Introduction

An increasing understanding of the developmental origins of kidney health throughout the lifespan of an individual has increased the emphasis on early recognition of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in children and young people.1, 2, 3 Although the most common causes of CKD in this population are congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract and genetic kidney diseases,4 advances in the treatment of pediatric critical and chronic disease has improved survival into adulthood where CKD may develop as a result of developmental, nutritional, or treatment-related effects on the kidneys.

Regardless of primary pediatric CKD diagnosis, the control of well-established and modifiable risk factors (such as hypertension, obesity, and nephrotoxin exposure) can slow CKD progression.4 It follows that the early recognition and management of CKD in at-risk children is critical to optimize long term kidney health.

As is often the case in adults, CKD in children can progress to advanced stages without conspicuous clinical signs or symptoms. This clinically silent nature of early-stage CKD makes the epidemiological study of CKD prevalence in children difficult.5 Contemporary, population-level database studies estimate this prevalence to be between 0.1% and 0.35%.6, 7, 8 Even accounting for potential limitations, pediatric CKD may appear uncommon when compared with the reported global adult CKD prevalence estimate of 9%.9 As an asymptomatic entity perceived as rare, there exists an availability heuristic whereby CKD may be overlooked in at-risk pediatric patients.

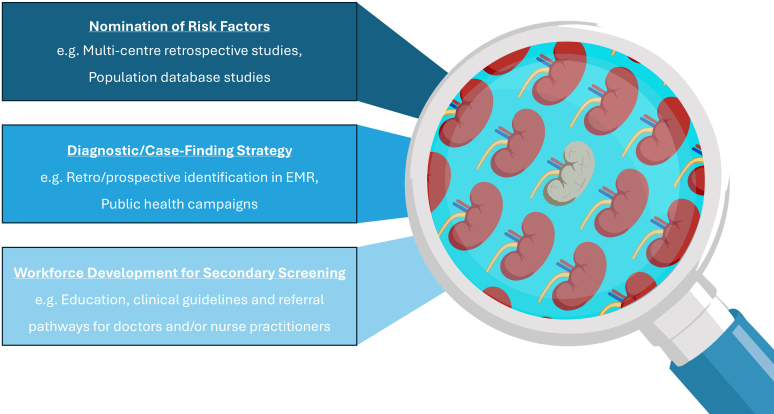

The recognition of pediatric CKD therefore requires conscious consideration of individual risk combined with appropriate clinical and biochemical screening. Defining at-risk pediatric populations from neonates to adolescents for CKD secondary screening and protocolizing the necessary screening tools and frequencies is important to facilitate early diagnosis and to slow pediatric CKD progression (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Improving the detection of chronic kidney disease in children requires the following: (i) identification of risk factors for chronic kidney disease in novel populations, (ii) mechanisms to identify these patients prospectively and retrospectively, and (iii) resourcing of primary care and general pediatric healthcare settings to deliver secondary screening efficiently.

Case Finding for Reduced Nephron Endowment

The concept of the developmental origin of adult kidney disease is more pertinent to neonates than any other age cohort. In the human embryo, nephron development commences around 9 weeks of gestation with the insertion of the ureteric bud into the metanephric mesenchyme. A nephrogenic zone then extends radially, increasing nephron number until nephron progenitor cells are extinguished around 36 weeks of gestation, and the lifetime nephron endowment of the individual is finalized, varying between 200,000 and over 2.5 million nephrons.S1 Over 10% of pregnancies result in premature delivery with about 95% survival. Although nephrogenesis can continue in the ex utero environment, altered kidney development leads to reduced nephron endowment in these infants.S2,S3

Numerous studies associate prematurity and low birthweight with the early development of CKD. A Swedish birth registry study observed a 5-fold increase in CKD in ex-premature children (up to 9 years of age) compared with term-born controls. When stratified by gestational age, even children born at 34 to 36 weeks gestation suffered CKD at 4.8 times that of term-born controls.S4 In a smaller secondary analysis of 2-year outcomes of the Preterm Erythropoietin Neuroprotection Trial, 18% of 832 extremely premature infants (< 28 weeks) had a reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate, 36% had an albuminuria, and 22% had an elevated systolic blood pressure.S5 A Norwegian birth registry study also found that low birthweight and small for gestational age infants had increased risk of CKD in adulthood.S6

Case Finding After Acute Kidney Injury

Beyond the risk posed by reduced nephron endowment, acute kidney injury (AKI) is well-established to contribute to CKD risk. Neonatal AKI complicates 30% of neonatal intensive care unit admissions, with half of episodes graded as severe (Stage 3).S7 Autopsy studies suggest that AKI potentiates the effect on impaired nephrogenesis with that of prematurity.S2Approximately one-third of neonates suffering from AKI will show evidence of CKD in childhoodS8; however, dichotomizing risk according to AKI status ignores other potential contributors to CKD risk, including prematurity, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy nephrotoxic medication exposure, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, among others.S9,S10,S11

Another high-risk group is patients suffering from congenital cardiac disease. The NEPHRON investigators documented cardiac surgery-associated AKI in 59% of 1657 babies undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass and 39% of 583 babies following noncardiopulmonary bypass surgery, with the majority experiencing transient stage 1 AKI on the first postoperative day.S12 The association of CKD with AKI in this cohort is more variable, suggesting that congenital cardiac disease itself informs a degree of risk, independent of AKI.S13,S14 In addition, AKI following cardiac surgery occurs in a unique and supported environment where association of stage 1 and 2 AKI and short-term adverse outcomes is weak. Therefore, regardless of AKI status, it seems patients with critical congenital cardiac disease require CKD screening.

Considering pediatric AKI more broadly, most pediatric centers would recognize the need for long-term CKD screening in any patient requiring acute kidney support therapy for AKI but the need for this screening following milder AKI is less clear. In a prospective Canadian cohort study examining outcomes 1 to 3 years after pediatric intensive care unit admission, 10% of patients developed CKD and 47% developed CKD risk.S15 A more recent retrospective single-center cohort study examined over 4000 children following AKI not requiring kidney support therapy compared with hospitalized controls. After 10 years follow-up, 16% of AKI survivors had CKD compared with 2% of controls, a level of risk comparable to children with convalescent AKI that required kidney support therapy.S16

Undiagnosed CKD Case Finding

Examples of chronic disease groups at risk of CKD because of disease or treatment related factors include cystic fibrosis, malignancy, transplantation, and diabetes, among others. These patients are engaged with their primary specialists, providing an opportunity to integrate kidney screening into practice.

In the absence of a high-risk primary diagnosis, subtle signs of kidney disease in otherwise healthy children often go unnoticed. An example of a successful case finding effort surrounds microscopic hematuria and the identification of genetic variants in Alport Syndrome (AS) genes (COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5) using advanced genomic sequencing technologies. Two-thirds of patients referred with persistent hematuria to a pediatric nephrology service will return an AS diagnosis, and half of pediatric patients in one study had an absent family history.S17,S18 Early introduction of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in males with X-linked AS or individuals with autosomal recessive AS may defer end-stage kidney disease by decades, and is recommended treatment from the time of diagnosis.S19 The early diagnosis of AS by genomic sequencing therefore represents the most significant opportunity in recent history to reduce CKD-life years for patients and, following cascade testing, their extended family.

Such is the imperative that large scale retrospective audit of entire electronic medical record systems is underway to identify incidental cases of unresolved microscopic hematuria to contact and offer genomic sequencing for AS.S20 The role of polygenic risk for CKD is in evolution, and current scoring analyses lack the specificity to predict individual risk; however, improvements in genomic understanding may improve this in future.S21 Utilizing such genetic testing sequentially with electronic case finding holds the promise of improving outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Implementation

Recognition of risk is the first step in pediatric CKD case finding (Figure 1). Establishment of follow-up pathways and protocols to facilitate secondary screening are lacking in many centers.S22

The documentation of AKI and thus nephrology follow-up of neonatal intensive care unit survivors is poor even in well-resourced health services, most likely omitted within the complex details of their often prolonged neonatal intensive care unit admissions.S23,S24 In addition, the functional markers currently available (i.e., serum creatinine) lack the specificity to detect reductions in the high pediatric functional renal reserve. In 2024, the Neonatal Kidney Collaborative published a Delphi Consensus Statement protocolizing the follow-up of neonates with a history of ex-prematurity, AKI, and/or critical cardiac disease.1 This guideline recommends education of families at discharge to encourage prudent renal preservation measures and to avoid unnecessary anxiety.

A similar approach has shown benefit in adult practice. A recent trial randomized adult AKI-recovered patients, to either a care plan informed by their CKD risk profile at the point of discharge, or standard discharge practice. They demonstrated improved prescription of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and statins to appropriate patients and improved the nephrology follow-up for patients with CKD stage 4 to 5 by 78%.S25

The bulk of CKD screening is likely to fall to primary care or general pediatrics services. This is convenient for patients if it integrates into other assessments; however, the level of non-nephrologist comfort with blood pressure assessment and interpretation of CKD screening tests in these settings is variable. The use of familiar, low-cost and well-validated assays to characterize CKD risk such as creatinine and total protein-to-creatinine ratio should be encouraged. General practitioners are often more familiar with urine albumin-to-creatinine ratios in adult practice. However, the normal range in children (and particularly in teenagers) is not well-validated and mild elevations often lead to unnecessary anxiety and additional testing while awaiting non-urgent nephrology advice.6 There is no evidence advocating that urine albumin is superior to urine total protein in identifying patients for initiation of CKD therapies.

Establishing local protocols and referral pathways to support community clinicians to perform and interpret CKD screening tests, reinforce basic kidney health messages, and refer appropriately, will define successful delivery of care at scale. A role for nurse practitioners has also been highlighted in adult practice, where guideline-concordant care and clinical outcomes were better for patients managed by nurse practitioners than for primary care doctors or nephrologists.S26

Conclusion

Improvements in treatments across many areas of neonatal and pediatric medicine improved longevity, revealing a previously unappreciated increased lifetime risk of CKD. Data-led approaches using population level databases and automating CKD risk-recognition tools within electronic medical records will streamline identification of at-risk patients and guide their follow-up appropriately. The delivery of secondary screening for CKD is not complex but will ideally be supported by local protocols and resources to assist non-nephrology clinicians in decision-making.

Disclosure

TAF is the Nephrology Lead for the Australian and New Zealand Chapter of the Neonatal Kidney Collaborative. DTS is an executive member of the Neonatal Kidney Collaborative and has done consulting work for Bioporto.

Footnotes

Supplementary References.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary References.

References

- 1.Starr M.C., Harer M.W., Steflik H.J., et al. Kidney health monitoring in neonatal intensive care unit graduates: A modified Delphi consensus statement. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.35043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstein S.L., Akcan-Arikan A., Alobaidi R., et al. Consensus-based recommendations on priority activities to address acute kidney injury in children: A modified Delphi consensus statement. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.29442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Francis A., Harhay M.N., Ong A.C.M., et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2024;20:473–485. doi: 10.1038/s41581-024-00820-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.VanSickle J.S., Warady B.A. Chronic kidney disease in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2022;69:1239–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2022.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harambat J., Madden I. What is the true burden of chronic kidney disease in children worldwide? Pediatr Nephrol. 2023;38:1389–1393. doi: 10.1007/s00467-022-05816-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saydah S.H., Xie H., Imperatore G., Burrows N., Pavkov M. Trends in albuminuria and GFR among adolescents in the United States, 1988–2014. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;72:644–652. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, 2024, National Institutes of Health, 2024 USRDS Annual Data Report. https://usrds-adr.niddk.nih.gov/2024

- 8.Geylis M., Coreanu T., Novack V., Landau D. Risk factors for childhood chronic kidney disease: a population-based study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2023;38:1569–1576. doi: 10.1007/s00467-022-05714-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2020;395:709–733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30045-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary References.