Abstract

This study investigates the fabrication and optimization of mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) composed of NH2-MIL-125(Ti), a metal–organic framework (MOF), dispersed within a polysulfone (PSf) polymer matrix, for efficient CO2/CH4 separation. The MMMs were prepared by using a solution casting method, and their morphology and gas separation performance were systematically characterized. The effect of MOF addition into the polymer matrix, gas permeability, and selectivity were evaluated using a gas permeation setup. Results indicate that incorporating NH2-MIL-125(Ti) nanoparticles enhances the selectivity of the membranes for CO2 over CH4 compared to pure polymer membranes while maintaining acceptable permeability. The membrane morphology demonstrates the uniform distribution of the filler in the polymer matrix. The PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti)-15% membrane showed exceptional CO2 permeability and selectivity performance. Specifically, it achieved a CO2 permeability of 19.17 Barrer. Additionally, it exhibited a CO2/CH4 selectivity of 31.95, indicating its ability to effectively differentiate between the CO2 and CH4 gases, which is critical for applications such as natural gas purification and carbon capture. Furthermore, the MMMs produced in this study showed outstanding resistance to CO2 plasticization. The PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti)-15% membrane demonstrated superior pressure resistance, withstanding up to 14 bar without significant performance degradation compared to the pristine PSf membrane, which succumbed to plasticization at 4 bar. The enhanced plasticization resistance is attributed to incorporation of NH2-MIL-125(Ti) into the PSf matrix. The combination of high CO2 permeability, excellent selectivity, and robust plasticization resistance positions the PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti)-15% membrane as a highly effective solution for CO2 separation applications. The results underscore the potential of these MMMs to achieve significantly better performance metrics than traditional PSf membranes, making them a promising option for industrial gas separation processes.

1. Introduction

Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from anthropogenic activities have become a pressing global concern due to their significant contribution to climate change and environmental degradation.1,2 Efforts to mitigate CO2 emissions often involve the development of efficient separation technologies for capturing CO2 from gas streams, particularly in applications such as natural gas processing and carbon capture and storage (CCS) systems.3,4 Among various separation techniques, membrane-based gas separation has emerged as a promising approach due to its energy efficiency, scalability, and relatively low environmental impact.4,5 In this context, mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) combining inorganic fillers with polymeric matrices offer unique advantages for enhancing gas separation performance by leveraging the synergistic effects of both components.6−8

Membrane-based gas separation has garnered increasing attention for its potential to address the challenges associated with CO2/CH4 separation, a crucial step in natural gas purification and CO2 capture processes.8,9 While exhibiting good permeability, traditional polymeric membranes often suffer from insufficient selectivity, particularly for separating CO2 from CH4, owing to their similar sizes and physical properties.10,11 To overcome this limitation, researchers have explored integrating functionalized inorganic materials, such as metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), into polymeric matrices to create MMMs with enhanced gas separation performance.12,13

NH2-MIL-125(Ti), a type of MOF known for its tunable pore structure and high CO2 adsorption capacity, has emerged as a promising filler material for MMMs aimed at CO2/CH4 separation.14 The amino-functionalized NH2-MIL-125(Ti) offers an enhanced affinity for CO2 molecules, thereby promoting selective CO2 capture while allowing CH4 molecules to pass through the membrane more freely. Polysulfone (PSf), a widely used polymeric matrix in membrane fabrication, provides mechanical strength and compatibility with NH2-MIL-125(Ti), facilitating the formation of well-dispersed MMMs.15,16

Several studies have reported the successful fabrication and characterization of PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti) MMMs for CO2/CH4 separation. These membranes have demonstrated improved selectivity for CO2 over CH4 compared to pure polymer membranes, which is attributed to the synergistic interactions between NH2-MIL-125(Ti) nanoparticles and the polymer matrix. Additionally, researchers have investigated the influence of various factors, including filler loading, polymer concentration, membrane thickness, and fabrication methods, on the gas separation performance of PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti) MMMs.14,17−20 Optimization of these parameters has enhanced membrane selectivity and permeability further, paving the way for practical applications in gas separation processes.21,22 Despite significant progress, challenges in developing MMMs include achieving long-term stability, scalability, and cost-effectiveness.6,23 Addressing these challenges requires continued research efforts to optimize membrane fabrication techniques, understand structure–property relationships, and explore novel materials and engineering strategies.

This study aims to fabricate PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti) MMMs tailored for efficient CO2/CH4 separation. Specifically, the research targets optimization of the composition and morphology of the MMMs and characterization of their structural and surface properties. Additionally, the study seeks to evaluate the permeability and selectivity of PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti) MMMs. By achieving these objectives, the research aims to advance the development of cost-effective and energy-efficient membranes for CO2/CH4 separation with potential applications in natural gas purification and carbon capture processes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fabrication of Mixed Matrix Membranes

A solution blending method was used to fabricate MMMs with different loadings of NH2-MIL-125(Ti). NH2-MIL-125(Ti), a titanium-based metal–organic framework, features a well-defined porous structure with micropores approximately 0.5–1.0 nm in size and a high surface area ranging from 1000 to 1500 m2/g. These properties contribute to its excellent adsorption capacity and gas separation performance, making it a suitable filler for MMMs. Initially, PSf is dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF) under continuous stirring for 18 h at room temperature (25 °C) and 65% humidity. The PSf/DMF solution was left to degas at 25 °C overnight. Next, NH2-MIL-125(Ti) particles, at a concentration of 5 wt %, were added to the DMF solvent, with the mixture being alternately stirred and sonicated. Ten wt % of the PSf/DMF solution was added to the NH2-MIL-125(Ti)/DMF mixture to prime the particles. It was followed by stirring the mixture for 30 min to ensure a homogeneous dispersion of the particles and then further sonicating it for 30 min. Following this, the remaining bulk PSf/DMF solution was combined with the primed PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti) solution, and the resulting mixture was alternately stirred and sonicated for 30 min. The mixture was then vigorously stirred for an additional 1 h at room temperature (25 °C) and 65% humidity. After thorough mixing, the solution was cast onto a leveled Petri dish, and thickness was measured using a digital screw gauge in the range of 0.31 ± 0.22 μm. Finally, the fabricated MMMs were characterized and subjected to gas permeation testing. All the experiments for the CO2 permeability and CO2/CH4 selectivity were triplicated, and average values were reported. The CO2 permeability and CO2/CH4 selectivity of the sample membrane were obtained by using eqs 1 and 2, respectively.

| 1 |

where L, A, ΔP, and Q represent the membrane’s thickness, area, pressure drop, and permeate flow rate, respectively. PCO2 and PCH4 refer to the CO2 and CH4 permeabilities of the sample membrane, measured in Barrer, respectively.

| 2 |

2.2. Membrane Characterization

2.2.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy

The morphology of the prepared membranes was thoroughly analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), specifically a Tescan Clara model from the Czech Republic. This advanced imaging technique was employed to capture detailed images of the membrane’s surface and cross-sectional structures, allowing for an in-depth examination of the membrane’s physical characteristics. Small pieces of the membrane were first immersed in liquid nitrogen to prepare the samples for the SEM examination. This step was crucial for several reasons. Immersing the samples in liquid nitrogen rapidly freezes the membrane material, making it brittle and easier to cut without deforming or damaging its intricate structure. This process ensures that the morphology of the membrane remains intact and uniform during preparation, allowing for more accurate imaging and analysis. After being frozen, the membrane pieces were carefully cut into smaller sections suitable for SEM analysis. To enhance the clarity and resolution of the SEM images, each membrane sample underwent a gold coating process. This thin layer of gold was applied to the surfaces of the samples to improve their conductivity. The gold coating helps to reduce charging effects that can occur when nonconductive samples, like polymer membranes, are exposed to the electron beam during SEM imaging. By minimizing these effects, the gold coating ensures that the resulting images are sharp and well defined, allowing for a clearer observation of the membrane’s microstructure. The SEM analysis was conducted at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV. This voltage was carefully selected to optimize the resolution and depth of field, ensuring that the fine details of the membrane’s morphology could be accurately observed. The SEM images obtained provided valuable insights into the surface features, pore structures, and overall integrity of the membranes. These images are critical for understanding how the membranes’ structural properties relate to their performance in gas separation and other applications.

2.2.2. Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy was employed to conduct a detailed compositional analysis of the materials. This powerful analytical technique was used to identify and quantify the elemental composition of both the particles and the MMMs. The EDX analysis was meticulously performed on sample images with a width of 10 μm. This scale was chosen to provide a comprehensive overview of the distribution and concentration of the elements within the sample. By focusing on a 10 μm wide area, the analysis captured fine details about the spatial arrangement and homogeneity of the elements present in the particles and the MMMs.

2.2.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

An FTIR spectrometer, PerkinElmer Spectrum One, USA, was used to identify the various functional groups in the sample using the KBr method. The samples were prepared for analysis by finely grinding a small amount (typically 1–2 mg) of the solid sample with a much larger amount (approximately 100 mg) of a dry, spectral-grade KBr powder. This mixture was homogenized to ensure an even sample distribution within the KBr matrix. The ground mixture was then placed in a die and subjected to high pressure in a hydraulic press to form a transparent pellet. This pellet must be clear and free of cracks to provide accurate results. The analysis was performed in transmittance mode, covering a spectral range from 400 to 4000 cm–1. The FTIR spectrometer then collected the interferogram data, which were mathematically transformed into a spectrum using the Fourier transform algorithm. The resulting spectrum displayed absorption peaks corresponding to the molecular bonds. Baseline corrections were applied to remove artifacts, and the peaks were analyzed against reference databases for identification. Quantitative analysis involves measuring peak areas or heights to determine the concentrations of specific components.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. SEM Analysis

The SEM images (top and cross-section view) of the synthesized membranes can be seen in Figure 1. Figure 1a,b shows the top and cross-section view SEM images of the PSf membrane, which exhibits a consistent and smooth surface structure. In contrast, Figure 1c–j presents the top and cross-sectional view SEM images of PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti) MMMs with varying concentrations of filler. The particles on the MMMs increase as the filler loading in the polymer matrix ranges from 5% to 20%. SEM analysis reveals minimal voids, potentially because of the amine functional group. These functional groups enhance the interaction between the PSf polymer matrix through hydrogen bonding.

Figure 1.

SEM images: (a) top and (b) cross section of the pristine PSf membrane, (c) top and (d) cross section of PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti)-5% MMM, (e) top and (f) cross section of PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti)-10% MMM, (g) top and (h) cross section of PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti)-15% MMM, (i) top and (j) cross section of PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti)-20% MMM, and (k) schematic diagram of gas permeation through MMMs.

The SEM images of the filler show that the increase in the NH2-MIL-125(Ti) concentration results in enhancement of the filler at the membrane surface and cross-section. As the NH2-MIL-125(Ti) concentration in MMMs exceeded 15% to reach 20%, agglomeration of filler particles becomes apparent on the surface of the membrane, as illustrated in the top-view SEM images (Figure 1i). Additionally, a cluster of particles is observed in the cross-sectional images in Figure 1j. This may result from an excessive concentration of particles within the PSf matrix. Conversely, the membranes with 5–15% particle loading do not show notable agglomeration, indicating a more even distribution of particles. Adding a filler into the polymer matrix improves the surface morphology of the membrane; the filler addition results in higher gas transportation and enhanced separation performance.

Figure 1k illustrates the potential gas transport mechanism through the membrane, providing a visual explanation of how the membrane facilitates gas separation. As depicted in the figure, the interaction between the amine functional groups and the CO2 molecules plays a critical function in enhancing the CO2 transport. The amine groups have a high affinity for CO2, which advocates for the selective absorption and subsequent diffusion of CO2 gas.

As a result, the reduction of nonselective voids in the MMMs leads to enhanced gas pair selectivity. This means that the membrane can more effectively differentiate between CO2 and other gases, such as CH4, ensuring that CO2 is preferentially transported, while other gases are retained or rejected. The combined effects of improved compatibility and selective interaction with CO2 contribute to the superior performance of the MMMs in gas separation applications.

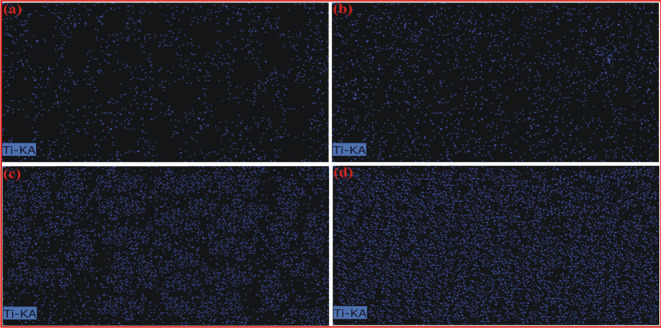

3.2. EDX Analysis

Figure 2 displays the EDX mapping data for the prepared MMMs. The sequential blue points indicate the titanium (Ti) level within the membranes. The filler structure consists of Ti–O units and 2-amino terephthalic acid linkers in a framework, making Ti a primary component in the MMMs. Figure 2 also reveals that as the filler particle content in the polymer phase increases so does the Ti concentration in the MMMs. Additionally, filler particles are closely packed within PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti)-20% MMM.

Figure 2.

EDX analysis of resultant MMMs: (a) PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti)-5% MMM, (b) PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti)-10% MMM, (c) PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti)-15% MMM, and (d) PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti)-20% MMM.

3.3. FTIR Analysis

Figure 3 shows the FTIR spectra of resultant membranes and filler powder. The 1442 and 1554 cm–1 wavenumbers exhibit absorption, signifying aromatic C=C bonding within the PSf. For C=C bonds, the characteristic of the PSf polymer indicates the stretching vibrations of these double bonds. O=S=O shows the presence of sulfone groups, identified by strong polarity, and displays distinct absorption bands for asymmetric and symmetric stretching around 1128 cm–1. The C–O–C bond at 1220 cm–1 indicates the presence of an ether group. Absorptions observed at 1280 cm–1 suggest vibrational activity within the sulfone group. The prominent absorption at 1034 cm–1 is linked to Si–O bonding within the PSf.

Figure 3.

FTIR analysis of pristine, resultant MMMs, and NH2-MIL-125(Ti) powder.

The broad peaks observed at 3457 and 3331 cm–1 in the spectrum are attributed to the stretching vibrations of the hydroxyl (O–H) group and the presence of the amine (−NH2) group, respectively. These peaks indicate functional groups associated with the fillers used in the membrane. The peaks at 1661 and 1098 cm–1 are indicative of the carbonyl (C=O) and ester (O–C–O) bonds, respectively, which are key components of the filler material.

Additionally, the peaks at 1259 and 1662 cm–1 correspond to the aromatic amine C–N and N–H bonds, further confirming the presence of these groups in the filler. The peaks observed at 1440 and 1540 cm–1 are associated with the deformation of methylene (CH2) groups and the symmetric stretching of carboxylate groups, respectively. These peaks provide insight into the structural features and bonding environment within the filler material.

The peak at 659 cm–1 represents the stretching vibration of the C–OH bond, highlighting the presence of hydroxyl groups in the filler. Figure 3 also reveals that the spectra of the membrane display characteristic peaks of both the polymer and the filler. This observation indicates the successful incorporation of the filler into the PSf membrane matrix.

The presence of these characteristic peaks in the FTIR spectra confirms the inclusion of the filler material within the PSf membrane. This finding corroborates the results obtained from SEM, which also suggested a successful integration. The combined evidence from SEM and FTIR spectra provides a comprehensive understanding of the structural composition and the successful fabrication of the MMMs.

3.4. Gas Separation Performance

The results of the single gas permeation tests for PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti) MMMs are presented in Figure 4. CO2 and CH4 were tested using different membranes prepared with varying filler concentrations. The pristine PSf membrane exhibits CO2 and CH4 permeabilities of 6.1 and 0.7 Barrer, respectively. Figure 4a illustrates that the CO2 gas permeabilities are higher than those of CH4. This tendency is ascribed to the varying solubility of these gases within the PSf. Figure 4b shows that the pristine PSf membrane achieves an ideal selectivity of 8.7 for the CO2/CH4 gas pair.

Figure 4.

Effect of filler loading on gas (a) permeability and (b) selectivity.

The CO2/CH4 ideal selectivity of the pristine PSf membrane fabricated with the DMF solvent is higher than that of PSf membranes made with other solvents. This enhancement is primarily due to the DMF solvent’s higher molar volume, thereby improving its interaction with the gases. As a result, the PSf membrane produced using DMF solvent demonstrates superior separation performance compared to the pristine PSf membranes created using other solvents, as reported in the literature.

The observed selectivity trend can be attributed to the differential diffusion rates and affinities of CH4 and CO2 within the polymer matrix. CH4 exhibits a lower diffusion rate through the polymer due to its larger molecular size and lower kinetic energy than that of CO2. Additionally, CH4 has a lower affinity for the Langmuir sorption sites within the polymer matrix, which are more favorable for CO2 due to its smaller size and higher polarity. Consequently, CO2 is preferentially adsorbed and diffused through the polymer, enhancing the overall selectivity of the membrane toward CO2 over CH4. This explains the trend where CO2 permeates more readily, while CH4 experiences greater resistance, contributing to the observed selectivity in gas separation performance.

The PSf membrane prepared using filler exhibits CO2 permeabilities ranging from 10.7 to 19.1 Barrer as the filler concentration increased from 5% to 20%, as shown in Figure 4a. These MMMs also show an ideal CO2/CH4 selectivity between 11.9 and 31.9. The MMMs achieve significantly higher permeabilities and selectivity than the pristine PSf membrane. The PSf membrane prepared with 5% filler displays a 10.7 Barrer CO2 permeability, representing a 76.1% increase over the pristine PSf membrane. Additionally, the selectivity of the same membrane is enhanced by 36.8%. This marked a significant improvement in the permeability and selectivity by adding the filler.

The PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti)-10% results in a 14.2 Barrer permeability and a 16.2 selectivity. Comparatively, the PSf membrane prepared with 10% filler shows a remarkable improvement with a 132.8% and 86.2% rise in permeability and selectivity, respectively, over the pristine PSf membrane. The PSf membrane prepared with 15% filler displays the highest permeability of 19.1 Barrer and a selectivity of 31.9. This significant enhancement in separation performance is attributed to incorporation of the filler into the PSf.

Enhancing the filler beyond 15 wt % in the polymer results in diminished separation performance, as demonstrated by the performance of the 20 wt % membrane. In particular, this membrane shows a noticeable decrease in permeability and selectivity. This decline in performance is attributed to agglomeration of the filler. When fillers aggregate, they form clusters that disrupt the uniform distribution of the material, leading to the creation of nonselective voids. These voids, which are visible in SEM images, compromise the membrane’s ability to effectively separate CO2 from CH4.

Agglomeration is a common issue when high amounts of fillers are incorporated into polymer matrices. Instead of forming a well-dispersed composite, the filler particles tend to stick together, creating irregularities in the structure. These irregularities act as pathways that allow gases to pass through indiscriminately, thereby reducing the selectivity and permeability of the membrane. This phenomenon explains why the 20 wt % membrane performs poorly compared to membranes with lower filler content.

It has been determined that the optimal loading of the filler for fabricating an effective membrane for separation is 15 wt %. At this specific loading, the membrane exhibits the highest CO2 permeability and the best CO2/CH4 ideal selectivity. This optimal balance is crucial for achieving efficient gas separation as it maximizes the desired gas flow while minimizing the passage of unwanted gases. Thus, the 15 wt % membrane represents the most effective composition for the targeted separation process, providing superior performance compared to membranes with higher filler contents.

3.5. CO2-Induced Plasticization Effect

The plasticization resistance of the PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti) MMM and the pristine PS membrane is shown in Figure 5. The CO2 permeability of the PSf membrane dropped progressively with the rise in feed pressure until it reached a pressure of 4 Barrer. The lowest CO2 permeability at 6 Barrer represents its plasticization pressure threshold. This behavior is consistent with the reported resistance to plasticizing pristine PSf membranes in the existing literature.

Figure 5.

Effect of pressure on the CO2 permeability for the study of plasticization.

The PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti) MMM shows CO2 plasticization resistance at a considerably higher feed pressure of 14 bar, thus increasing the threshold in pure PSf membranes. The filler, which increases the CO2 permeability, is probably responsible for the enhanced resistance. Until the feed pressure reaches 14 bar, the CO2 permeability of the MMM seems to indicate a significant correlation between the adsorbed CO2 and amine groups. With increasing feed pressures, there is evidence that facilitated diffusion may be involved due to the interaction between CO2 molecules and amine groups. When the feed pressure exceeds 14 bar, a drop-off in CO2 permeability is apparent, going on up to 16 bar. The enhanced plasticization performance proves the significant interactions between the filler and polymer.

3.6. Comparison with the Robson Upper Bound Relationship

Figure 6 compares the membrane separation that was attained in this study and previously reported for MMMs of PSf during the separation of CO2/CH4 relative to Robeson’s upper bound relationship. Regarding the PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti) MMMs produced in the current research, the CO2/CH4 separation potential is below Robeson’s highest limits, as other authors who have worked with PSf-containing MMMs claimed. Still, they have not gone beyond this standard either. This comparative analysis reveals that incorporating the filler has enhanced the gas separation performance. Singh et al.24 conducted research on the PSf/PEG-g-CNT for CO2 separation. The results indicate that a CO2/CH4 selectivity of 10.2 was achieved at a 2.5 bar pressure and 5% PEG-g-CNT. The addition of the filler to the PSf polymer results in higher stability and an economical and commercially available membrane for CO2 separation. Kiadehi et al.25 conducted research on PSf/CNF for CO2 separation and found that a CO2/CH4 selectivity of 12.1 was achieved at a pressure of 4 bar with 5% PEG-g-CNT. They also achieved a CO2 permeability of 12.04 Barrer with the addition of nanoparticles increasing from 2.134 compared to the pristine PSf membrane.

Figure 6.

Robeson upper bound comparison with PSf membranes reported in the literature.

However, to facilitate the practical implementation of these membranes in industrial settings, further efforts should be directed toward optimizing their properties. This includes enhancing the long-term stability of the membranes to ensure that they can withstand prolonged operational conditions. Additionally, conducting technoeconomic assessments will be crucial to evaluate the cost-effectiveness and scalability of these membranes, ensuring that they can be feasibly integrated into existing industrial processes. By addressing these aspects, PSf/NH2-MIL-125(Ti) MMMs could become a key component in the future of sustainable gas separation technologies.

4. Conclusions

The current study has highlighted the significant potential of MMMs for achieving efficient CO2 separation, a crucial process in applications such as natural gas purification and carbon capture. Incorporating an MOF into the membrane increased gas separation performance. The findings reveal that the synergy between the NH2-MIL-125(Ti) filler and the PSf polymer matrix not only improves the membrane’s selectivity but also maintains a high level of permeability, which is essential for practical separation processes. The addition of a filler into the membrane results in the highest permeability and selectivity. The addition of the filler into the membrane showed that 15% results in the highest permeability and selectivity values of 19.17 Barrer and 31.95%, respectively. These values represent a significant improvement over membranes without the MOF filler, highlighting the effectiveness of the filler in enhancing gas separation performance. Furthermore, the research included a plasticization study, which tested the membrane’s stability under varying pressures. The results showed that the membrane maintained a stable performance up to a pressure of 14 bar. This is a notable improvement compared to the pristine membrane, which remains stable only up to 6 bar. The enhanced plasticization resistance is a critical factor for industrial applications, where membranes are often exposed to high-pressure conditions. This stability ensures that the membrane can continue to function effectively without degradation or loss of performance, making it a more reliable option for long-term use.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the University of Jeddah, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, under grant No. UJ-23-SRP-12. The authors thank the University of Jeddah for its technical and financial support.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Anwar M. N.; Iftikhar M.; Bakhat B. K.; Sohail N. F.; Baqar M.; Yasir A.; Nizami A. S.. Sources of carbon dioxide and environmental Issues. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 37; Inamuddin, Asiri A., Lichtfouse E., Eds.; Sustainable Agriculture Reviews; Springer, 2019; Vol. 37, pp 13–36. 10.1007/978-3-030-29298-0_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon S.; Plattner G.-K.; Knutti R.; Friedlingstein P. Irreversible climate change due to carbon dioxide emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 1704–1709. 10.1073/pnas.0812721106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains P.; Psarras P.; Wilcox J. CO2 capture from the industry sector. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2017, 63, 146–172. 10.1016/j.pecs.2017.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gür T. M. Carbon dioxide emissions, capture, storage and utilization: Review of materials, processes and technologies. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2022, 89, 100965. 10.1016/j.pecs.2021.100965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanim A. A. J.; Waqas S.; Zeeshan M. H.; Khan J. A.; Ghalib S. A.; Irfan M.; Rahman S.; Faraj Mursal S. N.; Jalalah M.; Almawgani A. H. M. Nanofiltration PVP Membrane with Gradient Cross-Linking for Efficient Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Removal. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 5265–5272. 10.1021/acsomega.3c05712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z.; Yuan Z.; Dai Z.; Shao L.; Eisen M. S.; He X. A review from material functionalization to process feasibility on advanced mixed matrix membranes for gas separations. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 475, 146075. 10.1016/j.cej.2023.146075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z.; Ma Y.; Wei J.; Guo H.; Wang B.; Deng J.; Yi C.; Li N.; Yi S.; Deng Y.; et al. Recent progress in ternary mixed matrix membranes for CO2 separation. Green Energy Environ. 2024, 9, 831–858. 10.1016/j.gee.2023.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pazani F.; Maleh M. S.; Shariatifar M.; Jalaly M.; Sadrzadeh M.; Rezakazemi M. Engineered graphene-based mixed matrix membranes to boost CO2 separation performance: Latest developments and future prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 160, 112294. 10.1016/j.rser.2022.112294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kadirkhan F.; Goh P. S.; Ismail A. F.; Wan Mustapa W. N. F.; Halim M. H. M.; Soh W. K.; Yeo S. Y. Recent advances of polymeric membranes in tackling plasticization and aging for practical industrial CO2/CH4 applications—a review. Membranes 2022, 12, 71. 10.3390/membranes12010071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Sunarso J.; Liu S.; Wang R. Current status and development of membranes for CO2/CH4 separation: A review. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 2013, 12, 84–107. 10.1016/j.ijggc.2012.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y.; Ho W. W. Polymeric membranes for CO2 separation and capture. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 628, 119244. 10.1016/j.memsci.2021.119244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goh P.; Ismail A.; Sanip S.; Ng B.; Aziz M. Recent advances of inorganic fillers in mixed matrix membrane for gas separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2011, 81, 243–264. 10.1016/j.seppur.2011.07.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goh S. H.; Lau H. S.; Yong W. F. Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)-based mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) for gas separation: a review on advanced materials in harsh environmental applications. Small 2022, 18, 2107536. 10.1002/smll.202107536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winarta J.; Meshram A.; Zhu F.; Li R.; Jafar H.; Parmar K.; Liu J.; Mu B. Metal–organic framework-based mixed-matrix membranes for gas separation: an overview. J. Polym. Sci. 2020, 58, 2518–2546. 10.1002/pol.20200122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadijokani F.; Ghaffarkhah A.; Molavi H.; Dutta S.; Lu Y.; Wuttke S.; Kamkar M.; Rojas O. J.; Arjmand M. COF and MOF hybrids: Advanced materials for wastewater treatment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 34, 2305527. 10.1002/adfm.202305527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi P.; Saroha M.; Malik R. S.. MOF: A Heterogeneous Platform for CO2 Capture and Catalysis. In Metal– Organic Frameworks for Carbon Capture and Energy; ACS Publications, 2021; pp 315–354. [Google Scholar]

- Alami A. H.; Hawili A. A.; Tawalbeh M.; Hasan R.; Al Mahmoud L.; Chibib S.; Mahmood A.; Aokal K.; Rattanapanya P. Materials and logistics for carbon dioxide capture, storage and utilization. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 137221. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C.; Hussain W.; Alkaaby H. H. C.; Al-Khafaji R. M.; Alghazali T.; Izzat S. E.; Shams M. A.; Abood E. S.; Yu A. E.; Ehab M. Polymeric nanocomposite membranes for gas separation: Performance, applications, restrictions and future perspectives. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 38, 102323. 10.1016/j.csite.2022.102323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar S.; Smitha B.; Aminabhavi T. Separation of carbon dioxide from natural gas mixtures through polymeric membranes—a review. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2007, 36, 113–174. 10.1080/15422110601165967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.; Song C.; Guo X.; Hong S.; Choi J.; Liu Y. Microstructural optimization of NH2-MIL-125 membranes with superior H2/CO2 separation performance by innovating metal sources and heating modes. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 616, 118615. 10.1016/j.memsci.2020.118615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lau C. H.; Li P.; Li F.; Chung T.-S.; Paul D. R. Reverse-selective polymeric membranes for gas separations. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013, 38, 740–766. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2012.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes S. P.; Culfaz-Emecen P. Z.; Ramon G. Z.; Visser T.; Koops G. H.; Jin W.; Ulbricht M. Thinking the future of membranes: Perspectives for advanced and new membrane materials and manufacturing processes. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 598, 117761. 10.1016/j.memsci.2019.117761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.; Zhang F.; Lively R. P.. Manufacturing nanoporous materials for energy-efficient separations: Application and challenges. In Sustainable Nanoscale Engineering; Elsevier, 2020; pp 33–81. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S.; Varghese A. M.; Reddy K. S. K.; Romanos G. E.; Karanikolos G. N. Polysulfone mixed-matrix membranes comprising poly (ethylene glycol)-grafted carbon nanotubes: mechanical properties and CO2 separation performance. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 11289–11308. 10.1021/acs.iecr.1c02040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiadehi A. D.; Rahimpour A.; Jahanshahi M.; Ghoreyshi A. A. Novel carbon nano-fibers (CNF)/polysulfone (PSf) mixed matrix membranes for gas separation. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 22, 199–207. 10.1016/j.jiec.2014.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]