Abstract

Iodinated contrast media (ICM) are extensively utilized in medical imaging to enhance tissue contrast, yet their impact on thyroid function has attracted increasing attention in recent years. ICM can induce thyroid dysfunction, with reported prevalence ranging from 1 to 15% and a higher incidence observed in individuals with pre-existing thyroid conditions or other risk factors like age, gender, underlying health issues, and repeated ICM exposure. This review summarized the classification of ICM and the potential mechanisms, risk assessment, and clinical management of ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction, especially in vulnerable populations such as pregnant women and elderly patients. Despite advancements that have enriched our understanding of the pathophysiology and treatment of ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction, critical knowledge gaps remain, such as the long-term effects of ICM on thyroid function, the dose–response relationship between ICM volume and thyroid dysfunction risk, and the ecological impacts of ICM. Therefore, further exploration of the underlying mechanisms of ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction and optimization of the management strategies will be crucial for the safe and effective use of ICM in clinical practice, and collaborative efforts between clinicians and researchers are essential to ensure that the risks of thyroid dysfunction do not outweigh the benefits of imaging.

Keywords: Iodinated contrast media, Thyroid dysfunction, Iodine overload, Hyperthyroidism, Hypothyroidism

Introduction

Iodine, a crucial element for thyroid hormone synthesis, can disrupt thyroid function when present in excess, causing iodine-induced hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism [1]. Iodinated contrast media (ICM) are essential radiopaque agents widely used in modern radiology, particularly in computed tomography (CT) and angiography, for their ability to enhance tissue contrast. By improving diagnostic accuracy, ICM supports the detection and planning of treatment for various conditions, including vascular diseases, tumors, and other pathologies. Despite their significant role in clinical practice, ICM use carries inherent risks, particularly regarding thyroid function [2, 3]. Given the thyroid gland’s sensitivity to iodine, ICM can trigger thyroid dysfunctions, including hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, and autoimmune disorders such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Graves’ disease [4–7]. Studies have reported the prevalence of ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction to range from 1 to 15% [8], with a higher incidence among individuals with pre-existing thyroid conditions or other risk factors like age, gender, underlying health issues, and repeated ICM exposure [9].

The potential impact of ICM on thyroid function emphasizes the need for clinicians to understand its effects and carefully monitor high-risk populations. ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction may present with various symptoms, such as fatigue, weight fluctuations, cardiovascular disturbances, and mood changes, that can severely affect both physical and mental health if untreated. For instance, untreated hypothyroidism may lead to metabolic deceleration, weight gain, and depression, while hyperthyroidism can cause weight loss, increased heart rate, anxiety, and heat intolerance [6, 7]. Pharmacovigilance studies have increasingly highlighted thyroid-related adverse events following ICM administration [5], stressing the importance of awareness among healthcare providers. However, the mechanisms underlying ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction are complex, including direct and indirect pathways, such as iodine metabolism alterations, inhibition of thyroid hormone synthesis, thyroid gland autoregulation, peripheral thyroid hormone metabolism, and potential autoimmune responses [4]. Specific populations, such as children and those with a thyroid disease history, are particularly vulnerable [10].

Therefore, understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing strategies to minimize the impact of ICM on thyroid health and ensure proactive management in susceptible groups [1, 5, 11, 12]. This review aims to comprehensively examine the effects of ICM on thyroid function, offering insights into the underlying mechanisms, risk assessment, and clinical management strategies. By synthesizing the latest evidence, we seek to inform clinical decision-making, optimize patient management for those at risk, and contribute to the development of preventive and safe imaging practices.

Types of ICM and their mechanisms of action

ICM are primarily classified into ionic and non-ionic types, and the differences between the two types of ICM are shown in Table 1. Ionic ICM, such as diatrizoate and ioxaglate, have higher osmolality and dissociate into charged particles, thereby increasing the risk of adverse reactions, including contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) and allergic responses. For instance, ioxaglate has been shown to induce more apoptosis in renal tubular cells, particularly in diabetic patients, compared to non-ionic counterparts [13]. Conversely, non-ionic agents like iohexol and iodixanol do not dissociate and exhibit lower osmolality, resulting in fewer side effects and improved patient tolerance during imaging procedures. This makes them the preferred choice in clinical practice. Some studies suggest that iodixanol may pose a slightly lower risk for CIN than low-osmolar ionic agents, although the clinical significance of this difference remains debated [14]. The selection of an appropriate ICM is influenced by multiple factors, including the patient’s renal function, the specific imaging modality or diagnostic requirements, and any history of allergic reactions [13–15]. For patients with compromised renal function, non-ionic ICM are generally preferred to mitigate the risk of CIN [13, 14]. Overall, non-ionic agents are preferentially recommended for patients with renal impairment or a history of iodine-related allergies due to their reduced immunogenic potential and maintained diagnostic efficacy [16–18]. Additionally, the pharmacokinetics of ICM, including their distribution, metabolism, and excretion, play a crucial role in their efficacy and safety [17]. Understanding these parameters helps clinicians select the most suitable agent for each patient, thereby minimizing risks while maximizing diagnostic yield.

Table 1.

Difference between the two types of ICM

| Parameter | Ionic ICM | Non-ionic ICM |

|---|---|---|

| Representative drugs | e.g., diatrizoate, ioxaglate | e.g., iohexol, iodixanol |

| Chemical structure | Dissociate into charged particles in solution | Non-dissociating, more stable moleculr structure |

| Osmolality | Higher osmolality | Lower osmolality |

| Adverse reactions | Higher risk of adverse reactions, such as discomfort during injection, nephrotoxicity, and HSRs | Better patien tolerance, reduced risk of nephrotoxicity and HSRs |

| Renal safety | Avoid in renal impairment | Preferred in CKD patients |

| Cytotoxicity | Induces apoptosis in renal tubular cells | Reduced oxidative stress and cellular damage |

| Clinical preference | Limited use due to side effects | First-line for high-risk populations |

ICM, iodinated contrast media; HSRs, hypersensitivity reactions; CKD, chronic kidney disease

ICM are essential in medical imaging, primarily due to their biochemical properties, particularly the high atomic number of iodine, which enhances X-ray absorption and radiopacity. Upon administration, ICM are rapidly distributed throughout the vascular system and predominantly excreted unchanged via the kidneys, highlighting the importance of assessing renal function to mitigate risks of nephrotoxicity, especially in patients with pre-existing kidney issues [17, 19–21]. The physicochemical properties of ICM, including solubility, viscosity, and osmolality, significantly influence their behavior in biological systems. High water solubility and viscosity can hinder renal clearance and exacerbate acute kidney injury by increasing cytotoxic retention [22, 23]. Furthermore, osmolality variations between iso-osmolar and low-osmolar formulations affect renal kinetics and can lead to cellular injury markers, such as vacuole formation in renal cells [23]. Cytotoxicity is another significant concern associated with ICM. In vitro studies have demonstrated that elevated concentrations of ICM can diminish endothelial cell viability and promote apoptosis, highlighting the necessity for careful consideration of the concentration and formulation of ICM used in clinical practice to minimize adverse effects [24]. Additionally, previous studies have indicated the potential for ICM to induce oxidative stress, which can lead to cellular damage and adverse reactions. For example, the contrast agent 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (TIBA) has been shown to induce cell death in tumor cells by generating reactive oxygen species [25]. Emerging alternatives, such as nanosized triiodoaniline derivatives, show promise in reducing cytotoxicity while maintaining effective imaging capabilities [26]. Therefore, understanding these biochemical characteristics is critical for optimizing ICM use and ensuring patient safety during diagnostic procedures. Ongoing research is essential to optimize these properties and develop new formulations that enhance diagnostic capabilities while minimizing risks.

Iodine, an essential micronutrient, plays a pivotal role in synthesizing thyroid hormones, namely thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), which are crucial for regulating metabolism, growth, and development. The thyroid gland’s absorption of iodine directly influences hormone production. Insufficient iodine intake may lead to hypothyroidism and goiter, whereas excessive intake may lead to hyperthyroidism and an increased risk of thyroid cancer [27–30], particularly in populations with prior low iodine levels [29], highlighting the complex relationship between iodine levels and thyroid pathology. The use of ICM in imaging has raised concerns regarding their impact on thyroid function, especially in individuals with pre-existing thyroid conditions or those receiving high doses of contrast [31]. Studies indicate that excessive exposure to ICM can alter thyroid hormone levels and function, necessitating vigilance in monitoring thyroid health among at-risk populations. Genetic predispositions and environmental conditions also modulate the thyroid gland’s response to iodine. For example, single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR) gene may further modulate this response [32]. Additionally, the role of ion transporters in mediating iodine uptake and metabolic processes within thyroid cells further complicates the relationship between iodine and thyroid health [33]. Overall, the relationship between iodine and the thyroid gland is characterized by a delicate balance. While ICM are indispensable in imaging, their implications for thyroid health require careful patient assessment and monitoring to ensure safety and effective management of thyroid disorders, particularly in those with a history of thyroid disease [34].

Potential mechanisms of thyroid dysfunction induced by ICM

ICM may precipitate thyroid dysfunction, clinically presenting as hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism (Table 2), with heightened susceptibility observed in individuals with pre-existing thyroid disorders and/or chronic exposure to iodine-deficient environments [8]. Hyperthyroidism is more common in patients with underlying conditions such as nodular goiter or latent Graves’ disease, especially in iodine-deficient areas. Conversely, hypothyroidism often occurs in patients with autoimmune thyroiditis, particularly in regions with adequate iodine supply. The mechanisms behind these dysfunctions include the perturbation of iodide uptake by the thyroid, occurring independently of free iodide levels in ICM [35]. Prophylactic measures, such as the administration of antithyroid drugs, may reduce the incidence of ICM-induced hyperthyroidism [36], and monitoring thyroid function before and after ICM exposure is crucial, especially in at-risk populations [37].

Table 2.

Comparison of the ICM-induced hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism

| Feature | Hyperthyroidism | Hypothyroidism |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Jod-Basedow effect (iodine excess stimulates hormone release) | Wolff-Chaikoff effect (transient suppression of hormone synthesis) |

| Risk factors | Nodular goiter, latent Graves’ disease, high baseline FT4 level, iodine-deficient regions, age over 60, male gender, a family history of thyroid diseases | Autoimmune thyroiditis, iodine-sufficient regions, high dose of ICM, pre-existing thyroid dysfunction, a history of thyroid surgery |

| Key biomarkers | TSH↓, FT4/FT3↑ | TSH↑, FT4↓ |

| Clinical management | Antithyroid medications (e.g., methimazole or propylthiouracil), β-blockers, radioiodine therapy or surgical intervention | Levothyroxine replacement |

| Long-term outcomes | May persist even after one year | Mostly transient |

ICM, iodinated contrast media; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; FT4, free thyroxine; FT3, free triiodothyronine

Impact of iodine load on thyroid function

Iodine load from ICM significantly impacts thyroid function by influencing hormone synthesis. Iodine is essential for thyroid hormone production, and its excess can lead to both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Mechanisms include alterations in iodine uptake and metabolism by thyroid cells and potential cytotoxic effects of ICM [38, 39]. Acute iodine load may precipitate hyperthyroidism through the Jod-Basedow phenomenon, predominantly affecting individuals with autonomously functioning thyroid nodules or specific pre-existing thyroid pathologies, particularly Graves’ disease in remission and multinodular goiter with functional autonomy, wherein excessive iodine exposure bypasses normal regulatory mechanisms to drive unregulated hormone synthesis. Conversely, excessive iodine can trigger the Wolff-Chaikoff effect, temporarily inhibiting hormone synthesis, which may lead to subsequent hypothyroidism [38, 40, 41]. In patients with ischemic heart disease (IHD), ICM administration has been linked to increased hyperthyroidism prevalence, positively correlated with baseline free T4 levels, thyroid nodules, and family history of thyroid diseases [42]. Some patients continue to exhibit hyperthyroidism even one year post-ICM exposure [42], indicating a potential long-term effect of iodine load on thyroid function. Additionally, populations with WHO-recommended iodine intake (median urinary iodine concentration 100–199 μg/L for adults) and normal thyroid functionmay may still experience subtle thyroid function changes due to fluctuations in iodine levels [43], suggesting that the thyroid gland may be sensitive to iodine level variations, particularly relevant in ICM administration. The relationship between iodine load and thyroid dysfunction is complex, necessitating vigilant monitoring and individualized management strategies to mitigate potential adverse effects on thyroid health.

Direct toxicity of ICM on thyroid tissue

ICM can cause significant damage to thyroid tissue through direct cytotoxicity, apoptosis, and inflammation. Studies show that ICM disrupt iodide uptake by reducing the expression of the sodium-iodide symporter, impairing hormone synthesis and causing cellular stress [35]. This disruption triggers a cascade of oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, further exacerbating thyroid cell injury [44]. Apoptosis is a crucial mechanism, as ICM exposure has been associated with increased levels of reactive oxygen species and subsequent activation of apoptotic signaling cascades [3, 45]. In addition to direct cellular effects, ICM interaction with thyroid hormones and their regulatory pathways may exacerbate inflammatory responses, contributing to further tissue damage, including fibrosis [44]. These combined effects may lead to both acute and chronic thyroid dysfunction, potentially resulting in long-term consequences for patients undergoing imaging procedures utilizing ICM [35, 39, 45]. The evidence suggests that ICM not only disrupt iodide uptake but also induce apoptosis and inflammatory responses in thyroid tissue, highlighting the need for careful monitoring of thyroid function in patients undergoing ICM administration, particularly those with pre-existing thyroid conditions or at risk for thyroid dysfunction [35, 44]. Understanding these mechanisms can guide risk assessment and management strategies, helping to minimize adverse thyroid outcomes in clinical settings [1].

Autoimmune reactions and thyroid dysfunction induced by ICM

ICM have been implicated in the induction of autoimmune thyroid diseases, particularly in genetically predisposed individuals. The introduction of exogenous iodine can trigger an immune response, potentially leading to conditions such as Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis [3]. This autoimmune response may be explained by molecular mimicry, where iodine-containing compounds resemble thyroid antigens, prompting the immune system to attack thyroid tissue [46, 47]. Clinical studies indicate an increase in thyroid autoantibodies following ICM exposure, suggesting a significant link between contrast administration and autoimmune thyroid dysfunction [3, 11, 46]. Moreover, ICM exposure can result in varying degrees of thyroid dysfunction, from transient hyperthyroidism to chronic hypothyroidism [39, 48, 49]. Notably, cases of thyrotoxicosis secondary to destructive thyroiditis have been reported after ICM administration, characterized by the rapid release of preformed thyroid hormones, which can result in significant clinical symptoms, especially in patients with unstable cardiac conditions [50]. Delayed hypersensitivity reactions to ICM can manifest as various cutaneous symptoms, which may be underdiagnosed due to misattribution to other medications [51]. A multicenter study involving over 196,000 patients revealed a prevalence of hypersensitivity reactions to ICM, with certain risk factors identified, including a history of drug allergies and previous hypersensitivity reactions [52]. Understanding these associations is crucial for developing preventive strategies and management protocols and ensuring optimal care for patients undergoing imaging procedures involving ICM. Continued research is essential to elucidate the mechanisms behind these reactions and to enhance patient safety in clinical practice.

Risk assessment and clinical management of ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction

Risk assessment strategies for patients receiving ICM

ICM use in radiographic procedures can lead to thyroid dysfunction, particularly in vulnerable populations, highlighting the need for thorough risk assessment strategies [53]. Studies have shown a significant link between ICM exposure and the onset of thyroid disorders, particularly hypothyroidism, even in individuals without prior thyroid issues. For example, a large-scale study in Taiwan reported an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.17 for developing thyroid disorders following ICM exposure [54], highlighting the importance of proactive monitoring. Although the prevalence of iodine-induced hyperthyroidism is generally low, it remains a clinically relevant concern [55], even in pediatric populations, where thyroid function monitoring is critical, especially for those with congenital heart disease who undergo multiple imaging studies. Additionally, research on children has identified transient decreases in thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels following ICM exposure [56]. A comprehensive risk assessment protocol should include pre-procedure screening to identify patients with a history of thyroid disorders, autoimmune conditions, or medications (such as amiodarone) known to affect thyroid function [11]. Baseline thyroid function tests, including serum TSH, free triiodothyronine (FT3), and free thyroxine (FT4) levels, are essential, particularly for high-risk groups such as the elderly or those with renal impairment [38]. Post-procedure follow-up should reassess thyroid function within weeks to detect any abnormalities early. Educating patients on recognizing potential symptoms of thyroid dysfunction, such as weight changes and fatigue, facilitates timely detection. In cases of abnormal test results, prompt referral to an endocrinologist for evaluation and management may be necessary [57]. By adopting these strategies, healthcare providers can mitigate the risks associated with ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction, improving patient outcomes in radiographic imaging.

Monitoring and management of ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction

Effective monitoring and management of ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction are essential for patient safety [57]. After ICM exposure, an iodine load can initiate the Wolff-Chaikoff effect, temporarily reducing thyroid hormone synthesis. Infants and patients with compromised thyroid function may experience prolonged hypothyroidism if they cannot adequately escape this effect [58]. For instance, a case involving a preterm infant demonstrated severe hypothyroidism after enteral ICM administration, highlighting the need for vigilant monitoring in vulnerable groups [58]. Thyroid function, especially TSH and free thyroid hormone levels, should be reassessed within the first three months following ICM exposure, as this period presents the highest incidence of dysfunction [5, 56]. Clinicians should monitor for symptoms of thyroid dysfunction, such as fatigue, weight fluctuations, and cognitive changes [5]. Management strategies should be tailored to the severity of the dysfunction. Mild cases may only require observation, while moderate to severe cases may necessitate treatment, including levothyroxine replacement for hypothyroidism or antithyroid drugs for hyperthyroidism [38, 53, 58]. Clinicians should also be aware of potential delayed allergic reactions to ICM, which may complicate thyroid management [59]. A multidisciplinary approach involving endocrinologists and allergists can enhance patient care in these cases. Systematic monitoring and timely interventions are crucial to minimizing risks associated with ICM and promoting better health outcomes.

Treatment options for ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction

Managing ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction requires an individualized approach based on the patient’s condition and overall health. For iodine-induced hyperthyroidism, antithyroid medications such as methimazole or propylthiouracil may be prescribed, along with beta-blockers to alleviate symptoms like tachycardia [60, 61]. In severe cases, radioactive iodine therapy or surgical intervention may be necessary. In severe cases, radioiodine therapy or surgical intervention may be necessary. However, radioiodine therapy may be precluded for several months by iodine excess from sources like ICM, as residual iodine competitively inhibits thyroid uptake and diminishes the efficacy of radioiodine therapy [62, 63]. In such cases, urinary iodine monitoring must confirm biochemical clearance before radioiodine therapy initiation, and alternative treatments may need to be considered temporarily, such as antithyroid drugs or even surgical options, until radioiodine therapy becomes viable [64, 65]. Hypothyroidism generally necessitates levothyroxine replacement, with dose adjustments guided by periodic TSH/FT4 monitoring [1, 61]. Patient education is crucial in recognizing thyroid dysfunction symptoms and is essential to support early detection and intervention [61, 66]. For high-risk individuals, alternative imaging methods such as MRI or ultrasound should be considered to avoid ICM exposure [67]. Regular follow-up and thyroid function testing are critical for those with prior thyroid dysfunction after ICM exposure, ensuring any persistent or emerging issues are promptly addressed [68]. By integrating monitoring, treatment, patient education, and alternative imaging options, healthcare providers can manage ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction effectively, leading to better patient outcomes [69].

Best practices for ICM use to avoid thyroid dysfunction

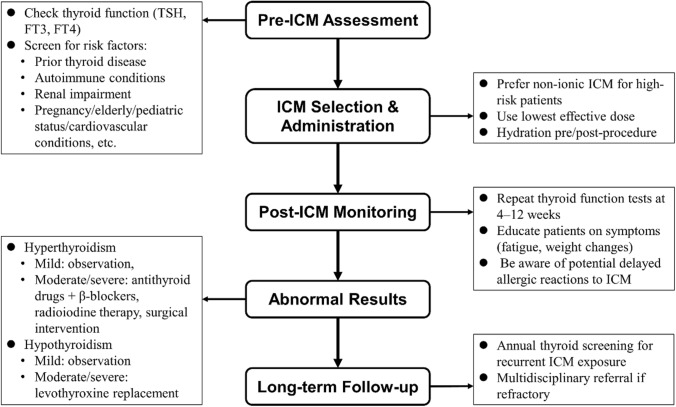

Adhering to best practices for ICM use is essential to minimize thyroid dysfunction risks in patients undergoing imaging (Fig. 1). Clinicians should follow established guidelines, using ICM judiciously and only when its diagnostic benefits outweigh potential risks [57, 70]. Pre-procedural thyroid screening should be standard for high-risk individuals, such as those with prior thyroid disease or renal impairment [1, 58, 71]. Using the lowest effective ICM dose and considering non-iodinated alternatives when feasible can also reduce risk. Proper hydration before and after ICM administration supports renal function and indirectly reduces thyroid complications [58, 72]. Prioritizing iso-osmolar contrast agents further mitigates risks [73, 74]. Educating patients on potential side effects and scheduling follow-up thyroid function tests, particularly for at-risk groups, are vital steps in patient care [55, 58]. Following updated clinical guidelines, such as those from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, can help providers implement best practices in ICM use. Continued research on the effects of ICM on thyroid function will aid in refining these guidelines and improve patient safety [55, 74].

Fig. 1.

The flow diagram of the clinical management algorithm for ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction

ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction in vulnerable populations

Patients with pre-existing thyroid disease

Patients with underlying thyroid conditions are particularly vulnerable to ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction. ICM can disrupt iodide uptake, exacerbating both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism [54]. In individuals with autoimmune thyroid diseases, particularly Graves’ disease, ICM exposure may transiently elevate thyroid hormone levels, worsening hyperthyroid symptoms [4, 75, 76]. Those with a history of thyroid disorders are at higher risk for developing thyroid dysfunction post-contrast exposure, highlighting the need for careful monitoring of thyroid function both before and after imaging procedures [5, 77]. The excessive iodine load from ICM can induce iodine-induced hyperthyroidism or exacerbate pre-existing hyperthyroidism, particularly in patients with autoimmune conditions like Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Evidence suggests that repeated exposure to ICM may impair the thyroid gland’s auto-regulatory mechanisms, leading to significant hormonal fluctuations and long-term dysfunction [1, 4, 54]. For patients with known thyroid dysfunction, thorough thyroid function assessments pre- and post-ICM administration are critical. Adjustments in thyroid hormone replacement therapy may be necessary to maintain euthyroid status. A multidisciplinary approach, including endocrinology consultation, is essential to promptly address any thyroid abnormalities, ensuring optimal outcomes and minimizing complications.

Pregnant women

The use of ICM during pregnancy carries potential risks for both maternal and fetal thyroid function [11]. The fetal thyroid becomes active early in gestation, and excess iodine from ICM may impair normal hormone synthesis, increasing the risk of fetal hypothyroidism or congenital thyroid disorders [78]. Maternal thyroid dysfunction, compounded by ICM exposure, is associated with neurodevelopmental risks in offspring, including an increased likelihood of autism spectrum disorders [79]. Given these risks, clinicians must carefully evaluate the necessity of ICM-based imaging during pregnancy. Whenever possible, non-iodinated imaging modalities should be preferred [80]. If ICM use is unavoidable, close monitoring of thyroid function in both the mother and newborn is essential to detect and manage any dysfunction promptly. Special attention is warranted for first-trimester exposures, as the developing fetal thyroid is particularly sensitive during this period [11]. Long-term effects of in-utero ICM exposure remain unclear, further emphasizing the need for caution. A collaborative, multidisciplinary approach involving obstetricians and endocrinologists ensures comprehensive care. Informed decision-making and individualized management are crucial to balance diagnostic needs with the safety of both mother and fetus [80].

Elderly population

Elderly patients are particularly susceptible to ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction due to age-related physiological changes, a higher prevalence of thyroid disorders, and altered pharmacokinetics [5, 81, 82]. Thyroid dysfunction affects over 10% of older adults [83], and ICM exposure may exacerbate pre-existing thyroid abnormalities. This population is at increased risk for iodine-induced hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, particularly in those with baseline thyroid disorders. In clinical settings, procedures such as coronary angiography, commonly performed in elderly patients with IHD, are associated with elevated hyperthyroidism risks post-ICM exposure. A study of 810 IHD outpatients reported an increase in hyperthyroidism prevalence from 7.2 to 10% following ICM administration, and key predictors included baseline FT4 levels, thyroid nodules, and a family history of thyroid disorders [42]. The presence of comorbidities and polypharmacy further complicates thyroid management in older adults, as interactions between ICM and medications may necessitate individualized dose adjustments [84]. Pre-procedural thyroid screening and post-procedural monitoring are essential for early detection and timely intervention. Proactive strategies, including individualized hormone therapy adjustments and interdisciplinary collaboration, are critical to optimizing care and ensuring safe imaging practices in this vulnerable population [82, 85].

Pediatric populations

Children are particularly vulnerable to ICM-Induced thyroid dysfunction due to the developing nature of their endocrine systems. While the effects of ICM in adults, such as exacerbation of hyperthyroidism, are well-documented [42], the impact in infants and young children remains a crucial yet underexplored area. Infants born to mothers with thyroid disorders or iodine imbalance are especially susceptible, as maternal thyroid function directly influences fetal development and long-term neurocognitive outcomes [86]. Disruption in maternal thyroid hormone transfer during pregnancy can impair neurological development [86], emphasizing the importance of managing thyroid health in both mother and child. Maintaining appropriate iodine intake is critical for pediatric thyroid function. While iodine is essential for thyroid hormone synthesis, excessive iodine exposure, particularly in regions with routine iodine supplementation, can disrupt thyroid function, leading to conditions such as subclinical hypothyroidism [87, 88]. These disruptions highlight the delicate balance required in iodine management. Pediatric patients exposed to ICM, especially those with underlying thyroid issues or a maternal history of thyroid dysfunction, required close monitoring of thyroid hormone levels [89]. Early identification and intervention are vital to preventing adverse effects on growth, metabolism, and cognitive development. Given the variability in pediatric responses to iodine exposure, individualized follow-up protocols are essential. Further research is needed to elucidate the long-term effects of ICM exposure on pediatric thyroid function and development, and this will inform the creation of safer ICM usage guidelines, balancing the diagnostic value of imaging with the need to protect the thyroid health of children. A multidisciplinary approach, including pediatricians and endocrinologists, is also key to ensuring optimal outcomes for this population.

Future focus on ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction

While advancements have deepened our understanding of the pathophysiology and treatment of ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction, critical knowledge gaps remain. Future research should prioritize examining the long-term effects of ICM on thyroid function, especially in patients who undergo frequent imaging procedures [49]. Clarifying the dose–response relationship between ICM volume and thyroid dysfunction risk is essential, as recent studies suggest a correlation between higher doses and increased dysfunction risk [49, 66]. Additionally, as potential endocrine-disrupting chemicals, ICM raise concerns regarding environmental and public health impacts, particularly in aquatic ecosystems [90, 91]. Research on the ecological effects of ICM, including developing wastewater treatment to limit environmental contamination, is crucial. Future studies should investigate interactions between ICM and hormone receptors to understand the broader implications for human and ecological health. Moreover, the prophylactic use of agents like thiamazole or sodium perchlorate to prevent ICM-induced hyperthyroidism requires further investigation to assess their effectiveness and safety [36]. Enhancing patient education on the thyroid-related risks of ICM, exploring non-iodinated imaging alternatives, and implementing individualized monitoring protocols are also necessary. By advancing research in these areas, we can optimize clinical strategies, improve patient outcomes, and ensure that the diagnostic benefits of ICM are balanced against potential thyroid risks.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while ICM are invaluable in modern diagnostic imaging, their impact on thyroid function warrants careful consideration, particularly in at-risk populations. Further exploration of the underlying mechanisms of ICM-induced thyroid dysfunction and the development of improved management strategies will be crucial for the safe and effective use of ICM in clinical practice, and collaborative efforts between clinicians and researchers are essential to ensure that the risks of thyroid dysfunction do not overweigh the benefits of imaging.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ICM

Iodinated contrast media

- CT

Computed tomography

- CIN

Contrast-induced nephropathy

- T4

Thyroxine

- FT4

Free thyroxine

- T3

Triiodothyronine

- FT3

Free triiodothyronine

- IHD

Ischemic heart disease

Author contributions

Yaxi Hu and Lihong Zhao conceived this work; Yaxi Hu, Xia Zhong, and Dan Peng wrote the manuscript; and all the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mannemuddhu SS, Morgans HA, Warady BA. Iodine-induced hypothyroidism (IIH) in paediatric patients receiving peritoneal dialysis: is risk mitigation possible? Perit Dial Int. 2024;44(1):73–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koeppel DR, Boehm IB. Shortage of iodinated contrast media: status and possible chances - a systematic review. Eur J Radiol. 2023;164:110853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sohn SY, Inoue K, Bashir MT, et al. Thyroid dysfunction risk after iodinated contrast media administration: a prospective longitudinal cohort analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024. 10.1210/clinem/dgae304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bøhmer T, Bachtyari Z, Sommer C, Hammerstad SS. Auto regulatory capacity of the thyroid gland after numerous iodinated contrast media investigations. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2020;80(3):191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang L, Luo Y, Chen ZL, Yang ZY, Wu Y. Thyroid dysfunction associated with iodine-contrast media: a real-world pharmacovigilance study based on the FDA adverse event reporting system. Heliyon. 2023;9(11):e21694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olanrewaju OA, Asghar R, Makwana S, et al. Thyroid and its ripple effect: impact on cardiac structure, function, and outcomes. Cureus. 2024;16(1):e51574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paschou SA, Bletsa E, Stampouloglou PK, et al. Thyroid disorders and cardiovascular manifestations: an update. Endocrine. 2022;75(3):672–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bednarczuk T, Brix TH, Schima W, Zettinig G, Kahaly GJ. 2021 European thyroid association guidelines for the management of iodine-based contrast media-induced thyroid dysfunction. Eur Thyroid J. 2021;10(4):269–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Na-Nan K, Waisayanand N, Gumtorntip W, Wongthanee A, Kasitanon N, Louthrenoo W. Prevalence of thyroid dysfunctions and thyroid autoantibodies in Thai patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: an age- and sex-matched controlled study. Int J Rheum Dis. 2024;27(5):e15195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu QH, Cao X, Mao XM, Jia JY, Yan TK. Significance of thyroid dysfunction in the patients with primary membranous nephropathy. BMC Nephrol. 2022;23(1):398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medić F, Bakula M, Alfirević M, Bakula M, Mucić K, Marić N. Amiodarone and thyroid dysfunction. Acta Clin Croat. 2022;61(2):327–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu L, Xu Y, Wang X, et al. Thyroid dysfunction after immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment in a single-center Chinese cohort: a retrospective study. Endocrine. 2023;81(1):123–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee HC, Chang JG, Yen HW, Liu IH, Lai WT, Sheu SH. Ionic contrast media induced more apoptosis in diabetic kidney than nonionic contrast media. J Nephrol. 2011;24(3):376–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eng J, Wilson RF, Subramaniam RM, et al. Comparative effect of contrast media type on the incidence of contrast-induced nephropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(6):417–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jost G, McDermott M, Gutjahr R, Nowak T, Schmidt B, Pietsch H. New contrast media for K-ddge imaging with photon-counting detector CT. Invest Radiol. 2023;58(7):515–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazloumi M, Van Gompel G, Kersemans V, de Mey J, Buls N. The presence of contrast agent increases organ radiation dose in contrast-enhanced CT. Eur Radiol. 2021;31(10):7540–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Molen AJ, Dekkers IA, Geenen RWF, et al. Waiting times between examinations with intravascularly administered contrast media: a review of contrast media pharmacokinetics and updated ESUR Contrast Media Safety Committee guidelines. Eur Radiol. 2024;34(4):2512–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keyes SD, Gostling NJ, Cheung JH, Roose T, Sinclair I, Marchant A. The application of contrast media for in vivo feature enhancement in X-ray computed tomography of soil-grown plant roots. Microsc Microanal. 2017;23(3):538–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clingan MJ, Zhang Z, Caserta MP, et al. Imaging patients with kidney failure. Radiographics. 2023;43(5):e220116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Laforcade L, Bobot M, Bellin MF, et al. Kidney and contrast media: common viewpoint of the French nephrology societies (SFNDT, FIRN, CJN) and the French radiological society (SFR) following ESUR guidelines. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2021;102(3):131–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nogel SJ, Ren L, Yu L, Takahashi N, Froemming AT. Feasibility of dual-energy computed tomography imaging of gadolinium-based contrast agents and its application in computed tomography cystography: an exploratory study to assess an alternative option when iodinated contrast agents are contraindicated. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2021;45(5):691–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seeliger E, Lenhard DC, Persson PB. Contrast media viscosity versus osmolality in kidney injury: lessons from animal studies. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:358136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenhard DC, Frisk AL, Lengsfeld P, Pietsch H, Jost G. The effect of iodinated contrast agent properties on renal kinetics and oxygenation. Invest Radiol. 2013;48(4):175–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tochaikul G, Daowtak K, Pilapong C, Moonkum N. In vitro investigation the effects of iodinated contrast media on endothelial cell viability, cell cycle, and apoptosis. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2024;35(1):64–71. 10.1080/15376516.2024.2386605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Abreu JSS, Fernandes J. The contrast agent 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (TIBA) induces cell death in tumor cells through the generation of reactive oxygen species. Mol Biol Rep. 2021;48(6):5199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koca M, Sevinç Özakar R, Ozakar E, et al. Preparation and characterization of nanosuspensions of triiodoaniline derivative new contrast agent, and investigation into its cytotoxicity and contrast properties. Iran J Pharm Res. 2022;21(1):e123824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malandrino P, Russo M, Gianì F, et al. Increased thyroid cancer incidence in volcanic areas: a role of increased heavy metals in the environment? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(10):3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun Y, Teng D, Zhao L, et al. Iodine deficiency is associated with increased thyroid hormone sensitivity in individuals with elevated TSH. Eur Thyroid J. 2022;11(3):e210084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeng Z, Li K, Wang X, et al. Low urinary iodine is a protective factor of central lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid cancer: a cross-sectional study. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19(1):208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hou D, Xu H, Li P, Liu J, Qian Z. Potential role of iodine excess in papillary thyroid cancer and benign thyroid tumor: a case-control study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2020;29(3):603–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gong B, Wang X, Wang C, Yang W, Shan Z, Lai Y. Iodine-induced thyroid dysfunction: a scientometric study and visualization analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1239038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shao L, Jiang H, Liang J, Niu X, Teng L, Zhang H. Study on the relationship between TSHR gene and thyroid diseases. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2011;61(2):377–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang H, Ma Z, Cheng X, Tuo B, Liu X, Li T. Physiological and pathophysiological roles of ion transporter-mediated metabolism in the thyroid gland and in thyroid cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:12427–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amato C, Susenburger M, Lehr S, et al. Dual-contrast photon-counting micro-CT using iodine and a novel bismuth-based contrast agent. Phys Med Biol. 2023;68(13):135001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vassaux G, Zwarthoed C, Signetti L, et al. Iodinated contrast agents perturb iodide uptake by the thyroid independently of free iodide. J Nucl Med. 2018;59(1):121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pelewicz K, Wolny R, Bednarczuk T, Miśkiewicz P. Prevention of iodinated contrast media-induced hyperthyroidism in patients with euthyroid goiter. Eur Thyroid J. 2021;10(4):306–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skórkowska-Telichowska K, Kosińska J, Szymczak R, et al. Comparison and assessment of thyroid morphology and function in inhabitants of Lower Silesia before and after administration of a single dose of iodine-containing contrast agent during cardiac intervention procedure. Endokrynol Pol. 2012;63(4):294–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hai-Long S, Qin Q, Yuan-Yuan L, Bing-Rang Z. No longterm severe thyroid dysfunction seen in patients with preexisting reduced serum Tt3 concentrations after a single large dose of iodinated contrast. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(8):840–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inoue K, Guo R, Lee ML, et al. Iodinated contrast administration and risks of thyroid dysfunction: a retrospective cohort analysis of the U.S. veterans health administration system. Thyroid. 2023;33(2):230–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farebrother J, Zimmermann MB, Andersson M. Excess iodine intake: sources, assessment, and effects on thyroid function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2019;1446(1):44–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mathews DM, Peart JM, Sim RG, et al. The SELFI study: iodine excess and thyroid dysfunction in women undergoing oil-soluble contrast hysterosalpingography. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(12):3252–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonelli N, Rossetto R, Castagno D, et al. Hyperthyroidism in patients with ischaemic heart disease after iodine load induced by coronary angiography: long-term follow-up and influence of baseline thyroid functional status. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2018;88(2):272–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hwang S, Lee EY, Lee WK, Shin DY, Lee EJ. Correlation between iodine intake and thyroid function in subjects with normal thyroid function. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2011;143(3):1393–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao J, Zeng H, Guo C, Qi X, Yang Z, Wang W. Cadmium exposure induces apoptosis and necrosis of thyroid cells via the regulation of miR-494-3p/PTEN axis. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2024;202(11):5061–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klubo-Gwiezdzinska J, Jensen K, Bauer A, et al. The expression of translocator protein in human thyroid cancer and its role in the response of thyroid cancer cells to oxidative stress. J Endocrinol. 2012;214(2):207–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu Y, Li Q, Xu L, et al. Thyroid dysfunction induced by anti-PD-1 therapy is associated with a better progression-free survival in patients with advanced carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(18):16501–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kazakou P, Tzanetakos D, Vakrakou AG, et al. Thyroid autoimmunity following alemtuzumab treatment in multiple sclerosis patients: a prospective study. Clin Exp Med. 2023;23(6):2885–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y, Teng D, Ba J, et al. Efficacy and safety of long-term universal salt iodization on thyroid disorders: epidemiological evidence from 31 provinces of mainland China. Thyroid. 2020;30(4):568–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Si H, Chen K, Qin Q, Liu Y, Zhao B. Long-term effect of a large dose of iodinated contrast in patients with mild thyroid dysfunction: a prospective cohort study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2023;136(17):2044–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calvi L, Daniels GH. Acute thyrotoxicosis secondary to destructive thyroiditis associated with cardiac catheterization contrast dye. Thyroid. 2011;21(4):443–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tasker F, Fleming H, McNeill G, Creamer D, Walsh S. Contrast media and cutaneous reactions. Part 2: delayed hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44(8):5844–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cha MJ, Kang DY, Lee W, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media: a multicenter study of 196 081 patients. Radiology. 2019;293(1):117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eilsberger F, Luster M, Feldkamp J. Iodine-induced thyroid dysfunction. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2021;116(4):307–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hsieh MS, Chiu CS, Chen WC, et al. Iodinated contrast medium exposure during computed tomography increase the risk of subsequent development of thyroid disorders in patients without known thyroid disease: a nationwide population-based, propensity score-matched, longitudinal follow-up study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(50):e2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bervini S, Trelle S, Kopp P, Stettler C, Trepp R. Prevalence of iodine-induced hyperthyroidism after administration of iodinated contrast during radiographic procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Thyroid. 2021;31(7):1020–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Belloni E, Tentoni S, Puci MV, et al. Effect of iodinated contrast medium on thyroid function: a study in children undergoing cardiac computed tomography. Pediatr Radiol. 2018;48(10):1417–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bednarczuk T, Kajdaniuk D, Marek B, et al. Basics of prevention and management of iodine-based contrast media-induced thyroid dysfunction—position paper by the polish society of endocrinology. Endokrynol Pol. 2023;74(1):1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pijpers AGH, Zoetelief SE, Eeftinck Schattenkerk LD, et al. Iodinated contrast induced hypothyroidism in the infant after enteral contrast enema: a case report and systematic review. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2024. 10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2024.2023-12-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Antunez C, Barbaud A, Gomez E, et al. Recognition of iodixanol by dendritic cells increases the cellular response in delayed allergic reactions to contrast media. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41(5):657–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ahn YH, Kang DY, Park SB, et al. Allergic-like hypersensitivity reactions to gadolinium-based contrast agents: an 8-year cohort study of 154 539 patients. Radiology. 2022;303(2):329–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kornelius E, Chiou JY, Yang YS, et al. Iodinated contrast media-induced thyroid dysfunction in euthyroid nodular goiter patients. Thyroid. 2016;26(8):1030–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang Y, Xu Y, Xu M, Zhao X, Chen M. Application of oral inorganic iodine in the treatment of Graves’ disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1150036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Giovacchini G, Giovanella L, Haldemann A, Staub U, Füchsel FG, Koch P. Potentiometric measurement of urinary iodine concentration in patients with thyroid diseases with and without previous exposure to non-radioactive iodine. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2015;53(11):1753–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oszukowska L, Knapska-Kucharska M, Lewiński A. Effects of drugs on the efficacy of radioiodine (|) therapy in hyperthyroid patients. Arch Med Sci. 2010;6(1):4–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bartalena L, Bogazzi F, Chiovato L, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, Links TP, Vanderpump M. 2018 European thyroid association (ETA) guidelines for the management of amiodarone-associated thyroid dysfunction. Eur Thyroid J. 2018;7(2):55–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen Y, Zheng X, Li N, et al. Impact of iodinated contrast media in patients received percutaneous coronary intervention: focus on thyroid disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:917498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bann S, Nguyen A, Gill S, Raudzus J, Holmes DT, Wiseman SM. Lithium related thyroid and parathyroid disease: updated clinical practice guidelines are needed. J Affect Disord. 2023;339:471–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bürckenmeyer F, Schmidt A, Diamantis I, et al. Image quality and safety of automated carbon dioxide digital subtraction angiography in femoropopliteal lesions: results from a randomized single-center study. Eur J Radiol. 2021;135:109476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Owens TC, Anton N, Attia MF. CT and X-ray contrast agents: current clinical challenges and the future of contrast. Acta Biomater. 2023;171:19–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen Z, Xu C, Zhong W, et al. Iodinated contrast agents reduce the efficacy of intravenous recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator in acute ischemic stroke patients: a multicenter cohort study. Transl Stroke Res. 2021;12(4):530–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martínez-Montoro JI, Doulatram-Gamgaram VK, Olveira G, Valdés S, Fernández-García JC. Management of thyroid dysfunction and thyroid nodules in the ageing patient. Eur J Intern Med. 2023;116:16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McCullough PA, Khambatta S, Jazrawi A. Minimizing the renal toxicity of iodinated contrast. Circulation. 2011;124(11):1210–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mruk B. Renal safety of iodinated contrast media depending on their osmolarity - current outlooks. Pol J Radiol. 2016;81:157–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barrett T, Khwaja A, Carmona C, et al. Acute kidney injury: prevention, detection, and management. Summary of updated NICE guidance for adults receiving iodine-based contrast media. Clin Radiol. 2021;76(3):193–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Petranović Ovčariček P, Görges R, Giovanella L. Autoimmune thyroid diseases. Semin Nucl Med. 2024;54(2):219–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu J, Chen Z, Liu M, Jia Y, Yao Z, Wang G. Levothyroxine replacement alleviates thyroid destruction in hypothyroid patients with autoimmune thyroiditis: evidence from a thyroid MRI study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Croker EE, McGrath SA, Rowe CW. Thyroid disease: using diagnostic tools effectively. Aust J Gen Pract. 2021;50(1–2):16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miranda RA, de Moura EG, Lisboa PC. Adverse perinatal conditions and the developmental origins of thyroid dysfunction-Lessons from animal models. Endocrine. 2023;79(2):223–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rotem RS, Chodick G, Shalev V, et al. Maternal thyroid disorders and risk of autism spectrum disorder in progeny. Epidemiology. 2020;31(3):409–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liang G, Zhu Q, He X, et al. Effects of oil-soluble versus water-soluble contrast media at hysterosalpingography on pregnancy outcomes in women with a low risk of tubal disease: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e039166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Barbagallo F, Cannarella R, Condorelli RA, et al. Thyroid diseases and female sexual dysfunctions. Sex Med Rev. 2024;12(3):321–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ruggeri RM, Trimarchi F, Biondi B. Management of endocrine disease: l-thyroxine replacement therapy in the frail elderly: a challenge in clinical practice. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;177(4):R199-r217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bar-Andziak E, Milewicz A, Jędrzejuk D, Arkowska A, Mieszczanowicz U, Krzyżanowska-Świniarska B. Thyroid dysfunction and thyroid autoimmunity in a large unselected population of elderly subjects in Poland—the ‘PolSenior’ multicentre crossover study. Endokrynol Pol. 2012;63(5):346–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Grossman A, Feldhamer I, Meyerovitch J. Treatment with levothyroxin in subclinical hypothyroidism is associated with increased mortality in the elderly. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;50:65–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhai X. Effects of thyroid hormone replacement therapy on thyroid hormone levels and electrocardiogram changes in geriatric patients with hypothyroidism. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2017;30:1939–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nattero-Chávez L, Luque-Ramírez M, Escobar-Morreale HF. Systemic endocrinopathies (thyroid conditions and diabetes): impact on postnatal life of the offspring. Fertil Steril. 2019;111(6):1076–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sang Z, Wang PP, Yao Z, et al. Exploration of the safe upper level of iodine intake in euthyroid Chinese adults: a randomized double-blind trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(2):367–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhou SJ, Anderson AJ, Gibson RA, Makrides M. Effect of iodine supplementation in pregnancy on child development and other clinical outcomes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(5):1241–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nazeri P, Mirmiran P, Kabir A, Azizi F. Neonatal thyrotropin concentration and iodine nutrition status of mothers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(6):1628–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Singh RR, Rajnarayanan R, Aga DS. Binding of iodinated contrast media (ICM) and their transformation products with hormone receptors: Are ICM the new EDCs? Sci Total Environ. 2019;692:32–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yan H, Zhang T, Yang Y, et al. Occurrence of iodinated contrast media (ICM) in water environments and their control strategies with a particular focus on iodinated by-products formation: a comprehensive review. J Environ Manag. 2024;351:119931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.