Abstract

We report here a method for making polyesterether from ethylene glycol. The reaction is catalyzed by a ruthenium complex and liberates H2 gas and H2O as byproducts. Mechanistic studies conducted through experiments and DFT computations suggest that the chain growth of the polymerization process involves both dehydrogenation and dehydration pathways stemming from a hemiacetal intermediate, leading to the formation of esters and ethers, respectively. Investigations into the polymerization of other diols have also been conducted, showing that diols with a lower number of carbons between the alcohol groups (propylene glycol, glycerol, and 1,3-propanediol) lead to the formation of polyesterether whereas α,ω-diols containing a higher number of carbons (1,6-hexanediol and 1,10-decanediol) lead to the formation of polyester.

Keywords: polyesterether, dehydrogenation, ethylene glycol, hydrogen-borrowing, ruthenium

Short abstract

We report here a method for making polyesterethers directly from ethylene glycol, forming water and H2 gas as the only byproducts.

Introduction

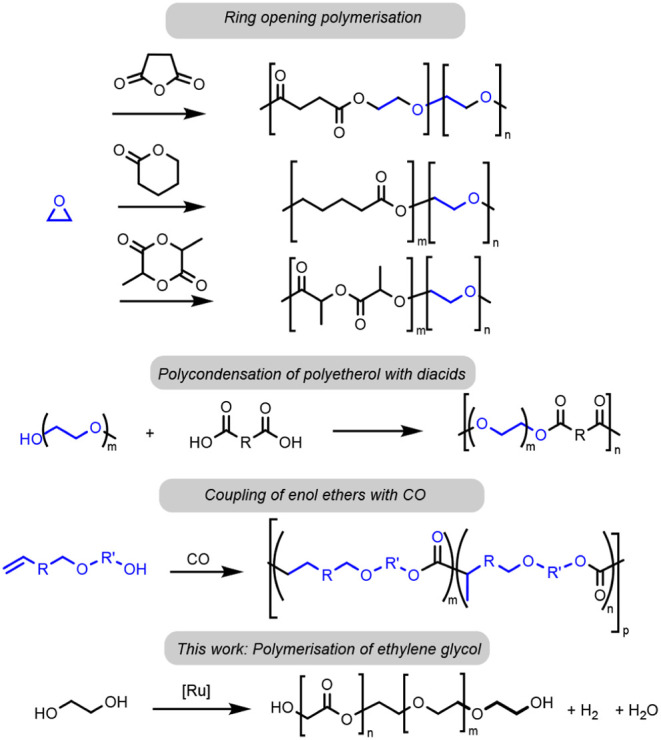

Aliphatic copolyesterethers have attracted significant interest recently due to their excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability and applications in areas such as tissue engineering and packaging.1,2 The conventional methods for their synthesis involve ring-opening polymerization of epoxides with lactones,3,4 lactides,5−8 or anhydrides (Figure 1).9,10 However, these methods often involve multiple steps of polymerization and purification, which make their large-scale application challenging. A few other methods based on melt polymerization of polyethylene glycol with diacids or diesters,11,12 hydroesterificative polymerization (coupling of enol ethers with CO),13 and reduction of polyesters14 have also been reported in the past (Figure 1). Most of these processes involve monomers that require multiple steps to be synthesized and are derived from fossil fuels. As such, there is a need to develop new methods for the synthesis of aliphatic copolyesterethers from renewable, inexpensive, and commercially available feedstock.

Figure 1.

Known methods for the synthesis of polyesterethers and the method disclosed herein.

Catalytic dehydrogenation is an atom-economic approach for the synthesis of organic compounds, especially those containing carbonyl compounds such as aldehydes, ketones, esters, and amides.15 The concept of acceptorless dehydrogenative catalysis has also been utilized for the synthesis of various polymers.15 For example, Milstein16 reported the synthesis of polyamides from the dehydrogenative coupling of diols and diamines. Recently, we,17−19 Robertson,20 and Liu21 have independently reported the synthesis of polyureas from the dehydrogenative coupling of diamines and methanol/diformamides. We have also reported the synthesis of polyethylenimines a from the coupling of diols and diamines using the hydrogen-borrowing approach.22 Along this line, Robertson reported the synthesis of high molar mass polyesters from the dehydrogenative coupling of diols with an alkyl spacer of six carbons or more (e.g., hexane diol) using Milstein’s RuPNN catalyst.23 Smaller diols, such as ethylene glycol or propylene glycol, did not result in the formation of polyester, presumably due to the formation of a metallacycle with ruthenium that could block the active site. Recently, Milstein has reported the use of ethylene glycol as a liquid organic hydrogen carrier, where ethylene glycol was dehydrogenated to form a “polyester,” which could be hydrogenated back to ethylene glycol.24 However, limited emphasis was given to the isolation and chemical and physical characterization of the formed polymers.

1,2-Diols, such as ethylene glycol, propylene glycol, and glycerol, can be sourced from biomass and are attractive feedstocks for making renewable polymers.25−28 We envisioned that their dehydrogenative/dehydrative coupling could lead to the formation of polyester, polyether, or polyesterether. To test this hypothesis, we studied the polymerization of ethylene glycol using bifunctional ruthenium catalysts known for the dehydrogenation of alcohols and hydrogenation of carbonyl compounds, as reported herein.

Experimental Section

General Method for Polymerization of Ethylene Glycol under Closed Conditions

A 100 mL ampule equipped with a J. Young’s valve was charged with precatalyst (e.g., Ru-5; 8.3 mg, 0.01 mmol, 1 mol %) and base (e.g., KOtBu, 2.2 mg, 0.02 mmol, 2 mol %). THF (2 mL) and ethylene glycol (0.11 mL, 2.0 mmol) were added, and the flask was sealed under an argon atmosphere before heating to the desired temperature (e.g., 150 °C) for the desired length of time (e.g., 24 h) with stirring. After this period, the reaction vessel was allowed to cool to room temperature, and the amount of gas evolved (presumably H2) during the reaction was measured by syringe and analyzed by GC-TCD (Gas Chromatography-Thermal Conductivity Detector). The solvent was removed by rotary evaporator. Water (10 mL) was then added to the residue, followed by vacuum filtration to remove any solid as the desired product is soluble in water. The aqueous solution containing the product was concentrated using a rotary evaporator to remove the water. It was then analyzed by different characterization techniques like NMR and IR spectroscopy, GPC, TGA, and DSC, further details of which are given in the Supporting Information.

Results and Discussion

We began our investigation by studying the self-coupling of ethylene glycol in the presence of various ruthenium catalysts known for their catalytic dehydrogenation of alcohols. In a pilot experiment, 2 mmol of ethylene glycol was refluxed in 2 mL of THF in a sealed system in the presence of 1 mol % Ru-MACHO complex (Ru-1) and 2 mol % KOtBu at 150 °C for 24 h (Table 1, entry 1). At the end of the reaction, 24 mL of gas was collected in the overhead space of the Young’s flask. Analysis of the gas by GC-TCD (Gas Chromatography-Thermal Conductivity Detector) confirmed that the released gas was mainly H2 with a small component of CO (<1%). Conversion of ethylene glycol was found to be 63%, as determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of the crude reaction mixture in D2O using ethylene carbonate as an internal standard. The product was isolated by extraction in water and characterized by NMR, IR spectroscopy, and GPC (Gel Permeation Chromatography). The GPC analysis confirmed the product to be a polymer with a molar mass Mn = 38,020 Da and a dispersity of 1.3. Analysis by NMR spectroscopy revealed that the polymer contains both ester and ether linkages in a ratio of 3.6:1, suggesting that the polymer belongs to the class of polyesterethers (Figure 2A,B). This was further confirmed by IR spectroscopy analysis, which showed the presence of ester (1768 cm–1) and ether linkages (1087–1201 cm–1) in addition to the presence of the O–H (3377 cm–1) and aliphatic C–H (2980 cm–1) stretches (Figure 2D). The HSQC (multiplicity-edited) spectrum (Figure 2C) shows the correlation between the hydrogens and carbons of the polymer and also suggested (see Figure S9) the presence of a hemiacetal-type intermediate, which was further confirmed by the ESI-MS study (Figure 2E) that showed the presence of various random oligoesterethers with molar masses up to 400 Da.

Table 1. Optimization of Catalytic Conditions for the Coupling of Ethylene Glycoli.

| Entry no. | Precatalyst | Base | Solvent | Time (h) | Gas released (mL)a | Conversion (%)b | Molar mass, Mn | Đ | Ester:Etherc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ru-1 | KOtBu | THF | 24 | 24 | 63 | 38,020 | 1.3 | 3.6:1 |

| 2 | Ru-2 | KOtBu | THF | 24 | 19 | 37 | 34,640 | 1.3 | 4.2:1 |

| 3 | Ru-3 | KOtBu | THF | 24 | 3 | 14 | - | - | 1.8:1 |

| 4 | Ru-4 | KOtBu | THF | 24 | 10 | 22 | - | - | - |

| 5 | Ru-5 | KOtBu | THF | 24 | 49 | 89 | 34,450 | 1.3 | 4.6:1 |

| 6d | Ru-5 | KOtBu | THF | 24 | 10 | 20 | - | - | - |

| 7e | Ru-5 | KOtBu | THF | 24 | 22 | 47 | 15,640 | 1.5 | 3.8:1 |

| 8 | Ru-5 | KOtBu | H2O | 24 | 4 | 10 | - | - | - |

| 9 | Ru-5 | KOtBu | Diglyme | 24 | 45 | 83 | 31,200 | 1.3 | 4.2:1 |

| 10 | Ru-5 | KOtBu | DME | 24 | 56 | 91 | 11,770 | 2.6 | 5.6:1 |

| 11 | Ru-5 | KOtBu | DME | 72 | 66 | 95 | 24,320 | 1.5 | 4.8:1 |

| 12f | Ru-5 | KOtBu | Diglyme | 24 | - | 81 | 32,680 | 1.4 | 4.2:1 |

| 13 | Ru-5 | KOtBu | THF | 48 | 60 | 94 | 48,940 | 1.4 | 4.2:1 |

| 14g | Ru-5 | KOtBu | THF | 24 | 43 | 79 | 24,010 | 1.6 | 3.6:1 |

| 15 | KOtBu | THF | 24 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | |

| 16 | Ru-5 | K2CO3 | THF | 24 | 39 | 87 | 29,130 | 1.5 | 3.0:1 |

| 17 | Ru-5 | KOH | THF | 24 | 34 | 84 | 33,370 | 1.4 | 2.8:1 |

| 18 | Ru-5 | KBH4 | THF | 24 | 21 | 55 | 17,370 | 1.6 | 3.4:1 |

| 19 | Ru-5 | - | THF | 24 | 3 | 7 | - | - | - |

| 20h | Ru-5 | KOtBu | THF | 24 | 46 | 83 | 55,830 | 1.2 | 5.6:1 |

Conversion was determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of the crude reaction mixture, using ethylene carbonate as an internal standard and D2O as solvent.

Ester:ether ratio was estimated by 1H NMR spectroscopy (see Supporting Information for more details).

Reaction conducted at 100 °C.

0.5 mol % catalyst was used.

Reaction performed under open flow of argon.

10 mol % KOtBu was used.

Reaction with non-anhydrous ethylene glycol.

Reaction conditions: ethylene glycol: 2 mmol, solvent: 2 mL, catalyst (1 mol %), base (2 mol %).

Figure 2.

1H NMR (A), 13C{1H} NMR (B), HSQC NMR (C), and IR(D) spectra, as well as ESI-MS data (E) for the polyesterether.

To achieve a higher conversion of ethylene glycol, we studied various ruthenium catalysts (Ru-2–Ru-5) under identical reaction conditions. Complexes Ru-2, Ru-3, and Ru-4 resulted in lower conversion rates of ethylene glycol, whereas a higher conversion (89%) was obtained with Ru-5 complex (Table 1, entries 2–5). The polymer obtained in this case was characterized as a polyesterether with a molar mass of 34,450 Da and an ester:ether ratio of 4.6:1 (entry 5). Using Ru-5, we further varied reaction conditions (temperature, catalytic loading, solvent, and time) to achieve a higher conversion of ethylene glycol. Performing the reaction at a lower temperature (100 °C) and with lower complex loading (0.5 mol %) resulted in lower conversion of ethylene glycol (20%, and 47%, respectively), as mentioned in Table 1 (entries 6 and 7). Conducting the reaction in water led to a very low conversion of ethylene glycol (10%, entry 8), whereas performing the reaction in diglyme resulted in a higher conversion of ethylene glycol (83%, entry 9). The polyesterether formed in diglyme was found to have a molar mass of 31,200 Da and an ester:ether ratio of 4.2:1. A higher conversion of 91% was achieved when DME (dimethoxyethane) was used as solvent, although the molar mass of the resulting polyesterether was found to be lower (11,770 Da, entry 10) compared to that obtained in diglyme. Increasing the reaction time to 72 h slightly increased the conversion (95%) and the molar mass (24,320 Da, entry 11). Performing the reaction under an open flow of argon in diglyme solvent did not have much effect on the conversion of ethylene glycol or the characteristics of the formed polyesterether in terms of molar mass or ester:ether ratio (entries 9 and 12). Extending the reaction for a longer time (48 h) in THF led to a higher conversion of ethylene glycol (94%) and the formation of a polyesterether with a higher molar mass (48,940 Da, entry 13) compared to the reaction conducted for 24 h (ethylene glycol conversion: 89%, polymer molar mass: 34,450 Da, entry 5). Using a higher base loading (10 mol %) led to the formation of a polyesterether with a relatively lower molar mass (24,010 Da, entry 14) compared to the example where 2 mol % base was used (entry 5). The use of different bases K2CO3, KOH, and KBH4 led to the formation of polyesterethers with lower molar masses (entries 16–18) compared to those produced using KOtBu base (entry 5). Performing the reaction solely in the presence of KOtBu (2 mol %) without using any metal complex (entry 15) or solely in the presence of complex 5 without using any base (entry 19) did not lead to the formation of any polymer, suggesting the crucial role of both complex 5 and the base. Additionally, conducting the reaction with non-anhydrous ethylene glycol led to the formation of less ether compared to ester, indicating that the presence of water is unfavorable for ether formation (entry 20). Similarly, when the reaction was conducted in the presence of molecular sieves (see the Supporting Information), the ester:ether ratio changed to 3.6:1 from 4.6:1 (entry 5), suggesting that the removal of water can promote the etherification process.

To get an idea of the ether chain length, the saponification of a formed polyesterether (Mn = 35,950 Da, Đ = 1.2) was carried out using KOH as the base and water as the solvent at 150 °C for 24 h. After the completion of the reaction, the resulting reaction mixture was extracted with diethyl ether. Analysis of the reaction mixture revealed a combination of polyethylene glycol (confirmed by NMR spectroscopy) with Mn = 1550 Da (Đ = 2.1) and Mn = 22,660 Da (Đ = 1.5). Additionally, ethylene glycol and a higher molecular weight polyethylene glycol [Mn = 55,580 Da (Đ = 1.2)] were also observed (see Section S1.17).

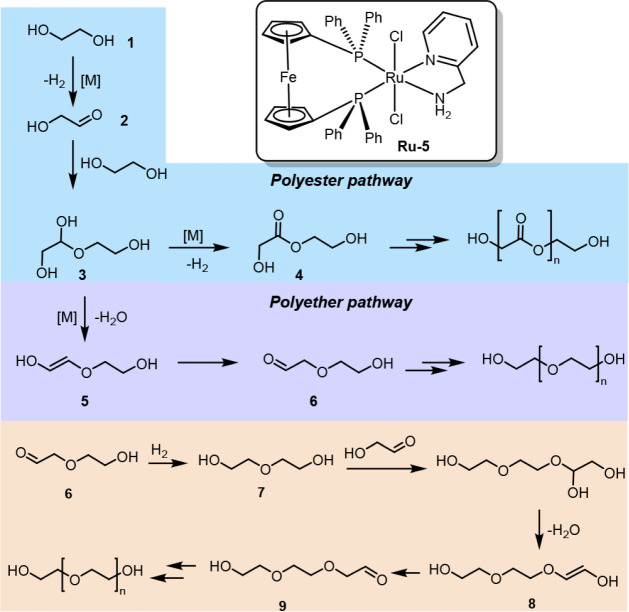

Having developed the catalytic conditions for the formation of polyesterethers, we turned our attention to understanding the mechanism of the process. The dehydrogenative coupling of alcohols to esters is well studied for a number of ruthenium complexes, including Ru-1–Ru-5.29−32 Based on the reported mechanisms, we suggest that the process begins with the catalytic dehydrogenation of ethylene glycol (1) to glycolaldehyde (2) which reacts with another molecule of ethylene glycol to form a hemiacetal (3) that subsequently undergoes dehydrogenation in the presence of the ruthenium catalyst to form an ester (4, Figure 3). However, the formation of ethers from alcohols using bifunctional transition-metal complexes that operate via Noyori-type metal–ligand cooperativity33 (e.g., Ru-1–Ru-5) is intriguing and has not been reported before. In general, alcohol-to-ether transformation is achieved using acid-based catalysts.34 We suggest, in this case, that a possible pathway could operate via the dehydration of hemiacetal 3 to form an enol ether (5), which could tautomerize to the aldehyde ether (6). Conversion of a hemiacetal intermediate to an ether has also been proposed earlier by Beller during the hydrogenation of esters to ethers catalyzed by a ruthenium/Triphos-based catalyst.35 We propose that the formation of a polyether sequence from the aldehyde ether intermediate (6) could proceed via the hydrogenation of the aldehyde group to form diol intermediate 7 that could then react with glycolaldehyde 2 to form intermediate 8 upon dehydration (Figure 3). The enol intermediate 8 could tautomerize to form the aldehyde intermediate 9, and the continuation of this process could lead to the formation of polyether.

Figure 3.

Proposed pathway for the synthesis of polyester and polyether from ethylene glycol.

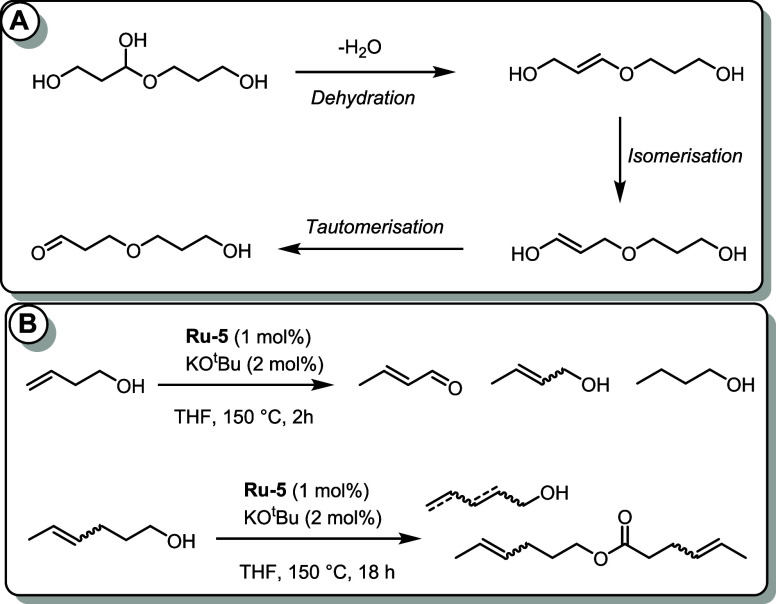

To further investigate this, we also performed DFT calculations (see the Supporting Information for more information and Figure 4). Under the basic dehydrogenative conditions, precatalyst Ru-5 could in situ generate amido-complex IntA. We consider the most stable isomer of IntA (square pyramidal with one hydride in the apical position; see the Supporting Information) as a reference point (ΔG = 0.0 kcal/mol at 423.15 K). The reaction with ethylene glycol follows the commonly observed pattern for ruthenium-based alcohol dehydrogenation catalysis, with the alkoxide as off-cycle intermediate (IntB, −5.0 kcal/mol) and H2-elimination as the rate-limiting transition state (TSA-C = 25.9 kcal/mol, see Figure 4). Importantly, the dual bis-dentate ligand system allows for isomerization, and while IntA is most stable in trans-N-P configuration, the most stable intermediate (TDI) is the cis-dihydride species IntC (−5.8 kcal/mol, after the second H2 elimination step). This is also corroborated by experiments, showing a cis-dihydride as a resting state during dehydrogenative coupling (see discussion below and Section S1.16). Hence, in contrast to the Ru-acridine-ligand system known for ethylene glycol dehydrogenation,24 where an open coordination site is available at ruthenium, in the present case, a hydride trans to the N—N bidentate ligand remains bound along the catalytic cycle, as observed for other pincer-ruthenium systems.36,37 After C—O bond formation between ethylene glycol 1 and glycol aldehyde 2 (TSC-A = 21.8 kcal/mol), the hemiacetal-bound species IntD is formed (+5.1 kcal/mol). Thus, IntD represents the branching point for (poly)ester vs (polyester)ether formation (Figure 4B). While acetal dehydrogenation and H2 elimination provide free ester 4 (0.0 kcal/mol), IntD could also undergo dehydration to release enol 5 together with IntA (10.7 kcal/mol). While we were not able to locate a transition state for this step, metal-assisted C—O bond breakage during repeated optimization attempts is consistent with a kinetically feasible, relatively flat PES38 (see Section S1.16). Nevertheless, the formation of 5 from IntD is 10.7 kcal/mol less favored than ester formation. Tautomerization of 5 to aldehydic ether 6 (+3.3 kcal/mol), e.g., via sigma-complexes IntE (13.8 kcal/mol) or IntF (8.7 kcal/mol), commonly found in ruthenium-catalyzed C—C double bond isomerization39−42 could serve as the driving force for (polyester)ether formation. Indeed, isomerization of alkenes via chain walking and olefin transposition mechanisms has been reported in the past using similar types of bifunctional catalysts that are also known for the dehydrogenation of alcohols.39−42

Figure 4.

(A) Proposed reaction mechanism for ethylene glycol dehydrogenation to ester promoted by precatalyst Ru-5. (B) Possible bifurcation of reaction pathway toward ether intermediate 6. Free energies were calculated at 423.15 K and at 1 M concentration of solutes in kcal/mol (see the Supporting Information for details).

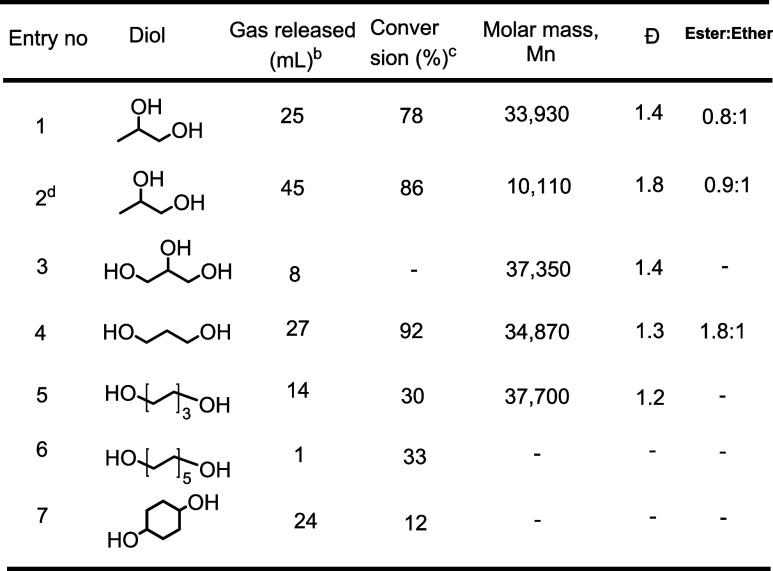

Thus, the relative propensity of ether bond formation vs ester formation will depend on the free energy of H2-release vs H2O-formation (affected, e.g., by temperature, solubility, mass transfer between the liquid and gas phase29 and the isomerization of the C—C double bond for possible enol tautomerization to the aldehyde). With a simple statistical redistribution of the C—C double bond, longer-chain diols are thus expected to give lower yields of (polyester)ether. Indeed, while 1,2-diols and 1,3-diols led to the formation of polyesterethers (Table 2, entries 1–4), higher diols such as 1,6-hexanediol and 1,10-decanediol led to the formation of a polyester (Table 2, entries 5 and 6, see the Supporting Information). Additionally, 1,4-cyclohexanediol under the reaction conditions of Table 2 (entry 1) led to the formation of 4-hydroxycyclohexan-1-one, and the formation of a polymer was not observed in this case (entry 7). Similarly, performing the dehydrogenation of 1-phenylethanol under the reaction conditions of Table 2 (entry 1) led to the formation of acetophenone as the only product with a 45% yield. The lack of ether formation in this case further confirms the hypothesis of the need for an enol-ether type intermediate to form ether. To further confirm this hypothesis of C=C double bond isomerization, we studied the reactivity of 3-butenol and 4-hexenol in the presence of Ru-5 (1 mol %) precatalyst and KOtBu (2 mol %; Figure 5B). Interestingly, alcohols, aldehydes, and esters with varying positions of C=C were observed, suggesting the possibility of alkene isomerization as hypothesized in Figure 5A. The crucial role of the tautomerization step (only possible with diols) was also addressed by control experiments with n-hexanol or n-propanol instead of ethylene glycol. Under the catalytic conditions described in Table 1 (entry 5), n-hexanol/n-propanol led to the formation of hexanal/propanal and hexyl hexanoate/propyl propanoate, and no ether was formed in this case. This is further supported by the lack of observation of any alkene groups in the NMR spectra of the formed polyesterethers (Table 1 and see Section S1.9) as the enol-ether intermediate (5) can easily tautomerize to form the aldehyde-ether intermediate (6). To probe whether an aldehyde group could be hydrogenated under the reaction conditions, we performed the polymerization of ethylene glycol (as per the conditions of Table 1, entry 5) in the presence of hexanal (1 mmol). Interestingly, 59% of hexanal was hydrogenated to hexanol in addition to the formation of polyesterether, confirming our hypothesis that the aldehyde group can be hydrogenated to alcohol under these reaction conditions.

Table 2. Polymerization with Propylene Glycol, Glycerol, and α,ω-Diols.

Reaction conditions: diol: 2 mmol, THF: 2 mL, Ru-5 (1 mol %), KOtBu (2 mol %), 150 °C, 24 h.

In all cases, released gas was identified to be mainly H2 with ≤1% of CO using GC-TCD analysis.

Conversion was determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of the crude reaction mixture, using ethylene carbonate as an internal standard and D2O as a solvent.

Reaction conducted at 170 °C. Molecular weight in the case of 1,10-decanediol could not be estimated due to solubility issues.

Figure 5.

Isomerization and tautomerization steps in the case of 1,3-propanediol (A), and reactivity of alkenols using the Ru-5 precatalyst (B).

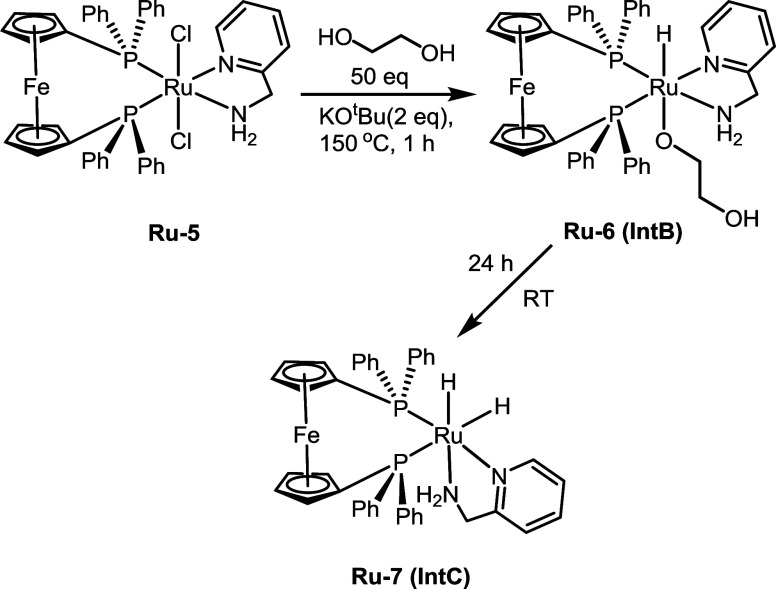

To understand the nature of the catalytically active species, we monitored the catalytic reaction by NMR spectroscopy. A 1H NMR spectrum taken after 1 h of reaction time under the catalytic conditions described in Table 1, entry 5 (1 mol % complex 5, 2 mol % KOtBu, THF, 150 °C) showed a doublet of doublets centered at δ −6.47 ppm, suggestive of a hydride species that is both cis (2JPH = 27.7 Hz) and trans (2JPH = 120.5 Hz) to phosphorus (see Figure S114). The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum (see Figure S115) showed the presence of two ruthenium bis-phosphine complexes with both phosphorus atoms being cis to each other (δ 45.1, 37.3, 2JPP = 25.2 Hz; and δ 54.5, 21.8, 2JPP = 14.0 Hz). Based on this, we speculate the formation of a ruthenium hydrido alkoxide complex Ru-6 (IntB,Figure 6). Interestingly, leaving the reaction mixture for a further 24 h at room temperature resulted in the disappearance of these signals in 1the H and 31P{1H} NMR spectra. Instead, two hydride signals centered at δ −6.48 [dt: 2JPH = 23.3 Hz (t) and 2JHH = 5.5 Hz (d)] and −7.9 [ddd: 2JPH = 34.3 Hz (coupling with cis phosphorus), 74.4 Hz (coupling with trans phosphorus), and 2JHH = 5.9 Hz] ppm were observed. These hydride signals are suggestive of a cis-dihydride species complex Ru-7 (IntC,Figure 6). This was further confirmed by the observation of m/z = 767.06 Da in the ESI-MS, which corresponds to the dihydride complex Ru-7 (expected m/z: 767.09 Da).

Figure 6.

Observation of ruthenium hydride species under catalytic conditions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we report a new method for the synthesis of an aliphatic polyesterether via ruthenium-catalyzed dehydrative/dehydrogenative polymerization of ethylene glycol. Under our optimized catalytic conditions (1 mol % ruthenium precatalyst, 2 mol % base), we successfully synthesized an aliphatic polyesterether with a reasonable molar mass (34,450 Da) and dispersity (1.3). H2 gas and H2O are eliminated as the only byproducts in this process. We propose that the reaction occurs via the dehydrogenation of ethylene glycol to glycolaldehyde, which reacts with another molecule of ethylene glycol to form a hemiacetal intermediate. This intermediate can undergo either dehydrogenation to produce an ester or dehydration to form an enol intermediate, which can tautomerize to yield an aldehyde intermediate ready for further chain propagation (Figure 3). The DFT computations suggest that both dehydration and dehydrogenation pathways are facile for ethylene glycol, leading to the formation of polyesterether (Figure 4). The ability of enol ether to tautomerize into an aldehyde is an important step from a thermodynamic perspective, enabling the formation of ether in the case of ethylene glycol but not in the case of propanol. Similarly, both dehydration and dehydrogenation pathways are possible for propylene glycol, glycerol, and 1,3-propanediol, leading to the formation of both ester and ether functionalities (Table 2). In the case of 1,3-propanediol, we suggest that the alkene formed upon dehydration can undergo a chain-walking process to produce an enol intermediate, which can tautomerize to form an aldehyde (Figure 5A). However, we do not observe the formation of ethers in the cases of 1,6-hexanediol and 1,10-decanediol, likely due to the low concentration of the appropriate enol intermediate that could tautomerize to form an aldehyde (Figure 5). Considering that some of these diols (ethylene glycol, propylene glycol, and glycerol) are sourced from renewable feedstocks, the reported methodology presents a useful route for synthesizing renewable polyesterethers.

Acknowledgments

This research is funded by a UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship (MR/W007460/1) and an EPSRC grant (EP/Y005449/1). We thank Johnson Matthey, Cambridge (Dr Antonio Zanotti-Gerosa and Dr Damian Grainger) for their generous donation of ruthenium complexes Ru-2–Ru-5 used in this study. Computations were performed using HPC resources from GENCI-CINES (AD010812061R3).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssuschemeng.5c00886.

Catalytic studies, characterization details, and DFT details (PDF)

The raw research data supporting this publication can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.17630/15c7c187-a8d6-42db-abea-c5df539e14e6.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Alosime E. M. A Review on Copoly(Ether-Ester) Elastomers: Degradation and Stabilization. J. Polym. Res. 2019, 26 (12), 293. 10.1007/s10965-019-1913-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ulery B. D.; Nair L. S.; Laurencin C. T. Biomedical Applications of Biodegradable Polymers. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 2011, 49 (12), 832–864. 10.1002/polb.22259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y.; Chen Y.; Song Q.; Hu S.; Zhao J.; Zhang G. Base-to-Base Organocatalytic Approach for One-Pot Construction of Poly(Ethylene Oxide)-Based Macromolecular Structures. Macromolecules 2016, 49 (18), 6817–6825. 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J.; Pahovnik D.; Gnanou Y.; Hadjichristidis N. A “Catalyst Switch” Strategy for the Sequential Metal-Free Polymerization of Epoxides and Cyclic Esters/Carbonate. Macromolecules 2014, 47 (12), 3814–3822. 10.1021/ma500830v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S.; Wang Y.; Ding W.; Zhou X.; Liao Y.; Xie X. Lewis Pair Catalyzed Highly Selective Polymerization for the One-Step Synthesis of AzCy(AB)XCyAz Pentablock Terpolymers. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11 (10), 1691–1695. 10.1039/C9PY01508F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M.; Dong Q.; Wang D.; Byers J. A. Electrochemically Switchable Ring-Opening Polymerization of Lactide and Cyclohexene Oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (17), 5686–5690. 10.1021/jacs.8b02171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biernesser A. B.; DelleChiaie K. R.; Curley J. B.; Byers J. A. Block Copolymerization of Lactide and an Epoxide Facilitated by a Redox Switchable Iron-Based Catalyst. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55 (17), 5251–5254. 10.1002/anie.201511793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Wang X.; Li Z.; Wei F.; Zhu H.; Dong H.; Chen S.; Sun H.; Yang K.; Guo K. A Switch from Anionic to Bifunctional H-Bonding Catalyzed Ring-Opening Polymerizations towards Polyether–Polyester Diblock Copolymers. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9 (2), 154–159. 10.1039/C7PY01842H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stößer T.; Sulley G. S.; Gregory G. L.; Williams C. K. Easy Access to Oxygenated Block Polymers via Switchable Catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10 (1), 2668. 10.1038/s41467-019-10481-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Guo J.-Z.; Lu H.-W.; Wang H.-B.; Lu X.-B. Making Various Degradable Polymers from Epoxides Using a Versatile Dinuclear Chromium Catalyst. Macromolecules 2018, 51 (3), 771–778. 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b02042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q.; Li X.; Zhu W. High Molecular Weight Biodegradable Poly(Ethylene Glycol) via Carboxyl-Ester Transesterification. Macromolecules 2020, 53 (6), 2177–2186. 10.1021/acs.macromol.9b02177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R.; Zhang H.; Jiang M.; Wang Z.; Zhou G. Dynamics-Driven Controlled Polymerization to Synthesize Fully Renewable Poly(Ester–Ether)s. Macromolecules 2022, 55 (1), 190–200. 10.1021/acs.macromol.1c01899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs J. D.; Tonks I. A. Synthesis of Poly(Ester-Ether) Polymers via Hydroesterificative Polymerization of α,ω-Enol Ethers. Macromolecules 2022, 55 (21), 9520–9526. 10.1021/acs.macromol.2c01935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dannecker P.-K.; Biermann U.; vonCzapiewski M.; Metzger J. O.; Meier M. A. R. Renewable Polyethers via GaBr3-Catalyzed Reduction of Polyesters. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (28), 8775–8779. 10.1002/anie.201804368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunanathan C.; Milstein D. Applications of Acceptorless Dehydrogenation and Related Transformations in Chemical Synthesis. Science 2013, 341, 6143. 10.1126/science.1229712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnanaprakasam B.; Balaraman E.; Gunanathan C.; Milstein D. Synthesis of Polyamides from Diols and Diamines with Liberation of H2. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2012, 50 (9), 1755–1765. 10.1002/pola.25943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owen A. E.; Preiss A.; McLuskie A.; Gao C.; Peters G.; Bühl M.; Kumar A. Manganese-Catalyzed Dehydrogenative Synthesis of Urea Derivatives and Polyureas. ACS Catal. 2022, 12 (12), 6923–6933. 10.1021/acscatal.2c00850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLuskie A.; Brodie C. N.; Tricarico M.; Gao C.; Peters G.; Naden A. B.; Mackay C. L.; Tan J.-C.; Kumar A. Manganese Catalysed Dehydrogenative Synthesis of Polyureas from Diformamide and Diamines. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2023, 13 (12), 3551–3557. 10.1039/D3CY00284E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Armstrong D.; Peters G.; Nagala M.; Shirran S. Direct Synthesis of Polyureas from the Dehydrogenative Coupling of Diamines and Methanol. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 6153. 10.1039/D1CC01121A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langsted C. R.; Paulson S. W.; Bomann B. H.; Suhail S.; Aguirre J. A.; Saumer E. J.; Baclasky A. R.; Salmon K. H.; Law A. C.; Farmer R. J.; Furchtenicht C. J.; Stankowski D. S.; Johnson M. L.; Corcoran L. G.; Dolan C. C.; Carney M. J.; Robertson N. J. Isocyanate-Free Synthesis of Ureas and Polyureas via Ruthenium Catalyzed Dehydrogenation of Amines and Formamides. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139 (18), 52088. 10.1002/app.52088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J.; Tang J.; Xi H.; Zhao S.-Y.; Liu W. Manganese Catalyzed Urea and Polyurea Synthesis Using Methanol as C1 Source. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34 (4), 107731. 10.1016/j.cclet.2022.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie C. N.; Owen A. E.; Kolb J. S.; Bühl M.; Kumar A. Synthesis of Polyethyleneimines from the Manganese-Catalysed Coupling of Ethylene Glycol and Ethylenediamine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202306655 10.1002/anie.202306655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsicker D. M.; Dauphinais B. C.; Mc Ilrath S. P.; Robertson N. J. Synthesis of High Molecular Weight Polyesters via In Vacuo Dehydrogenation Polymerization of Diols. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2012, 33 (3), 232–236. 10.1002/marc.201100653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y. Q.; von Wolff N.; Anaby A.; Xie Y.; Milstein D. Ethylene Glycol as an Efficient and Reversible Liquid-Organic Hydrogen Carrier. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2 (5), 415–422. 10.1038/s41929-019-0265-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waiba S.; Maji K.; Maiti M.; Maji B. Sustainable Synthesis of α-Hydroxycarboxylic Acids by Manganese Catalyzed Acceptorless Dehydrogenative Coupling of Ethylene Glycol and Primary Alcohols**. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62 (10), e202218329 10.1002/anie.202218329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo S. T.; Mohanty A.; Sharma R.; Daw P. A Switchable Route for Selective Transformation of Ethylene Glycol to Hydrogen and Glycolic Acid Using a Bifunctional Ruthenium Catalyst. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52 (42), 15343–15347. 10.1039/D3DT01671D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Nielsen M.; Li B.; Dixneuf P. H.; Junge H.; Beller M. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Hydrogen Generation from Glycerol and Selective Synthesis of Lactic Acid. Green Chem. 2015, 17 (1), 193–198. 10.1039/C4GC01707B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Daw P.; Milstein D. Homogeneous Catalysis for Sustainable Energy: Hydrogen and Methanol Economies, Fuels from Biomass, and Related Topics. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122 (1), 385–441. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Raffa G.; Nguyen D. H.; Swesi Y.; Corbel-Demailly L.; Capet F.; Trivelli X.; Desset S.; Paul S.; Paul J.-F.; Fongarland P.; Dumeignil F.; Gauvin R. M. Acceptorless Dehydrogenative Coupling of Alcohols Catalysed by Ruthenium PNP Complexes: Influence of Catalyst Structure and of Hydrogen Mass Transfer. J. Catal. 2016, 340, 331–343. 10.1016/j.jcat.2016.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putignano E.; Bossi G.; Rigo P.; Baratta W. MCl2(Ampy)(Dppf) (M = Ru, Os): Multitasking Catalysts for Carbonyl Compound/Alcohol Interconversion Reactions. Organometallics 2012, 31 (3), 1133–1142. 10.1021/om201189r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schley N. D.; Dobereiner G. E.; Crabtree R. H. Oxidative Synthesis of Amides and Pyrroles via Dehydrogenative Alcohol Oxidation by Ruthenium Diphosphine Diamine Complexes. Organometallics 2011, 30 (15), 4174–4179. 10.1021/om2004755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trincado M.; Bösken J.; Grützmacher H. Homogeneously Catalyzed Acceptorless Dehydrogenation of Alcohols: A Progress Report. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 443, 213967. 10.1016/j.ccr.2021.213967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khusnutdinova J. R.; Milstein D. Metal-Ligand Cooperation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (42), 12236–12273. 10.1002/anie.201503873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal S.; Mandal S.; Ghosh S. K.; Sar P.; Ghosh A.; Saha R.; Saha B. A Review on the Advancement of Ether Synthesis from Organic Solvent to Water. RSC Adv. 2016, 6 (73), 69605–69614. 10.1039/C6RA12914E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Topf C.; Cui X.; Junge K.; Beller M. Lewis Acid Promoted Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Etherifications by Selective Hydrogenation of Carboxylic Acids/Esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (17), 5196–5200. 10.1002/anie.201500062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch M.; Luo J.; Avram L.; Ben-David Y.; Milstein D. Mechanistic Investigations of Ruthenium Catalyzed Dehydrogenative Thioester Synthesis and Thioester Hydrogenation. ACS Catal. 2021, 11 (5), 2795–2807. 10.1021/acscatal.1c00418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberico E.; Lennox A. J. J.; Vogt L. K.; Jiao H.; Baumann W.; Drexler H. J.; Nielsen M.; Spannenberg A.; Checinski M. P.; Beller M. Unravelling the Mechanism of Basic Aqueous Methanol Dehydrogenation Catalyzed by Ru-PNP Pincer Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (45), 14890–14904. 10.1021/jacs.6b05692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar S.; Luo J.; Rauch M.; Diskin-Posner Y.; Ben-David Y.; Milstein D. Dehydrogenative Ester Synthesis from Enol Ethers and Water with a Ruthenium Complex Catalyzing Two Reactions in Synergy. Green Chem. 2022, 24 (4), 1481–1487. 10.1039/D1GC04574A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W.; Chernyshov I. Y.; Weber M.; Pidko E. A.; Filonenko G. A. Switching between Hydrogenation and Olefin Transposition Catalysis via Silencing NH Cooperativity in Mn(I) Pincer Complexes. ACS Catal. 2022, 12 (17), 10818–10825. 10.1021/acscatal.2c02963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdriau S.; Chang M.-C.; Otten E.; Heeres H. J.; de Vries J. G. Alkene Isomerisation Catalysed by a Ruthenium PNN Pincer Complex. Chem. - Eur. J. 2014, 20 (47), 15434–15442. 10.1002/chem.201403236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A. M.; Greene K. H.; Allen A. R.; Farris B. M.; Szymczak N. K.; Stephenson C. R. J. Catalytic Olefin Transpositions Facilitated by Ruthenium N,N,N-Pincer Complexes. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89 (13), 9647–9653. 10.1021/acs.joc.4c00304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Navarro S.; Mon M.; Doménech-Carbó A.; Greco R.; Sánchez-Quesada J.; Espinós-Ferri E.; Leyva-Pérez A. Parts–per–Million of Ruthenium Catalyze the Selective Chain–Walking Reaction of Terminal Alkenes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13 (1), 2831. 10.1038/s41467-022-30320-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.