Abstract

Objective

This network meta-analysis (NMA) aimed to compare the efficacy of various physical modalities in alleviating pain, stiffness, and functional impairment in patients with knee osteoarthritis (KOA).

Methods

In accordance with PRISMA-P guidelines, we systematically searched nine databases(CNKI, VIP Database, Wanfang Database, SinoMed, PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library) from inception to October 2024 to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating physical therapies for KOA. The interventions assessed included electrical stimulation therapy (EST), low-level light therapy (LLLT), thermotherapy (TT), cryotherapy (CT), and extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT), with resistance and range of motion exercises (RRE) serving as comparators. Outcome measures comprised the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), and 6-minute walk test (6 MWT). Bayesian network meta-analyses and pairwise meta-analyses were performed using Stata 17.0 and R 4.4.1 software.

Results

32 RCTs involving 2,078 participants were included. LLLT demonstrated the highest efficacy for pain reduction (VAS: MD=–3.32, 95% CI:–3.82 to–0.75; WOMAC pain: MD=–3.74, 95% CI:–6.68 to–0.72) and joint function improvement (SUCRA = 79.8). ESWT ranked second for pain relief (VAS: MD=–1.31, 95% CI:–2.42 to–0.16) and mobility enhancement (6 MWT: SUCRA = 71.5), while TT showed superior efficacy in reducing stiffness (WOMAC stiffness: MD=–2.09, 95%CI:–3.06 to–0.94; SUCRA = 98.1). In contrast, ultrasonic therapy (UT) did not provide significant benefits.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that LLLT and ESWT may be optimal for pain relief and functional improvement in patients with KOA, whereas TT appears to be the most effective in reducing stiffness. Optimal dosing parameters of these physical modalities are crucial for maximizing clinical benefits. Clinicians should individualize treatment strategies based on patient-specific factors. Future large-scale RCTs are warranted to validate these protocols and address the heterogeneity of existing evidence.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40520-025-03015-6.

Keywords: Knee osteoarthritis, Physical modalities therapy, Network meta-analysis, Pain relief, Joint function

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a degenerative joint disease characterized by progressive cartilage loss, remodeling of the subchondral bone, and synovial inflammation, and is one of the most common causes of disability in older adults. Its clinical features, which include chronic pain, stiffness, and diminished joint function, substantially impair quality of life [1–3]. Epidemiological studies indicate that approximately 13–15% of individuals aged ≥ 40 years are affected by KOA, with prevalence rates exceeding 30% among those aged ≥ 65 years, particularly in women [4, 5]. Given the aging global population, the burden of KOA is expected to increase, underscoring the urgent need for effective therapeutic strategies [6, 7].

Current management approaches for KOA primarily focus on symptom relief through pharmacological intervention. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, and analgesics are widely prescribed because of their rapid analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects [8–10]. However, these treatments do not modify the underlying disease progression and are associated with dose-dependent adverse effects such as gastrointestinal complications (e.g., ulcers), cardiovascular risks, and renal impairment, particularly with long-term use [11, 12]. These limitations have prompted interest in alternative methods, including minimally invasive and nonpharmacological techniques.

Minimally invasive therapies, such as intra-articular hyaluronic acid (HA) injections, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), and radiofrequency ablation, are designed to provide sustained symptom relief by directly addressing the joint pathology. Although HA injections are recommended by some clinical guidelines, their efficacy has been inconsistent, with meta-analyses reporting only modest improvements in pain and function compared to placebo [13, 14]. Similarly, PRP therapy has produced heterogeneous outcomes, likely owing to differences in preparation protocols and patient selection [15]. Furthermore, although radiofrequency ablation may attenuate nociceptive signaling, its invasive nature and associated risks, including infection and nerve damage, limit its broader adoption [16]. Cost-effectiveness analyses have also raised concerns regarding the long-term value of these interventions, especially in resource-limited settings [17].

In contrast, physical modalities offer noninvasive and cost-effective alternatives with favorable safety profiles. Techniques such as low-level laser therapy (LLLT), extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT), and thermotherapy (TT) target pain pathways by modulating inflammatory cytokines, enhancing tissue perfusion, and promoting mechanotransduction-mediated cartilage repair [18, 19]. Clinical trials have suggested that these modalities can effectively improve pain, stiffness, and functional capacity in KOA [20, 21]. However, the comparative effectiveness of these physical therapies remains unclear because of heterogeneous study designs, variable treatment parameters, and lack of direct comparison trials [22, 23].

To address these gaps, this network meta-analysis (NMA) synthesized evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to evaluate the relative efficacy of various physical modalities in managing KOA. The analysis focused on validated endpoints: pain reduction as measured by the visual analog scale (VAS), functional improvement as assessed by the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), and mobility as evaluated by the 6-minute walk test (6 MWT). By reconciling inconsistencies in the literature and providing hierarchical rankings of interventions, our findings aim to inform evidence-based clinical decision making and optimize therapeutic strategies for KOA.

Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-P guidelines for network meta-analyses [24]. The study protocol was prospectively registered in the PROSPERO database (registration number CRD42024601821).

Literature search

A systematic search was conducted in nine Chinese and English databases, including the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), VIP Chinese Science and Technology Journal Database, Wanfang Database, Chinese Biomedical Literature Service System (SinoMed), PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library. The search covered studies published from the inception of each database until October 20, 2024. The strategy combined MeSH terms with entry terms and employed keywords such as “Physical Therapy Modalities” “Osteoarthritis, Knee” “KOA” “Electric Stimulation Therapy” “Low-Level Light Therapy” and “Ultrasonic Therapy” among others. A representative search strategy for PubMed is provided in Table 1, and the complete search strings for all the databases are available in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1.

Search strategy (taking pubmed as an example)

| Steps | Search terms |

|---|---|

| #1 | “Physical Therapy Modalities“[MeSH Terms] |

| #2 | “Physical Modality Therapy“[Title/Abstract] OR “Electric Stimulation Therapy“[Title/Abstract] OR “Low-Level Light Therapy“[Title/Abstract] OR “Ultrasonic Therapy“[Title/Abstract] OR “Cryotherapy“[Title/Abstract] OR “Hyperthermia, Induced“[Title/Abstract] OR “Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy“[Title/Abstract] OR “Whole-Body Vibration” [Title/Abstract] |

| #3 | #1 OR #2 |

| #4 | “Osteoarthritis, Knee” [MeSH Terms] |

| #5 | “Knee Osteoarthritides“[Title/Abstract] OR “Knee Osteoarthritis“[Title/Abstract] OR “Osteoarthritis of the Knee“[Title/Abstract] OR “Osteoarthritis of Knee“[Title/Abstract] OR “Gonarthrosis“[Title/Abstract] |

| #6 | #4 OR #5 |

| #7 | #3 AND #6 |

Study selection

This review adhered to the PICOS framework to establish the eligibility criteria for the study. The studies included adult patients with a clinical diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis, with no restrictions on race, sex, age, or symptom duration. The intervention group received physical modality therapy, whereas the control group underwent routine rehabilitation exercises (RRE) or an alternative physical modality different from that used in the intervention group. Physical modalities examined included electrical stimulation therapy (EST), low-level light therapy (LLLT), ultrasonic therapy (UT), cryotherapy (CT), thermotherapy (TT), extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT), and whole-body vibration therapy (WBVT) (Table 2). Outcomes were assessed using the VAS, WOMAC, and 6 MWT. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included. Studies were excluded if they were duplicates, were published in languages other than Chinese or English, contained duplicate data, did not assess relevant outcome measures, had incomplete or unreported data, or lacked full-text availability.

Table 2.

Overview of treatment groups

| RRE | Routine Rehabilitation Exercises |

|---|---|

| EST | Electric Stimulation Therapy |

| LLLT | Low-Level Light Therapy |

| UT | Ultrasonic Therapy |

| CT | Cryotherapy |

| TT | Thermotherapy |

| ESWT | Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy |

| WBVT | Whole-Body Vibration Therapy |

| EST_UT | Combined use of Electric Stimulation Therapy and Ultrasonic Therapy |

Data extraction

The literature retrieved from the electronic searches was imported into Note Express (Version 4.0.0.9855) for management. Duplicate records were removed first, followed by title and abstract screening based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full-text reviews were conducted for the studies that met the eligibility criteria. Two researchers (Xiangzhou Lan and Lingjia Li) independently performed the screening, with discrepancies resolved by a third researcher (Weike Zeng). Following the final selection, the two researchers extracted relevant data, including the author, publication year, country, patient sample size, intervention duration (weeks), and outcome measures.

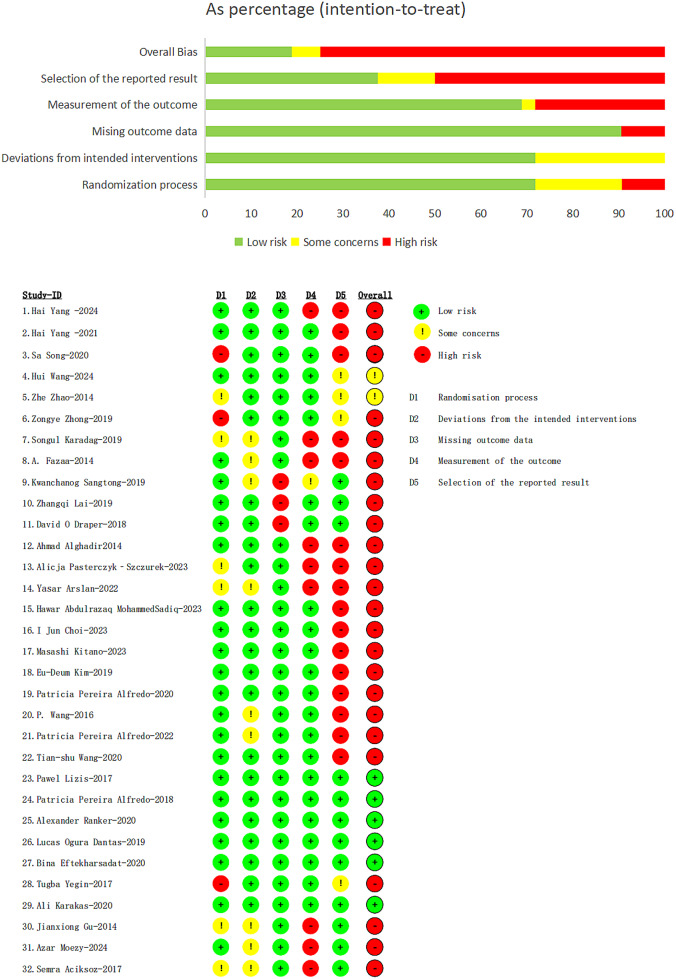

Risk of bias within individual studies

Two reviewers (Qing Jia and Fangyi He) independently assessed the methodological quality of all included studies using the Revised Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for Randomized Trials (RoB 2) [25]. This tool evaluates bias across five domains: (1) bias arising from the randomization process, (2) bias due to deviations from the intended interventions (effect of assignment to intervention), (3) bias due to missing outcome data, (4) bias in outcome measurement, and (5) bias in the selection of the reported result. Each domain was assessed using signaling questions to facilitate evaluation. The risk of bias for each domain was categorized as “Low risk” “Some concerns” or “High risk”.

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted using Stata 17.0 for pairwise comparisons, generating network and funnel plots [26]. Continuous data were analyzed using mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) as effect size metrics. When a closed loop was detected in the network plot, the node-splitting method was applied to assess inconsistency. A P-value > 0.05 indicated no significant inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons, suggesting consistency. Bayesian network meta-analysis was performed using the BUGSnet package [27] in R 4.4.1, generating forest plots, league tables, and Surface Under the Cumulative Ranking Curve (SUCRA) plots. The Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation included an adaptation period of 1000 iterations, a burn-in period of 1000 iterations, and 10,000 iterations. Sensitivity and subgroup analyses were performed as required.

Results

Literature search and quality assessment

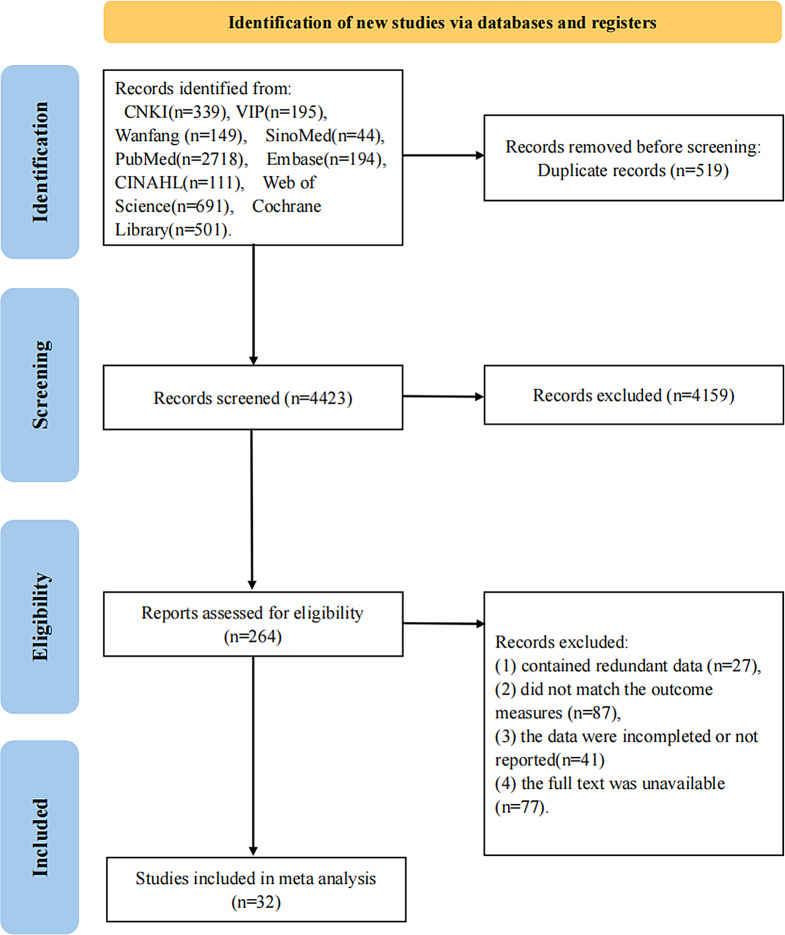

A total of 4,942 articles were initially identified from nine databases: CNKI (n = 339), VIP (n = 195), Wanfang (n = 149), SinoMed (n = 44), PubMed (n = 2,718), Embase (n = 194), CINAHL (n = 111), Web of Science (n = 691), and the Cochrane Library (n = 501). Following a stepwise screening process, 32 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included, comprising 2,078 participants with a mean age range of 55–72 years, of whom 67.5% were female. The sample size per study ranged from 18 patients to 240 patients. The literature screening process is presented in Fig. 1, and the basic characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 3.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart for searching and selecting eligible studies

Table 3.

Basic characteristics of the included studies

| Authors | Country | Sample size | Gender (M/F) | Interventions | Treatment course (week) | Outcome measures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | C | T | C | T | C | ||||

| Hai Yang-2024[28] | China | 61 | 61 | 13/48 | 22/39 | EST_UT | UT | 4 | VAS, WOMAC,6MWT |

| Hai Yang-2021[29] | China | 30 | 30 | 9/21 | 6/24 | EST_UT | UT | 2 | VAS,6MWT |

| Sa Song-2020[30] | China | 49 | 49 | 28/21 | 32/17 | UT | RRE | 8 | VAS |

| Hui Wang-2024[31] | China | 65 | 65 | 33/32 | 35/30 | ESWT | RRE | 8 | VAS,6MWT |

| Zhe Zhao-2014[32] | China | 34 | 36 | 14/20 | 11/25 | ESWT | RRE | 4 | VAS |

| Zongye Zhong-2019[33] | China | 32 | 31 | 11/21 | 12/19 | ESWT | RRE | 4 | VAS, WOMAC |

| Songul Karadag-2019[34] | Turkey | 15 | 17 | 2/13 | 2/15 | TT | RRE | 4 | VAS, WOMAC |

| A. Fazaa-2014[35] | Tunisia | 119 | 121 | 30/89 | 31/90 | TT | RRE | 3 | VAS |

| Kwanchanog Sangtong-2019[36] | Thailand | 74 | 74 | 5/69 | 8/66 | EST_UT | UT | 2 | VAS |

| Zhangqi Lai-2019[37] | China | 20 | 21 | 4/16 | 1/20 | WBVT | RRE | 8 | 6MWT |

| David O Draper-2018[38] | United States | 51 | 33 | 23/28 | 16/17 | UT | RRE | 6 | VAS |

| Ahmad Alghadir-2014[39] | Saudi Arabia | 20 | 20 | 10/10 | 12/8 | LLLT | RRE | 4 | VAS, WOMAC |

| Alicja Pasterczyk-Szczurek-2023[40] | Poland | 16 | 16 | 1/15 | 4/12 | WBVT | RRE | 3 | VAS |

| Yasar Arslan-2022[41] | Turkey | 26 | 25 | 4/22 | 2/23 | ESWT | RRE | 3 | VAS, WOMAC |

| Hawar Abdulrazaq MohammedSadiq-2023[42] | Iraq | 18 | 16 | 5/13 | 3/13 | CT | RRE | 8 | WOMAC |

| I Jun Choi-2023[43] | Korea | 9 | 9 | 4/5 | 5/4 | ESWT | RRE | 3 | VAS |

| Masashi Kitano-2023[44] | Japan | 13 | 13 | 3/10 | 2/11 | UT | RRE | 5 | VAS |

| Eu-Deum Kim-2019[45] | Korea | 19 | 19 | 3/16 | 5/14 | EST_UT | EST | 8 | VAS, WOMAC |

| Patricia Pereira Alfredo-2020[46] | Brazil | 20 | 20 | 5/15 | 6/14 | UT | RRE | 8 | VAS, WOMAC |

| P. Wang-2016[47] | China | 19 | 20 | 9/10 | 7/13 | WBVT | RRE | 12 | VAS, WOMAC,6MWT |

| Patricia Pereira Alfredo-2022[48] | Brazil | 20 | 20 | 4/16 | 3/17 | LLLT | RRE | 8 | VAS, WOMAC |

| Tian-shu Wang-2020[49] | China | 36 | 36 | 24/12 | 21/15 | ESWT | RRE | 10 | VAS, WOMAC |

| Pawel Lizis-2017[50] | Poland | 20 | 20 | 7/13 | 9/11 | ESWT | RRE | 5 | WOMAC |

| Patricia Pereira Alfredo-2018[51] | Brazil | 20 | 20 | - | - | LLLT | RRE | 8 | VAS, WOMAC |

| Alexander Ranker-2020[52] | Germany | 14 | 13 | 5/9 | 3/10 | EST | RRE | 3 | 6MWT |

| Lucas Ogura Dantas-2019[53] | Brazil | 30 | 30 | 15/15 | 15/15 | CT | RRE | 1 | VAS |

| Bina Eftekharsadat-2020[54] | Iran | 25 | 25 | 0/25 | 3/22 | ESWT | RRE | 3 | VAS, WOMAC |

| Tugba Yegin-2017[55] | Turkey | 30 | 32 | - | - | UT | RRE | 2 | 6MWT |

| Ali Karakas-2020[56] | Germany | 39 | 36 | 8/31 | 4/32 | UT | RRE | 8 | VAS, WOMAC |

| Jianxiong Gu-2014[57] | China | 30 | 30 | 12/18 | 11/19 | LLLT | RRE | 3 | VAS |

| Azar Moezy-2024[58] | Iran | 25 | 25 | 0/25 | 0/25 | EST | RRE | 4 | VAS, WOMAC,6MWT |

| Semra Aciksoz-2017[59] | Turkey | 32, 32, 32 | 5/27, 6/26, 7/25 | TT, CT, RRE | 3 | VAS, WOMAC | |||

Note M( Male); F( Female); T(Treatment group); C(Control group)

Of the 32 included studies, six [50–54, 56] were assessed as having a low overall risk of bias, two [31, 32] were rated as raising some concerns, and the remaining studies were deemed to have a high risk of bias. In most cases, the high risk of bias was attributed to selective reporting by assessors. Three studies by Song et al. [30, 33, 55] exhibited a high risk of bias associated with the randomization process. Three studies [36–38] had a high risk of bias due to missing outcome data, whereas nine studies [28, 35, 36, 39–41, 57–59] had a high risk of bias related to outcome measurement, as shown in Fig. 2. Studies with three or more domains classified as having a high risk of bias were excluded from the analysis.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias summary

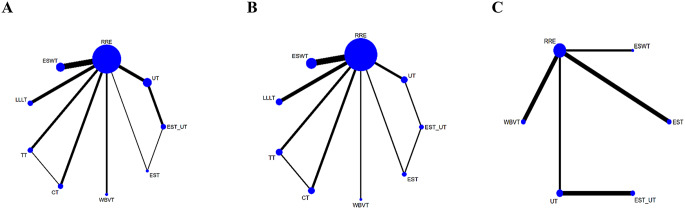

Network relationships and consistency analysis

The network diagrams for the three outcome measures are shown in Fig. 3A-C. Twenty-nine studies reported VAS scores involving nine physical therapeutic modalities and routine rehabilitation exercises, forming two closed loops. Seventeen studies reported WOMAC scores, involving 9 physical therapeutic modalities and routine rehabilitation exercises, also forming two closed loops. Eight studies reported the 6 MWT, involving six physical therapeutic modalities and routine rehabilitation exercises, with no closed loops formed.

Fig. 3.

A-C Network Plots of the Visual Analogue Scale, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index, and Six-Minute Walk Test

A global inconsistency test was conducted across all studies, revealing that the inconsistency for all three outcome measures was not significant (P > 0.05), indicating minimal inconsistency across the studies. Therefore, the consistency model was considered appropriate for the analysis. Additionally, a local inconsistency test was performed using the node-splitting method to compare direct and indirect comparisons within the network. The results showed no statistically significant inconsistencies, thus further supporting the validity of the consistency model.

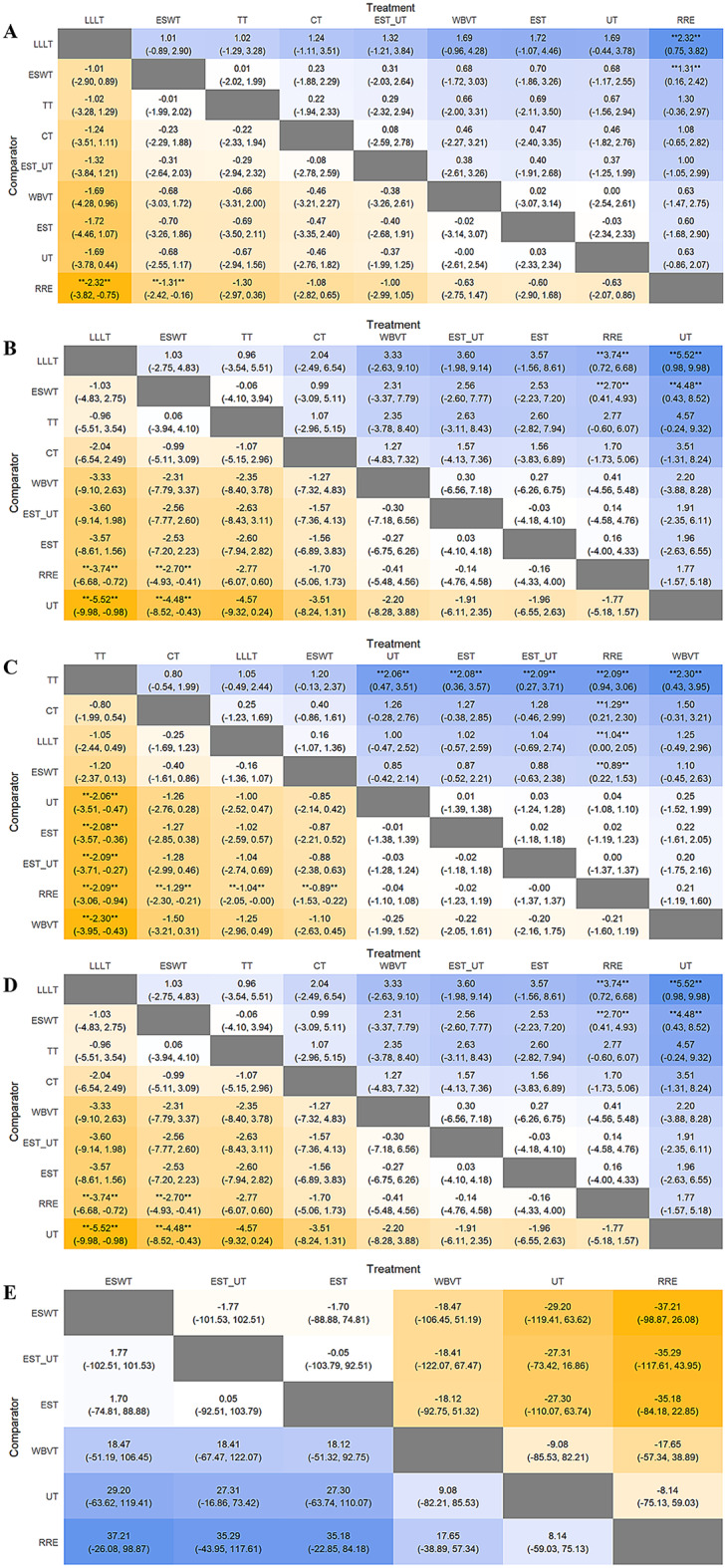

Visual analogue scale

A total of 27 studies involving nine interventions were included in the analysis of VAS scores. A forest plot with the RRE as the comparator is shown in Fig. 4A. All interventions resulted in a reduction in VAS scores compared to RRE. However, only LLLT (MD = -3.32, 95% CI = -3.82, -0.75) and ESWT (MD = -1.31, 95% CI = -2.42, -0.16) showed statistically significant differences compared with RRE (P < 0.05). These findings are depicted in the league and SUCRA plots (Figs. 5A and 6A). The SUCRA rankings were as follows: LLLT (90.1) > ESWT (62.8) > TT (61.9) > CT (54.4) > EST_UT (53.2) > WBVT (38.5) > EST (39.3) > UT (37.5) > RRE (12.4).

Fig. 4.

A-E Forest Plots of the Visual Analogue Scale, WOMAC Pain Subscale, WOMAC Stiffness Subscale, WOMAC Function Subscale, and Six-Minute Walk Test

Fig. 5.

A-E League Tables of the Visual Analogue Scale, WOMAC Pain Subscale, WOMAC Stiffness Subscale, WOMAC Function Subscale, and Six-Minute Walk Test. Comparison of all treatment in the network, combined indirect and direct if, available. ** indicates that the difference is statistically significant

Fig. 6.

A-E SUCRA Plots of the Visual Analogue Scale, WOMAC Pain Subscale, WOMAC Stiffness Subscale, WOMAC Function Subscale, and Six-Minute Walk Test

Western Ontario and Mcmaster universities arthritis index

A total of 17 studies evaluated using the WOMAC scale, involving 9 interventions.

Pain subscale

A forest plot with the RRE as the comparator is shown in Fig. 4B. Except for UT, all interventions resulted in a reduction in the WOMAC pain subscale compared to RRE. However, only LLLT (MD = -3.74, 95% CI = -6.68, -0.72) and ESWT (MD = -2.70, 95% CI = -4.93, -0.41) demonstrated statistically significant differences compared with RRE (P < 0.05). These results are further illustrated in league and SUCRA plots (Figs. 5B and 6B, respectively). The SUCRA rankings were LLLT (88.5) > TT (77.0) > ESWT (75.7) > CT (59.2) > WBVT (39.9) > EST_UT (36.6) > EST (35.7) > RRE (29.7) > UT (7.8).

Stiffness subscale

The forest plot (Fig. 4C) revealed that WBVT was less effective than RRE in improving stiffness associated with knee osteoarthritis, whereas UT, EST, and EST/UT showed comparable effects to RRE. Compared to RRE, TT (MD = -2.09, 95% CI = -3.06 to -0.94) and CT (MD = -1.29, 95% CI = -2.30 to -0.21) demonstrated greater reductions in the WOMAC stiffness subscale, followed by LLLT (MD = -1.04, 95% CI = -2.05 to 0.00) and ESWT (MD = -0.89, 95% CI = -1.53 to -0.22). All the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). These findings were further visualized in league and SUCRA plots (Figs. 5C and 6C). SUCRA rankings were TT (98.1), CT (79.8), LLLT (71.8), ESWT (67.3), UT (29.1), EST (29.0), EST_UT (28.4), RRE (26.1), and WBVT (20.5).

Function subscale

A Forest plot with the RRE as the comparator is shown in Fig. 4D. Except for UT, all interventions resulted in a reduction in the WOMAC Function Subscale compared with RRE. However, none of the interventions showed significant differences compared to RRE. These results are further illustrated in league and SUCRA plots (Figs. 5D and 6D). The SUCRA rankings were TT (84.0) > LLLT (79.8) > CT (63.7) > ESWT (61.8) > WBVT (45.2) > EST (38.3) > EST_UT (38.0) > RRE (29.0) > UT (10.1).

Six-minute walk test

Eight studies involving six interventions reported the outcomes of the 6 MWT. As shown in the forest plots (Fig. 4E), all interventions improved the 6-minute walking distance compared to RRE; however, the differences were not statistically significant. These results are further illustrated in league and SUCRA plots (Figs. 5E and 6E). The SUCRA ranking was as follows: ESWT (71.5); EST_UT (69.8); EST (68.2); WBVT (42.4); UT (29.4) and RRE (18.3).

Publication bias

Funnel plots were constructed for VAS scores, WOMAC Pain Subscale, the WOMAC Stiffness Subscale, the WOMAC Function Subscale, and 6WMT. The results indicated that The funnel plots for all five outcomes were approximately symmetric on both sides, suggesting a low probability of publication bias, as shown in Fig. 7 I-V.

Fig. 7.

I-V Funnel plots of the Visual Analogue Scale, WOMAC Pain Subscale, WOMAC Stiffness Subscale, WOMAC Function Subscale, and Six-Minute Walk Test. The X-axis represents the effect size, while the Y-axis represents the standard error. In Fig I-IV, A: CT, B: EST, C: EST_UT, D: ESWT, E: LLLT, F: RRE, G: TT, H: UT, I: WBVT. In Fig V, A: EST; B: EST_UT; C: ESWT; D: RRE; E: UT; F: WBVT

Discussion

In the present analysis, regarding the efficacy of pain relief in patients with KOA, both the VAS and WOMAC pain subscale scores indicated that LLLT, ESWT, and TT were among the top three modalities in the SUCRA analysis, with LLLT emerging as the most effective. LLLT has been shown to significantly alleviate pain and other adverse symptoms associated with KOA, a finding consistent with that of Oliveira et al. [60]. One study [61] demonstrated that LLLT improves local blood circulation, promotes tissue regeneration, and reduces pain and edema. Lou et al. [62] suggested that LLLT might inhibit the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby attenuating the inflammatory response, which plays a pivotal role in relieving pain and enhancing joint function. Additionally, a study [63] found that LLLT can reduce chondrocyte apoptosis, stimulate the synthesis of extracellular matrix (ECM) components, and decrease the release of inflammatory mediators and proteolytic enzymes in chronic joints, thu s, preventing degenerative changes in the joints and surrounding tissues, alleviating oxidative stress, and ultimately mitigating pain during the progression of KOA. ESWT ranked second in the SUCRA analysis, and its efficacy in relieving pain in patients with KOA has been substantiated by numerous randomized controlled trials [33, 64, 65]. The analgesic mechanisms of ESWT are likely multifactorial, involving anti-inflammatory effects [66], promotion of angiogenesis [67], reduction of joint effusion [43], and modulation of substance P release [68]. Recent studies [69] have indicated a negative linear relationship between ESWT dosage and clinical outcomes, suggesting that higher energy levels may result in greater clinical improvement in KOA treatment than lower energy settings. TT ranked third in the SUCRA analysis, although the difference compared with RRE was not statistically significant. It is well established that thermotherapy promotes muscle relaxation and enhances blood circulation at The affected site, thereby reducing pain and stiffness [70]. Although thermotherapy has demonstrated positive effects in KOA treatment, its use as a stand-alone intervention remains relatively limited. More frequently, it is combined with other modalities, such as electrotherapy [71] or moxibustion [72]. This study found that LLLT was ranked higher than ESWT, although the difference was not statistically significant. LLLT has been shown to have a significant effect on pain relief and disability reduction at specific dosages; however, the overall effect remains debatable, largely because of the influence of varying treatment parameters [73]. Notably, one study [74] reported that LLLT with wavelengths in the range of 904– The 905 nm laser is particularly effective in alleviating pain in patients with KOA. In contrast, while ESWT provides short-term pain relief, it is also associated with the potential for pain rebound [75]. Consequently, clinicians should adopt a comprehensive approach when selecting treatment options for KOA, carefully considering individual patient characteristics and preferences, to optimize therapeutic outcomes.

Second, with regard to the alleviation of stiffness in KOA patients, the results of this study indicated that TT ranked first in the SUCRA analysis, with a statistically significant difference compared with RRE (P < 0.05). A study by Gao et al. [76], using an animal model, found that thermotherapy could reduce congestion, edema in the joint capsule and synovial tissues, and cartilage surface wear, thereby alleviating joint stiffness. The underlying mechanism appears to be related to suppression of inflammatory factors. Another study [77] suggested that thermotherapy accelerated blood circulation and enhanced muscle and soft tissue metabolism, which contributed to the reduction in joint stiffness. These mechanisms may work synergistically by inhibiting inflammatory mediators, promoting local blood circulation, and enhancing tissue metabolism, thereby reducing knee joint stiffness [78, 79]. Consequently, thermotherapy may be an effective method to alleviate stiffness in patients with KOA. However, there is currently no evidence to suggest that thermotherapy has a distinct advantage over other physical modalities in reducing joint stiffness in patients with KOA, and large-scale randomized controlled trials are required. Furthermore, thermotherapy offers advantages, such as ease of administration, cost-effectiveness, and safety, and can be performed both at home and in other settings. However, caution is required when applying thermotherapy to patients with sensory impairments or poor local skin conditions as there is an increased risk of burns. Therefore, clinicians should carefully tailor interventions and dosages based on an individual patient’s condition to optimize the therapeutic outcomes. Moreover, with respect to the improvement of joint function in KOA patients, the results of this study demonstrated that LLLT and ESWT were the most effective modalities in the SUCRA ranking for the WOMAC Functional Subscale and 6 MWT, respectively. A study [80] by indicated that LLLT may help treat KOA by promoting tissue regeneration, thereby improving symptoms such as joint pain, stiffness, restricted joint mobility, and decreased walking function. Alves et al. [81] further suggested that LLLT can modulate the expression of IL-6 mRNA and reduce the number of neutrophils during the initial inflammatory phase, thereby alleviating the signs and symptoms of osteoarthritis. These findings suggest that the precise mechanism by which LLLT improves joint function in patients with KOA remains unclear and warrants further investigation in future studies. Similarly, numerous studies [82–84]have confirmed the effectiveness of ESWT in improving knee joint function. However, its exact mechanism of action remains unclear. One hypothesis proposed by researchers [85] posits that “ESWT may enhance the proliferation of target cells seeded on bioactive scaffolds, promote chondrogenic differentiation, and stimulate the production of extracellular matrix (ECM) in cartilage.” This hypothesis is based on the mechanical signaling transmitted by cells, where cells convert mechanical signals from shock waves into biochemical responses through integrins, ion channels, the cytoskeleton, growth factor receptors, and the nucleus. Additionally, by regulating gene expression and upregulating the release of various growth factors in the three-dimensional cartilage environment, ESWT has the potential to support cells (such as chondrocytes and stem cells) in simulating their optimal functions. Other studies [67, 86] have also shown that ESWT can promote the repair of cartilage and subchondral bone damage through the involvement of multiple cytokines, chemokines, proteins, and miRNAs. Although the efficacy of ESWT is well established, its underlying mechanisms require further investigation. In summary, both LLLT and ESWT may alleviate joint functional issues in KOA patients through distinct mechanisms. Healthcare professionals should consider the specific clinical conditions of patients when selecting the most appropriate physical treatment modality. In conclusion, regarding the improvement of pain and joint function in patients with KOA, both LLLT and ESWT demonstrated superior efficacy compared to other physical modalities. In terms of alleviating stiffness, TT showed greater advantages than the other treatments did. However, this study has several limitations: (1) only Chinese and English-language literature were included; (2) the 32 studies included in the analysis exhibited a relatively high risk of bias, with considerable variation in the frequency, duration, and protocols of the interventions, which may have affected the accuracy of the ranking results; and (3) because of the limited number of reports, the inclusion of stiffness and joint function indicators in the interventions was relatively sparse, which may introduce potential bias in the findings.

Conclusion

This study compared the efficacy of nine physical modalities for the treatment of KOA. The results showed that LLLT and ESWT were superior to RRE, with LLLT being the most effective treatment. The TT appears to be the most effective modality for alleviating stiffness. LLLT has been found to be the most promising treatment for improving joint function. Regarding joint mobility, ESWT was more effective than other interventions. Different dosages of the physical modalities are crucial for their use and efficacy. Therefore, when interpreting the findings of this study, clinicians should consider factors such as patient condition, preferences, economic situation, and available facilities to select the most appropriate physical modality. Future research should involve larger randomized controlled trials to verify the efficacy of certain physical modalities or to explore the differences in the effectiveness of various physical interventions for KOA, with the aim of providing optimal treatment strategies and enhancing patient quality of life.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

In this study, Xiangzhou Lan (X.L.) and Lingjia Li (L.L.), as co-first authors, were jointly responsible for the conceptual design of the study and the primary drafting of the manuscript. They also participated in the screening of literature and the extraction of data. Qing Jia (Q.J.) and Fangyi He (F.H.) were in charge of assessing the risk of bias in the included studies. Gaoyan Kuang (G.K.) and Weike Zeng (W.Z.) contributed to the statistical analysis, particularly the pairwise meta-analysis and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Miao Chen (M.C.) and Cheng Guo (C.G.) was involved in the interpretation of the study results and the writing of the discussion section. Qing Chen (Q.C.) and Zhi Wen (Z.W.), as corresponding authors, were responsible for the final review of the manuscript, as well as correspondence with the journal. All authors have read and approved the final submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by The Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 2024JJ9424).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Because we reanalyzed the existing data and no identifiable information was shared, this study did not require an independent ethical review.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiangzhou Lan and Lingjia Li contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Contributor Information

Zhi Wen, Email: 1158968790@qq.com.

Qing Chen, Email: 13787142874@163.com.

References

- 1.Glyn-Jones S, Palmer AJ, Agricola R, Price AJ, Vincent TL, Weinans H, Carr AJ (2015) Osteoarthr Lancet 386(9991):376–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martel-Pelletier J, Barr AJ, Cicuttini FM, Conaghan PG, Cooper C, Goldring MB, Goldring SR, Jones G, Teichtahl AJ, Pelletier JP, Osteoarthritis (2016) Nat Rev Dis Primers 2:16072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.China Association of Chinese Medicine for Orthopedics (2015) Expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of knee osteoarthritis in traditional Chinese medicine (2015 Edition). J Trad Chin Orthop Trauma 27(7):484–485 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michael JW, Schlüter-Brust KU, Eysel P (2010) The epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Dtsch Arztebl Int 107(9):152–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giorgino R, Albano D, Fusco S, Peretti GM, Mangiavini L, Messina C (2023) Knee osteoarthritis: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and mesenchymal stem cells: what else is new?? An update. Int J Mol Sci 24(7):6405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandl LA (2019) Osteoarthritis year in review 2018: clinical. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 27(3):359–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tong L, Yu H, Huang X, Shen J, Xiao G, Chen L, Wang H, Xing L, Chen D (2022) Current Understanding of osteoarthritis pathogenesis and relevant new approaches. Bone Res 10(1):60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, Callahan L, Copenhaver C, Dodge C, Felson D, Gellar K, Harvey WF, Hawker G, Herzig E, Kwoh CK, Nelson AE, Samuels J, Scanzello C, White D, Wise B, Altman RD, DiRenzo D, Fontanarosa J, Giradi G, Ishimori M, Misra D, Shah AA, Shmagel AK, Thoma LM, Turgunbaev M, Turner AS, Reston J (2020) 2019 American college of rheumatology/arthritis foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 72(2):149–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chinese Society of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (2024) West China hospital of Sichuan university. Chinese guideline for the rehabilitation treatment of knee osteoarthritis (2023 edition), vol 24. CHINESE JOURNAL OF EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE, pp 1–14. 1

- 10.Smith SR, Deshpande BR, Collins JE, Katz JN, Losina E (2016) Comparative pain reduction of oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids for knee osteoarthritis: systematic analytic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 24(6):962–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Primorac D, Molnar V, Matišić V, Hudetz D, Jeleč Ž, Rod E, Čukelj F, Vidović D, Vrdoljak T, Dobričić B, Antičević D, Smolić M, Miškulin M, Ćaćić D, Borić I (2021) Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 14(3):205Comprehensive Review of Knee Osteoarthritis Pharmacological Treatment and the Latest Professional Societies’ Guidelines [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu H, Xiao LB, Zhai WT (2023) Expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of knee osteoarthritis with integrated traditional Chinese and Western medicine. WORLD Chin Med 18(7):929–935 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farì G, Mancini R, Dell’Anna L et al (2024) Medial or lateral, that is the question: A retrospective study to compare two injection techniques in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis pain with hyaluronic acid. J Clin Med 13(4):1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farì G, Megna M, Scacco S et al (2023) Effects of terpenes on the osteoarthritis cytokine profile by modulation of IL-6: double face versus dark Knight? Biology (Basel) 12(8):1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen P, Huang L, Ma Y et al (2019) Intra-articular platelet-rich plasma injection for knee osteoarthritis: a summary of meta-analyses. J Orthop Surg Res 14(1):385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma Y, Chen YS, Liu B, Sima L (2024) Ultrasound-Guided radiofrequency ablation for chronic osteoarthritis knee pain in the elderly: A randomized controlled trial. Pain Physician 27(3):121–128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jansen NEJ, Schiphof D, Oei E et al (2022) Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a combined lifestyle intervention compared with usual care for patients with early-stage knee osteoarthritis who are overweight (LITE): protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 12(3):e059554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang C, Hou Y, Yang Y, Liu J, Li Y, Lu D, Chen S, Wang J (2024) A bibliometric analysis of the application of physical therapy in knee osteoarthritis from 2013 to 2022. Front Med (Lausanne) 11:1418433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao CD, Chen HC, Huang MH, Liou TH, Lin CL, Huang SW (2023) Comparative efficacy of Intra-Articular injection, physical therapy, and combined treatments on pain, function, and sarcopenia indices in knee osteoarthritis: A network Meta-Analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Mol Sci 24(7):6078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao B, Li L, Shen P et al (2023) Effects of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching in relieving pain and balancing knee loading during stepping over Obstacles among older adults with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 18(2):e0280941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng Y, Qi Q, Lee CL, Tay YL, Chai SC, Ahmad MA (2025) Effects of whole-body vibration training as an adjunct to conventional rehabilitation exercise on pain, physical function and disability in knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 20(2):e0318635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koster A, Stevens M, van Keeken H, Westerveld S, Seeber GH (2023) Effectiveness and therapeutic validity of physiotherapeutic exercise starting within one year following total and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act 20(1):8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toonders SAJ, van der Meer HA, van Bruxvoort T, Veenhof C, Speksnijder CM (2023) Effectiveness of remote physiotherapeutic e-Health interventions on pain in patients with musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 45(22):3620–3638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, PRISMA-P Group (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 350:g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366:l4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tonin FS, Rotta I, Mendes AM, Pontarolo R (2017 Jan-Mar) Network meta-analysis: a technique to gather evidence from direct and indirect comparisons. Pharm Pract (Granada) 15(1):943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Béliveau A, Boyne DJ, Slater J, Brenner D, Arora P (2019) BUGSnet: an R package to facilitate the conduct and reporting of bayesian network Meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol 19(1):196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang H, Cai JH, Zhou C, Zhang SJ, Xiao T, Hu BC, Ai JF, Li Z (2024) Effects of ultrasound combined with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on knee joint pain and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Chin J Rehabilitation Med 39(8):1174–1179 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang H, Zhao ZE, Li XF, Zhao J, Zhang SJ, Xiao T, Deng PL, Ai JF, Li Z, Li Z (2021) Clinical observation of the efficacy of ultrasound combined with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Chin J Rehabilitation Med 36(12):1584–1586 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song S, Liu Y, Zhang BX, Teng C, Zhao SS (2020) Clinical efficacy observation of low intensity pulse ultrasound combined with quadriceps femoris muscle strength intensive training in the treatment of patients with knee osteoarthritis. Progress Mod Biomed 20(14):2668–2671 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Yang JY, Li W (2024) The effect of extracorporeal shock wave combined with neuromuscular training on elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis and its effects on knee synovial fluid of IL-1β, IL-17, and PGE2 levels. J Ningxia Med Univ 46(8):791–796 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Z, Shi Z, Yan J, Ai Q, Ding ZK, Xing GY (2014) Effects of extracorporeal shock wave therapy on early to Mid-term knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Chin J Rehabil Theory Pract 20(1):76–78 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhong Z, Liu B, Liu G, Chen J, Li Y, Chen J, Liu X, Hu Y (2019) A randomized controlled trial on the effects of Low-Dose extracorporeal shockwave therapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 100(9):1695–1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karadağ S, Taşci S, Doğan N, Demir H, Kiliç Z (2019) Application of heat and a home exercise program for pain and function levels in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Pract 25(5):e12772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fazaa A, Souabni L, Ben Abdelghani K, Kassab S, Chekili S, Zouari B, Hajri R, Laatar A, Zakraoui L (2014) Comparison of the clinical effectiveness of thermal cure and rehabilitation in knee osteoarthritis. A randomized therapeutic trial. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 57(9–10):561–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sangtong K, Chupinijrobkob C, Putthakumnerd W, Kuptniratsaikul V (2019) Does adding transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation to therapeutic ultrasound affect pain or function in people with osteoarthritis of the knee? A randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 33(7):1197–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lai Z, Lee S, Hu X, Wang L (2019) Effect of adding whole-body vibration training to squat training on physical function and muscle strength in individuals with knee osteoarthritis. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 19(3):333–341 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Draper DO, Klyve D, Ortiz R, Best TM (2018) Effect of low-intensity long-duration ultrasound on the symptomatic relief of knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, placebo-controlled double-blind study. J Orthop Surg Res 13(1):257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alghadir A, Omar MT, Al-Askar AB, Al-Muteri NK (2014) Effect of low-level laser therapy in patients with chronic knee osteoarthritis: a single-blinded randomized clinical study. Lasers Med Sci 29(2):749–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pasterczyk-Szczurek A, Golec J, Golec E (2023) Effect of low-magnitude, variable-frequency vibration therapy on pain threshold levels and mobility in adults with moderate knee osteoarthritis-randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 24(1):287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arslan Y, Kul A (2022) Effectiveness comparison of extracorporeal shock wave therapy and conventional physical therapy modalities in primary knee osteoarthritis. Turk J Osteoporos 28(1):83–90 [Google Scholar]

- 42.MohammedSadiq HA, Rasool MT (2023) Effectiveness of home-based conventional exercise and cryotherapy on daily living activities in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Med (Baltim) 102(18):e33678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi IJ, Jeon JH, Choi WH, Yang HE (2023) Effects of extracorporeal shockwave therapy for mild knee osteoarthritis: A pilot study. Med (Baltim) 102(46):e36117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kitano M, Kawahata H, Okawa Y, Handa T, Nagamori H, Kitayama Y, Miyashita T, Sakamoto K, Fukumoto Y, Kudo S (2023) Effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound on the infrapatellar fat pad in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Phys Ther Sci 35(3):163–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim ED, Won YH, Park SH, Seo JH, Kim DS, Ko MH, Kim GW (2019) Efficacy and safety of a stimulator using Low-Intensity pulsed ultrasound combined with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis. Pain Res Manag 2019:7964897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alfredo PP, Junior WS, Casarotto RA (2020) Efficacy of continuous and pulsed therapeutic ultrasound combined with exercises for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 34(4):480–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang P, Yang L, Li H, Lei Z, Yang X, Liu C, Jiang H, Zhang L, Zhou Z, Reinhardt JD, He C (2016) Effects of whole-body vibration training with quadriceps strengthening exercise on functioning and gait parameters in patients with medial compartment knee osteoarthritis: a randomised controlled preliminary study. Physiotherapy 102(1):86–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alfredo PP, Bjordal JM, Lopes-Martins RÁB, Johnson MI, Junior WS, Marques AP, Casarotto RA (2022) Efficacy of prolonged application of low-level laser therapy combined with exercise in knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled double-blind study. Clin Rehabil 36(10):1281–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang TS, Guo P, Li G, Wang JW (2020) Extracorporeal shockwave therapy for chronic knee pain: A multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Altern Ther Health Med 26(2):34–37 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lizis P, Kobza W, Manko G (2017) Extracorporeal shockwave therapy vs. kinesiotherapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 30(5):1121–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alfredo PP, Bjordal JM, Junior WS, Lopes-Martins RÁB, Stausholm MB, Casarotto RA, Marques AP, Joensen J (2018) Long-term results of a randomized, controlled, double-blind study of low-level laser therapy before exercises in knee osteoarthritis: laser and exercises in knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rehabil 32(2):173–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ranker A, Husemeyer O, Cabeza-Boeddinghaus N, Mayer-Wagner S, Crispin A, Weigl MB (2020) Microcurrent therapy in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: could it be more than a placebo effect? A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 56(4):459–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dantas LO, Breda CC, da Silva Serrao PRM, Aburquerque-Sendín F, Serafim Jorge AE, Cunha JE, Barbosa GM, Durigan JLQ, Salvini TF (2019) Short-term cryotherapy did not substantially reduce pain and had unclear effects on physical function and quality of life in people with knee osteoarthritis: a randomised trial. J Physiother 65(4):215–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eftekharsadat B, Jahanjoo F, Toopchizadeh V, Heidari F, Ahmadi R, Babaei-Ghazani A (2020) Extracorporeal shockwave therapy and physiotherapy in patients with moderate knee osteoarthritis. Crescent J Med Biol Sci 7(4):518–526 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yeğin T, Altan L, Kasapoğlu Aksoy M (2017) The effect of therapeutic ultrasound on pain and physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Ultrasound Med Biol 43(1):187–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karakaş A, Dilek B, Şahin MA, Ellidokuz H, Şenocak Ö (2020) The effectiveness of pulsed ultrasound treatment on pain, function, synovial sac thickness and femoral cartilage thickness in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind clinical, controlled study. Clin Rehabil 34(12):1474–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gu JX, Wen ML, Liang ZM, He XC, Lin CY, Yang XH (2014) Effect of super laser pain therapy on pain and quality of life in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Guangdong Med J 35(6):873–874 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moezy A, Masoudi S, Nazari A, Abasi A (2024) A controlled randomized trial with a 12-week follow-up investigating the effects of medium-frequency neuromuscular electrical stimulation on pain, VMO thickness, and functionality in patients with knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 25(1):158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aciksoz S, Akyuz A, Tunay S (2017) The effect of self-administered superficial local hot and cold application methods on pain, functional status and quality of life in primary knee osteoarthritis patients. J Clin Nurs 26(23–24):5179–5190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oliveira S, Andrade R, Valente C, Espregueira-Mendes J, Silva FS, Hinckel BB, Carvalho Ó, Leal A (2024) Effectiveness of photobiomodulation in reducing pain and disability in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review with Meta-Analysis. Phys Ther 104(8):pzae073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Q, Yi CQ (2022) Research progress in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Fudan Univ J Med Sci 49(5):765–770 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lou XQ, Zhong H, Wang XY, Feng HY, Li PC, Wei XC, Wang YQ, Wu XG, Chen WY, Xue YR (2024) Possible mechanisms of multi-pathway biological effects of laser therapy for knee osteoarthritis. Chin J Tissue Eng Res 28(34):5521–5527 [Google Scholar]

- 63.de Freitas LF, Hamblin MR (2016 May-Jun) Proposed mechanisms of photobiomodulation or Low-Level light therapy. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron 22(3):7000417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Zhao Z, Jing R, Shi Z, Zhao B, Ai Q, Xing G (2013) Efficacy of extracorporeal shockwave therapy for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. J Surg Res 185(2):661–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Uysal A, Yildizgoren MT, Guler H, Turhanoglu AD (2020) Effects of radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy on clinical variables and isokinetic performance in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a prospective, randomized, single-blind and controlled trial. Int Orthop 44(7):1311–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cp A, Jayaraman K, Babkair RA, Nuhmani S, Nawed A, Khan M, Alghadir AH (2024) Effectiveness of extracorporeal shock wave therapy on functional ability in grade IV knee osteoarthritis - a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 14(1):16530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.An S, Li J, Xie W, Yin N, Li Y, Hu Y (2020) Extracorporeal shockwave treatment in knee osteoarthritis: therapeutic effects and possible mechanism. Biosci Rep 40(11):BSR20200926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ryskalin L, Morucci G, Natale G, Soldani P, Gesi M (2022) Molecular mechanisms underlying the Pain-Relieving effects of extracorporeal shock wave therapy: A focus on fascia nociceptors. Life (Basel) 12(5):743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen TY, Chou SH, Shih CL (2024) Extracorporeal shockwave therapy in the management of knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review of dose-response meta-analysis. J Orthop 52:67–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brosseau L, Yonge KA, Robinson V, Marchand S, Judd M, Wells G, Tugwell P (2003) Thermotherapy for treatment of osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003(4):CD004522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang Q, Song QP, Shen PX, Mao DW (2024) Effect of hot compress combined with medium-low frequency electrotherapy on pain, joint range of motion, and dynamic stability in elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Med Biomech 39(Suppl):42–43 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Choi TY, Lee MS, Kim JI, Zaslawski C (2017) Moxibustion for the treatment of osteoarthritis: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 100:33–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ganjeh S, Rezaeian ZS, Mostamand J (2020) Low level laser therapy in knee osteoarthritis: A narrative review. Adv Ther 37(8):3433–3449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fan T, Li Y, Wong AYL, Liang X, Yuan Y, Xia P, Yao Z, Wang D, Pang MYC, Ding C, Zhu Z, Li Y, Fu SN (2024) A systematic review and network meta-analysis on the optimal wavelength of low-level light therapy (LLLT) in treating knee osteoarthritis symptoms. Aging Clin Exp Res 36(1):203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ma H, Zhang W, Shi J, Zhou D, Wang J (2020) The efficacy and safety of extracorporeal shockwave therapy in knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 75:24–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gao F, Du LL, Wang T, Li XF, Zhong YK, Gao QM, Chen R, Yuan PW, Zhao LY (2023) The curative effect and mechanism of magnetic hyperthermia in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. J Xi’an Jiaotong Univ (Medical Sciences) 44(5):587–597 [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ho KK, Kwok AW, Chau WW, Xia SM, Wang YL, Cheng JC (2021) A randomized controlled trial on the effect of focal thermal therapy at acupressure points treating osteoarthritis of the knee. J Orthop Surg Res 16(1):282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rossi R (2024) Heat therapy for different knee diseases: expert opinion. Front Rehabil Sci 5:1390416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shen C, Li N, Chen B, Wu J, Wu Z, Hua D, Wang L, Chen D, Shao Z, Ren C, Xu J (2021) Thermotherapy for knee osteoarthritis: A protocol for systematic review. Med (Baltim) 100(19):e25873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li YC, Zhao BB, Yang CR, Luo QL (2023) Research progress of focused low-intensity pulsed ultrasound in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. West China Med Journa 38(1):134–139 [Google Scholar]

- 81.Alves AC, Vieira R, Leal-Junior E, dos Santos S, Ligeiro AP, Albertini R, Junior J, de Carvalho P (2013) Effect of low-level laser therapy on the expression of inflammatory mediators and on neutrophils and macrophages in acute joint inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther 15(5):R116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mingwang Z, Zhuanli D, Changhao W, Lufang F, Xiaoping W, Haiping L, Xing JI, Kehu Y, Shenghua LI (2024) Efficacy and safety of extracorporeal shock wave therapy combined with sodium hyaluronate in treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Tradit Chin Med 44(2):243–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu BZ, Zhong ZY, Liu GH, Li Y, Chen JX, Liu XX, Hu YW, Ding F (2019) The effects of extracorporeal shock wave therapy on the lower limb function and articular cartilage of patients with knee osteoarthritis. Chin J Phys Med Rehabil 41(7):494–498 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Avendaño-Coy J, Comino-Suárez N, Grande-Muñoz J, Avendaño-López C, Gómez-Soriano J (2020) Extracorporeal shockwave therapy improves pain and function in subjects with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Int J Surg 82:64–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ji Q, He C (2016) Extracorporeal shockwave therapy promotes chondrogenesis in cartilage tissue engineering: A hypothesis based on previous evidence. Med Hypotheses 91:9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chou WY, Cheng JH, Wang CJ, Hsu SL, Chen JH, Huang CY (2019) Shockwave targeting on subchondral bone is more suitable than articular cartilage for knee osteoarthritis. Int J Med Sci 16(1):156–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.