Abstract

Although COVID-19 is most well known for causing substantial respiratory pathology, it can also result in several extrapulmonary manifestations. These conditions include thrombotic complications, myocardial dysfunction and arrhythmia, acute coronary syndromes, acute kidney injury, gastrointestinal symptoms, hepatocellular injury, hyperglycemia and ketosis, neurologic illnesses, ocular symptoms, and dermatologic complications. Given that ACE2, the entry receptor for the causative coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, is expressed in multiple extrapulmonary tissues, direct viral tissue damage is a plausible mechanism of injury. In addition, endothelial damage and thromboinflammation, dysregulation of immune responses, and maladaptation of ACE2-related pathways might all contribute to these extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Here we review the extrapulmonary organ-specific pathophysiology, presentations and management considerations for patients with COVID-19 to aid clinicians and scientists in recognizing and monitoring the spectrum of manifestations, and in developing research priorities and therapeutic strategies for all organ systems involved.

The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), which is responsible for the disease COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019), has infected over 9.5 million people and has caused more than 480,000 deaths globally, as of 24 June 2020 (ref. 1). While SARS-CoV-2 is known to cause substantial pulmonary disease, including pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), clinicians have observed many extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Our clinical experience and the emerging literature suggest that the hematologic, cardiovascular, renal, gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary, endocrinologic, neurologic, ophthalmologic, and dermatologic systems can all be affected (Supplementary Table)2–6. This pathology may reflect either extrapulmonary dissemination and replication of SARS-CoV-2, as has been observed for other zoonotic coronaviruses7, or widespread immunopathological sequelae of the disease. To provide a perspective on these extrapulmonary manifestations, we discuss the pathophysiology and clinical impact of COVID-19 on various organ systems, accompanied by insights from our experience at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City at the epicenter of the pandemic.

Pathophysiology

SARS-CoV-2 seems to employ mechanisms for receptor recognition similar to those used by prior virulent coronaviruses such as SARS-CoV, the pathogen responsible for the SARS epidemic of 2003 (refs. 8–11). The coronavirus spike protein facilitates entry of the virus into target cells. The spike subunit of SARS-CoV and that of SARS CoV-2 engage ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) as an entry receptor (Fig. 1). In addition, cell entry requires priming of the spike protein by the cellular serine protease TMPRSS2 or other proteases12. Co-expression on the cell surface of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 is required for the completion of this entry process. In addition, the efficiency with which the virus binds to ACE2 is a key determinant of transmissibility, as shown in studies of SARS-CoV13. Recent studies have demonstrated higher affinity of binding of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2 than of SARS-CoV to ACE2, which may partially explain the increased transmissibility of SARS-CoV-214–16.

Fig. 1 |. Pathophysiology of COVID-19.

SARS-CoV-2 enters host cells through interaction of its spike protein with the entry receptor ACE2 in the presence of TMPRSS2 (far left). Proposed mechanisms for COVID-19 caused by infection with SARS-CoV-2 include (1) direct virus-mediated cell damage; (2) dysregulation of the RAAS as a consequence of downregulation of ACE2 related to viral entry, which leads to decreased cleavage of angiotensin I and angiotensin II; (3) endothelial cell damage and thromboinflammation; and (4) dysregulation of the immune response and hyperinflammation caused by inhibition of interferon signaling by the virus, T cell lymphodepletion, and the production of proinflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-6 and TNFα.

Key mechanisms that may have a role in the pathophysiology of multi-organ injury secondary to infection with SARS-CoV-2 include direct viral toxicity, endothelial cell damage and thromboinflammation, dysregulation of the immune response, and dysregulation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) (Fig. 1). The relative importance of these mechanisms in the pathophysiology of COVID-19 is currently not fully understood. While some of these mechanisms, including ACE2-mediated viral entry and tissue damage, and dysregulation of the RAAS, may be unique to COVID-19, the immune pathogenesis caused by the systemic release of cytokines and the microcirculation dysfunctions may also occur secondary to sepsis17.

Direct viral toxicity.

SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted mainly through direct or indirect respiratory-tract exposure. It has tropism for the respiratory tract, given the high expression of ACE2, its entry receptor, in multiple epithelial cell types of the airway, including alveolar epithelial type II cells in the lung parenchyma18,19. Live SARS-CoV-2 virus and viral subgenomic mRNA isolated from the upper airway can successfully be detected by RT-PCR. Later in the disease course, viral replication may occur in the lower respiratory tract20, which manifests in severe cases as pneumonia and ARDS.

Studies evaluating body-site-specific viral replication of SARS-CoV-2 have isolated viral RNA from fecal samples at high titers2,20 and, less commonly, from urine and blood21,22. Histopathological studies have reported organotropism of SARS-CoV-2 beyond the respiratory tract, including tropism to renal21,23, myocardial21,24, neurologic21, pharyngeal21, and gastrointestinal25 tissues. In addition, single-cell RNA-sequencing studies have confirmed expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in lung alveolar epithelial type II cells, nasal goblet secretory cells, cholangiocytes, colonocytes, esophageal keratinocytes, gastrointestinal epithelial cells, pancreatic β-cells, and renal proximal tubules and podocytes21,26–28. These findings suggest that multiple-organ injury may occur at least in part due to direct viral tissue damage. The mechanism of extrapulmonary spread of SARS-CoV-2, whether hematogenous or otherwise, remains elusive.

Endothelial cell damage and thromboinflammation.

Endothelial cell damage by virtue of ACE2-mediated entry of SARS-CoV-2 and subsequent inflammation and the generation of a prothrombotic milieu are other proposed pathophysiological mechanisms of COVID-1929–31. ACE2 expression has been demonstrated in arterial and venous endothelium of several organs29,32, and histopathological studies have found microscopic evidence of SARS-CoV-2 viral particles in endothelial cells of the kidneys31 and lungs29. Infection-mediated endothelial injury (characterized by elevated levels of von Willebrand factor) and endothelialitis (marked by the presence of activated neutrophils and macrophages), found in multiple vascular beds (including the lungs, kidney, heart, small intestine, and liver) in patients with COVID-19, can trigger excessive thrombin production, inhibit fibrinolysis, and activate complement pathways, initiating thromboinflammation and ultimately leading to microthrombi deposition and microvascular dysfunction31,33–36. Platelet–neutrophil cross-communication and activation of macrophages in this setting can facilitate a variety of proinflammatory effects, such as cytokine release, the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), and fibrin and/or microthrombus formation37–40. NETs further damage the endothelium and activate both extrinsic coagulation pathways and intrinsic coagulation pathways. They were detected at higher levels in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in a study from a large academic center in the USA (50 patients and 30 control participants), with a ‘pro-NETotic state’ positively correlating with severe illness41. Hypoxia-mediated hyperviscosity and upregulation of the HIF-1 (hypoxia-inducible factor 1) signaling pathway subsequent to acute lung injury may also contribute to the prothrombotic state42. Finally, direct coronavirus-mediated effects may also lead to an imbalance of pro- and anti-coagulant pathways43,44. Small case reports and case series have demonstrated the presence of fibrinous exudates and microthrombi in histopathological examinations in patients with COVID-1944–48.

Dysregulation of the immune response.

Dysregulated immune response and cytokine-release syndrome, due to overactivation of innate immunity in the setting of T cell lymphodepletion, characterize the presentations of severe COVID-1949. Prior preclinical and human studies with pathogenic human coronaviruses have proposed rapid viral replication, antagonism of interferon signaling, and activation of neutrophils and monocyte-macrophages as mediators of hyperinflammation50,51. Elevation of serum inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein, ferritin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, D-dimer, fibrinogen, and lactate dehydrogenase is predictive of subsequent critical illness and mortality in patients with COVID-194,5,52–54. These patterns of laboratory abnormalities have been compared with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis–macrophage-activation syndrome, previously demonstrated in pathological samples from patients who died from infection with SARS-CoV55,56. Higher levels of the cytokine IL-6 in the serum have also been linked to a worse prognosis4,5,52,54,57 and have been found to correlate with fibrinogen levels in patients with COVID-1958–60. Clinical trials for treating COVID-19 by targeting the IL-6 signaling pathway are underway and hope to mitigate the deleterious effects of the activation of this pathway55. Immune system–related manifestations found in patients with COVID-19, including those of cytokine-release syndrome, are presented in Box 1.

Box 1 |. Hematologic and immune system–related manifestations of COVID-19.

Clinical presentations

-

Laboratory markers:

Cell counts: lymphopenia, leukocytosis, neutrophilia, thrombocytopenia

Inflammatory markers: elevations in erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, ferritin, IL-6, lactate dehydrogenase

Coagulation indices: elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen; prolonged prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time

Arterial thrombotic complications: MI, ischemic stroke, acute limb, and mesenteric ischemia

Venous thrombotic complications: deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

Catheter-related thrombosis: thrombosis in arterial and venous catheters and extracorporeal circuits

Cytokine-release syndrome: high-grade fevers, hypotension, multi-organ dysfunction

COVID-19-specific considerations

Perform longitudinal evaluation of cell counts, inflammatory markers, and coagulation indices in hospitalized patients101

Recommend enrollment in clinical trials evaluating the benefit and safety of higher-than-usual prophylactic dose or therapeutic dose in the absence of documented thromboembolism36

If there is evidence of hyperinflammation, consider enrollment in clinical trials investigating the efficacy of targeted inhibitors of inflammatory cytokines of the innate immune system (e.g., IL-6 and IL-1) or their signaling pathways55

Global immunosuppression with corticosteroids may have a role in the setting of critical illness associated with cytokine storm55

General considerations

Perform routine risk assessment for venous thromboembolism for all hospitalized patients

Strongly consider pharmacological prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in the absence of absolute contraindications (active bleeding or severe thrombocytopenia)

Prefer low-molecular-weight heparins or unfractionated heparin over oral anticoagulants in most patients in the inpatient setting

Consider hepatic and renal function when determining appropriate dose and type of antithrombotic drugs

Consider post-hospitalization extended thromboprophylaxis on an individual patient basis, particularly for those with a history of critical illness

Dysregulation of the RAAS.

Maladaptive functions of the RAAS constitute another plausible pathophysiological mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 infection–related tissue damage. The RAAS is composed of a cascade of regulatory peptides that participate in key physiological processes of the body, including fluid and electrolyte balance, blood-pressure regulation, vascular permeability, and tissue growth61. ACE2, a membrane-bound aminopeptidase, has emerged as a potent counter-regulator of the RAAS pathway. ACE2 cleaves angiotensin I into inactive angiotensin 1–9 and cleaves angiotensin II into angiotensin 1–7, which has vasodilator, anti-proliferative, and antifibrotic properties62–64. While the pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2 may not be limited exclusively to ACE2-related pathways, these findings may have implications for the organ-specific clinical manifestations of COVID-19 (Fig. 2).

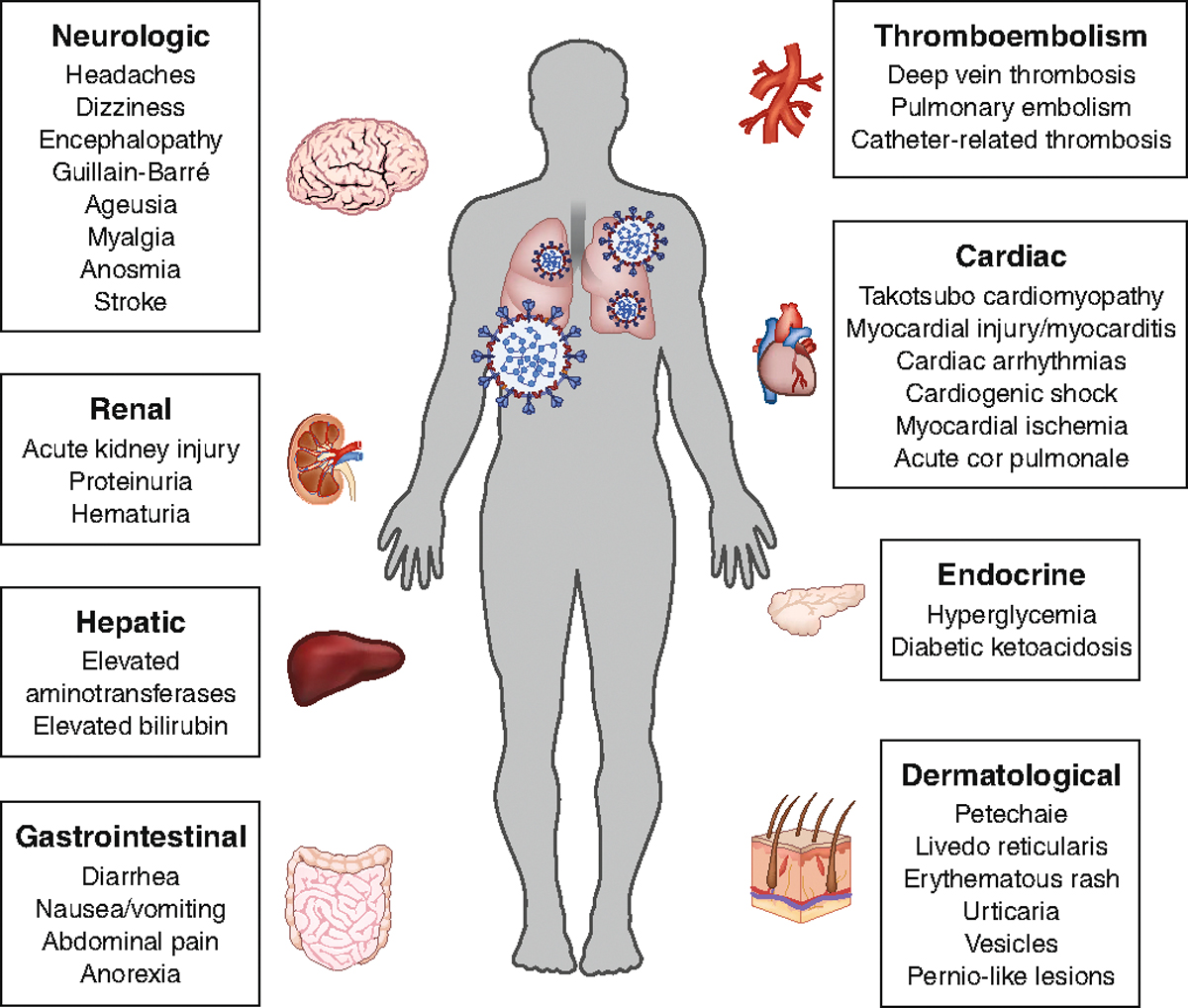

Fig. 2 |. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19.

The pulmonary manifestation of COVID-19 caused by infection with SARS-CoV-2, including pneumonia and ARDS, are well recognized. In addition, COVID-19 is associated with deleterious effects on many other organ systems. Common extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19 are summarized here.

Hematologic manifestations

Patients with COVID-19 may present with several laboratory abnormalities and thromboembolic complications. The hematologic manifestations and management considerations of COVID-19 are presented in Box 1.

Epidemiology and clinical presentation.

Lymphopenia, a marker of impaired cellular immunity, is a cardinal laboratory finding reported in 67–90% of patients with COVID-19, with prognostic association in the vast majority of studies published so far2,4,5,57,65–69. Studies examining specific lymphocyte subsets have revealed decreases in both CD4+ T cells70 and CD8+ T cells5 to be associated with severe COVID-1971. In addition, leukocytosis (especially neutrophilia), seen less commonly, is also a negative prognostic marker4,5,66. Thrombocytopenia, although often mild (in 5–36% of admissions), is associated with worse patient outcomes2,4,68,69,72. COVID-19-associated coagulopathy is marked by elevated levels of D-dimer and fibrinogen, with minor abnormalities in prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and platelet counts in the initial stage of infection73. Elevated levels of D-dimer at admission (reported in up to 46% of hospitalized patients) and a longitudinal increase during hospitalization have been linked with worse mortality in COVID-192,4,5,53,54,74,75.

Thrombotic complications were first reported from intensive care units (ICUs) in China76 and the Netherlands77 in up to 30% of patients. There is also emerging evidence of thrombosis in intravenous catheters and extracorporeal circuits, and arterial vascular occlusive events, including acute myocardial infarction (MI), acute limb ischemia, and stroke, in severely affected people in studies from the USA, Italy and France78–82. Subsequent studies from France and Italy have also reported high rates of thromboembolic events in critically ill patients with COVID-19 (17–22%) despite their having received prophylactic anticoagulation80,83–85. Indeed, in a cohort of 107 patients admitted to a single-center ICU with COVID-19, their rates of pulmonary emboli were notably higher than those of patients admitted to the same ICU during the same time interval in 2019 (20.6% versus 6.1%, respectively)86. Furthermore, multiple small studies in which critically ill patients with COVID-19 were routinely screened for thrombotic disease demonstrated high rates of thrombotic complications in these patients ranging from 69% to 85% despite thromboprophylaxis83,87,88. Variability in thromboprophylaxis regimens and screening schedules can help explain this variation in event rates across published studies.

Pathophysiology.

The potential proposed mechanisms by which lymphopenia occurs include direct cytotoxic action of the virus related to ACE2-dependent or ACE2-independent entry into lymphocytes29,89,90, apoptosis-mediated lymphocyte depletion50,91,92, and inhibitory effects of lactic acid on lymphocyte proliferation93. In addition, atrophy of the spleen and widespread destruction of lymphoid tissues have been described for both SARS and COVID-1989,94. Leukocytosis (especially neutrophilia) is thought to be a consequence of a hyperinflammatory response to infection with SARS-CoV-2 and/or secondary bacterial infections67. The abnormally high levels of D-dimer and fibrinogen in the blood during the early stages of infection are reflective of excessive inflammation, rather than overt disseminated intravascular coagulation, which is commonly seen only in later stages of COVID-1977,80.

The untempered inflammation, along with hypoxia and direct viral mediated effects, probably contributes to the high rates of thrombotic complications in COVID-19. The increased expression of ACE2 in endothelial cells after infection with SARS-CoV-2 may perpetuate a vicious cycle of endothelialitis that promotes thromboinflammation29. Collectively, hemostatic and inflammatory changes, which reflect endothelial damage and activation as well as critical illness, constitute a prothrombotic milieu, at least similar to and possibly more severe than that of other viral illnesses86,95,96.

In addition to the macrothrombotic events, the development of in situ thrombosis in small vessels of the pulmonary vasculature (pulmonary intravascular coagulopathy) is an area that requires further study97. Autopsy studies of patients who died due to COVID-19 have shown high rates of microvascular and macrovascular thromboses, especially in the pulmonary circulation29,98–100. A post-mortem series of seven patients from Germany showed that alveolar capillary microthrombi were nine times more common in people who died of COVID-19 than in those who died of influenza29. Microthrombi and microangiopathic pathology, associated with foci of hemorrhage, were also noted on autopsies of ten African-American patients with severe COVID-19 from New Orleans, Louisiana, USA100.

Management considerations.

Longitudinal evaluation of a complete blood count, with white-blood-cell differential, D-dimer, prothrombin time, and fibrinogen, is recommended during the hospitalization of patients with COVID-19, in accordance with interim guidelines from the International Society of Hemostasis and Thrombosis101. Trending inflammatory indices may help in the prediction of clinical outcomes and response to therapy in hospitalized patients. In addition, recently published interim consensus-based guidelines for the prevention and management of thrombotic disease in patients with COVID-19102 recommend routine risk assessment for venous thromboembolism for all hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Standard-dose pharmacological prophylaxis should be considered in the absence of absolute contraindications in such patients. Empiric use of higher-than-routine prophylactic-dose or therapeutic-dose anticoagulation in patients admitted to the ICU in absence of proven thromboses has also been implemented in some institutions. This is an area of ongoing intense discussions among experts, particularly for those patients who exhibit marked COVID-19-associated coagulopathy73,103.

A retrospective analysis found lower in-hospital mortality rates in patients with COVID-19 who received therapeutic anticoagulation104, although this study was carried out in a single center, and there is currently not sufficient evidence to recommend such a strategy. Randomized clinical trials investigating these questions are currently underway and will be crucial to establishing effective and safe strategies. Parenteral anticoagulants (such as low-molecular-weight or unfractionated heparin) are preferred to oral anticoagulants in the inpatient setting, given their short half-life and the ready availability of reversal agents, due to the possibility of drug–drug interactions when they are taken with antiviral treatments (such as ritonavir) and antibacterial treatments (such as azithromycin)102.

Cardiovascular manifestations

Several cardiovascular presentations of COVID-19 have been reported. Clinical manifestations and management considerations pertaining to the cardiovascular system are presented in Box 2.

Box 2 |. Cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19.

Clinical presentations

Myocardial ischemia and MI (type 1 and 2)

Myocarditis

Arrhythmia: new-onset atrial fibrillation and flutter, sinus tachycardia, sinus bradycardia, QTc prolongation (often drug induced), torsades de pointes, sudden cardiac death, pulse-less electrical activity

Cardiomyopathy: biventricular, isolated right or left ventricular dysfunction

Cardiogenic shock

COVID-19-specific considerations

Do not routinely discontinue ACE inhibitors or ARBs in patients already on them at home; assess on a case-by-case basis132,133

Perform an electrocardiogram or telemetry monitoring for patients at medium to high risk for torsades de pointes who are being treated with QTc-prolonging drugs138

Carefully consider the utility of diagnostic modalities, including cardiac imaging, invasive hemodynamic assessments, and endomyocardial biopsies, to minimize the risk of viral transmission139,140

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention remains preferred approach for most patients with STEMI; consider fibrinolytic therapy in select patients, especially if personal protective equipment is not available134–136

General considerations

Utilize non-invasive hemodynamic assessments, and measurement of lactate, troponin, and beta-natriuretic peptide concentrations, with sparing use of routine echocardiography for guidance about fluid resuscitation, vasoactive agents, and mechanical circulatory support

Minimize invasive hemodynamic monitoring, but can consider in select patients with mixed vasodilatory and cardiogenic shock

Consider point-of-care ultrasound to assess regional wall-motion abnormalities to help distinguish type 1 MI from myocarditis

Early catheterization and revascularization is recommended for high-risk patients with NSTEACS (e.g., GRACE score >140)

Consider medical therapy for low-risk patients with NSTEACS, particularly if the suspicion for type 1 MI is low

Monitor and correct electrolyte abnormalities to mitigate arrhythmia risk

Abbreviations: NSTEACS, non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; STEMI, ST-segment-elevation MI; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events.

Epidemiology and clinical presentation.

SARS-CoV-2 can cause both direct cardiovascular sequelae and indirect cardiovascular sequelae, including myocardial injury, acute coronary syndromes (ACS), cardiomyopathy, acute cor pulmonale, arrhythmias, and cardiogenic shock, as well as the aforementioned thrombotic complications105,106. Myocardial injury, with elevation of cardiac biomarkers above the 99th percentile of the upper reference limit, occurred in 20–30% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, with higher rates (55%) among those with pre-existing cardiovascular disease3,107. A greater frequency and magnitude of troponin elevations in hospitalized patients has been associated with more-severe disease and worse outcomes3,107. Biventricular cardiomyopathy has been reported in 7–33% of critically ill patients with COVID-1952,65. Isolated right ventricular failure with and without confirmed pulmonary embolism has also been reported108,109. Cardiac arrhythmias, including new-onset atrial fibrillation, heart block, and ventricular arrhythmias, are also prevalent, occurring in 17% of hospitalized patients and 44% of patients in the ICU setting in a study of 138 patients from Wuhan, China110. In a multicenter New York City cohort, 6% of 4,250 patients with COVID-19 had prolonged QTc (corrected QT; >500 ms) at the time of admission111. Among 393 patients with COVID-19 from a separate cohort from New York City, atrial arrhythmias were more common among patients who required mechanical ventilation than among those who did not (17.7% versus 1.9%)68. Reports from Lombardi, Italy, show an increase of nearly 60% in the rate of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic relative to a similar time period in 2019, which suggests the etiology to be either COVID-19 or other untreated pathology due to patients’ reluctance to seek care112.

Pathophysiology.

The pathophysiology underlying cardiovascular manifestations is probably multifactorial. ACE2 has high expression in cardiovascular tissue, including cardiac myocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and smooth-muscle cells32,113, in support of a possible mechanism of direct viral injury. Myocarditis is a presumed etiology of cardiac dysfunction, and the development of myocarditis may relate to viral load. While isolation of the virus from myocardial tissue has been reported in a few autopsy studies21,24,99, other pathological reports have described inflammatory infiltrates without myocardial evidence of SARS-CoV-2114,115. Additionally, the finding of direct viral infection of the endothelium and accompanying inflammation, as reported in a patient with circulatory failure and MI, lends credence to the possibility of virus-mediated endothelial-cell damage as an underlying mechanism31. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (cytokine storm) is another putative mechanism of myocardial injury17. Furthermore, patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease may have higher levels of ACE2, which would potentially predispose them to more-severe COVID-19116,117. Moreover, isolated right ventricular dysfunction may occur as a result of elevated pulmonary vascular pressures secondary to ARDS118, pulmonary thromboembolism108,109, or potentially virus-mediated injury to vascular endothelial and smooth-muscle tissue31.

Other potential etiologies of myocardial damage not specific to COVID-19 include severe ischemia or MI in patients with pre-existing coronary artery disease, stress-mediated myocardial dysfunction, tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy, and myocardial stunning after resuscitation or prolonged hypotension.

While patients with viral infections are at risk for MI in general119, this risk may be exaggerated in patients with COVID-19, given reports of disproportionately increased hypercoagulability in affected people, which would lead to a possible increase in thrombotically mediated MI. Moreover, distinguishing the presentation of atherosclerotic plaque-rupture MI from myonecrosis due to supply–demand mismatch (type 2 MI) in the setting of severe hypoxia and hemodynamic instability and myocarditis can be challenging120. This was especially evident in a recent case series of 18 patients with COVID-19 who developed ST-segment elevation on electrocardiogram, 10 of whom were diagnosed with noncoronary myocardial injury78.

Management considerations.

Whether upregulation of ACE2 by ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) is lung protective121,122 or increases susceptibility to infection with SARS-CoV-2123 has been intensely debated within the cardiovascular community61,124. This has implications for patients with hypertension, heart failure, and/or diabetes, who are overrepresented among critically ill patients with COVID-19125. There is no evidence to support an association between the use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs and more-severe disease; some large studies indicate no relationship between the use of these agents and the severity of COVID-19126–128, whereas other data suggest that they may attenuate the severity of disease129–131. Routine discontinuation of these medications is not recommended, as endorsed by the guidelines of several international cardiology societies132,133.

As for the management of ACS, there is guidance available from multiple specialty societies134,135. Although primary percutaneous coronary intervention remains the preferred approach for most patients with ST-segment-elevation MI, fibrinolytic therapy may be appropriate in select patients, especially if personal protective equipment is not available136. Additionally, point-of-care echocardiography may be used to assess regional wall-motion abnormalities to guide decisions about cardiac catheterization. Less-urgent or elective procedures should be deferred in an effort to minimize the risk of viral transmission105,134,135,137. The patient’s baseline QTc interval should be obtained before the administration of any drugs that may lead to prolongation of this interval138. Diagnostic workup of myocardial dysfunction in patients with COVID-19 is challenging, given the sparing use of cardiac imaging, invasive angiography and hemodynamic assessments, and endomyocardial biopsies in consideration of the serious risk of viral infection of patients and healthcare workers and contamination of facilities139,140.

Renal manifestations

A substantial proportion of patients with severe COVID-19 may show signs of kidney damage. Clinical manifestations and management considerations pertaining to the renal system are presented in Box 3.

Box 3 |. Renal manifestations of COVID-19.

Clinical presentations

AKI

Electrolyte abnormalities (hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, and hypernatremia, among others)

Proteinuria

Hematuria

Metabolic acidosis

Clotting of extracorporeal circuits used for RRT

COVID-19-specific considerations

Evaluate urine analysis and protein-to-creatinine ratio at admission, given the association of proteinuria and hematuria with outcomes142,154

Consider empiric low-dose systemic anticoagulation during the initiation and day-to-day management of extracorporeal circuits for RRT157

Consider co-localization of patients who require RRT and use shared RRT protocols156

Consider acute peritoneal dialysis in select patients to minimize personnel requirements156

General considerations

Individualize fluid-balance strategies guided by markers of volume status (serum lactate, urinary electrolytes, and hemodynamic measures), and of pulmonary, myocardial, and renal function

Consider continuous RRT in critically ill patients with severe AKI and/or serious or life-threatening metabolic complications that do not respond to medical therapy

Epidemiology and clinical presentation.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a frequent complication of COVID-19 and is associated with mortality141,142. In China, the reported incidence of AKI in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 ranged from 0.5% to 29% (refs. 2,4,5,142) and occurred within a median of 7–14 days after admission5,142. Studies from the USA have reported much higher rates of AKI. In a study of nearly 5,500 patients admitted with COVID-19 in a New York City hospital system, AKI occurred in 37%, with 14% of the patients requiring dialysis143. About one third were diagnosed with AKI within 24 hours of admission in this study. Of note, these rates are much higher than those reported during the SARS-CoV epidemic144. AKI occurred at much higher rates in critically ill patients admitted to New York City hospitals, ranging from 78% to 90% (refs. 53,54,111,143,145). Of 257 patients admitted to ICUs in a study from New York City, 31% received renal replacement therapy (RRT)54. Furthermore, hematuria has been reported in nearly half of patients with COVID-19143, and proteinuria has been reported in up to 87% of critically ill patients with COVID-1954. Hyperkalemia and acidosis are common electrolyte abnormalities associated with the high cell turnover seen in patients with COVID-19, even among patients without AKI. COVID-19 is also increasingly reported among patients with end-stage renal disease and kidney transplant recipients, with higher mortality rates than those seen in the general population146–148.

Pathophysiology.

Several possible mechanisms specific to SARS-CoV-2 that distinguish this renal abnormality from the more general AKI that accompanies severe illness are noteworthy. First, SARS-CoV-2 may directly infect renal cells, a possibility supported by histopathology findings and the presence of ACE2 receptors23,27,32. Histopathological findings include prominent acute tubular injury and diffuse erythrocyte aggregation and obstruction in peritubular and glomerular capillary loops21,23. Viral inclusion particles with distinctive spikes in the tubular epithelium and podocytes, and endothelial cells of the glomerular capillary loops, have been visualized by electron microscopy21,23,31. Second, the demonstration of lymphocytic endothelialitis in the kidney, in addition to viral inclusion particles in glomerular capillary endothelial cells, suggests that microvascular dysfunction is secondary to endothelial damage31. Third, similar to severe infection with influenza virus, cytokine storm may have an important role in the immunopathology of AKI149. In fact, it has been speculated that this is an underlying mechanism of the clinical ‘viral sepsis’ and multiple-organ dysfunction, including AKI, in patients with COVID-1917. Glomerular injury mediated by immunocomplexes of viral antigen or virus-induced specific immunological effector mechanisms is also plausible, and this is reflected in the development of collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in people infected with SARS-CoV-2 who have two high-risk variants of APOL1 (the gene that encodes apolipoprotein L1)150–152. Finally, while proteinuria is not a typical manifestation of AKI, transient heavy albuminuria might occur secondary to endothelial dysfunction or direct podocyte injury. It is also possible that the pattern of severe proximal-tubular injury leads to a defect in receptor-mediated endocytosis, which results in the observed instances of proteinuria23. Other potential etiologies of AKI common to critical illness presentations, including ARDS, rhabdomyolysis, volume depletion, and interstitial nephritis, all remain relevant in patients with COVID-19153.

Management considerations.

Urine analysis and protein-to-creatinine ratio may be obtained at admission for patients with COVID-19, as proteinuria and hematuria seem to be associated with a more severe clinical course and higher mortality, and this would provide an opportunity for early risk stratification142,154. In patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, an emphasis should be placed on optimization of volume status to prevent prerenal AKI, particularly given the high prevalence of AKI at presentation, while avoiding hypervolemia, which may worsen the patient’s respiratory status. The Surviving Sepsis guidelines for critical illness in COVID-19 recommend a conservative fluid-resuscitation strategy while acknowledging that the supporting evidence base is weak155. A dramatic increase in the need for RRT in critically ill patients may require judicious resource planning, including the use of shared continuous RRT protocols, co-localization of patients, and the utilization of acute peritoneal dialysis in select patients156. The prothrombotic state poses additional challenges in the initiation and maintenance of the extracorporeal circuits needed for RRT. In a multicenter prospective cohort study from four ICUs in France, 97% (28 of 29) patients receiving RRT experienced circuit clotting80. In the absence of contraindications, patients with COVID-19 may require systemic anticoagulation during RRT157.

Gastrointestinal manifestations

COVID-19 may cause gastrointestinal symptoms in some patients. Clinical manifestations and management considerations pertaining to the gastrointestinal system are presented in Box 4.

Box 4 |. Gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary manifestations of COVID-19.

Clinical presentations

Nausea and/or vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, anorexia

Rare cases of mesenteric ischemia and gastrointestinal bleeding

Laboratory markers: elevated hepatic transaminases, elevated bilirubin, low serum albumin

COVID-19-specific considerations

Consider COVID-19 as a differential diagnosis in patients who present with isolated gastrointestinal symptoms in the absence of respiratory symptoms160

If testing resources are scarce, prioritize testing for SARS-CoV-2 among patients who present with both respiratory symptoms and gastrointestinal symptoms162

Use diagnostic endoscopy only for urgent therapeutic reasons (large-volume gastrointestinal bleeding or biliary obstruction)166,167

Monitor hepatic transaminases longitudinally, particularly in patients who are receiving investigational treatments; low-level elevations should not necessarily be considered a contraindication to treatment with these agents174

General considerations

Avoid additional diagnostic tests for aminotransferase elevations less than five times the upper limit of normal unless additional features raise the pre-test probability of actionable findings (hyperbilirubinemia, right upper quadrant pain, hepatomegaly)

Evaluate other etiologies of abnormal liver biochemistries, including infection with other viruses (such as hepatitis A, B, or C viruses), myositis, cardiac injury and ischemia

Epidemiology and clinical presentation.

The incidence of gastrointestinal manifestations has ranged from 12% to 61% in patients with COVID-195,158–161. Gastrointestinal symptoms may be associated with a longer duration of illness but have not been associated with increased mortality158,160. In a recent meta-analysis of 29 studies (of which the majority are from China), the pooled prevalence of individual symptoms was reported, including that of anorexia (21%), nausea and/or vomiting (7%), diarrhea (9%), and abdominal pain (3%)160. In a study from the USA, a higher prevalence of these symptoms was reported (anorexia, 34.8%; diarrhea, 33.7%; and nausea, 26.4%)161. In addition, the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms at presentation was associated with a 70% increased risk of detection of SARS-CoV-2 in a study from a New York City hospital162. Gastrointestinal bleeding was rarely observed in this study, despite presence of traditional risk factors, including prolonged mechanical ventilation, thrombocytopenia, or systemic anticoagulation162.

Pathophysiology.

The pathophysiology of gastrointestinal damage in COVID-19 is probably multifactorial. Virus-mediated direct tissue damage is plausible, given the presence of ACE2 in intestinal glandular cells20,25,163,164, as well as the visualization of viral nucleocapsid protein in gastric, duodenal, and rectal epithelial cells, and glandular enterocytes25. Viral RNA has been isolated from stool, with a positivity rate of 54% (ref. 160). Live viral shedding of infectious virions in fecal matter has been reported even after the resolution of symptoms, and this needs further evaluation as a potential source of transmission25. In addition, histopathological evidence of diffuse endothelial inflammation in the submucosal vessels of the small intestine from patients with COVID-19 and mesenteric ischemia suggests microvascular small-bowel injury31. Support for inflammation-mediated tissue damage is provided by the presence of infiltrating plasma cells and lymphocytes and of interstitial edema in the lamina propria of the stomach, duodenum, and rectum of patients25. It has also been hypothesized that alteration of the intestinal flora by the virus may contribute to gastrointestinal symptoms and severe disease progression165.

Management considerations.

Current multi-society guidelines emphasize the avoidance of diagnostic endoscopy for non-urgent reasons during the COVID-19 pandemic166,167. Most practitioners reserve procedures for patients with COVID-19 to those for whom therapeutic intervention is necessary due to large-volume upper gastrointestinal bleeding or biliary obstruction. During the COVID-19 pandemic at a New York City hospital, upper endoscopy was performed at lower-than-usual hemoglobin levels and after transfusion of larger volumes of packed red blood cells168. Interestingly, this was seen both in patients testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 and in those testing negative, probably reflective of a reluctance to perform endoscopy for the former group and reluctance of the latter group to come to the hospital. Patients who do present with gastrointestinal symptoms and later test positive for SARS-CoV-2 have been reported to experience delays in diagnosis160. When feasible, COVID-19 should be considered as a differential diagnosis in these patients even in absence of respiratory symptoms. In resource-limited settings, patients with symptoms of diarrhea or nausea and/or vomiting in addition to respiratory symptoms should be prioritized for testing162.

Hepatobiliary manifestations

Signs of hepatobiliary damage may be observed in patients with severe presentations of COVID-19. Clinical manifestations and management considerations pertaining to the hepatobiliary system are presented in Box 4.

Epidemiology and clinical presentation.

In critically ill patients with COVID-19, a hepatocellular injury pattern is seen in 14–53% of hospitalized patients2,4,5,65,66. Aminotransferases are typically elevated but remain less than five times the upper limit of normal. Rarely, severe acute hepatitis has been reported169,170. A recent systematic review incorporating 12 studies reported a pooled prevalence of liver function abnormalities at 19% (95% confidence interval, 9–32%) with an association with disease severity160. Elevated bilirubin at hospital admission has also been linked to disease severity and progression to critical illness in a few studies171,172, although the association of longitudinal changes in bilirubin with prolonged ARDS is currently unclear.

Pathophysiology.

SARS-CoV-2 may directly damage the biliary ducts by binding to ACE2 on cholangiocytes170. Hyperinflammation seen with cytokine storm and hypoxia-associated metabolic derangements are other potential mechanisms of liver damage17. Drug-induced liver injury, particularly secondary to investigational agents such as remdesivir, lopinavir, and tocilizumab, may also occur17,159,173. In a prospective clinicopathologic series of 11 patients from Austria, Kupffer cell proliferation was seen in all patients, and chronic hepatic congestion was seen in 8 patients. Other histopathologic changes in the liver included hepatic steatosis, portal fibrosis, lymphocytic infiltrates and ductular proliferation, lobular cholestasis, and acute liver-cell necrosis, together with central-vein thrombosis98.

Management considerations.

In accordance with guidelines issued by an expert panel of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, additional diagnostic tests are not recommended for aminotransferase elevations unless additional features raise the probability of findings that require further measures (such as hyperbilirubinemia, right-upper-quadrant pain, and hepatomegaly)174. Other COVID-19-related etiologies of elevated liver biochemistries, including myositis, cardiac injury (in conjunction with troponin elevation), ischemia, cytokine-release syndrome, and co-infection with other viruses, should be considered. Longitudinal monitoring of hepatic transaminases is recommended, particularly in patients receiving investigational treatments, including remdesivir, lopinavir, and tocilizumab, although low-level elevations should not necessarily be considered a contraindication to treatment with these agents174.

Endocrinologic manifestations

While patients with pre-existing endocrinologic disorders may be predisposed to more-severe presentations of COVID-19, observations of a range of endocrinologic manifestations in patients without pre-existing disease have also been made. Clinical findings and management considerations relating to the endocrinologic system are presented in Box 5.

Box 5 |. Endocrine manifestations of COVID-19.

Clinical presentations

Hyperglycemia

Ketoacidosis, including that in patients with previously undiagnosed diabetes or no diabetes

Euglycemic ketosis

Severe illness in patients with pre-existing diabetes and/or obesity

COVID-19-specific considerations

Consider checking serum ketones in patients with hyperglycemia who are on sodium–glucose transport protein inhibitors177

Measure hemoglobin A1C in patients without known history of diabetes mellitus who present with hyperglycemia and/or ketoacidosis

Consider alternative protocols for subcutaneous insulin in selected patients with mild to moderate diabetic keotacidosis on an individual-patient-level basis192.

General considerations

Identify and initiate prompt treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis with standard protocols in the setting of hyperglycemia

Consider continuous glucose monitors for patients who require an insulin drip (to avoid hourly glucose checks)

Consider increased insulin dosing in patients being treated with steroids

Avoid oral hypoglycemic agents due to potential concerns for concurrent renal damage (metformin, thiazolidinediones), euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis (sodium–glucose transport protein inhibitors), cardiac and hypoglycemic complications (sulfonylureas), reduced gastric emptying and reduced gastrointestinal motility that may cause aspiration if patients require intubation (glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists)

Epidemiology and clinical manifestations.

Patients with diabetes mellitus and/or obesity are at risk of developing more-severe COVID-19 illness125. In a report from the US Centers for Disease Control, 24% of hospitalized patients and 32% of patients admitted to the ICU had underlying diabetes125. In an initial experience with 257 critically ill patients hospitalized in a tertiary-care hospital in New York City, 36% had diabetes and 46% were obese54. Similar observations were made in studies from China and Italy that demonstrated an association of underlying diabetes with severe illness and death2,175,176. Moreover, patients hospitalized with COVID-19 have exhibited a range of abnormalities of glucose metabolism, including worsened hyperglycemia, euglycemic ketosis, and classic diabetic ketoacidosis. In a retrospective study from China, among a group of 658 patients hospitalized with COVID-19, 6.4% presented with ketosis in the absence of fever or diarrhea177. Of these, 64% did not have underlying diabetes (with an average hemoglobin A1c level of 5.6% in this group).

Pathophysiology.

Several mechanisms may account for the more severe disease course, including worsened hyperglycemia and ketosis, observed in patients with COVID-19 and diabetes. Factors related to SARS-CoV-2 include substantially elevated cytokine levels, which may lead to impairments in pancreatic β-cell function and apoptosis178 and, consequently, decreased insulin production and ketosis. In addition, ACE2 expression has been reported in the endocrine pancreas179,180, albeit inconsistently181. This raises the possibility that direct binding of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2 on β-cells might contribute to insulin deficiency and hyperglycemia, as has been shown previously for infection with SARS-CoV179. Accelerated fat breakdown in patients with COVID-19 has also been proposed as a possible mechanism, but this requires further investigation177. Factors not specific to COVID-19 in patients with diabetes and infections include an altered immune response182–184 and an increase in counter-regulatory hormones that promotes hepatic glucose production, decreased insulin secretion, ketogenesis, and insulin resistance185,186. Key extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19 can also be interlinked with diabetic complications, from reduced renal function to pro-thrombotic and coagulopathic states, to cardiac dysfunction and hepatocyte injury187.

Obesity is another risk factor for more-severe illness in COVID-19188. This may be related to its effects on pulmonary function, such as reduced lung volumes and compliance, and an increase in airway resistance, as well as an association with diabetes189,190. In addition, increased adiposity has been linked with alterations in multiple cytokines, chemokines, and adipokines, including increased pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL-6, IL-8, leptin, and adiponectin189–191, which all potentially exacerbate the exuberant inflammatory response seen in this disease.

Management considerations.

Hemoglobin A1C should be assessed in patients with COVID-19 who present with hyperglycemia and/or ketoacidosis, to identify possibly undiagnosed diabetes. Logistically, the management of diabetic ketoacidosis poses an increased risk to medical personnel, due to the need for hourly glucose checks while patients are on an insulin drip. There may be a role for remote glucose monitoring via continuous glucose monitors to alleviate this problem and reduce demands on nursing staff. Alternative protocols for subcutaneous insulin in selected groups of patients with mild to moderate diabetic ketoacidosis may be considered on an individual patient-level basis192.

Neurologic and ophthalmologic manifestations

There is growing evidence of neurologic complications of COVID-19. Neurologic and ophthalmologic manifestations of COVID-19 and management considerations are summarized in Box 6.

Box 6 |. Neurologic and ophthalmologic manifestations of COVID-19.

Clinical presentations

Headache, dizziness

Anosmia, ageusia, anorexia, myalgias, fatigue

Stroke

Encephalopathy, encephalitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy

Conjunctivitis

COVID-19-specific considerations

Continue adherence to established guidelines for acute ischemic stroke, including thrombolysis and thrombectomy209

Adapt post-acute-care monitoring guidelines for pandemic constraints (most stable patients do not need to be monitored in an ICU for 24 hours)210

Use remote video evaluation, whenever possible, for hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who have symptoms that are of concern for a stroke

Consider extended-interval or delayed dosing of chronic immunomodulatory therapies in conditions such as multiple sclerosis during COVID-19211

General considerations

Monitor closely for changes in baseline symptoms for vulnerable populations such as elderly patients with Parkinson’s disease

Promptly evaluate any changes in the neurological exam of a hospitalized patient

Evaluate the risk/benefit balance of off-label uses of tissue plasminogen activator and the empiric use of anticoagulation in critically ill patients (risk of intracranial bleeding and hemorrhagic conversion of stroke)

Epidemiology and clinical presentation.

Similar to SARS and Middle East respiratory syndrome193,194, multiple neurological manifestations of COVID-19 have been described. An analysis of 214 patients with severe COVID-19 found that neurologic symptoms occurred in 36% of the patients195. A number of non-specific mild neurological symptoms are notable in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, including headache (8–42%), dizziness (12%), myalgia and/or fatigue (11–44%), anorexia (40%), anosmia (5%), and ageusia (5%)69,75,110, although the epidemiology may be different in milder outpatient presentations2,196,197. More-severe presentations of COVID-19 manifest with acute stroke of varying arterial and venous mechanisms (in up to 6% of those with severe illness)81,198, and confusion or impaired consciousness (8–9%)195,199. Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (Guillain-Barré syndrome) has also been reported in some patients200,201. In addition, meningoencephalitis79, hemorrhagic posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome202, and acute necrotizing encephalopathy, including the brainstem and basal ganglia, have been described in case reports203,204. Ocular manifestations, such as conjunctival congestion alone, conjunctivitis, and retinal changes205, have also been reported in patients with COVID-192,206,207.

Pathophysiology.

SARS-CoV and the coronavirus that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome have known neuroinvasive and neurotropic abilities193,194. Direct viral invasion of neural parenchyma is a possibility; SARS-CoV-2 may access the central nervous system via the nasal mucosa, lamina cribrosa, and olfactory bulb or via retrograde axonal transport. Nasal epithelial cells display the highest expression of ACE2 (the receptor for SARS-CoV-2) in the respiratory tree18,28; this may account for the symptoms of altered sense of taste or smell frequently reported retrospectively in the majority of outpatients with COVID-19196,197,208. Other neurological manifestations support, at least, the neurovirulence of COVID-19, perhaps reflecting the proinflammatory and prothrombotic cascade in the wake of cytokine storm30,55 as it affects brain vasculature and the blood–brain barrier, especially in the setting of toxic-metabolic sequelae of multi-organ dysfunction often seen in COVID-19-associated critical illness.

Management considerations.

Provisional guidelines during the COVID-19 crisis call for continued adherence to established guidelines for acute ischemic stroke, including providing access to thrombolysis and thrombectomy, while recognizing the need to minimize the use of personal protective equipment209. Post-acute-care monitoring guidelines may be adjusted for pandemic constraints210. The liberal use of ‘telestroke’, or remote video evaluation of patients who have had a stroke, which has been a mainstay of stroke care for hospitals without access to specialists for many years, is also recommended and may have a role even within large hospitals. Potent baseline immunomodulatory therapies may be considered for extended-interval or delayed dosing in conditions such as multiple sclerosis during COVID-19211. Long-term considerations, such as post-infectious neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory involvement, as well as the efficacy of an eventual vaccine in some immunosuppressed populations, are under investigation.

Dermatologic manifestations

Dermatologic manifestations have occasionally been described in patients suffering from COVID-19.

Epidemiology and clinical presentation.

The dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19 were first reported in a single-center observational study in Italy, with a frequency of 20% in hospitalized patients with no history of drug exposure in the previous 2 weeks212. Approximately 44% of the patients had cutaneous findings at disease onset, while the remaining patients developed these during the course of their illness. No correlation with disease severity was noted in this small study. The cutaneous manifestations included erythematous rash, urticaria, and chickenpox-like vesicles. A preliminary systematic review of 46 studies (including case reports and series) found acro-cutaneous (pernio or chilblain-like) lesions to be the most commonly reported skin manifestation213. Other cutaneous findings included maculopapular rash, vesicular lesions, and livedoid and/or necrotic lesions. A transverse study included in this systematic review found chilblain-like lesions to be associated with less-severe COVID-19, while livedoid and/or necrotic lesions were seen in more-severe COVID-19214. Case reports have also described exanthematous rashes and petechiae in COVID-19215–217.

Pathophysiology.

Drug exposure and temporal association with hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, tocilizumab, and other experimental drugs should always be evaluated before any skin lesion is attributed to the viral infection218. Potential mechanisms for COVID-19-related cutaneous manifestations include an immune hypersensitivity response to SARS-CoV-2 RNA, cytokine-release syndrome, deposition of microthrombi, and vasculitis219. Superficial perivascular dermatitis and dyskeratotic keratinocytes have been most commonly described from histopathological examination of skin rashes215,220. Biopsy of acrocutaneous lesions has shown diffuse and dense lymphoid infiltrates, along with signs of endothelial inflammation220. Small thrombi in vessels of the dermis have occasionally been seen215.

Management considerations.

Most cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 have been self-resolving. It is not clearly understood whether patients with dermatologic diseases who receive biologic therapies are at increased risk of complications from COVID-19221. In their interim guidelines, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends discontinuation of biologic therapy in COVID-19-positive patients (similar to recommendation for patients with other active infections) and recommends case-by-case discussion about the continuation of these drugs for at-risk patients222.

Special considerations in COVID-19

Here we review the epidemiological and clinical features of pediatric and pregnant patients with COVID-19.

Children.

Epidemiology and clinical presentation.

In a review of 72,314 patients with COVID-19 reported by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, less than 1% of the patients were younger than 10 years of age176. In two retrospective studies from China, of >1,000 pediatric patients with COVID-19, the majority of the patients had mild or moderate disease, and only 1.8% required ICU admission, with two reported deaths223,224. In a recent study from a large group of North American pediatric ICUs, however, 38% of 48 critically ill children required invasive ventilation, with an in-hospital mortality rate of 4.2% (ref. 225).

In the later phase of the pandemic, reports of healthy children presenting with a severe inflammatory shock that had features similar to those of atypical Kawasaki disease or toxic-shock syndrome were highlighted by physicians in Europe and the USA226,227. This syndrome was recognized as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and was defined as follows: a person <21 years of age presenting with fever, laboratory evidence of inflammation, and evidence of clinically severe illness requiring hospitalization, with multisystem (two or more) organ involvement in the setting of current or recent infection with SARS-CoV-2. If untreated, Kawasaki disease can result in coronary aneurysms in 25% of patients228.

Pathophysiology.

Potential reasons for less-severe manifestations of COVID-19 in children include the evolution of ACE2 expression229 and T cell immunity and a pro-inflammatory cytokine milieu230 with age. The possibility of competition between SARS-CoV-2 and other pre-existing viruses that are common in the respiratory mucosa of young children has been hypothesized as well230. In contrast, increased ACE2 expression around birth, before its decrease, and a reduced ability of T cells to fight viral infections at birth may be responsible for the susceptibility of infants to severe COVID-19230. Interestingly, many children with MIS-C tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 but positive for antibodies, suggestive of a likely trigger from the development of acquired immunity rather than direct viral injury as the underlying mechanism.

Management considerations.

The majority of patients with MIS-C required vasopressor support, and few required mechanical circulatory support, in experience from New York hospitals. Due to some similarities with Kawasaki disease, treatment strategies have included intravenous immunoglobulin and corticosteroids, and occasionally an IL-1 antagonist (anakinra)227,231. Treatment with aspirin or lovenox has also been debated, given the hypercoagulable state and concern for coronary involvement similar to that of Kawasaki disease. Other medical therapies that have been extrapolated from studies of adults include compassionate use of the anti-viral drug remdesivir and the IL-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab232,233.

Pregnant women.

Epidemiology.

Pregnancy and childbirth have not been shown to substantially alter susceptibility to or the clinical course of infection with SARS-CoV-2234–236. Preliminary data indicate that rates of ICU admission for pregnant women are similar to those of the nonpregnant population176,237. Pregnant women with COVID-19 have not been reported to have severe maternal complications but were noted to be at increased risk of preterm and cesarean delivery in a few studies235,238,239. Maternal deaths from cardiopulmonary complications and multi-organ failure in previously healthy women have also been reported240,241. Evidence for vertical transmission to neonates has been mixed so far, which suggests that vertical transmission is possible but is probably not a common occurence242–244.

Pathophysiology.

It is unknown whether the normal immunological changes of pregnancy affect the severity of COVID-19 illness, a disease marked by hyperinflammation in its severe forms. Histopathological evidence of infection of placental and fetal membrane samples with SARS-CoV-2 has been reported in a few cases245,246, but so far, vaginal and amniotic samples have tested negative in pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2247.

Management.

The management of hospitalized pregnant women is not substantially different from that of non-pregnant people. Changes to the route of delivery or management of labor are not routinely recommended for pregnant patients with COVID-19248.

Conclusions and future directions

Beyond the life-threatening pulmonary complications of SARS-CoV-2, the widespread organ-specific manifestations of COVID-19 are increasingly being appreciated. As clinicians around the world brace themselves to care for patients with COVID-19 for the foreseeable future, the development of a comprehensive understanding of the common and organ-specific pathophysiologies and clinical manifestations of this multi-system disease is imperative. It is also important that scientists identify and pursue clear research priorities that will help elucidate several aspects of what remains a poorly understood disease. Some examples of areas that require further attention include elucidation of the mechanism by which SARS-CoV-2 is disseminated to extrapulmonary tissues, understanding of the viral properties that may enhance extrapulmonary spread, the contribution of immunopathology and effect of anti-inflammatory therapies, anticipation of the long-term effects of multi-organ injury, the identification of factors that account for the variability in presentation and severity of illness, and the biological and social mechanisms that underlie disparities in outcomes. A number of organ-system-specific research questions are summarized in Table 1. There is also a need for common definitions and data standards for research relating to COVID-19. Regional, national, and international collaborations of clinicians and scientists focused on high-quality, transparent, ethical, and evidence-based research practices would help propel the global community toward achieving success against this pandemic.

Table 1 |.

Future directions for research pertaining to various organ systems affected by COVID-19

| General | |

|

| |

| Pathophysiological | Clinical |

|

| |

| • How long does infectious SARS-CoV-2 persist in the upper airway of an infected patient? • How does SARS-CoV-2 disseminate in extrapulmonary tissues? Is hematogenous spread of the virus required for the direct cytotoxic effects to occur? • Do other organs serve as sites of viral infection and persistence? • Is extrapulmonary involvement dependent on viral load? • Is extrapulmonary involvement dependent on mutations of SARS-CoV-2 or ACE2 polymorphisms? • What role do host factors such as genetics (Toll-like receptors or complement components) or post-transcriptional modifications have in extrapulmonary SARS-CoV-2 infection? Are there biologically relevant factors (in addition to social factors) that explain the observed race disparities in incidence and outcomes? • What is the predominant mechanism underlying the multiple organ dysfunction; is it direct virus-induced tissue damage, systemic cytokine-release syndrome, or the synergistic effects of both? What is the role of other proposed mechanisms such as RAAS dysregulation and endothelialitis? |

• What is the impact of COVID-19 on the capacity to care for competing patients without COVID-19? • What is the efficacy, safety, and proper timing for the use of antiviral and anti-inflammatory therapies currently under investigation? • How should these therapies be best used in conjunction with each other to maximize efficacy while considering safety profiles? • Is there a role for recombinant ACE2 in treatment of patients with COVID-19? |

|

| |

| Hematologic | |

|

| |

| Pathophysiological | Clinical |

| • What are the mechanisms of viral entry into lymphocytes? • Does SARS-CoV-2 exert direct effects on coagulation and complement pathways, and if so, which ones? • In addition to IL-6, which cytokines and chemokines may act as therapeutic targets for COVID-19? • How is interferon signaling modulated by SARS-CoV-2? Are there differences in interferon responses in the early stages versus the late stages of COVID-19? |

• Do novel measurements of hypercoagulability offer improved assessment of thrombotic risk? • Is there a role for empiric higher-intensity (prophylactic or therapeutic dose) anticoagulation in patients who do not have documented thromboembolic events? • Does post-hospitalization extended thromboprophylaxis improve patient outcomes? • Does targeting inflammatory pathways and cytokine storm result in a reduction in the rate of thrombotic complications in COVID-19? • Which patients, if any, would benefit from empiric thrombolytic therapy? |

|

| |

| Cardiovascular | |

|

| |

| Pathophysiological | Clinical |

| • Does direct cardiac viral toxicity contribute substantially to myocardial dysfunction? • Are the mechanisms that result in myocardial injury and MI substantially different from those that are observed with other viral and bacterial infections? • What are the mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias in patients with COVID-19? |

• What is the optimal antithrombotic regimen (including antiplatelets and anticoagulants) in patients presenting with COVID-19 with evidence of myocardial injury or MI? • Do statins have a protective role in patients with COVID-19, given the ability of statins to downregulate ACE2, as well as their anti-inflammatory and other pleiotropic effects? • Among the patients who develop right ventricular dysfunction in COVID-19, what proportion have pulmonary embolism and what proportion are due to the development of pulmonary hypertension or isolated right ventricular failure due to other causes? • What strategies should be used to assess and treat acute right ventricular dysfunction in patients with COVID-19 without pulmonary embolism? Can this dysfunction be temporized with mechanical circulatory support or pulmonary vasodilators? |

|

| |

| Renal | |

|

| |

| Pathophysiological | Clinical |

| • How does SARS-COV-2 induce renal tubular injury? • What is the mechanism of the development of electrolyte abnormalities and proteinuria in patients with COVID-19? • Does SARS-CoV-2 act as a 'second hit' that potentiates the glomerular damage attributed to APOL1 risk genotypes, as seen with development of collapsing-variant focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in some cases? |

• What is the optimal volume-management strategy in patients with COVID-19 who are at high risk of AKI, while also at risk of ARDS and myocardial injury? • What is the frequency of renal recovery in patients who develop renal failure? • Is there a role for cytokine removal through hemofiltration in patients with severe COVID-19? |

|

| |

| Gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary | |

|

| |

| Pathophysiological | Clinical |

| • What is the duration and extent of fecal shedding of SARS-CoV-2? • Does fecal shedding have a role in viral transmission? • What is the role of intestinal entry by the virus? Can the microbiome alter susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection? • What are the predominant mechanisms of hepatocellular damage in COVID-19? |

• Do the hematologic abnormalities associated with COVID-19 increase the likelihood of developing gastrointestinal bleeding? How can this risk be best balanced with the risk for coagulopathy and thrombotic complications? • Do antihistaminic agents (e.g., famotidine) have a role in prophylaxis against gastrointestinal pathology, including bleeding events? Do these agents have antiviral efficacy against SARS-CoV-2? |

|

| |

| Endocrinologic | |

|

| |

| Pathophysiological | Clinical |

| • Is the COVID-19-induced metabolic disarray a direct consequence of viral action? • Does SARS-CoV-2 cause metabolic disarray by indirect effects such as altered nutrient utilization, cytokines and inflammation, and counter-regulatory hormones? • Is ACE2 expressed uniformly in pancreatic β-cells and endocrine islets? • If there is evidence of direct viral damage in pancreas, what is the nature of islet damage? • Is there evidence of impairment of insulin action in patients with COVID-19? |

• Do metabolic differences contribute to the racial disparities seen with COVID-19? • Do the anti-inflammatory properties of agents used to treat diabetes mellitus or metabolic syndrome (e.g., metformin) have a protective effect in patients with COVID-19 and stable renal function? |

|

| |

| Neurologic | |

|

| |

| Pathophysiological | Clinical |

| • Does SARS-CoV-2 directly infect neurons, and if so, which neuron types? • Does SARS-CoV-2 have a tropism for the brainstem and its medullary respiratory centers, and does this contribute to respiratory failure? |

• Do the neurologic and neuroimaging features of stroke differ in patients with COVID-19? • Are there long-term neurological complications in people who recover from SARS-CoV-2 infection? |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge BioRender for design support for Fig. 1 and Julie Der-Nigoghossian for design support for Fig. 2. M. V. M. is supported by an institutional grant by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the US National Institutes of Health to Columbia University Irving Medical Center (T32 HL007854). E. Y. W. is supported by the US National Institutes of Health (K08HL122526, R01HL152236, and R03HL146881). D. E. F. is funded in part by US National Institutes of Health grant K23 DK111847 and by Department of Defense funding PR181960. A. S. N. is supported by National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant 5T32 NS007153. J. M. B. is supported by the National Institutes of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01 AR050026 and U01AR068043). S. M. is supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney grants R01-DK114893, R01-MD014161, and U01-DK116066.

Footnotes

Competing interests

A. G. received payment from the Arnold & Porter Law Firm for work related to the Sanofi clopidogrel litigation and from the Ben C. Martin Law Firm for work related to the Cook inferior vena cava filter litigation; received consulting fees from Edward Lifesciences; and holds equity in the healthcare telecardiology startup Heartbeat Health. B. B. reports being a consulting expert, on behalf of the plaintiff, for litigation related to a specific type of inferior vena cava filter. A. J. K. reports institutional funding to Columbia University and/or the Cardiovascular Research Foundation from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, CSI, Philips, and ReCor Medical. J. M. B. reports an honorarium for participation on a grants review panel for Gilead Biosciences. D. A. is founder, director, and chair of the advisory board of Forkhead Therapeutics. H. M. K. works under contract with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to support quality measurement programs; was a recipient of a research grant, through Yale University, from Medtronic and the US Food and Drug Administration to develop methods for post-market surveillance of medical devices; was a recipient of a research grant with Medtronic and is the recipient of a research grant from Johnson & Johnson, through Yale University, to support clinical trial data sharing; was a recipient of a research agreement, through Yale University, from the Shenzhen Center for Health Information for work to advance intelligent disease prevention and health promotion; collaborates with the National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases in Beijing; receives payment from the Arnold & Porter Law Firm for work related to the Sanofi clopidogrel litigation, from the Ben C. Martin Law Firm for work related to the Cook Celect IVC filter litigation, and from the Siegfried and Jensen Law Firm for work related to Vioxx litigation; chairs a Cardiac Scientific Advisory Board for UnitedHealth; was a participant or participant representative of the IBM Watson Health Life Sciences Board; is a member of the advisory board for Element Science, the advisory board for Facebook, and the physician advisory board for Aetna; and is the co-founder of HugoHealth (a personal health information platform) and co-founder of Refactor Health (an enterprise healthcare AI-augmented data enterprise). M. R. M. reports consulting relationships with Abbott, Medtronic, Janssen, Mesoblast, Portola, Bayer, NupulseCV, FineHeart, Leviticus, Roivant, and Triple Gene. D. W. L. is the chair of the scientific advisory board for Applied Therapeutics, licensor of Columbia University technology unrelated to COVID-19 or COVID-19-related therapies.

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3.

References

- 1.Dong E, Du H & Gardner L An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 533–534 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guan WJ et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1708–1720 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi S et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou F et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 395, 1054–1062 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu C et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern. Med. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou P et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579, 270–273 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes KV SARS coronavirus: a new challenge for prevention and therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1605–1609 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lan J et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 581, 215–220 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shang J et al. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 581, 221–224 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walls AC et al. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell 181, 281–292.e286 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li W et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 426, 450–454 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann M et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181, 271–280.e8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li F, Li W, Farzan M & Harrison SC Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science 309, 1864–1868 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wrapp D et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 367, 1260–1263 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Q et al. Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell 181, 894–904.e9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lei C et al. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudotyped virus by recombinant ACE2-Ig. Nat. Commun. 11, 2070 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H et al. SARS-CoV-2 and viral sepsis: observations and hypotheses. Lancet 395, 1517–1520 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sungnak W et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat. Med. 26, 681–687 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao W & Li T COVID-19: towards understanding of pathogenesis. Cell Res. 30, 367–369 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wölfel R et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature 581, 465–469 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puelles VG et al. Multiorgan and renal tropism of SARS-CoV-2. N. Engl. J. Med. 10.1056/NEJMc2011400 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang W et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 323, 1843–1844 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su H et al. Renal histopathological analysis of 26 postmortem findings of patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int. 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.003 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tavazzi G et al. Myocardial localization of coronavirus in COVID-19 cardiogenic shock. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 22, 911–915 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao F et al. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology 158, 1831–1833.e3 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qi F, Qian S, Zhang S & Zhang Z Single cell RNA sequencing of 13 human tissues identify cell types and receptors of human coronaviruses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 526, 135–140 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]