Abstract

The global prevalence of diabetes is rapidly increasing, significantly raising the risk of various cardiovascular diseases. Among these, diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a distinct and critical complication characterized by ventricular hypertrophy and impaired myocardial contractility, ultimately progressing to heart failure and making it a leading cause of mortality among diabetic patients. Despite advances in pharmacological therapies, the effectiveness of managing cardiac dysfunction in DCM remains challenging. Consequently, exploring additional therapeutic strategies for the prevention and treatment of DCM is urgently needed. Beyond pharmacological approaches, lifestyle modifications, particularly exercise and dietary interventions, play a fundamental role in managing DCM due to their significant cardiovascular benefits in diabetic patients. This review synthesizes recent advancements in the field, elucidating the underlying mechanisms through which exercise and dietary interventions influence DCM pathophysiology. By integrating these strategies, we aim to facilitate the development of personalized exercise and dietary regimens that effectively mitigate or prevent DCM progression.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12933-025-02702-y.

Keywords: Diabetic cardiomyopathy, Diabetes, Exercise, Diet, Lifestyle modifications

Research insights

What is currently known about this topic?

DCM is a leading cause of death among diabetic patients. Drug therapies offer limited benefits for DCM. Exercise and dietary interventions can improve cardiovascular health in DCM.

What is the key research question?

How can exercise and dietary strategies be optimized to manage DCM effectively?

What is new?

Diet shows complex effects, with both beneficial and adverse impacts on cardiac metabolism. Exercise regimens effectively mitigate cardiac dysfunction in diet-induced DCM models. Exercise and diet regulate mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, and fibrosis in DCM.

How might this study influence clinical practice?

Tailored exercise and dietary strategies can improve cardiac outcomes in DCM patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12933-025-02702-y.

Introduction

The global prevalence of diabetes is rapidly increasing. More than 529 million people worldwide are currently living with diabetes, and the number of diabetic patients is expected to climb to more than 1.31 billion by 2050 [1]. Diabetes is associated with an increased risk of various cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), with diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) standing out as a distinct and significant complication. This condition leads to ventricular hypertrophy and abnormal myocardial contractility resulting from a complex array of molecular and cellular changes [2]. Notably, DCM is a major driver of heart failure development and is a leading cause of death in diabetic patients [3].

The pathophysiology of DCM involves multiple interconnected processes, including metabolic dysregulation, oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis [4]. In both type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), impaired glucose metabolism leads to the accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which damage cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells. Initially, metabolic adaptation increases fatty acid uptake and β-oxidation to maintain energy supply. However, as the disease progresses, excessive lipid accumulation induces lipotoxicity and mitochondrial dysfunction, exacerbating oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and autophagy inhibition. Consequently, cardiomyocyte apoptosis, hypertrophy, and inflammatory responses intensify, accompanied by interstitial fibrosis and disrupted calcium homeostasis, which collectively contribute to impaired cardiac contractility and arrhythmias, ultimately leading to heart failure and even death [4]. Current pharmacological strategies for DCM primarily include GLP-1 agonists, SGLT-2 inhibitors, NHE-1/NHE-3 inhibitors, and PPAR-γ agonists, which enhance myocardial glucose uptake, regulate glucose and lipid metabolism, and reduce the risk of heart failure and cardiovascular events [5]. However, despite these therapeutic advancements, the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions remains limited. Even intensive glycemic control often fails to improve cardiac function or mitigate heart failure risk [6, 7].

Given these limitations, exploring additional therapeutic strategies for the prevention and treatment of DCM is urgently needed. In this regard, non-pharmacological interventions with multi-target regulatory effects hold significant clinical value. As a well-established first-line strategy for T2DM, the combination of a healthy diet and regular physical activity may also play a crucial role in preventing and treating DCM [8]. Emerging evidence suggests that structured exercise or dietary interventions not only improve cardiovascular health but also directly modulate key pathways involved in DCM progression [9–16]. Notably, both exercise and dietary interventions regulate crucial mechanisms of DCM pathogenesis, including mitochondrial function enhancement, oxidative stress reduction, and attenuation of cardiomyocyte fibrosis [17–23]. This highlights the potential for a combined intervention strategy, where a healthy diet and regular exercise synergistically target these pathogenic processes, potentially yielding superior cardioprotective effects compared to either intervention alone. Furthermore, it has been shown that prediabetic patients without coronary disease exhibit impaired systolic function and adverse changes in left ventricular diastolic parameters [24], underscoring the urgency of early lifestyle interventions in individuals at risk of DCM. Previous reviews have summarized the role of exercise in DCM [25–28], however, they do not capture recent advances in elucidating its mechanistic effects. Since then, numerous animal studies have further investigated the mechanistic effects of exercise, warranting a comprehensive reassessment to facilitate the translation of preclinical findings into clinical practice. Moreover, despite the recognized importance of lifestyle interventions, no review has yet comprehensively explored the impact of dietary interventions alone or in combination with exercise in the management of DCM.

This review aims to synthesize recent advancements in exercise and dietary interventions for DCM, elucidating their underlying mechanisms and therapeutic potential. By integrating these non-pharmacological strategies, we aim to establish a comprehensive framework that elucidates the distinct roles of exercise and dietary modifications while highlighting their synergistic potential in mitigating DCM progression. Ultimately, this approach will facilitate the development of personalized lifestyle regimens to effectively prevent or delay the onset and progression of DCM.

Exercise in treating DCM

Clinical studies on the cardiac benefits of exercise in diabetes

Given the distinct pathophysiological mechanisms of DCM, findings from studies on the general T2DM population cannot be directly extrapolated to patients with DCM. However, clinical heart failure trials indicate that diabetic patients comprise up to one-third of the total study population, with diabetes consistently identified as an independent predictor of poor prognosis [29]. Based on these observations, together with the limited interventional studies specifically targeting DCM, the beneficial effects of exercise on cardiac health in diabetic patients are summarized in Table 1, which could provide clues for DCM treatment. Notably, significant variations in exercise protocols, including differences in type, intensity, frequency, and duration, may influence outcomes, necessitating a critical evaluation to enhance the interpretation of findings and their applicability in clinical practice.

Table 1.

Clinical studies of exercise on diabetic patients

| Subjects, age, sex, number | Exercise program | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| T2DM patients without occult coronary artery disease, 18–75, MF, 223 | Individualized exercise training, followed by telephone-monitored home-based exercise training, 1 year | Myocardial tissue velocity ↑, myocardial strain rate ↑ | Hordern et al. [10] |

| Patients with T2DM, 53–71, MF, 38 | Aerobic and resistance exercise, 3–5 days/week, 12 weeks | Flow-mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilatation ↑, cardiovascular events ↓ | Okada et al. [30] |

| Overweight-to-obese male patients with T2DM, 58.4 ± 0.9, male, 11 | Combination endurance/strength training, three sessions/week, 12 weeks | VO2max ↑, insulin sensitivity ↑, left-ventricular ejection fraction ↑, cardiac index ↑, cardiac output ↑, cardiac lipid content - | Schrauwen-Hinderling et al. [9] |

| Patients with T2DM, ≥ 40, MF, 49 | Individualized exercise intervention, twice/week, 6 months | Exercise intolerance of subclinical diabetic heart disease ↑, resting heart rate ↓, myocardial fibrosis ↓, cardiac autonomic or LV functional adaptations (systolic/diastolic tissue velocities, myocardial deformation) - | Sacre et al. [11] |

| Patients with T2DM, 50–70, MF, 28 | HIIT, 3 sessions/week, 12 weeks | Cardiac structure (left ventricular wall mass) ↑, systolic function (stroke volume) ↑, early diastolic filling rates ↑, peak torsion ↓ | Cassidy et al. [12] |

DCM, diabetic cardiomyopathy; HIIT, high-intensity interval training; LV, left ventricle; MF, male and female; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; VO2max, maximum oxygen consumption; ↑, improved or up; ↓, attenuated or down;–, no changed

Increasing research highlights the therapeutic potential of both aerobic and resistance training. For instance, engaging in at least 150 min of moderate-intensity exercise per week, incorporating an individualized combination of aerobic and resistance training, has been associated with significant improvements in myocardial tissue velocity, thereby enhancing overall cardiac function [10]. Structured exercise regimens combining aerobic and resistance 3 to 5 times per week for 12 weeks have been shown to significantly improve the flow-mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in patients with T2DM, while also reducing the incidence of cardiovascular events [30]. Similarly, a structured 12-week aerobic and resistance exercise training program, with three training sessions per week, has been demonstrated to enhance maximal oxygen uptake, improve insulin sensitivity, and increase left ventricular ejection fraction in T2DM patients [9]. Another study reported that exercise training, consisting of up to 75 min twice weekly (20–40 min of aerobic exercise and 6–12 resistance exercises), effectively mitigates exercise intolerance in subclinical DCM, lowers resting heart rate, and may attenuate myocardial fibrosis, highlighting its role in mitigating structural cardiac abnormalities [11]. Furthermore, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) further benefits patients by improving heart structure, enhancing systolic function, promoting early diastolic filling, and decreasing myocardial torsion [12].

Overall, despite the heterogeneity in exercise interventions across these studies, the findings consistently highlight the significant cardiovascular benefits of combining aerobic and resistance training in diabetic patients. This suggests that such exercise modalities may also play a preventive role in the development of DCM. In alignment with existing evidence and the guidelines of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) [31], individuals with DCM are advised to engage in at least 150 min of moderate-to-vigorous aerobic exercise per week, supplemented with resistance training, to optimize cardiovascular and metabolic health. Additionally, incorporating HIIT may offer further benefits. Future research should aim to standardize exercise intervention protocols, refine the balance between aerobic and resistance training, and determine the most effective exercise modalities for DCM management. Moreover, translating these findings into real-world clinical practice requires personalized exercise prescriptions tailored to individual patient characteristics, including disease severity, comorbidities, and baseline physical capacity.

Preclinical studies of exercise in DCM

Currently, researchers generally use animal models of T1DM and T2DM to investigate the impact of diabetes on cardiac function related to DCM [32]. Among these, the streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetes model is the most widely used, followed by the high-fat diet (HFD) intervention model and the combined STZ + HFD model [33]. Additionally, frequently employed transgenic animal models include the ZSF1 obese rat, leptin receptor-deficient (Leprdb) mice, leptin-deficient (Lepob/ob) mice, and Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF, fa/fa) rats with spontaneous missense mutations in the leptin receptor gene [33]. The majority of models exhibit diastolic dysfunction, myocardial fibrosis, and left ventricular hypertrophy, closely resembling early-stage DCM. However, they rarely progress to symptomatic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) or refractory end-stage DCM with biventricular dysfunction as observed in humans, thus limiting their ability to fully model advanced DCM [33]. Nevertheless, these animal models remain valuable, as they partially recapitulate the pathological changes observed in diabetic myocardium and provide important mechanistic insights into the development of DCM complications and associated risk factors. Meanwhile, further refinement of animal models is needed to better replicate the pathophysiological characteristics of human DCM and strengthen clinical research to enhance the translational relevance of preclinical findings.

Most preclinical studies use treadmill training to evaluate the effects of exercise on diabetic rodents, varying in incline, speed, and duration. Typically, rodents undergo training five times per week for one hour per session, with speeds progressively increasing until stabilization. Some studies also compare different exercise intensities by employing multiple speed regimens, while others utilize swimming as an alternative exercise method. Although these exercise paradigms provide valuable mechanistic insights, their direct translation to human exercise protocols remains limited. Future research should focus on bridging this gap by optimizing exercise parameters, such as intensity, duration, and frequency, to enhance their applicability in human DCM patients.

Numerous animal studies consistently demonstrate the protective and therapeutic effects of exercise on DCM (Table 2). For instance, progressive treadmill training stabilizing at 27 m/min for one hour daily, five days a week over eight weeks, significantly increased cardiac output under high load in diabetic rats [34]. Exercise training also reversed hypotension and bradycardia, improved myocardial function, and restored specific ultrastructural features of DCM, particularly within mitochondria and the extracellular matrix, reverting to a non-diabetic phenotype [35, 36]. Additionally, exercise diabetic hearts exhibit normalized myocardial glucose oxidation and glycolysis rates, further enhancing cardiac function [37]. Endurance exercise mitigates myocardial dysfunction and prevents adverse alterations in muscle fiber proteins induced by prolonged diabetic dyslipidemia [38]. Aerobic interval training not only nearly restored contractile function in diabetic cardiomyocytes to levels comparable to sedentary wild-type animals [39] but also alleviated cardiac lipo-toxicity and may even reverse DCM progression [40]. Collectively, these findings suggest that appropriately adapted exercise regimens may offer significant benefits in human DCM, although clinical validation is needed.

Table 2.

Preclinical studies of exercise on DCM

| Animals | Exercise program | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female Sprague-Dawley rats | Treadmill, plateaued at 27 m/min for 1 h/day, 5 days/ week for 8 weeks | Cardiac output ↑ | Blieux et al. [34] |

| Male Wistar rats | Treadmill, plateaued at 31 m/min for 1 h/day*twice, 5 days/week for 10 weeks | Hypotension and bradycardia (Reversed), myocardial function ↑ | Angelis et al. [35] |

| Male Sprague- Dawley rats | Treadmill, individualized, 5 days/week for 9 weeks | Collagen fibrils, cytoplasmic area, and level of mitochondrial disruption ↓; myofibril volume density, lipid accumulation, or nuclear deformities - | Searls et al. [36] |

| Male Sprague- Dawley rats | Treadmill, 27 m/min for 10 min/day for 3 weeks, 28 m/min for 40 min/day for 3 weeks, 32 m/min for 1 h/day for 4 weeks |

Rates of myocardial glucose oxidation and glycolysis (Restored) Cardiac performance ↑ |

Broderick et al. [37] |

| Male Yucatan pigs | Treadmill, 10-min warm-up, 30-min walking, 5-min cool down/day, 4 days/week for 14 weeks | Myocardial dysfunction, alterations in myofibrillar proteins (Prevented) | Korte et al. [38] |

| Male Sprague- Dawley rats | Treadmill, plateaued at 20 m/min for 1 h/day, for 8 weeks | Cardiac cycle phase volumetric profiles ↑, decreased end-diastolic volume (Prevented), increased end-systolic volume ↓, defects in LV systolic flow velocity, acceleration, and jerk associated with sedentary diabetes (Restored) | Loganathan et al. [41] |

| db/db mice | Uphill running, alternating between 4 min at 85–90% of VO2max and 2 min at 50% of VO2max for 80 min/day, 5 days/week, for 13 weeks | Contractile function of the diabetic cardiomyocyte (Restored) | Stølen et al. [39] |

| Male Wistar rats | Swimming 1 h/day, 5 days/week, for 8 weeks | Deposition of collagen and reticular fibers in left ventricular muscle (Prevented) | Castellar et al. [43] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | 3554 ± 338 m·day(−1) of voluntary wheel running, for 12 weeks | Impairment of E/A ratios and -dP/dt (Prevented) | Epp et al. [44] |

| Male Wistar rats | Swimming-training, 90 min/day, 5 days/week, with a load of 5% BW for 8 weeks | Interstitial collagen and reticular fibers on the extracellular matrix and glycogen accumulation in the LV ↓ | Silva et al. [79] |

| Male C57BL/6 wild-type or db/db mice | Treadmill, plateaued at 10 m/min for 1 h/day, for 15 weeks |

Cardiac function ↑, myocardial apoptosis and fibrosis (Prevented) Mitochondrial biogenesis in the late stage of DCM ↑ |

Wang et al. [50] |

| Male Sprague- Dawley rats | Treadmill, plateaued at 25 m/min for 1 h/day, for 3 weeks | Expression of p47(phox) and p67(phox) in the hearts ↓ | Sharma et al. [19] |

| db/db mice | Treadmill, plateaued at 10–11 m/min, 330 m, 5 days/week, for 5 weeks | Mitochondrial function ↑ | Veeranki et al. [51] |

| Male Sprague- Dawley rats | Treadmill, plateaued at 10 m/30min/day, for 4 weeks | Elevated tissue malondialdehyde levels ↓, reduced activities of the enzymatic anti-oxidants’ superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, and catalase in cardiac tissue ↑ | Kanter et al. [59] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Treadmill, plateaued at 80% of its capacity (velocity and time), 5 days/week, for 4 weeks | Remodeling in the diabetic heart (Restored) | Novoa et al. [42] |

| Male Wistar rats | Treadmill, plateaued at 60 min/day, 5 days/week, for 4 weeks | Normal LV geometry and collagen content but thinner myocytes MMP-9 mRNA levels and MMP-2 expression ↓ | Silva et al. [80] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Treadmill, plateaued at 15/20 m/min for 1 h/day, for 6 weeks | Myocardial PAI-1 in DEG1, DEG2, and DEG3 rats ↓, serum NO and eNOS ↑ | Chengji et al. [61] |

| Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty rats | Trained by 20 repetitions of climbing a ladder 5 days/week, 12 weeks | Mitochondrial function ↑ | Hee Ko et al. [17] |

| Male Wistar rats | Treadmill, 10-min warm-up, four interval-training periods, 10-min cool down/day, 5 days/week for 8 weeks | Cardiac lipotoxicity ↓, process of DCM (Reversed) | Cai et al. [40] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Treadmill, plateaued at 20/34 m/min for 1 h/day, 5 days/week for 12 weeks | DCM ↓ | Chengji et al. [74] |

| C57BL6 mice | Treadmill, 5 days/week for 20 weeks | Development of DCM (Prevented) | Kar et al. [75] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Treadmill, plateaued at 21 m/min for 1 h/day, 5 days/week for 8 weeks | Diabetic cardiac function ↑ | Li et al. [20] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Treadmill, plateaued at 15.2 m/min for 1 h/day, 5 days/week for 8 weeks | Myocardial fibrosis (Reversed), MMP-2, CTGF, TGF-β1, p-Smad2 and p-Smad3 ↓, TIMP-1 and Smad7 ↑ | Wang et al. [84] |

| Male Wistar rats | Treadmill, 5-min warm-up, four interval-training periods, 5-min cool down/day, 5 days/week for 5 weeks | Blood glucose ↓, heart performance ↑, miR-1 expression ↓, IGF-1 and IGF-1R ↑, apoptotic protein expression ↓ | Delfan et al. [71] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Swimming, 5 days/week for 4 weeks | Cardioprotective effects against DCM | Hussein et al. [60] |

| Male Wistar rats | Treadmill, 5 days/week, for 8 weeks | Myocardial function ↑ | Khakdan et al. [67] |

| db/db mice | Treadmill, 5 days/week, for 8 weeks | Onset of coronary and cardiac dysfunction, apoptosis, fibrosis, microvascular rarefaction, and disruption of miRNA signaling (Prevented) | Lew et al. [64] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Treadmill, plateaued at 21 m/min for 1 h/day, 5 days/week, for 8 weeks | Left ventricular end-diastolic internal diameter ↑, left ventricular end-diastolic volume ↑, myocardial HSP27 protein expression, HSP27-S82 phosphorylation levels, pHSP27-titin binding ↑, cardiac muscle fiber alignment ↑ | Shunchang Li et al. [81] |

| Male C57BL/6 mice | Treadmill, 0.5/0.6/0.7/0.8/1.0 km/h/day, for 16 weeks | Mitochondrial function ↑, metabolic disturbances ↓ | Wang et al. [18] |

| Male Wistar rats | Treadmill, HIIT (90 to 95% of VO2max) or MICT (50–65% of VO2max) protocols 5 days a week for 8 weeks | Pro-angiogenic factors ↑, anti-angiogenic factors protein levels ↓, capillary density ↑, interstitial fibrosis in the left ventricle ↓ | Yazdani et al. [82] |

| Mst1 transgenic mice and C57BL/6 male mice | Treadmill, plateaued at 22 cm/s for 1 h/day, 5 days/week, for 12 weeks | Cardiac remodeling ↓ | Sun et al. [65] |

| Male C57BL/6 mice | Treadmill, plateaued at 15 m/min/1hr/day, 6 days/week, for 8 weeks | ECM proteins, MMP-9 and TIMP-1 cardiac concentrations (Favorably changed) | Dede et al. [83] |

| Male Wistar rats | Treadmill, HIIT or MICT protocols, 5 days/week, for 8 weeks | DCM ↓ | Delfan et al. [66] |

| db/db mice | Treadmill, plateaued at 10 m/min/1hr/day, 5 days/week, for 12 weeks | Cardiac remodeling (Reversed) | Ting Wang et al. [86] |

| FGF21−/− mice, FGF21Alb mice, and KlbMyh6 mice | Treadmill, plateaued at 15 cm/s/1hr/day, 5 days/week, for 6 weeks |

Cardiac dysfunction in wild-type mice ↓ Mitochondrial damage in the hearts of wild-type mice ↓ Mitochondrial enzymes in the hearts of wild-type mice ↑ |

Jin et al. [54] |

| Rats | Treadmill, for 8 weeks | B-catenin and c-Myc proteins ↓, GSK3B and Bcl-2 proteins ↑ | Rami et al. [45] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Treadmill, HIIT or MIT protocols, for 18 weeks | Diastolic dysfunction and pathological LV hypertrophy ↓ | D’Haese et al. [46] |

| Male Wistar rats | Treadmill, HIIT or MICT protocols, for 6 weeks |

Oxidative stress and inflammation in cardiac tissue ↓ Cardiac damage ↓ |

Shabab et al. [73] |

| Male Wistar rats | Treadmill, HIIT or MICT protocols, for 6 weeks | Cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis ↓ | Shabab et al. [53] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Swimming training (60 min/days, 5 days/week) for 8 weeks | Insulin resistance, myocardial fibrosis, and myocardial hypertrophy ↓, blood glucose homeostasis ↑ | Yanju Guo et al. [70] |

| Male Wistar rats | Endurance training and prebiotic xylooligosaccharide, for 10 weeks |

the enzyme activity of respiratory Complex I and II and the lactate dehydrogenase in the cardiomyocytes ↑ Collagen and glycogen content in the cardiomyocytes ↓ |

Mariya Choneva et al. [129] |

BW, body weight; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; DCM, diabetic cardiomyopathy; DEG, diabetic exercise group; ECM, cardiac extracellular matrix; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; FGF21Alb, hepatocyte-selective FGF21 KO; HIIT, high-intensity interval training; hr, hour; HSP27, heat shock protein 27; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IGF-1R, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor; LV, left ventricle; MHC, myosin heavy-chain; MICT, moderate-intensity continuous training; MIT, moderate-intensity training; MMPs, metalloproteinases; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor-β1; TIMPs, tissue inhibitors of MMPs; TR, thyroid receptor; improved or up; VO2max, maximum oxygen consumption; -dP/dt, rates of pressure decay; ↓, attenuated or down;–, no changed

Structural and functional assessments reinforce the benefits of exercise in DCM models. Exercise-trained diabetic rats show improved cardiac cycle volume curves, preventing declines in end-diastolic volume and reducing end-systolic volume increases [41]. Moreover, exercise restored deficits in left ventricular systolic flow velocity, acceleration, and contraction to control levels [41]. Additionally, four weeks of treadmill training reduces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and interstitial fibrosis in the hearts of diabetic rats [42], while physical exercise also prevented collagen and reticular fiber deposition in the left ventricle while correcting sarcoplasmic reticulum protein dysregulation, potentially slowing DCM progression [43, 44]. These structural improvements in animal models provide a mechanistic basis for exercise as a non-pharmacological intervention, yet further studies are required to determine if similar benefits can be achieved in human patients.

Among different exercise modalities, HIIT appears particularly effective, not only in reducing cardiomyopathy in T2DM rats but also in alleviating diet-induced diastolic dysfunction and pathological left ventricular hypertrophy [45, 46]. Both moderate-intensity training (MIT) and HIIT have demonstrated protective effects against Western diet (WD)-induced T2DM with associated cardiac dysfunctions [46]. While these findings are promising, further research is needed to assess the safety, feasibility, and long-term benefits of these interventions in clinical populations.

In summary, rodent studies consistently demonstrate the cardioprotective effects of exercise, particularly HIIT, in DCM. However, challenges remain in directly translating these preclinical findings to human patients. Bridging this gap will require future research focused on optimizing exercise protocols, addressing patient-specific variables, and ultimately validating these interventions in clinical trials to establish exercise as a viable therapeutic strategy for DCM management.

Potential mechanisms of protective effects of exercise against DCM

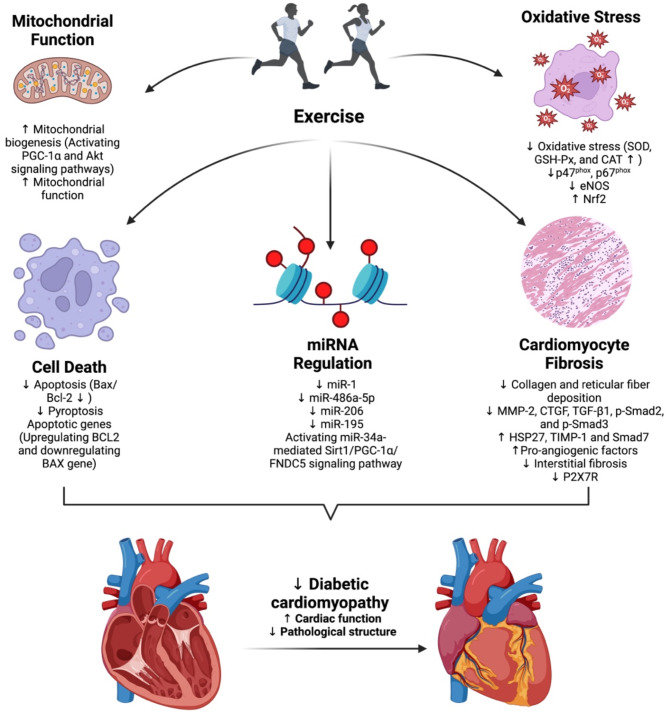

Exercise plays a significant role in mitigating DCM through diverse mechanisms, including impacts on mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, microRNA (miRNA) regulation, cell death, and cardiomyocyte fibrosis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms of exercise targeting DCM. Exercise prevents and improves DCM by improving mitochondrial function, reducing oxidative stress, cell death, cardiomyocyte fibrosis, and modulating miRNA regulation. Abbreviations: CAT, catalase; DCM, diabetic cardiomyopathy; GSH-Px, glutathione peroxidase; miRNA, microRNA; SOD, superoxide dismutase

Exercise improves mitochondrial function

Mitochondria are central to cellular metabolism, and numerous studies have confirmed the relationship between mitochondrial dysfunction and DCM. Mitochondrial defects, such as impaired mitochondrial Ca2+ handling, opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, mitochondrial autophagy, and compromised mitochondrial biogenesis, not only drive diabetic pathology but also contribute to the development of cardiac dysfunction in DCM [47–49]. Exercise has been shown to ameliorate DCM by enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis and improving mitochondrial function. Mechanistically, exercise exerts protective effects on cardiac function, preventing myocardial apoptosis and fibrosis while promoting mitochondrial biogenesis in advanced DCM through the activation of PGC-1α and Akt signaling pathways [50]. As a key regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, PGC-1α plays a crucial role in myocardial energy metabolism. In db/db mice, moderate-intensity exercise restored mitochondrial biogenesis, permeability, and oxidative capacity, as evidenced by improved oxygen consumption rate (OCR), ATP production, and connexin 43 levels, thereby preventing DCM-associated contractile dysfunction [51]. Connexin 43, a major component of adult heart gap junctions, is essential for the coupling of myocardial cell networks, mitochondrial networks, and microvascular endothelial networks, playing a critical role in nutrient and electrolyte balance [52]. Exercise-induced mitochondrial improvements are further characterized by increased mitochondrial quantity, upregulation of mitochondrial biogenesis proteins such as PGC-1α and mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), reduced proton leakage and reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, increased oxygen consumption, and enhanced oxidative phosphorylation, all of which collectively preserve cardiac contractility under diabetic conditions [17, 18]. Additionally, exercise training, especially when combined with metformin, improves hyperglycemia, reduces cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis, preserves mitochondrial function, and maintains intracellular calcium homeostasis in diabetic rats [53]. Furthermore, exercise has been shown to enhance the cardiac effects of FGF21 by activating AMPK-mediated FOXO3 phosphorylation, which upregulates SIRT3, reversing diabetes-induced mitochondrial enzyme hyperacetylation and dysfunction [54]. These findings highlight exercise as a multifaceted intervention that targets mitochondrial pathology at multiple levels, from biogenesis and dynamics to oxidative capacity and network coupling, offering a promising approach to mitigating DCM progression.

Exercise reduces oxidative stress

Exercise training reduces oxidative stress in diabetic hearts, which is crucial for preventing cardiac remodeling and improving heart function in DCM. ROS are natural byproducts of oxygen metabolism, and moderate levels of ROS are considered intracellular signaling molecules. However, excessive ROS contributes to various cardiovascular complications, including inflammation, apoptosis, and accelerated fibrosis, all of which exacerbate cardiac dysfunction [55, 56]. Exercise exerts its cardioprotective effects by directly targeting NOX activity and enhancing antioxidant defenses. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases (NOXs), comprising transmembrane (gp91phox, p22phox) and (cytosolic p47phox, p67phox) subunits, are major sources of ROS in diabetic hearts [57, 58]. Exercise significantly downregulates the expression of NOX subunits, particularly p47phox and p67phox, thereby reducing ROS overproduction and attenuating oxidative damage [19]. Additionally, low-intensity exercise enhances the activity of antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), and catalase (CAT), in cardiac tissue, thereby alleviating oxidative stress, and preserving myocardial integrity [59]. Furthermore, exercise modulates plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) levels, with effects varying by intensity, and upregulates the antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2, contributing to its cardioprotective effects [60, 61]. Thus, by directly influencing NOX-mediated oxidative stress and enhancing endogenous antioxidant defenses, exercise serves as a crucial intervention for mitigating oxidative damage in DCM.

Exercise modulates MiRNA regulation

miRNAs are endogenous, non-coding small RNA molecules that play crucial roles in various biological processes. Several miRNAs have been identified as key players in large and microvascular complications associated with T2DM [62, 63]. Exercise has emerged as a potent modulator of miRNA expression, offering cardio-protection through the regulation of key molecular pathways. Notably, exercise regulates miRNAs such as miR-486a-5p, miR-206, and miR-195, which suppress apoptotic targets, maintain coronary and cardiac function, and reduce cardiac remodeling [64–67]. Additionally, miR-34a, predominantly expressed in the heart, accelerates endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cell aging by downregulating sirtuin1 (Sirt1), thereby promoting arterial inflammation and age-related CVDs [68, 69]. Swimming-induced irisin has been shown to mitigate diabetic myocardial fibrosis by activating the miR-34a-mediated Sirt1/PGC-1α/FNDC5 signaling pathway [70]. Moreover, HIIT effectively inhibits miR-1 and its downstream apoptotic pathways, demonstrating greater efficacy in reducing DCM progression compared to continuous exercise training [71]. Comparisons between HIIT and moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) further suggest HIIT is a superior strategy for modulating these molecular markers and improving myocardial function in diabetic hearts [66]. These findings highlight the potential of exercise, particularly HIIT, to modulate miRNA networks and mitigate DCM progression.

Exercise attenuates cell death

Cell death is a critical biological process that supports morphogenesis during development and maintains homeostasis post-birth by eliminating damaged, obsolete, or pathogen-infected cells [72]. It can be triggered through programmed cell death mechanisms, such as apoptosis, necrosis, and pyroptosis, or by metabolic disturbances, such as ferroptosis [72]. Cell death is involved in the pathogenesis of DCM, and exercise has been shown to protect cardiac function by mitigating cell death in diabetic hearts. For instance, low-intensity exercise markedly reduces cardiomyocyte apoptosis in cardiac tissue, thereby preserving myocardial integrity [59]. Studies have further demonstrated that exercise exerts cardioprotective effects by preventing myocardial apoptosis, as evidenced by a decreased Bax/Bcl-2 ratio at the protein level in diabetic hearts [50]. Exercise training alleviates cardiac injury in diabetic rats not only by improving oxidative stress and inflammation in cardiac tissue but also by regulating the expression of apoptotic genes through upregulation of BCL2 and downregulation of BAX gene expressions [73]. Additionally, exercise mitigates endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and promotes H2S-mediated cardio-protection, which is associated with reduced pyroptosis [74, 75]. Collectively, these mechanisms underscore the therapeutic potential of exercise in DCM by attenuating cell death and promoting cardiac health.

Exercise ameliorates cardiomyocyte fibrosis

Diabetic cardiac fibrosis is a major pathological factor in DCM, characterized by the excessive deposition of collagen fibers in the heart, leading to impaired left ventricular diastolic function, ultimately resulting in heart dysfunction and heart failure [76]. The activation of myofibroblasts, driven by fibroblast growth factors, results in the deposition of extracellular matrix components, marking the cardiac remodeling process in DCM [77]. The transforming growth factor-beta (TGFβ) signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in the development of diabetic cardiac fibrosis and DCM. During myocardial fibrosis, TGFβ binds to TGFβ receptor 2 (TGFβR2), recruits TGFβR1, and induces its phosphorylation, thereby activating both the canonical Smad pathway and the non-canonical TAK1 pathway, which collectively contributes to the progression of myocardial fibrosis [78]. Exercise has been shown to significantly mitigate myocardial fibrosis in DCM by modulating extracellular matrix components and fibrosis-related factors. For instance, exercise decreases collagen and reticular fiber deposition in the left ventricle, reduces glycogen accumulation, and attenuates the downregulation of metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 mRNA expression [79, 80]. Furthermore, exercise influences titin-dependent myocardial stiffness rather than collagen-dependent fibrosis, enhancing cardiac function in diabetic animals [20]. Aerobic exercise also activates heat shock protein 27 (HSP27), improves myocardial fiber alignment, and restores diastolic function [81]. Studies have demonstrated that exercise increases pro-angiogenic factors, enhances capillary density, and reduces interstitial fibrosis, with MICT showing superior effects compared to HIIT [82]. Systemic exercise training alters extracellular matrix proteins and restores myocardial function, highlighting its therapeutic benefits against DCM [83]. Exercise also reverses changes in myocardial fibrosis factors induced by T2DM, including inhibition of MMP-2, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), TGF-β1, p-Smad2, and p-Smad3, while increasing tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMP)-1 and Smad7 expression [84]. Additionally, the inhibition of P2X7 purinergic receptors (P2X7R) alleviates cardiac fibrosis and apoptosis in T1DM [85]. Aerobic exercise has been shown to partially reverse cardiac remodeling in diabetic mice by inhibiting the expression of P2X7R in myocardial cells [86]. These findings highlight the multifaceted role of exercise in ameliorating diabetic cardiac fibrosis and improving cardiac function.

Dietary factors in treating DCM

Clinical studies on dietary factors and cardiac health in diabetes

Clinical studies investigating the impact of dietary interventions on the development and progression of DCM remain relatively scarce. Current evidence suggests that specific dietary patterns may modulate DCM-related risk factors, as summarized in Table 3. Notably, research has demonstrated that diets rich in medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs), as opposed to long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs), may offer therapeutic benefits. Such MCFA-enriched diets have been shown to enhance load-independent measures of cardiac contractility and significantly reduce plasma levels of sphingolipids, ceramides, and acylcarnitines, which are metabolic markers associated with DCM [13]. Importantly, these observed changes in certain sphingolipids were linked to improved fasting insulin levels, suggesting a beneficial metabolic impact of MCFAs in managing DCM risk factors [13]. In addition, one study demonstrated that a low-carbohydrate diet may benefit DCM patients by promoting significant weight loss, potentially reducing cardiac burden, and improving metabolic profiles [14]. However, dietary interventions appear to have time-dependent effects as evidenced by contrasting outcomes between short-term and long-term very low-calorie diets (VLCDs) regimens. A three-day VLCD intervention was associated with potentially adverse metabolic alterations and impaired cardiac function in T2DM patients [15, 87]. These include elevated plasma non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) and increased myocardial triglyceride (TG) content, which coincide with impaired diastolic function, regardless of pre-existing cardiac complications [15, 87]. In contrast, longer-term VLCD interventions spanning 16 weeks demonstrated more favorable outcomes, including reduced body weight, NEFA levels, and myocardial TG content, along with improved diastolic function in T2DM patients [88, 89]. Furthermore, the 16-week VLCD regimen was particularly beneficial for obese T2DM patients with coronary artery disease, showing reductions in both paracardial white adipose tissue and myocardial fat content, accompanied by increased left ventricular ejection fraction [90]. These findings underscore the complex and time-dependent nature of dietary interventions in DCM management. Considering both metabolic profiles and cardiac function status, tailoring dietary recommendations to individual patient characteristics may be essential for optimizing therapeutic outcomes.

Table 3.

Clinical studies of dietary factors on diabetic patients

| Subjects, age, sex, number | Dietary factors | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with T2DM, 57.6 ± 4.7, M, 11 | Very-low-calorie diet, 3 days |

Plasma NEFA levels and myocardial TG content ↑ E/A ratio ↓ |

Hammer et al. [87] |

| Obese, insulin-treated T2DM patients, 48.3 ± 2.8, MF, 12 | Very-low-calorie diet, 16 weeks |

BMI ↓, hemoglobin A1c ↓ and myocardial TG content ↓ Systolic and diastolic blood pressure ↓, heart rate ↓ Cardiac output ↓, LV mass ↓, E/A ratio ↑ |

Hammer et al. [88] |

| T2DM patients with cardiac complications, 57 ± 3, MF, 14 | Very-low-calorie diet, 3 days | Plasma NEFA levels and myocardial TG content ↑, diastolic cardiac function (E/A ratio (early diastolic filling phase/diastolic atrial contraction) and E deceleration peak) ↓ | Jonker et al. [15] |

| Insulin-dependent T2DM patients, 53 ± 2, MF, 14 | Very-low-calorie diet, 16 weeks | Myocardial TG content ↓, BMI ↓, Left ventricular end-diastolic volume index ↑, E/A ratio ↑ | Jonker et al. [89] |

| Patients with T2DM, 37–65, MF, 16 | Medium-chain fatty acids-rich diet, 2 weeks |

The relatively load-independent measure of cardiac contractility ↑ Plasma sphingolipids, ceramide, and acylcarnitine ↓ |

Airhart et al. [13] |

| Obese T2DM patients with coronary artery disease, 62.2 ± 6.0, MF, 27 | Very-low-calorie diet, 16 weeks | Paracardial white adipose ↓, myocardial fat content ↓, LV mass ↓, heart rate↓, left ventricular ejection fraction ↑ | Eyk et al. [90] |

| Adult patients with DCM, > 18, MF, 17 | Low carbohydrate diet, 16 weeks | Weight ↓, thirst or quality of life - | Kleissl-Muir et al. [14] |

DCM, diabetic cardiomyopathy; MF, male and female; NEFA, non-esterified fatty acid; TG, triglyceride; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; ↑, improved or up; ↓, attenuated or down;–, no changed

Preclinical studies of dietary factors in DCM

Numerous animal studies have investigated the impact of various dietary patterns and specific dietary components on the development and progression of DCM (Table 4), providing actionable insights for potential clinical translation. Protective dietary components identified in these preclinical studies offer promising therapeutic candidates, though their clinical applicability requires systematic validation. For example, phytoestrogens like genistein and daidzein have been shown to reduce cardiac mechanical dysfunction induced by glucotoxicity, highlighting their potential to mitigate diabetes-related cardiac damage [91]. Similarly, combinations of fenugreek seed and onion have been reported to improve cardiac damage associated with diabetes, suggesting their cardioprotective potential in diabetic settings [92]. Notably, Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) supplementation significantly reduces adipokines and markers of cardiomyopathy, such as cardiac enzymes and lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, while also lowering blood glucose levels in diabetic rats [93], thereby offering a promising therapeutic approach. Additionally, a study examining the effects of ketogenic diets (KDs) on Ca²⁺ homeostasis and electrophysiology in DCM found that KDs may help restore sodium and calcium balance disrupted by diabetes, thereby contributing to their cardioprotective effects [94].

Table 4.

Preclinical studies of dietary factors on DCM

| Animals | Dietary factors | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transgenic MHC-PPAR mice | HFD, 4 or 8 weeks | Cardiomyopathic phenotype ↑ | Finck et al. [96] |

| Wistar rats | n-6 PUFA diet, 4 weeks | Caspase-3 activity ↓, cardiac necrosis ↑ | Ghosh et al. [97] |

| Myocytes from adult male Sprague-Dawley rats | Phytoestrogenic isoflavones daidzein (50 mM) or genistein (20 mM) | Mechanical dysfunctions ↓ | Hintz et al. [91] |

| Female Wistar rats | Taurine, 4 weeks | Apoptosis of cardiac myocyte ↓ | Li et al. [120] |

| Male Sprague–Dawley rats | 2000 IU of vitamin E/kg/day, 8 weeks | LV function ↑, myocardial 8-iso-prostaglandin F2alpha and oxidized glutathione accumulation ↓ | Hamblin et al. [110] |

| Male Balb/c mice | CA or EA at 2 g was mixed with 98 g power diet/day, 12 weeks | TG ↓, anti-coagulatory, anti-oxidative, and anti-inflammatory protection in cardiac tissue | Chao et al. [102] |

| Male Wistar rats | Sulfurous mineral water/day, 7 weeks | Cardiac GSH level ↑, enhanced expression of NF-κB, the profibrogenic and apoptotic parameters ↓ | El-Seweidy et al. [103] |

| Sprague-Dawley rats | Riboflavin (20 mg kg − 1 per day), 8 weeks | Left ventricular systolic and diastolic function ↑, activation of SOD and the level of HO-1 protein ↑, CTGF ↓ | Wan et al. [112] |

| db/db mice | Coenzyme Q (10) for 10 weeks | Superoxide generation ↓, diastolic dysfunction ↓, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and fibrosis in db/db mice ↓ | Huynh et al. [23] |

| Male C57BL/6 mice | HFD for 16 months | Normal arterial pressure, altered vascular reactivity (vasoconstriction), cardiac contractility reserve ↓, heart mass ↑, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, cardiac fibrosis, heart metabolic compensations. | Calligaris et al. [128] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Mangiferin (20 mg/kg/day), 16 weeks | DCM ↓, accumulation of myocardial collagen (Prevented) | Hou et al. [126] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | 1,25-(OH)2 D3 therapy, 6 weeks | Myocardial fibrosis ↓ | Wang et al. [127] |

| Male C57BL/6J mice | Sulforaphane, 0.5 mg/kg/day, five days a week, 4 months | Cardiac oxidative stress-induced inhibition of LKB1/AMPK signaling pathway | Zhang et al. [104] |

| Male Wistar rats | Zn, 15 mg/kg/day, 56 days | DCM ↓, oxidative stress and autophagy in cardiac tissue ↓ | Lu et al. [107] |

| Cardiomyocytes from male Sprague-Dawley rats | Conjugated linoleic acid, 24–48 h | Cardiomyocyte functional and structural abnormalities | Milad Aloud et al. [98] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Mangiferin (20 mg/kg/day) for 16 weeks | DCM ↓, inflammatory cytokines ↓, ROS accumulation ↓, AGE/RAGE production ↓, NF-κB nuclear translocation ↓ | Hou et al. [111] |

| Male Wistar rats | Protocatechuic acid, 50–100 mg/kg/day, 28 days | Pro-inflammatory cytokines ↓, myocardial physiology (Restored) | Bhattacharjee et al. [22] |

| db/db mice | Caloric restriction, 4 weeks | Cardiac PPARα ↑, myocardial inflammation ↓ | Cohen et al. [117] |

| Nrf2-KO, MT-KO, and WT mice | Sulforaphane, 0.5 mg/kg 5 days a week for 4 months along with continual feeding with either HFD or ND | Cardiac dysfunction ↓, cardiac oxidative damage, inflammation, fibrosis, and hypertrophy ↓, Nrf2 and MT expressions ↑ | Gu et al. [105] |

| db/db and C57BL/6J mice | Zn, 10/30/90 mg/day, for 6 months | DCM ↑ (Zinc deficiency) | Wang et al. [108] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (vitamin D) | Pathological changes ↓, Fas/FasL expression ↓, myocardial cell apoptosis ↓ | Zeng et al. [121] |

| Male Wistar rats | Fenugreek seeds and onion, 6 weeks | Pathological changes in the cardiovascular system ↓ | Pradeep et al. [92] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Western diet, 18 weeks | Hyperglycemia, AGEs levels ↑, insulin levels ↑, Hypertriglyceridemia, End-diastolic pressure ↑, Left ventricle hypertrophy, Collagen deposition ↑, PAI-1 levels in the heart ↑ | Verboven et al. [95] |

| db/db mice | Caloric restriction diet, 4 weeks | DCM ↓ | Waldman et al. [118] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Tea polyphenol, 4 weeks | DCM ↓, glucose and lipid metabolism ↑ | Zhou et al. [123] |

| Goto-Kakizaki rats | Low-carbohydrate low-protein ketogenic diet, 62 weeks | DCM ↑, maladaptive cardiac metabolic modulation and lipotoxicity | Abdurrachim et al. [99] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Coriolus versicolor, 25 mg/kg/day, 12 weeks | Cardiac inflammation ↓, cardiac fibrosis ↓, increased cardiac inflammation in cardiac fibroblast cells ↓ | Wang et al. [116] |

| db/db mice | Ketogenic diet, 8 weeks | Cardiac dysfunction ↓, apoptosis ↓ | Guo et al. [124] |

| AMPKα2-KO mice | Sulforaphane, 3 months | Progression of cardiac dysfunction, remodeling (hypertrophy and fibrosis), inflammation, and oxidative damage (Prevented) | Sun et al. [106] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Cola nitida infusion at 150 or 300 mg/kg body weight, 6 weeks | Oxidative imbalance ↓, ACE activity ↓, lipid accumulation ↓, dysmetabolic pathways ↓, maintaining myocardial morphology in hearts | Erukainure et al. [109] |

| C57BL/6 male mice | Krill oil, 2.79 g/d, 24 weeks | Cardiac pathological injuries ↓, inflammation ↓, oxidative stress ↓ | Sun et al. [101] |

| Male Wistar rats | Green tea catechins, 90 mg/day, 28 days | Cardiomyocyte contractility ↑ | Vilella et al. [21] |

| db/db mice | RWPH (gavage at 1.5 mg/kg), RWPE (gavage at 0.5 g/kg), RWOL (gavage at 0.3 mg/kg), for 18 weeks | DCM ↓, autophagy ↑, apoptosis ↓, gut microbiota dysbiosis and metabolic dysregulation (Reversed) | Yang et al. [125] |

| Male Wistar rats | Ketogenic diet, 6 weeks | DM-dysregulated Na+ and Ca2+ homeostasis ↓ | Lee et al. [94] |

| Rats | Ketogenic diet, 6 weeks | DCM ↓, FA metabolism ↓, ketone utilization ↑, endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation ↓ | Trang et al. [119] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | High-sucrose diet, 14 weeks | Cardiac ROS dysregulation, perivascular fibrosis, impaired LV diastolic function | Velagic et al. [113] |

| Male Wistar rats | CoQ10, 5 g/kg, 21 days | Profile of adipokines ↓, cardiomyopathy markers (cardiac enzymes and LPPLA2) ↓, glucose levels ↓ | Jbrael et al. [93] |

| Male Wistar rats | Ginger extract (100 mg/kg) and omega-3 fatty acids (50, 100, and 150 mg/kg), 6 weeks | DCM ↓, inflammation, apoptosis and oxidative damage of the heart ↓, blood glucose and cardiac expression of TRPM2 and TRPV2 ↓ | Yu et al. [122] |

AGEs, advanced glycation end products; CA, caffeic acid; CoQ10, Coenzyme Q10; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; DCM, diabetic cardiomyopathy; EA, ellagic acid; FA, fatty acid; GSH, glutathione; HFD, high-fat diet; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; KO, knockout; LPPLA2, lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2; LV, left ventricle; MHC, myosin heavy chain; MT, metallothionein; ND, normal diet; NF-κB, nuclear factor; Nrf2, nuclear transcription factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; RAGE, receptor for AGEs; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RWOL, rice wine oligosaccharides; RWPH, rice wine polyphenols; RWPE, rice wine polypeptides; SOD, uperoxide dismutase; TG, triglyceride; TRPM2, transient receptor potential melastatin 2; TRPV2, Transient receptor potential vanilloid channel 2; WT, wild-type; ↑, improved or up; ↓, attenuated or down

Conversely, diet-induced DCM exacerbation in animal models carries urgent public health implications. Rodents fed high-sugar diet (HSD) or WD develop cardiac phenotypes strikingly similar to human T2DM and DCM [95], reinforcing observational data linking processed food consumption with accelerated cardiomyopathy in diabetic populations. Additionally, mice with cardiomyopathy due to MHC-PPAR overexpression fed a high long-chain triglyceride (LCT) diet exhibited worsened cardiomyopathy phenotypes, which were reversible upon cessation of the HFD, but not in mice fed diets high in medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) [96]. Short-term exposure to n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in diabetic rats also led to cardiac metabolic and contractile abnormalities [97]. Moreover, high-glucose conditions in cardiomyocytes induce functional and structural abnormalities that can be prevented by pretreatment with conjugated linoleic acid, possibly through the activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) pathways [98]. Furthermore, low-carbohydrate low-protein KDs appear to exacerbate DCM in Goto-Kakizaki rats, potentially due to dysregulated cardiac metabolism and lipotoxicity [99].

Overall, these findings highlight the complex relationship between diet and DCM, emphasizing that while certain dietary components may inhibit DCM progression, others particularly unhealthy dietary factors such as HFD, HSD, or WD could exacerbate the condition. These preclinical insights underscore the critical need for well-designed clinical trials to substantiate these observations and establish evidence-based dietary recommendations for DCM management and prevention.

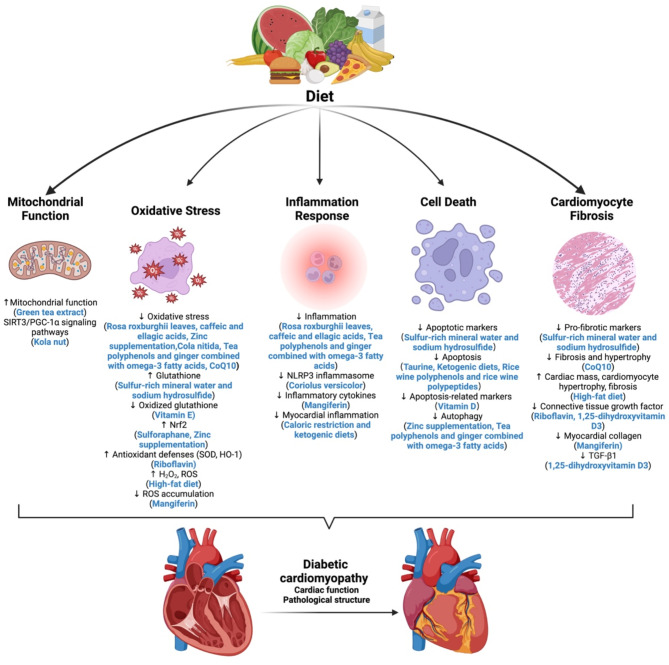

Potential mechanisms of dietary factors on DCM

Dietary factors play a significant role in either mitigating or exacerbating DCM through diverse mechanisms, including modulation of mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, inflammation, cell death, and cardiomyocyte fibrosis (Fig. 2). Importantly, the same dietary factor may influence DCM via multiple pathways, highlighting the complex and multifaceted role that diet plays in DCM management. These mechanistic insights not only advance our understanding of disease pathogenesis but also point to potential therapeutic targets; however, further clinical validation is essential to translate these findings into practice.

Fig. 2.

Mechanisms of dietary factors targeting DCM. Dietary factors impact DCM by modulating mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, inflammation, cell death, and cardiomyocyte fibrosis. Abbreviations: DCM, Diabetic cardiomyopathy

Dietary effects on mitochondrial function

Mitochondrial dysfunction is increasingly acknowledged as a significant contributor to the cardiac pathophysiology associated with diabetes [100]. For instance, green tea extract (GTE) has been shown to restore impaired contractility in diabetic cardiomyocytes by preserving mitochondrial function, maintaining energy availability, and regulating key proteins such as sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase [21]. Additionally, the SIRT3/PGC-1α signaling pathways have been identified as potential molecular targets of kola nut, suggesting a role in mitochondrial function and energy regulation [101]. These findings suggest that targeting mitochondrial pathways through diet could be a promising strategy for DCM treatment, although clinical studies are needed to evaluate efficacy and safety in patients.

Dietary effects on oxidative stress

Oxidative stress is a critical driver of DCM, and various dietary components can modulate this process. Protocatechuic acid isolated from the Sansevieria roxburghiana rhizomes mitigates DCM by enhancing glucose metabolism while reducing oxidative stress and inflammation [22]. Similarly, caffeic and ellagic acids protect cardiac tissue in diabetic models through their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticoagulant properties [102]. Additional interventions, such as sulfur-rich mineral water and sodium hydrosulfide, improve cardiac health by enhancing glutathione levels and reducing pro-fibrotic and apoptotic markers [103]. Sulforaphane prevents DCM-related cardiac dysfunction and oxidative damage by upregulating Nrf2 and metallothionein expression via the AMPK/AKT/GSK3β signaling pathway [104–106]. Furthermore, zinc supplementation mitigates oxidative stress and autophagy in cardiac tissues, while zinc deficiency exacerbates these conditions, potentially by suppressing Nrf2 function [107, 108]. Cola nitida infusion alleviates oxidative stress and maintains myocardial morphology in T2DM rats [109]. Dietary vitamin E supplementation improves heart failure in DCM by inhibiting myocardial generation of 8-isoprostane F2α and oxidized glutathione [110]. Mangiferin significantly improves DCM by suppressing ROS accumulation, blocking advanced glycation end-product/receptor (AGE/RAGE) signaling, and preventing NF-κB nuclear translocation, suggesting potential therapeutic benefits [111]. Riboflavin supplementation significantly improves cardiac function in diabetic rats by boosting antioxidant defenses (SOD, HO-1) [112]. In contrast, unhealthy dietary patterns may exacerbate oxidative stress. For instance, HFDs can induce cardiotoxic effects through intracellular toxins, with peroxisome-generated H2O2 or other ROS as potential mediators [96], and diabetic rats on high-sucrose and HFDs exhibit cardiac ROS imbalance and perivascular fibrosis [113].

Dietary effects on inflammation response

The innate immune system and chronic inflammation play a crucial role in the occurrence and development of DCM [114, 115]. Several dietary factors modulate inflammatory responses in DCM. For instance, coriolus versicolor inhibits TGF-β1/Smad signaling and NLRP3 inflammasome activation, highlighting its therapeutic potential [116]. In parallel, protocatechuic acid, caffeic acid and ellagic acid also provide protective effects on cardiac tissue in diabetic mice by inhibiting inflammation [22, 102]. Mangiferin improves DCM by inhibiting inflammatory cytokine release [111]. Furthermore, caloric restriction (CR) and KDs reduce myocardial inflammation by modulating fatty acid metabolism and enhancing ketone utilization, positioning these dietary interventions as potential strategies against DCM [117–119].

Dietary effects on cell death

Dietary interventions can influence cell death, a critical process in DCM pathogenesis. Taurine protects against DCM by downregulating AT2 and inhibiting apoptosis in cardiac cells [120]. Vitamin D supplementation may exert cardioprotective effects by downregulating apoptosis-related markers such as Fas and Fas ligand [121]. Tea polyphenols and ginger combined with omega-3 fatty acids protect against DCM by modulating autophagy and reducing oxidative stress and inflammation [122, 123]. In T2DM mice, KDs improve cardiac dysfunction by inhibiting apoptosis via activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway [124]. Additionally, rice wine polyphenols and rice wine polypeptides protect against DCM by promoting autophagy, inhibiting apoptosis, and reversing gut microbiota dysbiosis and metabolic disorders [125]. Zinc supplementation can prevent DCM by reducing oxidative stress and autophagy in cardiac tissue [107].

Dietary effects on cardiomyocyte fibrosis

Cardiomyocyte fibrosis, a hallmark of DCM, is influenced by various dietary factors. CoQ10 treatment in db/db mice not only reduces oxidative stress and improves cardiac function but also decreases fibrosis and hypertrophy [23]. Riboflavin supplementation significantly improves cardiac function in diabetic rats by reducing CTGF levels [112]. Moreover, mangiferin prevents myocardial collagen accumulation, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 has shown partial protective effects against myocardial fibrosis in diabetic rats by inhibiting TGF-β1 and CTGF expression [126, 127]. Conversely, prolonged HFD has been associated with altered vascular reactivity, reduced cardiac contractile reserve, increased cardiac mass, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, fibrosis, and cardiac metabolic compensation [128].

Synergistic effects of exercise and dietary interventions in DCM management

Current evidence regarding the combined therapeutic potential of exercise and dietary modifications in DCM remains scant. A preclinical study assessed the modulatory effects of endurance training combined with prebiotic xylooligosaccharide on cardiovascular risk in rats with T1DM, finding that exercise, whether alone or in conjunction with prebiotic xylooligosaccharide, had beneficial effects on cardiac mitochondrial enzymology and histopathology [129]. Several studies demonstrate that structured exercise regimens effectively mitigate cardiac dysfunction in various diet-induced DCM models, including those utilizing HFD or high-fructose diet and WD [45, 46, 67, 75]. While these animal studies provide mechanistic insights, significant translational gaps persist. There remains an urgent need for rigorously designed clinical trials to systematically evaluate multimodal interventions combining optimized exercise protocols with evidence-based dietary strategies. Such investigations should aim to elucidate potential synergistic effects while establishing dose-response relationships, ultimately informing the development of comprehensive lifestyle intervention frameworks for DCM prevention and management.

Conclusions and perspectives

DCM, a leading cause of mortality among diabetic patients, remains a significant clinical challenge despite advances in therapeutic strategies. Lifestyle modifications play a fundamental role in managing DCM. This review highlights the critical role of exercise and diet in managing DCM. Evidence-based exercise protocols recommend that DCM patients engage in ≥ 150 min weekly of moderate-to-vigorous aerobic activity, supplemented by resistance training to enhance cardiovascular and metabolic function. Emerging data suggest that HIIT may offer additional cardioprotective benefits. Exercise exerts beneficial effects through multiple mechanisms, including enhancing mitochondrial function, reducing oxidative stress, regulating miRNA modifications, and modulating cell death and cardiomyocyte fibrosis. Dietary factors are diverse and can either exacerbate or ameliorate DCM via distinct pathways, primarily involving mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, inflammation, cell death, and cardiomyocyte fibrosis. Protective strategies include prolonged VLCDs and KDs, supplemented with cardioprotective micronutrients such as CoQ10, zinc, and antioxidant vitamins. Conversely, pro-inflammatory dietary patterns, particularly chronic consumption of HFD, HSD, and WD, exacerbate myocardial dysfunction.

However, significant gaps remain in our understanding of how sex, race, and ethnicity influence the efficacy of these interventions. Although women have a lower overall prevalence of heart failure and cardiomyopathy and tend to develop coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction later than men, the incidence of metabolism-related cardiomyopathies, such as DCM and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), is rising, increasing heart failure risk fivefold in women compared to twofold in men [130, 131]. However, the intricate mechanisms underlying sex-specific differences in DCM remain incompletely understood. Sex hormones play a key role, with both testosterone and estrogen exerting cardioprotective effects. Premenopausal women benefit from higher estrogen levels, but this protection diminishes post-menopause due to estrogen decline [132]. The impact of low testosterone on DCM and its molecular mechanisms remains underexplored. Additionally, the complex interplay between estrogen deficiency, CVDs, and T2DM is not fully understood, and whether estrogen replacement therapy can mitigate DCM risk in long-term diabetics remains uncertain [132]. Furthermore, sex-specific variations in metabolism and calcium handling, NOS activity, and PPARα may also contribute to these differences [131]. Future research should prioritize sex-stratified analyses to refine intervention strategies. Additionally, baseline characteristics of patients with DCM exhibit notable racial and ethnic differences, with studies showing that Black and Hispanic participants present higher risk profiles [133]. This finding underscores the need for future exercise and dietary intervention studies to address the unique challenges faced by individuals from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, with the ultimate goal of reducing disparities and improving clinical outcomes in DCM [134].

Most existing studies rely heavily on animal models, underscoring the urgent need for large-scale, multicenter interventional studies to validate these findings in human populations. Future research should aim to translate preclinical insights into well-designed clinical trials that ensure dietary and exercise recommendations are both evidence-based and patient-centered. Such trials should account for individual variability, including age, sex, and comorbid conditions, and employ standardized protocols and robust outcome measures. This approach will help bridge the gap between experimental research and clinical practice, ultimately paving the way for more effective, personalized interventions for metabolic and cardiovascular conditions. Notably, most current studies focus on diabetic populations, assessing changes in cardiac structure and function following exercise and dietary interventions. While these findings provide indirect insights into DCM management, they have notable limitations. Given that DCM patients already exhibit distinct pathological alterations, intervention studies specifically targeting this population hold greater clinical relevance. Future research should prioritize dedicated clinical trials on DCM to elucidate the direct effects of exercise and dietary interventions on cardiac remodeling, thereby optimizing clinical management strategies.

Additionally, emerging dietary strategies, such as intermittent fasting and other time-restricted eating show promise in improving metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes [135], warranting further investigation in DCM patients. Given the shared mechanistic pathways between exercise and dietary interventions in improving DCM, comparative studies are needed to identify the optimal combinations of exercise regimens and dietary patterns, as well as their synergistic effects. A crossover study design is recommended to evaluate the integrated effects of various exercise modalities (e.g., aerobic and resistance training) and specific dietary approaches. Such research could inform the development of comprehensive management strategies that maximize cardiac benefits and slow disease progression. Additionally, DCM patients often present with diastolic dysfunction, progression to systolic dysfunction, abnormal electrophysiology, and an elevated risk of heart failure [136]. While most current interventions focus on improving cardiac function, electrophysiological remodeling is a key pathological basis for the transition from DCM to heart failure. Therefore, future studies should establish a multimodal assessment framework incorporating techniques such as cardiac magnetic resonance with late gadolinium enhancement to systematically evaluate the effects of combined exercise-diet interventions on electrophysiological parameters, including action potential duration and conduction velocity. Moreover, leveraging advanced techniques such as single-cell spatial-temporal analysis will help elucidate cell-specific responses and uncover the precise mechanisms operating across different stages of the disease. This approach would enhance our understanding of the clinical value of non-pharmacological interventions and support the development of more targeted therapeutic strategies.

Finally, translating these findings into personalized dietary and exercise guidelines, informed by mechanistic insights and clinical evidence, is crucial for optimizing DCM management. Future research should also explore personalized pharmacological interventions that integrate lifestyle modifications to enhance therapeutic efficacy and improve patient outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- ADA

American Diabetes Association

- AGE/RAGE

Advanced glycation end-product/receptor

- CAT

Catalase

- CTGF

Connective tissue growth factor

- CoQ10

Coenzyme Q10

- CVDs

Cardiovascular diseases

- DCM

Diabetic cardiomyopathy

- GSH-Px

Glutathione peroxidase

- GTE

Green tea extract

- HFD

High-fat diet

- HFpEF

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- HFrEF

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

- HIIT

High-intensity interval training

- HSD

High-sugar diet

- KDs

Ketogenic diets

- LCFAs

Long-chain fatty acids

- LCT

Long-chain triglyceride

- MCFAs

Medium-chain fatty acids

- MCTs

Medium-chain triglycerides

- MICT

Moderate-intensity continuous training

- miRNA

microRNA

- MIT

Moderate-intensity training

- MMP

Metalloproteinase

- NEFA

Non-esterified fatty acids

- NOS

Nitric oxide synthase

- OCR

Oxygen consumption rate

- PPAR

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- PUFAs

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- STZ

Streptozotocin

- TFAM

Mitochondrial transcription factor A

- TG

Triglyceride

- TIMP

Tissue inhibitors of MMPs

- T1DM

Type 1 diabetes mellitus

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- VLCD

Very low-calorie diet

- WD

Western diet

Author contributions

Yan Tian and Xianghui Fu conceived the idea; Ling Zhong performed the literature search and drafted the manuscript; Xiaojie Hou edited and revised the manuscript; Yan Tian and Xianghui Fu supervised and revised the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project (2023ZD0507500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92157205, and 81970561), and the 1.3.5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZYJD23005).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ling Zhong and Xiaojie Hou contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yan Tian, Email: ytian@scu.edu.cn.

Xianghui Fu, Email: xfu@scu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Global regional, national burden of diabetes. From 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet. 2023;402(10397):203–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seferović PM, Paulus WJ. Clinical diabetic cardiomyopathy: a two-faced disease with restrictive and dilated phenotypes. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(27):1718–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levelt E, Gulsin G, Neubauer S, McCann GP. Mechanisms in endocrinology: diabetic cardiomyopathy: pathophysiology and potential metabolic interventions state of the art review. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;178(4):R127–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan Y, Zhang Z, Zheng C, Wintergerst KA, Keller BB, Cai L. Mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy and potential therapeutic strategies: preclinical and clinical evidence. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(9):585–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moka MK, K SD, George M. Emerging clinical approaches in diabetic cardiomyopathy: insights from clinical trials and future directions. Acta Diabetol. 2025;62(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilbert RE, Krum H. Heart failure in diabetes: effects of anti-hyperglycaemic drug therapy. Lancet. 2015;385(9982):2107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oe H, Nakamura K, Kihara H, Shimada K, Fukuda S, Takagi T, et al. Comparison of effects of sitagliptin and Voglibose on left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes: results of the 3D trial. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2015;14:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jia G, DeMarco VG, Sowers JR. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(3):144–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schrauwen-Hinderling VB, Meex RC, Hesselink MK, van de Weijer T, Leiner T, Schär M, et al. Cardiac lipid content is unresponsive to a physical activity training intervention in type 2 diabetic patients, despite improved ejection fraction. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011;10:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hordern MD, Coombes JS, Cooney LM, Jeffriess L, Prins JB, Marwick TH. Effects of exercise intervention on myocardial function in type 2 diabetes. Heart. 2009;95(16):1343–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sacre JW, Jellis CL, Jenkins C, Haluska BA, Baumert M, Coombes JS, et al. A six-month exercise intervention in subclinical diabetic heart disease: effects on exercise capacity, autonomic and myocardial function. Metabolism. 2014;63(9):1104–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassidy S, Thoma C, Hallsworth K, Parikh J, Hollingsworth KG, Taylor R, et al. High intensity intermittent exercise improves cardiac structure and function and reduces liver fat in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2016;59(1):56–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Airhart S, Cade WT, Jiang H, Coggan AR, Racette SB, Korenblat K, et al. A diet rich in Medium-Chain fatty acids improves systolic function and alters the lipidomic profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: a pilot study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(2):504–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleissl-Muir S, Owen A, Rasmussen B, Zinn C, Driscoll A. Effects of a low carbohydrate diet on heart failure symptoms and quality of life in patients with diabetic cardiomyopathy: a randomised controlled trial pilot study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2023;33(12):2455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonker JT, Djaberi R, van Schinkel LD, Hammer S, Bus MT, Kerpershoek G, et al. Very-low-calorie diet increases myocardial triglyceride content and decreases diastolic left ventricular function in type 2 diabetes with cardiac complications. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(1):e1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu G, Li Y, Hu Y, Zong G, Li S, Rimm EB, et al. Influence of lifestyle on incident cardiovascular disease and mortality in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(25):2867–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ko TH, Marquez JC, Kim HK, Jeong SH, Lee S, Youm JB, et al. Resistance exercise improves cardiac function and mitochondrial efficiency in diabetic rat hearts. Pflugers Arch. 2018;470(2):263–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang SY, Zhu S, Wu J, Zhang M, Xu Y, Xu W, et al. Exercise enhances cardiac function by improving mitochondrial dysfunction and maintaining energy homoeostasis in the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Mol Med (Berl). 2020;98(2):245–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma NM, Rabeler B, Zheng H, Raichlin E, Patel KP. Exercise training attenuates upregulation of p47(phox) and p67(phox) in hearts of diabetic rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:5868913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S, Liang M, Gao D, Su Q, Laher I. Changes in Titin and collagen modulate effects of aerobic and resistance exercise on diabetic cardiac function. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2019;12(5):404–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vilella R, Izzo S, Naponelli V, Savi M, Bocchi L, Dallabona C et al. In vivo treatment with a standardized green tea extract restores cardiomyocyte contractility in diabetic rats by improving mitochondrial function through SIRT1 activation. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Bhattacharjee N, Dua TK, Khanra R, Joardar S, Nandy A, Saha A, et al. Protocatechuic acid, a phenolic from sansevieria roxburghiana leaves, suppresses diabetic cardiomyopathy via stimulating glucose metabolism, ameliorating oxidative stress, and inhibiting inflammation. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huynh K, Kiriazis H, Du XJ, Love JE, Jandeleit-Dahm KA, Forbes JM, et al. Coenzyme Q10 attenuates diastolic dysfunction, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis in the Db/db mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2012;55(5):1544–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Askin L, Cetin M, Tasolar H, Akturk E. Left ventricular myocardial performance index in prediabetic patients without coronary artery disease. Echocardiography. 2018;35(4):445–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng J, Cheng J, Zheng S, Zhang L, Guo X, Zhang J, et al. Physical exercise and its protective effects on diabetic cardiomyopathy: what is the evidence?? Front Endocrinol. 2018;9:729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seo DY, Ko JR, Jang JE, Kim TN, Youm JB, Kwak HB et al. Exercise as a potential therapeutic target for diabetic cardiomyopathy: insight into the underlying mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(24). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Li S, Culver B, Ren J. Benefit and risk of exercise on myocardial function in diabetes. Pharmacol Res. 2003;48(2):127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kemps H, Kränkel N, Dörr M, Moholdt T, Wilhelm M, Paneni F, et al. Exercise training for patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: what to pursue and how to do it. A position paper of the European association of preventive cardiology (EAPC). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26(7):709–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marwick TH, Ritchie R, Shaw JE, Kaye D. Implications of underlying mechanisms for the recognition and management of diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(3):339–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okada S, Hiuge A, Makino H, Nagumo A, Takaki H, Konishi H, et al. Effect of exercise intervention on endothelial function and incidence of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2010;17(8):828–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.5. Lifestyle management: standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S46–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riehle C, Bauersachs J. Of mice and men: models and mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2018;114(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jasińska-Stroschein M. The current state of preclinical modeling of human diabetic cardiomyopathy using rodents. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;168:115843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeBlieux PM, Barbee RW, McDonough KH, Shepherd RE. Exercise training improves cardiac performance in diabetic rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1993;203(2):209–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]