Abstract

BACKGROUND

The authors discuss the first reported case of a large, high-grade arteriovenous malformation (AVM) in the dominant hemisphere, discovered incidentally after a penetrating nail gun injury.

OBSERVATIONS

The patient underwent surgical removal of a nail lodged in the right frontal lobe. A contralateral AVM was diagnosed on his perioperative imaging and was evaluated further with diagnostic cerebral angiography. Because of the location of the AVM within the dominant fronto-opercular region, the patient underwent a super-selective Wada test to evaluate for the risk of expressive language deficit prior to undergoing a successful resection of the AVM. He had an excellent recovery from both surgeries without any neurological deficits.

LESSONS

This case illustrates the importance of continued suspicion for incidental findings when reviewing imaging, despite the presence of a known and obvious pathology. The observations add nuance to the standard considerations for surgical intervention for penetrating nail gun injuries, and the workup for incidentally found vascular lesions is reviewed.

Keywords: nail gun injury, cerebral arteriovenous malformation, penetrating traumatic brain injury, incidental finding

ABBREVIATIONS: AP = anterior-posterior, AVM = arteriovenous malformation, ICG = indocyanine green, MCA = middle cerebral artery.

Nail gun injuries to the head are rare but well-documented incidents. We present the case of a young man with an accidental nail gun injury to the right side of his head at a construction site, who was subsequently found to have a large, high-grade cerebral arteriovenous malformation (AVM) in the contralateral hemisphere. To our knowledge, there are no reported cases of an incidental AVM discovered after a nail gun injury. This case highlights the extreme rarity of this patient’s left-sided AVM diagnosis and the miraculous avoidance of catastrophe given that the nail gun injury occurred on the contralateral side. We discuss surgical considerations of nail gun injuries to the head, as well as the workup of incidental vascular lesions.

Illustrative Case

Initial Presentation and Nail Removal

A 24-year-old healthy male presented to the emergency department immediately after a workplace accident involving a nail gun. Per report, the patient was on a ladder at a construction site, with his coworker on the roof directly above him. The coworker was operating a pneumatic nail gun when it misfired, launching a nail that punctured the right side of the patient’s head. On arrival, the patient was neurologically intact. He was still wearing a red baseball cap with the nail protruding from it, since he was not wearing a helmet at the construction site.

Radiographs and CT scans were obtained, showing the foreign object entering the patient’s right frontal lobe and terminating just superior to the right lateral ventricle (Fig. 1). The patient was taken urgently to the operating room for surgical intervention. After removing the baseball cap and the remaining pieces of cloth surrounding the exposed nail, the site was shaved, marked, and draped in a sterile fashion (Fig. 2). An incision through the puncture site was made, and the skull surrounding the nail was exposed. A burr hole was placed adjacent to the nail in order to include the nail in a circumferential craniotomy flap. However, while the burr hole was being performed, the nail gradually egressed from the skull due to the vibrations of the drill. Rather than completing the burr hole, the nail was slowly removed by gently twisting it counterclockwise. The puncture site was widened with a drill to evaluate for underlying bleeding. No significant bleeding was encountered, so the planned craniotomy was aborted. The intact nail was sent to pathology. The puncture site was copiously irrigated with antibiotic-impregnated saline. The galea and skin were then closed with absorbable sutures. The patient recovered well afterward in the ICU. He was kept on an extended course of intravenous antibiotics, with no acute signs of intracranial infection, hematoma, or other complication.

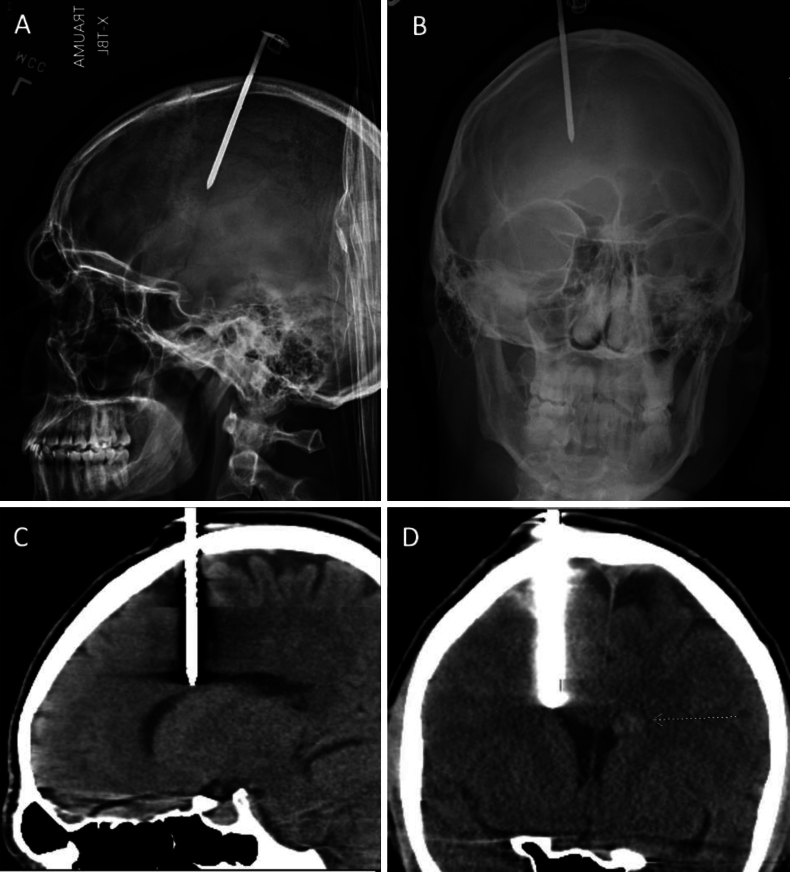

FIG. 1.

Preoperative imaging. Lateral (A) and AP (B) radiographs showing the hyperdense foreign object from the nail gun injury. Sagittal (C) and coronal (D) CT images showing the nail trajectory near the right lateral ventricle. A small hyperdensity can be noted near the left lateral ventricle, hinting at an underlying pathology.

FIG. 2.

Photograph showing the nail gun injury site in the operating room, after hair was shaved at the site.

Suspicion of an Incidental Finding and Vascular Workup

The patient received a CT scan postoperatively that revealed a trace amount of blood in the penetrating trajectory, as expected (Fig. 3). Careful review of imaging also showed a small area of hyperdensity in the left periventricular frontal lobe, contralateral to the injury. This was initially thought to be intraventricular blood related to the penetrating trauma. However, the persistence of the hyperdensity 24 hours after the patient’s injury, the lack of other dependent blood products in the occipital horns of the lateral ventricles, and the rounded morphology of the hyperdensity all raised suspicion of an incidental lesion unrelated to the initial injury.

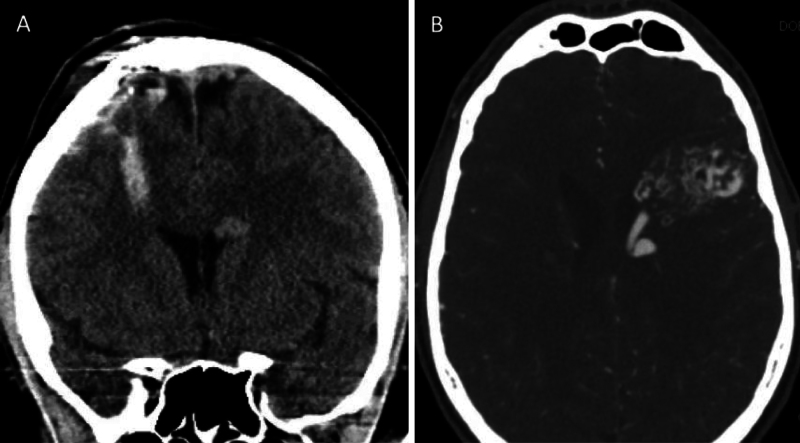

FIG. 3.

Postoperative imaging after removal of the nail. A: Coronal CT image without contrast showing a small amount of hemorrhage within the penetrating nail tract, as well as the suspicious left periventricular hyperdensity. B: Axial CT angiogram showing the large AVM within the left frontal lobe, with the 3.7-cm nidus centered near the pars opercularis.

CT angiography (Fig. 3) was performed to further investigate, and a large, high-grade AVM was discovered in the contralateral frontal lobe. The nidus measured 37.6 × 20.5 × 28.4 mm in the transverse, superior-inferior, and anterior-posterior (AP) dimensions, respectively, with hypertrophy of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) providing inflow to the left frontal AVM.

After the diagnosis was discussed with the patient, he agreed to undergo a diagnostic cerebral angiogram during the same hospitalization (Fig. 4) to further characterize the AVM. Angiography confirmed a compact 3.7-cm nidus in the left fronto-opercular region with inflow from the left MCA through a hypertrophied anterior division branch. The venous outflow of the AVM had both deep and superficial drainage. There was deep drainage into the left internal cerebral vein and vein of Galen. Additionally, there was a prominent superficial draining vein with outflow via the vein of Labbé and a smaller superficial cortical vein draining superiorly to the superior sagittal sinus. No inflow, nidal, or venous aneurysms were visualized.

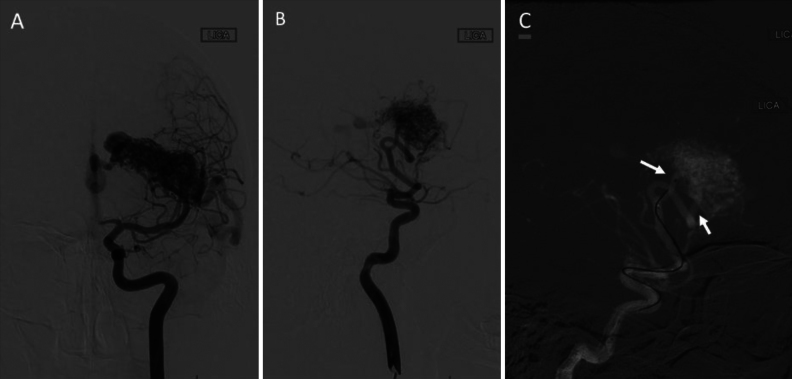

FIG. 4.

Digital subtraction angiograms. AP (A) and lateral (B) injections of the left internal carotid artery showing a large left-sided AVM (Spetzler-Martin grade 4, supplemented grade 6) with feeders primarily from the left MCA. There is deep venous drainage into the left internal cerebral vein and vein of Galen. There is also superficial cortical drainage into the vein of Labbé. Lateral view (C) of a super-selective injection via the two left MCA pedicles (arrows), which were used for injection of methohexital and lidocaine for Wada provocative testing.

These findings constituted a Spetzler-Martin grade 4 AVM, indicating a relatively high risk of surgical morbidity and mortality.1 The AVM had a supplementary grade of 6, which is the borderline score for acceptably low surgical risk.2 Extensive discussions were had regarding the high risk of rupture over his lifetime. Treatment options were discussed including observation, endovascular embolization, radiosurgery, and resection. Given the location of the AVM in the dominant frontal lobe centered near the pars opercularis of the inferior frontal gyrus, the risks of deficits to expressive language were discussed in addition to the typical risks of bleeding, seizures, infection, incomplete resection, stroke, and death. The patient deferred immediate treatment of the AVM and wished to continue discussions at a later time.

Interdisciplinary Discussion

The patient had no further complications from the nail gun injury, and the small hemorrhage in the projectile site had resolved on follow-up imaging. Despite the traumatic workplace accident, he quickly returned to work. He was seen in the outpatient setting on several occasions by the radiation oncology, neurointerventional radiology, and neurosurgery teams to discuss further workup and treatment options for his AVM. An interdisciplinary neurovascular conference convened and concluded that resection was the most appropriate treatment recommendation, citing risk of stroke from endovascular embolization and risk of incomplete obliteration from radiosurgery as reasons to avoid these alternatives.

Super-Selective Wada Test

We attempted to perform functional MRI to evaluate for eloquent speech areas around the left fronto-opercular AVM, but the patient was too claustrophobic to complete the study. Instead, he underwent a Wada test with left MCA arteriography and super-selective catheterization of the two dominant AVM feeders. This provocative test was used to assess the putative risk of expressive language deficits posed by AVM resection.3 The patient was awake for the procedure, rather than using neurophysiological monitoring.4 A manual injection of 3 mg of sodium methohexital was used due to its short duration of action and limited effects of drowsiness. This was followed by a manual injection of 30 mg of lidocaine to each pedicle to improve the sensitivity of the provocative test.5 Throughout the entire procedure, speech fluency, comprehension, repetition, and naming exercises were unaffected, demonstrating that the two dominant feeding arteries did not share blood supply with eloquent speech areas. The risk of expressive aphasia secondary to resection was felt to be mitigated, and the patient ultimately agreed to pursue definitive treatment with resection.

Resection of AVM

He underwent a left craniotomy for AVM resection 6 months after his initial nail gun injury. A curvilinear incision was utilized to expose the frontotemporal region, and a small craniotomy was performed just behind the pterion. After the dura mater was opened, indocyanine green (ICG) was used to confirm and eliminate the superficial cortical feeders to the AVM. The sylvian fissure was dissected to locate the proximal portion of the MCA. The deeper feeders to the nidus were confirmed with ICG, coagulated, and cut. Circumferential dissection was then used to remove the AVM while protecting the venous outflow until the lesion was removed entirely. Hemostasis was achieved, and a final ICG run confirmed the complete resection of the AVM.

Outcome and Follow-Up

Postoperative CT and angiography (Fig. 5) showed complete resection of the AVM with no further evidence of nidus filling or early venous drainage. The patient awoke from surgery with no neurological deficits and was discharged home on the 2nd postoperative day after an uncomplicated hospital course. He was seen afterward in the clinic for several follow-up visits and reported an excellent recovery. He will undergo repeat angiography 1 year postoperatively to exclude recurrence or residual.

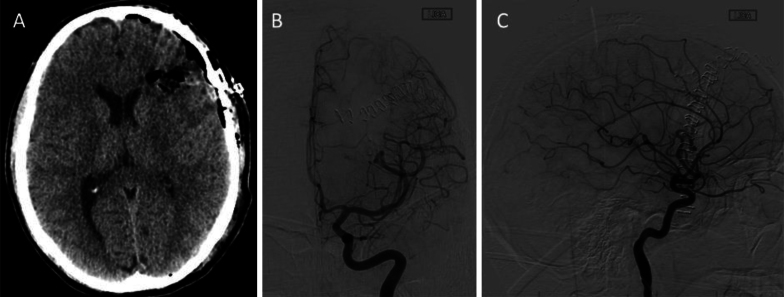

FIG. 5.

Postoperative imaging after resection of the AVM. Axial CT head scan without contrast (A) showing resection of the AVM without complication. AP (B) and lateral (C) digital subtraction angiograms showing complete resection of the AVM without signs of nidus filling or early venous drainage.

Informed Consent

The necessary informed consent was obtained in this study.

Discussion

Observations

Nail gun injuries to the head represent an uncommon phenomenon. Nail gun injuries reached a peak of 37,000 injuries annually from 2001 to 2005 when pneumatic nail guns grew in popularity.6 The majority of these were hand or extremity injuries, with few reported cases of head injuries. However, rates of nail gun injuries have dropped dramatically in subsequent years.7 This can be partly attributed to specialized triggers that require contact with a surface in order to engage. More importantly, injuries have been and will continue to be prevented by the appropriate use of personal protective equipment. According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s nail gun safety guide, hard hats, high-impact eye protection, and hearing protection should be provided by an employer to any construction worker operating a pneumatic nail gun.8

Nevertheless, nail gun injuries still occur at the workplace, especially in residential construction sites, as seen with our patient.9 Recent case series have also found that a large proportion of these injuries are self-inflicted.10–12 Despite the violent imagery of these injuries, nail gun injuries have an overall mortality rate of 10%, which is relatively low when compared with high-velocity projectiles such as gunshots. Because of the low velocity of these projectiles (100–150 m/sec), the most common complication from nail gun trauma comes from vascular injury and associated intracranial hemorrhage.6

Management of nail gun injuries typically requires surgical removal due to the high risk of infection or migration. The gold standard surgical management includes a craniotomy or craniectomy around the nail entry site to remove the nail from the brain under direct visualization, which is especially important if direct vascular injury is suspected.10 Furthermore, preoperative angiography has been described in low-velocity projectile injuries if the location or trajectory of the nail is suspicious for direct vascular injury, as this would complicate the surgical treatment.13 Traumatic carotid-cavernous fistulas, superior sagittal sinus injuries, and delayed carotid pseudoaneurysms have all been successfully treated after nail gun injuries.14–16

Fortunately for our patient, the entry site of the nail was in the right frontal lobe, near the coronal suture and lateral to the superior sagittal sinus. The location and trajectory approximated an external ventricular drain placed at Kocher’s point. Preoperative vascular imaging was deemed unnecessary given the lack of major blood vessels in the vicinity of the injury, especially with minimal hemorrhage seen on CT around the foreign object. Similarly, the operative treatment of this patient only involved removal of the nail from the exposed skull since the nail egressed without resistance only from the vibrations of the drill. This technique of removal without a craniotomy has been described in prior literature, although the risks are higher in patients who present with neurological deficits or vascular injury.17 Copious irrigation and intravenous antibiotics helped to prevent infection, and postoperative imaging showed no evidence of vascular injury at the site of the nail.

To our knowledge, the incidental finding of an AVM, or any intracranial pathology for that matter, from a nail gun injury has never been reported. Overall, incidental pathologies diagnosed on cranial CT scans in traumatic brain injury patients are low at 4%–10%.18,19 Typically, these findings include benign calcifications, sinusitis, mega cisterna magna, or remote infarcts. Very rarely does a cranial CT without contrast during a traumatic brain injury lead to the diagnosis of a vascular malformation (1 in 15,831 CT scans according to one retrospective analysis).20 Furthermore, incidental unruptured AVMs are rare in themselves, encompassing 13.1% of total AVM presentations, compared to patients presenting with ruptures or typical unruptured symptoms of headache, seizures, or neurological deficits. A recent retrospective analysis found that incidental unruptured AVMs were typically smaller and less likely to have deep venous drainage, in contrast with this patient’s large, high-grade AVM.21 While this was a traumatic and unexpected manner of diagnosis for this patient, his nail gun injury led to the discovery and expedient treatment of his AVM before it ruptured or became symptomatic.

Lessons

We present an unprecedented case of a large, high-grade cerebral AVM discovered incidentally via a nail gun injury. Although nail gun injuries to the head are a rare entity in themselves, often occurring in construction site accidents or from self-inflicted injuries, the discovery of an incidental intracranial pathology in this manner has not been reported previously. The management of these injuries depends on the entry, depth, and trajectory of the nail, but universally involves surgical removal of the foreign body. In this case, further workup included angiography and a super-selective Wada test to evaluate the AVM and stratify the risk of resection. After the appropriate workup, the AVM was resected without complication. This case highlights the improbability of this patient’s AVM diagnosis, a unique workup for an incidental vascular anomaly, and the miraculous avoidance of catastrophe had his injury been on the opposite side.

Disclosures

Dr. Jean reported being a consultant for Surgical Theater.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: all authors. Acquisition of data: Patrick, Najera, Jean. Analysis and interpretation of data: Patrick, Najera, Jean. Drafting the article: Fleisher, Patrick, Jean. Critically revising the article: all authors. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: Fleisher, Jean. Approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Fleisher.

Correspondence

Max S Fleisher: George Washington University Hospital, Washington, DC. maxsfleisher@gwu.edu.

References

- 1.Hafez A, Koroknay-Pál P, Oulasvirta E.The application of the novel grading scale (Lawton-Young grading system) to predict the outcome of brain arteriovenous malformation. Neurosurgery. 2019;84(2):529-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Can A Gross BA Du R.. The natural history of cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017;143:15-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bican O, Cho C, Lee L.Positive pharmacologic provocative testing with methohexital during cerebral arteriovenous malformation embolization. Clin Imaging. 2018;51:155-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tawk RG Tummala RP Memon MZ Siddiqui AH Hopkins LN Levy EI.. Utility of pharmacologic provocative neurological testing before embolization of occipital lobe arteriovenous malformations. World Neurosurg. 2011;76(3-4):276-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feliciano CE de León-Berra R Hernández-Gaitán MS Torres HM Creagh O Rodríguez-Mercado R.. Provocative test with propofol: experience in patients with cerebral arteriovenous malformations who underwent neuroendovascular procedures. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(3):470-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makoshi Z AlKherayf F Da Silva V Lesiuk H.. Nail gun injuries to the head with minimal neurological consequences: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2016;10:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipscomb HJ Nolan J Patterson D Dement JM.. Continued progress in the prevention of nail gun injuries among apprentice carpenters: what will it take to see wider spread injury reductions? J Saf Res. 2010;41(3):241-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Nail Gun Safety: A Guide for Construction Contractors. Accessed March 31. 2025. https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/NailgunFinal_508_02_optimized.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.. Nail-gun injuries treated in emergency departments—United States, 2001-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(14):329-332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray L.. Craniocerebral nail gun injuries: a definitive review of the literature. Brain Inj. 2021;35(2):164-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu RC Yoshida MC Kopp M Lin N.. Treatment of a self-inflicted intracranial nail gun injury. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(1):e237122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zima LA Srinivasan S Budde B Kitagawa R.. Thirty-two nails injected into the head: an operative report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2022;13:377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Mefty O Holoubi A Fox JL.. Value of angiography in cerebral nail-gun injuries. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1986;7(1):164-165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brooks CA Dower A Bonura A Manning N Van Gelder J.. Traumatic intracranial nail-gun injury of the right internal carotid artery causing pseudoaneurysm and caroticocavernous fistula. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(8):e243789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nussbaum ES Graupman P Patel PD.. Repair of the superior sagittal sinus following penetrating intracranial injury caused by nail gun accident: case report and technical note. Br J Neurosurg. 2023;37(3):448-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kow CY Hakim JS Aspoas AR Brew S McGuinness B Correia J.. Nailed through superior sagittal sinus: a case report and surgical considerations. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2023;24(3):e223-e227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim TW Shim YS Oh SY Hyun DK Park HS Kim EY.. Head injury by pneumatic nail gun: a case report. Korean J Neurotrauma. 2014;10(2):137-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eskandary H Sabba M Khajehpour F Eskandari M.. Incidental findings in brain computed tomography scans of 3000 head trauma patients. Surg Neurol. 2005;63(6):550-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Razavi-Ratki SK, Arefmanesh Z, Namiranian N.CT scan incidental findings in head trauma patients—Yazd Shahid Rahnemoun hospital, 2005-2015. Arch Iran Med. 2019;22(5):252-254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers AJ, Maher CO, Schunk JE.Incidental findings in children with blunt head trauma evaluated with cranial CT scans. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):e356-e363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu AY, Winkler EA, Garcia JH.A comparison of incidental and symptomatic unruptured brain arteriovenous malformations in children. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2023;31(5):463-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]