs and DE-AAMRGs. (a-1) Heatmap of expression of downregulated Top10 differentially expressed genes on NAFLD and CTL samples. Gradually higher expression with blue to red colour. (a-2) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes between NAFLD and CTL samples. Red dots represent upregulated genes, blue dots represent downregulated genes, and grey dots represent genes with no significant difference or small fold changes. The figure is labelled for up- and down-regulation of each of the Top10 genes. (b) Venn diagram of DEGs and DE-AAMRGs. (c-1) GO-BP enrichment treemap for DE-AAMRGs. (c-2) GO-CC enrichment treemap for DE-AAMRGs. (c-3) GO-MF enrichment treemap for DE-AAMRGs. (d) KEGG pathway enrichment treemap of DE-AAMRGs. (e) PPI network of DE-AAMRG.

CYP2U1, GGT1, PLA2G1B, GPX2, and PTGS1 could commendably diagnose NAFLD as biomarkers

When λ = 0.04064, the error rate was minimized, and five genes were identified at this threshold (Fig. 2a). Through univariate logistic analysis of these genes, five biomarkers—CYP2U1, GGT1, PLA2G1B, GPX2, and PTGS1—were ultimately selected. Among them, GGT1 emerged as a risk factor (odds ratio (OR) > 1), while the others acted as protective factors (OR < 1) (Fig. 2b). Expression patterns of CYP2U1 and PTGS1 were consistent across the GSE89632 and GSE135251 datasets, with both showing elevated expression in NAFLD samples compared to CTL samples (Fig. 2c). The area under the curve (AUC) values for CYP2U1 (AUC = 0.891), GGT1 (AUC = 0.849), PLA2G1B (AUC = 0.821), GPX2 (AUC = 0.760), and PTGS1 (AUC = 0.763) all exceeded 0.7, suggesting their robust predictive capacity for NAFLD (Fig. 2d). The diagnostic performance of these biomarkers was further confirmed in the GSE135251 dataset (Fig. 2e). Furthermore, correlation analyses of biomarkers across all samples, NAFLD, and CTL groups in GSE89632 revealed both consistencies and discrepancies. For example, PLA2G1B and CYP2U1 were significantly negatively correlated across all sample types (all samples: Cor = -0.65, P < 0.05; NAFLD samples: Cor = -0.38, P < 0.05; CTL samples: Cor = -0.80, P < 0.05). In contrast, a notable negative correlation between CYP2U1 and PTGS1 was observed in NAFLD samples (Cor = -0.38, P < 0.05), whereas a positive correlation was evident in CTL samples (Cor = 0.50, P < 0.05) (Fig. 2f). In addition, the nomogram constructed on the basis of five biomarkers showed good predictive ability (Supplementary Material 7 and Supplementary Material 9). The AUC value of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve exceeded 0.7, and the decision curve analysis (DCA) curve showed that the net benefit level of the model was higher than the prediction of individual biomarkers (Supplementary Figure S1b-1c). These results further confirmed the reliability of the prediction model.

Fig. 2.

Performance of five key biomarkers (CYP2U1, GGT1, PLA2G1B, GPX2, PTGS1) in the diagnosis of NAFLD. (a-1,2) LASSO regression analysis to screen for signature genes. (b) Logistic regression forest plot for key genes. (c-1) Scatter box plot of key gene expression in GSE89632. (c-2) Scatter box plot of key gene expression in GSE135251. (d) ROC curve for key genes in GSE89632. (e) ROC curve for key genes in GSE135251. (f-1) Key gene correlations in all samples in GSE89632. (f-2) Key gene correlations in CTL samples in GSE89632. (f-3) Key gene correlations in NAFLD samples in GSE89632.

The biomarkers were related to AAM pathways

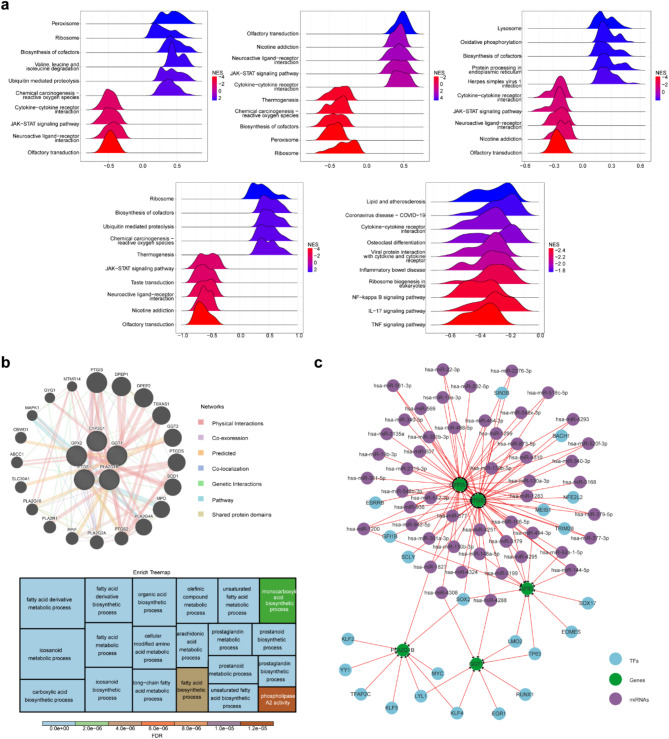

The biological functions and pathways associated with the biomarkers were explored using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), which identified the enrichment of CYP2U1 in KEGG pathways such as AAM, pyruvate metabolism, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. GGT1 was linked to KEGG pathways including steroid hormone biosynthesis, unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis, and fatty acid degradation. PLA2G1B was involved in pathways like the sphingolipid signaling pathway, inositol phosphate metabolism, and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction. GPX2 participated in cholesterol metabolism, hematopoietic cell lineage, and sphingolipid signaling pathways. PTGS1 was associated with lipid metabolism, atherosclerosis, osteoclast differentiation, and IL − 17 signaling pathways (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Material 2–6). Furthermore, biomarkers, together with other genes in the GeneMANIA network, contributed to processes such as AAM, arachidonate transport, and fatty acid derivative metabolism (Fig. 3b). Ultimately, the TF-miRNA-gene regulatory network, consisting of 77 nodes and 119 edges, included reciprocal relationships such as SOX17-GPX2, hsa-miR-607-CYP2U1, and hsa-miR-4251-PTGS1 (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Correlation of biomarkers with arachidonic acid metabolic pathways. (a) Enrichment ridge map of KEGG for key genes. (b-1) Co-expression network of key genes. (b-2) Treemap of key gene co-expression network functions. (c) TF-miRNA-gene regulatory network of key genes.

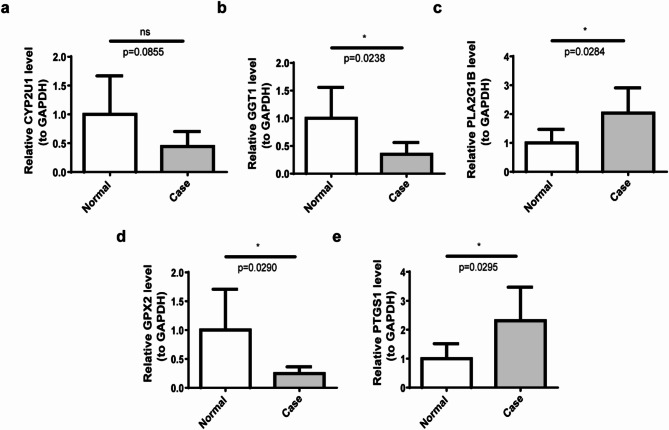

qRT-PCR and WB validation revealed that the expression trend of PTGS1 was consistent with both datasets

The expression of five biomarkers (CYP2U1, GGT1, PLA2G1B, GPX2, and PTGS1) was assessed in NAFLD samples through qRT-PCR, with comparisons made to CTL samples. The data revealed a significant reduction in the expression of GPX2 and GGT1 in NAFLD relative to CTL samples, while PLA2G1B and PTGS1 showed increased expression. No significant difference in CYP2U1 expression was observed between the two groups (Fig. 4a–e). Notably, the expression trend of PTGS1 mirrored that in the two datasets, indicating its central role among the biomarkers and suggesting its potential involvement in the pathogenesis and progression of NAFLD. WB analysis further confirmed the upregulation of all five biomarkers in the NAFLD group (Fig. 5, Supplementary Material 8).

Fig. 4.

Expression validation of five biomarkers. (a) Expression analysis of CYP2U1 in the case and normal groups. (b) Expression analysis of GGT1 in the case and normal groups. (c) Expression analysis of PLA2G1B in the case and normal groups. (d) Expression analysis of GPX2 in the case and normal groups. (e) Expression analysis of PTGS1 in the case and normal groups. ns: no significance; *: p < 0.05.

Fig. 5.

Five biomarkers in mice in the control and NAFLD groups in protein level. ***: p < 0.001; ****: p < 0.0001.

The liver of the NAFLD mice exhibited a notable infiltration of fat and inflammatory cells, along with a deposition of collagen

Following the establishment of the NAFLD mouse model, all mice in the NAFLD cohort exhibited increased body weight compared to the control group (Fig. 6a,b), with a significant difference observed between the two groups by week 12. Additionally, the livers of NAFLD mice appeared visibly lighter in color (Fig. 6c). Biochemical analysis of serum samples revealed markedly elevated Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) and Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) levels in the NAFLD group, with significant inter-group differences (Fig. 6d). Histopathological examination of liver tissue confirmed the presence of pronounced hepatocyte edema and necrosis, cytoplasmic disintegration, inflammatory cell infiltration, lipid droplet accumulation, and collagen deposition in NAFLD mice (Fig. 6e-g).

Fig. 6.

The NAFLD mouse liver exhibits significant fat infiltration, inflammatory cell infiltration, and collagen deposition. (a) Liver weight growth curves of mice in control and NAFLD groups. (b) Differences in liver weight between control and NAFLD mice. *: p < 0.05. (c) Comparison of liver conditions in control and NAFLD mice. (d) Results of lipid analysis in control and NAFLD groups. *: p < 0.05. (e) HE staining results of liver cells in mice from the control group and the NAFLD group. (f) Oil Red O staining results of liver cells in mice from the control group and the experimental group. ***: p < 0.001. (g) Changes in collagen fibres in liver tissue were detected using Masson staining.

Discussion

NAFLD is the most prevalent cause of chronic liver disease, with a reported worldwide prevalence of 25%5. Late-stage NAFLD can lead to liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma4,5. Despite extensive research, the intrinsic mechanism of NAFLD is complex and not fully understood2, which has resulted in a lack of reliable noninvasive diagnostic tools, dynamic biomarkers and effective treatment drugs18. Therefore, identifying a validated biomarker for NAFLD is crucial for developing individual treatment strategies. Early research indicated that NAFLD progression was associated with AAM7, while the specific pathogenesis and regulation of AAM in NAFLD are not clear. Therefore, our study aimed to investigate the potential molecular mechanisms of AAMRGs in NAFLD, offering novel biomarkers for diagnostic and therapeutic interventions against NAFLD.

To date, bioinformatic analyses of AAMRGs in NAFLD have not been reported. In the present study, we systematically investigated the differential expression of AAMRGs between NAFLD and CTL samples enrolled from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), and we finally identified nine DE-AAMRGs. The difference in AAMRGs between NAFLD and the CTL sample indicated that AAMRGs may participate in the occurrence and progression of NAFLD. DE-AAMRGs correlation analysis indicated a relatively close correlation between DE-AAMRGs. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses indicated the nine DE-AAMRGs were significantly involved in the AAM, which indicated the DE-AAMRGs are key genes of AAM in NAFLD.

In this study, we employed least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) and univariate logistic analysis to identify five biomarkers (CYP2U1, GGT1, PLA2G1B, GPX2, and PTGS1) with an AUC value of all more than 0.7 in the training sets, which indicating that they had excellent ability to predict the risk of NAFLD. We also constructed a nomogram and DCA curve, which further verified the reliability of the prediction model. Therefore, we conclude that the five biomarkers are reliable and robust biomarkers for the diagnosis of NAFLD.

CYP2U1, a member of the CYP450 enzyme family, catalyzes the hydroxylation of both arachidonic acid and structurally similar long-chain fatty acids to a series of oxygenated products19. CYP2U1- derived 20-HETE can contributes to inflammation, oxidative stress20. Recent studies have reported an upregulation of CYP2U1 in NAFLD, suggesting that CYP2U1 may play a role in drug metabolism in NAFLD patients, thereby influencing drug efficacy and drug dose adjustments21. In this study, WB analysis confirmed elevated CYP2U1 expression in NAFLD samples, which is consistent with recent study. Therefore, an in-depth investigation into the specific functions of CYP2U1 in NAFLD could facilitate the optimization of individualized pharmacotherapy for NAFLD patients. Arachidonic acid-derived metabolites, including cysteinyl leukotrienes (leukotrienes C4, leukotrienes D4 and leukotrienes E4), are implicated in promoting inflammation and oxidative stress22. Gamma-glutamyl Transferase 1 (GGT1), a cell surface enzyme involved in the hydrolysis of γ-glutamyl compounds, plays a critical role in glutathione metabolism and the conversion of leukotrienes C4 to leukotrienes D423. GGT is widely recognized as a marker of oxidative stress24. Numerous studies have established a link between GGT and the increased risk of metabolic syndrome, obesity, and diabetes25,26. This study is the first to identify a relationship between GGT1 and NAFLD. qRT-PCR analysis revealed a significant reduction in GGT1 expression in NAFLD, whereas WB results indicated an increase in GGT1 levels in the disease. This discrepancy suggests that GGT1 protein may accumulate in the liver due to impaired protein degradation pathways or post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. Our experimental findings imply that GGT1 may play a significant role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. However, its precise molecular mechanisms and biological functions require further investigation. Future research should focus on elucidating the regulatory mechanisms, intracellular localization, and stability of GGT1 in NAFLD, as well as its association with oxidative stress and inflammatory responses. PLA2G1B, a member of the PLA2 family, hydrolyzes phospholipids into fatty acids and lysophospholipids27. Several studies have demonstrated that PLA2G1B plays a role in diet-induced hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diabetes27–29. The present study reveals, for the first time, that PLA2G1B expression is upregulated in NAFLD samples. Previous research has demonstrated that PLA2G1B can promote inflammation during colitis development, and its inactivation can enhance epithelial repair and mitigate inflammatory responses by increasing intestinal stem cell numbers30. Given the frequent association between NAFLD and hepatic inflammation, this finding implies that down-regulating PLA2G1B expression might reduce inflammation and aid in NAFLD treatment. GPX2, an antioxidant enzyme belonging to the Glutathione Peroxidase family, primarily eliminates hydrogen peroxide and organic peroxides, thereby protecting cell membranes from oxidative stress31. Recent study has shown elevated GPX2 expression in NAFLD samples32 signifies the liver’s response to oxidative stress and may be associated with the progression of NAFLD. WB data in our study further corroborated the increased expression of GPX2 in NAFLD samples. Additional research has indicated that GPX2 may play a pivotal role in mediating oxidative stress, while exposure to 2,4-D may contribute to the development of NAFLD by modulating antioxidant genes, thereby influencing hepatic oxidative stress levels. Oxidative damage to the liver is recognized as one of the key pathological mechanisms underlying NAFLD33. Consequently, future investigations should delve deeper into the relationship between GPX2 and NAFLD to provide novel insights for therapeutic strategies. PTGS1 (COX-1) catalyzes the synthesis of PGs and related compounds from arachidonic acid34. Increased PGs production disrupts lipid metabolism35,36. Furthermore, PTGS1, as an oxidative lipid metabolism gene implicated in the response to Omega-3 fatty acids, may play a crucial role in the inflammatory response. Alterations in its expression could influence the production of oxidative lipids, including PGs, thereby potentially impacting inflammation and immune responses37. Recent studies have reported significant upregulation of PTGS1 expression in liver tissues from rodents with high-fat-diet-induced NAFLD35, aligning with the current results. Furthermore, the PTGS1/PTGS2 inhibitor indomethacin and the PTGS1 inhibitor SC-560 have been shown to reduce fluoxetine-induced lipid accumulation in the liver38. Therefore, the substantial upregulation of PTGS1 expression appears to be closely associated with the progression of NAFLD. Research into PTGS1 may offer a novel therapeutic perspective for the management of NAFLD.

In this study, a co-expression network of the five biomarkers was constructed using GeneMANIA, revealing their involvement, along with other genes in the network, in processes such as AAM, arachidonate transport, and fatty acid derivative metabolism. Endogenous arachidonic acid generation primarily occurs through the release of arachidonic acid from cell membrane phospholipids, a process catalyzed by enzymes of the PLA2 superfamily. Free arachidonic acid is then subjected to various metabolic pathways, yielding numerous derivatives with diverse biological functions6. Exposure of arachidonic acid to oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species, and reactive nitrogen species leads to its oxidation, producing isoprostanes and nitroeicosatetraenoic acids39,40. Several arachidonic acid derivatives are implicated in chronic inflammation, which plays a central role in the development and progression of NAFLD7,41. PLA2G1B is a member of the PLA2 enzyme family, while CYP2U1, a CYP450 enzyme, catalyzes the hydroxylation of arachidonic acid19. PTGS1 (COX-1) is responsible for the conversion of arachidonic acid into PGs and related compounds34. Both GGT1 and GPX2 are involved in oxidative stress regulation24,31. These findings indicated CYP2U1, GGT1, PLA2G1B, GPX2, and PTGS1 play essential roles in AAM, aligning with the results of GeneMANIA network analysis. Additionally, the GeneMANIA network analysis revealed that the five genes are also involved in fatty acid derivative metabolism. The fatty acids undergone esterification to form triglycerides, which are either stored as lipid droplets or packaged into very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) for secretion into the bloodstream. Hepatic steatosis arises when triglyceride accumulation within hepatocytes surpasses the capacity of VLDL synthesis, leading to further triglyceride depletion from VLDL, which then converts into low-density lipoprotein (LDL)42. In addition, the fatty acid-derived hydroperoxides are associated with oxidative stress43. Previous studies found that CYP2U1 catalyzes the conversion of long-chain fatty acids into oxygenated products19. GGT, present in arterial atheromatous plaques, enhances LDL oxidation through redox reactions44. PLA2G1B hydrolyzes phospholipids into fatty acids and lysophospholipids, which in turn stimulate hepatic VLDL production27. PTGS1 is a key enzyme in PGs synthesis. The PGs, as bioactive compounds with pleiotropic effects, could diminish the secretion of hepatic VLDL secretion34,45. GPX2 reduces fatty acid-derived hydroperoxides43. Collectively, CYP2U1, GGT1, PLA2G1B, GPX2, and PTGS1 are critical for fatty acid derivative metabolism.

MiRNAs and TFs are key gene regulators involved in various critical cellular processes. MiRNAs modulate gene expression at the posttranscriptional level, while TFs regulate transcription at the transcriptional level46. In this study, a TF-miRNA-gene regulatory network consisting of 77 nodes and 119 edges was constructed, including reciprocal interactions such as SOX17-GPX2, hsa-miR-19a-3p-CYP2U1, and hsa-miR-144-5p-PTGS1. Recent research has identified SOX17 as a target of dehydrovomifoliol in NAFLD treatment47. Additionally, miR-19a-3p has been shown to be dysregulated in the serum of NASH patients48, and miR-144-5p expression is reduced in NAFLD patients49. This indicates that these MiRNAs and TFs are likely to play a crucial role in the NAFLD progression. The interactions uncover potential gene regulatory mechanisms and offer novel molecular targets for the treatment of NAFLD.

This study identifies five potential biomarkers of AAM (CYP2U1, GGT1, PLA2G1B, GPX2, and PTGS1) with promising diagnostic potential. Additionally, a network of associated TF-miRNA-gene pathways is constructed. The findings enhance the understanding of the distinct relationship between AAM and NAFLD. Furthermore, they suggest that further investigation into AAM could reveal therapeutic targets and biomarkers for NAFLD patients. However, several limitations exist. Firstly, while the animal models replicate the NAFLD gene expression profile, additional liver tissue samples from both NAFLD patients and healthy controls are required for more comprehensive functional studies. Secondly, prospective clinical trials and more complex molecular experiments are needed to validate the mechanisms of action of the five AAMRGs.

Methods

Sources of data

Datasets GSE89632 and GSE135251 were extracted through GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds), where GSE89632 (Platform: GPL14951; Chip data) included 39 NAFLD liver tissue samples (20 simple steatosis and 19 non-alcoholic steatohepatitis) and 24 CTL samples, the GSE135251 (Platform: GPL18573; High-throughput data) contained 31 NAFLD liver tissue samples (15 simple steatosis and 16 non-alcoholic steatohepatitis) and 14 CTL samples. Then, totally 61 AAMRGs were yielded via Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp). In addition, in order to deal with batch effects, the distribution of data from different batches was first observed through box-and-line plots or clustered heat maps. If there were differences, the significance of the batch effect was also determined with the aid of Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which provided quantitative results. Finally, adjustments were made using the ComBat function of the sva package (version 3.50.0; date of use: 2023.7.4)50.

Differential expression analysis, enrichment analyses, and PPI analysis

Gene expression data from NAFLD and CTL samples in GSE89632 were extracted and analyzed to identify DEGs using the limma package (version 3.46.0; date of use: 2023.7.4)51, with thresholds set at |log2FC| > 0.5 and adj P < 0.05. |log2FC| > 0.5 indicated at least a twofold change in gene expression, and adj P < 0.05 was used to select statistically significant genes, reducing false positives and increasing reliability. The DEGs were then intersected with AAMRGs to generate a list of differentially expressed AAMRGs (DE-AAMRGs). In order to search the common functions and related pathways of DE-AAMRGs, GO analysis, including BP, CC, and MF, as well as KEGG enrichment, was performed using the clusterProfiler (version 4.4.4; date of use: 2023.7.8)52 and org.Hs.eg.db (version 3.15.0; date of use: 2023.7.8)53 R packages, with a significance threshold of adj P < 0.05. The adj P < 0.05 indicated that the results of enrichment analysis were significant. To investigate potential interactions among DE-AAMRGs, a PPI network was constructed using the STRING database (http://string-db.org), with a confidence score of 0.4.

Acquisition of biomarkers

To identify potential AAM-related biomarkers for diagnosing NAFLD, machine learning algorithms were employed. Initially, the LASSO logistic regression was applied to DE-AAMRGs using the glmnet package (version 4.1-6; date of use: 2023.7.14)54, generating gene coefficients and cross-validation error plots. LASSO is a shrinkage estimation method that produces strictly zero regression coefficients by minimizing the sum of squares of the residuals under the condition that the sum of the absolute values of the regression coefficients is constrained to yield an interpretable model. Subsequently, genes selected by LASSO underwent univariate logistic analysis to identify biomarkers (P < 0.05). P < 0.05 indicated that the relationship between the gene and the target variable was statistically significant. Also, potential risk factors (OR > 1) or protective factors (OR < 1) were identified by assessing the degree of influence of a single independent variable on the dependent variable. The expression patterns of these biomarkers between NAFLD and CTL samples were visualized using the Ggpubr package (version 0.4.0; date of use: 2023.7.4)55 in the GSE89632 and GSE135251 datasets.

Research on the acting mechanism of biomarkers on NAFLD

To assess diagnostic biomarkers, ROC curves were generated using the R pROC package (version 1.17.0.1; date of use: 2023.7.14)56 for GSE89632, with results subsequently validated in GSE135251 using the same methodology. Spearman correlations among biomarkers in the entire sample set, NAFLD samples, and CTL samples from GSE89632 were also analyzed. Next, in order to assess the overall ability of biomarkers to predict disease, nomogram was constructed based on biomarkers in all samples of the training set using the rms R package (version 6.5-0; date of use: 2025.1.25)57. Each biomarker corresponded to a score, and the total score was the sum of the scores of each factor, based on which the disease incidence was projected, with higher scores being associated with a higher risk of disease. Subsequently, the predictive performance of the model was further evaluated by ROC and DCA curves. GSEA was performed to explore biological functions and pathways associated with the biomarkers, utilizing the R package clusterProfiler (version 4.4.4; date of use: 2023.7.8)52, with the KEGG gene set (c2.cp.kegg.v7.4.symbols.gmt) as the background. Additionally, a co-expression network of biomarker interactions was constructed using GeneMANIA (http://genemania.org/). To predict miRNAs targeting these biomarkers, miRNA target prediction and functional annotation databases (miRDB, miRanda, and miCrocosm) were utilized, with the R package multiMiR (version 1.18.0; date of use: 2023.7.8)58 facilitating the intersection of predicted miRNAs. TFs targeting the biomarkers were predicted using the NetworkAnalyst database (https://www.networkanalyst.ca/), and a TF-miRNA-gene regulatory network was constructed based on these predictions using Cytoscape software (version 3.10.3; date of use: 2023.7.8)59.

NAFLD mouse model construction and sample collection

Efforts were made to minimize animal usage and alleviate pain and discomfort. Sample size was determined using the resource equation method60, and twelve 6-8-week-old male C57BL/6J mice (20–22 g) were obtained from Specific (Beijing) Biotechnology Co. Ltd. The mice were randomly assigned to two groups, NAFLD and control (6 mice each), via Microsoft Excel. Both groups were housed in a specific pathogen free -grade facility under a 12-hour light/dark cycle, with ad libitum access to food and water. After a 3-week acclimation period, the mice were fed regular and high-fat diets for 12 weeks in the control and NAFLD groups, respectively. Mice were monitored twice daily, and any deceased mice were promptly removed from the cages. Body weight was recorded weekly before sampling in both groups. Ultimately, twelve mice were included in the trials. Following a 12-hour fast, the mice were euthanized via intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital. Peripheral blood was collected through ocular removal (serum stored for liver function tests), and livers were harvested, weighed, and preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde or flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The Ethical Committee of Yunnan Beisite Biotechnology Co., Ltd. approved all animal procedures, which were conducted in compliance with institutional care standards and applicable regulations. The study adhered to the ARRIVE 2.0 guidelines.

Liver histopathologic staining

Tissues were fixed using a 4% paraformaldehyde solution, followed by dehydration, embedding, and sectioning. For HE staining, liver sections were baked, deparaffinized, and rehydrated through an alcohol gradient. They were then stained with hematoxylin (Servicebio, China) and eosin (G1108, Solarbio) for 5 min and 5–10 s, respectively, before being dehydrated, cleared, and mounted.

For MASSO staining, the protocol provided by the manufacturer (G1340, Solarbio) was followed. In brief, the MASSO-stained A-F solutions were applied for progressive staining at specified intervals, followed by dehydration and differentiation with 1% glacial acetic acid and anhydrous ethanol, then cleared and mounted with xylene.

For Oil Red O staining (G1262, Solarbio), liver tissues, preserved in liquid nitrogen, were immersed in a 1:1 mixture of 20 g L-1 sucrose and OCT embedding medium, then sectioned at -22 °C. The cryosections were rewarmed, fixed in Oil Red O fixative for 10–15 min, stained with modified Oil Red O stain for 10–15 min, re-stained with Mayer’s hematoxylin for 2 min, and finally mounted with glycerol gelatin.

RNA isolation and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

A total of 6 NAFLD and 6 CTL samples were collected from NAFLD and CTL mice, respectively. Following liver histopathological staining, total RNA was extracted from the 12 samples using TRIzol reagent (Ambion, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized via reverse transcription using the SureScript First-strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Servicebio, China). qPCR was conducted with a CFX Connect Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, USA). mRNA relative quantification was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method61. Primer sequences were provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequence information for qRT-PCR.

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| PLA2G1B F | GGGAGTGACCCCTTCTTGGA |

| PLA2G1B R | CTTGGCCTGGTCATAGCAGT |

| GPX2 F | ACTTCACCCAGCTCAACGAG |

| GPX2 R | ATGCTCGTTCTGCCCATTCA |

| CYP2U1 F | ACGGCAGCATCTTCAGCTTC |

| CYP2U1 R | TGCAAACACAACCCCCTTCT |

| GGT1 F | CCCAGAGATTGCCTGGAACAC |

| GGT1 R | TCCTGAAGGTCAAGGGAGGT |

| PTGS1 F | CTATCCATGCCAGCACCAGG |

| PTGS1 R | GCTTCTTCCCTGTGAGTACC |

| GAPDH F | CGAAGGTGGAGTCAACGGATTT |

| GAPDH R | ATGGGTGGAATCATATTGGAAC |

Western blot

Tissue samples were lysed with RIPA buffer (Servicebio, Wuhan) to extract proteins, and protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai). Proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes. After blocking to prevent nonspecific binding, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. Following extensive washing, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies at room temperature. After another round of washing, the membranes were visualized using ECL chemiluminescent substrate and a gel imager. Antibody details were provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Antibody information for Western blot.

| Name | Factory owners | Product number | Dilution level |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLA2G1B | Proteintech | 15843-1-AP | 1:1000 |

| GPX2 | Abcam | ab137431 | 1:1000 |

| CYP2U1 | Affinity | AF0686 | 1:2000 |

| GGT1 | Abcam | ab55138 | 1:1000 |

| PTGS1 | Proteintech | 13393-1-AP | 1:1000 |

| β-actin | Proteintech | 66009-1-Ig | 1:25000 |

| HRP-labelled goat anti-rabbit IgG | Servicebio | GB23303 | 1:3000 |

| HRP-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG | Servicebio | GB23301 | 1:5000 |

Statistical analysis

R software(version4.2.2) was the tool for all bioinformatics projects. GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) was used for statistical analysis. To compare data from various groups, the Wilcoxon test was performed (P < 0.05).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all individuals and organizations who supported and assisted us throughout this research. Special thanks to all study participants. In conclusion, we extend our thanks to everyone who has supported and assisted us along the way. Without your support, this research would not have been possible.

Author contributions

Jia Li designed the study, conducted the experiments and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Wei-Wei Su and Zhen-Li Wang contributed to the analysis of the data. Xiang-Fen Ji analyzed some data and involved in designing the study. Jing-Wei Wang analyzed some data. Kai Wang contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the (GEO)repository, (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds). The experimental data in this study is available from the corresponding author on request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fan, J. G. et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Update 2010: (Published in Chinese on Chinese Journal of Hepatology 2010; 18:163–166). J. Dig. Dis.12, 38–44 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buzzetti, E., Pinzani, M. & Tsochatzis, E. A. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism65, 1038–1048 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalasani, N. et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guideline by the American association for the study of liver diseases, American college of gastroenterology, and the American gastroenterological association. Hepatology55, 2005–2023 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark, J. M. The epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. J. Clin. Gastroenterol.40(Suppl 1), S5-10 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powell, E. E., Wong, V. W. & Rinella, M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet397, 2212–2224 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang, B. et al. Metabolism pathways of arachidonic acids: Mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther.6, 94 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonnweber, T., Pizzini, A., Nairz, M., Weiss, G. & Tancevski, I. Arachidonic acid metabolites in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci.19, 3285 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Theken, K. N. et al. Enalapril reverses high-fat diet-induced alterations in cytochrome P450-mediated eicosanoid metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab.302, E500–E509 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdelmegeed, M. A. et al. Critical role of cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) in the development of high fat-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol.57, 860–866 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puri, P. et al. The plasma lipidomic signature of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology50, 1827–1838 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horrillo, R. et al. 5-lipoxygenase activating protein signals adipose tissue inflammation and lipid dysfunction in experimental obesity. J. Immunol.184, 3978–3987 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsujimoto, S. et al. Nimesulide, a cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitor, suppresses obesity-related non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatic insulin resistance through the regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. Int. J. Mol. Med.38, 721–728 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, J. et al. Plasma phospholipid arachidonic acid in relation to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Mendelian randomization study. Nutrition106, 111910 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu, Y. et al. The role of cytochrome P450 in nonalcoholic fatty liver induced by high-fat diet: a gene expression profile analysis. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi.25(4), 285–290 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, W., Guo, X., Chen, C. & Li, J. The prognostic value of arachidonic acid metabolism in breast cancer by integrated bioinformatics. Lipids Health Dis.21(1), 103 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, Y. et al. Association of arachidonic acid metabolism related genes with endometrial immune microenvironment and oxidative stress in coupes with recurrent implantation failure. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol.93(1), e70044 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res.28(1), 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Younossi, Z. et al. Global perspectives on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology69(6), 2672–2682 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chuang, S. S. et al. CYP2U1, a novel human thymus- and brain-specific cytochrome P450, catalyzes omega- and (omega-1)-hydroxylation of fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem.279, 6305–6314 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waldman, M., Peterson, S. J., Arad, M. & Hochhauser, E. The role of 20-HETE in cardiovascular diseases and its risk factors. Prostaglandins Other Lipid. Mediat.125, 108–117 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen, L. et al. Transcriptomic profiling of hepatic tissues for drug metabolism genes in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A study of human and animals. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne)13, 1034494 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rink, C. & Khanna, S. Significance of brain tissue oxygenation and the arachidonic acid cascade in stroke. Antioxid Redox Signal.14, 1889–1903 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heisterkamp, N., Groffen, J., Warburton, D. & Sneddon, T. P. The human gamma-glutamyltransferase gene family. Hum. Genet.123, 321–332 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitfield, J. B. Gamma glutamyl transferase. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci.38, 263–355 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Middelberg, R. P. et al. Loci affecting gamma-glutamyl transferase in adults and adolescents show age × SNP interaction and cardiometabolic disease associations. Hum. Mol. Genet.21, 446–455 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morita, K. et al. A functional variant in the γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT)1 gene is associated with airflow obstruction in smokers. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med.53, e339–e341 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hollie, N. I. & Hui, D. Y. Group 1B phospholipase A₂ deficiency protects against diet-induced hyperlipidemia in mice. J. Lipid. Res.52, 2005–2011 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huggins, K. W., Boileau, A. C. & Hui, D. Y. Protection against diet-induced obesity and obesity- related insulin resistance in Group 1B PLA2-deficient mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab.283, E994-e1001 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labonté, E. D. et al. Group 1B phospholipase A2-mediated lysophospholipid absorption directly contributes to postprandial hyperglycemia. Diabetes55, 935–941 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haller, A. M., Wolfkiel, P. R., Jaeschke, A. & Hui, D. Y. Inactivation of group 1B phospholipase A(2) enhances disease recovery and reduces experimental colitis in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24(22), 16155 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh, A. et al. Glutathione peroxidase 2, the major cigarette smoke-inducible isoform of GPX in lungs, is regulated by Nrf2. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol.35, 639–650 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Day, K., Seale, L. A., Graham, R. M. & Cardoso, B. R. Selenotranscriptome network in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front. Nutr.8, 744825 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romualdo, G. R., Valente, L. C., de Souza, J. L. H., Rodrigues, J. & Barbisan, L. F. Modifying effects of 2,4-D and Glyphosate exposures on gut-liver-adipose tissue axis of diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.268, 115688 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Majed, B. H. & Khalil, R. A. Molecular mechanisms regulating the vascular prostacyclin pathways and their adaptation during pregnancy and in the newborn. Pharmacol. Rev.64(3), 540–582 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, W. et al. Genistein ameliorates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by targeting the thromboxane A (2) pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem.66, 5853–5859 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yokota, T. et al. Paracrine regulation of fat cell formation in bone marrow cultures via adiponectin and prostaglandins. J. Clin. Invest.109, 1303–1310 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berthelot, C. C. et al. Changes in PTGS1 and ALOX12 gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells are associated with changes in arachidonic acid, oxylipins, and oxylipin/fatty acid ratios in response to omega-3 fatty acid supplementation. PLoS One10(12), e0144996 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ayyash, A. & Holloway, A. C. Fluoxetine-induced hepatic lipid accumulation is mediated by prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 1 and is linked to elevated 15-deoxy-Δ(12,14) PGJ(2). J Appl. Toxicol.42, 1004–1015 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balazy, M. & Poff, C. D. Biological nitration of arachidonic acid. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol.2, 81–93 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fam, S. S. & Morrow, J. D. The isoprostanes: Unique products of arachidonic acid oxidation-a review. Curr. Med. Chem.10, 1723–1740 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dennis, E. A. & Norris, P. C. Eicosanoid storm in infection and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol.15, 511–523 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heeren, J. & Scheja, L. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and lipoprotein metabolism. Mol. Metab.50, 101238 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwarz, M. et al. Side-by-side comparison of recombinant human glutathione peroxidases identifies overlapping substrate specificities for soluble hydroperoxides. Redox Biol.59, 102593 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paolicchi, A. et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Human atherosclerotic plaques contain gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase enzyme activity. Circulation109, 1440 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nassir, F., Adewole, O. L., Brunt, E. M. & Abumrad, N. A. CD36 deletion reduces VLDL secretion, modulates liver prostaglandins, and exacerbates hepatic steatosis in ob/ob mice. J. Lipid. Res.54, 2988–2997 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hobert, O. Gene regulation by transcription factors and microRNAs. Science319, 1785–1786 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma, J., Li, R., Xu, F., Zhu, F. & Xu, X. Dehydrovomifoliol alleviates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease via the E2F1/AKT/mTOR Axis: Pharmacophore modeling and molecular docking study. Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med.2023, 9107598 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vulf, M. et al. Analysis of miRNAs profiles in serum of patients with steatosis and steatohepatitis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.9, 736677 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu, L., Sun, S. & Li, X. LncRNA ZFAS1 ameliorates injury led by non-alcoholic fatty liver disease via suppressing lipid peroxidation and inflammation. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol.47, 102067 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leek, J. T., Johnson, W. E., Parker, H. S., Jaffe, A. E. & Storey, J. D. The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics28(6), 882–883 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang, Y., Wang, Z., Sun, J. & Qian, Y. Identification of HCC subtypes with different prognosis and metabolic patterns based on mitophagy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.9, 799507 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics16, 284–287 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lowe, W. L. Jr. et al. Development of brain insulin receptors: Structural and functional studies of insulin receptors from whole brain and primary cell cultures. Endocrinology119, 25–35 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang, M. et al. An immune-related signature predicts survival in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol.9, 1314 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng, Q., Chen, X., Wu, H. & Du, Y. Three hematologic/immune system-specific expressed genes are considered as the potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of early rheumatoid arthritis through bioinformatics analysis. J. Transl. Med.19, 18 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robin, X. et al. pROC: An open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform.12, 77 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li, M. et al. Recognition of refractory Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia among Myocoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in hospitalized children: Development and validation of a predictive nomogram model. BMC Pulm Med.23(1), 383 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Robin, X. et al. The multiMiR R package and database: Integration of microRNA-target interactions along with their disease and drug associations. Nucleic Acids Res.42, e133 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res.13(11), 2498–2504 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Charan, J. & Kantharia, N. D. How to calculate sample size in animal studies?. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother.4(4), 303–306 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the (GEO)repository, (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds). The experimental data in this study is available from the corresponding author on request.