Abstract

Diabetes mellitus, as a common chronic disease, easily leads to significant changes in the structure of the eye, among which diabetic cataract is particularly common. Although surgery is the main treatment for this complication, it may be accompanied by postoperative complications. Therefore, it is particularly important to develop specific drugs for diabetic cataract, aiming to fundamentally reduce its incidence and reduce the need for surgery. At present, the greatest challenge is to develop therapeutic agents with multiple synergistic effects based on the complex pathogenesis of cataract. 1-Acetyl-5-phenyl-1 H-pyrrol-3-ylacetate (APPA) is designed based on the pathological mechanism as a potential drug to alleviate the occurrence of diabetic cataract. Our observations suggest that APPA is more effective than bendazaclysine in alleviating high galactose-induced oxidative stress (The malondialdehyde content in the APPA group and bendazaclysine group was significantly reduced to 0.45-fold and 0.58-fold compared to the high galactose-induced group, respectively.) and apoptosis (The apoptosis rate in the APPA group and bendazaclysine group was significantly reduced to 0.28-fold and 0.35-fold compared to the high galactose-induced group, respectively.) in lens epithelial cells by increasing antioxidant enzyme activity, and restoring mitochondrial homeostasis. Mechanistic studies have shown that APPA restoration of mitochondrial homeostasis is mediated through the SIRT1-PGC-1α pathway. In the galactose-induced cataract rat model, APPA is effective in alleviating the occurrence of galactose-induced cataract. In conclusion, APPA with multiple synergistic functions may be a potential drug to alleviate the occurrence of diabetic cataract, and it has a wider range of indications than benzydalysine.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-98079-9.

Keywords: Aldose reductase inhibitor, Diabetic cataract, Oxidative stress, Apoptosis, Mitochondrial homeostasis

Subject terms: Lens diseases, Apoptosis

Introduction

As a common chronic systemic disease, diabetes mellitus can cause significant changes in the structure of the eye. Among them, diabetic cataract is the most common of a series of eye complications caused by diabetes mellitus, which poses a serious threat to the visual health of patients1–4. At present, surgery is the main treatment for cataract. Although surgical treatment usually results in good results, complications may still occur, including posterior capsule rupture, postoperative inflammation, and intraocular lens dislocation5. Specific drugs for diabetic cataract will help to significantly reduce its incidence and reduce the need for subsequent surgery. Currently, the greatest challenge in the development of drugs to prevent or slow the progression of diabetic cataract is to find a multi-synergistic therapeutic drug based on the pathogenesis of diabetic cataract.

Apoptosis of lens epithelial cells (LECs) can be observed in patients with diabetic cataract, and the apoptosis-related protein B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL2)/BCL-2-associated X protein (BAX) is significantly reduced. In contrast, there is almost no apoptosis of LECs in normal eyes6,7. Therefore, apoptosis of LECs is closely related to the occurrence of diabetic cataract. Oxidative stress caused by high sugar environment is the main cause of apoptosis in LECs8,9. The oxidative stress induced by high sugar environment involves multiple mechanisms, such as the imbalance of polyol pathway caused by the excessive activation of aldose reductase (ALR2), the decrease of endogenous antioxidant enzyme activity and the imbalance of mitochondrial homeostasis2,10–15. Therefore, it can be speculated that a drug that also has the ability to inhibit ALR2, increase antioxidant enzyme activity, and regulate mitochondrial homeostasis may have a more effective ability to alleviate the occurrence of diabetic cataract16,17.

Aldehyde reductase (ALR1), which has higher homology with ALR2, is responsible for noxious aldehyde reduction generated in physiological metabolism. Thus, the low selectivity of ALR2 inhibitors is the main reason for the serious adverse consequences18. In our previous work, we designed and synthesized a compound chemically named 1-Acetyl-5-phenyl-1 H-pyrrol-3-ylacetate (APPA)19. APPA is highly stereoselective for ALR2, exhibits a significant ALR2 inhibitory effect, and is able to protect mesangial cells from high sugar environment. In addition, APPA could increase the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) and enhance the antioxidant capacity of Caenorhabditis elegans20. However, there have been limited studies on the effects of APPA on LECs stimulated by high sugar environment. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α) is closely associated with the regulation of mitochondrial homeostasis. PGC-1α can promote the expression of nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1) and mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), thereby enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis21. Additionally, PGC-1α regulates mitochondrial fission and fusion by modulating the phosphorylation level of dynamin-relatedprotein 1 (DRP-1) and the expression of mitofusin 2 (MFN2)22,23. As a result, the SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling pathway, which plays a critical role in regulating mitochondrial homeostasis, has garnered significant attention. Whether APPA regulates mitochondrial homeostasis through the SIRT1-PGC-1α pathway remains unknown.

In the present study, we investigated whether APPA could alleviate oxidative stress and apoptosis by increasing antioxidant enzyme activity and restoring mitochondrial homeostasis in LECs stimulated by high galactose. Furthermore, we tested whether APPA could regulate mitochondrial homeostasis through the SIRT1-PGC-1α pathway. Finally, we constructed a galactose‑induced cataract rat model to observe whether APPA eye drop treatment could effectively alleviate the development of galactose‑induced cataract.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human lens epithelial cell line SRA01/04 was purchased from the FuHeng Biology. SRA01/04 cells were cultured in H-DMEM medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin at 37℃ in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Biocompatibility of APPA

Cell viability assays were performed using CCK-8. SRA01/04 cells were seeded in 96-well plates. After 24 h, 25µM, 50µM, 100µM, and 200µM of APPA were added. After 72 h of incubation, CCK-8 reagent (Invigentech, product number IV08) was added to each well, and absorbance values were measured at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability assays were performed using CCK-8. SRA01/04 cells were seeded in 96-well plates. Mannitol group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM mannitol. Galactose group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM galactose. APPA group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 25µM, 50µM and 100µM APPA for 24 h, respectively, and then 150 mM galactose was added. After 72 h of incubation, CCK-8 reagent was added to each well, and absorbance values were measured at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Detection of cell apoptosis rate

Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (Solarbio, product number CA1020) was used to evaluate the exposure of phosphatidylserine on the cell surface and the damage of the plasma membrane. SRA01/04 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. Mannitol group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM mannitol. Galactose group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM galactose. APPA group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 50µM APPA for 24 h, followed by 150 mM galactose. Bendazaclysine group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 0.5 µmol/mL bendazaclysine (MCE, product number HY-B2165) for 24 h, followed by 150 mM galactose24. After 72 h of incubation, SRA01/04 cell suspensions from each group were washed with phosphate buffer (PBS) and resuspended in 0.5mL of precooled PBS. Then, Annexin V-FITC and PI were added according to the manufacturer’s instructions. FITC and PI fluorescence were determined immediately using flow cytometry. Populations of viable, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic cells were determined.

Detection of apoptosis-related protein expression

SRA01/04 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. SRA01/04 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. Mannitol group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM mannitol. Galactose group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM galactose. APPA group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 50µM APPA for 24 h, followed by 150 mM galactose. Bendazaclysine group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 0.5 µmol/mL bendazaclysine (MCE, product number HY-B2165) for 24 h, followed by 150 mM galactose. After 72 h of incubation, total proteins were extracted on ice using cell lysis buffer (Beyotime, product number P0013J) containing protease inhibitor (MCE, product number HY-K0010). Lysates extracted from cell lysis buffer were sonicated and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm. Proteins were separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, USA). PVDF membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk powder dissolved in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. PVDF membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with cleaved caspase 3, BAX, BCL2 and β-actin primary antibodies. Then, the cells were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (YEASEN, product number 36208ES60) was used for exposure to visualize the immunoreactive protein bands. Protein bands were analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH, USA, version 1.54j). Details of the antibodies used in this study are listed in Table S1.

Detection of intracellular reactive oxygen species

The detection of intracellular ROS was performed in accordance with previous research25. The production of ROS was measured using 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA, Solarbio, product number CA1410). SRA01/04 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. Mannitol group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM mannitol. Galactose group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM galactose. APPA group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 50µM APPA for 24 h, followed by 150 mM galactose. Bendazaclysine group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 0.5 µmol/mL bendazaclysine (MCE, product number HY-B2165) for 24 h, followed by 150 mM galactose. After 72 h of incubation, SRA01/04 cells were washed with PBS and incubated with 10 µM DCFH-DA for 30 min at 37 ° C. Subsequently, images were acquired by fluorescence microscopy.

Measurement of SOD and CAT activity, contents of MDA

SRA01/04 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. Mannitol group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM mannitol. Galactose group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM galactose. APPA group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 50µM APPA for 24 h, followed by 150 mM galactose. Bendazaclysine group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 0.5 µmol/mL bendazaclysine (MCE, product number HY-B2165) for 24 h, followed by 150 mM galactose. After 72 h of incubation, SRA01/04 cells were washed with phosphate buffer (PBS). Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, SOD and CAT activities were measured using MDA content assay kit (Solarbio, product number BC0025), SOD activity assay kit (Solarbio, product number BC5165) and CAT activity assay kit (Solarbio, product number BC0205).

Detection of antioxidant enzymes-related gene expression

The detection of gene expression was performed in accordance with previous research26–28. SRA01/04 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. Mannitol group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM mannitol. Galactose group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM galactose. APPA group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 50µM APPA for 24 h, followed by 150 mM galactose. Bendazaclysine group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 0.5 µmol/mL bendazaclysine (MCE, product number HY-B2165) for 24 h, followed by 150 mM galactose. Gene expression of Sod and Cat was assessed by qRT-PCR after 72 h of incubation. Total RNA was extracted from SRA 01/04 cells using a SPARKeasy Improved Tissue/Cell RNA Kit (Sparkjade, product number AC0202) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using a SPARKscript II All-in-one RT SuperMix Kit (Sparkjade, product number AG0305). cDNA quantification was performed by RT-qPCR using a 2×SYBR Green qPCR Mix Kit (Sparkjade, product number AH0104) and a CFX Connect system (Bio-Rad, America). Gapdh (Sangon Biotech, product number B661104) was used as a reference gene. The primers for Sod and Cat are listed in Table S2.

Staining of mitochondria

The staining of mitochondria was performed in accordance with previous research29. Mitochondria were detected using Mito-tracker green (Beyotime, product number C1048). SRA01/04 cells were seeded in 24-well plates. Mannitol group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM mannitol. Galactose group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM galactose. APPA group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 50µM APPA for 24 h, followed by 150 mM galactose. After 72 h of incubation, SRA 01/04 cells were washed once with PBS and then 500 µL of the dye mixture was added to each well in the dark, followed by 10 min of incubation in a cell culture incubator. After staining, the dye mixture was aspirated off and the cells were washed three times with PBS. After that, serum-free H-DMEM was added to each well. The stained cells were placed under a fluorescence microscope to observe mitochondrial morphology.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

MMP was determined by the lipophilic cation probe JC-1(Beyotime, product number C2005). SRA01/04 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. Mannitol group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM mannitol. Galactose group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM galactose. APPA group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 50µM APPA for 24 h, followed by 150 mM galactose. After 72 h of incubation, the medium was washed off with buffer, washed again with PBS, and then stained with JC-1 dye for 1 h. After JC-1 staining, fluorescence wavelengths emitted at 525 nm and 590 nm were detected under excitation light at 488 nm. Results were expressed as fluorescence values at 590 nm/525 nm.

Measurement of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)

SRA01/04 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. Mannitol group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM mannitol. Galactose group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM galactose. APPA group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 50µM APPA for 24 h, followed by 150 mM galactose. After 72 h of incubation, the ATP content was measured according to the instructions of the ATP Assay Kit (Beyotime, product number S0026).

Gene and protein expression assays related to mitochondrial homeostasis

SRA01/04 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. Mannitol group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM mannitol. Galactose group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM galactose. APPA group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 50µM APPA for 24 h, followed by 150 mM galactose. After 72 h of incubation, the gene and protein expression levels of DRP-1, p-DRP-1, MFN2, NRF1 and TFAM were measured according to the method of “Detection of apoptosis-related protein expression” and “Detection of antioxidant enzymes-related gene expression”. Details of the antibodies and primers used in this study are listed in Tables S1 and S2.

Regulation of the SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling pathway by APPA

SRA01/04 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. Mannitol group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM mannitol. Galactose group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM galactose. APPA group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 50µM APPA for 24 h, followed by 150 mM galactose. After 72 h of incubation, the gene and protein expression levels of SIRT1 and PGC-1α were measured according to the method of “Detection of apoptosis-related protein expression” and “Detection of antioxidant enzymes-related gene expression”. In addition, nuclear proteins were extracted from the cells of each group according to the instructions of nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction kit (Beyotime, product number P0027), and PGC-1α nuclear entry was detected according to the method of “Detection of apoptosis-related protein expression”. Details of the antibodies and primers used in this study are listed in Tables S1 and S2.

Effect of EX-527 on APPA function

SRA01/04 cells were seeded in 6-well plates. Galactose group: SRA01/04 cells were incubated with 150 mM galactose. Galactose + EX-527 group: SRA01/04 cells were first incubated with EX-527 (MCE, product number HY-15452) for 1 h, followed by the addition of 150 mM galactose. Galactose + APPA group: SRA01/04 cells were pretreated with 50µM for 24 h, followed by the addition of 150 mM galactose. Galactose + EX-527 + APPA: SRA01/04 cells were first incubated with EX-527 for 1 h, followed by the addition of 150 mM galactose. After 72 h of incubation, the protein expression levels of SIRT1, PGC-1α, cleaved caspase 3, BAX, BCL2, p-DRP-1, MFN2, NRF1, and TFAM were measured according to the method of “Detection of apoptosis-related protein expression”. Details of the antibodies used in this study are listed in Table S1.

Histopathological examination of ocular tissues

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Jilin University and performed in strict accordance with the “Guidelines for the Ethical Review of Laboratory Animal Welfare” (GB/T 35892 − 2018). All experiments complied with the ARRIVE. Wistar rats (6 weeks old, male, 180–220 g) were acclimatized for 1 week and randomly divided into five groups (n = 3 per group)0.1) Blank group. 2) PBS group: PBS was given by instillation three times daily. 3) 0.05% DMSO group: Prepare a 0.05% (v/v) DMSO solution using PBS. The 0.05% DMSO solution was given by instillation three times daily. 4) APPA50 group: 50µM APPA was given by instillation three times daily. 5) APPA25 group: 25µM APPA was given by instillation three times daily.

After 1 week, the rats were anesthetized and sacrificed. The euthanasia method for rats is based on reference to American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals (2020), involving injection of an overdose of sodium pentobarbital. The eyeballs were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 4-µm thick sections. HE staining was performed using a Leica Autostainer XL. After mounting the slides with neutral resin, images of the stained samples were captured by light microscopy.

Establishment of a galactose‑induced cataract model

Wistar rats (6 weeks old, male, 180–220 g) were acclimatized for 1 week and randomly divided into five groups (n = 9 per group). 1) Blank group. 2) Galactose group, rats were given 15 g/kg galactose twice daily by intraperitoneal injection for 4 weeks30. 3) Galactose + APPA50 group: rats were given 15 g/kg galactose twice daily by intraperitoneal injection for 4 weeks, while 50µM APPA was given by instillation three times daily. 4) Galactose + APPA25 groups: rats were similarly given 15 g/kg galactose twice daily by intraperitoneal injection for 4 weeks, while 25µM APPA was given by instillation three times daily. 5) Galactose + bendazaclysine group: rats were also given 15 g/kg galactose twice daily by intraperitoneal injection for 4 weeks, and 0.5% (w/v) bendazaclysine was given by instillation three times daily31.

Examination of the lens

Rats were dilated with 0.5% atropine and examined using a slit-lamp microscope. Lens images were captured using an accompanying imaging system and compared between experimental groups.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

After 4 weeks, the rats were anesthetized and sacrificed. The euthanasia method for rats is based on reference to American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals (2020), involving injection of an overdose of sodium pentobarbital. The preparation of the tissue slices was as previously described. The slices were dewaxed followed by antigen retrieval. Subsequently, the slices were immersed in a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution at room temperature for 25 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Then, the slices were incubated with 3% BSA for 30 min at room temperature to block nonspecific binding sites. Apply an appropriately diluted primary antibody (anti-BCL2 and anti-BAX) and incubate overnight at 4 °C. Add the secondary antibody (HRP-labeled) and incubate for 15 min at room temperature. Subsequently, fresh DAB staining solution was applied dropwise, and staining was monitored under a microscope until desired color development was achieved. The slices were then counterstained with harris hematoxylin for approximately 3 min. Perform gradient dehydration and transparency, and mount the slides with neutral resin. Images of the stained samples were captured by light microscopy. Details of the antibodies used in this study are listed in Table S1.

Extraction and expression of total protein from rat lens cells

After 4 weeks, the rats were anesthetized and sacrificed. The euthanasia method for rats is based on reference to American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals (2020), involving injection of an overdose of sodium pentobarbital. The eyeball was then removed under an operating microscope. After rinsing three times with PBS, the lens was stripped from the eyeball, the anterior capsule was torn off, placed in an EP tube, lysates containing protease inhibitors were added, centrifuged at 4 °C for 5 min, and the supernatant was collected.

The protein expressions of BCL2, BAX, DRP-1, p-DRP-1, MFN2, NRF1, TFAM, SIRT1 and PGC-1α were detected according to the method of “Detection of apoptosis-related protein expression”. Details of the antibodies used in this study are listed in Table S1.

Measurement of SOD and CAT activity, contents of MDA

Rat lens tissue homogenates were first prepared and detected according to the instructions of MDA content assay kit, SOD activity assay kit and CAT activity assay kit.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data were expressed as the mean ± SD from at least triplicate measurements. Differences between two comparative groups were assessed using the Student’s t-test, and the significance among multiple groups was examined by the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the LSD post hoc test (The data were normally distributed and demonstrated homogeneity of variance.). Significance was measured at the following thresholds: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Results

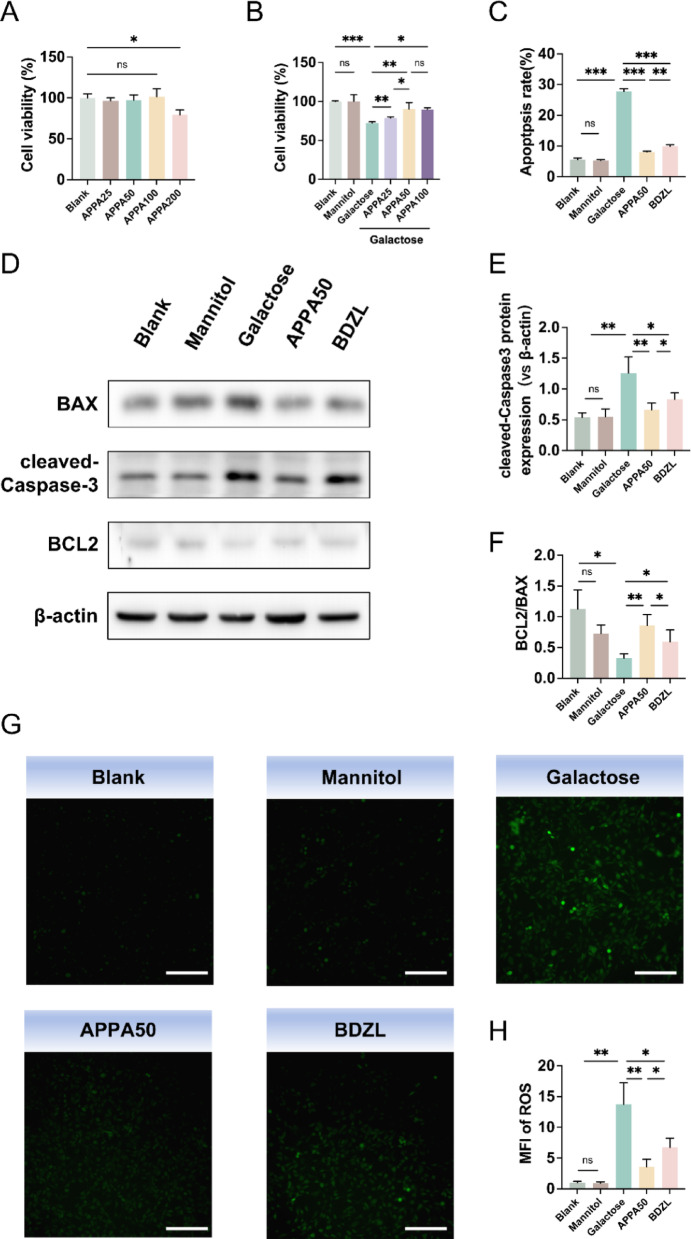

APPA inhibits galactose-induced cell apoptosis and reverses galactose-induced ROS reduction in SRA 01/04 cells

In the present study, we determined the effect of different concentrations of APPA on cell viability. As shown in Fig. 1A, APPA had no significant effect on cell viability at 25, 50, and 100µM concentrations compared to the blank group. However, at concentrations up to 200µM, APPA significantly inhibited cell activity. Next, we observed the effect of 25, 50, and 100µM APPA on cells stimulated with high concentrations of galactose. As shown in Fig. 1B, the high concentration galactose environment significantly inhibited cell activity, whereas APPA restored cell activity in a concentration dependent manner. Considering that there was no significant difference in effect between 50µM and 100µM APPA, 50µM APPA was selected for subsequent experiments. Flow cytometry results showed (Fig. 1C) that the galactose environment increased the apoptosis rate of the cells, while the same concentration of mannitol had no effect on the apoptosis rate, which ruled out the effect of osmotic pressure on the cells. APPA and bendazaclysine significantly attenuated the increase in apoptosis rate induced by galactose, with APPA being more effective than bendazaclysine. Based on the above results, we further examined the protein levels of cleaved caspase 3, BAX, and BCL2. As shown in Fig. 1D–F, the protein level of BCL2/BAX was significantly decreased, while the protein level of cleaved caspase 3 was significantly increased in the galactose group. However, there were no significant changes in the levels of these proteins in the mannitol group compared with the blank group. Compared with the galactose group, BCL2/BAX protein levels were significantly increased, while cleaved caspase 3 protein levels were significantly decreased after APPA and bendazaclysine pretreatment. APPA was more potent than bendazaclysine in its ability to regulate apoptosis-related proteins.

Fig. 1.

(A) The impact of different concentrations of APPA (25, 50, 100, and 200 µM) on the viability of lens epithelial cells. (B) The impact of different concentrations of APPA on the viability of lens epithelial cells in a galactose environment. (C) The apoptosis rate of lens epithelial cells. (D, E) Protein expression levels of BAX, cleaved caspase-3, and BCL2 in lens epithelial cells. (G, H) The content of ROS in lens epithelial cells, scale bar = 200 μm. Data were presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

In addition, intracellular ROS content was detected using DCFH-DA probe. DCFH-DA can freely pass through cell membranes. Once inside the cell, it is hydrolyzed by intracellular esterases to form DCFH, which cannot permeate the cell membrane, thereby trapping the probe within the cell. Intracellular ROS can oxidize the DCFH to produce 2’,7’-Dichlorofluorescein (DCF). By measuring the fluorescence intensity of DCF, the level of intracellular ROS can be determined. As shown in Fig. 1G,H, galactose increased intracellular ROS, whereas mannitol did not have this effect. APPA and bendazaclysine reversed the effect of galactose on intracellular ROS content, and the effect of APPA was more significant.

APPA restored cellular antioxidant capacity

MDA is an important indicator of oxidative stress, and its concentration reflects the ability of cells to resist oxidative stress. As shown in Fig. 2A, compared with the blank control group, MDA content in the cells was significantly increased in the galactose group, while there was no significant change in the mannitol group. Compared with the galactose group, the MDA content was significantly decreased after pretreatment with APPA and bendazaclysine, and the effect of APPA was better than that of bendazaclysine. CAT and SOD are two major antioxidant enzymes in cells, which are closely related to the ability of cells to resist oxidative stress. As shown in Fig. 2B,C, compared with the blank control group, CAT and SOD activities in the cells were significantly decreased in the galactose group, while there was no significant change in the mannitol group. Compared with galactose group, pretreatment with APPA significantly increased CAT and SOD activities, and bendazaclysine had no effect. Further, we examined Cat and Sod gene expression, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S1A,B, Cat and Sod gene expression was inhibited by galactose, and restored by pretreatment with APPA, and bendazaclysine had no effect.

Fig. 2.

(A) The content of MDA in lens epithelial cells. (B) The activity of CAT in lens epithelial cells. (C) The activity of SOD in lens epithelial cells. Data were presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

APPA reverses galactose-induced mitochondrial dysfunction

Mito-Tracker Green is a mitochondria-specific fluorescent probe. After entering the cell, Mito-Tracker Green binds specifically to mitochondria and emits green fluorescence, allowing for the direct visualization of mitochondrial morphology. The mitochondrial dye Mito-tracker Green staining results (Fig. 3A) showed that mitochondria exhibited a normal tubular structure in the blank and mannitol groups. However, in the galactose group, mitochondria presented a fragmented morphology. In the pretreatment group, APPA inhibited the occurrence of mitochondrial fragmentation. To further elucidate the mitochondrial oxidative stress response induced by galactose, mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was measured. The increase in green fluorescence in MMP results indicates a decrease in membrane potential. As shown in Fig. 3B,C, galactose increased MMP compared with blank control and mannitol group. In the pretreatment group, APPA inhibited this effect. Finally, the ATP yield assay (Fig. 3D) showed a significant decrease in the galactose group compared with the blank and mannitol groups. However, ATP production in the APPA group was significantly restored.

Fig. 3.

(A) The morphology of mitochondria in lens epithelial cells. (B, C) The level of mitochondrial membrane potential in lens epithelial cells, scale bar = 100 μm. (D) The content of ATP in lens epithelial cells. (E–I) Protein expression levels of MFN2, DRP1, p-DRP1, NRF1 and TFAM in lens epithelial cells. Data were presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Mitochondrial structural damage and oxidative stress are often accompanied by imbalances in mitochondrial homeostasis, including mitochondrial fusion, fission, and biosynthesis. In this study, we examined MFN2, a protein associated with mitochondrial fusion, DRP1, a protein associated with mitochondrial division, and NRF1 and TFAM, proteins associated with mitochondrial biosynthesis. As shown in Fig. 3E–I, the expression of MFN2 and p-DRP1 did not change in the mannitol group compared with the blank group. However, in the galactose group, MFN2 expression was decreased while p-DRP1 expression was increased, suggesting that galactose can inhibit mitochondrial fusion and promote mitochondrial fission. After APPA pretreatment, MFN2 expression was increased while p-DRP1 expression was decreased compared with the galactose group. Mitochondrial biosynthesis is an important way to replenish damaged mitochondria. The results showed that NRF1 and TFAM expression did not change significantly in the mannitol group compared to the blank control group, but decreased significantly in the galactose group, indicating that high concentrations of galactose inhibited mitochondrial biosynthesis. After APPA pretreatment, NRF1 and TFAM expression was significantly increased compared with the galactose group. In addition, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2A–C, Mfn2, Nrf1 and Tfam gene expression changes were consistent with protein level changes.

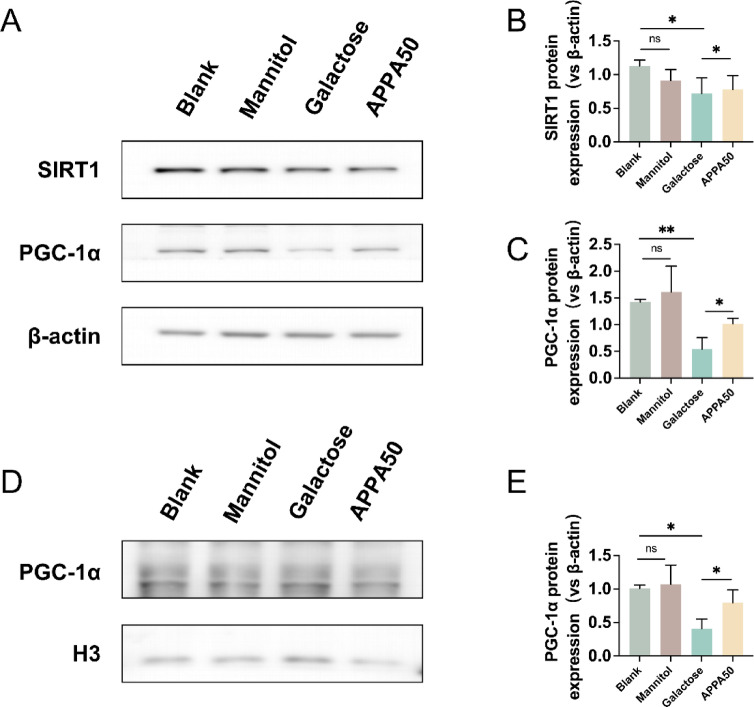

APPA regulates mitochondrial homeostasis through the SIRT1-PGC-1α pathway

To investigate whether APPA restores high galactose-induced mitochondrial dysfunction by modulating the SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling pathway, we examined the levels of SIRT1 and PGC-1α. As shown in Fig. 4A–C, compared with the blank group, mannitol had no significant effect on SIRT1 and PGC-1α, while the protein expression levels of SIRT1 and PGC-1α were significantly decreased in the galactose group, indicating that the high galactose environment inhibited the SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling pathway. Compared with the galactose group, the protein expression levels of SIRT1 and PGC-1α were restored after APPA pretreatment. In addition, we evaluated the nuclear translocation of PGC-1α. As shown in Fig. 4D,E, high concentrations of galactose significantly inhibited PGC-1α nuclear translocation, but pretreatment with APPA was able to reverse this effect.

Fig. 4.

(A–C) Protein expression levels of SIRT1 and PGC-1α in lens epithelial cells. (D, E) The expression level of PGC-1α protein in the nucleus of lens epithelial cells. Data were presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

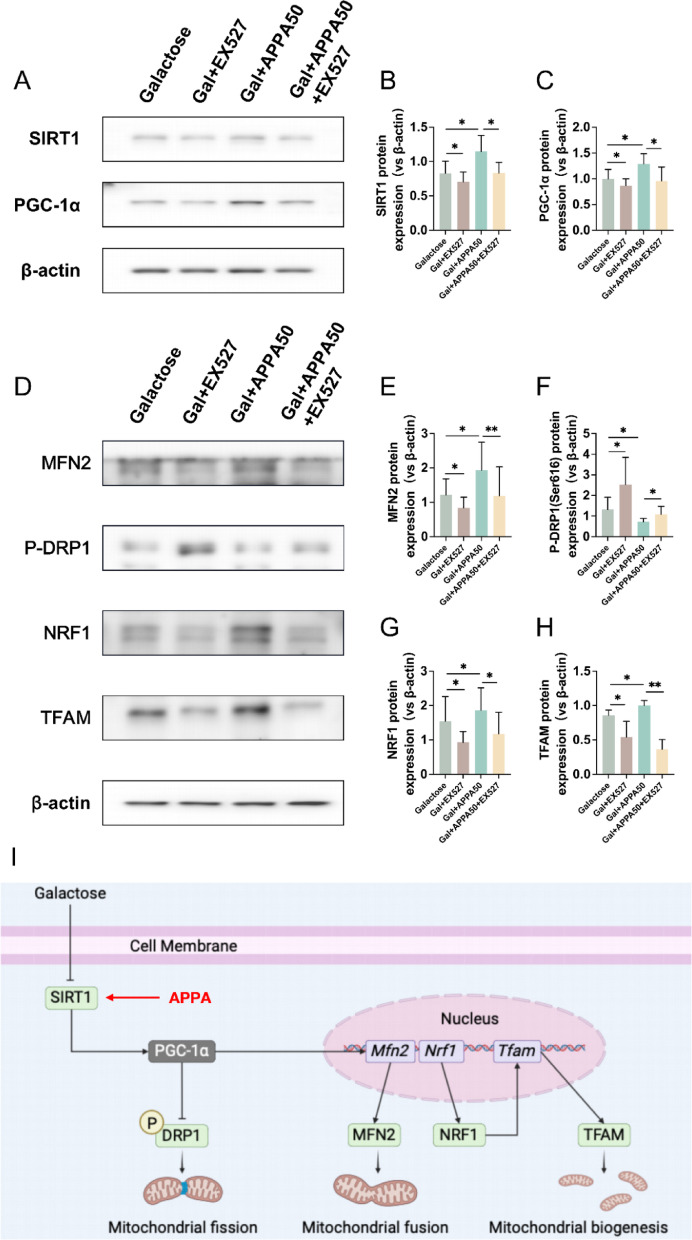

Next, we proceeded to observe the effect of APPA on mitochondrial homeostasis in response to galactose stimulation using the SIRT1 inhibitor EX-527 to determine whether SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling is critical for APPA regulation of mitochondrial homeostasis. As shown in Fig. 5A–C, EX-527 was able to inhibit the ability of APPA to activate the SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling pathway in a high galactose environment. In mitochondrial fusion, division, and biogenesis. As shown in Fig. 5D–H, the expression of the mitochondrial fission related proteins p-DRP1 increased and the mitochondrial fusion related protein MFN2 decreased after addition of EX-527 compared with APPA pretreatment alone. In addition, the expression of NRF1 and TFAM, proteins related to mitochondrial synthesis, was also reduced, suggesting that inhibition of SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling affects APPA regulation of mitochondrial homeostasis.

Fig. 5.

(A–C) Protein expression levels of SIRT1 and PGC-1α in lens epithelial cells. (D–H) Protein expression levels of MFN2, p-DRP1, NRF1 and TFAM in lens epithelial cells. (I) APPA regulates mitochondrial homeostasis through the SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling pathway (Created in BioRender). Data were presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

In addition, we examined the effect of APPA on apoptosis using the SIRT1 inhibitor EX-527 to determine whether APPA reduced apoptosis by restoring mitochondrial homeostasis. As shown in Fig. 6A–C, the BCL2/BAX ratio was decreased and cleaved caspase 3 expression was increased after the addition of EX-527 compared with the group pretreated with APPA alone, suggesting that the regulation of mitochondrial homeostasis by APPA is critical in influencing apoptosis.

Fig. 6.

(A–C) Protein expression levels of BAX, cleaved caspase-3 and BCL2 in lens epithelial cells. Data were presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Animal experiments

First, we confirmed the safety of DMSO and APPA as eye drops. The results of HE staining were shown in Supplementary Fig. S3, and no structural damage was observed in the cornea and conjunctiva in each group.

We subjected the rats to routine mydriasis treatment and observed the dynamic changes in lens opacity under a slit lamp, while the lenses of each group were photographed at week 8. As shown in Fig. 7A, the lenses of rats in the blank control group remained transparent, while the lenses of rats in the galactose group became cloudy. In the treatment group, the rats showed a significant reduction in lens opacity compared with the galactose group, and the effect of APPA was superior to that of bendazaclysine, which is consistent with the results of the cell experiments.

Fig. 7.

(A) Opacity of rat lenses. (B) Immunohistochemical staining of rat lens epithelial cells, scale bar = 50 μm. (C) The content of MDA in rat lenses (D, E) The activity of CAT and SOD in rat lenses. (F–H) Protein expression levels of BAX, cleaved caspase-3 and BCL2 in rat lenses. Data were presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

The results of IHC were shown in Fig. 7B. For the expression of BCL2 protein, compared with healthy rats, the lens epithelial cells of rats with sugar cataract exhibited decreased BCL2 protein expression. After treatment with APPA and bendazaclysine, the expression of BCL2 protein increased, with APPA demonstrating superior efficacy compared to bendazaclysine. For the expression of BAX protein, compared with healthy rats, the lens epithelial cells of rats with sugar cataract show increased BAX protein expression. After treatment with APPA and bendazaclysine, the expression of BAX protein decreased. APPA demonstrated superior efficacy compared to the bendazaclysine.

The MDA content in the lenses of each group is shown in Fig. 7C, and it was significantly higher in the galactose group than in the blank control group. Compared with the galactose group, the MDA content was significantly reduced after APPA and bendazaclysine eye drops, and the effect of APPA was better than that of bendazaclysine. Antioxidant enzyme activities in the lens are shown in Fig. 7D,E, CAT and SOD activities in the lens were significantly reduced in the galactose group compared with the blank control group. Compared with galactose group, APPA significantly increased CAT and SOD activities after eye drops, and bendazaclysine had no effect.

The expression levels of apoptosis-related proteins in lens epithelial cells of each group are shown in Fig. 7F–H. Compared with the blank control group, the BCL2/BAX ratio in the galactose group was significantly decreased, while the expression of cleaved caspase 3 protein was significantly increased. Compared with galactose group, both APPA and bendazaclysine treatment reduced the expression of apoptosis-related proteins, increased the BCL2/BAX ratio, and decreased the expression of cleaved caspase 3 protein in lens epithelial cells. Among them, APPA was more effective than bendazaclysine, and APPA50 was more effective than APPA25.

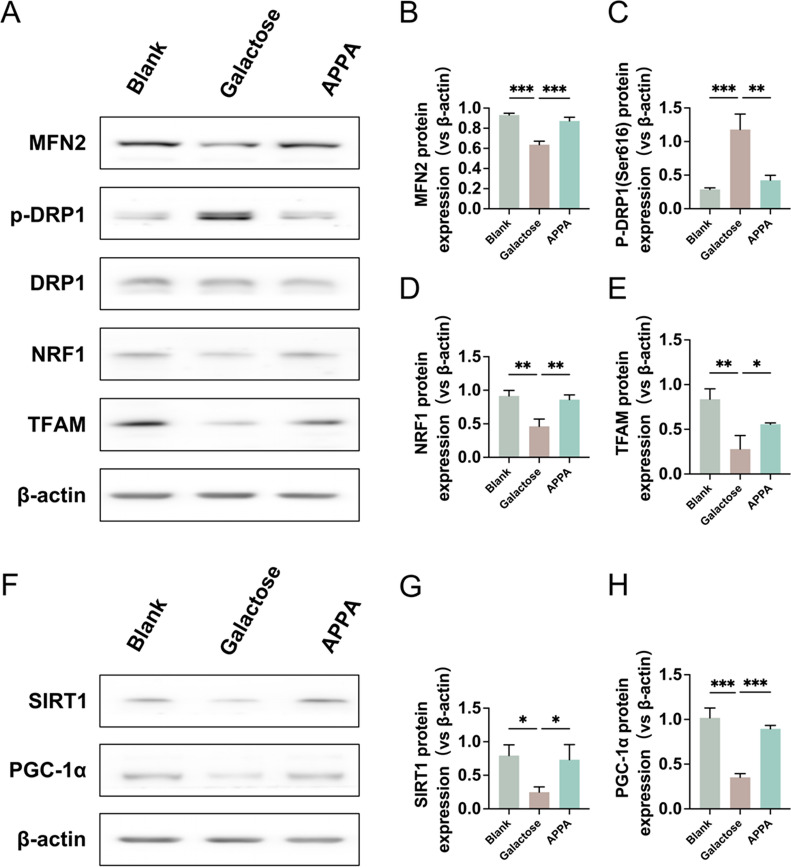

The expression results of mitochondrial homeostasis related proteins in lens epithelial cells of each group were shown in Fig. 8A–E. Compared with the blank control group, the expression of mitochondrial fission related protein p-DRP1 was significantly increased, while the expression of mitochondrial fusion related protein MFN2 was significantly decreased in the galactose group. In addition, the expression of mitochondrial biosynthesis related proteins NRF1 and TFAM was also significantly reduced. Compared with the galactose group, APPA treatment significantly restored the expression of mitochondrial homeostasis related proteins, as indicated by a significant reduction in the expression of p-DRP1 and an increase in the expression of MFN2, NRF1 and TFAM. In the regulation of mitochondrial homeostasis related pathway SIRT1-PGC-1α, as shown in Fig. 8F–H, the SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling pathway was inhibited in the galactose group compared with the blank control group, while APPA was able to restore the inhibited SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling pathway.

Fig. 8.

(A–E) Protein expression levels of MFN2, DRP1, p-DRP1, NRF1 and TFAM in rat lens epithelial cells. (F–H) Protein expression levels of SIRT and PGC-1α in rat lens epithelial cells. Data were presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Finally, the HE staining results of important organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney) of rats in each group are shown in Supplementary Figure S4. Compared with the control group, there were no significant histomorphological changes in the important organs of the other groups, indicating that APPA had good biological safety.

Discussion

With the acceleration of global aging, cataract has become one of the leading causes of visual impairment around the world32,33. As one of the main types of cataract, diabetic cataract is also one of the earliest eye complications in diabetic patients, which can lead to severe vision loss or even blindness34,35. As the number of diabetic patients continues to increase worldwide, the incidence of diabetic cataract is also on the rise1. At present, surgery is still the main method for the treatment of various cataracts, but there are also many risks of complications. Therefore, it is important to find a strategy that can delay the onset of diabetic cataract, because it can not only reduce the risk of surgical complications, but also reduce the associated medical costs.

Recent studies have shown that SIRT1 is closely related to diabetic cataract. Activated SIRT1 can improve transcription efficiency of PGC-1α36–39. PGC-1α is a key factor in nucleus-mitochondrial regulation, which regulates mitochondrial homeostasis, including fusion, fission and synthesis40–42. Mitochondria are dynamic organelles closely involved in the regulation of various cellular functions, ROS production and apoptosis22,43,44. Therefore, restoring mitochondrial homeostasis by regulating SIRT1-PGC-1α was hypothesized to be a promising approach for the treatment of diabetic cataract. In this study, we found that high concentration of galactose could inhibit the protein expression of SIRT1 and PGC-1α in LECs, resulting in the inhibition of mitochondrial fusion-related genes and proteins, the increase of mitochondrial fission related genes and proteins, and the decrease of mitochondrial genesis related genes and proteins. Disruption of any of the processes of mitochondrial fusion, fission, and synthesis can cause severe mitochondrial dysfunction45. In the mannitol group, these changes did not occur, which ruled out an effect of osmotic pressure on the cells and proved that the changes in the SIRT1-PGC-1α pathway were caused by high galactose and not osmotic pressure. We found that APPA was able to restore mitochondrial homeostasis caused by high galactose. To further determine the regulatory mechanism of APPA, we used SIRT1 inhibitor EX527 and found that the regulatory effect of APPA on mitochondria was attenuated, thus proving that APPA regulates mitochondrial homeostasis via SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling pathway (Fig. 5I).

Mitochondrial homeostasis is closely related to apoptosis. Studies have shown that the fragmentation of mitochondria is closely related to the increase of ROS production, which causes cell apoptosis in high sugar environment in vitro12,22,46. In the present study, high concentration of galactose increased oxidative stress indicators, decreased mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP content in LECs, and then promoted the occurrence of apoptosis. In high galactose environment, APPA supplementation reduced mitochondrial damage and apoptosis induced by high concentration of galactose, while SIRT1 inhibitor EX527 reversed the protective effect of APPA on LECs. Thus, APPA reduced the occurrence of apoptosis in LECs by restoring mitochondrial homeostasis.

ALR2 activation in the polyol pathway is an important factor in high sugar-induced apoptosis43,47. Activation of ALR2 can lead to NADPH depletion, which disturbs the cellular redox balance and leads to the formation of oxidative stress48. Therefore, inhibition of ALR2 can ameliorate oxidative stress and apoptosis in high sugar environment, and delay the occurrence of diabetic cataract49,50. Our previous study have demonstrated that APPA could inhibit ALR2 activity19. In the present study, pretreatment with APPA and bendazaclysine reduced oxidative stress and apoptosis induced by high galactose, which may be due to the disruption of polyol pathway caused by blocking ALR2 activation. In high sugar environment, not only is an excess of ROS produced, but endogenous antioxidant mechanisms are also inhibited51–53. This disruption of the balance between ROS production and scavenging can lead to increased oxidative stress54. Fortunately, in this study, APPA was found to be able to enhance CAT and SOD gene expression and activity in LECs in a high galactose environment. This result is similar to our previous study, in which APPA reduced mitochondrial ROS accumulation by increasing CAT and SOD activity and enhanced stress resistance in Caenorhabditis elegans20. As expected, bendazaclysine did not increase CAT and SOD gene expression and activity, and the results were similar to those in previous studies55. These data suggest that APPA may have a better effect than bendazaclysine on ameliorating the oxidative stress state and apoptosis of LECs in a high galactose environment.

Apoptosis of lens epithelial cells is one of the main factors in the development of diabetic cataract56. In vitro cell experiments demonstrated that APPA could inhibit high galactose induced apoptosis in LECs, which might be achieved through the synergistic action of the following three pathways: (1) acting as an ALR2 inhibitor, APPA inhibited ALR2 activity, restored the imbalance of polyol pathway, and reduced oxidative stress. (2) APPA enhanced the ability of lens epithelial cells to resist oxidative stress by increasing the endogenous antioxidant enzyme activities of SOD and CAT. (3) APPA restored mitochondrial homeostasis and reduced oxidative stress through SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling pathway. Therefore, the preventive or therapeutic efficacy of APPA is expected to be superior to that of conventional single ALR2 inhibitors. This hypothesis was tested in a rat model of galactose‑induced cataract. The absence of significant ocular toxicity of APPA was preliminarily verified by HE. APPA was more effective in reducing lens opacity in rats than bendazaclysine by eye drop treatment. Further studies showed that APPA could increase the activities of CAT and SOD in rat LECs, as well as reduce oxidative stress injury and apoptosis. At the same time, APPA was able to restore mitochondrial homeostasis in rat LECs.

Taken together, our study confirmed that APPA is not only an ALR2 inhibitor but also a potent regulator of the SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling pathway. In vitro and in vivo experiments, compared to bendazaclysine, APPA was more effective in alleviating high galactose-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in LECs. Furthermore, APPA effectively mitigated the development of galactose-induced cataracts, showcasing its potential as a therapeutic agent. The performance of APPA can be attributed to its multifunctional mechanisms. Unlike bendazaclysine, which primarily acted as an ALR2 inhibitor, APPA not only inhibited ALR2 activity but also enhanced the activity of antioxidant enzymes and restored mitochondrial homeostasis. Through the synergistic effects of multiple functions, APPA effectively alleviates high galactose-induced oxidative stress in LECs, thereby reducing the occurrence of apoptosis. As a result, APPA demonstrates significantly superior efficacy compared to bendazaclysine. Our data highlight that the synergistic effects of drugs have great potential for the prevention and treatment of diabetic cataract.

Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrated that APPA was effective in delaying the development of galactose‑induced cataract. In vitro experiments demonstrated that APPA could improve antioxidant enzyme activities and restore mitochondrial homeostasis, thereby reducing apoptosis in LECs under high galactose conditions. Furthermore, we verified that APPA restored mitochondrial homeostasis through SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling pathway. In addition, the delaying effect of APPA on galactose‑induced cataract was also validated in a rat model. Our data suggest that APPA may be a potential drug to delay the development of diabetic cataract. In the next phase of our research, we will conduct a comprehensive safety assessment of APPA, including pharmacokinetics, toxicokinetics, genotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and hemolytic toxicity. These studies will provide critical data to support the transition to clinical trials.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Xi Wang contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, wrote and edited the manuscript; Zhuoya Li, Ying Xing, Yaru Wang, Shiyao Wang and Liping Wang contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and critically reviewed the manuscript; Hui Zhang contributed to conception, design, edited the manuscript and supervised the study. All authors gave final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ang, M. J. & Afshari, N. A. Cataract and systemic disease: A review. Clin. Experimental Ophthalmol.49, 118–127. 10.1111/ceo.13892 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tokali, F. S., Demir, Y., Turkes, C., Dincer, B. & Beydemir, S. Novel acetic acid derivatives containing quinazolin-4(3H)-one ring: synthesis, in vitro, and in Silico evaluation of potent aldose reductase inhibitors. Drug Dev. Res.84, 275–295. 10.1002/ddr.22031 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demir, Y. et al. Synthesis and characterization of novel acyl hydrazones derived from Vanillin as potential aldose reductase inhibitors. Mol. Diversity. 27, 1713–1733. 10.1007/s11030-022-10526-1 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korkusuz, E. et al. Synthesis and biological studies of pyrimidine derivatives targeting metabolic enzymes. Arch. Pharm.35710.1002/ardp.202300634 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Hong, A. R., Sheybani, A. & Huang, A. J. W. Intraoperative management of posterior capsular rupture. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol.26, 16–21. 10.1097/icu.0000000000000113 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang, Y. et al. Orai3 exacerbates apoptosis of lens epithelial cells by disrupting Ca2+ homeostasis in diabetic cataract. Clin. Transl. Med.1110.1002/ctm2.327 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Kim, B., Kim, S. Y. & Chung, S. K. Changes in apoptosis factors in lens epithelial cells of cataract patients with diabetes mellitus. J. Cataract Refract. Surg.38, 1376–1381. 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.04.026 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu, S. et al. Protection of human lens epithelial cells from oxidative stress damage and cell apoptosis by KGF-2 through the Akt/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Long.202210.1155/2022/6933812 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Hu, X., Liang, Y., Zhao, B. & Wang, Y. Oxyresveratrol protects human lens epithelial cells against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis by activation of Akt/HO-1 pathway. J. Pharmacol. Sci.139, 166–173. 10.1016/j.jphs.2019.01.003 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thakur, S., Gupta, S. K., Ali, V., Singh, P. & Verma, M. Aldose reductase: a cause and a potential target for the treatment of diabetic complications. Arch. Pharm. Res.44, 655–667. 10.1007/s12272-021-01343-5 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ighodaro, O. M. Molecular pathways associated with oxidative stress in diabetes mellitus. Biomed. Pharmacother.108, 656–662. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.09.058 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu, T., Sheu, S. S., Robotham, J. L. & Yoon, Y. Mitochondrial fission mediates high glucose-induced cell death through elevated production of reactive oxygen species. Cardiovasc. Res.79, 341–351. 10.1093/cvr/cvn104 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, Z. et al. Efficiency co-delivery of ellagic acid and oxygen by a non-invasive liposome for ameliorating diabetic retinopathy. Int. J. Pharm.64110.1016/j.ijpharm.2023.122987 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Chen, Y. Y. et al. Attenuation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition via SGLT2 Inhibition and diabetic cataract suppression by Dapagliflozin nanoparticles treatment. Life Sci.33010.1016/j.lfs.2023.122005 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Gulec, O. et al. Novel spiroindoline derivatives targeting aldose reductase against diabetic complications: bioactivity, cytotoxicity, and molecular modeling studies. Bioorg. Chem.14510.1016/j.bioorg.2024.107221 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Demir, Y., Ceylan, H., Turkes, C. & Beydemir, S. Molecular Docking and Inhibition studies of vulpinic, carnosic and Usnic acids on polyol pathway enzymes. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn.40, 12008–12021. 10.1080/07391102.2021.1967195 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demir, Y. & Koksal, Z. Some sulfonamides as aldose reductase inhibitors: therapeutic approach in diabetes. Arch. Physiol. Biochem.128, 979–984. 10.1080/13813455.2020.1742166 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muthenna, P., Suryanarayana, P., Gunda, S. K., Petrash, J. M. & Reddy, G. B. Inhibition of aldose reductase by dietary antioxidant Curcumin: mechanism of Inhibition, specificity and significance. FEBS Lett.583, 3637–3642. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.042 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiu, Z. M., Wang, L. P., Fu, J., Xu, J. & Liu, L. 1-Acetyl-5-phenyl-1H-pyrrol-3-ylacetate: an aldose reductase inhibitor for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.27, 4482–4487. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.08.002 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang, S., Lin, D., Cao, J. & Wang, L. A. P. P. A. Increases lifespan and stress resistance via lipid metabolism and Insulin/IGF-1 signal pathway in caenorhabditis elegans. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2410.3390/ijms241813682 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Chen, L. et al. PGC-1α-Mediated mitochondrial quality control: molecular mechanisms and implications for heart failure. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol.1010.3389/fcell.2022.871357 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Ding, M. et al. Melatonin prevents Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission in diabetic hearts through SIRT1-PGC1α pathway. J. Pineal. Res.6510.1111/jpi.12491 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Hu, L. et al. Nicotinamide riboside promotes Mfn2-mediated mitochondrial fusion in diabetic hearts through the SIRT1-PGC1α-PPARα pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med.183, 75–88. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.03.012 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu, Z. et al. Ginkgo Biloba extract prevents against apoptosis induced by high glucose in human lens epithelial cells. Acta Pharmacol. Sin.29, 1042–1050. 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00837.x (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao, D. et al. Peroxiredoxin 6 maintains mitochondrial homeostasis and promotes tumor progression through ROS/JNK/p38 MAPK signaling pathway in multiple myeloma. Sci. Rep.1510.1038/s41598-024-84021-y (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Karagac, M. S. et al. Esculetin improves inflammation of the kidney via gene expression against doxorubicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats: in vivo and in silico studies. Food Biosci.6210.1016/j.fbio.2024.105159 (2024).

- 27.Kizir, D. et al. The protective effects of esculetin against doxorubicin-Induced hepatotoxicity in rats: insights into the modulation of caspase, FOXOs, and heat shock protein pathways. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol.3810.1002/jbt.23861 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Özturk, N., Ceylan, H. & Demir, Y. The hepatoprotective potential of Tannic acid against doxorubicin-induced hepatotoxicity: insights into its antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, and antiapoptotic mechanisms. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol.3810.1002/jbt.23798 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Lin, H. et al. Cyclopiazonic acid suppresses the function of leydig cells in prepubertal male rats by disrupting mitofusin 1-mediated mitochondrial function. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.28910.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.117503 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Zhong, L. et al. Characterization of an I.p. D-galactose-induced cataract model in rats. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods10710.1016/j.vascn.2020.106891 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Balfour, J. A. & Clissold, S. P. Bendazac lysine. A review of its Pharmacological properties and therapeutic potential in the management of cataracts. Drugs39, 575–596. 10.2165/00003495-199039040-00007 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flaxman, S. R. et al. Global causes of blindness and distance vision impairment 1990–2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Global Health. 5, E1221–E1234. 10.1016/s2214-109x(17)30393-5 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, X. et al. Association between systemic immune inflammation index and cataract incidence from 2005 to 2008. Sci. Rep.1510.1038/s41598-024-84204-7 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Altintop, M. D. et al. A new series of hydrazones as small-molecule aldose reductase inhibitors. Arch. Pharm.35610.1002/ardp.202200570 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Akdag, M., Ozcelik, A. B., Demir, Y. & Beydemir, S. Design, synthesis, and aldose reductase inhibitory effect of some novel carboxylic acid derivatives bearing 2-substituted-6-aryloxo- pyridazinone moiety. J. Mol. Struct.125810.1016/j.molstruc.2022.132675 (2022).

- 36.Rahman, S. & Islam, R. Mammalian Sirt1: insights on its biological functions. Cell. Commun. Signal.910.1186/1478-811x-9-11 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Yu, H. et al. LARP7 protects against heart failure by enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis. Circulation143, 2007–2022. 10.1161/circulationaha.120.050812 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao, Y. et al. JiangyaTongluo Decoction ameliorates tubulointerstitial fibrosis via regulating the SIRT1/PGC-1α/mitophagy axis in hypertensive nephropathy. Front. Pharmacol.1510.3389/fphar.2024.1491315 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Wu, S., Wang, L., Wang, F. & Zhang, J. Resveratrol improved mitochondrial biogenesis by activating SIRT1/PGC-1α signal pathway in SAP. Sci. Rep.1410.1038/s41598-024-76825-9 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Halling, J. F. & Pilegaard, H. PGC-1α-mediated regulation of mitochondrial function and physiological implications. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metabolism. 45, 927–936. 10.1139/apnm-2020-0005 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, H. et al. PGC-1 alpha regulates mitochondrial biogenesis to ameliorate hypoxia-inhibited cementoblast mineralization. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.1516, 300–311. 10.1111/nyas.14872 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu, F. et al. α-Arbutin ameliorates UVA-induced Photoaging through regulation of the SIRT3/PGC-1α pathway. Front. Pharmacol.1510.3389/fphar.2024.1413530 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Abate, M. et al. Mitochondria as playmakers of apoptosis, autophagy and senescence. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol.98, 139–153. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2019.05.022 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang, H. et al. Construction of mitochondrial-targeting nano-prodrug for enhanced Rhein delivery and treatment for osteoarthritis in vitro. Int. J. Pharm.66110.1016/j.ijpharm.2024.124397 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Kageyama, Y. et al. Mitochondrial division ensures the survival of postmitotic neurons by suppressing oxidative damage. J. Cell Biol.197, 535–551. 10.1083/jcb.201110034 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu, T. Z., Robotham, J. L. & Yoon, Y. Increased production of reactive oxygen species in hyperglycemic conditions requires dynamic change of mitochondrial morphology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.103, 2653–2658. 10.1073/pnas.0511154103 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allen, D. A., Yaqoob, M. M. & Harwood, S. M. Mechanisms of high glucose-induced apoptosis and its relationship to diabetic complications. J. Nutr. Biochem.16, 705–713. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.06.007 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chung, S. S. M., Ho, E. C. M., Lam, K. S. L. & Chung, S. K. Contribution of polyol pathway to diabetes-induced oxidative stress. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.14, S233–S236. 10.1097/01.Asn.0000077408.15865.06 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tokali, F. S. et al. Synthesis, biological evaluation, and in Silico study of novel library sulfonates containing quinazolin-4(3H)-one derivatives as potential aldose reductase inhibitors. Drug Dev. Res.83, 586–604. 10.1002/ddr.21887 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sever, B. et al. Identification of a new class of potent aldose reductase inhibitors: design, microwave-assisted synthesis, in vitro and in Silico evaluation of 2-pyrazolines. Chemico Biol. Interact.34510.1016/j.cbi.2021.109576 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Yang, C. et al. Phillyrin alleviates high glucose-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in HBZY-1 cells through Inhibition of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. J. Pharm. Pharmacol.76, 776–787. 10.1093/jpp/rgae028 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Asdaq, S. M. B. et al. Antidiabetic and antioxidant potential of Crocin in high-fat diet plus streptozotocin-induced type-2 diabetic rats. Int. J. ImmunoPathol. Pharmacol.3810.1177/03946320231220178 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Sharan, L., Pal, A., Babu, S. S., Kumar, A. & Banerjee, S. Bay 11-7082 mitigates oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction via NLRP3 inhibition in experimental diabetic neuropathy. Life Sci.35910.1016/j.lfs.2024.123203 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Jomova, K. et al. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: chronic diseases and aging. Arch. Toxicol.97, 2499–2574. 10.1007/s00204-023-03562-9 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sheng, N. et al. Scutellarin rescued mitochondrial damage through ameliorating mitochondrial glucose oxidation via the Pdk-Pdc axis. Adv. Sci.1010.1002/advs.202303584 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Tao, D. et al. CircPAG1 interacts with miR-211-5p to promote the E2F3 expression and inhibit the high glucose-induced cell apoptosis and oxidative stress in diabetic cataract. Cell. Cycle. 21, 708–719. 10.1080/15384101.2021.2018213 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.