Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the role of myosin 1b (Myo1b) in infantile hemangiomas (IHs).

Patients and Methods

The expression of Myo1b in IHs and normal skin tissues was evaluated using immunohistochemical techniques. Expression of Myo1b in hemangioma endothelial cells (HemECs) was detected using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction and Western blotting techniques. The effects of Myo1b on cell proliferation, invasion, tube formation and other biological characteristics were analyzed. A mouse model was established to observe the inhibitory effects of Myo1b in vivo. Protein expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) and glucose transporter 1 protein (Glut-1) in a Myo1b knockdown HemECs was detected using Western blot.

Results

Myo1b was highly expressed in the proliferative stage of IHs, and promoted proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis in vitro. Mouse models further demonstrated that Myo1b inhibited proliferation and angiogenesis of IHs. Knockdown of Myo1b inhibited Glut-1 activity, promoted expression of PPARγ transcription factor.

Conclusion

Myo1b has a pro-tumor effect on IHs, knockdown of Myo1b facilitated progression of the proliferating to involution phase of IHs. Therefore, Myo1b is expected to serve as a new target for the treatment of IHs.

Keywords: hemangioma-derived endothelial cells, infantile hemangioma, PPARγ, Myo1b, Glut-1

Introduction

Infantile hemangioma (IHs) is the most common benign soft tissue tumor in infancy, with an incidence of 4–10% and most commonly affects white and female children and premature babies.1–3 IHs have a unique, self-limiting disease course, with onset usually approximately 2 weeks after birth, an accelerated growth rate at 5.5 weeks to 7.5 weeks of age, and then slowing,4 entering a longer phase to complete involution typically lasting approximately 3 years.5 Approximately 10% of patients with IHs experience dysfunction and disfigurement.6 Presently, oral propranolol is the first-line clinical treatment for IHs.7 The pathogenesis of IHs remains unclear, and relapse after propranolol withdrawal can occur, especially in high-risk patients with IHs.6 Therefore, there is an urgent need to further explore the mechanism of occurrence and development of IHs to identify better therapeutic targets.

The pathogenesis of IHs have not been fully elucidated, although hypotheses involving hypoxia, placental origin, and angiogenesis, have been proposed. IHs mainly originate from endothelial cells of progenitors of the placental chorionic villi. As one placental marker, glucose transporter 1 protein (Glut-1) is an erythrocyte glucose transporter expressed in the endothelium of tissues with barrier functions, such as the placenta and blood-brain-barrier.8 An imbalance between angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of IHs.9,10 Angiogenesis refers to the transformation of the endothelial cell phenotype from a static to a highly active state under the stimulation of pro-angiogenic factors, especially vascular endothelial growth factor A. A large amount of energy is required to support the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells,11 and glycolytic metabolism of endothelial cells is one of the initiating factors in angiogenesis.12 Studies have shown that Glut-1-positive hemangioma endothelial cells (HemECs) exhibit facultative stem cell characteristics and can be induced to differentiate into pericytes, adipocytes, or smooth muscle cells in vitro.13,14 As a specific diagnostic marker of IHs, Glut-1 can predict the typical process of IHs involution after proliferating phase.8,15

Myosin 1b (Myo1b) is a motor protein and a major member of the myosin superfamily that drives the cycle of interaction with actin filaments through ATP hydrolysis and the energy released by hydrolysis products, thereby promoting cell motility and many key physiological and pathological processes,16,17 studies show that Myo1b is mainly located in the cytoplasm of tumor cells.18 Accumulating evidence indicates that dysregulation of Myo1b expression is involved in the occurrence and development of tumors, including neuroblastoma19 esophageal squamous cell carcinoma,20 and cervical cancer.21 Previous studies have reported that Myo1b is highly expressed in metastatic prostate cancer and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and that knockdown of Myo1b significantly inhibits the invasion ability of tumor cells by affecting actin found in muscle tissue.18,22 Wen et al revealed that knockdown of Myo1b could significantly inhibit Glut-1 expression, thus affecting the glycolysis level of cervical cancer cells.23 However, whether Myo1b plays a role in the genesis and development of IHs remains unclear.

In the present study, we verified that Myo1b is highly expressed in IHs tissues and that knockdown of Myo1b inhibited the proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis of HemECs. We also successfully generated a nude mouse model of Myo1b knockdown and found that targeting Myo1b could inhibited the proliferation and angiogenesis of IHs, possibly by promoting adipogenic differentiation, and accelerating IHs fading. These results suggest that Myo1b may be a potential therapeutic target.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

The protocol involving human subjects was approved by the Shandong Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (Shandong, China; SZRJJ: No. 2022–256). Informed consent was obtained from the parents/guardians of all participants in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. All samples were obtained from the Department of Plastic and Aesthetic Surgery, Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University (Shandong, China), and were previously untreated and pathologically diagnosed with proliferative IHs after surgery. All animal studies were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital Institutions (No. 2023–155).

Cell Extraction and Culture

HemECs were extracted from proliferating phase IHs tissues as previously described.15 Cell culture was performed using a special endothelial cell medium (ScienCell, Shanghai, China) containing 5% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% endothelial growth factor in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. The human umbilical vein endothelial cell (ie, “HUVEC”) line (CRL-1730) was purchased from Shanghai Genetic Chemistry.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted using RNAiso Plus reagent (Takara, Kyoto, Japan) and complementary DNAs were reverse transcribed from 1 μg total RNA using HiScript RT Super Mix for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (Vanzyme, Nanjing, China). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix (Vanzyme) and a thermocycler (Light Cycler 480 II, Roche, Basel, Switzerland). qRT-PCR was performed using the following conditions: predenaturation at 95°C for 30s; denaturation at 95°C for 5s; and annealing at 60°C for 30s. Amplification was performed over 40 cycles. Relative gene expression was analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method with the housekeeping gene β-actin as the internal control. The primers used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers Used in This Manuscript

| GENE | Forward Primer (5′-3′) | Reverse Primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Myo1b | GAGTCTGGATTCGGCCAAAGT | CGAGATTCGGGCTTGAACTCA |

| PPARγ | AGAAAACCAAGGGACCCGAA | AGAGAGGGTCCCATTTCCGA |

| β-Actin | GGGAAATCGTGCGTGACATTAAG | TGTGTTGGCGTACAGGTCTTTG |

Western Blotting

Total protein was extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Protein concentration was determined using a commercially available kit (BCA Protein Assay Kit, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). After separation using 10% sodium-dodecyl polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and incubated with primary antibodies against Myo1b (132 kDa, Rabbit [1:2500], ab194356, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), β-actin (42 kDa, Rabbit [1:10,000]; 66,009-1-Ig; Proteintech, San Diego, CA, USA), Glut-1 (54 kDa, mouse [1:1000], 66,290-1-Ig; Proteintech), PPARγ (58 kDa, Rabbit [1:1000]; ab272718, Abcam), and GAPDH (36 kDa, mouse [1:50,000], 60,004-1-Ig, Proteintech) at 4°C overnight. The PVDF membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (peroxidase/HRP conjugated [1:10,000]; E-AB-1003; Elabscience, Houston, TX, USA) or goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (peroxidase/HRP conjugated [1:10,000]; E-AB-1008; Elabscience) for 1 h. An imaging system (ChemiDoc Imaging System, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was used to quantify protein expression.

Immunohistochemical Staining

Dewaxed sections were stained with primary antibodies against Myo1b (1:500; ab194356, Abcam) and secondary antibodies (G1213, Servicebio, Hubei, China). A DAB Substrate Kit (Servicebio) was used to stain the samples for 1 min, followed by hematoxylin (Servicebio) for 20s. Myo1b expression in tissues was scored by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining, according to the following method. The extent and intensity of staining in 5 fields of view were assessed using a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at ×400 magnification. Staining intensity was classified into 4 grades: no staining (score, 0); pale yellow (score, 1); pale brown (score, 2); and dark brown (score, 3). Positive expression areas were classified into 5 categories: < 5% (score, 0); 6–25% (score, 1); 26–50% (score, 2); 51–75% (score, 3); and 76–100% (score, 4). The intensity and area scores were multiplied and used as the final Myo1b expression scores. All sections were scored by 2 independent pathologists from the Shandong Provincial Hospital, who were blinded to the clinical data. If the scores of the 2 pathologists differed, the mean score was used for analysis.

Cell Transfection

A Myo1b knockdown lentivirus (shMyo1b) and its negative control (sh-negative control (sh nc) were constructed. The target sequence for shMyo1b was 5′–TCCTCTAGATTTGGCAAATAT–3′. The knockdown lentivirus of Myo1b was constructed using GV493 (hu6-mcs-cbh-gcgfp-ires, puromycin). The multiplicity of infection (MOI) for the knockout lentivirus was 50. HemECs were inoculated on a 6-well culture plate (Corning, New York, NY, USA). The infection fluid containing shNCs and shMyo1b was added to HemECs, and the medium was changed 12 h after infection. Transfection efficiency was evaluated by measuring the expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) 72 h after transfection, and the cells were screened using purinomycin according to the vector. After the first transfection of lentivirus, transfection efficiency was determined using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and Western blotting.

CCK-8 Assay

HemECs were inoculated into a 96-well plate (Corning, USA) 10 μL of CCK8 (Elabscience, China) was added to each well 2 h after inoculation. Optical density of each well was measured at 450 nm at 2, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h.

Transwell Assay

The cells were cultured in the upper chamber (Biofil, Guangzhou, China) of an undiluted matrix gel (ABW, Shanghai, China) for migration assays. Extracellular matrix (ECM) without fetal bovine serum and ECM containing 10% fetal bovine serum were added to the upper and lower cavities, respectively. After 24 h incubation, the upper cavity cells were scraped with cotton swabs, fixed to the lower surface of the membrane using paraformaldehyde for 30 min, stained with crystal violet (Solarbio) for 20 min, and the cells were counted after the images were captured.

Tube Formation Assay

Matrigel was added to 96-well plates (Corning, USA) on ice and then incubated for 30 min at 37°C in 5% CO2. HemECs (4 × 103) were seeded into the matrigel-coated plates and cultured at 37°C. Images were captured after 4 h.

Mouse Model of IHs

Ten, 6-week-old, male, BALB/c nude mice were purchased from Pengyue Lab, Animal Breeding Co., Ltd., and were randomly divided into 2 groups. The cells were resuspended in serum-free medium at a concentration of 108 cells/mL and mixed in a 1:1 ratio with matrigel. A mixture was subcutaneously injected (200 μL) in immunodeficient NOD/SCID mice, and tumors were removed 2 weeks after treatment. In vivo imaging was performed on day 14 after cell injection and, after subjecting the nude mice to isoflurane inhalation anesthesia (concentration, 1–3%), photographs were captured to record GFP expression in seeded cells. Bioluminescence imaging was performed using a multispectral imaging system (Caliper IVIS Lumina II, Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA, USA) to monitor tumor growth. The mice were then euthanized, and the tumor samples were further analyzed using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corporation Armonk, NY, USA) and Prism version 8 (GraphPad Inc, San Diego, CA, USA). Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Student’s t-test was used to compare the 2 groups; differences with p < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Myo1b is Highly Expressed in IHs

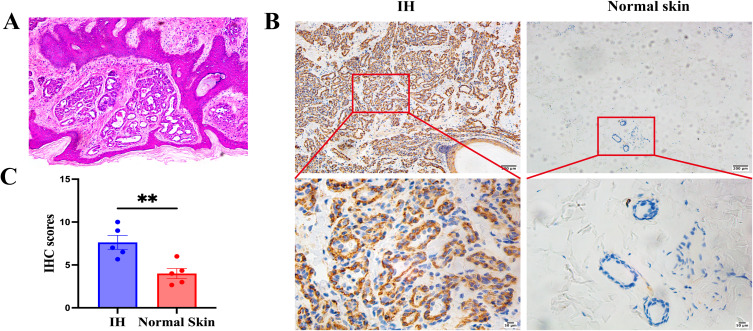

First, H&E staining was used to select pathological sections from infants at the proliferating stage for this experimental study. The clinical and pathological features of patients with IHs are summarized in Table 2. Pathological diagnosis was performed on 5 pairs of IHs samples collected, all of which exhibited typical H&E staining of IHs at the proliferating stage, as shown in Figure 1A. The Myo1b staining score in proliferating phase IHs tissues was significantly higher than that in normal skin tissues (Figure 1B). The t-test results for IHC staining revealed that the expression of Myo1b was significantly increased during the proliferating stage of IHs (Figure 1C). In conclusion, the expression of Myo1b in proliferative IHs tissues was significantly higher than that in normal skin.

Table 2.

Clinical Features of Five Patients With Infantile Hemangioma

| Rank | Gender | Age | Location | Growth Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 3M | Waist | Proliferating |

| 2 | Male | 2M | Abdominal wall | Proliferating |

| 3 | Female | 4M | Abdominal wall | Proliferating |

| 4 | Female | 6M | neck | Proliferating |

| 5 | Male | 5M | Abdominal wall | Proliferating |

Figure 1.

Myo1b is highly expressed in IHs. (A) Representative H&E staining of infantile hemangioma. Representative images (B) and scatter plot (C) of immunohistochemical staining showing Myo1b expression in IHs (n = 5) and normal skin (n = 5).Statistical analyses: two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test; **P < 0.01.

Myo1b Overexpression in HemECs

The results of qRT-PCR and Western blotting revealed that Myo1b expression was higher in HemECs than in HUVECs (Figure 2A–C). Lentiviral transfection was performed to generate stable Myo1b knockdown cell lines, and viral transfection efficiency was verified using qRT-PCR and Western blotting (Figure 2D–F).

Figure 2.

Myo1b overexpression in HemECs. (A)qRT-PCR analysis of Myo1b in HemECs (n = 5) and (HUVECs). Representative images (B) and scatter plot (C) of Western blotting for Myo1b expression in HemECs (n = 5) and HUVECs. (D)qRT-PCR analysis of Myo1b expression in HemECs after transfection with shNC and shMyo1b viruses.Representative images (E) and scatter plot (F) of Western blotting for Myo1b expression in HemECs after transfection with shNC and shMyo1b viruses. Scale bar, 100 μm.Statistical analyses: two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Abrreviations: ns, non significant; shMyo1b, Myo1b shRNA; shNC, normal control shRNA.

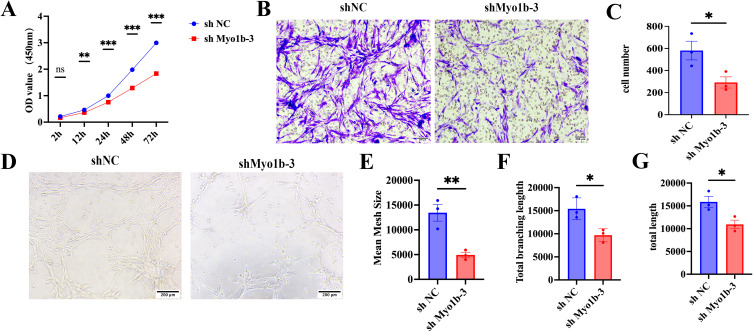

Myo1b Inhibited Endothelial Phenotype of HemECs

To further explore the biological effects of Myo1b on HemECs, CCK-8 cell proliferation, tube formation, and transwell migration experiments were performed. CCK-8 results revealed that knockdown of Myo1b led to a reduction in proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis, compared with the control group (Figure 3A). Results of the transwell migration experiment revealed that the number of migrating cells in the study group was significantly lower than that in the control group, and the difference between the 2 groups was statistically significant (Figure 3B and C). The tube formation that, compared with the control group, knocking down Myo1b could reduce the number of blood vessel formation rings, and the total length of nodes and blood vessels were shorter than those of the control (Figure 3D–G).

Figure 3.

Myo1b has a pro-tumor effect. (A) Cell proliferation was evaluated by the CCK-8 assay. Representative images (B) and scatter plot (C) (n = 3) of transwell invasion assay showing the invasion ability of HemECs. Representative images (D) of tube formation assays and statistics of the mean mesh size(E), total branching length (F)and total length(G), showing the angiogenesis ability of HemECs. Statistical analysis: two-tailed paired Student’s t test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Myo1b Promoted IHs Involution in vivo

A subcutaneous tumor transplantation model was used to explore the role of Myo1b in vivo. Results revealed that tumor size and weight were significantly lower in the Myo1b knockdown group than in the control group (Figure 4A–D). Histological examination using H&E staining demonstrated that endothelial cell clumps aggregated and formed microvessels in the shNC group, whereas after Myo1b knockdown, they were dominated by fibroadipose tissue, with a small number of relatively mature vessels (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Myo1b downregulation inhibits the growth of HemECs and promoted IHs involution in vivo. (A) IVIS of tumors in the animal model 14 days after cell implantation.(B)Weight of tumors were significantly reduced in the shMyo1b group compared with that in the shNC group. (C)Tumor volume was significantly reduced in the shMyo1b group compared with the shNC group.(D) Tumors of nude mice were dissected 2 weeks after subcutaneous injection in shNC and shMyo1b groups (5 mice in each group). (E) Representative H&E staining of tumors at 2 weeks. Statistical analyses: two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test; **p< 0.01.

Abbreviations: shMyo1b, Myo1b shRNA; shNC, normal control shRNA; IVIS, Lumina LT imaging system.

Knocking Down Myo1b Promoted PPARγ Activation, Inhibited Angiogenesis, and Accelerated the Involution of IHs

In order to preliminarily investigate the mechanism of action of Myo1b in IHs, we verified it by cell experiments. The qRT-PCR and Western blotting results demonstrated a significant increase in PPARγ expression after Myo1b knockdown (Figure 5A–C), it consistent with animal experiments. Therefore, our findings suggest that Myo1b inhibits microangiogenesis by upregulating PPARγ expression levels and may promote adipocyte transformation to accelerate IHs involution.

Figure 5.

Myo1b is Regulated by Glut-1 and PPARγ to Affect the Function of HemECs. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of PPARγ expression levels, representative images of Western blotting (B) and scatter plot of PPARγ (C) and Glut-1 (D)protein expression.Statistical analyses: two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test; **p< 0.01.

Myo1b May Regulate the Function of HemECs by Down-Regulating Glut-1 Expression

Glut-1 positivity is specific to proliferating phase hemangiomas and can predict the typical post-proliferative involution process. To explore the effect of Myo1b knockdown on Glut-1, the protein expression level of Glut-1 was determined using immunoblotting. Results revealed that the expression level of Glut-1 after Myo1b knockdown was significantly lower than that in the control group (Figure 5B and D). Therefore, Myo1b may affect the level of glycolysis and decrease the expression of Glut1 by reducing excessive energy supply, thus affecting the proliferation of tumors and accelerating the progression of IHs into the involution phase.

Discussion

IHs are the most common vasogenic tumor among infants and young children. According to the unique natural history of IHs, it usually develops approximately 2 weeks after birth and then progresses through three stages: hyperplasia, involuting, and completion of involution. Most cases of IHs resolve spontaneously. However, approximately 10% of patients continue to experience pain, ulcers, bleeding, infection, dysfunction, and/or disfigurement.6 Oral propranolol is the first-line treatment for IHs, with an efficacy rate > 90%. Many studies have reported relapse of IHs after propranolol withdrawal. According to our latest research, after 3 months of maintenance treatment, the relapse rate of IHs was significantly reduced.24 Although oral propranolol can accelerate resolution of IHs, propranolol resistance remains a problem in high-risk patients with IHs. Therefore, there is an urgent need to further explore the mechanism of occurrence and development of IHs to identify better therapeutic targets.

Myo1b has a pro-tumor effect in various diseases. Studies have shown that, in colorectal cancer, Myo1b can enhance the secretion of angiogenic factor and promote tumor angiogenesis by blocking the autophagy degradation of HIF-1α.25 It can significantly inhibit the invasion of tumor cells in prostate cancer and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.18,22 A study investigating lung adenocarcinoma found that Myo1b acted as an alternative splicing switch to activate the Akt-mTOR signaling pathway, inhibiting the transformation from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation, and thus regulating metabolism.26 Glut-1 plays a major role in energy supply in proliferating IHs, regulating glucose in red blood cells to supply corresponding tissues through various barriers, such as the placental barrier, and promoting related processes of cell metabolism.24 It was found that the expression of Glut-1, a key enzyme in the glycolytic pathway in proliferating phase IHs, was higher than in involution.27 As a specific diagnostic marker for IHs, Glut-1 expression can predict the typical process of IHs involution after proliferation.1 Therefore, we hypothesized that Myo1b, a motor protein, inhibits cell metabolism by inhibiting Glut-1 expression. In our study, we found that Myo1b was highly expressed in IHs tissues and HemECs during the proliferating period. shNC and shMyo1b were successfully constructed by lentivirus transfection. Myo1b was found to affect cell proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis in vitro. According to gross anatomy after 2 weeks, knockdown of Myo1b led to a reduction in proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis and, based on H&E staining, Myo1b inhibited micro-angiogenesis and accelerated the regression process of IHs, which further confirms the role of Myo1b in in vitro experiments. To confirm these results, we performed protein immune-imprinting experiments. Compared with the control group, the Glut-1 expression level in Myo1b knockdown cells was inhibited, suggesting that IHs may progress from the proliferating phase to the involution stage.

During IHs involution, endothelial cells gradually undergo apoptosis; hemangioma stem cells differentiate into mesenchymal stem cells and then further differentiate into adipocytes and fibroblasts.15 The pathological evolution of IHs is inevitably accompanied by changes in the expression of adipose-differentiation genes. PPARγ is a transcription factor that regulates energy balance by promoting energy deposition or energy dissipation.28 The expression of PPARγ indicates that cells have the potential to differentiate into adipocytes, and this regulatory effect is mainly in the early stage of adipose differentiation.29 A large amount of PPARγ was expressed in both the IHs extinction stage and the extinction completion stage, suggesting that PPARγ signaling pathway was involved in the IHs regression process.30 At the same time, PPARγ is not only related to lipid regulation and adipose differentiation, but also inhibits the formation of IHs by affecting angiogenesis. When activated, PPARγ down-regulates angiogenic factors and up-regulates angiogenic, resulting in an environment that is not conducive to angiogenesis and, thus, affects tumor growth.10 In our study, we were surprised to find that tumor cells in the Myo1b knockdown group exhibited an obvious trend of transformation into fat cells in animal experiments. To explore this result, a protein immune-imprinting experiment was performed to verify that the expression level of PPARγ protein was significantly increased after Myo1b knockdown. Because the activation process of PPARγ was similar to the phenomenon of increased fatty acid metabolism and formation of fibrous adipose tissue in infantile treated hemangioma during the involution phase, this result further confirmed our speculation. Myo1b may promote the progression of IHs from the proliferating phase to the extinction stage.

To some extent, results of our study demonstrate the role of Myo1b in the pathogenesis of IHs. Myo1b regulates the proliferation, invasion, and tubule-forming ability of HemECs in vivo and in vitro. At the same time, knockdown of Myo1b can inhibit Glut-1 activity and promote the expression of PPARγ transcription factors, thus contributing to the progression from proliferating phase to involution phase of IHs. However, the present study had some limitations. First, although we explored the possibility that Myo1b may affect energy supply during glycolysis by inhibiting Glut-1 expression, we did not verify our hypothesis through experiments related to cell metabolism. Second, although PPARγ involvement in the regulation of HemECs by Myo1b has been verified, the specific mechanism promoting the involution of IHs has not been demonstrated through in vitro lipogenic differentiation experiments. Third, although the regulation of Glut-1/ PPARγ was not the focus of this study, the specific mechanism of its intervention regulation remains to be further explored. These limitations may provide ideas for future research.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Editage for English language editing.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant no. 82372537] and [grant no. 82172227]; and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant No. ZR2023QH116).

Abbreviations

IHs, Infantile hemangiomas; HIF-1α, hypoxia inducible factor la; HemECs, hemangioma endothelial cells; Glut-1, glucose transporter type 1; HUVECS, Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells; PPAR-γ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; ECM, Endothelial cell medium; GFP, Green fluorescent protein.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work”.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390(10089):85–94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00645-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, Wong LF. Infantile hemangioma. Part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(6):1379–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harter N, Mancini AJ. Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangiomas in the neonate. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2019;66(2):437–459. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2018.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tollefson MM, Frieden IJ. Early growth of infantile hemangiomas: what parents’ photographs tell us. Pediatrics. 2012;130(2):e314–e320. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couto RA, Maclellan RA, Zurakowski D, Greene AK. Infantile hemangioma: clinical assessment of the involuting phase and implications for management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(3):619–624. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31825dc129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z, Cao Z, Li N, et al. M2 Macrophage-Derived Exosomal lncRNA MIR4435-2HG Promotes Progression of Infantile Hemangiomas by Targeting HNRNPA1. Int J Nanomed. 2023;18:5943–5960. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S435132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solman L, Glover M, Beattie PE, et al. Oral propranolol in the treatment of proliferating infantile haemangiomas: British society for paediatric dermatology consensus guidelines. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(3):582–589. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernández F, Navarro M, Encinas JL, et al. The role of GLUT1 immunostaining in the diagnosis and classification of liver vascular tumors in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(5):801–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.01.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janmohamed SR, Madern GC, de Laat PC, Oranje AP. Educational paper: pathogenesis of infantile haemangioma, an update 2014 (part I). Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(1):97–103. doi: 10.1007/s00431-014-2403-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ji Y, Chen S, Li K, Li L, Xu C, Xiang B. Signaling pathways in the development of infantile hemangioma. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-7-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rohlenova K, Veys K, Miranda-Santos I, De Bock K, Carmeliet P. Endothelial cell metabolism in health and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28(3):224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X, Sun X, Carmeliet P. Hallmarks of endothelial cell metabolism in health and disease. Cell Metab. 2019;30(3):414–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang L, Nakayama H, Klagsbrun M, Mulliken JB, Bischoff J. Glucose transporter 1-positive endothelial cells in infantile hemangioma exhibit features of facultative stem cells. Stem Cells. 2015;33(1):133–145. doi: 10.1002/stem.1841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.North PE, Waner M, Mizeracki A, Mihm MC Jr. GLUT1: a newly discovered immunohistochemical marker for juvenile hemangiomas. Hum Pathol. 2000;31(1):11–22. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(00)80192-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Zou Y, Huang Z, et al. KIAA1429 promotes infantile hemangioma regression by facilitating the stemness of hemangioma endothelial cells. Cancer Sci. 2023;114(4):1569–1581. doi: 10.1111/cas.15708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sweeney HL, Holzbaur ELF. Motor Proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10(5):a021931. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pernier J, Kusters R, Bousquet H, et al. Myosin 1b is an actin depolymerase. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):5200. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13160-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohmura G, Tsujikawa T, Yaguchi T, et al. Aberrant myosin 1b expression promotes cell migration and lymph node metastasis of HNSCC. mol Cancer Res. 2015;13(4):721–731. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang HF, Delaidelli A, Javed S, et al. A MYCN-independent mechanism mediating secretome reprogramming and metastasis in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. Sci Adv. 2023;9(34):eadg6693. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adg6693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li SH, Qian L, Chen YH, et al. Targeting MYO1B impairs tumorigenesis via inhibiting the SNAI2/cyclin D1 signaling in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Cell Physiol. 2022;237(9):3671–3686. doi: 10.1002/jcp.30831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang HR, Lai SY, Huang LJ, et al. Myosin 1b promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;149(1):188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makowska KA, Hughes RE, White KJ, Wells CM, Peckham M. Specific myosins control actin organization, cell morphology, and migration in prostate cancer cells. Cell Rep. 2015;13(10):2118–2125. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wen LJ, Hu XL, Li CY, et al. Myosin 1b promotes migration, invasion and glycolysis in cervical cancer via ERK/HIF-1α pathway. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13(11):12536–12548. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L, Wang W, Zhou Z, et al. Exploration of the optimal time to discontinue propranolol treatment in infantile hemangiomas: a prospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90(4):783–789. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen YH, Xu NZ, Hong C, et al. Myo1b promotes tumor progression and angiogenesis by inhibiting autophagic degradation of HIF-1α in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(11):939. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-05397-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma Z, Chen H, Xia Z, et al. Correction: energy stress-induced circZFR enhances oxidative phosphorylation in lung adenocarcinoma via regulating alternative splicing. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2023;42(1):180. doi: 10.1186/s13046-023-02771-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang K, Qiu T, Zhou J, et al. Blockage of glycolysis by targeting PFKFB3 suppresses the development of infantile hemangioma. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s12967-023-03932-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medina-Gomez G, Gray S, Vidal-Puig A. Adipogenesis and lipotoxicity: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) and PPARgammacoactivator-1 (PGC1). Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(10A):1132–1137. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keshet R, Bryansker Kraitshtein Z, Shanzer M, Adler J, Reuven N, Shaul Y. c-Abl tyrosine kinase promotes adipocyte differentiation by targeting PPAR-gamma 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(46):16365–16370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411086111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan SM, Chen RL, Shen WM, Chen HN, Zhou XJ. Mesenchymal stem cells in infantile hemangioma reside in the perivascular region. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2012;15(1):5–12. doi: 10.2350/11-01-0959-OA.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]