Abstract

Lithium-rich layer oxides are expected to be high-capacity cathodes for next-generation lithium-ion batteries, but their performance is hindered by irreversible anionic redox, leading to voltage decay, lag, and slow kinetics. In order to solve these problems, we regulate the Ni/Mn spin state in Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2 by Be doping, which generates the superexchange interaction and activates Ni-t2g orbitals. The activation of Ni-t2g orbitals triggers the reductive coupling mechanism between Ni/O, which improves the reversibility and kinetics of anionic redox. The strong π-type Ni-t2g/O-2p interaction forms a stable Ni-(O–O) configuration, suppressing excessive anion oxidation. In this work, the Be modified cathodes have good cycle stability, 0.04 mAh/g and 0.5 mV decay per cycle over 400 cycles at 1 C (60 min, 250 mA g−1), with a rate performance of 187 mAh/g at 10 C (6 min, 2500 mA g−1), providing a strategy for stabilising oxygen redox chemistry and designing high performance lithium-rich cathodes.

Subject terms: Batteries, Batteries

Li-rich oxides face challenges such as voltage decay and slow kinetics due to irreversible anionic reaction. Here, authors activated the Ni-t2g orbitals through generating superexchange interactions via Be doping. By triggering the reduction coupling mechanism, the reversibility and kinetics of the anionic reaction are effectively improved.

Introduction

With the growing global demand for clean energy and sustainable development, lithium-ion batteries have become a mainstream player in the storage and conversion of new energy sources due to their high energy density, long cycle life and environmental friendliness1–3. The practical capacity of currently commercialised conventional layered transition metal oxides LiTMO2 (TM = Ni, Mn, Co, etc) is close to its theoretical value. Lithium-rich manganese-based cathode (Li/TM1) with TM and O redox activity, high reversible capacity (250 mAh/g), and low cost is considered as one of the few options to increase the energy density of lithium-ion batteries4–7. However, there are a lot of irreversible reactions in anionic redox (OAR) process at high voltage, which leads to serious voltage decay and energy density loss in long cycle, severely limiting the practical application of Li-rich cathode materials8–10.

A large number of studies have inhibited the failure of Li-rich materials by substitution of TM and oxygen sites, surface coating, etc., but their criticised voltage lag and decay have not been significantly reduced11–15. Li2IrO3 and Li2RuO3 materials exhibit a more reversible OAR reaction attributed to the strong orbital overlap between the TM 4/5 d and O 2p states. Electrons can be transferred from the non-bonded O 2p band to the TM nd band at high voltage, inhibiting the transition of the O–O dimerisation state to O2. The above process is known as the reductive coupling mechanism16–18. However, the strong covalent interaction reduces the redox potential, which leads to a loss of energy density, and the high cost limits the further application of the above materials19. Conventional 3 d transition metals (Ni, Mn, Co, etc) exhibit weak covalent interactions with anions, and thus their coordinated anion reversibility is low, but can maintain a higher energy density20. Therefore, how to trigger the reductive coupling mechanism of 3 d transition metals is an effective way to promote the commercialization of lithium-rich cathode. Ni has become an essential element in commercialised materials due to its high operating voltage and activity, while the small energy level difference between O 2p and Ni2+/Ni4+ makes conditions exist for triggering reductive coupling mechanism15,21,22. However, whether there is reductive coupling mechanism between Ni and O is still controversial, thus its triggering conditions and mechanism need to be further clarified23–26.

In the Li2TM4O configuration, four O 2p orbitals form σ-type bonding (a1 and b2) and antibonding (a1* and b2*) molecular orbitals with TM nd(eg), (n + 1)s, and (n + 1)p. The remaining two O 2p orbitals form π-type bonding (b1) and antibonding (b1*) molecular orbitals with TM nd(t2g). The non-bonding O 2p orbital level is located between b1 and b1*, so t2g is close to the O 2p level and is more prone to hybridize with O 2p. In traditional materials, Ni is in a low spin state, and the oxidation process is Ni2+(t2g6 eg2)/Ni3+(t2g6eg1)/Ni4+(t2g6eg0)27. The eg orbital of Ni2+/Ni3+/Ni4+ is not fully filled and can accept electrons, but the large energy level difference results in the isolated redox behaviour of Ni and O23,28. Although the t2g orbitals exhibit sufficient hybridization with the O 2p orbitals, they remain fully occupied during the redox process and cannot accept electrons from O 2p orbitals. If the empty orbital is constructed in Ni-t2g, the reductive coupling mechanism can be triggered, leading to the formation of Ni-(O–O) configurations22,29 and thereby promoting the reversible OAR process. Although there are abundant empty orbitals in the t2g orbital of Mn4+, its energy level is much lower than that of the O 2p orbital. As a result, Mn remains in the +4 state during charging, and the anion does not provide electrons to Mn4+10,25.

To regulate the electronic occupancy of t2g and eg orbitals, it is essential to regulate the spin states of TM. Xia’s team synthesized Li-rich cathode materials with different spin states by high-temperature solid-phase reaction and proposed a mechanism to reduce the voltage based on “isolated eg-electron filling”19. Meanwhile, Pan’s research team discovered TM-O-TM superexchange interactions in traditional ternary layered materials30, where the p orbitals of O²⁻ ions interact with the d orbitals of TM cations to adjust the electronic occupancy of t2g/eg orbitals31. However, the application of superexchange in Li-rich materials has not been fully explored. In this study, introducing Be atoms into the interstitial sites of Li-rich materials activated Ni-O-Mn superexchange, triggering orbital interactions between Ni and Mn and successfully regulating the spin states of TM. This work clarifies the interaction between d orbitals and O 2p orbitals in the reductive coupling mechanism, and introduces the superexchange interaction to regulate the TM spin state as a switch to trigger the reductive coupling mechanism. The modified material exhibits good electrochemical performance with low voltage and performance decay. Through theoretical calculation and experimental results, the interaction relationship between superexchange and reductive coupling was further analyzed, and the mechanism of energy storage of the material was clarified.

Results

Structure of LLOs and Be-1/2/3

Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2O2(denoted as LLOs) was synthesized by coprecipitation and solid phase sintering. Different Be-doped materials are Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2BexO2 (X = 0.01, 0.02, 0.03), denoted as Be-1, Be-2, and Be-3. Supplementary Table 1 shows the analysis results of the elements in the different samples. XRD refinement results indicate the presence of LiTMO2 phase (R-3m) and Li2MnO3 phase (C2/m) (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1b, c), where the diffraction peak around 21° corresponds to the honeycomb superstructure in the Li2MnO3 phase24. The dual-phase structure was shown in Supplementary Fig. 1e, f. Be-2 exhibited lattice stripes with a spacing of 0.481 nm, larger than LLOs (0.475 nm) (Supplementary Fig. 2d). Particle sizes ranged between 100-200 nm for both LLOs and Be doped samples (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) confirmed uniform elemental distribution, though Be was not detected due to its smaller atomic number. The XPS etching analysis demonstrates the presence and uniform doping of Be (Fig. 1c). Infrared Spectroscopy (IR) and Raman spectra confirmed BeO4 stretching vibrations (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 3)32–34. Mn-O bond stretching vibrational peaks shift towards lower wave number, while Li-O peaks remained unchanged, suggesting Be occupies TM layer tetrahedral sites without entering the Li layer35. XRD refinement results show that the TM layer spacing changes significantly, consistent with TM-O bond elongation (Supplementary Table 2). S(TMO2) and I(LiO2) correspond to transition metal (TM) layer spacing and alkali metal (AM) layer spacing, respectively. As the Be content increases, the (003) crystal plane spacing increases and then decreases (Supplementary Fig. 1d), which is consistent with the change of TM-O bond length. The possible occupation of Be in the material was analysed by calculation (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 4), which showed that Be preferentially occupies tetrahedral sites in the TM layer.

Fig. 1. Structural analysis.

a XRD refinement results of Be-2. b SEM, HRTEM and EDS spectra images of Be-2. c Be 1 s XPS spectra of Be-2 at different etching time; (d) Infrared spectrum analysis results. e The formation energy of Be occupies different sites. f, g XANES spectra, and (h, i) corresponding FT-EXAFS spectra of Be-2 and LLOs. j, k. Atomic distribution in the superstructure of Be-2 and LLOs.

Normalized X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) analysis at the Ni/Mn K-edge revealed Ni2+ and Mn4+ in LLOs (Fig. 1f, g)25. Be-2 exhibited unusual valence changes, an increase in the Ni valence state and a decrease in the Mn valence state (Supplementary Fig. 5) this behaviour is attributed to the superexchange effect and is analysed in detail subsequently. The degree of the unusual valence change deepened with the increase of Be content (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). EPR and XPS confirmed similar oxygen environments in LLOs and Be-doped samples, excluding oxygen environment effects on TM electronic structure (Supplementary Fig. 6c and 7). Fourier transform extended X-ray absorption fine structure (FT-EXAFS) spectroscopy revealed the elongated Mn-O bond length (1.898–1.914 Å) and shortened Ni-O bond length (2.040–1.882 Å) in Be-2 (Supplementary Table 3) compared with LLOs, which correspond to the decrease in the valence state of Mn and the increase in the valence state of Ni, respectively (Fig. 1h, i). The corresponding K and R space fits are shown in the Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9. The change in the intensity of the second Mn-TM and Ni-TM shell peaks suggests that the corresponding coordination number has changed36. The coordination number of Ni is actually reduced, proving that Li ions with fewer extranuclear electrons are involved in the Ni-TM coordination, so more Ni atoms are present in the LiTM6 unit. Similarly, the Li/Mn atoms in the Li2MnO3 phase enter the Li-deficient region of the TM layer, resulting in an increase of the coordination number around Mn. Above results indicate the presence of locally enriched Mn (Blue dashed box) and Ni (Yellow dashed box) in the LLOs (Fig. 1j), corresponding to the configurations Mn-3Mn and Ni-3Ni, with a single elemental composition in the honeycomb superstructure. More Ni-2Ni1Mn, Ni-3Mn, and Mn-2Ni1Mn configurations are present in Be-2 (Fig. 1k), with a more homogeneous mixing of elements in the TM layer, blue and red solid lines represent Mn and Ni atoms, respectively. Be doping diffuses the LiO6 units by deep solid solution reaction (Supplementary Table 2) without reducing the Li content7, ensuring the high capacity of the material, while alleviating the lattice oxygen loss37 and severe structural strain28 caused by a single element in the superstructure.

Formation mechanism of superexchange

Soft X-ray spectroscopy analysis of the Ni/Mn L3-edge spectra reveals electronic occupancy states. In Be-2, the Mn L3-edge shows t2g/eg peak area ratio of 0.31, lower than 0.45 in LLOs, indicating higher t2g orbital occupancy and fewer empty orbitals (Fig. 2a). For Ni, the t2g/eg ratio in Be-2 is 5.32, higher than 3.57 in LLOs, suggesting lower t2g orbital occupancy38. X-ray linear dichroism (XLD) further clarify occupancy in different orbitals, which is quantified as the intensity difference (I∥-I⊥)/(I∥ + I⊥) between in-plane (E∥ab) and out-of-plane (E⊥ab) XAS39. Be-2 exhibits significant t2g variability, while eg orbitals remain stable (Fig. 2c). Both t2g and eg orbitals are unchanged in LLOs (Supplementary Fig. 10). XLD results for Ni and Mn L3-edges (Supplementary Fig. 11) show the t2g variation of Be-2 under different polarizations, indicating asymmetric electron occupation, whereas LLOs maintain highly symmetric occupation of the t2g and eg orbitals40,41. The above results indicate that t2g/eg peak area variations in Ni/Mn L3-edges is caused by t2g orbital occupancy changes, suggesting that the superexchange effect of Ni-O-Mn occurs mainly through the t2g orbitals between Ni/Mn.

Fig. 2. Superexchange mechanism.

a, b Mn and Ni L3-edge EXAFS spectra of LLOs and Be-2. c Normalized XLD spectra of the O K-edge for Be-2. d, e Mn and Ni Kβ XES of LLOs and Be-2. Note that the spectra were normalized by peak intensity. f Temperature dependence of the molar magnetic susceptibility of Be-2. The variation of inverse magnetic susceptibility (ZFC/FC) is shown on the right y-axis together with the Curie-Weiss fit. g, h Ni-O-Mn structure and electronic structure in LLOs and Be-2.

Additionally, X-Ray emission spectroscopy (XES) analyses Mn and Ni oxidation and spin states (Fig. 2d, e). The Kβ emission lines of 3 d transition metals result from a dipole-allowed 3p → 1 s decay process filling a core hole (1s13p63 dn) and leaving a 1s23p53 dn final state. The 3p-3d exchange coupling can lead to a Kβ1,3/Kβ′ energy splitting, and the Kβ′ intensity reflects unpaired 3d electrons, indicating spin states42,43. For Mn, Be-2 shows a weaker Kβ′ peak than LLOs, suggesting fewer unpaired electrons and more low-spin Mn configurations, with the Kβ1,3 peak shifting to lower energies, indicating lower spin and valence states. For Ni, Be-2 exhibits a stronger Kβ′ peak, indicating more unpaired electrons and high-spin Ni configurations, with the Kβ1,3 peak shifting to higher energies, indicating higher spin and valence states (Supplementary Fig. 12). Magnetic property analysis further clarifies the Ni/Mn spin states. Temperature-dependent magnetization (ZFC and FC) and Curie-Weiss behaviour in the 150–300 K range reveal effective magnetic moments (Supplementary Table 4). In LLOs (Supplementary Fig. 13), μeff = 2.82 μB/Ni and 3.87 μB/Mn correspond to Ni2+(t2g6eg2) and Mn4+(t2g3eg0). In Be-2 (Fig. 2f), μeff = 3.26 μB/Ni and μeff = 3.42 μB/Mn indicate high-spin Ni3+(t2g5eg2) and low-spin Mn3+(t2g4eg0), reducing Jahn-Teller distortion and enhancing structural stability44. It is worth noting that Ni-O-Ni and Mn-O-Mn superexchange does not cause change in the Ni/Mn valence states.

In order to further reveal the effect of Be on the electronic structure in Ni and Mn, the localized electronic structure of Ni-O-Mn was further analyzed. Be doping shifts Mn/Ni-t2g energy levels closer to the Fermi level, activating t2g orbital electronic activity (Supplementary Fig. 14a, b). In Be-2, Ni/Mn-t2g orbitals exhibit spin-polarized behaviour with opposite spin directions, facilitating superexchange interactions31. In contrast, LLOs show non-spin-polarized t2g and eg orbitals, with a low probability of superexchange behaviour. Spin density analysis confirms opposite spin states in Ni/Mn and increased O spin density in Be-2, indicating strong Ni-O-Mn superexchange (Supplementary Fig. 14c–f)30. Density of states (DOS) results show greater t2g/O 2p orbital overlap in Be-2, enhancing electronic interactions, while eg orbitals exhibit minimal overlap and non-spin polarization12,13,15. The Ni-t2g orbitals in Be-2 display unoccupied states above the Fermi level, attributed to superexchange, unlike the fully occupied t2g orbitals in LLOs (Supplementary Fig. 14). In summary, Be doping adjusts t2g orbital energy levels, deepens Ni-t2g/O 2p overlap, and induces Ni/Mn spin polarization, triggering superexchange behaviour, with the transformation of Ni2+(t2g6eg2)/Mn4+(t2g3eg0) into Ni3+(t2g5eg2)/Mn3+(t2g4eg0). Schematic diagrams of Ni-O-Mn superexchange were given in Fig. 2g, h.

Electrochemical performance

During the first activation, the discharge curve changes dramatically relative to the charge curve (Fig. 3a), which is attributed to anion evolution during high-voltage charging (>4.4 V), involving Li2MnO3 phase activation and deep delithiation of the honeycomb superstructure. This creates Li vacancies and O–O dimerization, leading to irreversible disorder (Supplementary Fig. 15). The O²⁻ coordination environment shifts from O-Li4Mn2 to O-Li6, increasing O 2p state energy and causing voltage lag45. Be-doped samples exhibit higher discharge capacity and Coulombic efficiencies, Be-1/2/3 and LLOs are 88.5%, 90.5%, 86.9%, 81.4%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 16). The voltage lag during the first cycle was analysed by the average voltage difference between charging and discharging, and the corresponding differences between Be-1/2/3 and LLOs are 0.88, 0.85, 0.90, and 0.95 V, respectively.

Fig. 3. Electrochemical performance.

a Initial charge/discharge curves at 0.05 C (1200 min, 12.5 mA g−1). b Cycle performances at 1 C (60 min, 250 mA g−1). c Rate performances. d CV cycle test. The relevant redox peaks are marked with coloured ovals. e, f Discharge curves and corresponding dQ/dV curves of LLOs and Be-2 with different number of cycles at 1 C (60 min, 250 mA g−1). g Voltage decay at 1 C (60 min, 250 mA g−1). h Electrochemical performance comparison radar plot. i The comparison of the present study with Be-2. Supplementary Table 5 gives the comparison of specific data.

Be-2 demonstrates good cycling stability, retaining 93% capacity after 400 cycles at 1 C (60 min, 250 mA g−1) with a decay of 0.04 mAh/g per cycle, compared to 49% retention and 0.28 mAh/g per cycle decay in LLOs (Fig. 3b). Rate performance tests reveal Be-2 maintains a discharge capacity of 187 mAh/g at 10 C (6 min, 2500 mA g−1), while LLOs only have 86 mAh/g (Fig. 3c). Cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves at 0.1 mV/s show distinct differences between LLOs and Be-2. LLOs exhibit oxidation peaks at 4.04 V (Ni2+) and 4.63 V (O2−), with asymmetric reduction peaks at 4.48 V (O2n−), 3.75 (Ni4+/O2n−), and 3.25 (Mn4+/O2n−), indicating severe irreversible O2 release and structural disorder. In contrast, Be-2 shows a single oxidation peak at 4.25 V (Ni2+/O²⁻) and symmetrical reduction peaks at 4.4 V (O2n−) and 3.7 V (Ni4+/O2n-), with no low voltage Mn4+/O2n- reduction, suggesting stable Mn valence and more reversible anionic processes (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3e, f show that Be-2 has good voltage retention and stable Mn⁴⁺/O₂ⁿ⁻ reduction peaks, indicating high anion and Mn redox reversibility during long cycling. Be-2 exhibits the voltage retention rate of 94.02% and voltage decay is only 0.5 mV/cycle. LLOs voltage retention rate is 77.41% and voltage decay is 1.96 mV/cycle. (Fig. 3g). The capacity retention of Be-2 after 1000 cycles at 10 C (6 min, 2500 mA g−1) is 81%, while the LLOs shows rapid capacity decay in the first 200 cycles and lost electrochemical activity after 200 cycles. The voltage decay of Be-2 is only 0.52 mV/cycle and LLOs reach 1.06 mV/cycle (Supplementary Fig. 17). As shown in Fig. 3h, i, the introduction of Be not only improves the overall performance of the material, but also voltage and capacity decay stand out in the field of Li-rich cathode materials.

Charge compensation mechanism

Figure 4a and b show the O K-edge XAS spectra of Be-2 in FLY and TEY modes, respectively, with the results of the LLOs shown in Supplementary Fig. 18a, b. Two pre-edge peaks at 530.5 and 532 eV correspond to transitions from O 1 s to empty TM d orbitals hybridized with O 2p orbitals46. During charging (<4.4 V), a shoulder peak emerges at 528.5 eV, attributed to TM oxidation. At high voltage (4.4–4.7 V), a peak near 530.9 eV appears, which corresponds to the feature of anion oxidation47. The integral intensity of the pre-edge peaks increases during charging (<4.4 V), reflecting increased electronic unoccupied states due to TM oxidation (Supplementary Fig. 18c, d). However, an anomaly occurs at high voltage, where LLOs exhibit increased electron unoccupied states at 4.5 V, corresponding to anion oxidation. As charging progresses, the electron holes further increase, leading to O–O dimer formation and eventual irreversible O2 evolution, as confirmed by DEMS. In contrast, Be-2 generates more electron holes early in the high voltage plateau (<4.5 V), which is attributed to the cation mediated enhancement of anion reaction kinetics and oxidation activity (reductive coupling mechanism)48. The reductive coupling mechanism in Be-2 stabilizes anion oxidation by transferring electrons into TM, inhibiting irreversible O2 evolution, so that fewer electron holes are produced in the later stages of the high-voltage plateau4. At the end of the discharge, the peak area of Be-2 almost returns to the OCV state, indicating high reversibility, whereas LLOs show irreversible processes due to large lattice oxygen loss. The O K-edge analysis after long cycle (Supplementary Fig. 18e, f) reveals higher electron unoccupied states in LLOs compared to Be-2, indicating more irreversible redox processes in LLOs. Be-2 maintains high reversibility and cycling stability.

Fig. 4. Charge compensation mechanism.

a, b O K-edge XAS of Be-2 in TFY and FLY mode at different voltage states in the first activation cycle and the 300th cycle. c, d XAS spectra of Be-2 for selected voltage states at Ni and Mn K-edge. e, f Fourier-transformed EXAFS spectra of Be-2. g The Ni L3-edge spectrum of Be-2 at different voltage states in the first activation cycle. h Ratio of t2g and eg peak area of Ni L3-edge spectra for LLOs and Be-2 at different voltage states. i, j Oxidation of Ni with different spin states in LLOs and Be-2. k Charge curve and gas evolution of Be-2 in the first activation cycle. l Schematic illustration of Ni/O redox coupling mechanism.

Differential spectroscopy of the O K-edge (difference of neighbouring curves) shows that both LLOs and Be-2 exhibit TM oxidation peaks at 528.5 eV when charged to 4.4 V (Supplementary Fig. 19)47. However, Be-2 also shows an anion oxidation peak around 530.9 eV at low voltage, attributed to strong Ni/O coupling. At high voltage (4.4–4.7 V), the TM valence of LLOs changes very little, while the decrease in the intensity of the shoulder peak in Be-2 around 528.5 eV corresponds to the triggering of the reductive coupling mechanism. During discharge, both TM and O reduction occur in LLOs and Be-2. The difference spectra relative to OCV (Supplementary Fig. 20) reveal lower redox reversibility of TM and O in LLOs compared to Be-2, with spectral peaks failing to return to the OCV state after discharge. LLOs exhibit high valent TM and oxidized lattice oxygen after 300 cycles, indicating irreversible redox processes and lattice oxygen loss continuously occurred during the long cycle. In contrast, more reversible anion charge compensation process is maintained in Be-2. The above results show that Be-2 has a highly reversible anion charge compensation process, which ensures good electrochemical performance.

XANES and EXAFS spectra (Fig. 4c, d) reveal the charge compensation mechanisms of Mn and Ni in Be-225. During charging to 4.4 V, Mn oxidizes, with its valence state restored upon discharge. In LLOs, Mn remains at +4 during charging, but decreases during discharge due to the release of O2 and structural transformation. For Ni in Be-2, oxidation occurs during charging, but an unusual reduction at 4.4-4.7 V is observed, attributed to the reductive coupling mechanism, where electrons transfer from anions to Ni4+. During discharge, Ni valence state decreases as Li⁺ re-embeds. In LLOs, Ni oxidizes to +4 at 4.4 V, with no further change at high voaltage, indicating independent Ni/O oxidation. During the process of discharge, Ni undergoes reduction. In Be-2, Ni reduction at high voltage is accompanied by the formation of Ni-(O–O) configuration (Supplementary Fig. 22a). Be-2 exhibits a more reversible Mn valence change compared to LLOs, and the anion behaviour does not result in additional Mn reduction (supplementary Fig. 22b), indicating improved structural stability.

Ni L3-edge spectra reveal the charge compensation mechanism of different orbitals. In LLOs, eg orbital intensity changes during charging/discharging (Supplementary Fig. 22c), corresponding to Ni2+ (t2g6eg2)-Ni3+(t2g6eg1)-Ni4+(t2g6eg0) (Fig. 4i). Be-2 exhibits changes in both eg and t2g orbitals due to Ni spin state variation (Fig. 4g), enabling a unique high-spin Ni3+(t2g5eg2)-Ni4+(t2g4eg2) oxidation mechanism (Fig. 4j). The t2g orbitals of Ni⁴⁺ act as electron acceptors during O oxidation, triggering the reductive coupling mechanism. Be-2 shows lower t2g/eg ratios at 4.4 V (Fig. 4h), indicating t2g orbital activation. Between 4.4 and 4.7 V, the decrease in the ratio of t2g/eg in Be-2 corresponds to the reduction of Ni. Overall, the change in the orbital occupation of Be-2 during charging and discharging is more reversible. In-situ differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) (Fig. 4k and Supplementary Fig. 23) indicates that less CO2 and O2 are produced in Be-2, suppressing side reactions. Ex-situ EPR (Supplementary Fig. 24) also indicates that Be-2 has a more reversible OAR process. Figure 4l illustrates the process of electron transfer from O 2p to Ni-t2g orbitals and the schematic diagram of the reductive coupling mechanism. In summary, the superexchange effect regulates the TM spin state, inducing the formation of electron holes in the t2g orbitals and enhancing the hybridisation of TM 3 d and O 2p. The transfer of electrons from O 2p to Ni-t2g orbitals under high voltage successfully triggered the reductive coupling mechanism, effectively enhancing the reversibility of the anion.

Structural evolution and kinetic analyses

Electrochemical tests reveal the kinetics of Be-2. CV curves and Randles-Sevcik analysis (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 26a) show that Be-2 has a higher Li⁺ diffusion coefficient (Fig. 5b)49. Galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT) results (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 25) further confirm the enhanced Li⁺ diffusion in Be-2. Pseudocapacitance contribution analysis (Supplementary Fig. 26b–f) shows the larger pseudocapacitance behaviour of Be-2, indicating stronger Li⁺ diffusion kinetics. In-situ EIS (Supplementary Figs. 27–29) shows a lower charge transfer impedance in Be-2. The above results show that Be-2 kinetics has been effectively improved. In-situ XRD (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 30a) reveals structural evolution during first cycle (2.0–4.7 V)23. Be-2 exhibits higher Coulomb efficiency (82%) compared to LLOs (73%). During charging (<4.5 V), the (003) peak shifts to lower scattering angle due to the increase of repulsion between lattice oxygen, while the (101)/(104) peaks shift to higher angle due to TM oxidation induced TMO6 unit shrinkage. In the voltage range of 4.5–4.7 V, the (003) peak shifts to higher scattering angles due to the anion oxidation reducing the O–O repulsion. The (101)/(104) peak shifts to lower scattering angles due to expansion of lithium vacancy caused by deep delithium. Be-2 shows smaller cell volume variation (1.2%) than LLOs (1.7%) (Supplementary Fig. 30b, c). 7Li ss-NMR spectra (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 31) confirm that Li⁺ has a higher degree of de-embedding reversibility in Be-2, maintaining the integrity of the superstructure and inhibiting the irreversible OAR process (percentage indicates the amount of Li at that site relative to total Li).

Fig. 5. Structural evolution and kinetic analyses.

a CV profiles at different scan rates from 0.2 to 1.2 mV s−1 of Be-2. b Scan Rate1/2 and current linear fit result of Be-2. c Comparison of GITT between LLOs and Be-2 during the first activation discharge process. d In-situ XRD contour map, cell parameter changes, charge and discharge curves of Be-2. e In-situ Raman contour map of Be-2 and LLOs. f Ex-situ 7Li MAS ssNMR spectra of LLOs during the first activation cycle. Corresponding percentages were obtained from peak area ratios. g Energy barrier analysis of different TM migration processes.

In-situ Raman (Fig. 5e) reveals the evolution of the structure46. The peaks at 600 and 480 cm−1 correspond to νMO6 vibrations (A1g mode) and δO-M–O vibrations (Eg mode), respectively, which are attributed to Li2MnO3 (C2/m). The spectral peak at 410 cm−1 corresponds to a short-range ordered honeycomb superstructure. The spectral peak at 510 cm−1 is the characteristic of Ni oxidation. During charging, the spectral peak of LLOs located near 480 cm−1 shifted to lower wave number, which is attributed to the oxidation of TM and the increase in the lattice parameter c. At high voltage, the spectral peak located near 600 cm−1 shifts to higher wave numbers, which is attributed to the irreversible migration of Mn to the Li sites in the AM layer, leading to the transition of the layered structure to spinel structure. At the same intensity contrast, for LLOs, Be-2 shows better crystallinity throughout the charge/discharge process. Notably, the higher reversibility of the ordered honeycomb superstructure in Be-2 suggests that the ordered superstructure remains stable at high voltage, the anionic energy level is more stable, and the OAR process is more reversible. In addition, Be doping increases TM migration energy barriers (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Figs. 32, 33), inhibiting structural disordering and deterioration at high voltage.

Reductive coupling mechanism DFT calculation analysis

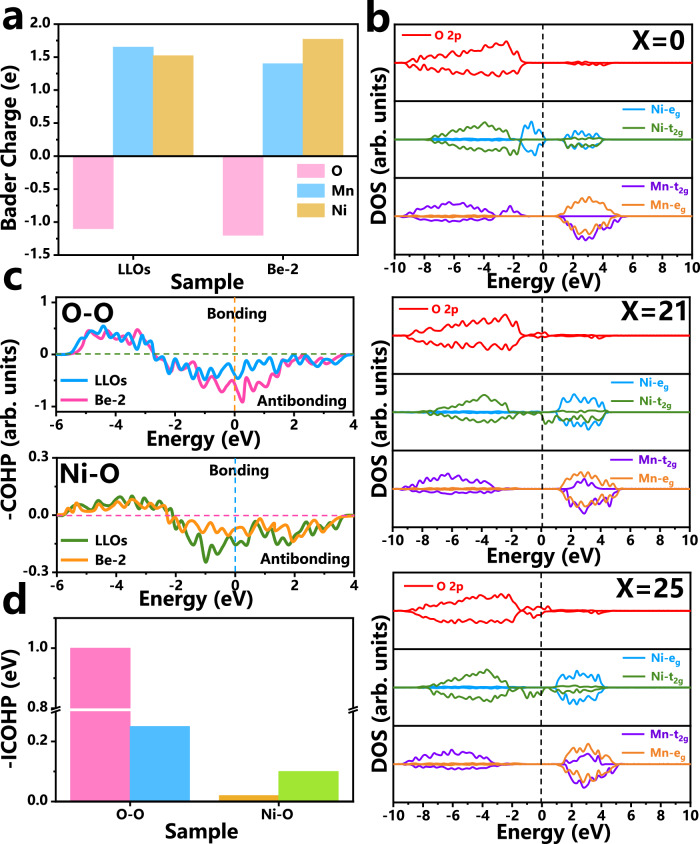

Bader charge analysis reveals that Be doping reduces Mn valence, increases Ni valence, and O obtains more electrons, which excites the Ni/Mn-O electronic interaction (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 34). Electronic structures of Mn/Ni/O in LLOs and Be-2 at different delithiation states are shown in Fig. 6b. In Be-2 and LLOs, as charging progresses (X = 21), the density of states (DOS) of Ni-eg orbitals decreases below the Fermi level and increases above it, indicating electron loss for charge compensation. Simultaneously, Ni/Mn-t2g orbitals in Be-2 show similar changes, while LLOs exhibit no significant change in t2g orbitals. At X = 21, the O 2p orbitals display DOS near the Fermi level, indicating partial anion oxidation at low voltage. At high voltage (X = 25), the O 2p DOS of Be-2 increases further near the Fermi energy level, corresponding to further oxidation of the anion, while Ni-t2g orbitals show increased occupied states below the Fermi level, indicating Ni reduction. In contrast, LLOs show only O 2p orbital changes at high voltage, without significant t2g or eg orbital changes. These results demonstrate mixed Ni/O oxidation in Be-2 and the reductive coupling mechanism between Ni-t2g and O 2p orbitals.

Fig. 6. DFT analysis of reductive coupling mechanism.

a Bader charge analysis of LLOs and Be-2. b DOS of Li29-xMn13Ni6Be1O48 (X = 0, 21, 25) supercells. c Ni-O and O–O COHP distributions of LLOs and Be-2 at X = 25, and (d) corresponding ICOHP values.

In OLi2TM4, the eg orbitals are higher in energy than O 2p, leading to preferential oxidation of TM (a1* and b2* orbitals) at low voltage (Supplementary Fig. 35a). The energy level of t2g is lower than that of O 2p, but t2g has a smaller energy level difference with O 2p relative to the eg. In LLOs, the low energy of Ni-t2g results in b1* molecular orbitals dominated by O 2p, with weak π-type interactions and non-bonded O 2p near the Fermi level, and charge compensation at high voltage is mainly provided by anions, causing irreversible OAR at high voltage. In Be-2, Ni-t2g orbitals strongly hybridize with O 2p, b1* molecular orbitals are co-occupied by t2g and O 2p (more TM properties), thus stabilizing the OAR process (Supplementary Fig. 35b)27. According to Mott-Hubbard theory, the (M–O)* (b1*) band splits into upper (UHB) and lower (LHB) Hubbard bands after TM oxidation3. Since the b1* orbital in Be-2 is occupied by the co-occupation of the t2g and O 2p orbitals, the LHB and O 2p are located at similar energy level, which results in the formation of reductive coupling mechanism (Supplementary Fig. 35c, d). COHP calculations (Fig. 6c) reveal stronger Ni-O bonding and weaker O–O bonding in Be-2 at X = 25, with high-ICOHP values confirming strong Ni-O interactions and stable Ni-(O–O) conformations (Fig. 6d)49. Charge density analysis further shows that Ni in Be-2 has a higher degree of charge delocalization, which reflects a stronger Ni-O bond (Supplementary Fig. 35e, f).

Failure analysis after long cycles

The material was analysed after long cycles and the LLOs exhibited severe structural degradation with crushed particles, spinel/amorphous phase formation, and thick CEI layers (Supplementary Figs. 36b, d, f and 37). In contrast, Be-2 maintains structural and interfacial stability (Supplementary Figs. 36a, c, e and 37). TOF-SIMS (Supplementary Fig. 38) shows oxygen related decomposition products (LiCO3−, LiF2−, POF2−) on LLOs, indicating continuous O2 release. Be-2, with a thinner CEI, demonstrates a more stable anionic environment, inhibiting oxygen species attack. Raman and XRD (Supplementary Fig. 39a, b) results confirm Be-2 retains larger layer spacing, high crystallinity, and less structural disorder after long cycles23,46. XPS reveals lower lattice oxygen loss and irreversible oxygen species in Be-2 (Supplementary Fig. 39c). Mn valence remains stable in Be-2, ensuring highly reversible anionic redox and avoiding low-voltage redox activation or structural collapse (Supplementary Fig. 40). EIS and GITT results (Supplementary Fig. 41) show Be-2 has lower charge transfer impedance and good kinetics. The above results indicate that Be-2 has good structural stability and more reversible OAR process during the early drastic structural transformation and long cycle.

Performance analysis of Si/C||Be-2 and Si/C||LLOs cells

To explore the practical applicability of Be-2, Si/C||Be-2and Si/C||LLOs cell were constructed using Si/C as the anode. The Li||Si/C cell performance is shown in Supplementary Fig. 42. The voltage window and the anode to cathode mass ratio were determined from the CV and charge/discharge curves of the anode and cathode (Fig. 7a, b). The charge/discharge curves of the first cycle are shown in Fig. 7c, and Be-2 maintained a high discharge capacity (295.5 mAh/g) and Coulombic efficiency (89%). After 100 cycles under 1 C (60 min, 250 mA g−1) of Be-2, the capacity retention is 87% and the discharge average voltage retention is 93% the capacity and voltage decay is only 0.29 mAh/g and 2.4 mV per cycle (Fig. 7d, e). In addition, the rate performance at 0.1 C (600 min, 25 mA g−1) and 10 C (6 min, 2500 mA g−1) is 268 mAh/g and 155 mAh/g, respectively (Fig. 7f), with good kinetics. It is worth noting that due to the improved material kinetics, the Si/C||Be-2 cell works well at low temperatures (90% capacity retention at −20 °C compared to 30 °C, Fig. 7g). Above results show that Be-2 has certain potential for application.

Fig. 7. Si/C||Be-2 and Si/C||LLOs cells.

a CV curves of Li||Si/C and Li||Be-2. b Charge/discharge curves of Li||Si/C and Li||Be-2. c Initial charge/discharge curves at 0.05 C (1200 min, 12.5 mA g−1). d cycling performance. e Voltage fading. f Rate performance. g Specific capacities at different temperatures under 1 C.

Discussion

In summary, superexchange interaction precisely regulates Ni/Mn spin states, enabling strong hybridization between Ni-t2g and O 2p orbitals. Activation of Ni-t2g generates electron holes, triggering the reductive coupling mechanism. Strong Ni-t2g/O-2p interaction form stable Ni-(O–O) configuration, inhibiting O2 release and enhancing anionic reversibility. Be-2 exhibits good electrochemical performance, with 93% capacity and 94% voltage retention after 400 cycles at 1 C (60 min, 250 mA g−1), with capacity and voltage decay of only 0.04 mAh/g and 0.5 mV per cycle. The anionic kinetic is enhanced due to the cationic redox mediation, with a discharge capacity of up to 187 mAh/g at 10 C (6 min, 2500 mA g-1). XPS, XES, and XLD confirm strong Ni-O-Mn superexchange in Be-2. Ex-situ XAS, XANES, and EPR reveal charge compensation mechanisms for different TM spin states. In-situ XRD and Raman demonstrate that Be-2 has lower cell volume and phase composition changes. GITT, CV, and in-situ EIS demonstrate good kinetics for Be-2 due to reductive coupling. DFT calculations show Ni-t2g/O-2p hybridization and reductive coupling mechanism. Si/C||Be-2 cells and all-weather performance demonstrate its broad application potential. This research provides a way to precisely regulate the anionic and cationic redox chemistry and an idea for the design of lithium-ion cathode materials with high specific energy and long cycle life.

Methods

Synthesis of samples

NiSO4 6H2O (99.5%, Macklin) and MnSO4 H2O (99.5%, Macklin) with approximate solubility product constants were dissolved in deionized water according to the corresponding molar ratio to make a 2 mol/L sulphate solution. The strong base KOH (90%, Macklin) was used as the precipitant, and an appropriate amount of ammonia was added as buffer and complexing agent to make a 4 mol/L base solution. Then the sulphate solution and the alkali solution were added dropwise to a three-neck flask, and the water bath temperature was kept at 60 °C, pH was controlled at about 12, and an inert atmosphere was passed to protect the metal ions from oxidation. After reacting for 5 min, the precipitate was quickly transferred to a filtration device to wash and filter, then dried under vacuum at 120 °C to obtain the metal hydroxide precursors. The precursor was dosed with the corresponding stoichiometric ratio of LiOH H2O, 5 wt% excess (99.9%, Macklin), fully ground, and then calcined in a muffle furnace, first at 450 °C for 5 h, and then at 900 °C for 18 h, with a heating rate of 5 °C/min. Finally, the specimen was rapidly cooled at room temperature to produce the original lithium-rich material Li1.2Ni0.2Mn0.6O2, which was recorded as LLOs. In order to prepare Be-modified LLOs, BeO (99.9%, Macklin) was added during the sintering process, and the amount of Be added was Li1.2Mn0.6Ni0.2BexO2, X = 0.01, 0.03, and 0.05, named Be-1, Be-2, and Be-3, respectively.

Material characterization

The crystal structure of the samples was analyzed using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, PANalytical PW 3040-X’Pert Pro) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), employing a scanning range of 10°-90° and a sweep rate of 2°/min. The surface morphology was examined by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, Zeiss SUPRA 55), while the nanoscale microstructure was analyzed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL-JEM 2100 and TECNAI-G2 20). To determine the phase composition, the vibrational characteristics of the structure were recorded by Raman spectroscopy (LabRAM HR Evolution, HORIBA). Additionally, the surface chemical states and compositional distribution of elements were quantitatively characterized by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, PHI Quantera II SXM system) equipped with an Al Kα radiation source. The differential electrochemical mass spectroscopy (DEMS) (Linglu Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was carried out to detect the gas evolution during charging, and the battery were tested at a current density of 25 mA g−1 using LAND CT2001A. X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) tests of Ni and Mn were performed at the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF), and XAS measurements at the O K-edge were collected by fluorescence and total electron yield (FLY and TEY) mode. Processing was performed with the Demeter software package. The XLD signal is obtained by subtracting the intensities of the linear-polarized photons with vertical (Ic) polarization from that obtained with horizontal (Iab) polarization without magnetic field, i.e., XLD = (Iab − Ic)/(Iab + Ic). The magnetic susceptibility was measured by a MPMS-3 SQUID magnetometer (Quantum Design) in the temperature range 2-230 K under an applied field of 1000 Oe. Flourier transformed infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis used an FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS20, USA). For the-in situ XRD test, a special designed mould battery employing BeO as the testing window and Al as current collector was built to monitor in situ reaction during the initial cycle. Each scan was recorded in 0.02° incremental steps between 2θ = 10° and 45°. The charge/discharge test was performed at a current density of 0.2 C (300 min, 50 mA g−1)

Electrochemical testing

The cathode electrode sheet was made by mixing virgin powder, acetylene black (Lorenz) and PVDF (Innochem) dissolved in NMP (99.5%, Macklin) with the mass ratio of 75:15:10. The pulp mixed with the above substances was coated with aluminium foil using an iron bar. The aluminium foil (Shenzhen Kejing Star Technology Co., Shenzhen) exhibited a thickness of 10 μm with a purity exceeding 99.35%. Subsequently, the samples were subjected to vacuum drying at 80 °C for 12 h4. A coin type CR2032 cell was assembled in a glove box filled with argon gas (H2O and O2 is less than 0.1 ppm). The electrolyte was 1 M LiPF6 dissolved in ethylene carbonate (EC) and ethyl methyl carbonate (EMC) (VEC:VEMC = 1:1) (dodochem), packed in aluminium cans, stored in glove box and taken with dropper. The active material mass, diameter and thickness were 2–3 mg/cm2, 12 mm and 20–30 μm. The purity of the Lithium chip (Tianjin Zhongneng Lithium Co., LTD) is more than 99.95% and the thickness and diameter are 1 mm and 15 mm respectively. Lithium chip was the counter electrode and Celgard 2500 membrane was the septum. Constant current charge/discharge tests were performed on a LAND CT2001A instrument with the voltage range of 2.0–4.7 V. The electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) was performed on a VMP2 electrochemical workstation (Princeton Applied Research VersaSTAT3). The cells were held at open-circuit voltage (OCV) for 8 h to stabilise prior to the EIS test, and were subsequently tested at constant potentials from 105 Hz to 5 mHz at an amplitude of 30 mV, 10 data points were collected per decade of frequency. For the galvanostatic intermittent titration test (GITT), the cells were discharged/charged at a constant current (25 mA g−1) for 10 min, followed by 40 min of resting in the open circuit, and data were recorded every 0.01 V change in voltage. The relationship between the potential (E) and the square root of time (τ1/2) in the current pulse region was analyzed, and a linear correlation was observed (Supplementary Fig. 25e, f). The experimental conditions, including a pulse duration (τ) of 600 s, an electrode thickness (L) of 20 μm, and a lithium-ion diffusion coefficient (DLi+) of less than 10−9 cm2 s−1, satisfy the condition τ < <L2/DLi+, confirming the reliability of the calculated DLi+ value50. Cyclic voltammetry test was performed in the range of 2–4.8 V with a scan rate of 0.1 mV/s. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) measurement was conducted to determine the content of oxygen vacancy by a Bruker EMXPLUS instrument with a modulation frequency of 100 KHz. For the Si/C||Be-2 and Si/C||LLOs, the active material mass, diameter and thickness of the cathode were 5–6 mg/cm2, 12 mm and 50–60 μm, respectively; the active material mass, diameter and thickness of the anode were 2–3 mg/cm2, 12 mm and 20–30 μm, respectively. To ensure complete electrolyte permeation throughout both the separator and electrode materials, all cells were subjected to an 8 h aging process under static conditions prior to electrochemical characterization. Unless otherwise specified, all experimental measurements were systematically performed at 30 °C. The average voltage was obtained by integrating the voltage over time divided by the time. Specific current and specific capacity calculations were based on the mass of the cathode active material. All synthesis and electrochemical experiments were performed independently at least three times to ensure repeatability of results. We chose this cell because its performance was consistent with the results of other cells, showed no anomalies or deviations, and clearly reflected the overall trends and key features of the experiments.

DFT calculation conditions

All first-principles calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) within the framework of density functional theory (DFT)51. The projector augmented wave (PAW)52 method with periodic boundary conditions was employed for Ab initio calculations. Exchange-correlation energies were treated using the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)53 functional. A plane-wave basis set with a kinetic energy cutoff of 500 eV was implemented to ensure computational accuracy, and spin-polarized DFT calculations were conducted under the paramagnetic assumption. Structural optimizations were carried out using a 3 × 3 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh, while a denser 9 × 9 × 1 mesh was utilized for electronic structure calculations54. The convergence criteria were set at 10-5 eV for total energy and 10-4 eV/Å for atomic forces to achieve the required computational precision.

DFT calculation model

We introduced Be in the real material, where Be/TM = 0.0375. First, we used the C2/m space group of the Li2MnO3 phase as the computational base model. Subsequently, Li2MnO3 was expanded to Li32Mn16O48, written as Li24(Li8Mn16)O48. To more closely match the ratio in the Li1.2(Li0.2Mn0.6Ni0.2)O2 material, 3 Li were replaced with Mn in the Li24(Li8Mn16)O48 material to further become Li24(Li5Mn19)O48. Finally, six Mn were replaced with Ni, resulting in Li24(Li5Mn13Ni6)O48, which served as a computational model for the LLOs. To determine the computational model for Be-2, a Be atom was added to model with the chemical formula Li24(Li5Mn13Ni6Be1)O48. Based on the experimental results and in order to significantly highlight the effect of Be on the Ni-O-Mn conformation, the Be atom was placed in the intermediate tetrahedral site of Ni-O-Mn, where Be/TM = 0.052. The number of Be atoms to be added to Li24(Li5Mn13Ni6)O48 is about 0.7125, based on Be/TM = 0.0375 in the real material. Considering the consistency between the model and the real material as well as the reasonableness of the relevant model, we therefore added one Be atom to the model. The atomic coordinates for the optimized structure is provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 51972023 and 52272184 to J.L.).

Author contributions

C.L.Z. conceived the study and performed the characterisation. Y.Q.W. prepared the samples. X.X.Y. and J.L. carried out TEM measurements and analyses. D.Z. conducted XRD analyses. J.Z. performed Raman tests and analyses. X.D.W. provided theoretical calculations. C.L.Z., M.H.C., J.Z., F.Y.K. and J.L.L. wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors added to the discussion and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. C.L.Z., H.C.M., J.Z., F.Y.K. and J.L.L. supervised the work.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Qiong Cai, Jiantao Li and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Source data for this study are provided as a Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Huican Mao, Email: hcmao@ustb.edu.cn.

Juan Zhang, Email: zhangjuan85@ustb.edu.cn.

Feiyu Kang, Email: fykang@tsinghua.edu.cn.

Jianling Li, Email: lijianling@ustb.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-59159-6.

References

- 1.Choi, J. W. et al. Promise and reality of post-lithium-ion batteries with high energy densities. Nat. Rev. Mater.1, 16013 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manthiram, A. A reflection on lithium-ion battery cathode chemistry. Nat. Commun.11, 1550 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assat, G. et al. Fundamental understanding and practical challenges of anionic redox activity in Li-ion batteries. Nat. Energy3, 373–386 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li, Q. et al. Improving the oxygen redox reversibility of Li-rich battery cathode materials via Coulombic repulsive interactions strategy. Nat. Commun.13, 1123 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo, D. et al. A Li-rich layered oxide cathode with negligible voltage decay. Nat. Energy8, 1078–1087 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang, B. et al. Role of substitution elements in enhancing the structural stability of Li-rich layered cathodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 8700–8713 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang, W. et al. Delocalized Li@Mn6 superstructure units enable layer stability of high-performance Mn-rich cathode materials. Chem8, 2163–2178 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu, Z. et al. Gradient Li-rich oxide cathode particles immunized against oxygen release by a molten salt treatment. Nat. Energy4, 1049–1058 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Csenica, P. et al. Persistent and partially mobile oxygen vacancies in Li-rich layered oxides. Nat. Energy6, 642–652 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu, T. et al. Origin of structural degradation in Li-rich layered oxide cathode. Nature606, 305–312 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang, J. et al. Inhibiting collective cation migration in Li-rich cathode materials as a strategy to mitigate voltage hysteresis. Nat. Mater.22, 353–361 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao, T. et al. Understanding the electrochemical properties of Li-rich cathode materials from first-principles calculations. J. Phys. Chem. C119, 28749–28756 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang, A. et al. Ligand-to-metal charge transfer motivated the whole-voltage-range anionic redox in P2-type layered oxide cathodes. Adv. Funct. Mater.34, 2402639 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, Q. et al. Semi-metallic superionic layers suppressing voltage fading of Li-rich layered oxide towards superior-stable Li-ion batteries. Angew. Chem.135, e202309049 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huo, X.-Y. et al. Thermodynamic analysis enables quantitative evaluation of lattice oxygen stability in Li-ion battery cathodes. ACS Energy Lett7, 1687–1693 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearce, P. E. et al. Evidence for anionic redox activity in a tridimensional-ordered Li-rich positive electrode β-Li2IrO3. Nat. Mater.16, 580–586 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li, B. et al. Tuning the reversibility of oxygen redox in lithium-rich layered oxides. Chem. Mater.29, 2811–2818 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li, B. et al. Understanding the stability for Li-rich layered oxide Li2RuO3 cathode. Adv. Funct. Mater.26, 1330–1337 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zuo, Y. et al. Regulating the potential of anion redox to reduce the voltage hysteresis of Li-rich cathode materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc.145, 5174–5182 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacquet, Q. et al. Charge transfer band gap as an indicator of hysteresis in Li-disordered rock salt cathodes for Li-ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc.141, 11452–11464 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang, M. Y. et al. Role of ordered Ni atoms in Li layers for Li-rich layered cathode materials. Adv. Funct. Mater.27, 1700982 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, S. et al. Correlating concerted cations with oxygen redox in rechargeable batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev.53, 3516–3578 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, B. et al. Decoupling the roles of Ni and Co in anionic redox activity of Li-rich NMC cathodes. Nat. Mater.22, 1370–1379 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu, S. et al. Li-Ti cation mixing enhanced structural and performance stability of Li-rich layered oxide. Adv. Energy Mater.9, 1901530 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, L. et al. Structural distortion induced by manganese activation in a lithium-rich layered cathode. J. Am. Chem. Soc.142, 14966–14973 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu, H.-L. et al. Modulating the voltage decay and cationic redox kinetics of Li-rich cathodes via controlling the local electronic structure. Adv. Funct. Mater.32, 2112394 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okubo, M. et al. Molecular orbital principles of oxygen-redox battery electrodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces9, 36463–36472 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu, E. et al. Evolution of redox couples in Li- and Mn-rich cathode materials and mitigation of voltage fade by reducing oxygen release. Nat. Energy3, 690–698 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cui, T. et al. Facilitating an ultrastable O3-Type cathode for 4.5 V sodium-ion batteries via a dual-reductive coupling mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc.146, 13924–13933 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng, J. et al. Role of superexchange interaction on tuning of Ni/Li disordering in layered Li(NixMnyCoz)O2. J. Phys. Chem. Lett.8, 5537–5542 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, G. et al. Spin crossover and exchange effects on oxygen evolution reaction catalyzed by bimetallic metal organic frameworks. ACS Catal14, 8652–8665 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, Q. et al. The oxygen-rich beryllium oxides BeO4 and BeO6. Angew. Chem.128, 11021–11025 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taha, T. A. et al. Green simple preparation of LiNiO2 nanopowder for lithium ion battery. J. Mater. Res. Technol.9, 7955–7960 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunia, K. M. et al. Preparation and characterization of BeO-supported feldspar. Porcelain. Iraqi J. Sci.57, 404–413 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo, J. et al. Triggering cationic/anionic hybrid redox stabilizes high-temperature Li-rich cathodes materials via three-in-one strategy. Energy Storage Mater.69, 103383 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yin, C. et al. Structural insights into composition design of Li-rich layered cathode materials for high-energy rechargeable battery. Mater. Today51, 15–26 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao, E. et al. Local structure adaptability through multi cations for oxygen redox accommodation in Li-rich layered oxides. Energy Storage Mater.24, 384–393 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bai, Y. et al. Promoting nickel oxidation state transitions in single-layer NiFeB hydroxide nanosheets for efficient oxygen evolution. Nat. Commun.13, 6094 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yao, S. et al. Unlocking spin gates of transition metal oxides via strain stimuli to augment potassium ion storage. Angew. Chem.136, e202404834 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu, Y. et al. Analysis of x-ray linear dichroism spectra for NiO thin films grown on vicinal Ag(001). Phys. Rev. B78, 064413 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lan, D. et al. Interfacial electronic and magnetic reconstructions in manganite/titanate superlattices. Adv. Mater. Interfaces.11, 2300903 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, Y. et al. Pressure-driven cooperative spin-crossover, large-volume collapse, and semiconductor-to-metal transition in manganese(II) honeycomb lattices. J. Am. Chem. Soc.138, 15751–15757 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He, Y. et al. Entropy-mediated stable structural evolution of Prussian white cathodes for long-life Na-ion batteries. Angew. Chem.136, e202315371 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng, Y. et al. Insights into the Jahn-Teller effect in layered oxide cathode materials for potassium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater.14, 2400460 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 45.House, R. et al. The role of O2 in O-redox cathodes for Li-ion batteries. Nat. Energy6, 781–789 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luo, K. et al. Charge-compensation in 3d-transition-metal-oxide intercalation cathodes through the generation of localized electron holes on oxygen. Nat. Chem.8, 684–691 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gent, W. E. et al. Coupling between oxygen redox and cation migration explains unusual electrochemistry in lithium-rich layered oxides. Nat. Commun.8, 2091 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kawai, K. et al. Kinetic square scheme in oxygen-redox battery electrodes. Energy Environ. Sci.15, 2591–2600 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen, C. et al. Enhancing the Reversibility of Lattice oxygen redox through modulated transition metal-oxygen covalency for layered battery electrodes. Adv. Mater.34, 2201152 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weppner, W. et al. Determination of the Kinetic Parameters of Mixed‐Conducting Electrodes and Application to the System Li3Sb. J. Electrochem. Soc.124, 1569 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qian, M. et al. 1D hybrid consisting of LiTi2(PO4)3 with highly-active (113) crystal facets and carbon nanotubes: A bidirectional catalyst for advanced lithium-sulfur batteries. Chem. Eng. J.505, 159727 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perdew, J. P. et al. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett.77, 3865 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blöchl, P. E. et al. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B50, 17953–17979 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Henkelman, G. et al. Improved tangent estimate in the nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths and saddle points. J. Chem. Phys.113, 9978–9985 (2000). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Source data for this study are provided as a Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper