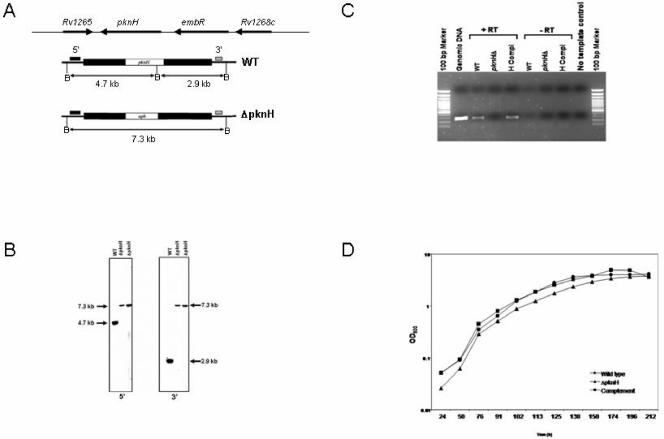

FIG. 1.

Genotype and in vitro phenotype of the M. tuberculosis ΔpknH mutant strain. (A) Structure of the M. tuberculosis pknH locus. Black bars correspond to the pknH-flanking regions that were cloned into a nonreplicating vector to make the knockout construct. Allelic exchange resulted in the replacement of pknH with a kanamycin resistance gene in the ΔpknH mutant strain. Locations of the hybridizing probes (small solid bars) and the expected sizes of the hybridizing fragments of BamHI (B) digests for each of the 5′ and 3′ Southern blots are indicated. (B) Southern blot analysis. Blots of BamHI-digested genomic DNAs from the wild type and two ΔpknH mutant isolates were hybridized to 5′ and 3′ DNA probes. The sizes of the hybridizing fragments determined from the migration distances of the molecular size markers confirmed the genomic context expected for the ΔpknH strain. (C) RT-PCR analysis. A 278-bp PCR product corresponding to an internal fragment of the pknH gene was amplified by PCR from the cDNAs of the parental wild-type strain (WT) and the complemented strain (H comp) but not from the ΔpknH mutant and the negative control reactions. Expression of the housekeeping gene sigA was found in all three strains, indicating that the lack of pknH expression in the ΔpknH strain was not due to degradation of the isolated RNA sample (data not shown). (D) pknH deletion did not affect in vitro growth of M. tuberculosis. Growth of the wild type (•), the ΔpknH mutant (▴), and the complemented strain (▪) was monitored in Dubos broth cultures. Similar growth patterns were observed during incubation in 7H9 with OADC and Proskauer and Beck medium supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80 (not shown).