Abstract

RNA activation (RNAa), a gene regulatory mechanism mediated by small activating RNAs (saRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs), has significant implications for therapeutic applications. Unlike small interfering RNA (siRNA), which is known for gene silencing in RNA interference (RNAi), synthetic saRNAs can stably upregulate target gene expression at the transcriptional level through the assembly of the RNA-induced transcriptional activation (RITA) complex. Moreover, the dual functionality of endogenous miRNAs in RNAa (hereafter referred to as mi-RNAa) reveals their complex role in cellular processes and disease pathology. Emerging studies suggest saRNAs' potential as a novel therapeutic modality for diseases such as metabolic disorders, hearing loss, tumors, and Alzheimer’s. Notably, MTL-CEBPA, the first saRNA drug candidate, shows promise in hepatocellular carcinoma treatment, while RAG-01 is being explored for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, highlighting clinical advancements in RNAa. This review synthesizes our current understanding of the mechanisms of RNAa and highlights recent advancements in the study of mi-RNAa and the therapeutic development of saRNAs.

Keywords: MT: Oligonucleotides: Therapies and Applications, RNAa, saRNA, miRNA, gene activation, oligonucleotides, delivery systems

Graphical abstract

Li and colleagues review RNA activation (RNAa), covering saRNA and miRNA-mediated gene upregulation. The review highlights molecular mechanisms, therapeutic applications (particularly in cancer), and clinical progress with drugs like MTL-CEBPA and RAG-01.

Introduction

In 2006, our group discovered that targeting gene promoters with small double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) could induce gene expression and termed this novel gene-regulating phenomenon RNA activation (RNAa).1 These dsRNAs, termed small activating RNAs (saRNAs), share structural similarities with siRNAs, possessing a 19-nucleotide (nt) duplex with 2-nt overhangs. This discovery was soon corroborated by Janowsky et al. in 2007, who demonstrated RNAa-mediated upregulation of the progesterone receptor (PR) gene.2 While miRNAs are traditionally recognized for gene silencing,3 subsequent research revealed their role in activating gene expression through miRNA-mediated RNAa (mi-RNAa).4,5

The mechanism underlying saRNA-mediated RNAa is facilitated by the RNA-induced transcriptional activation (RITA) complex, which includes key components such as Argonaute 2 (AGO2), RNA helicase A (RHA), and Cln three requiring 9 (CTR9, a part of the PAF1 complex).6 These proteins enable the saRNA/AGO2 complex to target gene promoters in the nucleus, promoting transcriptional activation. Similarly, mi-RNAa, as exemplified by miR-34a, involves miRNAs guiding protein complexes to stalled RNA polymerase II (RNAP II), leading to transcription initiation.7

RNAa, similar to RNA interference (RNAi), is an AGO-dependent process primarily involving AGO2 and AGO1.1,5,6,8,9,10,11,12 Unlike RNAi, where most siRNAs designed to target mRNA sequences exhibit silencing activity, the efficacy of saRNAs is highly dependent on their target location within the promoter region, with factors such as proximity to transcription start sites, sequence context, and local chromatin state being critical determinants of activation2,13,14 versus silencing outcomes.15,16 RNAa also exhibits unique in vitro kinetics characterized by a delayed onset and sustained activity over multiple cell divisions,1,2,13 properties starkly contrasting with RNAi’s rapid yet transient effects and underscoring its epigenetic basis.

The discovery of RNAa has opened up novel research avenues into miRNA regulation networks and the broader roles of miRNAs in cellular and disease processes. Importantly, the capacity of saRNAs and miRNAs to positively modulate gene expression presents exciting therapeutic possibilities. saRNAs have been explored in treating various diseases, including metabolic conditions,17 hearing loss,18 cancer,19,20,21,22,23,24 and neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD).25

Notably, RNAa-based therapeutics have advanced into clinical development. MTL-CEBPA, the first saRNA drug candidate, has demonstrated efficacy in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and is currently in phase II clinical trials.26 RAG-01, another saRNA that activates the p21 gene, has recently received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for phase I trials for the treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC),27 with an ongoing trial in Australia (NCT06351904).

This review aims to synthesize the historical developments and recent advances in RNAa research, with a focus on the roles of endogenous RNAa in cellular processes and the therapeutic potential of saRNA-based treatments.

saRNA-mediated RNAa and the RITA complex

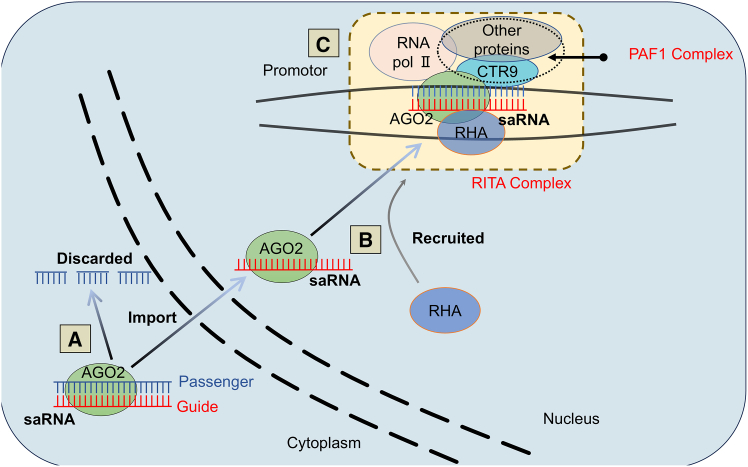

Since the early reports of RNAa mechanism by Li et al. and Janowski et al. in which promoter-targeting saRNA upregulated potent gene expression at the mRNA level, with argonaute proteins, especially AGO2, being indispensable.1,2 A detailed mechanistical model of RNAa remained elusive until, in 2016, Portnoy et al. elucidated the intricate working mode of saRNA-mediated RNAa, which centered around the RITA complex consisting of at least AGO2, RHA, CTR9, and other proteins (Figure 1).6 AGO2 plays a foundational role in the initial stages, engaging with the guide strand of saRNA in the cytoplasm and facilitating its nuclear import, a process that remains to be fully elucidated. Once inside the nucleus, AGO2 recruits RHA, potentially to unravel the DNA helix, allowing saRNA to bind its target. CTR9, a key component of the PAF1 complex (PAF1C) that is known to operate at the interface of transcription and chromatin and play a key role in the regulation RNAP II activity,28,29 is then recruited, setting the stage for RNA polymerase II’s recruitment and the assembly of the RITA complex at the target gene promoter. This assembly shifts the transcriptional machinery into gear, marked by a transition from paused to elongating RNA polymerase II, as shown by changes in phosphorylation patterns at the transcriptional start site (TSS): decrease of Ser5 phosphorylated RNA polymerase II and accumulation of Ser2 phosphorylated RNA polymerase II (corresponding to pausing and elongating polymerase respectively). Additionally, histone H2B monoubiquitination was identified as an early epigenetic event associated with RNAa, believed to promote further histone modifications that enhance active transcription.6 This pivotal work established the RITA complex’s role in saRNA-induced gene upregulation and thus a foundational model of RNAa mechanisms. The findings indicate that saRNAs bind to their intended targets on promoters in a sequence-specific manner, supporting the idea that AGO2 serves as an RNA-programmable recruitment platform for transcriptional activation.

Figure 1.

Mechanistic model of saRNA-mediated RNAa

(A) When an saRNA (double stranded) is recognized and loaded by AGO (e.g., AGO2), the passenger strand is cleaved and discarded in the cytoplasm and the guide strand of the saRNA is retained to form an saRNA-AGO complex, which is imported into the nucleus in an undefined pathway. (B) saRNA guides AGO2 to the promotor target site. (C) At the promotor, key components such as RHA, CTR9, and RNAP II are convened by the AGO2/saRNA complex to assemble the RITA complex, thereby stimulating transcription.

CTR9, as part of the PAF1 complex, is instrumental in RNAa and influences transcription initiation and elongation by interacting with RNA polymerase II. Two independent studies by Voutila et al. and Zhao et al. reaffirmed the critical of CTR9 in RNAa.30,31 The knockdown of other proteins such as DDX5 and HNRNPA2B1 also interrupts saRNA activity, indicating a complex regulatory relationship in RNAa.30

Conservation of RNAa

RNAa was initially observed in human cells, as reported by Li et al.1 This phenomenon was subsequently confirmed across a variety of mammalian cells, including those from African green monkeys, chimpanzees, mice, and rats.32 The evolutionary conservation of RNAa has since been demonstrated in Caenorhabditis elegans33,34,35 and plants.36

In C. elegans, RNAa involves the processing of piRNA precursors into mature 21U-RNAs, which associate with the PRG-1 protein. This complex targets endogenous mRNAs and recruits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) to produce secondary 22G-RNAs. These 22G-RNAs are loaded onto the AGO protein CSR-1, which guides them to nascent transcripts. This process allows CSR-1 to interact with RNAP II and local chromatin, facilitating the recruitment of histone-modifying enzymes. This recruitment promotes epigenetic activation through specific histone modifications, such as H3K4me and H3K36me3, enhancing gene expression.33,34,35

In plants, RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM), triggered by the introduction of inverted repeat sequences targeting a specific intron region, leads to cytosine methylation at particular sites. This methylation, even without continued RNA triggers, causes transcriptional activation and sustained upregulation of the targeted gene, creating a heritable transcriptionally active epiallele.36

More recently, De Hayr et al. extended these observations to insects, showcasing that both short saRNA and long dsRNA can induce the expression of both exogenous (e.g., a GFP reporter gene) and endogenous genes in cell lines derived from Aedes aegypti (Aag2) and Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) as well as in vivo. This induction involves the Ago2 protein and can be triggered by single-stranded RNA targeting either strand of the promoter DNA.37

Building on this, Kwofie et al. identified RNAa in Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks, where saRNA targeting the 3′ UTR of the HlemCHT gene, an endochitinase-like gene, significantly upregulated HlemCHT expression following injection into tick eggs.38 The eggs from the saRNA-treated ticks exhibited advanced developmental stages and increased hatching rates, suggesting that RNAa plays a role in physiological processes such as egg development and hatching. This work represents the first evidence of RNAa in ticks and opens up new possibilities for using RNAa as a gene overexpression tool in tick biology, with potential implications for controlling tick populations and tick-borne diseases.

Nuclear transport of saRNAs

Unlike cytoplasmic RNAi, RNAa occurs in the nucleus, and the saRNA triggers must enter the nucleus to function. The intracellular transport of siRNA and miRNA has been well studied, as karyopherins exportin-1 (XPO1, also known as CRM1) and importin-8 (IPO8), a member of the karyopherin b or protein import receptor importin b family, are involved in the nuclear import of miRNA39 or siRNA,40,41 and XPO5 is responsible for the export of pre-miRNA.42 Although miRNAs are known to function mainly in the cytoplasm, numerous miRNAs are present or even enriched in the nucleus.43,44,45

A number of miRNAs have been found to function in the nucleus as saRNA. A well-studied example is miR-551b-3p, which binds to the promoter of and activates the expression of the STAT3 gene.46 IPO8 is indicated to be related to the nuclear import of miRNA551b-3p by interacting with miR551b-3p-AGO complex.46 In the case of miR-551b-3p, it was found that the UUGGUUU sequence in miR551b-3p is important for its nuclear translocation since mutation of this motif abolishes its nuclear import and activity in inducing STAT3.46 Of course, it is unclear whether this motif serves as a nuclear import signal or the observed loss of nuclear import when it is mutated was simply because of the loss of pairing with a nuclear target.

In this regard, a hexanucleotide motif (5′-AGUGUU-3′) in the 3′ terminus of miR-29b-3p was reported to direct this miRNA to the nucleus.47 However, other studies could not confirm that the miR-29b-3p hexanucleotide motif is a bone fide nuclear-enrichment signal since some miRNAs that contain the same motif do not exhibit nuclear enrichment, while others that lack the motif do show significant enrichment.45,48

The detailed mechanism of how the saRNA enters the nucleus remains largely unknown. Key questions include the form in which saRNAs enter the nucleus (free or AGO protein-loaded), which proteins are responsible for their nuclear import, and the subsequent fate of saRNAs. Castanotto et al. identified a stress-induced response complex (SIRC) crucial for transporting mature RNAs (including miRNAs, siRNAs, and oligonucleotides) into the nucleus.49 Several proteins, including AGO1, AGO2, and transcription or splicing regulators (such as YB1, an integral component in the cellular stress response), participate in SIRC assembly. This study implies that cellular stress could enhance the transport of oligonucleotides or siRNAs to stimulate splicing switch events and increase the efficiency of endogenous miRNA transport targeting nuclear RNAs. Whether the findings from this study are applicable to saRNA awaits to be tested.

miRNA-mediated RNAa

In a pioneering study, Place et al. reported that miR-373, including synthetic mature and its precursor, could activate the expression of two genes CDH1 and CSDC2 in whose promoters it has binding sites.4 Subsequent research by Huang et al. in 2012 revealed that miR-744 and miR-1186 could elicit the expression of Cyclin B1.5 In 2014, Turner et al. expanded this concept by demonstrating that lin-4 could upregulate its own expression via direct binding to a lin-4-complementary element (LCE) on its promoter.50 However, this same group later reported that, under growth conditions that reveal effects at the transgenic locus, a direct, positive autoregulatory mechanism of lin-4 expression occurred only in transgenic lin-4 reporter, not in the context of the endogenous lin-4 locus.51

These studies challenged the conventional view of miRNAs solely as negative regulators of gene expression and revealed a non-canonical gene-regulation function of miRNAs. Since those early studies, many more examples have surfaced in which miRNAs participate in the regulation of cellular and disease processes by positively regulating gene transcription in the nucleus (Table 1). To differentiate RNAa induced by artificially designed duplex saRNA, we will use mi-RNAa hereafter to describe RNAa induced by miRNA.

Table 1.

Reported miRNAs that serve as saRNA

| miRNA | Species | Target gene/genome region | Cellular processes/disease | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-373 | Homo sapiens | CDH1, CSDC2 | N/A | Place et al.4 |

| miR-744, miR-1186 | Mus musculus | Ccnb1 | N/A | Huang et al.5 |

| lin-4 | C. elegans | lin-4 | N/A | Turner et al.50 |

| miR-324-3p | Rattus norvegicus | RelA | N/A | Dharap et al.52 |

| miR-1236 | H. sapiens | CDKN1A | inhibit renal cell carcinoma cell proliferation | Wang et al.53 |

| miR-3619-5p | inhibit prostate cancer cell growth | Li et al.54 | ||

| miR-6734 | induce apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest in colon cancer cells | Kang et al.55 | ||

| miR-370-5p, miR-1180-5p, miR-1236-3p | inhibit bladder cancer and lung cancer cell growth | Wang et al.56 Li et al.57 |

||

| miR-483-5p | H. sapiens | IGF2 | promote sarcoma cell tumorigenesis | Liu et al.58 |

| Let-7i; miR-138; miR-92a; miR-181d | H. sapiens | IL-2, Insulin, Calcitonin, c-myc |

N/A | Zhang et al.59,60 |

| miR-589 | H. sapiens | COX-2 | N/A | Matsui et al.61 |

| miR-877-3p | H. sapiens | CDKN2A | inhibit bladder cancer proliferation | Li et al.62 |

| miR-4281 | H. sapiens | FOXP3 | regulate immune function by accelerating the differentiation of human naive cells to induced Tregs | Zhang et al.63 |

| miR-140 | H. sapiens, M. musculus | NEAT1 (long non-coding RNA) | induce adipogenesis | Gernapudi et al.64 |

| miR-H3 | H. sapiensa | HIV-1 | N/A | Zhang et al.65 |

| Let-7c | H. sapiens | BACE2 | reduce β-amyloid production (AD) | Liu et al.25 |

| miR-150 | M. musculus | PLIN2 | increase hepatocyte lipid accumulation | Luo et al.10 |

| miR-23a | Sus domestica | NORHA | facilitate granulosa cell apoptosis | Wang et al.66 |

| miR-339 | S. domestica | CYP19A1 | facilitate granulosa cell estrogen release | Wang et al.67 |

| miR-320 |

H. sapiens; M. musculus; R. norvegicus |

CD36 | facilitate cardiac dysfunction under diabetes | Li et al.68 |

| miR-551b-3p | H. sapiens | STAT3 | promote TNBC and ovarian cancer progression | Chaluvally-Raghavan et al.11 and Parashar et al.46 |

| miR-451a | H. sapiens | KDM7A | induce cetuximab resistance of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | Zhai et al.69 |

| miR-122-5p | H. sapiens | IGFBP4 | inhibit intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | Tao et al.70 |

| miR-617 | H. sapiens | DDX27 | inhibit OSCC growth | Sarkar et al.71 |

| miR-34a | H. sapiens | ZMYND10 | N/A | Ohno et al.7 |

| miR-17-5p | Ovis aries | KPNA2 | inhibit high-glucose-induced apoptosis of granulosa cells | Wang et al.72 |

N/A, not applicable.

miR-H3 was encoded by HIV and enhanced HIV replication by targeting the TATA box of HIV, but this process occurred in human CD4+ T cells.

Recent examples of mi-RNAa

miR-34a

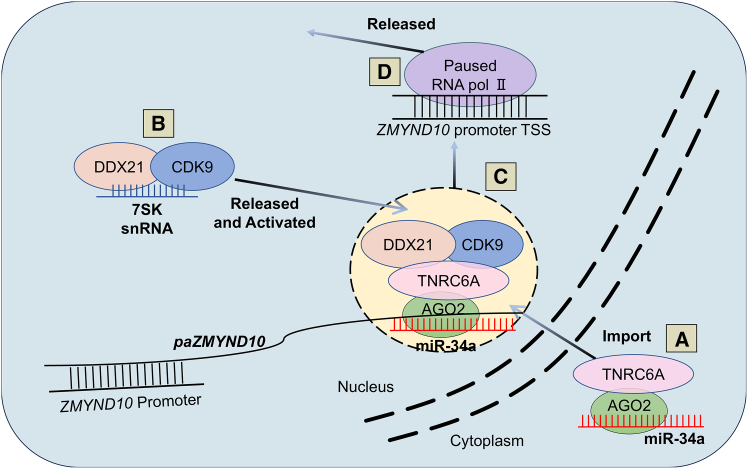

A study by Ohno et al. sheds light on the intricate mechanism of mi-RNAa. The authors focused on the induction of the ZMYND10 gene by miR-34a in human non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell line H1299 as a model system to dissect the mi-RNAa mechanism.7 The authors found that miR-34a binds to a long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) transcribed from the ZMYND10 promoter region, termed promoter-associated RNA (paRNA) paZMYND10. This interaction in the nucleus leads to the recruitment of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), composed of AGO and TNRC6A proteins, to the ZMYND10 promoter. The RISC, in turn, forms a complex with DDX21 and CDK9, key components of the positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb). The miR-34a-RISC-DDX21-CDK9 complex then facilitates the release of paused RNAP II at the ZMYND10 promoter, allowing for active transcription and subsequent upregulation of ZMYND10 expression (Figure 2). The dependence of this mi-RNAa mechanism on DDX21 and CDK9 was further confirmed by the observation that their inhibition significantly attenuated ZMYND10 induction by miR-34a without affecting the miRNA’s canonical gene-silencing function.

Figure 2.

A mechanistic model of miR-34a-mediated mi-RNAa

(A) miR-34a is imported to the nucleus by interacting with the AGO2/TNRC6A complex. (B) Inside the nucleus, DDX21 and CDK9 are released and activated by binding with the AGO2-miR-34a-TNRC6A complex. (C) The complex, now including DDX21 and CDK9, binds to paRNAs overlapping the ZMYND10 promoter. (D) The complex’s presence at the ZMYND10 promoter enables the release and activation of paused RNA polymerase II (RNA pol II), leading to transcription activation of the ZMYND10 gene.

The study proposes a model where the release of paused RNAP II, mediated by the interplay between miRNA, RISC, and transcription elongation factors, constitutes the core mechanism of mi-RNAa, at least in the context of ZMYND10 regulation by miR-34a, and provides compelling evidence for a novel miRNA-mediated RNAa mechanism (Figure 2), opening new avenues for research into the multifaceted roles of miRNAs in gene regulation and disease development. This study also highlights the importance of promoter-associated lncRNAs as key players in RNAa.

This mechanism revealed in this study seems to be remarkably similar to RNAa induced by saRNA in which the RITA complex triggers elongation of transcription by phosphorylating RNAP II at Ser2 of the CTD domain (discussed above).

miR-150

In a 2023 study, Luo et al. explored the role of nuclear miR-150 in promoting hepatic lipid accumulation, particularly in the context of alcoholic fatty liver (AFL) disease.10 The authors identified perilipin-2 (PLIN2) as a direct target of miR-150 and demonstrated that miR-150 enhances PLIN2 expression by binding to RNA transcripts overlapping the PLIN2 promoter and facilitating the recruitment of RNAP II and RHA, and AGO2 or RHA knockdown abolished the gene expression activation by miR-150. These findings suggest that miR-150 acts as a pro-steatotic factor in the liver by modulating the transcription of genes involved in lipid accumulation.10

mi-RNAa mediated by TATA box- and enhancer-targeting miRNAs

mi-RNAa has expanded the function of miRNA and our understanding of RNAa. Two specific targeting models are worth noting, which are RNAa induced by miRNAs that bind the TATA Box in core promoters59,60 and miRNAs that bind enhancers.73 Initially, Zhang et al. reported that miR-H3 targets the 5′ LTR TATA box of HIV-1 and activates the viral promoter in a sequence-specific manner to upregulate HIV-1 RNA and protein expression.65 The same group later illustrated the mechanism of gene upregulation induced by TATA-box-targeting miRNA.60 With the help of AGO2, TATA-box-targeting miRNA triggered transcriptional activation by directly interacting with the TATA-box motifs and recruited the RNAP II to form a transcription preinitiation complex (PIC), a process resembling that identified in saRNA-induced RNAa6(discussed above). Adjacently, they identified similar activating mechanisms for the genes IL-2, insulin, calcitonin, and c-myc by miRNAs let-7i, mir-138, mir-92a, and mir-181d, respectively, by targeting each promoter’s TATA box.60

In 2017, Xiao et al. explored RNAa events mediated by enhancer-targeting miRNAs.74,75 Their study demonstrated that a subset of miRNAs, including miR-24-1, can activate gene transcription by targeting enhancer regions. Specifically, miR-24-1 functions as an enhancer trigger, leading to increased expression of neighboring protein-coding genes. This activation is associated with several key mechanisms: the upregulation of enhancer RNA (eRNA) expression, alterations in histone modifications, and the recruitment of transcriptional machinery, including RNAP II and the co-activator p300, to the enhancer locus. Notably, the activation of gene transcription by miR-24-1 was contingent upon the integrity of the enhancer sequence; deletion of the enhancer abolished the transcriptional activation, underscoring the specificity of this regulatory mechanism. The study also highlighted the dual functionality of miRNAs, where they can act as repressors in the cytoplasm while simultaneously promoting transcription in the nucleus.

In a subsequent study,76 the same research group presented further evidence of nuclear miRNAs targeting enhancers, focusing specifically on miR-339 and its role in the reactivation of the tumor suppressor gene G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER1) in breast cancer through enhancer switching mechanisms. Their findings revealed that low expression levels of miR-339 correlated with the downregulation of GPER1 across various breast cancer subtypes, particularly in Luminal A/B and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Mechanistic studies illustrated that miR-339 functioned to enhance GPER1 expression by activating its associated enhancer, a process that can be inhibited by targeted enhancer deletion using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. This research reinforced the concept of nuclear-activating miRNAs as critical regulators of enhancer activity and subsequently tumor suppressor gene (TSG) expression.

Network regulation of miRNAs

While most mi-RNAa phenomena were reported as relationships of one miRNA to one target gene, similar to posttranscriptional regulation by targeting 3′ UTR, mi-RNAa could occur as the one-to-many or many-to-one relationship. In the first report of mi-RNAa, Place et al. demonstrated that introducing into cells miR-373, which was predicted to bind the promoter of e-cadherin (CDH1) and cold shock domain-containing protein c2 (CSDC2) could induce the expression of both genes.4 In a study by Huang et al.,5 two mouse endogenous miRNAs, miR-744 and miR-1186, were predicted to bind different regions of the Ccnb1 promoter. Introducing either of these two miRNAs into cells sustained Ccnb1 expression, leading to similar phenotypes in the cells.

In another study by Huang et al.,5 the authors used chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) to uncover a network of interactions where miRNAs regulate protein-coding genes by guiding Ago1 to their promoters in prostate cancer cells. AGO1 was found to bind to the promoters of actively transcribed genes involved in cell growth and oncogenesis, interacting with RNAP II to facilitate transcription. Disrupting miRNA biogenesis through Dicer and Drosha knockdowns reduced AGO1-RNAP II interactions, indicating that miRNAs play a critical role in directing AGO1 to specific promoters. This study illustrated a network of miRNA-mediated transcriptional regulation where miRNAs target multiple gene promoters, enabling a coordinated activation of oncogenes via RNAa. The findings have significant implications for cancer biology, suggesting that miRNA-AGO interactions could be targeted to modulate oncogene expression. Further research is necessary to determine if this network regulatory mechanism is active in non-cancer contexts.

Involvement of mi-RNAa in cellular processes and diseases

miRNAs are known to play pivotal roles in cellular processes by binding to and regulating the stability or translation of mRNA, typically leading to mRNA degradation or translational repression.3 Aberrant regulation of miRNAs, whether through overexpression of harmful miRNAs, deficiency of critical miRNAs, or dysregulation of tissue-specific miRNAs, has been closely linked to the development of various diseases, including cancer and metabolic disorders. Recent studies have expanded this understanding by highlighting the involvement of mi-RNAa in cellular and disease processes. In this section, we discuss how mi-RNAa contributes to the regulation of complex biological mechanisms and disease development. For instance, miR-182-5p has been implicated in liver regeneration,77 while miR-320 plays a significant role in lipid metabolism.68 These findings reveal how mi-RNAa is emerging as a key regulatory pathway, adding complexity to our understanding of miRNA function in health and disease.

Let-7 and AD

Liu et al. investigated the role of miRNA let-7c in modulating gene expression through RNAa within the context of AD in a Down syndrome (DS) cell line (MB1478) and a transgenic mouse model of AD (B6/JNju-Tg(APPswe, PSEN1dE9)/Nju).25 They found that let-7c was upregulated in these models, correlating with reduced β-amyloid (Aβ) production. This reduction was achieved through increased expression of BACE2, which cleaves amyloid precursor protein (APP) in a non-amyloidogenic pathway. Let-7c binds directly to the BACE2 promoter, activating its transcription via RNAa.

The authors propose a mechanistic model where let-7c activates BACE2 transcription, shifting APP processing from an amyloidogenic to a non-amyloidogenic pathway, reducing Aβ accumulation in the brain. Together, this study provides a compelling example of how miRNAs like let-7c can influence disease processes by engaging RNAa mechanisms. The findings underscore the therapeutic potential of miRNA-based interventions in AD, offering new avenues for research and treatment.

mi-RNAa in liver diseases

miRNAs have been found to be involved in hepatocyte cellular processes and diseases, including liver regeneration,78,79 liver fibrosis,80,81 non-alcoholic fatty liver disease,82,83,84,85 and even HCC.86,87 However, the role of mi-RNAa in liver diseases has not been reported until recent years.

The miR-150 example discussed above revealed that miR-150 promotes lipid accumulation in hepatic cells under the circumstance of ethanol exposure by directly activating PLIN2, a lipid-sequestration-related gene.10

Xiao et al. investigated the role of miR-182-5p in liver regeneration following partial hepatectomy (PH).77 They found that miR-182-5p heterozygous knockout mice exhibited impaired liver regeneration and reduced hepatocyte proliferation, which was reversed by miR-182-5p overexpression. The study revealed that miR-182-5p positively regulates Cyp7a1 expression by binding to its promoter, leading to increased cholic acid (CA) production. Elevated CA activates hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), which produce hedgehog (Hh) ligands like Indian hedgehog (Ihh) that stimulate hepatocyte proliferation via the Hedgehog signaling pathway. This research underscores the role of miR-182-5p in facilitating crosstalk between hepatocytes and HSCs, promoting liver regeneration through enhanced hepatocyte proliferation.

mi-RNAa in porcine granulosa cells

Wang et al. explored the role of miR-23a in porcine granulosa cell apoptosis66 and found that miR-23a, predominantly nuclear, bound to the promoter region of the NORHA gene and activated its expression, leading to apoptosis in granulosa cells.

A 2023 study67 from the same group identifies miR-339 as a saRNA that activates the transcription of CYP19A1, the gene encoding the aromatase enzyme crucial for estrogen (E2) synthesis in granulosa cells. miR-339 bound directly to the promoter of CYP19A1, enhancing its transcription and subsequent E2 release. The research also highlighted that the nuclear long non-coding RNA NORSF acts as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) for miR-339, preventing it from activating CYP19A1 when NORSF levels are high. This interaction underscores the regulatory role of miR-339 in E2 synthesis and suggests potential therapeutic applications for improving female fertility.

mi-RNAa in cardiac diseases

Wang’s group systematically studied the impact of miR-320 on glucose and lipid metabolism and identified its crucial involvement in the regulation of key metabolic pathways and its contributions to disease progression via mi-RNAa and conventional mRNA suppression mechanisms.68,88,89,90

Initially, Wang and colleagues identified miR-320 as a key player in cardiovascular diseases, particularly in the context of diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction.91 They demonstrated that miR-320 is upregulated in the hearts of diabetic mice and is involved in the activation of transcriptional programs that lead to lipotoxicity and cardiac dysfunction. This was shown by their findings that miR-320 directly activates the transcription of fatty acid metabolic genes, such as CD36, through its interaction with the Argonaute 2 (Ago2) protein, which is crucial for its function as an saRNA.68

In their subsequent studies, the group further elucidated the mechanisms by which miR-320 exerts its effects. They found that miR-320 is not only present in the cytoplasm but also localized in the nucleus, where it can interact with promoter regions of target genes. This nuclear localization allows miR-320 to influence gene expression directly, thereby functioning as an activator of transcription rather than merely repressing target mRNAs.88,89

Building on these findings, they uncovered a positive feedback loop between miR-320 and CD36 that aggravates hyperglycemia-induced cardiomyopathy and metabolic dysfunction.90 The group also revealed that miR-320’s transcriptional activation capabilities extend to other metabolic genes, positioning it as a central regulator of glucose and lipid metabolism in the heart, liver, and other tissues.68,88

mi-RNAa in cancer

miR-551b-3p

In recent years, mi-RNAa has emerged as a significant mechanism in cancer progression, with miR-551b-3p standing out for its oncogenic roles in multiple cancers.92,93 In ovarian cancer, miR-551b-3p, located at the 3q26.2 amplification site, plays a crucial role in tumor growth and metastasis.11 Previous studies demonstrated that miR-551b-3p directly binds to the promoter of STAT3, upregulating its transcription and contributing to the deregulation of cell proliferation, survival, and chemotherapy resistance in high-grade serous epithelial ovarian cancer (HGSEOC).11 Mechanistically, miR-551b-3p recognizes and binds the STAT3 promoter via sequence complementarity within the promoter region, enabling transcriptional activation through interactions with nuclear AGO2. Silencing miR-551b-3p with anti-miR treatments significantly reduced tumor growth in vitro and in vivo, making it a promising therapeutic target for ovarian cancer management.11

Further expanding its oncogenic role, a 2019 study by the same group revealed that miR-551b-3p also promoted the progression of TNBC by activating an oncostatin signaling module.46 Upon nuclear translocation, which depended on Importin-8 (IPO8), miR-551b-3p upregulates STAT3 and oncostatin family genes, establishing an autocrine loop that drives cancer cell growth and metastasis. Inhibition of miR-551b-3p disrupted this oncogenic signaling pathway.46

Together, these findings highlight the dual oncogenic roles of miR-551b-3p across different cancers through its ability to activate the transcription of key genes via mi-RNAa. This exemplifies how mi-RNAa contributes to cancer progression and opens up novel avenues for targeted therapies that disrupt miRNA-mediated gene activation in malignancies.

miR-451a

A 2024 study by Zhai et al. uncovered a critical role for miR-451a in mediating drug resistance. The authors found that, in cetuximab-resistant head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cells, miR-451a was highly enriched in the nucleus where miR-451a activated the expression of the KDM7A gene by interacting with an enhancer region within the gene. This activation of KDM7A, a lysine demethylase, promoted cancer cell proliferation and migration, ultimately contributing to cetuximab resistance. Mechanistically, this process was shown to be AGO2 dependent, as silencing AGO2 led to reduced KDM7A expression and restored sensitivity to cetuximab. Clinically, the study demonstrated a correlation between high levels of miR-451a and KDM7A in a cohort of 87 HNSCC patients, linking them to cetuximab resistance. These findings suggest that nuclear miR-451a-mediated RNAa of KDM7A plays a pivotal role in cetuximab resistance, offering potential new therapeutic targets for overcoming resistance in HNSCC.

miR-122-5p

The study by Tao et al.70 investigated the role of miR-122-5p in inhibiting metastasis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC). They discovered that miR-122-5p was downregulated in ICC and played a crucial tumor-suppressing role. Using various cell-based assays, the study found that overexpression of miR-122-5p significantly inhibited migration, invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in ICC cell lines. They further identified insulin-like growth factor binding protein 4 (IGFBP4) as a direct target of miR-122-5p, which bound to the promoter region of the IGFBP4 gene and activated its transcription. IGFBP4 expression was inversely correlated with tumor invasiveness and metastasis, and higher levels of IGFBP4 were associated with better patient outcomes. In an in vivo patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model, miR-122-5p overexpression significantly reduced tumor growth and metastasis, further supporting its potential therapeutic value in inhibiting ICC progression.

miR-617

Sarkar et al.71 reported that miR-617 impeded cell viability and proliferation in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) by upregulating the expression of DDX27 via interacting directly with its promoter, as confirmed through dual-luciferase assays.71 Additionally, miR-617 was found to modulate the PI3K/AKT/MTOR signaling pathway via DDX27, contributing to reduced cancer cell viability. The study also explored the clinical relevance of miR-617 and DDX27 in OSCC patient samples, showing a positive correlation between their expression levels in a subset of cases.

Regulation of the immune system

The study by Zhang’s group, previously found that miRNAs enhance the activities of several viral and cellular promoters through sequence-specific interactions with the TATA-box motif.60,65,94 Another study from the same group demonstrates that miR-4281 plays a crucial role in the immune system by upregulating the expression of the FOXP3 gene, a key factor in regulatory T cell (Treg) development.63 Through direct interaction with the TATA-box motif in the FOXP3 promoter, miR-4281 enhanced FOXP3 transcription, promoting the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into functional Tregs with potent immunosuppressive capabilities. This process was validated in both human naive CD4+ T cells and humanized mouse models, where miR-4281-induced Tregs significantly reduced graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) severity. The study suggests that miR-4281 could be a therapeutic target for enhancing Treg function in immune-related conditions, although its hominid-specific nature may limit broader applicability.

saRNAs as therapeutics

There is a critical unmet medical need in drug development for targeted activation of therapeutic genes to treat genetic and complex diseases, and saRNA emerges as a promising technology approaching clinical validation. Unlike other gene/protein augmentation approaches such as DNA replacement, mRNA, or protein therapeutics, saRNA offers distinct advantages: it is more compact, potentially easier to deliver, more cost-effective to manufacture, and, critically, does not permanently alter the genome. However, saRNA faces unique challenges compared to siRNA therapeutics, primarily requiring more sophisticated delivery systems to successfully translocate into the nucleus as most delivered duplex RNA is sequestered in the cellular cytosol. The therapeutic promise of saRNAs was recognized early, with initial research efforts strategically targeting genes involved in cancer and inherited genetic disorders.

saRNAs for cancer treatment

Since the discovery of RNAa, the potential of treating cancer with saRNAs that activate TSGs has been extensively explored.19,21,22,57,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102 We discuss here some recent examples of exploiting saRNAs as a cancer treatment in preclinical settings.

Yang et al. designed saRNA (dsPAWR-435) to stimulate the pro-apoptotic WT1 regulator (PAWR) expression in bladder cancer cell lines.21 Activating PAWR expression in T24 and 5637 induced their cell apoptosis and G1-phase arrest by impacting the Bcl-2 (anti-apoptotic proteins) and restraining the nuclear factor (NF)-κB and Akt signaling pathways. A combination of dsPAWR-435 with cisplatin showed enhanced anti-tumor effects, suggesting the possibility of listing dsPAWR-435 as an alternative bladder cancer therapeutic schedule.

The report of Park et al. demonstrated that VDUP1 upregulation induced by saRNA (dsVDUP1-834) can inhibit cell growth and arrest cell cycle in lung cancer cells.22 In A549 cells, vitamin D3 upregulated protein 1 (VDUP1) is activated by dsVDUP1-834 in an AGO2-dependent way. After dsVDUP1-834 treatment, DNA demethylation and altered transcriptional marker accumulation at the VDUP1 promoter further prove that it is a canonical RNAa event. In the A549 xenograft model, the smaller tumor volume of the dsVDUP1-834-treated group indicates a reliable in vivo tumor-inhibiting efficacy.

The study by Bi et al. explored the use of saRNAs to target and activate the TSG LHPP in HCC. LHPP was recently identified as a crucial factor in the pathogenesis of HCC, and its inactivation is directly linked to the development of the disease, whereas its reactivation has been shown to promote tumor suppression.103 Through high-throughput screening, RAG7-133 was identified as a potent saRNA that significantly upregulated LHPP mRNA and protein expression, leading to suppressed phosphorylated Akt and decreased HCC cell proliferation and migration in vitro. RAG7-133 formulated in in vivo jetPEI demonstrated antigrowth effect in a HepG2 xenograft HCC model and had synergistic effects in inhibiting tumor growth with target anticancer drugs such as regorafenib. These findings suggest that saRNA-induced activation of TSGs could be a promising therapeutic approach for HCC treatment.

saRNA for combating cancer resistance

Recent progress in saRNA therapeutics has opened new avenues for addressing drug resistance in cancer by reactivating silenced tumor suppressor genes. Wang et al.23 investigated the role of protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type O (PTPRO) in trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer and explored the use of saRNA to reactivate PTPRO and overcome this resistance. They found that PTPRO downregulation correlates with trastuzumab resistance due to increased activity of tyrosine kinases like ERBB2, ERBB3, and SRC. They designed saRNAs targeting the PTPRO promoter, with saPTPRO-220 demonstrating the most effective upregulation of PTPRO expression in both trastuzumab-sensitive and resistant breast cancer cell lines (BT474, SKBR3, BT474-HR20, and SKBR3-Pool2). This PTPRO upregulation led to decreased phosphorylation of ERBB3 and SRC, restoring sensitivity to trastuzumab. To enhance delivery and efficacy, the saRNA was encapsulated in trastuzumab-conjugated mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNPs). This targeted delivery system successfully increased PTPRO expression in tumor cells in vitro and in vivo using a human cell-line-derived xenograft model. The in vivo studies showed that the combination of saPTPRO-loaded nanoparticles and trastuzumab significantly inhibited tumor growth. This research highlights the potential of saRNA technology, particularly when combined with targeted nanoparticle delivery, to reactivate tumor suppressor genes like PTPRO and overcome drug resistance in cancer treatment, offering a novel approach to “drugging the undruggable” phosphatases.

CDH13, a tumor suppressor gene, is significantly downregulated in several types of cancer due to hypermethylation of its promoter region.104,105,106 Su et al. confirmed low CDH13 expression in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cell lines and successfully designed saRNAs (C2 and C3) to upregulate CDH13 expression in CML cells, which are often resistant to standard treatments like imatinib.24 These saRNAs not only restored CDH13 expression but also significantly suppressed tumor cell growth and enhanced the efficacy of imatinib by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway, leading to increased apoptosis in resistant cells. The in vivo efficacy of the saRNAs was tested using a CML xenograft mouse model. Treatment with CDH13-saRNA formulated in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) significantly inhibited tumor growth and improved survival rates in mice, supporting the potential of saRNA-based therapies in overcoming cancer drug resistance.

saRNA for nonmalignant diseases

Acute lung injury

Very recently, Zhang et al. demonstrated the potential of CEBPA-saRNA therapy for acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).107 The authors developed an artificial neutrophil delivery system (NHR) to efficiently deliver CEBPA-saRNA to inflamed lungs. The CEBPA-saRNA was complexed with H1 histone and coated with a neutrophil membrane to create NHR, which exhibited effective cellular uptake by M1 macrophages and induced M2 polarization, thus reducing inflammation. In a mouse model of ALI, NHR accumulated in inflamed lung tissues and significantly improved lung injury, indicating its potential as a novel saRNA-based therapeutic strategy for ALI/ARDS.

Proliferative vitreoretinopathy

Zhang et al.108 explored the use of saRNA to treat proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR), a condition that arises from excessive proliferation of retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells after retinal detachment surgery. The saRNA, RAG1-40-53, was designed to upregulate the p21 gene in RPE cells. In vitro, the saRNA successfully increased p21 expression, inhibiting RPE cell proliferation and migration. In a rabbit PVR model, intravitreal administration of the saRNA led to reduced progression of PVR by preventing fibrous membrane formation and retinal detachment. The saRNA exhibited sustained presence in the vitreous humor with minimal systemic exposure, suggesting its potential as a novel treatment for PVR and other fibrotic diseases.

Metabolic disorders

To explore the therapeutic potential of activating Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) using saRNA in treating metabolic syndrome (MetS)—a condition marked by abdominal obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia—Andrikakou et al.17 developed SIRT-PR57, a saRNA that targets and upregulates SIRT1, a key metabolic regulator and protector against aging-related pathologies, including MetS. The saRNA significantly enhanced SIRT1 expression in both stimulated and nonstimulated macrophages, resulting in a marked reduction in inflammation. This was achieved by decreasing the levels of key pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and chemokines. Additionally, SIRT1 activation led to the downregulation of crucial inflammatory signaling pathways by reducing the phosphorylation of NF-κB and c-Jun N-terminal kinase. In a high-fat diet model, animals treated with SIRT1 saRNA showed improved metabolic health, with reductions in weight gain, white adipose tissue, triglycerides, fasting glucose, and intracellular lipid accumulation—indicative of better lipid and glucose metabolism. These findings suggest that SIRT1 activation via saRNA could offer a promising therapeutic strategy for reversing MetS and addressing its related metabolic disturbances.

Very recently, Cai et al.109 developed a novel tetrahedral framework nucleic acid (tFNA) system that can effectively deliver saRNA to upregulate SIRT1 gene expression and modulate the bone immune microenvironment in diabetic osteoporosis. By activating the SIRT1/acetyl-NF-κB pathway, the saRNA promoted the polarization of macrophages from the pro-inflammatory M1 to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, thereby restoring bone immune homeostasis and facilitating osteogenesis in a high-glucose environment.

Cardiovascular diseases

A study by Yang et al.110 identified the critical role of βII spectrin, a cytoskeletal protein, in maintaining cardiac function by regulating mitochondrial respiration and demonstrated that its targeted activation using saRNAs can mitigate mitochondrial respiratory dysfunction and improve cardiac performance. The researchers first observed that βII spectrin is degraded in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and in mice following ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. Moreover, βII spectrin deficiency was shown to result in cardiac dysfunction, hypertrophy, and fibrosis. Given the challenges associated with traditional gene therapy for large proteins like βII spectrin, the authors developed multiple saRNA constructs targeting specific promoter regions of the βII spectrin gene. Among these, saRNA-54 and saRNA-56 were identified as particularly effective in enhancing βII spectrin expression in cardiomyocytes. Using adenoviral vectors, the saRNA constructs were delivered via intramyocardial injection. Both saRNA-54 and saRNA-56 significantly alleviated I/R-induced cardiac contractile dysfunction, reduced myocardial infarct size, increased resistance to myocardial apoptosis, and improved mitochondrial function. This study provides a compelling proof of concept for targeted βII spectrin gene activation and underscores the potential of saRNA-based therapies for cardiovascular diseases.

saRNA therapeutics under clinical development

Besides work from academic laboratories, a few biotech companies are developing saRNA-based therapeutics for a variety of disorders, including UK-based MiNA Therapeutics, China-based Ractigen Therapeutics, and Finland-based RNatives, with saRNA pipeline programs targeting cancer, neuromuscular diseases, hepatic diseases, ophthalmic diseases, hematology diseases, and cardiovascular diseases. Among these, MTL-CEBPA and RAG-01 have entered phase I/II clinical trials and phase I clinical trials, respectively.

MTL-CEBPA

MTL-CEBPA was developed to upregulate C/EBP-α, a transcription factor crucial for hepatic and myeloid functions and implicated in oncogenesis. C/EBP-α plays a key role in liver homeostasis, making MTL-CEBPA a promising candidate for treating conditions like cirrhosis and HCC, where C/EBP-α is downregulated.111,112 MTL-CEBPA progressed to a phase I open-label, dose-escalation trial in adults with advanced HCC, including patients with cirrhosis or liver metastases. In this trial, 38 participants received intravenous MTL-CEBPA weekly over 3 weeks with a 1-week rest period between cycles. The study, which tested doses ranging from 28 to 160 mg/m2, found no dose-limiting toxicity, with an acceptable safety profile and no maximum dose identified.26

In terms of efficacy, one patient achieved a partial response lasting over 2 years, and 12 others showed stable disease. Interestingly, MTL-CEBPA displayed synergy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), as several patients who received subsequent TKI treatment after discontinuing MTL-CEBPA demonstrated significant responses, including complete and partial remissions. This prompted further combination studies of MTL-CEBPA with sorafenib in HCC.113 Additionally, MTL-CEBPA showed anti-inflammatory properties by inhibiting the suppressive activity of myeloid cells rather than directly targeting tumor cells. This led to its combination with the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab in ongoing phase I/Ib trials.20 MTL-CEBPA’s clinical trials mark a milestone as the first saRNA therapeutic to enter clinical development, highlighting the potential of saRNA-based treatments for complex diseases like cancer, particularly through targeted gene upregulation.

RAG-01

RAG-01 is a saRNA drug developed by Ractigen Therapeutics to treat NMIBC, which accounts for 70%–75% of bladder cancers.114 Standard treatments for NMIBC include transurethral resection of the tumor followed by intravesical chemotherapy or bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) instillations, yet the 5-year recurrence rate remains high at 50%–70%. RAG-01 specifically targets and upregulates the tumor suppressor gene p21, involved in processes like cell proliferation inhibition, apoptosis, DNA repair, and senescence.115,116

Administered via intravesical instillation, RAG-01 utilizes Ractigen’s proprietary lipid-conjugated oligonucleotide (LiCO) delivery technology, which effectively penetrates the glycosaminoglycan layer lining the bladder, delivering the saRNA directly to the urothelial cells. This localized delivery ensures a high concentration of the drug in the bladder, minimizing systemic exposure and potential side effects. Preclinical studies showed that RAG-01 significantly inhibited bladder tumor growth in animal models and demonstrated good safety.27

RAG-01, the second saRNA drug to enter clinical trials after MTL-CEBPA, received FDA approval for its Investigational New Drug (IND) application and the Fast Track Designation and is currently undergoing a phase I clinical trial in Australia for NMIBC. This trial is an open-label, multi-center study designed to assess RAG-01’s safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and preliminary efficacy in NMIBC patients who have failed BCG therapy (NCT06351904). Initiated in December 2023, the trial has enrolled and dosed six patients, with initial results indicating a favorable safety profile after the first treatment cycle.117,118 RAG-01 represents a promising new approach to addressing high recurrence rates in NMIBC through targeted gene upregulation.

Delivery strategies of saRNA

To achieve high-efficiency drug delivery, chemical modification, bioconjugation, and nanocarriers are critical approaches applied in oligonucleotide drug development. A reliable delivery strategy promises to improve tissue pharmacokinetics (PK) and increase cell uptake and subsequent endosomal escape.75,119 Over the years, there have been attempts at different strategies delivering saRNA for therapeutic purposes (reviewed in Pandey, 2024 #116).120 In this section, we only discuss the delivery methods used for two clinical stage saRNAs.

Delivery of CEBPA-saRNA

MTL-CEBPA, a well-studied clinical saRNA drug candidate for HCC and other solid tumors,20,26,121 is produced by formulating the CEBPA-51 saRNA in liposomal nanoparticles called SMARTICLES.122 SMARTICLES is an amphoteric lipid system with a charge reversible character: cationic lipid provides cationic charge at a low pH, and anionic lipids are pH-sensitive and amphiphilic.123 The same CEPBA-saRNA has been tested for treating pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). For delivery to the pancreas, the saRNA was conjugated with the anti-hTfR RNA aptamer (TR14).124 Intravenous administration of such saRNA conjugate achieved inhibition of pancreatic tumors established in immunocompromised mice by injecting the tumor cell into the liver. Another group125 developed tetrahedral framework nucleic acid (tFNA)-based nanocarriers that were further functionalized with a truncated transferrin receptor aptamer (tTR14) to enhance targeting specificity for PDAC cells. They showed that i.v. administration of CEBPA-saRNA formulated in the tTR14-decorated tFNA effectively upregulated the expression of the CEBPA in xenograft PDAC tumors and inhibited tumor growth.

Delivery of p21 saRNA

Another well-studied saRNA is dsP21-322, which targets the p21 promoter at the −322 location.1 Initially, dsP21-322 formulated in lipidoid nanoparticles, a class of liposomal-like molecules prepared with lipidoid 95N12-5(1), cholesterol, mPEG2000-C14, and saRNA using a spontaneous vesicle formation formulation procedure, was shown to inhibit xenograft prostate cancer growth via intratumoral injection.97 Subsequently, dsP21-322 was formulated in ionizable cationic liposomes (KC2 LNP) and administrated via intravesical instillation to mice bearing orthotopic bladder cancer. Repeated instillations caused significant inhibition of tumor growth or tumor regression in the bladder.126

The clinical stage p21 saRNA RAG-01 is delivered using a proprietary LiCO delivery system. This system features a lipid molecule conjugated to duplex RNA via a benzimidazole linker for intravesical administration.127

Conclusions and perspectives

The field of RNAa has progressed significantly, offering a wealth of opportunities both in basic research and clinical therapeutics. The mechanisms underlying RNAa, facilitated by saRNAs and miRNAs, have expanded our understanding of gene regulation, challenging the traditional view that small RNAs function solely as gene silencers. RNAa represents a powerful tool for gene upregulation, with evolutionary conservation across a range of species, including mammals and insects, indicating its fundamental biological importance.

One of the most promising prospects for saRNA technology lies in its therapeutic applications, particularly in the treatment of cancer, genetic and metabolic disorders, and other chronic conditions. saRNAs, such as MTL-CEBPA and RAG-01, have progressed into clinical trials, underscoring their potential to upregulate critical tumor suppressor genes and enhance patient outcomes. These saRNAs specifically target genes that are considered undruggable by conventional therapeutic modalities at the transcriptional level, offering a novel approach to treating diseases that have proved challenging to manage with traditional methods. This innovative strategy not only expands the therapeutic landscape but also holds the promise of more effective interventions for previously intractable conditions.

Despite these advancements, challenges remain. A clearer understanding of the nuclear import mechanisms of saRNAs and their interactions with key proteins like AGO2 is essential to fully harness RNAa’s potential. Additionally, while RNAa has demonstrated promising results in early clinical trials, more research is needed to refine saRNA delivery systems, ensuring that they are both safe and effective in a broader range of diseases. Continued exploration of mi-RNAa’s role in cellular processes will deepen our understanding of gene regulation and facilitate the development of new therapeutics. As research progresses, RNAa stands poised to transform molecular medicine, offering innovative solutions to some of the most pressing challenges in healthcare.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 91540106 and No. 31872815, to L.-C.L).

Author contributions

L.-C.L. conceived the project. L.-C.L., Y.Q., C.L., and X.Z. wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

L.C.L. holds shares in Ractigen Therapeutics.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT in order to improve language. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Contributor Information

Xuhui Zeng, Email: zengxuhui@ntu.edu.cn.

Long-Cheng Li, Email: lilc@ractigen.com.

References

- 1.Li L.C., Okino S.T., Zhao H., Pookot D., Place R.F., Urakami S., Enokida H., Dahiya R. Small dsRNAs induce transcriptional activation in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:17337–17342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607015103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janowski B.A., Younger S.T., Hardy D.B., Ram R., Huffman K.E., Corey D.R. Activating gene expression in mammalian cells with promoter-targeted duplex RNAs. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:166–173. doi: 10.1038/nchembio860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Place R.F., Li L.C., Pookot D., Noonan E.J., Dahiya R. MicroRNA-373 induces expression of genes with complementary promoter sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:1608–1613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707594105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang V., Place R.F., Portnoy V., Wang J., Qi Z., Jia Z., Yu A., Shuman M., Yu J., Li L.C. Upregulation of Cyclin B1 by miRNA and its implications in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:1695–1707. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Portnoy V., Lin S.H.S., Li K.H., Burlingame A., Hu Z.H., Li H., Li L.C. saRNA-guided Ago2 targets the RITA complex to promoters to stimulate transcription. Cell Res. 2016;26:320–335. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohno S.I., Oikawa K., Tsurui T., Harada Y., Ono K., Tateishi M., Mirza A., Takanashi M., Kanekura K., Nagase K., et al. Nuclear microRNAs release paused Pol II via the DDX21-CDK9 complex. Cell Rep. 2022;39 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu Y., Yue X., Younger S.T., Janowski B.A., Corey D.R. Involvement of argonaute proteins in gene silencing and activation by RNAs complementary to a non-coding transcript at the progesterone receptor promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7736–7748. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu H.L., Li S.M., Hu J., Yu X., Xu H., Chen Z., Ye Z.Q. Demystifying the mechanistic and functional aspects of p21 gene activation with double-stranded RNAs in human cancer cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;35:145. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0423-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo J., Ji Y., Chen N., Song G., Zhou S., Niu X., Yu D. Nuclear miR-150 enhances hepatic lipid accumulation by targeting RNA transcripts overlapping the PLIN2 promoter. iScience. 2023;26 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.107837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaluvally-Raghavan P., Jeong K.J., Pradeep S., Silva A.M., Yu S., Liu W., Moss T., Rodriguez-Aguayo C., Zhang D., Ram P., et al. Direct Upregulation of STAT3 by MicroRNA-551b-3p Deregulates Growth and Metastasis of Ovarian Cancer. Cell Rep. 2016;15:1493–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang V., Zheng J., Qi Z., Wang J., Place R.F., Yu J., Li H., Li L.C. Ago1 Interacts with RNA polymerase II and binds to the promoters of actively transcribed genes in human cancer cells. PLoS Genet. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Place R.F., Noonan E.J., Földes-Papp Z., Li L.C. Defining features and exploring chemical modifications to manipulate RNAa activity. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2010;11:518–526. doi: 10.2174/138920110791591463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Portnoy V., Huang V., Place R.F., Li L.C. Small RNA and transcriptional upregulation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2011;2:748–760. doi: 10.1002/wrna.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janowski B.A., Huffman K.E., Schwartz J.C., Ram R., Hardy D., Shames D.S., Minna J.D., Corey D.R. Inhibiting gene expression at transcription start sites in chromosomal DNA with antigene RNAs. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005;1:216–222. doi: 10.1038/nchembio725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris K.V., Chan S.W.L., Jacobsen S.E., Looney D.J. Small interfering RNA-induced transcriptional gene silencing in human cells. Science. 2004;305:1289–1292. doi: 10.1126/science.1101372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrikakou P., Reebye V., Vasconcelos D., Yoon S., Voutila J., George A.J.T., Swiderski P., Habib R., Catley M., Blakey D., et al. Enhancing SIRT1 Gene Expression Using Small Activating RNAs: A Novel Approach for Reversing Metabolic Syndrome. Nucleic Acid Therapeut. 2022;32:486–496. doi: 10.1089/nat.2021.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y.L., Kang M., Wu J.C., Xie M.Y., Xue R.Y., Tang Q., Yang H., Li L.C. Small activating RNA activation of ATOH1 promotes regeneration of human inner ear hair cells. Bioengineered. 2022;13:6729–6739. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2022.2045835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bi C.Q., Kang T., Qian Y.K., Kang M., Zeng X.H., Li L.C. Upregulation of LHPP by saRNA inhibited hepatocellular cancer cell proliferation and xenograft tumor growth. PLoS One. 2024;19 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0299522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashimoto A., Sarker D., Reebye V., Jarvis S., Sodergren M.H., Kossenkov A., Sanseviero E., Raulf N., Vasara J., Andrikakou P., et al. Upregulation of C/EBPalpha Inhibits Suppressive Activity of Myeloid Cells and Potentiates Antitumor Response in Mice and Patients with Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021;27:5961–5978. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang K., Shen J., Tan F.Q., Zheng X.Y., Xie L.P. Antitumor Activity of Small Activating RNAs Induced PAWR Gene Activation in Human Bladder Cancer Cells. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2021;18:3039–3049. doi: 10.7150/ijms.60399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park K.H., Yang J.W., Kwon J.H., Lee H., Yoon Y.D., Choi B.J., Lee M.Y., Lee C.W., Han S.B., Kang J.S. Targeted Induction of Endogenous VDUP1 by Small Activating RNA Inhibits the Growth of Lung Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms23147743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L., Lin Y., Yao Z., Babu N., Lin W., Chen C., Du L., Cai S., Pan Y., Xiong X., et al. Targeting undruggable phosphatase overcomes trastuzumab resistance by inhibiting multi-oncogenic kinases. Drug Resist. Updates. 2024;76 doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2024.101118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su R., Wen Z., Zhan X., Long Y., Wang X., Li C., Su Y., Fei J. Small RNA activation of CDH13 expression overcome BCR-ABL1-independent imatinib-resistance and their signaling pathway studies in chronic myeloid leukemia. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15:615. doi: 10.1038/s41419-024-07006-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu H., Chen S., Sun Q., Sha Q., Tang Y., Jia W., Chen L., Zhao J., Wang T., Sun X. Let-7c increases BACE2 expression by RNAa and decreases Abeta production. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2022;14:899–908. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarker D., Plummer R., Meyer T., Sodergren M.H., Basu B., Chee C.E., Huang K.W., Palmer D.H., Ma Y.T., Evans T.R.J., et al. MTL-CEBPA, a Small Activating RNA Therapeutic Upregulating C/EBP-alpha, in Patients with Advanced Liver Cancer: A First-in-Human, Multicenter, Open-Label, Phase I Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;26:3936–3946. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.PR Newswire Ractigen Therapeutics Announces FDA Approval for RAG-01, a First-in-Class saRNA Therapy for BCG-Unresponsive NMIBC. 2024. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/ractigen-therapeutics-announces-fda-approval-for-rag-01-a-first-in-class-sarna-therapy-for-bcg-unresponsive-nmibc-302128680.html

- 28.Xie Y., Zheng M., Chu X., Chen Y., Xu H., Wang J., Zhou H., Long J. Paf1 and Ctr9 subcomplex formation is essential for Paf1 complex assembly and functional regulation. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3795. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06237-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Francette A.M., Tripplehorn S.A., Arndt K.M. The Paf1 Complex: A Keystone of Nuclear Regulation Operating at the Interface of Transcription and Chromatin. J. Mol. Biol. 2021;433 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.166979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao X., Reebye V., Hitchen P., Fan J., Jiang H., Sætrom P., Rossi J., Habib N.A., Huang K.W. Mechanisms involved in the activation of C/EBPalpha by small activating RNA in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2019;38:3446–3457. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0665-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voutila J., Reebye V., Roberts T.C., Protopapa P., Andrikakou P., Blakey D.C., Habib R., Huber H., Saetrom P., Rossi J.J., Habib N.A. Development and Mechanism of Small Activating RNA Targeting CEBPA, a Novel Therapeutic in Clinical Trials for Liver Cancer. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:2705–2714. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang V., Qin Y., Wang J., Wang X., Place R.F., Lin G., Lue T.F., Li L.C. RNAa is conserved in mammalian cells. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Claycomb J.M., Batista P.J., Pang K.M., Gu W., Vasale J.J., van Wolfswinkel J.C., Chaves D.A., Shirayama M., Mitani S., Ketting R.F., et al. The Argonaute CSR-1 and its 22G-RNA cofactors are required for holocentric chromosome segregation. Cell. 2009;139:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seth M., Shirayama M., Gu W., Ishidate T., Conte D., Jr., Mello C.C. The C. elegans CSR-1 argonaute pathway counteracts epigenetic silencing to promote germline gene expression. Dev. Cell. 2013;27:656–663. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wedeles C.J., Wu M.Z., Claycomb J.M. Protection of germline gene expression by the C. elegans Argonaute CSR-1. Dev. Cell. 2013;27:664–671. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shibuya K., Fukushima S., Takatsuji H. RNA-directed DNA methylation induces transcriptional activation in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:1660–1665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809294106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Hayr L., Asad S., Hussain M., Asgari S. RNA activation in insects: The targeted activation of endogenous and exogenous genes. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020;119 doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2020.103325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwofie K.D., Hernandez E.P., Anisuzzaman, Kawada H., Kawada H., Koike Y., Sasaki S., Inoue T., Jimbo K., Ladzekpo D., et al. RNA activation in ticks. Sci. Rep. 2023;13:9341. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-36523-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castanotto D., Lingeman R., Riggs A.D., Rossi J.J. CRM1 mediates nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of mature microRNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:21655–21659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912384106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei Y., Li L., Wang D., Zhang C.Y., Zen K. Importin 8 regulates the transport of mature microRNAs into the cell nucleus. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:10270–10275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C113.541417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weinmann L., Höck J., Ivacevic T., Ohrt T., Mütze J., Schwille P., Kremmer E., Benes V., Urlaub H., Meister G. Importin 8 is a gene silencing factor that targets argonaute proteins to distinct mRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:496–507. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okada C., Yamashita E., Lee S.J., Shibata S., Katahira J., Nakagawa A., Yoneda Y., Tsukihara T. A high-resolution structure of the pre-microRNA nuclear export machinery. Science. 2009;326:1275–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.1178705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang V., Li L.C. miRNA goes nuclear. RNA Biol. 2012;9:269–273. doi: 10.4161/rna.19354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liao J.Y., Ma L.M., Guo Y.H., Zhang Y.C., Zhou H., Shao P., Chen Y.Q., Qu L.H. Deep sequencing of human nuclear and cytoplasmic small RNAs reveals an unexpectedly complex subcellular distribution of miRNAs and tRNA 3' trailers. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turunen T.A., Roberts T.C., Laitinen P., Väänänen M.A., Korhonen P., Malm T., Ylä-Herttuala S., Turunen M.P. Changes in nuclear and cytoplasmic microRNA distribution in response to hypoxic stress. Sci. Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46841-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parashar D., Geethadevi A., Aure M.R., Mishra J., George J., Chen C., Mishra M.K., Tahiri A., Zhao W., Nair B., et al. miRNA551b-3p Activates an Oncostatin Signaling Module for the Progression of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cell Rep. 2019;29:4389–4406.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.11.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hwang H.W., Wentzel E.A., Mendell J.T. A hexanucleotide element directs microRNA nuclear import. Science. 2007;315:97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1136235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park C.W., Zeng Y., Zhang X., Subramanian S., Steer C.J. Mature microRNAs identified in highly purified nuclei from HCT116 colon cancer cells. RNA Biol. 2010;7:606–614. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.5.13215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Castanotto D., Zhang X., Alluin J., Zhang X., Rüger J., Armstrong B., Rossi J., Riggs A., Stein C.A. A stress-induced response complex (SIRC) shuttles miRNAs, siRNAs, and oligonucleotides to the nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E5756–E5765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1721346115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turner M.J., Jiao A.L., Slack F.J. Autoregulation of lin-4 microRNA transcription by RNA activation (RNAa) in C. elegans. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:772–781. doi: 10.4161/cc.27679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiao A.L., Foster D.J., Dixon J., Slack F.J. lin-4 and the NRDE pathway are required to activate a transgenic lin-4 reporter but not the endogenous lin-4 locus in C. elegans. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dharap A., Pokrzywa C., Murali S., Pandi G., Vemuganti R. MicroRNA miR-324-3p induces promoter-mediated expression of RelA gene. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang C., Tang K., Li Z., Chen Z., Xu H., Ye Z. Targeted p21(WAF1/CIP1) activation by miR-1236 inhibits cell proliferation and correlates with favorable survival in renal cell carcinoma. Urol. Oncol. 2016;34:59.e23-34. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li S., Wang C., Yu X., Wu H., Hu J., Wang S., Ye Z. miR-3619-5p inhibits prostate cancer cell growth by activating CDKN1A expression. Oncol. Rep. 2017;37:241–248. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.5250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kang M.R., Park K.H., Yang J.O., Lee C.W., Oh S.J., Yun J., Lee M.Y., Han S.B., Kang J.S. miR-6734 Up-Regulates p21 Gene Expression and Induces Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Colon Cancer Cells. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang C., Chen Z., Ge Q., Hu J., Li F., Hu J., Xu H., Ye Z., Li L.-C. RETRACTED: Up-regulation of p21WAF1/CIP1 by miRNAs and its implications in bladder cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:4654–4664. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li C., Ge Q., Liu J., Zhang Q., Wang C., Cui K., Chen Z. Effects of miR-1236-3p and miR-370-5p on activation of p21 in various tumors and its inhibition on the growth of lung cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2017;39 doi: 10.1177/1010428317710824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu M., Roth A., Yu M., Morris R., Bersani F., Rivera M.N., Lu J., Shioda T., Vasudevan S., Ramaswamy S., et al. The IGF2 intronic miR-483 selectively enhances transcription from IGF2 fetal promoters and enhances tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2543–2548. doi: 10.1101/gad.224170.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Y., Zhang H. RNAa Induced by TATA Box-Targeting MicroRNAs. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017;983:91–111. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-4310-9_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Y., Fan M., Zhang X., Huang F., Wu K., Zhang J., Liu J., Huang Z., Luo H., Tao L., Zhang H. Cellular microRNAs up-regulate transcription via interaction with promoter TATA-box motifs. RNA. 2014;20:1878–1889. doi: 10.1261/rna.045633.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Matsui M., Chu Y., Zhang H., Gagnon K.T., Shaikh S., Kuchimanchi S., Manoharan M., Corey D.R., Janowski B.A. Promoter RNA links transcriptional regulation of inflammatory pathway genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:10086–10109. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li S., Zhu Y., Liang Z., Wang X., Meng S., Xu X., Xu X., Wu J., Ji A., Hu Z., et al. Up-regulation of p16 by miR-877-3p inhibits proliferation of bladder cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:51773–51783. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang Y., Liu W., Chen Y., Liu J., Wu K., Su L., Zhang W., Jiang Y., Zhang X., Zhang Y., et al. A Cellular MicroRNA Facilitates Regulatory T Lymphocyte Development by Targeting the FOXP3 Promoter TATA-Box Motif. J. Immunol. 2018;200:1053–1063. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gernapudi R., Wolfson B., Zhang Y., Yao Y., Yang P., Asahara H., Zhou Q. MicroRNA 140 Promotes Expression of Long Noncoding RNA NEAT1 in Adipogenesis. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;36:30–38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00702-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Y., Fan M., Geng G., Liu B., Huang Z., Luo H., Zhou J., Guo X., Cai W., Zhang H. A novel HIV-1-encoded microRNA enhances its viral replication by targeting the TATA box region. Retrovirology. 2014;11:23. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-11-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang S., Li Y., Zeng Q., Yang L., Du X., Li Q. A Mutation in Endogenous saRNA miR-23a Influences Granulosa Cells Response to Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants. 2022;11 doi: 10.3390/antiox11061174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang M., Wang Y., Yang L., Du X., Li Q. Nuclear lncRNA NORSF reduces E2 release in granulosa cells by sponging the endogenous small activating RNA miR-339. BMC Biol. 2023;21:221. doi: 10.1186/s12915-023-01731-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li H., Fan J., Zhao Y., Zhang X., Dai B., Zhan J., Yin Z., Nie X., Fu X.D., Chen C., Wang D.W. Nuclear miR-320 Mediates Diabetes-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction by Activating Transcription of Fatty Acid Metabolic Genes to Cause Lipotoxicity in the Heart. Circ. Res. 2019;125:1106–1120. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.314898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhai P., Tong T., Wang X., Li C., Liu C., Qin X., Li S., Xie F., Mao J., Zhang J., Guo H. Nuclear miR-451a activates KDM7A and leads to cetuximab resistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024;81:282. doi: 10.1007/s00018-024-05324-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tao L., Wang Y., Shen Z., Cai J., Zheng J., Xia S., Lin Z., Wan Z., Qi H., Jin R., et al. Activation of IGFBP4 via unconventional mechanism of miRNA attenuates metastasis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatol. Int. 2024;18:91–107. doi: 10.1007/s12072-023-10552-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sarkar N., Mishra R., Gopal C., Kumar A. miR-617 interacts with the promoter of DDX27 and positively regulates its expression: implications for cancer therapeutics. Front. Oncol. 2024;14 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1411539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang Y., Tian F., Yue S., Li J., Li A., Liu Y., Liang J., Gao Y., Xue S. miR-17-5p-Mediated RNA Activation Upregulates KPNA2 Expression and Inhibits High-Glucose-Induced Apoptosis of Sheep Granulosa Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025;26 doi: 10.3390/ijms26030943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zou Q., Liang Y., Luo H., Yu W. miRNA-Mediated RNAa by Targeting Enhancers. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017;983:113–125. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-4310-9_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xiao M., Li J., Li W., Wang Y., Wu F., Xi Y., Zhang L., Ding C., Luo H., Li Y., et al. MicroRNAs activate gene transcription epigenetically as an enhancer trigger. RNA Biol. 2017;14:1326–1334. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1112487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Roberts T.C., Langer R., Wood M.J.A. Advances in oligonucleotide drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020;19:673–694. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-0075-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liang Y., Lu Q., Li W., Zhang D., Zhang F., Zou Q., Chen L., Tong Y., Liu M., Wang S., et al. Reactivation of tumour suppressor in breast cancer by enhancer switching through NamiRNA network. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:8556–8572. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xiao T., Meng W., Jin Z., Wang J., Deng J., Wen J., Liu B., Liu M., Bai J., Liu F. miR-182-5p promotes hepatocyte-stellate cell crosstalk to facilitate liver regeneration. Commun. Biol. 2022;5:771. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-03714-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]