Abstract

Carbohydrate polymers in their cellular context display highly polymorphic structures and dynamics essential to their diverse functions, yet they are challenging to analyze biochemically. Proton-detection solid-state NMR spectroscopy offers high isotopic abundance and sensitivity, enabling rapid and high-resolution structural characterization of biomolecules. Here, an array of 2D/3D 1H-detection solid-state NMR techniques are tailored to investigate polysaccharides in fully protonated or partially deuterated cells of three prevalent pathogenic fungi: Rhizopus delemar, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Candida albicans, representing filamentous species and yeast forms. Selective detection of acetylated carbohydrates reveals fifteen forms of N-acetylglucosamine units in R. delemar chitin, which coexists with chitosan as separate domains or polymers and associates with proteins only at limited sites. This is supported by distinct order parameters and effective correlation times of their motions, analyzed through relaxation measurements and model-free analysis. Five forms of α−1,3-glucan with distinct structural origins and dynamics were identified in A. fumigatus, important for this buffering polysaccharide to perform diverse roles of supporting wall mechanics and regenerating soft matrix under antifungal stress. Eight α−1,2-mannan sidechain variants in C. albicans were resolved, highlighting the crucial role of mannan sidechains in maintaining interactions with other cell wall polymers to preserve structural integrity. These methodologies provide novel insights into the functional structures of key fungal polysaccharides and create new opportunities for exploring carbohydrate biosynthesis and modifications across diverse organisms.

Keywords: Solid-state NMR, 1H detection, carbohydrate, fungi, structural polymorphism, dynamics, cell wall, chitin, glucan, mannan

INTRODUCTION

Carbohydrate and glycoconjugates, such as polysaccharides, glycoproteins, proteoglycans, and glycolipids, play critical roles in immunobiological processes and cellular communication, act as energy and carbon reservoirs, and provide structural support to cells across various organisms1–4. The carbohydrate-rich cell walls of plants, fungi, and bacteria are crucial for maintaining cell shape and integrity, while also regulating mechanical properties, adhesion, and extensibility4–5. In addition, the structure and biosynthesis of microbial carbohydrates serve as key targets for the development of antibiotics and antifungal therapies aimed at addressing the rising challenge of antibiotic and antifungal resistance6–9. The biological functions of carbohydrates are largely dictated by their structure and properties; however, these molecules are typically highly complex in their native cellular state10–11. This complexity arises from several factors, including diverse covalent linkages between monosaccharide units and their linkage to other molecules, such as proteins and lipids, highly variable monosaccharide compositions, broad conformational distributions, higher-order supramolecular assemblies, interactions with neighboring molecules, and extensive chemical modifications, such as acetylation and methylation12–13. Such complexity has presented challenges for high-resolution characterization of cellular polysaccharides13.

In recent years, solid-state NMR spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for correlating the structure and function of polysaccharides in intact cells and tissues without requiring dissolution or extraction, and when integrated with structural insights from biochemical and imaging techniques, it provides a comprehensive understanding of polysaccharide organization and interactions14–16. Applications to bacterial samples have enabled the quantification of molecular composition, provided insights into cell wall architecture and antibiotic responses, and identified structural factors influencing cell adherence and biofilm formation17–21. In plants, solid-state NMR has unveiled the overlooked role of pectin in interacting with cellulose, as well as the impact of pectin methylation and calcium chelation in primary plant cell walls22–24. It has also revealed the diverse helical screw conformations of xylan that facilitate its interactions with cellulose and lignin in secondary plant cell walls25–29. In fungal species, solid-state NMR has been instrumental in defining the structural roles of key polysaccharides—including chitin, glucans, chitosan, mannan, and galactan-based polymers—in cell wall organization, capsule structure, and the melaninization process30–35. Most of these studies utilize 13C and 15N to resolve the vast number of distinct sites in carbohydrates and proteins within the cellular samples, but 1H offers higher sensitivity, faster acquisition, and reduced sample requirements due to its greater gyromagnetic ratio and natural isotopic abundance. Meanwhile, advancements in 1H-based solid-state NMR for protein structural biology inspire efforts to adapt these methods for systematic investigations of carbohydrate polymers with diverse structures36–39.

Direct detection of protons in biomolecular solid-state NMR was first introduced for peptides and proteins through the perdeuteration approach, which enhances spectral resolution by replacing protons with deuterium at non-exchangeable sites while allowing partial reprotonation at exchangeable sites, thereby significantly reducing proton density40–41. Subsequent advancements, including isotopic dilution, fast magic-angle spinning (MAS), high-field magnets, and triple-resonance experiments, facilitated the determination of protein three-dimensional structures36–38, 40–47. Improvements in probe technology have enabled increasingly rapid sample spinning, with Samoson and colleagues recently achieving 160–170 kHz MAS48–50. The commercial availability of ultra-high magnetic fields, such as 1.2 GHz (28 Tesla)42, along with advanced sample preparation protocols51–55, has greatly expanded the applicability of ultrafast MAS techniques to diverse biological systems, including globular microcrystalline proteins48, 56, disordered proteins57, membrane proteins58, nucleic acids59, viruses e.g., HIV60 and SARS-CoV-261, biofilms62, and amyloids63–64. Fast-MAS techniques have also been widely applied to unlabeled small molecules, including pharmaceutical drugs, facilitating the identification of hetero- and homo-synthons, characterization of crystal forms (e.g., salt cocrystals and continuum forms), and elucidation of hydrogen-bonding networks and three-dimensional crystal packing arrangements65–70.

1H-detection and ultrafast MAS have also been used to determine protein dynamics. The spin relaxation process provides valuable information about local protein motions, but in solids, unaveraged coherences significantly influence relaxation, complicating the quantification of dynamics. These unaveraged coherences are largely eliminated by applying ultrafast MAS rates in combination with sample perdeuteration, which, along with advanced spin relaxation models, enable quantitative analysis of protein motions across a wide range of timescales, including fast motions (ps-ns), slow motions (ns-μs), and slow conformational dynamics (μs-ms)71–73. These methods were initially applied to small globular proteins using the simple model-free (SMF) approach, revealing order parameters and effective correlation times, while the extended model-free (EMF) approach enabled the observation of motions at two independent timescales, including fast and slow motions, and relaxation dispersion methods were used to investigate slow conformational dynamics71, 74–78. The development of the Gaussian axial fluctuation (GAF) model revealed anisotropic collective protein motion, and its incorporation into the SMF approach enabled the analysis of both local and global motions in membrane proteins79–81. When integrated into the EMF model, GAF allowed the observation of both collective slow motions and fast local motions in membrane proteins82. Subsequently, a “dynamics detector method” was implemented to visualize dynamics across a wide range of timescales83–84, while ultrafast MAS enabled the direct determination of order parameters through heteronuclear dipolar recoupling85–87. Altogether, fast MAS and relaxation models enable the quantitative measurement of protein dynamics.

Despite these advancements, the application of proton detection methods to the characterization of carbohydrate polymers, particularly in intact cells, remains relatively limited. Hong and colleagues utilized proton-detection experiments under moderately fast MAS to investigate the structure and dynamics of mobile pectin and semi-mobile hemicellulose, as well as their interactions with cellulose in primary plant cell walls88–89. Baldus and colleagues developed scalar- and dipolar-coupling-based techniques to examine the structural organization of carbohydrates in the cell walls of a mushroom-forming fungus Schizophyllum commune31, 34, 90. Schanda, Loquet, Simorre, and colleagues have employed ultrafast MAS to study bacterial peptidoglycan and, more recently, capsule polysaccharides in the yeast cells of Cryptococcus neoformans33, 91–92. We have utilized proton detection to analyze mobile and rigid polysaccharides in several fungal pathogens, observing the unique capability of 1H detection in sensing and resolving local structural variations of carbohydrates within a cellular context93–95.

In this study, we adapt a suite of proton-detected solid-state NMR techniques, originally developed for protein structural determination, to investigate the structural polymorphism of polysaccharides. A range of 2D/3D correlation experiments, utilizing engineered polarization transfer pathways through scalar and dipolar couplings, enables selective filtering of resonances from acetylated and amino sugars while mapping the covalently bonded carbon network in both rigid and mobile carbohydrates. Relaxation measurements of 13C R1 and 13C R1ρ, analyzed using simple model-free formalism, allowed for the quantification of order parameters and effective correlation times of motions occurring on the picosecond to nanosecond timescale. These methods were applied to fully protonated and partially deuterated cells of three pathogenic fungal species that cause life-threatening infections in over 600,000 patients worldwide each year, with high mortality even after treatment96. The species studied include the filamentous fungi R. delemar and A. fumigatus, major causes of severe infections like mucormycosis and invasive aspergillosis, as well as the yeast cells of C. albicans, the leading cause of candidemia, the fourth most common bloodstream infection in hospitalized patients97–98. These fungal species are also the top three contributors to fungal co-infections in COVID-19 patients99. The high-resolution of 1H, combined with 13C and 15N, provides unprecedented insight into the structural variations of key fungal polysaccharides, including chitin, chitosan, mannan, α-glucan, and β-glucan, thereby laying the foundation for further exploration of the structural and biochemical origins of their structural polymorphism and functional significance in the cellular environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation 13C,15N-labeled and deuterated cells of four fungal species.

In this study, intact cells from four fungal species, including the mycelia materials of two filamentous fungi, Aspergillus fumigatus and Rhizopus delemar, and the yeast cells of Candida albicans, were prepared for 1H-detected solid-state NMR experiments. Two A. fumigatus samples were prepared in both protonated and deuterated forms, while all the other samples are fully protonated. All fungal cells were uniformly 13C, 15N-labeled using growth media enriched with 13C-glucose and 15N-ammonium sulfate or 15N-sodium nitrate (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories). For NMR analysis, approximately 5 mg of each sample was packed into a 1.3 mm magic-angle spinning (MAS) rotor (Cortecnet) for measurements on a 600 MHz spectrometer at MSU Max T. Roger NMR facility and an 800 MHz NMR at National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (Tallahassee, FL), while approximately 7 mg of material was loaded into a 1.6 mm rotor (Phoenix NMR) for measurements on an 800 MHz spectrometer at MSU Max T. Roger NMR facility. The cultivation protocols for each fungal species are described below.

A batch of A. fumigatus culture (strain RL 578) was grown in a protonated liquid medium containing 13C-glucose (10.0 g/L) and 15N-sodium nitrate (6.0 g/L), adjusted to pH 6.5. Separately, ten A. fumigatus cultures were prepared using deuterated conditions by gradually increasing the proportion of D2O from 10% to 100%, with 10% increment each time. Fully adapted cultures were maintained in 100% D2O with the minimal medium containing protonated 13C-glucose (10.0 g/L) and 15N-sodium nitrate (6.0 g/L) for 7 days in 50 mL liquid cultures within 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks, shaken at 210 rpm at 30 °C. Mycelia were harvested by centrifugation (5000 rpm, 10 min) and subjected to four sequential washes with 10 mM PBS (pH 6.5).

R. delemar (strain FGSC-9543) was initially cultivated on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA; 15 g/L) at 33 °C for 2 days following inoculation with a scalpel-cut spore fragment placed at the center of the plate. Subsequently, the fungus was transferred to a liquid medium containing Yeast Nitrogen Base (YNB; 17 g/L, without amino acids), 13C-glucose (10.0 g/L), and 15N-ammonium sulfate (6.0 g/L). The culture was maintained at 30 °C for 7 days with the pH adjusted to 7.0. Following growth, cells were harvested by centrifugation (7000 rpm, 20 min) and washed with 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4; Thermo Fisher Scientific) to remove small molecules and excess ions.

C. albicans (strain JKC2830) was cultivated in a liquid YNB-based medium (0.67% YNB, 10.0 g/L or 2% 13C-glucose, and 5 g/L 15N-ammonium sulfate) in 50 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. Cultures were incubated at 30 °C with shaking (20 rpm, Corning LSE) for 24 hours. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 15 min, and the supernatant was discarded.

Solid-state NMR experiments.

Solid-state NMR experiments were conducted using three high-field NMR spectrometers, including a Bruker Avance Neo 800 MHz (18.8 T) spectrometer at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (Tallahassee, FL) equipped with a custom-built 1.3 mm triple-resonance magic angle spinning (MAS) probe, a Bruker Avance-NEO 600 MHz (14.4 T) spectrometer at Michigan State University fitted with a Bruker 1.3 mm triple-resonance HCN probe, and a Bruker Avance-NEO 800 MHz (18.8 T) spectrometer, also at Michigan State University, with a Phoenix 1.6 mm triple-resonance HXY probe and a Bruker 3.2 mm HCN probe. Sodium trimethylsilylpropanesulfonate (DSS) was added to all samples for calibration of temperature and referencing of 1H chemical shifts. The 13C chemical shifts were externally calibrated relative to the tetramethylsilane (TMS) scale using the adamantane methylene resonance at 38.48 ppm as the reference. The methionine amide resonance at 127.88 ppm in the model tripeptide N-formyl-Met-Leu-Phe-OH was used for 15N chemical shift calibration.

A variety of 1H-detected NMR experiments were performed to assign resonances, characterize structural polymorphisms, and investigate the intermolecular packing of cell wall polysaccharides, with pulse sequences illustrated in Figure S1 and phase cycling details provided in Text S1. Experimental conditions varied depending on the fungal and plant species studied, with detailed parameters provided in Tables S1–S4, where R. delemar is described in Table S1, deuterated A. fumigatus in Tables S2, S3, and C. albicans in Table S4. For all experiments conducted on the 600 MHz spectrometer with a 1.3 mm probe, the MAS rate was set to 60 kHz, with a cooling gas temperature of 250 K, resulting in a sample temperature of 300 K. Some samples were also measured on two 800 MHz NMR spectrometers using different probes, MAS frequencies, and temperature conditions, including R. delemar analyzed with a 1.3 mm probe at 60 kHz MAS under 250 K cooling gas and 302 K sample temperature, R. delemar and deuterated A. fumigatus using a 1.6 mm probe at 15 kHz and 40 kHz MAS, and mobile molecular components of C. albicans examined with a 3.2 mm probe at 15 kHz MAS under 280 K cooling gas and 296 K sample temperature.

The rigid molecules of all fungal and plant samples were initially screened using 2D hCH and hNH experiments. Selective detection of acetyl amino sugars was achieved using a 3D hcoCH3coNH experiment, which incorporated two spin-echo periods to allow magnetization transfer via scalar coupling between CO-CH3 and CH3-CO, with a half-echo period set to 4.7 ms44. During this experiment, magnetization transfer from CO to N was achieved through a specific-CP, utilizing a constant amplitude radio frequency (rf) field of 25 kHz on 15N and a tangent-modulated spin-lock amplitude of 35 kHz on 13C, with an optimized CP contact time of 8 ms. Non-acetyl amino sugars were selectively detected using a 2D hc2NH experiment, where selective magnetization transfer from C2 to N was achieved via specific-CP with a contact time of 3 ms at 15 kHz MAS. Intermolecular interactions happening between different rigid biopolymers were investigated using 2D hChH with RFDR (radio frequency-driven recoupling) where the RFDR-XY8 recoupling period was varied from 33 μs to 0.8 ms89, 91.

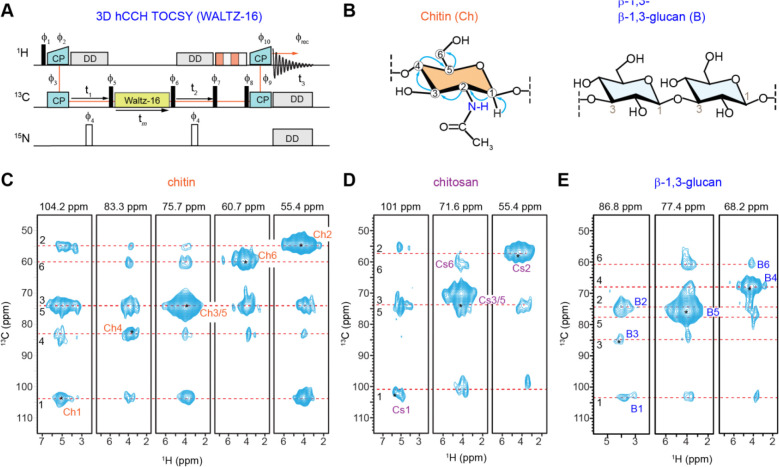

The mobile matrix was detected using two experimental schemes. The 3D hCCH-TOCSY (total correlation spectroscopy) experiment employed WALTZ-16 (wideband alternating-phase low-power technique for zero-residual splitting) mixing for carbon-carbon through-bond connectivity, using a 15 ms mixing period39, 100. Conversely, 3D J-hCCH-TOCSY experiment utilized DIPSI-3 (Decoupling in the presence of scalar interactions) mixing for 25.5 ms to enhance carbon-carbon connectivity within the mobile regions of the cell wall90. Through-bond 1H-13C correlations were analyzed using 2D refocused J-INEPT-HSQC (insensitive nuclei enhanced by polarization transfer – heteronuclear single quantum coherence) with a J-evolution period of 2 ms90, 101.

To investigate molecular dynamics, relaxation filter and dipolar dephasing methods were employed, including 13C-T1-filtered 2D hCH and 1H-T1ρ-filtered 1H-15N HETCOR experiments, utilizing Frequency-Switched Lee-Goldburg (FSLG) sequences for homonuclear dipolar decoupling102. 13C R1 relaxation rates were measured using a 2D hCH experiment, incorporating a π/2–delay–π/2 sequence before the t₁ evolution period, with the delay systematically varied across a series of experiments. Similarly, 13C R1ρ rates were determined using a 2D hCH experiment, where a spin-lock pulse was applied before t₁ evolution, and the delay was incremented over a series of measurements.

For these 2D and 3D experiments, a π/2 pulse was applied with an rf field strength of 100 kHz on 1H, 50 kHz on 13C, and 35.7 kHz on 15N. Initial cross-polarization (CP) transfer from 1H to 13C/15N was performed under double-quantum (DQ) CP) conditions, utilizing an rf field amplitude of 40–50 kHz on ¹H and 10–20 kHz on 13C/15N. To probe both short- and long-range correlations, the second CP contact time was varied between 50 μs and 2.5 ms at 60 kHz MAS. For all proton-detection measurements, slpTPPM (swept low power two-pulse phase modulation) decoupling was applied to the 1H channel with an rf field strength of 10 kHz103. During 1H acquisition, WALTZ-16 decoupling was applied to the 13C and 15N channels, also with an rf field strength of 10 kHz100. In 13C and 15N detection experiments, the SPINAL-64 (small phase incremental alteration, with 64 steps) heteronuclear dipolar decoupling sequence was applied to the 1H channel with an rf field strength of 80 kHz104. Water signal suppression was achieved using the MISSISSIPI (multiple intense solvent suppression intended for sensitive spectroscopic investigation of protonated proteins) sequence105. Data acquisition was performed using the States-TPPI method106, and the acquired data were processed with Topspin version 4.2.0.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Selective detection of acetyl amino sugars and other acetylated carbohydrates

Acetylated polysaccharides are ubiquitous across nearly all living organisms, exhibiting highly diverse acetylation patterns that influence their chemical and conformational structures, as well as their biological activities, including immunomodulatory and antioxidant properties107–108. Among these, acetyl amino sugars—such as N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc), and N-acetylneuraminic acid (NeuNAc)—are key components of structural polysaccharides, glycosphingolipids, and glycoproteins. They play critical roles in microbial cell walls, including chitin and galactosaminogalactan in fungi and peptidoglycan in bacteria, which contribute to mechanical strength (Figure 1A)5, 109. In mammals, sialic acids, predominantly NeuNAc, are abundant on cell surfaces and are crucial for regulating cellular communication110. However, within complex cellular environments, the spectral signals of acetyl amino sugars overlap significantly with those of other carbohydrates and proteins, making their selective detection challenging.

Figure 1. Solid-state NMR analysis of acetyl amino carbohydrates.

(A) Simplified representation of fungal chitin and bacterial peptidoglycan containing acetyl amino sugar units (GlcNAc and MurNAc) that will be selected through their -CO-CH3-NH- segment. The magnetization transfer pathway involving –CO-CH3-NH- group in chitin molecule is depicted. (B) Pulse sequences of 3D hcoCH3coNH experiments which selectively identifies acetyl amino carbohydrates by exploiting NH-CO-CH3 coherence transfer pathway (orange). Magnetization transfer between CO and CH3 carbons occurs through homonuclear scalar couplings, while heteronuclear dipolar couplings facilitate transfer among 1H, 13C and 15N. (C) 2D hCH spectrum (left) and hNH spectrum of a pathogenic fungus R. delemar display signals corresponding to carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids. These signals exhibit significant overlap, as highlighted by the dashed-line box in the hCH spectrum and the amide HN signal originating from both chitin and protein. (D) 2D planes extracted from 3D hcoCH3coNH spectrum of R. delemar reveal the well-resolved signals of chitin alone (top panels) along with signals of Gln (bottom panels). The structural polymorphism of chitin is best evidenced by the multiplicity observed for ChMe-HN and ChNH-HN cross peaks. (E) Signals from most amino acids, e.g., Ala, Leu, and Ile, will be filtered out due to the lack of -CO-CH3-NH- segment, while Asn and Gln may show up in the spectra due the presence of -CO-CH2-NH- segment in the sidechain, where the -CH2- chemical shift can be similar to -CH3-. (F) When modified by eliminating the last step of polarization transfer to NH, this experiment can also be used to select acetylated carbohydrates such as xylan and pectin (e.g. homogalacturonan) in plants. Spectra were measured on an 800 MHz spectrometer using a 1.3 mm probe at 60 kHz MAS. The cooling gas temperature was set to 250 K, with an approximate sample temperature of 302 K.

To address this issue, we developed the 3D hcoCH3coNH experiment by modifying the 3D coCAcoNH pulse sequence widely applied for protein backbone resonance assignment44, to selectively detect acetyl amino sugars through the polarization transfer pathway across their characteristic -NH-CO-CH3- segments (Figure 1B). The effectiveness of this approach is demonstrated using the mycelia of the pathogenic fungus R. delemar, where conventional 2D hCH spectra showed heavy overlap of chitin methyl (ChMe) and carbon 2 (Ch2) signals with protein and lipid peaks, while other chitin carbons mixed with β-glucan and chitosan signals (Figure 1C and Table S5). Furthermore, the amide signals of chitin (ChHN) were indistinguishable from protein backbone amides in standard spectra. In contrast, the hcoCH3coNH spectrum clearly distinguished chitin-specific signals, such as the ChMe-HN cross peaks between chitin methyl carbon and amide proton and the ChN-HN cross peak between nitrogen and amide protons (Figure 1D).

A high degree of structural polymorphism has been reported in fungal chitin, mostly relying on 13C NMR, with A. fumigatus typically exhibiting three to four distinct chitin forms, while the chitin-rich Rhizopus and Mucor species display four to eight forms32, 94, 111. The molecular basis of this polymorphism remains unclear, potentially arising from variations in conformation, hydrogen bonding patterns in chitin crystallites, and the complexity of chitin biosynthesis. While yeasts such as Candida and Saccharomyces possess three to four chitin synthase (CHS) genes belonging to families I, II, and IV, filamentous fungi like Aspergillus and Rhizopus harbor between nine and twenty-three CHS genes115–117. The high resolution of 1H allowed for the differentiation of up to fifteen features in the ChN-HN signals, with the amide 1H chemical shift spanning from 7.8 to 9.2 ppm (Figure 1D), providing a foundation for future studies on chitin biosynthesis by analyzing single-knockout mutants of chitin synthase.

It should be noted that despite the selective filtering of amino acids lacking the -NH-CO-CH3- motif, some glutamine (Gln, Q) signals, such as QCβ-HN and QCγ-HN, persist in the spectra (Figure 1D). This occurs when their sidechain CH2 chemical shifts are close to those of methyl groups, allowing for an NH-CO-CH2 transfer pathway (Figure 1E). However, their 13Cβ and 13Cγ chemical shifts, typically at 26 ppm and 32 ppm, respectively, remain spectroscopically distinct from chitin signals, minimizing interference (Figure 1D).

This experimental approach can be further adapted to detect other acetyl amino sugars, including GalNAc in fungal galactosaminogalactan, GlcNAc and MurNAc in bacterial peptidoglycan, and NeuNAc in mammalian sialic acids. Additionally, by omitting the final step of the polarization transfer pathway, a variant hCOCH3 experiment can be used to selectively detect all acetylated carbohydrates in the cell. This includes acetylated galacturonic acid (GalA) in pectin, which regulates plant growth and stress responses, and acetylated xylose (Xyl) in xylan, which modulates xylan folding on cellulose microfibrils, thereby impacting the structure of mature lignocellulose (Figure 1F)25–26, 112. These applications highlight the potential of this method for investigating the structural and functional roles of acetylation in diverse biological systems.

Selective detection of non-acetyl amino sugars

The second experiment, hc2NH2, inspired by the CαNH experiment commonly used for protein backbone intra-residue assignments, has been specifically designed for the detection of non-acetyl amine sugars such as glucosamine (GlcN) and galactosamine (GalN). For instance, chitosan, produced from chitin by enzymes named chitin deacetylase (CDA), consists of GlcN units that lack the COCH3 motif (Figure 2A), making its identification particularly challenging due to significant spectral overlap between the 15N and 1H signals of chitosan amines (NH2) and those of lysine side chains in proteins. In particular, 15N resonances around 120 ppm are associated with both chitin and proteins, whereas the peak at 33.6 ppm corresponds to both chitosan and lysine (Figure 2B). Although chitosan and lysine exhibit similar 15N (33.6 ppm) and 1H (5.0 ppm) chemical shifts, their 13C chemical shifts are markedly different, with lysine’s NH2-attached 13Cε resonating between 30–40 ppm, while chitosan’s C2 carbon resonates at 55 ppm. This distinction enables the selective detection of chitosan using a 2D 15N-13C correlation experiment, wherein magnetization is transferred from 13C at 55 ppm to 15N at 33.6 ppm, thereby unambiguously identifying chitosan signals (Figure 2C). The cross-polarization conditions optimized for 13C at 55 ppm also capture chitin carbon signals that correlate with 15N at 124 ppm; however, lysine’s NH2-Cε correlation is absent. Furthermore, in the hc2NH2 spectrum, chitin signals are effectively eliminated by transferring magnetization only from the 15N site of 33.6 ppm to 1H, ensuring that only chitosan signals are observed (Figure 2D). In addition to fungal chitosan, it is important to note that non-acetylated amino sugars, such as GlcN and MurN, are also abundant in the peptidoglycan of most Gram-positive bacterial species, contributing significantly to their resistance to lysozyme113. This method can be broadly applied to investigate the structure of non-acetyl amino sugars across various organisms and species.

Figure 2. Selective detection of chitosan in protonated 13C,15N-labeled R. delemar.

(A) Selective detection of chitosan can be achieved using the hC2NH2 experiment, with the pulse sequences shown in the top panel, with the magnetization transfer pathway highlighted. This is achieved through the C2-N-H2 segment of the chitosan (bottom panel). Lysine has a similar Cε-N-H2 segment but will be filtered out in this experiment. (B) 2D hNH spectrum illustrates the overlap of chitosan and lysine amine resonances, alongside chitin and protein amide resonances. (C) 2D NC2 spectrum, obtained with a 13C offset at 55.4 ppm and selective transfer to 15N at 33.6 ppm, highlights specific signals for chitosan. Lysine NH2-Cε cross peak is absent. Chitin C2-protein signals are also observed, though protein amides may overlap with chitin resonances around 55.4 ppm. (D) The 2D hc2NH2 spectrum emphasizes the selective detection of chitosan amine resonances by transferring magnetization from 15N at 33.6 ppm to 1H, effectively suppressing all proteins signals and chitin signal, which are well outside the selectively excited region.

Connectivity and polymorphism in rigid polysaccharides of protonated and deuterated cells

The 3D hCCH TOCSY experiment with a 15 ms WALTZ-16 mixing time (Figure 3A), typically used for sidechain assignment in proteins114, was employed to precisely map through-bond carbon connectivity in rigid polysaccharides (Figure 3B). When applied to fully protonated R. delemar cell walls under moderate magnetic field strength and MAS rate (600 MHz or 14.4 Tesla, and 60 kHz), it allowed for the tracing of the complete six-carbon backbone connectivity of chitin, chitosan, and β-glucan (Figures 3C–E). Structural polymorphism, reflected by peak multiplicity, was observed for all chitin carbons, with the 1H2 chemical shift ranging from 3 ppm to 5.5 ppm (Figure 3C). A similar peak multiplicity was noted for chitosan, where the 1H2 ranged from 2.5 ppm to 5.5 ppm, revealing multiple resolvable peaks (Figure 3D). Although β-glucan is a minor component in R. delemar cell wall, accounting for only 5% of the rigid polysaccharides, its complete carbon connectivity was still observable (Figure 3E). This approach not only enables tracking of carbon connectivity but also provides insight into the structural polymorphism of rigid polysaccharides.

Figure 3. Establishing through-bond and through-space correlations in protonated R. delemar.

(A) Pulse sequences of 3D hCCH TOCSY with WALTZ-16 mixing, which can be used to map carbon connectivity within each carbohydrate component, relying on scalar couplings among 13C nuclei. 2D strips extracted from a 3D hCCH TOCSY spectrum measured on R. delemar with a mixing time of 15 ms are shown for (B) chitin, (C) chitosan, and (E) β−1,3-glucan, capturing multi-bond correlations across six carbons sites within each monosaccharide unit. All spectra were collected on a 600 MHz NMR spectrometer at 60 kHz MAS.

However, we were dissatisfied with the spectral quality. For instance, the 1H lines were extremely broad, which was unacceptable for biomolecular NMR structural characterization. Additionally, we observed that in some regions, not all carbon connectivity was detected in the 2D strips. This could be due to unaveraged 1H-1H dipolar couplings, which may attenuate the signal during TOCSY mixing, as proton decoupling cannot be applied during the mixing period. To address these challenges, we deuterated the fungal cells, drawing inspiration from the protocol used in protein proton solid-state NMR studies, where backbone amides in perdeuterated proteins are back-exchanged to protons, and the proton dilution leads to resolution enhancement36, 115.

To optimize the protocol, we turned to a different pathogenic fungal species, A. fumigatus, whose genome and carbohydrate structure are well characterized and thus serves as a more suitable model system116. The fungus was trained to grow in deuterated media, with the D2O concentration gradually increased by 10% at each step, from 10% to 100%, until the fungi were able to grow in fully deuterated media without exhibiting any stressed phenotype. Since the 13C-glucose and 15N-sodium nitrate used in the medium for carbohydrate biosynthesis are protonated, the cell wall carbohydrates were synthesized in a fully protonated state, preserving 13C-bound protons necessary for structural analysis, while protons at exchangeable sites, such as hydroxyl (−OH) and amide and amine (−NH and −NH2) groups, were replaced by deuterons (Figure 4A). Considering the structure of long glucans, such as α−1,3-glucan, this protocol should decrease the proton density by approximately 30% due to the replacement of three -OH groups with -OD groups, while maintaining the remaining seven CH sites intact within each sugar unit along the glucan chain.

Figure 4. Deuteration of A. fumigatus cell walls for enhancement of 1H resolution.

(A) Structural representation of a deuterated α−1.3-glucan. (B) 2D hCH spectra of rigid carbohydrates in fully protonated (brown) and deuterated (blue) A. fumigatus mycelia. (C) Comparison of 1H linewidths extracted from 2D hCH spectra of protonated (brown) and deuterated (blue) A. fumigatus mycelia. (D) 2D planes extracted from 3D hCCH TOCSY spectrum of deuterated A. fumigatus mycelia with a WALTZ-16 mixing period showing through-bond 13C-13C connectivity of rigid β−1,3-glucans. (E) Polymorphic forms (Aa, Ad, Ae) of α-glucans identified from the strip of the same 3D hCCH TOCSY spectrum. (F) Intermolecular interactions between α- and β−1,3-glucans resolved using 2D hChH spectra with different RFDR mixing times measured on deuterated A. fumigatus mycelia. The spectra were acquired on a 600 MHz spectrometer with the MAS rate of 60 kHz.

Partial deuteration and proton dilution significantly improved the 1H resolution, as demonstrated by the overlay of 2D hCH spectra measured on deuterated and protonated mycelia of A. fumigatus (Figure 4B). The three allomorphs of α−1,3-glucans became distinguishable in the deuterated samples, as reflected by three resolvable peaks corresponding to their H3-C3 cross peaks (Aa3, Ad3, and Ae3), with 13C resonating at 84 ppm and 1H chemical shifts of 4.4 ppm, 4.1 ppm, and 3.6 ppm. The 1D 1H cross-sections extracted from the 2D spectra indicated that the 1H lines were narrowed by one-fourth to one-half due to partial deuteration (Figure 4C and Figure S2, S3). This significant effect likely arises from the combination of three mechanisms: first, a direct impact due to diminished 1H-1H homonuclear dipolar couplings, second, the removal of contributions from hydroxyl proton signals, and third, a decrease in 1H spin diffusion caused by lower 1H density, which enhances site specificity for each 13C-1H cross peak in the 2D spectrum.

The application of the same 3D hCCH TOCSY with WALTZ-16 mixing to partially deuterated A. fumigatus cells enabled us to unambiguously trace the carbon connectivity in rigid β−1,3-glucans (Figure 4D), and, more importantly, resolved the complete carbon connectivity of three new allomorphs of α−1,3-glucans, named Aa, Ad, and Ae (Figure 4E and Table S6). These α−1,3-glucan forms shared identical 13C chemical shifts but exhibit significantly varied 1H chemical shifts. In previous studies of A. fumigatus, these three 1H-identified allomorphs showed only a single set of 13C peaks and were labeled as Aa, which displayed distinct 13C chemical shifts from the other two forms of α−1,3-glucans (Ab and Ac)117. By combining the 1H and 13C resolution, we are now able to resolve a total of five forms of α−1,3-glucans, each exhibiting structural variations.

We are now able to evaluate the structural functions of these α−1,3-glucans by combining chemical shift information and the origin of their signals in A. fumigatus cultures prepared under different conditions. The consistent ¹³C signals of Aa, Ad, and Ae represent the primary structure of α−1,3-glucan predominantly found in the rigid portion of the mycelial cell walls, consistently observed in multiple strains of A. fumigatus as well as other Aspergillus species, such as A. nidulans and A. sydowii93, 117–118. Therefore, Aa, Ad, and Ae form the rigid domain of Aspergillus cell walls by associating with chitin and a small portion of β-glucans, with variations of local structures leading to their varied ¹H chemical shifts. In contrast, Ab and Ac have fully altered helical screw conformations, as evidenced by distinct 13C chemical shift for their C3 sites, observed in the mobile fraction of A. fumigatus cell walls at very low concentrations. However, their abundance became considerable in both the rigid and mobile phases of A. fumigatus mycelia grown under exposure to echinocandins, an antifungal drug that inhibits β−1,3-glucan biosynthesis117. The coexistence of three different helical screw structures with stress responses may be linked to the biosynthetic complexity arising from the presence of multiple α-glucan synthase (AGS) genes in A. fumigatus, a topic for the next study, likely by connecting NMR with ags mutants119. However, it is clear that the availability of five structural forms allows α−1,3-glucans to play their crucial roles as buffering molecules by supporting the rigid core through interaction with chitin microfibrils and regenerating the matrix when β−1,3-glucans are depleted due to echinocandin antifungal treatment.

We also identified 11 intermolecular cross peaks between α−1,3-glucan and β−1,3-glucan by comparing two 2D hChH spectra measured on the partially deuterated sample with varying RFDR mixing periods of 0.1 ms and 0.8 ms. Extending this experiment to a 3D format by adding an additional ¹H dimension will enable us to further differentiate the various structural forms of α−1,3-glucan and evaluate their specific interactions with β−1,3-glucans, providing insights into polymer packing at the sub-nanometer length scale within the cell wall architecture. It is exciting that such a task has now become feasible using moderate magnetic field strength and MAS frequency, within just a few hours, while working with intact cells.

Resolving the structural complexity of mobile carbohydrates

A characteristic feature of the extracellular matrix in living organisms is its heterogeneous dynamics, wherein polymers are distributed across distinct dynamic domains. This organization typically consists of a rigid core that provides structural stiffness, surrounded by a more mobile matrix. In the fungal cell wall, for instance, chitin and chitosan predominantly contribute to the rigid fraction, while certain polysaccharides, such as α- and β-glucans and mannan, are present in both rigid and mobile phases120. Meanwhile, exopolysaccharides, such as galactosaminogalactan, are exclusively found in the mobile fraction. Recent studies have leveraged advanced NMR techniques to investigate these dynamic domains. Baldus and colleagues utilized a proton-detected 3D 1H-13C J-hCCH-TOCSY (DIPSI-3) experiment (Figure 5A) to assign protein signals and identify the reducing ends of glycans in S. commune90. Inspired by their pioneering work, we have recently applied this approach to characterize the mobile regions of the cell walls in a multidrug resistant fungus named Candida auris, enabling the precise identification of mannans and glucans in their mobile matrix95. Loquet and colleagues have also employed this method to elucidate the organization of mobile capsular polysaccharides in C. neoformans33.

Figure 5. Resonance assignment of mobile carbohydrates in protonated C. albicans.

(A) Pulse sequences of 3D hCCH TOCSY with DIPSI-3 mixing for establishing through-bond carbon connectivity in mobile carbohydrates. (B) Simplified representation of segments in the β-glucan matrix (left) and mannan (right) of C. albicans cell walls. (C) Selected regions of 2D hcCH TOCSY (DIPSI-3) spectrum. (D) Extracted 2D stripes from 3D hCCH TOCSY (DIPSI-3) spectrum resolving 3 types of β−1,3-glucan (types a, b, and c) alongside β−1,3,6-linked Glc site for branching, as well as 8 types of α−1,2-linked Man residues in mannan. The 2D C-C strips were extracted at the proton sites whereas 2D C-H strips were extracted at the carbon sites. The chemical shifts labeled at the top of each panel represent the 1H or 13C site where strips are extracted, and asterisks indicate the corresponding diagonal peak. The experiments were performed on an 18.8 T (800 MHz) spectrometer at 15 kHz MAS.

Here, we highlight the capability of this experiment in resolving the structural polymorphism of mobile matrix polysaccharides, using yeast cells of the prevalent pathogen C. albicans (strain JKC2830) as a model system. The mobile molecules within this fungus, detected via the 2D hcCH TOCSY (DIPSI-3) spectrum, include linear β−1,3-glucans (B) and β−1,6-glucans (H), which are interconnected through β−1,3,6-linked glucopyranose units (BBr) serving as branching points (Figure 5B, C and Figure S4). Additionally, strong signals from mannan polymers, including the α−1,6-mannan backbone (Mn1,6) and α−1,2-mannan sidechains (Mn1,2), were observed. Signals corresponding to small molecules, such as glucose (Glc) and galactose/glucose derivatives (Gl), were also detected; however, these are not the focus of this discussion as they are not structural components of the cell wall.

Strips from the F1-F3 plane (13C-1H) of 3D hCCH TOCSY (DIPSI-3) spectra enabled the identification of three distinct forms of β−1,3-glucans (types a, b, and c), as well as the β−1,3–6-linked branching site (Figure 5D), with their chemical shifts documented in Table S7. Our recent analysis revealed that type-a β−1,3-glucan exhibits chemical shifts consistent with those reported for the triple-helix model, suggesting its role in matrix formation. In contrast, type-b β−1,3-glucan displays correlations with chitin, indicating its association with extended structures on chitin microfibrils. The precise structure of type-c remains unknown, but the complete chemical shift dataset obtained here can serve as a reference for computational modeling to elucidate its structural origin.

While only a single type of α−1,6-mannan signal was observed, indicating a structurally homogeneous backbone, analysis of the 2D strips extracted at 13C chemical shifts of 101.2 ppm, 101.3 ppm, 102.7 ppm, and 99.2 ppm differentiated eight distinct α−1,2-mannose (Mn1,2) structures (Figure 5D). Types a, d, and c could not be distinguished solely by their 13C chemical shifts due to their high degree of similarity, necessitating the use of 1H chemical shifts for effective differentiation. The remaining five types are readily distinguishable by their distinct 13C and 1H chemical shifts at the carbon-1 site. As a major carbohydrate polymer in Candida cell walls, mannan forms fibrillar structures extending on the scale of 100 nm, comprising the outer cell wall layer while also penetrating the inner domain to interact with glucans and chitin5. The α−1,2-mannose sidechains can be covalently linked to the α−1,6-mannan backbone, to other α−1,2-mannose residues along the sidechains of varying lengths, to β−1,2-mannose, phosphate, or α−1,3-mannose121. Recent studies have also identified these sidechains as critical interaction sites for mannan fibrils with other polymers, such as glucans and chitin, with these interactions shifting the mannan fibrils from the mobile to the rigid phase under stress conditions95. This structural diversity likely accounts for the presence of eight distinct α−1,2-mannose residues in C. albicans mannan fibrils. However, precise assignment of these residues to their structural functions will require the integration of 1H solid-state NMR methodologies with biochemical and genomic approaches.

Dynamics filters for separation of rigid polysaccharides from semi-rigid proteins

Cellular biomolecules exhibit a broad range of dynamics, prompting the widespread use of relaxation-filters to either suppress or detect components with specific motional characteristics. For instance, Duan and Hong recently employed 1H-T2-filtered hCH and 13C-T2-filtered INADEQUATE experiments to selectively detect intermediate-amplitude mobile polysaccharides, such as hemicellulose xyloglucan in Arabidopsis and surface cellulose and glucuronoarabinoxylan in Brachypodium, while suppressing signals from both rigid cellulose and highly mobile pectin88. In R. delemar, the dipolar coupling-mediated 1H-13C CP-based spectra preferentially enhance signals from partially rigid molecules, revealing a complex mixture of resonances from proteins, lipids, and polysaccharides, including chitin, chitosan, and glucans (Figure 6A). Longitudinal (13C-T1) relaxation filters with a 10 s delay effectively suppressed signals from semi-rigid proteins and lipids, preserving only those from rigid cell wall polysaccharides, whereas in the dipolar-dephased spectrum, rigid cell wall polysaccharides are selectively depleted, leaving only protein and lipid signals. It should be noted that the carbonyl and methyl group signals of chitin initially overlapped with those of proteins and lipids in 1D 13C CP spectrum, but are unambiguously detected in the protein/lipid-free 13C-T1-filtered spectrum.

Figure 6. Identifying the rigid and semi-rigid cell wall components of R. delemar and A. fumigatus.

(A) Three 1D 13C spectra of R. delemar using CP for detecting all rigid molecules (top), using 13C-T1 filter to select cell wall polysaccharides (middle), and using dipolar-dephasing to select proteins and lipids (bottom). (B) 13C-T1 filtered 2D hCH spectrum retains only signals from rigid cell wall polysaccharides while all protein and lipid signals are eliminated. (C) Overlay of two 1H T1ρ filtered 1H-15N HETCOR spectra with 2.5 ms (red) and 1.5 ms (blue) CP contact times. (D) Order parameters (S2) and effective correlation times (τC, eff) determined using analysis of 13C R1 and 13C R1ρ relaxation rates using model-free approach are shown for R. delemar. Ch: chitin; Cs: chitosan; P/L: protein or lipid. Relaxation experiments were conducted on 600 MHz at 60 kHz MAS. (E) Structural summary of order parameters S2 (blue) and effective correlation time τC, eff (magenta). and (F) Order parameters (S2) and effective correlation times (τC, eff) determined for A. fumigatus polysaccharides. A: α−1,3-glucan; B: β−1,3-glucan.

Similar approaches were applied to the 2D hCH spectrum (Figure 6B), where a 13C-T1 filter effectively suppressed all protein and lipid signals, substantially simplifying the spectrum compared to Figure 1C, and leaving the ChMe and Ch/Cs2 sites unambiguously resolved. The implementation of a 1H T1ρ filter in a 1H-15N heteronuclear correlation experiment also generated polysaccharide-only spectra, revealing chitin (15N 123.7 ppm) and chitosan (15N 33.6 ppm) signals, while depleting protein amide signals (110–130 ppm) and lysine amine signals. These observations have demonstrated that lipids, proteins, and ergosterols reside in the semi-rigid regime, while cell wall polysaccharides are found in the rigid region of R. delemar. The relaxation filters also provide a means to unambiguously visualize cell wall polysaccharides without interference from other molecules.

To determine the order parameters (S2) of polysaccharides and the effective correlation times of their motions (τC, eff), we fitted 13C R1 and 13C R1ρ relaxation rates (Figures. S5–S8) to a spectral density function, with the rate equations provided in Text S2, and these rates were analyzed using a simple model-free formalism (Text S3). In R. delemar, all carbon sites from chitin and chitosan exhibited very slow 13C R1, ranging from 0.06 to 0.15 s−1, while protein and lipid signals showed faster 13C R1 between 0.18 and 0.40 s−1 (Figure 6D and Table S8), explaining why a clean carbohydrate-only spectrum can be obtained by applying a 13C-T1 filter. A similar trend was observed for the 13C R1ρ, which was slow for most chitin/chitosan sites on the range of 15–25−1, except for the most dynamic of chitin carbon 6, whose 13C R1ρ was 47 ± 1 s-1. We noticed that chitin and chitosan exhibit consistent high order parameters ranging from 0.79 to 0.92, with effective correlation times of 10–12 ns for most carbon sites (Figure 6E). This timescale of motion is highly comparable to that observed in microcrystalline β-sheet proteins, where the structurally ordered regions exhibit effective correlation times on the order of tens of nanoseconds71, 122. In contrast, proteins located in the rigid phase of the cell wall displayed lower order parameters and shorter correlation times of 6–9 ns (Figure 6D and Table S8).

Quantification of their dynamical parameters provided novel insights into the protein-carbohydrate interface in R. delemar cell walls. Recently, we have identified the co-localization of proteins and carbohydrates in this fungus, confirmed through several strong intermolecular cross peaks between isoleucine residues and chitin/chitosan signals within the rigid phase94. Chitosan primarily interacted with the isoleucine γ1 site, whereas chitin was positioned on the opposite side, stabilized through contacts with both isoleucine γ1 and γ2 sites94. This also enabled the rigid portion of proteins to withstand a prolonged 15-ms proton-assisted recoupling (PAR) period123–124, demonstrating their semi-ordered nature—an observation made for the first time in any fungal species. However, the distinct order parameters and correlation times quantified in this study suggest that bulk wall-incorporated proteins are not homogeneously integrated with carbohydrates. Instead, despite anchoring through hydrophobic amino acid residues, structured proteins in R. delemar cell walls exhibit entirely different dynamic profiles.

The results also provide insight into the colocalization of chitin and chitosan in R. delemar cell walls. Since chitosan is generated by chitin deacetylase after chitin microfibrils are deposited into the fungal cell wall125, there has been ongoing debate about whether these two polysaccharides coexist within the same polymer (e.g., -GlcN-GlcNAc-GlcN-GlcNAc-) or form separate polymers or structural domains. The significantly shorter effective correlation time of chitosan C1 (6.8 ± 0.4 ns) compared to chitin C1 (11.6 ± 0.6 ns) suggests that they exist as either distinct polymers or separate structural domains rather than being uniformly mixed within a single polymer chain (Figure 6E). This structural finding also provides insight into the mode of action of chitin deacetylase125.

Extending this approach to partially deuterated A. fumigatus provided insights into the functional differences between β- and α-glucans, as well as their polymorphic forms (Figure 6F). α-Glucans exhibited slower 13C R1 (0.05–0.10 s−1) and R1ρ (4–10 s−1, except for the mixed A2/5 peak), whereas β-glucans displayed faster 13C R1 (0.08–0.23 s−1) and R1ρ (11–23 s−1). Consequently, α-glucans had noticeably larger order parameters (0.91–0.95) than β-glucans (0.79–0.91), except at the C6 sites where signal overlap occurred (Figures 6E, F and Table S9). The obtained order parameters are larger than expected for glucans in the matrix, likely resulting from partial deuteration, which reduces 1H-1H dipolar couplings, leading to longer relaxation times and higher order parameters. Overall, the trend aligns with structural concepts established through solid-state NMR, particularly the observation of intermolecular interactions, reinforcing that α−1,3-glucan—rather than β−1,3-glucan—is the key component physically packed with chitin microfibrils in A. fumigatus mycelial cell walls. Additionally, the three rigid α−1,3-glucan forms (A3a, A3d, A3e), distinguishable by their 1H chemical shifts at the C3 site, exhibited similar structural properties, with consistent order parameters of 0.95–0.98 and effective correlation times of 4.5–5.0 ns (Figure 6F). This confirms our hypothesis that these coexisting forms share only local structural variations within the rigid α−1,3-glucan domain, in contrast to the dynamically distinct A3b and A3c forms, which are implicated in biosynthetic differences and stress-compensatory mechanisms117.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

In this study, we have demonstrated the power of a versatile collection of 2D/3D 1H-detection solid-state NMR techniques in deciphering the highly polymorphic structures and heterogeneous dynamic profiles of cellular carbohydrates. The availability of different functional groups, substitutions, and distinct dynamics allowed for the clean selection of specific carbohydrate polymers within a cellular context. Partial deuteration of microbial cultures also enables the acquisition of 1H-detection spectra with reasonable quality under moderate magnetic field strength and MAS frequencies. We also showed that site-specific dynamics of polysaccharides can be determined through relaxation measurements, with the data analyzed using the simple model-free formalism. These approaches represent a significant advancement in carbohydrate structural analysis, offering unprecedented resolution and clarity for the successful identification of the carbon skeletons of polymorphic polysaccharide forms, resolving their structural variations, and mapping their spatial interactions.

The results provided novel insights into the structural and functional complexity of cell wall polysaccharides in three prevalent pathogenic fungal species. High-resolution 1H data from R. delemar revealed that chitin is even more complex than what was recently observed using 13C,15N-based approaches, necessitating a follow-up study to explore the biochemical and structural origin of this polymorphism. We also found that structural proteins complexed with chitin and chitosan maintained their unique dynamical profiles, indicating they were not well integrated into the carbohydrate domains. The differences in order parameters and correlation times between chitin and chitosan excluded the possibility that their signals originated from GlcN and GlcNAc units well-mixed within the same polymer, instead supporting the notion of domain separation or distinct polymer chains. The structural function of α-glucans over β-glucans in preferentially associating with chitin and supporting the rigid scaffold in Aspergillus mycelial cell wall was confirmed. Furthermore, the number of polymorphic structures of α−1,3-glucans has now increased to five, with three forms observed in the rigid fraction of Aspergillus cell walls, exhibiting highly comparable dynamics and correlation times with only local variations in structures, and two forms induced by stress conditions, displaying fully rearranged helical screw conformations and evenly distributed in both the rigid and mobile domains of the cell wall. Finally, we resolved a large number of α−1,2-Man forms in C. albicans, revealing a unique structural feature of these large mannan fibrils with relatively uniform backbones but highly diverse α−1,2-linked sidechains that are crucial for interacting with other components in the cell wall. These new insights enhance our understanding of the structure and function of chitin, chitosan, glucans, and mannan in maintaining the architecture of fungal cell walls.

The availability of such capabilities has opened several new research avenues. Firstly, it enables the exploration of the polymorphic structures of chitin and chitosan by linking them to the numerous genes encoding chitin synthases and deacetylases, through the mapping of 1H and 13C/15N chemical shifts in chs and cda mutants and treatment by inhibitors. This approach also facilitates the investigation of the polymorphic structures and biosynthetic complexity of α-glucans, such as through studies of ags mutants, as well as mannan-based biopolymers like galactomannan, manoproteins, and mannan fibrils, which are prevalent in various fungal species. While demonstrated on pathogenic fungi, these techniques offer high-resolution characterization of carbohydrates across diverse organisms, enabling the mapping of acetylation patterns and the examination of amino carbohydrate distribution in intact bacterial, plant, and mammalian cells, thereby providing a deeper understanding of the structural complexity and functional diversity of crucial carbohydrates in cellular systems.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01AI173270 and the National Science Foundation grant MCB-2308660. A portion of this work was performed at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, which is supported by National Science Foundation Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-2128556 and the State of Florida, and supported in part by the National Resource for Advanced NMR Technology via NIH RM1-GM148766.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AGS

α-glucan synthase

- CDA

chitin deacetylase

- CHS

chitin synthase

- CP

cross polarization

- DIPSI-3

Decoupling in the presence of scalar interactions

- DQ

double-quantum

- DSS

Sodium trimethylsilylpropanesulfonate

- EMF

extended model-free

- FSLG

Frequency-Switched Lee-Goldburg

- GAF

Gaussian axial fluctuation

- GalA

galacturonic acid

- GalN

galactosamine

- GalNAc

N-acetylgalactosamine

- GlcN

glucosamine

- GlcNAc

N-acetylglucosamine

- HSQC

heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- INEPT

insensitive nuclei enhanced by polarization transfer

- MAS

magic-angle spinning

- MISSISSIPI

multiple intense solvent suppression intended for sensitive spectroscopic investigation of protonated proteins

- MurNA

c N-acetylmuramic acid

- NeuNAc

N-acetylneuraminic acid

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- PAR

proton-assisted recoupling

- rf

radio frequency

- RFDR

radio frequency-driven recoupling

- slpTPPM

swept low power two-pulse phase modulation

- SMF

simple model-free

- SPINAL-64

small phase incremental alteration, with 64 steps

- TMS

tetramethylsilane

- TOCSY

total correlation spectroscopy

- WALTZ-16

wideband alternating-phase low-power technique for zero-residual splitting

- Xyl

xylose

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Supplementary Text regarding phase cycling of the pulse sequences, relaxation rate equations, simple model free formalism, Figures S1–S8 and Tables S1–S9 for additional NMR spectra, chemical shifts, and experimental conditions, and supplementary references.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rabinovich G. A.; van Kooyk Y.; Cobb B. A., Glycobiology of Immune Responses. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 2012, 1253, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varki A., Biological Roles of Glycans. Glycobiology 2017, 27, 3–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor C. M.; Roberts I. S., Capsular Polysaccharides and Their Role in Virulence. Concepts Bacterial Virulence 2005, 12, 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosgrove D. J., Structure and growth of plant cell walls Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 340–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gow N. A. R.; Lenardon M. D., Architecture of the dynamic fungal cell wall. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 248–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher M. C.; Alastruey-Izquierdo A.; Berman J.; Bicanic T.; Bignell E. M.; Bowyer P.; Bromley M. J.; Bruggemann R.; Garber G.; Cornely O. A.; Gurr S. J.; Harrison T. S.; Kuijper E.; Rhodes J.; Sheppard D. C.; Warris A.; White P. L.; Xu J.; Zwaan B.; Verweij P. E., Tackling the emerging threat of antifungal resistance to human health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 557–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghannoum M. A.; Rice L. B., Antifungal agents: mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12 (4), 501–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bush K.; Courvalin P.; Dantas G.; Davies J.; Eisenstein B.; Huovinen P.; Jacoby G. A.; Kishony R.; Kreiswirth B. N.; Kutter E.; Lerner S.; Levy S.; Lewis K.; Pamela Y.; Zgurskaya H. I., Tackling antibiotic resistance Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 894–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shukla R.; Lavore F.; Maity S.; Derks M. G. N.; Jones C. R.; Vermeulen B. J. A.; Melcrova A.; Morris M. A.; Becker L. M.; Wang X.; Kumar R.; Medeiros-Silva J.; van Beekveld R. A. M.; Bonvin A. M. J. J.; Lewis K.; Weingrth M., Teixobactin kills bacteria by a two-pronged attack on the cell envelope. Nature 2022, 608, 390–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weis W. I.; Drickamer K., Structural Basis of Lectin-Carbohydrate Recogonition. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996, 65, 441–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dwek R. A., Glycobiology: Toward Understanding the Function of Sugars. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 683–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao W.; Deligey F.; Shekar S. C.; Mentink-Vigier F.; Wang T., Current limitations of solid-state NMR in carbohydrate and cell wall research. J. Magn. Reson. 2022, 341, 107263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duus J.; Gotfredsen C. H.; Bock K., Carbohydrate Structural Determination by NMR Spectroscopy: Modern Methods and Limitations. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 4589–4614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chow W. Y.; De Paëpe G.; Hedinger S., Biomolecular and Biological Applications of Solid-State NMR with Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Enhancement. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 9795–9847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghassemi N.; Poulhazan A.; Deligey F.; Mentink-Vigier F.; Marcotte I.; Wang T., Solid-State NMR Investigations of Extracellular Matrixes and Cell Walls of Algae, Bacteria, Fungi, and Plants. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 10036–10086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reif B.; Ashbrook S. E.; Emsley L.; Hong M., Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Nat. Rev. Methos Primers 2021, 1, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kern T.; Giffard M.; Hediger S.; Amoroso A.; Giustini C.; Bui N. K.; Joris B.; Bougault C.; Vollmer W.; Simorre J.-P., Dynamics characterization of fully hydrated bacterial cell walls by solid-state NMR: evidence for cooperative binding of metal ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 10911–10919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romaniuk J. A. H.; Cegelski L., Bacterial cell wall composition and the influence of antibiotics by cell-wall and whole-cell NMR. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2015, 370, 1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xue Y.; Yu C.; Ouyang H.; Huang J.; Kang X., Uncovering the Molecular Composition and Architecture of the Bacillus subtilis Biofilm via Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 11906–11923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byeon C. H.; Kinney T.; Saricayir H.; Hansen K. H.; Scott F. J.; Sirinivasa S.; Wells M. K.; Mentink-Vigier F.; Kim W.; Akbey Ü., Ultrasensitive Characterization of Native Bacterial Biofilms via Dynamic Nuclear Polarization-Enhanced Solid-State NMR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, in press, e202418146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reichhardt C.; Cegelski L., Solid-State NMR for Bacterial Biofilms Mol. Phys. 2014, 112, 887–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Temple H.; Phyo P.; Yang W.; Lyczakowski J. J.; Echevarria-Poza A.; Yakunin I.; Parra-Rojas J. P.; Terrett O. M.; Saez-Aguayo S.; Dupree R.; Orellana A.; Hong M.; Dupree P., Golgi-localized putative S-adenosyl methionine transporters required for plant cell wall polysaccharide methylation. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 656–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirui A.; Du J.; Zhao W.; Barnes W.; Kang X.; Anderson C. T.; Xiao C.; Wang T., A pectin methyltransferase modulates polysaccharide dynamics and interactions in Arabidopsis primary cell walls: evidence from solid-state NMR. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 270, 118370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez Garcia M.; Zhang Y.; Hayes J.; Salazar A.; Zabotina O. A.; Hong M., Structure and interactions of plant cell-wall polysaccharides by two-and three-dimensional magic-angle-spinning solid-state NMR. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 989–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simmons T. J.; Mortimer J. C.; Bernardinelli O. D.; Poppler A. C.; Brown S. P.; deAzevedo E. R.; Dupree R.; Dupree P., Folding of xylan onto cellulose fibrils in plant cell walls revealed by solid-state NMR. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duan P.; Kaser S.; Lyczakowski J. J.; Phyo P.; Tryfona T.; Dupree P.; Hong M., Xylan Structure and Dynamics in Native Brachypodium Grass Cell Walls Investigated by Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 15460–15471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirui A.; Zhao W.; Deligey F.; Yang H.; Kang X.; Mentink-Vigier F.; Wang T., Carbohydrate-aromatic interface and molecular architecture of lignocellulose. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang X.; Kirui A.; Dickwella Widanage M. C.; Mentink-Vigier F.; Cosgrove D. J.; Wang T., Lignin-polysaccharide interactions in plant secondary cell walls revealed by solid-state NMR. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terrett O. M.; Lyczakowski J. J.; Yu L.; Iuga D.; Franks W. T.; Brown S. P.; Dupree R.; Dupree P., Molecular architecture of softwood revealed by solid-state NMR. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 4978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chatterjee S.; Prados-Rosales R.; Itin B.; Casadevall A.; Stark R. E., Solid-state NMR Reveals the Carbon-based Molecular Architecture of Cryptococcus neoformans Fungal Eumelanins in the Cell Wall J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 13779–13790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ehren H. L.; Appels F. V. W.; Houben K.; Renault M. A. M.; Wosten H. A. B.; Baldus M., Characterization of the cell wall of a mushroom forming fungus at atomic resolution using solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Cell Surf. 2020, 6, 100046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamon G.; Lends A.; Valsecchi I.; Wong S. S. W.; Duprès V.; Lafont F.; Tolchard J.; Schmitt C.; Mallet A.; Grélard A.; Morvan E.; Dufourc E. J.; Habenstein B.; Guijarro J. I.; Aimanianda V.; Loquet A., Solid-state NMR molecular snapshots of Aspergillus fumigatus cell wall architecture during a conidial morphotype transition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2212003120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lends A.; Lamon G.; Delcourte L.; Surny-Leclere A.; Grelard A.; Morvan E.; Abdul-Shukkoor M. B.; Berbon M.; Vallet A.; Habenstein B.; Dufourc E. J.; Schanda P.; Aimanianda V.; Loquet A., Molecular Distinction of Cell Wall and Capsular Polysaccharides in Encapsulated Pathogens by In Situ Magic-Angle Spinning NMR Techniques. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Safeer A.; Kleijburg F.; Bahri S.; Beriashvili D.; Veldhuizen E. J. A.; van Neer J.; Tegelaar M.; de Cock H.; Wösten H. A. B.; Baldus M., Probing Cell-Surface Interactions in Fungal Cell Walls by High-Resolution 1H-Detected Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Chem. Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202202616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang X.; Kirui A.; Muszynski A.; Widanage M. C. D.; Chen A.; Azadi P.; Wang P.; Mentink-Vigier F.; Wang T., Molecular architecture of fungal cell walls revealed by solid-state NMR. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Le Marchand T.; Schubeis T.; Bonaccorsi M.; Paluch P.; Lalli D.; Pell A. J.; Andreas L. B.; Jaudzems K.; Stanek J.; Pintacuda G., 1H-Detected Biomolecular NMR under Fast Magic-Angle Spinning. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 9943–10018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Su Y.; Andreas L. B.; Griffin R. G., Magic Angle Spinning NMR of Proteins: High-Frequency Dynamic Nuclear Polarization and 1H Detection. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015, 84, 465–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou D. H.; Shah G.; Cormos M.; Mullen C.; Sandoz D.; Rienstra C. M., Proton-Detected Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy of Fully Protonated Proteins at 40 kHz Magic-Angle Spinning. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129 (38), 11791–11801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andreas L. B.; Jaudzems K.; Stanek J.; Lalli D.; Bertarello A.; Le Marchand T.; Cala-De Paepe D.; Kotelovica S.; Akopjana I.; Knott B.; Wegner S.; Engelke F.; Lesage A.; Emsley L.; Tars K.; Herrmann T.; Pintacuda G., Structure of fully protonated proteins by proton-detected magic-angle spinning NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 9187–9192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McDermott A. E.; Creuzet F. J.; Kolbert A. C.; Griffin R. G., High-resolution magic-angle-spinning NMR spectra of protons in deuterated solids. J. Magn. Reson. 1992, 98, 408–413. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chevelkov V.; Rehbein K.; Diehl A.; Reif B., Ultrahigh Resolution in Proton Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy at High Levels of Deuteration. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 3878–3881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Callon M.; Luder D.; Malär A. A.; Wiegand T.; Římal V.; Lecoq L.; Böckmann A.; Samoson A.; Meier B. H., High and fast: NMR protein–proton side-chain assignments at 160 kHz and 1.2 GHz. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 10824–10834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwalbe H., Editorial: New 1.2 GHz NMR Spectrometers— New Horizons? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 10252–10253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barbet-Massin E.; Pell A. J.; Retel J. S.; Andreas L. B.; Jaudzems K.; Franks W. T.; Nieuwkoop A. J.; Hiller M.; Higman V.; Guerry P.; Bertarello A.; Knight M. J.; Felletti M.; Le Marchand T.; Kotelovica S.; Akopjana I.; Tars K.; Stoppini M.; Bellotti V.; Bolognesi M.; Ricagno S.; Chou J. J.; Griffin R. G.; Oschkinat H.; Lesage A.; Emsley L.; Herrmann T.; Pintacuda G., Rapid Proton-Detected NMR Assignment for Proteins with Fast Magic Angle Spinning. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 12489–12497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agarwal V.; Diehl A.; Skrynnikov N.; Reif B., High Resolution 1H Detected 1H,13C Correlation Spectra in MAS Solid-State NMR using Deuterated Proteins with Selective 1H,2H Isotopic Labeling of Methyl Groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128 (39), 12620–12621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahlawat S.; Mote K. R.; Lakomek N.-A.; Agarwal V., Solid-State NMR: Methods for Biological Solids. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122 (10), 9643–9737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nishiyama Y.; Hou G.; Agarwal V.; Su Y.; Ramamoorthy A., Ultrafast Magic Angle Spinning Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy: Advances in Methodology and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123 (3), 918–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samoson A., H-MAS. J. Magn. Reson. 2019, 306, 167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan E. C.-Y.; Huang S.-J.; Huang H.-C.; Sinkkonen J.; Oss A.; Org M.-L.; Samoson A.; Tai H.-C.; Chan J. C. C., Faster magic angle spinning reveals cellulose conformations in woods. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 4110–4113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Z.; Oss A.; O. M.L.; A. Samoson; M. Li; H. Tan; Y. Su; J. Yang, Selectively Enhanced 1H–1H Correlations in Proton-Detected Solid-State NMR under Ultrafast MAS Conditions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 8077–8083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akbey Ü.; Lange S.; Trent Franks W.; Linser R.; Rehbein K.; Diehl A.; van Rossum B.-J.; Reif B.; Oschkinat H., Optimum levels of exchangeable protons in perdeuterated proteins for proton detection in MAS solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J. Biomol. NMR 2010, 46, 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agarwal V.; Reif B., Residual methyl protonation in perdeuterated proteins for multi-dimensional correlation experiments in MAS solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 2008, 194, 16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Asami S.; Schmieder P.; Reif B., High Resolution 1H-Detected Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy of Protein Aliphatic Resonances: Access to Tertiary Structure Information. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 15133–15135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nand D.; Cukkemane A.; Becker S.; Baldus M., Fractional deuteration applied to biomolecular solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J. Biomol. NMR 2012, 52, 91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cala-De Paepe D.; Stanek J.; Jaudzems K.; Tars K.; Andreas L. B.; Pintacuda G., Is protein deuteration beneficial for proton detected solid-state NMR at and above 100 kHz magic-angle spinning? ssNMR 2017, 87, 126–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou D. H.; Shea J. J.; Nieuwkoop A. J.; Franks W. T.; Wylie B. J.; Mullen C.; Sandoz D.; Rienstra C. M., Solid-State Protein-Structure Determination with Proton-Detected Triple-Resonance 3D Magic-Angle-Spinning NMR Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 8380–8383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Siemer A. B., Advances in studying protein disorder with solid-state NMR. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 2020, 106, 101643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Retel J. S.; Nieuwkoop A. J.; Hiller M.; Higman V. A.; Barbet-Massin E.; Stanek J.; Andreas L. B.; Franks W. T.; van Rossum B. J.; Vinothkumar K. R.; Handel L.; de Palma G. G.; Bardiaux B.; Pintacuda G.; Emsley L.; Kühlbrandt W.; Oschkinat H., Structure of outer membrane protein G in lipid bilayers. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marchanka A.; Stanek J.; Pintacuda G.; Carlomagno T., Rapid access to RNA resonances by proton-detected solid-state NMR at >100 kHz MAS. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 8972–8975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Struppe J.; Quinn C. M.; Lu M.; Wang M.; Hou G.; Lu X.; Kraus J.; Andreas L. B.; Stanek J.; Lalli D.; Lesage A.; Pintacuda G.; Maas W.; Gronenborn A. M.; Polenova T., Expanding the horizons for structural analysis of fully protonated protein assemblies by NMR spectroscopy at MAS frequencies above 100 kHz. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 2017, 87, 117–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sarkar S.; Runge B.; Russell R. W.; Movellan K. T.; Calero D.; Zeinalilathori S.; Quinn C. M.; Lu M.; Calero G.; Gronenborn A. M.; Polenova T., Atomic-Resolution Structure of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein N-Terminal Domain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 10543–10555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roske Y.; Lindemann F.; Diehl A.; Cremer N.; Higman V. A.; Schlegel B.; Leidert M.; Driller K.; Turgay K.; Schmieder P.; Heinemann U.; Oschkinat H., TapA acts as specific chaperone in TasA filament formation by strand complementation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2217070120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wälti M. A.; Ravotti F.; Arai H.; Glabe C. G.; Wall J. S.; Böckmann A.; Güntert P.; Meier B. H.; Riek R., Atomic-resolution structure of a disease-relevant Aβ(1–42) amyloid fibril. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113 (34), E4976–E4984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Colvin M. T.; Silvers R.; Frohm B.; Su Y.; Linse S.; Griffin R. G., High Resolution Structural Characterization of Aβ42 Amyloid Fibrils by Magic Angle Spinning NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137 (23), 7509–7518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maruyoshi K.; Iuga D.; Antzutkin O. N.; Alhalaweh A.; Velaga S. P.; Brown S. P., Identifying the intermolecular hydrogen-bonding supramolecular synthons in an indomethacin–nicotinamide cocrystal by solid-state NMR. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 10844–10846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wijesekara A. V.; Venkatesh A.; Lampkin B. J.; VanVeller B.; Lubach J. W.; Nagapudi K.; Hung I.; Gor’kov P. L.; Gan Z.; Rossini A. J., Fast Acquisition of Proton-Detected HETCOR Solid-State NMR Spectra of Quadrupolar Nuclei and Rapid Measurement of NH Bond Lengths by Frequency Selective HMQC and RESPDOR Pulse Sequences. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 7881–7888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brown S. P., Applications of high-resolution 1H solid-state NMR. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 2012, 41, 1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Damron J. T.; Kersten K. M.; Pandey M. K.; Mroue K. H.; Yarava J. R.; Nishiyama Y.; Matzger A. J.; Ramamoorthy A., Electrostatic Constraints Assessed by 1H MAS NMR Illuminate Differences in Crystalline Polymorphs. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 4253–4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hirsh D. A.; Wijesekara A. V.; Carnahan S. L.; Hung I.; Lubach J. W.; Nagapudi K.; Rossini A. J., Rapid Characterization of Formulated Pharmaceuticals Using Fast MAS 1H Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16 (7), 3121–3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cordova M.; Moutzouri P.; Simões de Almeida B.; Torodii D.; Emsley L., Pure Isotropic Proton NMR Spectra in Solids using Deep Learning. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202216607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lewandowski J. R.; Sass H. J.; Grzesiek S.; Blackledge M.; Emsley L., Site-Specific Measurement of Slow Motions in Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 16762–16765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lakomek N.-A.; Penzel S.; Lends A.; Cadalbert R.; Ernst M.; Meier B. H., Microsecond Dynamics in Ubiquitin Probed by Solid-State 15N NMR Spectroscopy R1ρ Relaxation Experiments under Fast MAS (60–110 kHz). Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 9425–9433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schanda P.; Ernst M., Studying dynamics by magic-angle spinning solid-state NMR spectroscopy: Principles and applications to biomolecules. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2016, 96, 1–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]