Abstract

Background

Globally, 27% of ever-partnered women aged 15–49 have experienced physical, sexual, or intimate partner violence at least once in their lifetime. In Saudi Arabia, domestic violence (DV) remains a concern despite cultural and economic advancements. This study aims to measure the prevalence and factors associated with DV as well as childhood trauma (CT) in the Al Hasa region.

Method

A cross-sectional study was conducted on 503 married women by using convenient sampling reporting DV and CT using two validated questionnaires, respectively. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the numbers and percentages. Pearson’s r correlation was applied to investigate the correlation between risk factors. The multilayer perceptron model has been applied to estimate the most important factors contributing to DV and CT.

Results

Out of 503 respondents, most of them had low experience of DV and childhood trauma, while the prevalence of DV was 4.86%, with controlling behavior of the intimate partner (6.09%) and psychological violence most commonly reported. CT was experienced by 18.90% of respondents, primarily emotional neglect (31.44). The median score of DV was 1.99 (0.81), and that of CT was 2.15(0.45). Among the DV subscales, the median score of psychological violence (2.00, IQR = 0.50) and controlling behavior (2.25 with IQR 0.50) was higher compared to physical and sexual violence, whereas the emotional neglect subscale mean score was the highest among the CT subscales, 2.50 (0.50). DV and childhood trauma were significantly associated with BMI ( < 0.001) and education of women (

< 0.001) and education of women ( < 0.001) respectively. The result of ML model showed that the influential predictors of DV and CT are physical violence and physical neglect respectively.

< 0.001) respectively. The result of ML model showed that the influential predictors of DV and CT are physical violence and physical neglect respectively.

Conclusion

The present study revealed a positive correlation between CT and DV. Women who experienced emotional neglect or abuse during childhood were more likely to report controlling behaviors and psychological violence in their relationships. CT was reported more frequently than DV and women with higher education levels reported greater childhood trauma. Even with low prevalence, such sensitive subjects must not be discredited. Saudi women should embrace education, employment, and awareness of their rights with the rapid societal change, marking a new beginning for women’s empowerment and safety.

Keywords: Domestic violence, Intimate partner violence, Childhood trauma, Women empowerment, Women rights

Introduction

Domestic violence (DV) is widely documented as a serious public health issue rooted in structural inequalities, often related with gender inequalities. Globally, one in four ever-partnered women aged between 15 and 49 years (27%; UI 23–31%) have experienced physical, sexual, or intimate partner violence at least once in their lifetime [1]. The United Nations (UN) defines domestic abuse, also discussed as intimate partner violence (IPV), as a pattern of forced, threatening, or harmful behaviors including physical, sexual, emotional, or psychological abuse used to exert power and control over an intimate partner [2].

Global estimates specify regional variations in DV prevalence, with the lowest lifetime IPV rates observed in Central Europe (16%; UI 12–21%), Central Asia (18%; UI 13–24%), and Western Europe (20%; UI 15–26%). In contrast, Central Sub-Saharan Africa (32%; UI 22–43%), Oceania (excluding Australia and New Zealand) (29%; UI 19–40%), and South Asia (19%; UI 12–27%) reported the highest prevalence [1]. These figures highlight the stark differences between high-income and low-income regions. Despite being one of the most extensive studies covering 366 studies across 161 countries, KSA was not included in these estimates. KSA, a high-income country with distinct cultural and gender roles, continues to face challenges regarding DV. Several studies have documented its prevalence across various regions. A 2010 study in Al Hasa reported a 39.3% lifetime prevalence of DV among women [3], while 2012 data from Al Madinah estimated it at 34% [4]. A study in Jeddah also found a 34% prevalence and a 2015 study in Taif reported an 11.9% prevalence of IPV among female primary healthcare patients. More recent data from the Western region (2017–2018) found a lifetime prevalence of 33.24%. In Riyadh, a 2021 study involving 1,883 married Saudi women aged 30–75 years reported a lifetime DV prevalence of 43.0% [5]. Reports also indicate an increased risk of family violence and child abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic [6]. However, with rapid socioeconomic reforms, including increased gender equality measures and rising female workforce participation (0.097% increase in 2022) [7], updated research on DV in Saudi Arabia is needed. This study aims to update the prevalence of DV in the Al Hasa region after more than a decade and to investigate its correlates, particularly childhood trauma (CT), which is a well-documented risk factor for DV victimization [8]. Multiple risk factors contribute to DV and its association with childhood trauma. Structural and gender-based inequalities, financial dependency, and cultural norms have been linked to higher DV prevalence. CT has been identified as a strong predictor of DV oppression in adulthood. Women who face adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are at higher risk of entering abusive relationships and suffering from frequent victimization [9]. Other factors that can be contributing include substance abuse, low educational level, mental health disorders, and socioeconomic stress. Research studies have reported that women with CT exhibit higher levels of anxiety, depression, and PTSD, which further increase their susceptibility to IPV [10]. The consequences of DV and CT spread beyond the individual and impact public health, social arrangements, and economic stability. Victims of DV frequently suffer from severe mental distress, misery, anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Physical effects range from chronic pain, reproductive health issues, and injuries which further increase mortality rates due to suicide [11]. On a public level, DV leads to increased healthcare expenditures, loss of efficiency, and social imbalance. Kids who grow up in fierce households are at greater risk of developing social and emotional issues. DV has also been connected to negative economic consequences, as victims face barriers to education, employment, and financial independence [12].

Saudi Arabia has made noteworthy steps in addressing DV, including legal reforms, support programs, and awareness campaigns. The government has introduced strict laws criminalizing domestic violence, established hotlines and shelters, and promoted community education initiatives to fight gender-based violence. Additionally, the Saudi Vision 2030 initiative emphasizes women’s empowerment and protection against violence [13]. Domestic violence (DV) remains a important public health issue globally, with different prevalence rates across different regions. In Saudi Arabia, despite recent socio-economic improvements promoting women’s empowerment, DV and its association with CT remain under-explored. Past studies have reported inconsistent DV prevalence, often overlooking the psychological and controlling aspects of abuse. The present study examined the factors associated with DV and childhood trauma among females in the Al-Hasa region of Saudi Arabia. By focusing on the Al Hasa region, the research aims to find the answers to the following questions;

Are DV and the controlling behavior of an intimate partner associated in the Al-Hasa region?

Are DV and CT significantly associated with clinical, emotional, and demographic factors?

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study was carried out in the Al-Hasa region of Saudi Arabia. The study is community based cross sectional study that included respondents who visited the hospital. The participants were explained the purpose and objectivity of the study. Further, voluntary participation and any misconceptions regarding the survey were corrected before informed consent was obtained.

Study period

This cross-sectional study was carried out between May 2022 and June 2022 in the Al-Hasa region, of Saudi Arabia.

Target population

The target population for this study would be Saudi married women aged 18 to 65 years residing in the Al-Hasa region of Saudi Arabia.

Inclusion &exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were to have Saudi married women above the age of 18 to 65, while Saudi females less than 18 or above 65 years of age, single, widowed, or divorced, were excluded from this study. However, considering the ethical and safety recommendations for intervention research on violence against women, only one woman of a family was to be included if more than one woman of the same family visited on the same day [14].

Sample size

Based on the Saudi census on the marital status of the population in the Eastern region (Saudi census, n.d.), approximately 53.8% (538 per 1,000) of females were married. Based on,  margin of error and 95% CI, considering the 30% DV proportion (

margin of error and 95% CI, considering the 30% DV proportion ( ) (considered from global prevalence) [https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women], the sample size was estimated to be n = 503.

) (considered from global prevalence) [https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women], the sample size was estimated to be n = 503.

Sampling

The sampling methodology used in the study is convenient sampling and Saudi married women who visited or worked at the participating hospital were approached to participate in this study.

For the computation purpose of effect size, you can use Cramer’s  which is commonly used for chi-square tests with more than 2 × 2 contingency tables.

which is commonly used for chi-square tests with more than 2 × 2 contingency tables.

The formula for Cramer’s  is:

is:

|

1 |

Ethical considerations

This study adhered to the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration for the recruitment of human subjects. Ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB), Almoosa Specialist Hospital, was obtained before initiating the data collection (IRB log number: ARC-22.04.07). The participants received a detailed explanation of the study’s objectives and the purpose of data collection. The voluntary nature of participation and the option to withdraw were explained to the participants. Married women visiting or working at the hospital were approached for the study with complete consideration for their privacy, anonymity, and freedom of participation. Care was taken to approach them when their intimate partner did not accompany them, as it could have impacted their response. All measures were taken to safeguard the personal information collected during the study.

Instrument of the study

The study used two validated self-administered questionnaires in the local language. The original questionnaire was designed to minimize cultural biases that could affect disclosure and this ensured consistency making it suitable for use in Saudi Arabia. This questionnaire, however, was tested among peers and experts to ensure content validity.

Domestic violence questionnaire

The first, a self-administer survey to report DV, was developed from the original WHO multi-country Study on Women’s Health and DV against Women in Bangladesh, Brazil, Peru, Thailand, and the United Republic of Tanzania [15]. The survey was a 29-item questionnaire to determine DV with subscales measuring physical violence (8 items), sexual violence (2 items), psychological/ emotional abuse (11 items), and intimate partner controlling behavior (8 items). Each question was scored on a linear scale from 0 to 5 (0: never, 1: rarely, 2: sometimes, 3: often, 4: very often, and 5: every day).

Childhood trauma questionnaire

The second questionnaire was administered to the same participants to determine if they had any CT in their early life that included multiple types of abuse and neglect. This validated childhood trauma short-form questionnaire was a 28-item questionnaire with five dimensions: emotional abuse (5 items), physical abuse (5 items), sexual abuse (5 items), emotional neglect (5 items), and physical neglect (8 items) [16]. This short form was originally developed from a 70-item Childhood Trauma Questionnaire [17]. Each item in the present questionnaire was scored from 1 to 5 based on how accurately participants perceived the statement (1: never true, 2: rarely true, 3: sometimes true, 4: often true, and 5: very often true). Ten items (5 emotional neglect and 5 physical neglect) were reverse scored.

The cut-off point for measuring the prevalence rate of DV and CT and their subscales was determined based on respondents’ self-reported experiences. Prevalence rates were calculated by identifying individuals who reported experiencing at least one instance of a specific subscale, such as physical, sexual, or psychological violence for DV, and emotional, physical, or sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect for CT. For both DV and CT, any reported experience, regardless of frequency, was considered a positive instance, establishing the prevalence rate.

In both questionnaires, the cumulative mean score was determined to measure DV and the extent of childhood trauma, respectively; the higher the mean score, the higher the extent of DV and CT experience. Preceding the two questionnaires were nine demographic questions to determine the respondent’s age, years of marriage, number of kids, employment, income, height, and weight. The participants’ body mass index (BMI) was calculated from the reported height and weight.

The validation process involved translation and back-translation of the questionnaires to ensure linguistic and cultural appropriateness. Cultural experts reviewed the content, and a small pilot test with 25 respondents was conducted to provide clarity. A reliability test for the questionnaires was carried out using a sample of 25 respondents (not included in the final survey). Cronbach’s alpha calculated the tool’s internal consistency of the used subscales: Physical Violence (α = 0.75), Sexual violence (α = 0.93, Psychological violence (α = 0.78), and controlling behavior (α = 0.78).

Parametric Estimation of neural network model by MLP (Multilayer perceptron model)

The Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) is a powerful class of artificial neural networks designed to model complex relationships within data. It consists of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer, each interconnected by weighted neurons. The network has one hidden layer with 2 units. The network typically includes:

Input Layer: Receives the initial data.

Hidden Layers: Transform the input data through weighted connections and activation functions.

Output Layer: Produces the final prediction or classification.

MLP is a non-linear activation function, enabling it to capture patterns and interactions across variables.

Statistical analysis

The reliability of the questionnaire was evaluated by employing Cronbach’s alpha, a statistical measure that assesses the internal consistency of the instrument. The normality of the data was assessed by conducting the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk test. The results of both the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests indicated that all the continuous variables (Age, Years of Marriage, number of kids, income, etc.) significantly deviate from a normal distribution, as their p-values are less than 0.05. Descriptive statistics like median with IQR and percentages of responses, were used to describe the demographic and qualitative variables of the study. The strength of the relationship between the variables was assessed by Spearman’s rank correlation and presented by HEATMAP. The study employed the χ2-test of independence to examine the relationship and association between domestic violence, childhood trauma, and demographic variables. The machine learning model and multilayer perceptron approach were employed to measure the importance of predictors in Estimating DV and CT. The results will be declared statistically significant if p < 0.05. All the analyses were performed in SPSS version 28.

Results

A total of 503 married women responded to the questionnaires, and most (196, 39%) were between 26 and 33 years of age with a median age of 28 (IQR 25–35). The median years of marriage was 7 years (IQR 4–13), and the number of kids was two kids (IQR 1–3). While more than half of the respondents had a Bachelor’s degree, 58% (293) were unemployed. The median income of the respondents was 5000 Saudi Riyals (SAR), and the median income was 8000 (IQR 8000–14000) SAR. Though it was positive to see most (187, 37.2%) of our respondents were healthy, 22.9% (115) were obese [Table 1].

Table 1.

Socio-demographic factors and their frequencies (N = 503)

| Socio-demographic variables | Category | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18–25 | 161 (32) | |

| 26–33 | 196 (39) | ||

| 34–41 | 89 (17.7) | ||

| 42–49 | 29 (5.8) | ||

| 50–57 | 16 (3.2) | ||

| 58–65 | 6 (1.2) | ||

| Missing | 6 (1.2) | ||

| Education | High school | 153 (30.4) | |

| Bachelors | 329 (65.4) | ||

| Higher | 16 (3.2) | ||

| Missing | 5 (1) | ||

| Employment | Yes | 184 (36.6) | |

| No | 293 (58.3) | ||

| Total | 477 (94.8) | ||

| Missing | 26 (5.2) | ||

| BMI | Underweight | 23 (4.6) | |

| Healthy | 187 (37.2) | ||

| Overweight | 118 (23.5) | ||

| Obese | 115 (22.9) | ||

| Missing | 60 (11.9) | ||

| Socio-demographic variables | Minimum | Maximum | Median (IQR) |

| Age (years) | 18.00 | 66.00 | 28.00 (25–35) |

| Years of marriage | 0.50 | 60.00 | 7.00 (4–13) |

| Number of kids | 0.00 | 12.00 | 2.00 (1–3) |

| Income | 0.00 | 26000.00 | 2000.00 (0–5000) |

| income of the family | 0.00 | 250000.00 | 8000.00 (8000–14000) |

| BMI | 15.23 | 515.70 | 25.32 (22.14–30.11) |

The study found that most participants did not report experiences of DV and CT, as shown in Tables 2 and 3. Physical violence was the least reported, with 91.3% (459) of respondents stating they had never experienced such incidents. Similarly, 93.2% (469) reported never facing controlling behaviors, such as being restricted from accessing healthcare. Psychological violence was less frequent, with 343(68.2%) denying exposure to demeaning remarks about their self-worth. Regarding childhood trauma, 316 (62.8%) reported no emotional abuse, while 473(94%) denied experiencing physical neglect, particularly food deprivation. However, emotional neglect showed a different trend, with 210(41.7%) indicating inconsistent feelings of being cared for during childhood. Access to medical care was overwhelmingly confirmed, with 252(99.2%) stating they received medical attention when needed. Reports of sexual abuse were rare, with 453(90.1%) denying any such experiences.

Table 2.

Frequency of experiences of physical, sexual, psychological, and controlling violence

| Physical violence | Frequency n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statements | Never happened | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Very often | Every day |

| He slapped me | 459(91.3) | 17(3.4) | 13(2.6) | 8(1.6) | 3(0.6) | 2(0.4) |

| He put me down. | 475(94.4) | 9(1.8) | 11(2.2) | 5(1.0) | 3(0.6) | 0(0) |

| He shook me violently. | 456(90.7) | 19(3.8) | 16(3.2) | 6(1.2) | 3(0.6) | 2(0.4) |

| He pushed me and grabbed me tightly. | 459 (91.3) | 20 (4.0) | 11 (2.2) | 7 (1.4) | 4 (0.8) | 2 (0.4) |

| Use a knife, pistol, or other weapon | 483 (96.0) | 9 (1.8) | 4 (0.8) | 4 (0.8) | 2(0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| He hit me or tried to hit me with something. | 462 (91.8) | 18 (3.6) | 17 (3.4) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.6) | 2 (0.4) |

| He kicked me, bit me, or hit me with his fist. | 467 (92.8) | 14 (2.8) | 12 (2.4) | 6 (1.2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) |

| Heaped on me beating | 469 (93.2) | 18 (3.6) | 11 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2(0.4) | 2 (0.4) |

| Sexual violence | Frequency (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statements | Never happened | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Very often | Every day |

| He raped me. | 484 (96.2) | 5 (1.0) | 5 (1.0) | 7 (1.4) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

| He tried to rape me. | 481(95.6) | 10 (2.0) | 7 (1.4) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Psychological violence | Frequency (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statements | Never happened | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Very often | Every day |

| He told me I wasn’t good enough. | 343 (68.2) | 70 (13.9) | 60 (11.9) | 18 (3.6) | 7(1.4) | 5(1.0) |

| Lock me in the bedroom | 476 (94.6) | 9 (1.8) | 8 (1.6) | 9(1.8) | 1(0.2) | 0(0) |

| He said I was ugly. | 456 (90.7) | 18 (3.6) | 20 (4.0) | 7(1.4) | 1(0.2) | 1(0.2) |

| He blames me for being the cause of his violent behaviour. | 450 (89.5) | 21(4.2) | 14 (2.8) | 9(1.8) | 5(1.0) | 4(0.8) |

| He threatened me during a phone call. | 465 (92.4) | 15(3.0) | 11 (2.2) | 5(1.0) | 3(0.6) | 3(0.6) |

| He threatened me during my work time. | 479 (95.2) | 8 (1.6) | 7 (1.4) | 4(0.8) | 1(0.2) | 3(0.6) |

| He said I was crazy. | 446(88.7) | 27(5.4) | 18(3.6) | 7(1.4) | 1(0.2) | 2(0.4) |

| He told me no one would accept you | 457(90.9) | 13(2.6) | 18(3.6) | 5(1.0) | 6(1.2) | 4(0.8) |

| He took my wallet and left me with nothing. | 475(94.4) | 15(3.0) | 7(1.4) | 2(0.4) | 1(0.2) | 3(0.6) |

| Try to convince my friends, family, or kids that I’m crazy. | 476(94.6) | 14(2.8) | 8(1.6) | 3(0.6) | 1(0.2) | 1(0.2) |

| He told me I was stupid. | 441(87.7) | 21(4.2) | 23(4.6) | 9(1.8) | 2(0.4) | 7(1.4) |

| Controlling behavior | Frequency (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statements | Never happened | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Very often | Every day |

| He prevented me from seeking healthcare | 469 (93.2) | 15 (3.0) | 13 (2.6) | 4 (0.8) | 2(0.4) | 0 (0) |

| Follow me | 466 (92.6) | 11 (2.2) | 10 (2.0) | 14 (2.8) | 0(0) | 2 (0.4) |

| He tried to turn my family, friends, and children against me. | 456 (90.7) | 16 (3.2) | 20 (4.0) | 10 (2.0) | 0(0) | 0 (0) |

| Try to prevent me from seeing my family or talking to them. | 460 (91.5) | 19 (3.8) | 12 (2.4) | 8 (1.6) | 2(0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Voyeurs around my house | 479 (95.2) | 5 (1.0) | 11 (2.2) | 6 (1.2) | 2(0.4) | 0 (0) |

| He doesn’t want me to meet my friends. | 437 (86.9) | 28 (5.6) | 20 (4.0) | 8 (1.6) | 5(1.0) | 5 (1.0) |

| He refused to work outside the home. | 452 (89.9) | 19 (3.8) | 17 (3.4) | 5 (1.0) | 5(1.0) | 5 (1.0) |

| He gets upset if dinner is not prepared or the housework is done as it should | 417 (82.9) | 27 (5.4) | 25 (5.0) | 16 (3.2) | 7(1.4) | 10 (2.0) |

Table 3.

Frequency of emotional, physical, sexual abuse, and neglect subscales (CT)

| Emotional abuse | Frequency (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statements | Not true at all | True rarely | True sometimes | True, mostly | Probably true |

| In my childhood, some members of my family used to call me obscene nicknames regularly. | 316 (62.8) | 87 (17.3) | 62 (12.3) | 21 (4.2) | 16 (3.2) |

| As a child, I felt that my father wished that I was not born | 433 (86.1) | 27 (5.4) | 16 (3.2) | 11 (2.2) | 12 (2.4) |

| As a child, I felt like someone in my family hated me. | 408 (81.1) | 34 (6.8) | 33 (6.6) | 14 (2.8) | 13 (2.6) |

| In my childhood, my family members used to say painful and insulting words to me. | 387 (76.9) | 54 (10.7) | 36 (7.2) | 14 (2.8) | 11 (2.2) |

| In my childhood, I was emotionally abused | 407 (80.9) | 36 (7.2) | 24 (4.8) | 13 (2.6) | 21 (4.2) |

| Physical abuse | Frequency (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statements | Not true at all | True rarely | True sometimes | True, mostly | Probably true |

| As a child, I was severely beaten by a member of my family, after which I protested for medical attention. | 447 (88.9) | 22 (4.4) | 13 (2.6) | 9 (1.8) | 12 (2.4) |

| In my childhood, some members of my family beat me severely, which left marks and bruises on my body. | 433 (86.1) | 31 (6.2) | 15 (3.0) | 13 (2.6) | 10 (2.0) |

| In my childhood, I was punished by tying me with a board or a rope or any other hard thing | 463 (92.0) | 12 (2.4) | 13 (2.6) | 5 (1.0) | 10 (2.0) |

| In my childhood, I was physically abused | 422 (83.9) | 25 (5.0) | 17 (3.4) | 16 (3.2) | 21 (4.2) |

| In my childhood, I was badly beaten and noticed by a teacher, neighbor, or doctor. | 444 (88.3) | 21 (4.2) | 15 (3.0) | 5 (1.0) | 17 (3.4) |

| Sexual abuse | Frequency (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statements | Not true at all | True rarely | True sometimes | True, mostly | Probably true |

| Someone tried to touch me sexually and/or made me touch them. | 430 (85.5) | 33 (6.6) | 12 (2.4) | 15 (3.0) | 13 (2.6) |

| Someone threatened to hurt me unless I did something sexual with them. | 425 (84.5) | 43 (8.5) | 7 (1.4) | 19 (3.8) | 9 (1.8) |

| Someone tried to make me do and/or watch sexual things. | 442 (87.9) | 23 (4.6) | 17 (3.4) | 8 (1.6) | 12 (2.4) |

| Someone molested me | 449 (89.3) | 21 (4.2) | 12 (2.4) | 10 (2.0) | 10 (2.0) |

| I think I was sexually abused. | 453 (90.1) | 16 (3.2) | 15 (3.0) | 9 (1.8) | 7 (1.4) |

| Emotional neglect | Frequency (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statements | Not true at all | True rarely | True sometimes | True, mostly | Probably true |

| In my childhood, there was a member of my family who made me feel important or special. | 63 (12.5) | 65 (12.9) | 73 (14.5) | 134 (26.6) | 165 (32.8) |

| In my childhood, I felt loved. | 53 (10.5) | 38 (7.6) | 56 (11.1) | 145 (28.8) | 210 (41.7) |

| In my childhood, my family looked out for each other. | 56 (11.1) | 39 (7.8) | 56 (11.1) | 142 (28.2) | 205 (40.8) |

| In my childhood, my family members were very close to each other. | 69 (13.7) | 41 (8.2) | 53 (10.5) | 152 (30.2) | 186 (37) |

| In my childhood, there was someone who took me to the doctor when I needed him. | 65 (12.9) | 23 (4.6) | 36 (7.2) | 123 (50.1) | 252 (99.2) |

| Physical neglect | Frequency (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statements | Not true at all | True rarely | True sometimes | True, mostly | Probably true |

| As a child, I was subjected to deprivation including food deprivation. | 473 (94) | 12 (2.4) | 12 (2.4) | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) |

| In my childhood, there was someone to take care of me | 49 (9.7) | 34 (6.8) | 44 (8.7) | 145 (28.8) | 231 (45.9) |

| In my childhood, my parents were so careless with us that they couldn’t take care of the family | 399 (79.3) | 50 (9.9) | 22 (4.4) | 15 (3.0) | 17 (3.4) |

| When I was a child, I could only find worn clothes to wear. | 436 (86.7) | 29 (5.8) | 10 (2.0) | 16 (3.2) | 10 (2.0) |

| In my childhood, someone would take me to the doctor when I needed | 71 (14.1) | 17 (3.4) | 40 (8.0) | 109 (21.7) | 262 (52.7) |

| In my childhood, I never wished to have been born to other parents | 242 (48.1) | 28 (5.6) | 27 (5.4) | 64 (12.7) | 140 (27.8 |

| In my childhood, I had the perfect childhood | 44 (8.7) | 40 (8.0) | 63 (12.5) | 160 (31.6) | 194 (38.6) |

| In my childhood, I felt my family was one of the best families. | 57 (11.3) | 43 (8.5) | 68 (13.5) | 127 (25.2) | 206 (41.0) |

The study’s findings on childhood trauma highlighted various experiences among the respondents. Regarding emotional abuse, 316(62.8%) stated that they had never been subjected to derogatory name-calling, while 433(86.1%) denied ever feeling unwanted by their father. Physical abuse was also infrequent, with 447(88.9%) reporting that they had never been severely beaten. In terms of emotional neglect, 210 (41.7%) indicated that they felt loved during childhood, and 262(52.7%) confirmed that they received medical attention when needed, suggesting a relatively stable level of care. Reports of sexual abuse were rare, with 90.1% (453) denying any such experiences. [Table 3].

The study observed significant correlations between DV, CT, demographics, and BMI. Physical violence in DV exhibited a significant negative correlation with age ( -0.093,

-0.093,  = 0.039), suggesting that older individuals may experience less physical violence compared to younger individuals. This finding could be attributed to differences in life stages, relationship dynamics, or evolving patterns of DV across age groups. Moreover, physical violence showed a positive correlation with weight (

= 0.039), suggesting that older individuals may experience less physical violence compared to younger individuals. This finding could be attributed to differences in life stages, relationship dynamics, or evolving patterns of DV across age groups. Moreover, physical violence showed a positive correlation with weight ( = 0.252,

= 0.252,  = 0.000), showing that participants who experience physical violence may also face higher BMI, potentially due to stress-related eating habits or a more sedentary lifestyle linked to trauma. CT displayed significant relationships with various forms of DV. Emotional abuse in childhood was positively correlated with physical violence in adulthood (

= 0.000), showing that participants who experience physical violence may also face higher BMI, potentially due to stress-related eating habits or a more sedentary lifestyle linked to trauma. CT displayed significant relationships with various forms of DV. Emotional abuse in childhood was positively correlated with physical violence in adulthood ( = 0.093, p = 0.038), while physical abuse in childhood showed a significant positive correlation with psychological violence (

= 0.093, p = 0.038), while physical abuse in childhood showed a significant positive correlation with psychological violence ( 0.109,

0.109, ) and sexual violence (

) and sexual violence ( 0.103,

0.103,  0.046) in adulthood. Additionally, BMI was found to have significant associations with both CT and DV. Weight was positively correlated with sexual violence (

0.046) in adulthood. Additionally, BMI was found to have significant associations with both CT and DV. Weight was positively correlated with sexual violence ( = 0.186, p = 0.000) and psychological violence (

= 0.186, p = 0.000) and psychological violence ( ,

,  0.000), indicating that participants with higher BMI may be more likely to experience these forms of abuse. This may reflect the psychological impact of trauma, such as poor body image or depression, which can lead to weight gain or other health-related behaviors. The study revealed that BMI was negatively correlated with emotional neglect in childhood (

0.000), indicating that participants with higher BMI may be more likely to experience these forms of abuse. This may reflect the psychological impact of trauma, such as poor body image or depression, which can lead to weight gain or other health-related behaviors. The study revealed that BMI was negatively correlated with emotional neglect in childhood ( = -0.249

= -0.249  = 0.000), depicting that participants who experienced higher levels of emotional neglect may struggle with weight management due to unhealthy coping mechanisms. Controlling behavior in relationships also showed significant correlations with CT. It was also concluded in the study that controlling behavior in adult relationships was positively correlated with emotional abuse in childhood (

= 0.000), depicting that participants who experienced higher levels of emotional neglect may struggle with weight management due to unhealthy coping mechanisms. Controlling behavior in relationships also showed significant correlations with CT. It was also concluded in the study that controlling behavior in adult relationships was positively correlated with emotional abuse in childhood ( = 0.140,

= 0.140,  = 0.002) and sexual abuse (

= 0.002) and sexual abuse ( = 0.152,

= 0.152, ). [Figure 1]

). [Figure 1]

Fig. 1.

Heat map of DV and CT with clinical and demographic factors

However, even with rare incidences of DV and CT, the prevalence of DV among the respondents was 4.86%, with controlling behavior of the intimate partner (6.09%) and psychological violence most commonly reported. The incidences of CT experienced by these women were 16.20%, most of which came from emotional neglect (31.44) (see Table 4). The median score of DV was 1.99 (0.81), and that of CT was 2.15(0.45). Among the DV subscales, the median score of psychological violence (2.00, IQR = 0.50) and controlling behavior (2.25 with IQR 0.50) was higher compared to physical and sexual violence, whereas the emotional neglect subscale mean score was the highest among the CT subscales, 2.50 (0.50) [Table 4]. It was found that while DV was significantly associated with BMI ( < 0.001) and negatively correlated with income of the women [

< 0.001) and negatively correlated with income of the women [ = 0.042,

= 0.042,  -0.118), CT was significantly associated with BMI (

-0.118), CT was significantly associated with BMI ( = < 0.001) and education (

= < 0.001) and education ( < 0.001) of the women; women with higher education reported more CT (mean score = 1.93 ± 0.61) [Table 5]. Overall, a significant correlation existed between CTs and experiencing DV in adult life [Table 6].

< 0.001) of the women; women with higher education reported more CT (mean score = 1.93 ± 0.61) [Table 5]. Overall, a significant correlation existed between CTs and experiencing DV in adult life [Table 6].

Table 4.

Median scores of the DV and CT subscales with prevalence

| Factors | Subscales | Prevalence (%) | Median (IQR) | Overall Median (IQR) |

Overall prevalence (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV | Physical violence | 2.13 | behavior | 1.99 (0.81) | 4.86 | < 0.001 (0.358)*** |

| Sexual violence | 2.39 |

1.98 (2.00) |

||||

| Psychological violence | 6.04 |

2.00 (0.27) |

||||

| Controlling behaviour | 6.09 |

2.25 (0.50) |

||||

| CT | Emotional abuse | 22.15 | 1.25 (0.50) | 2.15 (0.45) | 16.20 | |

| Physical abuse | 12.03 | 2.15 (0.50) | ||||

| Sexual abuse | 12.39 | 2.20 (0.25) | ||||

| Emotional neglect | 31.44* | 2.50 (0.50) | ||||

| Physical neglect | 16.50** | 1.50 (0.50) |

Prevalence(%)=(Total number of individuals in the study/ Number of individuals with the condition)×100

IQR = Inter-quartile Range

*All the items of the subscale were reverse-scored

** Some of the items of the subscale were reverse-scored

*** Correlation is significant at α = 0.01

Table 5.

Mean scores and association of socio-demographic factors with DV and CT

| Socio-demographic variables | Category | DV Mean score (± SD) |

CT Mean score (± SD) |

DV χ2– statistic (p-value) |

CT χ2– statistic (p-value) |

Effect Size (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–25 | 0.17 (0.41) | 1.58 (0.51) |

0.57 (0.829) |

1.05 (0.522) |

< 0.1 |

| 26–33 | 0.17 (0.48) | 1.64 (0.48) | ||||

| 34–41 | 0.21 (0.53) | 1.61 (0.46) | ||||

| 42–49 | 0.23 (0.40) | 1.58 (0.48) | ||||

| 50–57 | 0.17 (0.38) | 1.55 (0.46) | ||||

| 58–65 | 0.09 (0.15) | 1.84 (0.53) | ||||

| Education | High school | 0.261 (0.52) | 1.74 (0.53) |

3.07 (0.260) |

< 0.001*** | 0.311 |

| Bachelors | 0.136 (0.40) | 1.51 (0.43) | ||||

| Higher | 0.280 (0.66) | 1.93 (0.61) | ||||

| Employment | Yes | 0.15 (0.50) | 1.60 (0.45) |

4.26 (0.108) |

1.36 (0.508) |

< 0.1 |

| No | 0.17 (0.38) | 1.59 (0.49) | ||||

| BMI | Underweight | 0.13 (0.23) | 1.58 (0.51) | < 0.001 | < 0.001*** | 0496 |

| Healthy | 0.12 (0.33) | 1.54 (0.47) | ||||

| Overweight | 0.12 (0.42) | 1.51 (0.40) | ||||

| Obese | 0.39 (0.66) | 1.79 (0.52) | ||||

| Years of marriage | 0.177 (0.44) | 1.59 (0.47) |

0.83 (0.612) |

5.28 (0.211) |

< 0.1 | |

| Number of kids | 0.199 (0.46) | 1.61 (0.47) |

0.18 (0.956) |

5.28 (0.211) |

< 0.1 | |

| Income | 0.231 (0.53) | 1.66 (0.50) |

9.34 (0.042 ) |

3.17 (0.355) |

0.118 | |

| The income of the family | 0.230 (0.52) | 1.65 (0.50) |

5.54 (0.162) |

5.36 (0.177) |

< 0.1 | |

*** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Association has been calculated by χ2-test of association and effect size (d) has been computed by Cramer’s V Formula

Small effect: Cramer’s V between 0.1 and 0.3

Medium effect: Cramer’s V between 0.3 and 0.5

Large effect: Cramer’s V above 0.5

Table 6.

Normalized importance of predictors in estimating DV and CT

| Independent Variable Importance | Importance | Normalized Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Violence (DV) | 0.165 | 100.0% |

| Sexual Violence (DV) | 0.133 | 81.0% |

| Psychological violence (DV) | 0.125 | 76.1% |

| Controlling behavior of partner(DV) | 0.102 | 62.1% |

| Emotional Abuse (CT) | 0.113 | 68.4% |

| Physical Abuse (CT) | 0.099 | 60.5% |

| Sexual Abuse (CT) | 0.053 | 32.4% |

| Emotional neglect (CT) | 0.078 | 47.5% |

| Physical neglect (CT) | 0.132 | 80.0% |

1. Normalized importance has been calculated for every predictor with one 1 hidden layer which includes 2 units using a hyperbolic tangent activation function. Softmax has been used as an activation function for the output layer while cross-entropy has been computed for error-function

The study found that age did not significantly influence domestic violence (DV) or childhood trauma (CT), with effect sizes close to zero, indicating no meaningful relationship. However, education was significantly associated with CT (p < 0.001), with higher education levels corresponding to higher CT scores, showing a small to moderate effect size (V = 0.19). No significant relationship was found between education and DV. Body mass index (BMI) was strongly associated with both DV and CT (p < 0.001 for both), with effect sizes suggesting moderate to large associations (V = 0.25 for DV and 0.27 for CT). Specifically, individuals classified as obese reported higher experiences of both DV and CT, indicating a vulnerability that requires further investigation. Income showed a significant negative correlation with DV (r = -0.118, p = 0.042), suggesting that individuals with lower income may be more susceptible to DV, though the small effect size indicates a weak relationship. No significant correlation was found between income and CT. Other socio-demographic variables, including employment, years of marriage, number of children, and family income, did not show significant relationships with either DV or CT.[Table 5].

In our MLP model, Out of a total of 504 cases, 412 (81.7%) were deemed valid and included in the analysis, while 92 cases (18.3%) were excluded due to potential issues such as missing values or outliers. The valid data was split into two subsets: a training set comprising 288 cases (69.9%) and a testing set consisting of 124 cases (30.1%). The training set was utilized to train the MLP model, enabling it to learn patterns and relationships between input variables and the target outcome. The hyperbolic tangent activation function in the output layer is a mathematical function that maps input values to a range between − 1 and 1. Mathematically it can be expressed as;

|

2 |

Where:

is the input to the activation function.

is the input to the activation function. is the exponential function.

is the exponential function.

This makes it particularly useful for modeling non-linear relationships and enabling the network to learn complex patterns. The input layer consists of 9 factors (such as physical, sexual, and emotional abuse) with 173 units. There’s one hidden layer with 2 units using the hyperbolic tangent activation function.

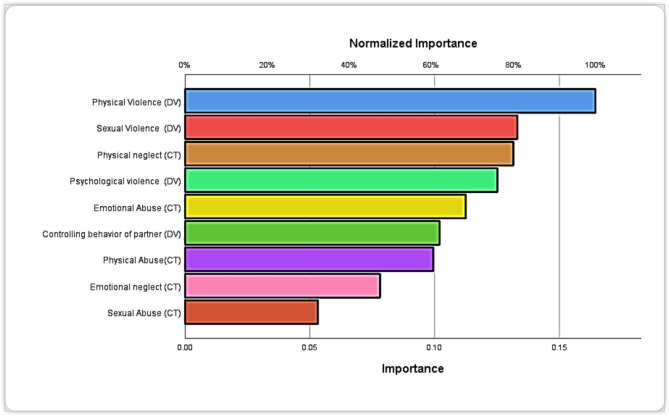

The neural network model utilizes the normalized importance of various predictors to estimate the likelihood of experiencing domestic violence (DV) and childhood trauma (CT). The independent variable importance analysis revealed the relative contributions of predictors to the multilayer perceptron (MLP) model, with Physical Violence (DV) emerging as the most influential factor, exhibiting a normalized importance of 100%. Other significant contributors included Sexual Violence (DV) and Physical Neglect (CT), with normalized importance of 81.0% and 80.0%, respectively. Psychological Violence (DV) and Emotional Abuse (CT) also played substantial roles, with normalized importance of 76.1% and 68.4%. In contrast, Sexual Abuse (CT) had the least impact, contributing only 32.4%. These findings highlight that Physical Violence is the most significant predictor of DV, while Physical Neglect is the most influential predictor of CT[Figure 2].

Fig. 2.

Percentage normalized importance of predictors associated with DV and CT

Discussion

The present study studied the prevalence and factors associated with (DV) and CT among married women in the Al Hasa region, Saudi Arabia which provides a detailed analysis within the context of Saudi society and culture. The study’s results hold implications for understanding the socio-demographic and psychological factors associated with and influencing DV and CT, and their implications for women’s health and empowerment in this rapid cultural change. Saudi Arabia is undergoing transformative changes under Vision 2030, including significant women empowerment advancements. The Saudi government has implemented initiatives to promote equality, establishing women’s rights in education, social support, health, and justice sectors, along with their involvement in business and politics [18]. This environment makes it important to reconsider the prevalence and dynamics of DV and CT, key issues that can influence women’s well-being. The present study reported a lower prevalence of DV (4.66%) as compared to previous studies from Saudi Arabia. For example, DV prevalence was reported at 20% in the Riyadh region [19], 30% in the Aljouf region [20], 33.24% in the Western region [21], and 32% among 13 governorates of Saudi Arabia [22]. The results of our study align with these studies regarding the dominance of psychological violence and controlling behavior over physical and sexual violence [9, 21]. However, the overall prevalence of DV in our study was significantly lower, suggesting that cultural shifts and legal protections may have contributed to these differences [25].

The present study reported CT more frequently (18.90%) than DV, with emotional neglect being the most common form (31.44%). This finding aligns with a meta-analysis reporting a 15% prevalence of childhood abuse in Saudi Arabia [23]. Unlike some studies that emphasize physical abuse as the most common form, our study highlights emotional neglect, which may be culturally rooted in authoritarian parenting styles [23, 24]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identifies several risk factors linked to intimate partner violence (IPV), including individual, relationship, community, and societal factors [26]. Our study revealed that individual factors such as income, education, employment, and a history of childhood abuse are significantly associated with both domestic violence (DV) and childhood trauma. Notably, income emerged as a protective factor, with higher income correlating with a lower prevalence of DV. These findings support the hypothesis that domestic violence and the controlling behavior of an intimate partner are closely linked, influencing the overall prevalence of DV. It has been observed in previous studies that when a woman earns more than her male partner, domestic violence is more likely to occur by 35% [27]. Studies, including one from Australia, show that women earning more than their male partners are at an increased risk of IPV, as this disrupts traditional gender roles, creating feelings of insecurity in male partners [28–32]. This aligns with global findings that suggest economic shifts contribute to IPV, and although our study shows a weak correlation between income and DV, cultural and societal factors might explain this in the Al-Hasa region.

Older respondents in our study reported higher levels of CT compared to younger participants, aligning with the notion that cultural practices around parenting are shifting towards more nurturing approaches over time. Significant correlations were observed in the study. Physical violence exhibited a negative correlation with age, suggesting that older women experience less physical violence, which is consistent with findings from other studies showing that life stages and relationship dynamics can influence DV patterns [39]. Conversely, physical violence showed a positive correlation with BMI, indicating that women experiencing physical violence may face higher BMI levels, possibly due to stress-induced behaviors such as emotional eating or sedentary lifestyles. These findings align with studies that highlight the role of chronic stress in contributing to obesity [42].

Emotional abuse in childhood was positively associated with physical violence in adulthood, echoing findings from global literature that highlight the cyclical nature of abuse [45]. Our study found a significant association between education and childhood trauma, with women holding higher degrees reporting greater levels of trauma. This observation aligns with studies that discuss the psychological challenges and societal pressures faced by women pursuing advanced education [36, 37]. Conversely, other research links childhood trauma to lower educational level, suggesting that the flexibility observed in our participants may be influenced by cultural or socio-economic factors unique to this context [38]. Additionally, higher-educated women in our study reported slightly higher rates of domestic violence, which aligns with research suggesting that shifts in traditional gender roles may contribute to relationship conflict [38]. These findings are consistent with prior studies that indicated higher-educated women reported more childhood trauma compared to those with only a Bachelor’s degree. In Saudi Arabia, the gender disparity in educational attainment is notable, with more women (58.1%) graduating with a Bachelor’s degree compared to men (41.9%), while this ratio reverses for Master’s (female: 48.1%, male: 51.9%) and Ph.D. degrees (female: 23.6%, male: 76.4%) [35]. These findings also support the study hypothesis stated that DV and childhood trauma are significantly associated with clinical, emotional, and demographic factors.

The relationship between employment and DV was similarly observed in our study, showing an inverse relationship, though not statistically significant. Women who had experienced childhood trauma were more likely to be employed, supporting post-traumatic growth theories, which suggest that overcoming trauma may contribute to resilience and greater economic participation [33, 34]. This addresses the hypothesis regarding the role of demographic factors such as employment in DV and childhood trauma. Additionally, physical health and BMI emerged as significant factors associated with both DV and childhood trauma. Although the study could not conclusively determine whether obesity was a result of DV or CT, previous research suggests that women exposed to IPV are more likely to report obesity [40]. Our findings reinforced this, with a strong association found between BMI and both DV and CT. Obese women in our study reported higher experiences of abuse, which is consistent with research linking trauma-induced stress to cortisol dysregulation, leading to weight gain [41, 42]. This finding directly supports the hypothesis exploring the significant associations between DV, childhood trauma, and clinical factors such as BMI. Depressive symptoms were found to mediate the relationship between IPV, childhood trauma, and obesity, a result consistent with studies from Riyadh [43] which supports the study hypothesis that DV and childhood trauma are significantly associated with clinical, emotional, and demographic factors.

Our present study revealed a positive correlation between childhood trauma and DV. Women who experienced emotional neglect or abuse during childhood were more likely to report controlling behaviors and psychological violence in their relationships. This finding aligns with global studies that highlight the intergenerational transmission of abuse [44–46]. For instance, the UK census study reported that over half of individuals with childhood maltreatment histories also experienced DV later in life [44].

Implication of the study

The implications of the study recommended that addressing DV and CT needs a multidimensional approach that should consider both psychological and socio-demographic features. The results highlighted the need for targeted intermediations that focus on breaking the cycle of generational abuse, mainly by offering support to women who have experienced emotional neglect or abuse in childhood. The study indicated that growing women’s economic freedom and right to access education can reduce their vulnerability to DV, which emphasizes the importance of Vision 2030 initiatives aimed at empowering women in Saudi Arabia.

Possible limitations of the study

The present study investigated the factors through a validated questionnaire which could only quantitatively measure their experiences; however, such emotionally charged and challenging topics need more insights that can only be presented through qualitative studies of the victims. The study used a convenience sampling method, by the results cannot be generalized which can be covered by further studies. The lower prevalence of domestic violence (DV) could be influenced by underreporting due to social desirability bias rather than actual societal progress. It is suggested that have detailed survey study including psychological and social complexities of victims facing DV and who also suffered from childhood abuse be conducted to draw affirmative conclusions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study emphasized the significant association between DV and CT among married women in the Al-Hasa region, KSA. Despite a lower prevalence of DV compared to previous studies, psychological violence and controlling behavior remain serious concerns, signifying that cultural shifts and legal protections may play an important role in mitigating physical abuse. The outcomes of the study also revealed that higher education and BMI are associated with increased reports of both DV and CT, pointing to the evolving gender dynamics and the physical health consequences of trauma.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the respondents who participated in the study for their cooperation.

Abbreviations

- ACEs

Adverse childhood experiences

- BMI

Body mass index

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CT

Childhood Trauma

- DV

Domestic Violence

- IPV

Intimate partner violence

- IQR

Inter-Quartile Range

- MLP

Multilayer Perceptron

- PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Author contributions

Conceptualization: AAM, AG, CS; Methodology: AAM, CS, MD; Software: CS, HA, MD, AE; Validation: AAM, CS; Formal analysis: AAM, CS, MD, HS; Investigation: AAM, CS, LA, NA, HB; Data curation: AAM, CS, AE; Writing—original and revised draft: AAM, CS, HA, HS, AG, MD, NA, AE; Supervision: AAM, CS; Project administration: AAM; Funding acquisition: None. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There is no funding for this study.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The present study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and informed consent was obtained from each individual participating in the study on an electronic consent form. Ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB), Almoosa Specialist Hospital was obtained before initiating the data collection (IRB log number: ARC-22.04.07).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Anderson KL. Gender, status, and domestic violence: an integration of feminist and family violence approaches, domestic violence. Routledge; 2017. pp. 263–77.

- 2.Hines D. Overlooked victims of domestic violence: men. Int J Family Res Policy. 2015;1(1).

- 3.Perryman SM, Appleton J. Male victims of domestic abuse: implications for health visiting practice. J Res Nurs. 2016;21(5–6):386–414. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott-Storey K, O’Donnell S, Ford-Gilboe M, Varcoe C, Wathen N, Malcolm J, et al. What about the men? A critical review of Men’s experiences of intimate partner violence. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2023;24(2):858–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sardinha L, Maheu-Giroux M, Stöckl H, Meyer SR, García-Moreno C. Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. Lancet. 2022;399(10327):803–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations. (n.d.). What is domestic abuse? United Nations, United Nations.; Retrieved 30 July 2023, from https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/what-is-domestic-abuse

- 7.Afifi Z, Al-Muhaideb NS, Hadish NF, Ismail FI, Al-Qeamy FM. Domestic violence and its impact on married women’s health in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2011;32(6):612–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tashkandi A, Rasheed P. Wife abuse: a hidden problem: a study among Saudi women attending PHC centres. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15(5). [PubMed]

- 9.Alquaiz AM, Almuneef M, Kazi A, Almeneessier A. Social determinants of domestic violence among Saudi married women in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36(3–4):NP1561–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alkhattabi F, Al Faryan N, Alsaleh M, Long M, Alkhani A, Alwahibah S, et al. Understanding the epidemiology and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on domestic violence and child abuse in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2022;9(4):209–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Embassy of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. (2019, August). Saudi Arabia’s reforms and programs to empower women. https://www.saudiembassy.net/sites/default/files/Factsheet on Progress for Women in Saudi Arabia.pdf

- 12.Gmi B. Saudi Arabia social media statistics 2020 (Infographics)-GMI blog. Global Media Insight. 2023.

- 13.Shields M, Tonmyr L, Hovdestad WE, Gonzalez A, MacMillan H. Exposure to family violence from childhood to adulthood. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Putting women’s safety first: ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. Geneva: WHO; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.García-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts C. WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Geneva: World health organization. 2005;204(1):18.

- 16.Emerge. (n.d.). Childhood trauma questionnaire– short form [Evidence-based Measures of Empowerment for Research on Gender Equality (EMERGE)]. Retrieved 13 September 2023, from https://emerge.ucsd.edu/r_3em79y3tlxrmbs3/

- 17.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child abuse & neglect. 2003;27(2):169–90.National unified platform.Women Empowerment in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Barnawi FH. Prevalence and risk factors of domestic violence against women attending a primary care center in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Interpers Violence. 2017;32(8):1171–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdel-Salam DM, ALruwaili B, Osman DM, Alazmi MMM, ALghayyadh SAM, Al-Sharari RGZ, et al. Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence among women attending different primary health centers in Aljouf region, Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(1):598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wali R, Khalil A, Alattas R, Foudah R, Meftah I, Sarhan S. Prevalence and risk factors of domestic violence in women attending the national guard primary health care centers in the Western region, Saudi Arabia, 2018. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abid AAZ, Alsadah A, Abdullah SAA, Abdullah HJS, Saeed AB, Abdulwahab AF. Prevalence and risk factors for abuse among Saudi females, KSA. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2017;68(1):1082–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dwairy M, Achoui M, Abouserie R, Farah A, Sakhleh AA, Fayad M, et al. Parenting styles in Arab societies: a first cross-regional research study. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 2006;37(3):230–47. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Achoui M. Children disciplining within the family context: reality and attitudes. J Arab Child. 2003;16:9–38. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joudah G, Radwan R. From protection to prevention, how Saudi Arabia’s stance on violence against women has changed.(2021, November 24). Arab News. https://www.arabnews.com/node/1974791/%7B%7B

- 25.CDC. Risk and Protective Factors|Intimate Partner Violence|Violence Prevention|Injury Center|CDC. 2021, November 5. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/riskprotectivefactors.html

- 26.Abramsky T, Lees S, Stöckl H, Harvey S, Kapinga I, Ranganathan M, et al. Women’s income and risk of intimate partner violence: secondary findings from the MAISHA cluster randomised trial in North-Western Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Breunig R. Gender norms and domestic abuse: evidence from Australia. IZA Discussion Papers; 2021.

- 28.Field E, Pande R, Rigol N, Schaner S, Troyer Moore C. On her own account: how strengthening women’s financial control impacts labor supply and gender norms. Am Econ Rev. 2021;111(7):2342–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newiak M, Sahay R, Srivastava N. Intimate partner violence and women’s economic empowerment. 2024.

- 30.Bradley T, Tanwar J. Is intergenerational transmission of violence a strong predictor of intimate partner violence? Evidence from Nepal. J Asian Afr Stud. 2024;59(5):1603–22. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon DJ, Tokpovi VCK. Intimate partner violence among women in Togo: a generalised structural equation modeling approach. BMJ Open. 2024;14(2):e077273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Breunig R. Female breadwinning and domestic abuse: evidence from Australia. J Popul Econ. 2023;36(4):2925–65. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen H, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts C. WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2005. 2005.

- 34.General Authority for Statistics. (2019). Saudi women-the partner of success. https://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/woman_international_day_2020.pdf

- 35.Lin X. Barriers and challenges of female adult students enrolled in higher education: a literature review. High Educ Stud. 2016;6(2):119–26. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mesfer Alqahtani A. Barriers to women’s education: participation in adult education in Saudi Arabia in the past and present. مجلة کلية التربية (أسيوط). 2020;36(4):37–71.

- 37.Masaiti G, Mapoma CC, Sikwibele M, Kasonde M. The relationship between spousal violence and levels of education:: an analysis of the Zambia demographic and health survey 2013/14. Int J Afr High Educ. 2022;9(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Özer M, Fidrmuc J, Eryurt MA. Education and domestic violence: evidence from a natural experiment in Turkey. Kyklos. 2023;76(3):436–60. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stene LE, Jacobsen GW, Dyb G, Tverdal A, Schei B. Intimate partner violence and cardiovascular risk in women: a population-based cohort study. J Women’s Health. 2013;22(3):250–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lightman SL. The neuroendocrinology of stress: a never ending story. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20(6):880–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foss B, Dyrstad SM. Stress in obesity: cause or consequence? Med Hypotheses. 2011;77(1):7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alhalal E. Obesity in women who have experienced intimate partner violence. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(12):2785–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, Perkins C, Lowey H. National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC Med. 2014;12:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Widom CS, Czaja S, Dutton MA. Child abuse and neglect and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration: a prospective investigation. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38(1):650–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trott M, Bull C, Arnautovska U, Siskind D, Warren N, Najman JM et al. Emergency department presentations for injuries following agency-notified child maltreatment: results from the childhood adversity and lifetime morbidity (CALM) study. Child maltreatment. 2024:10775595241264009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Whitten T, Tzoumakis S, Green MJ, Dean K. Global prevalence of childhood exposure to physical violence within domestic and family relationships in the general population: a systematic review and proportional meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2024;25(2):1411–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.