Abstract

Malaria is a parasitic disease that has caused suffering to humans since ancient times and remains a major public health concern in tropical and subtropical regions.The development of novel antimalarials therefore becomes of utmost importance by targeting aspartic protease. The computational study utilized a molecular docking approach to identify hit compounds. In this study a molecular docking approach was employed to identify potential hit compounds. The molecular docking analysis yielded three hit compounds CMNPD229, ZINC000000018635, and ZINC000005425464 along with the reference drug chloroquine, with binding energy scores of -8.1 kcal/mol, -8.0 kcal/mol, -7.8 kcal/mol, and − 6.8 kcal/mol, respectively. Subsequently density function theory (DFT) was performed. Afterward, the protein-ligand (PL) complexes were subjected to molecular dynamic simulation (MDS) to identify the stability and rigidity of the complexes in a fleeting and dynamic setting. The complex CMNPD229 exhibited good stability followed by ZINC000000018635, ZINC000005425464, and the Control. The compounds showed good MM-PBSA/GBSA, WaterSwap, and entropy energy values. The calculated MM-PBSA/GBSA binding free energy scores were − 120.78 kcal/mol, -107.16 kcal/mol, -91.00 kcal/mol, and − 97.49 kcal/mol for CMNPD229, ZINC000000018635, ZINC000005425464, and the reference drug, respectively.Additionally, salt bridge analysis and secondary structure evaluation revealed that CMNPD229 formed the highest number of interactions (Glu290-Arg23 and Glu305-Lys306), indicating its stability as a potential drug candidate. This study suggests that CMNPD229 holds promise as a potent antimalarial drug by effectively inhibiting Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax aspartic proteases.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-98516-9.

Keywords: Aspartic protease, Molecular Docking, Molecular dynamic simulation, Plasmodium species, Salt bridges

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Drug discovery

Introduction

Malaria is one of the world’s top three diseases, along with HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, yet it is often overlooked1. Billions of people are affected by it annuallyNand remains a major issue for those residing in tropical and subtropical countries, \. Malaria, as a parasitic disease, malaria has plagued humans long before recorded history2. According to the WHO’s 2021 Malaria Report³, there are 241 million malaria cases worldwide, with the majority occurring in Africa3. Nearly 90% of the world’s population has been exposed to the parasite resulting in over 700,000 deaths, with 75% of fatalities occurring in young children4,5. Malaria in humans is caused by the Plasmodium parasites, including Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malaroae, and P. knowlesi6. The highly pathogenic species, P. falciparum, is primarily responsible for mortality, especially among young children and pregnant women7. P. vivaxis the most widely distributed species, can induce recurring infections, considerably increasing malaria-related morbidity8.

Fortunately, P. vivax gametocytes are susceptible to antimalarial drugs like artemether-lumefantrine and chloroquine, with clinical trials showing that up to 90% of patients become gametocyte-free within the first day of treatment.

Most human malaria cases are caused by P.vivax and P. falciparum, with a significant proportion remaining asymptomatic4.Asymptomatic individuals can still transmit malaria through gametocytes, the sexual stage of the parasite responsible for mosquito infections. These gametocytes emerge within 2–4 days and may persist in circulation for up to four days7,9,10.Click or tap here to enter text.Click or tap here to enter text.Click or tap here to enter text. Fortunately, P.vivaxgametocytes are susceptible to antimalarial drugs like artemether-lumefantrine and chloroquine, with clinical trials showing that up to 90% of patients become gametocyte-free within the first day of treatment11.

A study using molecular methods found that gametocyte concentrations in afebrile individuals across four countries were most likely to contribute to malaria transmission4. The proportion of gametocyte-infected individuals varied significantly, with higher rates in regions with minimal transmission12,13. Children under six years old were particularly affected in areas with moderate-to-high malaria transmission. The findings can help develop effective screening and treatment strategies to reduce malaria transmission14.

Plasmodial proteases, particularly plasmepsins, are being explored as potential drug targets due to their well-defined structures and crucial roles in parasite development. The P. falciparumgenome encodes ten distinct plasmepsins (plasmepsin I to X), each with specific functions in the parasite’s life cycle15,16.

Aspartic proteases have been confirmed as molecular targets by genetic and pharmacological methods because of their crucial role in parasite survival and virulence. Disrupting some plasmepsins, such as plasmepsin IV and plasmepsin IX, has been shown in gene knockout experiments to have a substantial impact on parasite survival, suggesting their promise as therapeutic targets. Furthermore, additional proof of the therapeutic potential of aspartic protease inhibitors, including hydroxyethylamine-based inhibitors, against malaria has been revealed by their clinical validation17,18.

Antimalarial drug resistance refers to the ability of a parasite strain to survive and proliferate despite the administration and absorption of the drug at or above recommended concentrations19. Several variables contribute to the development of resistance to currently available antimalarial drugs, such as the rate of parasite mutation, overall parasite load, the potency of the drug selected, treatment compliance,, incorrect dosage, poor pharmacokinetic properties, counterfeit drugs leading to insufficient parasite drug exposure, and low-quality antimalarials that may promote and facilitate resistance20.

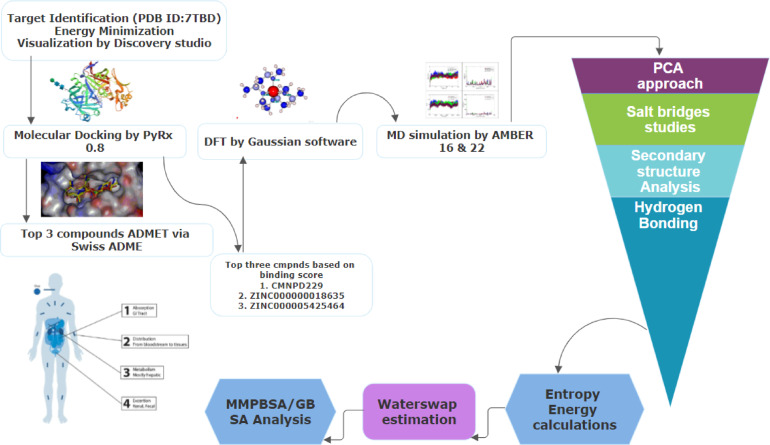

Target based screening is the initial step in the drug development process, aiding in the identification of lead compounds and effective antimalarial drugs21. Computer-aided drug design (CADD), especially when combined with modern chemical biology screening techniques, plays a crucial role in optimizing treatment candidates22. It has become a vital tool in drug design due to its capacity to accelerate drug development by using knowledge and theories about receptor-ligand interactions23. CADD is an inexpensive technology that has shortened the time from identifying targets to hitting development and optimization, subsequently speeding up the discovery of innovative therapeutics24. Aspartic proteases are believed to be potential targets for antimalarial drug development due to their vital function in parasite survival and pathogenicity. In the current study, we screened small molecule inhibitors from commercial compound libraries using virtual screening approaches combined with ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) assessment and molecular dynamic simulation of the protein crystal structure (Fig. 1). By evaluating hit compounds against P. falciparum and P. vivax, we identify novel antimalarial candidates that may target P. vivax, P. falciparum, and other plasmepsins.

Fig. 1.

The schematic methodology starts from (a) Target identification, (ii) Molecular docking, (iii) ADMET analysis (iv) DFT calculations, (v) MDS (vi) PCA technique, (vii) Salt bridges, (viii) Secondary structure analysis, (ix) Hydrogen bonding, (x) Entropy energy calculations, (xi) WaterSwap estimation, and (xii) MMPBSA/GBSA approach.

Methodology

Protein retrieval and Preparation

The 3D structure of plasmodial protease was retrieved from Protein Databank (PDB) with resolution of 2.22 with PDB ID 7TBD (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/7TBD). The protein underwent a series of processing procedures, comprising bond order assignment, hydrogen deletion and insertion, zero-order metal bond creation, disulfide bond formation, prime completion of side chains and loops, and deletion of water exceeding five from hetero groups. Following that, the protein was further optimized by structural optimization with UCSF Chimera and H-bond assignment using sample water orientations.

Ligand Preparation process

For the ligand preparation process, two libraries were utilized for structure-based virtual screening against plasmodial protease in docking studies: the Comprehensive Marine Natural Products Database (CMNPD) (https://www.cmnpd.org/), which contains 32,000 compounds, and ZINC (https://zinc15.docking.org/), comprising 10,000 lead-like compounds. Marine natural products (MNPs) have several biological and pharmacological uses, including drug development. Many of these chemicals have been identified as powerful inhibitors of important enzymes and pathways linked to illnesses such as cancer, bacterial infections, viral infections, and metabolic disorders. With the help of the receptor grid generating tool, the plasmodial protease’s ligand binding pocket was identified. It chooses the complex ligand’s coordinates to generate a three-dimensional grid with particular measurements that represent the active area of the receptor. The grid highlights the location and dimensions of the active site by centering on the centroid of the pre-existing bound ligand when using the standard setting.

Molecular Docking studies

Molecular docking was performed using PyRx 0.8 software to assess the interaction between the target protein and the compounds25. The two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) interactions of the docking complexes were visualized using Discovery Studio (https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer-download) and ChimeraX (https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimerax/), respectively.

In Silico ADMET Prediction

The ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) properties of the top drugs chosen from molecular docking studies were assessed to predict their pharmacokinetic profiles. This assessment was conducted using the SWISS ADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/) web server, which provides insights into drug-likeness, gastrointestinal absorption, blood-brain barrier permeability, and other key pharmacokinetic parameters. These predictions help in determining the suitability of the selected compounds for further drug development and optimization.

DFT analysis

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were performed to analyze the electronic and geometric structures of the selected compounds including band gaps, thermodynamic properties, and reactivity, providing deeper insights into their stability and potential biological activity26. The geometry optimization and frequency calculation of all the compounds were carried out by choosing Becke, 3-parameter, Lee-Yang-Parr (B3LYP) functional and 6–311G(d, p) basis set27. The optimized energy based on potential surface energy, dipole moment, polarizability, energy of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), and lowest occupied molecular orbital (LUMO), collectively known as frontier molecular orbitals (FMO) with their energy gap was calculated28. The global chemical reactivity descriptors were derived from the energy gap of the FMO gap (ΔEFMO = ELUMO - EHOMO) by application of Koopman’s theorem. Correspondingly Gaussian09 software and GaussView06 software were used for all DFT calculations and visualization of results29.

Molecular dynamic simulation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed for the top three protein-ligand complexes using the AMBER20 simulation software30. Prior to MD simulations, molecular docking studies were conducted as a preliminary step to identify the binding site of the ligand within the active pocket of the protein under static conditions. While docking provided initial insights into ligand interaction with the target protein, MD simulations were employed to evaluate the stability and behavior of the complexes under dynamic physiological conditions31. Initially, the complexes were processed using AMBER20 56’s Antechamber software32. While The General Amber Force Field (GAFF) was applied for ligand parameterization, while the AMBER FF14SB force field was used for the receptor protein30. The molecular dynamics (MD) simulations consisted of three key stages: preprocessing, prmtop file generation, and the production run. After the incorporation of counterions, the carefully selected docked complexes were solvated in a TIP3P water box. The system was gradually heated to 310 K and equilibrated before being subjected to a 100-ns production run. Temperature regulation was maintained using Langevin Dynamics to ensure system stability throughout the simulation33.

Hydrogen bond studies

Quantifying the number of hydrogen bonds formed between the compounds and the enzyme’s active site residues throughout the simulation is crucial, as it indicates the strength and stability of binding34. To analyze intermolecular hydrogen bonding, the H-Bonds plugin in Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) v1.9.3 was utilized35. The cut-off distance between the donor and acceptor atoms was fixed at 3.0 Å, and the cut-off angle was determined at 20 degrees36.

Free binding energy Estimation (MM-PBSA/GBSA)

One of the most frequently utilized endpoint-free energy methods established by Kollman and colleagues is the MM-PBSA method, which can also be used to assess the binding affinity of a ligand regarding binding free energy37. The approach is frequently employed to estimate regions of high activity, evaluate binding affinities, and examine the stability of structures38. Furthermore, MM-PBSA/MMGBSA enables an opportunity to look at the contributions provided by individual protein-ligand residues, highlighting the energetic contributions provided by each residue, particularly to the binding system, and indicating the key binding interactions39.

WaterSwap energy Estimation

The absolute binding free energy of the complexes was determined using the advanced WaterSwap technique to validate the formation of strong intermolecular interactions. WaterSwap enables the replacement of bound ligands in the enzyme’s active pocket with water clusters of the same size and shape, allowing for accurate free energy calculations40. The binding free energy was computed using three key methodologies: free energy perturbation (FEP), thermodynamic integration (TI), and Bennett’s acceptance ratio (BAR), ensuring a comprehensive evaluation of ligand binding strength41.

Entropy energy calculations

The entropy energy contribution to the overall complex binding free energy was estimated using AMBER normal mode analysis42. This analysis provided valuable insights into the stable conformation and energy of intermolecular binding. A lower entropy energy indicates restricted conformational flexibility of the ligand within the enzyme’s active pocket, suggesting a more stable binding interaction43,44. Due to the high calculating cost of normal mode analysis, the entropy energy estimation was carried out using only five frames. The translational, rotational, and vibrational energies of the complexes were computed during this study to gain a comprehensive understanding of their thermodynamic stability45.

PCA analysis

PCA, also called Essential Dynamics (ED), is a potent method for refining and explaining the main motional changes of a protein in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations46. The first step in the process involves collecting the simulation data that stores the atomic coordinates of a protein over time47. To ensure that only internal motions are investigated, these coordinates—which are normally focused on backbone atoms—are aligned to prevent global rotations and translations48. The aligned trajectory is then used to create a covariance matrix, which reflects correlations in atomic movements12. PCA calculates the main elements, or important modes, that represent the greatest collective motions in the protein by computing the eigenvalues and eigenvectors from this matrix49. The key motions of the protein are visualized by projecting the MD trajectory onto the first few principal components, which account for the majority of the variance50. These projections reveal conformational changes that are functionally useful, such as loop flexibility or domain movements, by distilling complicated movements down to a few essential factors51.

Salt bridges study

Salt bridges play a crucial role in computational drug design, significantly influencing ligand binding and protein stability52. These electrostatic interactions occur between oppositely charged groups on ligands and proteins or between charged amino acid residues, such as lysine or arginine with aspartate or glutamate53. Salt bridges are necessary for preserving the appropriate conformation of important functional regions, including the active site, and thereby stabilizing protein structures. Furthermore, these interactions improve the binding affinity and specificity of drug candidates, resulting in the production of stronger and more stable complexes in the drug discovery process54.Additionally, these interactions enhance the binding affinity and specificity of drug candidates, contributing to the formation of stronger and more stable complexes in the drug development process55.

Secondary structure analysis

In computational drug design, secondary structure analysis is crucial in identifying the nature of binding sites, understanding protein stability, and predicting the effects of conformational modifications on drug binding56. By evaluating these structural elements, researchers may develop more potent drugs targeting specific protein areas, improving connections, and identifying potential resistance reasons57.

Results

Protein retrieval and Preparation

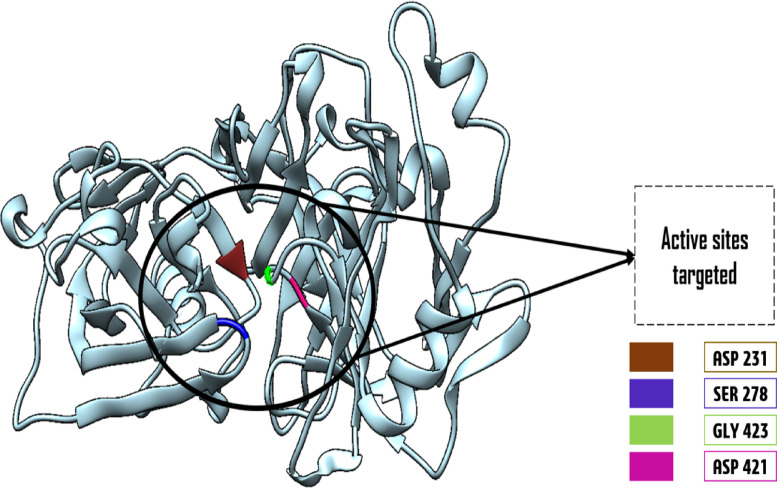

The current study was conducted to identify potential inhibitors against P. falciparum and P. vivax with the main protease enzyme. The three-dimensional (3D) crystal structure was downloaded from a protein data bank (PDB) with the ID; 7TBD given in Fig. 2. The structure was then loaded to the UCSF chimera to remove unnecessary atoms and water molecules. The crystal stricture has Global Symmetry: Asymmetric - C1 Global Stoichiometry: Monomer - A1. The enzyme structure is accessible at a resolution of 2.22 Å determined by the X-ray diffraction technique. The active binding pocket of the crystal structure was identified for docking studies depicted clearly in the Fig. 2 structure given below.

Fig. 2.

A close-up view of the active binding pockets (shown in different colors) identified for molecular docking studies in the plasmodial protease enzyme’s three-dimensional (3D) structure.

Molecular Docking studies analysis

It has been identified that aspartic protease is necessary for both the pathogenesis and survival of P. vivax strains58. Additionally, it is essential for those involved in egression and invasion during the parasitic asexual blood phase as it has been identified as an essential target for developing treatments against drug-resistant strains of Plasmodium. For docking studies against the plasmodial protease, two different compound libraries were utilized: one derived from ZINC Database (10,000 compounds), and the other derived from CMNPD (32000 compounds). In an attempt to study new potential drugs, these databases underwent extensive structure-based virtual screening to find potential protease-targeting inhibitors via the software PyRx 0.8.

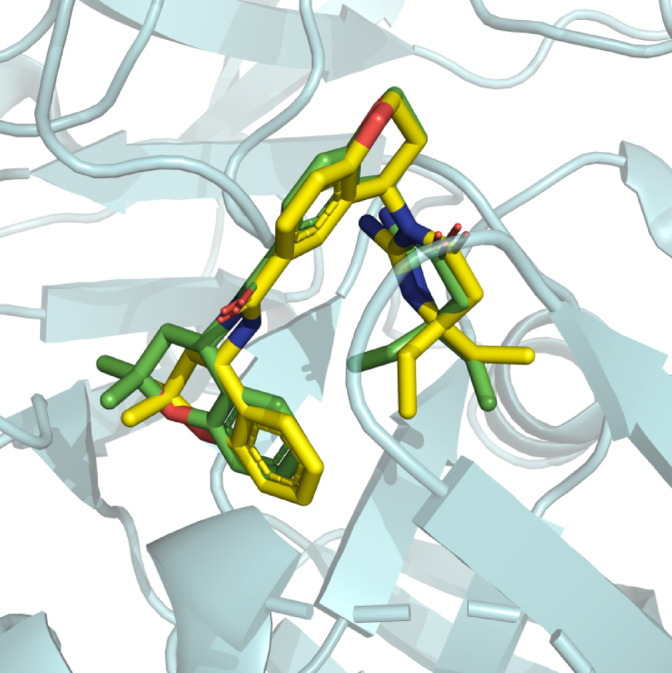

Subsequently, the docking protocol was validate d by redocking the native ligand ((4R)-4-[(2E)-4,4-diethyl-2-imino-6-oxo-1,3-diazinan-1-yl]-N-[(4 S)-2,2-dimethyl-3,4-dihydro-2 H-1-benzopyran-4-yl]-3,4-dihydro-2 H-1-benzopyran-6-carboxamide ) to the aspartic protease and RMSD was calculated. The native ligand successfully occupied the same binding conformation with the RMSD 0.32Å. The redocked conformation of the native ligands is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Redocking of the native ligand to the aspartic protease. The redocked conformation (Yellow) is superimposed to native conformation (Green).

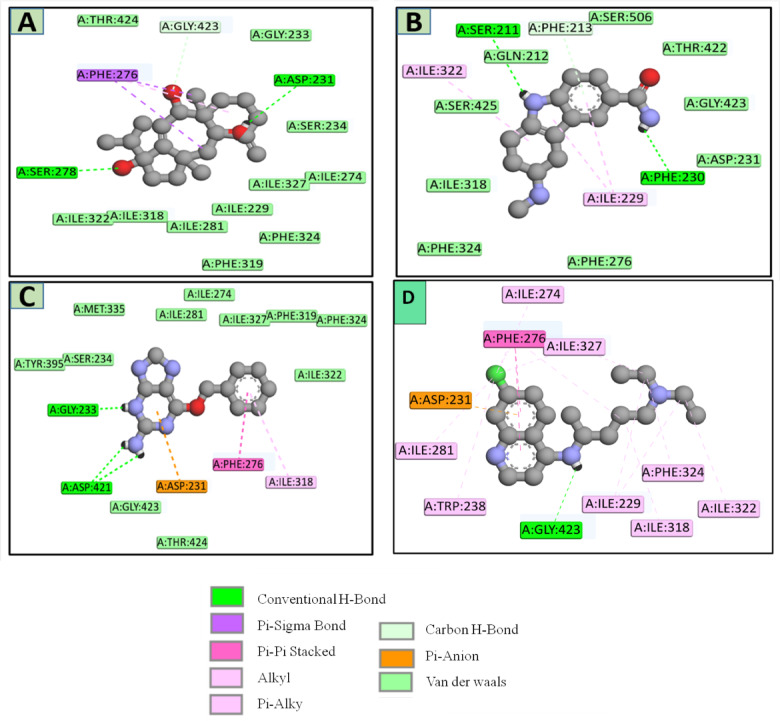

After docking of CMNPD and ZINC library compounds, the docked compounds were ranked based on the binding energy (Kcal/mol). Top three compounds were chosen for further computational study based on the binding affinity (Kcal/mol) and interactions with the key residues. The top three compound’s interactions with the target enzyme can be seen in Table 1. Table 2 contains the docking scores of the top 10 compounds that were screened against plasmodial protease species. Furthermore, Fig. 4 shows the ligand-protein non-bonding interactions (three-dimensional), and Fig. 5 shows two-dimensional view of the three selected ligands, CMNPD229 (3aR,4aR,8aS,9 S)-1-isopropyl-3a,8a-dimethyl-5-methylene-1,2,3,3a,4,4a,5,6,7,8,8a,9-dodecahydrobenzo[f]azulene-1,4a,9-triol (-8.1 kcal/mol), ZINC000000018635 3-(methylamino)-2,3,4,9-tetrahydro-1 H-carbazole-6-carboxamide (-8 kcal/mol), and ZINC000005425464 2-amino-6-(benzyloxy)-9 H-purine-1,3,7-triium (-7.8 kcal/mol), with control chloroquine ( -6.8 kcal/mol) obtained through molecular docking calculations.

Table 1.

The top three compounds and control molecule interaction with the target enzyme.

| Compound | Interaction |

|---|---|

| CMNPD229 | Thr 424, Asp231, Gly423, Gly233, Phe 276, Ser 278, Ser234, Ile 274, Ile 327, Ile229, Phe324, Phe319, Ile281, Ile318, Ile 322. |

| ZINC000000018635 | Ser 211, Phe230, Phe 213, Ser506, Gln212, Ile 322, Ser 425, Ile318, Gly423, Asp231, Phe276, Phe 324, Ile318, Ser 425. |

| ZINC000005425464 | Gly 233, Asp421, Tyr395, Ser 234, Met 335, Ile 281, Ile 274, Ile 327, Phe 319, Phe 324, Ile322, Ile 318, Phe 276, Asp 231, Thr 424, Gly 423, |

| Control | Gly423, Ile229,Ile318,Ile322, Phe324, Ile327, Ile274, Phe276, Asp231, Ile281, Trp238 |

Table 2.

The protease enzyme residues that were seen in interaction with the hit compounds and control molecule in the following table.

| S.No | Compound ID | Chemical Structure | Binding affinity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. |

CMNPD229 (3aR,4aR,8aS,9 S)-1-isopropyl-3a,8a-dimethyl-5-methylene-1,2,3,3a,4,4a,5,6,7,8,8a,9-dodecahydrobenzo[f]azulene-1,4a,9-triol |

|

-8.1 kcal/mol |

| 2. |

ZINC000000018635 3-(methylamino)-2,3,4,9-tetrahydro-1 H-carbazole-6-carboxamide |

|

-8 kcal/mol |

| 3. |

ZINC000005425464 2-amino-6-(benzyloxy)-9 H-purine-1,3,7-triium |

|

-7.8 kcal/mol |

| 4. |

CMNPD450 2-(11-methyl-3,7-dimethylenedodec-11-en-1-yl)benzene-1,4-diol |

|

-7.7 kcal/mol |

| 5. |

CMNPD1188 8-ethyl-3-hydroxy-3,5b,8,11a,13a-pentamethyl-13-oxoicosahydrochryseno[1,2-c]furan-4-yl acetate |

|

-7.6 kcal/mol |

| 6. |

CMNPD2030 3b-hydroxy-3,3,7a-trimethyl-4-methylenedecahydro-1 H-cyclopenta[a]pentalene-1,5-diyl diacetate |

|

-7.3 kcal/mol |

| 7. |

ZINC000000005109 6-(bicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-2-ylamino)-9-methyl-2,3,7,8-tetrahydro-1 H-purine-1,3,9-triium |

|

-7.3 kcal/mol |

| 8. |

ZINC000100004253 (E)-5-amino-11-ethylidene-7-methylene-5,6,7,8,9,10-hexahydro-5,9-methanocycloocta[b]pyridin-2-ol |

|

-7.3 kcal/mol |

| 9. |

ZINC000002525891 3-(1-hydroxy-2-((methylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)phenol |

|

-7.2 kcal/mol |

| 10. |

ZINC000038810990 1-(2-(1-carboxyvinyl)hydrazinyl)phthalazine-2,3-diium |

|

-7.1 kcal/mol |

| 11. |

Control Chloroquine |

|

-6.8 Kcal/mol |

Fig. 4.

A close-up 3D representation of the top three compounds CMNPD229, ZINC000000018635, ZINC000005425464, and the Chloroquine with the target protease enzyme.

Fig. 5.

A 2D view of the top three compounds CMNPD229 (A), ZINC000000018635 (B), ZINC000005425464 (C), and Chloroquine (D) with the target enzyme.

After looking at the 2D interaction of the compounds, it became apparent that CMNPD229 exhibited hydrogen bonds with Ser21, and Phe230, while ZINC000000018635 generated hydrogen bonds with Ser 278 and Asp 231. Next, the compound ZINC000005425464 displayed bonds with Gly423, and Gly233 and control was noted to show H-linkage with Gly 423, and Gly 233 Asp24.

DFT analysis

The optimized structures of all the compounds are represented in Fig. 6. The Hartree optimized energy measured in the atomic unit, intrinsic dipole moment, polarizability, and energies of FMO with their energy gap were depicted in Table 3 The dipole moment value of all the compounds showed that they have an increased propensity for charge transfer. The molecule having a smaller FMO energy gap (ΔEFMO) should be more reactive and less stable as compared to the molecule with a large value of ΔEFMO. The ZINC000000018635 was considered a more reactive compound among all others with (α = 196.64) and (ΔEFMO= 4.81). The HOMO LUMO contour plots with labeled FMO energy gap are shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 6.

The geometrical optimized structure of all compounds.

Table 3.

The electronic energy, dipole moment, polarizability, and energies of FMO with their energy difference.

| Compounds | Electronic Energy (a.u.) |

Dipole moment (debye) | Polarizability (a.u.) |

EHOMO (eV) | ELUMO (eV) | ΔEFMO (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZINC000000018635 | -783.33 | 4.98 | 196.64 | -5.70 | -0.89 | 4.81 |

| ZINC000005425464 | -812.98 | 5.29 | 183.59 | -5.90 | -1.02 | 4.88 |

| CMNPD229 | -1007.15 | 2.34 | 236.95 | -6.48 | -0.39 | 6.09 |

Fig. 7.

The contour plots of frontier molecular orbitals with their labelled energy gap.

The values of global reactivity descriptors (chemical potential(µ), absolute electronegativity (χ), chemical hardness (η), softness(S), electrophilicity index (ω)) calculated from Koopman’s theorem were depicted in Table 5. The chemical potential and electronegativity values are supposed to be interrelated with each other. The compound with a higher value of chemical potential displayed high reactivity and lower stability, whereas the lower electronegativity value depicted that the compound is more reactive with a higher propensity of electron transfer. The compound with the least hardness value and higher softness value has more tendency to accept electron correspondingly represented high reactivity than vice versa. The ZINC000000018635 with values of (µ = -3.30), (χ = 3.30), ( η = 2.41), and (S = 0.21) was predicted as the more reactive compound than all other included under the investigation. The ZINC000005425464 was considered strong electrophile with (ω = 2.45) while the CMNPD229 acted as the nucleophile with (ω = 1.94) compared to the control drug.

The reactivity of a molecule was evaluated by nucleophilic and electrophilic attack regions represented in molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surface analysis Fig. 8. The Red region indicated higher electron density with a strong -ve electrostatic potential, while the blue color represented lower electron density with + ve electrostatic potential. The effect of polarization represented that the red region concentrated around the electronegative atom while the blue region concentrated around the electropositive atom preferable for the nucleophilic and electrophilic attack respectively.

Fig. 8.

The molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) of the top three compounds.

In-silico ADMET analysis

In silico, the ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) investigations were performed to evaluate the docked compounds’ potential further. The pharmacokinetic and safety profiles of the top-ranked drugs were predicted with the help of these studies. Utilizing these features as guidance, the strongest candidates were selected based on their favorable ADMET profiles. This method ensures that the compounds have both strong binding affinity and drug-like features, which are required for their potential to be utilized as therapeutic agents against the plasmodial protease (Table S-1). CMNPD229 has a molecular weight of 320.47 g/mol, a TPSA of 60.69 Ų, and a high fraction of Csp3 (0.80), indicating good structural flexibility. It exhibits good lipophilicity (Consensus Log Po/w = 3.08), high GI absorption, and BBB permeability. It does not inhibit CYP enzymes, making it a safer candidate in terms of drug-drug interactions. ZINC000000018635, with a molecular weight of 243.30 g/mol and a TPSA of 70.91 Ų, has high GI absorption. ZINC000005425464, with a molecular weight of 244.27 g/mol and the highest TPSA (93.46 Ų), shows the moderate lipophilicity and high GI absorption. However, it inhibits CYP1A2, which may affect drug metabolism. Out of the three compounds CMNPD229 possess good BBB permeability. All three compounds comply with Lipinski’s rule of five, with a bioavailability score of 0.55.Based on these properties, CMNPD229 appears to be the most promising candidate due to its favorable absorption, BBB permeability, and minimal risk of metabolic interactions.

MDS trajectory data analysis

The conformation that provided the most effective binding pose throughout the docking studies is minimized solvated and finally put through further MD simulation study.

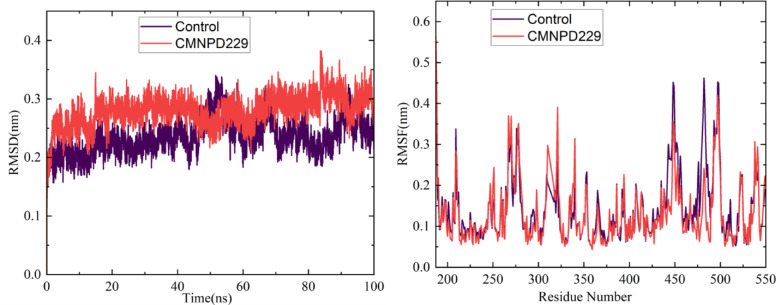

Root mean square deviation (RMSD)

The dynamic behavior of the protein-ligand (PL) complex was visualized by RMSD. The RMSD was plotted for the top three complexes CMNPD229, ZINC000000018635 ZINC000005425464 along with control for a 200ns simulation period (Fig. 9). The backbone RMSD of ZINC000000018635 showed little deviations at the start of the simulation and it stabilized at the end of the simulation. Upon analyzing the RMSD values, the CMNPD 229 exhibited a lesser mean value of 1.85 Å, 2.08 for ZINC000005425464, 2.09 Å for control, and 2.36 for ZINC000000018635 respectively (Table 4). From the findings, it is clear that the RMSD was stable for all complexes during the 100 ns simulation period, which describes that the ZINC000000018635 and ZINC000005425464 indicate minor deviations, but those do not compromise the overall behavior and stability.

Fig. 9.

Depicts the RMSD (A), RMSF (B), RoG (C) & Beta Factor (D) of the protein-ligand complexes.

Table 4.

The table contains RMSD, RMSF, RoG, B-factor, and SASA scores noted from simulation trajectories.

| Complexes | Minimum | Maximum | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD | |||

| CMNPD229 | 1.0 | 2.63 Å | 1.85 Å |

| ZINC000000018635 | 1.2 | 3.22 Å | 2.36 Å |

| ZINC000005425464 | 1.0 | 2.84 Å | 2.08 Å |

| Control | 1.2- | 2.86 Å | 2.09 Å |

| RMSF | |||

| CMNPD229 | 0.40 Å | 5.40 Å | 0.97 Å |

| ZINC000000018635 | 0.43 Å | 4.40 Å | 0.96 Å |

| ZINC000005425464 | 0.40 Å | 7.61 Å | 0.93 Å |

| Control | 0.38 Å | 4.47 Å | 0.86 Å |

| Radius of gyration (ROG) | |||

| CMNPD229 | 20.62 Å | 21.44 Å | 21.04 Å |

| ZINC000000018635 | 20.63 Å | 21.52 Å | 21.12 Å |

| ZINC000005425464 | 20.43 Å | 21.46 Å | 21.01 Å |

| Control | 20.50 Å | 21.29 Å | 20.94 Å |

| Beta Factor | |||

| CMNPD229 | 4.34 Å | 767.94 Å | 32.96 Å |

| ZINC000000018635 | 4.95 Å | 430.68 Å | 31.72 Å |

| ZINC000005425464 | 4.31 Å | 1524.66 Å | 33.84 Å |

| Control | 3.86 Å | 528.06 Å | 25.91 Å |

| SASA | |||

| CMNPD229 | 15202.3nm2 | 17621.1nm2 | 16333.6nm2 |

| ZINC000000018635 | 14611.5nm2 | 17556.9nm2 | 16371.6nm2 |

| ZINC000005425464 | 14572.5nm2 | 17050nm2 | 15938.7nm2 |

| Control | 14631.5nm2 | 17028.6nm2 | 15822.6nm2 |

Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF)

The plotting of the RMSF of amino acid residues enabled researchers to observe how flexible each residue became in reacting to ligand binding. Figure (Fig. 9) illustrates the RMSF of the protein and ligand-bound complexes. During the span of the 10-ns simulation, there was relatively little deviation in the RMSF for all four complexes (CMNPD229, ZINC000000018635, ZINC000005425464 and Control). Upon comparing with the control complex, the top 3 have mean values of 0.97 Å, 0.96 Å, 0.93 Å, and 0.86 Å respectively with the control having a smaller RMSF value among them (Table 4). The smaller value indicates that the residues in the protein-ligand binding regions fluctuated less as compared to the other complexes. Overall, the findings indicate that ligand attachment to protease increases its stiffness and decreases the frequency of residue-level fluctuation.

Radius of gyration (RoG)

The compactness and structural flexibility of the top 3 complexes as well as control were assessed by plotting the RoG. The results show that the control complex as compared to the other three complexes showed more structural stability during the 100ns simulation time Fig. 9). The RoG plots for (CMNPD229, ZINC000000018635, ZINC000005425464, and Control) have mean RoG values between 20.94 and 21.04 Å. (Table 4).

Beta-factor

The dynamic regions of the protein-ligand complexes were assessed by plotting the Beta factor. Beta factor was used to identify the flexible and rigid regions that contribute to the function of the protein and enzyme. The maximum values noted for the top three complexes and control were 4.34 Å, 4.95 Å, 4.31 Å, and 3.86 Å for CMNPD229, ZINC000000018635, ZINC000005425464 and Control respectively (Fig. 9). The findings showed that the protein-ligand complexes were rigid and flexible over the 100ns simulation period.

Solvent-accessible surface area (SASA)

SASA was plotted to identify the interaction of protease enzyme and solvent molecules on its surface region. The average values of the SASA noted were 16333.6 nm2, 16371.6 nm2, 15938.7 nm2 and 15822.6 nm2 for the CMNPD229, ZINC000000018635, ZINC000005425464 and Control respectively (Table 4). The protein-ligand complexes exhibited minor deviations indicating constant solvent permeability during the 100ns simulation (Fig. 10).

Table 5.

The global chemical reactivity descriptors derived from FMO gap.

| Compounds | Chemical potential(µ) | Absolute electronegativity (χ) | Chemical hardness (η) | softness(S) | Electrophilicity index (ω) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZINC000000018635 | -3.30 | 3.30 | 2.41 | 0.21 | 2.26 |

| ZINC000005425464 | -3.46 | 3.46 | 2.44 | 0.20 | 2.45 |

| CMNPD229 | -3.43 | 3.43 | 3.04 | 0.16 | 1.94 |

Fig. 10.

The SASA plot for the top three complexes CMNPD229, ZINC000000018635, ZINC000005425464, and Control against the target enzyme.

Principal component analysis

The diversity and flexibility of structures originating from the steady trajectory generated via 200-ns MD simulations were studied using PCA. In terms of collective motion, the first 50 eigenvectors/principal components are the most meaningful. We thoroughly examined the first two principal components (PCs). The 2D projection of the first two eigenvectors is displayed in Fig. 11. Whereas protease in the complex with CMNPD229 (A) exhibited a similar diversity of conformations with slight flexibility during simulation, ZINC000000018635 (B) was shown to display less diversity of conformations in the complex. In contrast to the control molecule, ZINC000005425464 showed a greater range of conformations during simulation. This reveals that CMNPD229 and ZINC000005425464 formed a more stable complex with protease.

Fig. 11.

PCA of protein-ligand (PL) complexes: (A) CMNPD229, (B) ZINC000000018635, (C) ZINC000005425464, and Control.

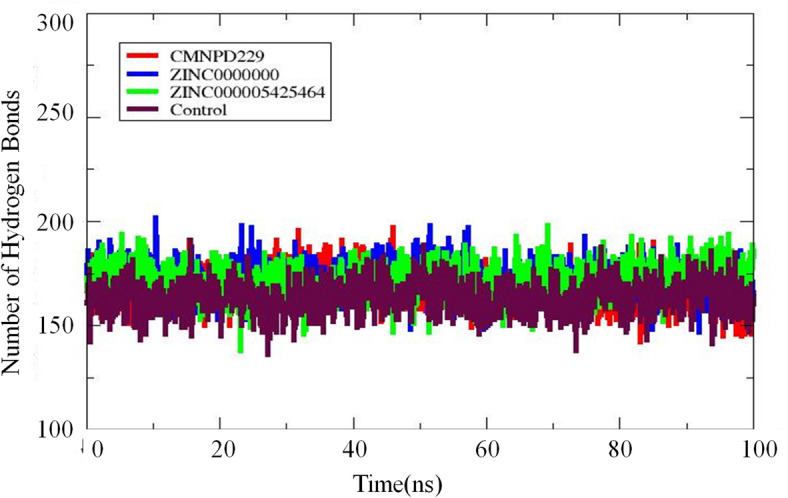

Hydrogen bonding

Hydrogen bonding evaluation is important for protein-ligand stability. The H-bond formation for the top three complexes (CMNPD229, ZINC000000018635, and ZINC000005425464) along with the control can be visualized in Fig. 12. The X-axis shows the time (frames) of the simulation while the Y-axis represents the number of hydrogen bonds formed during the given time. It can be seen that the number of hydrogen formations is consistent over the period with no major fluctuation observed. The results suggest that the interaction maintained the stability of the complexes throughout the simulation.

Fig. 12.

The H-bonding analysis of the top three complexes and control are displayed. The X-axis represents time while the Y-axis indicates H-bonds formed over the period.

MM-PBSA/ GBSA studies

The free energy for the in silico analysis of ligands in protein complexes can be estimated using MM/GBSA energies (Table 6). They offer accuracy between difficult alchemical disturbance and empirical punctuation and are usually based on MD simulations. By calculating its free energy, the CMNPD229-Protease complex demonstrated the best result, with − 120.78 kcal/mol compared to the other compounds. The ZINC000000018635 showed − 107.16 kcal/mol followed by control − 97.49 kcal/mol, while the ZINC000005425464 showed a binding energy of -91 kcal/mol. The ΔG phase energy contributed the most to the overall binding affinity of all the ligands to protease as compared to ΔEvdw and ΔEele.

Table 6.

The free energy calculation statistics of the top three compounds against the protease enzyme.

| Energy Parameter | CMNPD229 | ZINC000000018635 | ZINC000005425464 | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM-GBSA | ||||

| ΔEvdw (kcal/mol) | 102.36 | 94.52 | 85.69 | 88.08 |

| ΔEele (kcal/mol) | 32.69 | 29.13 | 22.42 | 19.66 |

| ΔG phase energy (kcal/mol) | -135.05 | -123.65 | -108.11 | -107.74 |

| ΔE Polar solvation (kcal/mol) | 14.27 | 16.49 | 17.11 | 10.25 |

| Net energy | -120.78 | -107.16 | -91 | -97.49 |

| MM-PBSA | ||||

| ΔEvdw (kcal/mol) | 102.36 | 94.52 | 85.69 | 88.08 |

| ΔEele (kcal/mol) | 32.69 | 29.13 | 22.42 | 19.66 |

| ΔG phase energy (kcal/mol) | -135.05 | -123.65 | -108.11 | -107.74 |

| ΔE Polar solvation (kcal/mol) | 15.59 | 19.37 | 22.01 | 23.01 |

| Net energy | -119.46 | -104.28 | -86.1 | -84.73 |

MD simulation replicate run

A replicated molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was conducted to validate and ensure the reliability of the initial MD results for compound CMNPD229 over a 100-ns timeframe.A Replicate run of the reference drug was also performed. The replicate run RMSD and RMSF analyses from the replicate simulations exhibited a consistent trend, further reinforcing the stability and structural behavior of the complexes. It is evident from the Fig. 13 that compound CMNPD229 maintains relatively higher structural stability with fewer fluctuations. The RMSD values of the compound CMNPD229 remained below 3.5 Å throughout the simulation, except for a few time points where slight deviations are observed. RMSF of both compound CMNPD229 and the reference drug was evaluated over the simulation period. CMNPD22 showed overall lower fluctuations compared to the reference suggesting that it maintains a more stable binding conformation. The fluctuations observed were consistent with the first run, with certain regions showing increased mobility. Certain regions display higher RMSF values, but these fluctuations occur in regions that are away from the active site and do not belong to the binding pocket. The active site itself remains relatively stable, further reinforcing the strong binding stability of CMNPD229. A lower RMSF and RMSD value for CMNPD229 indicates that it remained more stable throughout the simulation.

Fig. 13.

MD simulation results of the replicate run of CMNPD229 and control drug. (A) RMSD and (B) RMSF.

WaterSwap analysis

The present study employed the Bennet, thermodynamic integration (TI), and free energy perturbation (FEP) approaches to determine the absolute free energy of binding of the top four compounds (CMNPD229, ZINC000000018635, ZINC000005425464) and Control. For the calculation of absolute binding, a simulation trajectory file lasting 100 ns was initially used for the estimation of binding energies. Upon visualizing Fig. 14, it became apparent that CMNPD229 showed best by showing the lowest score. The second good score was exhibited by ZINC000000018635 followed by ZINC000005425464 higher than the reference/control complex signifying its potential as a possible drug candidate.

Fig. 14.

shows the complete free energy scores of the top four compounds as determined by the Bennet, TI, FEP, and TI Quadrature techniques.

Entropy calculations

Entropy energy is the technique of estimating the change (randomness) in the system, usually in the context of Protein-ligand interaction in the drug discovery process. By utilizing MDS, the entropy energy for the top 3 complexes along with control was estimated. From Table 7, it was observed in a decrease in the total energy of the CMNPD229, indicating its rigidity upon binding to the protein. The ZINC000000018635 exhibited − 1.09 kcal/mole energy followed by ZINC000005425464 and Control.

Table 7.

The entropy energy scores for the top three complexes and control.

| Complex | Rotational | Vibrational | Translational | ΔS Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMNPD229 | 6.21 | 11.26 | 687.16 | -2.36 |

| ZINC000000018635 | 8.88 | 12.34 | 867.39 | -1.09 |

| ZINC000005425464 | 10.47 | 15.67 | 987.49 | 4.21 |

| Control | 9.56 | 14.98 | 1154.03 | 10.74 |

Salt Bridge studies

Protein folding, molecular recognition, and protein-protein interaction can be assessed by salt bridge studies54. According to molecular dynamics simulations, salt bridges act like molecular clips to maintain the shape of the protein structure, hence stabilizing the protein-ligand complexes. Thus, the creation of salt bridges between ligands and their protein targets might turn out to be a useful tool in the process of computer-aided drug design (CADD)59. The salt bridge is the strongest non-covalent interaction that involves electrostatic attraction between positively and negatively charged atoms60. Upon analyzing the salt bridges of the top 3 complexes along with control (Table 8), it is revealed that the most interaction among the complexes was Glu10- Arg79 and Glu207-lys223, indicating their contribution to overall stability. The CMNPD229 were noted with the more unique interaction as Glu290-Arg23 and Glu305-Lys306. This uniqueness shows that CMPND229 might enhance the structural rigidity and binding affinities. Overall results indicate that the CMNPD229 shows the most unique salt bridge network subsequently ZINC000000018635 ZINC000005425464 and control. These could contribute to them as a potential drug candidate (Figure-S-1 & 2).

Table 8.

The non-covalent interactions of top 3 three complexes as well as the control are given in the following table.

| Complexes | Salt Bridges Interaction |

|---|---|

| CMNPD229 | Glu207-Lys223,Glu120arg79, Glu305-Lys306, Glu205-Lys200, Asp131-Arg23, Glu215-Lys270, Asp153-Arg327, Asp153-Arg327, Asp153-Arg327, Asp131-Arg23, Glu190-Arg342, Asp247-Lys216, Glu284-Arg319, Glu8-Lys350, Asp247-Lys216, Glu284-Arg319, Asp247-Lys243, Glu290-Arg23, Glu8-Lys186, Glu133-Lys67, Asp209-Lys223, Glu279-Lys270, Glu190-Lys340, Glu305-Lys200. |

| ZINC000000018635 | Glu207-Lys223, Glu283-Lys264, Glu11-Lys350, Glu120-Arg79, Glu190-Lys186, Asp131-Arg23, Glu59-Arg86, Asp153-Arg327, Asp153-Arg327, Glu215-Lys270, Glu142-Lys148, Glu346-Arg342, Asp131-Arg23, Glu221-Lys217, Asp57-Arg79, Glu39-Lys67, Asp24-Arg23, Glu59-Lys64, Asp131-Lys65, Glu284-Lys264, Asp131- Lys65, Glu283-Lys264, Glu11-Lys350, Glu133-Lys67 |

| ZINC000005425464 | Glu207-Lys223, Glu283-Lys264, Glu11-Lys350, Glu120-Arg79, Glu190-Lys186, Asp131-Arg23, Glu61-Lys64, Glu215-Lys270, Asp153-Arg327, Glu261-Lys264, Glu59-Arg68, Glu215-Lys270, Glu190-Arg342, Glu201-Arg327, Glu190-Arg342, Asp153-Arg327, Glu61-Arg64,Glu190-Arg342, Asp57-Arg79, Glu59-Lys64, Glu207-Lys223, Glu283-Lys264, Glu279-Lys270, Glu305-Lys200. |

| Control | Glu207-Lys223, Glu120-Arg79, Glu120-Arg79, Glu190-Lys186, Glu59-Arg68, Glu222-Lys223, Asp153-Arg327, Glu261-Lys264, Glu59-Arg68, Asp131-Arg23, Glu142-Lys148, Glu221-Lys217, Glu190-Arg342, Asp131-Arg23, Glu190-Arg342, Asp57-Arg79, Glu284-Arg319, Glu59-Lys64, Glu284-Arg319, Glu59-Lys64, Glu284-Lys340, Asp57-Arg79, Glu284-Arg319, Asp247-Lys243, Glu39-Lys67, Glu8-Lys186, Glu8-Lys186, Glu11-Lys350, Glu190-Lys340, Glu133-Lys67, |

Secondary structure

The MD simulation was carried out at high temperatures utilizing a subset of the force field (Amber ff99SB). The following secondary structure content was assessed using the DSSP algorithm: bend (green), turn (yellow), coils (white), β-sheet (the color red), β-bridge (black), α-helix (blue), as well as helix (grey). From (Figure-S-3 & 4), it is clear that β-sheet and α-helix were preserved throughout the simulation. The Figures S3 and S4 indicate that the overall secondary structure was maintained.

Discussion

Malaria is one of the most serious and widespread tropical parasitic diseases, primarily affecting developing nations61. An integrated strategy is needed to combat malaria, one that addresses both early treatment with potent malaria drugs and prevention62. With the capacity to accelerate and reduce the cost of the drug development process, computer-aided drug design (CADD) is an emerging field that has drawn a lot of interest23. The drug development process is both time-consuming and costly, typically taking 10 to 15 years for a new drug to become commercially available. Computer-aided drug design (CADD) has significantly transformed this field by streamlining research, accelerating discovery, and reducing overall costs63. Another advantage of integrating CADD with machine learning, artificial intelligence (AI), and deep learning is its ability to efficiently manage vast biological datasets while significantly reducing both cost and time in drug discovery64.

One of the novel antimalarial targets is the protease enzyme due to its involvement in the process of invasion and egress of parasites at the pre-erythrocytic and erythrocytic stages65. These two phases are the key checkpoints, where the malaria parasite proliferation can be blocked. The current study aimed to explore and identify novel antimalarial drugs against the said enzyme. The comprehensive study was initiated with the downloading of the crystal structure of the target protein with PDB ID: 7TBD. Initially, the structure was energy-minimized and then underwent detailed structure-based virtual screening. Two compound libraries were used named CMNPD (32000) compounds and ZINC database comprising 10,000 compounds respectively for molecular docking analysis. Evidence from the docking yielded 10 hits compounds based on their binding affinities. The top three compounds CMNPD229, ZINC000000018635, ZINC000005425464, and Control were selected for further computational study along with a control molecule as a reference. The top three compounds were assessed for their ADMET properties to identify their potential as drug-like candidates. The compounds fulfilled the Lipinski Rule 5 criteria and were considered drug-like and suitable for further computational analysis. Next, the quantum-mechanical (QM) technique, DFT was employed to estimate the electronic structure of molecules, atoms, and compounds. The findings suggested that the compound CMNPD229 has lesser energy conformation indicating its potential as the most stable interaction with the target enzyme. Afterward, the PL complexes were subjected to in-silico MDS to find out their interaction with the target enzyme in a dynamic setting. Based on MDS trajectory data, it was visualized that CMNPD229 and reference complex were the most stable followed by ZINC000000018635, ZINC000005425464, and Control. MMPBSA/GBSA, Entropy energy estimation, and WaterSwap calculations revealed that CMPND229 showed a good free energy score followed by ZINC000000018635, Control, and ZINC000005425464. Subsequently, salt bridge interaction revealed that CMNPD229 exhibited the highest number of unique interactions followed by, ZINC000000018635, ZINC000005425464, and Control. This unique interaction can aid in the rigidity and stability of the complex structures making them a potential drug candidate. The PCA findings indicated that the PL showed good diversity in the conformation while H-bonding revealed that the PL complexes were stable in generating H-bonds throughout the simulation period (frames) indicating its stability. These findings can aid in the development of novel antimalarial drug candidates by providing a basis for experimental validation66. performed virtual screening against a library of 1,535,478 compounds using homology modeling of PMV structure, molecular docking, and pharmacophore modeling. The results generated 233 top compounds. Four non-peptidomimetic compounds with mean IC50 values of 6.67 µM, 12.55 µM, 5.10 µM, and 8.31 µM demonstrated promising reduction of parasite development when their antimalarial characteristics were evaluated. These candidates revealed no obvious impact on the viability of L929 cells. Using H-bond, halogen bond, hydrophobic, or π-π interactions in molecular docking, these four compounds showed high binding activities with the Pf PMV model, with binding values around − 9.0 kcal/mol.

Since CADD has certain limitations including. At this intersection of drug development, the biological and therapeutic importance of CADD outputs must be verified by thorough experimental validation. The interaction between the computational and experimental realms is required to determine a drug’s maximum efficacy.

Conclusions

Malaria is one of the most devastating and extensively spread tropical parasite diseases, mostly using various computational analyses to explore novel inhibitors against the aspartic protease. The study yielded three hits CMNPD229, ZINC000000018635, and ZINC000005425464. Subsequently, MD simulations and MM-PBSA/GBSA analysis revealed CMNPD229 as the most potent and stable inhibitor for aspartic protease. Furthermore, emphasis should also be placed on the need for further study, as the data gathered here is solely relevant to computational analyses and demands experimental validation both in vitro and in vivo.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

M.A., H.H.A., H.A., and M.T.Q. contributed to the research and manuscript preparation. M.A. and H.H.A. wrote the main manuscript text. H.A. and M.T.U.Q. supervised the project and reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research is funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University through the Fast-Track Research Funding Program.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in the text and in Figures 9, 10, and 12. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

9/3/2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-025-17853-x

References

- 1.Makam, P. & Matsa, R. Big three infectious diseases: tuberculosis, malaria and HIV/AIDS. Curr. Top. Med. Chem.21, 2779–2799 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hotez, P. J. Forgotten People, Forgotten Diseases: the Neglected Tropical Diseases and their Impact on Global Health and Development (Wiley, 2021).

- 3.Patel, P., Bagada, A. & Vadia, N. Epidemiology and current trends in malaria. Rising Contagious Diseases: Basics Manage. Treatments 261–282. 10.1002/9781394188741.ch20 (2024).

- 4.Koepfli, C. et al. Identification of the asymptomatic plasmodium falciparum and plasmodium Vivax gametocyte reservoir under different transmission intensities. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.15, 1–18 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sivaramakrishnan, M. et al. Molecular Docking and dynamics studies on plasmepsin V of malarial parasite plasmodium Vivax. Inf. Med. Unlocked. 19, 100331 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fatmaningsih, L., Samasta, N. A. & Octa, L. Differences in the life cycle and growth of plasmodium Knowlesi, Inui, Vivax, malariae, falciparum, ovale. J. Biomedical Techno Nanomaterials. 1, 59–69 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alemayehu, A. Biology and epidemiology of plasmodium falciparum and plasmodium Vivax gametocyte carriage: implication for malaria control and elimination. Parasite Epidemiol. Control. 21, e00295 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angrisano, F. & Robinson, L. J. Plasmodium vivax–How hidden reservoirs hinder global malaria elimination. Parasitol. Int.87, 102526 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delahunt, C. B., Gachuhi, N. & Horning, M. P. Use case-focused metrics to evaluate machine learning for diseases involving parasite loads. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.06947 3, (2022).

- 10.Andagalu, B. et al. Longitudinal study on Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte carriage following artemether-lumefantrine administration in a cohort of children aged 12–47 months living in Western Kenya, a high transmission area. Malar. J.13, 1–9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Ferreira, M. U. et al. Monitoring plasmodium Vivax resistance to antimalarials: persisting challenges and future directions. Int. J. Parasitology: Drugs Drug Resist.15, 9–24 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stiffler, D. M. et al. HIV-1 infection is associated with increased prevalence and abundance of plasmodium falciparum gametocyte-specific transcripts in asymptomatic adults in Western Kenya. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.10, 600106 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Jong, R. M. et al. Immunity against sexual stage Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax parasites. Immunol. Rev.293, 190–215 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bousema, T. & Drakeley, C. Epidemiology and infectivity of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax gametocytes in relation to malaria control and elimination. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.24, 377–410 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheuka, P. M., Dziwornu, G., Okombo, J. & Chibale, K. Plasmepsin inhibitors in antimalarial drug discovery: medicinal chemistry and target validation (2000 to present). J. Med. Chem.63, 4445–4467 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahanta, P. J. & Lhouvum, K. Plasmodium falciparum proteases as new drug targets with special focus on metalloproteases. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol.111617. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2024.111617 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Deu, E. Proteases as antimalarial targets: strategies for genetic, chemical, and therapeutic validation. FEBS J.284, 2604–2628 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boss, C. et al. Inhibitors of aspartic proteases–potential antimalarial agents. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat.16, 295–317 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christensen, P. R. Pre-clinical investigations of repurposed and novel therapeutics for treatment of drug resistant malaria; with special reference to Plasmodium vivax and its sister species Plasmodium cynomolgi. Preprint at (2021).

- 20.Shibeshi, M. A., Kifle, Z. D. & Atnafie, S. A. Antimalarial drug resistance and novel targets for antimalarial drug discovery. Infect. Drug Resist.13, 4047–4060 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Siqueira-Neto, J. L. et al. Antimalarial drug discovery: progress and approaches. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 22, 807–826 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anwar, T., Kumar, P. & Khan, A. U. Modern tools and techniques in computer-aided drug design. In Molecular Docking for computer-aided Drug Design (Coumar, M. S. ed.) 1–30 (Elsevier, (2021).

- 23.dos Santos Nascimento, I. J., da Silva Rodrigues, É. E., da Silva, M. F., de Araújo-Júnior, J. X. & de Moura R. O. Advances in computational methods to discover new NS2B-NS3 inhibitors useful against dengue and Zika viruses. Curr. Top. Med. Chem.22, 2435–2462 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oselusi, S. O. et al. The role and potential of computer-aided drug discovery strategies in the discovery of novel antimicrobials. Comput. Biol. Med.169, 107927 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Dallakyan, S. & Olson, A. J. Small-molecule library screening by Docking with pyrx. Chem. Biology: Methods Protocols.1263, 243–250 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Bilal, M. S. et al. Computational Investigation of 1, 3, 4 Oxadiazole Derivatives as Lead Inhibitors of VEGFR 2 in Comparison with EGFR: Density Functional Theory, Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Studies. Biomolecules 12, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.El-Shamy, N. T. et al. DFT, ADMET and molecular Docking investigations for the antimicrobial activity of 6, 6′-Diamino-1, 1′, 3, 3′-tetramethyl-5, 5′-(4-chlorobenzylidene) Bis [pyrimidine-2, 4 (1H, 3H)-dione]. Molecules27, 620 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohammad, T. et al. Impact of amino acid substitution in the kinase domain of Bruton tyrosine kinase and its association with X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.164, 2399–2408 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shivaleela, B., Hanagodimath, S. M. & UV-Visible Spectra HOMO-LUMO Studies on Coumarin Derivative Using Gaussian Software. (2020).

- 30.Rieder, S. R. et al. Replica-Exchange enveloping distribution sampling using generalized AMBER Force-Field topologies: application to relative hydration Free-Energy calculations for large sets of molecules. J. Chem. Inf. Model.62, 3043–3056 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kharisma, V. D., Ansori, A. N. M. & Nugraha, A. P. Computational study of ginger (Zingiber Officinale) as E6 inhibitor in human papillomavirus type 16 (Hpv-16) infection. Biochem. Cell. Archives. 20, 3155–3159 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makhlouf, J. et al. Growth, single crystal investigations, Hirshfeld surface analysis, DFT studies, molecular dynamics simulations, molecular docking, physico-chemical characterization and biological activity of novel thiocyanic complex with zinc transition metal precursor. Polyhedron222, 115937 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han, Y. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Bioactive Complexes, Nanoparticles and Polymers. Preprint at (2021).

- 34.Bhatt, P. et al. Binding interaction of glyphosate with glyphosate oxidoreductase and C–P lyase: molecular Docking and molecular dynamics simulation studies. J. Hazard. Mater.409, 124927 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ranade, S. S. & Ramalingam, R. Hydrogen bonds in Anoplin peptides aid in identification of a structurally stable therapeutic drug scaffold. J. Mol. Model.26, 1–13 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, R. et al. Donor-acceptor anchoring nanoarchitectonics in polymeric carbon nitride for rapid charge transfer and enhanced visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. Carbon197, 378–388 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wan, S., Bhati, A. P., Zasada, S. J. & Coveney, P. V. Rapid, accurate, precise and reproducible ligand–protein binding free energy prediction. Interface Focus. 10, 20200007 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miandad, K. et al. Virtual screening of Artemisia annua phytochemicals as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease enzyme. Molecules27, 1–13 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hashem, H. E., Ahmad, S., Kumer, A. & Bakri, Y. El. In Silico and in vitro prediction of new synthesized N-heterocyclic compounds as anti-SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Rep.14, 1152 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karnik, K. S., Sarkate, A. P., Jambhorkar, V. S. & Wakte, P. WaterSwap analysis, a Computation-based method for the discovery of effective and stable binding compounds for mutant EGFR Inhibition. (2021).

- 41.Raju, B. et al. Identification of potential Benzoxazolinones as CYP1B1 inhibitors via molecular docking, dynamics, waterswap, and in vitro analysis. New J. Chem.47, 12339–12349 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huai, Z., Shen, Z. & Sun, Z. Binding thermodynamics and interaction patterns of inhibitor-major urinary protein-I binding from extensive free-energy calculations: benchmarking AMBER force fields. J. Chem. Inf. Model.61, 284–297 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rani, P. et al. Unravelling the thermodynamics and binding interactions of bovine serum albumin (BSA) with thiazole based carbohydrazide: Multi-spectroscopic, DFT and molecular dynamics approach. J. Mol. Struct.1270, 133939 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Selvaraj, C., Rudhra, O., Alothaim, A. S., Alkhanani, M. & Singh, S. K. Structure and chemistry of enzymatic active sites that play a role in the switch and conformation mechanism. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biology. 130, 59–83 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pereira, G. P. & Cecchini, M. Multibasin quasi-harmonic approach for the calculation of the configurational entropy of small molecules in solution. J. Chem. Theory Comput.17, 1133–1142 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shukla, R. & Tripathi, T. Molecular dynamics simulation of protein and protein–ligand complexes. Computer-aided Drug Des. 133–161 (2020).

- 47.de Paiva, A. Protein structural bioinformatics: an overview. Comput. Biol. Med.147, 105695 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skånberg, R., Falk, M., Linares, M., Ynnerman, A. & Hotz, I. Tracking internal frames of reference for consistent molecular distribution functions. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph.28, 3126–3137 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yasuda, T., Shigeta, Y. & Harada, R. Efficient conformational sampling of collective motions of proteins with principal component analysis-based parallel cascade selection molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Inf. Model.60, 4021–4029 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lombard, V., Grudinin, S. & Laine, E. Explaining conformational diversity in protein families through molecular motions. Sci. Data. 11, 752 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu, Z., Chen, E., Zhang, S., Ma, Y. & Mao, Y. Visualizing conformational space of functional biomolecular complexes by deep manifold learning. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 8872 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun, S., Poudel, P., Alexov, E. & Li, L. Electrostatics in computational biophysics and its implications for disease effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 10347 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gupta, M. N. & Uversky, V. N. Biological importance of arginine: A comprehensive review of the roles in structure, disorder, and functionality of peptides and proteins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.128646 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Panja, A. S., Maiti, S. & Bandyopadhyay, B. Protein stability governed by its structural plasticity is inferred by physicochemical factors and salt bridges. Sci. Rep.10, 1822 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng, X. et al. Emerging affinity methods for protein-drug interaction analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal.249, 116371 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Miles, A. J., Ramalli, S. G. & Wallace, B. A. DichroWeb, a website for calculating protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectroscopic data. Protein Sci.31, 37–46 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ma, Y. et al. Medicinal chemistry strategies for discovering antivirals effective against drug-resistant viruses. Chem. Soc. Rev.50, 4514–4540 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dutta, T., Pesce, E. R., Maier, A. G. & Blatch, G. L. Role of the J domain protein family in the survival and pathogenesis of plasmodium falciparum. Heat. Shock Proteins Malar. 1340, 97–123 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Spassov, D. S., Atanasova, M. & Doytchinova, I. A role of salt bridges in mediating drug potency: A lesson from the N-myristoyltransferase inhibitors. Front. Mol. Biosci.9, 1066029 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Padilla-Bernal, G., Vargas, R. & Martínez, A. Salt Bridge: key interaction between antipsychotics and receptors. Theor. Chem. Acc.142, 65 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Price, R. N., Commons, R. J., Battle, K. E., Thriemer, K. & Mendis, K. Plasmodium Vivax in the era of the shrinking P. falciparum map. Trends Parasitol.36, 560–570 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ansah, E. K., Moucheraud, C., Arogundade, L. & Rangel, G. W. Rethinking integrated service delivery for malaria. PLOS Global Public. Health. 2, e0000462 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arora, A., Kaur, S. & Singh, A. Challenges and emerging problems in CADD. Drug Delivery Syst. Using Quantum Comput. 407–441. 10.1002/9781394159338.ch14 (2024).

- 64.Satpathy, R. Artificial intelligence techniques in the classification and screening of compounds in Computer-Aided drug design (CADD) process. Artif. Intell. Mach. Learn. Drug Des. Dev.10.1002/9781394234196.ch15. 473–497 (2024).

- 65.Mitiku, T. & Abebe, B. Molecular machinery of malaria infection: insights into Host-parasite interactions and therapeutic targets. Asian J. Res. Biosci.6, 79–95 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ji, X. et al. In Silico and in vitro antimalarial screening and validation targeting plasmodium falciparum plasmepsin V. Molecules27, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.