Abstract

Introduction:

This paper draws on a study and its findings that set out to explore why some students appear to thrive, turning placement experiences into positive empowering opportunities despite the challenges, where others may not. Findings established a broader application beyond placements to inform curriculum design and delivery that nurtures professionalism, competence and identity from pre-admission to transition into practice as a journey of growth and development.

Method:

A mixed-methods approach was adopted. Questionnaires and interviews gathered data from two cohorts in traditional (n = 25) or role-emerging placements (n = 13). An interpretive approach was employed for the qualitative data. The quantitative data underwent statistical analysis.

Findings:

Students in role-emerging placements scored higher in resilience prior to and developed greater resilience as a consequence. These students scored higher in traits of openness, conscientiousness, extraversion and agreeableness and were more emotionally stable compared with students in traditional placements. Agreeableness was positively correlated with greater resilience in these students.

Conclusion:

Curricula design and delivery should embed opportunities throughout programmes of study enabling students to nurture an openness to new experiences, with positive risk taking, building an ability to thrive. Understanding individual differences in students informs the development of competence and identity pivotal for transition into practice.

Keywords: Resilience, individual difference, personality, occupational therapy, placements, role-emerging, entrepreneurship

Introduction

Occupational therapy, within a complex and changing world of healthcare, requires practitioners to be competent, hold a strong sense of professional identity and an ability to thrive (Gray et al., 2020). Furthermore, the profession is driving a shift towards diversification where the need for a stronger occupational focus creates a catalyst through which to shape the practice arena developing the scope of the occupational therapy role (Kantarzis, 2019). The profession is positioned to drive these changes allowing practitioners to step aside from the constraints of traditional roles, strengthen beliefs and values in occupation, as a powerful enabler of health and well-being through creative service delivery (Creek and Cook, 2017).

Role-emerging placements, undertaken by some students studying in the United Kingdom (UK), are known to serve as a vehicle to open up opportunities in diverse settings, with potential to build a greater sense of professional identity and competence through occupation (Thew et al., 2018). The study explores the aptitude and attributes for successfully navigating these more challenging placements, where some students demonstrate a propensity to thrive, with findings establishing that beyond placements there is a broader application. The constructs of individual difference or personality, resilience and entrepreneurship are used to seek understanding of this from a student perspective.

The study adopts an inductive approach through a mixed-methods design and is framed within three research objectives addressing the three constructs that when combined and synthesised as an entirety elucidates a depth of understanding unachievable by exploring these as singular elements. The study aimed to explore why some students may be deemed more suited to role-emerging placements with a propensity to thrive, turning the challenges into a positive and empowering experience, enhancing competence and identity? It explores how challenges are overcome, whilst creating a positive legacy, optimising perceptions of the profession achieved through the student’s attributes, mindset and professionalism. Students in role-emerging experiences, compared to traditional placements, were found to be more open to new and challenging experiences. They were more diplomatic and able to navigate their way through the challenges, being more emotionally stable and conscientious. Higher levels of extraversion suggest a social confidence and optimism in these students.

Findings, whilst borne out of the data gathered from placement experiences, established a broader application beyond placements that serve as a catalyst to inform curriculum design and delivery that nurtures professionalism, competence and identity from pre-admission to transition into practice as a journey of growth and development. This paper presents the findings from this wider perspective being of value to education providers. It presents the study undertaken from a UK perspective and subsequent recommendations through a model framework outlining the scope and application for practice. The need for all students to understand their own traits, personal enablers (Brown et al., 2017) and challenge or hindrance stressors (Flinchbaugh et al., 2015), brings insight into their personal and professional development needs. Universities play a pivotal role in supporting students in their development, shaping them into practitioners who can thrive. Curriculum delivery and placements facilitate student development beyond skills and knowledge to help them to understand what is expected of them as a professional, adopting behaviours through self-awareness of their own traits and attributes (Childs-Kean et al., 2020; Mason et al., 2015). The opportunities afforded by the wider student experience creating a sense of belonging, such as student societies are also known to support the building of resilience and identity (Bleasdale and Humphreys, 2018).

Literature review

The literature review, an iterative process, focuses on four elements comprising of practice education, resilience, individual difference and entrepreneurship that inform the aim and objectives (Box 1) of this study and the key search terms utilised.

| Box 1: Objectives: To explore the construct of resilience and how this allows a student to thrive in a role-emerging placement compared with those in traditional placements To establish if students’ personality traits are correlated to appropriate allocation and optimises outcomes in a role-emerging placement compared to traditional placement allocation To ascertain how the entrepreneurial mindset can be of value to occupational therapy students undertaking role-emerging placements |

The occupational therapy profession acknowledges the fundamental purpose that practice education serves in the training of students (Beveridge and Pentland, 2020). Placements are embedded throughout the duration of study, amounting to a total of 1000 hours minimum of experiential learning (World Federation of Occupational Therapists, 2016). Placements are pivotal to the development of a well-trained, adaptable workforce who can deliver high-quality services and respond to rapidly changing healthcare agendas. The requisite professional behaviours and identity are typically nurtured through professional socialisation, as a consequence of being immersed in placement experiences (Gray et al., 2020).

In the UK, allocation of students to placements falls under the remit of the education provider, guided by a tutor with responsibility for practice education (Royal College of Occupational Therapists, 2019). The processes that facilitate the placement allocation are bound in local contexts and are expected to meet the need for wide ranging placement experiences across sectors. Placements fall into key categories or models of provision (Beveridge and Pentland, 2020) in either statutory health and social care services, known as role-established or traditional placements. Alternatively, they are established as non-statutory placements encompassing the charitable or third sector, often termed as role emerging, where profession-specific supervision is provided through a long-arm model (Beveridge and Pentland, 2020). The occupational therapy profession has been pivotal in the development of these innovative placements (Kyte et al., 2018) that are evidenced as being more challenging in nature (Clarke et al., 2015; Hunter and Volkert, 2016). Students are typically allocated to mainstream placements in the earlier stage of training, where role modelling through professional socialisation and on-site supervision supports the student in their development of knowledge, skills and building competence. Gray et al. (2020) conclude that second year students can still be struggling to form their professional identity, supporting the concern that not all students would cope with a role-emerging placement and that timing of undertaking these is important. Consequently, allocation to non-traditional placements usually falls in the latter stages of training as students gain competence (Linnane and Warren, 2017). Students may undertake these on a compulsory basis or through choice, dependent on the programme design and expectations. The role-emerging placement, evidenced as being challenging demands a greater level of autonomy and professional identity, as students scope the potential for practice and arguably, requires higher levels of resilience with an entrepreneurial mindset and attributes that nurture a propensity to thrive. The existing literature reviews the nature of placements (Beveridge and Pentland, 2020) and the impact on students through resilience (Brown et al., 2019), emotional intelligence (Gribble et al., 2018) and professional identity (Thew et al., 2018). This study builds on current evidence to explore the nature of the students, their traits or characteristics and aptitude to thrive in these more challenging placements. It also adds to the body of evidence on coping strategies for students in these placements (Clarke et al., 2019) and modes of development to nurture identity, professionalism, resilience and entrepreneurship within curriculum delivery more broadly.

To understand the nature of individual difference in students a review of literature in personality pertaining to trait theory and the five-factor lexical model was undertaken (McCrae and Costa, 2003). The five factors identified by this model are openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism (or emotional stability). Referred to as the Big-Five, each trait and associated characteristics are held to a greater or lesser extent by individuals allowing for individual difference and are argued to be fixed as inherent and stable over time (Cobb-Clark and Schurer, 2012). These traits are operationalised into scales to measure personality, subsequently used for quantitative data collection, and therefore relevant to exploring the nature of students and why some have a propensity to thrive.

Fleeson and Jayawickreme (2015) argue both a trait and social cognitive approach or whole trait approach articulates individual differences and how people interpret situations and change behaviour according to the context. Expectations, competencies, self-regulation and goals influence and explain variability, therefore suggesting students can learn to adapt and shape their behaviours in environments including placements. Development theories explore how personality develops through interaction with our environment, allowing for learning and insight, with motivation driving this through self-regulatory processes. Self-efficacy, a concept within personality theory, argued by Bandura (2012) as a personal resource is evidenced as pertinent for students by Fan et al. (2020). This self-belief allows the effective use of personal attributes to achieve a desired outcome and to pursue challenging tasks. This cognitive perception of competence and self-confidence with a context-specific judgement of capability to perform a task is therefore pivotal for students on placement (Hughes et al., 2011).

Role-emerging placements are known to require resilience, creativity and innovative practice as students scope the role potential. The nature or characteristics of the resilient or entrepreneurial individual is evidenced across many studies but of relevance are those focused on the pro-social personality. Saebi et al. (2019) suggest that the social entrepreneur displays innovativeness, resourcefulness and a propensity to take risks, whilst also adopting compassion, empathy and concern for the welfare of others. Prosocial behaviours encapsulate altruism, volunteerism and community engagement reflecting desired traits for occupational therapists. Individuals with high extraversion and agreeableness are more likely to seek out socially driven opportunities with an ability to foster social consensus. The dominating trait of agreeableness facilitates appreciation of social responsibility, positively impacting on social vision and innovation driving social change (Caprara et al., 2012; Hocking and Townsend, 2015). Equally, Creek and Cook (2017) discuss enabling characteristics that allow practitioners to work effectively in marginal settings, mirroring role-emerging placements and a need for agency, openness, commitment, responsiveness and resourcefulness.

Professional attributes and behaviours must be demonstrated in all placements but arguably, more so in role-emerging placements as students navigate their way through the myriad of challenges (Clarke et al., 2019). Lecours et al. (2021) suggest that professionalism is a complex competence, defined by distinct attitudes and behaviours forged through personal and environmental characteristics. However, Childs-Kean et al. (2020) suggest that attitudes can be more difficult to nurture, with professional attributes coming more naturally to some individuals than others. Arguably, used as a reason for allocation of students who hold the requisite attributes to role-emerging placements. Professional behaviours, qualities held by individuals and assessment of these professional values at admission are reported by McGinley (2020) as being non-cognitive, in contrast to cognitive or academic ability. Psychometric testing of candidates prior to admission, to seek those who hold appropriate values and attitudes, whilst acknowledged, is not advocated due to limited evidence in use of scales measuring professionalism (Mason et al., 2015). Thomas et al. (2017) explore the use of the multiple mini-interview (MMI) in preference to traditional methods, to select those individuals who will excel in occupational therapy education, holding desired professional attributes and qualities for personal growth and development. Whilst supporting the value of MMI to judge these desired characteristics, the lack of robust evidence advocates a need for further research to examine psychometric properties and values aligned to the circuit of multiple stations and what they aim to determine in candidates.

Evidence, shaping the understanding of resilience borne out of early childhood adversity studies (Rutter, 2012) suggests resilient individuals are understood as adaptive, informed by individual circumstances and characteristics (Connor and Davidson, 2003). Resilience and thriving reflect a capacity for positive adaptation, growth and transformation, with a cognitive shift in response to challenge to reconstruct meaning (Brown et al., 2017) suggest personal and contextual enablers can foster an ability to thrive in individuals. Within higher education the need for resilience in student communities is recognised, with responsibilities falling on universities to nurture this (Bleasdale and Humphreys, 2018). Developing resilience and an ability to cope and thrive by preparing student practitioners for the reality of clinical roles is increasingly embedded in curriculum delivery, with a fundamental requisite remit for fitness to practice through a robust workforce. However, Kunzler et al. (2020) in a Cochrane review of psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare students suggest little confidence in findings that interventions improve resilience outcomes or reduce anxiety or stress and long-term implications were not established suggesting the need for more evidence.

Method

Design

A mixed-methods approach was adopted as a pragmatic and practical means to address the research aim gathering both narrative and statistical data bringing breadth and depth to the analysis (Biddle and Schafft, 2015; Molina-Azorin and Fetters, 2019). The study utilised a convergent design with a deliberate and cohesive combination of collection, analysis and integration of both types of data (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2018). The qualitative method carried greater dominance in this study, generating rich data exploring student perspectives of placement experiences, with the statistical data and findings supporting this. The data on the same subject is different yet complimentary with a synthesis of the qualitative and quantitative analysis and to compare or combine findings. This corroboration of the evidence produces a deeper understanding of the research problem.

Participants

Following ethical approval, participants were recruited from a BSc pre-registration programme, using an inclusion criterion (Box 2), prior to undertaking their third or final placement across traditional and role-emerging settings. The normal process of allocation by the placement tutor aligned students to specific experiences and their profile.

| Box 2: Inclusion criterion: Enrolled on BSc (Hons) occupational therapy programme Either in their second or third year of study Had undertaken placements in traditional or role-emerging placements |

Adopting a nested design with recruitment of participants from the same population of those used for gathering qualitative data being the same or a subset of those recruited for the quantitative data. The sample was dictated by the cohort sizes negating the need for a power analysis to predict sample size from a population to measure the effect. The quantitative data were collected from two cohorts combined (n = 38), with 13 students allocated to role-emerging placements and 25 to traditional experiences. Of the 13 students undertaking role-emerging placements invited to interview, 6 were randomly selected from those who volunteered to participate.

Data collection

Six semi-structured interviews, conducted on a one-to-one basis were undertaken by the practice education lead in a doctoral research student capacity, each lasting approximately 1 hour. The detailed narrative of the student’s experiences and perspectives of their role-emerging placement experiences was gathered as data. A schedule of pertinent, open-ended questions focused on placement allocation and experiences was utilised and each interview was recorded.

Two psychometric scales were selected based on internal consistency reliability and criterion validity allowing for comparison and correlational analysis and known to be used in health science research (Scott and Mazhindu, 2014). The CD-RISC 25 (Connor Davidson Resilience Scale) (Connor and Davidson, 2003) measures resilience with 25 questions and the Big Five Inventory (John et al., 1991) measures personality traits. The Big Five traits are openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism (or emotional stability) (Costa and McCrae, 2003). Both measurement scales were administered pre- and post-placement with the participant sample of 38.

Data analysis

In mixed-methods research, the quantitative and qualitative data are kept analytically distinct using techniques associated with the type of data. The integrity of each data set is preserved and then capitalised on by integrating the two. The qualitative data were transcribed and thematically analysed (Braun and Clark, 2013). This iterative process was initiated with complete coding to identify pertinent words and phrases vocalised by the participants. These were then refined into sub-themes and themes. The themes are interwoven, to allow the researcher to interpret and make sense of this in a meaningful, yet rigorous and transparent manner.

SPSS was employed to analyse the quantitative data computing the measurement scales and applying scale reliability and correlations. The analysis compares the data measured at time 1 (pre-placement) and time 2 (post-placement) for both role-emerging and traditional placements. The analysis also measures correlations between resilience and personality. Both data sets were integrated to draw conclusions and interpretations from the separate strands as well as across the strands, known as meta-inferences. The convergent design used simultaneous integration to develop findings and interpretations that expand understanding (Creswell and Plano-Clark, 2018).

Rigour

To optimise rigour and trustworthiness in the study, the researcher had to ensure objectivity and transparency throughout the process of and that this was systematic in nature. This was particularly important in the recruitment and data collection phase, as the researcher’s role, and being the practice education lead, could influence and impact on the study findings. A reflexive stance acknowledging potential bias and coercion was adopted throughout, as this study was conducted as insider research (Fulton and Costley, 2019). The use of member and external peer checking was utilised to verify the accuracy of the transcription and coding. The study underwent a full ethical application scrutinised by the research ethics sub-committee of the university and all ethical guidelines were adhered to.

Findings

Whilst this study set out to explore the nature of student allocation and outcomes of role-emerging placements through personality traits and the constructs of resilience and entrepreneurship, findings established a broader consideration of these within curriculum delivery and the student journey in developing professional identity, behaviours and competence. This paper presents the findings from this wider perspective. Demographic data reported in Table 1 outlines the allocation, location of the role-emerging placements and student ages.

Table 1.

Participant data.

| Participant | Age | Gender | Stage of placement | Setting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interview 1 | 43 | Female | Fourth/final year placement | Veterans unit | |

| Interview 2 | 28 | Male | Fourth/final year placement | Mainstream primary school | |

| Interview 3 | 40 | Female | Fourth/final year placement | Mental health drop-in centre | |

| Interview 4 | 28 | Female | Third/second year placement | Detox unit | |

| Interview 5 | 38 | Female | Third/second year placement | Fire and rescue service | |

| Interview 6 | 40 | Female | Third/second year placement | Mental health residential home | |

| Cohort | Placement type | No. of students | Mean age | Median | |

| Student ages for role-emerging and traditional placements (n = 38) | |||||

| Final year cohort | Role-emerging | 6 | 33.3 | ||

| Traditional | 12 | 33.4 | |||

| Second year cohort | Role-emerging | 7 | 37.8 | ||

| Traditional | 13 | 33.0 | |||

| Combined cohorts | Role-emerging | 13 | 35.7 | 38 | |

| Traditional | 25 | 34.2 | 33 | ||

Seven key themes (Box 3) emerged from the qualitative data, informed by interrelated sub-themes outlined below and depicted in Figure 1 as a dynamic image of the complex nature of these placements and student experience:

|

Box 3: Emergent themes and (sub-themes)

Multi-faceted nature of allocation (selection process, compulsory allocation versus choice, stage of training) Expectations (anticipation of placement experience, impact of setting, influencing change) Determining traits, aptitude and attributes (identified traits/attributes, building resilience) The highs and lows – impact of placement on the student (autonomy, facing adversity/roller coaster, positive impact and personal growth) Creating legacy (positive legacy, negative legacy, preparing you for practice, shaping career paths, shaping the profession/diversity) Occupation and practice (developing identity, professionalism, scope of practice, valuing occupation) Resources and support mechanisms (coping strategies, peer support, supervision) |

Figure 1.

Thematic model: the dynamics of role-emerging placements with core constructs of resilience, entrepreneurship and personality.

Theme 1: Multi-faceted nature of allocation

Understanding the aptitude, strengths and needs of individual students was perceived by participants as pivotal to successfully assigning students to placements. Deliberate selection using a personal approach, afforded by small cohorts, requires an understanding by the tutor to match a student to a suitable placement setting and was deemed a strength. This also requires knowledge of the demands of placements and in considering the requisite aptitude and attributes for placements across varying levels of perceived challenge, particularly with role-emerging experiences. Participants were able to identify their own aptitude, traits and resilience as a reason for selection to role-emerging experiences and equally identified why some students would find these experiences more difficult to cope with, potentially being set up to fail. Findings indicated a need for assertiveness, open-mindedness, confidence and resilience. Equally, a sense of professional identity and professionalism emerged from the data, with over-confidence and lack of self-awareness being identified as having the potential for a negative impact on the host organisation, the education provider and the profession more widely.

The university does not offer students a choice of placement, using a compulsory model of allocation, with findings suggesting there are pros and cons to this. Four of the six participants, if given a choice, would not have opted for a role-emerging placement, suggesting a lack of self-belief, confidence and openness to this type of experience preferring the comfort of a traditional placement. Compulsory allocation brings a sense of fait accompli and being resigned to what they faced with a determination to get through. Others described ‘grabbing the opportunity and to prove to myself’. Equally, being selected and deemed to be able to cope with more challenging placements served to boost self-belief, as the student perceives that the tutor had confidence in their ability to thrive. Findings also suggest that these challenging experiences should be open to all students as opportunities to develop confidence, resilience and personal growth and that selective allocation may disadvantage students deemed to be less suited.

Theme 2: Expectations

Findings indicate the challenging nature of some placements, typically those of a role-emerging nature require attributes and traits to overcome resistance, cultural differences and barriers faced by students. Diplomacy and gaining trust of those they worked alongside strongly emerged and participants described winning staff over as they introduced occupational therapy within resistant teams. The student narratives indicate how they dealt with these challenges using strategies and adapting their approach navigating their way through. Whilst placements are compulsory in nature, the university allows students to express areas of interest. Where this could be fulfilled in the placement allocation, serves to motivate and brings an enabling strategy or challenge stressor for coping and turning the placement into a positive.

Theme 3: Determining traits, aptitude and attributes

All participants identified traits and attributes perceived as necessary for any student undertaking a challenging placement. The intuitive nature of individuals and difficulty in teaching professionalism suggests inherent traits; characteristics and personal qualities being key to successful allocation and outcomes. Adaptability, being willing to change and fit in to make it work was evident. All participants perceived themselves as assertive and ‘being able to hold their own’ with a voice to articulate and embed the role, suggesting a strong professional identity as a requisite. Being autonomous was deemed essential as an attribute. Participants recognised the need for creativity, resourcefulness and innovation, aligned to the ability to problem solve. Determination, self-efficacy and self-belief emerged strongly from the data. Diligence, dependability and reliability were evident, alongside the need of diplomacy that demands intuitive sensitivity, insight and self-awareness.

The intrinsic motivation and internal rewards that result in a passion and satisfaction shaped how a student approached and perceived their placement. Participants viewed themselves as resilient and deemed this as a vital attribute to cope with the challenges of role-emerging placements. They reported developing resilience as a consequence by not just surviving but that they ‘embraced it and lived it’ and ‘grown so much because of it’. The students reflected on how previous experiences and challenges help to shape and determine their resilience. Equally suggesting not all of their peers demonstrate resilience and would struggle, questioning suitability of placing students in these placements. Age, maturity and life experience were deemed to be factors to build resilience allowing the students to thrive, providing personal enablers.

Theme 4: Highs and lows – Impact on the student

One participant reported the placement to be ‘the ultimate autonomous experience’ building confidence and self-belief for becoming a graduate practitioner. In contrast to valuing autonomy, participants recognised that a structured environment brought reassurances, therefore suiting some students more. The role-emerging placement experiences push students out of their comfort zone with a roller coaster of ups and downs as they navigate the placement. Feelings of apprehension and being daunted were expressed but students faced this and the sense of having been through a journey was clearly evidenced. The role-emerging experience was reflected as ‘transformative’ in nature and helped students to prepare for practice through personal and professional growth aligning to developing resilience.

Theme 5: Creating legacy

Role-emerging placements have the potential to create both negative and positive legacy. A student with a ‘gung-ho’ approach, being unintentionally destructive, who lack attributes such as diplomacy and diligence can be detrimental to the placement experience and outcome. A lack of professionalism and competence not only has the potential to reflect poorly on the student but the profession more broadly. One participant talked of ‘not burning bridges with partners’ impacting on future placements and the importance of representing the profession and university, even to the extent of suggesting it ‘being quite dangerous to put some people in’.

Equally, findings suggest the positive impact the students bring and value in the changes they embed. The role-emerging placements can shape career paths, opening up networks and different options. These experiences align with diversification of the profession, as new areas of practice are explored and supports entrepreneurial thinking and creativity.

Theme 6: Occupation and practice

Students view these placements as a mode to develop and consolidate professional identity and use of occupation in practice. Without on-site professional specific supervision, students develop a greater sense of professional identity. All participants had a sense of this being pivotal as a consequence of undertaking role-emerging placements. These placements also brought professional isolation and students reported missing the camaraderie of being in a team with occupational therapy colleagues. The value of occupation strongly emerged from the data informing the scope of practice and underpinning theory base. Students holding a strong professional identity, typically in the latter stage of training, are deemed more likely to be allocated and succeed in role-emerging placements. Equally, these experiences can serve as a platform to develop a greater sense of this, with timing of allocation within a programme of study being pivotal to aid and enrich this development.

Theme 7: Resources and support mechanisms

Coping strategies, enablers and challenge stressors are vital to build resilience. Findings indicate these ranged from practical strategies to consciously changing thought processes to deal with situations and using ‘the inner voice’ or ‘step-by-step’ approach. Students required supportive networks to share concerns or ideas through peer support or significant others. Those on shared placements particularly valued this. The students reported the importance of their long arm supervisor placing high expectations on them whilst also being protective of them as they navigated their placement journey.

Quantitative results

The results of this study indicate a strong internal consistency of the psychometric tests employed. Table 2 presents the scale properties for both types of placement experience. Equally, criterion validity is evident allowing comparison and correlational analysis between the two measurement scales. Whilst the quantitative data did not derive statistical significance from the tests that were employed, there was sufficient difference to draw findings suggesting a trend, therefore being of value to the study. Given the focused sample size (N = 38), this is deemed satisfactory for the purposes of correlational analysis that Creswell and Plano Clark (2018) suggest should exceed 30 participants.

Table 2.

Scale properties of traditional and role-emerging placements – time 1 and time 2.

| Scale properties | N | Items | Alpha time 1 | Alpha time 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale properties of traditional placements – time 1 and time 2 | ||||

| Resilience | 25 | 25 | 0.86 | 0.88 |

| Openness | 25 | 10 | 0.63 | 0.69 |

| Conscientiousness | 25 | 9 | 0.79 | 0.80 |

| Extraversion | 25 | 8 | 0.81 | 0.81 |

| Agreeableness | 25 | 9 | 0.80 | 0.87 |

| Neuroticism | 25 | 8 | 0.68 | 0.81 |

| Scale properties of role-emerging placements – time 1 and time 2 | ||||

| Resilience | 13 | 25 | 0.87 | 0.84 |

| Openness | 13 | 10 | 0.79 | 0.80 |

| Conscientiousness | 13 | 9 | 0.88 | 0.79 |

| Extraversion | 13 | 8 | 0.91 | 0.83 |

| Agreeableness | 13 | 9 | 0.75 | 0.85 |

| Neuroticism | 13 | 8 | 0.56 | 0.56 |

T-tests were employed to measure any change over time between pre- and post-placement for students in both role-emerging and traditional placements. Table 3 presents data that measures the constructs of resilience and the five personality traits allowing for comparison between the two sample groups of students pre- and post-placement in traditional and role-emerging placements.

Table 3.

Role-emerging and traditional placements time 1 and time 2.

| Scale | Role-emerging placement | Traditional placement | t | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | |||

| Role-emerging and traditional placements t-test – time 1 | ||||||||

| Resilience | 13 | 74.31 | 9.35 | 25 | 72.84 | 8.98 | 0.47 | NS |

| Openness | 13 | 3.71 | 0.52 | 25 | 3.51 | 0.5 | 1.16 | NS |

| Conscientiousness | 13 | 3.99 | 0.63 | 25 | 3.75 | 0.57 | 1.19 | NS |

| Extraversion | 13 | 3.44 | 0.74 | 25 | 3.18 | 0.66 | 1.12 | NS |

| Agreeableness | 13 | 4.28 | 0.47 | 25 | 4.08 | 0.58 | 1.06 | NS |

| Neuroticism | 13 | 2.66 | 0.48 | 25 | 3.01 | 0.5 | −2.05 | NS |

| Role-emerging and traditional placements t-test – time 2 | ||||||||

| Resilience | 13 | 76.85 | 8.90 | 25 | 72.72 | 10.64 | 1.20 | NS |

| Openness | 13 | 3.79 | 0.51 | 25 | 3.57 | 0.52 | 1.27 | NS |

| Conscientiousness | 13 | 3.97 | 0.57 | 25 | 3.88 | 0.52 | 0.49 | NS |

| Extraversion | 13 | 3.61 | 0.58 | 25 | 3.24 | 0.64 | 1.72 | NS |

| Agreeableness | 13 | 4.24 | 0.58 | 25 | 4.15 | 0.62 | 0.42 | NS |

| Neuroticism | 13 | 2.69 | 0.42 | 25 | 2.90 | 0.64 | −1.03 | NS |

NS: non-significant.

For students in traditional placements, there is no significant difference between time 1 and time 2 indicating that placement makes no impact on resilience for this student group. There is no difference in the five traits of openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism indicating the students were static in their personality traits.

The students demonstrate a higher level of resilience prior to commencing a role-emerging placement compared to the students in traditional placements and developed greater resilience as a consequence of placement. Although results indicate there is no significant difference between time 1 and time 2 for the student sample that had role-emerging placements, students are developing resilience as a result of their placement. This small increase in mean scale scores of resilience suggests a trend and this could be reasoned as being accountable due to a small sample size that may be statistically stronger with a larger sample size.

Students in role-emerging placements scored slightly higher on openness, conscientiousness, extraversion and agreeableness and lower in neuroticism compared to students in traditional placements. There is no significant difference in the five traits of openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism indicating the students were static in their personality traits. Extraversion was measured as being slightly higher post-placement for students in role-emerging placements, which could be attributed to an increase in confidence and personal growth as a consequence of placement.

Table 4 presents the correlations between resilience and the five personality traits for students who have completed either traditional or role-emerging placements. Higher levels of resilience are positively correlated with openness, conscientiousness and extraversion for students in traditional placements. Resilience is negatively correlated with neuroticism. There is no relationship between resilience and agreeableness for these students. Those students scoring higher in openness, conscientiousness and extraversion are likely to have higher resilience. Extraversion scores demonstrate the strongest positive relationship with resilience. The students scoring higher in neuroticism will result in a negative impact on resilience. The correlations between resilience and the five personality traits for students who have completed a role-emerging placement indicate higher levels of resilience are positively correlated with agreeableness to a value of 0.05. The other personality traits are not significantly correlated to resilience.

Table 4.

Traditional and role-emerging placement – time 2 (post-placement).

| Scale | Openness | Conscientiousness | Extraversion | Agreeableness | Neuroticism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional placement – time 2 (post-placement) | |||||

| Resilience CD-RISC 25 | +0.43* | +0.48* | +0.52** | +0.02 | −0.48* |

| Role-emerging placement – time 2 (post-placement) | |||||

| Resilience CD-RISC 25 | +0.20 | +0.16 | +0.11 | +0.58* | −0.40 |

p < 0.05. **p < 0.0

Discussion

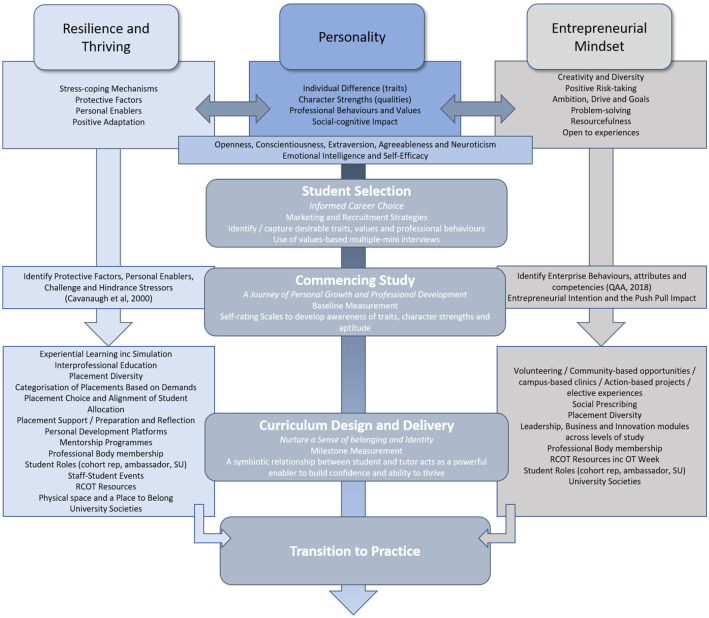

Whilst the findings from this study resonate with earlier studies on practice education and role-emerging placements, the exploration of individual difference, combining with the constructs of resilience and entrepreneurship offers new evidence of value to the profession. This paper focuses on the wider implications of the study within curriculum delivery, enhancing the student journey and development of resilience through personal growth and positive adaptation. Through curricula design and personal development opportunities embedded throughout programmes of study allows students to nurture an openness to new experiences, with positive risk taking, and building an ability to thrive. Understanding individual differences through traits and personal enablers informs the development of professional competence and identity that is pivotal for transition into practice (Thew et al., 2018) (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of the development of professional competence and identity.

Source: Incorporating Challenge-Hindrance stressors (Cavanaugh et al., 2000).

Establishing individual differences and desired attributes

Universities utilise different strategies and processes in recruitment, allowing selection of individuals to occupational therapy programmes that mirror the desired personality and resilience for healthcare as a career choice (Thomas et al., 2017). The selection process undertaken by the university affiliated with this study, employs values-based interviews to determine which students are suitable for entering the profession exhibiting personal and professional attributes, behaviours and values.

The use of psychometric testing of candidates prior to admission onto healthcare programmes, advocated as being of benefit, could capture students who score highly in resilience, with a creative personality and desirable traits aligned with professionalism (Childs-Kean et al., 2020). However, Mason et al. (2015) and McGinley (2020) suggest the need for further research around use of professionalism scales and predicting suitability within allied health. By fitting the person’s current skill set to the expected role (Patterson and Zibarras, 2017) brings a danger of excluding individuals who have potential to develop and opposes the notion that the constructs of professionalism, resilience and entrepreneurship are a dynamic process nurtured over time. This approach narrows the diversity of practitioners entering the profession, at a time when career paths are varied, accommodating graduates with differences for divergent practice arenas. There is, however, merit in using recruitment platforms to highlight to potential applicants wishing to enter the profession, the qualities and attributes that are requisite for entering a career in occupational therapy (McGinley, 2020).

Objective recruitment with a clear remit over desirable attributes alongside academic attainment ensures students wishing to enter the profession are selected appropriately (McGinley, 2020). Psychometric testing in student selection is not considered to add value to existing screening and selection processes but could be used as a tool in establishing a student’s resilience, creativity and traits to provide a baseline for personal development on commencement of study (Childs-Kean et al., 2020). The use of values-based recruitment and MMI are increasingly used in preference to traditional interviews; designed to identify and capture students who are deemed most suited, where there is an opportunity to explore ethical dilemmas, reasoning, self-awareness, team working, professionalism and communication skills. However, evidence of how psychometric properties align to the scenarios and questions posed at the interview stations to facilitate judgement of character is lacking (Thomas et al., 2017).

Employing self-rating scales at points in time across the duration of the student’s study allowing milestone measurement of non-cognitive abilities would allow students to explore their own attributes, behaviours, protective factors and personal enablers (Brown et al., 2017). By students identifying their own characteristics and traits raises self-awareness, allowing for potential for personal growth through the use of development platforms including support mechanisms/personal tutee systems and learning/experiential opportunities delivered through the curriculum. Furthermore, embedding explicit platforms to nurture reflectivity in both academic and placement performance will enhance a student’s sense of self, being and becoming as a student practitioner facilitating positive adaptation and growth. By exploring how to nurture openness, conscientiousness, extraversion and agreeableness whilst promoting emotional stability is pivotal.

|

The Big Five traits and associated characteristics

Openness – intellectual curiosity, innovative, creativity, adaptable, active imagination, problem-solving and independent thinking Conscientiousness – diligence, commitment, self-discipline, determination, dependability and reliability Extraversion – sociable, optimistic, energetic, outgoing and assertive, confident, self-efficacy Agreeableness – empathy, sensitivity, insightful, compassion, altruism, loyal and kind, social, cooperative Neuroticism – emotionally unstable, pessimism, self-critical, sensitive, prone to irrational thought |

Building resilience and ability to thrive

This study supports the value of role-emerging placements in nurturing ontological development, professional identity and resilience as a consequence of undertaking these challenging experiences advocating all students should benefit from this, concurring with Clarke et al. (2015). Placement models can offer different experiences with varying levels of support and demands. Therefore, understanding the demands of each placement regardless of its type or adopted model and selective allocation of students to align to their strengths and needs is pivotal.

Resilience, a key requisite to becoming a healthcare practitioner must be embedded explicitly in an educational context if all students are to develop this, through facing challenge or adversity and positive adaptation. Building resilience will allow students to be more likely to thrive rather than just survive (Bleasdale and Humphreys, 2018). Curriculum delivery should emphasise the development of individual competencies associated with resilience from the outset of a student’s time of study by viewing resilience as a dynamic process that can be learned and enhanced. The opportunity for personal growth and development over the duration of a period of study in both campus and placement experiences and learning facilitates greater levels of resilience in later stages of training allowing diverse placements to be undertaken.

The way in which this is facilitated is less defined with De Witt (2017) arguing that resilience cannot necessarily be taught with a ‘one size fits all’ classroom approach and that it is a personal construct affected by internal and external factors that may not be within the sphere of educators to influence. Helping students to understand their own stress-coping mechanisms and that some stressors can challenge (in a positive sense), others are a hindrance (Flinchbaugh et al., 2015) and the value to exploring how these align or are perceived by students in relation to placements. Equally, performance expectations and the impact of academic failure can be normalised to build resilience through effective student support mechanisms and tutoring systems (Edwards and Ashkanasy, 2018).

Strategies, techniques and activities such as mindfulness, reflective journals and peer support increasing awareness of personal journeys and motivations are pivotal (Grant and Kinman., 2013, Clarke et al., 2019). Improving self-efficacy and self-regulation help to build resiliency (Boardman, 2016) and emotional intelligence (Gribble et al. 2018). Mentorship programmes and mechanisms that bring positive and nurturing professional relationships and a sense of belongingness (Clarke et al., 2019), with Bleasdale and Humphreys (2018) advocating the importance of the teacher–student relationship to students’ development of resilience. This mutually beneficial relationship between tutor and student facilitates a belief in each other that is a powerful enabler, placing students in situations where there is confidence they will thrive. Zhou and Urhahne (2013) discuss student success through intrapersonal motivation based on a teacher’s judgement of their ability through attributional theory, first postulated by Weiner (1985). If the student perceives that the placement tutor believes in their ability to cope, it has an empowering impact by alleviating self-doubt and creating challenge stressors as they embrace the placement more positively. In stating ‘you saw something in me. . . you knew I would be able to cope with the pressure of it’. Therefore, the propensity to thrive occurs when a student does not necessarily perceive or face adversity in their placement experience, or deals with it more effectively, arguable as a consequence of selecting the more capable student with a strong sense of self-efficacy (Brown et al., 2017; Flinchbaugh et al., 2015). Equally, students gain confidence knowing that you have belief in them to cope and succeed supporting compulsory allocation to these placements. The resilience of individuals is reflected in nurturing relationships and a belongingness within universities with Bleasdale and Humphreys (2018) suggesting consideration of the extent that this is supported through the physical environment and use of space, student societies and staff–student events. However, Kunzler et al. (2020) conclude the effectiveness of resilience ‘interventions’ within healthcare training requires more robust evidence particularly in its impact beyond the short to medium term. The nature of targeted training may improve resilience and reduce stress and anxiety, but current evidence is lacking with further research recommended.

Entrepreneurship is for everyone

Entrepreneurship is a requisite for the occupational therapy profession if it is to diversify and meet the shifting health and well-being agendas. Students must be equipped with entrepreneurial skills and business acumen giving them the confidence to shape practice and healthcare delivery (Doll and Holmes, 2020). Being entrepreneurial is not just for the elite in search of business venture success but is relevant to contemporary healthcare and can be achieved as an active learning process to nurture creativity and thinking outside of the box (Patterson and Zibarras, 2017). This aligns with the core skills such as problem-solving that are requisite in occupational therapy practice. Students need to be open to new experiences, hold a strong self-belief or self-efficacy in their own abilities and be motivated and autonomous to drive forward their own goals. A curriculum that exposes students to a breadth of opportunities where they develop confidence, learn to take risks and that positively rewards new experiences will facilitate and nurture creativity (Quality Assurance Agency (QAA), 2018).

Creating a culture to facilitate enterprise awareness, an entrepreneurial mindset, capability and effectiveness through curricula design and extra-curricular learning activities will support students to become more entrepreneurial (Davey et al., 2016). Modules that help students to explore leadership and innovation in practice could be developed further to include intellectual property, taking ideas forward into execution through scoping, marketing and production of ‘products’ with a commercial viability and value. Equally, social entrepreneurship can be nurtured through curriculum delivery and experiential learning (Davey et al., 2016) exploring community-based approaches with students being immersed in social enterprise opportunities such as volunteering, elective experiences and contemporary placements in the third sector. Hence, this study supports earlier research recommending that all students are placed in placements where entrepreneurial skills and resilience can be developed, based on the understanding of the demands of a placement and the premise of aligning students using a personal approach to allocation and adopting different placement models.

The study findings allowed for a model to be constructed to outline how individual differences and the constructs of resilience and entrepreneurship can be adopted. The complex relationships between the constructs are embedded into the student journey, with pivotal milestone stages to facilitate the process of growth shaping identity and development (See Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The resilience, entrepreneurship and personality development model.

Limitations

This study and subsequent recommendations are constructed on the data collected from occupational therapy student participants, from one UK-based university delivering occupational therapy education. Working practices may be different with other universities using placement teams, sitting outside of programme responsibilities and with the universities structures and curriculum design directing practice-based learning. To add further credibility and robustness to the study, it is acknowledged that additional qualitative data gathered from the students who had not had a role-emerging placement that is, a traditional placement would be of value. The research was situated in doctoral study and was undertaken as a stand-alone, time bound project, limiting the scope for data collection. The study solely focuses on occupational therapy students and their perspectives of placement experiences. It is acknowledged that capturing the perspectives of the placement providers, on-site supervisors and the long-arm supervisor would add depth to the study. The employment of a specific measurement tool to quantify entrepreneurial traits would strengthen the quantitative data rather than capturing this through the measurement scales of resilience and personality trait.

Conclusion

This paper draws on a study and its findings that set out to explore why some students appear to thrive and are able to turn a role-emerging placement into a positive, empowering experience despite the challenges, where others may not. Through exploring individual differences of students in undertaking placement experiences, both traditional and role-emerging settings allowed for gaining understanding of this phenomenon. The study used the constructs of resilience and entrepreneurship aligned with personality to offer understanding of how these are pivotal to developing graduates who transition into practice and can positively adapt and thrive in challenging healthcare environments. The findings can be broadened out to beyond the value of placements but to how the curriculum design and extra-curricular activities can nurture competence and professional identity built through resilience and an entrepreneurial mindset throughout the student journey. The findings are presented and captured in a model to guide those working in the higher education sector to consider the scope and application of this in practice.

Key findings

• Students need to understand their own traits and characteristics and have opportunity for personal growth and development nurturing resilience, entrepreneurship and professional identity.

• Curricula and extra-curricular activities should facilitate positive risk taking, openness to new experiences and nurture a sense of belonging.

• Understanding the demands of a placement and alignment of placement experiences to students using a personalised approach to allocation has scope to optimise development of resilience and entrepreneurship.

What the study has added

This mixed-methods study brings a unique and valuable insight to understanding the complexity and mutually beneficial relationship of individual difference, resilience and entrepreneurship through the platform of role-emerging placements, building on the existing body of knowledge to inform the occupational therapy profession and higher education sector more widely.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Professor Mandy Robbins, Director of Studies, for her support and guidance throughout this study. The author would also like to thank the students who willingly volunteered to participate in the data collection.

Footnotes

Research ethics: Glyndŵr Research Ethics Sub-Committee granted 07/07/2016 Id287.

Consent: Written consent was obtained from participants.

Patient and Public Involvement data: During the development, progress and reporting of the submitted research, Patient and Public Involvement in the research was not included at any stage of the research.

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author declared no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Contributorship: LC is the single author of this study.

ORCID iD: Liz Cade  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5780-6641

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5780-6641

References

- Bandura A. (2012) On the functional properties of self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management 38: 9–44. [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge J, Pentland D. (2020) A mapping review of models of practice education in allied health and social care professions. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 83: 488–513. [Google Scholar]

- Biddle C, Schafft K. (2015) Axiology and anomaly in the practice of mixed methods work: Pragmatism, valuation and the transformative paradigm. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 9: 320–334. [Google Scholar]

- Bleasdale L, Humphreys S. (2018) Undergraduate Resilience Research Project. Leeds: Leeds Institute for Teaching Excellence, University of Leeds. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman L. (2016) Building resilience in nursing students: Implementing techniques to foster success. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience 18: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. (2013) Successful Qualitative Research. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Brown D, Arnold R, Fletcher D, et al. (2017) Human thriving: A conceptual debate and literature review. European Psychologist 22: 167–179. [Google Scholar]

- Brown T, Yu ML, Hewitt AE, et al. (2019) Exploring the relationship between resilience and practice placement success in occupational therapy students. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 00: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprara GV, Alessandri G, Eisenberg N. (2012) Prosociality: The contribution of traits, values and self-efficacy beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 102: 1289–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh MA, Boswell WR, Rochling MV, et al. (2000) An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among US managers. Journal of Applied Psychology 85: 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs-Kean L, Edwards M, Douglass Smith M. (2020) Use of personality frameworks in health science education. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 84: 1085–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke C, De Visser R, Sadlo G. (2019) From trepidation to transformation: Strategies used by occupational therapy students on role-emerging placements. International Journal of Practice Based Learning in Health and Social Care 7: 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke C, Martin M, Sadlo G, et al. (2015) Facing unchartered waters: Challenges experienced by occupational therapy students undertaking role-emerging placements. International Journal of Practice Based Learning in Health and Social Care 3: 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb-Clark D, Schurer S. (2012) The stability of the big-five personality traits. Economics Letters 115: 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Connor K, Davidson J. (2003) The development of a new resilience scale: The Connor Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety 18: 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creek J, Cook S. (2017) Learning from the margins: Enabling effective occupational therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 80: 423–431. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. (2018) Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Davey T, Hannon P, Penaluna A. (2016) Entrepreneurship education and the role of universities in entrepreneurship: Introduction to the special issue. Industry and Higher Education 30: 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- De Witt J. (2017) Personal resilience for diagnostic radiographer healthcare education: Lost in translation. International Journal of Practice-Based Learning in Health and Social Care 5: 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Doll JD, Scaffa ME, Holmes WM. (2020). Program support: Innovation, entrepreneurship and business acumen. In: Scaffa M, Reitz M. (eds) Occupational Therapy in Community and Population Health Practice, 3rd edn. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis, pp. 134–152. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MS, Ashkanasy NM. (2018) Emotions and failure in academic life: Normalising the experience and building resilience. Journal of Management and Organisation 24(2): 167–188. [Google Scholar]

- Fan C, Carstensen T, Småstuen MC, et al. (2020) Occupational therapy students’ self-efficacy for therapeutic use of self: Development and associated factors. Journal of Occupational Therapy Education 4(1): Article 3. [Google Scholar]

- Fleeson W, Jayawickreme E. (2015) Whole trait theory. Journal of Research in Personality 56: 82–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flinchbaugh C, Luth MT, Li P. (2015) A challenge or a hindrance? Understanding the effects of stressors and thriving on life satisfaction. International Journal of Stress Management 22: 323–345. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton J, Costley C. (2019) Ethics. In: Costley C, Fulton J. (eds) Methodologies for Practice Research: Approaches for Professional Doctorates. London: Sage Publications, pp. 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Grant L, Kinman G. (2013) The importance of emotional resilience for staff and students in the ‘helping’ professions: Developing an emotional curriculum. York: HEA. [Google Scholar]

- Gray H, Colthorpe K, Ernst H, et al. (2020) Professional identity of undergradaute occupational therapy students. Journal of Occupational Therapy Education 4: Article 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gribble N, Ladyshewsky R, Parsons R. (2018) Changes in the emotional intelligence of occupational therapy students during practice education: A Longitudinal study. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 81: 413–422. [Google Scholar]

- Hocking C, Townsend E. (2015) Driving social change: Occupational therapist contributions to occupational justice. World Federation of Occupational Therapists Bulletin 71: 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes A, Galbraith D, White D. (2011) Perceived competence: A common core for self-efficacy and self-concept. Journal of Personality Assessment 93: 278–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter HM, Volkert A. (2016) Issues and challenges of role-emerging placements. World Federation of Occupational Therapists Bulletin 73: 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Donahue EM, Kentle RL. (1991) The Big Five Inventory – versions 4a and 54. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Kantarzis S. (2019) The Dr Elizabeth Casson Memorial Lecture 2019: Shifting our focus. Fostering the potential of occupation and occupational therapy in a complex world. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 82: 553–566. [Google Scholar]

- Kunzler AM, Helmrich I, Chmitorz A, et al. (2020) Psychological Interventions to foster resilience in healthcare students. Cochrane Systematic Review 7: CD013684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyte R, Frank H, Thomas Y. (2018) Physiotherapy students’ experiences of role-emerging placements: A qualitative study. International Journal of Practice-based Learning in Health and Social Care 6: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lecours A, Baril N, Drolet M. (2021) What is professionalism in occupational therapy? A concept analysis. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 88: 117–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnane E, Warren A. (2017) Apprehension and interest: Therapist and student views of the role-emerging placement model in the Republic of Ireland. Irish Journal of Occupational Therapy 45: 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Mason R, Butterfint Z, Allen R, et al. (2015) Learning about professionalism within practice-based education. International Journal of Practice-based Learning in Health and Social Care 3: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT. (2003) Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective (2nd ed). New York: The Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGinley SL. (2020) Pre-entry selection assessment results and final degree outcomes of occupational therapy students: Are there relationships? Journal of Occupational Therapy Education 4(3): Article 8. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Azorin JF, Fetters MD. (2019) Building a better world through mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 13: 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson F, Zibarras LD. (2017) Selecting for creativity and innovation potential: Implications for practice in healthcare education. Advances in Health Sciences Education 22: 417–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) (2018) Enterprise and Entrepreneurship Education: Guidance for UK Higher Education Providers. Gloucester: Quality Assurance Agency. Available at: https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaas/enhancement-and-development/enterprise-and-entrpreneurship-education-2018.pdf?sfvrsn=15f1f981_8 (accessed 14 June 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Occupational Therapists (2019) Learning and Development Standards for Pre-registration Education, Rev edn. London: Royal College of Occupational Therapists. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. (2012) Resilience as a dynamic concept. Development and Psychopathology 24: 335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saebi T, Foss N, Linder S. (2019) Social enterprise research: Past achievements and future promises. Journal of Management 45: 70–95. [Google Scholar]

- Scott I, Mazhindu D. (2014) Statistics for Healthcare Professionals (2nd ed). London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Thew M, Thomas Y, Briggs M. (2018) The impact of a role-emerging placement while a student occupational therapist, on subsequent qualified employability, practice and career path. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 65: 198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Young M, Mazer B, et al. (2017) Reliability and validity of the multiple mini-interview (MMI) for admissions to an occupational therapy professional program. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 80: 558–567. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B. (1985) An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review 92(4): 548–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists (2016) Minimum Standards for the Education of Occupational Therapists. World Federation of Occupational Therapists. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Urhahne D. (2013) Teacher judgment, student motivation, and the mediating effect of attributions. European Journal of Psychology of Education 28: 275–295. [Google Scholar]