Abstract

One of the purposes of tissue engineering is to offer therapeutic alternatives to treat various esophagus-related diseases. To develop viable esophageal replacements that are both mechanically and biologically compatible and to assess the impact of pharmacological treatments on esophageal tissue at the macro- and micro-structural levels, it is crucial to understand the biomechanical properties of the esophagus. In this study, we analyzed esophageal tissue samples from nine newborn lambs. Subjects were randomly separated into a control group (n = 5) and a melatonin-treated group (n = 4). The passive mechanical response of the esophagus was studied by performing in-vitro uniaxial tensile tests along longitudinal and circumferential directions. Samples were classified into three types: internal tissue (mucosa and submucosa layers), external tissue (external muscular layer), and integrated tissue (comprising all layers). Uniaxial stress versus stretch curves of each classification were used to determine mechanical properties that were statistically analyzed. Moreover, average experimental results were used to calibrate an anisotropic hyperelastic model. Stress-stretch curves from uniaxial tests showed a highly anisotropic behavior, with a higher stiffness along the longitudinal direction and internal tissue exhibiting the highest stiffness. To contrast the results obtained from mechanical testing, histological analysis of esophagus samples was carried out. Microstructural components were quantified and morphological measurements of the main zones were performed. No significant differences were found at the macro- and microstructural levels of the tissue, indicating that the supply of low doses of melatonin does not alter the biomechanical properties of the esophagus.

Keywords: Biomechanical properties, Esophagus, Uniaxial tensile test, Melatonin

Subject terms: Oesophagus, Biomedical engineering, Tissues

Introduction

The esophagus is a digestive tract tube connecting the pharynx to the stomach. Its primary function is to facilitate the movement of food bolus through involuntary muscular contractions (peristalsis)1. The histological morphology of the esophageal wall consists of four main layers. The innermost layer is called mucosa, followed by submucosa and muscularis layers, and the outermost layer is called adventitia2. The structural composition of esophageal tissue predominantly consists of two fibrous proteins with a complex hierarchical nature, elastin and collagen. Resembling a composite material, the esophageal wall comprises an elastin matrix providing elastic distensibility, and reinforcing collagen-fiber bundles offering stiffness and mechanical strength.

In its in-vivo, intact state, the esophagus is mildly stretched along its longitudinal direction. Besides, it exhibits residual stresses along the circumferential direction, attributed to the growth and remodeling of esophageal tissue3,4. Understanding the mechanical behavior of the esophagus and its biomechanical properties holds significant importance in medicine. This is particularly relevant due to various esophagus diseases, which may necessitate surgical interventions involving sutures and eventually tissue replacement5–7. However, these techniques can often lead to tissue deterioration, complicating issues such as stenosis and other problems6,7. This motivates the study of biomechanical properties to evaluate the changes from pathologies and the administration of drugs to treat certain esophagus-related disorders.

In this context, tissue engineering emerges as a promising discipline for the development of therapeutic alternatives to address esophageal disorders, focusing on exploring adequate substitutes to replace the esophageal duct, with an emphasis on ensuring both biological compatibility and appropriate biomechanical behavior of the employed materials.

Previous studies have used various ex-vivo techniques to analyze the behavior of the esophagus of different animals and to quantify the biomechanical properties of this tissue. Histology performed on rat esophagus samples suggested analyzing the tissue from a mechanical point of view as a multilayered anisotropic composite-type material8. In triaxial tensile tests, the mucosa-submucosa layer was significantly stiffer than the muscularis layer along the longitudinal, circumferential, and diagonal directions (45° with respect to the longitudinal direction)8,9. Uniaxial tensile tests on pig esophagus reported a significantly higher strength in the mucosa-submucosa layer than the muscularis layer, about five times stronger along the longitudinal direction and three times stronger in the circumferential direction10. The esophagus was also divided into cervical, abdominal, and thoracic regions,with the mucosa-submucosa layer along the longitudinal direction in the cervical region showing the highest distensibility10. Friction tests determined that the thoracic region presented a significantly lower coefficient compared to the other two remaining regions11. Different mechanical tests have been applied to the lamb esophagus to analyze their behavior. The mucosa-submucosa and muscular layers presented a nonlinear and anisotropic behavior in uniaxial tension and a higher tensile strength of the mucosa-submucosa layer compared to the muscular layer9. In biaxial tensile tests, a nonlinear behavior with pronounced anisotropy at high strains and different properties along longitudinal and circumferential directions is reported for intact esophageal tissue12,13. In histological analyses performed after subjecting samples to uniaxial tests, tissue damage was observed at stretches above 1.25-1.35, and rupture of muscle fibers and capillaries was seen at stretches above 1.3, with no evidence of damage in the mucosa-submucosa area at a similar strain level14. Pressurization tests applied to lamb and pig esophagus showed that the mucosa-submucosa layer is stiffer than the muscularis layer12,15. In rabbit esophagus, a significant increase of the radius in the muscular layer was found for pressures between zero and 1.33 kPa16. Circumferential residual stress of both the intact esophagus and individual layers has been quantified using ring-opening tests. It has been reported that, in different species, the mucosa-submucosa layer presents on average a greater opening angle than the muscular layer and the intact esophagus4,12,16,17.

Mechanical characterization of soft biological tissues usually implies calibrating constitutive models to experimental data. The goal is to find a set of material parameters that minimize the error between the experimental data and the (theoretical) constitutive model response, for which several curve-fitting methods have been proposed to optimize an objective function resembling a least-squares problem. Some methods – such as gradient-based Levenberg-Marquardt18 and stencil-based Nelder-Mead19 algorithms – require a set of initial values for material parameters that strongly influence convergence. In contrast, other metaheuristic optimization techniques (e.g. evolutive strategies) only require setting bounds for the search space20–22. Different hyperelastic models have been proven useful at describing the multi-layer anisotropy of esophageal tissue9,23–25. Furthermore, mechanical characterization of healthy esophagus17,26,27 has been performed, however, an assessment of the effect of pharmaceutical treatments on esophagus biomechanics has not yet been achieved.

Therefore, this study aims to characterize the passive biomechanical response of esophageal tissue from newborn lambs and to evaluate changes in its mechanical properties resulting from melatonin administration. The importance of melatonin and its benefits are widely reported. For example, it has demonstrated beneficial effects on the cardiovascular system due to its antioxidant and vasodilatory properties28,29. Furthermore, many other organs, including the gastrointestinal tract, are known to contain melatonin receptors and produce melatonin30, which has been associated with the reduction of lesions as well as the protection of esophageal tissue against gastric reflux and esophagitis30–33.

However, no prior research has investigated possible alterations in the ex-vivo passive mechanical properties of esophageal tissue resulting from melatonin administration. The mechanical response of a melatonin-treated group of lambs is contrasted with that of a control group. The study is based on uniaxial tension tests applied to esophagus samples classified as internal tissue (designated “Int”, comprising mucosa and submucosa layers), external tissue (designated “Ext”, comprising external muscular layer) or integrated tissue (designated “IT”, comprising all esophageal layers). In addition, histological analysis of esophagus samples is performed using Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) and Elastic Van Gieson (EVG) staining techniques to evaluate microstructural changes in the tissues. The classifications of biological material tested, description of experimental procedures, and geometric measurements are described in Section "Materials and methods". Section "Results and discussion" shows the experimental results and the constitutive model calibration along with a discussion comparing the biomechanical properties determined with results from previous works, as well as the histological analysis of extracted samples. Section "Conclusions" presents the main contributions and conclusions of the study.

Materials and methods

Materials

We procured the esophagus of nine newborn lambs (Ovis aries) born and raised at the International Center for Andean Studies (INCAS) located in Putre, Chile, located at 3600 meters above mean sea level (masl) (Fig. 1). The lambs were randomly separated into two groups:

Control group (NC): five unmedicated lambs (NC,

), thirty days old at the time of euthanasia.

), thirty days old at the time of euthanasia.Melatonin group (MN): four lambs administered melatonin (MN,

, 1 mg/kg of melatonin in ethanol 1.4% 0.5 mL/kg per day), thirty days old at the time of euthanasia.

, 1 mg/kg of melatonin in ethanol 1.4% 0.5 mL/kg per day), thirty days old at the time of euthanasia.

The animals treated with melatonin were part of a larger study designed to assess its vasodilatory and antioxidant effects.

Fig. 1.

Preparation of lamb esophagus specimen for uniaxial tensile testing: (a) lamb esophagus prepared for specimen extraction; (b) integrated tissue (IT) specimen mounted on tensile testing machine.

Melatonin was administered orally for 21 days starting on the third day of age and at dusk to follow the circadian rhythm of endogenous melatonin release34. Euthanasia was performed by intravenous injection of sodium thiopental at a dose of 100 mg per kilogram of body weight. The tissue samples, classified as internal (Int), external (Ext) or integrated tissue (IT), are listed in Table 1. Samples are further categorized as either longitudinal (Long.) or circumferential (Circ.), according to the orientation of its main (loading) axis against the longitudinal axis of the corresponding intact esophagus (Table 1). The separation of tissues was performed manually under a microscope, using a precision bistoury and tweezers in order to prevent any tissue damage that could alter its mechanical behavior. During the procedure, the samples were placed on a plate and immersed in physiological serum (Krebs) at  C to preserve the integrity and conditions of the tissue. This protocol is based on methods previously validated with other biological tissues21,34.

C to preserve the integrity and conditions of the tissue. This protocol is based on methods previously validated with other biological tissues21,34.

Table 1.

Classification of specimens included in the study, control (CN) and melatonin-treated (MN) groups.

| Tissue | Orientation | CN | MN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Int | Long. | 3 | 2 |

| Circ. | 3 | 2 | |

| Ext | Long. | 4 | 3 |

| Circ. | 2 | 3 | |

| IT | Long. | 3 | 4 |

| Circ. | 4 | 4 |

Internal (Int), external (Ext), and integrated tissue (IT) samples along longitudinal (long.) and circumferential directions (circ.).

Animal care, maintenance, and procedures were approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Chile (certificate CBA 761), and were performed following the International Standards for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health of the United States (NIH No.85-23, revised 1996) and the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Uniaxial tensile tests

The uniaxial-tensile test is a widely used experiment for the characterization of materials, since it allows the measurement of their unidirectional stress-strain response and evaluation of their mechanical properties. The test involves subjecting a material sample to a state of homogeneous deformation under a uniform tensile load applied along a specific direction of interest. The experimental protocol followed previously established guidelines35, with tissue samples immersed in a calcium-free Krebs physiological serum at a temperature of 39 °C during the tests to mimic physiological conditions.

The lamb esophagus specimens subjected to uniaxial tension had rectangular cross sections with average dimensions presented in Table 2 and illustrated in Fig. 2. The samples were subjected to tensile load until failure using an Instron 3342 testing machine equipped with a 10 N load cell (accuracy of  N). Tensile tests were performed at a constant displacement rate of 1.5 mm/min to achieve quasi-static (rate independent) conditions36.

N). Tensile tests were performed at a constant displacement rate of 1.5 mm/min to achieve quasi-static (rate independent) conditions36.

Table 2.

Average dimensions of specimens tested in uniaxial tension (mean ± SD), control (CN), and melatonin-treated (MN) groups.

| Tissue | CN | MN | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Thickness [mm] [mm] |

Length [mm] [mm] |

Width [mm] [mm] |

Thickness [mm] [mm] |

Length [mm] [mm] |

Width [mm] [mm] |

||

| Int | Long. | 1.33 ± 0.38 | 6.14 ± 0.17 | 8.69 ± 1.92 | 1.31 ± 0.17 | 6.31 ± 0.59 | 6.83 ± 0.44 |

| Circ. | 1.47 ± 0.24 | 6.24 ± 0.24 | 7.09 ± 0.66 | 1.43 ± 0.47 | 6.63 ± 0.28 | 5.68 ± 1.46 | |

| Ext | Long. | 2.43 ± 0.54 | 6.40 ± 0.24 | 7.24 ± 2.34 | 2.73 ± 1.40 | 6.30 ± 0.17 | 8.60 ± 1.58 |

| Circ. | 2.81 ± 0.59 | 6.56 ± 0.42 | 7.42 ± 1.24 | 2.45 ± 0.16 | 6.56 ± 0.26 | 6.20 ± 1.23 | |

| IT | Long. | 3.59 ± 0.35 | 6.16 ± 0.26 | 9.61 ± 1.44 | 3.32 ± 0.98 | 5.99 ± 0.52 | 9.48 ± 1.3 |

| Circ. | 3.96 ± 1.11 | 6.29 ± 0.10 | 11.14 ± 1.11 | 4.41 ± 1.04 | 6.16 ± 0.24 | 9.37 ± 1.84 | |

Internal (Int), external (Ext), and integrated tissue (IT) samples along longitudinal (long.) and circumferential (circ.) directions.

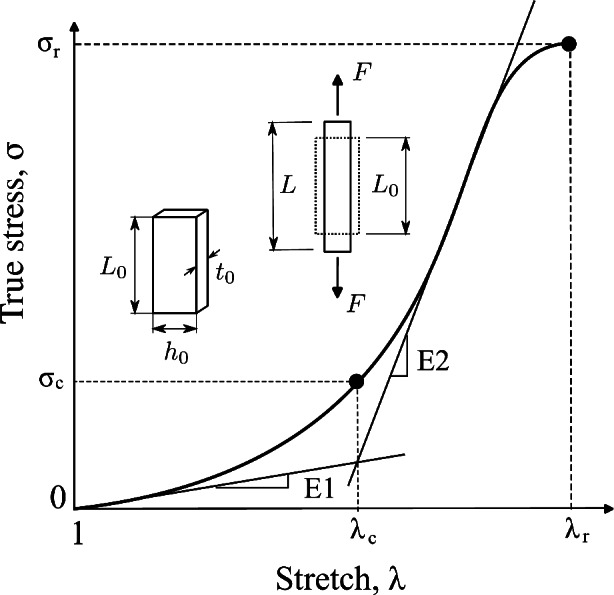

Fig. 2.

Schematic uniaxial stress-stretch curve and mechanical parameters.

To minimize sample slippage at the clamps, we used stainless steel grips in combination with a cyanoacrylate-based adhesive and mechanical compression to secure samples in the testing machine. This protocol has been shown in previous studies to be effective in preventing relative displacements between the sample and the grips21,34,36–38. Once the sample was mounted, low loads (ranging from 0.03 to 0.04 N, depending on the type of tissue) were applied to secure it in the clamps and eliminate tissue laxity. This established the initial test setup as the 0 N load condition. The test ended when the material ruptured within the working region, between the clamps, and the machine stopped recording load values.

Stretch is calculated  , where L is the instantaneous length and

, where L is the instantaneous length and  is the initial length. True (Cauchy) stress is calculated as

is the initial length. True (Cauchy) stress is calculated as  , where F is the axial force,

, where F is the axial force,  is the instantaneous area derived from the incompressibility condition and

is the instantaneous area derived from the incompressibility condition and  corresponds to the initial area of the specimen39.

corresponds to the initial area of the specimen39.

The results of uniaxial tensile tests enabled us to obtain characteristic features of stress-strain curves, facilitating the comparison of the biomechanical behavior between groups studied (CN and MN). The initial slope (E1) and the final slope (E2) of the curves, along with two stretch-stress pairs, namely the rupture point ( ,

,  ) and the knee point (

) and the knee point ( ,

,  ), were determined (see Fig. 2).

), were determined (see Fig. 2).

The rupture point was determined as the stress-stretch pair corresponding to the maximum true stress (Cauchy) before it began to decrease (see Fig. 2). The initial slope (E1) and the final slope (E2) of stress-stretch curves, determined by linear regression, serve as mechanical parameters that quantify the stiffness of the material at small and large strains, respectively. These slopes also provide information about the anisotropy of the material. The curve knee marks the transition between the low and high strain regimes and is identified in the region between the endpoint of the linear E1 zone and the starting point of the linear E2 zone (see Fig. 2). We determined the knee point by first identifying the stretch at this point. This was achieved by finding the intersection of two regression lines (with slopes E1 and E2) fitted to the low and high strain ranges of the stress-strain curves, respectively (see Fig. 2). The corresponding stress at the knee point was then obtained as the value on the stress-strain curve at the identified stretch.

Constitutive model and parameter calibration

According to the response observed in esophageal tissue samples (see Section "Results and discussion") and in previous reports assessing the mechanical behavior of the esophagus of different animals, this material shows a hyperelastic-anisotropic mechanical behavior. Consequently, Gasser’s constitutive model40 is selected, which is suitable for characterizing the biomechanical response of various fiber-reinforced soft tissues. Since esophageal tissue has a significant water content, it is assumed to be incompressible, which is consistent with previous experimental observations reporting negligible volume changes in esophageal and other soft tissues under physiological loading conditions9,26,41. Gasser’s model postulates the existence of two families of fibers, with average orientations in the reference (initial) configuration  and

and  . The model also supposes that the probability density of finding fibers with a certain orientation follows a univariate Von-Mises distribution and, subsequently, the dispersion of fibers (i.e. the deviation between actual and average orientations) is rotationally symmetric. As a result, the constitutive model does not account for the contribution of fibers in the thickness direction42. We further assume that the mean fiber directions,

. The model also supposes that the probability density of finding fibers with a certain orientation follows a univariate Von-Mises distribution and, subsequently, the dispersion of fibers (i.e. the deviation between actual and average orientations) is rotationally symmetric. As a result, the constitutive model does not account for the contribution of fibers in the thickness direction42. We further assume that the mean fiber directions,  and

and  , lie in the longitudinal-circumferential (z-

, lie in the longitudinal-circumferential (z- ) tangential plane and are symmetrically aligned with respect to the longitudinal direction of the esophagus (see Fig. 3).

) tangential plane and are symmetrically aligned with respect to the longitudinal direction of the esophagus (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Scheme of fiber distribution assumed by Gasser’s hyperelastic model.

The total strain energy function of the model can be additively decomposed as  where

where  is an isotropic component associated with an elastin matrix,

is an isotropic component associated with an elastin matrix,  is an anisotropic component associated with collagen fibers, and

is an anisotropic component associated with collagen fibers, and  is a volumetric component to impose quasi-incompressibility. The total strain energy function is given by:

is a volumetric component to impose quasi-incompressibility. The total strain energy function is given by:

|

1 |

where  is the first strain invariant of the deviatoric Cauchy-Green strain

is the first strain invariant of the deviatoric Cauchy-Green strain  defined as

defined as  with

with  the Jacobian determinant of the deformation gradient, whereas

the Jacobian determinant of the deformation gradient, whereas  and

and  are pseudo-invariants in terms of average fiber-family directions (

are pseudo-invariants in terms of average fiber-family directions ( and

and  ).

).

The constitutive model comprises the following positive constants:  is a shear modulus associated with the initial slope of the stress-strain curves;

is a shear modulus associated with the initial slope of the stress-strain curves;  is a unit-less parameter that quantifies the dispersion of the collagen fibers from their average direction (represented by an orientation angle,

is a unit-less parameter that quantifies the dispersion of the collagen fibers from their average direction (represented by an orientation angle,  ); the stress-like parameter

); the stress-like parameter  is associated with the stiffness in the end zone of stress-stretch curves and the parameter

is associated with the stiffness in the end zone of stress-stretch curves and the parameter  is a unit-less constant that is difficult to interpret physically. When

is a unit-less constant that is difficult to interpret physically. When  , the Gasser model is equivalent to the Holzapfel model23, and if

, the Gasser model is equivalent to the Holzapfel model23, and if  an analogous to the Demiray model43 is obtained. The bulk modulus was fixed at a relatively high value (

an analogous to the Demiray model43 is obtained. The bulk modulus was fixed at a relatively high value ( ) to penalize volume changes and enforce a quasi-incompressibility constraint (

) to penalize volume changes and enforce a quasi-incompressibility constraint ( ).

).

Five constants of Gasser’s hyperelastic model ( ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  ), associated with the esophageal material tested in uniaxial tension, were obtained by fitting the average experimental stress-stretch curves of each group to nonlinear analytical expressions reported by García-Herrera et al.39. For the calibration of the constitutive model, we adopted a Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm18, to minimize the squared difference between experimental data (over longitudinal and circumferential directions) of an experimental group (CN or MN) and the analytical response associated with a set of material parameters. Results of the calibration procedure are presented in Table 4.

), associated with the esophageal material tested in uniaxial tension, were obtained by fitting the average experimental stress-stretch curves of each group to nonlinear analytical expressions reported by García-Herrera et al.39. For the calibration of the constitutive model, we adopted a Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm18, to minimize the squared difference between experimental data (over longitudinal and circumferential directions) of an experimental group (CN or MN) and the analytical response associated with a set of material parameters. Results of the calibration procedure are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Constitutive model parameters determined for internal (Int), external (Ext), and integrated (IT) esophageal tissue of control (CN) and melatonin-treated (MN) groups.

[kPa] |

[kPa] |

|

|

|

NRMSD |

fit fitLong. |

fit fitCirc. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CN | Int | 42.603 | 43.102 | 1.110 | 0.161 | 11.89 | 0.035 | 0.96 | 0.74 |

| Ext | 9.966 | 39.826 | 0.014 | 0.241 | 16.18 | 0.009 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |

| IT | 11.710 | 4.028 | 0.006 | 0.164 | 21.54 | 0.017 | 0.99 | 0.92 | |

| MN | Int | 16.479 | 82.234 | 0.541 | 0.245 | 20.64 | 0.014 | 0.98 | 0.97 |

| Ext | 11.546 | 22.541 | 0.288 | 0.255 | 31.09 | 0.012 | 0.98 | 0.99 | |

| IT | 6.794 | 4.276 | 0.249 | 0.090 | 18.88 | 0.031 | 0.97 | 0.81 | |

Histology

In addition to samples tested in uniaxial tension, additional esophageal tissue samples designated for histological analysis were excised and immersed in paraformaldehyde for 24 hours at 4 °C. Then, tissue samples were embedded in kerosene and cut into 5 μm-thick sections with a Leitz rotary microtome, mounted on slides, and stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) and Elastic Van Gieson (EVG) stains. Subsequent observation of stained samples was performed using an Olympus BX41 microscope, and micrographs were captured with a Jenoptik model ProgRes C3 digital camera at 4× and 10× magnification.

Micrographs were utilized for the following purposes: (1) to examine and perform morphological measurements on cross-sections of mucosa, submucosa, and external muscular layers; (2) to quantify the percentage composition (number of pixels in a delimited area divided by number of total pixels) of collagen fibers in submucosa and external muscular layers, and; (3) to determine the cell density per unit area in the stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium, the area where the greatest number of nuclei is observed. Process (1) consisted of taking the average of five thickness measurements performed with random spacing, since layers presented irregularities and thickness was not homogeneous in micrographs. Processes (2) and (3) were carried out within a Region Of Interest (ROI) of size 350 × 140 μm2. The protocol for computational image processing closely followed the procedure outlined by Navarrete et al.37, involving the selection of three main colors in small areas of the micrograph to obtain a stain-matrix to quantify areas and count nuclei within the ROI, using Fiji plugin (ImageJ)44 and GIMP (version 2.10.32) software.

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the data sets and a Shapiro-Wilk test was applied in cases where the sample size was small. Subsequently, an F-test was performed to compare the differences in variance between the groups. After these tests were completed, the appropriate statistical method was selected to determine the significance of the differences between the means. According to the statistical analysis described by Navarrete et al.45, different procedures were applied. An unpaired t-test was used when both groups showed normal distribution and equal variance. Welch’s t-test was applied when the groups exhibited a normal distribution but statistically significant differences in variance. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used when one or both groups did not show normality. Statistical differences were considered significant with a p-value  0.0546, indicating a low probability that the null hypothesis is true.

0.0546, indicating a low probability that the null hypothesis is true.

Results and discussion

Uniaxial tensile tests

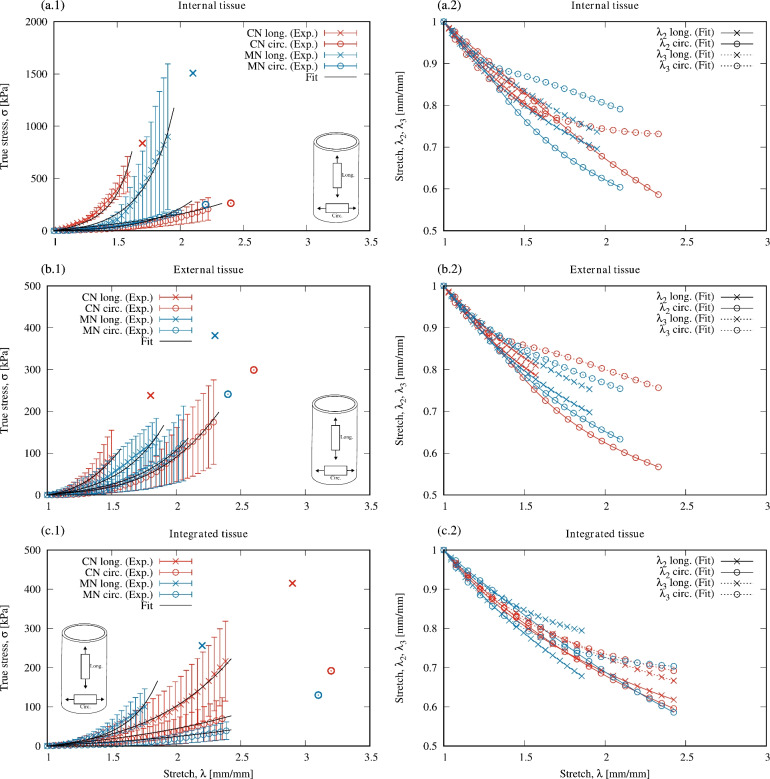

Figure 4 show average stress-versus-stretch curves for control (CN) and melatonin-treated (MN) groups and for each tissue classification (Int, Ext, and IT), in addition to the constitutive model calibration, including theoretical transverse stretches. Stress-strain curves revealed the anisotropy of the tested material, with a stiffer response along the longitudinal direction compared to the circumferential direction, and the presence of two quasi-linear zones.

Fig. 4.

Uniaxial stress-stretch curves (mean ± SD) including mean rupture point, and transversal stretches. Control (CN) and melatonin (MN) groups. Internal tissue (Int; a.1 and a.2), external tissue (Ext; b.1 and b.2), and integrated tissue (IT; c.1 and c.2).

Table 3 includes average rupture points – the stretch-stress pair ( ,

,  ) – for both directions tested. The highest value of rupture stress for integrated tissue (IT) was found in the control group along the longitudinal direction (CN/IT: 414.4 ± 78.6 kPa). In comparison, for external (Ext) and internal (Int) tissue the highest rupture stress was associated with the melatonin group along the longitudinal direction (MN/Ext: 381.0 ± 118.5 kPa; MN/Int: 1615.6 ± 661.3 kPa). However, no significant differences were found in rupture stress between control (CN) and melatonin (MN) groups. Regarding stretch at rupture, in most cases, higher values were found along the circumferential direction compared to the longitudinal direction (see Table 3).

) – for both directions tested. The highest value of rupture stress for integrated tissue (IT) was found in the control group along the longitudinal direction (CN/IT: 414.4 ± 78.6 kPa). In comparison, for external (Ext) and internal (Int) tissue the highest rupture stress was associated with the melatonin group along the longitudinal direction (MN/Ext: 381.0 ± 118.5 kPa; MN/Int: 1615.6 ± 661.3 kPa). However, no significant differences were found in rupture stress between control (CN) and melatonin (MN) groups. Regarding stretch at rupture, in most cases, higher values were found along the circumferential direction compared to the longitudinal direction (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Parameters obtained from stress-stretch uniaxial curves (mean ± SD), control (CN), and melatonin-treated (MN) groups.

| CN | E1 [kPa] |

E2 [kPa] |

[MPa] |

[mm/mm] |

[kPa] |

[mm/mm] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Int | Long. | 421 ± 12 | 1682 ± 1053 | 121 ± 25 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 837 ± 665 | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

| Circ. | 27 ± 18 | 349 ± 141 | 36 ± 27 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 263 ± 88 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | |

| Ext | Long. | 30 ± 14 | 419 ± 168 | 32 ± 25 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 238 ± 159 | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| Circ. | 4 ± 1 | 265 ± 157 | 17 ± 10 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 299 ± 32 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | |

| IT | Long. | 35 ± 18 | 457 ± 75 | 85 ± 65 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 415 ± 136 | 2.9 ± 0.2 |

| Circ. | 21 ± 20 | 168 ± 68 | 51 ± 41 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 192 ± 113 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | |

| MN | E1 [kPa] |

E2 [kPa] |

[MPa] |

[mm/mm] |

[kPa] |

[mm/mm] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Int | Long. | 200 ± 28 | 2295 ± 1223 | 167 ± 33 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1507 ± 690 | 2.1 ± 0.3 |

| Circ. | 14 ± 6 | 338 ± 162 | 29 ± 32 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 250 ± 56 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | |

| Ext | Long. | 60 ± 63 | 598 ± 54 | 72 ± 33 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 381 ± 94 | 2.3 ± 0.2 |

| Circ. | 6 ± 2 | 502 ± 203 | 35 ± 41 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 241 ± 338 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | |

| IT | Long. | 41 ± 21 | 240 ± 58 | 24 ± 11 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 256 ± 201 | 2.2 ± 0.4 |

| Circ. | 9 ± 3 | 118 ± 52 | 21 ± 14 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 130 ± 144 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | |

Internal (Int), external (Ext), and integrated tissue (IT) samples along longitudinal (long.) and circumferential (circ.) directions.

Comparing our experimental results with previous studies that performed uniaxial tensile tests on lamb esophagus, Sommer et al.12 report higher rupture stresses than those obtained here in external tissue (Ext/Long: 0.7 ± 0.3 MPa; Ext/Circ: 0.6 ± 0.3 MPa) and in internal tissue (mucosa and submucosa) (Int/Long: 2.6 ± 1 MPa; Int/Circ: 1.5 ± 0.7 MPa). In both Sommer et al.12 study and our work, the internal tissue exhibited higher rupture stress than the external tissue and similar rupture stretch along the circumferential direction (above 2.0 mm/mm). Ngwangwa et al.13 report rupture points from biaxial tests performed on lamb esophagus integrated tissue, with (engineering) rupture stresses lower than those obtained here (IT/Long: 41.42 ± 32.02 kPa; IT/Circ: 82.87 ± 30.36 kPa). Comparing lamb rupture stresses with those reported for the esophagus of other animals, Yang et al.10 and Lin et al.11 performed uniaxial tensile tests to samples of pig esophagus, showing higher rupture stresses for both internal and external tissue and in different regions (cervical, thoracic and abdominal). Stavropoulou et al.47 also studied pig esophagus, presenting rupture stresses similar to ours for the mucosa-submucosa layer in cervical and thoracic regions and higher in the abdominal region.

The initial slope (E1), final slope (E2), and the elbow point located in the transition zone, all determined from stress-stretch curves, are shown in Table 3. Regarding the stiffness in the final zone of the curve (E2), Fig. 4 show a higher stiffness of internal tissue compared to external tissue. This behavior agrees with previous experimental results that applied different mechanical tests to the esophagus of rats, rabbits, pigs, and lamb9–11,16,48. This is explained by the mucosa-submucosa layer offering high resistance to deformation to prevent over-dilation of the esophagus16,49. However, some studies report a tissue response contrary to that previously described13,17.

We used crosshead displacement to measure strain, which assumes homogeneous stress and strain and can introduce errors due to sample slippage at the clamps. Alternative techniques such as Digital Image Correlation (DIC) and marker tracking provide localized strain measurements. However, these methods also have practical limitations, including sample surface preparation requirements, sensitivity to lighting and imaging conditions, resolution and tracking errors, and tissue-marker interactions, especially when applied to soft tissues undergoing large deformations50–53. Despite its limitations, the use of crosshead displacement for strain estimation remains a reasonable method under well-controlled conditions, especially when combined with optimized grip design and testing protocols to minimize slippage. A previous study36 showed that with an appropriate specimen fixation protocol, crosshead displacement closely matched video extensometer measurements under nearly homogeneous deformation conditions at the mid-length of arterial samples.

The results of the uniaxial tensile tests were used to determine the parameters of the Gasser anisotropic constitutive model40. Table 4 summarizes the results of the calibration of the constitutive model, including the coefficient of determination ( ) for the longitudinal and circumferential directions. In the context of this work, the coefficient of determination (

) for the longitudinal and circumferential directions. In the context of this work, the coefficient of determination ( ) quantifies the goodness of fit between the average experimental stress-stretch curve and the analytical estimate of the Gasser model. A high value of

) quantifies the goodness of fit between the average experimental stress-stretch curve and the analytical estimate of the Gasser model. A high value of  indicates that the hyperelastic model, on average, captures the nonlinear anisotropic biomechanical behavior of the esophagus while maintaining physically coherent responses22.

indicates that the hyperelastic model, on average, captures the nonlinear anisotropic biomechanical behavior of the esophagus while maintaining physically coherent responses22.

Values of shear modulus ( ) indicated that in both groups, control (CN) and melatonin-treated (MN), internal tissue (Int) shows a higher stiffness in the initial zone of the stress-strain curves compared to external (Ext) and integrated (IT) tissue. Values of constant

) indicated that in both groups, control (CN) and melatonin-treated (MN), internal tissue (Int) shows a higher stiffness in the initial zone of the stress-strain curves compared to external (Ext) and integrated (IT) tissue. Values of constant  denoted a stiffer behavior of internal tissue in the final zone of stress-stretch curves. Both internal and integrated tissue show an intermediate dispersion of fibers (value of

denoted a stiffer behavior of internal tissue in the final zone of stress-stretch curves. Both internal and integrated tissue show an intermediate dispersion of fibers (value of  ) while external tissue presents the highest dispersion. Notice that all mean orientation angles of fibers obtained were

) while external tissue presents the highest dispersion. Notice that all mean orientation angles of fibers obtained were  , suggesting that it is more likely to find reinforcement fibers preferentially oriented in the longitudinal direction, as proposed in previous research12,16, indicating that a material developed in the context of tissue engineering as a potential replacement of the esophagus should exhibit a higher stiffness along that direction.

, suggesting that it is more likely to find reinforcement fibers preferentially oriented in the longitudinal direction, as proposed in previous research12,16, indicating that a material developed in the context of tissue engineering as a potential replacement of the esophagus should exhibit a higher stiffness along that direction.

The transverse stretches were not measured directly due to experimental limitations. The theoretical transverse stretches predicted by the constitutive model, shown in Fig. 4(a.2), (b.2) and (c.2), had a strictly decreasing behavior with increasing applied load. However, the uniaxial tensile response of Gasser’s model can, for some parameter sets, exhibit an increasing transverse stretch with an increasing major stretch, mimicking a material with a negative Poisson ratio40. This auxetic behavior, attributed to a low matrix-to-fiber stiffness ratio54, contradicts experimental observations of soft tissues such as the esophagus55. We present these predictions to confirm that our calibration avoids this flaw, matching the known mechanical behavior of the material.

Histological analysis

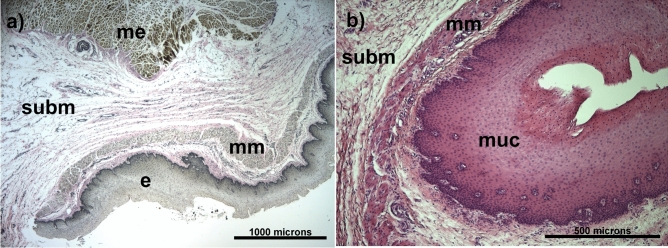

Quantification of microstructural components of the esophagus allows a better understanding of its biomechanical behavior. Fig. 5a shows a histological sample with EVG staining in which the microstructural composition of the esophagus can be observed. Three out of four main layers can be identified: in the innermost part mucosa and submucosa layers are visualized, both presenting collagen fibers (in red), a few thin elastin fibers, cell nuclei, and some blood vessels. In a portion of the external muscularis layer, it was possible to identify a lower density of collagen fibers arranged in an apparently random fashion. Figure 5b shows a histological specimen with HE staining in which the stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium, the area with the highest density of cell nuclei, is observed. The lamina propria was seen as a thin layer of connective tissue, along the muscularis mucosa layer.

Fig. 5.

Histology of lamb esophagus: (a) In the image using the Elastic Van Gieson (EVG) technique, the epithelium (e) is visible, and the underlying muscularis mucosa (mm) can be identified. Surrounding it is the submucosa (subm), composed of connective tissue (collagen and elastic fibers). The outermost layer corresponds to the muscularis externa (m), consisting of smooth muscle cells. (b) In the image using Hematoxylin-Eosin (H&E) staining, corresponding to the mucosa (muc), a stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium can be observed.

Morphological measurements for mucosa, submucosa, and muscularis-externa layers are shown in Table 5). These layers showed a similar thickness, with no statistically significant differences when CN and MN groups were compared. The adventitia was excluded as this layer was removed during cleaning procedures and was not visible in most micrographs. Although the CN group had a higher mean cell density than the MN group, this difference was also statistically insignificant.

Table 5.

Morphological measurements performed in the mucosa, submucosa, and muscularis externa esophageal layers for control (CN) and melatonin-treated (MN) groups (mean ± SD).

| Control (CN) | Melatonin (MN) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mucosa thickness [μm] | 560.5 ± 79.9 | 540.5 ± 60.1 |

| Submucosa thickness [μm] | 1069.5 ± 27.6 | 1032.6 ± 253.2 |

| Muscularis externa thickness [μm] | 1850.5 ± 434.9 | 1790.6 ± 359.8 |

|

Cellular density of stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium [cells/μm2] × 10−3 |

2.66 ± 0.3 | 1.92 ± 0.2 |

Regarding the percentage content of collagen in regions of interest, similar values were obtained in CN and MN groups, with no significant differences in the submucosa layer (CN: 23.6 ± 0.8%; MN: 23.8 ± 1.1% of collagen) and muscularis-externa layer (CN: 11.3 ± 0.9%; MN: 13.0 ± 1.1%) (see Fig. 6). However, collagen was mostly found in the submucosa layer and its percentage composition was significantly higher than that of external muscularis, consistent with previous reports quantifying the collagen fraction16,27,56.

Fig. 6.

Collagen content in control (CN) and melatonin-treated (MN) groups. Representative histological sections of the (a) submucosa layer and (b) muscularis externa layer stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin (H&E) (mean ± SD). Pink collagen (arrows) fibers are visible in both the submucosa and muscularis externa layers.

In the study by Stavropoulou et al.47, histological samples were divided into different regions and orientations. For the abdominal region, an average collagen content of 22% was reported for the mucosa-submucosa and 14% and 15% for the inner and outer muscle, respectively, while lower values were reported for other regions. The work of Sommer et al.12 reports collagen fibers in connective tissue (present in the submucosa) preferentially along the longitudinal direction of the esophagus (which explains the anisotropy of the tissue and a greater stiffness in that direction) and muscle fibers with a sinusoidal shape.

A limitation of our study is that the orientation of fibrillar collagen was not evaluated experimentally. Instead, the parameters of the constitutive model associated with the fibers, i.e. the average orientation and dispersion of two symmetrically aligned fiber families, were determined by the calibration procedure.

Histology alone, while revealing the presence of collagen fibers, is not sufficient to capture the distribution of fiber directions. In particular, it does not provide the means to measure the extent of out-of-plane fiber orientation, reported to be significant in arterial tissues42. Gasser‘s model assumes symmetric fiber dispersion and therefore does not consider the contribution of fibers in the thickness direction40. In addition, the estimation of fiber orientations from a single transverse section of the esophagus is probably not representative of the full spectrum of fiber orientations within the tissue.

Several experimental microscopy techniques have been used to study collagen fiber orientation distributions, including second harmonic generation (SHG)57,58, polarized light (PL)59, confocal (CF)60,61, transmission electron (TEM)62, atomic force (AFM)63, and multiphoton microscopy (MPM)64,65. Other techniques such as small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS)66 and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)67 can also be used. These techniques have the potential to reveal the asymmetrical distribution of the fiber orientations and their contribution to the overall mechanical behavior of the tissue.

Conclusions

In this work, we characterized the passive mechanical response of the esophagus of newborn lambs assessing whether a melatonin treatment could alter this behavior. Two groups, namely control (CN) and melatonin-treated (MN), were contrasted and biomechanical properties were evaluated at macro and microstructural levels.

On the one hand, in the macroscopic evaluation, based on experimental results of uniaxial tensile tests, we determined the geometrical properties of stress-strain curves, without finding significant differences between CN and MN groups. On the other hand, the microscopic evaluation involved a histological analysis from which no significant differences were found between CN and MN groups, as layer thickness (of the mucosa, submucosa, and external muscularis layers), nuclei count (carried out in the mucosa layer) and percentage fraction of collagen fibers (estimated in the submucosa and external muscularis layers) were similar. Our results suggest that supplying low melatonin doses does not alter the passive mechanical response of lamb esophageal tissue.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

E.R., C.G-H., A.G. and E.A.H., developed the concept and design of the work. E.R., C.G-H., E.A.H. and A.G. performed biomechanical tests. E.R., C.G-H., E.A.H.., D.J.C., E.B., A.B., A.G. and C.G., collected, analyzed, and interpreted the experimental data, E.R., E.B., and A.B. analyzed the analitical and numerical results. E.R., C.G-H., E.A.H., D.J.C., A.B., A.G. and C.G critically revised the article and approved the final version.

Funding

The support provided by “La Dirección de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (DICYT)” through DICYT project N°052316RM_DAS and the National Agency for Research and Development (ANID) through FONDECYT projects N° 1151119 and N° 1220956, is gratefully acknowledged. AB thanks ANID PCHA/Doctorado Nacional 2021-21211826.

Data availibility

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the following Github repository: https://github.com/ebritojara/Paper_MelatoninLambEsophagus.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-96288-w.

References

- 1.Oezcelik, A. & DeMeester, S. R. General anatomy of the esophagus. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg.21(2), 289–97 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yokosawa, S. et al. Identification of the layered morphology of the esophageal wall by optical coherence tomography. World J. Gastroenterol.: WJG15(35), 4402 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sánchez, Molina D. A constitutive model of human esophagus tissue with application for the treatment of stenosis [Doctoral thesis]. Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (2013).

- 4.Gregersen, H., Lee, T., Chien, S., Skalak, R. & Fung, Y. Strain distribution in the layered wall of the esophagus. J. Biomech. Eng.121(5), 442–8 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toczewski, K. et al. Biomechanics of esophageal elongation with traction sutures on experimental animal model. Sci. Rep.12, 3420 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biro, E. et al. Ultrastructural changes in esophageal tissue undergoing stretch tests with possible impact on tissue engineering and long gap esophageal repairs performed under tension. Sci. Rep.13, 1750 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Totonelli, G. et al. Esophageal tissue engineering: A new approach for esophageal replacement. World J. Gastroenterol.: WJG18(47), 6900 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liao, D., Zhao, J., Fan, Y. & Gregersen, H. Two-layered quasi-3D finite element model of the oesophagus. Med. Eng. Phys.26(7), 535–43 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang, J., Zhao, J., Liao, D. & Gregersen, H. Biomechanical properties of the layered oesophagus and its remodelling in experimental type-1 diabetes. J. Biomech.39(5), 894–904 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang, W., Fung, T., Chian, K. & Chong, C. Directional, regional, and layer variations of mechanical properties of esophageal tissue and its interpretation using a structure-based constitutive model. J. Biomech. Eng.128(3), 409–18 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin, C. et al. Friction behavior between endoscopy and esophageal internal surface. Wear376, 272–80 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sommer, G. et al. Multiaxial mechanical response and constitutive modeling of esophageal tissues: impact on esophageal tissue engineering. Acta Biomater.9(12), 9379–91 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ngwangwa, H. et al. Biomechanical analysis of sheep oesophagus subjected to biaxial testing including hyperelastic constitutive model fitting. Heliyon.8(5), e09312 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saxena, A. K., Biro, E., Sommer, G. & Holzapfel, G. A. Esophagus stretch tests: Biomechanics for tissue engineering and possible implications on the outcome of esophageal atresia repairs performed under excessive tension. Esophagus18(2), 346–52 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang, W., Fung, T., Chian, K. & Chong, C. 3D mechanical properties of the layered esophagus: Experiment and constitutive model. J. Biomech. Eng.128(6), 899–908 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stavropoulou, E. A., Dafalias, Y. F. & Sokolis, D. P. Biomechanical and histological characteristics of passive esophagus: Experimental investigation and comparative constitutive modeling. J. Biomech.42(16), 2654–63 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren, P., Deng, X., Li, K., Li, G. & Li, W. 3D biomechanical properties of the layered esophagus: Fung-type SEF and new constitutive model. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol.20(5), 1775–88 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moré, J. J. The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm: Implementation and theory. In: Numerical analysis. p. 105-16 (Springer, 1978).

- 19.Nelder, J. A. & Mead, R. A simplex method for function minimization. Comput. J.7(4), 308–13 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Back, T. Evolutionary algorithms in theory and practice: Evolution strategies, evolutionary programming, genetic algorithms. (Oxford University Press, 1996).

- 21.Rivera, E. et al. Biomechanical characterization of the passive response of the thoracic aorta in chronic hypoxic newborn lambs using an evolutionary strategy. Sci. Rep.11(1), 1–11 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canales, C., García-Herrera, C., Rivera, E., Macías, D. & Celentano, D. Anisotropic hyperelastic material characterization: Stability criterion and inverse calibration with evolutionary strategies. Mathematics11(4), 922 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holzapfel, G. A., Gasser, T. C. & Ogden, R. W. A new constitutive framework for arterial wall mechanics and a comparative study of material models. J. Elast. Phys. Sci. Solids61(1), 1–48 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holzapfel, G. A., Sommer, G., Gasser, C. T. & Regitnig, P. Determination of layer-specific mechanical properties of human coronary arteries with nonatherosclerotic intimal thickening and related constitutive modeling. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol.289(5), H2048-58 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Natali, A. N., Carniel, E. L. & Gregersen, H. Biomechanical behaviour of oesophageal tissues: Material and structural configuration, experimental data and constitutive analysis. Med. Eng. Phys.31(9), 1056–62 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durcan, C. et al. Experimental investigations of the human oesophagus: Anisotropic properties of the embalmed mucosa-submucosa layer under large deformation. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol.21(6), 1685–702 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durcan, C. et al. Experimental investigations of the human oesophagus: Anisotropic properties of the embalmed muscular layer under large deformation. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol.21(4), 1169–1186 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun, H., Gusdon, A. M. & Qu, S. Effects of melatonin on cardiovascular diseases: Progress in the past year. Curr. Opin. Lipidol.27(4), 408 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou, H. et al. Protective role of melatonin in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury: From pathogenesis to targeted therapy. J. Pineal Res.64(3), e12471 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bang, C., Yang, Y. & Baik, G. H. Melatonin for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease; protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine98(4), 14241 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konturek, P. C. et al. Esophagoprotection mediated by exogenous and endogenous melatonin in an experimental model of reflux esophagitis. J. Pineal Res.55(1), 46–57 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lahiri, S. et al. Melatonin protects against experimental reflux esophagitis. J. Pineal Res.46(2), 207–13 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kandil, T. S., Mousa, A. A., El-Gendy, A. A. & Abbas, A. M. The potential therapeutic effect of melatonin in gastro-esophageal reflux disease. BMC Gastroenterol.10(1), 1–9 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rivera, E., García-Herrera, C., González-Candia, A., Celentano, D. J. & Herrera, E. A. Effects of melatonin on the passive mechanical response of arteries in chronic hypoxic newborn lambs. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater.112, 104013 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.García-Herrera, C. Mechanical behaviour of the human ascending aorta: Characterization and numerical simulation [Doctoral thesis]. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (2008).

- 36.García-Herrera, C. M. et al. Mechanical characterisation of the human thoracic descending aorta: Experiments and modelling. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin.15(2), 185–93 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Navarrete, A. et al. Study of the effect of treatment with atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and cinaciguat in chronic hypoxic neonatal lambs on residual strain and microstructure of the arteries. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol.8, 590488 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laubrie, J. D. et al. Hyperelastic and damage properties of the hypoxic aorta treated with Cinaciguat. J. Biomech.147, 111457 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.García-Herrera, C. M., Bustos, C. A., Celentano, D. J. & Ortega, R. Mechanical analysis of the ring opening test applied to human ascending aortas. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin.19(16), 1738–48 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gasser, T. C., Ogden, R. W. & Holzapfel, G. A. Hyperelastic modelling of arterial layers with distributed collagen fibre orientations. J. R. Soc. Interface3(6), 15–35 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gilchrist, M., Murphy, J. G., Parnell, W. & Pierrat, B. Modelling the slight compressibility of anisotropic soft tissue. Int. J. Solids Struct.51(23–24), 3857–65 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holzapfel, G. A., Niestrawska, J. A., Ogden, R. W., Reinisch, A. J. & Schriefl, A. J. Modelling non-symmetric collagen fibre dispersion in arterial walls. J. R. Soc. Interface12(106), 20150188 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Demiray, H. A note on the elasticity of soft biological tissues. J. Biomech.5(3), 309–11 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods9(7), 676–82 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Navarrete, Á. et al. Biomechanical effects of hemin and sildenafil treatments on the aortic wall of chronic-hypoxic lambs. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol.12, 1406214 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glantz, S. A., Slinker, B. K. & Neilands, T. B. Primer of applied regression & analysis of variance Vol. 654 (McGraw-Hill Inc, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stavropoulou, E. A., Dafalias, Y. F. & Sokolis, D. P. Biomechanical behavior and histological organization of the three-layered passive esophagus as a function of topography. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng.226(6), 477–90 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liao, D., Fan, Y., Zeng, Y. & Gregersen, H. Stress distribution in the layered wall of the rat oesophagus. Med. Eng. Phys.25(9), 731–8 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gregersen, H. Biomechanics of the gastrointestinal tract: New perspectives in motility research and diagnostics (Springer, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okotie, G., Duenwald-Kuehl, S., Kobayashi, H., Wu, M. J. & Vanderby, R. Tendon strain measurements with dynamic ultrasound images: Evaluation of digital image correlation. J. Biomech. Eng.134, 024504 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prusa, G. et al. Strain evaluation of axially loaded collateral ligaments: A comparison of digital image correlation and strain gauges. Biomed. Eng. Online22(1), 13 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Innocenti, B., Larrieu, J. C., Lambert, P. & Pianigiani, S. Automatic characterization of soft tissues material properties during mechanical tests. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J.7(4), 529 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Todros, S., Pianigiani, S., de Cesare, N., Pavan, P. G. & Natali, A. N. Marker tracking for local strain measurement in mechanical testing of biomedical materials. J. Med. Biol. Eng.39, 764–72 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Horgan, C. & Murphy, J. Some unexpected predictions from strongly anisotropic hyperelastic constitutive models of soft tissue. Mech. Soft Mater.2, 1–14 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Skacel, P. & Bursa, J. Poisson’s ratio of arterial wall - Inconsistency of constitutive models with experimental data. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater.54, 316–27 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sokolis, D. P. Structurally-motivated characterization of the passive pseudo-elastic response of esophagus and its layers. Comput. Biol. Med.43(9), 1273–85 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sahu, S. P. et al. Characterization of fibrillar collagen isoforms in infarcted mouse hearts using second harmonic generation imaging. Biomed. Opt. Express12(1), 604–18 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nejim, Z., Navarro, L., Morin, C. & Badel, P. Quantitative analysis of second harmonic generated images of collagen fibers: A review. Res. Biomed. Eng.39(1), 273–95 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Turčanová, M. et al. Full-range optical imaging of planar collagen fiber orientation using polarized light microscopy. Biomed. Res. Int.2021(1), 6879765 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang, Z. et al. Application of laser scanning confocal microscopy in the soft tissue exquisite structure for 3D scan. Int. J. Burns Trauma8(2), 17 (2018). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Timin, G. & Milinkovitch, M. C. High-resolution confocal and light-sheet imaging of collagen 3D network architecture in very large samples. Iscience26(4), (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Szewczyk, P. K. & Stachewicz, U. Collagen fibers in crocodile skin and teeth: A morphological comparison using light and scanning electron microscopy. J. Bionic Eng.17, 669–76 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boyanich, R. et al. Application of confocal, SHG and atomic force microscopy for characterizing the structure of the most superficial layer of articular cartilage. J. Microsc.275(3), 159–71 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gade, P. S., Robertson, A. M. & Chuang, C. Y. Multiphoton imaging of collagen, elastin, and calcification in intact soft-tissue samples. Curr. Protoc. Cytom.87(1), e51 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jadidi, M., Sherifova, S., Sommer, G., Kamenskiy, A. & Holzapfel, G. A. Constitutive modeling using structural information on collagen fiber direction and dispersion in human superficial femoral artery specimens of different ages. Acta Biomater.121, 461–74 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tadimalla, S., Tourell, M. C., Knott, R. & Momot, K. I. Assessment of collagen fiber orientation dispersion in articular cartilage by small-angle X-ray scattering and diffusion tensor imaging: Preliminary results. Magn. Reson. Imaging48, 115–21 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brujic, D., Chappell, K. E. & Ristic, M. Accuracy of collagen fibre estimation under noise using directional MR imaging. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph.86, 101796 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the following Github repository: https://github.com/ebritojara/Paper_MelatoninLambEsophagus.