Abstract

Climate change and its impact on agricultural production due to the occurrence of extreme weather events appear to be more imminent and severe than ever, presenting a global challenge that necessitates collective efforts to mitigate its effects.There have been many practical and modelling studies so far to estimate the extent of climate change and possible damages on agricultural production, suggesting that water availability may decrease by 50% and agricultural productivity between 10 and 30% in the coming years ahead. Though there have been many studies to estimate the possible level of damage by the climate change on the production of many agricultural crops, no study has been conducted on the greenhouse tomato production. Therefore, this study was conducted to discover the effects of extreme high temperatures during the 2022–2023 growing season on the high-tech Turkish tomato greenhouse industry through a survey. The results showed that all greenhouses lost yield, ranging from 6 to 53%, with an average of 12.5%. Survey data revealed that irrigation and fog system water consumption increased by 29.32% and 31.42%, respectively, while fertilizer and electricity consumption rose by 23.66% and 19%. Some 76.5% of the growers declared difficulty in climate control, 11.7% reported tomato cluster losses with no information on yield loss, 9% experienced yield losses despite no cluster losses, and 61.7% observed a decline in tomato quality, leading to reduced sales prices. Considering these findings, it is recommended that greenhouses must adopt advanced climate control technologies, expand fog system capacities, and integrate renewable energy sources to enhance resilience against climate-induced challenges. Additionally, improving water-use efficiency, optimizing cooling strategies, using new and climate-resistant varieties and adjusting cropping seasons could help mitigate yield losses due to extreme temperatures. The study results offer extremely valuable insights into greenhouse production for researchers, technology developers, and policymakers for the mitigation of climate change effects and the development of more sustainable production systems.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-025-06307-1.

Keywords: Yield Loss, High Temperature, Sustainable greenhouse farming, Climate smart agriculture, Heat stress in greenhouse

Introduction

Changing climatic parameters, such as a potential rise in temperatures, changes in rainfall patterns, soil salinity expansion, increased carbon dioxide concentrations, unusual UV(ultraviolet) radiation levels and extreme weather events like droughts and floods are threatening global vegetable production. Climate change is expected to cause deleterious effects on crop yields and profits until the end of this century and more frequent occurrence of extreme weather and changes in rainfall patterns [18, 26–28] which demonstrated associations between already observed increased temperatures and extreme weather events recorded in the last decade, especially in the incidence of heat waves and intense precipitation. Backed by extensive primary research, there are widely reported warnings of considerable decreases in horticultural crop productivity when temperatures exceed critical physiological thresholds [4, 11, 15, 16, 22–25, 28, 30, 32, 42, 48–50, 55–57, 59, 64, 67, 72, 75, 76, 80, 81, 83].

Some studies suggest impacts could be profound, for example meta-analysis suggests for water alone a decrease in availability by 50% and increase in salinity of 3–4dS.m−1(deciSiemens per meter) could reduce yields of fruit crops more than 20% [14, 28, 30, 72, 75, 81]. However doubling carbon dioxide concentration might increase fruit crop yields by 38% [14, 23, 29, 74, 79]. Stevanović et al. [72] analysed different climate projections to look at distributional effects of high-end climate change impacts across geographic regions and across economic agents. Their findings suggest that climate change can have detrimental impacts on global agricultural welfare, especially after 2050, because losses in consumer surplus generally outweigh gains in producer surplus. The study results indicate that damage in agriculture may reach the annual loss of 0.3% of future total gross domestic product at the end of the century globally, assuming further opening of trade in agricultural products, which typically leads to interregional production shifts to higher latitudes, to escape from the detrimental affects of climate change.

Responses to changed temperatures are more complex. For tomatoes alone, substantial reviews [2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 13, 31, 32, 35, 39, 41, 43, 46, 54, 61, 64, 66, 70, 73, 77, 78] showed that core physiological processes driving growth and development on the plant each have separate and distinct responses. Thus warmer temperatures up to an optima advance plant and fruit development, but this could be at the expense of longer term growth, yield or fruit quality. From a farmers perspective the ultimate end goal is yield, the direct result of the integration of all these interconnected yet distinct plant process responses to temperature. There are numerous other studies looking deep into effects of increasing temperatures on the quality and other crop related issues, increase of diseases, pests and natural pest enemy populations due to climate change [7, 10, 19–21, 34, 36, 37, 60, 62, 69, 71, 84].

Whilst there is now substantive, multi-decadal, evidence of profound effects of climate on horticultural crops, much of the primary data demonstrating the responses has been from reductive experiments, studying in controlled environments perturbations to relatively few environmental or biological parameters. To understand responses at whole systems level much of these reductive data have been integrated into mechanistic crop models, such as for tomatoes TOMSIM(Tomato Simulation Model), TOMGRO(Tomato Growth Model), CropSyst(Cropping Systems Simulation Model) along with some climate estimation models [5, 14, 43, 65, 68]. Model forecasting power is now increasing as these bio-physical models are being integrated with more recent methods from the machine learning community. This includes applications of deep learning that can fine tune accuracy when there is remaining uncertainty with mechanistic model skill [85]. However, both reductive science even synthesized models have limits, in particular, they rarely consider how farmers will adapt their own agronomic behaviours to challenging environmental conditions, nor will they ever likely to have a full understanding of the vastly complex interactions which drive crop growth. The reality is that all horticultural crops are produced within a human-biophysical system. In horticultural science the human element of the system, what decisions growers make in different circumstances, is poorly understood and relatively unexplored. Understanding these behaviours is though critical in determining how climate change might affect horticultural productivity. Farmers will attempt to adapt to changed climate in extremely complex and diverse ways, and responses to these adaptations will be a function of the climate challenges and the bio-physical circumstances within any crop production system (greenhouse structures, heating systems, crop genetics, market prices etc.) [50–52]. These adaptive decisions may mitigate or even worsen the theoretical consequences of climate challenges. It therefore follows that to understand the effects of climate change on horticultural crop productivity requires significant data from multiple different farms who have been exposed to climate extremes. These empirical data will comprise both the farmers adaptive as well as the bio-physical responses of the cropping system. These data then need to be benchmarked to the outputs of current reductive science to provide confidence in any measured impacts. However, whilst there are large numbers of farms producing nearly all horticultural crops obtaining data on crop – climate responses is difficult to obtain and few large and “open” data sets are known.

An agricultural production system could be accepted resilient to climate change impacts in case its vulnerability to such changes is at the minimum level. This is the case in high-tech hydroponic greenhouses which use high level of climate control and production technologies, giving them a defence tool and flexibility against climate change risks better than other undercover or open field production systems. Therefore, they are expected to cope with a much better performance with the adverse affects of climate change on the crop growth and yield. Turkish soilless greenhouses could be classified as “Medium and High-technology Greenhouses(MTG and HTG)” according to the classification by Pardossi et al. [63]. First high-tech glass and plasic greenhouses in Türkiye were built by Dutch and French greenhouse builders some 40 years ago. Since then, though Dutch, French and Spanish greenhouse builders are still actively working in the Turkish market, many local greenhouse builders developed and now build most of the greenhouses in the country. Interestingly, most greenhouse investors are from out of the horticulture industry, usually powerful growers with a technology and quality culture from their other businesses, such as tourism, construction, and textile. In addition to this, as the country has a vast potential for geothermal energy (number 1 in Europe), most of the greenhouse investments are concentrated in geothermally rich areas recently. Türkiye has the largest geothermally heated greenhouse area in the world and approximately a quarter of the total high-tech greenhouses is geothermally heated. High-tech greenhouses have the highest capacity to resist the climate change, to be described as Climate Smart Agriculture(CSA) a description used by [26, 53, 58, 81].

Branthome [12] explained that total world tomato production increased 4% for both processing and fresh consumption in 2021 in comparison with previous growing season according to a FAO December 2022 report. In that report, it was indicated that Turkish production (13 million MT) doubled that of Italy, but was only one fifth of China(67 million MT), which alone accounted for nearly 36% of the total production in the world, and over the past decade (2011–2021), fresh tomato production continued to grow at a rate of above 2%, while production for processing tomato grew at an annual rate of 0.4%.

The Netherlands is the leader in production/m2 in the world, this country has been using the most advanced greenhouse technology and growing techniques for many years, in a way it is the number 1 country in fulfilling rules of CSA. Apart from the Netherlands, the highest productivity was achieved by Poland, Portugal, the USA and Morocco, ahead of Spain, Turkey and Brazil. It should be noted that the yield per ha values in the table do not distinguish between open field and undercover tomato production and these figures for hydroponic greenhouses are almost double that of the world average in many countries around the world. Taking the point from here, Turkey has about 50.000 ha of greenhouse area in total, excluding low- and high-level tunnels, of which, 2.200 ha is so-called modern or high-tech greenhouses, which is only 4.4% of the total greenhouse area [17].

According to data from the Turkish Statistical Institute [77] in 2024, Turkey’s tomato production accounted for 41.2% of the total production of vegetables cultivated for their fruits in 2021. This share increased by 2.3% in 2022, reaching 41.8%, making tomatoes the most produced vegetable among others. It is estimated that approximately 30% of Turkey’s tomato production comes from undercover cultivation, while 5% of the total production is exported [33, 44, 45, 47]

2022–2023 growing period was an extreme period where very hot spring–summer-autumn seasons prevailed in many parts of the country. Therefore, this study aimed at observing if these high-tech greenhouses, which could be accepted in the context of “CSA”, were capable of coping with the high temperatures stress created by the climate change and whether there was any yield loss in tomato production along with variations in the consumption of some other input elements such as water, fertiliser and electricity in different climate zones of Türkiye.

This study presents a novel dataset from 34 hydroponic tomato growers in Türkiye, covering a total greenhouse area of 326 hectares (approximately 17.5% of the total high-tech tomato production area), which was exposed to extreme summer temperatures during the 2022–2023 growing season. The study analyzes the impact of warm summer temperatures on yield and examines how extreme temperatures, as a likely consequence of climate change, may affect crop production in high-tech greenhouses. Given their advanced technological systems, high-tech greenhouses are expected to be the most climate-resilient growing environments.

Materials and method

Study area

Türkiye is a large country bridging Europe and Asia-Middle East, with various climate zones shown in Fig. 1 [38]. Türkiye’s modern greenhouse farms are mostly concentrated in regions 1C and 2. The survey forms filled in and sent back from the farms from different climate regions, mainly 1A, 1B, 1C, 2 and 3, where 2 and 1C having the largest shares, respectively. In climate zone 4 there is almost no modern greenhouse existence.

Fig. 1.

Climate zones of Turkey(adopted from [38]) and locations of greenhouse farms answering the survey(1A zone is warmer than 1B and 1C regions, 1B zone is at the heighest above sea level and coldest one, 1C zone is warmer than 1B but colder than 1A region. 1B and 1C zones are for crops growing for Summer or Summer-Spring season. Zone 4 is mostly rainy and cool, Zone 2 is warm in winter and hot in spring–summer, zone 3 climate is in between 2 and 4. Zones 1A, 2 and 3 are for winter production)

Gathering accurate data was a crucial aspect of this research to make reliable assessments of climate change impacts on high-tech greenhouse production in Türkiye. To achieve this, a survey was designed to evaluate the effects of climate change on greenhouse tomato production during the 2022–2023 growing season (some survey questions are presented in Table 1), because 2023 spring–summer seson was an extreme temperature season [82]. The survey was officially distributed to high-tech greenhouse growers through the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, and completed forms were collected via its regional branches before being forwarded to the corresponding author via email.

Table 1.

Some of the selected climate affect survey questions for high-tech greenhouse growers

| Survey Question | Response |

|---|---|

| 1.What is the location? | …? |

| 2.What is the company name(optional) | |

| 3.What is your total greenhouse area | …ha |

| 4.What is the type of your greenhouse? | □ glass □ polyethylene |

| 5.What are the side wall and top height? | …m …m |

| 6.Which one is the ventilation system of your greenhouse ? |

□ continuous double butterfly □ single arm |

| 7.Estimated ventilation rate of your greenhouse ? | …% |

| 8.What was the crop(for tomatoes) grown? | □ cluster □ cocktail □ cherry □ beef |

| 9.What was the growth media? | □ cocopeat □ rockwool □ perlite □ other(please specify…) |

| 10.What was the production type? | □ winter □ summer □ other(specify…) |

| 11.What are the technologies lacking? | … |

| 12.What is the installed fog system capacity? | …mL/m2h |

| 17.In what percentage has your irrigation water consumption increased compared to previous season? | …% |

| 18.In what percentage has your electricity consumption increased compared to previous season? | …% |

| 19.In what percentage has your fertiliser consumption increased compared to previous season? | …% |

| 20.In what percentage has your fog system water consumption increased compared to previous season? | …% |

| 21.Did you have difficulties in controlling the climate of the greenhouse compared to previous season? | □ yes □ no |

| 22.Have you lost some clusters in your tomato greenhouse compared to previous season?. If “yes”, how many? |

□ yes, …clusters lost □ no |

| 23.What was your tomato yield? | …kg/m2 |

| 24.What was your tomato yield in previous season? | …kg/m2 |

| 25.Have you observed climate-caused quality loss in tomatoes compared to previous season? | □ yes □ no |

| 26.Have you faced reduced sales price due to this? | □ yes □ no |

| 27.Can you explain possible causes of your yield loss with your own words? |

The incoming forms and data then were classified by listing all the answers to questions asked in excelsheet files and then coded for statistical analysis. The greenhouses with a size smaller than 1 ha, growing in soil, producing seedlings or young crops and with any crop other than tomato were eliminated from the listing to be able to focus solely on modern greenhouses tomato production. From the excel sheets(Supplementary Material 1), weighed means of water, fertiliser and electric consumption increases and yield decreases were calculated separately. Further, by using SPSS statistical program, histogram of answers and importance of some answers were checked.

Authors developed a method that could help understand the climate change affect on the crop production in general (they call this method as “Kürklü-Pearson method”). The method was an attempt to see whether there was a relationship between the temperature increase due to climate change and the yield losses declared by the growers from different parts of Türkiye. For this purpose, long years(changing between 10 and 92 years) means of temperature data of the locations which declared yield losses for 2022–2023 growing season and for 2021 were requested from the General Directorate of the State Meteorological Affairs of Türkiye (see Fig. 1 above and Table 2 below for climate zones). From the data, total number of days with temperatures over 30 °C for each year were extracted for the growing periods and used for analysis. For each district, percentage increase in the total number of days with temperatures above 30 °C between 2022–2023 growing season and 2021 were, where the climate data were appropriate, calculated. The percentage of increase in days over 30 °C versus yield loss was presented as a graph to indicate the relationship between global warming and yield loss for greenhouse tomatoes.

Table 2.

Survey localities, production types, coordinates, height above sea level and climate zone

| Location(District/City) | Production Season | Coordinates | Height above sea level(m) and Climate zone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bismil/Diyarbakır | Winter | 37.851708, 40.663921 | 548 (Climate zone 1A) |

| Ceyhan/Adana | Winter | 37.028931, 35.817807 | 29 (Climate zone 2) |

| Kozaklı/Nevşehir | Summer, Spring | 39.209699, 34.850977 | 1064 (climate zone 1C) |

| Diyadin/Ağrı | Summer | 39.539805, 43.671202 | 1938(Climate zone 1B) |

| Ergene/Tekirdağ | Summer | 41.244902, 27.761158 | 157(Climate zone 3) |

| Tarsus/Mersin | Winter | 36.916628, 34.895677 | 25(Climate zone 2) |

| Sarayköy/Denizli | Winter | 37.924112, 28.925474 | 162(Climate zone 2) |

| Merkez/Kırşehir | Summer | 39.146095, 34.160505 | 986(Climate zone 1C) |

| Bergama/İzmir | Winter | 39.118921, 27.177325 | 71(Climate zone 2) |

| Dikili/İzmir | Winter | 39.112371, 26.934484 | 8(Climate zone 2) |

| Salihli/Manisa | Winter | 38.486149, 28.139053 | 101(Climate zone 2) |

| Ahmetli/Manisa | Winter | 38.516242, 27.935863 | 89(Climate zone 2) |

| Manavgat/Antalya | Winter | 36.786529, 31.446838 | 9(Climate zone 2) |

| Sandıklı/Afyonkarahisar | Summer, Spring | 38.464900, 30.269398 | 1094(Climate zone 1C) |

| Çobanlar/Afyonkarahisar | Summer, Spring | 38.701527, 30.781546 | 993(Climate zone 1C) |

Results and discussion

Total survey answers classified according to greenhouse sizes above 1 ha, using growth media other than soil and producing only tomatoes. Some basic outcomes of the survey are as follows: average side wall and top height were 6.16 m and 7.6 m, respectively, for glass greenhouses and these were 4.6 and 6 m for plastic greenhouses. Average required ventilation rate estimation by growers was 40.2% (which was satisfactory for Turkish greenhouse growing climates under normal weather conditions). Share of growers giving correct or meaningful answers on fog system installed capacity was 14.7% (that means that a great majority of growers were not aware of the fog system capacity that their greenhouses must have or already have). In countries like Türkiye, where high temperatures and very low humidities could occur frequently, having the know-how and basic info on the fog system is of prior importance as it is the most important tool of humidifying and cooling down the air during heat waves. About 68% of growers who made comments on coping with the climate change implications on greenhouse production suggested new cooling and climate control technologies, while 14% suggested solar electricity systems and new generation greenhouse covers(that implies covers reducing heat load of greenhouses such as near-infrared(NIR) reflecting covers or transparent PVs, or even nano-covers that converts all solar wavelengths to red light mostly used by crops for photosynthesis). About 14% of the growers suggested rainwater and drainage collection re-use technologies to be developed, and another 4% put forward the idea to breed new climate resistant varieties.

Some further data of the survey are given in Table 3 below. It appeared that 34 growers with a total greenhouse area of 326 ha (which is 17.5% of the total hydroponic tomato production area in Türkiye). The number of growers declaring yield loss was 27, which was 79.4% of the total where some growers declared clusters losses, but no yield loss figures given. Normally, the authors could have estimated the approximate yield loss for those who only reported cluster losses with no yield loss indication, but this has not been done to respect the survey answers used as they were fed in. Yield losses changed from 4 to 53% at maximum, however there were only 2 extreme cases with 33% and 53% yield losses deviating from the mean, that may suggest that there might be other reasons for yield loss in those greenhouses in addition to the affects of climate change, such as improper use or inexistence of heating/cooling technologies and other cultural practices, not specified in the survey. So, some parts in our further analysis, these 2 were neglected. The yield loss up to 10% was observed by 11 growers (32% of the total) and between 11 and 20% yield loss by 10 growers (29.4% of the total). Further calculated survey statistics are as follows: Plastic covered greenhouses(91%), glass covered greenhouses (17.6%), cocopeat growing media(91%)-other growing media such as rockwool and torf + perlite mixture(9%), winter production(61.7%), Summer production(35.3%), other type of production-usually Spring–Summer season(3%), Cluster tomatoes(91%) + others such as cherry-beef-cocktail tomatoes(9%).

Table 3.

Result of survey data for the yield loss in 2022–2023 growing season compared with the previous(2021–2022) season

| City(District) | A | CCD | CL | NCL | PYY | SYY | YLP | QL | RSP | RYL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Konya(Meram) | 4,8 | yes | yes | 1 | _ | _ | _ | _ | _ | HT |

| Manisa(Salihli) | 7,2 | yes | yes | 4 | 32 | 30 | 0,06 | yes | yes | HT |

| İzmir(Bergama) | 10 | yes | yes | 4 | 29 | 24 | 0,17 | yes | yes | HT |

| İzmir(Bergama) | 50,6 | yes | yes | 4 | 28 | 23 | 0,18 | yes | yes | HT |

| İzmir(Bergama) | 15 | yes | yes | 3 | 30 | 26 | 0,13 | yes | yes | HT |

| İzmir(Dikili) | 6 | yes | yes | _ | 29 | 27 | 0,07 | no | no | HT |

| İzmir(Dikili) | 17,8 | no | _ | _ | _ | _ | _ | _ | _ | HT |

| Manisa(Salihli) | 35 | yes | yes | 1 | 30 | 28 | 0,07 | yes | yes | LLL |

| Antalya(Manavgat) | 15.64 | yes | no | _ | 28 | 28 | 0,00 | yes | yes | HT |

| Antalya(Manavgat) | 4,5 | yes | no | _ | 35 | 30 | 0,14 | no | no | HT |

| Antalya(Manavgat) | 11,87 | no | no | _ | 16 | 16 | 0,00 | no | no | _ |

| Adıyaman(Kahta) | 1,5 | no | no | _ | 30 | 30 | 0,00 | yes | yes | WLT |

| Adana(Ceyhan) | 7 | yes | yes | 5 | 30 | 20 | 0,33 | yes | yes | HT |

| Adana(Sarıçam) | 3 | no | yes | 2 | _ | _ | _ | yes | no | HT |

| Antalya(Serik) | 12 | no | no | _ | 29 | 29 | 0,00 | no | no | _ |

| Antalya(Kepez) | 6 | yes | yes | 1 | 25 | 22 | 0,12 | no | no | _ |

| Manisa(Ahmetli) | 2,9 | yes | yes | 2 | 35 | 30 | 0,14 | yes | yes | HT |

| Diyarbakır(Bismil) | 1,5 | yes | yes | 7 | 15 | 7 | 0,53 | yes | yes | HT |

| Şanlıurfa(Eyyubiye) | 1,55 | yes | no | _ | 25 | 24 | 0,04 | yes | yes | HRH |

| Mersin(Tarsus) | 3,5 | yes | yes | _ | 30 | 27 | 0,10 | yes | yes | HRH |

| Tekirdağ(Ergene) | 10 | yes | yes | 9 | 35 | 32 | 0,08 | yes | yes | HT |

| Afyonkarahisar(Sandıklı) | 20 | yes | no | _ | 60 | 55 | 0,08 | no | yes | HT |

| Afyonkarahisar(Sandıklı) | 7,4 | no | no | _ | 50 | 50 | 0,00 | no | no | HT |

| Afyonkarahisar(Sandıklı) | 11 | no | no | _ | 50 | 50 | 0,00 | no | no | HT |

| Nevşehir(Kozaklı) | 6,25 | yes | yes | _ | 57 | 52 | 0,09 | no | no | HT |

| Nevşehir(Kozaklı) | 3 | yes | yes | 2 | 40 | 35 | 0,13 | yes | yes | HT |

| Nevşehir(Kozaklı) | 9,2 | yes | yes | 1 | 45 | 43 | 0,04 | yes | yes | HT |

| Nevşehir(Kozaklı) | 3 | yes | yes | 1 | 40 | 35 | 0,13 | yes | yes | HT |

| Nevşehir(Kozaklı) | 2 | yes | yes | 3 | _ | _ | _ | yes | yes | HT |

| Nevşehir(Kozaklı) | 2,4 | yes | yes | 1 | _ | _ | _ | yes | yes | HT |

| Ağrı(Diyadin) | 4 | no | yes | 3 | 30 | 24 | 0,20 | no | no | LLL |

| Denizli(Sarayköy) | 12,6 | yes | yes | _ | 23 | 21 | 0,09 | yes | yes | HT |

| Afyonkarahisar(Çobanlar) | 5 | yes | yes | 2 | 40 | 38 | 0,05 | _ | _ | HT |

| Kırşehir(Merkez) | 12,6 | yes | yes | 3 | 30 | 25 | 0,17 | yes | yes | HT |

Survey data revealed that irrigation and fog system water consumptions increased by 29.32% and 31.42%, respectively and fertiliser and electricity consumption increased by 23.66% and 19%, respectively.

Some 76.5% of the growers declared difficulty in climate control, 11.7% of the growers reported tomato cluster losses with no information on yield loss, 9% of the growers expressed no cluster losses but with some yield losses, 61.7% of the growers declared a loss in tomato quality thus resulting in reduced sales prices at the same time. Some growers(14.7%) did not give any indication on yield losses despite some of them expressed difficulty in climate control, reduced quality and sales prices. One of the most important questions and answers in the survey was the “reason for yield loss” by the eyes of the growers. About 82.3% of the growers declared that the reason for yield loss was the high temperatures. Further, survey answers for irrigation and fog system water, fertiliser and electrical consumption increases, number of cluster losses, previous and survey year yields and yield loss percentages were presented as histograms as shown in Fig. 2 below.

Fig. 2.

Frequency of answers to some survey questions by growers(YLP shown as ratio)

For irrigation and fog system water plus fertiliser consumption frequencies seem to be very close, around 20 to 25% with 8 to 10 frequencies. It seemed that highest frequency for previous year yield was 30 kg/m2. Tomato yield in survey year was between 24 and 32 kg/m2 mostly.

A Cronbach’s Alpha test was conducted for the answers “yes” to be able to understand the significance or trustability of the answers. According to this test, if Cronbach’s Alpha is between 0.6 and 0.8, the answers are accepted as trustable. For the present analysis, this value was 0.625, that meant the answers were meaningful and trustable.

It is important to note also here that tomato yield at locations following winter production at sea level was about 31.5 kg/m2 on average. This was 54.25 kg/m2 for summer production 800 m + above sea level, whereas it was 37.11 kg/m2 for growers following Spring–Summer season 800 m + above sea level, country average being 41 kg/m2. Yield losses for all these 3 types of growing seasons were 10%, 4.6% and 11%, respectively. Total weighed mean yield loss was calculated as 12.56%.

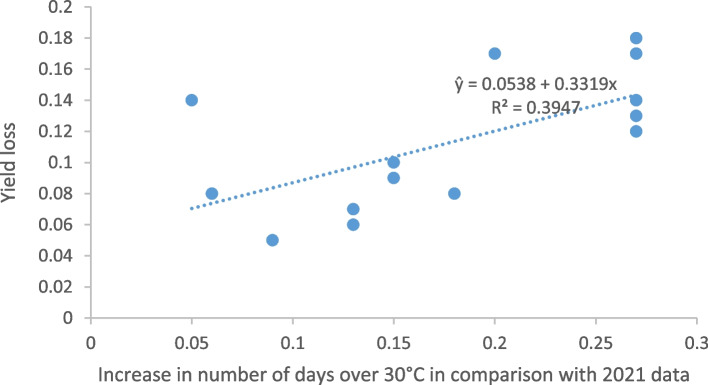

An attempt was made to correlate global temperature change levels with the yield loss from greenhouses. For different regions, the ratio of yield loss in 2022–2023 growing season versus ratio of change in total number of days with over 30 °C outside air temperature which is generally accepted as the temperature where detrimental effects start on tomatoes [3, 8, 13, 31, 39, 46, 61] as shown in Fig. 3. This figure includes exclusion of two extreme yield loss cases(33 and 53%) due to other possible reasons explained before. Some climate data from some locations which declared yield losses were not possible to obtain. So, a data set for 15 locations are presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Relationship between yield loss ratio and temperature change ratio(Pearson Correlation, rxy = 0.628, p < 0.05)

It seems that though the relationship could not be used for an estimation, however, it shows that this Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). If, one could go further with this method, adding ratios of change such as in cloudy days, rainy days, maximum temperatures, average minimum–maximum temperatures, solar radiation etc., and then after by averaging all the climate change ratios and comparing them with yield loss, a very useful tool to predict yield loss could be obtained. If the climate data such as temperature, cloudiness, rain etc. could all have been obtained fully and the percentages of variations with the previous year were calculated for all districts, it would be called “Climate Change-Yield Loss” graph and that would be a very useful tool to understand the climate affect on crop yield in general in many different parts of the world.

The survey results presented here are in line with World Bank Group [81] which estimated 7% decrease in crop yields in Asia and Africa and more than 30% in Arabian Peninsula nd Horn of Africa by 2030 and also a FAO [28] report predicting a crop yield decrease of 25% for Turkey as a resul of climate change. Further, yield loss results of this study were in agreement with the trial results and indications of [2, 3, 6, 13, 19, 20, 31, 39, 41, 43, 46, 61, 66], where negative affects of temperatures over 30 °C were explained well. Quality losses mainly due to high temperatures were found to be serious after the evaluation of this survey, which was in agreement with [62]. However, as for the open field tomato production in Nepal, Bhandari et al. [9] found no significant difference on the climate change affect on tomato production.

Findings in this research also a supporting evidence of a recent report by Hortidaily [40] which stated that horticultural export of Spain dropped 6% in 2023 due to adverse weather conditions, implying a yield loss due to climate change.

Given the technological high-technology greenhouse (HTG) and medium-technology greenhouse (MTG) soilless production area in Türkiye, which is approximately 1,800 ha, and an estimation that 90% of these greenhouses cultivate tomatoes, the total tomato production area can be calculated as 1,620 ha. The estimated tomato loss during the survey year was approximately 4.15 kg/m2, resulting in a total production loss of 13,529,000 kg. With an approximate market price of 1.1 euros per kilogram (Euro/kg), this corresponds to a total economic loss of 14,881,900 euros. Furthermore, if this loss were considered as an opportunity cost for greenhouse investments, climate change might have led to the forfeiture of a 10-ha HTG glass greenhouse or a 20-ha HTG plastic-covered greenhouse investment area, along with the loss of at least 200 jobs in a year. Additionally, various indirect costs, such as pest and disease management, increased water and electricity consumption, and other operational expenses, should also be taken into account.

Another very important indication of climate change reflected in the survey is that irrigation water, fertilizer, and electricity consumption tend to increase significantly along with yield losses [1]. This tells us that the climate control will be very difficult and expensive in greenhouses for future, as present technological system capacities will not be be able to cope with adverse climate affects and expensive new modifications might be needed. Therefore, use of renewable energy sources for electricity supply for greenhouses, better cooling and climate control Technologies (preferably combined with closed or semi-closed greenhouse technology and new generation shading systems and Technologies allowing a high percentage of Photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) transmission and light diffusion along with electricity production from NIR, in other words transparent photovoltaic or agrivoltaics, stronger tomato varieties against the heat stress (all these were also suggested by some growers in the survey), and possible changing cropping seasons to reduce the damage of the climate change affects should be considered as the measures to be taken.

Another important finding was that the growing periods were shifted from summer production to winter production in some regions, to escape from exteremely high summer temperatures, such as transplanting in July–August and removing crops in June of the folowing year instead of transplanting in December and removing crops in November of the other year.

Conclusions

The survey conducted in this study yielded useful results and in agreement with most of the literature cited in this study. It was clear that the level of yield loss(12.56%) was severe basically due to climate change(hot and extreme weather). Considering climate change issues, we suggest that for new greenhouses to be installed in the future, fog systems must be designed with 30-40% extra capacity(over the standard calculation) to cope with climate change challenges that will come more frequently and severer levels in near future.

Authors awareness must be noted that temperature is not the only factor affecting crop growth and yield directly, there could be also other indirect factors influenced by high temperatures such as pest and disease infestation, climate control system efficiency, crop management practices along with other factors such as irrigation strategies, irrigation water quality, pest and disease management strategies etc that could also affect the yield potential in a greenhouse.

One way or the other, climate change seems to force us to change our way of farming and push us for a shorter growing periods than before. That is a challenge that must be overcome by all means of CSA from new and climate resistant crop varieties to technology development along with political programs to be adopted seriously together with all institutions and experts coordinating under one goal. Further, as has been indicated in this study, pressure on water resources will increase further as the weather gets drier and hotter, both irrigation and cooling requirements of the greenhouses will increase dramatically. Therefore, invention and development of new water-saving irrigation and cooling technologies along with rainwater collection systems will be the key issues for future efficient and climate resistant greenhouse production. Further studies should focus also on discovering combined affects of climate change on greenhouse production to take necessary scientific and technological measures to overcome all problems created by increasing temperatures. New growing techniques must be tried and climate resistant crop varieties must also be developed to help reduce climate impact on yield losses.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- A

Area(ha)

- WCI

Water Consumption Increase in 2022/2023 season compared with previous season (%)

- ECI

Electricity Consumption Increase in 2022/2023 season compared with previous season(%)

- FCI

Fertiliser Consumption Increase in 2022/2023 season compared with previous season(%)

- FSWCI

Fog System Water Consumption Increase in 2022/2023 season compared with previous season(%)

- CCD

Climate Control Difficulty in 2022/2024 season compared with previous season

- CL

Clusters loss in 2022/2023 season due to adverse weather conditions

- NCL

Number of clusters lost

- PYY

Previous Year Yield in(kg/m2)

- YLP

Yield Loss Percentage(%)

- SYY

Survey Year(in 2022-23 growing season) Yield loss(kg/m2)

- QL

Quality Loss in 2022/2023 season compared with previous season

- RSP

Reduced Sales Price in 2022/2023 season compared with previous season

- RYL

Reason of Yield Loss

- HT

High Temperature

- WLT

Winter Low Temperature

- LLL

Low Light Level

- LRH

Low Relative Humidity

- HRH

High Relative Humidity

Authors’ contributions

A.K., S.P. and T.F. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. A.K. and S.P. analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abbas F, Al-Otoom A, Al-Naemi S, Ashraf A. Experimental and life cycle assessments of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) cultivation under controlled environment agriculture. J Agric. 2024. 10.1016/j.jafr.2024.101266. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abewoy D. Review on impacts of climate change on vegetable production and its management practices. Adv Crop Sci Tech. 2018;6: 330. 10.4172/2329-8863.1000330. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams SR, Cockshull KE, Cave CRJ. Effect of temperature on the growth and development of tomato fruits. Ann Bot. 2001;88(5):869–77. 10.1006/anbo.2001.1524. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afroza B, Wani KP, Khan SH, Jabeen N, Hussain K. Various technological interventions to meet vegetable production challenges in view of climate change. Asian J Hort. 2010;5:523–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayankojo IT, Morgan KT. Increasing air temperatures and its effects on growth and productivity of tomato in South Florida. Plants. 2020;2020(9):1245. 10.3390/plants9091245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayyogari K, Sidhya P, Pandit MK. Impact of climate change on vegetable cultivation - a review. IJAEB. 2014;7(1):145–55. 10.5958/j.2230-732X.7.1.020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bale JS, Masters GJ, Hodkinson ID, Awmack C, Bezemer TM. Herbivory in global climate change research: direct effects of rising temperature on insect herbivores. Glob Change Biol. 2010;8:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buescher RW. Influence of high temperature on physiological and compositional characteristics tomato fruits. Leben-Wissen Techn. 1979;12:162–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhandari R, Neupane N, Adhikari DP. Climatic change and its impact on tomato (lycopersicum esculentum l.) production in plain area of Nepal. Environmental Challenges. 2021;4:100–29. 10.1016/j.envc.2021.100129. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boonekamp PM. Are plant diseases too much ignored in the climate change debate? Eur J Plant Pathol. 2012;133:291–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Battisti DS, Naylor RL. Historical warnings of future food insecurity with unprecedented seasonal heat. Science. 2009;323:240–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Branthome FX.Worldwide (total fresh) tomato production in 2021. 2023. https://www.tomatonews.com. Accessed on 29.04.2024.

- 13.Berry S, Uddin M. Effect of high temperature on fruit set in tomato cultivars and selected germplasm. HortScience. 1998;23:606–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertin N, Heuvelink E. Dry-matter production in a tomato crop: comparison of two simulation models. Journal of Horticultural Science. 1993;68(6):995–1011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bisbis MB, Gruda N, Blanke M. Potential impacts of climate change on vegetable production and product quality–A review. J Clean Prod. 2018;170:1602–20. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bose B, Pal H. 2023. Impact of Climate Change on Vegetable Production. In: Hasanuzzaman, M. (eds) Climate-Resilient Agriculture, Vol 1. Springer, Cham. 10.1007/978-3-031-37424-1-4.

- 17.BUGEM, 2023. Kapalı ortamda bitkisel üretim kayıt altına alınıyor(Crop production under cover is being registered). www.tarimorman.gov.tr/bugem/haber/865/kapali-ortamda-bitksel-uretim-kayit-altina-aliniyor. Accessed on 29.04.2024.

- 18.Coumou D, Rahmstorf SA. Decade of weather extremes. Nat Clim Change. 2012;2:491–6. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakraborty S, Newton AC. Climate change, plant diseases and food security: an overview. Plant Pathol. 2011;60:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chakraborty S, Luck J, Hollaway G, Freeman A, Norton R, Garrett KA. Impacts of global change on diseases of agricultural crops and forest trees. CAB Rev.: Perspect. Agric Vet Sci Nutr Nat Resour. 2008;3:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das DK, Singh J, Vennila S. Emerging crop pest scenario under the impact of climate change-a brief review. Journal of Agricultural Physics. 2011;11:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deschenes O, Greenstone M. The economic impacts of climate change: evidence from agricultural output and random fluctuations in weather: reply. Am Econ Rev. 2012;102:3761–73. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devi AP, Singh MS Das SP, Kabiraj J. 2017. Effect of Climate Change on Vegetable Production- A Review. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 6(10): 477-483. 10.20546/ijcmas.2017.610.058

- 24. Devot A, Royer L, Arvis B, Deryng D, Caron Giauffret E, Giraud L, Ayral V, Rouillard J. Research for AGRI Committee – The impact of extreme climate events on agriculture production in the EU, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels, 2023:2.

- 25.Dumitru EA, Berevoianu RL, Tudor VC, Teodorescu FR, Stoica D, Giucă A, Ilie D, Sterie CM. Climate Change impacts on Vegetable crops: a systematic review. Agriculture. 2023;13(10): 1891. 10.3390/agriculture13101891. [Google Scholar]

- 26.FAO, 2009. Global agriculture towards 2050 Issues Brief. High level expert forum. Rome, pp: 12–13.

- 27.FAO, Bonn University. İklim değişikliğinin Orta Asya, Kafkasya ve Güneydoğu Avrupa’daki başlıca 20 mahsul zararlısı üzerindeki etkileri (in Turkish). Ankara: FAO; 2022. p. 72. Available from: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cb5954tr. Accessed 10 Jan 2025.

- 28.FAO. 2022. Agricultural production statistics. 2000–2021. FAOSTAT Analytical Brief Series No. 60. Rome. doi.org/10.4060/cc3751en

- 29.Field CB, Jackson RB, Mooney HA. Stomatal responses to increased CO2: implications from the plant to the global scale. Plant Cell Environ. 1995;18(10):1214–25. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuglia K. Climate change upsets agriculture. Nat Clim Chang. 2021;11:293–9. 10.1038/s41558-021-01017-6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giri A, Heckathorn S, Mishra S, Krause C. Heat stress decreases levels of nutrient uptake and assimilation proteins in tomato roots. Plants. 2017;6(6):143–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Golam F, Prodhan ZH, Nezhadahmadi A, Rahman M. Heat tolerance in Tomato. Life Science Journa. 2012;9(4):1936–50. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Güvenç I. Türkiye’de Domates Üretimi, Dış Ticareti ve Rekabet Gücü. KSU J Agric Nat. 2019;22(1):57–61. 10.18016/ksutarimdoga.vi.432316. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghini R, Bettiol W, Hamada E. Diseases in tropical and plantation crops as affected by climate changes: current knowledge and perspectives. Plant Pathol. 2011;60:122–32. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haghighi M, Abolghasemi R, da Silva JAT. Low and high temperature stress affect the growth characteristics of tomato in hydroponic culture with Se and nano-Se amendment. Sci Hortic. 2014;178(2014):231–40. 10.1016/j.scienta.2014.09.0060. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrington R, Fleming RA, Woiwod IP. Climate change impacts on insect management and conservation in temperate regions: can they be predicted? Agric For Entomol. 2010;3:233–40. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harvell CD, Mitchell CE, Ward JR, Altizer S, Dobson AP. Climate warming and disease risks for terrestrial and marine biota. Science. 2006;296:2158–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haybat H. 2013. Cosmogenic Dating Of Glacial Landforms On Akdağ (Western Taurus) And Impact On Contemporary Human Activities. MA Thesis. 103p. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351429039

- 39.Hicks JR, Manzano-Mendez J, Masters JF. Temperature extremes and tomato ripening. Proc Fourth Tomato Qual Workshop. 1983;4(38–51):60. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zapata M. Murcia and southeastern Spain need very little water to produce. Hortidaily Magazine. 2024. Available from: https://www.hortidaily.com/article/9589004/2023-closed-with-lower-spanish-fruit-and-vegetable-export-volumes-but-an-increase-in-value/. Accessed 4 Jan 2024.

- 41.Habib-ur-Rahman M, Ahmad A, Raza A, Hasnain MU, Alharby HF, Alzahrani YM, Bamagoos AA, Hakeem KR, Ahmad S, Nasim W, Ali S, Mansour F, Sabagh EL, A. Impact of climate change on agricultural production; Issues, challenges, and opportunities in Asia. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:925548. 10.3389/fpls.2022.925548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Jackson LE, Wheeler SM, Hollander AD, O’Geen AT, Orlove BS, Six J. Case study on potential agricultural responses to climate change in a California landscape. Clim Change. 2011;109:407–27. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones JW, Dayan E, Allen LH, Van Keulen H, Challa H. A dynamic tomato growth and yield model (TOMGRO). Trans ASAE. 1991;34(2):663–0672. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keskin G, Çakaryıldırım N. Örtüaltı sebze yetiştiriciliği. Tarımsal Ekonomi Araştırma Enstitüsü. 2003;4(8):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keskin G, Gül U. 2004. Domates. Tarımsal Ekonomi Araştırma Enstitüsü 5(13): 1-4

- 46.Kittas C., Karamanis M., and Katsoulas N., 2005. Air temperature regime in a forced ventilated greenhouse with rose crop. Energy Buildings, 37(8):807–812, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378778804003433

- 47.Kumbasaroğlu H, AAşkan E, Dağdemir V. Türkiye’de domatesin ekonomik analizi. Mediterr Agric Sci. 2021;34(1):47-54. 10.29136/mediterranean.734756.

- 48.Kukal MS, Irmak S. Climate-driven crop yield and yield variability and climate change impacts on the U.S. great plains agricultural production. Nature. Sci Rep | 2018;8:3450 | 10.1038/s41598-018-21848-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Lakhiar IA, Gao J, Syed TN, Chandio FA, Buttar NA. Modern plant cultivation technologies in agriculture under controlled environment: a review on aeroponics. Journal of Plant Interactions. 2018;13(1):338–52. 10.1080/17429145.2018.1472308. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lakhiar IA, Yan H, Zhang C, Wang G, He B, Hao B, Han Y, Wang B, Bao R, Syed TN, Chauhdary JN, Rakibuzzaman M. A review of precision irrigation water-saving technology under changing climate for enhancing water use efficiency, crop yield, and environmental footprints. Agriculture. 2024;14(7): 1141. 10.3390/agriculture14071141. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lakhiar IA, Yan H, Zhang J, Wang G, Deng S, Bao R, Zhang C, Syed TN, Wang B, Zhou R, Wang X. Plastic pollution in agriculture as a threat to food security, the ecosystem, and the environment: an overview. Agronomy. 2024;14(3): 548. 10.3390/agronomy14030548. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lakhiar IA, Yan H, Zhang C, Zhang J, Wang G, Deng S, Syed T, Wang B, Zhou R. A review of evapotranspiration estimation methods for climate-smart agriculture tools under a changing climate: vulnerabilities, consequences, and implications. Journal of Water and Climate Change. 2024. 10.2166/wcc.2024.048. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lipper L, Thornton P, Campbell BM, Baedeker T, Braimoh A, Bwalya M, Caron P, Cattaneo A, Garrity D, Henry K, Hottle R, Jackson L, Jarvis A, Kossam F, Mann W, McCarthy N, Meybeck A, Neufeldt H, Remington T, Thi Sen P, Sessa R, Shula R, Tibu A, Torquebiau EF. Climate-smart agriculture for food security. Nature Clim Change. 2014;4:1068–72. 10.1038/nclimate2586. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu B, Song L, Deng X, Lu Y, Lieberman-Lazarovich M, Shabala S, Ouyang B. Tomato heat tolerance: progress and prospects. Sci Hortic. 2023;322: 112435. 10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112435. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lobell DB, Schlenker W, Costa-Roberts J. Climate trends and global crop production since 1980. Science. 2011;333:616–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mattos LM, Moretti CL, Jan S, Sargent SA, Lima CEP, Fontenelle MR. Climate changes and potential impacts on quality of fruit and vegetable crops. Emerging technologies and management of crop stress tolerance, Volume 1. Chapter 19: (Ed. By P. Ahmad), Academic Press, San Diego, CA. 2014:467-486. 10.1016/B978-0-12-800876-8.00019-9.

- 57.Medellin-Azuara J, Howitt RE, Duncan J, MacEwan Lund JR. Economic impacts of climaterelated changes to California agriculture. Clim Change. 2011;109:387–405. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Malhotra SK, Srivastva AK. Climate smart horticulture for addressing food, nutritional security and climate challenges. In: Srivastava AK (ed) Shodh chintan scientific articles, ASM Foundation, New Delhi. 2014:83-97.

- 59.Mukherjee M, Schwabe K. Irrigated agricultural adaptation to water and climate variability: the economic value of a water portfolio. Amer J Agr Econ. 2014;97(3):809–32. 10.1093/ajae/aau101. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Newton AC, Johnson SN, Gregory PJ. Implications of climate change for diseases, crop yields and food security. Euphytica. 2011;179:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ozores-Hampton F, Kiran M, McAvoy G. Blossom drop, reduced fruit set and post-pollination disorders in tomato. 2012. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272166180.10.32473/edis-hs1195-2012.

- 62.Pangga IB, Hannan J, Chakraborty S. Pathogen dynamics in a crop canopy and their evolution under changing climate. Plant Pathol. 2011;60:70–81. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pardossi A, Incrocci L, Tognoni F. Mediterranean greenhouse technology. Chron Hortic. 2004;44(2):28–34. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peet MM, Wolfe D. Vegetable crop responses to climatic change. In: Reddy KR, Hodges HF, editors. Climate change and global crop productivity. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing; 2000:213–43.

- 65.Rowlands DJ, Frame DJ, Ackerley D, Aina T, Booth BBB, Christensen C. Broad range of 2050 warming from an observationally constrained large climate model ensemble. Nat Geosci. 2012;5:256–60. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruiz-Nieves JM, Ayala-Garay OJ, Serra V, Dumont D, Vercambre G, Genard M, Gautier H. The effects of diurnal temperature rise on tomato fruit quality. Can the management of the greenhouse climate mitigate such effects? Scientia Horticulturae. 2021;278: 109836. 10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109836. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scheelbeeka PFD, Birad AF, Tuomistob HL, Greena R, Harrisa FB, Joya EJM, Chalabic Z, Allend E, Hainesc A, Dangoura AD. Effect of environmental changes onvegetable and legume yields and nutritional quality. PNAS. 2018;115(26):6804–9. 10.1073/pnas.1800442115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Silva RS, Kumar L, Shabani F, Picanço MC. Assessing the impact of global warming on worldwide open field tomato cultivation through CSIRO-Mk3·0 global climate model. J Agric Sci. 2017;155:407–20. 10.1017/S0021859616000654. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Singh BK, Leach JE, Delgado-Baquerizo M, Egidi E, Liu H, Trivedi P. Climate change impacts on plant pathogens, food security and paths forward. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:640–56. 10.1038/s41579-023-00900-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sattar S, Iqbal A, Parveen A, Fatima E, Samdani A, Fatima H, Iqbal MS, Wajid M. Tomatoes unveiled: a comprehensive exploration from cultivation to culinary and nutritional significance. Qeios ID: CP4Z4W.2. 2024. 10.32388/CP4Z4W.2.

- 71.Skendžić S, Zovko M, Živković IP, Lešić V, Lemić D. The impact of climate change on agricultural insect pests. Insects. 2021;12(5): 440. 10.3390/insects12050440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stevanović M, Popp A, Lotze-Campen H, Dietrich JP, Müller C, Bonsch M, Schmitz C, Bodirsky BL, Humpenöder F, Weindl I. The impact of high-end climate change on agricultural welfare. Sci Adv. 2016;2(8):e1501452. 10.1126/sciadv.1501452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Shamshiri RR, Jones JW, Thorp KR, Ahmad D, Man HC, Taheri S. Review of optimum temperature, humidity, and vapour pressure deficit for microclimate evaluation and control in greenhouse cultivation of tomato: a review. Int Agrophys. 2018;32:287–302. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Swann ALS, Hoffman FM, Kovene CD, Randerso CT. Plant responses to increasing CO2 reduce estimates of climate impacts on drought severity. PNAS. 2016;113(36):10019–24. 10.1073/pnas.1604581113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Telegraph, 2020. Study finds climate change could reduce fruit and veg yields by a third. www.telegraph.co.uk. Accessed 3 Jan 2024.

- 76.Tirado MC, Clarke R, Jaykus LA, McQuatters Gollop A, Frank JM. Climate change and food safety: a review. Food Res Int. 2010;43:1745–65. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vijayakumar A, Beena R. Impact of temperature difference on the physicochemical properties and yield of tomato: a review. Chem Sci Rev Lett. 2020;9(35):665–81. 10.37273/chesci.CS205107159. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wahid A, Gelani S, Ashraf M, Foolad MR. Heat tolerance in plants: an overview. Environ Exp. 2007;Bot(61):199–223. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang X, Li X, Zhong Y, Blennow A, Liand K, Liu F. Effects of elevated CO2 on grain yield and quality in five wheat cultivars. J Agro Crop Sci. 2022;208:733–45. 10.1111/jac.12612. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wheeler TR, Craufurd PQ, Ellis RH, Porter JR, Prasad PVV. Temperature variability and the yield of annual crops. Agr Ecosyst Environ. 2000;82:159–67. [Google Scholar]

- 81.World Bank Group. Future of food: shaping a climate-smart global food system, 2015:30. www.worlbank.org/agriculture. Accessed 25.03.2024.

- 82.Wu Y, Zhong Y, Liu S, et al. Hydrogeodesy facilitates the accurate assessment of extreme drought events. J Earth Sci. 2025;36:347–50. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yusuf RO. Coping with environmentally induced change in tomato production in rural settlement of zuru local government area of kebbi state. Environmental Issues. 2012;5:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhou X, Harrington R, Woiwod IP, Perry JN, Bale JS. Effects of temperature on aphid phenology. Glob Change Biol. 2014;1:303–13. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gong L, Yu M, Jiang S, Cutsuridis V, Pearson S. Deep learning-based prediction on greenhouse crop yield combined TCN and RNN. Sensors. 2021;21(13):4537. 10.3390/s21134537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.