Abstract

Synaptic failure in specific cholinergic networks in rat brains has been implicated in amyloid β-induced neurodegeneration. Teucrium polium is a promising candidate for drug development against Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and similar disorders. However, the protective effect of Teucrium polium against amyloid β-induced impairment of short-term synaptic plasticity is still poorly understood. In this study, we used in vivo extracellular single-unit recordings to investigate the preventive efficacy of Teucrium polium on Aβ(25–35)-induced aberrant neuronal activity in the hippocampus and basolateral amygdala of rats, in response to high-frequency stimulation of the cholinergic nucleus basalis magnocellularis (NBM). After 12 weeks of intracerebroventricular administration of Aβ(25–35), alterations such as decreased excitatory responses and increased inhibitory synaptic activity were observed in the NBM–hippocampus and NBM–basolateral amygdala cholinergic circuits. Treatment with Teucrium polium improved the balance of excitatory and inhibitory responses by modulating synaptic transmission strength and restoring short-term plasticity. Acute injection of a therapeutic dose of Teucrium temporarily inhibited spiking activity in single NBM neurons. Open field tests revealed that amyloid-injected rats displayed anxiety and reduced exploratory drive. Treatment with Teucrium polium improved these behaviors, reducing anxiety and increasing exploration. Teucrium polium mitigated amyloid β-induced alterations in cholinergic circuits by enhancing the adaptive capacity of short-term synaptic plasticity. These findings suggest that Teucrium polium could serve as a preventive strategy to delay the progression of cholinergic neurodegeneration.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12906-024-04715-8.

Keywords: Amyloid β(25–35), Teucrium Polium, nAChR, Spike activity, Nucleus basalis magnocellularis

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases are complex disorders involving dysregulation of various biological processes, such as cell signaling, apoptosis, and the accumulation of misfolded proteins prone to aggregation [1]. Recent studies indicate that homeostatic synaptic plasticity, which helps maintain the stability of synaptic function, is also involved in neurodegenerative diseases. In this context, the lack of proper homeostatic plasticity in deteriorating synapses exacerbates disease progression, as the inherent plasticity of the overall synaptic population is crucial for preserving function [2]. Under pathological conditions, homeostatic synaptic plasticity plays a vital role in maintaining the stability and efficiency of information transmission within neuronal networks [3]. The stabilization of neuronal circuit functions is achieved through modifications of pre- and postsynaptic properties of neuronal units, accomplished by anterograde and retrograde signaling systems (acting in pre- and postsynaptic regions) to establish homeostatic control of neurotransmission, as well as through the postsynaptic localization of receptors and optimal adjustments of overall neuronal activity levels [4–6]. We evaluated these mechanisms in populations of neurons with similar response types across the compared groups. Understanding the various forms of homeostatic plasticity in neurodegenerative disorders not only enhances our comprehension of pathogenic mechanisms but also offers potential for new therapeutic strategies. Kavalali et al. highlighted the correlations between neuropsychiatric therapeutic approaches and homeostatic plasticity research, which could lead to the development of new paradigms for therapy [7].

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an age-related neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the gradual decline of cognitive functions. The development and progression of AD involve various intricate pathogenic pathways, such as the formation of plaques, activation of inflammatory processes, deficits in the cholinergic system, and increased oxidative stress. Due to the multifactorial nature of AD, it is crucial to adopt a broader approach that utilizes pleiotropic compounds, particularly those derived from plants, to address the complexity of the disease [8]. Notably, findings from patient studies indicate that the inclusion of complementary herbal therapies alongside conventional medications provides longer-lasting benefits compared to conventional therapy alone [9].

Secondary metabolites produced by plants exhibit distinctive chemical properties and possess potent bioactivities. These compounds have been utilized for centuries in the treatment of various diseases and continue to be the subject of ongoing research to explore their potential therapeutic advantages [10]. Recently, there has been significant screening of numerous plants and their crude extracts to assess their potential as anticholinesterase (anti-ChE) agents. These studies have demonstrated notable pharmacological effects, particularly in combating AD [11]. Most research has focused on anti-ChE inhibitor alkaloids, such as physostigmine and galantamine. However, other major classes of natural compounds with similar activities include those from the Lamiaceae family, which are rich in glycosides and flavonoids [12, 13]. Researchers are increasingly drawn to investigate the plant kingdom due to the diverse bioactivities exhibited by natural products, which hold potential for human health benefits. Specifically, there is growing interest in exploring phenylpropanoid glycosides and their potential roles in clinical drug development.

In most patients with clinical AD, an early pathological occurrence is the impairment of cholinoceptive function, which involves the dysfunction and depletion of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain and their associated projections [14–16]. The decline, disruption, or modifications of cholinergic mechanisms have been linked to the “cholinergic hypothesis” of AD [17]. The density of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs)—transmembrane oligomeric ligand-gated ion channels—as well as the levels of acetylcholine (ACh), the ligand for nAChRs, decrease as Alzheimer’s disease advances [18]. Additionally, Aβ is known to bind to and modulate nAChRs [19]. Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) is a highly desirable feature of AD therapy [20, 21]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that AChE promotes amyloid β (Aβ) aggregation, and a significant increase in the cortical levels of BuChE has been found to be associated with neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles [22]. The importance of BuChE in cholinergic neurotransmission is likely to increase in AD, as AChE activity decreases by up to 45% and BuChE activity increases by 40–90% as the disease progresses [23]. Both AChE and BuChE appear to be simultaneously active in the synaptic hydrolysis of ACh, terminating its neurotransmitter action and co-regulating ACh levels [24]. Consequently, both AChE and BuChE are recognized as viable targets for therapeutic interventions aimed at alleviating the cholinergic deficit responsible for the overall decline in functioning observed in AD. As a result, the development of therapeutic approaches targeting AChE and BuChE inhibitors has gained considerable attention as a crucial strategy in AD treatment. Some AChE inhibitors currently in clinical trials also target additional qualities, including antioxidant properties, β-secretase inhibitory properties, prevention of Aβ aggregation, and tau hyperphosphorylation [25].

Teucrium polium L. (Lamiaceae) is widely recognized as one of the most commonly used herbal medicines globally. With a history of over 2000 years in traditional medicine, it has gained popularity due to its remarkable pharmacological properties. Notably, Teucrium polium is traditionally employed in folk medicine to enhance cognitive function and mental performance. Recent research indicates that Teucrium polium from the Lamiaceae family holds promise as a potential alternative medicine for the treatment and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease and related conditions [26–30]. Cholinesterase inhibitors from Lamiaceae family plants have been evaluated, with several terpenoids and phenolic/flavonoid compounds identified as potential drugs for the treatment of AD [31]. The AChE inhibitory activity of Teucrium polium may be attributed to its richness in polyphenols, as members of the Lamiaceae family are known to contain high levels of phenolic acids. These active constituents significantly contribute to the neuroprotective properties of Teucrium polium [12]. The ethanol extract of Teucrium polium has also been reported to exhibit high AChE and BChE inhibitory activities [12, 28, 32, 33].

Teucrium polium (golden germander) growing in Armenia has a unique phytochemical composition. In 1991, Oganesyan et al. isolated verbascoside, a new phenylpropanoid glycoside named teupolioside, and poliumoside from golden germander for the first time [34]. The main compounds of the Armenian Teucrium polium include phenylpropanoid glycosides such as verbascoside, polyumoside, and teupolyoside, which can reach concentrations of up to 6.0%. The plant also contains a small amount of diterpene furolactones (tepolin A and B), at approximately 0.9%. These compounds exhibit high biological activity [35, 36]. Medicinal plants containing phenylpropanoid glycosides have been shown to possess a wide spectrum of pharmacological effects, including antioxidant, antibacterial, antitumor, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, hepatoprotective, immunomodulatory, and tyrosinase inhibitory actions [37]. We have previously demonstrated that hydroponic Teucrium polium reduced neurodegenerative alterations induced by ovariectomy in the entorhinal cortex-hippocampal circuitry [38]. The dynamics of psycho-emotional states and cognitive processes were also studied in middle-aged women before and after treatment with a water fraction of an ethanol extract of hydroponic Teucrium polium (for 20 days). Administration of the extract was associated with improvements in short-term memory characteristics, increased brain efficiency in attention and concentration tasks, and a simultaneous increase in the speed of analysis, synthesis, and information processing in higher brain centers [39].

The progression of AD and memory performance cannot be explained by synaptic or neuronal loss alone; compensatory mechanisms, such as synaptic scaling, also play a role at the microcircuit level [40]. The adaptive and maladaptive changes at the intercellular level in mediating and modulating amyloid-beta (Aβ)-induced modifications of synaptic function and plasticity require focused assessment [41]. The electrophysiological correlates of Aβ-induced modifications of synaptic function in rat NBM-hippocampal circuits have been revealed [42]. The aims of this study were: (1) to evaluate synaptic activity in hippocampal and basolateral amygdala neurons using in vivo single-unit extracellular electrophysiology to investigate the effects of high-frequency stimulation (HFS) of the cholinergic NBM on synaptic activity in these neurons in rats with amyloid β(25–35) intoxication and Teucrium polium therapy, and (2) to investigate the effects of chronic (12-week) amyloid β(25–35) intoxication and Teucrium polium phytotherapy on behavior.

Materials and methods

Experimental materials

All chemicals used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Preparation of the plant extract and Teucrium polium injection

Teucrium polium was used in this study and was collected from the G.S. Davtyan Institute of Hydroponics Problems of the NAS RA. The plants were cultivated using hydroponic methods, which are known for their ability to yield higher quantities. Harvesting took place between August and October 2021 at the renowned production site for Teucrium polium in Armenia. The plant material was botanically identified by Dr. H. Galstyan, a senior researcher at the G.S. Davtyan Institute of Hydroponics Problems in Yerevan, Armenia. A voucher specimen was deposited at the Herbarium of the G.S. Davtyan Institute of Hydroponics Problems of the NAS RA (outdoor hydroponics, Experimental Hydroponic Station). Experimental research on the plants was performed following the relevant guidelines and legislation [43]. The study found that the main biologically active compounds of Teucrium polium include phenylpropanoid glycosides—verbascoside, poliumoside, and teupolioside. Additionally, flavonoid and phenylpropanoid glycosides were identified in hydroponic Teucrium polium [36, 38]. For the study, 50% ethyl alcohol-soluble extracts were prepared from wild, hydroponic, and soil-grown Teucrium polium. These extracts were subsequently dried using a rotary vacuum evaporator and further fractionated into benzene, ethyl acetate, chloroform-methanol (3:1), and aqueous fractions. Hydroponic Teucrium polium was found to be less toxic and contained active ingredients. The therapeutic investigations focused on the aqueous fraction of the ethanol extract, specifically targeting flavonoid glycosides and phenolic glycosides within this fraction. The therapeutic dose of hydroponic Teucrium polium was determined to be 5% of the maximum endurable dose, corresponding to 400 mg/kg (equivalent to 20 mg/kg) [44]. The water fraction of the ethanol extract from hydroponic Teucrium polium was prepared daily, diluted in sterile distilled water, and administered to rats via intramuscular injections in single doses of 0.5 ml [36, 44, 45].

Animals

Adult male Wistar albino rats weighing 200 ± 30 g were purchased from the experimental center of Orbeli Institute of Physiology NAS RA. The experiments were performed at the same time period of the day and during the light period of the light–dark cycle (09:00–18:00 h). The animals were maintained at 25 ± 2 °C, 12 h light – dark cycle and lights on 07:00–19:00 h. Food and water ad libitum was provided to the animals. All animal procedures were performed under the supervision of the institutional ethics committee of Yerevan State Medical University after Mkhitar Heratsi, Yerevan, Armenia (approved code: N4 IRB). The ARRIVE guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were also followed.

Experimental setup

Male albino rats were divided into four groups:

Vehicle-control group (n = 5): This group consisted of animals treated with the vehicle (double-distilled water).

Amyloid group (n = 5): The first experimental group received a single intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection of 3 µg of aggregated Aβ(25–35) in 3 µl in each ventricle.

Amyloid + Teucriumgroup (n = 5): The animals in this group were intramuscularly injected with Teucrium (20 mg/kg body weight, 0.5 ml) immediately after the Aβ(25–35) injection and every day for the first 3 weeks (5 days per week).

Vehicle + Teucriumgroup (n = 5): Animals in this group, treated with the vehicle, received daily intramuscular injections of Teucrium (20 mg/kg body weight) during the first 3 weeks (5 days per week).

Teucrium single injection group (n = 6): Animals in this group received a single intramuscular injection of an aqueous fraction of the ethanol extract of Teucrium polium (20 mg/kg). The activity of rat NBM neurons was assessed, with a total of 6 NBM neurons being analyzed throughout the study.

In vivo electrophysiological studies of hippocampal and amygdala neurons were conducted after 12 weeks of Aβ(25–35) and vehicle infusions.

Animal models

Rats were intracerebroventricularly injected (i.c.v.) with Aβ(25–35) peptide (Sigma Aldrich, USA), following the procedure described by Maurice et al. [46]. Before each electrophysiological experiment, the rats underwent the open field test.

In vivo electrophysiology and data analysis

Electrophysiological studies were done after 12 weeks of intracerebroventricular injection of Aβ (25–35). The animals were anesthetized with urethane (1.1 g/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.), immobilized with 1% ditiline (25 mg/kg, i.p.), positioned in a stereotaxic frame, and placed on artificial ventilation. The sample of “encephaleisolé” rat was obtained by transection of the spinal cord (T2–T3) using ultrasound. A stimulating electrode was inserted according to stereotaxic coordinates [47] in the ipsilateral nucleus basalis magnocellularis (NBM) (AP − 1.08 to − 1.1, L ± 2.8 to 3.0, DV + 7.4 to 7.8 mm). A glass recording electrode (1 to 2 μm tip diameter) filled with 3 M KCl was repeatedly submerged into the hippocampal (coordinates AP − 3.3; L ± 1.5 to 3.5; DV 3.0 to 4.0) and basolateral amygdala neurons (at coordinates AP − 3.24; L ± 5.4 to 5.8; DV + 9.5 to 10.2) for recording spike activity flow of single neurons.High-frequency stimulation (HFS) (100 Hz for 1 s) was performed using a rectangular pulse charge of 0.05 milliseconds duration and 0.10 to 0.14 milliampere amplitude. Recording of impulse flow (spiking activity) was carried out using a program that provides spike selection by amplitude discrimination. This allows spikes to be identified and artifacts to be excluded during HFS, enabling evaluation of not only posttetanic but also tetanic activity. Neuronal impulse flow was subjected to software analysis, followed by output of the distributed real-time pre- and post-stimulus spike activity of single neurons. Histograms of mean frequency were then generated using multi-level statistical data processing (including frequency average ± standard deviation), differentiated for pre- and post-stimulus time, as well as tetanization time (the time of HFS during 1 s). The statistical significance of the heterogeneity of interspike intervals (or spike frequency) of the pre- and post-stimulus impulse flow was analyzed using Student’s t-test and Mann–Whitney U test, as described in our previous studies [42, 48]. A single neuron’s spike activity was recorded in real time for 30 s before stimulation (background activity), during high-frequency stimulation (HFS) for 1 s, and 30 s after stimulation (post-stimulus activity). Later, neurons with the same types of responses were grouped and averaged by software to create peri-stimulus histograms of mean frequency.

In general, electrophysiological data were obtained by recording 205 hippocampal and 69 basolateral amygdala neurons in the amyloid group, 135 hippocampal and 55 amygdala neurons in the amyloid + Teucrium polium group, 189 hippocampal and 77 amygdala neurons in the vehicle-control group, and 48 hippocampal and 43 amygdala neurons in the vehicle + Teucrium polium group. The impulse flow analysis revealed the formation of different combinations of responses in the form of impulse flow acceleration – tetanic potentiation (TP) and posttetanic potentiation (PTP), as well as impulse flow deceleration – tetanic depression (TD) and posttetanic depression (PTD), the expressiveness of which is estimated according to the value of the mean frequency in prestimulus time (M before stimulus – Mbs), post-stimulus time (M post stimulus – Mps), and tetanization time (M high-frequency stimulation – Mhfs) (Figs. 1, 2 and 3). Mixed combinations of responses (TP-PTD and TD-PTP) were recorded.

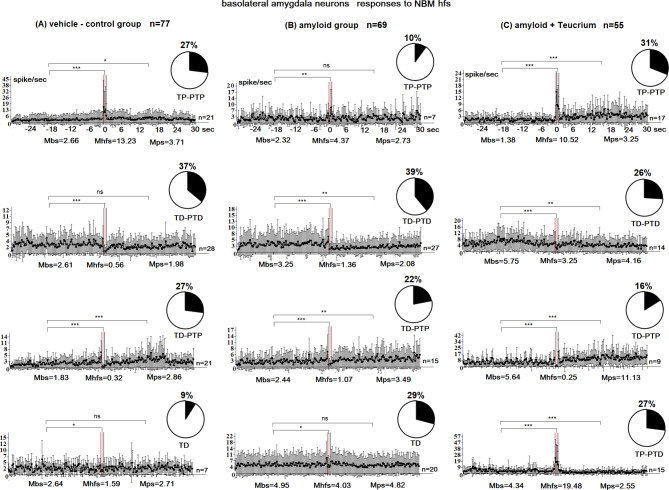

Fig. 1.

Peristimulus mean frequency diagrams in real time 30 s before stimulation (Mbs), 30 s after stimulation (Mps), and during high-frequency stimulation (Mhfs), built on the basis of pre-and post-stimulus manifestations of spike activity of single basolateral amygdala neurons to high-frequency stimulation of the nucleus basalis magnocellularis (NBM), exhibiting the specified types of responses (TD-PTD, TD-PTP, TP-PTP, TP-PTD, TD) in the vehicle control (A), amyloid (B), and amyloid + Teucrium polium (C) groups. n = number of neurons with this type of response; disks show percentage distribution of neurons with this type of response. The statistical significance of the response expression was estimated using Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001)

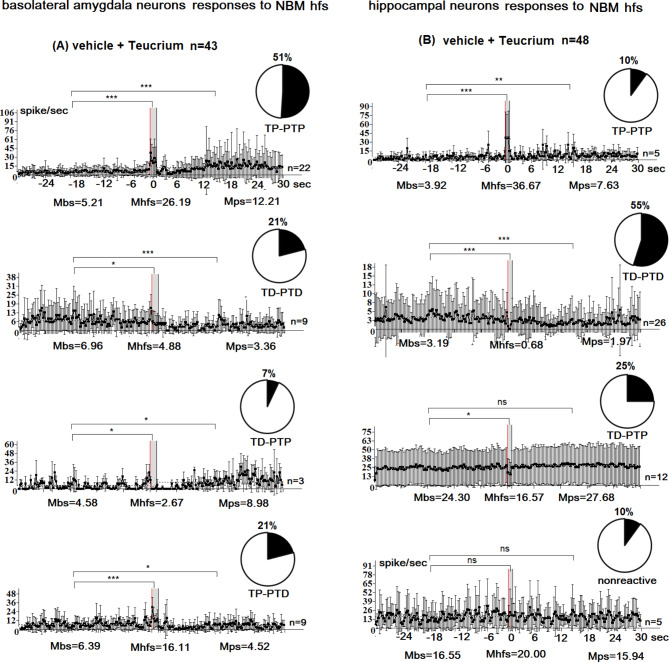

Fig. 2.

Peristimulus mean frequency diagrams in real time 30 s before stimulation (Mbs), 30 s after stimulation (Mps), and during high-frequency stimulation (Mhfs), built on the basis of pre-and post-stimulus manifestations of spike activity of single hippocampal neurons to high-frequency stimulation of the nucleus basalis magnocellularis (NBM), exhibiting the specified type of responses (TD-PTD, TD-PTP, TP-PTP, TP-PTD, TD) and non-reactivity in the vehicle control (A), amyloid (B), and amyloid + Teucrium polium (C) groups. n = number of neurons with this type of response; disks show percentage distribution of neurons with this type of response. The statistical significance of the response expression was estimated using Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001)

Fig. 3.

Peristimulus mean frequency diagrams in real time 30 s before stimulation (Mbs), 30 s after stimulation (Mps), and during high-frequency stimulation (Mhfs), built on the basis of pre-and post-stimulus manifestations of spike activity of single amygdala (A) and hippocampal (B) neurons to high-frequency stimulation of the nucleus basalis magnocellularis (NBM) exhibiting the specified type of responses (TD-PTD, TD-PTP, TP-PTP, and TP-PTD) and non-reactivity in the vehicle + Teucrium polium group. n = number of neurons with this type of response; disks show percentage distribution of neurons with this type of response. The statistical significance of the response expression was estimated according to the Student’s t-test; (*P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001)

Behavioral test

Open field test

Open field test (OF) was used to assess spontaneous exploratory activity and anxiety-related behaviors. The apparatus consisted of a black melamine square (60 × 60 cm) surrounded by walls that were 40 cm in height. A central area was arbitrarily defined as a square of 30 × 30 cm, and it was drawn over the image of in the video-tracking system. A rat was considered to be in the central area when four paws were on it. The light intensity at the center of the OF was 70–80 lx. Each rat was placed in the center of the maze and its behavior was analyzed for 5 min. The following dependent variables were recorded: total distance moved, the number of entries into the central area, and the time spent in the central area [49, 50]. All recorded videos were analyzed by AnyMaze software.

Statistical analysis

For electrophysiological data analysis we used t-criteria of Student’s t -test, the reliability of differences of interspike intervals before, after and during HFS. All p-values were determined by a two-sample unpaired Student’s t-test. The spread of the data where indicated is the SD of the mean. To increase reliability of statistical evaluations, we also used the non-parametric method of verification by application of Wilcoxon two sample test. Significant differences between the obtained values were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.0) using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Differences in the behavioral tests in different groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni test for intergroup comparisons.

Results

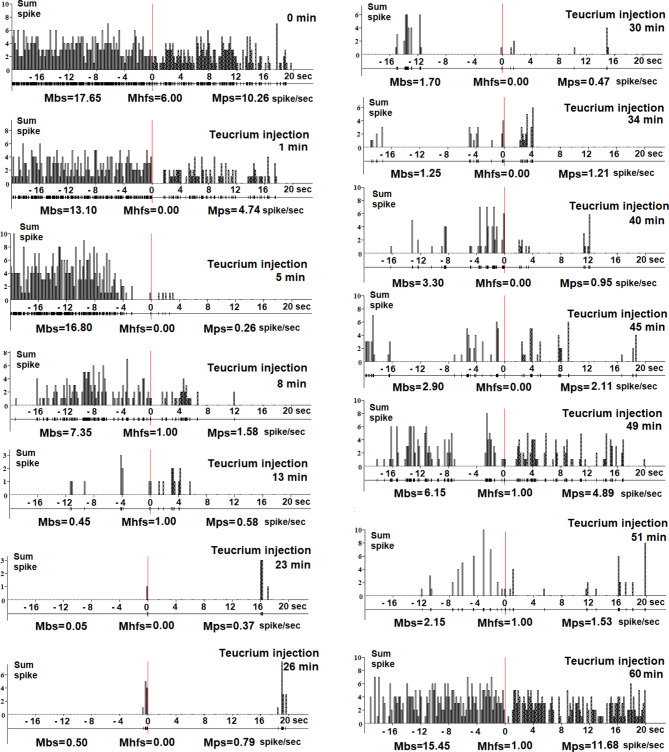

Electrophysiological study of the effects of a single systemic administration of a therapeutic dose of Teucrium Polium

In this study, we investigated the impact of a single intramuscular injection of an aqueous fraction of the ethanol extract of Teucrium polium L. on the activity of rat NBM neurons. A total of six neurons were examined. The objective was to assess changes in background and evoked spike activity kinetics during hippocampal high-frequency stimulation (HFS) following systemic injection of Teucrium. Individual NBM neurons were monitored for background and evoked spike activity over a duration of 1 to 90 min after administration of Teucrium at a dosage of 20 mg/kg intramuscularly (with a volume of 0.5 ml). Data analysis indicated inhibitory effects observed starting 2 min after the injection of Teucrium, followed by a restoration of spike activity frequency to baseline levels at 60–90 min. Figure 4 provides a detailed representation of the effects of a single administration of Teucrium, illustrating the real-time expansion of spike activity before (-20 to 0 s) and after (0 to 20 s) hippocampal HFS. The average spike frequency before stimulus (Mbs; spike/sec), during high-frequency stimulation (Mhfs; spike/sec), and post-stimulus average spike frequency (Mps; spike/sec) were calculated. A decrease in pre- and post-stimulus neuronal spike frequency was observed from 1 to 2 min after Teucrium administration compared to the initial spike activity (marked by 0 min – before Teucrium injection). Thus, inhibitory effects (with variability in the action period across different neuronal units, see Supplementary Figure) were detected in NBM neurons during a single Teucrium injection. This indicates the possibility of receptor desensitization or deactivation, followed by the restoration of initial spike activity in the cholinergic NBM neurons. We cannot exclude the possibility of other mechanisms of functional inactivation.

Fig. 4.

Dynamics (0–60 min) of changes in spike flow of single NBM neurons after injection of a therapeutic dose (20 mg/kg; i/m) of the ethanol extract of Teucrium polium. Analysis was based on baseline and hippocampal stimulation-induced spike activity of a single NBM neuron (n = 6): peristimulus histogram (sum spike); below-background and evoked spike activity of single NBM neuron in real time pre-stimulus (-20–0 s) and post-stimulus (0–20 s); Mbs - average spike frequency before stimulus (spike/s); Mhfs – average spike frequency during high-frequency stimulation (spike/s); Mps - post-stimulus average spike frequency (spike/s). A decrease in pre- and post-stimulus neuronal spike frequency from the 1-2th minute of Teucrium administration compared with the initial spike activity (marked by 0 min before Teucrium injection) is obvious. From the 60th minute, the spiking activity was restored. Thus, inhibitory effects were detected in a single NBM neuron following a single injection of a therapeutic dose of Teucrium polium

The percentage share of excitatory and inhibitory responses of amygdala and hippocampal neurons to NBM HFS

In the amyloid group, a total of 69 basolateral amygdala cells were examined. Among these cells, 29% (20 neurons) displayed transient depolarization (TD), 39.1% (27 neurons) exhibited TD-PTD responses, 21.8% (15 neurons) exhibited TD-PTP responses, and 10.1% (7 neurons) exhibited TP-PTP responses (Fig. 1B). A comparison between the amyloid group and the vehicle control group (77 neurons) (Fig. 1A, B) revealed a significant decrease in the proportion of neurons with TP-PTP responses in the amyloid group (10.1% vs. 27.3% in the vehicle control group; p < 0.04, Fisher’s exact test). The proportion of neurons with TD-PTD responses was highest in both groups (39% vs. 37% in the vehicle control group; p < 0.9, Fisher’s exact test), with these neurons showing the least imbalance. Conversely, the proportion of neurons with TP-PTP responses demonstrated the greatest imbalance (10% vs. 27% in the vehicle control group; p < 0.04, Fisher’s exact test). In the amyloid + Teucrium group, a total of 55 amygdala neurons were studied. Among these neurons, 31% (17 neurons) displayed TP-PTP responses to NBM high-frequency stimulation (HFS) (compared to 27% in the vehicle control group; p = 0.8, Fisher’s test), while 25.5% (14 neurons) exhibited TD-PTD responses and 16.4% (9 neurons) exhibited TD-PTP responses (compared to 27% in the vehicle control group; p = 0.3, Fisher’s test) (Fig. 1C). Notably, TP-PTP responses were recorded in 15 neuronal units out of 55 (27.3%, p < 0.0001 vs. control), and these responses were absent in both the vehicle control and amyloid groups (Fig. 1A-C). Thus, the percentage of TP neurons in the norm group was 27%, consisting of TP-PTP neurons. In the amyloid + Teucrium group, this percentage increased to 58%, comprising TP-PTP and TP-PTD neurons, which was statistically significant (P = 0.02, Fisher’s exact test). The percentage of TD neurons in the norm group was 64%, consisting of TD-PTD and TD-PTP neurons. In the amyloid + Teucrium group, the percentage of TD neurons decreased to 42%, comprising TD-PTD and TD-PTP neurons, although this decrease was not statistically significant (P = 0.2, Fisher’s exact test). In the amyloid group, 205 responses of hippocampal neurons to NBM GFS were examined. Of these, 13.7% (28 neurons) showed no response, 31.2% (n = 64) showed TD-PTD responses, 28.8% (n = 59) showed TD-PTP responses, and 26.3% (n = 54) showed TP-PTP responses. The percentage of TD neurons was lower in the amyloid group (60%) compared to the control group (67%; P = 0.5, NS). Conversely, the percentage of TP neurons was higher in the amyloid group (26.3%) than in the control group (23%; P = 0.6, NS). When comparing these indices in the amyloid group to those in the vehicle control group (Fig. 2A, B), it was revealed that: (1) The maximal share of units with TD-PTD responses was 31.2% (compared to 41.8% in the vehicle control group; P = 0.1), and (2) The minimal imbalance in the percentage share of neurons with TD-PTP responses was 28.8% (compared to 24.9% in the vehicle control group; P = 0.5; Fisher’s exact test) (Fig. 2A, B). In the amyloid + Teucrium group, 135 hippocampal neurons were studied. Of these, 2.2% (3 neurons) showed no reactivity (p = 0.07, Fisher; non-significant increase compared to control), 56.3% showed TD-PTD responses (p = 0.1, Fisher; non-significant increase compared to control), and 20.7% showed TD-PTP responses (p = 0.5, Fisher; non-significant decrease compared to control). Only TP responses were recorded in 28 units (21%) of the 135 hippocampal neurons (Fig. 2C). In summary, the percentage of TP neurons in the normal group was 23% (these were TP-PTP neurons). In the amyloid + Teucrium group, the percentage of TP neurons decreased to 21% (these were TP neurons), although this decrease was not significant (P = 0.7; Fisher test). In the norm group, the percentage of TD neurons was 77% (these comprised TD-PTD, TD-PTP, and TD neurons). The percentage of TD neurons remained at 77% in the amyloid + Teucrium group (comprising 56% TD-PTD neurons and 21% TP neurons). The analysis of the percentage share of excitatory and inhibitory responses showed that: (1) In the Vehicle + Teucrium group, the percentage of amygdala neurons with TP-PTP responses increased compared to the Vehicle-control group (51.2% vs. 27.3%; P = 0.1; NS increase, Fisher test), and (2) The percentage of neurons displaying TD-PTD responses decreased nonsignificantly (21% vs. 37%; P = 0.2; NS Fisher test). Overall, a significant increase in tetanic potentiation (72.2%; 51.2% + 21% TP-PTP and TP-PTD vs. 27.3% in Vehicle-control; p = 0.004) and a significant decrease in tetanic depression (28%; 7% + 21% vs. 72.8%; 9.1% + 36.4% + 27.3% in Vehicle-control; p = 0.01) were recorded during HFS of NBM in amygdala neurons (Fig. 1A). In hippocampal neurons, the excitation/depression balance was as follows: (1) The percentage of TD-PTD responses increased nonsignificantly in the Vehicle + Teucrium group (Fig. 3) compared to the Vehicle-control group (55% vs. 42%; P = 0.4), predominating in both groups, and (2) The percentage of TP-PTP responses decreased nonsignificantly in the Vehicle + Teucrium group (Fig. 3A) compared to the Vehicle-control group (10.4% vs. 23.3%; P = 0.1, Fisher test). In the hippocampal neurons of the Vehicle + Teucrium group, tetanization epoch depression (TD) was recorded in a total of 80% (25% + 55%) neurons (nonsignificant increase vs. control, P = 0.5, Fisher), while tetanization epoch potentiation (TP) decreased nonsignificantly (10.4%; P = 0.1; Fig. 3B). In the Vehicle-control group, this ratio was 66.7% (24.9% + 41.8%) and 23.3%, respectively (Fig. 2A).

Assessment of the magnitude of excitatory and inhibitory responses of amygdala and hippocampal neurons to NBM HFS

The expression of inhibitory (TD) and excitatory (TP) responses during the high-frequency stimulation (HFS) epoch, as well as the post-stimulus time (PTD and PTP), was altered across all experimental groups compared to the vehicle-control group, with specific response types observed in each population. In the vehicle-control group, TD was expressed 4.7 times (2.61:0.56 spike/sec), whereas it was expressed 2.4 times (3.25:1.36 spike/sec) in basolateral amygdala neurons with TD-PTD responses (Fig. 1). Similarly, in neurons exhibiting TD-PTP responses, TD was expressed 5.7 times (1.83:0.32 spike/sec) instead of 2.3 times (2.44:1.07 spike/sec) in the amyloid group. In TP-PTP neurons, TP was expressed 5 times (13.23:2.66 spike/sec) instead of 1.9 times in the amyloid group. In the amyloid + Teucrium polium group, the expression of responses predominated compared to the amyloid group in populations with TP-PTP responses (7.6 times; 10.52:1.38 spike/sec) and TD-PTP responses (22.6 times; 5.64:0.25 spike/sec), as well as in populations with TP-PTD responses (4.5 times; 19.48:4.34 spike/sec). In the amyloid + Teucrium polium group, TD was expressed 1.8 times in neurons displaying TD-PTD responses (5.75:3.25 spike/sec), which was lower than that observed in the vehicle-control (4.7-fold) and amyloid (2.4-fold) groups (Fig. 1). Regarding the expression of responses during the tetanization period, both excitatory and inhibitory responses were more pronounced in the hippocampal vehicle-control group. In neurons with TD-PTD responses, TD was expressed 2.4 times (7.13:2.93 spike/sec) in the vehicle-control group compared to 1.4 times (9.29:6.53 spike/sec) in the amyloid group. Similarly, in neurons with TD-PTP responses, TD was expressed 2.3 times (5.78:2.55 spike/sec) in the vehicle-control group compared to 1.4 times (4.45:3.18 spike/sec) in the amyloid group (Fig. 2). In TP-PTP neurons, TP was expressed 1.7 times (9.12:5.22 spike/sec) in the vehicle-control group compared to 1.3 times (16.87:12.83 spike/sec) in the amyloid group. In the amyloid + Teucrium polium group, TD was expressed 9.6 times (17.91:1.86 spike/sec) in neurons with TD-PTD responses compared to 2.4 times in the vehicle-control group. In neurons with TD-PTP responses, TD was expressed 20 times (8.11:0.4 spike/sec) compared to 2.3 times in the vehicle-control group (Fig. 2B). TP responses in the amyloid + Teucrium polium group were expressed 2 times (17.10:8.30 spike/sec) compared to 1.7 times in the vehicle-control group (Fig. 2).

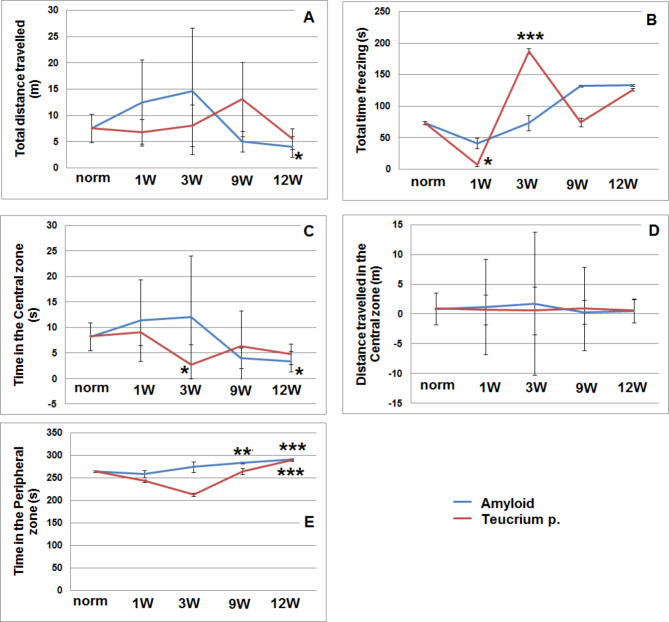

The effects of amyloid and Teucrium polium on behavior

Open field results indicated that amyloid-injected rats exhibited significantly reduced locomotor activity, traveling less distance at 12 weeks (P = 0.04), suggesting that these rats were less active and more hesitant to explore the open-field arena (Fig. 5A). Additionally, this group spent more time freezing at weeks 9 and 12 (Fig. 5B), indicating heightened anxiety and discomfort in the arena. In contrast, rats treated with Teucrium polium spent significantly more time freezing at 3 weeks (P = 0.002) (Fig. 5B), suggesting a short-term anxiolytic effect; however, no significant differences were observed between the two groups at 9 or 12 weeks, indicating that this effect may not be sustained over time. Rats in the amyloid group also spent significantly less time in the central zone after 12 weeks (P = 0.03) (Fig. 5C), reflecting avoidance of this area, which is typically the most explored in the open field. Rats treated with Teucrium spent significantly more time in the central zone compared to control rats at 3 weeks (P = 0.02) (Fig. 5C), but this effect diminished by 9 and 12 weeks. This suggests that Teucrium may have a short-term impact on increasing exploration. The results showed that the time spent in the peripheral zone for the control group was 264 ± 9.6 s (Fig. 5D). In contrast, the amyloid group spent significantly less time in the peripheral zone at 12 weeks (91 ± 5.5 s, P = 0.0006) (Fig. 5D), indicating increased anxiety and reduced exploratory behavior. Similarly, the Teucrium-treated rats showed signs of increased anxiety at 12 weeks, though this effect was not statistically significant (Fig. 5D, E). Overall, these findings suggest that Teucrium polium may exhibit short-term anxiolytic properties, improving exploratory behavior initially but lacking sustained effects over time.

Fig. 5.

Open-field test scores in the Amyloid and Amyloid + Teucrium groups at 1, 3, 9, and 12 weeks. A: Total distance traveled (m); B: Total time freezing (s); C: Time in the central zone (s); D: Distance traveled in the central zone (m); E: Time in the peripheral zone (s). The calculations were performed using Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software). P values were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. * indicates significantly different from the group vehicle control (*p < 0.05), ******p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001)

Discussion

The basal forebrain cholinergic system is pivotal for cognitive function, particularly the NBM, which is essential for memory consolidation [51, 52]. This relationship may stem from the dense cholinergic innervation present in key areas such as the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and amygdala [53–55]. The nucleus basalis of Meynert (NBM) projects cholinergic fibers to the lateral and basolateral amygdaloid nuclei [56] and is positioned to rapidly convey value-based information to target regions [57]. These findings suggest a significant influence of the NBM on the basolateral amygdala in the development of contextual memory [58]. The NBM is a complex and heterogeneous structure primarily composed of cholinergic neurons, with at least 20–30% being noncholinergic (including GABAergic, glutamatergic, and peptidergic neurons) [59]. In vivo studies have shown that lesions in this cholinergic nucleus disrupt both short- and long-term neural plasticity in the dentate gyrus, despite the absence of direct cholinergic projections to the hippocampus [60]. Basal forebrain neurons in rats play crucial roles in activating the entorhinal cortex and memory processes, which are linked to cholinergic neurons projecting to this area. Evidence indicates that these neurons synthesize glutamate, acetylcholine, GABA, and other neurotransmitters [61]. Our findings of less pronounced responses in the hippocampus during high-frequency stimulation of the NBM may result from the lack of direct projections to the hippocampus, implicating NBM-entorhinal cortex-hippocampus pathways. Our results align with existing literature indicating that Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by a significant loss of cholinergic innervation, particularly in the entorhinal cortex, where cholinergic axons can be depleted by up to 80%. This depletion closely correlates with severe neurofibrillary degeneration and cell loss in the nucleus basalis complex [62]. Amyloid-beta (Aβ) can disrupt cellular homeostasis and neural network communication by modulating ion channels in cholinergic basal forebrain neurons [63]. Specifically, Aβ increases Ca²⁺ influx through voltage-sensitive L-type Ca²⁺ channels [64], leading to bursts of excitatory potentials and heightened action potential firing in neurons. This abnormal neuronal activity can disrupt communication within neuronal networks, as evidenced by our recorded neurons. A potential mechanism for this hyperexcitability is the increase in calcium conductance. Moreover, recent studies indicate that amyloid proteins can interact with cholinergic receptors, leading to alterations in their function [65]. Key abnormalities in cholinergic neurons include impaired choline absorption, reduced acetylcholine release, defective expression of nicotinic and muscarinic receptors, and deficits in neurotrophic support and axonal transport [66]. These phenomena were also reflected in the network activity observed in our investigation. Consequently, we observed electrophysiological indices of abnormal synaptic activity within the basal nucleus-hippocampus-amygdala network in our experimental AD model, which was induced by bilateral intracerebroventricular administration of Aβ (25–35). Aβ may impair neural network function by affecting both intrinsic and synaptic properties of neuronal circuits [67, 68]. The mechanisms behind Aβ’s electrophysiological effects on synaptic transmission and neuronal firing properties have been extensively reviewed by Peña et al. [64]. Evidence suggests that both soluble monomer and oligomer forms of Aβ can impact neuronal activity and remodeling even before the onset of neurodegeneration. Protofibrils, which are transitional states between soluble and aggregated Aβ, pose threats to primary neuronal cells by altering their electrical properties. Recent findings highlight that dendritic arbors are particularly susceptible to the effects of Aβ oligomers. Aβ oligomers derived from the brains of individuals with AD or produced in laboratories have been shown to bind to neuronal surfaces, forming small clusters primarily associated with specific synaptic terminals in cultured hippocampal neurons. In culture models, Aβ oligomers have also been found to disrupt other synaptic signal transduction pathways. Low doses of Aβ oligomers can inhibit glutamate-stimulated phosphorylation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) in cortical cultures [69], a signaling pathway linked to synaptic plasticity [70]. Thus, the role of Aβ oligomers as pathogenic synaptic ligands presents an intriguing hypothesis for synapse failure in AD. Aβ-induced cationic channels [71], impairments in basal synaptic transmission [72], and reductions in long-term potentiation (LTP) [73] are CNS-specific markers of both acute and chronic Aβ exposure. Accumulating evidence suggests that Aβ acts as a synaptic disruptor, with synapses potentially serving as therapeutic targets in AD [64]. The dynamic nature of synaptic transmission is influenced by presynaptic activity, which in turn affects postsynaptic reactions. Chemical synaptic transmission is crucial for shaping synaptic response properties, influencing the stimuli that neural networks prioritize and the activity patterns they generate. The observed deficiency in TP/TD responses in the amyloid group likely resulted from synaptic vesicle depletion and impaired neurotransmitter release. It is well documented that synaptic depression is often linked to the depletion of readily releasable vesicles, with various conceptual models describing this phenomenon. Depression can also arise from presynaptic receptor feedback activation and postsynaptic mechanisms, such as receptor desensitization [74]. Our acute experiments demonstrated a temporary (60-minute) deactivation of spike activity, presumably due to the desensitization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs). The decrease in the equity ratio and the notable excitatory responses in the amyloid group align with findings from Snyder et al. (2005), who reported that amyloid-beta disrupts glutamatergic transmission and impairs synaptic plasticity [75]. Given the significant interaction between cholinergic and glutamatergic systems during neurotransmission, changes in glutamatergic signaling correlate with cholinergic disruptions seen in AD, supporting the cholinergic hypothesis [76, 77]. Numerous studies have identified nAChRs as presynaptic, preterminal receptors that interact with other metabolic or ionotropic receptors [76, 78]. They also modulate the release of various neurotransmitters, including glutamate, GABA, dopamine, noradrenaline, and glycine, through presynaptic action sites. This neurotransmitter release is likely essential for mediating the cognitive-enhancing effects of Teucrium polium. The distinct distribution of nAChR subtypes and the timing of nAChR activity can influence the induction of synaptic plasticity, either favorably or unfavorably [79]. nAChRs operate within heteromers (receptor-receptor interactions) and as components of functional interactive proteins (receptor crosstalk) that respond to integrative inputs [76]. Understanding the mechanisms of heteromodulation, including G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) heterodimerization with nAChRs and receptor crosstalk, is vital for addressing cognitive decline. In our acute experiments with a single therapeutic dose of Teucrium polium, the transient deactivation of spike activity in single NBM neurons appears to result from both receptor-receptor interactions and receptor crosstalk. Interestingly, Kawamata et al. demonstrated that neuroprotection against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity occurs via nAChR-mediated survival signal transduction, specifically through the α7nAChR/Src family/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) pathway, leading to upregulation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-x [80]. Presynaptic nAChRs can enhance neurotransmitter release probability, thereby improving synaptic transmission precision. Postsynaptic nAChRs increase depolarization and calcium signaling associated with successful transmission, activating intracellular cascades. Additionally, nicotinic activity can significantly influence interneuron activity by modulating circuit excitability. Nicotinic activity in interneurons can inhibit neighboring pyramidal neurons, which may reduce or prevent the induction of synaptic potentiation. This could explain the more pronounced inhibitory effects observed in hippocampal neurons of the amyloid + Teucrium polium group (9.6 times and 20 times instead of 2.4-fold in the vehicle-control group), likely due to the tighter localization of acetylcholine receptors on GABAergic interneurons compared to glutamatergic pyramidal neurons [79]. This dynamic may contribute to the final excitatory-inhibitory effects of cholinergic input on the neuronal activity of the circuits we studied (evoked activity of hippocampal neurons to high-frequency stimulation of the NBM). Furthermore, we concur that synaptic damage from soluble Aβ-derived oligomers appears to underlie memory loss in early AD, as these oligomers bind to specific excitatory pyramidal neurons while sparing GABAergic neurons [81]. The NBM provides cholinergic input to the cerebral cortex and amygdala, with cholinergic neurons constituting about 90% of NBM neurons [82].

Unlike primates, the rat cerebral cortex includes intrinsic cholinergic interneurons, contributing approximately 30% of local cholinergic innervation [83]. These factors are crucial in the development of overall network activity. Our findings regarding the distinct effects of increases or decreases in excitatory and inhibitory responses in the hippocampus and basolateral amygdala align with the notion that the net effect of amyloid-beta (Aβ) on specific neuronal subtypes, brain regions, and networks can be excitatory, inhibitory, or a combination of both. According to Palop et al. (2007), hAPP animals exhibit spontaneous nonconvulsive seizure activity in cortical and hippocampal networks, which is associated with GABAergic sprouting, increased synaptic inhibition, and abnormalities in dentate gyrus synaptic plasticity [84]. The study revealed that administering Teucrium polium extract led to significant improvements in learning and memory in rats. In the anticholinesterase assay, the extract demonstrated potent inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity. Alpha-pinene, a major component contributing to Teucrium polium’s anticholinesterase properties, has been extensively studied for its strong anti-acetylcholinesterase effects [28]. Furthermore, research by Vladimir-Kneevi’c et al. on the ethanol extract of several Lamiaceae species showed that T. polium was among the most effective plant extracts, exhibiting significant acetylcholinesterase inhibition rates exceeding 75% at a concentration of 1 mg/mL [85]. Given that central cholinergic pathways are crucial for learning and memory processes, the anticholinesterase activities of Teucrium polium may contribute to its nootropic effects [86]. Additionally, diterpenes and flavonoids present in Teucrium polium could enhance memory [87]. In amyloid-beta-injected rats, dietary supplementation with plants from the Lamiaceae family mitigated memory loss, altered CREB (calcium/cAMP-response element-binding protein) and its downstream components, and reduced apoptosis. Phenylpropanoid glycosides, naturally occurring compounds in various medicinal plants, exhibit diverse biological activities, including potent antioxidant properties. Among these, acteoside, a phenylethanoid glycoside with antioxidant effects, has been shown to protect human neuroblastoma cells from amyloid-induced cell damage by reducing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and modulating apoptotic signaling pathways through interactions with the Bcl-2 family, cytochrome c, and caspase-3 [88]. The structure-activity relationship for acteoside and similar compounds suggests that the catechol moiety of phenylethanoid glycosides is essential for this inhibitory activity. In amyloidogenic modification, such a covalent β-sheet structure may destabilize polypeptides [89]. Increasing evidence indicates that phenylpropanoid glycosides possess potent antioxidant properties, acting as direct scavengers of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species or peroxyl radical scavengers that interrupt chain reactions. Korkina et al. conducted a study on the phenylpropanoid glycoside teupolioside, revealing its substantial anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and metal-chelating capabilities, particularly with bivalent metals such as Fe2+ [90]. Moreover, aqueous extracts of Teucrium polium have demonstrated high antioxidant activity [91] and have significantly reduced lipid peroxidation in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex [92]. High doses of the extract also enhanced total thiol concentrations in hippocampal tissues. Teucrium polium has been shown to drastically reduce lipid peroxidation in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex, suggesting that oxidative stress protection likely contributes to the extract’s learning and memory-boosting abilities. Furthermore, plant phenylpropanoid glycosides target brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) regulation, presenting a potential therapeutic approach for treating depression. The neuroplasticity-enhancing effects of phenylpropanoid glycosides are mediated through BDNF upregulation, activation of downstream BDNF signaling pathways, and increased neurogenesis in the hippocampus and/or prefrontal cortex (PFC) [93]. Despite the positive effects of Teucrium polium discussed in this study, it is important to note that the plant has also been documented to have hepatotoxic and nephrotoxic effects [94]. Our earlier findings indicate that the ethanol extract and ethyl acetate fraction of hydroponic Teucrium polium are hepatotoxic at the maximum tolerable dose [95]. However, the maximal tolerable dose of the aqueous fraction of the ethanol extract, devoid of furolactone acids, revealed no hepatotoxicity, implying that the hepatotoxicity of Teucrium polium is conditioned by furolactone acids. After 20 days of treatment with a therapeutic dose of the ethanol extract, women’s ALT, AST ratio, and De Ritis Ratio were all within normal limits [95]. Synaptic plasticity, characterized by sustained activity-dependent increases or decreases in synaptic strength, provides the neurophysiological basis for hippocampal-dependent learning and memory. Acute treatment with human-derived or chemically produced soluble Aβ containing specific oligomeric assemblies potently and selectively alters synaptic plasticity, resulting in the suppression of long-term potentiation (LTP) and the augmentation of long-term depression (LTD) of glutamatergic transmission. Over time, these and related Aβ activities have been linked to decreased synaptic integrity [96]. The exceptionally high efficacy of Aβ oligomers in altering synaptic plasticity has prompted significant research into the underlying biological mechanisms [64, 97]. Styr and Slutsky examined various potential homeostatic failures, providing the conceptual framework necessary for investigating the causal link between dysregulation of firing homeostasis, aberrant neural circuit activity, and memory-related plasticity impairments associated with early Alzheimer’s disease [98]. Advances in understanding the various pathways contributing to short-term synaptic plasticity are anticipated in the coming years. Despite its frequency, short-term presynaptic depression remains one of the least understood forms of plasticity. While more is known about the mechanisms underlying facilitation and post-tetanic potentiation, a more comprehensive understanding awaits the identification of the proteins responsible for these types of synaptic enhancement. Short-term plasticity (STP) refers to changes in synaptic responses to past activation that persist for only a few minutes. Short-term depression indicates a decrease in the efficacy of synaptic transmission following the arrival of a spike, while short-term facilitation represents an increase in efficacy [99]. In STP, a synapse’s effectiveness typically recovers within hundreds of milliseconds. The computational role of STP in learning and memory is considerably less developed than that of long-term potentiation (LTP). Data from cortical neurons suggest that changes in total network activity rescale synapses in a multiplicative or fractional manner [100]. Such systems enable cells to regulate inhibition and excitation, preventing pathological states of network hyper- or hypo-excitability. Another approach to addressing the stability of plasticity involves ensuring the permanence of brain computations in a network through multistable synapses, where each synapse has a cascade of states with varying degrees of plasticity [101]. Our data indicate that amyloid-treated rats exhibited increased anxiety-like behavior in the open-field test. These rats traveled a shorter distance, spent more time freezing, and spent less time in the central zone compared to control rats. The reduced distance traveled and decreased time spent in the central zone by the amyloid-treated rats may suggest a decreased willingness to explore their environment, which could adversely affect their capacity for active learning. Additionally, increased freezing behavior may reflect a heightened fear response, potentially interfering with the encoding and consolidation of memories. Amyloid-treated rats also spent more time freezing than the norm group. However, Teucrium treatment at 1 week resulted in a significant decrease in freezing time compared to the norm group. In terms of time spent in the central zone, amyloid-treated rats at 12 weeks showed significantly shorter durations compared to the norm group. Teucrium-treated rats at 3 weeks spent significantly less time in the peripheral zone compared to the norm group. Freezing time serves as an indicator of anxiety-related behavior in rats [102], and these results suggest that Teucrium treatment may have mitigated the anxiety-related behaviors in these animals. Nonetheless, Teucrium-treated rats also displayed anxiety-like behaviors in the open-field test. The anxiolytic effects of Teucrium may be attributed to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [12]. Reduced anxiety levels could positively influence memory and learning processes, as lower anxiety can enhance attentional resources, promote cognitive flexibility, and facilitate the encoding and retrieval of information [103]. Furthermore, acetylcholine (ACh) can enhance attentional and memory functions, as well as increase synaptic plasticity by coordinating activity across brain networks [104]. Both the amygdala and central cholinergic systems are essential for effective learning and memory [105]. In mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease (AD), reductions in cholinergic cell populations within the amygdala can lead to impairments in emotional memory [106].

Limitations

One of the primary limitations of this study is the relatively small sample size, which may impact the robustness of our findings. Although we believe this sample size was adequate to observe significant changes in key parameters, increasing the sample size in future studies could strengthen the reliability and generalizability of the results. Larger cohorts would provide a more comprehensive evaluation of the effects of Teucrium polium on synaptic plasticity, particularly within the context of Alzheimer’s disease. Future investigations should therefore include a broader sample to confirm these preliminary findings and to further clarify Teucrium polium’s potential therapeutic role.

Conclusion

The central cholinergic system is pivotal for cognitive functions and currently serves as a target for AChE inhibitors in the treatment of AD-like dementia. Natural sources and isolated bioactive compounds present promising avenues for developing effective medications. Plants from the Lamiaceae family have been reported to possess AChE inhibitory properties. Our research enhances the understanding of Teucrium polium, a member of the Lamiaceae family, highlighting its potential to enhance synaptic plasticity within the cholinergic network disrupted by amyloid-beta in AD. Given their capacity to promote neuroplasticity, these compounds are considered promising candidates for clinical trials in AD. Once their effectiveness, tolerability, and safety are established, they could serve as natural alternatives to conventional AChE inhibitors.

Thus, Teucrium polium emerges as a promising candidate for treating various health-debilitating conditions, holding significant potential in both the pharmaceutical sector and medical research.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: V.C., L.D, K.S. Acquisition of data: V.C., K.S., L.D., L.H. and L.M. Analysis and interpretation of the data: V.C., K.S., L.D. Drafting of the manuscript: K.S. and V.C. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Faculty Research Funding Program, 2022, Enterprise Incubator Foundation, Armenia.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal procedures were performed under the supervision of the institutional ethics committee of Yerevan State Medical University after Mkhitar Heratsi, Yerevan, Armenia (approved code: N4 IRB). The ARRIVE guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were also followed.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

There are no actual or potential competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wilson DM 3rd, Cookson MR, Van Den Bosch L, Zetterberg H, Holtzman DM, Dewachter I. Hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases. Cell. 2023 Feb 16;186(4):693–714. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Taylor HB, Jeans AF. Friend or foe? The varied faces of homeostatic synaptic plasticity in neurodegenerative disease. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021;15:782768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis GW. Homeostatic signaling and the stabilization of neural function. Neuron. 2013;80:718–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbott LF, Regehr WG. Synaptic computation. Nature. 2004;431(7010):796–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tong R, Emptage NJ, Padamsey Z. A two-compartment model of synaptic computation and plasticity. Mol Brain. 2020;13:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goel P, Nishimura S, Chetlapalli K, Li X, Chen C, Dickman D. Distinct target-specific mechanisms homeostatically stabilize transmission at pre- and post-synaptic compartments. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kavalali ET et al. Targeting homeostatic synaptic plasticity for treatment of Mood disorders. Neuron 2020 Jun 3;106(5):715–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Maher PA. Using plants as a source of potential therapeutics for the treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Yale J Biol Med. 2020;93(2):365–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi J, Ni J, Lu T, Zhang X, Wei M, Li T, Liu W, Wang Y, Shi Y, Tian J. Adding Chinese herbal medicine to conventional therapy brings cognitive benefits to patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a retrospective analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams P, Sorribas A, Howes MJ. Natural products as a source of Alzheimer’s drug leads. Nat Prod Rep. 2011;28(1):48–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuzimski T, Petruczynik A. Determination of Anti-alzheimer’s Disease activity of selected plant ingredients. Molecules. 2022;27(10):3222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benchikha N, Messaoudi M, Larkem I, Ouakouak H, Rebiai A, Boubekeur S, Ferhat MA, Benarfa A, Begaa S, Benmohamed M, et al. Evaluation of possible Antioxidant, Anti-Hyperglycaemic, Anti-alzheimer and Anti-inflammatory effects of Teucrium Polium Aerial Parts (Lamiaceae). Life. 2022;12(10):1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suganthy N, Pandian SK, Devi KP. Cholinesterase inhibitors from plants: possible treatment strategy for neurological disorders–a review. Int J Biomed Pharm Sci. 2009;3:87–103. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wevers A, Burghaus L, Moser N, et al. Expression of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: Postmortem investigations and experimental approaches. Behav Brain Res. 2000;113:207–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schliebs R, Arendt T. The significance of the cholinergic system in the brain during aging and in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm. 2006;113:1625–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geula C, Nagykery N, Nicholas A, Wu CK. Cholinergic neuronal and axonal abnormalities are present early in aging and in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:309–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Francis PT, Palmer AM, Snape M, Wilcock GK. The cholinergic hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: a review of progress. J NeurolNeurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66(2):137–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kadir A, Almkvist O, Wall A, Langstrom B, Nordberg A. PET imaging of cortical 11 C-nicotine binding correlates with the cognitive function of attention in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychopharmacology. 2006;188:509–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parri RH, Dineley TK. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor interaction with beta-amyloid: molecular, cellular, and physiological consequences. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:27–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grossberg GT. Cholinesterase inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease:: getting on and staying on. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2003;64(4):216–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marucci G, Buccioni M, Ben DD, Lambertucci C, Volpini R, Amenta F. Efficacy of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology. 2021;190:108352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darvesh S, Walsh R, Kumar R, et al. Inhibition of human cholinesterases by drugs used to treat Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis AssocDisord. 2003;17(2):117–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perry EK, Perry RH, Blessed G, Tomlinson BE. Changes in brain cholinesterases in senile dementia of Alzheimer type. NeuropatholApplNeurobiol. 1978;4:273–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mesulam MM. Butyrylcholinesterase in the normal and Alzheimer brain. In: Giacobini E, editor. Butyrylcholiesterase: its function and inhibitors. London: Martin Dunitz; 2003. pp. 31–4. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khoury R, Patel K, Gold J, Hinds S, Grossberg GT. Recent progress in the Pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer’s Disease. Drugs Aging. 2017;34(11):811–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perry N, Court G, Bidet N, et al. Cholinergic activities of European herbs and potential for dementia therapy. J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1996;11:1063–69. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howes MJR, Perry NSL, Houghton PJ. Plants with traditional uses and activities relevant to the management of Alzheimer’s disease and other cognitive disorders. Phytother Res. 2003;17:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orhan I, Aslan M. Appraisal of scopolamine-induced antiamnesic effect in mice and in vitro antiacetylcholinesterase and antioxidant activities of some traditionally used Lamiaceae plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;122:327–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasani-Ranjbar S, Nayebi N, Larijani B, et al. A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of Teucrium species; from anti-oxidant to antidiabetic effects. Int J Pharmacol. 2010;6:315–25. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bahramikia S, Yazdanparast R. Phytochemistry and Medicinal properties of Teucrium Polium L. (Lamiaceae). Phytother Res. 2012;26(11):1581–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Topcu G, Kusman T. Lamiaceae Family Plants as a potential anticholinesterase source in the treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Bezmialem Sci. 2014;1:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orhan I, Kartal M, Naz Q, Ejaz A, Yilmaz G, Kan Y, KonuklugilB, Choudhary MI. Antioxidant and anticholinesterase evaluation of selected Turkish Salvia species. Food Chem. 2007;103:1247–12254. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adewusi EA, Moodley N, Steenkamp V. Medicinal plants with cholinesterase inhibitory activity: a review. Afr J Biotechnol. 2010;9(49):8257–76. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oganesyan GB, Galstyan AM, Mnatsakanyan VA, Shashkov AS, Agababyan PV. Phenylpropanoid glycosides of Teucrium Polium. Chem Nat Compd. 1991;27:556–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galstyan HM, Shashkov AS, et al. Structure of two new deterpenoids of Teucrium polium L. Chem Nat Compd. 1992;2:223–30. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galstyan HM. Standardization of Teucrium Polium L. by natural phytoestrogens- phenylpropanoid glycosids and flavonoids. NAMJ. 2014;8(2):53–8. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amen Y, Elsbaey M, Othman A, Sallam M, Shimizu K. Naturally occurring Chromone glycosides: sources, bioactivities, and Spectroscopic features. Molecules. 2021;26(24):7646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simonyan KV, Chavushyan V. A.Protective effects of hydroponic Teucrium polium on hippocampal neurodegeneration in ovariectomized rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16(1):415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tadevosyan NE, Tumanyan GHM, Forgan AA. B. B. Dynamics of cognitive processes in middle age women under administration of fraction of hydroponic Teucrium poliumLamiaceae. Russian Journal of Physiology. 2017, V. 103. N 9. P. 1069–1076.

- 40.Savioz A, Leuba G, Vallet PG, Walzer C. Contribution of neural networks to Alzheimer disease’s progression. Brain Res Bull. 2009;80(4–5):309–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Small DH. Network dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: does synaptic scaling drive disease progression? Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chavushyan V, Soghomonyan A, Karapetyan G, Simonyan K, Yenkoyan K. Disruption of Cholinergic circuits as an area for targeted drug treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: in vivo Assessment of short-term plasticity in rat brain. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2020;13(10):297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2010;1(2):94–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chavushyan V, Simonyan K, Galstyan H. Toxicity studies of Teucrium poliumlamiaceae growing in nature and in culture. The Second International symposium Biopharma 2010: from science to industry May 17–20 Armenia. Yerevan: 2010. p. 11, 45.

- 45.Galstyan HM, Revazova LV, Topchyan HV. Digital indices and microscopic analyses of wild growing and overgrowing of Teucrium Polium L. in hidroponic conditions. New Armen Med J. 2010;4(3):104. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maurice T, Privat A. Sigma1 (sigma 1) receptor agonists and neurosteroids attenuate beta25–35-amyloid peptide-induced amnesia in mice through a common mechanism. Neuroscience. 1998;83:413–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. // 5th Edition. New York: Academic Press. 2005; P.367.

- 48.Simonyan K, Avetisyan L, Isoyan A, Chavushyan V. Plasticity in Motoneurons Following Spinal Cord Injury in Fructose-induced Diabetic rats. J MolNeurosci. 2022;72(4):888–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakagawa H, Matsunaga D, Ishiwata T. Effect of heat acclimation on anxiety-like behavior of rats in an open field. J Therm Biol. 2020;87:102458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ballinger EC, Ananth M, Talmage DA, Role LW. Basal Forebrain Cholinergic Circuits and Signaling in Cognition and Cognitive Decline. Neuron. 2016;91(6):1199–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Lee JE, Jeong DU, Lee J, Chang WS, Chang JW. The effect of nucleus basalis magnocellularis deep brain stimulation on memory function in a rat model of dementia. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Prut L, Belzung C. The open field as a paradigm to measure the effects of drugs on anxiety-like behaviors: a review. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;463(1–3):3–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mesulam MM, Hersh LB, Mash DC, Geula C. Differential cholinergic innervation within functional subdivisions of the human cerebral cortex: a choline acetyltransferase study. J Comp Neurol. 1992;318(3):316–28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Botly LCP, Baxter MG, De Rosa E. Basal Forebrain and Memory., in Encyclopedia of Neuroscience, 2009.

- 55.Mesulam M. The cholinergic lesion of Alzheimer’s disease: pivotal factor or side show? Learn Mem. 2004 Jan-Feb;11(1):43 – 9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Woolf NJ. Butcher LL Cholinergic projections to the basolateral amygdala: a combined Evans Blue and acetylcholinesterase analysis. Brain Res Bull. 1982;8(6):751–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hangya B, Ranade SP, Lorenc M, Kepecs A. Central cholinergic neurons are rapidly recruited by reinforcement feedback. Cell. 2015;162:1155–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baldi E, Mariottini C, Bucherelli C. The role of the nucleus basalis magnocellularis in fear conditioning consolidation in the rat. Learn Mem. 2007;14(12):855–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vale-Martínez A, Guillazo-Blanch G, Martí-Nicolovius M, Nadal R, Arévalo-García R, Morgado-Bernal I. Electrolytic and ibotenic acid lesions of the nucleus basalis magnocellularis interrupt long-term retention, but not acquisition of two-way active avoidance, in rats. Exp Brain Res. 2002;142(1):52–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hosseini N, Alaei H, Reisi P, Radahmadi M. The effects of NBM- lesion on synaptic plasticity in rats. Brain Res. 2017;1655:122–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Manns ID, Mainville L, Jones BE. Evidence for glutamate, in addition to acetylcholine and GABA, neurotransmitter synthesis in basal forebrain neurons projecting to the entorhinal cortex. Neuroscience. 2001;107(2):249–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Geula C, Mesulam MM. Cholinergic systems in Alzheimer’s disease. In: Terry RD, et al. editors. Alzheimer disease. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1999. pp. 69–292. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jhamandas JH, Cho C, Jassar B, Harris K, MacTavish D, Easaw J. Cellular mechanisms for amyloid –protein activation of rat cholinergic basal forebrain neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:1312–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peña F, Gutiérrez-Lerma AI, Quiroz-Baez R, Arias C/. / The role of β-Amyloid protein in synaptic function: implications for Alzheimer’s Disease Therapy.// CurrNeuropharmacol. 2006; 4(2): 149–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Ni R, Marutle A, Nordberg A. Modulation of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and fibrillar amyloid-β interactions in Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33:841–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shen J, Wu J. Nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2015;124:275–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ramirez JM, Tryba AK, Pena F. Pacemaker neurons and neuronal networks: an integrative view. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:665–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Colom-Cadena M, Davies C, Sirisi S, Lee JE, Simzer EM, Tzioras M, Querol-Vilaseca M, Sánchez-Aced É, Chang YY, Holt K, McGeachan RI, Rose J, Tulloch J, Wilkins L, Smith C, Andrian T, Belbin O, Pujals S, Horrocks MH, Lleó A, Spires-Jones TL. Synaptic oligomeric tau in Alzheimer’s disease - A potential culprit in the spread of tau pathology through the brain. Neuron. 2023;111(14):2170–e21836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tong L, Thornton PL, Balazs R, Cotman CW. β-amyloid-1–42 impairs activity-dependent cAMP-response elementbinding protein signaling in neurons at concentrations in which cell survival is not compromised. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17301–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sweatt JD. The neuronal MAP kinase cascade: a biochemical signal integration system subserving synaptic plasticity and memory. J Neurochem. 2001;76(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rovira C, Arbez N, Mariani J. A(25–35) and A(1–40) act on different calcium channels in CA1 hippocampal neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:1317–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stephan A, Laroche S, Davis S. Generation of aggregated-amyloid in the rat hippocampus impairs synaptic transmission and plasticity and causes memory deficits. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5703–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ. Selkoe D.J. naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid protein potently inhibit hippocampal longterm potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Snyder EM, Nong Y, Almeida CG, Paul S, Moran T, Choi EY, Nairn AC, Salter MW, Lombroso PJ, Gouras GK, Greengard P. Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking by amyloid-beta. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(8):1051–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bono F, Fiorentini C, Mutti V, Tomasoni Z, Sbrini G, Trebesova H, Marchi M, Grilli M, Missale C. Central nervous system interaction and crosstalk between nAChRs and other ionotropic and metabotropic neurotransmitter receptors. Pharmacol Res. 2023;190:106711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dong XX, Wang Y, Qin Z. Molecular mechanisms of excitotoxicity and their relevance to pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009;30:379–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Marchi M, Grilli M. Presynaptic nicotinic receptors modulating neurotransmitter release in the central nervous system: functional interactions with other coexisting receptors. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;92(2):105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ji D, Lape R, Dani JA. Timing and location of nicotinic activity enhances or depresses hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2001;31:131–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kawamata J, Suzuki S, Shimohama S. Enhancement of nicotinic receptors alleviates cytotoxicity in neurological disease models. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2011;2(3):197–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Furlow PW, et al. Abeta oligomer-induced aberrations in synapse composition, shape, and density provide a molecular basis for loss of connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2007;27:796–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mesulam MM, C. Nucleus basalis (Ch4) and cortical cholinergic innervation in the human brain: observations based on the distribution of acetylcholinesterase and choline acetyltransferase. J Comp Neurol. 1988;275:216–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Levey AI, Wainer BH, Rye DB, Mufson EJ, Mesulam MM. Choline acetyltransferase-immunoreactive neurons intrinsic to rodent cortex and distinction from acetylcholinesterase-positive neurons. Neuroscience. 1984;13:341–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Palop JJ, Chin J, Roberson ED, Wang J, Thwin MT, Bien-Ly N, Yoo J, Ho KO, Yu GQ, Kreitzer A, Finkbeiner S, Noebels JL, Mucke L. Aberrant excitatory neuronal activity and compensatory remodeling of inhibitory hippocampal circuits in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2007;55(5):697–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vladimir-Kneževi´c S, Blažekovi´c B, Kindl M, Vladi´c J, Lower-Nedza AD, Brantner AH. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory, antioxidant and phytochemical properties of selected medicinal plants of the Lamiaceae family. Molecules. 2014;19:767–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hasanein P, Shahidi S. Preventive effect of Teucrium Poliumon learning and memory deficits in diabetic rats. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(1):BR41–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bahramikia S, Yazdanparast R. Phytochemistry and Medicinal Properties of Teucrium polium L. (Lamiaceae). Phytother Res. 2012;26(11):1581–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 88.Wang H, Xu Y, Yan J, Zhao X, Sun X, Zhang Y, Guo J, Zhu C. Acteoside protects human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells against beta-amyloid-induced cell injury. Brain Res. 2009;1283:139–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kurisu M, Miyamae Y, Murakami K, Han J, Isoda H, Irie K, Shigemor H. Inhibition of amyloid β aggregation by Acteoside, a phenylethanoid glycoside. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013;77:1329–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Korkina L, Mikhal’chik E, Suprun M, Pastore S. DT. Molecular mechanisms underlying wound healing and anti-inflammatory properties of naturally occurring biotechnologically produced phenylpropanoid glycosides. Cell Mol Biology. 2006;53:78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ljubuncic P, Dakwar S, Portnaya I, Cogan U, Azaizeh H, Bomzon A. Aqueous extracts of Teucrium polium possess remarkable antioxidant activity in vitro. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2006;3(3):329–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mousavi SM, Niazmand S, Hosseini M, Hassanzadeh Z, Sadeghnia HR, Vafaee F, Keshavarzi Z. Beneficial effects of Teucrium Polium and Metformin on Diabetes-Induced memory impairments and brain tissue oxidative damage in rats. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;2015:493729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]