Abstract

Background

The prognosis of ground glass opacity featured lung adenocarcinomas (GGO-LUAD) is significantly better than that of solid nodule featured lung adenocarcinomas (SN-LUAD), but the underlying reasons remain unclear. Ki-67 and cell cycle regulator proteins are highly expressed in many cancers and linked to prognosis. This study aims to investigate their differential expression in LUAD with different radiological subtypes.

Methods

Patients with resected pathological stage 0−III LUAD in our department between July 2019 and March 2022 were retrospectively reviewed. All included patients were divided into four groups based on different consolidation-to-tumour ratio (CTR), we focuses on evaluating the differential expression of Ki-67 and cell cycle regulatory proteins (CCNA2, CCNB1, CCND1, P16, P21, TOP2A, TP53, and pRb) in LUAD with different CTR.

Results

A total of 481 patients were included, 108 in the pure ground glass opacity (PGGO, CTR = 0) group, 103 in the GGO-dominant (GGO-D, 0 < CTR ≤ 0.5) group, 74 in the SN-dominant (SN-D, 0.5 < CTR < 1) group, and 196 in the pure solid nodule (SN, CTR = 1) group. The expression of Ki-67 was significantly higher in elderly patients (P < 0.05), former or current smokers (P < 0.0001), males (P < 0.05), poorly differentiated tumors (P < 0.0001), and tumors with spread through air spaces (STAS) (P < 0.0001), and advanced stage tumors (P < 0.0001). Regardless of age, gender, smoking status and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation status, GGO-LUAD demonstrated significantly lower expression of Ki-67 compared to SN-LUAD. The expression of Ki-67 and cell cycle regulatory proteins (except P21) were significantly lower in the PGGO, GGO-D, SN-D than in the SN group. However, there was no significant difference in the expression of Ki-67 and cell cycle regulatory proteins among the PGGO, GGO-D, and SN-D groups.

Conclusions

GGO-LUAD demonstrated significantly lower expression of Ki-67 and cell cycle regulatory proteins compared to SN-LUAD, which may explain the reasons behind the excellent prognosis of GGO-LUAD.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12931-025-03217-6.

Keywords: Ki-67, Cell cycle regulator protein, Lung adenocarcinoma, Ground-glass opacity, Radiological subtype

Introduction

Since the Japan Clinical Oncology Group JCOG0201 trial [1] first defined radiological noninvasive lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) as a tumor with a size ≤ 2 cm and a consolidation-to-tumour ratio (CTR) ≤ 0.25 and demonstrated that the presence of a ground glass opacity (GGO) component predicts favourable prognosis [2], thoracic surgeons have increasingly recognised that for resectable LUAD, CTR values are more predictive of prognosis than the maximum tumor diameter [3, 4]. Concurrently, numerous studies on GGO featured lung adenocarcinomas (GGO-LUAD) have shown that tumours containing GGO components are associated with an excellent prognosis, even when the GGO component constitutes less than 10% [5–8]. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanisms responsible for the favourable prognosis of GGO-LUAD remain poorly understood.

Ki-67, a biomarker of cellular proliferation, has demonstrated prognostic significance in various malignancies, including lung cancer [9]. Similarly, cell cycle regulator proteins play pivotal roles in cell growth, DNA replication, and cell division, with tumorigenesis and progression being closely linked to the dysregulation of these proteins [10]. We therefore hypothesised that the favourable prognosis of GGO-LUAD may be associated with Ki-67 and cell cycle regulator protein expression levels. Previous studies have primarily compared Ki-67 expression across different histological subtypes of LUAD [11–13]. However, LUAD with distinct radiological subtypes can encompass any histological subtype. Thus, investigating the differential expression of Ki-67 and cell cycle regulator proteins among radiological subtypes of LUAD is of significant clinical and scientific relevance. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have described the differential expression of Ki-67 and cell cycle regulatory proteins in LUAD patients with different radiological subtypes.

In this study, we first examined the expression of Ki-67 in LUAD patients with different CTRs and its correlation with clinicopathological characteristics. Furthermore, we constructed tissue microarrays (TMA) to systematically analyse the differential expression of key cell cycle regulator proteins in these patients.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue samples

Patients with resected pathological stage 0−III lung adenocarcinoma in our department between July 2019 and March 2022 were retrospectively reviewed. Patients who met the following criteria were included in this study: (1) primary pathological stage 0−III lung adenocarcinoma; (2) single tumor; (3) pathological Ki-67 expression data available. All patients received surgical treatment and none of them underwent neoadjuvant therapy before surgery. According to different CTR values, patients were assigned to four groups: pure ground glass opacity group (PGGO, CTR = 0), GGO-dominant featured LUAD group (GGO-D, 0 < CTR ≤ 0.5), SN-dominant featured LUAD group (SN-D, 0.5 < CTR < 1), and pure solid nodule group (SN, CTR = 1). Additionally, tumors without GGO component were defined as SN-LUAD (CTR = 1) and the other tumors with GGO were defined as GGO-LUAD (0 ≤ CTR < 1). A flowchart of patient selection and study design is shown in Fig. 1. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (No.2019-S110) and due to the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for patient informed consent was waived. This study was also conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient selection and study design

Radiological and histological evaluation

All lesions were evaluated using high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) images. All chest CT scannings were obtained at full inspiration and were retrospectively examined for lesions, especially GGO. The diameter of the tumor was defined as the largest axial diameter of the nodule on the lung window setting, where consolidation was defined as a homogeneous increase in pulmonary parenchymal attenuation that obscures the margins of airway walls and vessels, while GGO was defined as hazy increased opacity of lung, with preservation of bronchial and vascular margins. The CTR was calculated as the ratio of the longest diameter of the solid portion divided by the longest tumor diameter. Each lesion on preoperative CT scannings was reviewed blindly by two experienced thoracic surgeons (YC and XF). When independent assessments disagreed, the images were viewed and discussed together to reach a final consensus.

Two experienced pathologists (pathologist SQ and JX) blinded to the clinical outcomes of the patient reviewed hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained tissue sections. Histological types of the tumors were classified according to the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) /American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) classification of lung adenocarcinomas as adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA), and invasive adenocarcinoma (IAC), histopathological confirmed invasive adenocarcinoma with precise subtype classification: lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma (LPA), acinar predominant adenocarcinoma (APA), papillary predominant adenocarcinoma (PPA), micropapillary predominant adenocarcinoma (MPA) or solid predominant adenocarcinoma (SPA) [14]. The disease TNM stage was assigned on the basis of the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM Staging Manual [15].

Tissues microarrays construction and immunohistochemistry

We used formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples from surgically tumors to create a TMA for IHC analysis. All tissue microarrays are produced by Xinchao Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. In brief, a TMA machine (AlphaMetrix Biotech, Ro¨dermark, Germany) was used to extract one 1.5-mm cylindrical core samples from each tumour block. Before TMA was used for IHC analysis, we performed HE staining again on all TMA for sample quality testing, and unqualified TMA were excluded.

Consecutive slides of TMA samples were used. IHC was performed as previously described [16]. In brief, Slides were deparaffinized, hydrated to water, and subjected to microwave antigen, retrieval in a citrate buffer-pH 6.0 (excluding Cyclin B1 (CCNB1), P21 and P16 staining, EDTA-pH 9.0 buffer). After blocking endogenous peroxidase activity and excess binding sites with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min and 5% bovine serum albumin for 30 min respectively, slides were incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Then, the slides were incubated at room temperature with the corresponding secondary antibody for 30 min. Immunoreactivity was visualized using DAB method (GK600505, GeneTech, Shanghai, China). Slides stained without primary antibody were regarded as the negative control.

The antibodies used for the IHC analyses were as follows: CCNB1 (Ab32053, 1:250 dilution; Abcam, MA, USA), P16 (Ab108349, 1:1000 dilution; Abcam, MA, USA), P21 (Ab109520, 1:1000 dilution; Abcam, MA, USA), Cyclin D1 (CCND1) (clone# 5506S, 1:1000 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA), Cyclin A2 (CCNA2) (clone# 67955, 1:1600 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA), TOP2A (12286 T, 1:400 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA), pRb (clone# 8516 T, 1:800 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA), and p53 (Santa Cruz, clone DO1 SC-126, 1:800 dilution; USA). The detailed procedure was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

IHC analysis and scoring of cell cycle regulator proteins

H-score was used to assess cell cycle regulator proteins expression on tumor cells. H-score was determined by multiplying the percentage of membrane stained cells by an intensity score as previously described [17]. In brief, the staining intensity of the positive cell was scored as follows: 1 + (weak staining), 2 + (moderate staining), and 3 + (strong staining). The proportion of positive cells was evaluated as a percentage of the stained area in the tumor area and was scored from 0 to 100. We calculated the H-score as the maximum multiplied product of the intensity and proportion scores (0–300). The slides were independently evaluated by (R.Q. and pathologist S.Q., J.X.) in a blinded fashion.

Ki-67 expression and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation detection

The expression of Ki-67 protein in the patient’s tumor is routinely detected by the pathologist after surgery. The expression level of Ki-67 protein can be represented by the Ki-67 labeling index (LI), which refers to the percentage of Ki-67-positive nuclei under the microscope in IHC tests. Ki-67 LI of all patients included in this study was obtained from postoperative pathology reports. For the tumor EGFR detection, as described in previous studies [18]. In brief, genomic DNA was extracted from fresh tissues using the QIAamp DNA Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germany). EGFR mutations were detected using commercially available kits from YZY Medical (Wuhan, China) based on amplification refractory mutation system real-time polymerase chain reaction technology.

Statistical analysis

Data in bar graphs are presented as mean and SD. We used Student’s unpaired t-test, Mann–Whitney U test or One-Way ANOVA for the comparison of continuous variables. The chi-square χ2 test or Fisher’s exact-test was adopted to compare the distribution of categorical variables. Multivariate linear regression analysis was performed to analyse infuencing factors of clinical variables. Linear regression analysis was used to test the relationship between the two continuous variables. Propensity matched analysis were performed using STATA 17.0 software (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). A total of 209 patients with unknown EGFR status were excluded from the analysis. The remaining patients were categorized into the GGO-LUAD (CTR < 1) group and SN-LUAD (CTR = 1) group. The following covariates were subjected to propensity score-matched analysis using a logistic regression model: age, gender, history of smoking, tumor size, histology, differentiation, STAS status, p-stage and EGFR status. Selected cases from the 2 groups were matched at a ratio of 1:1 using the nearest-neighbor method with a caliper width of 0.02. All P values are two sided and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001). Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS V.26.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism 9.5 (Graph-Pad Software, Inc.)

Results

Patient and tumor characteristics

A total of 481 patients were included, including 108 in the PGGO group, 103 in the GGO-D group, 74 in the SN-D group, and 196 in the SN group. Most of the patients were nonsmokers (388, 80.7%), women (292, 60.7%), younger (353, 73.3%), and diagnosed with pathological stage 0−I disease (413, 85.8%). Notably, except for three patients, all patients with GGO-LUAD (including the PGGO, GGO-D, and SN-D groups) were classified as pStage 0−I. The predominant pathological subtype of the tumours was IAC (331, 68.8%), with most tumors exhibiting good or moderate differentiation (208, 43.2%). Among the patients in the cohort, 272 underwent EGFR mutation testing, 165 (66.7%) of whom harboured EGFR mutations. A significant trend was observed in which the EGFR mutation rate increased with the proportion of solid components in the tumors. The detailed patient and tumor characteristics are summarised in Tables 1 and S1.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathologic characteristics of all patients

| Variables | PGGO (n = 108) (%) | GGO-D (n = 103) (%) | SN-D (n = 74) (%) | SN (n = 196)(%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Year ± SD) | 47.7 ± 14.0 | 54.2 ± 12.9 | 55.3 ± 11.3 | 58.1 ± 10.6 | < 0.001 |

| ≤ 60 | 94 (87.0) | 76 (73.7) | 54 (72.9) | 129(65.8) | |

| > 60 | 14 (13) | 27 (26.3) | 20 (27.1) | 67 (34.2) | |

| Gender (Female) | 77 (71.2) | 55 (53.3) | 48 (64.8) | 112(57.1) | 0.030 |

| Smoking status | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 99 (91.7) | 80 (77.6) | 70 (94.5) | 139(70.9) | |

| Current or former | 9 (8.3) | 23 (22.4) | 4 (5.5) | 57 (29.1) | |

| Tumor size (mean ± SD, mm) | 16.0 ± 11.9 | 20.6±11.7 | 21.6±11.6 | 30.7±14.0 | <0.001 |

| ≤ 10 mm | 62 (57.4) | 30 (29.1) | 12 (16.2) | 12 (6.1) | |

| > 10, ≤ 20 mm | 38 (35.2) | 53 (51.5) | 44 (59.5) | 72 (36.8) | |

| > 20, ≤ 30 mm | 6 (5.5) | 1312.6 | 14 (18.9) | 67 (34.2) | |

| > 30 mm | 2 (1.9) | 7 (6.8) | 4 (5.4) | 45 (22.9) | |

| Histology | < 0.001 | ||||

| AIS | 37 (34.2) | 10 (9.7) | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0) | |

| MIA | 49 (45.4) | 38 (36.9) | 13 (17.6) | 1 (0.5) | |

| IAC | 22 (20.4) | 55 (53.4) | 59 (79.7) | 195(99.5) | |

| Histological subtype | < 0.001 | ||||

| LPA | 6 (5.5) | 12 (11.6) | 6 (8.1) | 11 (5.6) | |

| APA | 12 (11.1) | 27 (26.2) | 38 (51.4) | 93 (47.4) | |

| PPA | 3 (2.8) | 15 (14.6) | 14 (18.9) | 37 (18.8) | |

| MPA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 14 (7.1) | |

| SPA | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.4) | 27 (13.8) | |

| Differentiation | < 0.001 | ||||

| Well/Moderate-well | 21 (19.4) | 50(48.5) | 51 (68.9) | 86 (43.9) | |

| Moderate-poor/Poor | 1 (0.9) | 3(2.9) | 1 (1.4) | 102(52.0) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 2(1.9) | 7 (9.5) | 8 (4.1) | |

| STAS status | < 0.001 | ||||

| Positive | 1 (0.9) | 3(2.9) | 9 (12.5) | 90 (45.9) | |

| Negative | 107(99.1) | 100(97.1) | 65 (87.5) | 106(54.1) | |

| pTNM stage | < 0.001 | ||||

| 0−I | 108(100.0) | 102(99.1) | 72 (97.2) | 131(66.8) | |

| II | 0 (0) | 1(0.9) | 1 (1.4) | 23 (11.7) | |

| IIIA | 0 (0) | 0(0) | 1 (1.4) | 35 (17.9) | |

| IIIB | 0 (0) | 0(0) | 0 (0) | 7 (3.6) | |

| EGFR status | < 0.001 | ||||

| WT | 42 (38.9) | 22(21.4) | 10 (13.5) | 33 (16.9) | |

| MT | 28 (25.9) | 38(36.9) | 36 (48.6) | 63 (32.1) | |

| Unknown | 38 (35.2) | 43(41.7) | 28 (37.9) | 100(51.0) | |

PGGO pure ground glass opacity, GGO-D GGO-dominant featured lung adenocarcinoma, SN-D SN-dominant featured lung adenocarcinomas, SN solid nodule, AIS adenocarcinoma in situ, MIA minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, IAC invasive adenocarcinoma, LPA lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma, APA acinar predominant adenocarcinoma, PPA papillary predominant adenocarcinoma, MPA micropapillary predominant adenocarcinoma, SPA solid predominant adenocarcinoma, STAS spread through air spaces, EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor, WT wild type, MT mutation type

Associations between Ki-67 expression and clinicopathologic characteristics

The expression of Ki-67 was significantly higher in elderly patients (P < 0.05), former or current smokers (P < 0.0001), men (P < 0.05), patients with poorly differentiated tumours (P < 0.0001), patients with tumors that spread through air spaces (STAS) (P < 0.0001), and advanced-stage patients (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). Similar trends were observed in the cohort of pStage 0–I LUAD patients (Figure S1A, C, D, and E). Notably, no significant difference in Ki-67 expression was found between men and women in the pStage 0−I subgroup (Figure S1B). Additionally, Ki-67 expression increased significantly with increasing pathological stage and increasing tumor diameter (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3A and B). Among patients with varying pathological subtypes, Ki-67 expression was greater in patients with IAC than in those with AIS and MIA (P < 0.0001), with no significant difference observed between patients with AIS and those with MIA (Fig. 3D and E). Furthermore, significant differences in Ki-67 expression were noted among patients with varying histological subtypes of invasive adenocarcinoma (P < 0.0001), with the highest expression in SPA patients and the lowest in LPA patients (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 2.

Associations between Ki-67 expression and clinicopathologic characteristics. Tumor expression of Ki-67 was noted to be higher in A older than younger, B male than female, C patients with advanced pathological stage, D ever smokers, E poorly differentiated rather than moderately or well differentiated tumors, and F patients with STAS + . STAS spread through air spaces

Fig. 3.

Ki-67 expression according to pathological stage, tumor size, histological subtypes and pathological subtypes of LUAD. A Ki-67 expression differed across pathological stage, B Ki-67 expression significantly increased with the increase of tumor size, C Ki-67 expression differed across histological subtypes, D and E Ki-67 expression differed across pathological subtypes. LUAD lung adenocarcinomas

In this study, no significant differences in Ki-67 expression were observed between patients with and without EGFR mutations (Fig. 4A and D). However, an intriguing finding was a significant correlation between Ki-67 expression and the EGFR mutation status in GGO-LUAD patients but not in SN-LUAD patients (Fig. 4B, C, and F). Specifically, within GGO-LUAD patients, tumors harbouring EGFR mutations presented significantly higher Ki-67 expression than those without EGFR mutations (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Associations between Ki-67 expression and EGFR mutation status. A no differences in Ki-67 expression were observed between all LUAD with EGFR mutations and without, B tumors with EGFR mutations have significantly higher Ki-67 expression than wild-type tumors in GGO-LUAD, C but not in SN-LUAD, D no differences in Ki-67 expression were observed between pStage 0–I LUAD with EGFR mutations and without, E tumors with EGFR mutations have significantly higher Ki-67 expression than wild-type tumors in pStage I GGO-LUAD, F but not in pStage 0–I SN-LUAD. EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor, LUAD lung adenocarcinomas, GGO-LUAD ground-glass opacity featured lung adenocarcinomas, SN-LUAD solid nodule featured lung adenocarcinomas

Associations between Ki-67 expression and tumours with different CTRs

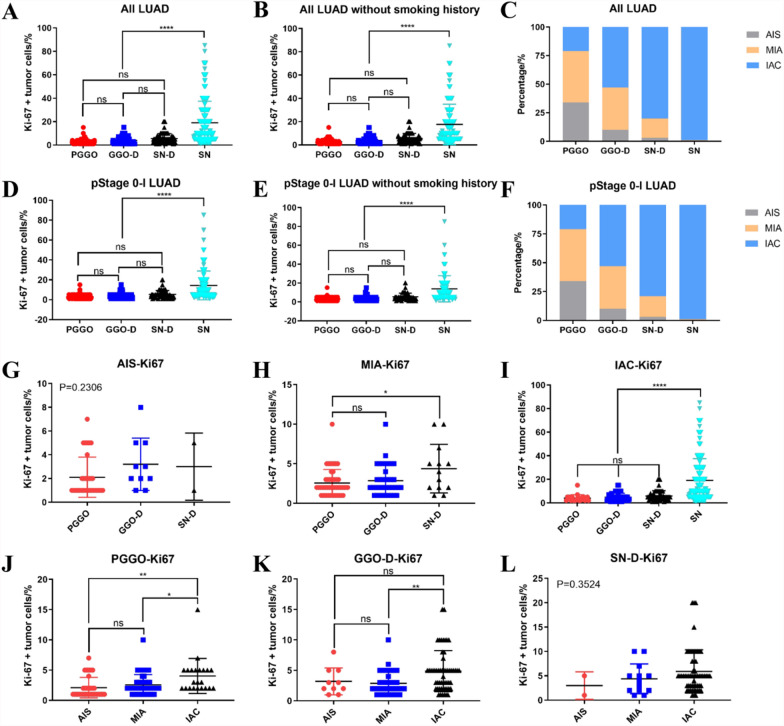

We divided all patients into four groups on the basis of GGO components and determined significant differences in Ki-67 expression among the four groups (P < 0.0001). Interestingly, we found that among the PGGO, GGO-D, and SN-D groups, there were no significant differences in Ki-67 expression (Fig. 5A and D). The above conclusion can also be drawn in nonsmokers (Fig. 5B and E). We also found that, regardless of age, gender, and EGFR mutation status, GGO-LUAD patients presented significantly lower expression of Ki-67 than SN-LUAD patients did, and there was no significant difference in Ki-67 expression among the PGGO, GGO-D, and SN-D groups (Figure S2). Multivariate linear regression analysis were then preformed to identify factors associated with Ki-67 expression. We found that gender, age, smoking history, and EGFR mutation status were not significantly correlated with Ki-67 expression (P > 0.05), and only the CTR value was significantly positively correlated with Ki-67 expression (P < 0.0001) (Table S2). We can see that the distributions of AIS, MIA, and IAC among the four groups are inconsistent. The PGGO group had the highest proportion of AIS, whereas the SN group had the highest proportion of IAC. With increasing amounts of solid components, the proportion of IAC also increased (Fig. 5C and F). In the cohort of pStage 0-I LUAD patients, consistent conclusions could also be drawn.

Fig. 5.

Associations between Ki-67 expression and different CTR tumor. A, B, D and E differential analysis of Ki-67 expression in lung adenocarcinoma with different CTR, C and F the distribution proportions of AIS, MIA, and IAC among different CTR groups, G, H and I Ki-67 expression in lung adenocarcinoma with the same pathological subtype but different CTR, J, K and L Ki-67 expression in lung adenocarcinoma with the same CTR but different pathological subtype. CTR, consolidation-to-tumour ratio, AIS, adenocarcinoma in situ, MIA minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, IAC invasive adenocarcinoma

Next, we performed correlation analyses on the basis of continuous CTR value data (Figure S3). We found a significant positive correlation between CTR values and Ki-67 expression, but this significant correlation was not strong in GGO-LUAD patients, once again indicating that LUAD containing GGO components have weaker overall tumor growth ability. At the same time, we also further conducted a propensity score matching analysis to minimize the interference of confounding factors to the greatest extent possible between GGO-LUAD and SN-LUAD groups (Table S3). After propensity score matching, there was no significant difference in clinical and pathological data among the groups of patients. Then, we conducted differential analysis on the expression of Ki67 between GGO-LUAD and SN-LUAD groups and found that GGO-LUAD demonstrated significantly lower expression of Ki-67 compared to SN-LUAD (P = 0.001). Similarly, in 31 cases of GGO-LUAD, there was no significant difference in Ki-67 expression among the PGGO (8 cases), GGO-D (13 cases), and SN-D (10 cases) groups.

Finally, we analysed Ki-67 expression in each pathological type or CTR group. We found that the GGO components had little effect on the expression of Ki-67 in patients with AIS or MIA (Fig. 5G and H). In contrast, in IAC patients, as long as the GGO component was present, there was still no difference in the expression of Ki-67 (Fig. 5I), indicating that the GGO component has a greater impact on Ki-67 expression levels than the solid component does. Strikingly, in the PGGO, GGO-D and SN-D groups, overall Ki-67 expression in IAC patients was greater than that in AIS and MIA patients, whereas there was no difference between the AIS and MIA groups (Fig. 5J, K and L)In summary, the pathological subtypes of tumors are more indicative of tumour proliferation ability than GGO components.

Cell cycle regulator protein expression in different CTR groups

Cell cycle regulatory proteins are key factors regulating cell proliferation. Therefore, we investigated whether there were differences in the expression of cell cycle regulator proteins among the four groups with different CTRs. We first utilised tumor tissues from some patients in the overall cohort for TMA production and then performed immunohistochemical staining analysis of cell cycle regulator protein expression using TMA. Table 2 shows the clinical and pathological characteristics of the patients in the TMA cohort. A total of 91 patients in the TMA cohort were included, including 32 in the PGGO group, 25 in the GGO-D group, 20 in the SN-D group, and 14 in the SN group. Representative images of CCNA2, P16 and pRb expression among the four groups are shown in Figure S4. The H score was used to assess the expression of cell cycle regulator proteins in tumor cells. We found significant differences in the expression of cell cycle regulator proteins, with the exception of P21 (Fig. 6F), among the different CTR groups. Among these, the expression of proteins directly involved in the cell cycle (CCNA2, CCNB1, CCND1, and P16) gradually increased with increasing solid components (Fig. 6A, B, C and E). However, there was no significant difference in the expression of the above proteins among the PGGO, GGO-D, and SN-D groups. Similarly, the expression of proteins indirectly involved in the cell cycle (TOP2A, TP53, and pRb) was significantly greater in the SN group than in the other three groups (Fig. 6D, G and H)).

Table 2.

Clinical and pathologic characteristics of Patients in TMA cohort

| Variables | PGGO (n = 32) (%) | GGO-D (n = 25) (%) | SN-D (n = 20) (%) | SN (n = 14) (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Year ± SD) | 53.7 ± 12.3 | 58.7 ± 8.9 | 55.5 ± 9.8 | 60.2 ± 7.8 | < 0.001 |

| ≤ 60 | 25 (78.1) | 13 (52.0) | 16 (80.0) | 8 (57.1) | |

| > 60 | 7 (22.9) | 12 (48.0) | 4 (20.0) | 6 (42.9) | |

| Gender (Female) | 23 (71.8) | 11 (44.0) | 11 (55.0) | 9 (64.3) | 0.185 |

| Smoking status | 0.376 | ||||

| No | 28 (87.5) | 18 (72.0) | 17 (85.0) | 10 (71.4) | |

| Current or former | 4 (12.5) | 7 (28) | 3 (15.0) | 4 (28.6) | |

| Tumor size (mean ± SD, mm) | 13.1 ± 4.9 | 21.0 ± 8.0 | 18.5 ± 6.1 | 20.7 ± 4.6 | < 0.001 |

| ≤ 10 mm | 14 (43.7) | 4 (16.0) | 3 (15.0) | 1 (7.1) | |

| > 10, ≤ 20 mm | 16 (50.0) | 14 (56.0) | 12 (60.0) | 7 (50.0) | |

| > 20, ≤ 30 mm | 2 (6.3) | 5 (20.0) | 5 (25.0) | 6 (42.9) | |

| > 30 mm | 0 (0) | 2 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Histology | < 0.001 | ||||

| AIS | 16 (50.0) | 2 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| MIA | 14 (43.7) | 12 (48.0) | 5 (25.0) | 0 (0) | |

| IAC | 2 (6.3) | 11 (44.0) | 15 (75.0) | 14 (100.0) | |

| Histological subtype | 0.003 | ||||

| LPA | 0 (0) | 6 (24.0) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0) | |

| APA | 2 (6.3) | 1 (4.0) | 10 (50.0) | 9 (64.3) | |

| PPA | 0 (0) | 4 (16.0) | 4 (20.0) | 1 (7.1) | |

| MPA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (14.3) | |

| SPA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (14.3) | |

| Differentiation degree | 0.009 | ||||

| Well/moderate-well | 2 (6.3) | 13 (52.0) | 11 (55.0) | 7 (50.0) | |

| Moderate-poor/poor | 0 (0) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (5.0) | 7 (50.0) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (15.0) | 0 (0) | |

| STAS status | < 0.001 | ||||

| Positive | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (42.9) | |

| Negative | 32 (100.0) | 25 (100.0) | 20 (100.0) | 8 (57.1) | |

| pTNM stage | < 0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 16 (50.0) | 2 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| IA1 | 14 (43.7) | 13 (52.0) | 9 (45.0) | 1 (7.1) | |

| IA2 | 2 (6.3) | 6 (24.0) | 9 (45.0) | 3 (21.4) | |

| IA3 | 0 (0) | 2 (8.0) | 1 (5.0) | 9 (64.3) | |

| IB | 0 (0) | 2 (8.0) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (IIIA, 1) | |

| EGFR status | 0.001 | ||||

| WT | 21 (65.6) | 6 (24.0) | 3 (15.0) | 4 (28.5) | < 0.001 |

| MT | 11 (34.4) | 19 (76.0) | 17 (85.0) | 10 (71.5) | |

TMA tissue microarrays, PGGO pure ground glass opacity, GGO-D GGO-dominant featured lung adenocarcinoma, SN-D SN-dominant featured lung adenocarcinomas, SN solid nodule, AIS adenocarcinoma in situ, MIA minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, IAC invasive adenocarcinoma, LPA lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma, APA acinar predominant adenocarcinoma, PPA papillary predominant adenocarcinoma, MPA micropapillary predominant adenocarcinoma, SPA solid predominant adenocarcinoma, STAS spread through air spaces, EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor, WT wild type, MT mutation type

Fig. 6.

Cell cycle regulator proteins expression in different CTR groups. A–H the expression of CCNA2, CCNB1, CCND1, TP53, P16, P21, TOP2A, and pRb in lung adenocarcinoma with different CTR. CTR, consolidation-to-tumour ratio

To further validate the above results, we also used the median protein expression score as the cut-off point for positive and negative expression, as described in previous studies [19]. Histograms demonstrating the expression patterns are shown in Figure S5. As shown in Fig. 7, the expression of cell cycle regulator proteins in the different CTR groups was essentially consistent with the above results.

Fig. 7.

Differences in the positive expression rate of cell cycle regulatory proteins among different CTR groups. A the TMA constructed using clinical samples (HE staining); B the positive expression rates of GGO-LUAD and SN-LUAD on eight cell cycle regulatory proteins (CCNA2, CCNB1, CCND1, P16, P21, TOP2A, TP53, and pRb). CTR consolidation-to-tumour ratio, TMA tissue microarrays

Associations between Ki-67 and cell cycle regulator protein expression

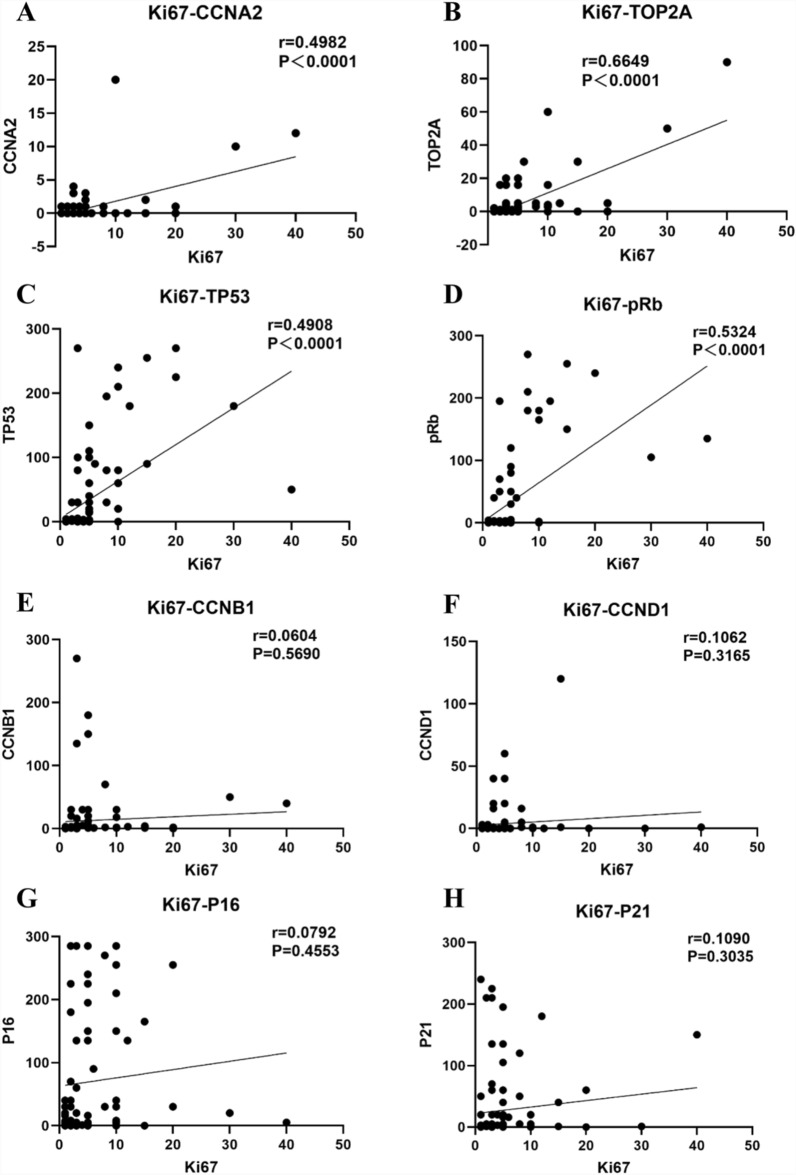

Finally, to evaluate whether the expression of Ki-67 is correlated with the expression of cell cycle regulator proteins, we conducted correlation analysis using protein expression data from the TMA cohort. As shown in Fig. 8A−D, the expression of four cell cycle regulator proteins, namely, CCNA2 (r = 0.4982, P < 0.0001), TOP2A (r = 0.6649, P < 0.0001), TP53 (r = 0.4908, P < 0.0001), and pRb (r = 0.5324, P < 0.0001), was positively correlated with Ki-67 expression. The expression of the remaining four cell cycle regulator proteins (CCNB1, CCND1, P16 and P21) was not correlated with Ki-67 expression (Fig. 8E–H).

Fig. 8.

Associations between Ki-67 and cell cycle regulator proteins expression. A–D the expression of the following four cell cycle regulator proteins showed a positive correlation with Ki-67 expression, namely CCNA2, TOP2A, TP53, and pRb, E–H the expression of the remaining four cell cycle regulator proteins (included CCNB1, CCND1, P16 and P21) is not correlated with Ki-67 expression

Discussion

This study investigated the associations between Ki-67 expression and clinicopathological characteristics, as well as the differential expression of Ki-67 and cell cycle regulatory proteins, in resected LUAD samples with various radiological subtypes. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the differential expression of Ki-67 and cell cycle regulatory proteins in LUAD on the basis of distinct GGO components.

Ki-67 is highly expressed in various malignancies and is closely associated with poor prognosis [11, 20–22]. It is widely utilised as a biomarker to assess tumor proliferative activity and predict clinical outcomes [23]. In this study, we included 481 patients with surgically resected LUAD. First, we analysed the correlation between Ki-67 expression and clinicopathological characteristics. Our findings revealed that Ki-67 expression was significantly positively correlated with older age, smoking history, poor tumour differentiation, advanced pathological stages, and the presence of STAS. These results suggest that high Ki-67 expression serves as a reliable indicator of poor prognosis in LUAD patients, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies [9, 11, 23]. Interestingly, unlike prior studies [11, 23], we did not observe a significant difference in Ki-67 expression between men and women with early-stage LUAD. Further analysis revealed that the proportion of men with a smoking history was significantly lower in early-stage LUAD patients than in later-stage LUAD patients, which may explain the absence of sex differences in Ki-67 expression in this subgroup.

With respect to pathological and histological subtypes, IAC patients presented significantly greater Ki-67 expression than MIA and AIS patients did, whereas SPA and MPA patients presented significantly greater Ki-67 expression than LPA and APA patients did. These findings align with those from previous research [11]. Notably, our study revealed no significant difference in Ki-67 expression between AIS and MIA patients, which contrasts with earlier conclusions [12, 13]. The sample sizes included in studies by Ishida et al. and Jia et al. were relatively small, and Jia et al. used a high percentage (Ki-67 > 10%) of Ki-67 expression for comparison. Therefore, we hypothesise that the discrepancy in conclusions may stem from differences in sample sizes and the criteria used for comparative analysis across studies.

Compared with SN-LUAD patients, growing evidence has shown that GGO-LUAD patients have an excellent prognosis [2–6]. Recent studies have shown that for early-stage lung cancer patients, the 10-year recurrence-free survival rates for surgically resected pure GGO patients, mixed GGO patients, and solid nodule patients are 100%, 89.82%, and 65.83%, respectively [24]. However, the reasons behind the excellent prognosis of patients with GGO-LUAD are still unclear. To clarify the underlying reasons, we divided surgically resected LUAD tissues from 481 patients into four groups on the basis of their CTR values. Comparative analysis of Ki-67 expression in the four groups revealed that GGO-LUAD patients had significantly lower Ki-67 expression than SN-LUAD patients did. Interestingly, although there were differences in pathological subtype distribution among the other three groups of lung adenocarcinoma tissues containing GGO components, there was no significant difference in Ki-67 expression. In other words, there was no significant difference in the proliferative capacities of LUAD tissues containing GGO components. These results explain why GGO-LUAD patients have a good prognosis. Although GGO-LUAD is considered an inert subtype of lung cancer, relevant studies have shown that approximately 20% of pure GGOs and 40% of mixed GGOs will eventually progress [25]. Previous studies have shown that EGFR driver gene mutations are associated with the progression of GGO-LUAD [26]. EGFR mutation is one of the most common driver gene mutations in LUAD patients, with a particularly high mutation rate in Asian populations [27]. Studies have shown that EGFR mutations are significantly correlated with radiological subtypes [28, 29] and are hypothesised to influence tumor cell proliferation [30]. However, the research conclusions reported regarding the correlation between EGFR mutation status and Ki-67 expression are inconsistent. In a cohort of 523 patients with non-small cell lung cancer, Zhu et al. reported that Ki-67-positive tumours harboured more EGFR mutations [31]. In contrast, in a cohort of 118 patients with stage I LUAD, Xu et al. reported that Ki-67 expression was not associated with EGFR mutation status [32]. A study from Li et al. demonstrated that EGFR-WT was correlated with elevated Ki-67 expression [11]. Interestingly, we found that Ki-67 expression was significantly greater in GGO-LUAD patients with EGFR mutations than in those without, and the mutation rate of EGFR increased with an increasing number of solid components in the present study, which is consistent with the findings of Zhong et al. [29]. These results suggest that EGFR mutations may play a key role in the progression of GGO-LUAD and that the specific mechanism needs further exploration.

Dysregulation of the cell cycle machinery is the fundamental cause of uncontrolled proliferation of cancer cells. Numerous studies have shown that cell cycle regulatory proteins play crucial roles in regulating the cell cycle and are closely related to patient prognosis [19, 33, 34]. Therefore, to further elucidate the reasons behind the differential expression of Ki-67 in LUAD with different CTRs, we constructed a TMA to analyse the expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins. We found that in terms of the expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins, with the exception of P21, the expression of other proteins was significantly greater in SN-LUAD patient than in GGO-LUAD patient. Surprisingly, there was no significant difference in the expression of all proteins in LUAD patients with GGO components, which further reveals the reasons behind the good prognosis of patients with GGO-LUAD. This expression difference was most significant for CCNA2, TOP2A, P16, TP53, and pRb, which may be related to the key roles played by these proteins in cell cycle regulation. More importantly, we also found a significant positive correlation between the expression of CCNA2, TOP2A, TP53, and pRb and the expression of Ki-67, suggesting that these proteins play key roles in the progression of GGO-LUAD. The above results have never been reported in previous studies.

There were several limitations to this study. First, there is potential selection bias because this was a single-centre study. Second, although the evaluation of CTRs in our study required at least two experienced thoracic surgeons to complete, there is no consensus on the optimal method for evaluating the extent of GGOs; thus, CTR measurement may be highly variable. Third, because numerous studies have confirmed a good prognosis for patients with GGO-LUAD, we did not analyse the impact of Ki-67 and cell cycle regulatory protein expression on prognosis in this study. Fourth, the sample size in the SN-D group was significantly smaller than that in the other groups, and large-sample research is needed to validate our conclusions in the future. Fifth, this was a single-centre retrospective study that requires external research from multiple centres and other regions for validation. Finally, although the validation of molecular mechanisms was lacking in this study, we will next use organoid technology to construct an in vitro GGO-LUAD model to validate our findings.

Conclusion

In summary, in resected LUAD with different radiological subtypes, GGO-LUAD demonstrated significantly lower expression of Ki-67 and cell cycle regulatory proteins compared to SN-LUAD. More importantly, we found that among the PGGO, GGO-D, and SN-D groups, there was no significant difference in the expression of these proteins. The above results may explain the reasons behind the excellent prognosis of GGO-LUAD, which not only enriches our understanding of the biological inertness of GGO-LUAD but also provides a theoretical basis for further exploration of its mechanism in the future.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank all the contributing authors for their great effort on this article and greatly appreciate all patients who contributed to this study.

Abbreviations

- AIS

Adenocarcinoma in situ

- APA

Acinar predominant adenocarcinoma

- CTR

Consolidation-to-tumour ratio

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- FFPE

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded

- GGO

Ground-glass opacity

- GGO-D

GGO-dominant featured lung adenocarcinoma

- GGO-LUAD

GGO featured lung adenocarcinomas

- IAC

Invasive lung adenocarcinoma

- LPA

Lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma

- MPA

Micropapillary predominant adenocarcinoma

- MIA

Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma

- PGGO

Pure ground glass opacity featured lung adenocarcinomas

- PPA

Papillary predominant adenocarcinoma

- SPA

Solid predominant adenocarcinoma

- SN

Solid nodule

- SN-D

SN-dominant featured lung adenocarcinomas

- SN-LUAD

Solid nodule featured lung adenocarcinomas

- STAS

Spread through air spaces

- TMA

Tissue microarrays

Author contributions

Rirong Qu: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Roles/Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. Yang Zhang: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing—review and editing. Shenghui Qin: Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Visualization. Jing Xiong: Data curation, Project administration, Visualization. Xiangning Fu: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—review and editing. Lequn Li: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review and editing. Dehao Tu: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Roles/Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. Yixin Cai: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Roles/Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Funding

The study is funded by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant Number 2024M761036, the Tongji Hospital Clinical Research Flagship Program (No.2019CR107) and Chen Xiaoping Foundation Youth Research Fund in Hubei Province (CXPJJH11900018-01). The funding sources had no influence on the analysis and interpretation of data or on the contents of the manuscript.

Availabilityof data and materials

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (No.2019-S110) and due to the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for patient informed consent was waived. This study was also conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Dehao Tu, Email: tudehao@hotmail.com.

Yixin Cai, Email: caiyixin@tjh.tjmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Suzuki K, Koike T, Asakawa T, et al. A prospective radiological study of thin-section computed tomography to predict pathological noninvasiveness in peripheral clinical IA lung cancer (Japan Clinical Oncology Group 0201). J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(4):751–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hattori A, Suzuki K, Takamochi K, et al. Prognostic impact of a ground-glass opacity component in clinical stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;161(4):1469–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shigefuku S, Shimada Y, Hagiwara M, et al. Prognostic significance of ground-glass opacity components in 5-year survivors with resected lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(1):148–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ye T, Deng L, Wang S, et al. Lung adenocarcinomas manifesting as radiological part-solid nodules define a special clinical subtype. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(4):617–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li M, Wang J, Bao X, et al. Minor (≤ 10%) ground-glass opacity component in clinical stage i non-small cell lung cancer: associations with pathologic characteristics and clinical outcomes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2024. 10.2214/AJR.24.31283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki S, Sakurai H, Yotsukura M, et al. Clinical features of ground glass opacity-dominant lung cancer exceeding 3.0 cm in the whole tumor size. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105(5):1499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe Y, Hattori A, Nojiri S, et al. Clinical impact of a small component of ground-glass opacity in solid-dominant clinical stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022;163(3):791-801.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Li G, Li Y, et al. Imaging features suggestive of multiple primary lung adenocarcinomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(6):2061–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell KG, Parra ER, Nelson DB, et al. Tumor cellular proliferation is associated with enhanced immune checkpoint expression in stage I non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;158(3):911-919.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suski JM, Braun M, Strmiska V, Sicinski P. Targeting cell-cycle machinery in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(6):759–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Z, Li F, Pan C, et al. Tumor cell proliferation (Ki-67) expression and its prognostic significance in histological subtypes of lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2021;154:69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishida H, Shimizu Y, Sakaguchi H, et al. Distinctive clinicopathological features of adenocarcinoma in situ and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma of the lung: a retrospective study. Lung Cancer. 2019;129:16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jia M, Yu S, Cao L, Sun PL, Gao H. Clinicopathologic features and genetic alterations in adenocarcinoma in situ and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma of the lung: long-term follow-up study of 121 asian patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(8):3052–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/American thoracic society/European respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(2):244–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (Eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(1):39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qu R, Ye F, Hu S, et al. Distinct cellular immune profiles in lung adenocarcinoma manifesting as pure ground glass opacity versus solid nodules. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(7):3775–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper WA, Tran T, Vilain RE, et al. PD-L1 expression is a favorable prognostic factor in early stage non-small cell carcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2015;89(2):181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qu R, Tu D, Ping W, Zhang N, Fu X. Synchronous multiple lung cancers with lymph node metastasis and different EGFR mutations: intrapulmonary metastasis or multiple primary lung cancers? OncoTargets Ther. 2021;14:1093–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Filipits M, Pirker R, Dunant A, et al. Cell cycle regulators and outcome of adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy in completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer: the international adjuvant lung cancer trial biologic program. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(19):2735–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warth A, Cortis J, Soltermann A, et al. Tumour cell proliferation (Ki-67) in non-small cell lung cancer: a critical reappraisal of its prognostic role. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(6):1222–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gandini S, Guerrieri-Gonzaga A, Pruneri G, et al. Association of molecular subtypes with Ki-67 changes in untreated breast cancer patients undergoing pre surgical trials. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(3):618–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li RL, Heydon K, Hammond ME, et al. Ki-67 staining index predicts distant metastasis and survival in locally advanced prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy: an analysis of patients in radiation therapy oncology group protocol 86–10. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(12):4118–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei DM, Chen WJ, Meng RM, et al. Augmented expression of Ki-67 is correlated with clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis for lung cancer patients: an up-dated systematic review and meta-analysis with 108 studies and 14,732 patients. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, Fan F, Yang Z, et al. Ten-year follow-up of lung cancer patients with resected stage IA invasive non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31(9):5729–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kakinuma R, Noguchi M, Ashizawa K, et al. Natural history of pulmonary subsolid nodules: a prospective multicenter study. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(7):1012–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi Y, Mitsudomi T, Sakao Y, Yatabe Y. Genetic features of pulmonary adenocarcinoma presenting with ground-glass nodules: the differences between nodules with and without growth. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(1):156–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou F, Guo H, Xia Y, et al. The changing treatment landscape of EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2025;22(2):95–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong SJ, Kim TJ, Choi YW, et al. Radiogenomic correlation in lung adenocarcinoma with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations: imaging features and histological subtypes. Eur Radiol. 2016;26(10):3660–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhong W, Zhang W, Dai L, Chen M. The clinical, radiological, postoperative pathological, and genetic features of nodular lung adenocarcinoma: a real-world single-center data. J Thorac Dis. 2024;16(5):3228–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, Kuwano H, Takahashi T, Mitsudomi T. Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene in lung cancer: biological and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2004;64(24):8919–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu WY, Hu XF, Fang KX, et al. Prognostic value of mutant p53, Ki-67, and TTF-1 and their correlation with EGFR mutation in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Histol Histopathol. 2019;34(11):1269–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu L, Guo R. Correlation analysis of Ki67 expression and EGFR mutation on the risk of recurrence and metastasis in postoperative patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2022;25(12):852–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esposito V, Baldi A, De Luca A, et al. Cell cycle related proteins as prognostic parameters in radically resected non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(7):734–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohamed S, Yasufuku K, Hiroshima K, et al. Prognostic implications of cell cycle-related proteins in primary resectable pathologic N2 nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2007;109(12):2506–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.